Submitted:

29 October 2025

Posted:

30 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

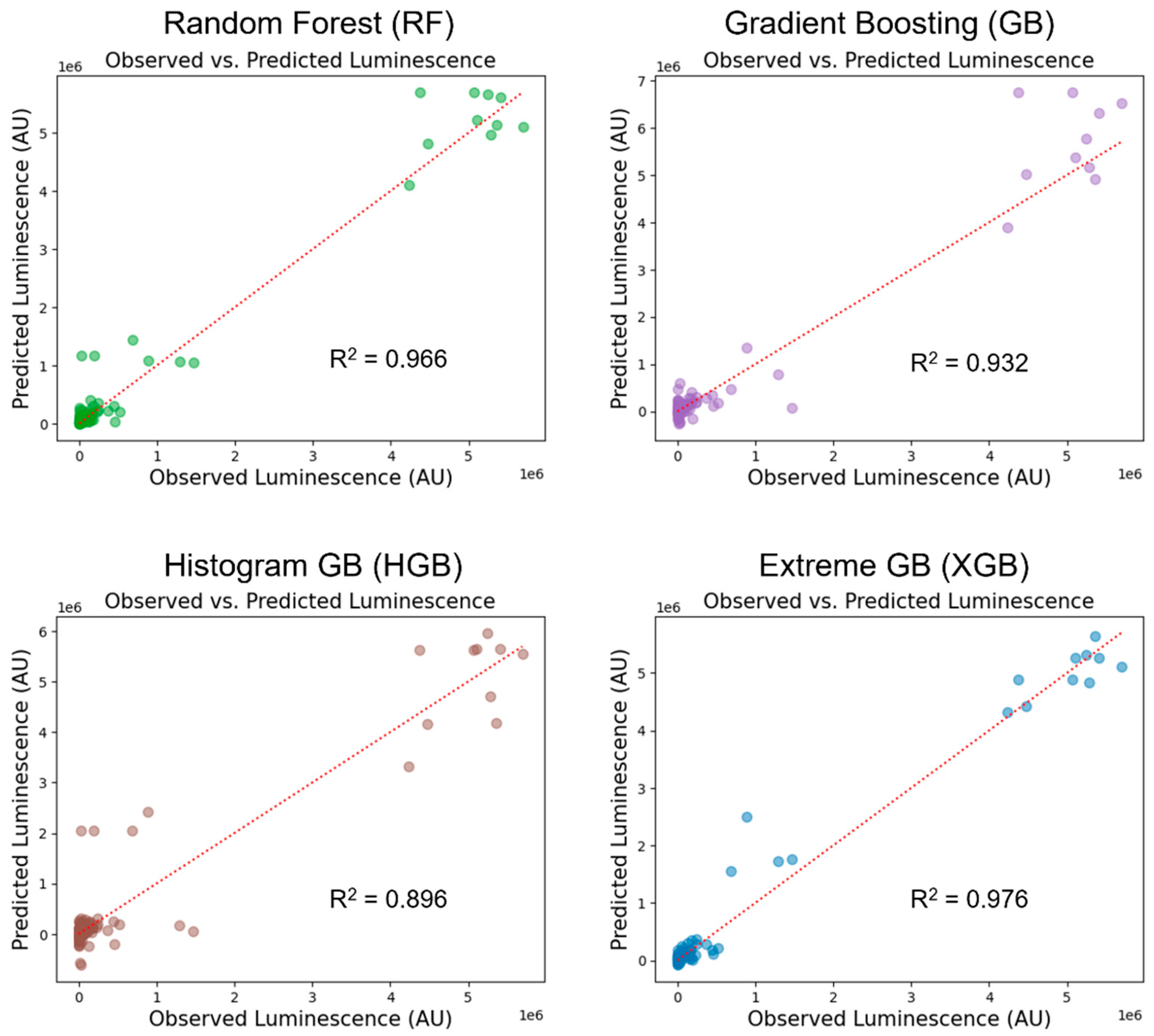

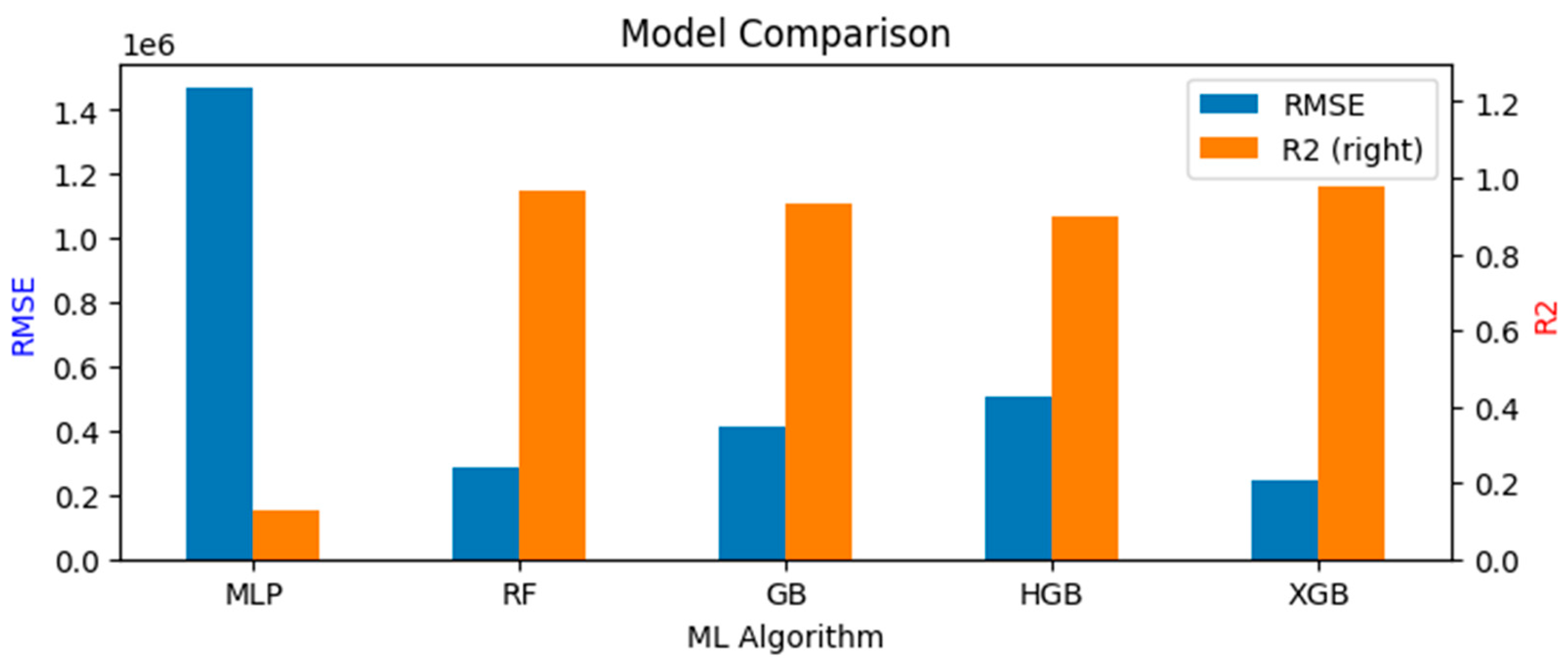

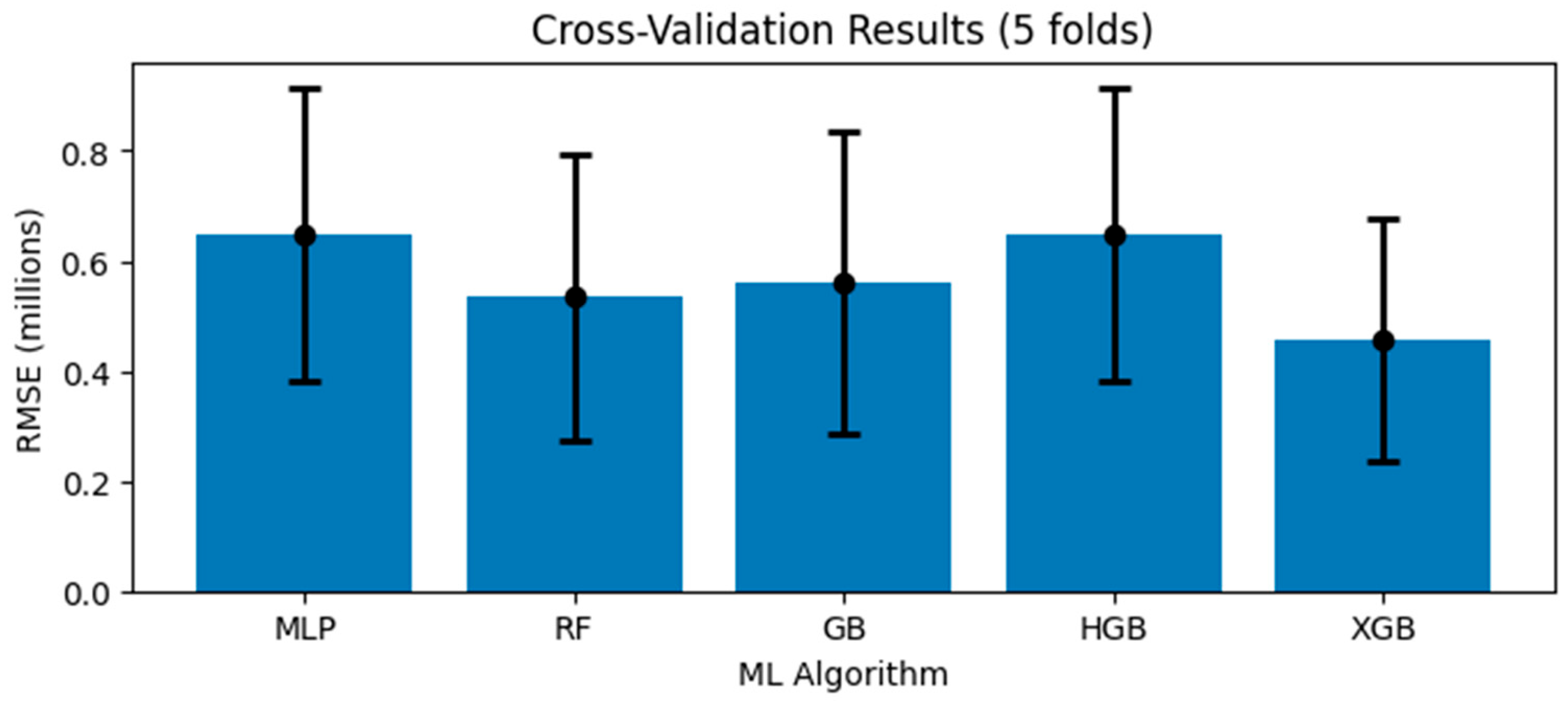

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LNP | lipid nanoparticle |

| IAJD | ionizable amphiphilic Janus dendrimer |

| DNP | dendrimersome nanoparticle |

| mRNA | messenger ribonucleic acid |

| TE | transfection efficiency |

| ML | machine learning |

| MLP | multilayer perceptron |

| RF | random forest |

| GB | gradient boosting |

| HGB | histogram gradient boosting |

| XGB | extreme gradient boosting |

Appendix A

- alpha=0.019622237860359305

- beta_1=0.9426622228918426

- beta_2=0.981530345935695

- hidden_layer_sizes=125

- learning_rate_init=0.09606142561070556, max_fun=16835

- max_iter=283, momentum=0.7203909798571576

- n_iter_no_change=8, power_t=0.1997727727616871

- tol=0.000609016759626102

- validation_fraction=0.09996090982612142

- ccp_alpha=0.08553361303023148

- max_features=0.7751438544438484

- min_impurity_decrease=0.017023303243833054

- min_samples_leaf=1

