3.1. D-LA Production at Different Glucose Levels

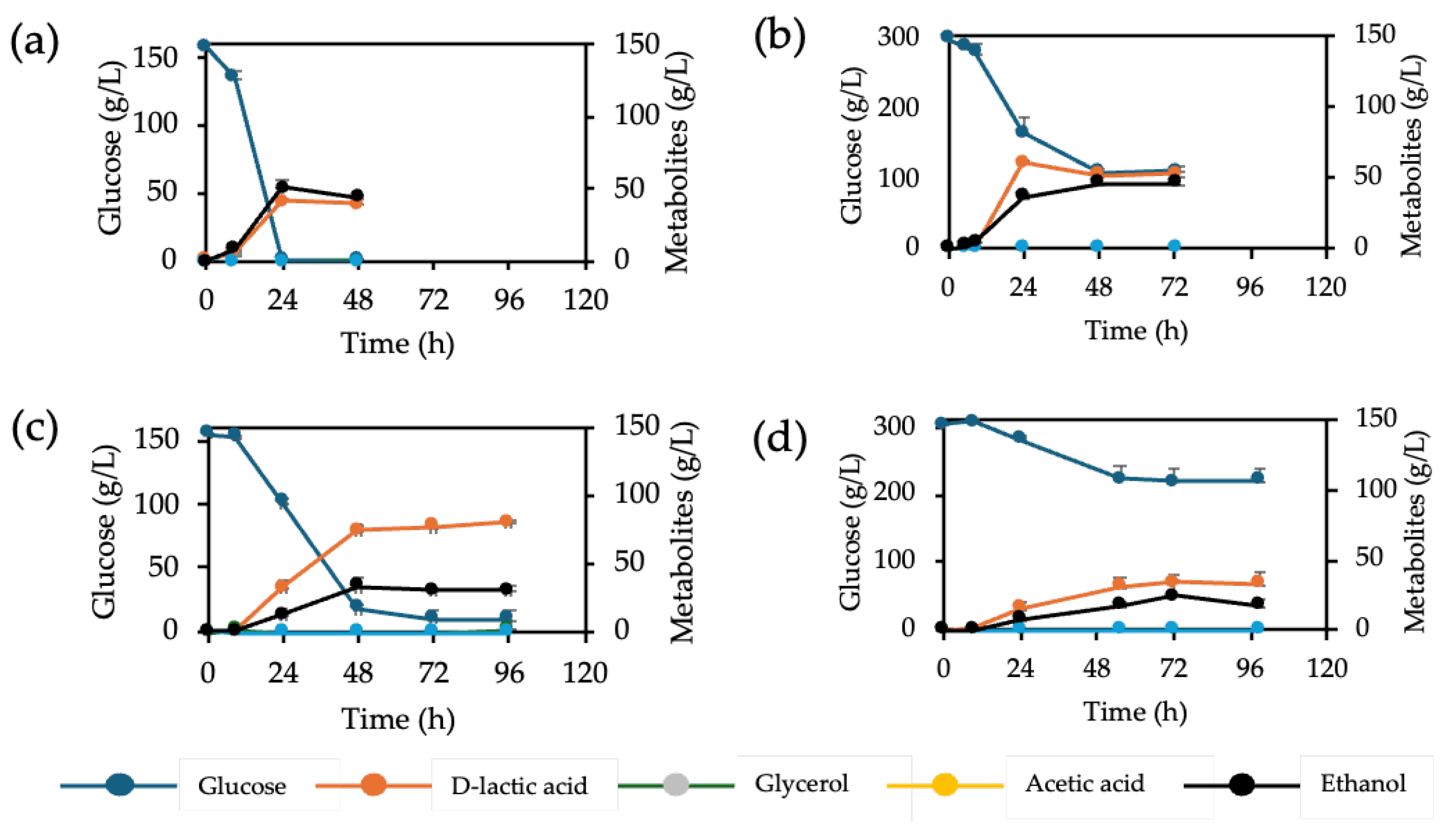

We initially assessed the potential of two genetically modified yeast strains, S. cerevisiae F118Δ

