Introduction

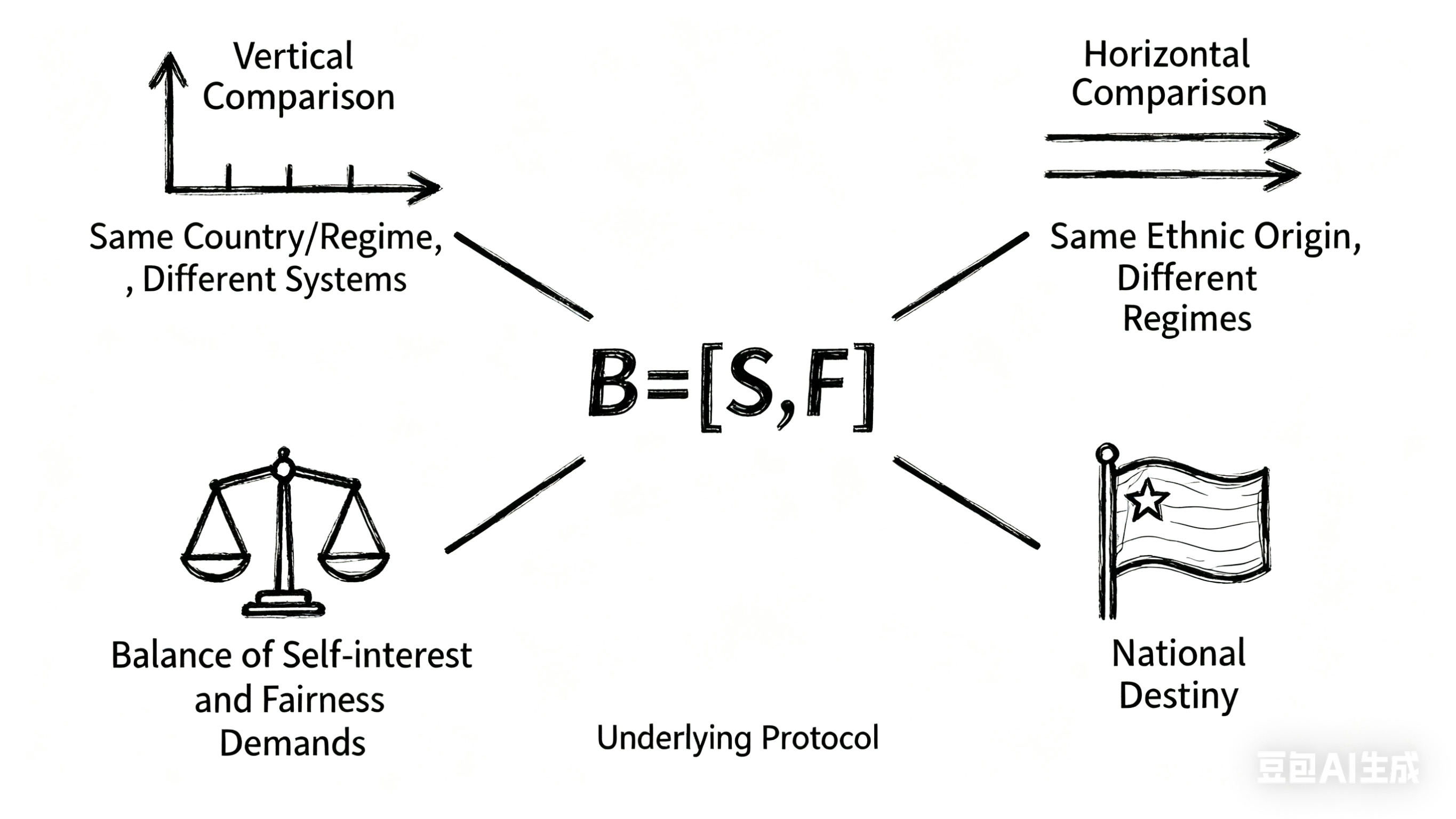

In their book Why Nations Fail, the 2024 Nobel laureates Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson innovatively categorize political and economic institutions into two types: inclusive and extractive. Through methodologies such as "natural experiments" and historical deduction, they conduct in-depth comparisons from a global perspective [

1]. These comparisons include institutional analyses of regions with similar geography and culture. For example, the city of Nogales is divided by a border wall into two parts: one in Arizona, USA, and the other in Sonora, Mexico. Both sides share nearly identical climate, ethnicity, and culture. However, the U.S. side has achieved prosperity due to its inclusive institutions (e.g., rule of law and property rights protection), while the Mexican side has fallen into poverty due to its extractive institutions (e.g., corruption and power monopoly).

After World War II, the Korean Peninsula in Asia was divided into two regimes. They belong to the same ethnic group, share the same language, and have similar geographical conditions. South Korea achieved the "Miracle on the Han River" through inclusive institutions (e.g., democratic elections and a market economy), with a per capita GDP of $36,000 in 2023. In contrast, North Korea has experienced long-term stagnation due to its highly extractive institutions (e.g., hereditary autocracy and a planned economy). When separated brothers reunited 50 years after the war, the elder brother from North Korea—an military doctor within the system—was still wearing a tattered coat, while the younger brother from South Korea had become part of the middle class.

Undoubtedly, the research by these two scholars undoubtedly reveals the importance of institutional design in shaping a nation’s destiny. It successfully refutes theories such as "geographical determinism" and "cultural determinism." For example, China’s economic miracle after the reform and opening-up is the result of breaking away from the planned economy (an extractive system) through market-oriented reforms (inclusive economic institutions). India, through its 1991 economic liberalization reforms, partially broke the constraints of the license raj and achieved an average annual growth rate of over 6%.

Meanwhile, their institutional comparisons provide a key to understanding national inequality. Inclusive economic institutions—characterized by secure property rights protection, barrier-free industry entry, impartial laws and good order, and government support for markets and contract enforcement—align with the institutional conditions required for self-interest and free competition. They facilitate the creation of a fair market environment, allowing citizens from all social strata with different family backgrounds and abilities to participate in economic activities.

"Pluralistic" inclusive political institutions mean that regardless of who is in power, political power is subject to constraints and oversight from different groups and in various forms, including fair elections, civil organizations, and free media [

3]. This ensures that power does not become private property or a tool for certain groups to exploit the public, aligning with the need for checks and balances on power to enable fair competition and cooperation among the people.

A minor limitation is that while their research integrates interdisciplinary perspectives from economics, political science, and history, it does not address the deeper psychological trade-offs and behavioral tendencies in social interactions.

In fact, interdisciplinary evidence shows that in social interactions, self-interest and fairness are inherently antagonistic "psychological dyads" [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. As a special variable, power forms the framework of social interactions through institutions and organizations. Whether power, along with its supporting institutions and organizations, adheres to the "underlying agreements" formed over millions of years of evolution is the internal factor influencing a nation’s prosperity and long-term survival [

9]. This can be easily observed in the evolutionary processes of some remaining Soviet-style regimes, as well as in comparisons between different systems within the same ethnic group.

Vertical Comparison: Contrasts Before and After Institutional Corrections in the Same Country

In the late 20th century, countries that had experienced hardships or setbacks—including China (where both the 1982 Constitution and the 2020 Civil Code added provisions for protecting private property, though official documents often refer to private-sector entities as "private enterprises" to avoid using the term "private"), Vietnam, Cuba, and Laos—continued to identify themselves as socialist countries but were compelled to implement institutional corrections to varying degrees. These adjustments partially restored the balance between the people’s needs for self-interest and fairness. After relaxing controls over private property and personal freedom, all these countries achieved varying degrees of economic improvement.

For example, Cuba has introduced a series of reform measures since 1993, such as easing policy restrictions on individual businesses and implementing supporting reforms. However, the authorities have failed to fully embrace a market economy, citing concerns that it could foster money worship and egoism. Coupled with sanctions imposed by the U.S. government, its overall improvement has been relatively slow. Since Laos launched its "Renovation and Opening-up" policy in 1986, its poverty rate has dropped from 48% of the total population in 1990 to 25.6% in 2010. It was once recognized by the United Nations as one of the three developing countries that performed well in meeting the poverty reduction "Millennium Development Goals." During the "Sixth Five-Year Plan" period (2006-2010), Laos achieved an average annual economic growth rate of 7.9% [

10].