- min_samples_split=3

- min_weight_fraction_leaf=0.003221536045037288

- n_estimators=90

- alpha=0.8680638990931918

- ccp_alpha=0.015750676206814862

- learning_rate=0.1286760958685088

- max_depth=9

- min_impurity_decrease=0.016915940022235176

- min_samples_leaf=1

- min_samples_split=2

- min_weight_fraction_leaf=0.01042397382655489

- n_estimators=76

- subsample=0.5210194554669745

- tol=0.00024704561523662574

- validation_fraction=0.16996781330352345

- l2_regularization=0.029404467922097156

- learning_rate=0.19281183995796564

- max_bins=212

- max_features=0.500763060875326

- max_iter=112

- max_leaf_nodes=13

- min_samples_leaf=10

- n_iter_no_change=12

- validation_fraction=0.26853568630405517

- objective='reg:squarederror'

- max_depth=5

- n_estimators = 802

- learning_rate=0.0105

- reg_lambda=0.17

- reg_alpha=1

- min_child_weight=1

- subsample=1.00

- colsample_bytree=1

Appendix B

-

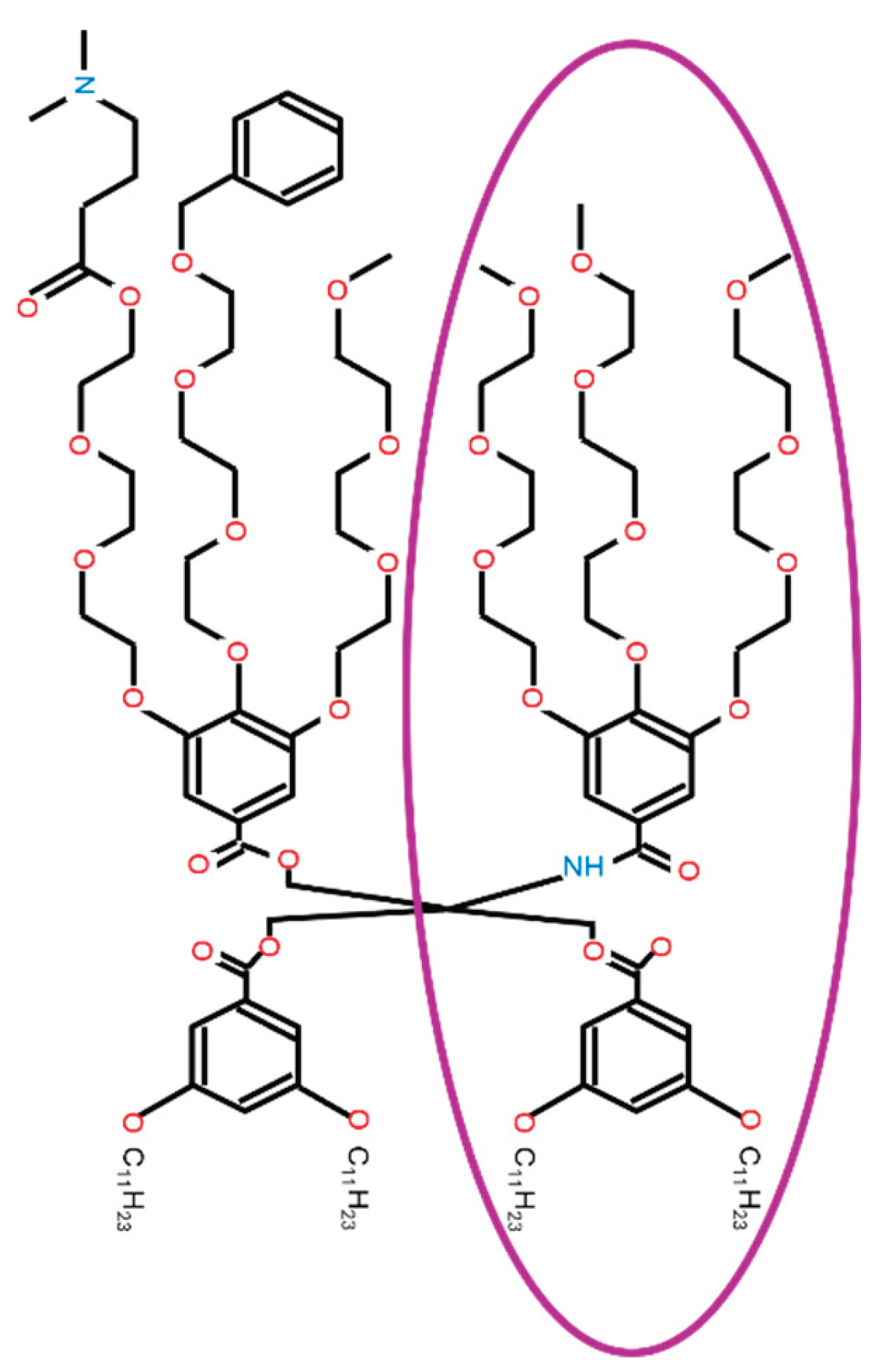

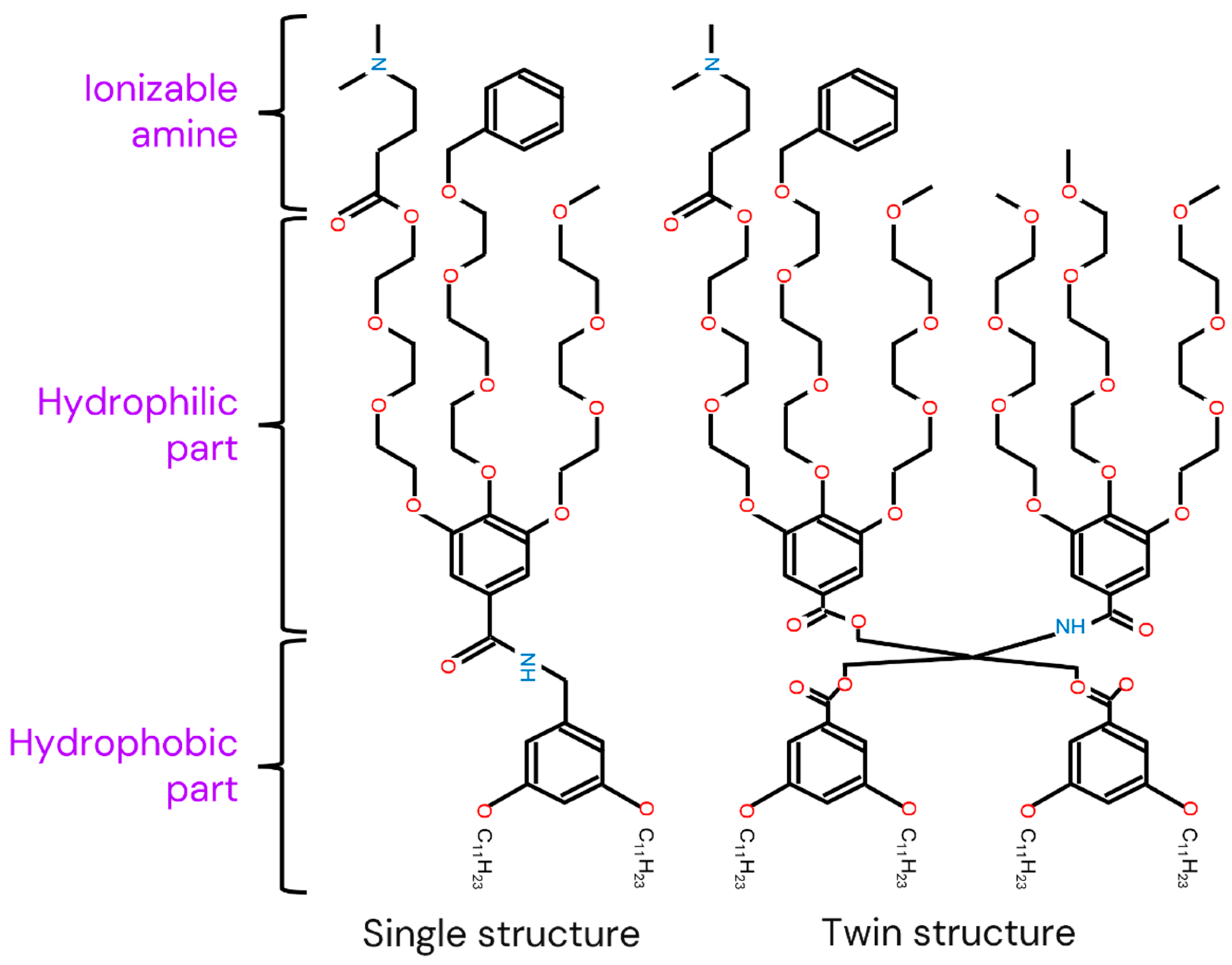

twin: [0, 1]

- ○

- 0: single structure

- ○

- 1: twin structure

- ○

- If twin = 0, then Linker = tH* = 0.

