1. Introduction

The impact of globalisation and technological advances, along with the modern challenges of urban stress and global health crises, has led to a growing disconnection between individuals and nature. This detachment has contributed to a deterioration in mental health, manifesting in heightened levels of depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental disorders [

1]. This was evident during the Covid-19 pandemic, as contact with nature was limited, leading to sociocultural and psychological repercussions [

2].

Studies on well-being associated with tourism [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8] mainly relate to the search for travel experiences that contribute to individuals' physical, mental, and emotional well-being, generating a new tourism market segment [

4]. However, before this potential can be realised, it is essential to determine whether nature-based tourism experiences have effects on mental health at the level of specific disorders such as depression, anxiety, and stress.

The purpose of this article is to demonstrate the effect of nature contact on the mental well-being of voluntary visitors with severe and extremely severe levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. The study hypothesis posits that tourism experiences involving nature contact significantly reduce levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, thereby promoting mental well-being. Over a six-month period, we examined what occurs before, during, and after a nature-based tourism experience. The research gap in this field lies in the lack of measurements of the lasting effect that nature-based tourism experiences produce over time. Thus, we contribute to the literature on how experiences involving nature contact can reduce the severe and extremely severe levels of these mental disorders.

The findings demonstrate that nature-based tourism experiences have a significant effect on reducing levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, thereby promoting individuals' mental well-being. Results indicate that such experiences lead to immediate and statistically significant improvements in mental well-being, with substantial effect sizes. However, while the benefits persist to some extent, they tend to diminish over time, suggesting the need for additional or more frequent interventions to sustain positive effects in the long term.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Nature Tourism and Mental Wellbeing

Tourism has the capacity to produce moderate to high wellbeing effects in tourists [

9]. Indeed, nature tourism is characterised by interaction with unaltered or minimally impacted environments, where the primary motivation of visitors is the observation and appreciation of nature and cultural manifestations [

10,

11]. This typology promotes various modalities of tourism activities, such as rural tourism, agritourism, wellness tourism, adventure tourism, health tourism, and ecotourism, among others [

6]. In any modality of nature tourism, the motivation of visitors is crucial, as the satisfaction derived from their experiences is intrinsically linked to the alignment of these with their prior expectations [

12,

13]. A variable that influences the perception of risk and safety is distance [

14]. This factor is critical in individuals' decision-making processes when planning trips, as people tend to select destinations that appear safe and promise relaxing and comforting experiences [

14,

15]. Indeed, nature tourism can be undertaken both in proximity to one's residence, allowing for frequent visits, as well as in distant destinations, which may be visited only once in a lifetime.

The World Health Organization in 2022 [

16] asserts that mental wellbeing is essential for overall health, encompassing emotional, psychological, and social balance, thereby facilitating resilience in the face of challenges, personal development, work efficacy, and community contributions. Mental wellbeing not only signifies the absence of mental disorders but also denotes a dynamic internal equilibrium that must be cultivated. This is key to managing stress, adapting to change, and maintaining a positive outlook [

17,

18,

19]. Authors [

20] emphasise the importance of connection and engagement with nature in promoting mental health. This connection is evidenced by studies reporting significant emotional benefits and stress recovery in nature tourists [

4]. Several authors corroborate that proximity to natural environments reduces stress, depression, and anxiety, thereby enhancing overall wellbeing [

21,

22,

23]. Recently, a key aspect has been the Covid-19 pandemic, which modified travel motivations, underscoring the need to address individuals' sociopsychological aspects such as socialisation, reflection, and relaxation [

24]. This highlights that travel is crucial for physical and mental wellbeing, as well as personal growth [

4,

22,

25,

26]. This underscores the profound connection between mental wellbeing and context, highlighting its relevance in tourism destination management.

Studies examining the relationship between tourism and mental wellbeing underscore the significance of recreational activities and contact with nature in enhancing mental health [

4,

27,

28]. Seervi in 2023 [

29] suggest that nature tourism promotes wellbeing sustainably. Authors [

25] highlight the importance of these natural environments for mental wellbeing, stressing the need to integrate environmental conservation into public health policies. Ke et al. [

30] point out the significance of sustainable practices in managing ecosystems such as mangroves, indicating a link between conservation and mental health. Clissold et al. [

6] found encouraging results regarding the restorative effects of nature. For instance, ecotourism promotes significant physical benefits, including stress reduction and maintenance of normal blood pressure and heart rate [

26], emphasising the relevance of incorporating natural elements and nature tourism into public and personal health strategies. There is indeed a consensus regarding the positive impact of tourism, particularly nature tourism, on physical, mental, and social wellbeing, making it essential for public health [

31].

2.2. Nature Tourism Experiences to Reduce Stress, Anxiety, and Depression

The interaction of humans with nature and its influence on mental wellbeing has been extensively documented in the scientific literature. Buckley and Cooper [

5] argue that mental health benefits arise from factors such as the destinations visited, activities undertaken, personal traits of tourists, and sensory, emotional, and experiential aspects, which enhance the intensity and persistence of positive memories. A research [

4] illustrates that excursions in national parks contribute to an immediate improvement in happiness and a medium-term alleviation of stress, although long-term effects require further study. Authors in 2017 [

32] contend that interaction with natural environments is significant for health and wellbeing, particularly in reducing anxiety and depression. Suárez Bata [

33] argues that tourism can serve as an effective adjunct in the treatment of depression by providing experiences that persist beyond the tourist visit, highlighting the importance of nature for emotional and mental recovery.