In contrast, China and Vietnam have made more in-depth explorations in restoring the need for self-interest, with particularly striking contrasts between their situations before and after these efforts.

China's Rebirth After the Calamity

After winning the three-year civil war, the Communist Party of China convened the First Plenary Session of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference in Peiping (now Beijing) in September 1949, proclaiming the founding of the People's Republic of China. By 2010, China's gross domestic product (GDP) had surpassed that of Japan, making it the world's second-largest economy [

11]. Over these approximately 60 years, with the decision to launch the reform and opening-up policy at the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in December 1978 as a watershed, China has transformed from a "land of extreme poverty" to an "impressive and powerful nation." The lives of the "first 30 years" and "latter 30 years" after the founding of the People's Republic of China are vastly different, and Chinese people who experienced this period firsthand all feel as if they have stepped into a completely different world.

Xiaogang Village, an otherwise insignificant village at a turning point in the era, is located in Xiaoxihe Town, Fengyang County, Anhui Province, China. It is one of the birthplaces of China's institutional correction and the restoration of private rights. On the night of November 24, 1978, 18 impoverished farmers, in a manner of "entrusting their children to others," took enormous risks, signed a life-and-death agreement, and concluded a land contracting responsibility document to implement the household contract responsibility system (also known as the "household-based output quota system") [

12].

The life-and-death agreement stated: "We divide the farmland among households, and each household head signs and affixes a seal hereunto. If we can make this work in the future, each household shall ensure the fulfillment of its annual state quota and public grain contributions, and shall no longer ask the state for money or grain. If this fails, we, the cadres, are willing to go to prison or even face execution, and all commune members here also guarantee to raise our children until they reach the age of 18" [

13a].

What has forced these grassroots farmers to such an extent? Eliminate the erroneous theory of private ownership and the arrogant rather than rational bureaucratic system.During the era of Mao ZeDong, the egalitarianism that disregarded personal desires and competition resulted in absolute poverty.In 1976, Hua Guofeng succeeded to the throne and adhered to the "two whatevers" - "we firmly uphold all decisions made by Chairman Mao, and we unwaveringly follow all instructions of Chairman Mao". He continued to cut off the so-called "capitalist tail" and did not even allow families to raise chickens, ducks, or geese.

In November 1977, Wan Li, newly appointed Secretary of the Anhui Provincial Committee of the Communist Party of China, made a special inspection tour to Jinzhai County. To avoid fake scenarios arranged by lower-level officials—a long-standing practice in Chinese bureaucracy where subordinates prepare specific routes or even fabricated scenes for superior inspections, driven by both authoritarian systemic pressures and individual or collective interest calculations—he discarded the route arranged by the Lu'an Municipal Party Committee and independently entered a peasant household. The house was extremely poor, with earthen walls and windows, no decent furniture, and a ragged middle-aged woman sitting in the center. Upon inquiry, he learned that she had a family of five: herself, her husband (who was out working), and three children. When Wan Li asked to see the three children, the woman looked embarrassed. Puzzled, Wan Li urged her repeatedly, and finally, the woman had no choice but to walk to the cooking stove and lift the lid. It turned out that the three children had no warm clothes to wear, and the stove still retained heat after cooking, so they were all huddled in the stove to keep warm. Wan Li visited several other households, and almost all were in similar situations. In Dingyuan County, he entered a thatched hut and saw tattered reeds spread on the bed, rotten cotton wadding as bedding, and a single rope holding all the family's clothes. The food in the pot was a black, foul-smelling mixture of sweet potatoes and carrot tops. Along the railway lines in Fengyang County, known as the hometown of flower drum folk art, Wan Li witnessed groups of disheveled peasants, leading their children, scrambling to climb onto trains to beg in other places [

13b].

The villagers of Xiaogang in Fengyang County were no exception. Yan Hongchang, the village head, had long made a living by begging. Both he and the villagers realized that the "egalitarian communal dining system" was the root cause of the village's extreme poverty and hunger. The year 1978 marked a turning point. Facing an almost total crop failure, 18 farmers in Xiaogang Village, in a state of nervousness, pressed their fingerprints on a document in a dilapidated thatched house, dividing the village's farmland among individual households. Ironically, just one year after the implementation of the "Household Contract Responsibility System," Xiaogang Village achieved a bumper harvest and crossed the "subsistence line" [

14]. In 1979, the total grain output of Xiaogang Village reached 66,000 kilograms, equivalent to the total grain output from 1966 to 1970, and the total oilseed output reached 17,500 kilograms, which was the sum of the output over the previous more than 20 years [

15]).

The contrast in grain output and subsistence levels in Xiaogang Village before and after the "Household Contract Responsibility System" revealed the absurdity of ignoring the self-interest demands of the people. Subsequent reform and opening-up in China, from agriculture to industry and from rural to urban areas, were essentially based on the needs of the people's self-interest and competition, correcting the erroneous systems and policies of the Mao Zedong era.

The "domestic reform" adopted a mixed property rights model. In agriculture, the Household Contract Responsibility System (commonly known as the "Household Contract System") was implemented. In industry and commerce, privately-run enterprises with independent operation were allowed to be established (the term "private-owned" is still avoided to this day). Foreign investment was encouraged and attracted, and market economy principles were introduced in two phases. The people's property rights, right of migration, and right of occupation choice were "tacitly approved" or improved.

Phase One (Late 1970s to Mid-1980s),The improvement measures included: abolishing the agricultural collective system and implementing the rural Household Contract Responsibility System, endowing farmers with land contractual management rights and allowing farmers to have the right to dispose of the output from the land; opening the local market to foreign capital and permitting people to establish enterprises. The 1982 Constitution explicitly stated for the first time that "the individual economy is a supplement to the socialist public-owned economy," granting legal status to individual operators. The 1986 Interim Provisions on the Implementation of Labor Contract System in State-Owned Enterprises ended the "iron rice bowl" system, allowing two-way selection between workers and enterprises. However, in the early stage, mobility was still restricted by household registration and unit approval, and peasants still needed temporary residence permits to work in cities. Most industries were still controlled by power.

Phase Two (Late 1980s to 1990s),The improvement measures included: abolishing the agricultural collective system and implementing the rural Household Contract Responsibility System, endowing farmers with land contractual management rights and allowing farmers to have the right to dispose of the output from the land; opening the local market to foreign capital and permitting people to establish enterprises. The 1982 Constitution explicitly stated for the first time that "the individual economy is a supplement to the socialist public-owned economy," granting legal status to individual operators. The 1986 Interim Provisions on the Implementation of Labor Contract System in State-Owned Enterprises ended the "iron rice bowl" system, allowing two-way selection between workers and enterprises. However, in the early stage, mobility was still restricted by household registration and unit approval, and peasants still needed temporary residence permits to work in cities. Most industries were still controlled by power.

Phase Two (Late 1980s to 1990s). The improvement policies included land system reform, the restructuring of state-owned enterprises (including partial privatization and contracting systems), the government no longer controlling commodity prices, and the abolition of some protectionist policies. During this period, the 1988 Constitutional Amendment recognized the legality of the private economy and allowed individuals to accumulate private property through business operations. The Land Administration Law permitted the paid transfer of the right to use state-owned land, laying the foundation for the expansion of private property rights.

In 1992, during his "Southern Tour Speeches," Deng Xiaoping emphasized: "Guard against the Right deviation, but more importantly, guard against the Left deviation" and "The market economy is neither capitalist nor socialist." Since then, the Communist Party of China has no longer mentioned "bourgeois liberalization." Guided by the "cat theory"—"It doesn't matter whether a cat is black or white; as long as it catches mice, it's a good cat"—it broke free from the entanglement of dogmatic socialist theorists and began to focus on the market economy, conducting comprehensive and in-depth reforms in the economic, political, and cultural fields [

16].

After joining the WTO in 2001, the pace of improvement accelerated: the 2001 Passport Law simplified the approval procedures for citizens' private overseas travel; the 2004 Constitutional Amendment explicitly stated that citizens' legal private property shall not be infringed upon, writing the protection of private property rights into the Constitution for the first time; the 2007 Property Law clarified that individuals have the rights to possess, use, benefit from, and dispose of their legal property, and established a unified real estate registration system. In 2019, the "nationwide application" policy for ordinary passports was implemented, making the free movement of people more convenient. The 2020 Civil Code integrated provisions on property rights, contracts, personality rights, etc., systematically protecting private property rights and clarifying the "equal protection of the property rights of various market entities." In particular, it established personality rights (including the right to privacy) as an independent chapter for the first time, highlighting the protection of citizens' personal dignity and rights (Article 1032: clarifies the definition of the right to privacy, including the protection of private life tranquility, private spaces, private activities, and private information. Article 1033: lists specific acts that infringe upon the right to privacy, such as entering others' private spaces without consent, photographing others' private activities, etc., and stipulates the methods of assuming tort liability) [

17].