-

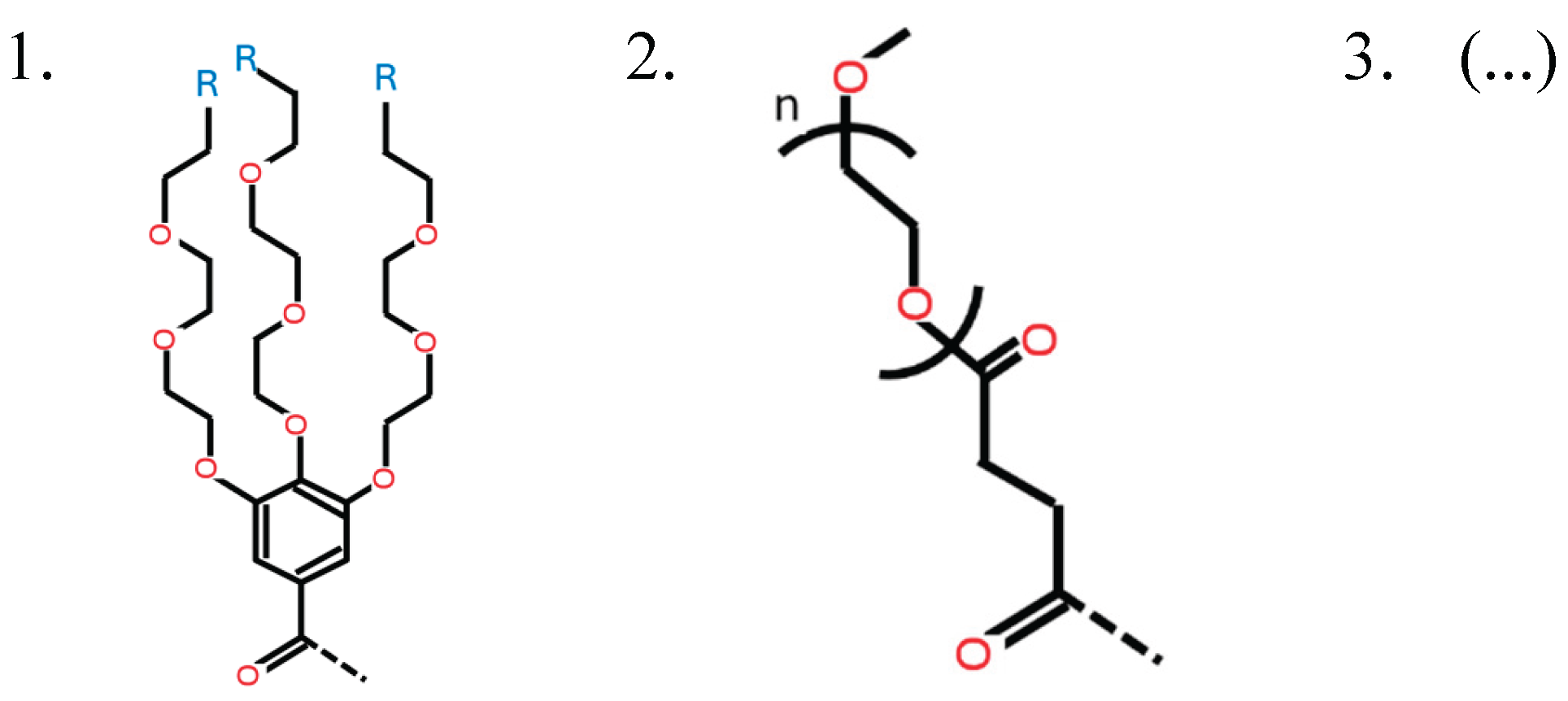

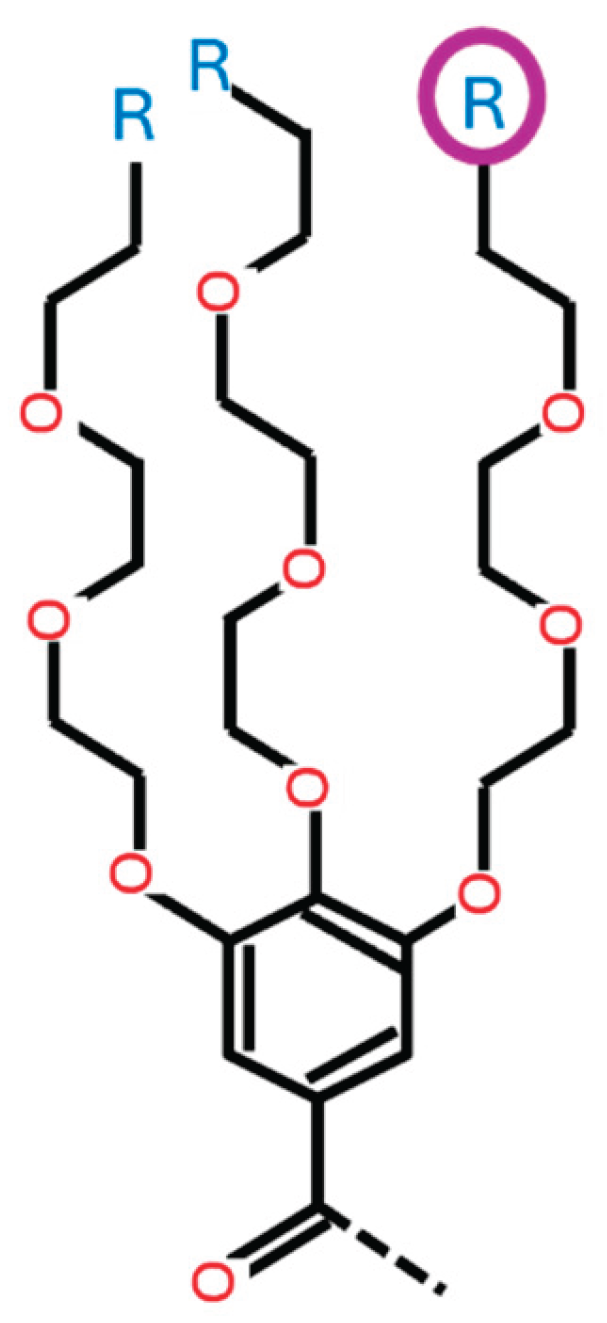

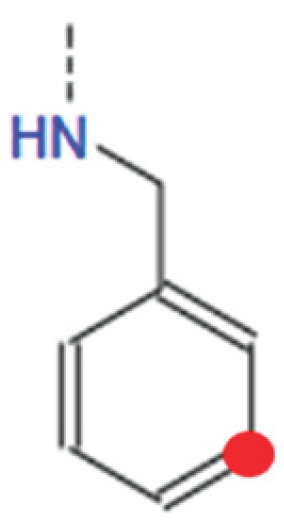

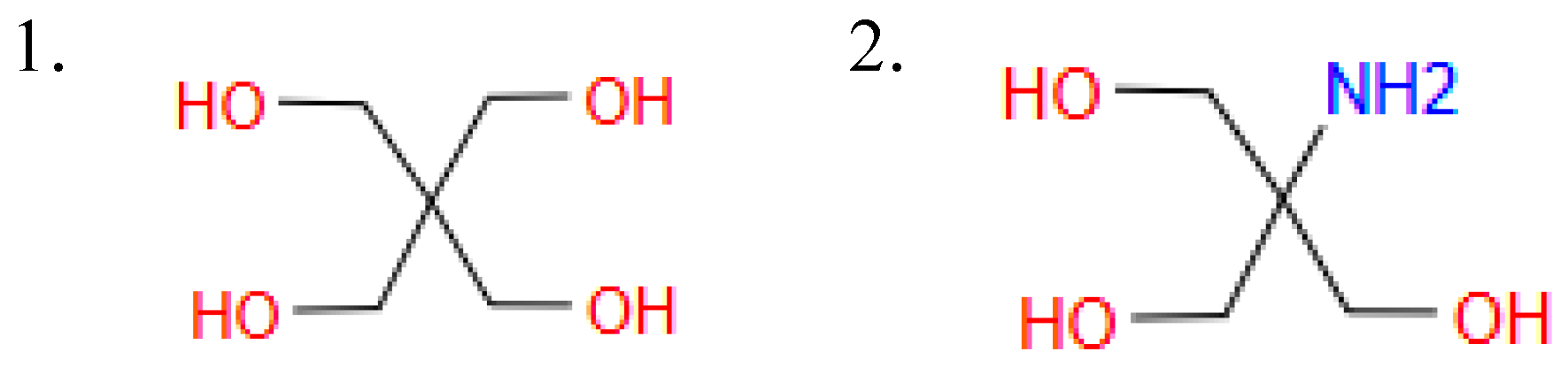

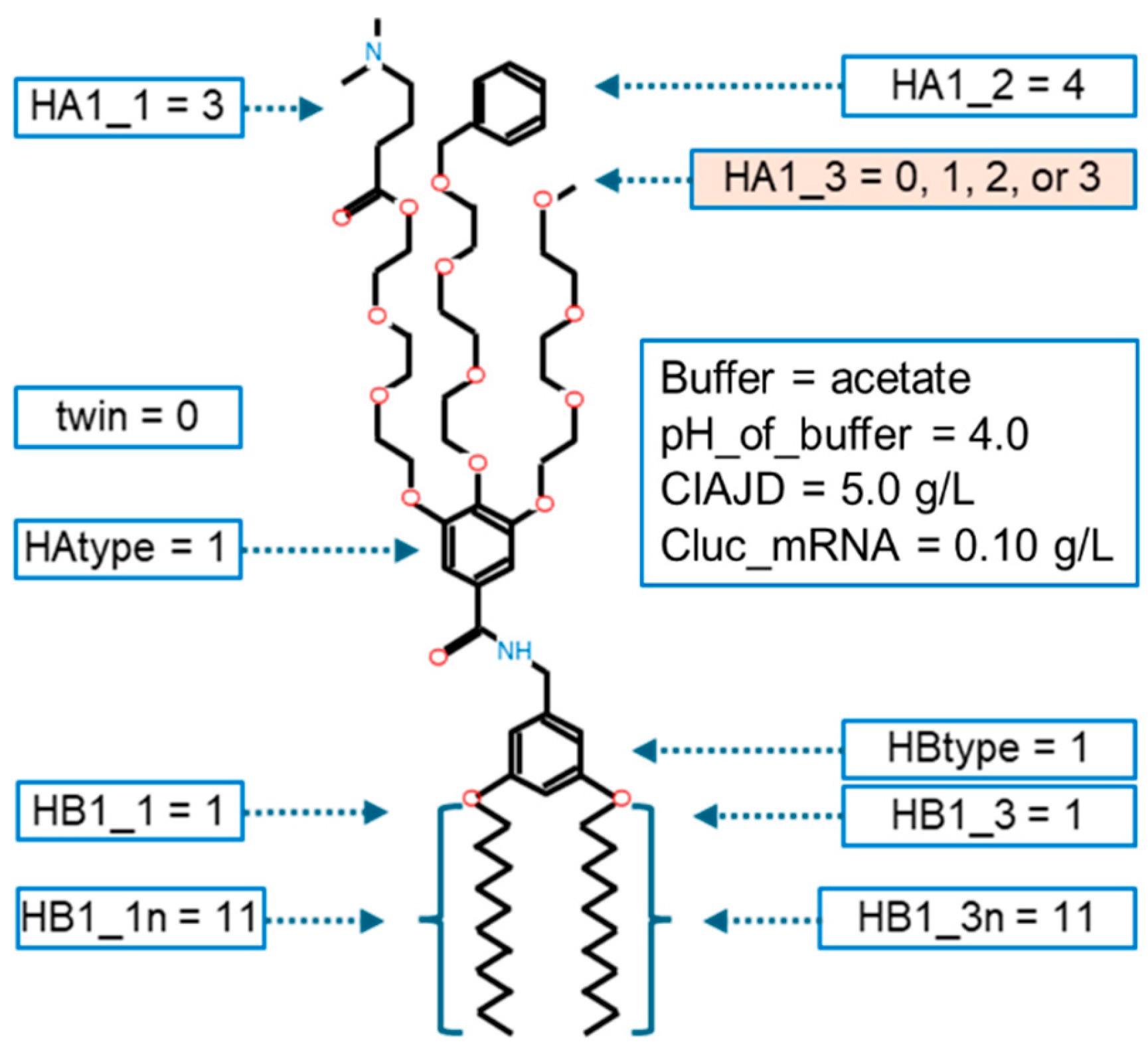

HAtype: [1, 2, 3]. This variable determines the type of hydrophilic part. There are three different types as shown in Figure B1.

- ○

- 1: three branches from a Benzene ring

- ○

- 2: a chain of carbons and oxygens with a length n

- ○

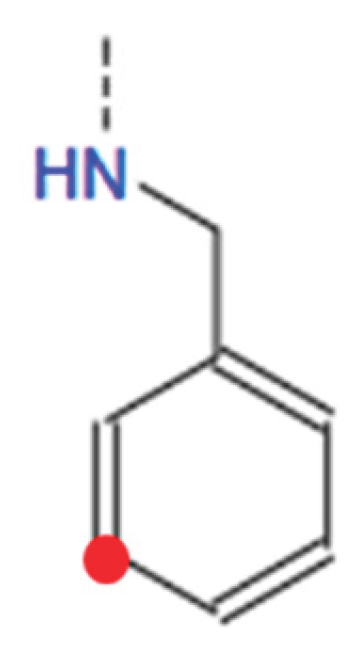

- 3: no hydrophilic acid, i.e., ionizable amine only, as illustrated below.

- ○

