1. Introduction

Exercise improves physical performance through metabolic, morphological, and neuromuscular adaptations [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. However, when training loads exceed an individual’s adaptive capacity and recovery is insufficient, performance may decline, increasing the risk of overtraining [

6]. To detect and prevent overtraining and optimize training adaptation, various biomarkers have been investigated to monitor physiological adaptation to exercise [

7,

8].

Among these biomarkers, cortisol—a final product of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis—is widely studied because its secretion increases in response to exercise as a stressor, depending on the intensity [

9,

10], duration [

11], and volume of training [

12,

13]. Cortisol exhibits a well-established diurnal rhythm, characterized by a peak in the early morning and a gradual decline throughout the day [

14,

15,

16]. A pronounced increase in cortisol levels typically occurs within the first 30 minutes after awakening, known as the cortisol awakening response (CAR) [

17]. CAR has demonstrated intra-individual reliability across multiple days [

17] and can be measured noninvasively via saliva sampling. When methodological confounders are adequately controlled, CAR exhibits a robust and consistent biphasic pattern, characterized by either an increase or a blunting, which is considered to potentially reflect the severity of stress-related symptoms in individual adaptation [

18]. Therefore, CAR has been widely studied as a biomarker of individual stress-related adaptation, particularly in the field of psychoneuroendocrinology [

18].

Recently, CAR has gained attention as a potential marker for monitoring physiological adaptation to exercise [

19]. However, studies examining exercise-induced changes in CAR remain limited, particularly under controlled laboratory conditions. Two studies have begun to address this gap: Ogasawara et al. [

20] examined the effects of 20-minute cycling at 40%, 60%, and 80% of maximal oxygen uptake (VO₂max) on CAR, reporting elevated CAR the following morning under the 80% condition compared to rest. In contrast, Anderson et al. [

21] found that 1-hour cycling at 70–75% peak power output in a hot and humid environment resulted in a low CAR. These laboratory-based findings suggest a biphasic pattern in CAR changes following acute high-intensity exercise, potentially reflecting the impact of exercise load from the previous day.

To our knowledge, no studies have investigated CAR changes in response to repeated, laboratory-controlled exercise stimuli administered over consecutive days. Anderson and Wideman [

19] speculated that CAR may increase during the initial phase of training and stabilize as physiological adaptation progresses. Minetto et al. [

22] conducted a field-based study in soccer players and reported that CAR increased in some individuals and decreased in others before and after a 7-day intensive training period, although training volume was not quantified and daily CAR fluctuations were not assessed. Considering that training adaptation is believed to result from the cumulative effects of repeated exercise stimuli [

23], it is important to further investigate CAR changes using structured and continuous exercise protocols under controlled conditions.

Therefore, this study aimed to examine how short-term, consecutive high-intensity exercise under laboratory-controlled conditions affects changes in CAR. Spina et al. [

24] reported increased mitochondrial enzyme activity and peak oxygen uptake (VO₂peak) following 7–10 days of cycling at 60–70% VO₂peak. Based on this finding, we hypothesized that 10 consecutive days of cycling at 80% VO₂max—a condition previously shown to elevate CAR [

20]—would induce CAR changes associated with training adaptation. While the exact timing of adaptation within the 10-day period remains unclear, we adopted the hypothesis proposed by Anderson and Wideman [

19]: that CAR increases during the initial phase of training and stabilizes as adaptation occurs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Four healthy adult males participated in this study. None of the participants had a history of smoking, irregular sleep patterns, hormonal disorders, psychiatric conditions, chronic low-carbohydrate diets, or habitual use of anabolic steroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Given the approximately two-week duration of the experimental protocol and the substantial time commitment required, a convenience sampling method was employed. Four participants were selected based on their availability, willingness, and ability to complete the 10 consecutive days of high-intensity cycling exercise sessions required in the study.

