1. Introduction

Adolescence represents a critical developmental period during which approximately 50% of all mental health disorders emerge before age 14, with 75% manifesting by mid-twenties [

1]. Recent epidemiological data indicate that mental health conditions affect nearly one in five adolescents globally, with rates of depression, anxiety, and behavioral disorders steadily increasing over the past decade [

2]. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated this crisis, with significant increases in adolescent mental health symptoms and suicide rates documented across multiple countries. The consequences of untreated adolescent mental health problems extend well beyond the teenage years, predicting adverse adult outcomes including unemployment, relationship difficulties, poor physical health, and increased mortality risk [

3].

Traditional community-based mental health services face multiple barriers limiting their effectiveness for adolescents, including insufficient capacity, long wait times, geographic inaccessibility, financial constraints, lack of transportation, and the stigma associated with seeking specialized mental health care. Only approximately 20% of adolescents with diagnosable mental health conditions receive adequate treatment, resulting in a substantial treatment gap [

4]. Disparities are particularly pronounced among racial and ethnic minority youth and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, who experience both higher rates of mental health problems and reduced access to services [

5]. School-based interventions have emerged as a promising strategy to address these challenges by providing mental health support within the natural environment where youth spend significant time, reducing barriers related to cost, transportation, and stigma while enabling early identification and intervention [

6,

7].

Despite growing implementation of school-based mental health programming, questions remain regarding their effectiveness and the factors that moderate outcomes. There is a nascent literature that suggests that school-based interventions are effective in promoting adolescent mental health and well-being, including how outcomes vary based on race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, intervention focus, grade level, professional delivery, delivery format, intervention duration, theoretical framework, and country of origin. Understanding these conditions is essential for optimizing potential interventions and ensuring equitable access.

1.1. Overall Effectiveness of School-Based Interventions

Multiple meta-analyses conducted between 2017 and 2025 provide convergent evidence that school-based mental health interventions produce significant, albeit modest, improvements in adolescent mental health outcomes. Sanchez et al. [

8] conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis examining school-based services for elementary-aged children and found an overall small-to-medium effect size of Hedges’ g equals 0.39 in decreasing mental health problems. More recent systematic reviews focusing specifically on adolescent populations have reported similar effect sizes. Zhang et al. [

9] conducted a rigorous meta-analysis of 29 studies involving 22,420 students in grades K through 12, employing stringent inclusion criteria including baseline equivalence and minimal differential attrition, and found that school-based mental health interventions were effective at reducing both depression and anxiety, with an overall effect size of 0.24. Lekamge et al. [

10] examined whole-school interventions for adolescents aged 12 to 16 and synthesized findings from 28 studies, concluding that these comprehensive approaches showed promise for promoting mental health and preventing risk behaviors, though effect sizes varied considerably across studies. Examining interventions delivered specifically by school counselors, Lemberger-Truelove et al. [

11] conducted a meta-analysis of 28 studies published between 2003 and 2022 evaluating school counselor-led social and emotional learning interventions, revealing a small-to-moderate significant mean effect size of Hedges’ g equals 0.308 (95% CI [0.175, 0.441], p < 0.001). Notably, their moderator analyses demonstrated that school counselor-delivered interventions produced larger effects in schools with high racial/ethnic diversity (g = 0.449 for middle school, g = 0.434 for high school, compared to g = 0.083 for elementary), with academic outcomes showing the strongest effects (g = 0.412), and that interventions grounded in either single or multiple counseling theories (g = 0.316 and g = 0.405, respectively) substantially outperformed atheoretical approaches (g = 0.169). Complementing these quantitative findings, Kim et al. [

12] conducted a content analysis of 45 school counselor-led intervention studies with controlled comparisons, revealing that while 62.2% of studies mentioned some theoretical framework, only 37.8% used a single theory and a mere 20% used combinations of theories in intervention design, with fewer than half (42.2%) measuring theory-relevant constructs and only 20% discussing results in relation to theory.

Broadening out, research on school-based resilience interventions provides additional support for the effectiveness of preventive programming. Cai et al. [

13] conducted a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and found that school-based interventions significantly enhanced resilience in children and adolescents compared to control groups, with a standardized mean difference of 0.17. While this effect size is considered small, the population-level impact can be substantial given the broad reach of universal school-based programming. Domain-specific effects vary, with interventions showing differential effectiveness across outcome types. School-based services demonstrate the largest effects for externalizing problems (Hedges’ g equals 0.50), followed by internalizing problems and attention problems [

8].

A consistent finding across meta-analytic reviews is that intervention intensity and targeting significantly moderate effectiveness. Sanchez et al. [

8] found that targeted interventions (Hedges’ g equals 0.76) and selective prevention programs (Hedges’ g equals 0.67) produced substantially larger effects than universal prevention approaches (Hedges’ g equals 0.29). This pattern suggests that interventions delivered to students with identified needs or risk factors are more effective than those provided to all students regardless of symptomatology or risk status. However, the debate between universal and targeted approaches extends beyond simple effectiveness comparisons, as universal interventions offer important advantages including reduced stigma, broader reach, prevention of problem onset, and potential for population-level impact [

14]. The optimal approach may be a tiered system combining universal promotion with targeted intervention for students showing elevated symptoms or risk.

1.2. Variation by Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status

Racial and ethnic disparities in adolescent mental health service access and outcomes is a critical equity concern. Recent national data indicate persistent gaps in mental health care utilization across racial and ethnic groups. Between 2010 and 2017, rates of mental health care use among Black youth decreased from 9% to 8%, while rates for White youth increased from 13% to 15% [

16]. Even after adjusting for mental health need, significant Black-White and Latinx-White disparities persist in access to both school-based and community-based mental health services. Grunin et al. [

15] examined school-based mental health service utilization and found that Asian adolescents were significantly less likely to utilize school-based services compared to White counterparts, even when controlling for depressive symptoms and other relevant factors, suggesting that cultural factors, stigma, or service design elements may create barriers to engagement for some ethnic minority groups.

Socioeconomic status represents one of the most robust predictors of adolescent mental health, with youth from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds two to three times more likely to develop mental health conditions compared to their more affluent peers [

17]. However, research examining which dimensions of SES most strongly predict mental health problems has produced nuanced findings. A comprehensive study examining five aspects of socioeconomic status found that subjective social status showed the most consistent associations with adolescent mental disorders, with odds ratios ranging from 0.7 to 0.8 after controlling for other SES indicators [

17]. This finding suggests that perceived social standing may be a more proximal mechanism linking economic disadvantage to mental health problems, thus a potentially modifiable target for intervention.

School-based mental health interventions hold particular promise for addressing disparities in access to care by eliminating many economic barriers including cost, transportation, and need for health insurance. Research indicates that school-based services are more accessible than community-based services and are perceived as more acceptable by families from lower socioeconomic backgrounds [

18]. Evidence regarding the differential effectiveness of interventions across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups remains limited, as most studies do not adequately report subgroup analyses. Ensuring equitable implementation requires attention to cultural responsiveness, explicit efforts to engage underserved populations, and monitoring of differential uptake and outcomes across student groups.

1.3. Variation by Intervention Type, Delivery, and Duration

School-based mental health interventions encompass diverse therapeutic and prevention approaches, ranging from individual and group counseling to universal classroom-based programming. These interventions draw upon various theoretical frameworks and employ different strategies to promote mental health and address psychological difficulties. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), social and emotional learning (SEL) programs, and mindfulness-based interventions have received substantial research attention and are commonly implemented in educational settings, each offering distinct advantages for addressing adolescent mental health needs.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is a widely used and extensively studied approach to school-based mental health intervention. Multiple meta-analyses have documented CBT’s effectiveness in reducing depression and anxiety symptoms in school-aged youth. Zhang et al. [

9] found that CBT-based interventions produced superior outcomes compared to other therapeutic approaches, with moderator analyses confirming CBT as a significant predictor of better outcomes. The effectiveness of school-based CBT varies somewhat by implementation format, with both brief CBT interventions (5 sessions) and standard CBT interventions (10 sessions) demonstrating efficacy compared to waitlist controls, though brief CBT has not proven non-inferior to standard CBT [

19].

Social and emotional learning programs are a major category of universal school-based mental health promotion, with a focus on self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. Cipriano et al. [

20] conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis of 252 unique universal SEL programs examined in 424 studies involving over 575,000 students from 53 countries and found that SEL programs are associated with significant improvements in emotional, behavioral, safety, and academic achievement outcomes. SEL interventions have demonstrated effectiveness in enhancing students’ social and emotional skills and reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety in the short term, though questions remain about the durability of effects.

