Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background/Objectives: We aimed to examine the acute effects of deep breathing exercise and transcutaenous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) on autonomic nervous system activation and the characteristics of certain muscle groups and to compare these two methods. Methods: 60 healthy adults between the ages of 18-45 were randomly divided into two groups to receive a single session of taVNS and deep breathing exercises. Acute measurements of pulse, blood pressure, perceived stress scale, autonomic activity and muscle properties were performed before and after the application. Results: A significant decrease was detected in the findings regarding the perceived stress scale, pulse and blood pressure values as a result of a single session application in both groups (p <0.05). In addition, it was determined that the findings regarding autonomic measurement values increased in favor of the parasympathetic nervous system in both groups (p <0.05). In measurements of the structural properties of the muscle, the stiffness values of the muscles examined in both groups decreased (p <0.05), while the findings regarding relaxation increased (p <0.05). As a result of the comparative statistical evaluation between the groups, the increase in parasympathetic activity was found to be greater in the deep breathing group (DB) (p <0.05). In the measurements made with the Myoton®PRO device, a significantly higher decrease in the stiffness value of the erector spinae was detected in the respiratory group (p <0.05). and an increase in the relaxation values was detected in the erector spinae and gastrocnemius muscles (p <0.05). Conclusion: It has been observed that both methods can increase parasympathetic activity and muscle relaxation in healthy people in a single session. However, DB seems slightly superior to taVNS in this respect.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Study Protocol