Authors [

34] demonstrated that ecotherapy, through activities in nature—such as healing forests—was an intervention to alleviate conditions of depression, anxiety, and stress. The results during the treatment suggest that such forests can be an effective strategy for mitigating stress. This provided important data for policy formulation and the future development of 'Healing Forest Ecotherapy'. A study was conducted about the effectiveness of forest bathing in improving mental wellbeing among adolescents, a group affected by an escalating mental health crisis, including anxiety and depression [

35]. Employing a participatory action research method with 24 young people aged 16 to 18 over three weeks, the findings, assessed using the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale, revealed a significant increase in mental wellbeing, with moderate to high effects. Participants reported reduced stress and an increase in sensations of relaxation, peace, and happiness.

A study examined the effects of personalised forest walks, utilising an algorithm that considers variables such as age, usual physical activity, fatigue level, and chronic illnesses to design tailored exercise programmes for 59 subjects [

36]. The results revealed significant improvements in physical and mental health, including reductions in blood pressure, body fat percentage, negative perceptions, and emotional exhaustion, demonstrating that forest walks benefit both physical and psychological health.

Marselle et al. [

37] explored the therapeutic potential of group walks in natural settings to enhance resilience and mitigate the impacts of stress on mental health. Through multiple regression analysis, considering variables such as age, gender, and recent physical activity, it was evidenced that the benefits of these activities outweigh the adverse effects of stress in areas such as depression, positive affect, and mental wellbeing. These findings indicate that group walks in nature are highly beneficial for mental health and stress resilience.

2.3. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Evaluated Using the DASS-21 Instrument

Depression, anxiety, and stress constitute a triad of mental health disorders with significant prevalence and marked impact on overall wellbeing. Depression is characterised by a persistent feeling of sadness and loss of interest or pleasure in normally enjoyable activities [

38], affecting over 300 million people and ranking among the top five disorders causing disability. Its symptoms include constant sadness, sleep and appetite disturbances, and fatigue. It presents a prevalence of up to 18% in developed countries, being more common in women and primarily affecting young adults [

39].

Anxiety, on the other hand, manifests through intense feelings of nervousness and fear, significantly impacting social, occupational, and personal functioning [

40]. It can provoke physical and cognitive symptoms such as restlessness, irritability, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, increased heart rate, and chest and abdominal pain [

41]. With a global prevalence of 7.3% and an increased risk in women, it is the most common mental disorder.

Stress, described as a disruption in normal physiological or psychological functioning, arises when personal resources are insufficient to meet the demands and pressures of the environment [

42]. Initially considered in physical terms, its understanding was broadened by Walter Cannon (1939) and Hans Selye (1983), who identified the physiological fight-or-flight responses and a range of symptoms predisposing individuals to various illnesses, affecting quality of life and health.

In recent literature concerning the evaluation of mental wellbeing, the DASS-21 scales have been recognised as a significant tool within the field of psychology. The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales (DASS) were developed by Lovibond and Lovibond (1995) to “assess the presence of negative effects of depression and anxiety and achieve maximum discrimination between these conditions, whose clinical overlap has been reported by clinicians and researchers” [

43]. Originally, these scales consisted of 42 items, which were subsequently condensed to a short version comprising 21 items [

44]. Chauhan et al. [

45] demonstrated their utility in monitoring the mental health of employees in the tourism industry, correlating it with levels of happiness and life satisfaction. They recommended the application of tools such as the WHO-5 Wellbeing Index and the DASS-21 scale. A study underscores the importance of the DASS-21 scale, revealing that the factors assessed by this instrument have a significant correlation with mental wellbeing, reinforcing its relevance as a reliable and predictive measurement tool for researchers and professionals of mental health [

46]. Also, a study highlights [

47] changes in mental wellbeing during the pandemic, suggesting the relevance of the DASS-21 in capturing variations in psychological states during times of crisis.

Vujcic et al. [

48] utilise the DASS-21 to assess the prevalence of these psychiatric disorders within a sample of students. Despite the limitation posed by a small sample size, the results indicated a notable relationship between sociodemographic variables and levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. This study underscores the utility of the DASS-21 as an effective instrument for identifying and addressing mental health issues in university populations. Septaviani et al. [

34] employ the DASS-42 scale, an extended version of the DASS-21, to measure stress, anxiety, and depression among university students participating in ecotherapy. Trevino et al. (2022) modify the DASS-21 instrument by incorporating the Academic Stress Scale (DASA) within a sample of students. Collectively, these studies consolidate the position of the DASS-21 as a cornerstone in the assessment and monitoring of psychological wellbeing.

The pandemic limited contact with nature, adversely affecting mental health and transforming tourism [

2,

49]. Factors such as urban environments, fear of contagion, and the digitalisation of daily life contributed to psychological and physical disorders, particularly impacting young individuals due to restrictions on socialisation, which is crucial for their emotional development [

50]. Indeed, outdoor activities during the pandemic provided a means of recovery for the tourism industry without the constraints of social distancing [

24]. In light of the increase in post-pandemic mental health issues, nature tourism emerges as an essential tool for recovery, offering benefits such as stress reduction and mood enhancement [

7,

51].

2.4. Designing the Tourism Experience

Non-pharmacological interventions are gaining recognition in mental health, particularly for treating anxiety, stress, and depression [

52,

53]. Nature-based tourism serves as an effective strategy for individuals with emotional disorders, provided it is carefully designed, taking into account key factors such as the environment, duration of the trip, and tourism services.