Mindfulness-based interventions have gained considerable popularity in school settings over the past decade, including the publication of various meta-analyses resulting in small but significant positive effects on multiple outcomes. Dunning et al. [

21] conducted a meta-analysis of 33 randomized controlled trials and found that mindfulness-based interventions led to significant improvements in measures of mindfulness, executive functions, and attention, with smaller benefits for depression, anxiety and stress, and negative behaviors. Effect sizes were modest, with an overall effect size of 0.19, and some analyses found evidence of publication bias. When restricted to studies with active control groups, some outcomes showed reduced or non-significant effects, highlighting the importance of rigorous comparison conditions.

The question of who should deliver school-based mental health interventions has important implications for feasibility, cost, scalability, and effectiveness. Zhang et al. [

9] found that interventions delivered by clinicians (including school psychologists, social workers, and external mental health professionals) produced significantly better outcomes compared to those delivered by teachers. However, Sanchez et al. [

8] found that mental health services integrated into academic instruction (Hedges’ g equals 0.59) showed stronger outcomes than pull-out services or add-on programs, suggesting that when mental health content is embedded within teachers’ natural roles and functions, outcomes may be enhanced even when delivered by non-specialists.

School-based mental health interventions can be delivered in multiple formats including individual therapy, small group interventions, classroom-based programs, and whole-school approaches. Contemporary best practice emphasizes multitiered systems of support that combine universal, selective, and indicated interventions in an integrated framework [

22]. Research demonstrates that multitiered systems improve outcomes across multiple domains including mental health, behavior, school climate, and academic performance. Intervention dosage matters, with meta-analytic findings suggesting a dose-response relationship. Sanchez et al. [

8] found that services implemented multiple times per week showed particularly strong effects (Hedges’ g equals 0.50) compared to less frequent delivery.

1.4. Cross-Cultural Evidence and Implementation

Most research on school-based mental health interventions originates from high-income English-speaking countries, particularly the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada. Zhang et al. [

9] found that 79% of participants in their meta-analysis were White, highlighting the limited diversity in research samples. Growing evidence demonstrates that school-based mental health interventions can be feasibly implemented and effective in low- and middle-income countries, though adaptations may be necessary. Bradshaw et al. [

23] conducted a systematic review of universal school-based mental health programs in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) and found that these interventions are feasible, acceptable, and can be delivered effectively in culturally and linguistically diverse settings.

The SEHER program in India provides compelling evidence for school-based mental health promotion in LMIC contexts. Shinde et al. [

24] conducted a cluster randomized controlled trial of this multicomponent intervention utilizing trained lay counselors and teachers to deliver school-based mental health support in Bihar, India. The study showed positive outcomes including reduced depressive symptoms, improved school climate, and decreased bullying when delivered by lay counselors. A systematic review of school-based psychological interventions in sub-Saharan Africa found that interventions delivered by non-specialists (teachers, lay providers, community health workers) produced significant symptom reductions [

25]. These findings support task-shifting models that train non-specialists to deliver mental health interventions, addressing the severe shortage of mental health professionals in many LMICs.

Implementation quality critically determines intervention effectiveness regardless of geographic context. A scoping review of factors affecting implementation of school-based mental health services identified multiple implementation barriers across domains including intervention characteristics, individual implementer factors, organizational contexts, external systems, and implementation processes [

26]. Common implementation challenges include inadequate funding and resources, limited time within school schedules, competing priorities, staff turnover, insufficient training and ongoing support, lack of stakeholder buy-in, poor communication and coordination, and absence of systematic monitoring. Implementation science frameworks emphasize the importance of comprehensive training, ongoing coaching and consultation, protected time for implementation, data systems for monitoring, and administrative leadership to support quality implementation [

27].

1.5. The Current Study

Despite growing implementation of school-based mental health programming, critical questions remain regarding their effectiveness and the factors that moderate outcomes across diverse adolescent populations and implementation contexts. The current study synthesizes contemporary empirical evidence to address whether school-based interventions are effective in promoting adolescent mental health and well-being, and to examine potential sources of variation in intervention outcomes. Specifically, this comprehensive literature review investigates nine secondary questions examining whether intervention effectiveness varies based on student demographic characteristics (race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, grade level), intervention design features (theoretical foundation, intervention focus and activities, duration), implementation characteristics (professional delivering the intervention, delivery format), and contextual factors (country of origin). Given persistent disparities in adolescent mental health service access and outcomes, particular attention is devoted to understanding how intervention effects may differ across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups, and whether certain intervention approaches or implementation strategies demonstrate superior effectiveness for historically underserved populations. Additionally, this review examines cross-cultural evidence from both high-income and low- and middle-income countries to determine the generalizability of school-based intervention effects across diverse international contexts and resource environments.

Understanding these moderating factors can provide scholars and practitioners insights into the qualities of interventions that are associated with the strongest effects, which can in turn can guide resource allocation and programmatic decisions in resource-constrained school settings. Second, determining whether outcomes vary across demographic groups can inform efforts to reduce mental health disparities and ensure equitable access to effective support. Third, examining implementation factors such as provider type and delivery format can clarify feasibility considerations and trade-offs between reach and effectiveness. Finally, synthesizing international evidence can illuminate cultural adaptation needs and inform scaling efforts in diverse contexts. By addressing these questions through systematic synthesis of meta-analytic and systematic review evidence from 2015 through 2025, this review aims to provide actionable guidance for practitioners, school administrators, policymakers, and researchers working to optimize school-based mental health promotion and intervention for all adolescents.

Our overarching research question (RQ) was: Are school-based interventions effective in improving students’ academic, social, emotional, behavioral, and mental health development? Our secondary RQs were, if these interventions are effective, does their effectiveness vary across different contexts, including the intervention’s focus (general vs. targeted), grade level (middle, high, both middle and high school), who delivered the intervention (teachers; school mental health professionals; collaborative teams, mindfulness/wellbeing facilitators, and unknown; clinical psychology professionals or trainees), delivery format (individual, small group, classroom, school-wide), duration of intervention (weeks), research design (randomized control trial [RCT] vs. cluster randomized control trial [CRCT]), location of study (within the United States vs. outside the United States), the use of theory in intervention design (no theory, one theory, multiple theories), changes in measured theory-relevant construct (yes, no, unknown), and results discussed in relation to theory (yes vs. no).

2. Materials and Methods

This review was guided by the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. The PRISMA (

https://www.prisma-statement.org/) provides a checklist and flow diagram to enhance transparency and methodological rigor in conducting systematic reviews. We also used the PICOS framework (i.e., Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Study design) to determine eligibility and exclusion criteria for this study.

2.1. Search Strategy

Systematic literature searches were conducted in Eric and PsycInfo to identify the most pertinent studies on school-based mental health interventions. The search focused on articles, reports, and dissertations that were published within the past 10 years. The search was conducted in July 2025. Search terms were developed based on two components, including the focus of intervention and the empirical design. Specifically, the following keywords were used: school-based mental health services (“school-based mental health” OR “school-based” OR “school counselor*” OR “school social worker*” OR “school psychologist*” OR “social and emotional” OR “academics” OR “behavioral”) AND randomized controlled trials (“randomized controlled trials” OR “RCT” OR “controlled” OR “cluster randomized controlled trials”).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria for this study were developed primarily following the PICOS framework. Articles were included if participants were adolescents aged 10 to 19 years or were enrolled in grades 5 through 12, consistent with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition of adolescence. The interventions examined in the studies were required to be school-based and aimed at improving academic, behavioral, or social-emotional outcomes. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or cluster randomized controlled trials (CRCTs) were included. Additionally, the review only included studies published in English and from 2015 onward.

Studies were excluded if they included participants younger than 10 years of age or enrolled in 4th grade or below, and if the data were not disaggregated to isolate outcomes for individuals aged 10 years or older. Interventions such as career or learning programs were excluded if their outcomes were not related to mental health. Qusai-experimental studies, review articles, qualitative studies, case studies, conceptual papers were excluded. Some studies were excluded when they did not provide sufficient data or statistical information to calculate effect sizes.

2.3. Article Selection and Data Collection Process

Initial database searches focused on school-based mental health interventions employing RCT design, and all search results were imported into Covidence (

https://www.covidence.org/), an online platform for managing systematic reviews. After duplicate records were removed automatically, four reviewers conducted the article selection process. Two graduate student reviewers independently screened all articles by titles and abstracts to determine potential eligibility. After resolving the discrepancies identified during the title and abstract screening, two faculty reviewers independently assessed the full-text articles. Any remaining disagreements among reviewers were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached.