CYB2::LpDLDH and F118ΔP

DC1::LpDLDH, for D-LA (D-LA) production under high glucose levels (150 g/L and 300 g/L). As shown in

Figure 1, at 150 g/L glucose, D-LA production reached 41 g/L for F118Δ

CYB2::LpDLDH and 80 g/L for F118Δ

PDC1::LpDLDH, corresponding to 40% and 53% of the theoretical yield, respectively. Conversely, at 300 g/L glucose, both strains exhibited poor substrate utilization, with F118Δ

CYB2::LpDLDH consuming only about half of the available glucose, and F118Δ

PDC1::LpDLDH consuming even less. These results suggest that very high glucose levels induce significant osmotic and metabolic stress, which limits glucose uptake and fermentation efficiency.

The PDC1-disrupted strain showed increased D-LA yield, likely due to decreased ethanol production and greater carbon flux into pyruvate breakdown. In contrast, the CYB2-disrupted strain produced less D-LA and more ethanol, but was more efficient at consuming glucose, suggesting a greater tolerance to osmotic stress. These results highlight a trade-off between product yield and physiological resilience, which is strongly influenced by the location of the

LpDLDH expression cassette. To explore this further, both strains were tested across a broader range of glucose levels (50–150 g/L) to assess their tolerance to increasing osmotic stress [

16].