The selection of the environment is crucial in tourism experiences for individuals with high levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. It is fundamental to prioritise safety, accessibility, and landscape diversity, fostering a disconnection from everyday stress. Rural areas, national parks, and nature reserves, characterised by soothing sounds and rich biodiversity, promote psychological wellbeing. Spaces that combine forests, mountains, and bodies of water are particularly effective in reducing stress. Furthermore, accessibility, appropriate infrastructure, and quality of air free from pollutants are essential for enhancing the mental wellbeing of participants.

The distance to the tourist destination is critical for participants' experiences, as long journeys can exacerbate stress and anxiety. It is advisable to limit travel to 1-3 hours, as this reduces fatigue and facilitates a swift immersion into nature, maximising therapeutic benefits. Shorter distances also encourage frequent repetition of these experiences, creating cumulative effects on mental wellbeing and simplifying logistics, thereby reducing organisational burdens. Furthermore, the duration of the trip should balance exposure to nature with necessary time for rest and recovery, with a recommended duration of 3 to 7 hours to allow for effective immersion without leading to exhaustion. The first hour is particularly pivotal, enabling a gradual transition from the everyday environment to a therapeutic setting through mindfulness techniques or conscious breathing.

Transportation to and from the destination should be comfortable, direct, and free from prolonged interruptions or unnecessary transfers that could heighten anxiety. Private transport is ideal, as it provides a more controlled and relaxing environment; thus, training transportation staff to manage anxiety-inducing situations is essential for ensuring participants' wellbeing. The guide's role in nature tours for individuals with high stress, anxiety, and depression is also crucial, requiring training in both the natural environment and stress management techniques. Guided activities should be conducted at a leisurely pace, allowing for moments of silence and mindfulness practices that help participants focus on the sensory stimuli of their surroundings. Additionally, food offerings in tourism experiences should enhance physical and emotional wellbeing by providing fresh, local, seasonal, and preferably organic foods rich in key nutrients for mental health. Meals should be served in tranquil settings, ideally outdoors, to improve digestion and reduce stress, while mindful eating can further contribute to relaxation and overall wellbeing.

3. Methodology

This study was part of a project approved by the Research Bioethics Committee in the Health Area of the University of Cuenca (COBIAS) in accordance with regulations from the Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador. Once the project’s ethics protocol was approved, the research team, comprising professionals in tourism and clinical psychology, established contact with the student welfare departments of the participating higher education institutions. Authorisation was obtained to use the databases of scholarship students from both universities. The team then promoted the project to potential participants by email (289 students from the University of Cuenca and 218 students from the University of Azuay). Due to the pandemic, an online meeting was held through Zoom Meetings with interested participants to explain the implications of their involvement in the project. Subsequently, project details and informed consent forms were sent by email to encourage students' free and voluntary participation. Factors such as economic conditions, restrictive COVID-19 pandemic measures [

54,

55,

56], and the shift from face-to-face to online education [

57] contributed to exacerbating depression, anxiety, and stress levels within the student population.

The study employed a quantitative analytical approach using the DASS-21 test [

58] at three time points. We used a criterion-based sample focusing on severe and extremely severe levels in at least one dimension of the emotional disorders studied. We began with a sample of 507 scholarship students from two local universities in Cuenca, Ecuador. Of these, 214 students voluntarily completed the DASS-21 test during February-April 2022 via Kobo Toolbox. We then focused on 97 students who reported severe and extremely severe levels of depression, anxiety, or stress. However, only 67 students participated freely and voluntarily. The first time point involved administering the DASS-21 self-report (depression, anxiety, and stress) (N=67) prior to the nature-based tourism experience. The second time point entailed designing a nature-based tourism experience for students with severe levels of depression, anxiety, and stress (see 2.4). After the experience, the DASS-21 self-report was administered again (N=67). Cohen’s d effect size was then calculated to determine whether the nature-based tourism experience could be an effective non-pharmacological treatment for the disorders under study.

The third time point involved administering the DASS-21 self-report six months later to observe the stability—effect size—of the outcomes for participants in the study variables. A total of 57 students (N) out of 67 participated freely and voluntarily.

The data collection instrument used was the DASS-21, which contains 21 items to assess levels of depression, anxiety, and stress [

58,

59]. The scale has demonstrated appropriate psychometric properties in Spanish-speaking samples [

59]. For the Ecuadorian population, internal consistency was as follows: anxiety α = .79; depression α = .89; stress α = .80 (60).

