1. Introduction

In today’s modern world, stress has become an omnipresent adversary, affecting individuals of all ages and backgrounds. Stress is a psychological experience and a physiological response mediated by a complex neuroendocrine, cellular, and molecular infrastructure within the nervous system [

1]. Cortisol, the stress hormone, is released during stressful situations to help the body respond [

2]. Cortisol regulates stress response, metabolism, inflammation, blood pressure, glucose availability, and plays a role in the sleep-wake cycle. Far-reaching stress effects impact both mental well-being and physical health, ultimately compromising the quality of life [

3]

. Prolonged exposure to stress can lead to significant psychological and pathological damage, particularly in the brain regions associated with cognition and emotional regulation, such as the hippocampus, hypothalamus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex [

4]. These stress-induced changes can hinder recovery, exacerbate cognitive impairments, and accelerate neurodegeneration through mechanisms such as oxidative stress, apoptosis, and neuronal imbalance [

5]. Stress has been shown to worsen various neurological conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease [

6], stroke [

7], traumatic brain injury [

8], epilepsy [

9], multiple sclerosis [

10], and Parkinson’s disease [

11], with epidemiological studies further suggesting a direct association between stress-related disorders and the risk of neurodegenerative diseases [

12]. Stress is initially a natural reaction to negative environmental factors, but it is now recognized that there are distinct types of stress: distress as a non-specific basis disease and eustress as a favorable factor affecting health and longevity [

13]. Unlike eustress, distress lasts longer, creates discomfort, overwhelms coping skills, and can cause anxiety and physical issues if unmanaged.

The importance of managing stress has never been more apparent, and stress management techniques, which encompass physical, emotional, and lifestyle control, have become essential in promoting overall well-being. Numerous relaxation methods, such as behavioral therapy, meditation, yoga, deep breathing, and massage, have proven effective in reducing stress [

14,

15]. Among these, balneotherapy (BT) has gained increasing recognition for its therapeutic potential [

16]. BT, which includes a variety of treatment modalities such as hydrotherapy, mineral baths, mud therapy, and the use of natural earth remedies, has been practiced for centuries, dating back to ancient civilizations that valued the healing properties of natural springs and mineral-rich waters [

17]. Over time, BT has evolved into a structured treatment approach used in health resorts to promote physical and mental health. Research has demonstrated that balneotherapy is beneficial in improving overall health, reducing fatigue, and stress, alleviating pain, and enhancing quality of life [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Furthermore, various types of water therapies have been linked to improved sleep, decreased anxiety and depression, and enhanced health-related quality of life, especially in older patients [

22]. A systematic review has suggested that BT may influence cortisol levels in both healthy and ill subjects, thereby improving stress resilience and offering valuable benefits for managing stress conditions [

23].

Despite historical and scientific evidence supporting the efficacy of mineral water and peloid treatments in stress reduction, comprehensive scientific investigations into their mechanisms and broader therapeutic impacts are still limited. Understanding the connections between mineral water, peloid treatments, and stress reduction is crucial for advancing holistic health strategies. By elucidating the scientific basis and clinical relevance of these natural therapies, healthcare providers can integrate them into comprehensive stress management protocols, offering patients alternative, non-invasive pathways to optimal health

BT relevance to neurological rehabilitation is particularly significant due to its potential to improve autonomic nervous system regulation, reduce psychological stress, and induce physiological relaxation. These outcomes can positively influence neuroplasticity, support recovery processes, and enhance patients’ overall quality of life. For individuals suffering from conditions such as post-stroke fatigue, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and neuropathic pain—where stress and cortisol dysregulation play detrimental roles—BT could serve as a complementary intervention to optimize rehabilitation outcomes, but the more research in this field is needed.

This study aimed to evaluate the seasonal effects of BT on distress, salivary cortisol, and integrative outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

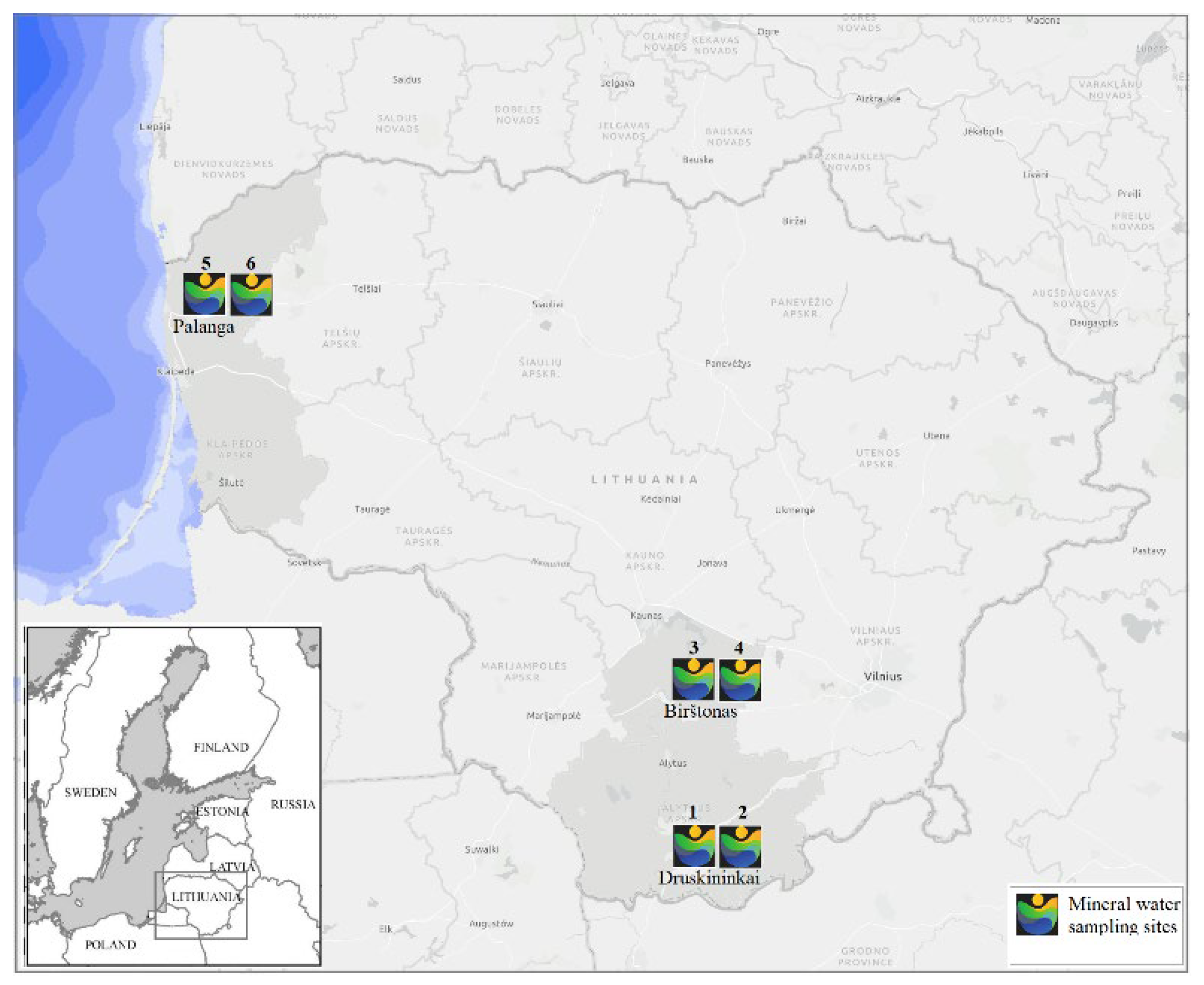

This study was designed as a multicenter randomized controlled single-blinded (for researchers) parallel groups interventional study with 2 intervention periods during winter (January- February) and summer (August-September), 2023 in 6 medical spa centers in Lithuania: Gradiali (Palanga), Atostogų parkas (Kretingos reg), Egle (Druskininkai), Draugystė (Druskininkai), Tulpė (Birštonas), Versmė (Birštonas) in Lithuania. The location of medical spas that participated in the study is shown in SA1. This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Kaunas Regional Research Ethics Committee (permission code BE-2-87, date 28/11/2022), and registered in ClinicalTrial.gov (Identifier: NCT06018649, date 30/08/2023). Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Study Participants and Sample Size

The study inclusion criteria were an age of 18–65 years, moderate stress intensity > 3 points (10, VAS), and residency in the area near the selected medical spa or the possibility to travel to service centers. The exclusion criteria were uncontrolled/decompensated systemic diseases, active infection, malignant tumors, surgery, or major trauma in the past year, applied balneotherapy treatment during a 3-month period, pregnancy or lactation, bleeding, severe mental and physical health problems, and difficulties with reach study area. All the participants signed the informed consent with the information about the study’s aim, terms, and description of this study before it started.

Sampling was a probabilistic nest (cluster), in which each research participant’s entry into the sample was multi-stage, criterion-based. The sample size required for statistically significant comparisons of the rehabilitation effect of the means of quantitative variables before and after the procedures was calculated by the G*Power program according to data of the authors’ previous published studies [

16]. Effect 0.32 – the smallest effect size in the article that was statistically significant when assessing stress management in the control group. For a calculated sample size of 0.32, 0.4, and 0.5, the group size would be 79, 52, and 34 subjects, respectively. A rehabilitation effect size of 0.4 and a small “loss” of data were chosen, so it was planned to have 55 subjects in each group.

Persons who met eligibility criteria were allocated by trained administrative personnel to Klaipeda and Druskininkai clusters, coded, and randomly assigned to the respective group (1-6) by a statistician using a computer program after the initial screening (T0) at the study centers. All selected participants were randomized into groups using a predetermined SPSS method, ensuring unbiased allocation to different experimental conditions or treatment arms. The parameters of age, sex, and baseline stress level analyzed by a Pearson chi-square test or ANOVA, Tukey’s honestly test, had no significant difference between the six groups.

The study groups were named by acronyms of treatment mode: 11ABT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment, 11ABTNT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex plus nature therapy treatment, 11BTS- 2 weeks of inpatient BT treatment in resort, 11C - 2 weeks control group without treatment. The groups of delayed procedures were named 6ABTS- 1 week of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer, 11ABTS- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer. All group participants except 11BTS continue their daily work activity. The periods of examination were: T0- baseline/before treatment, T1- after treatment.