- If HAtype = 1 or 3, then HA2n = 0.

- HA2n: [0, 3, 4, 8, 45] This variable determines the length of the carbon and oxygen chain (HAtype 2). This variable is valid only if HAtype = 2. Otherwise, the value of this variable is 0.

-

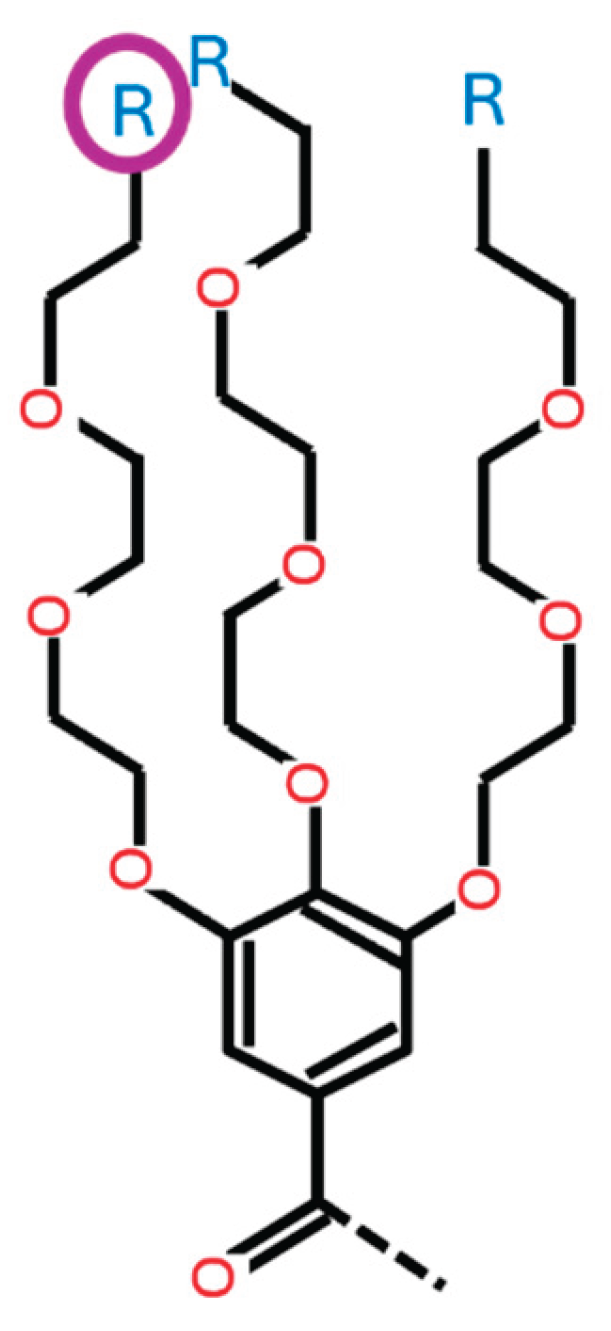

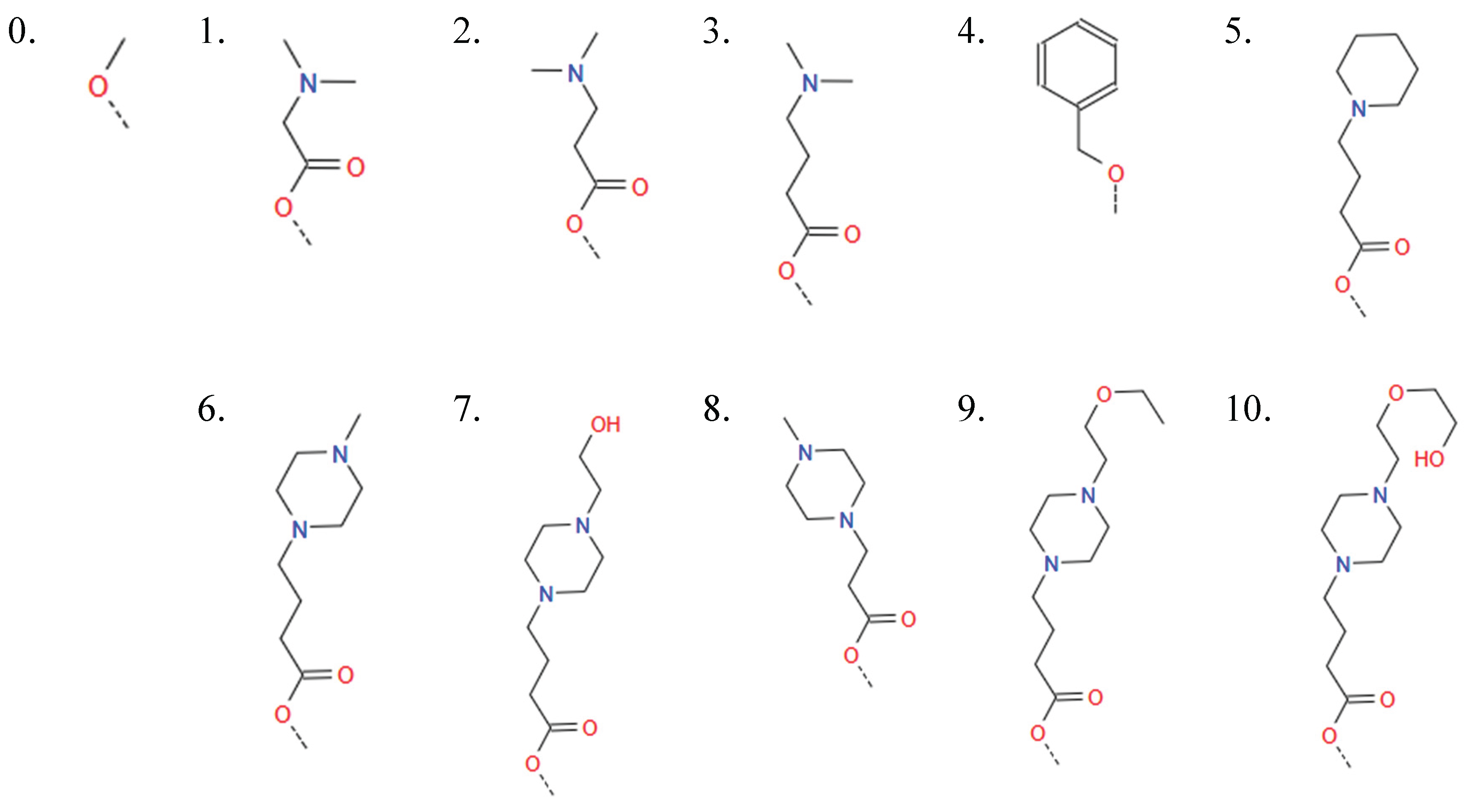

HA1_1: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] This variable determines the type of ionizable amine at the tip of the 1st branch from the benzene ring (HAtype 1) as shown in Figure B2. There are 11 different types as illustrated in Figure B3.

