1. Introduction

Bruxism is defined as repetitive masticatory muscle activity characterized by clenching or grinding of the teeth and/or by bracing or thrusting of the mandible [

1]. Bruxism is not considered a disorder in healthy individuals, but rather a risk factor for adverse oral health outcomes [

2], particularly when the magnitude and direction of the clenching forces exceeds the adaptive capacity of the stomatognathic system [

3].

Bruxism affects between 8% and 31.4% of the general population [

4] and it is considered to have a multifactorial nature. Etiological factors may include peripheral (e.g., occlusal imbalances), psychosocial (e.g., stress, anxiety), and central nervous system components, including impairments of brain neurotransmitters and dysfunction of the basal ganglia [

5,

6,

7]. Individuals with bruxism often exhibit other accompanying symptoms such as high levels of hostility, increased sensitivity, and frustration [

8,

9]. These emotional responses involve the activation of the amygdala, which influences the mandibular motor nucleus and increases activity of jaw-closing muscles. This cascade generates hormonal stimuli in the mandibular bone, ultimately resulting in increased activity of the sympathetic nervous system [

10,

11].

Heart rate variability (HRV) is a non-invasive and objective electrophysiological measure used to assess the stress level, the autonomic nervous system (ANS) status, and general health. HRV is defined as the analysis of fluctuations in the intervals between heartbeats [

12] and serves as a proxy for the ANS balance through the vagal parasympathetic activity at the cardiac level [

13]. Lower HRV values suggest sympathetic dominance and amygdala hyperactivation and have been associated with a strong negativity bias and impaired regulatory and homeostatic function. On the contrary, a high HRV reflects increased parasympathetic (vagal) activity and reduced fear responses [

12,

14]. Previous evidence suggests that, in individuals with bruxism, HRV assessments often shows a predominance of sympathetic activity [

15], possibly explaining micro-arousals during the night in those with sleep bruxism [

16]. This sympathetic hyperactivity is likely due to parasympathetic inhibition, which may be mediated by afferent inputs from the abdominal viscera to the vagal sensory nucleus [

17,

18].

Several conservative treatment approaches have been proposed for managing bruxism, including occlusal splints [

19], behavioral therapy [

20], pharmacological treatment [

21], and physiotherapy. Among physiotherapeutic approaches, manual therapy (MT) has emerged as a useful non-invasive option [

22]. MT can have beneficial effects on HRV, resulting in a decreased sympathetic nervous system activity, together with pain reduction [

23]. Visceral manual therapy (VMT), a specific form of MT, has proven effective in various conditions, for example, to regulate the lower esophageal sphincter in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease [

24,

25,

26]. To date, there is no evidence about the impact of VMT in patients with bruxism. The present study aims to investigate the immediate and short-term effects of two sessions of VMT on HRV, as well as on the viscoelastic properties and pressure pain sensitivity of the masticatory muscles in adults with bruxism.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

An experimental, parallel, single-blind, randomized controlled trial was conducted. The study adhered to the CONSORT guidelines for reporting clinical trials [

27] and complied with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (Approval Code: 1818-N-22) and was prospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05751694).

2.2. Participants

Using a convenience sampling method, consecutive individuals diagnosed with bruxism by a dentist were recruited from November 2023 to January 2025 at a private medical center in Southern Spain. Eligible participants were between 18 and 65 years and met the criteria for “probable bruxism”, according to the diagnostic guidelines proposed by Lobbezoo et al. [

1]. The diagnosis was based on a positive self-report combined with the presence of one or more clinical signs including: a) visible tooth wear, chipping, or fractures; b) dental impressions on the tongue and/or cheeks; c) masseter muscle hyperthropy; and d) tenderness upon palpation of the masticatory muscles [

2]. Exclusion criteria included: a) recent trauma or fractures in the craniofacial, mandibular, or cervical regions; b) previous temporomandibular joint surgery; c) acute dental pain due to caries or root inflammation; d) ongoing orthodontic treatment; e) history of abdominal surgery, gastric ulcers, gastritis, or current/past gastric neoplasia; f) diagnosed with neurological, rheumatic, or systemic diseases; g) pregnancy or breastfeeding; h) being under chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment; i) cognitive or psychiatric disorders; j) cardiac conditions, including arrhythmias or implanted electronic devices; k) drug or alcohol abuse; l) use of analgesics or drugs affecting the central nervous system; and m) prior experience with VMT directed to the gastric region. All participants received both oral and written information about the study and signed an informed consent form before being enrolled.

2.3. Randomization and Blinding

An external staff member used Microsoft Excel to generate a random number sequence with 1:1 allocation ratio. Group assignment was concealed using opaque, sealed, and consecutively numbered envelopes. The outcome assessor remained blinded to participants allocation group.