A total of 1137 individuals were assessed for eligibility. Following the initial evaluation and re-assessment of inclusion and exclusion criteria, final Excel files containing the allocation lists of eligible participants in clusters (N=194 in Klaipeda and N=179 in Druskininkai) were provided to the allocation manager responsible for randomization and allocation. Randomization was conducted using the SPSS function “Random Sample of Cases,” which allows for the selection of a subset of cases based on an approximate percentage or an exact number.

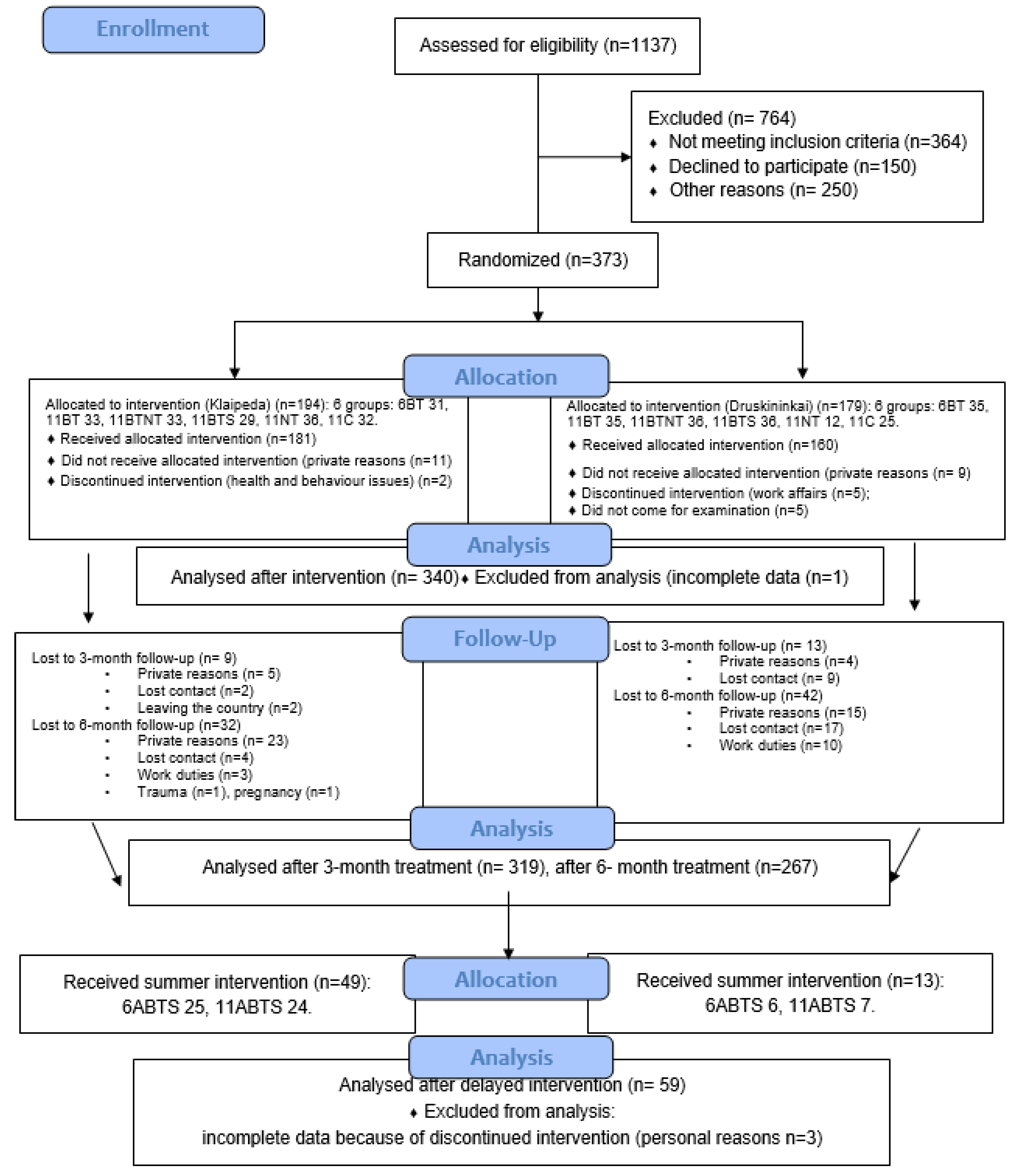

This article analyzes the short-term effects of BT across two intervention periods: winter and summer. The study flow diagram is presented in

Figure A2. Six groups of participants (N=340) received winter interventions, with assessments conducted after the treatment course, while two (nature therapy and control) groups (N=59) received summer interventions (delayed), also with post-treatment assessments.

The assessment periods were as follows: winter-time groups (6ABT, 11ABT, 11ABTNT, 11SBT, 11NT, and 11C): T0: Baseline/before treatment (27–29 January 2022), and T1: After treatment (6ABT group: 5 January 2023; remaining groups: 11–12 February 2023); Summer-time groups (6ABTS, 11ABTS): T0: Baseline/before treatment (11–13 August 2023), and T1: After treatment (6ABTS group: 21 August 2023; 11ABTS group: 28 August 2023). The researchers and physicians conducting participant screenings were blinded to group allocations. Data from 399 participants were included in the analysis.

Study Outcomes and Instruments

The primary study outcomes were the treatment effect on distress symptoms intensity, management, and changes in saliva cortisol. Secondary outcome- effect on integrative outcomes. Distress was measured using GSDS scale (General Symptoms Distress Scale, T. Badger), where participants were asked to provide a global rating of how distressing 14 numbered stress symptoms are on a 10-point scale, with higher scores indicating more distress. For stress management, participants were asked to provide a global rating of how well they can manage their symptoms on a 10-point scale with higher scores indicating a better ability to manage symptoms [

24]. The Cronbach alfa for the GSDS used was 0.771. For the effect on integrative outcomes research, we have used AIOS scale (Arizona Integrative Outcomes Scale, Iris R Bell [

25]. This is a visual analog scale of one element, where the participant self-assesses their overall feelings of spiritual, social, psychological, emotional, and physical well-being over the past 24 hours or the past month. The AIOS can separate relatively ill individuals from relatively healthy ones. It also correlates with measures of distress, positive and negative affect, and indicators of positive mental states. Permissions to use scales were obtained from the authors.

Laboratory outcomes- effect on salivatory cortisol level. The stress hormone cortisol was measured in saliva. Measurement of cortisol in saliva is a non-invasive and ecologically valid tool for detecting early changes in brain health, as well as evaluating the effectiveness of strategies in relieving stress and improving brain health as well as monitoring stress-related brain changes [

26]. A specified amount of saliva was taken into the dispenser and the amount of cortisol in it was tested in a certified laboratory (Germany). Higher cortisol numbers indicate higher stress levels. The parameters of the method used for measurement of cortisol: enzyme Immunoassay (ELISA), device: Tecan Evolyzer; the name of the kit: Cortisol Saliva Elisa Tecan; REF: RE52611. Quantitation as functional sensitivity: 0,005 µg/dl (with a precision of 20 %); inter-assay: range between 10,1 % and 19,5 % (CV: 13,2 %); intra-assay: range between 3,2 % and 6,1 % (CV: 4,3%).

Treatments

The all-BT treatment groups (6ABT, 11ABT, 11ABTNT, 11SBT, 6ABTS, 11ABTS) received same BT complex consisting of 20 min of tap water pool with light exercises, mineral/geothermal water bath- 34-36° 20 min, sapropel wrapping- 20 min, salt therapy- 25 min.

Nature therapy procedure was as follows: a 45-minute walk in nature (forest or seaside), a complex of simple strength and breathing low-intensity exercises, sensory impulses (landscape, forest smells- aromatherapy, natural sounds of nature, collecting nature’s goodies, mindfulness therapy, heliotherapy. The first procedure was provided by physiotherapist, the rest of them had to be performed by the participant independently with accurate instructions given, and with each day SMS received.

The mineral water used in research centers was highly mineralized sodium chloride (salt) with significant calcium, magnesium, and sulphate (pH 5.71-7.54, TDS 16.750-82.445 g/l). The bath prescribed were of moderate mineralization- brine. Peloids used for wrapping or bath were pH 6.6-7.0, humidity 70.5- 96, total mineralization 38.5- 20000 mg/l.

The peloids used in the study varied in pH 6,6-7,0, humidity 70,51-96.00%, TDS 50-20007 mg/l, organic material 14,32-91,96%, humic acid 1.22-28.25, fulvic acid 0.98- 17.9 %, with Ca, Fe, Mg, Cl, S, Si.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data were presented as means and SD (standard deviations) graphically by means and 95% CI. Independent 2-tailed t-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square test, chi-square statistic to compare variables frequencies in each rehabilitation group, z-test for categorical variables was used to examine between categories. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey HSD post-hoc multiple comparison tests were used to assess the differences between mean values of variables across the study groups. Comparison of variable means at the treatment beginning (T0), and end (T1) was performed using Paired-Samples t-test. When the conditions of normality of the variables were not met, the differences between the values of the variables in the rehabilitation groups were evaluated by applying the Friedman non-parametric test. Sample size-adjusted effect sizes (Cohen’s d statistic) were calculated A p value <0.05 denoted statistical significance. Analyses were performed with the SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows). Version 28.0 SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL.

3. Results

3.1. The Characteristics of Study Participants

The characteristics of study participants is shown in

Table 1.

The groups did not differ in sociodemographic and post-Covid parameters. The groups differ in baseline stress intensity and management. Stress intensity was higher in winter 6ATB group than in 11NT (MD 1.8, p<0.001), and in summer groups- 6ATBS (MD 1.9, p=0.002) and 11ABTS (MD 1.8, p=0.009); in 11ABT and 11NT (MD 1.6, p=0.009) and 6ABTS (MD 1.7, p=0.011); in 11ABTNT than in 11NT (MD 1.8, p=0.001) and summer groups- 6ABTS (MD 1.9, p=0.002) and 11ABTS (MD 1.6, p=0.029). Stress management was better in 11NT (MD -1.4, p=0.027) and 6ABTS (MD -1.6, p=0.031) than in 11SBT.

The correlations between stress and age (-0.103, p=0.043), working time (0.223, p<0.001), physical activity (0.107, p=0.036), covid-19 infection (-0.108, p=0.036), and stress management (-0.298, p<0.001) were found.