In the process of recognizing private rights, the gap between urban and rural areas has gradually narrowed, and the guarantee of fairness has improved. For example, the 1986 Compulsory Education Law guarantees citizens' right to basic education and promotes the equalization of the right to education; the 1992 Law on the Protection of Women's Rights and Interests systematically stipulates women's equal rights in employment and property inheritance for the first time; the 1996 revision of the Criminal Procedure Law established the principle of "presumption of innocence" and restricted extortion of confessions by torture, and the 2012 revision added the exclusionary rule of illegal evidence; the 2008 revision of the Law on the Protection of Persons with Disabilities emphasizes the construction of barrier-free environments and anti-discrimination clauses; the basic medical insurance for urban employees (1998), the new rural cooperative medical system (2003), and the basic medical insurance for urban residents (2007) were established gradually, forming a preliminary universal medical insurance system. Although under the post-family-property-era bureaucracy, there are entrenched power self-interest and abuse of public power, and the legal system still acts like a "rubber stamp" in many cases, improvements have been made after all.

It is precisely because of the above series of "corrections" that the people's desire for private ownership and competition has been partially satisfied, which has activated the long-suppressed motivation for wealth creation among hundreds of millions of people and released huge market vitality. With the support of joining the WTO, China has rapidly grown into the "world's factory" and a major manufacturing country. According to data released by the Cabinet Office of Japan, in 2010, China's nominal GDP reached 5.8791 trillion US dollars, surpassing Japan's 5.4742 trillion US dollars, becoming the world's second-largest economy and achieving a historic leap in total economic output [

18].

Vietnam's Đổi Mới (Renovation and Reconstruction)

With a population of over 100 million, Vietnam shares contiguous borders, geographical proximity, historical and cultural similarities, and numerous commonalities with China. On August 15, 1945, after Japan announced its unconditional surrender, Ho Chi Minh launched the August Revolution and established the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. The northern part of Vietnam gained independence and adopted a "Soviet-style" economic model, which prohibited private ownership and free competition. Relying on the "Soviet-style" regime, it enforced collectivization and public ownership. To promote "land reform," from 1951 to 1953, the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) first modeled its approach on China’s "Yan’an Rectification Movement" to conduct ideological indoctrination of cadres and party members, unify their thinking, and require them to fully disclose their private lives and social relationships to the organization, achieving complete obedience.

The guideline of the land reform movement was to fully rely on poor peasant laborers, unite middle peasants, ally with rich peasants, and overthrow landlords. During the land reform period from 1953 to 1956, cadres were first dispatched to the masses to identify poor and tenant peasants. They sought to convince these peasants that their poverty and misery were not predestined, but caused by the oppression and exploitation of landlords, and mobilized them to unite to overthrow the landlords. Peasants who accepted this agitation were called "roots," and they in turn persuaded other peasants [

19].

When most peasants in a village had received ideological education, they were labeled with different class identities:

Poor peasants and agricultural laborers: Lacked sufficient land and capital, and had to rent land, borrow grain, or work as tenants for wealthier neighbors.

Middle peasants: Essentially self-sufficient small-scale farmers.

Rich peasants: Possessed sufficient land and capital, usually hiring laborers to help with farming. They sometimes rented out land but could not entirely avoid manual labor.

Landlords: Wealthy and did not need to engage in heavy physical labor.

In most villages, over half of the households were labeled as poor peasants or agricultural laborers.

In theory, the policy was to confiscate landlords’ land and part of their property, redistribute it to tenant peasants, poor peasants, and some middle peasants. At the same time, landlords were allowed to retain as much land as tenant farmers and keep their houses and most other property. In practice, however, landlords were left with even less land, and their homes were often seized [

20].

On the surface, the land reform aimed to abolish landlord ownership, redistribute land to small-scale farmers, and pave the way for the transition to cooperative agriculture. Nevertheless, the Workers’ Party of Vietnam (later renamed the Communist Party of Vietnam) adopted extremely harsh measures against landlords, including executions, live burials, and other extreme methods. Nguyễn Thị Năm from Thái Nguyên Province in northern Vietnam was executed on charges of being a landlord, becoming the first "sacrifice" of the land reform. Her death was a direct consequence of the CPV Political Bureau’s "May 4th Directive" on land reform in 1953—a document whose first article stipulated: "In this movement, we must execute a certain number of reactionary and despotic landlords. Under current circumstances, the number of landlords to be executed should be set at one per thousand of the total population in the liberated areas" [

21]. Notably, the "May 4th Directive" of the Chinese Communist Party (a key document marking the shift from rent and interest reduction to land reform in 1946) shared the same name. The core of the CPV’s "May 4th Directive" was to execute landlords and mobilize the masses. From 1954 to 1956, rural northern Vietnam experienced a "storm": local land reform committees became de facto local governments, whose main task was to "mobilize the masses." Peasants from several villages were often gathered to hold struggle sessions, denunciation meetings, and public trials, followed by executions. This essentially created social fear, exerting significant psychological deterrence on all people, including onlookers and perpetrators.

Although this radical movement was ostensibly targeted at a small group of landlord elites, tens of thousands of experienced and loyal cadres were accused of having ties to the old order and purged. At the 10th Plenary Session of the CPV Central Committee in 1956, the party acknowledged that approximately 180,000 people had been persecuted as landlords during the land reform, among whom over 120,000 had been misclassified. The official figures were clearly understated, and the exact number of those formally executed or persecuted to death remains unstatistical. Beyond executions, more common practices included various forms of torture, abuse, and humiliation against landlords and their families. After some landlords were executed or imprisoned, their family members and children starved to death. The tragedy was so profound that Ho Chi Minh openly wept at a party meeting [

21].

In 1959, the CPV launched a 16-year-long unification war. In 1975, North and South Vietnam were unified as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Immediately afterward, a movement to "socialize industry and commerce and implement agricultural collectivization" was initiated. The 4th National Congress of the CPV in 1976 decided that socialist transformation in the South would be completed within five years. As a result, public ownership reforms were carried out in key sectors such as industry, transportation, and banking, with many factories and mines nationalized. In rural areas, collectivization was implemented through the establishment of agricultural production cooperatives, which centralized the management of land and agricultural means of production for collective farming. Additionally, in an effort to "eradicate capitalism," a significant portion of the urban population was relocated to harsh "new economic zones." These policies led to widespread factory closures, large-scale farmland abandonment, and a collapse in commerce. The relatively developed capitalist production in Saigon (renamed Ho Chi Minh City in 1976) and its surrounding areas was completely destroyed, and millions of people—including capitalists, intellectuals, and skilled workers—fled abroad.

During the anti-French and anti-American wars, Vietnam received substantial support from China, the Soviet Union, and other countries. However, by rigidly adhering to the Soviet planned economic model, its development path narrowed increasingly. The per capita grain output in northern Vietnam dropped from 360 kg in the 1950s to 250 kg in the 1970s. In 1977, due to Le Duan’s anti-China line, Vietnam’s relations with China deteriorated, leading to a reduction in foreign aid. Nevertheless, Vietnam continued its aggressive military policies, sending troops to Cambodia in 1978, which resulted in international sanctions. Only the Soviet Union provided aid of less than

$2 billion annually, while military expenditures accounted for over 50% of the national budget. After the outbreak of the Sino-Vietnamese border war in 1979, Vietnam’s economy suffered a severe recession: industrial output declined by 4.52% year-on-year in 1979 and a further 8.7% in 1980 compared to 1979. In the 1990s, the Gorbachev regime in the Soviet Union eased relations with the West and also reduced aid to Vietnam. By 1986, Vietnam’s per capita GDP was less than

$200 [

22].