However, one participant was excluded from the analysis due to concerns that his data may have been influenced by a swimming competition he had participated in two days prior to the start of the experiment. Another participant was also excluded because his CAR values were consistently unstable throughout the experimental period, raising concerns about potential HPA axis dysfunction unrelated to the study. Consequently, data from two participants were included in the final analysis and presented as individual cases (Participant A: age 22 years, height 170 cm, body weight 60.6 kg; Participant B: age 22 years, height 175.9 cm, body weight 65.6 kg).

Although the use of convenience sampling and the reporting of individual cases limit the generalizability of the findings, the data obtained provide valuable preliminary insights that may inform future research in this specialized area.

Prior to the experiment, all participants provided both verbal and written informed consent. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Osaka University of Health and Sport Sciences (approval number: 20-4).

2.2. Study Design and Procedures

Participants visited the laboratory a total of 14 times during the study period. On the first visit, VO₂max was assessed using a maximal graded exercise test on a cycle ergometer. The test began at 0 W with a cadence of 60 revolutions per minute (rpm) and increased by 30 W every 2 minutes until the participants reached volitional exhaustion. Throughout the test, respiratory gases and heart rate (HR) were continuously measured, and ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) were recorded at the end of each exercise stage using the Borg 6–20 scale [

25]. VO₂max was considered valid and reliable based on the criteria outlined in the previous study [

10], if at least three of the following four conditions were met: (1) an increase in VO₂ of ≤0.15 L/min with increasing workload, (2) HR within ±5% of the age-predicted maximum, (3) respiratory exchange ratio (RER) ≥1.1, and (4) RPE ≥18.

Between 2 and 7 days after the VO₂max assessment, participants engaged 12 consecutive days of experimental sessions. The first two days consisted of seated rest sessions lasting 20 minutes, serving as baseline measurements. The subsequent 10 days involved 20-minute cycling exercise sessions performed daily at the fixed workload that was set on the first day, corresponding to 80% of each participant’s VO₂max. The session protocol was based on our previous study [

20].

To minimize intra- and inter-individual biological variation, all sessions were conducted at a standardized start time of 18:00 ± 30 minutes. During the rest sessions, participants were allowed to engage in light conversation and use smartphones, but sleep was prohibited. During the cycling exercise sessions, HR and respiratory gases were continuously monitored, and RPE were recorded every 10 minutes. Saliva samples were collected at five points: before the session (Pre), immediately after (Post-0), and at 10, 20, and 30 minutes post-exercise (Post-10, Post-20, Post-30). After each session, participants consumed a commercially prepared bento meal for dinner and received instructions regarding the nighttime and next-morning measurements. They were also provided with saliva collection tubes and straws before returning home.

At home, participants collected saliva samples at 21:00 (recovery 1) and 23:00 (recovery 2). Reminder messages were sent 15 minutes prior to each collection, and participants confirmed successful sampling. After recovery 2, participants received instructions for the next-morning measurements and a URL link to a Google Form was sent to participants for recording contextual information related to the next morning’s saliva sampling.

Upon waking the next morning, participants collected saliva samples at three points: immediately upon waking (C0), 15 minutes after waking (C15), and 30 minutes after waking (C30), for the evaluation of CAR. Between waking and 30 minutes post-waking, participants were instructed to complete a Google Form to record contextual information, including bedtime, wake time, saliva sampling times, and any relevant events during sleep or upon waking. They were asked to submit the form immediately after completing the C30 saliva sample. If discrepancies were identified between the reported C30 sampling time and the form submission time, participants were contacted to verify the accuracy of the morning procedures. Participant A had an average bedtime of 1:31 ± 1.0 h, wake time of 7:06 ± 1.2 h, and sleep duration of 5.9 ± 1.2 h across the 12 days. Participant B had an average bedtime of 1:19 ± 0.4 h, wake time of 7:47 ± 0.7 h, and sleep duration of 6.5 ± 0.6 h. Saliva samples collected at night and in the morning were stored in a household refrigerator (4°C) and submitted to the researchers at the next session.

On the day following the final (Day 10) cycling exercise session, a second VO₂max test was conducted using the same protocol and time of day as the initial assessment.