3.2. The Treatment Effect on Distress

3.2.1. The Effect on Distress Symptoms

The study results on changes in distress symptoms during winter and summer interventions are summarized in

Table 2 and

Table 3. Statistically significant improvements were observed in 11–13 out of 14 distress symptoms following winter interventions and in 3–6 symptoms after summer interventions, with better outcomes noted after two-week intervention.

Effect size: Calculated as Cohen’s d, with thresholds defined as 0.2 (small), 0.5 (medium), 0.8 (large), and 1.3 (very large).

Winter time interventions

1-week BT interventions showed large effect sizes for fatigue, headache, anxiety, memory, and concentration; moderate effects for sleep, pain, depression, appetite, obstipation, and rash; and small effects for diarrhea. No significant effects were observed for nausea, vomiting, and tingling.

2-week outpatient BT interventions produced large effects for fatigue and anxiety, moderate effects for sleep, pain, headache, depression, memory, concentration, and tingling, and small effects for appetite, nausea, obstipation, and rash.

BT combined with nature therapy demonstrated large effects on fatigue, anxiety, and memory/concentration; moderate effects for sleep, appetite, and nausea; and small effects for pain, depression, vomiting, obstipation, diarrhea, tingling, and rash.

Inpatient BT interventions had very large effects on fatigue, large effects for pain, anxiety, and tingling, moderate effects for sleep, memory/concentration, appetite, and nausea, and small effects for headache, depression, obstipation, and diarrhea.

Nature therapy alone significantly reduced pain and headache with moderate and small effects, respectively, but slightly worsened diarrhea.

Minimal effects were observed in the control group, including small reductions in fatigue and tingling, alongside a slight worsening of obstipation.

Summer time interventions

After conducting post hoc tests for multiple comparisons, significant differences were identified between groups before and after treatment (

Table 3). At baseline, all distress symptoms, except for diarrhea, were more pronounced during the winter season, making it challenging to accurately assess differences following the treatment course.

No significant differences were observed between summer groups before and after treatment. However, in the winter season groups, the effect on fatigue significantly differed between treatment modalities post-treatment. The inpatient group showed superior outcomes compared to the outpatient group (MD -1.36, p=0.02), BT with nature therapy (MD -1.25, p=0.046), as well as the nature-only (MD -2.21, p<0.001) and control groups (MD -2.30, p<0.001). Memory and concentration showed greater improvement in the 1-week BT group compared to the inpatient group (MD -1.26, p=0.008).

In reducing diarrhea, BT combined with nature therapy was more effective than the 2-week BT group (MD -0.57,

p=0.016). Tingling and numbness were significantly reduced by inpatient BT procedures compared to outpatient treatments (MD 0.83,

p=0.036). Additional significant differences were identified between treatment groups when compared to nature-only and control groups (

Table 3).

3.2.2. The Effect on Distress Symptoms Intensity

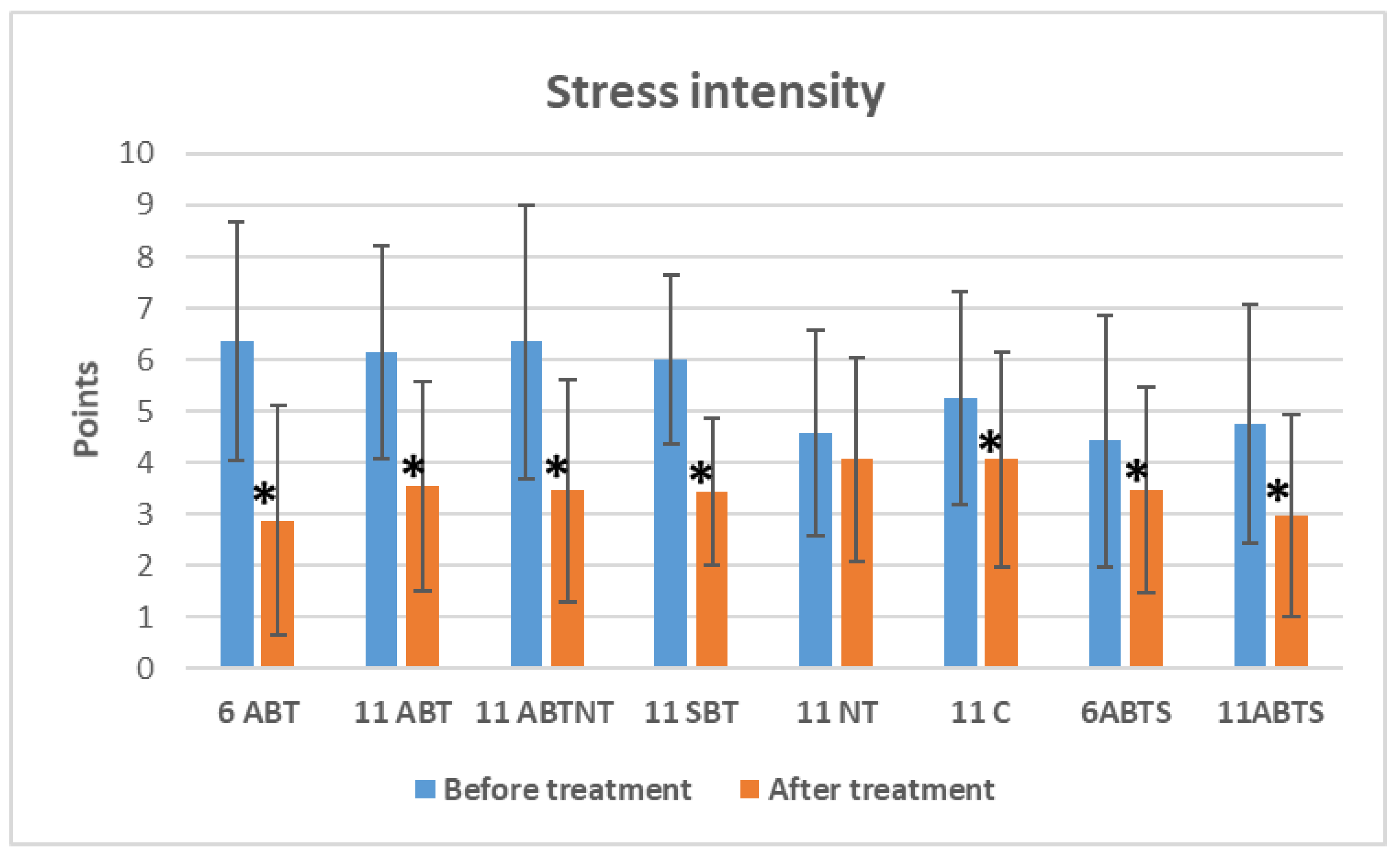

Figure 3 presents the data on overall distress symptom intensity changes across treatment groups. Statistically significant reductions in distress intensity were observed in both winter and summer BT groups between baseline and post-treatment periods.

Figure 1.

The change of distress intensity in study groups after interventions. Abbreviations: 11ABT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment, 11ABTNT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex plus nature therapy treatment, 11BTS- 2 weeks of inpatient BT treatment in resort, 11C - 2 weeks control group without treatment. The groups of delayed procedures were named 6ABTS- 1 week of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer, and 11ABTS- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer.

Figure 1.

The change of distress intensity in study groups after interventions. Abbreviations: 11ABT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment, 11ABTNT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex plus nature therapy treatment, 11BTS- 2 weeks of inpatient BT treatment in resort, 11C - 2 weeks control group without treatment. The groups of delayed procedures were named 6ABTS- 1 week of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer, and 11ABTS- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer.

In the 1-week winter ambulatory BT group, stress intensity decreased by 3.5 points (VAS) (p<0.001, Cohen’s d=1.1, large effect).

Similarly, reductions of 2.6 points (VAS) (p<0.001, Cohen’s d=1.0, large effect) and 2.9 points (VAS) (p<0.001, Cohen’s d=0.8, large effect) were observed in the 2-week winter ambulatory BT group and the 2-week BT with nature therapy group, respectively.

In the 2-week inpatient BT group, distress intensity was reduced by 2.6 points (VAS) (p<0.001, Cohen’s d=1.3, very large effect).

During the summer, stress intensity decreased by 1.0 point (VAS) (p=0.032, Cohen’s d=0.4, small effect) in the 1-week ambulatory BT group and by 1.8 points (VAS) (p<0.001, Cohen’s d=0.8, large effect) in the 2-week ambulatory BT group.

Notably, a reduction was also observed in the control group, with stress intensity decreasing by 1.2 points (VAS) (p<0.001, Cohen’s d=0.6, moderate effect).

No significant changes in distress intensity were found in the nature therapy group.

The between-group comparison revealed significant differences in baseline distress intensity (

p<0.001, ANOVA effect size=0.1) and post-treatment distress intensity (

p=0.031, ANOVA effect size=0.04) (

Table 1). Following treatment, a significant difference was observed between the 1-week BT group and the control group, with a mean difference (MD) of -1.2 (

p=0.045).