2.4. Interventions

A physiotherapist with over 10 years of experience in MT was responsible for the interventions in both study groups. Interventions took place in a private physiotherapy clinic in separate rooms for evaluation and treatment. A treatment table and a bolster were used during sessions. The experimental group underwent a VMT technique derived from the “Ralph Failor Osteopathic Technique” [

28]. Participants were in a supine position with hips, knees, and ankles flexion, with the bolster under the knees to relax the abdominal region. The technique was applied in two stages. In the first stage, the therapist placed both hands over the epigastric area, just below the xiphoid process, and advanced towards the upper border of the stomach’s greater curvature. A skin fold was lifted to reduce superficial tension and direct the contact to the underlying visceral tissue (

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hand placement during the first stage of the visceral manual therapy technique.

Figure 1.

Hand placement during the first stage of the visceral manual therapy technique.

Participants were instructed to breathe deeply. During exhalation, the therapist applied a zigzag motion with vibratory hand movements while exerting a caudal traction on the tissue. The whole procedure lasted approximately 3 minutes. In the second stage, the therapist’s left hand made contact over the epigastric area, with the ulnar edge of the hand placed under the lower border of the left costal margin (

Figure 2). The right hand was used to reinforce this contact. In this position, the participant was again instructed to breathe deeply, and during exhalation the therapist applied a caudal traction to the tissue for approximately 2 minutes.

Figure 2.

Hand placement during the second stage of the visceral manual therapy technique.

Figure 2.

Hand placement during the second stage of the visceral manual therapy technique.

In the control group, participants maintained the same comfortable supine position and received a sham placebo technique. The therapist placed both hands at the lower costal margin (

Figure 3) and instructed the patient to breathe deeply, as in the experimental group. No pressure, tension or traction was applied to the soft tissues [

24,

25,

29]. Both hands remained with same contact for approximately 5 minutes to mimic the VMT intervention. In both groups, participants underwent two treatment sessions with 1-week between them.

Figure 3.

Hand placement during the placebo technique.

Figure 3.

Hand placement during the placebo technique.

2.5. Outcome Measures

An experienced physiotherapist, who remained blinded to the study aims and participants allocation group, was responsible for all assessments. Outcome measures were collected at baseline (T1), immediately after the first treatment session (T2), before the second intervention at week 2 (T3), immediately after the second intervention at week 2 (T4), and at a 4-week follow-up (T5) [

24].

2.5.1. Primary Outcome – HRV

HRV was measured using a Polar H10 chest strap (Polar Electro Oy., Kempele, Finland) [

30,

31] and the Elite HRV smartphone app (Elite HRV Inc., Asheville, NC, USA) [

32,

33]. The patient was in supine with the head on a pillow. After a 5-minute resting period, HRV was recorded for 5 minutes. Data were then transferred and analyzed using the Kubios HRV software (Kubios Oy., Kuopio, Finland) [

34]. Two HRV parameters were extracted: root mean square of the successive differences (HRV-RMSSD) and standard deviation of the normal-to-normal interbeat intervals (HRV-SDNN) [

35]. HRV-RMSSD reflects vagal activity [

36], while HRV-SDNN assesses overall HRV, showing the balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic activity [

37].

2.5.2. Secondary Measures

Pressure pain sensitivity was measured using pressure pain thresholds (PPTs), as the minimum necessary pressure to evoke pain or discomfort. Using a digital algometer (Wagner Force Ten™, model FPX 100 (Wagner Instruments, Riverside, Connecticut, USA), measurements were made at the spinous process of C4, and both masseter and temporalis muscles [

38]. For the evaluation of the masticatory muscles, the patient was placed in a contralateral side-lying position, with the head on a pillow and the lower limb flexed. The masseter muscle point was located 1 cm superior and 2 cm anterior to the mandibular angle, and the temporalis muscle point was located over the anterior fibers of the temporalis muscle, 2 cm above the zygomatic arch, midway between the lateral edge of the eye and the anterior portion of the helix [

39]. For evaluation at C4, participants remained seated, and pressure was applied perpendicular to the spinous process. At all locations, the assessor gradually increased the pressure and instructed the individuals to indicate when the pressure began to feel unpleasant or painful [

24]. Two measurements were taken with a 30-second interval between them, and the average of the two was used for further analysis.

Muscle viscoelastic properties were assessed using the Myoton PRO device (MYOTON AS, Tallinn, Estonia) [

40]. Two parameters were evaluated [

41]: natural oscillation frequency (F), which reflects the muscle tone or state of tension; and dynamic stiffness (S), which indicates the muscle resistance to deformation. With the participant in a contralateral side-lying position, with the head on a pillow and the lower limb in flexion, assessments were made on the masseter muscle, using the same location as for the PPT. Two measurements were taken with a 30-second interval rest, and the average of the two was recorded for analysis.