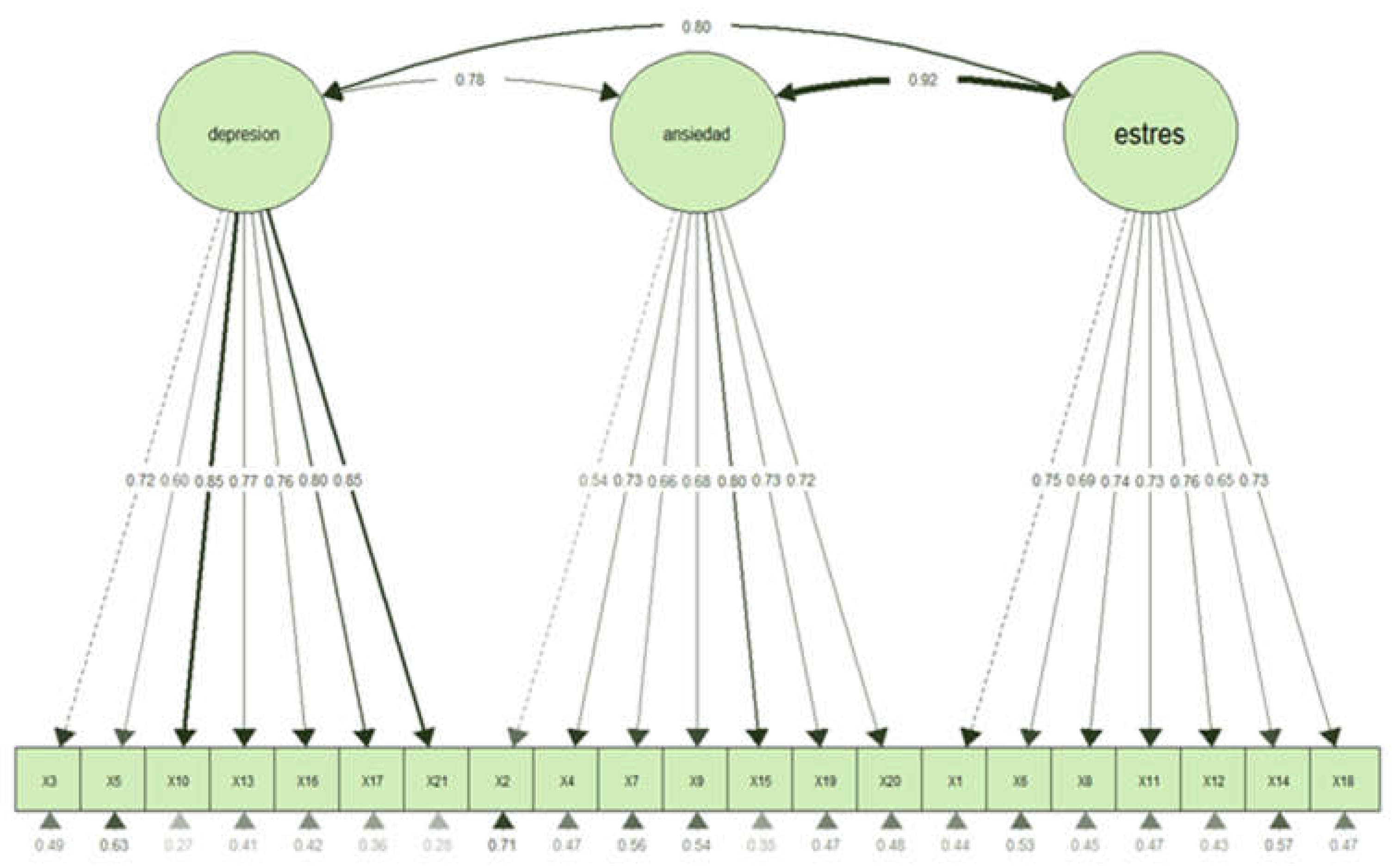

The internal consistency (reliability) of the DASS-21 was assessed, with its 21 questions (7 per clinical dimension) administered to 214 participants (n). Reliability was evaluated using hierarchical omega, yielding Ω = .78. The theoretical three-factor model (depression, anxiety, and stress) was also tested using the “DWLS” estimator (diagonally weighted least squares), with excellent results (SRMR = .054; RMSEA = .00; GFI = .99; NFI = .98; NNFI = .99), confirming the multidimensionality of the instrument (

Figure 1).

Study data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27. An exploratory descriptive analysis (EDA) was conducted, followed by paired t-tests to examine differences in clinical dimensions (depression, anxiety, and stress). Cohen's d effect size was calculated for the first and second time points, as well as the second and third, with Cohen (1998) suggesting small effect sizes ≈0.2, medium ≈0.5, and large ≈0.8.

4. Research Results

To evaluate the internal consistency of the DASS-21, which consists of 21 questions and 7 items for each clinical dimension, a sample of 214 participants was assessed, and reliability was estimated using the hierarchical omega coefficient. The result obtained was Ω = .78, indicating very good reliability for the instrument. Additionally, the theoretical model of three factors (depression, anxiety, and stress) was tested using the "DWLS" (diagonally weighted least squares) estimator, resulting in the following fit indices: SRMR ≈ .054; RMSEA ≈ .00; GFI ≈ .99; NFI ≈ .98; NNFI ≈ .99. These results support the multidimensionality of the instrument and the appropriateness of the proposed measurement model.

4.1. Exploratory Descriptive Analysis

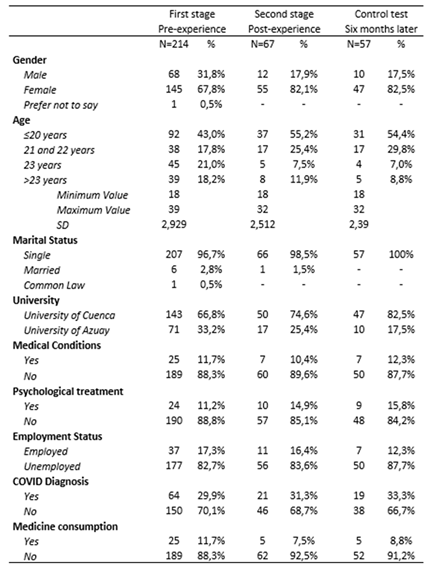

The sociodemographic data provided (

Table 1) reflect a series of three measurement points within a population, including a pre-experience, post-experience, and a control test six months later. The sample is predominantly female, with a consistent majority across all measurements. Age distribution indicates a higher concentration of individuals under 23 years in the pre-experience phase, which appears to decrease slightly in subsequent measurements, suggesting a possible initial preference among younger participants or a stronger initial interest from this demographic.