3.2.3. The Effect on Distress Symptoms Management

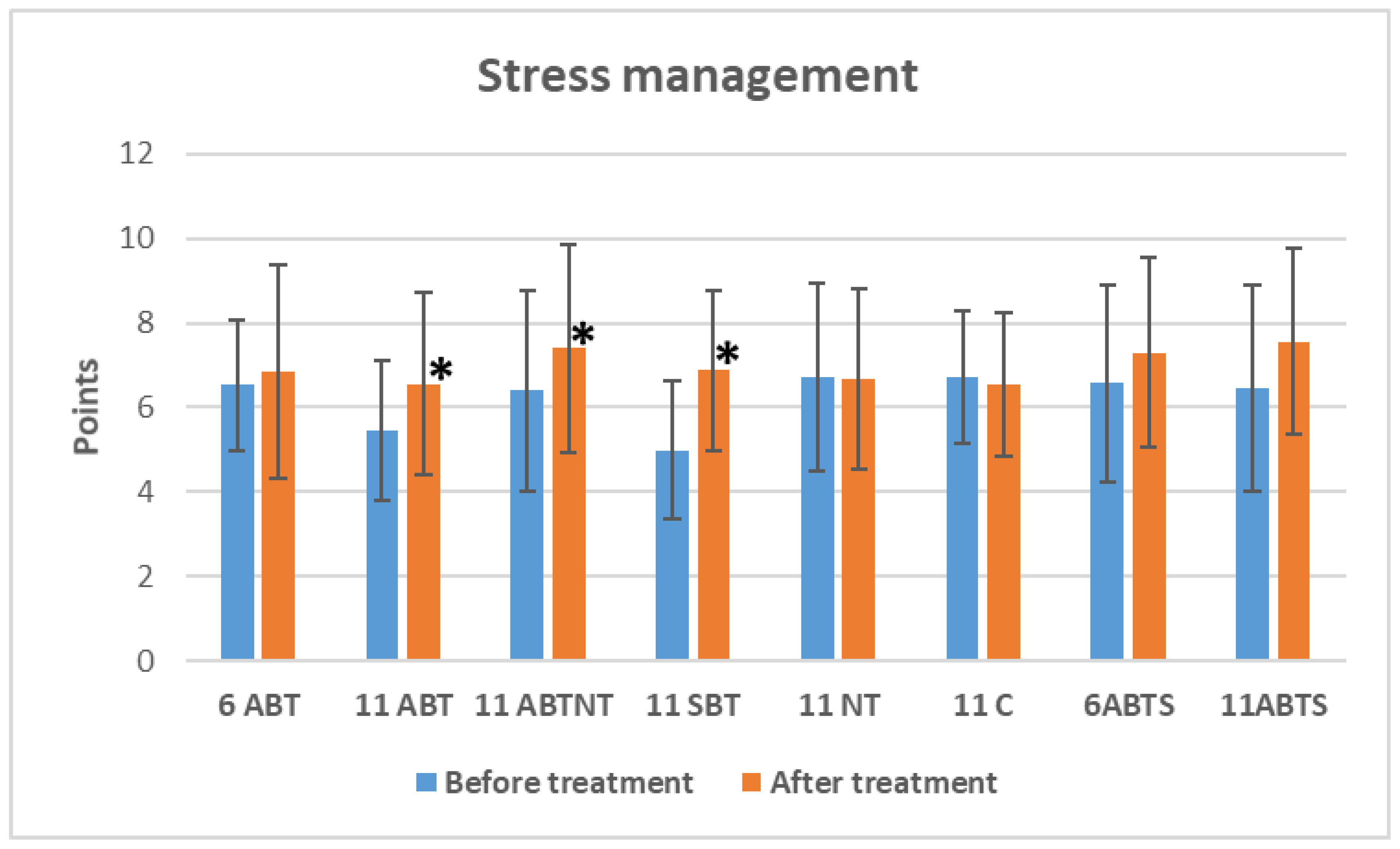

Significant improvements in distress management were observed in three winter intervention groups following treatment (

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The change of distress symptoms management in study groups after interventions. Abbreviations: 11ABT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment, 11ABTNT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex plus nature therapy treatment, 11BTS- 2 weeks of inpatient BT treatment in resort, 11C - 2 weeks control group without treatment. The groups of delayed procedures were named 6ABTS- 1 week of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer, and 11ABTS- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer.

Figure 2.

The change of distress symptoms management in study groups after interventions. Abbreviations: 11ABT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment, 11ABTNT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex plus nature therapy treatment, 11BTS- 2 weeks of inpatient BT treatment in resort, 11C - 2 weeks control group without treatment. The groups of delayed procedures were named 6ABTS- 1 week of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer, and 11ABTS- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer.

The 2-week ambulatory BT group demonstrated an improvement of 1.1 points (p=0.002, Cohen’s d=0.4, small effect), the 2-week BT plus NT group showed an improvement of 1.0 points (p=0.012, Cohen’s d=0.3, small effect), and the 2-week inpatient BT group exhibited the largest improvement, with a 1.9-point increase (p<0.001, Cohen’s d=0.9, large effect). Non-significant reductions in stress management were observed in the control group, while non-significant positive changes were noted in the short-term winter and summer intervention groups.

Between-group comparisons revealed significant differences in baseline stress intensity (p<0.001, ANOVA effect size 0.1) (

Table 1). However, no significant differences were observed between groups after treatment (p=0.181).

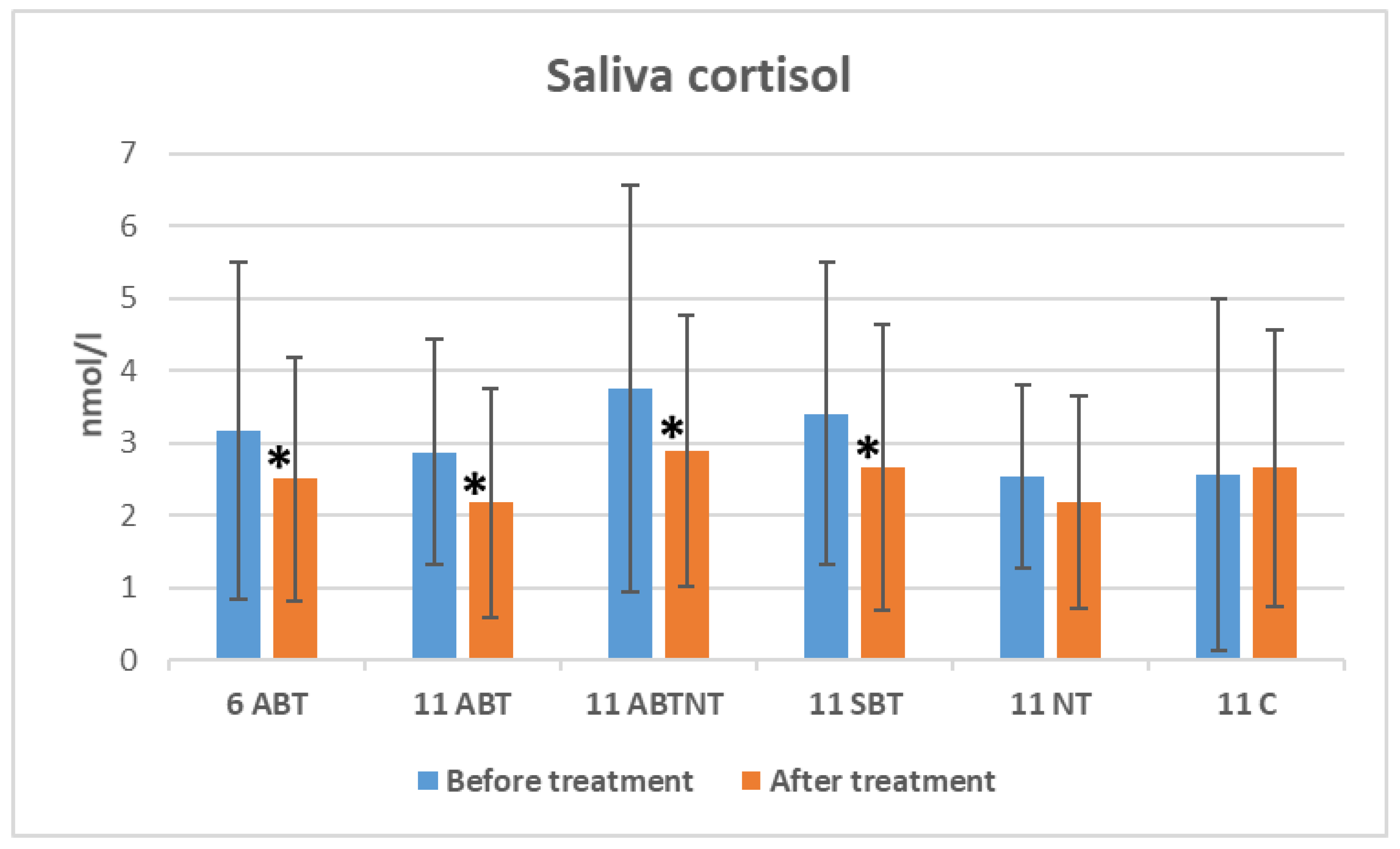

3.3. The Treatment Effect on Salivary Cortisol

The changes in salivary cortisol levels following winter interventions are illustrated in

Figure 3. Salivary cortisol levels significantly decreased after BT treatments: a reduction of 0.67 nmol/L was observed in the 1-week BT group (p=0.013, Cohen’s d=0.3, small effect); 0.69 nmol/L in the 2-week ambulatory BT group (p=0.014, Cohen’s d=0.4, small effect); 0.87 nmol/L in the BT plus nature therapy (NT) group (p=0.006, Cohen’s d=0.4, small effect); and 0.74 nmol/L in the inpatient group (p=0.034, Cohen’s d=0.2, small effect).

Figure 3.

The change of saliva cortisol in study groups after winter interventions. Abbreviations: 11ABT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment, 11ABTNT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex plus nature therapy treatment, 11BTS- 2 weeks of inpatient BT treatment in resort, 11C - 2 weeks control group without treatment. The groups of delayed procedures were named 6ABTS- 1 week of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer, and 11ABTS- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer.

Figure 3.

The change of saliva cortisol in study groups after winter interventions. Abbreviations: 11ABT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment, 11ABTNT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex plus nature therapy treatment, 11BTS- 2 weeks of inpatient BT treatment in resort, 11C - 2 weeks control group without treatment. The groups of delayed procedures were named 6ABTS- 1 week of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer, and 11ABTS- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer.

Between-group comparisons indicated significant differences in baseline cortisol levels (p=0.040, ANOVA effect size=0.04). However, no significant differences in cortisol levels were found between groups after treatment (p=0.283).