2.6. Sample Size

The sample size was estimated for a two-group design with five measurements. Parameters included an alpha level of 0.05, a study power of 95%, a correlation of 0.4 between repeated measures, and a medium effect size (η² ≈ 0.12) for differences between groups in the HRV, as assessed with the HRV-SDNN (G*Power software, version 3.1.9.7, University of Kiel, Kiel, Germany). To account for a potential 10% dropout rate, a total of 24 participants were required to complete the study.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical processing was performed using IBM Statistics Package for Social Science®, version 29 (IBM Corp., New York, USA), following an intention-to-treat analysis. The normality of the data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to explore the differences between-groups. A repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine the impact of the intervention in the study measures, using groups (experimental or control) as the between-subjects factor and time: baseline (T1), immediately after the first session (T2), before the second session (T3), immediately after the second session (T4), and at a 4-week follow-up (T5) as the within-subjects factor. The effect size was estimated using partial eta squared (η²). The level of significance was set at a P value < 0.05.

3. Results

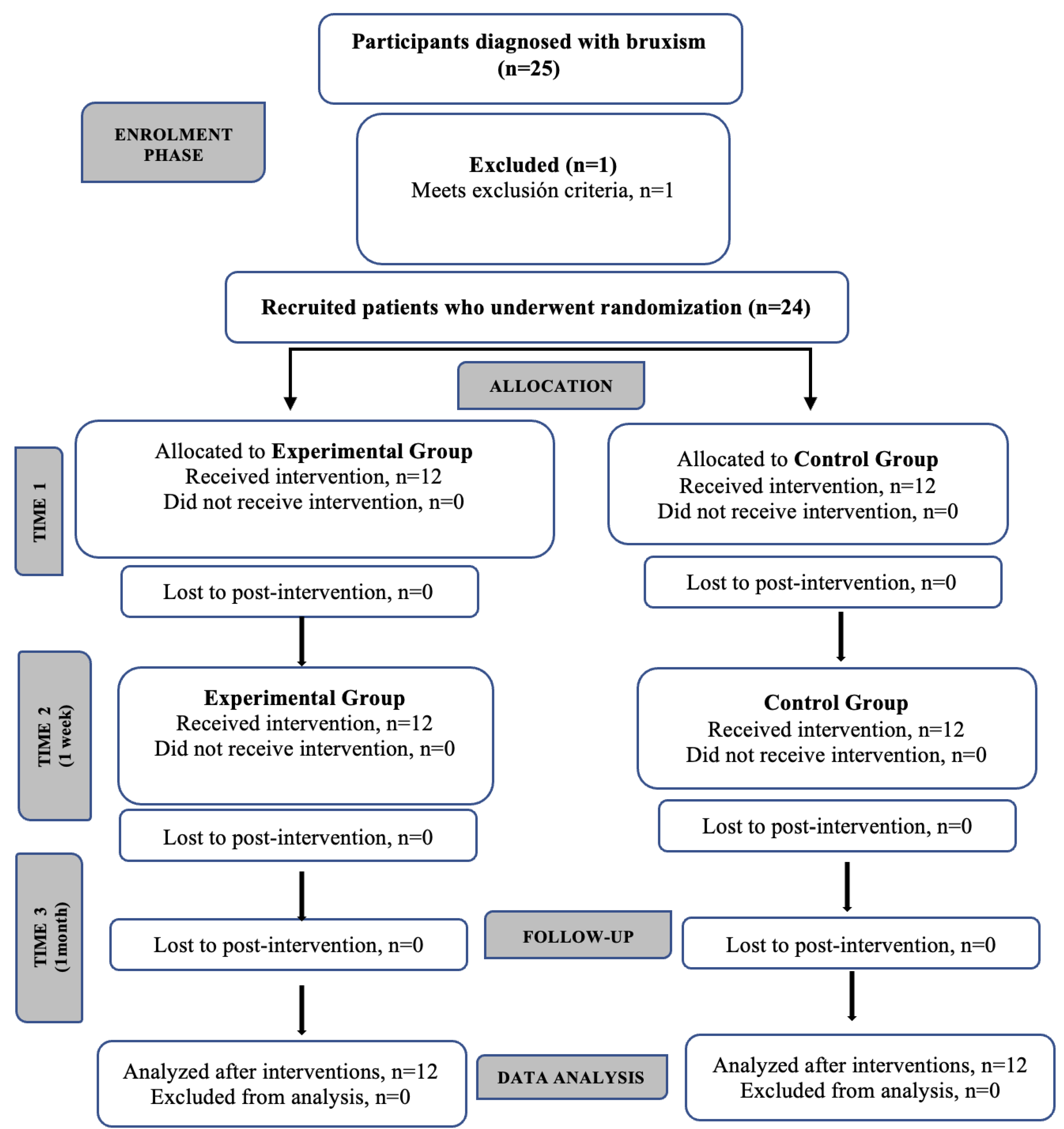

A total of 24 participants (11 females, 45.83%), with a mean age of 38 ± 10.60 years and a clinical diagnosis of probable bruxism participated in the study. No participants were lost to follow-up (

Figure 4). There were no modifications to the intervention protocol and no adverse effects were reported during the course of the study.