The predominant gender in the sample is female, maintaining a stable majority throughout all assessments. Age distribution reveals a higher concentration of participants under the age of 23 in the pre-experience phase, which seems to decrease slightly in subsequent measurements. This shift may suggest a potential selection effect favouring younger participants or an initial interest within this demographic group. In terms of marital status, the vast majority of participants are single, a trend that remains consistent across all assessments. This may correlate with the predominant age group, likely reflecting a sample primarily composed of university students, as confirmed by the large proportion of individuals affiliated with the University of Cuenca. A significant minority of participants reported having medical conditions and receiving psychological care, with minimal change in these percentages across the three measurements, indicating relative stability in health and psychological well-being within this population.

The employment status of participants reveals that the majority are unemployed, likely due to the high proportion of students. Notably, there is an increase in the proportion of participants diagnosed with COVID-19 in the post-experience phase compared to the pre-experience phase, highlighting the pandemic's impact on the study population. Finally, medication use remains low and consistent, suggesting limited variation in medical treatment across the measurement points.

4.2. Effect of Nature-Based Tourism Experiences on Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Disorders

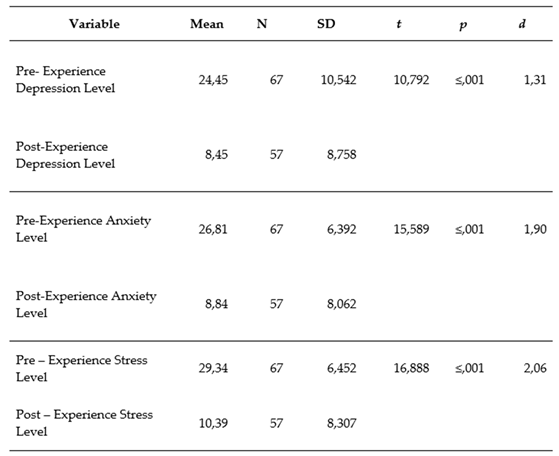

The results in

Table 2 indicate that the tourism experience had a significant and positive impact on reducing levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. All changes in pre- and post-experience means are statistically significant. The effect sizes (d) range from large to very large (1.31 to 2.06), indicating that the observed improvements in these clinical variables are both statistically and clinically meaningful.

The significant reduction in mean depression levels before and after the tourism experience, with a t-value of 10.792 and a p-value ≤ 0.001, demonstrates that the decrease in depression levels is statistically significant. The effect size (d = 1.31) suggests a large effect, indicating that the tourism experience had a substantial impact on reducing depression levels.

Similarly, the decrease in anxiety levels is also significant, with a t-value of 15.589 and a p-value ≤ 0.001, indicating a statistically significant reduction. The effect size (d = 1.90) suggests a very large effect, showing that the tourism experience had a strong impact on reducing anxiety levels.

The reduction in stress levels is also significant, with a t-value of 16.888 and a p-value ≤ 0.001, indicating a statistically significant decrease. The effect size (d = 2.06) suggests a very large effect, highlighting that the tourism experience had a powerful impact on reducing stress levels.

4.3. Six-Month Follow-Up of the Study Group

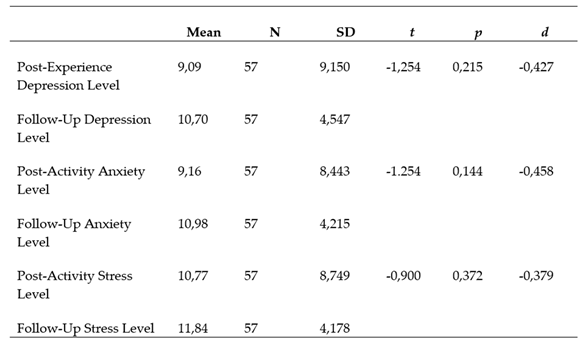

Table 3 shows that p-values across all dimensions exceed 0.05, indicating no statistically significant differences between levels immediately after the tourism experience and six months later. Although effect sizes range from moderate to small, they are not considered clinically relevant. The sample consists of 57 participants, as 10 individuals opted out of the follow-up.

Regarding depression levels, there was an increase at the six-month follow-up (from 9.09 to 10.70), though the t-value is not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Cohen’s effect size (d = -0.427) indicates a moderate effect, but not one that is clinically relevant. Anxiety levels also increased similarly at the six-month follow-up. The t-value is not statistically significant (p > 0.05), and the effect size (d = -0.458) suggests a moderate effect, though not clinically relevant. Stress levels also rose during follow-up. The t-test is not statistically significant (p > 0.05), and the effect size (d = -0.379) suggests a small to moderate effect.

These results suggest that the immediate benefits gained following the tourism experience did not persist in the long term.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study demonstrates that contact with nature through tourism experiences promotes mental well-being by reducing levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. The statistically significant differences in depression, anxiety, and stress levels between the post-tourism experience and the six-month follow-up suggest that the immediate benefits gained following the tourism experience were sustained over the long term. This finding can be interpreted as a positive indication that the intervention (the tourism experience) had enduring effects, meeting the study's objective.