To minimize, as much as possible, the influence of confounding factors unrelated to the experimental exercise, participants were instructed to abstain from engaging in any strenuous physical activity, as well as from consuming caffeine and alcohol, from the day prior to the start of the study until its completion. In addition to standardizing dinner, participants were asked to maintain a consistent dietary pattern throughout the study period. Furthermore, the intake of food and carbohydrate-containing beverages was prohibited starting 4 hours before each session and again from 20:00 after the session until the completion of the following morning’s measurements. After returning home, participants were prohibited from engaging in part-time work and from drinking water, bathing, or brushing their teeth starting 1 hour prior to saliva sampling. During the morning sampling period, participants were instructed to refrain from brushing their teeth, drinking water, bathing, or returning to sleep for 30 minutes after waking. However, routine activities such as changing clothes or using the toilet were permitted, provided they did not significantly affect arousal levels.

2.3. Saliva Sample

Saliva samples were collected using the passive drool method, in which participants allowed saliva to accumulate naturally in the oral cavity for 2 minutes and then transferred it into a collection tube via a straw. The collected samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 minutes and stored at −80°C until analysis. On the day of analysis, samples were thawed, and cortisol concentrations were determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with a commercially available kit (Cortisol ELISA Kit [RE52611], IBL, Germany).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

As this study reports individual data, no statistical comparisons were performed. Instead, descriptive statistics were used to present each participant’s data, including mean values, standard deviations, and daily measurements for each variable.

Due to the extended commitment required during the approximately two-week duration of the study, no familiarization period was implemented. As a result, both participants exhibited elevated cortisol levels on the first day of baseline measurement, likely reflecting psychological stress or lack of adaptation to the experimental setting. Therefore, cortisol data from the first rest session were excluded from subsequent analyses, as they could not be considered valid baseline values. This limitation should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings of the present study.

3. Results

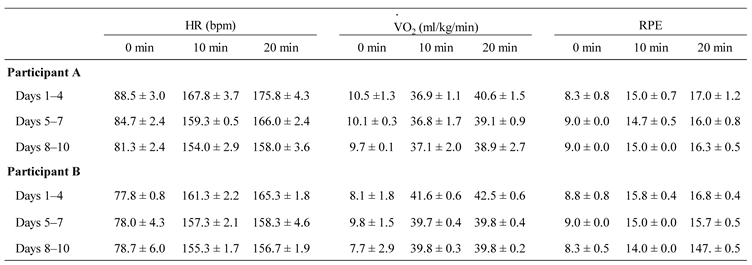

3.1. Physiological and Perceptual Responses

Table 1 presents the data for HR, VO₂, and RPE during the 20-minute cycling exercise sessions over 10 consecutive days for Participants A and B. All variables showed the highest values during Days 1–4, with a tendency for reduced responses observed in Days 5–7 and Days 8–10.