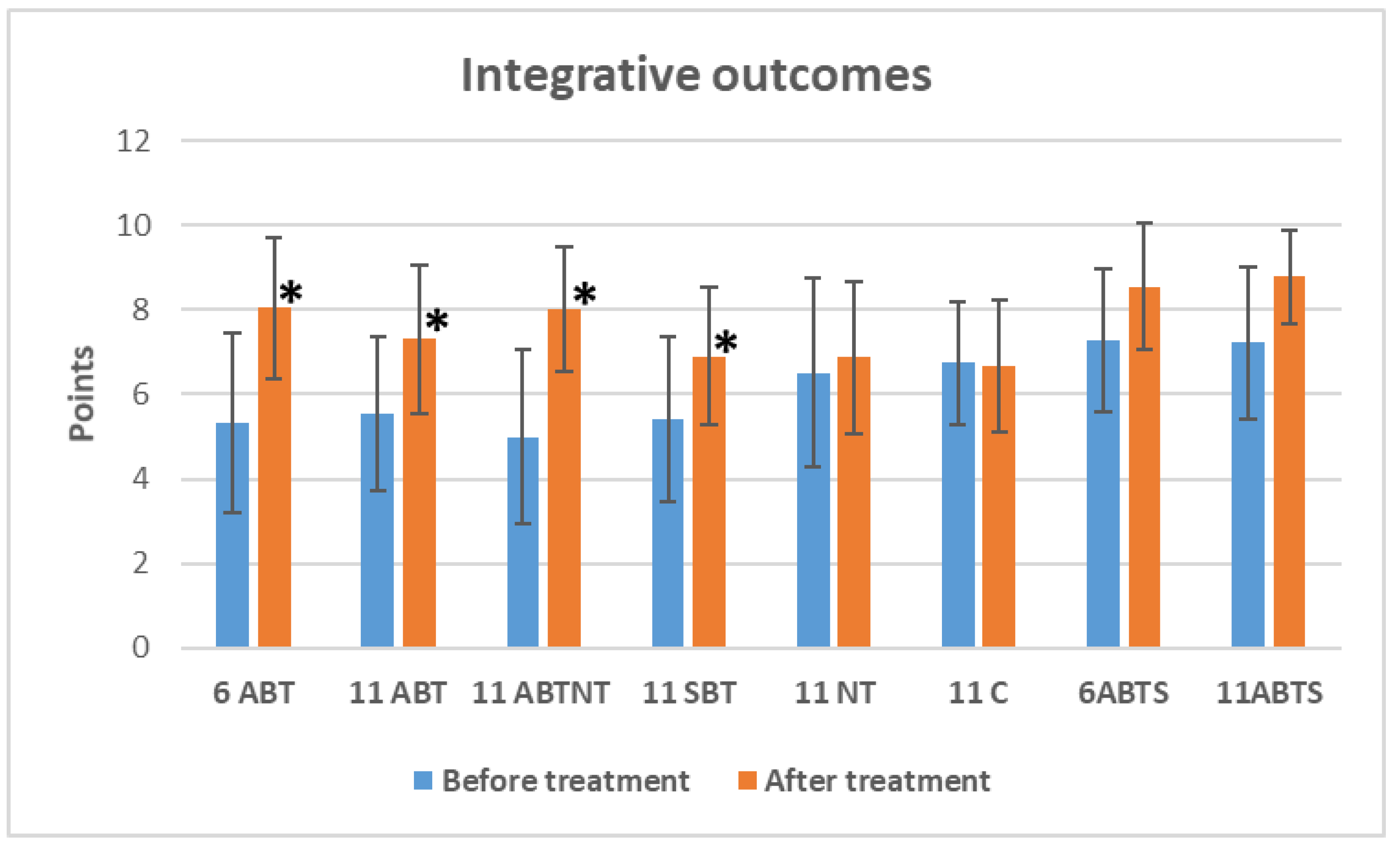

3.4. The Treatment Effect on Integrative Outcomes

The changes in integrative outcomes, as measured by the sense of overall well-being, are depicted in

Figure 4. Winter interventions significantly improved the sense of well-being. Specifically, the 1-week ambulatory BT increased well-being by 2.7 points (

p<0.001, Cohen’s

d=-1.1, large effect); the 2-week ambulatory BT by 1.9 points (

p<0.001, Cohen’s

d=-0.8, large effect); the BT plus NT group by 3.0 points (

p<0.001, Cohen’s

d=-1.4, very large effect); and the inpatient BT group by 1.4 points (

p<0.001, Cohen’s

d=-0.8, large effect).

Figure 4.

The change of integrative outcomes in study groups after interventions. Abbreviations: 11ABT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment, 11ABTNT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex plus nature therapy treatment, 11BTS- 2 weeks of inpatient BT treatment in resort, 11C - 2 weeks control group without treatment. The groups of delayed procedures were named 6ABTS- 1 week of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer, and 11ABTS- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer.

Figure 4.

The change of integrative outcomes in study groups after interventions. Abbreviations: 11ABT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment, 11ABTNT- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex plus nature therapy treatment, 11BTS- 2 weeks of inpatient BT treatment in resort, 11C - 2 weeks control group without treatment. The groups of delayed procedures were named 6ABTS- 1 week of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer, and 11ABTS- 2 weeks of ambulatory BT complex treatment in summer.

Between-Group Comparisons

Significant differences in baseline well-being were observed (p<0.001, ANOVA effect size=0.15). At baseline, nature therapy, control, and summer intervention groups showed higher well-being scores compared to winter interventions. After treatment, significant differences emerged between groups (p<0.001, ANOVA effect size=-0.16).

The 1-week BT group showed a greater improvement compared to the inpatient group (MD=1.2, p=0.003), nature therapy group (MD=1.2, p=0.008), and the control group (MD=1.4, p<0.001).

The 2-week ambulatory BT group had a greater effect compared to the summer 1-week group (MD=-1.2, p=0.026) and the summer 2-week group (MD=-1.5, p=0.003).

The BT plus NT group showed a greater improvement compared to the inpatient group (MD=1.1, p=0.003), the nature therapy group (MD=1.2, p=0.008), and the control group (MD=1.4, p<0.001).

The inpatient BT group demonstrated greater improvement compared to the summer groups: 1-week (MD=-1.7, p<0.001) and 2-week (MD=-1.9, p<0.001).

3.5. Regression Analysis for Distress Intensity Outcome

We conducted a regression analysis with the dependent variable GSDS_1 (distress symptom intensity after treatment) to identify potential prognostic parameters (

Table 4).

The model demonstrated a coefficient of determination (R²) of 0.362, with a statistically significant regression model (p<0.001, ANOVA). The analysis revealed significant beta coefficients for the following predictors: Work and social adaptation (β=0.32), State anxiety (β=0.33), Trait anxiety (β=-0.39), and Integrative outcomes (β=-0.26). Notably, saliva cortisol and other variables did not exhibit significant predictive value.

An increase in the predictor variables “work and social adaptation” and “state anxiety” was associated with an increase in the dependent variable—distress symptom intensity, while the “sense of well-being/integrative outcomes” and “trait anxiety” were associated with a decrease in distress intensity. These results are summarized in

Table 4.

4. Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the effectiveness of balneotherapy and its variants, including combinations with nature therapy, in managing distress symptoms and promoting overall well-being. We found that the intensity of distress was reduced using different modes of procedures which include different natural resources, regardless of treatment duration, composition and season (MD 1- 3.5 points, VAS). The 2-week interventions, both ambulatory and inpatient, consistently produced superior results compared to shorter, 1-week treatments.

The findings demonstrate that winter interventions were more effective than summer interventions in reducing distress symptoms, improving stress management, and enhancing overall well-being. Winter interventions were effective on twice as many distress symptoms as 2-week summer intervention. Winter BT interventions, particularly the 2-week inpatient program, demonstrated the largest improvements in distress symptoms, with large to very large effect sizes for fatigue, pain, anxiety, and tingling. The addition of nature therapy to BT further enhanced outcomes, particularly for fatigue, anxiety, and memory/concentration problems. The positive outcomes of combined BT and green exercises, when compared to green exercises alone and the control group, demonstrated significant improvements in health-related quality of life and mental well-being among patients with lower back pain. This suggests that the integrative approach of BT and green exercises enhances the therapeutic effects, providing a more effective intervention for managing both physical and psychological aspects of lower back pain [

27].

In contrast, summer BT interventions showed modest improvements, with significant results primarily observed in fatigue, rash, and anxiety reduction. This seasonal variation suggests that winter interventions might provide a more controlled and intensive therapeutic environment conducive to managing distress symptoms. Between- group analysis revealed that inpatient treatment was superior in reducing fatigue and tingling/numbness, while short-term winter treatment was superior in reducing memory and concentration problems. There was no between-group difference in summer interventions.

Saliva cortisol levels, an objective marker of stress, were significantly reduced following winter BT interventions. However, no significant differences were observed between groups post-treatment, indicating that while BT is effective in lowering cortisol, the effects may not vary drastically across different modalities. This finding supports BT as a viable intervention for stress reduction and highlights its potential integration into broader stress management and neurological rehabilitation strategies.

The sense of overall well-being improved significantly across all winter BT interventions, with very large effects observed in the BT plus NT group. Improvements in well-being were less pronounced in summer interventions and the control group, emphasizing the enhanced efficacy of winter interventions. Notably, the regression analysis indicated that a higher sense of well-being was associated with a decrease in distress intensity, underscoring the importance of integrative outcomes in evaluating treatment success.

By comparing our results with existing trials and literature, we can elucidate the unique contributions and implications of mineral water and peloid treatments in stress reduction. Firstly, our study corroborates previous research demonstrating the stress-alleviating effects of balneotherapy. It was proved that BT has diverse benefits, with particular emphasis on quality of life, well-being, and physical conditioning [

28]. It has been found that even short- term BT reduces subjective stress [

20] and cortisol amount in saliva [

21,

30]

. Balneotherapy including spa therapy or aquatic exercise relieves mental stress and sleep disorders, and improves general health in sub-healthy people [

31]

. The study that compares the physical and mental effects of 2 weeks of bathing or showering intervention, showed that bathing intervention was more beneficial than showering intervention: VAS scores were significantly better for fatigue, stress (−15.3 vs −10.2), pain, self-reported health (9.9 vs 5.5) after bathing than after showering [

21]. From a physiological perspective, BT treatment can increase serum β-endorphin levels and may modify cortisol levels to improve individual resilience to stress without disrupting the circadian rhythm of this hormone [

32,

33]. A significant effect has been observed on neurotransmitter serotonin, which mediates various biological and behavioral processes such as circadian rhythms, food intake, sleep, reproductive activity, pain perception, cognition, mood, and anxiety or stress [

34]. Research revealed positive effects of BT in reducing stress, fatigue, mood disturbances, feelings of depression and burnout, waist circumference [

31] as well as improving quality of life, sleep, psychomotor performance, and mental activity [

16,

23,

35]. Compared to progressive muscle relaxation, BT provides greater relaxation and similarly reduces cortisol levels in saliva [

36]. In the study conducted by Toda et al., saliva samples were collected immediately before and after spa bathing from 12 healthy males, and it was shown that salivary cortisol levels decreased after spa bathing [