The data strongly support the study hypothesis, suggesting that nature-based tourism experiences significantly reduce depression, anxiety, and stress, thereby enhancing mental well-being. The results reveal statistically significant reductions in depression (t = 10.792, p ≤ 0.001), anxiety (t = 15.589, p ≤ 0.001), and stress (t = 16.888, p ≤ 0.001) levels following the tourism experience. Effect sizes were large for depression (d = 1.31), very large for anxiety (d = 1.90), and very large for stress (d = 2.06), indicating a substantial impact on mental well-being.

However, at the six-month follow-up, p-values exceeded 0.05, suggesting that observed differences were no longer statistically significant over the long term. Effect sizes (d = -0.379 to -0.458) were small to moderate, indicating that immediate benefits diminished over time and were not clinically relevant at follow-up. This suggests that although nature-based tourism experiences produce a significant short-term improvement in mental well-being, sustaining these effects over the long term may require additional or more frequent interventions.

Various studies agree that nature contact benefits both physical and mental health [

4,

22,

26]. Similar studies, such as that by Richardson et al. [

20], indicate that simple activities (e.g., smelling flowers) in nature promote mental health and well-being. Accordingly, our study proposes a set of simple activities assembled into a tourism experience to promote mental well-being. Our findings align with Buckley et al. [

4], where participants reported that nature induced feelings of happiness and short-term health improvement, with a moderate number reporting medium-term recovery, and a much smaller proportion reporting long-term effects. Similarly, our study results are consistent with Buckley et al. [

4], in which participants reported that nature contact has positive effects on short-term happiness and health. Additionally, a moderate group of participants experienced medium-term recovery, while a significantly smaller proportion reported long-term benefits. Thus, we may infer that the influence of nature activities on well-being and mental health tends to decrease over time. This suggests that sustaining long-term effects might require more frequent and consistent interaction with nature or incorporating these experiences into everyday life to prolong their benefits. Like Maxwell & Lovell [

32], we concur that biodiversity is essential for human well-being. We also agree with Alipour et al. [

31] that tourism experiences contribute to health improvement and are vital for public health in societies.

This study advances knowledge in the field of tourism and mental well-being by providing robust evidence of the short-term positive impact of nature-based tourism experiences on reducing depression, anxiety, and stress. However, the six-month follow-up adds an important nuance to this narrative, indicating that while benefits are substantial in the short term, they tend to wane over time. This provides critical insight into the need for additional or repeated interventions to sustain long-term effects. The study, therefore, not only confirms the effectiveness of nature-based tourism experiences for mental well-being but also highlights the importance of frequency and continuity in such experiences to maintain long-term benefits. Nature-based tourism interventions hold significant potential for integration into mental health programmes, constituting an effective strategy for psychological well-being. At the same time, these interventions offer an opportunity for local communities and protected areas to develop tourism products that, through simple and accessible experiences, focus on the relationship between tourism and mental health. This diversifies tourism options and contributes to the sustainable development of communities and the conservation of natural resources by promoting activities that highlight the therapeutic benefits of contact with nature.

By measuring levels of depression, anxiety, and stress immediately after the experience and at a six-month follow-up, this study provides empirical evidence on the sustainability and evolution of mental well-being benefits. The study offers a deeper understanding of the temporality of the impact of nature-based tourism interventions, a dimension insufficiently explored in prior research. This insight guides future research towards the need for more frequent or ongoing interventions to maintain the benefits of these experiences, thereby contributing a more comprehensive and dynamic perspective to the field of tourism and mental health.

One significant influencing factor in this study was the design of the tourism experience. Despite careful planning, rain occurred during the activity, though the experience was adapted to incorporate simple activities allowing for contact with the rain, adding an unexpected but authentic component to the nature interaction. Additionally, it was observed that some participants were uncomfortable with the lack of mobile connectivity, which may also have influenced their perceptions and overall enjoyment of the tourism experience.

The study's limitations primarily relate to the sample used, as continuous participation from all individuals over time could not be ensured. This resulted in limitations in both the continuity of tourism experiences and in conducting longitudinal measurements. In this case, the sample consisted of university students, some of whom discontinued participation due to graduation or lack of availability for long-term project involvement. Nevertheless, this limitation opens opportunities for future research to include more continuous and sustained tourism interventions to explore whether beneficial effects on mental well-being diminish over time or whether there are factors influencing their maintenance.

In conclusion, this study confirms the proposed hypothesis, demonstrating that nature-based tourism experiences have a significant effect in reducing levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, thereby promoting individuals’ mental well-being. The results show that such experiences produce immediate and statistically significant improvements in mental well-being, with substantial effect sizes. However, while the benefits persist to some extent, they tend to diminish over time, suggesting the need for additional or more frequent interventions to maintain positive long-term effects. These findings contribute significantly to the field by providing empirical evidence on the efficacy and temporality of nature-based tourism interventions in promoting mental health.