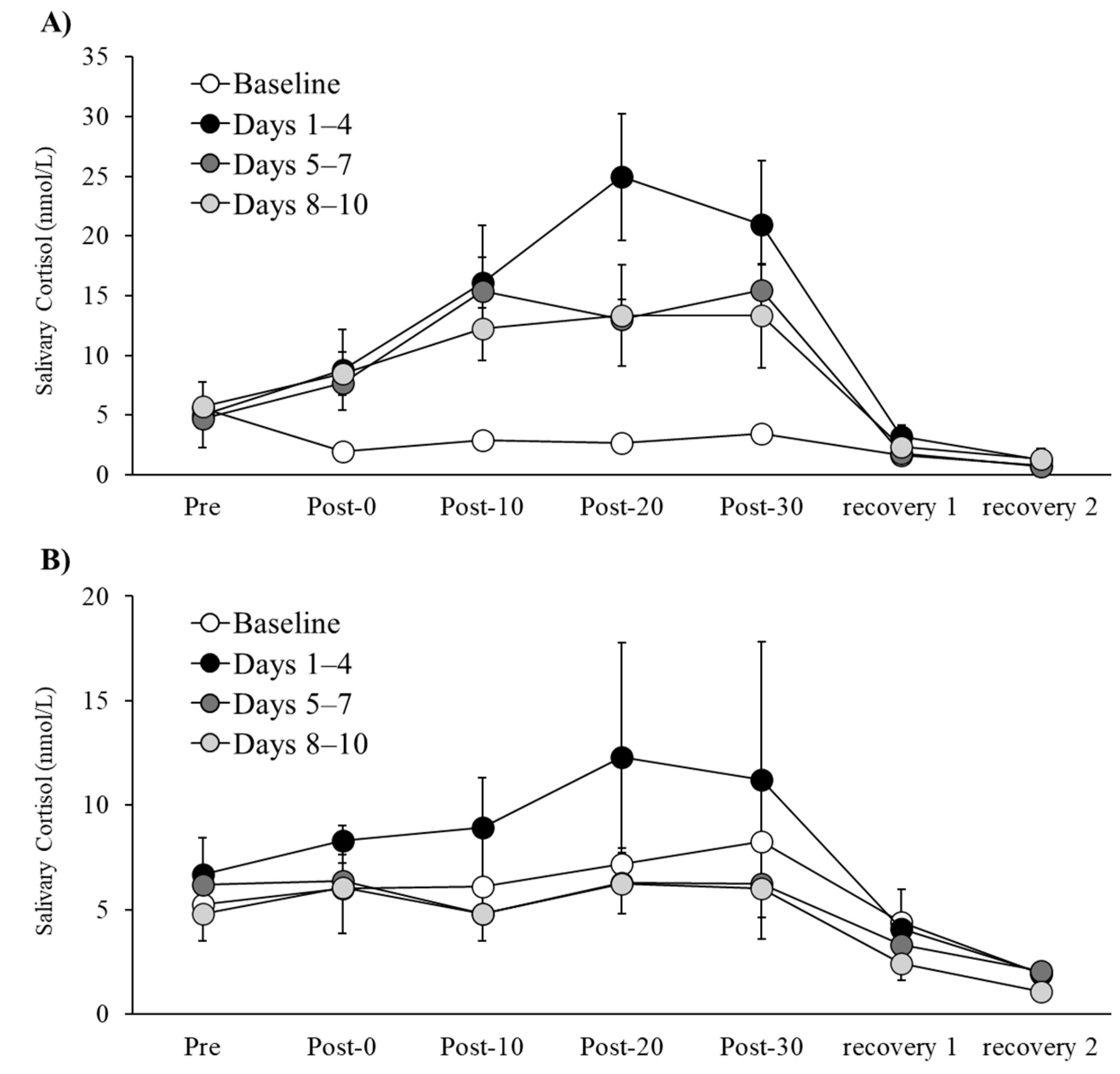

3.2. Acute Cortisol Responses

Figure 1 illustrates the temporal changes in acute cortisol concentrations for Participants A and B throughout the experimental session period. Similar to the patterns observed in HR, VO₂, and RPE data, the highest acute cortisol responses were recorded during Days 1–4, with a tendency for decreased responses during Days 5–7 and Days 8–10.