Similar to the resistance of farmers in China’s Xiaogang Village, in the late 1970s, farmers in the Vĩnh Phú region of Haiphong City, Vietnam, spontaneously and secretly implemented a land contracting system as a means of self-rescue. When the practice was discovered, the responsible local cadres were disciplined. However, Trường Chinh, then Chairman of the Council of State of Vietnam, secretly organized an investigation team to conduct a field study and submitted the findings to the Central Committee. After extensive deliberations, in September 1979, at the 6th Plenary Session of the 4th Central Committee, the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) Central Committee officially recognized the spontaneous grassroots reforms represented by Vĩnh Phú Province. Following the session, Vietnam introduced a series of new policies to delegate power and reduce restrictions for farmers, enterprises, and the non-state-owned economy. In January 1981, the Central Secretariat issued Directive No. 100, allowing farmers to contract for agricultural production either individually or in work groups. Nevertheless, there was no consensus within the upper echelons of the CPV. Nguyễn Văn Linh, then Secretary of the Hồ Chí Minh City Party Committee, permitted some enterprises to source production materials from the market and sell their products there after fulfilling state-planned quotas. This corrective attempt was opposed by Lê Duẩn, then General Secretary of the CPV Central Committee, which led to Nguyễn Văn Linh’s removal from the Political Bureau in 1981. Despite this, he persisted in his approach and privately invited Trường Chinh to visit Hồ Chí Minh City for an inspection; Trường Chinh expressed approval of Nguyễn Văn Linh’s practices, leading to Nguyễn’s reinstatement and subsequent promotion. In 1981, the Vietnamese government issued Decision No. 25, granting enterprises partial autonomy in operations. These documents, which only partially addressed the self-interest and competitive needs of agricultural and industrial producers, still managed to stimulate their enthusiasm, and from 1981 to 1985, some key national economic indicators recovered to pre-war levels.

Beyond production-side reforms, Vietnam also experimented with reforms in the circulation and distribution sectors. Long An Province pioneered such explorations, including allowing trade at negotiated prices and abolishing the coupon rationing system. Subsequently, Vietnam implemented a dual-price system in some regions: part of the means of production was purchased at the lower state-subsidized price, while the remainder was bought at market prices, with the price difference covered by state financial subsidies—a mechanism that eventually became unsustainable for the national treasury. In June 1985, the CPV launched a comprehensive "price-wage-currency" linkage reform. For prices, the dual-price system was replaced by a single market price, state-subsidized prices and commodity purchase coupons were abolished, and all commodity prices were re-priced. For wages, a new wage standard was established based on the rice price in August 1985. For currency, the exchange of old currency for new currency began in September 1985. This large-scale reform caused widespread social upheaval: the inflation rate surged to 191% in 1985 and soared further to 775% in 1986, leading to the failure of the "price-wage-currency" linkage reform. The Deputy Prime Minister in charge of the currency reform and other officials were disciplined, including removal from office [

23].

Establishing an unbalanced system may take only a few short years, but correcting its flaws often requires decades, even centuries or millennia—hindered by the constraints of vested interests or influenced by belief perseverance (such as cognitive closure or socio-cultural anchoring) [

24,

25]. Fortunately, humanity has undergone more than three waves of democratic movements for institutional correction, with examples of both successes and lessons readily available.

As Vietnam’s economy descended into chaos, profound changes were taking place in the international landscape. Within the socialist bloc, Poland’s economy continued to deteriorate in the 1980s, leading to a total collapse of public trust in the government. After Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in the Soviet Union in 1985, the country launched "new thinking" diplomacy and political restructuring, moving closer to the West. Hungary and the German Democratic Republic also initiated brief reform processes. China’s reform and opening-up also had a catalytic impact on Vietnam. Outside the socialist sphere, post-WWII Japan had become the world’s second-largest economy; South Korea, Singapore, as well as the Taiwan region and Hong Kong region of China, had emerged as the "Four Asian Tigers"; and other Southeast Asian countries had developed into emerging economies through export-processing models. Such external information continuously penetrated Vietnam’s closed "information well"—a term distinct from "information cocoon," referring to a closed collective space where people are isolated from external information, much like being trapped at the bottom of a well—and stimulated the awareness of some insightful individuals in the country.

Similar to the new life brought about by the death of Mao Zedong in China and Brezhnev in the Soviet Union, the death and replacement of the top leader also brought important opportunities to Vietnam.In July 1986, Lê Duẩn, General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV), passed away. Trường Chinh assumed the position of CPV Central Committee General Secretary and set out to change Lê Duẩn’s political line. In December 1986, the 6th National Congress of the CPV was held. Similar to the role of the 3rd Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, Trường Chinh voluntarily stepped down from the post of General Secretary and promoted Nguyễn Văn Linh to the position. This marked the launch of the comprehensive political and economic renovation and opening-up policy known as Đổi Mới.

Vietnam’s cultural circle differs from those of Eastern European countries. Its inclination toward the abuse of public power for private gain and the privatization of public authority is more aligned with traditional Chinese cultural traits, making it difficult to rectify the structural imbalance rooted in power itself in a single step, as countries like Poland did. Therefore, the initial phase of Đổi Mới (Renovation and Opening-Up) focused solely on economic corrections and the partial restoration of private rights and free competition. During Nguyễn Văn Linh’s administration (1986–1991), a series of major resolutions, decisions, and regulations were issued, such as the Decision on Expanding the Autonomous Management of State-Owned Enterprises, the Foreign Investment Law, the Decision on Distinguishing the Functions of the State Bank and Commercial Banks, and the Resolution on Renovating Agricultural Economic Management. However, due to prolonged wars and propaganda about the planned economy, some people remained skeptical of marketization, leading to significant resistance to the implementation of these policies. For example, in the early stage of promoting the agricultural contracting system, farmers feared policy reversals and hesitated to expand production; the Foreign Investment Law failed to explicitly stipulate intellectual property protection, restricting the transfer of foreign technology; and the lack of synchronized bankruptcy regulations in state-owned enterprise (SOE) reforms hindered the exit of "zombie enterprises" from the market. Although Vietnam’s gross domestic product (GDP) grew at an average annual rate of only 4.4% between 1986 and 1990, its per capita gross national product (GNP) still stood at just

$200 in 1991 [

26].

Faced with severe economic and political challenges, as well as widespread poverty among the people, the Vietnamese government implemented a series of market-oriented reforms between 1991 and 1995. In agriculture, the National Assembly of Vietnam passed legislation in July 1993 stipulating that while "land is owned by the entire people," it would be allocated to farmers for long-term use, with terms ranging from 15 to 50 years. Farmers were allowed to transfer and inherit this land use right, effectively granting them de facto private ownership. In industry, SOEs were pushed into the market, shifting from a mandatory production and sales system to a model of independent operation and self-responsibility for profits and losses, subject to market-driven survival of the fittest. Meanwhile, private enterprises were vigorously developed, with their investment scale expanding continuously—their share in GNP rose from 10% to 45%. In commerce, local governments were ordered to abolish various checkpoints for commodity circulation, and state-mandated pricing was replaced by market-adjusted pricing. By 1993, except for electricity, telecommunications, port transportation, gasoline, chemical fertilizers, and cement (which remained under state pricing), all other commodity prices were liberalized and determined by market forces. In finance, the government permitted the coexistence of multiple banking forms, including state-owned, joint-stock, and joint-venture banks, establishing a diversified financial system led by the central bank and supported by specialized banks for industry and commerce, agriculture, investment, and foreign trade. A relatively flexible exchange rate policy under state management was also adopted. In terms of opening up, Vietnam strengthened ties with the outside world, attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) and boosting export growth. With the deepening of economic reforms, Vietnam’s economy and society took off rapidly: its GDP grew at an average annual rate of 8.2% between 1991 and 1995. Despite the impact of the regional financial crisis from 1996 to 2000, Vietnam still maintained an average annual GDP growth rate of 7.6%. Subsequently, during 2001–2005 and 2006–2010, despite changes in the global economic environment, Vietnam’s average annual GDP growth rates reached 7.34% and 6.32% respectively, consistently ranking among the top in ASEAN. External observers noted that its economic growth was the second highest in the world, only behind China. Even amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Vietnam’s economic growth rate reached 2.58% in 2021, with a per capita GDP of approximately

$3,700 [

27].