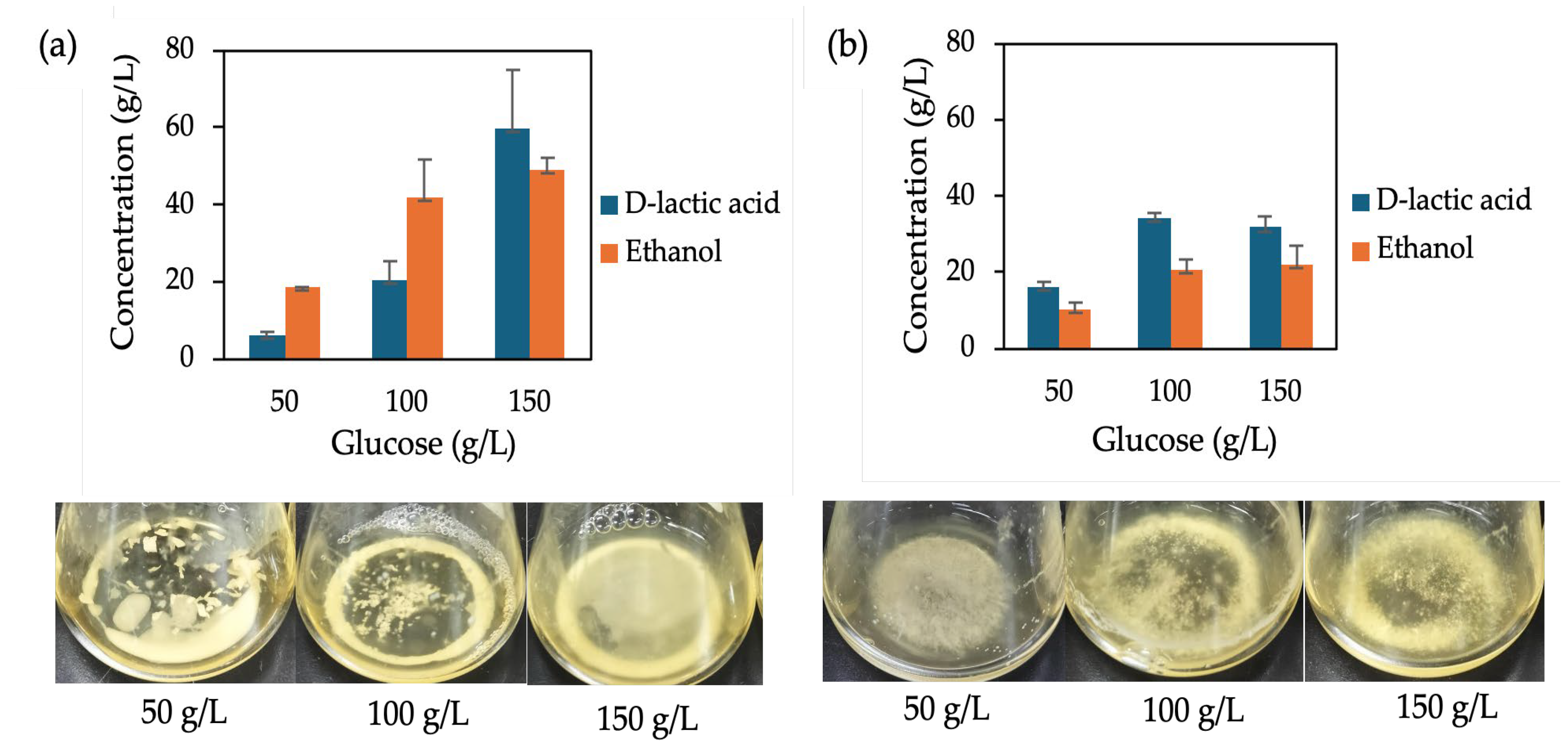

At moderate glucose levels, the F118Δ

CYB2::LpDLDH strain showed a significant increase in D-LA productivity (

Figure 2a). The D-LA yield nearly doubled as glucose increased from 50 g/L to 150 g/L, demonstrating that this strain can tolerate osmotic stress up to 150 g/L without major growth inhibition. In contrast, the F118Δ

PDC1::LpDLDH strain had lower efficiency, producing only 31.81 g/L D-LA with a 39% yield under 150 g/L glucose conditions (

Figure 2b), which is much lower than the 80 g/L observed in the previous batch at the same sugar level. Therefore, subsequent gene expression studies focused on the more resilient F118Δ

CYB2::LpDLDH strain.