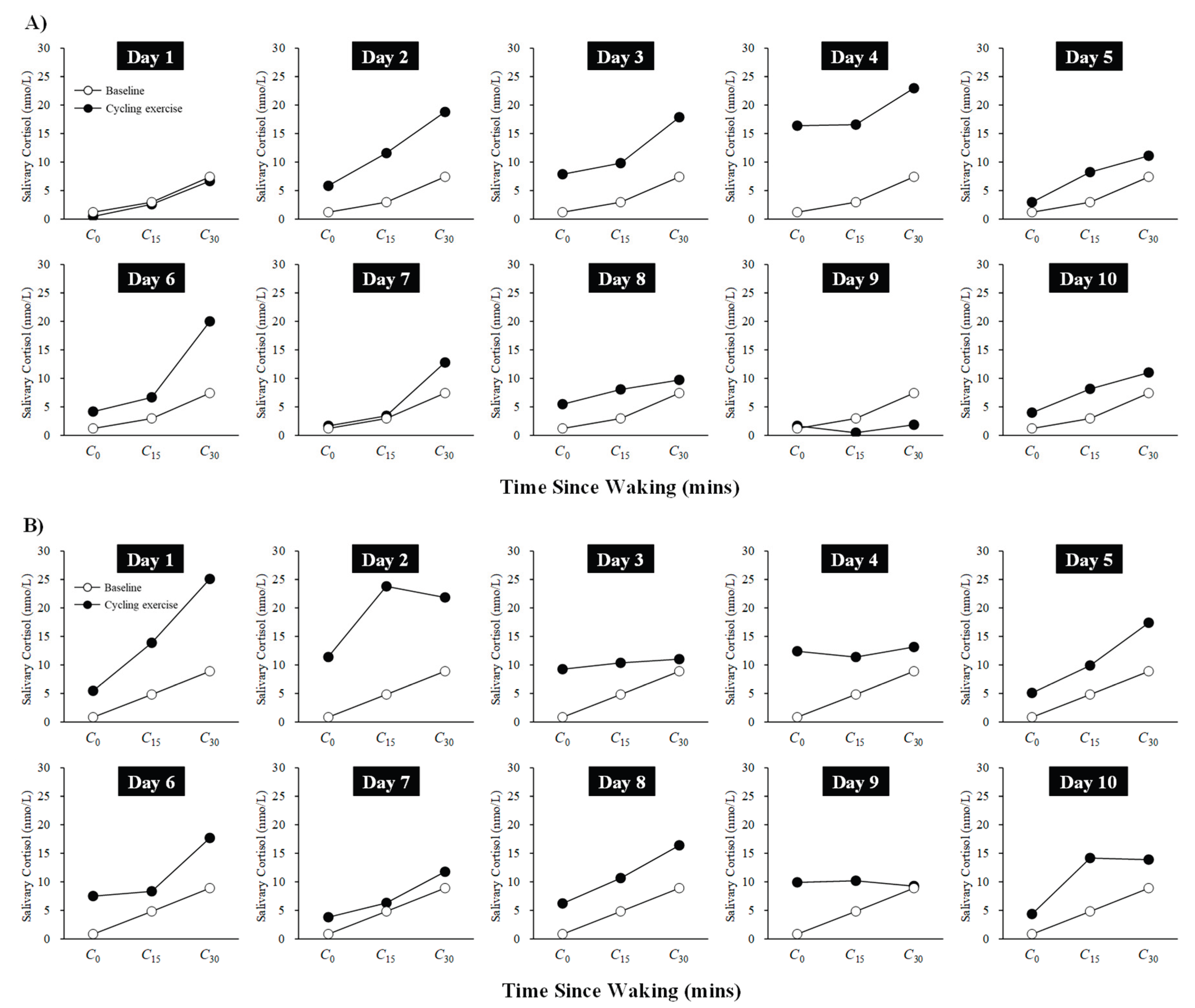

3.3. CAR Data

Figure 2 shows the changes in CAR from baseline for Participants A and B during the 10-day cycling exercise session period. Participant A exhibited an increase in CAR during Days 1–4, followed by a tendency to return to baseline levels from Day 5 onward. Participant B showed a rise in CAR during Days 1–2, with a similar tendency to return to baseline levels from Day 3 onward. Taken together, these results suggest that both participants experienced a transient increase in CAR during the initial phase of the cycling exercise sessions (Days 1–4).