- ○

- If HAtype is not 1, this variable is invalid and its value is 0.

- ○

- If HAtype is 1 and HA1_1 is 0, it means that this branch does not have ionizable amine.

-

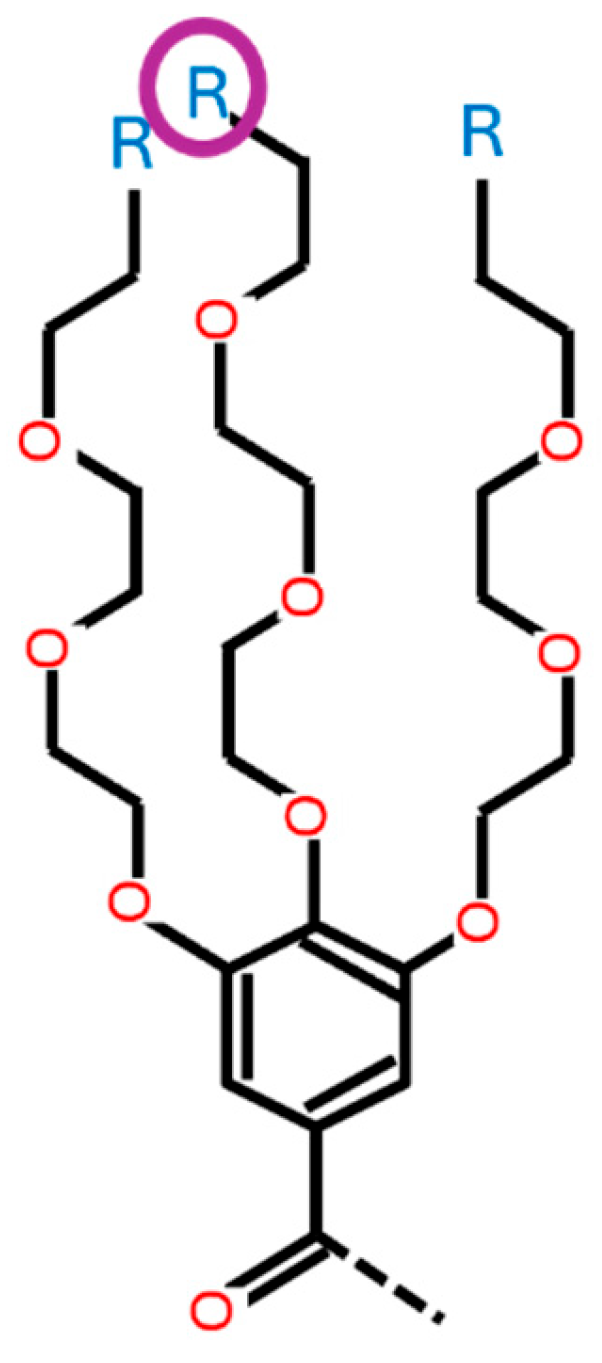

HA1_2: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

- ○

- This variable determines the type of ionizable amine at the tip of the 2nd branch from the benzene ring (HAtype 1) as shown in Figure B4. There are 11 different types as illustrated in Figure B3.

-

HA1_3: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

- ○

- This variable determines the type of ionizable amine at the tip of the 3rd branch from the benzene ring (HAtype 1) as shown in Figure B5. There are 11 different types as illustrated in Figure B3.

-

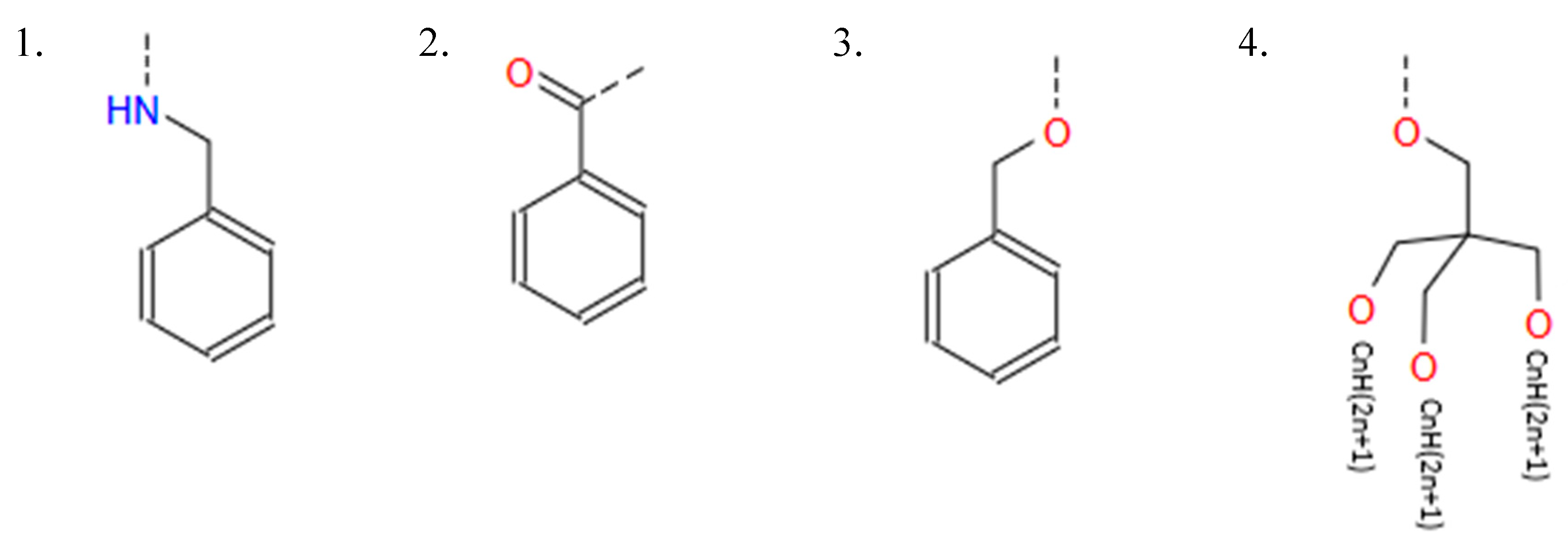

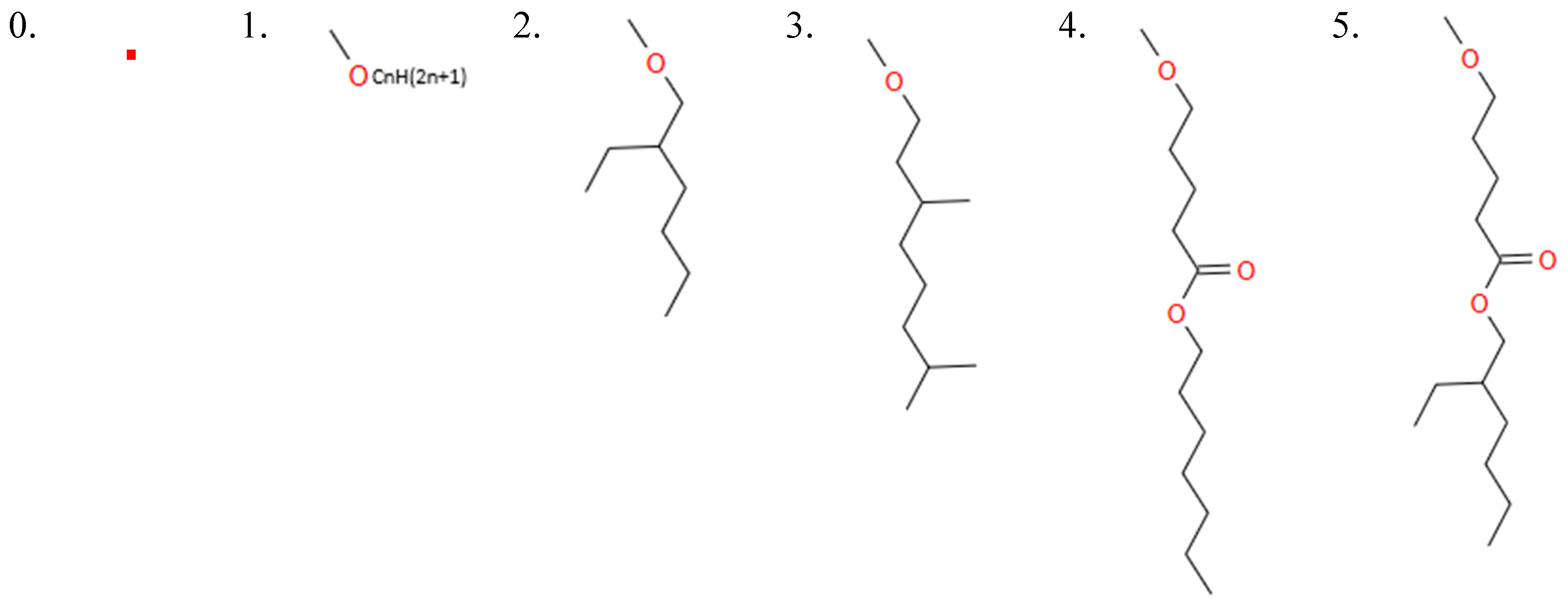

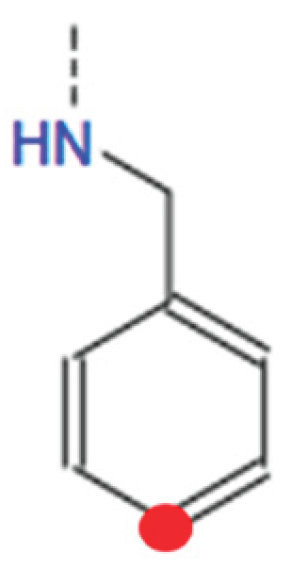

HBtype: [1, 2, 3, 4] The hydrophilic part of IAJD is connected to a hydrophobic part and this variable determines the type of hydrophobic part as shown in Figure B6.