2.4. Assessment

2.4.1. Vagus Nerve Stimulation

2.4.2. Deep Breathing Exercise

2.5. Outcome Measures

2.5.1. Primary Outcome Measure

Analysis of the Autonomic Nervous System

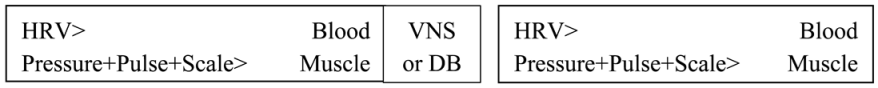

Working Flow Chart

|

Analysis of the Structural Features of the Muscles

2.5.2. Secondary Outcome Measure

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jha, R.K.; Acharya, A.; Nepal, O. Autonomic Influence on Heart Rate for Deep Breathing and Valsalva Maneuver in Healthy Subjects. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc 2018, 56, 670–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmer, A.D.; Albu-Soda, A.; Aziz, Q. Vagus nerve stimulation in clinical practice. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2016, 77, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnon, V.; Dutheil, F.; Vallet, G.T. Benefits from one session of deep and slow breathing on vagal tone and anxiety in young and older adults. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sridhar, B.; Haleagrahara, N.; Bhat, R.; Kulur, A.B.; Avabratha, S.; et al. Increase in the heart rate variability with deep breathing in diabetic patients after 12-month exercise training. TJEM 2010, 220, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.F.; Albusoda, A.; Farmer, A.D.; Aziz, Q. The anatomical basis for transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation. TJOA 2020, 236, 588–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, J.A.; Mary, D.A.; Witte, K.K.; Greenwood, J.P.; Deuchars, S.A.; et al. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation in healthy humans reduces sympathetic nerve activity. Brain Stimul. 2014, 7, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.M.; Xiao, J.; Ren, F.F.; Chen, Z.S.; Li, C.R.; et al. Acute effect of breathing exercises on muscle tension and executive function under psychological stress. Front. Physiol. 2023, 25, 1155134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampusch, S.; Kaniusas, E.; Széles, J.C. Modulation of Muscle Tone and Sympathovagal Balance in Cervical Dystonia Using Percutaneous Stimulation of the Auricular Vagus Nerve. Artif. Organs. 2015, 39, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.K.; Henry, I.C.; Mietus, J.E.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Khalsa, G.; Benson, H.; Goldberger, A.L. Heartrate Dynamics during three forms of meditation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2004, 95, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Fpub 2017, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutlu, N.R. The effect of auricular vagus nerve stimulation on pain and quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Master's Thesis, Bahçeşehir University Institute of Health Sciences, Istanbul, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- He, B.; Lu, Z.; He, W.; Huang, B.; Jiang, H. Autonomic modulation by electrical stimulation of the parasympathetic nervous system: an emerging intervention for cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2016, 34, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billman, G.E. The LF/HF ratio does not accurately measure cardiac sympatho-vagal balance. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, D.; Azizi, B.; Sima, S.; Tavakoli, K.; Hosseini, N.S.; et al. A systematic review of the effects of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on baroreflex sensitivity and heart rate variability in healthy subjects. Clin. Auton. Res. 2023, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferstl, M.; Teckentrup, V.; Lin, W.M.; Kräutlein, F.; Kühnel, A.; et al. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation boosts mood recovery after effort exertion. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 3029–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.E.; Huebschmann, N.A.; Iverson, G.L. Safety and tolerability of an innovative virtual reality-based deep breathing exercise in concussion rehabilitation: A pilot study. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2021, 24, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Couck, M.; Caers, R.; Musch, L.; Fliegauf, J.; Giangreco, A.; et al. How breathing can help you make better decisions: Two studies on the effects of breathing patterns on heart rate variability and decision-making in business cases. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2019, 139, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.K.; Andersen, S.S.; Andersen, S.S.; Liboriussen, C.H.; Kristensen, S.; et al. Modulating Heart Rate Variability through Deep Breathing Exercises and Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation: A Study in Healthy Participants and in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis or Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Sensors 2022, 22, 7884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerath, R.; Edry, J.W.; Barnes, V.A.; Jerath, V. Physiology of long pranayamic breathing: neural respiratory elements may provide a mechanism that explains how slow deep breathing shifts the autonomic nervous system. Med. Hypotheses 2006, 67, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konakoğlu, G.; Özden, A.V.; Solmaz, H.; Bildik, C. The effect of auricular vagus nerve stimulation on electroencephalography and electromyography measurements in healthy persons. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1215757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.H.; Jung, J.H.; Hahm, S.C.; Oh, H.K.; Jung, K.S.; et al. Effects of lumbar lordosis assistive support on craniovertebral angle and mechanical properties of the upper trapezius muscle in subjects with forward head posture. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2018, 30, 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.E. Influential factors of masticatory performance in older adults: A cross-sectional study. IJERPH 2021, 18, 4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roatta, S.; Passatore, M. Autonomic effects on skeletal muscle. In Encyclopedia of neurosci 2009, 250–253. [Google Scholar]

| Gender | VNS | DB | Total | Pearson Chi-Square | p | |||

| n | %İntragroup | n | % İntragroup | n | %İntergroup | 7,500 | 0,006 | |

| Male | 5 | 16,67 | 15 | 50,00 | 20 | 33,33 | ||

| Female | 25 | 83,33 | 15 | 50,00 | 40 | 66,67 | ||

| Total | 30 | 100 | 30 | 100 | 60 | 100 | ||

| N = 60 | DB N = 30 | VNS N = 30 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | Z/t | p | Mean ± SD | Z/t | p | |

| Height (cm) | 171,97 ± 9,34 | -0,074 | 0,941 | 171,70 ± 8,17 | -0,074 | 0,941 |

| Weight (kg) | 66,60 ± 12,54 | -0,429 | 0,668 | 68,40 ± 13,22 | -0,429 | 0,668 |

| Age | 24,70 ± 4,50 | -2,859 | 0,004 | 31,27 ± 8,23 | -2,859 | 0,004 |

| DB | VNS | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | Z/t | p | Mean ± SD | Z/t | p | ||

| Perceived Stress Scale | 1st measurement | 27,20 ± 7,29 | 3,892 | 0,001 ** | 26,10 ± 8,31 | 2,443 | 0,021 ** |

| 2st measurement | 25,97 ± 7,26 | 24,80 ± 7,81 | |||||

| Pulse | 1st measurement | 78,53 ± 9,73 | 4,556 | 0,000 ** | 79,53 ± 9,90 | 6,009 | 0,000 ** |