3.4. Aerobic Capacity and Work Performance

Table 2 presents the VO₂max and maximal workload values for Participants A and B before and after the 12-day experimental session intervention. Participant A showed a 5.87% increase in VO₂max, along with a 30 W improvement in maximal workload. Participant B exhibited a 3.3% decrease in VO₂max, but also demonstrated a 30 W increase in maximal workload. In summary, both participants showed improvements in aerobic capacity and/or work performance following the intervention.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to experimentally investigate changes in CAR during a 10-day period of consecutive high-intensity cycling exercise at the fixed workload, and to explore the potential of CAR as a non-invasive biomarker for monitoring short-term physiological adaptations to exercise. The main findings of this study were: (1) acute responses in HR, VO₂, RPE, and cortisol were highest during the initial phase of the cycling sessions (Days 1–4), with subsequent reductions observed thereafter; (2) CAR showed a transient increase during Days 1–4, followed by a return to baseline levels; and (3) both participants demonstrated improvements in maximal oxygen uptake and/or maximal workload following the intervention. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to experimentally demonstrate changes in CAR in response to short-term consecutive exercise sessions.

The acute responses in HR, VO₂, RPE, and cortisol measured on each session were consistently highest during the initial phase of the cycling exercise sessions for both participants, followed by a decreasing trend thereafter. These results are consistent with previous studies. Spina et al. [

24] reported that 7–10 days of cycling exercise increased mitochondrial enzyme activity in skeletal muscle, leading to a glycogen-sparing effect during exercise at the same workload, which in turn resulted in reductions in RER and HR. Additionally, Viru [

26] suggested that endurance training elevates the exercise intensity threshold required to elicit an acute cortisol response, potentially reducing or eliminating such responses to exercise at the same workload. Furthermore, McMurray and Hackney [

27] reported that acute cortisol responses to exercise are elicited in proportion to the metabolic demands of the exercise performed. Based on these findings, it is plausible that the 10-day high-intensity cycling intervention in the present study enhanced the participants’ endurance capacity and improved the efficiency of energy substrate utilization, thereby reducing the metabolic demands of exercise at the fixed workload. As a result, the relative exercise workload imposed by the fixed workload may have progressively decreased relative to the initial session, thereby leading to the reductions in acute physiological responses observed from Day 5 onward.

Focusing on changes in CAR, results supported the hypothesis, showing a transient increase in both participants on Days 1-4, followed by a return to near baseline levels. The elevation in CAR observed during the early phase of the intervention is consistent with our previous findings [

20] and with other studies [

22], suggesting a transient activation of the HPA axis in response to the onset of high-intensity exercise. Moreover, the recovery of CAR around Day 5 aligns with the inference made by Anderson and Wideman [

19] in their review, indicating that physiological adaptation to the imposed exercise may have led to a reduction in HPA axis reactivity. The occurrence of adaptation around Day 5 is further supported by the observed trends in acute physiological responses and the improvements in VO

2max and/or maximal workload following the cycling exercise intervention, which are also consistent with the approximately 9% increase in VO₂peak reported by Spina et al. [

24]. Despite a decrease in VO₂max in Participant B, an improvement in maximal workload was observed. This seemingly contradictory result may be attributed to enhanced efficiency in energy substrate utilization resulting from continuous cycling exercise.

The primary significance of this study lies in its confirmation of the hypothesis proposed by Anderson and Wideman [

19], regarding changes in CAR following continuous high-intensity exercise. These findings suggest that CAR may serve as a useful non-invasive biomarker for monitoring short-term physiological adaptations to high-intensity exercise. However, many aspects of how exercise influences CAR remain unclear. Although previous studies [

20,

21,

28] and the present study have controlled and quantified exercise conditions and training volume, few physiological indicators beyond salivary and blood cortisol concentrations have been assessed to evaluate the participants’ physical state. Therefore, it is currently difficult to determine precisely what physiological conditions are reflected by exercise-induced changes in CAR. According to a review by Stalder et al. [

29], CAR is thought to contribute to the preparation of the physiological system for daytime activity, potentially involving the synchronization of peripheral clocks related to energy metabolism, immune function, and neurocognitive systems upon awakening. Additionally, previous studies have reported that physiological responses such as reduced muscle glycogen content and muscle damage can persist into the days following high-load exercise [

30,

31]. Taken together, these findings suggest that exercise-induced changes in CAR may play a regulatory role in response to physiological disturbances in peripheral tissues caused by exercise. Future research should incorporate complementary physiological markers to comprehensively assess the peripheral physiological states associated with changes in CAR.