- ○

- 1: Hydrophobic Benzyl Amines (Benzene ring connected with HN)

- ○

- 2: Hydrophobic Acids (Benzene ring connected with oxygen (O) with double links)

- ○

- 3: Benzene ring connected with O

- ○

- 4: Aliphatic Alcohol (three prongs connected with CnH2n+1 (CnH(2n+1)) for each with no Benzene ring) as illustrated below.

- ○

- The dashed line indicates the connection to the hydrophilic part.

- ○

- If HBtype is 1, 2, or 3, HB4n = 0.

-

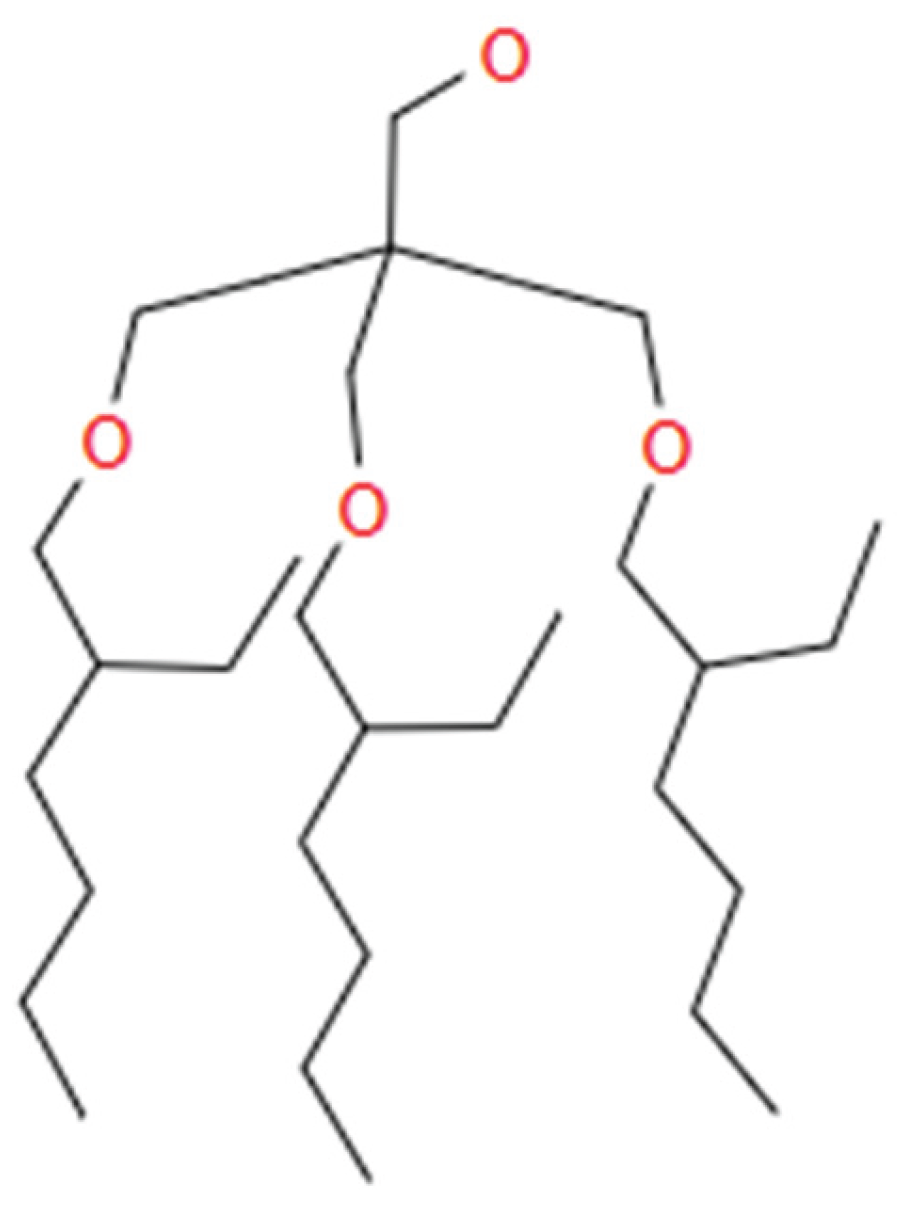

HB4n: [0, 1, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15] This variable determines the length of tail (# of carbons) when HBtype is 4 (Aliphatic Alcohol).

- ○

- This variable is valid only when HBtype is 4.

- ○

- If HBtype is not 4, the value of this variable is 0.

- ○

- If HBtype is 4 and each tail is a two-prong tail as illustrated in Figure B7, the value of this variable is 1.

- ○

- Other values for this variable indicate the tail length (# of carbons) for CnH2n+1.

-

HB1_1: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5] This variable determines the type of tail at the 1st tail point from the benzene ring of HBtype 1 as shown in Figure B8.

- ○

- There are 6 different types as shown in Figure B9.

- ○

- 0 means that there is no tail at the 1st tail point or not applicable.

- HB1_1n: [0, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18] This variable indicates the length of the tail at tail point 1 from the benzene ring (BHtype 1), i.e. n value for CnH(2n+1). 0 means no tail at tail point 1 or N/A.

-

HB1_2: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5] This variable determines the type of tail at the 2nd tail point from the benzene ring of HBtype 1 as shown in Figure B10.

- ○

- There are 6 different types as shown in Figure B9.

- ○

- 0 means that there is no tail at the 2nd tail point or not applicable.

-

HB1_2n: [0, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18] This variable indicates the length of the tail at tail point 2 from the benzene ring (BHtype 1), i.e. n value for CnH(2n+1).

- ○

- 0 means no tail at tail point 2 or N/A.

-

HB1_3: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5] This variable determines the type of tail at the 3rd tail point from the benzene ring of HBtype 1 as shown in Figure B11.

- ○

- There are 6 different types as shown in Figure B9.

- ○

- 0 means that there is no tail at the 3rd tail point or not applicable.

-

HB1_3n: [0, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18] This variable indicates the length of the tail at tail point 3 from the benzene ring (BHtype 1), i.e., n value for CnH(2n+1).

- ○

- 0 means no tail at tail point 3 or N/A.

-

Linker: [0, 1, 2] This variable indicates the type of linker when IAJD has a twin structure. There are two different types as shown in Figure B12.

- ○

- 0: N/A, i.e., not twin.

- ○

- 1: symmetric linker type

- ○

- 2: asymmetric linker type, which has NH on one side.

-

tHAtype: [0, 1, 2, 3] This variable is HAtype for twin. Twin refers to the one with NH as shown in Figure B13.

- ○

- 0: This IAJD does not have a twin structure (twin = 0) or N/A. If Linker is asymmetric (Linker = 2), NH side is the twin.

-

tHA2n: [0, 3, 4, 8, 45] This variable is HA2n for twin. 0: This IAJD does not have a twin structure (twin = 0) or N/A.tHA1_1: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5] This variable is HA1_1 for twin.

- ○

- 0: This IAJD does not have a twin structure (twin = 0) or N/A.

- ○

- tHA1_2: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5] This variable is HA1_2 for twin.

- ○

- 0: This IAJD does not have a twin structure (twin = 0) or N/A.

-

tHA1_3: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5] This variable is HA1_3 for twin.

- ○

- 0: This IAJD does not have a twin structure (twin = 0) or N/A.

-

tHBtype: [0, 1, 2] This variable is HBtype for twin.

- ○

- Based on the current data set, type 3 or 4 doesn't exist for twin yet.

- ○

- 0: Not have a twin structure (twin = 0) or N/A.

-

tHB1_1: [0, 1, 2, 3] This variable is HB1_1 for twin.

- ○

- 0: No tail at the 1st tail point, does not have a twin structure (twin = 0), or N/A.

-

tHB1_1n: [0, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12] This variable is HB1_1n for twin.

- ○

- 0: Not have a twin structure (twin = 0) or N/A.

-

tHB1_2: [0, 1, 2, 3] This variable is HB1_2 for twin.

- ○

- 0: No tail at the 2nd tail point, does not have a twin structure (twin = 0), or N/A.

-

tHB1_2n: [0, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12] This variable is HB1_2n for twin.

- ○

- 0: Not have a twin structure (twin = 0) or N/A.

-

tHB1_3: [0, 1, 2, 3] This variable is HB1_3 for twin.

- ○

- 0: No tail at the 3rd tail point, does not have a twin structure (twin = 0), or N/A.

-

tHB1_3n: [0, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12] This variable is HB1_3n for twin.

- ○

- 0: Not have a twin structure (twin = 0) or N/A.

-

If HAtype = 1, then HA1_1 + HA1_2 + HA1_3 >= 1.

- ○

- (at least 1 branch from hydrophilic benzene ring)

-

If HBtype = 1, then HB1_1 + HB1_2 + HB1_3 >= 1.