Data extraction spreadsheets were developed, including all the aforementioned moderating factors and the statistical information required for data analysis. The data extraction tool was pilot tested by applying it to two included studies. Two graduate student reviewers divided the included articles and completed the initial coding, and two faculty reviewers independently verified the extracted data for accuracy. Any discrepancies or ambiguities were resolved by the second author.

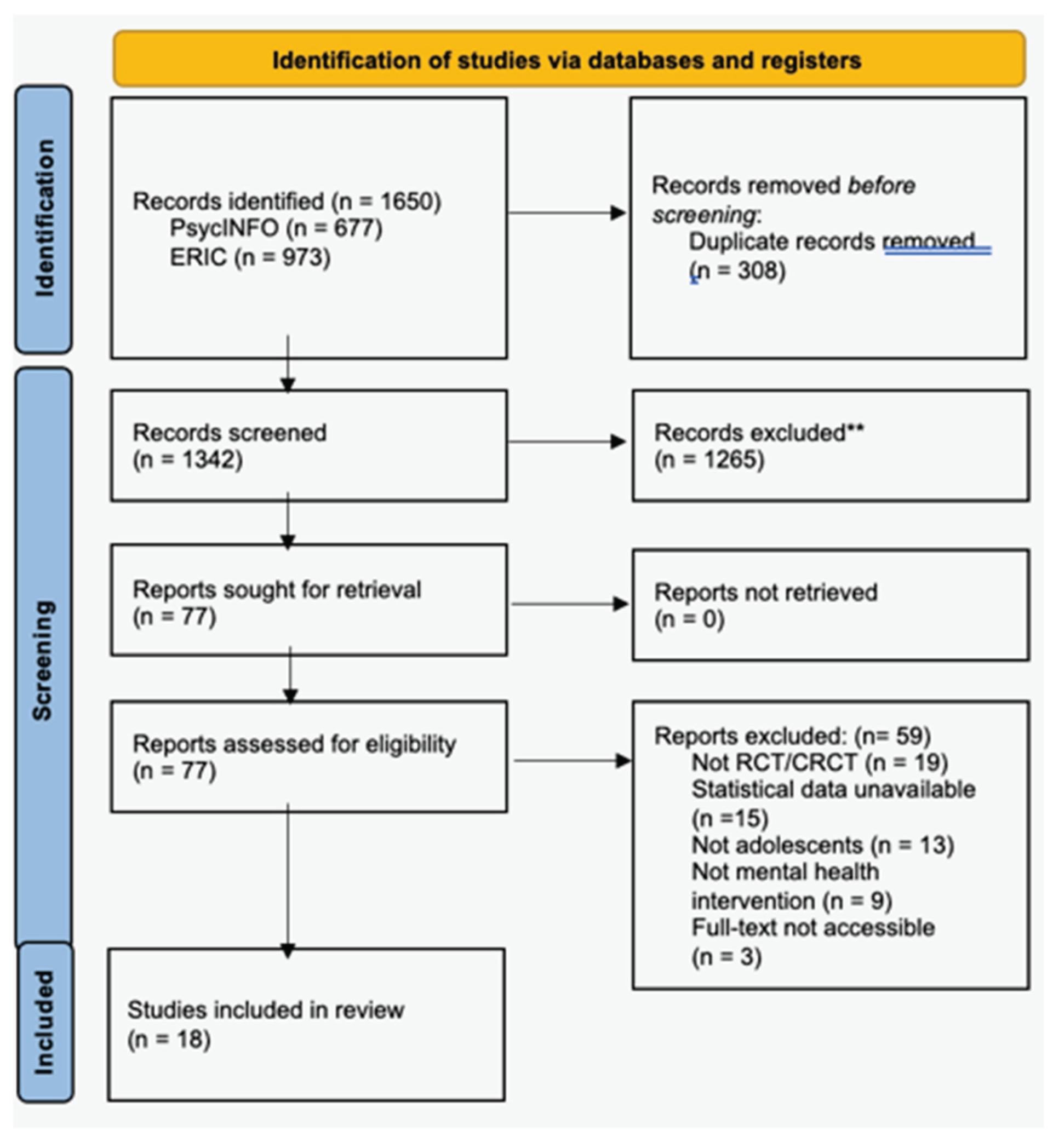

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

2.4. Outcome Measures

Outcome measures directly assessed the dependent variable such as students’ academic, social, emotional, behavioral, and mental health development. These measures included observer-report assessments provided by teachers and parents, as well as self-report surveys and standardized test scores completed by students. In cases where studies used multiple measures or reported various subscales from the same instrument, these were combined to create a comprehensive indicator of students’ overall development.

2.5. Data Analysis

To reduce heterogeneity arising from design differences, we included only RCTs (randomized at the individual level) and CRCTs (randomized at the cluster or group level). Specifically, we included studies that employed a between-group design with both control and treatment groups, in which pre- and post-treatment scores were reported. Because information regarding pre–post correlations was not consistently reported, we assumed a value of 0.5 across all included studies. Additionally, due to inconsistencies in the inclusion or reporting of follow-up data and variations in follow-up intervals across studies, we used only the available immediate post-treatment scores for consistency.

This analysis synthesizes results from 18 independent studies to evaluate the standardized difference in means, using Hedges’s

g as the effect size index to reduce the bias found in small sample size [

28]. We used the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 4 [

29] for all the computations. To accommodate the variety of the studies and their varying contexts, a random-effects model was employed, aligning with the assumption that the studies reflect a random sample from a broader universe of potential research (30, 29, 31].

2.6. Publication Bias and Selective Reporting

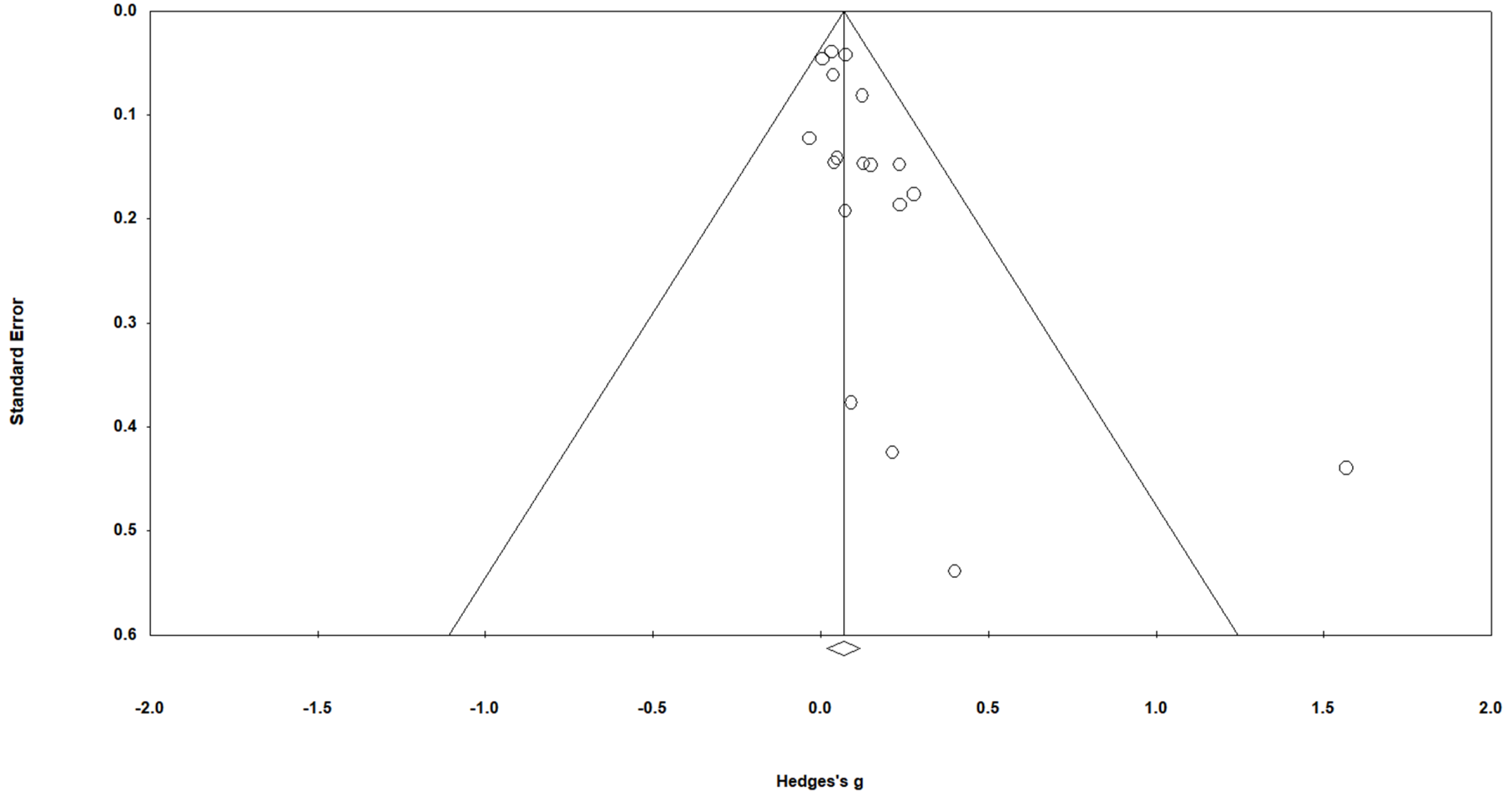

Visual inspection of the funnel plot of standard error by Hedges’s

g suggested a generally symmetrical distribution of effect sizes around the mean, indicating little evidence of publication bias (see