One of the primary limitations of this study is its small sample size, which restricts the generalizability of the findings to broader populations. To address this, future research should involve larger and more diverse samples to evaluate the reproducibility and external validity of the present results. Nevertheless, the current study employed a tightly controlled laboratory-based exercise protocol and implemented a 10-day consecutive intervention while minimizing the influence of extraneous variables. Although certain methodological challenges remain—such as the need for an adequate familiarization period prior to baseline assessments—the data obtained represents a valuable contribution to the field and provides preliminary insights that may inform future investigations.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated changes in CAR during a 10-day period of consecutive high-intensity cycling exercise and demonstrated the potential utility of CAR as a non-invasive biomarker for short-term exercise-induced physiological adaptations. The initial elevations in physiological responses and CAR likely reflect early activation of HPA axis in response to the imposed exercise, while the subsequent reductions may indicate the progression of physiological adaptation. Future research should aim to further clarify the physiological significance and generalizability of CAR as a biomarker by incorporating a broader range of physiological indicators and larger, more diverse samples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.O.; methodology, Y.O., T.S. and H.T.; software, T.S.; validation, Y.O.; formal analysis, Y.O.; investigation, Y.O.; resources, Y.O.; data curation, Y.O.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.O.; writing—review and editing, T.S. and H.T.; visualization, Y.O.; supervision, T.S. and H.T.; project administration, Y.O.; funding acquisition, Y.O. and H.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, grant number JP24K20567.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The procedures used followed the Declaration of Helsinki regarding human experimentation. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Osaka University of Health and Sports Science, Osaka, Japan (protocol code 20-4; date: 14 July 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express the deepest appreciation to all our subjects.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Baggish, A.L.; Wang, F.; Weiner, R.B.; Elinoff, J.M.; Tournoux, F.; Boland, A.; Picard, M.H.; Hutter Jr, A.M.; Wood, M.J. Training-specific changes in cardiac structure and function: A prospective and longitudinal assessment of competitive athletes. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 104(4), 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaburi, R.; Storer, T.W.; Wasserman, K. Mediation of reduced ventilatory response to exercise after endurance training. J. Appl. Physiol. 1987, 63, 1533–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloszy, J.O.; Rennie, M.J.; Hickson, R.C.; Conlee, R.K.; Hagberg, J.M. Physiological consequences of the biochemical adaptations to endurance exercise. Ann. N Y. Acad. Sci. 1977, 301(1), 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennie, M.J.; Wackerhage, H.; Spangenburg, E.E.; Booth, F.W. Control of the size of the human muscle mass. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2004, 66, 799–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkkinen, K. Neuromuscular and hormonal adaptations during strength and power training. A review. A review. J. Sports. Med. Phys. Fitness. 1989, 29(1), 9–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hooper, D.R.; Snyder, A.C.; Hackney, A.C. The Endocrine System in Overtraining. In Endocrinology of Physical Activity and Sport; Hackney, A.C., Constantini, N.W., Eds.; Humana: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, H.; Keizer, H.A. Overtraining in elite athletes. Review and directions for the future. Review and directions for the future. Sports Med. 1988, 6(2), 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, A.C.; Hackney, A.C. The Endocrine System in Overtraining. In Endocrinology of Physical Activity and Sport, 2nd ed.; Constantini, N., Hackney, A.C., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.E.; Zack, E.; Battaglini, C.; Viru, M.; Viru, A.; Hackney, A.C. Exercise and circulating cortisol levels: The intensity threshold effect. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2008, 31, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanBruggen, M.D.; Hackney, A.C.; McMurray, R.G.; Ondrak, K.S. The relationship between serum and salivary cortisol levels in response to different intensities of exercise. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2011, 6(3), 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, M.S.; Copeland, J.L.; Van Helder, W. Influence of exercise duration on post-exercise steroid hormone responses in trained males. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 94, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hough, J.P.; Papacosta, E.; Wraith, E.; Gleeson, M. Plasma and salivary steroid hormone responses of men to high-intensity cycling and resistance exercise. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25(1), 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilios, I.; Pilianidis, T.; Karamouzis, M.; Tokmakidis, S.P. Hormonal responses after various resistance exercise protocols. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35(4), 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellman, L.; Nakada, F.; Curti, J.; Weitzman, E.D.; Kream, J.; Roffwarg, H.; Ellman, S.; Fukushima, D.K.; Gallagher, T.F. Cortisol is secreted episodically by normal man. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1970, 30(4), 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, C.J.; Hill, N.; Dattani, M.T.; Charmandari, E.; Matthews, D.R.; Hindmarsh, P.C. Deconvolution analysis of 24-h serum cortisol profiles informs the amount and distribution of hydrocortisone replacement therapy. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 2013, 78(3), 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzman, E.D.; Fukushima, D.; Nogeire, C.; Roffwarg, H.; Gallagher, T.F.; Hellman, L. Twenty-four hour pattern of the episodic secretion of cortisol in normal subjects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1971, 33(1), 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruessner, J.C.; Wolf, O.T.; Hellhammer, D.H.; Buske-Kirschbaum, A.; Von Auer, K.; Jobst, S.; Kaspers, F.; Kirschbaum, C. Free cortisol levels after awakening: A reliable biological marker for the assessment of adrenocortical activity. Life Sci. 1997, 61, 2539–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chida, Y.; Steptoe, A. Cortisol awakening response and psychosocial factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol. Psychol. 2009, 80, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.; Wideman, L. Exercise and the cortisol awakening response: A systematic review. Sports Med. Open. 2017, 3(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogasawara, Y.; Kadooka, S.; Tsuchiya, H.; Sugo, T. High cortisol awakening response measured on day following high-intensity exercise. J. Phys. Fit. Sports Med. 2022, 11(2), 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.; Vrshek-Schallhorn, S.; Adams, W.M.; Goldfarb, A.H.; Wideman, L. The effect of acute exercise on the cortisol awakening response. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2023, 123(5), 1027–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minetto, M.A.; Lanfranco, F.; Tibaudi, A.; Baldi, M.; Termine, A.; Ghigo, E. Changes in awakening cortisol response and midnight salivary cortisol are sensitive markers of strenuous training-induced fatigue. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2008, 31(1), 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffey, V.G.; Hawley, J.A. The molecular bases of training adaptation. Sports Med. 2007, 37, 737–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spina, R.J.; Chi, M.M.; Hopkins, M.G.; Nemeth, P.M.; Lowry, O.H.; Holloszy, J.O. Mitochondrial enzymes increase in muscle in response to 7-10 days of cycle exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1996, 80(6), 2250–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, G. Perceived exertion as an indicator of somatic stress. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1970, 2(2), 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viru, A. Plasma hormones and physical exercise. Int. J. Sports Med. 1992, 13(3), 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurray, R.G.; Hackney, A.C. Endocrine Responses to Exercise and Training. In Exercise and Sport Science; Garrett, W.E., Kirkendall, D.T., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, USA, 2000; pp. 135–161. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T.; Lane, A.R.; Hackney, A.C. The Cortisol awakening response: Association with training load in endurance runners. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13(9), 1158–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalder, T.; Oster, H.; Abelson, J.L.; Huthsteiner, K.; Klucken, T.; Clow, A. The cortisol awakening response: regulation and functional significance. Endocr Rev. 2025, 46(1), 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDougall, J.D.; Ward, G.R.; Sutton, J.R. Muscle glycogen repletion after high-intensity intermittent exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1977, 42(2), 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peake, J.M.; Neubauer, O.; Della Gatta, P.A.; Nosaka, K. Muscle damage and inflammation during recovery from exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 122(3), 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).