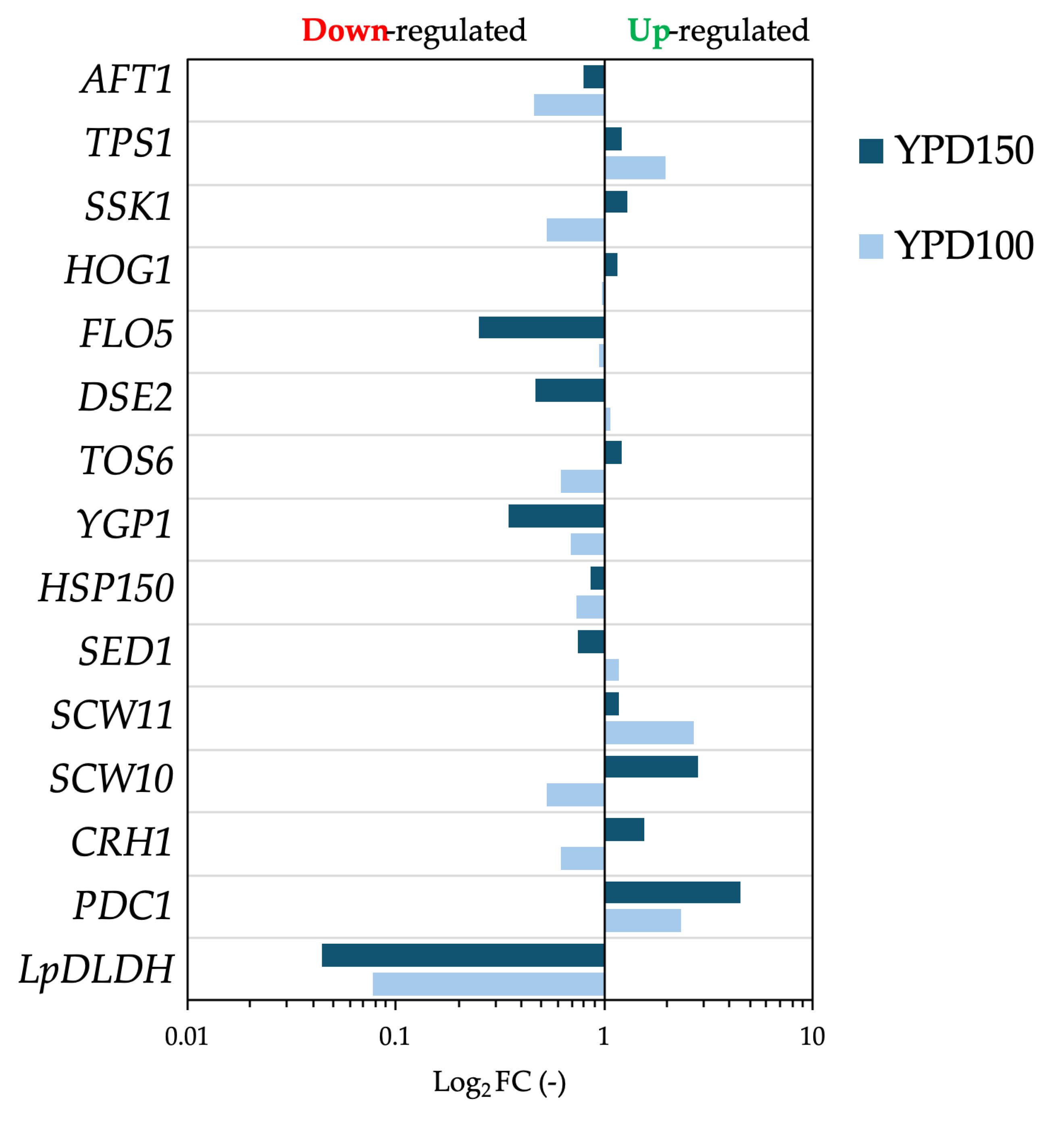

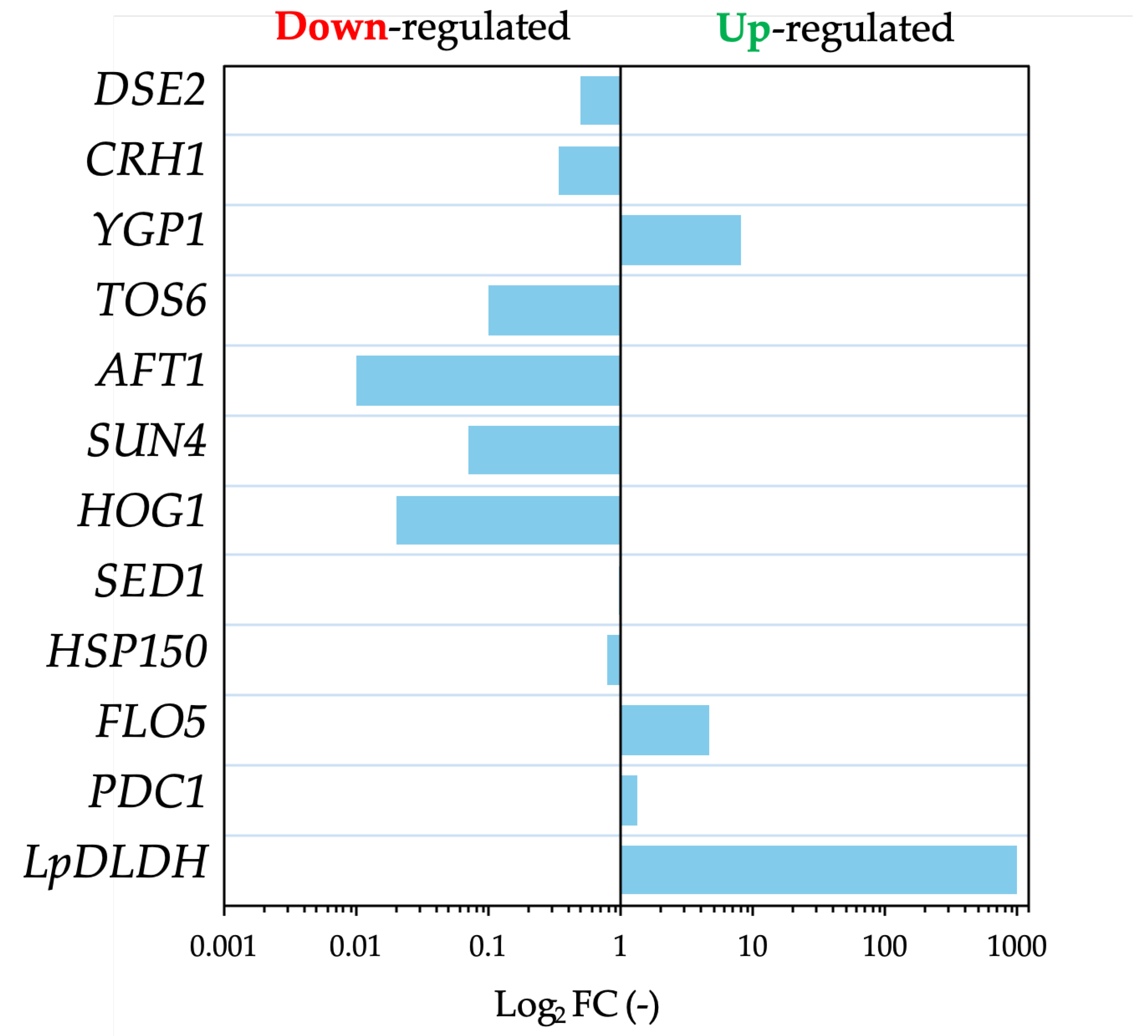

To identify genes responding to high-glucose stress, quantitative PCR was performed during fermentation, focusing on pathways involved in lactate production, ethanol metabolism, and stress adaptation. The genes examined included those involved in lactate formation (

LpDLDH), ethanol synthesis (

PDC1), cell-wall remodelling (C

RH1, SCW10, SCW11, DSE2), cell-wall integrity and resistance (

SED1, HSP150, YGP1, TOS6), flocculation (

FLO5), osmotic-stress regulation (

HOG1, SSK1), stress protection (

TPS1), and iron homeostasis (

AFT1). As shown in

Figure 3, the transcriptional profiles demonstrated significant upregulation of stress-related genes at higher glucose concentrations. The

TPS1 gene, which controls trehalose synthesis and overall stress resistance, was activated under both 100 g/L and 150 g/L glucose conditions. At the same time,

HOG1, a key kinase in the high-osmolarity glycerol (HOG) pathway, was upregulated only at 150 g/L. Similarly, cell-wall remodelling genes

CRH1 and

SCW10 increased at 150 g/L, indicating reinforcement of cell-wall strength under osmotic stress. These responses correlated with decreased culture turbidity at high-glucose levels (

Figure 2a), suggesting reduced flocculation and cell aggregation.

In contrast, the F118Δ

PDC1::LpDLDH strain, which has reduced flocculation due to the downregulation of

FLO5 [

13], showed no noticeable change in aggregation as glucose concentrations increased. This supports a mechanistic link between flocculation behavior and osmotic-stress tolerance. Measurements of dry-cell weight across the three glucose levels showed no significant differences (

Supplementary Figure S1), indicating that the variations in D-LA production are mainly metabolic rather than growth-related. Although the study examined a limited set of genes, these results establish an initial connection between metabolic output and stress-response regulation under high-glucose conditions. The upregulation of HOG1, TPS1, and cell-wall genes suggests that osmotic stress triggers adaptive responses that may improve flocculation stability and D-LA productivity in the robust F118ΔCYB2::LpDLDH strain. Future research should expand these findings by conducting transcriptome-wide analyses, targeted overexpression of protective genes, and adaptive evolution experiments to further enhance osmotic tolerance and D-LA production. Combining these strategies with rational genetic design will be key to optimizing yeast cell factories for lignocellulosic bioprocesses [

16].