Table 1 lists the clinical and demographic characteristics of the sample. At baseline, there were no statistically significant differences between groups for any measure (all, p > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Flow chart diagram of participants.

Figure 4.

Flow chart diagram of participants.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Charactetisticas of Participants in the Study Groups.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Charactetisticas of Participants in the Study Groups.

| |

Experimental Group n=12 |

Control Group n=12 |

| Age, y, mean (SD) [Range] |

38.5 (9.64) [21-55] |

38.5 (11.92) [25-64] |

| Sex, reported as famale, n (%) |

5 (41.66%) |

6 (50%) |

| Heigh, cm, mean (SD) [Range] |

168.25 (8.42) [154-178] |

170.00 (10.89 [156-187] |

| Weight, Kg, mean (SD) [Range] |

75.89 (19.42) [46.30-104.10] |

89.97 (22.27) [55-133] |

| Body mass index, Kg/cm2, mean (SD) [Range] |

26.40 (4.67) [19.52-33.23] |

30.96 (6.55) [22.60-43.96] |

3.1. Primary Outcome – HRV

The ANOVA showed a significant time*group interaction for HRV-SDNN, with a medium effect size (F = 2.90; p = 0.04; η² = 0.12), but not for HRV-RMSSD. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences between groups with a large effect size when comparing T1 to T2 for both HRV-SDNN and HRV-RMSSD. Similarly, significant changes were observed when comparing T3 to T4 (

Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in heart rate variability over time.

Table 2.

Changes in heart rate variability over time.

| |

Within group differences |

Between group differences |

Effect Size |

| |

Experimental Group |

Control Group |

|

|

| HRV - SDNN |

| Baseline (T1) |

39.64 (12.01) |

38.76 (23.26) |

|

|

| Post- first intervention (T2) |

58.25 (24.00) |

38.34 (21.79) |

|

|

| Pre- second intervention (T3) |

41.21 (21.14) |

32.50 (9.97) |

|

|

| Post- second intervention (T4) |

48.21 (14.75) |

32.51(15.49) |

|

|

| 4-week follow-up (T5) |

41.21(21.14) |

32.50 (9.97) |

|

|

| Change T1 to T2 |

-18.61(15.96) |

0.42 (4.23) |

0.001 (-15.43 to -2.76) |

0.42 (0.10-0.62) |

| Change T3 to T4 |

-11.61 (18.16) |

-3.42 (8.58) |

0.172 (-13.64 to -1.39) |

0.08 (0.00-0.32) |

| HRV - RMSSD |

| Baseline (T1) |

36.15 (14.73) |

40.63 (36.37) |

|

|

| Post- first intervention (T2) |

54.41 (25.86) |

40.59 (35.91) |

|

|

| Pre- second intervention (T3) |

33.56 (8.46) |

28.15 (14.60) |

|

|

| Post- second intervention (T4) |

45.93 (16.20) |

31.30 (19.16) |

|

|

| 4-week follow-up (T5) |

39.74 (24.00) |

34.09 (17.65) |

|

|

| Change T1 to T2 |

-18.26 (-29.02 to -7.49) |

0.04 (-2.03 to 2.10) |

0.001 (-15.51 to -2.70) |

0.38 (0.07-0.59) |

| Change T3 to T4 |

-12.37 (-22.46 to -2.29) |

-3.15 (-7.80 to 1.50) |

0.08 (-13.24 to -2.28) |

0.13 (0.00- 0.38) |

3.2. Secondary Measures

No significant time*group interaction was observed for PPT scores or the viscoelastic properties of the masseter muscle (all, p > 0.05) (Supplementary Material 1 and 2). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons only showed a significant increase in the PPT at C4 when comparing T3 and T4 (p = 0.049), with a large effect size (η² = 0.16; 95% CI: 0.00–0.40), and in the left temporalis muscle when comparing T1 and T2 (p = 0.01), with a medium effect size (η² = 0.07; 95% CI: 0.00–0.32).