- ○

- (at least 1 tail from hydrophobic benzene ring)

Appendix C

- TE: 7108495.0, params: (1, 4.0, 5.0, 0.1, 0, 1, 0, 3, 4, 0, 1, 0, 1, 11, 0, 0, 1, 11, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)

- TE: 7108495.0, params: (1, 4.0, 5.0, 0.1, 0, 1, 0, 3, 4, 1, 1, 0, 1, 11, 0, 0, 1, 11, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)

- TE: 7108495.0, params: (1, 4.0, 5.0, 0.1, 0, 1, 0, 3, 4, 2, 1, 0, 1, 11, 0, 0, 1, 11, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)

- TE: 7108495.0, params: (1, 4.0, 5.0, 0.1, 0, 1, 0, 3, 4, 3, 1, 0, 1, 11, 0, 0, 1, 11, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)

-

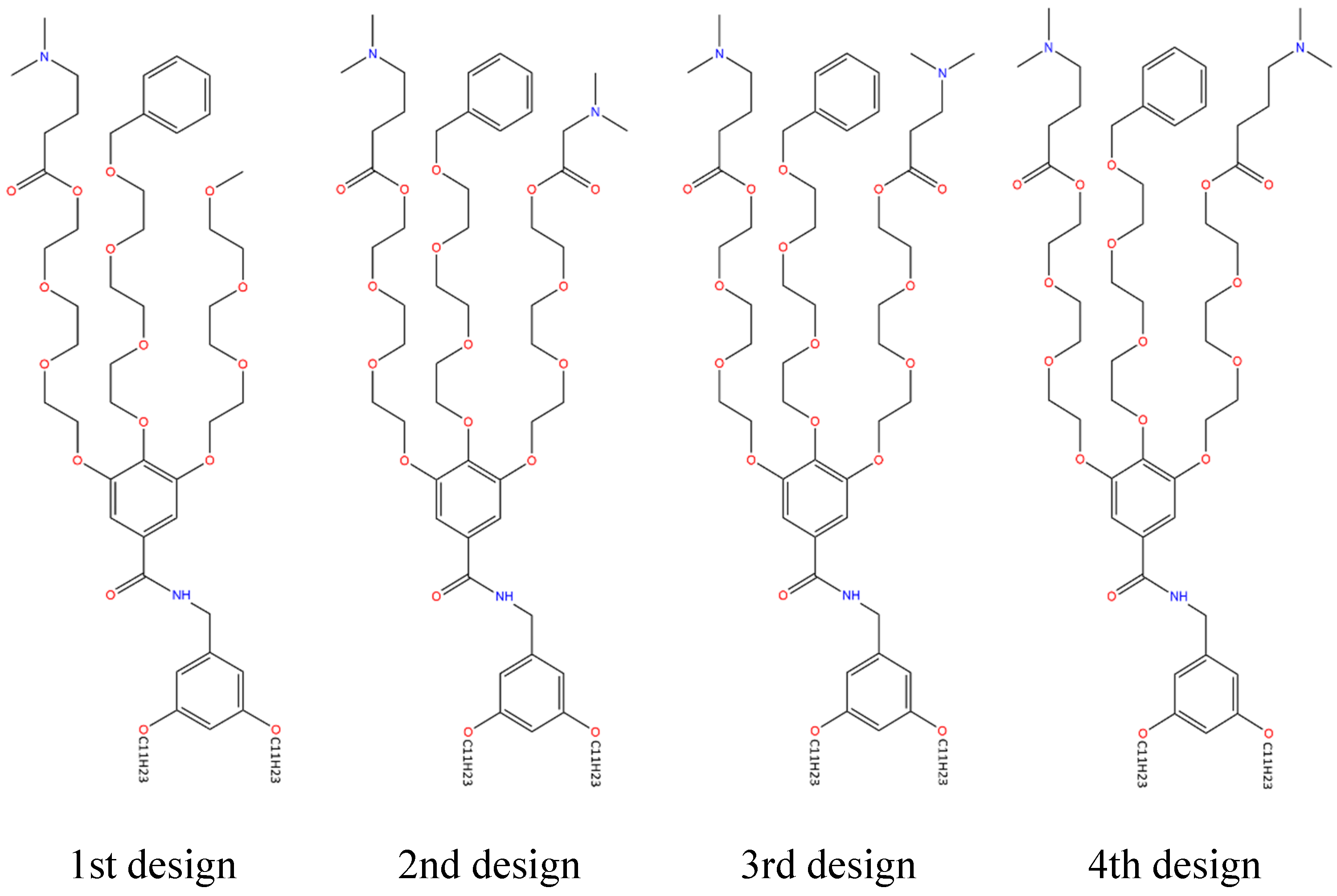

1st IAJD design

- ○

- CCCCCCCCCCCOc3cc(CNC(=O)c2cc(OCCOCCOCCOC)c(OCCOCCOCCOCc1ccccc1)c(OCCOCCOCCOC(=O)CCCN(C)C)c2)cc(OCCCCCCCCCCC)c3

- ○

- Synthetic accessibility: 9.46

-

2nd IAJD design

- ○

- CCCCCCCCCCCOc3cc(CNC(=O)c2cc(OCCOCCOCCOC(=O)CCCN(C)C)c(OCCOCCOCCOCc1ccccc1)c(OCCOCCOCCOC(=O)CN(C)C)c2)cc(OCCCCCCCCCCC)c3

- ○

- Synthetic accessibility: 10.00

-

3rd IAJD design

- ○

- CCCCCCCCCCCOc3cc(CNC(=O)c2cc(OCCOCCOCCOC(=O)CCCN(C)C)c(OCCOCCOCCOCc1ccccc1)c(OCCOCCOCCOC(=O)CCN(C)C)c2)cc(OCCCCCCCCCCC)c3

- ○

- Synthetic accessibility: 10.00

-

4th IAJD design (= IAJD22)

- ○

- CCCCCCCCCCCOc3cc(CNC(=O)c2cc(OCCOCCOCCOC(=O)CCCN(C)C)c(OCCOCCOCCOCc1ccccc1)c(OCCOCCOCCOC(=O)CCCN(C)C)c2)cc(OCCCCCCCCCCC)c3

- ○

- Synthetic accessibility: 10.00

- IAJD 34: synthetic accessibility 10.00

- IAJD 93: synthetic accessibility 6.76

- IAJD 249: synthetic accessibility 5.85

- IAJD 288: synthetic accessibility 7.28

Appendix D

| Variable | Possible values | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buffer | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||

| pH_of_buffer | 0.25 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 5.6 | ||||||

| CIAJD | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 5.00 | 6.00 | 7.00 | 8.00 | |

| Cluc_mRNA | 0.05 | 0.10 | ||||||||||

| twin | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||

| HAtype | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||||||

| HA2n | 0 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 45 | |||||||

| HA1_1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| HA1_2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| HA1_3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| HBtype | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||||

| HB4n | 0 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| HB1_1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| HB1_1n | 0 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| HB1_2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| HB1_2n | 0 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| HB1_3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| HB1_3n | 0 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| Linker | 0 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| tHAtype | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||

| tHA2n | 0 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 45 | |||||||

| tHA1_1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| tHA1_2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| tHA1_3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| tHBtype | 0 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| tHB1_1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||

| tHB1_1n | 0 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||||||

| tHB1_2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||

| tHB1_2n | 0 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||||||

| tHB1_3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||

| tHB1_3n | 0 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||||||

| ||||||||||||

References

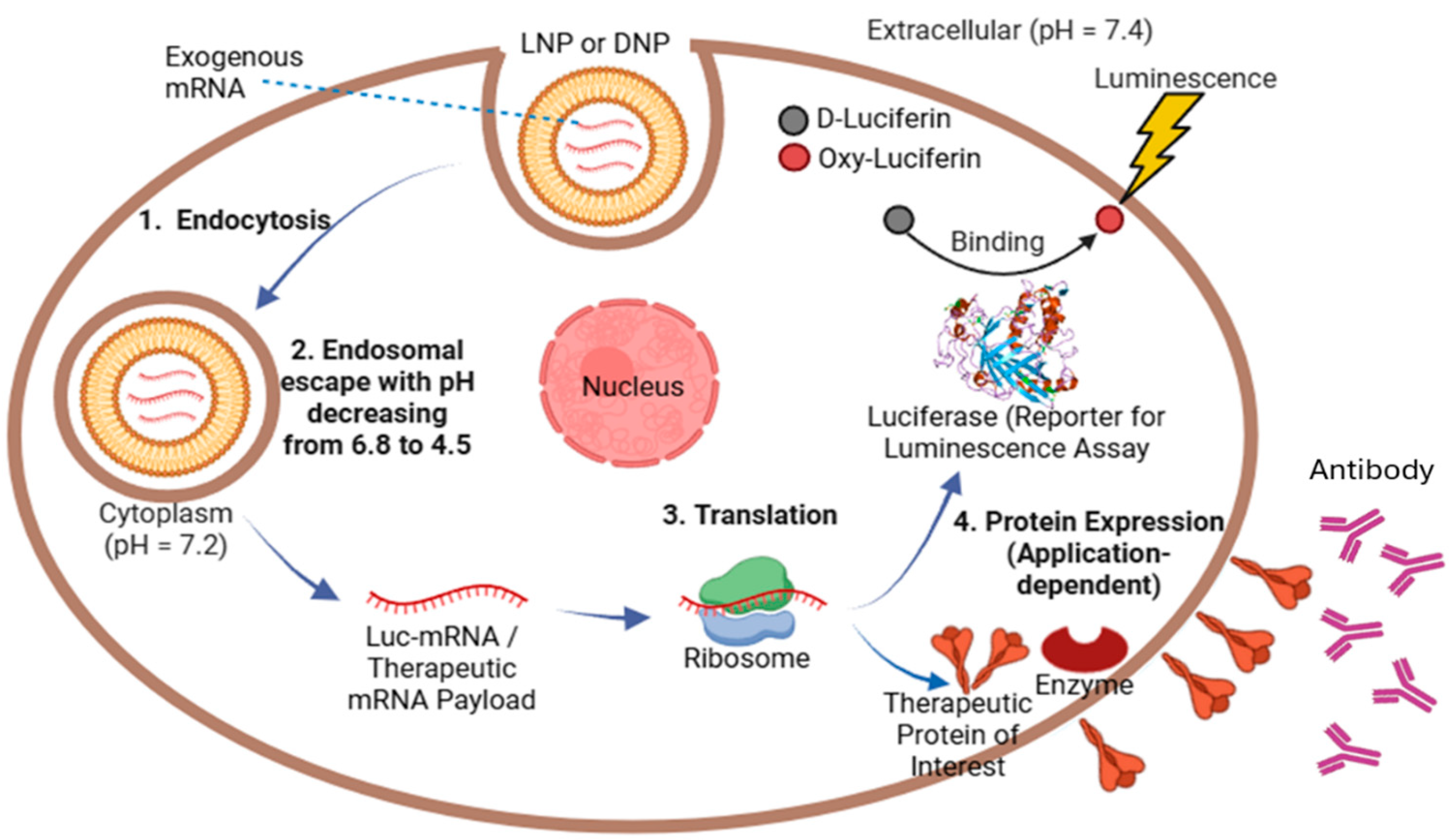

- Nitika, J. Wei, and A.-M. Hui, The Delivery of mRNA Vaccines for Therapeutics. Life, 2022. 12(8). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., Atochina-Vasserman, E. N., Maurya, D. S., Huang, N., Xiao, Q., Ona, N., Liu, M., Shahnawaz, H., Ni, H., Kim, K., Billingsley, M. M., Pochan, D. J., Mitchell, M. J., Weissman, D., and Percec, V. , One-Component Multifunctional Sequence-Defined Ionizable Amphiphilic Janus Dendrimer Delivery Systems for mRNA. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2021. 143(31): p. 12315–12327. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., Atochina-Vasserman, E. N., Maurya, D. S., Liu, M., Xiao, Q., Lu, J., Lauri, G., Ona, N., Reagan, E. K., Ni, H., Weissman, D., & Percec, V., Targeted Delivery of mRNA with One-Component Ionizable Amphiphilic Janus Dendrimers. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2021. 143(43): p. 17975–17982. [CrossRef]