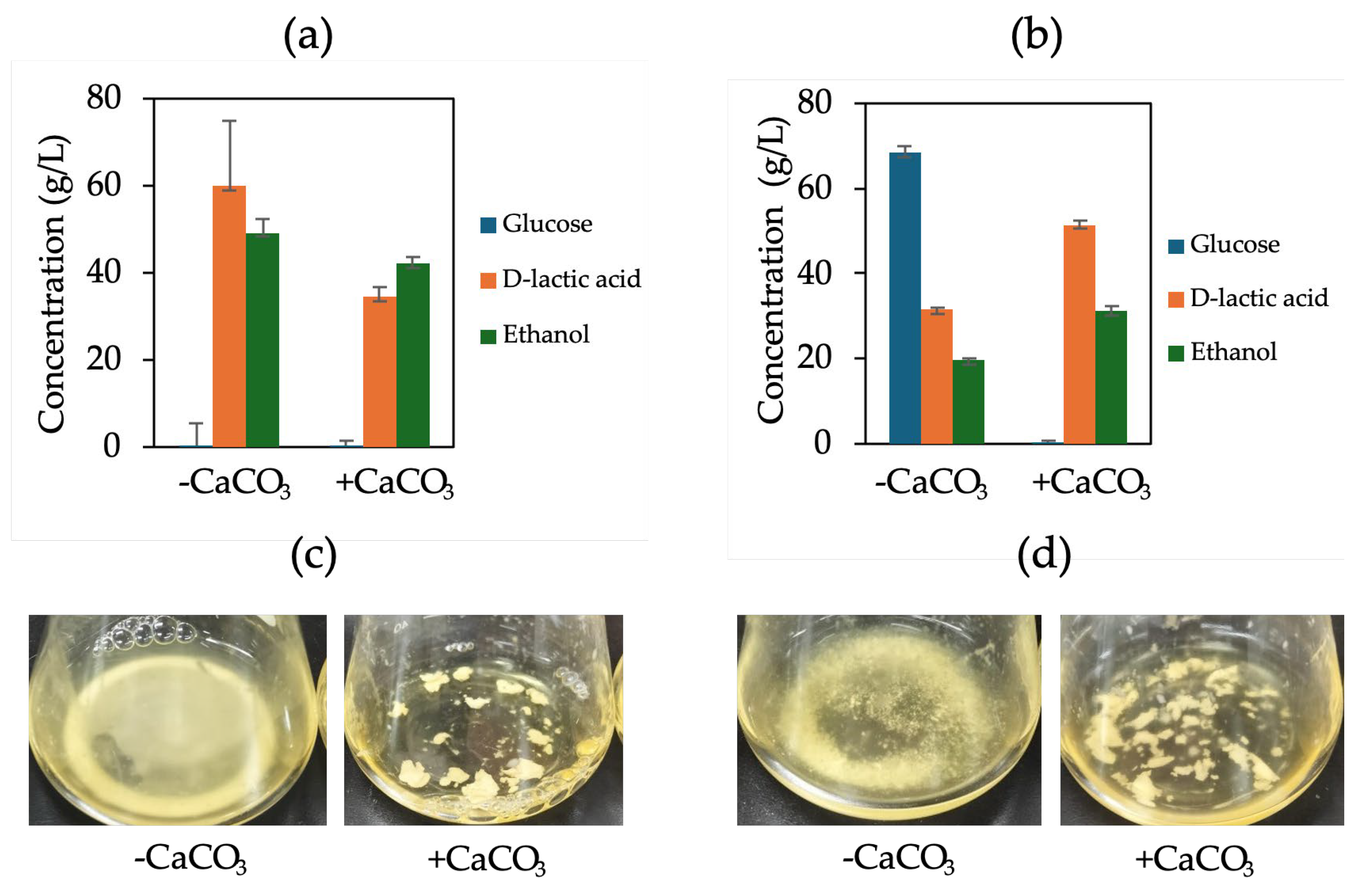

3.2. Calcium Carbonate Supplementation Effect on D-LA Production

To reduce the growth inhibition observed in S. cerevisiae F118∆

PDC1::LpDLDH, caused by

LpDLDH disruption that limits ethanol production and cell growth [

13], CaCO₃ was added at the start of fermentation as a neutralizer. In industrial D-LA production, adding excess CaCO₃ is a common method to prevent the pH from dropping too much during lactic acid buildup. During fermentation, CaCO₃ reacts with lactic acid to produce calcium lactate and carbonic acid, which then breaks down into water and carbon dioxide. This buffering reaction keeps the fermentation broth around pH 5.0, providing a more stable environment for yeast metabolism. CaCO₃ addition maintained a slightly higher final pH in both strains (

Supplementary Figures S2 and S3).