With the advancement of Đổi Mới, Vietnam achieved an average annual economic growth rate of approximately 6.67% between 1987 and 2024, ranking among the highest in the region and globally, making it one of the fastest-growing countries in ASEAN. Over nearly four decades, Vietnam’s economic scale expanded nearly 106 times, from

$4.5 billion in 1986 to

$476.3 billion in 2024; its per capita GDP grew from

$74 to

$4,700, an increase of more than 63 times. Starting in 2008, Vietnam officially moved out of the low-income country category [

28]. Su Lin’s "Đổi Mới 2.0" further drove economic recovery: in the second quarter of 2025, Vietnam’s real GDP grew by 8.0% year-on-year, the highest second-quarter growth rate since 2023, outperforming other economies in Southeast Asia [

29].

Shared Roots, Divergent Destinies

In the 20th century, the "Four Asian Tigers"—South Korea, Singapore, as well as China's Taiwan region and Hong Kong Special Administrative Region—all belong to the Sinic cultural circle. The Kuomintang-ruled Taiwan region and the Chinese mainland, as well as democratic South Korea and the Workers' Party-ruled North Korea, share the same ethnicity, consistent customs, and common origins. Their ability to achieve rapid rise and sustained prosperity, becoming developed countries or regions, lies in their dynamic capacity to balance self-interest and fairness. Economically, all of them support private ownership and free competition. Politically, despite differences in systems, they all have a certain degree of checks and balances on power and social justice, leading to vastly different fates for their people. Examples include the following:

Due to historical reasons, Hong Kong (before 1997) had long applied the common law system. When Britain established its overseas colonial system in the 18th and 19th centuries, it exported common law through institutions such as the Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865. The colonial Governor was Hong Kong’s highest administrative officer, wielding absolute executive dominance and also serving concurrently as the President of the Legislative Council to control and influence the legislative mechanism. However, Hong Kong’s judicial power was not fully autonomous: the Court of Final Appeal was located in the British Privy Council, and judges adjudicated cases solely based on law and facts. As a result, a certain check-and-balance relationship existed between the Governor and the courts, and Hong Kong’s private ownership and market economy enjoyed relatively "stable" judicial protection. After the 1950s Korean War, Hong Kong’s re-export trade volume declined due to economic blockades, triggering crises in finance, insurance, and shipping industries. Businesses collapsed in succession, unemployment surged, and social unrest ensued. At this critical juncture, Western industrialized countries began to transfer relatively low-end manufacturing overseas. Hong Kong, a "vanishing city" at the time, seized this opportunity for rise by virtue of its sound legal system and low-cost labor resources, eventually becoming a window for the Communist Party of China’s reform and opening-up [

30].

Singapore, where 74% of the population is of Chinese descent, was also a British colony before gaining independence in 1965. Institutionally, it drew on Britain’s "Westminster system" featuring "parliamentary supremacy" and "responsible cabinet government." Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s first Prime Minister, publicly expressed "gratitude" for British colonial rule, arguing that the rule of law and free trade policies during the colonial period laid the foundation for Singapore’s modernization. Although opposition parties face restrictions on propaganda and assemblies and cannot gain support through large-scale offline activities—resulting in their long-term weakness—and the power transitions from Lee Kuan Yew to Lee Hsien Loong and then to Lawrence Wong were all completed through internal procedures of the People’s Action Party (PAP), drawing criticism for its "one-party dominant democracy," Singapore’s judicial independence is institutionally guaranteed. It achieves limited checks and balances through an elite cabinet, the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB), and the elected President’s budget oversight power, avoiding the disorderly entropy increase where administrative officials act as both "players" and "referees" [

31].

Luck and Struggles of Taiwan

The Kuomintang (KMT) regime that retreated to Taiwan, China in 1949 shares the same historical and cultural background with the Communist Party of China (CPC), is influenced by similar perceptions of power, and both acknowledge the revolutionary achievements of Sun Yat-sen’s democratic republic. However, it differs from the Chinese mainland, which pursued the policy of "eliminating private ownership." In the 1950s, after the Government of the Republic of China relocated to Taiwan, like the CPC-ruled mainland, it faced the task of reconstructing everything from scratch. Nevertheless, it avoided the bloody land reform and a series of political movements involving the abuse of public power that occurred on the mainland. Faced with the situation of a small land area and dense population, the KMT government utilized U.S. aid and introduced a series of policies to support agriculture. Chen Cheng, then Chairman of the Taiwan Provincial Government, implemented the 37.5% Rent Reduction Policy, the Public Land Distribution Program, and the Land-to-the-Tiller Program as part of land reform. Subsequently, it adopted an import substitution policy to support domestic industries and small- and medium-sized enterprises, initiating the development of labor-intensive light industry [

32]. Similar to the mainland’s collectivization, the goal was to pave the way for industrialization. However, Taiwan’s land reform, based on private ownership, more favorably promoted the development of private enterprises and industry and commerce. Three years later, in 1953, Taiwan’s economy gradually recovered to the level before World War II, embarked on a path of rapid growth, and began constructing more large-scale infrastructure projects such as the Shimen Reservoir and the Cross-Island Highway [

33].

While the mainland was mired in movements such as the Anti-Rightist Campaign, the Great Leap Forward, the People’s Commune Movement, and the "Anti-Revisionism and Prevent Revisionism" campaigns—all centered on eliminating private ownership and class struggle—the Taiwan authorities adopted market-oriented approaches and a long-term perspective. They promoted currency reform, land reform, foreign exchange and trade reforms to transform the socio-economic structure. Additionally, they utilized industrial policies, economic liberalization measures, and redistribution policies to lay the groundwork for economic take-off [

34a].

In the 1960s, Taiwan implemented an export expansion policy, using fiscal and taxation measures to encourage exports and investment. These measures included low-interest loans for export sales and export tax rebates for products. Additionally, Taiwan promoted economic liberalization reforms such as a unified exchange rate, currency devaluation, and tariff reduction. During this period, due to rising labor costs, European and American countries gradually outsourced labor-intensive production to Asian countries. Taiwan, with its mature textile industry, low labor costs, saturated domestic market, and overproduction, had the capacity to engage in export processing. To increase exports and earn foreign exchange, the Taiwan authorities established export processing zones near ports to incentivize investment and exports; for example, the Kaohsiung Export Processing Zone, established in 1966, became Asia’s first export processing zone. By 1963, the share of industrial output in the national economy had exceeded that of agriculture, and from then until the First Oil Crisis, Taiwan’s economic growth rate maintained an annual double-digit rate or higher for a long period. In terms of people’s livelihoods, Taiwan emulated the UK’s model of phased regional construction of tap water projects; after the popularization of tap water, "blackfoot disease," a condition related to water sources, gradually disappeared. In 1968, the government implemented a nine-year compulsory education system, which had an epoch-making significance for Taiwan’s society [

33].

The 1970s marked Taiwan’s era of economic take-off. Due to the global economic recession caused by the Oil Crisis, in November 1973, Chiang Ching-kuo—then Premier of the Executive Yuan—launched the well-known "Ten Major Construction Projects" and later the "Twelve Major Construction Projects." These initiatives focused on developing heavy and chemical industries, with investments in steel, shipbuilding, and petrochemical industries, laying a solid foundation for Taiwan’s petrochemical and heavy industries. This period coincided with the Vietnam War, during which the United States placed large orders for supplies from Taiwan, and these factors collectively drove Taiwan’s rapid economic take-off. As a result, Taiwan’s industrial structure shifted from an agriculture and fishery-based economy to one dominated by manufacturing, commerce, and services; Taiwan’s economy developed rapidly, and people’s income and living standards generally improved significantly.

In the 1980s, Taiwan shifted toward technology-intensive industries, developing high-tech sectors such as electronics, mechanical components, and semiconductors. To cultivate talents meeting the needs of the export-oriented economy, the government had earlier established secondary and technical schools and encouraged the establishment of private educational institutions. The large pool of professional talents with university education or above facilitated the rise of high-tech industries from the 1980s onward [

34b].

During the decades when the Chinese mainland was striving to solve the problem of food and clothing, Taiwan, under the governance of the Kuomintang, achieved what was known as the "Taiwan Miracle". It became one of the "Four Asian Tigers" and developed into an emerging industrialized region. According to statistics from the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics of the Executive Yuan of Taiwan, China, the per capita GDP of Taiwan was 153 US dollars in 1961 and increased to 32,756 US dollars in 2023 [

35]. According to the statistics of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), in 2023, the per capita GDP of Taiwan, China, was 33,907.516 US dollars at the international exchange rate and 73,444.248 US dollars in terms of purchasing power parity [

36].