Figure 2). Most studies clustered near the top of the plot, reflecting higher-precision estimates, with no marked asymmetry among smaller studies. Consistent with this observation, the classic fail-safe N analysis indicated that 57 additional studies with null results would be required to increase the overall

p-value to above the 0.05 level, suggesting that the overall effect is robust to potential unpublished findings. Taken together, these results provide no substantial evidence of publication bias in the current meta-analysis.

3. Results

The database search yielded a total of 1,650 records. After duplicates were removed, 1,342 titles and abstracts were screened. Seventy-seven studies whose eligibility could not be determined from the title or abstract were advanced to full-text review. During the full-text screening, 59 studies were excluded for the following reasons: not a randomized or cluster randomized controlled trial (n=19), statistical data unavailable (n=15), population not consisting of adolescents (n=13) not a mental health intervention (n=9), and full-text not accessible (n=3). A total of 18 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final review (

Figure 2).

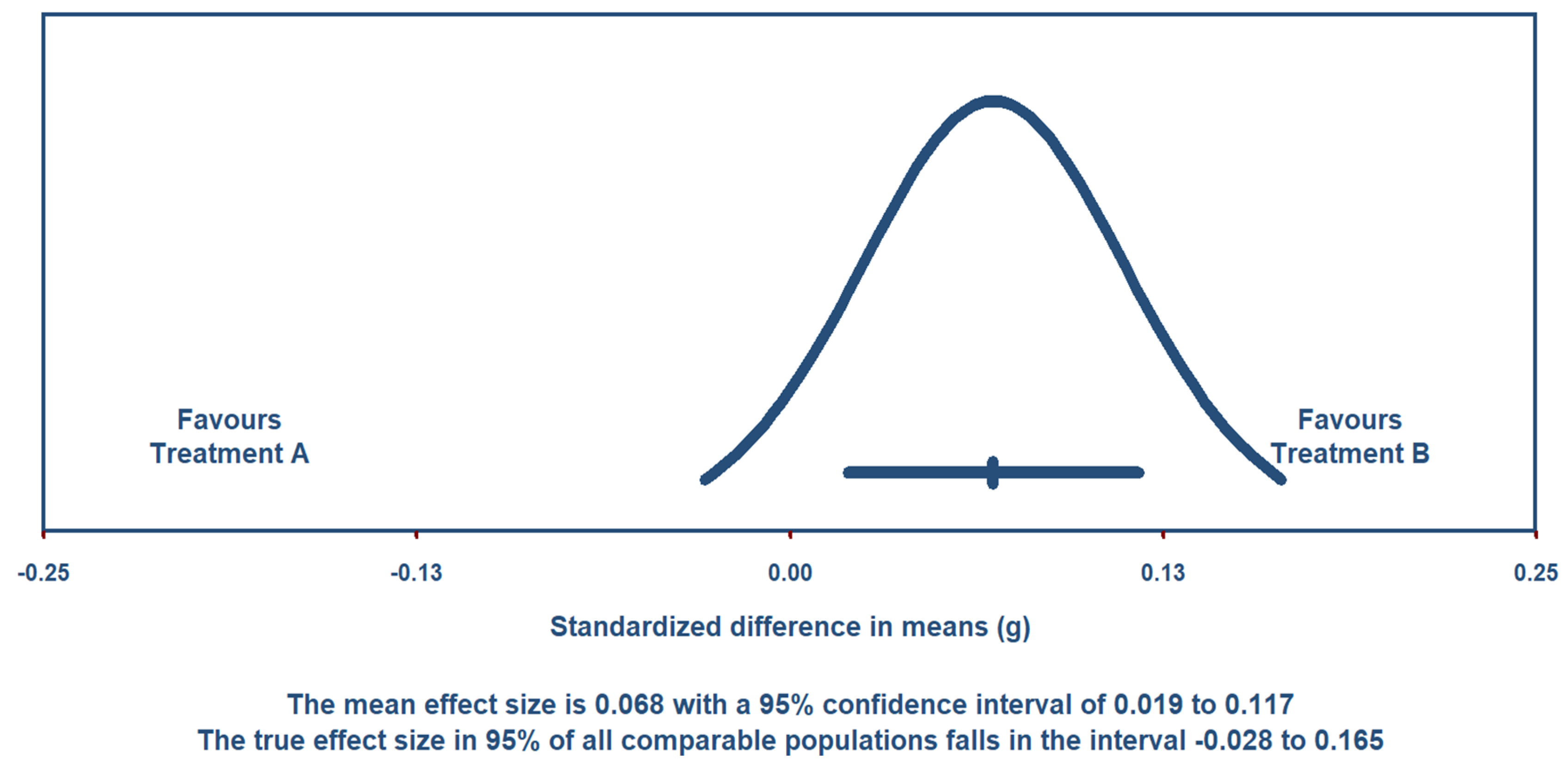

To answer the overarching RQ, the mean effect size across the studies is 0.068, 95% CI [0.019, 0.117]. The true average effect across similar studies could be anywhere within this range. The Z-value tests the null hypothesis that the mean effect size is zero. The

Z-value is 2.738 with

p = 0.006. Using a criterion alpha of 0.050, we reject the null hypothesis and conclude that in the universe of populations comparable to those in the analysis, the mean effect size is not precisely zero. See

Figure 3 for the distribution of true effects and

Figure 4 for the effect sizes of individual studies.

A test of heterogeneity indicated that the effect sizes were not significantly different across studies, Q (df = 17) = 20.005, p = 0.274. The proportion of variance due to true differences rather than sampling error was low (I2 = 15%). The estimated between-study variance was small (τ2 = 0.001), and the corresponding standard deviation of true effect sizes was τ = 0.038, both expressed in g units, indicating minimal variability across studies. Together, these results indicate minimal heterogeneity and a high degree of consistency in effect sizes across studies.

To address a series of secondary RQs, we conducted multiple meta-regressions, which did not reveal any significant moderator effects. This indicates that the effect sizes did not differ significantly across the examined moderators. Nonetheless, the observed differences in effect size magnitudes among subgroups still carry interpretive implications, although these differences are limited to the sample and cannot be generalized to the broader population.

Interventions with a targeted focus (n = 8) demonstrated a higher mean effect size (g = 0.148, p = 0.036, 95% CI [0.010, 0.286]) compared to those with a general focus (n = 10; g = 0.056, p = 0.029, 95% CI [0.006, 0.106]).

Across school levels, interventions implemented in middle schools (n = 10) produced the smallest mean effect size of g = 0.055 (p = 0.060, 95% CI [-0.002, 0.113]). High school interventions (n = 5) demonstrated a higher mean effect size of g = 0.109 (p = 0.108, 95% CI [-0.024, 0.243]). Interventions spanning both middle and high school levels (n = 3) showed the largest effect size, g = 0.134 (p = 0.131, 95% CI [-0.040, 0.307]).

Across four groups based on who delivered the intervention, interventions delivered by teachers (n = 7) produced a small, nonsignificant mean effect size of g = 0.041 (p = 0.224, 95% CI [–0.025, 0.106]). Interventions delivered by school mental health professionals (n = 2) yielded the highest mean effect size, g = 0.157 (p = .254, 95% CI [–0.113, 0.428]), though this effect was not statistically significant. Those implemented by clinical psychology professionals or trainees (n = 6) showed a mean effect size of g = 0.114 (p = 0.122, 95% CI [–0.031, 0.258]), also nonsignificant. Finally, interventions delivered by other facilitators (combined, unknown, mindfulness/wellbeing facilitators; n = 3) had a statistically significant effect, which was the third largest among the groups, g = 0.122 (p = .038, 95% CI [0.007, 0.236]).