4. Discussion

The present randomized controlled trial examined the immediate and short-term effects of using VMT to modulate the ANS activity in individuals with bruxism, and whether these effects were accompanied by changes on masticatory muscles viscoelastic properties and pressure pain sensitivity. Our findings demonstrated a significant increase in HRV-SDNN over time in those who underwent VMT compared to the sham placebo, which suggests that VMT may positively modulate sympathovagal balance. On the contrary, VMT was no better than placebo to evoke changes in muscle tone, stiffness, and pressure pain sensitivity of the masticatory muscles.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomized clinical trial to explore the efficacy of VMT in the context of dentistry problems, such as bruxism. Previous evidence has concluded that MT applied to the diaphragm may elicit immediate changes in HRV in patients with respiratory conditions [

42]. Other studies used VMT targeting the epigastric region in individuals with gastroesophageal reflux disease, with beneficial effects to regulate the lower esophageal sphincter tone [

24,

25]. However, no prior research has specifically assessed the impact of VMT on the ANS. Although the present findings are promising and support the role of VMT in modulating autonomic function, these results need to be confirmed in further research before making solid clinical recommendations for individuals with bruxism.

Contrary to what was expected, changes in pressure pain sensitivity were minimal and only achieved statistical significance in post-hoc pairwise comparisons at C4 spinous process and the left temporalis muscle. Mc Cross et al. [

43] concluded that MT applied to the epigastric region may evoke a neuromodulatory response via afferent stimulation of the phrenic nerve, an effect described as “regional interdependent inhibition”. Similarly, it has been hypothesized that VMT may induce a hypoalgesic response through vagal activation and the trigeminovagal connection that converges at the level of the spinal trigeminal nucleus [

44]. Despite these purported theoretical mechanisms, the present results do not fully support this hypothesis and provide only limited rationale for such effects. There are studies that have demonstrated the effectiveness of MT in reducing pressure pain on myofascial trigger points in patients with temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) [

45]. However, studies specifically focused on individuals diagnosed with bruxism are scarce. In line with our findings, Machado et al. [

46], reported no significant changes in PPT scores of the masticatory muscles in a follow-up study in a cohort of adults with bruxism undergoing orthodontic treatment. In contrast, Kadıoğlu et al. (2024) [

47] found that combining MT (including stretching, mobilizations, and ischemic compression) and home exercises over 8 weeks was effective to reduce pain intensity in patients with bruxism. This study also involved activation of the parasympathetic nervous system through stretching of the suboccipital muscles and cervical fascia. The differences between studies in the intervention protocols may explain the discrepancies with our results.

Regarding masseter muscles viscoelastic properties, no significant changes were observed in muscle tone or stiffness. Microtraumas induced by bruxism are among the contributing factors to TMDs [

48]. Although patients with mild TMDs show similar masticatory muscles stiffness than those without dysfunction [

41], individuals diagnosed with a moderate-to-severe TMD exhibit significant deviations across all myotonometry parameters, including increased muscle tone and stiffness of the masseter muscles compared to healthy individuals, with differences ranging from 12.5% to 16.5%, respectively [

49]. In line with this, women with muscular or mixed (muscular and articular) TMD show altered viscoelastic properties of the masticatory muscles when compared to asymptomatic controls [

50]. The discrepancy between these findings and our results may be due to the fact that participants in our clinical trial were referred by dentists with a diagnosis of “probable bruxism,” without confirming the presence of a TMD.

Study Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the present results. First, although the sample size was suitable for the study purpose and estimated power, it remains relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, our eligibility criteria were established for a clinical diagnosis of “probable bruxism”, following previous literature on the topic, rather than a confirmed diagnosis of a TMD. This may have influenced the absence of significant changes in PPT and myotonometry scores. Further, the current lack of standardized diagnostic criteria for bruxism, including defined thresholds for muscle tone and stiffness, and pressure pain sensitivity, poses challenges for both clinical assessment of bruxism and interpretation of outcomes. Further studies should aim consistent and objective diagnostic and classification criteria for bruxism to improve comparability across studies and enhance the validity of clinical research in this field.

5. Conclusions

Our findings suggest that two sessions of VMT may lead to a short-term modulation of the ANS, as reflected by changes in HRV. However, VMT did not demonstrate better effects than placebo on pressure pain sensitivity or the viscoelastic properties of masticatory muscles. Further research involving larger populations, longer follow-up periods, and comprehensive diagnostic criteria is warranted to clarify the clinical relevance and applicability of VMT in the management of bruxism.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Pressure pain threshold scores: mean values over time and comparison of variations between consecutive time points. Table S2: Muscle viscoelastic properties of the masseter muscle (muscle tone, F; and Stiffness, S): mean values over time and comparison between consecutive time points.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: C.N-R; LM.F-S and JA.D-M.; Methodology: C.N-R; LM.F-S; JA.D-M and H.F-C.; Software: LM.F-S and AM.H-R.; Validation: C.N-R; LM.F-S; H.F-C; AM.H-R; JA.D-M and A.R-P.; Formal analysis: LM.F-S and C.N-R.; Investigation: C.N-R and H.F-C; Resources: C.N-R; H.F-C; A.R-P and JA.D-M.; Data curation: LM.F-S.; Writing—original draft preparation: C.N-R and AM.H-R.; Writing—review and editing: C.N-R; AM.H-R; H.F-C; LM.F-S; JA.D-M and A.R-P.; Visualization: H.F-C and C.N-R.; Supervision: LM.F-S and AM.H-R.; Project administration: C.N-R and LM.F-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, received approval by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Universidad de Sevilla (Approval Code: 1818-N-22) and was prospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05751694).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study will be available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANS |

Autonomic nervous system |

| VMT |

Visceral manual therapy |

| HRV |

Heart rate variability |

| HRV-RMSSD |

Root mean square of the successive differences |

| HRV-SDNN |

Standard deviation of the normal-to-normal interbeat intervals |

| PPT |

Pressure pain threshold |

| MT |

Manual therapy |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of variance |

References

- Lobbezoo, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Glaros, A.G.; Kato, T.; Koyano, K.; Lavigne, G.J.; de Leeuw, R.; Manfredini, D.; Svensson, P.; Winocur, E. Bruxism Defined and Graded: An International Consensus. Journal of oral rehabilitation 2013, 40, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Raphael, K.G.; Wetselaar, P.; Glaros, A.G.; Kato, T.; Santiago, V.; Winocur, E.; De Laat, A.; De Leeuw, R.; et al. International Consensus on the Assessment of Bruxism: Report of a Work in Progress. Journal of oral rehabilitation 2018, 45, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De La Hoz-Aizpurua, J.L.; Díaz-Alonso, E.; Latouche-Arbizu, R.; Mesa-Jiménez, J. Sleep Bruxism. Conceptual Review and Update. Medicina oral, patologia oral y cirugia bucal 2011, 16, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Winocur, E.; Guarda-Nardini, L.; Paesani, D.; Lobbezoo, F. Epidemiology of Bruxism in Adults: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of orofacial pain 2013, 27, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.; Pitti, V.; Babu, C.L.S.; Kumar, G.P.S.; Deepthi, B.C. Bruxism: A Literature Review. Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society 2010, 10, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Naeije, M. Bruxism Is Mainly Regulated Centrally, Not Peripherally. Journal of oral rehabilitation 2001, 28, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyano, K.; Tsukiyama, Y.; Ichiki, R.; Kuwata, T. Assessment of Bruxism in the Clinic. Journal of oral rehabilitation 2008, 35, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Landi, N.; Romagnoli, M.; Bosco, M. Psychic and Occlusal Factors in Bruxers. Australian dental journal 2004, 49, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.; Schaefer, R.; Ommerborn, M.A.; Giraki, M.; Goertz, A.; Raab, W.H.M.; Franz, M. Maladaptive Coping Strategies in Patients with Bruxism Compared to Non-Bruxing Controls. International journal of behavioral medicine 2007, 14, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.M.; Singh, P.; Khrimian, L.; Morgan, D.A.; Chowdhury, S.; Arteaga-Solis, E.; Horvath, T.L.; Domingos, A.I.; Marsland, A.L.; Yadav, V.K.; et al. Mediation of the Acute Stress Response by the Skeleton. Cell Metabolism 2019, 30, 890–902e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Z.M.; Tu, T.; Lei, R.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.J. Activation of the Mesencephalic Trigeminal Nucleus Contributes to Masseter Hyperactivity Induced by Chronic Restraint Stress. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2022, 16, 841133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.G.; Cheon, E.J.; Bai, D.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Koo, B.H. Stress and Heart Rate Variability: A Meta-Analysis and Review of the Literature. Psychiatry investigation 2018, 15, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.Y.; Elliott, T.; Knowles, M.; Howard, R. Heart Rate Variability in Relation to Cognition and Behavior in Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ageing research reviews 2022, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thayer, J.F.; Åhs, F.; Fredrikson, M.; Sollers, J.J.; Wager, T.D. A Meta-Analysis of Heart Rate Variability and Neuroimaging Studies: Implications for Heart Rate Variability as a Marker of Stress and Health. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 2012, 36, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marthol, H.; Reich, S.; Jacke, J.; Lechner, K.H.; Wichmann, M.; Hilz, M.J. Enhanced Sympathetic Cardiac Modulation in Bruxism Patients. Clinical autonomic research : official journal of the Clinical Autonomic Research Society 2006, 16, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, N.; Kato, T.; Rompré, P.H.; Okura, K.; Saber, M.; Lanfranchi, P.A.; Montplaisir, J.Y.; Lavigne, G.J. Sleep Bruxism Is Associated to Micro-Arousals and an Increase in Cardiac Sympathetic Activity. Journal of sleep research 2006, 15, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvani, A.; Dampney, R.; Swoap, S.; Macefield, V.G.; Joyner, M.; Billman, G.E. Homeostasis: The Underappreciated and Far Too Often Ignored Central Organizing Principle of Physiology. Frontiers in Physiology 2020, 11, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Silberstein, S.D. Vagus Nerve and Vagus Nerve Stimulation, a Comprehensive Review: Part I. Headache 2016, 56, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albagieh, H.; Alomran, I.; Binakresh, A.; Alhatarisha, N.; Almeteb, M.; Khalaf, Y.; Alqublan, A.; Alqahatany, M. Occlusal Splints-Types and Effectiveness in Temporomandibular Disorder Management. The Saudi dental journal 2023, 35, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minakuchi, H.; Fujisawa, M.; Abe, Y.; Iida, T.; Oki, K.; Okura, K.; Tanabe, N.; Nishiyama, A. Managements of Sleep Bruxism in Adult: A Systematic Review. The Japanese dental science review 2022, 58, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Núñez, T.; Amghar-Maach, S.; Gay-Escoda, C. Efficacy of Botulinum Toxin in the Treatment of Bruxism: Systematic Review. Medicina oral, patologia oral y cirugia bucal 2019, 24, e416–e424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadıoğlu, M.B.; Sezer, M.; Elbasan, B. Effects of Manual Therapy and Home Exercise Treatment on Pain, Stress, Sleep, and Life Quality in Patients with Bruxism: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania) 2024, 60. [CrossRef]