In Taiwan, the Kuomintang economically recognized private ownership and promoted free competition. Politically, although it similarly implemented a "Party state isomorphism" system and self-serving one-party authoritarian rule, with long-term restrictions on civil rights, it maintained the Five-Branch Government system based on the Republic of China's Three Principles of the People. The principle of separation of powers and the democratic electoral system were never entirely abandoned.In 1951, Taiwan began to implement local self-government, and the first general election was held to select county and municipal administrative chiefs—including Wu San-lien, an independent who was elected Mayor of Taipei—county-level and below county-level representatives of the people, and members of the Taiwan Provincial Council.

To consolidate political power and prevent infiltration by the Communist Party of China, on May 19, 1949, Chen Cheng—then Chairman of the Taiwan Provincial Government and concurrently Commander-in-Chief of the Taiwan Provincial Garrison Command of the Republic of China—promulgated the Martial Law Decree for Taiwan Province. It declared the imposition of martial law across the entire Taiwan Province effective from 00:00 on May 20 of the same year (China Standard Time). On July 9, 1949 (the 38th year of the Republic of China era), a comprehensive mutual guarantee system for provincial government employees was implemented; those without a guarantor to vouch for them were denied employment. Originating with government officials, this system gradually expanded to nearly all public and private institutions in Taiwanese society, becoming one of the fundamental political censorship systems affecting the vast majority of Taiwan’s population during the martial law period. On April 3, 1950 (the 39th year of the Republic of China era), the Taiwan Provincial Government further issued the "Organization Measures for Taiwan Anti-Communist and People-Protecting Committees" and ordered all counties and cities to establish such committees within a specified timeframe.

During the martial law period, to facilitate wartime governance, the Kuomintang (KMT) in Taiwan relied on the military and secret police to maintain continuous and tight control over politics and society, consolidating its one-party authoritarian regime. People’s freedoms and basic human rights—including the rights to assembly, association, speech, publication, and travel—were restricted by bans on opposition parties, press censorship, maritime prohibitions, and restrictions on overseas travel. Speech was subject to widespread censorship. In accordance with relevant decrees, the government carried out arrests, military trials, detentions, or executions of members of the Communist Party of China and political dissidents (mostly non-KMT figures). Under the directive of the then-President Chiang Kai-shek, the Taiwan Garrison Command, which was responsible for enforcement, implemented these measures rigorously. Incidents of sudden disappearances were common, and wrongful convictions frequently emerged. This period became known as the "White Terror Period in Taiwan".

According to a report submitted by the Taiwan Garrison Command (then under the jurisdiction of the Kuomintang authorities) to the Legislative Yuan, during the Martial Law period, military courts handled 29,407 political cases, and the official most conservative estimate put the number of innocent victims at approximately 140,000. The Judicial Yuan revealed that there were about 60,000 to 70,000 political cases. Based on an average of 3 people per case, the number of political victims tried by military tribunals should have exceeded 200,000, all of whom were the most direct victims of the Martial Law period. Among these, in 1960 (the 49th year of the Republic of China), the ruling authorities classified 126,875 people as "missing" and revoked their household registrations. Although the scale of this humanitarian disaster was far less severe than that of the various movements in mainland China, it can be inferred that the number of people persecuted to death at that time was extremely high [

37].

Martial Law was originally a product of the Chinese Civil War between the Communist Party of China and the Kuomintang, and it bore the temporary nature of a state of emergency. After the Communist Party of China implemented the "reform and opening up" policy on the mainland, major changes took place in the international Cold War situation starting from the 1980s, and the confrontation between the two parties gradually eased. Non-Kuomintang figures in Taiwan began to demand the complete lifting of Martial Law. Protesting people held high slogans such as "Only Lift Martial Law, No National Security Law" and "100% Lift Martial Law". The movement evolved from early isolated incidents such as the "Five Dragons and One Phoenix Incident" and the "Lei Chen Incident" into a series of organized street movements with ideological goals, such as the "Chungli Incident", "Ciaotou Incident", and "Kaohsiung Incident (Meilidao Incident)". On July 15, 1987, Chiang Ching-kuo, then President of the Republic of China, was forced by domestic and international circumstances to announce the lifting of Martial Law, bringing an end to the 38-year and 56-day "Martial Law period". Subsequently, restrictions on political parties and the press were further lifted, and people were allowed to travel to the mainland for family visits. All these achievements were won through the blood and sweat of the people, and were by no means "benevolent governance" by the Kuomintang's Chiang regime [

38]. In January 1988, Chiang Ching-kuo passed away, and Vice President Lee Teng-hui succeeded him. With the end of the authoritarian rule of the Chiang father-son duo, the process of "purification of power"—including its core dimensions of "de-self-interestedness of power" and "de-privatization of power"—was gradually advanced.

On January 20, 1989, the Legislative Yuan passed the People's Organizations Law in its third reading, allowing the public to register political organizations, as well as legally form parties, associations, and organize participation in rallies and marches.In the 1990s, Taiwan further implemented liberal democracy and political reforms at the central level, and held its first direct presidential election in 1996. Through redistribution and nine-year compulsory education, social stability and equal opportunities are ensured.In March 1995, the national health insurance was officially implemented, and Taiwan's welfare system began to gradually improve. The self-interest and fairness needs of the Taiwanese people have reached a good balance, laying an institutional foundation for maintaining lasting social prosperity [

33].

According to the Democracy Index published annually by The Economist, at the end of the 2000s, mainland China ranked 31st from the bottom among 167 countries/regions, and in 2024, it ranked 22nd from the bottom among 167 countries/regions. Its ranking has declined rather than improved over the past 20 years. In contrast, Taiwan, ranked 36th among 167 countries/regions at the end of the 2000s and rose to 12th in 2024. It has jumped more than 20 places in the recent 20 years, becoming a region with a high level of democracy in Asia [

39]. In 2024, the per capita GDP of mainland China was US

$13,303.1, which was at the world's medium level, while the per capita GDP of Taiwan, China, was US

$33,883, placing it among the world's developed regions [

40].

Divergent Paths Across the 38th Parallel

The choices made by a nation during its founding shape the fate of both its founding team and its people. Both the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) and the Republic of Korea (ROK) on the Korean Peninsula are new regimes established on the basis of a former colony. They share the same ethnic group—the Korean people—and are rooted in common language, culture, and traditional customs.

After Japan’s surrender in World War II in 1945, pursuant to the arrangements of the Yalta Conference, the Korean Peninsula was placed under the joint trusteeship of the United States and the Soviet Union. The United States took control of the southern part of the Peninsula, while the Soviet Union controlled the northern part. In August and September 1948, the two sides respectively established the Government of the Republic of Korea and the Government of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. On July 27, 1953, an armistice agreement was signed, with the two sides demarcated by a demilitarized zone (DMZ) near the 38th parallel north. This marked the beginning of an institutional confrontation that has lasted for nearly 80 years to this day, forming the unique phenomenon of "one nation, two modernities" [

41].

Unlike the collective power entrenchment observed in other Soviet-style regimes, North Korea has evolved into a dynastic system. The so-called "Paektu Bloodline" closely mirrors a medieval patrimonial bureaucracy, demonstrating brutal intra-elite purges—from Kim Il-sung's suppression of the Yan'an, Soviet, and Southern factions in the late 1940s and 1950s, to Kim Jong-un's execution of his uncle Jang Song-thaek, then the regime's second-ranking figure, in December 2013, and the assassination of his half-brother Kim Jong-nam, once considered a potential successor, in February 2017. As a result, the self-interest of the power structure in North Korea is more pronounced, with even less capacity for institutional self-correction, making it difficult to replicate economic reform paths akin to those seen in China or Vietnam.

From 1984 to 1991, pressured by the reduction of Soviet aid, North Korea enacted the Joint Venture Law in 1984 and established the Rajin-Sonbong Economic Special Zone in 1991. It was compelled to emulate China’s reform measures, yet these efforts remained confined to the framework design of attracting foreign investment and failed to address the core contradictions of the planned economy, such as price controls and state-owned enterprise monopolies. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, North Korea, wary of the collapse of the socialist bloc, suspended its reforms and shifted to a conservative course.

From the late 1990s to 2008, after enduring the "Arduous March" (a severe famine), North Korea collaborated with South Korea to establish the Haeju Special Zone and permitted a certain scale of private market activities. Although the informal private markets (jangmadang) alleviated material shortages, they never received official institutional recognition. Policy fluctuations restricted economic vitality. In 2008, reforms were halted once again due to the health crisis of leader Kim Jong-il and the need for a power transition.