References

- Grabowska-Chenczke, O.; Wajchman-Świtalska, S.; Woźniak, M. Psychological Well-Being and Nature Relatedness. Forests 2022, 13, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G. D.; Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Reviving Tourism Industry Post-COVID-19: A Resilience-Based Framework. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brymer, E.; Crabtree, J.; King, R. Exploring Perceptions of How Nature Recreation Benefits Mental Wellbeing: A Qualitative Enquiry. Ann. Leis. Res. 2021, 24, 394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Nature Tourism and Mental Health: Parks, Happiness, and Causation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1409–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. C.; Cooper, M.-A. Tourism as a Tool in Nature-Based Mental Health: Progress and Prospects Post-Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 13112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clissold, R.; Westoby, R.; McNamara, K. E.; Fleming, C. Wellbeing Outcomes of Nature Tourism: Mt Barney Lodge. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2022, 3, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartan, C.; Davidson, G.; Bradley, L.; Greer, K.; Knifton, L.; Mulholland, A.; Webb, P.; White, C. ‘Lifts Your Spirits, Lifts Your Mind’: A Co-produced Mixed-methods Exploration of the Benefits of Green and Blue Spaces for Mental Wellbeing. Health Expect. 2023, 26, 1679–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, C. The Contribution of Cultural Ecosystem Services to Understanding the Tourism–Nature–Wellbeing Nexus. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2015, 10, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelinčić, D. A.; Matečić, I. Broken but Well: Healing Dimensions of Cultural Tourism Experiences. Sustainability 2021, 13, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoletti, C.; Magro-Lindenkamp, T. C.; Sarriés, G. A. Adventure Races in Brazil: Do Stakeholders Take Conservation into Consideration? Environments 2019, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, J.; Goodwin, C.; Burn, J. F.; Leonards, U. How Visual Perceptual Grouping Influences Foot Placement. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2015, 2, 150151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandić, A.; McCool, S. F. Sustainable Visitor Experience Design in Nature-Based Tourism: An Introduction to the Special Issue. J. Ecotourism 2023, 22, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Uysal, M.; Kim, J.; Ahn, K. Nature-Based Tourism: Motivation and Subjective Well-Being. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, S76–S96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebli, A.; Volgger, M.; Taplin, R. A Two-Dimensional Approach to Travel Motivation in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, M.; Schmude, J. Understanding the Role of Risk (Perception) in Destination Choice: A Literature Review and Synthesis. Tour. Rev. 2017, 65, 138–155. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Mental health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response.

- Buckley, R.; Westaway, D. Mental Health Rescue Effects of Women’s Outdoor Tourism: A Role in COVID-19 Recovery. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaid, D.; Park, A.-L.; Wahlbeck, K. The Economic Case for the Prevention of Mental Illness. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 40, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdolini, N.; Amoretti, S.; Montejo, L.; García-Rizo, C.; Hogg, B.; Mezquida, G.; Rabelo-da-Ponte, F. D.; Vallespir, C.; Radua, J.; Martinez-Aran, A.; Pacchiarotti, I.; Rosa, A. R.; Bernardo, M.; Vieta, E.; Torrent, C.; Solé, B. Resilience and Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 283, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Passmore, H.-A.; Lumber, R.; Thomas, R.; Hunt, A. Supplementary Analyses for: Moments, Not Minutes: The Nature-Wellbeing Relationship. Int. J. Wellbeing 2021, 11, S1–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A. J.; Dopko, R. L.; Passmore, H.-A.; Buro, K. Nature Connectedness: Associations with Well-Being and Mindfulness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolokotsa, D.; Lilli, A. A.; Lilli, M. A.; Nikolaidis, N. P. On the Impact of Nature-Based Solutions on Citizens’ Health & Well Being. Energy Build. 2020, 229, 110527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repke, M. A.; Berry, M. S.; Conway, L. G.; Metcalf, A.; Hensen, R. M.; Phelan, C. How Does Nature Exposure Make People Healthier?: Evidence for the Role of Impulsivity and Expanded Space Perception. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0202246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations World Tourism Organization. 2020: A year in review. COVID-19 and Tourism. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/covid-19-and-tourism-2020.

- Robina-Ramírez, R.; Leal-Solís, A.; Medina-Merodio, J. A.; Estriegana-Valdehita, R. From Satisfaction to Happiness in the Co-Creation of Value: The Role of Moral Emotions in the Spanish Tourism Sector. Qual. Quant. 2023, 57, 3783–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretyakoba, T.; Savinovskaya, A. Eco Tourism as a Recreational Impact Factor on Human Condition. 2016, 7, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomfret, G. Family Adventure Tourism: Towards Hedonic and Eudaimonic Wellbeing. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, C.; Chen, W.; Ma, Z.; Yan, J.; Sun, L. Transformers in Time Series: A Survey. . arXiv May 11, 2023. 2023. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2202.07125 (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Seervi, D. P. Ecotourism and Sustainable Development. 2023.

- Ke, G.-N.; Utama, I. K. A. P.; Wagner, T.; Sweetman, A. K.; Arshad, A.; Nath, T. K.; Neoh, J. Y.; Muchamad, L. S.; Suroso, D. S. A. Influence of Mangrove Forests on Subjective and Psychological Wellbeing of Coastal Communities: Case Studies in Malaysia and Indonesia. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 898276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, H.; Rezapouraghdam, H.; Esmaeili, B. Public Health and Tourism; A Personalist Approach to Community Well-Being: A Narrative Review. Iran. J. Public Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.; Lovell, R. Evidence Statement on the Links between Natural Environments and Human Health. European Centre for Environment & Human Health, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez Bata, I. N. Efectos de Los Viajes Turísticos En Personas Padecientes Del Trastorno de Depresión En El Estado de México, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México Centro Universitario UAEM Texcoco, México, 2023.