37]. A new study shows that daily bathing in a neutral bicarbonate ionized bath can reduce psychological tension, improve sleep quality, enhance immune system function, and have a positive impact on health for those experiencing daily life stressors [

38]. The systematic review concluded that s

pa therapy with or without included mud/peloid therapy demonstrated the same potential to influence cortisol levels also in sub-healthy and ill subjects; levels of cortisol decreased in response to a single session and improved after an entire cycle of spa therapy [

23]

. 2017 study surveying 4,265 hot springs users found that bathing in hot springs provided significant relief for depression, anxiety, and insomnia [

20]. Various scientific evidence confirms that BT is an effective and valuable supplementary method for reducing stress and enhancing mental health [

39]. Our findings align with these studies, providing further evidence of the efficacy of balneotherapy as a non-pharmacological approach to stress management in a broader context

The results highlight significant seasonal and treatment-related differences, emphasizing the potential of BT in the context of brain health and neurological rehabilitation. Stress negatively impacts brain injuries and diseases, affecting brain regions through various pathways. It can lead to mental disorders in children and adults impairing neural plasticity, increasing the risk of emotional issues [

4]. Chronic stress and associated distress symptoms are known to negatively affect cognitive function, emotional regulation, and overall neurological health. The observed improvements in memory, concentration, and anxiety suggest that BT can support cognitive rehabilitation and mental well-being in patients with neurological impairments. The large effect sizes for fatigue and pain also indicate its utility in managing common neurological symptoms, such as chronic fatigue syndrome and neuropathic pain. The demonstrated efficacy of BT, particularly in winter, highlights its potential as a non-invasive, holistic intervention for stress-related neurological conditions. The findings support the integration of BT into multidisciplinary treatment frameworks for neurological rehabilitation. Its stress-reducing effects, evidenced by cortisol reductions and improvements in stress management, align well with therapeutic goals in managing neurodegenerative diseases, stroke recovery, and traumatic brain injury. Furthermore, the inclusion of nature therapy as an adjunctive therapy offers a promising avenue for enhancing the therapeutic impact of BT, particularly for cognitive and emotional outcomes.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its strengths, the study has limitations, including the relatively small sample size in groups especially in summer season, the complex spa effect, and potential confounding variables. Lack of standardization for the content of natural resources, application mode used, and longer or shorter rest periods during work activities. These factors make it challenging to compare results across groups and draw definitive conclusions. Standardized protocols would enhance the comparability of studies. The seasonal differences in baseline distress symptoms, particularly the higher levels observed during winter, may have influenced treatment outcomes. The lack of significant changes in some variables, such as saliva cortisol and distress symptoms in summer interventions, warrants further investigation. Future studies should explore the long-term effects of BT and its applicability to diverse populations, including those with specific neurological disorders. The potential role of NT as a standalone or complementary therapy also merits further exploration to optimize treatment protocols for brain health and neurological rehabilitation. Further research on stress mechanisms and therapeutic approaches is needed.

5. Conclusions

Our study highlights the significant stress-reducing benefits of combining natural resources, particularly balneotherapy and nature therapy, with enhanced efficacy observed during winter and inpatient treatment modes.

This study underscores the efficacy of BT, particularly during winter, in reducing distress symptoms, improving stress management, and enhancing overall well-being. The findings highlight the potential of BT as an integrative approach in brain health and neurological rehabilitation. By addressing both psychological and physiological dimensions of stress, BT offers a holistic, innovative, and evidence-based intervention for improving quality of life and supporting neurological recovery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.R. and A.B.; methodology, L.R and A.F.; software, A. M.; validation, L.R., A.B. and A.M.; formal analysis, A.M..; investigation, L.R, A.B., G.T., and D.R.; resources, L.R and A.B.; data curation, L.R, A.B. and A.M..; writing—original draft preparation, L.R.; writing—review and editing, A.F.; visualization, G.T. and D.R.; supervision, A.F.; project administration, L.R..; funding acquisition, L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Council of Lithuania and the Ministry of Economy and Innovation (Project “Effectiveness and safety of the use of Lithuania’s unique natural resources for improving the mental and physical health of the organism experiencing stress” (LUGISES) grant number S-REP-22-6).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Kaunas Regional Research Ethics Committee (permission code BE-2-87 and date of approval 28 of November 2022), and registered in ClinicalTrial.gov (Identifier: NCT06018649) (30/08/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the chief executives and staff of research centers of Gradiali, Eglė, Draugystė, Tulpė, Versmė, and Atostogų parkas and colleagues of Klaipeda University who helped to carry out this large-scale research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BT |

Balneotherapy |

| ABT |

Balneotherapy by ambulatory/outpatient mode |

| ABTNT |

Balneotherapy combined with nature therapy by ambulatory/outpatient mode |

| BTS |

Balneotherapy by stationary/inpatient mode |

| NT |

Nature therapy |

| C |

Control group |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Figure A1.

The location of medical spas participated in the study (made by prof.dr. I. Dailidienė).

Figure A1.

The location of medical spas participated in the study (made by prof.dr. I. Dailidienė).

Appendix A.2

Figure A2.

The flow diagram of the study.

Figure A2.

The flow diagram of the study.

References

- McEwen, B.; Sapolsky, R. Stress and Your Health. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cay, M.; Ucar, C.; Senol, D.; Cevirgen, F.; Ozbag, D.; Altay, Z.; Yildiz, S. Effect of Increase in Cortisol Level Due to Stress in Healthy Young Individuals on Dynamic and Static Balance Scores. North Clin. Istanb. 2018, 5(4), 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaribeygi, H.; Panahi, Y.; Sahraei, H.; Johnston, T. P.; Sahebkar, A. The Impact of Stress on Body Function: A Review. EXCLI J. 2017, 16, 1057–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Zheng, L.; Xu, H.; Pang, Q.; Ren, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, T. Neurobiological Links between Stress, Brain Injury, and Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 8111022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algamal, M.; Saltiel, N.; Pearson, A. J.; et al. Impact of Repetitive Mild Traumatic Brain Injury on Behavioral and Hippocampal Deficits in a Mouse Model of Chronic Stress. J. Neurotrauma 2019, 36, 2590–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiropoulos, I.; Silva, J. M.; Gomes, P.; Sousa, N.; Almeida, O. F. X. Stress and the Etiopathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease and Depression. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1184, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Meng, Y.; Chen, G.; et al. Chronic Restraint Stress Exacerbates Neurological Deficits and Disrupts the Remodeling of the Neurovascular Unit in a Mouse Intracerebral Hemorrhage Model. Stress 2020, 23, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Chen, X.; Xu, H.; et al. Restraint Stress Delays the Recovery of Neurological Impairments and Exacerbates Brain Damage through Activating Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Mediated Neurodegeneration/Autophagy/Apoptosis Post Moderate Traumatic Brain Injury. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 1560–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Dong, J.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, A.; Chao, J.; Yao, H. Repeated Restraint Stress Increases Seizure Susceptibility by Activation of Hippocampal Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Neurochem. Int. 2017, 110, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynard, A. K.; et al. A Systematic Review of Stress-Management Interventions for Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Int. J. MS Care 2014, 16, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugama, S.; et al. Chronic Restraint Stress Triggers Dopaminergic and Noradrenergic Neurodegeneration: Possible Role of Chronic Stress in the Onset of Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Behav. Immun.

- Song, H.; Sieurin, J.; Wirdefeldt, K.; et al. Association of Stress-Related Disorders with Subsequent Neurodegenerative Diseases. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupriyanov, R.; Zhdanov, R. The Eustress Concept: Problems and Outlooks. World J. Med. Sci. 2014, 11, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eredoro, C.; Egbochuku, O. Overview of Stress and Stress Management. ARC J. Nurs. Health Care 2019, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; et al. Complex Interactive Multimodal Intervention to Improve Personalized Stress Management Among Healthcare Workers in China: A Knowledge Translation Protocol. Digit. Health 2023, 9, 20552076231184052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapolienė, L.; Razbadauskas, A.; Sąlyga, J.; Martinkėnas, A. Stress and Fatigue Management Using Balneotherapy in a Short-Time Randomized Controlled Trial. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, e9631684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti, A.; Karagülle, M.; Bender, T.; Karagülle, M. Z. Balneotherapy in Osteoarthritis: Facts, Fiction, and Gaps in Knowledge. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2017, 9, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamioka, H.; et al. A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials on Curative and Health Enhancement Effects of Forest Therapy. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2012, 5, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; et al. A Novel Approach to Assess Balneotherapy Effects on Musculoskeletal Diseases—An Open Interventional Trial Combining Physiological Indicators, Biomarkers, and Patients’ Health Perception. Geriatrics 2023, 8, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark-Kennedy, J.; Cohen, M. Indulgence or Therapy? Exploring the Characteristics, Motivations, and Experiences of Hot Springs Bathers in Victoria, Australia. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, Y.; Hayasaka, S.; Kurihara, S.; Nakamura, Y. Physical and Mental Effects of Bathing: A Randomized Intervention Study. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2018, 9521086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, P. L.; et al. Benefits of a 3-Week Outpatient Balneotherapy Program on Patient-Reported Outcomes. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 33, 1389–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, M.; Donelli, D. Effects of Balneotherapy and Spa Therapy on Levels of Cortisol as a Stress Biomarker: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 62, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badger, T. A.; Segrin, C.; Meek, P. Development and Validation of an Instrument for Rapidly Assessing Symptoms: The General Symptom Distress Scale. J. Pain Symptom Manage 2011, 41, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, I. R.; Cunningham, V.; Caspi, O.; Meek, P.; Ferro, L. Development and Validation of a New Global Well-Being Outcomes Rating Scale for Integrative Medicine Research. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2004, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clow, A.; Smyth, N. Salivary Cortisol as a Non-Invasive Window on the Brain. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2020, 150, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, D.; et al. Green Exercise and Mg-Ca-SO₄ Thermal Balneotherapy for the Treatment of Non-Specific Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, S. Evaluation of the Role of Balneotherapy in Rehabilitation Medicine. J. Nippon Med. Sch. 2018, 85, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, V. L.; et al. What Is the Best Mix of Population-Wide and High-Risk Targeted Strategies of Primary Stroke and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention? J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e014494.0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzer, F.; Bahadori, B.; Fazekas, C. Short-Term Balneotherapy Is Associated with Changes in Salivary Cortisol Levels. Endocrine Abstracts 2011, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Qin, Q.-Z.; Han, L.-L.; Lin, J.; Chen, Y. Spa Therapy (Balneotherapy) Relieves Mental Stress, Sleep Disorder, and General Health Problems in Sub-Healthy People. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 62, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti, A.; Cantarini, L.; Guidelli, G. M.; Galeazzi, M. Mechanisms of Action of Spa Therapies in Rheumatic Diseases: What Scientific Evidence Is There? Rheumatol. Int. 2011, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonelli, M.; Donelli, D.; Veronesi, L.; Vitale, M.; Pasquarella, C. Clinical Efficacy of Medical Hydrology: An Umbrella Review. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2021, 65, 1597–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gálvez, I.; Fioravanti, A.; Ortega, E. Spa Therapy and Peripheral Serotonin and Dopamine Function: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2024, 68, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falagas, M. E.; et al. The Effect of Psychosocial Factors on Breast Cancer Outcome: A Systematic Review. Breast Cancer Res. 2007, 9, R44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzer, F.; Nagele, E.; Bahadori, B.; Dam, K.; Fazekas, C. Stress-Relieving Effects of Short-Term Balneotherapy: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study in Healthy Adults. Forsch. Komplementmed. 2014, 21, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, M.; Morimoto, K.; Nagasawa, S.; Kitamura, K. Change in Salivary Physiological Stress Markers by Spa Bathing. Biomed. Res. 2006, 27, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushikoshi-Nakayama, R.; et al. Evaluation of the Benefits of Neutral Bicarbonate Ionized Water Baths in an Open-Label, Randomized, Crossover Trial. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, O.; Dubois, B. 170 Ans de Recours aux Soins Hydrothérapiques: L’Apport des Thermes de Saujon. Ann. Médico-Psychol. Rev. Psychiat. 2022, 180, 1090–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