After Kim Jong-un took office in 2011, North Korea launched its third attempt at reform. At the 7th Plenary Session of the 7th Central Committee in 2018, it announced a policy of "concentrating all efforts on economic construction" and attempted to engage in dialogue with the United States and South Korea. However, to safeguard the Kim family’s monopolized political power, North Korea has long pursued a "Military-First Policy" (Songun). According to estimates by the South Korean government, the Unha-2 rocket launched in April 2012, along with the Tongchang-ri Launch Site and its carried satellite, cost a total of US

$850 million. If this sum had been used to import corn from China, it could have fed all 19 million North Koreans for one year [

42]. According to reports from the Korean Central News Agency (KCNA), North Korea’s defense expenditures accounted for 15.9% and 15.7% of its total GDP in 2024 and 2025, respectively [

43]. Meanwhile, the Kim-led North Korea regards nuclear weapons possession as a guarantee for its survival, resulting in long-term international sanctions. Economic special zones (such as Sinuiju) have failed to attract effective investment due to external sanctions and internal corruption, and the 2009 currency reform also ended in failure [

44,

45].

Nevertheless, when the North Korean authorities made slight concessions on policies related to the people’s "self-interest demands," productivity was partially liberated. To boost farmers’ enthusiasm and agricultural output, the Kim Jong-il administration, imitating China’s earlier agricultural reforms, introduced a contract system in 2002. This system allowed farmers to own their own land and decide which crops to grow independently [

46], while also raising the procurement prices of agricultural products. Under these extremely limited policy adjustments, North Korea’s grain output increased. In 2004, the country’s grain output jumped to 4 million tons, double that of 1997 [

47]. Additionally, the tacitly approved jangmadang (informal private markets) have become the core channel for the circulation of food and daily necessities in North Korea. A 2021 report by the Korea Institute for National Unification (KINU) stated that approximately 75-85% of North Korea’s food, daily necessities, and light industrial products circulate through private markets, while the supply from state-owned stores covers only about 15% and is concentrated on the privileged class in Pyongyang. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations indirectly confirmed this: North Korea’s grain self-sufficiency rate is less than 60%, and the shortage is supplemented by smuggled grain from China and distribution through private markets, underscoring the pivotal role of these informal markets.

In stark contrast to the fate of the North Korean people, South Korea, located south of the 38th Parallel, recognized private ownership and encouraged competition from its inception, actively developing a market economy. Arable land in South Korea accounts for approximately 16% of its total land area, with per capita arable land of about 0.04 hectares (equivalent to 0.6 mu). This is less than North Korea’s 22% arable land share of its total area and 0.08 hectares (1.2 mu) of per capita arable land. Additionally, North Korea’s per capita forest area is three times that of South Korea, and its mineral resources are among the most abundant in Northeast Asia [

45]. Despite having less arable land and poorer natural resources, South Korea has never experienced a severe five-year famine like North Korea’s. Even in years of poor harvests, it has not faced recurring food shortages.

After Japan's surrender in August 1945, South Korea's economy was also in chaos. Furthermore, the North-South confrontation severed the economic links of the "Northern Industry, Southern Agriculture" pattern that existed during the Japanese occupation, leaving South Korea, located in the southern part of the peninsula, without access to energy, raw materials, and equipment supplies. To address the urgent economic situation, the Syngman Rhee government prioritized agricultural development and implemented an economic policy encouraging import substitution. In March 1950, the government enacted the Agricultural Land Reform Act, launching a rural land ownership reform based on the principle of "land to the tiller," which involved the "compensated expropriation" of land from landowners and its subsequent "compensated distribution" to the actual tillers—farmers. Through this land reform, the Syngman Rhee government abolished the existing tenancy system in South Korean agriculture and established a system of owner-cultivators. The proportion of owner-cultivated land in South Korea’s total agricultural land increased from 35% before the reform to 96%. The Korean War further devastated South Korea’s economy, leaving millions of South Koreans struggling with poverty and unemployment [

48]. To address the food shortage, the Syngman Rhee government consecutively formulated two five-year plans for agricultural development starting from 1953. With the support of these agricultural policies, South Korea’s agriculture recovered more rapidly than other economic sectors, and a major agricultural bumper harvest occurred in 1957-1958 [

49].

In terms of industry, with Soviet support, North Korea once outperformed South Korea in the 1950s and 1960s. For instance, in 1971, North Korea’s per capita energy consumption reached 1,326 kWh, more than double South Korea’s 521 kWh. As late as 1976, North Korea still led South Korea in per capita gross domestic product (GDP) [

46]. However, South Korea soon demonstrated its institutional advantage in balancing the people’s demands for self-interest and fairness. During the Syngman Rhee era, while actively absorbing foreign aid, the government also secured reimbursable foreign investment. In 1959, South Korea absorbed reimbursable foreign investment for the first time to expand the Dongjae Cement Factory, securing a USD 2 million loan from the U.S. Development Loan Fund (DLF) for underdeveloped countries. From 1959 to 1961, South Korea accumulated USD 43.86 billion in foreign investment. After Park Chung-hee took power in 1963, he still prioritized economic development. His slogan—"Treat workers like family; work in factories as if it were your own business"—became a source of spiritual motivation for South Koreans at that time. South Korean workers, with a cost only one-tenth that of American workers, achieved a productivity 2.5 times that of their American counterparts [

49].

From the 1960s to the early 1970s, South Korea focused on developing labor-intensive industries and infrastructure. From the mid-1970s to the 1980s, it shifted to capital-intensive industries such as heavy industry, military industry, and chemical industry. Driven by the "export-oriented" economic strategy, South Korea’s economy grew rapidly, creating the "Miracle on the Han River" [

50]. It gradually surpassed North Korea in per capita GDP and industrial technology, becoming an emerging developed country in East and Southeast Asia after Japan (in line with the Flying Geese Theory) and one of the economic "locomotives" in the region. According to IMF statistics, South Korea’s per capita GDP stood at USD 33,393 in 2023 [

51].

With the rapid development of South Korea’s economy, the share of agriculture in its GDP declined rapidly. In 1970, agriculture accounted for 20.7% of GDP, but by 2004, this proportion had dropped to 4.0%. Between 1970 and 2000, the proportion of the agricultural workforce in South Korea decreased from 50% to 8.5%. South Korean farmers maintained a relatively high income level, with a per capita annual income of USD 13,500 in 2005, and the income ratio between farmers and urban residents was 0.84:1 [

52].

Like North Korea, which lies north of the 38th Parallel, South Korea is a post-WWII established state. However, South Korea has not only become one of the world’s developed countries but also achieved remarkable progress in political democratization and social redistribution.

Politically, South Korea experienced successive authoritarian regimes under Syngman Rhee, Park Chung-hee, and Chun Doo-hwan. The National Assembly endured hardships such as dissolution and the arrest of its members, yet the country gradually rid itself of the tendency toward power self-interest. In 1987, South Korea’s democratization process entered a critical phase: a new constitution institutionally ended the president’s dominant position over the National Assembly, establishing the separation and checks and balances between the executive and legislative branches. On December 19, Roh Tae-woo became South Korea’s first president elected through a fair and transparent process. In 1992, Kim Young-sam was elected as the 14th President of South Korea [

53], marking the beginning of the era of civilian government.

According to the Democracy Index published annually by The Economist, South Korea has generally ranked among the top 25 out of 167 countries since the 2000s. In 2024, its ranking declined due to the emergency measures implemented by the Yoon Suk-yeol administration. In contrast, North Korea has long remained at the bottom of the index since its first publication in 2008 [

39], and the Kim-led North Korea is regarded as one of the countries with the worst human rights records in the world today.

In terms of social welfare, in the 1960s and 1970s, North Korea implemented policies such as "free housing allocation" and "compulsory education," which were once seen as manifestations of the superiority of socialism. However, North Korea’s welfare system is "inefficient" and linked to family background, essentially functioning as a form of loyalty extortion. South Korea, following its economic takeoff, combined marketization with state welfare. In 1988, it revised the National Pension Act and implemented the national pension system for the first time. By 1999, the pension and retirement benefit systems covered all citizens. Health insurance was introduced in 1977, funded primarily by contributors’ premiums, supplemented by state subsidies and other interest income. Employment insurance was launched in 1995. Unlike unemployment insurance, it not only provides relief to the unemployed but also adopts proactive policy measures to prevent unemployment as much as possible. Employment insurance premiums are divided into two categories: unemployment insurance premiums and premiums for employment stability and vocational ability development programs. Unemployment insurance premiums are shared equally by employers and employees, while premiums for employment stability and vocational ability development are borne entirely by employers. Industrial accident insurance was the first widely implemented social insurance scheme, with premiums paid solely by employers. It covers work-related injuries, illnesses, disabilities, and deaths [

54].