- Septaviani Issera Sulistya Putri, V.; Rahayu Wijayanti, L.; Nur Hidayati, I. The Positive Effect of The Forest Environment in The Ecotherapy Healing Forest Program on The Physical and Mental Health After COVID-19. BIO Web Conf. 2023, 80, 03023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, H.-J.; Park, S. The Effect of Cross-Level Interaction between Community Factors and Social Capital among Individuals on Physical Activity: Considering Gender Difference. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Kim, J.; Song, I.; Yi, Y.; Park, B.-J.; Song, C. The Effects of Forest Walking on Physical and Mental Health Based on Exercise Prescription. Forests 2023, 14, 2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marselle, M. R.; Warber, S. L.; Irvine, K. N. Growing Resilience through Interaction with Nature: Can Group Walks in Nature Buffer the Effects of Stressful Life Events on Mental Health? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarroel, M. A. Symptoms of Depression Among Adults: United States, 2019, 2020, No. 379.

- World Health Organization. Adolescent and young adult health.

- Görgü Akçay, N. S.; Bükün, M. F.; Köse, Ö. KAYGI VE KORKUNUN İŞLEVSEL OLAN VE OLMAYAN TARAFLARINA GENEL BİR BAKIŞ. Bingöl Üniversitesi Sos. Bilim. Enstitüsü Derg. 2022, 12, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macua, T. Epidemiology and Management of Anxiety Disorders. 2021.

- Lisowski, O.; Grajek, M. The Role of Stress and Its Impact on the Formation of Occupational Burnout. J. Educ. Health Sport 2023, 13, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, F.; Santibáñez, P.; Vinet, E. V. Uso de las Escalas de Depresión Ansiedad Estrés (DASS-21) como Instrumento de Tamizaje en Jóvenes con Problemas Clínicos. 2016.

- Gurrola Peña, G. M.; Balcázar Nava, P.; Bonilla Muños, M. P.; Virseda Heras, J. A. Estructura Factorial y Consistencia Interna de La Escala de Depresión Ansiedad y Estrés (DASS-21) En Una Muestra No Clínica. 2006.

- Chauhan, R.; Himanshu, J.; Shaktan, A.; Kumar, A. Employees’ Psychological Well-Being in a Pandemic: A Case Study during the Peak of the COVID-19 Wave in India. 2024, pp 58–75.

- Naaz, A.; Anjum, A.; Gowami, U.; Kala, K. To Measure the Level of Depression Anxiety and Stress Using a Dass-21-Based Questionnaire on the Students of Shri Guru Ram Rai University, India. Indian J. Pharm. Pract. 2024, 14, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I. A.; Azazz, A. M. S. Mental Health of Tourism Employees Post COVID-19 Pandemic: A Test of Antecedents and Moderators. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 626–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujčić, I.; Safiye, T.; Milikić, B.; Popović, E.; Dubljanin, D.; Dubljanin, E.; Dubljanin, J.; Čabarkapa, M. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Epidemic and Mental Health Status in the General Adult Population of Serbia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, D.; Meeteren, V. V.; Neuts, B. Response and Recovery from Covid-19 in Historic Urban Destinations (Cases from Belgium and the Netherlands). Via Tourism Review 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orte, C.; Sánchez-Prieto, L.; Domínguez, D. C.; Barrientos-Báez, A. Evaluation of Distress and Risk Perception Associated with COVID-19 in Vulnerable Groups. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 9207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. M.; Brindley, P.; Cameron, R.; MacCarthy, D.; Jorgensen, A. Environmental Research and Public Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2004, 1, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apóstolo, J.; Bobrowicz-Campos, E.; Rodrigues, M.; Castro, I.; Cardoso, D. The Effectiveness of Non-Pharmacological Interventions in Older Adults with Depressive Disorders: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 58, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, M.; Smit, C. C. H.; De Vos, S.; Benko, R.; Llor, C.; Paget, W. J.; Briant, K.; Pont, L.; Van Dijk, L.; Taxis, K. A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-analysis of Community Pharmacist-led Interventions to Optimise the Use of Antibiotics. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 88, 2617–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S. K.; Webster, R. K.; Smith, L. E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G. J. The Psychological Impact of Quarantine and How to Reduce It: Rapid Review of the Evidence. The Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, R. COVID-19’s Crushing Effects on Medical Practices, Some of Which Might Not Survive. 2020; 324, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talevi, D.; Pacitti, F.; Socci, V.; Renzi, G.; Alessandrini, M. C.; Trebbi, E.; Rossi, R. The COVID-19 Outbreak: Impact on Mental Health and Intervention Strategies. J. Psychopathol. 2020, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santabárbara, J.; Lasheras, I.; Lipnicki, D. M.; Bueno-Notivol, J.; Pérez-Moreno, M.; López-Antón, R.; De La Cámara, C.; Lobo, A.; Gracia-García, P. Prevalence of Anxiety in the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Updated Meta-Analysis of Community-Based Studies. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 109, 110207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P. F.; Lovibond, S. H. The Structure of Negative Emotional States: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Paino, M.; Lemos-Giráldez, S.; Muñiz, J. Propiedades Psicométricas de La Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21) En Umversitarios Españoles. Ansiedad y Estrés 2010, 16, 215–226. [Google Scholar]

- Lacomba-Trejo, L.; Schoeps, K.; Valero-Moreno, S.; Del Rosario, C.; Montoya-Castilla, I. Teachers’ Response to Stress, Anxiety and Depression During COVID -19 Lockdown: What Have We Learned From the Pandemic? J. Sch. Health 2022, 92, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).