Across the five intervention delivery formats, individual interventions (n = 3) showed a negligible and nonsignificant mean effect size of g = –0.002 (p = .984, 95% CI [–0.226, 0.222]). Small-group interventions (n = 4) produced a small but nonsignificant mean effect size of g = 0.138 (p = 0.068, 95% CI [–0.010, 0.286]). Classroom interventions (n = 8) yielded a small but statistically significant mean effect size of g = 0.059 (p = 0.018, 95% CI [0.010, 0.108]). School-wide interventions (n = 1) demonstrated a negligible and nonsignificant effect size of g = 0.033 (p = 0.404, 95% CI [–0.045, 0.111]). Finally, combined individual and small-group interventions (n = 2) showed the largest and statistically significant effect size of g = 0.867 (p = 0.005, 95% CI [0.269, 1.466]).

A meta-regression showed a nonsignificant negative association between intervention duration (measured in weeks) and effect size (β = –0.0027, p = 0.0693), indicating that longer interventions tended to have slightly smaller effects. The intercept was significant (β = 0.1184, p = .003), which suggests that there’s a significant overall positive effect of interventions on average, regardless of duration.

Between the two intervention designs, those that adopted a CRCT design (n = 10) demonstrated a significant mean effect size of g = 0.056 (p = 0.029, 95% CI [0.006, 0.106]). In contrast, those that used an RCT design (n = 8) showed a larger mean effect size of g = 0.148 (p = 0.036, 95% CI [0.010, 0.286]).

When comparing intervention effectiveness between studies conducted in different regions, interventions conducted in the United States (n = 8) showed a statistically significant mean effect size of g = 0.160 (p = 0.016, 95% CI [0.029, 0.290]). In contrast, interventions conducted outside the United States (n = 10) demonstrated a smaller, though still statistically significant, mean effect size of g = 0.052 (p = .034, 95% CI [0.004, 0.099]).

We also compared a series of theory-related interventions. Specifically, we examined intervention effectiveness based on whether and how theories were incorporated into the design. Interventions that did not employ any theory (n = 3) showed a small nonsignificant mean effect size of g = 0.117 (p = .065, 95% CI [–0.007, 0.241]). Those that used a single theory (n = 9) demonstrated a smaller, nonsignificant mean effect size of g = 0.068 (p = 0.081, 95% CI [–0.008, 0.145]). Interventions that integrated multiple theories (n = 6) also produced a small, nonsignificant mean effect size of g = 0.056 (p = 0.323, 95% CI [-0.055, 0.166]).

Then, we examined interventions based on whether there were changes in a measured theory-relevant construct. Interventions that did not have changes in a theory-relevant construct (n = 7) showed a small but statistically significant mean effect size of g = 0.125 (p = 0.018, 95% CI [0.022, 0.229]). Interventions that explicitly reported measured changes in a theory-relevant construct (n = 9) yielded a small but nonsignificant mean effect size of g = 0.054 (p = 0.234, 95% CI [-0.035, 0.142]). Those with unknown measurement status (n = 2) demonstrated a small, nonsignificant mean effect size of g = 0.053 (p = 0.246, 95% CI [-0.037, 0.143]).

Finally, we assessed whether discussing results in relation to theory was associated with differences in intervention effectiveness. Interventions that did not discuss results in relation to theory (n = 10) showed a small but statistically significant mean effect size of g = 0.069 (p = 0.037, 95% CI [0.004, 0.134]). In contrast, interventions that explicitly discussed results in relation to theory (n = 8) demonstrated a small and nonsignificant mean effect size of g = 0.078 (p = 0.098, 95% CI [–0.014, 0.170]).

4. Discussion

The current meta-analysis synthesized evidence from 18 rigorous randomized controlled trials to examine the effectiveness of school-based mental health interventions for adolescents and to investigate potential moderators of intervention outcomes. The findings provide qualified support for the effectiveness of school-based mental health programming while simultaneously revealing important nuances regarding effect size magnitude, heterogeneity, and the influence of implementation factors. This discussion situates the present findings within the broader empirical literature, examines unexpected patterns in the moderator analyses, explores theoretical and methodological implications, and considers practical applications for educational and mental health professionals working to optimize adolescent mental health support in school contexts.

4.1. Overall Effectiveness: Small but Meaningful Effects

The analysis yielded a statistically significant overall effect size of Hedges’

g = 0.068 (95% CI [0.019, 0.117],

p = 0.006), indicating that school-based mental health interventions produce small but reliable improvements in adolescent academic, social, emotional, behavioral, and mental health outcomes. This effect size magnitude aligns with recent meta-analytic findings in the school-based intervention literature. Zhang et al. [

9] reported an overall effect size of 0.24 for school-based mental health interventions targeting depression and anxiety in rigorous randomized controlled trials, while Cai et al. [

13] found a standardized mean difference of 0.17 for school-based resilience interventions. The present finding of

g= 0.068 falls on the lower end of this range, though such variation is expected given differences in outcome measurement specificity, intervention types included, sample characteristics, and methodological inclusion criteria across meta-analyses.

The modest effect size observed in this analysis warrants careful interpretation within the context of public health intervention research. While effect sizes in the range of 0.06 to 0.10 are conventionally categorized as “small” using Cohen’s benchmarks, such characterizations can be misleading when evaluating population-level preventive interventions implemented at scale. As Cipriano et al. [

20] emphasized in their comprehensive meta-analysis of universal social and emotional learning (SEL) programs, even small effect sizes can translate into substantial public health impact when interventions reach large numbers of students. A standardized mean difference of 0.068 suggests a meaningful shift in population-level mental health functioning, particularly when considering that school-based interventions typically reach students who would otherwise not access mental health services. Given that only approximately 20% of adolescents with diagnosable mental health conditions receive adequate treatment (Whitney & Peterson, 2019), school-based interventions serve a critical gap-filling function by providing accessible support to underserved populations. From this perspective, the present findings support continued investment in school-based mental health programming as a component of comprehensive adolescent mental health promotion and intervention systems.

The low heterogeneity observed across studies (

I2 = 15%,

τ2 = 0.001,

Q (

df = 17) = 20.005,

p = 0.274) is a particularly noteworthy finding that merits attention. This result indicates remarkable consistency in effect sizes across the 18 included studies, suggesting that school-based mental health interventions produce relatively uniform effects despite variations in intervention type, implementation context, student populations, and outcome measurement approaches. This pattern contrasts with several previous meta-analyses that reported substantial heterogeneity in school-based intervention effects. For example, Lekamge et al. [

10] noted considerable variation in effect sizes across the 28 whole-school interventions they examined, while meta-analyses of mindfulness-based interventions [

21] and SEL programs have similarly documented meaningful between-study heterogeneity. The low heterogeneity in the current analysis may reflect the stringent inclusion criteria employed, which limited the sample to studies using rigorous randomized controlled trial designs with both pre- and post-treatment assessments and between-group comparisons. By restricting the analysis to methodologically similar studies, we may have reduced extraneous sources of variation that would otherwise contribute to heterogeneity. This methodological homogeneity is both a strength, insofar as it ensures comparability and reduces bias, and a limitation, as it potentially restricts the generalizability of findings to the full range of school-based intervention research, including quasi-experimental designs and studies conducted under more pragmatic real-world conditions.

4.2. Moderator Analyses: Patterns Amidst Statistical Non-Significance

Although meta-regression analyses did not reveal statistically significant moderator effects, the observed patterns in effect size magnitudes across subgroups warrant careful consideration and discussion. The absence of significant moderation should not be interpreted as evidence that these factors are unimportant; rather, the limited statistical power inherent in moderator analyses with 18 studies likely precluded detection of meaningful differences. As Borenstein et al. (2010) noted, moderator analyses require substantially larger samples than primary effect size estimation to achieve adequate statistical power, and the patterns observed in the present analysis deserve interpretive attention even in the absence of statistical significance. These patterns provide preliminary evidence regarding factors that may influence intervention effectiveness and can inform hypothesis generation for future research with larger samples capable of detecting moderation effects.

4.3. Intervention Focus: Universal versus Targeted Approaches

One of the most pronounced patterns in the present analysis concerned intervention focus, with targeted interventions (

g = 0.148,

p = 0.036) producing effect sizes nearly three times larger than general or universal interventions (

g = 0.056,

p = 0.029). This pattern strongly aligns with previous meta-analytic findings demonstrating superior effectiveness of targeted and selective prevention programs compared to universal approaches. Sanchez et al. [

8] reported substantially larger effects for targeted interventions (

g = 0.76) and selective prevention programs (

g = 0.67) compared to universal prevention (

g = 0.29) in their meta-analysis of school-based services for elementary-aged children. The consistency of this pattern across multiple meta-analyses suggests a robust phenomenon whereby interventions delivered to students with identified needs, risk factors, or elevated symptomatology systematically outperform those provided universally to all students regardless of baseline functioning.