| 2st measurement | 74,00 ± 9,74 | 73,50 ± 8,11 | |||||

| Systolic Pressure | 1st measurement | 118,23 ± 11,31 | 5,245 | 0,000 ** | 119,73 ± 13,74 | 6,394 | 0,000 ** |

| 2st measurement | 112,33 ± 12,47 | 112,37 ± 13,76 | |||||

| Diastolic Pressure | 1st measurement | 73,40 ± 10,03 | 3,267 | 0,003 ** | 76,00 ± 12,03 | 4,906 | 0,000 ** |

| 2st measurement | 70,13 ± 10,08 | 70,50 ± 13,57 | |||||

| SNS Index | 1st measurement | 0,24 ± 1,01 | 6,041 | 0,000 ** | 0,74 ± 0,95 | 7,75 | 0,000 ** |

| 2st measurement | -0,48 ± 1,16 | 0,02 ± 0,79 | |||||

| PNS Index | 1st measurement | 0,35 ± 1,32 | -4,33 | 0,000 * | -0,46 ± 1,13 | -4,76 | 0,000 * |

| 2st measurement | 9,34 ± 17,59 | 0,55 ± 1,74 | |||||

| RMSSD | 1st measurement | 53,94 ± 30,71 | -4,78 | 0,000 * | 47,03 ± 34,88 | -4,73 | 0,000 * |

| 2st measurement | 232,60 ± 421,98 | 75,83 ± 59,47 | |||||

| Stress Index | 1st measurement | 8,25 ± 3,07 | 8,519 | 0,000 ** | 9,39 ± 3,65 | -4,58 | 0,000 * |

| 2st measurement | 4,79 ± 2,22 | 6,61 ± 2,65 | |||||

| PNN50 | 1st measurement | 21,70 ± 13,31 | -6,23 | 0,000 ** | 13,23 ± 15,54 | -3,96 | 0,000 * |

| 2st measurement | 40,01 ± 21,46 | 20,63 ± 16,84 | |||||

| LF/HF | 1st measurement | 1,37 ± 1,62 | -1,29 | 0,199 | 2,56 ± 2,44 | -0,83 | 0,405 |

| 2st measurement | 1,14 ± 0,62 | 2,60 ± 2,39 | |||||

| Stiffness - Trapezius muscle | 1st measurement | 267,18 ± 33,88 | 5,784 | 0,000 ** | 259,43 ± 44,90 | -4,38 | 0,000 * |

| 2st measurement | 249,70 ± 31,19 | 244,45 ± 43,59 | |||||

| Stiffness - Erector spinae muscle | 1st measurement | 235,53 ± 87,88 | -4,54 | 0,000 * | 192,15 ± 46,10 | -3,67 | 0,000 * |

| 2st measurement | 235,53 ± 87,88 | 185,92 ± 43,91 | |||||

| Stiffness - Gastrocnemius muscle | 1st measurement | 262,80 ± 53,84 | 3,466 | 0,000 ** | 236,68 ± 38,18 | 5,163 | 0,000 ** |

| 2st measurement | 249,10 ± 50,39 | 227,13 ± 39,87 | |||||

| Stiffness - Biceps brachii muscle | 1st measurement | 243,65 ± 36,29 | -4,78 | 0,000 * | 229,68 ± 31,29 | -4,63 | 0,000 * |

| 2st measurement | 230,60 ± 37,59 | 216,18 ± 23,66 | |||||

| Stiffness - Masseter muscle | 1st measurement | 328,25 ± 88,46 | 3,444 | 0,000 ** | 362,68 ± 61,49 | 3,533 | 0,001 ** |

| 2st measurement | 313,47 ± 76,18 | 343,65 ± 57,96 | |||||

| Relaxation- Trapezius muscle | 1st measurement | 18,37 ± 1,94 | -3,97 | 0,000 * | 18,66 ± 1,99 | -4,47 | 0,000 ** |