Admittedly, justice also needs to be fought for [

55]. Fortunately, like the people in Taiwan, China, the people of South Korea have a constitutional framework of separation of powers, which provides institutional conditions for realizing multi-stakeholder games for mutual benefit and fairness, including workers' movements and democratic movements.

Conclusions

Both the longitudinal comparison of the same country or political regime under different systems and the horizontal comparison of the same ethnic group (sharing common roots) under different political regimes indicate that systems which better respect the people’s demands for self-interest and fairness tend to achieve stronger economic performance. Additionally, lower levels of power self-interest correlate with fewer social conflicts and greater progress in social equity.

This phenomenon is prevalent worldwide. Similar to the aforementioned cases—mainland China and Taiwan as well as North Korea and South Korea—all of which share the same roots and origins, East Germany and West Germany on either side of the Berlin Wall after World War II also experienced stark systemic differences. West Germany’s economic and political systems maintained a dynamic balance between societal self-interest and fairness, as well as competition and cooperation. In contrast, East Germany treated power as an object of operational profit-seeking and a tool for non-transparent operations. It had neither private ownership nor competition, nor did it have fairness to speak of. It was not until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1990 and the reunification of the "twin cities" that the people of East Germany were able to break free from the "fatal conceit" of a planned economy [

56], putting an end to the social ills of isolation, oppression, inefficiency, and destitution. A more extensive range of evidence for this argument is provided by Nobel laureates Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson in their book Why Nations Fail.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge Li Jianjun for his support in providing books and materials, express gratitude to Doubao for translation assistance (the original work was in Chinese), and thank the reviewing editor for taking the time to contribute.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2014). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty (B. C. Deng & G. Q. Wu, Trans.). Wei Cheng Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511794225.

- North, D. C. (1994). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance (S. Y. Liu, Trans.). Shanghai Joint Publishing Company. (ISBN 7542606611).

- Deng, Y. W. (2024, October 22). Nobel Economics Prize winner's advice to China: Without political tolerance, there is no economic future. Voice of America (Yiwen Vision). Retrieved from https://www.voachinese.com/a/political-commentary-by-deng-yuwen-20241022/7832189.html.

- Brosnan, S. F., & de Waal, F. B. M. (2003). Monkeys reject unequal pay. Nature, 425(6955), 297–299. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01963.

- Proctor, D., Williamson, R. A., de Waal, F. B. M., & Brosnan, S. F. (2013). Chimpanzees play the ultimatum game. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(6), 2070–2075. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1220806110. PMID: 23319633; PMC: 3568338.

- de Waal, F. (2011, November). Moral behavior in animals [Video].TEDxPeachtree. https://www.ted.com/talks/frans_de_waal_moral_behavior_in_animals. Retrieved October 16, 2025.

- Brosnan, S. (2020, December). Why monkeys (and humans) are wired for fairness [Video].TEDxPeachtree. https://www.ted.com/talks/sarah_brosnan_why_monkeys_and_humans_are_wired_for_fairness. Retrieved October 16, 2025.

- Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (1992). Cognitive adaptations for social exchange. In J. H. Barkow, L. Cosmides, & J. Tooby (Eds.), The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture (pp. 163–228). Oxford University Press.

- Raphael, X. (2025). Underlying Protocols, Power Variables, and National Destiny: A Causal Analysis. Preprints. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202509.2302.v1.

- Shen, H. F., He, J. M., Lin, M., Fan, H. W., et al. (2014). Industrialization, foreign direct investment and technological progress in Southeast Asia (in Chinese). Xiamen University Press. (ISBN 9787561553602).

- CCTV News. (2011, February 14). Japan's GDP surpassed by China by $405 billion; foreign media say Japan's recovery depends on China (in Chinese). Retrieved from https://big5.cctv.com/gate/big5/jingji.cntv.cn/20110214/106763.shtml.

- Xinhua News Agency. (2014, October 17). Archives of New China's achievements: Household contract responsibility system (in Chinese). Retrieved from https://www.news.cn/politics/2021-10-17/c_1211424568.htm.

- Chen, G. D., & Chuntao. (2009). The story of Xiaogang Village (Chapter 1: Swearing an oath in blood) (in Chinese). Huawen Press. (ISBN 978-7-5075-2836-7).

- Chen, G. D., & Chuntao. (2009, September 22). The girl without adequate clothes inspired Wan Li to take the first step of reform (Excerpted from The Story of Xiaogang Village, Introduction, pp. 4-9) (in Chinese). Phoenix News. Retrieved from https://news.ifeng.com/history/zhongguoxiandaishi/200909/0922_7179_1359186_2.shtml.

- Chen, J. (2018, May 31). 40 turbulent years: "Xiaogang Spirit" and Yan Hongchang (in Chinese). Huanqiu.com. Retrieved from https://finance.huanqiu.com/article/9CaKrnK8UdH.

- Caijing.com. (2018, May 6). Rural reform: "On the field of hope" (in Chinese). Retrieved from https://m.caijing.com.cn/api/show?contentid=4447788.

- Deng, X. P. (2019). Selected works of Deng Xiaoping (Volume III) (in Chinese). Qiushi.com. Retrieved from https://www.qstheory.cn/books/2019-07/31/c_1119485398_119.htm.

- National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China. (2021, August 23). Achievements of China's human rights protection legislation in the 40 years of reform and opening up (in Chinese). Retrieved from http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/c12434/wgggkf40nlfcjgs/202108/t20210823_313158.html.

- CCTV News. (2011, February 14). Japan's GDP surpassed by China by $405 billion; foreign media say Japan's recovery depends on China (in Chinese). Retrieved from https://big5.cctv.com/gate/big5/jingji.cntv.cn/20110214/106763.shtml.

- Chen, F. (1968). Vietnam's land revolution (Haoni, Ed.) (pp. 103-104, 107-108). Nhà Xuất Bản Khoa Học Xã Hội.Supplemental sources: People's Daily (1956, October 7; October 30; November 17).

- Government of Vietnam. (1953, December 4). Land Reform Law (Articles 4 & 25). In L. Châu (Ed.), Vietnamese society: Economic transformation (pp. 393-402). Maspero.

- Cheng, Y. H. (2014, August 26). The tragedy of Nguyễn Thị Năm in Vietnam's land reform (Originally published in Phoenix Weekly). Aisixiang. https://www.aisixiang.com/data/77309.html.

- Liu, J. (2024, November 1). "Renovation" cause: Vietnam's reform and opening up. Economic Observer. (Adapted from W. H. Lian & P. Sherlock, Dragon's Rise: Vietnam's History, 2014).

- Pan, J. E., He, Q., Xun, S. X., & Zhou, M. (2013, December 11). Report on the transformation of socialist countries (Research Group of Marxism Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences). Sichuan Academy of Social Sciences. http://sass.cn/109009/18459.aspx.

- Rocchi, P. (1998). Il bisogno di chiusura cognitiva e la creativita (Need for closure and creativity). Giornale Italiano di Psicologia , XXV , 153–192. https://www.rivisteweb.it/doi/10.1421/190.

- Ann Swidler:Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies,Source: American Sociological Review, Vol. 51, No. 2 (Apr., 1986), pp. 273-286 Published by: American Sociological Association .Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2095521.

- Liu, S. L. (2012, April 23). "Renovation and opening up": How far can Vietnam go? Phoenix News. Retrieved from https://finance.ifeng.com/a/20120423/6331586_0.shtml.

- Luo, Q., & Hai, X. (2022, November 21). A brief analysis of the theory and practice of socialism in Vietnam since the 13th National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam. Yunnan Theory Network. (Original work published in Socialist Forum, 2022, No. 4, "International Perspective").

- Ministry of Commerce of the People's Republic of China. (2025, August 22). Vietnam's economy grows 106 times in 40 years of renovation and opening up (Economic and Commercial News).