Several mechanisms may account for this differential effectiveness. First, targeted interventions likely demonstrate larger effects simply due to greater room for improvement because students with elevated baseline symptoms have more opportunity for measurable change compared to asymptomatic students who are already functioning well. This “floor effect” phenomenon represents a measurement and statistical issue rather than a true difference in intervention potency. Second, targeted interventions may be more precisely calibrated to address specific symptom profiles and risk factors, whereas universal programs must be designed to be broadly applicable, potentially diluting their impact for any particular subgroup. Third, students receiving targeted interventions may demonstrate higher motivation and engagement, as they recognize personal relevance and potential benefit, whereas students in universal programs may lack such intrinsic motivation if they do not perceive themselves as needing support.

However, the debate between universal and targeted approaches extends beyond simple effectiveness comparisons to encompass important equity and implementation considerations. As McCrone [

14] articulated in a health economic analysis, universal interventions offer critical advantages including reduced stigma, broader reach, prevention of problem onset before symptoms emerge, and potential for population-level impact. Universal programming ensures that all students receive mental health promotion, not only those who exhibit visible difficulties or whose problems are recognized by adults. Given persistent disparities in mental health service access—with Black youth, Latinx youth, Asian youth, and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds systematically underutilizing services even when experiencing significant symptoms [

15,

16] —universal approaches may reduce disparities by ensuring that support reaches students whose needs might otherwise go unrecognized. The optimal approach likely involves multitiered systems of support that strategically combine universal promotion with selective and indicated interventions, as advocated by implementation science frameworks [

22]. Such systems capitalize on the efficiency of targeted approaches while retaining the equity advantages of universal programming.

4.4. Grade Level: Developmental Considerations

Effect sizes varied across grade levels, with interventions implemented in middle school settings producing the smallest effects (g = 0.055, p = 0.060), high school interventions yielding larger effects (g = 0.109, p = 0.108), and interventions spanning both middle and high school demonstrating the largest effect sizes (g = 0.134, p = 0.131). While none of these effects achieved conventional statistical significance at the p < 0.05 level, the trend toward larger effects for older adolescents and combined grade spans merits consideration. This pattern could reflect several developmental and methodological factors. Older adolescents may possess greater cognitive maturity, metacognitive awareness, and abstract reasoning capacities that enable them to engage more effectively with intervention content, particularly cognitive-behavioral and skill-based approaches that require self-reflection and application of learned strategies. Additionally, older adolescents may demonstrate higher intrinsic motivation to address mental health concerns as they approach the transition to adulthood and confront increasingly complex psychosocial demands.

Alternatively, the larger effects for combined middle-high school interventions may reflect program design features rather than developmental factors per se. Interventions spanning multiple grade levels likely receive more sustained institutional support, may be embedded within comprehensive school-wide initiatives, and could benefit from continuity and reinforcement across developmental transitions. However, these interpretations remain speculative given the small sample size within subgroups and the non-significant statistical tests. The pattern nevertheless suggests that developmental stage is an important consideration in intervention design and implementation, warranting further investigation with adequately powered samples.

4.5. Professional Delivery: The Role of Training and Expertise

The analysis examined intervention effectiveness across four categories of intervention providers: teachers (

g = 0.041,

p = 0.224), school mental health professionals (

g = 0.157,

p = 0.254), clinical psychology professionals or trainees (

g = 0.114,

p = 0.122), and other facilitators including collaborative teams and mindfulness specialists (

g = 0.122,

p = 0.038). While only the “other facilitators” category achieved statistical significance, the rank ordering of effect sizes reveals a clear pattern, with school mental health professionals producing the largest effects, followed by other specialized facilitators and clinical professionals, with teacher-delivered interventions yielding the smallest effects. This pattern resonates with previous meta-analytic findings. Zhang et al. [

9] reported that interventions delivered by clinicians—including school psychologists, social workers, and external mental health professionals—produced significantly better outcomes compared to those delivered by teachers.

The superior performance of interventions delivered by mental health professionals likely reflects multiple factors including specialized training in psychopathology and intervention techniques, clinical expertise in responding to diverse student needs and crises, and potentially higher implementation fidelity given professional background in the intervention modality. However, this interpretation must be balanced against important countervailing evidence regarding teacher-delivered interventions. Sanchez et al. [

8] found that mental health services integrated into academic instruction (

g = 0.59) demonstrated stronger outcomes than pull-out services or add-on programs, suggesting that when mental health content is embedded within teachers’ natural roles and seamlessly integrated into daily routines, outcomes may be enhanced even when delivered by non-specialists. Furthermore, Lemberger-Truelove et al. [

11] found that school counselor-delivered interventions produced effect sizes of

g = 0.308, substantially larger than the overall average, with even larger effects (

g = 0.449 for middle school,

g = 0.434 for high school) in schools with high racial and ethnic diversity.

These findings underscore critical implementation trade-offs between effectiveness and reach. While interventions delivered by specialized mental health professionals may produce larger effects per student served, such approaches face significant scalability constraints given severe shortages of school-based mental health personnel. Teacher-delivered universal interventions, despite producing smaller per-student effects, can reach entire student populations and may generate meaningful population-level impact through broad implementation. Task-shifting models that train non-specialists to deliver structured interventions is a potentially pragmatic approach to balancing effectiveness and reach, as demonstrated by successful implementations in low- and middle-income countries [

24,

25]. Optimal systems likely require differentiation, with universal promotion delivered by teachers, selective interventions delivered by school counselors, and intensive indicated interventions provided by specialized mental health professionals.

4.6. Delivery Format: Individual, Group, and Classroom Modalities

Intervention delivery format emerged as one of the most intriguing moderators, with combined individual and small-group interventions producing dramatically larger effects (g = 0.867, p = 0.005) compared to other formats. Small-group interventions yielded moderate effects (g = 0.138, p = 0.068), classroom interventions produced small but significant effects (g = 0.059, p = 0.018), school-wide interventions demonstrated minimal effects (g = 0.033, p = 0.404), and individual interventions showed negligible effects (g = -0.002, p = 0.984). The extraordinarily large effect size for combined individual and small-group interventions requires cautious interpretation, as this category included only two studies, making the estimate unstable and potentially influenced by outliers or unique study characteristics. Nevertheless, the broader pattern across delivery formats suggests that small-group interventions may prove to be an optimal balance between individualization and peer learning opportunities, efficiency and personal attention, and scalability and effectiveness.

Small-group formats offer several theoretical and practical advantages. Group settings enable peer modeling and observational learning, normalize mental health challenges through recognition of shared experiences, provide opportunities for interpersonal skill practice in a supportive context, and facilitate development of social support networks among participants. These processes may be particularly important for adolescents, for whom peer relationships are a central developmental focus and primary source of SEL. The modest effects observed for individual interventions in this analysis are somewhat surprising given that individual therapy typically produces larger effects than group therapy in clinical outcome research. However, the school-based context differs meaningfully from clinical settings; individual pull-out interventions may be more stigmatizing in schools, may create logistical complications and academic disruption, and may lack the peer learning opportunities that adolescents value.

The small but significant effects for classroom interventions (

g = 0.059) support universal prevention programming while acknowledging the effectiveness-reach trade-off inherent in these approaches. Classroom interventions maximize accessibility and reduce stigma but necessarily sacrifice individualization and may inadequately address the needs of students with more severe symptoms or complex presentations. The negligible effects for school-wide interventions must be interpreted with caution given that this category included only a single study; this finding should not be construed as evidence against whole-school approaches, which have demonstrated effectiveness in other meta-analyses [

10]. Rather, additional research is needed to understand which whole-school intervention components, implementation strategies, and outcome domains are most amenable to producing measurable effects.

4.7. Intervention Duration: Dosage and Diminishing Returns

The meta-regression examining intervention duration revealed a non-significant negative association between intervention length (measured in weeks) and effect size (β = -0.0027, p = 0.0693), with the intercept indicating a significant overall positive effect (β = 0.1184, p = 0.003). This pattern suggests that longer interventions tended to produce slightly smaller effects, though the relationship did not achieve conventional statistical significance. This finding appears counterintuitive, as intervention science typically assumes a dose-response relationship wherein greater exposure produces larger benefits. However, several explanations may account for this unexpected pattern. First, longer interventions may experience higher attrition rates, with students dropping out over time, potentially biasing effect size estimates downward. Second, sustained interventions may face implementation fidelity challenges, with quality deteriorating over extended implementation periods due to fatigue, competing demands, or waning enthusiasm among implementers and participants. Third, diminishing returns may characterize skill-based interventions, with early sessions producing the largest gains and later sessions offering progressively smaller incremental benefits.