The characteristics of study participants.

Table 1.

The characteristics of study participants.

| Parameters |

6ABT

N=59 |

11ABT

N =63 |

11ABTNT

N =63 |

11BTS

N =61 |

11NT

N =43 |

11C

N=51 |

6ABTS

N=30 |

11ABTS

N=29 |

χ2,p-value |

| Age, years ± SD |

45.3± 10.0 |

49.0±11.5 |

46.3±10.1

|

49.0 ±10.5 |

44.8 ±12.8 |

46.0±10.9 |

45.5±12.1 |

48.3±10.6 |

0.279a

|

| BMIa ± SD |

26.6±5.3 |

26.4±4.9 |

2673±5.5 |

27.1±4.5 |

25.6±4.5 |

27.0±5.5 |

24.7±3.6 |

27.4±5.6 |

0.447 |

| Gender, Female (%) |

44 (75.9) |

47 (87) |

41 (66.1) |

44 (72.1) |

34 (79.1) |

37 (77.1) |

26 (86.7) |

21 (75) |

0.108 |

| Marital status, Married N (%) |

45 (77.6) |

35 (64.8) |

42 (68.9) |

35 (60.3) |

26 (65.0) |

36 (75.0) |

19 (65.5) |

22 (78.6) |

0.355 |

| Education, University level N (%) |

39 (67.2) |

33 (61.1) |

29 (47.5) |

37 (62.7) |

31 (75.6) |

32 (66.7) |

23 (76.7) |

18 (64.3) |

0.085 |

| Profession, White-collar N (%) |

29 (50.0) |

25 (47.2) |

27 (44.3) |

35 (59.3) |

23 (56.1) |

21 (43.8) |

18 (62.1) |

12 (42.9) |

0.523 |

| Nature of work, Sedentary N (%) |

31 (53.4) |

22 (40.7) |

28 (48.3) |

29 (50.9) |

22 (53.7) |

18 (38.3) |

17 (58.6) |

11 (39.3) |

0.946 |

| Work experience,>20 years N (%) |

33 (56.9) |

27 (50.0) |

34 (55.7) |

40 (67.8) |

24 (60.0) |

25 (52.1) |

18 (62.1) |

21 (75.0) |

0.169 |

| Working time, ≤ 8 hours N (%) |

29 (50.0) |

32 (59.3) |

30 (50.0) |

24 (43.6) |

20 (52.6) |

22(45.8) |

15 (53.6) |

13 (46.4) |

0.989 |

| Rest time,7-8 hours N (%) |

24 (41.4) |

24 (45.3) |

26 (43.3) |

23 (39.0) |

21 (52.5) |

23 (50.0) |

18 (62.1) |

11 (40.7.4) |

0.797 |

| Covid-19 infection N (%) |

39 (67.2) |

31 (57.4) |

41 (66.1) |

32 (54.0) |

21 (52.5) |

30 (62.3) |

17 (58.6) |

21 (75.0) |

0.551 |

| Alcohol consumption, 2-3 times/week N (%) |

23 (39.7) |

19 (35.2) |

20 (32.8) |

20 (33.9) |

13 (31.7) |

20 (41.7) |

11 (36,7) |

9 (32.1) |

0.534 |

| Non-smoking N (%) |

44 (74.6) |

43 79.6) |

48 (77.4) |

50 (84.7) |

36 (85.7) |

35 (74.5) |

25 (83.3) |

22 (81,5) |

0.761 |

Physical activity, 2-3 times/week

N (%) |

18(30.5) |

20 (37.0) |

15 (24.2) |

21 (35.6) |

20 (46.5) |

15(31.3) |

17 (56.7) |

8 (28.6) |

0.235 |

| Stress intensity (VAS)±SD |

6.4± 2.3 |

6.1± 2.1 |

6.4± 2.7 |

6.0± 1.6 |

4.6 ±2.0 |

5.2 ±2.1 |

4.4± 2.5 |

4.8 ±2.3 |

<0.001a

|

| Stress management (VAS) ± SD |

6.5±1.6 |

5.5±1.7 |

6.4±2.4 |

5.0±1.6 |

6.7±2.2 |

6.7±1.6 |

6.6±2.3 |

6.5±2.4 |

<0.001a

|

Table 2.

The distress symptoms change in winter season study groups after treatment period.

Table 2.

The distress symptoms change in winter season study groups after treatment period.