| 2st measurement | 19,09 ± 1,98 | 19,69 ± 2,02 | |||||

| Relaxation - Erector spinae muscle | 1st measurement | 22,98 ± 5,22 | -4,57 | 0,000 * | 26,53 ± 3,98 | -4,25 | 0,000 * |

| 2st measurement | 24,23 ± 4,42 | 27,05 ± 3,89 | |||||

| Relaxation - Gastrocnemius muscle | 1st measurement | 19,04 ± 4,05 | -2,24 | 0,014 * | 22,46 ± 3,56 | -5,71 | 0,000 ** |

| 2st measurement | 19,57 ± 3,93 | 23,63 ± 3,59 | |||||

| Relaxation - Biceps brachii muscle | 1st measurement | 19,60 ± 1,75 | -4,92 | 0,000 * | 20,84 ± 2,26 | -4,1 | 0,000 * |

| 2st measurement | 20,60 ± 1,36 | 21,72 ± 1,79 | |||||

| Relaxation - Masseter muscle | 1st measurement | 15,84 ± 2,90 | -1,53 | 0,138 | 15,67 ± 2,73 | -4,98 | 0,000 ** |

| 2st measurement | 16,18 ± 2,70 | 16,39 ± 2,70 | |||||

| DB | VNS | |||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Z/t | p | |

| Perceived Stress Scale | -1,23 ± 1,74 | -1,30 ± 2,91 | -0,44 | 0,660 * |

| Pulse | -4,53 ± 5,45 | -6,03 ± 5,49 | -1,771 | 0,077 * |

| Diastolic Pressure | -3,27 ± 5,48 | -5,50 ± 6,14 | -1,305 | 0,143 ** |

| Systolic Pressure | -5,90 ± 6,16 | -7,37 ± 6,31 | -0,096 | 0,923 * |

| RMSSD | 178,67 ± 413,87 | 28,79 ± 36,28 | -2,506 | 0,012 * |

| Stress Index | -3,45 ± 2,22 | -2,77 ± 2,63 | -1,427 | 0,153 |

| PNN50 | 18,31 ± 16,10 | 7,40 ± 9,14 | -2,816 | 0,005 * |

| LF/HF | -0,23 ± 1,60 | 0,04 ± 2,29 | -0,651 | 0,515 |

| SNS Index | -0,73 ± 0,66 | -0,71 ± 0,50 | -1,774 | 0,927 |

| PNS Index | 8,99 ± 17,25 | 1,008 ± 1,08 | -1,368 | 0,014 * |

| Stiffness - Trapezius muscle | -17,48 ± 16,55 | -14,98 ± 17,23 | -0,584 | 0,559 |

| Stiffness - Erector spinae muscle | -26,72 ± 48,77 | -6,23 ± 9,05 | -2,56 | 0,010 * |

| Stiffness - Gastrocnemius muscle | -13,70 ± 21,65 | -9,55 ± 10,13 | -0,88 | 0,379 |

| Stiffness - Biceps brachii muscle | -13,05 ± 9,12 | -13,50 ± 19,42 | -1,435 | 0,151 |

| Stiffness - Masseter muscle | -14,78 ± 23,51 | -19,03 ± 29,51 | -0,925 | 0,355 |

| Relaxation - Trapezius muscle | 0,73 ± 1,00 | 1,03 ± 1,26 | -0,889 | 0,374 |

| Relaxation - Erector spinae muscle | 1,25 ± 1,49 | 0,52 ± 0,58 | -2,62 | 0,009 * |

| Relaxation - Gastrocnemius muscle | 0,53 ± 1,30 | 1,17 ± 1,13 | -2,346 | 0,019 * |

| Relaxation - Biceps brachii muscle | 0,99 ± 1,11 | 0,88 ± 1,11 | -1,287 | 0,198 |

| Relaxation - Masseter muscle | 0,34 ± 1,23 | 0,72 ± 0,79 | -0,473 | 0,636 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).