- Harper, B.; Price, P.; Steele, M. The Efficacy of Manual Therapy on HRV in Those with Long-Standing Neck Pain: A Systematic Review. Scandinavian journal of pain 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eguaras, N.; Rodríguez-López, E.S.; Lopez-Dicastillo, O.; Franco-Sierra, M.Á.; Ricard, F.; Oliva-Pascual-Vaca, Á. Effects of Osteopathic Visceral Treatment in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2019, 8, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Hurtado, I.; Arguisuelas, M.D.; Almela-Notari, P.; Cortés, X.; Barrasa-Shaw, A.; Campos-González, J.C.; Lisón, J.F. Effects of Diaphragmatic Myofascial Release on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Preliminary Randomized Controlled Trial. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 7273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R.C.V.; De Sá, C.C.; Pascual-Vaca, Á.O.; De Souza Fontes, L.H.; Herbella Fernandes, F.A.M.; Dib, R.A.; Blanco, C.R.; Queiroz, R.A.; Navarro-Rodriguez, T. Increase of Lower Esophageal Sphincter Pressure after Osteopathic Intervention on the Diaphragm in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux. Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus 2013, 26, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Hopewell, S.; Schulz, K.F.; Montori, V.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Devereaux, P.J.; Elbourne, D.; Egger, M.; Altman, D.G. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidelines for Reporting Parallel Group Randomised Trials. International journal of surgery (London, England) 2012, 10, 28–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricard, F. Tratado de Osteopatía Visceral y Medicina Interna. Sistema Digestivo. Tomo II.; 2nd. ed.; Medos Edición S.L. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marizeiro, D.F.; Florêncio, A.C.L.; Nunes, A.C.L.; Campos, N.G.; Lima, P.O. de P. Immediate Effects of Diaphragmatic Myofascial Release on the Physical and Functional Outcomes in Sedentary Women: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies 2018, 22, 924–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loro, F.L.; Martins, R. ; Janaína, ; Ferreira, B. ; Cintia, ; Pereira De Araujo, L.; Lucio, ; Prade, R.; Cristiano, ; Both, B.; et al. Validation of a Wearable Sensor Prototype for Measuring Heart Rate to Prescribe Physical Activity: Cross-Sectional Exploratory Study. JMIR Biomedical Engineering 2024, 9, e57373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffarczyk, M.; Rogers, B.; Reer, R.; Gronwald, T. Validity of the Polar H10 Sensor for Heart Rate Variability Analysis during Resting State and Incremental Exercise in Recreational Men and Women. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, P.; Shrestha, L.; Mahotra, N.B. Validity of Elite-HRV Smartphone Application for Measuring Heart Rate Variability Compared to Polar V800 Heart Rate Monitor. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council 2022, 19, 809–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himariotis, A.T.; Coffey, K.F.; Noel, S.E.; Cornell, D.J. Validity of a Smartphone Application in Calculating Measures of Heart Rate Variability. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Tarvainen, M.P.; Niskanen, J.P.; Lipponen, J.A.; Ranta-aho, P.O.; Karjalainen, P.A. Kubios HRV--Heart Rate Variability Analysis Software. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 2014, 113, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdillon, N.; Yazdani, S.; Vesin, J.M.; Schmitt, L.; Millet, G.P. RMSSD Is More Sensitive to Artifacts Than Frequency-Domain Parameters: Implication in Athletes’ Monitoring. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine 2022, 21, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborde, S.; Ackermann, S.; Borges, U.; D’Agostini, M.; Giraudier, M.; Iskra, M.; Mosley, E.; Ottaviani, C.; Salvotti, C.; Schmaußer, M.; et al. Leveraging Vagally Mediated Heart Rate Variability as an Actionable, Noninvasive Biomarker for Self-Regulation: Assessment, Intervention, and Evaluation. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2023, 10, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An Overview of Heart Rate Variability Metrics and Norms. Frontiers in public health 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, T.C.; Nagamine, H.M.; De Sousa, L.M.; De Oliveira, A.S.; Grossi, D.B. Intra- and Interrater Agreement of Pressure Pain Threshold for Masticatory Structures in Children Reporting Orofacial Pain Related to Temporomandibular Disorders and Symptom-Free Children. Journal of orofacial pain 2007, 21, 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- La Touche, R.; Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C.; Fernández-Carnero, J.; Escalante, K.; Angulo-Díaz-Parreño, S.; Paris-Alemany, A.; Cleland, J.A. The Effects of Manual Therapy and Exercise Directed at the Cervical Spine on Pain and Pressure Pain Sensitivity in Patients with Myofascial Temporomandibular Disorders. Journal of oral rehabilitation 2009, 36, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, R.K.; Vain, A.; Vanninen, E.; Viir, R.; Jurvelin, J.S. Can Mechanical Myotonometry or Electromyography Be Used for the Prediction of Intramuscular Pressure? Physiological measurement 2005, 26, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posta, D. Della; Paternostro, F.; Costa, N.; Branca, J.J. V.; Guarnieri, G.; Morelli, A.; Pacini, A.; Campi, G. Evaluating Biomechanical and Viscoelastic Properties of Masticatory Muscles in Temporomandibular Disorders: A Patient-Centric Approach Using MyotonPRO Measurements. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, H.M.; Muniz de Souza, H.C.; Viana, R.; Neves, V.R.; Dornelas de Andrade, A. Immediate Effects of Rib Mobilization and Diaphragm Release Techniques on Cardiac Autonomic Control in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Pilot Study. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 2020, 19, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoss, C.A.; Johnston, R.; Edwards, D.J.; Millward, C. Preliminary Evidence of Regional Interdependent Inhibition, Using a ‘Diaphragm Release’ to Specifically Induce an Immediate Hypoalgesic Effect in the Cervical Spine. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 2017, 21, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henssen, D.J.H.A.; Derks, B.; van Doorn, M.; Verhoogt, N.C.; Staats, P.; Vissers, K.; Van Cappellen van Walsum, A.M. Visualizing the Trigeminovagal Complex in the Human Medulla by Combining Ex-Vivo Ultra-High Resolution Structural MRI and Polarized Light Imaging Microscopy. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 11305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez-Vera, A.; Polo-Ferrero, L.; Puente-González, A. S.; Méndez-Sánchez, R.; Blanco-Rueda, J. A. Immediate Effects of the Mandibular Muscle Energy Technique in Adults with Chronic Temporomandibular Disorder. Clinics and Practice 2024, 14(6), 2568–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, N.A.G.; Costa, Y.M.; Quevedo, H.M.; Stuginski-Barbosa, J.; Valle, C.M.; Bonjardim, L.R.; Garib, D.G.; Conti, P.C.R. The Association of Self-Reported Awake Bruxism with Anxiety, Depression, Pain Threshold at Pressure, Pain Vigilance, and Quality of Life in Patients Undergoing Orthodontic Treatment. Journal of applied oral science : revista FOB 2020, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadıoğlu, M. B.; Sezer, M.; Elbasan, B. Effects of Manual Therapy and Home Exercise Treatment on Pain, Stress, Sleep, and Life Quality in Patients with Bruxism: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania), 2024, 60(12), 2007. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Silva, A.; Peña-Durán, C.; Tobar-Reyes, J.; Frugone-Zambra, R. Sleep and Awake Bruxism in Adults and Its Relationship with Temporomandibular Disorders: A Systematic Review from 2003 to 2014. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica 2017, 75, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Chon, S. Assessments of Muscle Thickness and Tonicity of the Masseter and Sternocleidomastoid Muscles and Maximum Mouth Opening in Patients with Temporomandibular Disorder. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 9, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taş, S.; Kaynak, B.A.; Salkin, Y.; Karakoç, Z.B.; Dağ, F. An Investigation of the Changes in Mechanical Properties of the Orofacial and Neck Muscles between Patients with Myogenous and Mixed Temporomandibular Disorders. Cranio : the journal of craniomandibular practice 2024, 42, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).