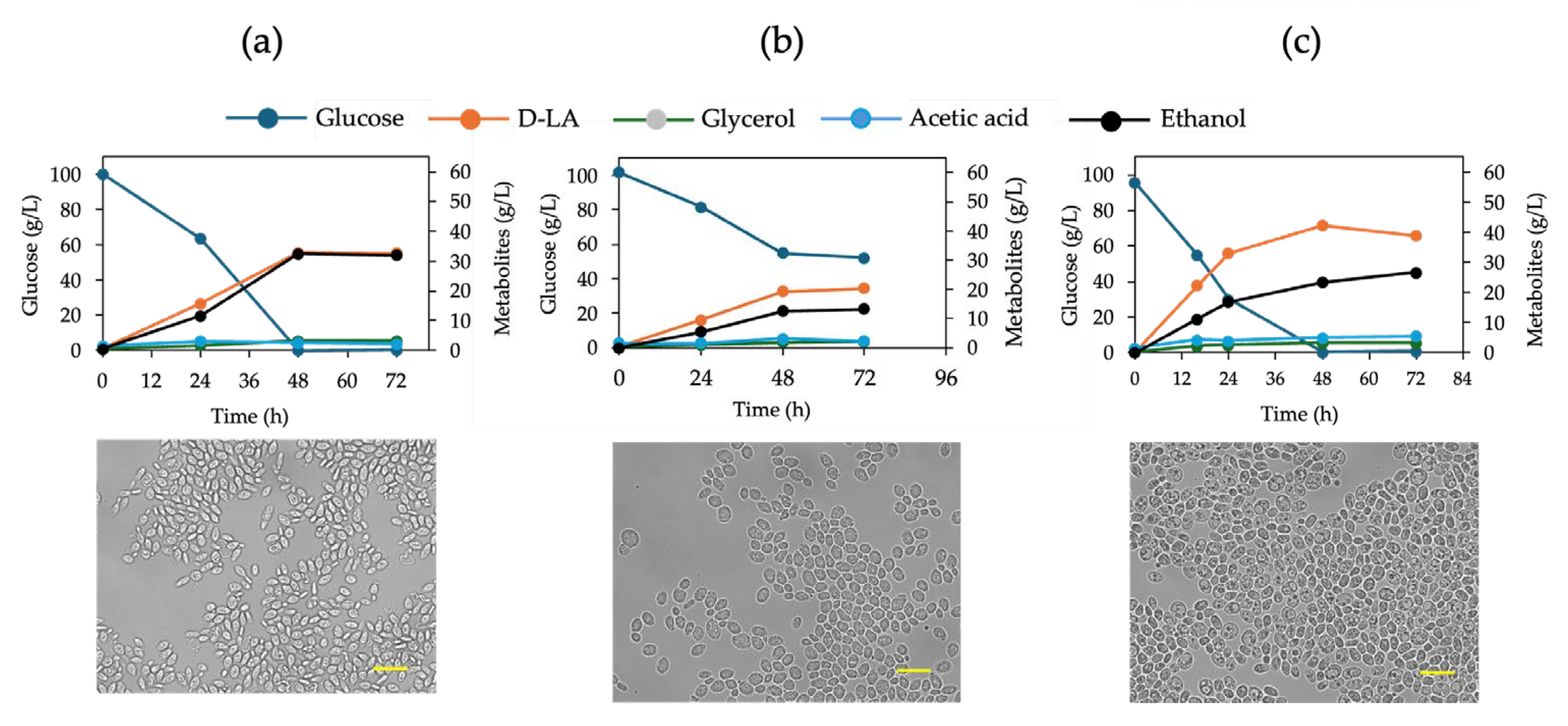

As shown in

Figure 4a, the fermentation performance of F118∆

CYB2::LpDLDH was not significantly affected by CaCO₃ supplementation. Conversely, for F118∆

PDC1::LpDLDH, the D-LA yield did not increase, but complete glucose consumption was achieved after about 48 hours of fermentation (

Figure 4b). This suggests that CaCO₃ improved metabolic stability and glucose utilization, although it did not directly enhance D-LA productivity. Interestingly, in the F118∆

PDC1::LpDLDH strain, where disrupting the pyruvate decarboxylase pathway limits ethanol production and cell growth, the presence of CaCO₃ significantly reduced growth inhibition and increased overall lactic acid accumulation. This indicates that CaCO₃ not only prevents medium acidification but also indirectly helps maintain intracellular pH balance. At the transcriptional level, adding CaCO₃ significantly elevated

LpDLDH expression in F118∆

CYB2::LpDLDH by 983-fold, while most other genes remained unchanged (

Figure 5). Among the few upregulated genes were

YGP1,

FLO5, and

LpDLDH, which are associated with cell wall integrity and flocculation. Under these conditions, increased cell aggregation and turbidity were clearly visible, demonstrating that CaCO₃ supplementation enhanced flocculation behavior not only in the naturally strong-flocculant F118∆

CYB2::LpDLDH but also in the initially weak-flocculant F118∆

PDC1::LpDLDH, as shown in

Figure 4.

The relationship between CaCO₃ addition, cell wall stability, and flocculation aligns with previous findings in

S. cerevisiae, where

FLO1,

FLO5, and