Alternatively, this pattern may reflect a spurious association arising from confounding with other intervention characteristics. Brief, intensive interventions may be preferentially delivered in targeted formats to students with identified needs, whereas longer-duration interventions may be more commonly implemented as universal programs reaching all students regardless of symptomatology. If this confounding is present, the apparent negative association between duration and effectiveness may actually reflect the universal-versus-targeted distinction rather than a true duration effect. This interpretation aligns with previous findings by Sanchez et al. [

8], who reported that services implemented multiple times per week produced particularly strong effects (

g = 0.50), suggesting that intervention intensity (frequency) may be more important than total duration. Future research should examine intervention dosage more comprehensively, considering total contact hours, session frequency, session length, and program duration as distinct dimensions that may differentially influence outcomes.

4.8. Theoretical Foundation: The Theory-Practice Gap

The analyses examining theoretical foundations revealed unexpected and puzzling patterns. Interventions that did not employ any explicit theory (g = 0.117, p = 0.065) produced larger effects than those using a single theory (g = 0.068, p = 0.081) or multiple theories (g = 0.056, p = 0.323), though none of these differences achieved statistical significance. Similarly, interventions that did not measure theory-relevant constructs showed larger effects (g = 0.125, p = 0.018) compared to those that explicitly assessed theoretical mediators (g = 0.054, p = 0.234). These findings appear paradoxical and contradict theoretical expectations that explicitly theory-grounded interventions with measured mechanisms should demonstrate superior effectiveness through precise targeting of change processes.

Several interpretations of these counterintuitive patterns merit consideration. First, these findings may reflect measurement and coding issues rather than true theoretical phenomena. The classification of interventions as atheoretical versus theory-based relied on authors’ descriptions in published reports, which may incompletely capture the actual theoretical underpinnings guiding intervention design. Many interventions described as atheoretical may implicitly draw upon established theoretical principles without explicitly articulating theoretical frameworks. Conversely, interventions nominally grounded in theory may implement theoretical principles superficially or inadequately, leading to a disconnect between stated theory and actual practice. Second, these patterns may indicate that theory-relevant construct measurement adds assessment burden without corresponding benefit, particularly in universal prevention programs where comprehensive assessment may detract from intervention delivery time and student engagement. Third, the small sample sizes within theory-related subgroups (n = 3 for atheoretical interventions) substantially limit the stability and interpretability of these estimates.

These findings align with Kim et al.’s [

12] content analysis revealing significant theory-practice gaps in school counselor-led interventions, wherein 62.2% of studies mentioned some theoretical framework but only 37.8% used a single theory, 20% combined multiple theories, fewer than half (42.2%) measured theory-relevant constructs, and only 20% discussed results in relation to theory. This pattern suggests widespread inconsistency in how theory is conceptualized, operationalized, and evaluated in school-based intervention research. More troublingly, these findings raise questions about whether explicit theoretical articulation actually improves intervention design and implementation or whether it is primarily an academic exercise that may not translate into enhanced student outcomes. However, Lemberger-Truelove et al. [

11] found that interventions grounded in either single or multiple counseling theories (

g = 0.316 and

g = 0.405, respectively) substantially outperformed atheoretical approaches (

g = 0.169), directly contradicting the present findings. This discrepancy highlights the need for more rigorous investigation of theory’s role in school-based intervention research, including examination of theory implementation fidelity, assessment of specific theoretical mechanisms, and exploration of which theoretical frameworks demonstrate the strongest evidence for particular outcome domains and student populations.

4.9. Study Design and Geographic Context

Two additional patterns deserve mention. First, randomized controlled trials (

g = 0.148) produced larger effect sizes than cluster randomized controlled trials (

g = 0.056), consistent with methodological research demonstrating that individual randomization typically yields more precise effect size estimates with reduced design effects compared to cluster randomization. This difference likely reflects statistical properties of the designs rather than true differences in intervention effectiveness, underscoring the importance of accounting for design features in meta-analytic synthesis. Second, interventions conducted in the United States (

g = 0.160,

p = 0.016) demonstrated larger effects than those conducted in other countries (

g = 0.052,

p = 0.034). This geographic pattern could reflect multiple factors including cultural differences in intervention responsiveness, variations in baseline mental health symptomatology and service access across countries, differences in educational system structures and school-based mental health infrastructure, or publication bias favoring studies with larger effects from the United States where school-based intervention research is more established. Bradshaw et al. [

23] documented that school-based mental health interventions can be feasibly implemented and effective in low- and middle-income countries, though adaptations are often necessary. The present findings suggest that cross-cultural adaptation and validation remain important priorities to ensure intervention effectiveness across diverse global contexts.

4.10. Implications for Practice

The significant overall effect size observed in this meta-analysis supports continued investment in school-based mental health interventions as an essential component of comprehensive student support systems. Given that only 20% of adolescents with diagnosable mental health conditions receive adequate treatment (Whitney & Peterson, 2019), school-based programming serves a critical gap-filling function that justifies implementation even when individual student effect sizes are modest. Schools should implement multitiered systems of support that strategically combine universal, selective, and indicated interventions [

22], as the present findings revealed substantially larger effects for targeted interventions (

g = 0.148,

p = 0.036) compared to universal programming (

g = 0.056,

p = 0.029). This differentiated approach optimizes resource allocation while maximizing both population-level impact and individual student outcomes, capitalizing on the efficiency of targeted approaches while retaining the equity advantages and destigmatization benefits of universal programming.

Decisions about intervention delivery format and provider type should be informed by both the present findings and feasibility considerations. Small-group interventions (

g = 0.138,

p = 0.068) and combined individual-small group formats (

g = 0.867,

p = 0.005) demonstrated larger effects than classroom-based approaches (

g = 0.059,

p = 0.018), suggesting that group formats offer an optimal balance between effectiveness and efficient use of professional time. Schools should strategically leverage the specialized expertise of school-based mental health professionals, who produced the largest effects (

g = 0.157) compared to teacher-delivered interventions (

g = 0.041), while simultaneously building teacher capacity to integrate mental health promotion into daily instruction. Lemberger-Truelove et al. [

11] demonstrated that school counselor-delivered interventions produce significant effects (

g = 0.308), particularly in racially and ethnically diverse schools (

g = 0.449 for middle school,

g = 0.434 for high school), supporting differentiated models wherein teachers deliver universal promotion while school counselors and psychologists provide targeted interventions for students with identified needs.

Cultural responsiveness and implementation quality must be prioritized to ensure equitable outcomes and program effectiveness. Extensive evidence documents persistent inequities in mental health service access across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups [

15,

16], necessitating that schools explicitly monitor differential uptake and outcomes across student demographic groups and ensure cultural and linguistic appropriateness of intervention content. As Westerlund et al. [

26] documented, implementation barriers including inadequate funding, insufficient time, competing priorities, staff turnover, and limited training commonly undermine school-based programming, underscoring the need for comprehensive initial training, ongoing coaching, protected time for intervention delivery, and sustained administrative support. Finally, the unexpected negative association between intervention duration and effect size (

β = -0.0027,

p = 0.0693), though non-significant, suggests that brief, intensive interventions may be as effective as extended programs, though schools should consider booster sessions or integration into ongoing programming to sustain initial gains over time.

4.11. Limitations

Several limitations warrant consideration when interpreting the present findings. First, the small number of included studies (k = 18) substantially limited statistical power to detect moderator effects, likely accounting for the absence of statistically significant moderation despite meaningful differences in effect size magnitudes across subgroups. Meta-analytic moderator analyses require substantially larger samples than primary effect size estimation to achieve adequate power, and the patterns observed in subgroup analyses should be interpreted as preliminary evidence requiring replication in larger samples rather than definitive conclusions about the presence or absence of moderation. Second, the decision to restrict the sample to rigorous RCT and CRCT designs enhances internal validity and causal inference but potentially limits generalizability to the full range of school-based intervention research, including quasi-experimental studies and interventions implemented under pragmatic real-world conditions with fewer research supports.