| |

|

6ABTa

N=59 |

11ABTb

N=63 |

11ABTNTc

N=63 |

11SBTd

N=61 |

1NTe

N=43 |

11Cf

N=51 |

| |

|

Mean

(±SD) |

P

Effect |

Mean (±SD) |

P

Effect |

Mean (±SD) |

P

Effect |

Mean (±SD) |

P

Effect |

Mean (±SD) |

P

Effect |

Mean (±SD) |

P

Effect |

| Fatigue |

BT |

5.4±2.6 |

<0.001 |

5.4±2.3 |

<0.001 |

4.7±2.7 |

<0.001 |

5±2.2 |

<0.001 |

4±2.9 |

0.14 |

4.8±2.4 |

0.010 |

| |

AT |

1.6±2,1 |

1.2 |

2.6±2.6 |

1.2 |

2.5±2.2 |

0.8 |

1.2±1.9 |

1.5 |

3.4±2.4 |

0.2 |

3.5±2.3 |

0.1 |

| Sleep |

BT |

3.1±3.4 |

<0.001 |

2.9±2.6 |

<0.001 |

4.1±3.6 |

<0.001 |

4.5±2.5 |

<0.001 |

2.3±2.5 |

0.95 |

3±2.4 |

0.659 |

| |

AT |

1.5±2.5 |

0.6 |

1.8±2.6 |

0.5 |

1.7±2.6 |

0.6 |

2.7±2.4 |

0.7 |

2.3±2.6 |

0.01 |

2.8±2.6 |

-0.2 |

| Pain |

BT |

2.1±2.6 |

<0.001 |

2.4±2.8 |

<0.001 |

1.5±2.1 |

0.731 |

2.0±3.1 |

<0.001 |

2.3±3 |

0.004 |

2±2.3 |

0.703 |

| |

AT |

0.6±1.1 |

0.6 |

0.9±1.5 |

0.6 |

1.4±2.2 |

0.4 |

1.3±2.1 |

0.8 |

1.7±2.4 |

0.5 |

2.1±2.4 |

-0.3 |

| Headache |

BT |

2.6±2.8 |

<0.001 |

2±2.3 |

<0.001 |

1.3±1.5 |

0.067 |

1.3±1.8 |

0.003 |

1.9±2.5 |

0.014 |

0.9±1.6 |

0.857 |

| |

AT |

0.8±1.5 |

0.9 |

0.9±1.7 |

0.6 |

0.8±1.7 |

0.2 |

0.7±1.4 |

0.4 |

0.9±1.7 |

0.4 |

1±1.8 |

-0.3 |

| Anxiety |

BT |

3.8±3.5 |

<0.001 |

4.1±3.2 |

<0.001 |

4.4±3.3 |

<0.001 |

4.3±2.5 |

<0.001 |

2.6±2.6 |

0.109 |

2.9±2.9 |

0.081 |

| |

AT |

1.6±2.2 |

0.8 |

1.9±2.3 |

1.0 |

2.3±2.4 |

0.8 |

1.9±2.1 |

1.1 |

2±2.1 |

0.3 |

2.2±2.4 |

-0.03 |

| Depresion |

BT |

2.1±3.4 |

<0.001 |

1.6±2.9 |

<0.001 |

2.5±3.5 |

0.002 |

1.3±1.7 |

0.012 |

0.7±1.5 |

0.132 |

0.7±1.6 |

0.488 |

| |

AT |

0.8±1.8 |

0.6 |

0.6±1.4 |

0.5 |

1.4±2.2 |

0.4 |

0.6±1.6 |

0.3 |

0.4±0.7 |

0.2 |

0.5±1.3 |

-0.2 |

| Memory |

BT |

3.4±3.2 |

<0.001 |

2.9±3.1 |

<0.001 |

3.7±3.1 |

<0.001 |

3.5±2.4 |

<0.001 |

2±2.5 |

0.110 |

2.3±2.6 |

0.525 |

| |

AT |

0.6±1.3 |

0.8 |

1.6±2.2 |

0.6 |

1±1.5 |

0.8 |

1.9±2 |

0.6 |

1.4±2 |

0.3 |

2.1±2.6 |

-0.2 |

| Appetite |

BT |

1.4±2.6 |

<0.001 |

1.3±2.6 |

0.002 |

2±3.1 |

<0.001 |

1.3±2.2 |

<0.001 |

0.1±0.8 |

0.125 |

0.4±1.1 |

0.462 |

| |

AT |

0.3±1.1 |

0.5 |

0.2±0.8 |

0.4 |

0.4±1.4 |

0.5 |

0.7±1.5 |

0.6 |

0.4±1.1 |

-0.2 |

0.3±0.8 |

-0.2 |

| Nausea |

BT |

0.2±0.9 |

0.062 |

0.2±0.6 |

0.019 |

0.7±1.4 |

<0.001 |

0.2±0.4 |

<0.001 |

0.1±0.8 |

0.156 |

0.2±0.5 |

0.351 |

| |

AT |

0.1±0.3 |

0.3 |

0.1±0.3 |

0.3 |

0.2±0.8 |

0.5 |

0±0.2 |

0.5 |

0.5±1.7 |

-0.2 |

0.1±0.4 |

0.1 |

| Vomiting |

BT |

0.1±0.7 |

0.340 |

0.1±0.3 |

- |

0.2±0.7 |

0.033 |

0±0.1 |

0.321 |

0 |

0.323 |

0.1±0.7 |

0.180 |

| |

AT |

0.02±0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1±0.3 |

- |

0 |

0.3 |

0 |

0.1 |

0.1±0.3 |

-0.2 |

0 |

0.2 |

| Obstipation |

BT |

1.6±2.4 |

<0.001 |

1.7±2.6 |

0.005 |

1.6±2.6 |

0.002 |

0.6±1.2 |

0.005 |

0.6±1.7 |

0.246 |

1.7±2.7 |

0.007 |

| |

AT |

0.2±0.6 |

0.6 |

0.8±1.4 |

0.4 |

0.5±1.3 |

0.4 |

0.3±1.2 |

0.4 |

0.9±2.3 |

-0.2 |

2.4±3.4 |

-0.4 |

| Diarhea |

BT |

0.4±1.3 |

0.016 |

0.5±1.3 |

0.162 |

0.8±1.8 |

0.002 |

0.7±1.8 |

0.006 |

0 |

0.046 |

0.1±0.2 |

0.322 |

| |

AT |

0.0±0.1 |

0.3 |

0.6±1.4 |

-0.2 |

0.1±0.3 |

0.4 |

0.3±0.8 |

0.4 |

0.6±1.8 |

-0.3 |

0.2±0.8 |

-0.1 |

| Tingling |

BT |

0.7±1.7 |

0.197 |

2.7±3.2 |

<0.001 |

1.6±2.6 |

0.013 |

1.5±2 |

<0.001 |

0.9±1.9 |

0.242 |

1.4±2 |

0.016 |

| |

AT |

0.4±1.2 |

0.2 |

1.2±2.2 |

0.5 |

0.7±1.8 |

0.3 |

0.4±1.1 |

0.8 |

0.6±1.3 |

0.2 |

0.8±1.4 |

0.4 |

| Rash |

BT |

1.9±3.0 |

<0.001 |

1.6±2.8 |

0.004 |

2.3±2.9 |

0.008 |

0.8±1.5 |

0.059 |

0.8±2.1 |

0.199 |

1.1±2.1 |

0.355 |

| |

AT |

0.5±1.3 |

0.5 |

0.6±1.2 |

0.4 |

1.2±2.1 |

0.4 |

0.4±1.3 |

-0.0 |

1.3±3 |

-0.2 |

0.8±1.8 |

0.1 |

Table 3.

The distress symptoms change in summer season groups after treatment period.

Table 3.

The distress symptoms change in summer season groups after treatment period.

| |

|

6ABTSg (N=30) |

11ABTSh (N=29) |

Between-group comparison |

| |

|

Mean (±SD) |

P

Effect |

Mean (±SD) |

P

Effect |

BT

p / sig. diff. groups |

AT

p/ sig. diff. groups |

| Fatigue |

BT |

3.5±2.3 |

0.002 |

4±2.7 |

<0.001 |

0.003 |

<0.001 |

| |

AT |

2.1±2.4 |

0.6 |

1.5±2.1 |

1.0 |

a, b vs. g |

a vs. e, f, b, c vs. d, d vs. e, f, e, f vs. h |

| Sleep |

BT |

1.6±2.5 |

0.718 |

1.9±2.3 |

0.039 |

<0.001 |

0.002 |

| |

AT |

1.4±2.2 |

0.1 |

0.8±1.6 |

0.4 |

c, d vs. e, g, h |

d vs. h, f vs. h |

| Pain |

BT |

1.1±1.5 |

0.389 |

1.9±2.5 |

0.003 |

0.033 |

0.002 |

| |

AT |

0.8±1.6 |

0.2 |

0.8±1.6 |

0.6 |

c vs. d, d vs. g |

a, b vs. f |

| Headache |

BT |

0.9±1.7 |

0.255 |

0.9±1.6 |

0.129 |

<0.001 |

0.796 |

| |

AT |

0.5±1 |

0.2 |

0.4±0.9 |

0.3 |

a vs. c, d, f, g. h |

- |

| Anxiety |

BT |

1±1.7 |

0.037 |

2.6±2.7 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.001 |

| |

AT |

0.4±0.8 |

0.4 |

0.8±1.5 |

0.7 |

a, b, c, d vs. g, c vs. e |

b, c, d, e, f vs. g |

| Depresion |

BT |

0.1±0.7 |

0.476 |

0.6±1.4 |

0.275 |

<0.001 |

0.002 |

| |

AT |

0.0±0.2 |

0.1 |

0.3±1.5 |

0.2 |

a, c vs. g, c vs. e, f, h |

c vs. e, g, h |

| Memory |

BT |

1.1±1.8 |

0.637 |

2.2±2.6 |

0.003 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| |

AT |

1±1.5 |

0.1 |

0.8±1.4 |

0.6 |

a, c, d vs. g, c vs. e |

a vs. d, f, c vs. f |

| Appetite |

BT |

0.0±0.2 |

- |

0.2±1 |

0.742 |

<0.001 |

0.200 |

| |

AT |

0.0±0.2 |

- |

0.3±1.3 |

-0.1 |

c vs. e, f, g, h |

- |

| Nausea |

BT |

0.1±0.3 |

1 |

0 |

- |

<0.001 |

0.015 |

| |

AT |

0.1±0.4 |

0 |

0 |

- |

a, b vs. c, c vs. d, e, f, g, h |

a, b, d vs. e, e vs. h |

| Vomiting |

BT |

0.0±0.2 |

0.326 |

0 |

- |

0.345 |

0.146 |

| |

AT |

0 |

0.2 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

| Obstipation |

BT |

0.8±2.1 |

0.083 |

0.3±1.1 |

0.326 |

0.003 |

<0.001 |

| |

AT |

0.6±2 |

0.3 |

0.2±0.6 |

0.2 |

a, b, c vs. h |

a, b, c, d, e vs. f, f vs. g, h |

| Diarhea |

BT |

0.0±0.2 |

0.326 |

0.2±0.6 |

0.477 |

0.003 |

0.002 |

| |

AT |

0.1±0.3 |

-0.2 |

0.1±0.4 |

0.1 |

c vs. e, f |

a vs. b, b vs. c |

| Tingling |

BT |

0.5±0.9 |

0.095 |

1.1±1.9 |

0.035 |

<0.001 |

0.015 |

| |

AT |

0.2±0.5 |

0.3 |

0.3±1 |

0.4 |

a vs. b, b vs. e, g, h |

b vs. d, g |

| Rash |

BT |

0.9±2.1 |

0.03 |

0.7±1.5 |

0.313 |

0.004 |

0,034 |

| |

AT |

0.5±1.4 |

0.4 |

0.3±1 |

0.2 |

c vs. d, h |

c, e vs. d, h |

Table 4.

The results of regression analysis for distress intensity.

Table 4.

The results of regression analysis for distress intensity.

| |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

t |

Sig. |

95.0% Confidence Interval for B |

Collinearity Statistics |

| |

B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

Tolerance |

VIF |

| (Constant) |

40.40 |

12.17 |

|

3.32 |

0.001 |

16.42 |

64.37 |

|

|

| Work and social adaptation |

0.46 |

0.10 |

0.32 |

4.78 |

<0.001 |

0.27 |

0.64 |

0.65 |

1.53 |

| Percieved stress scale |

0.26 |

0.20 |

0.11 |

1.34 |

0.181 |

-0.123 |

0.647 |

0.39 |

2.54 |

| Fatigue |

-0.16 |

0.21 |

-0.05 |

-0.77 |

0.44 |

-0.57 |

0.25 |

0.58 |

1.74 |

| Anxiety_state |

1.97 |

0.47 |

0.33 |

4.16 |

<0.001 |

1.036 |

2.898 |

0.47 |

2.15 |

| Anxiety_trait |

-1.27 |

0.38 |

-0.29 |

-3.37 |

<0.001 |

-2.01 |

-0.53 |

0.39 |

2.55 |

| Depression |

-0.15 |

0.12 |

-0.11 |

-1.28 |

0.20 |

-0.38 |

0.08 |

0.38 |

2.65 |

| Integrative oustcomes scale |

-2.06 |

0.57 |

-0.26 |

-3.60 |

<0.001 |

-3.19 |

-0.93 |

0.56 |

1.79 |

| Sleep |

-0.31 |

0.49 |

-0.04 |

-0.64 |

0.53 |

-1.27 |

0.65 |

0.65 |

1.55 |

| Systolic blood pressure |

0.05 |

0.07 |

0.05 |

0.69 |

0.49 |

-0.09 |

0.20 |

0.49 |

2.03 |

| Diastolic blood pressure |

-0.17 |

0.12 |

-0.12 |

-1.47 |

0.14 |

-0.40 |

0.06 |

0.47 |

2.15 |

| Heart rate |

0.04 |

0.07 |

0.03 |

0.52 |

0.61 |

-0.11 |

0.19 |

0.88 |

1.14 |

| Quality of life |

0.79 |

1.49 |

0.04 |

0.53 |

0.60 |

-2.15 |

3.72 |

0.54 |

1.87 |

| Pain, VAS |

0.71 |

0.43 |

0.10 |

1.66 |

0.10 |

-0.13 |

1.55 |

0.79 |

1.27 |

| Saliva cortisol |

0.09 |

0.41 |

0.01 |

0.22 |

0.83 |

-0.72 |

0.90 |

0.93 |

1.07 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).