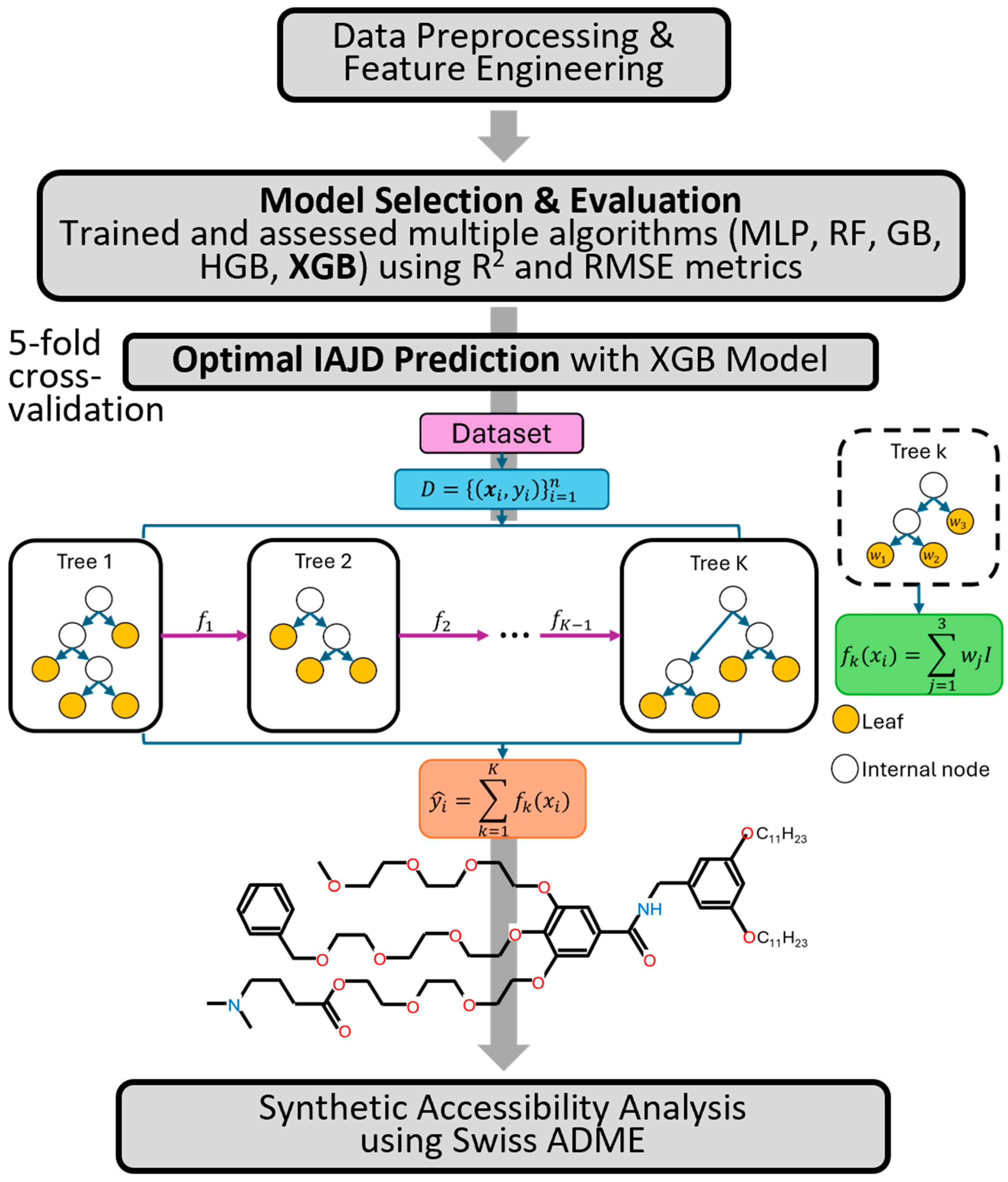

- Ding, D.Y., Zhang, Y., Jia, Y., Sun, J., Machine Learning-guided Lipid Nanoparticle Design for mRNA Delivery. ArXiv, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, R., et al., Recent trends and perspectives of artificial intelligence-based machine learning from discovery to manufacturing in biopharmaceutical industry. Journal of Pharmaceutical Investigation, 2023. 53: p. 803–826. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y., et al., Applications of artificial intelligence to lipid nanoparticle delivery. Particuology, 2024. 90: p. 88–97. [CrossRef]

- Li, B., et al., Accelerating ionizable lipid discovery for mRNA delivery using machine learning and combinatorial chemistry. Nature Materials, 2024. 23: p. 1002–1008. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., et al., AGILE Platform: A Deep Learning-Powered Approach to Accelerate LNP Development for mRNA Delivery. bioRxiv, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.M., T.J. Beck, and D. Ghosh, Applying machine learning to identify ionizable lipids for nanoparticle-mediated delivery of mRNA. bioRxiv, 2023.

- Ding, D.Y., et al., Machine Learning-guided Lipid Nanoparticle Design for mRNA Delivery. ArXiv, 2023.

- Kumar, G. and A.M. Ardekani, Machine-Learning Framework to Predict the Performance of Lipid Nanoparticles for Nucleic Acid Delivery. ACS applied bio materials, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.-H., et al., Rational Design of Lipid Nanoparticles for Enhanced mRNA Vaccine Delivery via Machine Learning. Small (Weinheim an Der Bergstrasse, Germany), 2024. 21. [CrossRef]

- Sato, S., et al., Understanding the Manufacturing Process of Lipid Nanoparticles for mRNA Delivery Using Machine Learning. Chemical & pharmaceutical bulletin, 2024. 72 6: p. 529–539. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M.R., et al., Understanding Intracellular Biology to Improve mRNA Delivery by Lipid Nanoparticles. Small methods, 2023. 7(9): p. e2201695–n/a. [CrossRef]

- Rafiei, M., A. Shojaei, and Y. Chau, Machine learning-assisted design of immunomodulatory lipid nanoparticles for delivery of mRNA to repolarize hyperactivated microglia. Drug Delivery, 2025. 32. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., et al., Machine learning engineered PoLixNano nanoparticles overcome delivery barriers for nebulized mRNA therapeutics. bioRxiv, 2024.

- Kumar, G. and A.M. Ardekani, Machine-Learning Framework to Predict the Performance of Lipid Nanoparticles for Nucleic Acid Delivery. ACS Applied Bio Materials, 2025. 8(5): p. 3717–3727. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., Atochina-Vasserman, E. N., Lu, J., Maurya, D. S., Xiao, Q., Liu, M., Adamson, J., Ona, N., Reagan, E. K., Ni, H., Weissman, D., & Percec, V. , The Unexpected Importance of the Primary Structure of the Hydrophobic Part of One-Component Ionizable Amphiphilic Janus Dendrimers in Targeted mRNA Delivery Activity. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2022. 144(11): p. 4746–4753. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J., Atochina-Vasserman, E. N., Maurya, D. S., Shalihin, M. I., Zhang, D., Chenna, S. S., Adamson, J., Liu, M., Shah, H. U. R., Shah, H., Xiao, Q., Queeley, B., Ona, N. A., Reagan, E. K., Ni, H., Sahoo, D., Peterca, M., Weissman, D., & Percec, V., Screening Libraries to Discover Molecular Design Principles for the Targeted Delivery of mRNA with One-Component Ionizable Amphiphilic Janus Dendrimers Derived from Plant Phenolic Acids. Pharmaceutics, 2023. 15(6). [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, D., Atochina-Vasserman, E. N., Maurya, D. S., Arshad, M., Chenna, S. S., Ona, N., Vasserman, J. A., Ni, H., Weissman, D., & Percec, V. , The Constitutional Isomerism of One-Component Ionizable Amphiphilic Janus Dendrimers Orchestrates the Total and Targeted Activities of mRNA Delivery. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2024. 146(6): p. 3627–3634. [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, D., Atochina-Vasserman, E. N., Lu, J., Maurya, D. S., Ona, N., Vasserman, J. A., Ni, H., Berkihiser, S., Park, W.-J., Weissman, D., & Percec, V. , Toward a Complete Elucidation of the Primary Structure–Activity in Pentaerythritol-Based One-Component Ionizable Amphiphilic Janus Dendrimers for In Vivo Delivery of Luc-mRNA. Biomacromolecules, 2025. 26(1): p. 726–737. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. and C. Guestrin. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. in The 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 2016. New York, NY, USA: ACM.

- NVIDIA. XGBoost. 2025 3/14/2025]; Available from: https://www.nvidia.com/en-us/glossary/xgboost/.

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Reason for Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Independent | Buffer Type | Critical factor in DNP formulation (non-structural) |

| pH of Buffer | ||

| Concentration of IAJD | ||

| Concentration of luciferase mRNA | ||

| Single or Twin Structure | Classification of overall structure | |

| Type / Size of Hydrophilic Part | Classification of a major IAJD component | |

| Type of Ionizable Amine | ||

| Type / Size of Hydrophobic Part | ||

| Linker Type | Characteristic of twin structure | |

| Dependent | Luminescence (AU) | Measure of mRNA TE |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).