Third

, the coding of moderator variables necessarily involved subjective judgment and relied upon information reported in published articles, which may incompletely capture intervention characteristics, implementation processes, and theoretical foundations. The particularly puzzling findings regarding theoretical foundations highlight challenges in reliably categorizing interventions based on published descriptions that may not fully articulate actual intervention design and implementation. Relatedly, the analysis combined diverse outcomes into omnibus effect size estimates, including academic, social, emotional, behavioral, and mental health. While this approach provides a comprehensive assessment of overall intervention impact, it obscures potential differential effects across outcome domains. Previous research has demonstrated that school-based interventions show larger effects for externalizing problems compared to internalizing problems [

8], and the present analysis could not examine such domain-specific effects. In fact, most primary studies provided insufficient information to examine racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic variation in intervention effectiveness, precluding meaningful analysis of disparities—a critical limitation given persistent inequities in adolescent mental health service access and outcomes. Future research must prioritize reporting of subgroup analyses to enable examination of differential intervention effects across demographic groups.

Also the geographic distribution of included studies likely overrepresents high-income English-speaking countries, particularly the United States, limiting generalizability to low- and middle-income countries and culturally diverse contexts. The finding that U.S.-based studies produced larger effects than international studies highlights the importance of cultural adaptation and validation in cross-national implementation. Finally, the meta-analysis synthesized study-level effect sizes rather than individual participant data, precluding examination of individual-level moderators such as baseline symptom severity, comorbidity patterns, prior treatment history, family factors, and other student characteristics that may influence intervention responsiveness. Individual participant data meta-analysis represents an important direction for future research to illuminate for whom interventions work best and under what conditions.

5. Conclusions

This meta-analysis provides evidence that school-based mental health interventions produce small but statistically significant improvements in adolescent academic, social, emotional, behavioral, and mental health outcomes, with an overall effect size of g = 0.068. The remarkable consistency of effects across studies, reflected in minimal heterogeneity, suggests that these benefits are reliable and robust across diverse intervention types, student populations, and implementation contexts. While none of the examined moderators achieved statistical significance in formal tests, likely due to limited statistical power, the patterns observed across subgroups offer preliminary insights into factors that may influence intervention effectiveness. Targeted interventions appear to produce larger effects than universal programs, small-group formats may optimize the balance between effectiveness and efficiency, and interventions delivered by trained mental health professionals may outperform teacher-delivered approaches, though these interpretations require confirmation in larger samples.

The modest magnitude of observed effects should not diminish recognition of the important role school-based mental health interventions play in comprehensive adolescent mental health promotion and intervention systems. Given severe treatment gaps wherein only 20% of adolescents with mental health needs receive adequate services, and persistent disparities in service access across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups, school-based programming serves a critical function by providing accessible support within the natural environment where youth spend substantial time. Even small effect sizes can translate into meaningful population-level impact when interventions reach large numbers of students who would otherwise not access services. The field has reached a point where the question is no longer whether school-based interventions work—the evidence clearly indicates they do—but rather how to optimize their implementation, for whom they work best, under what conditions, through what mechanisms, and how to ensure equitable access and outcomes across all student groups.

Future research must address several critical priorities to advance the science and practice of school-based mental health intervention. First, adequately powered studies examining moderators of intervention effectiveness are needed to clarify which intervention approaches, delivery formats, and implementation strategies optimize outcomes for diverse student populations. Second, research must prioritize examination of intervention effects across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups to inform equity-focused implementation and address persistent mental health disparities. Third, investigation of implementation factors, including training models, coaching supports, organizational contexts, and systems-level facilitators and barriers, can illuminate how to support high-quality implementation at scale. Fourth, longitudinal research examining the durability of intervention effects and the need for booster sessions or ongoing reinforcement is essential to understand whether brief school-based interventions produce sustained benefits. Fifth, research must rigorously examine theoretical mechanisms through which interventions produce effects, resolving the puzzling findings regarding theory’s role and clarifying which change processes are most important to target. Finally, cross-cultural research investigating intervention effectiveness, adaptation needs, and implementation strategies across diverse international contexts can inform global scaling efforts and ensure that evidence-based practices are accessible to adolescents worldwide.

School-based mental health interventions are a promising and increasingly essential strategy for promoting adolescent mental health, particularly in the context of rising mental health concerns among young people globally and the substantial treatment gaps that leave most adolescents without adequate support. The evidence synthesized in this meta-analysis supports continued investment in school-based programming while simultaneously highlighting opportunities for optimization through strategic targeting, thoughtful selection of delivery formats, leveraging of specialized expertise, attention to dosage and intensity, and unwavering commitment to implementation quality and equity. By situating mental health support within schools, that is where adolescents are already present, engaged, and accessible, we can extend the reach of mental health promotion and intervention to underserved populations, reduce barriers to access, destigmatize help-seeking, and ultimately improve mental health outcomes for all young people as they navigate the critical developmental period of adolescence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.LT.; methodology, M.L.T., D.L., and H.K.; formal analysis, D. L.; data curation, H.K., D.H., and R.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.T, D.L., H.K., and Z.K.; writing—review and editing, M.L.T, D.L., H.K., D.H., R.D., and Z.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data utilized for the current manuscript can be garnered by contacting the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CBT |

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| CRCT |

Cluster Randomized Controlled Trails |

| LMIC |

Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| PICOS |

Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study |

| PRISMA |

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

| RCT |

Randomized Controlled Trails |

| SEL |

Social Emotional Learning |

References

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization: Mental Health of Adolescents. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Copeland, W.E.; Alaie, I.; Jonsson, U.; Shanahan, L. Associations of childhood and adolescent depression with adult psychiatric and functional outcomes. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 60, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, D.G.; Peterson, M.D. US national and state-level prevalence of mental health disorders and disparities of mental health care use in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 389–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegria, M.; Carson, N.J.; Goncalves, M.; Keefe, K. Disparities in treatment for substance use disorders and co-occurring disorders for ethnic/racial minority youth. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2011, 50, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, M.; Hoagwood, K.; Stephan, S.; Ford, T. Mental health interventions in schools in high-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemberger-Truelove, M.E.; Bowers Parker, H. An Evidence-Based Systems Approach to School Counseling: Advocating Student-within-Environment; Routledge Press: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, A.L.; Cornacchio, D.; Poznanski, B.; Golik, A.M.; Chou, T.; Comer, J.S. The effectiveness of school-based mental health services for elementary-aged children: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 57, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Neitzel, A. School-based mental health interventions targeting depression or anxiety: A meta-analysis of rigorous randomized controlled trials for school-aged children and adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2023, 52, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekamge, R.B.; Jain, R.; Sheen, J.; Lee, Y.Y.; Byrne, S.; Allen, N.B.; Olsson, C.A. Whole-school mental health and wellbeing interventions for adolescents: A systematic review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2025, 54, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemberger-Truelove, M.E.; Li, D.; Kim, H.; Wills, L.; Thompson, K.; Lee, Y.-Y. Effectiveness of school counselor-delivered social and emotional learning interventions: A meta-analysis. J. Couns. Dev. 2025, 103, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lemberger-Truelove, M.E.; Wills, L.N.; Basner, E.J.; Tipton, J.L. Use of theory in school counselor-delivered intervention research: A systematic content analysis. Prof. Sch. Couns. 2024, 27, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Mei, Z.; Wang, Z.; Luo, S. Effects of school-based resilience interventions on resilience in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 346, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrone, P. Debate: where to next for universal school-based mental health interventions? Universal versus targeted school-based mental health interventions: a health economic perspective. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2025, 30, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunin, L.; Pagán, J.A.; Yu, G.; Squires, A.; Cohen, S. Racial and ethnic disparities in school mental health service utilization among US adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2025, 76, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrast, L.; Himmelstein, D.U.; Woolhandler, S. Trends and racial disparities in mental health visits by young people. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 964–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Costello, E.J.; Leblanc, W.; Sampson, N.A.; Kessler, R.C. Socioeconomic status and adolescent mental disorders. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1742–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, M.T.; Bruns, E.J.; Lee, K.; Cox, S.; Coifman, J.; Mayworm, A.; Lyon, A.R. Rates of mental health service utilization by children and adolescents in schools and other common service settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2021, 48, 420–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raknes, S.; Pallesen, S.; Himle, J.A.; Bjaastad, J.F.; Wergeland, G.J.; Hoffart, A.; Haugland, B.S. Brief versus standard CBT for anxiety disorders: A randomized non-inferiority trial. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, C.; Eveleigh, A.; McCarthy, M.; Funaro, M.; Ponnock, A.; Chow, J.C.; Durlak, J. A meta-analysis of school-based social and emotional learning interventions: Improved well-being, school climate, and academic achievement across diverse global contexts. Psychol. Sch. 2023, 60, 4499–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, D.L.; Griffiths, K.; Kuyken, W.; Crane, C.; Foulkes, L.; Parker, J.; Dalgleish, T. Research review: The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on cognition and mental health in children and adolescents--a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2019, 60, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]