FLO11 govern cell–cell adhesion and aggregation [

17,

18]. Specifically,

FLO5 has been recognized as a key determinant of flocculation [

19] and of cell wall assembly and organization [

20], particularly in wine yeast strains.

Overall, while CaCO₃ supplementation did not increase D-LA yield, it promoted complete substrate utilization and enhanced cell flocculation, likely through the combined effects of pH stabilization, upregulation of FLO5 and YGP1, and improved cell wall integrity. These findings suggest that mild buffering can influence cell physiology, support strong aggregation, and sustain metabolic activity under acidic fermentation conditions.

3.3. Effect of Inhibitory Chemical Compounds on D-LA Production

To evaluate the effect of lignocellulosic-derived inhibitors on D-LA (D-LA) production, 5% of an inhibitory chemical compound mixture (ICCs) was added to the fermentation medium. This concentration was selected based on preliminary trials showing severe growth inhibition at 10–20% ICCs (data not shown). Furfural, the most toxic component among ICCs, is known to impair S. cerevisiae growth, metabolism, ethanol production, and cell morphology by inducing oxidative and membrane damage [

4,

6,

21]. To mitigate medium acidification and enhance strain performance, sodium hydroxide was added at the start of fermentation to maintain the initial pH between 5.0 and 6.0. In previous studies, the parental F118 recombinant strain producing L-LA could tolerate up to 20% ICCs without pH control, although LA productivity declined markedly [

22].

At ICCs below 5%, the engineered strain F118Δ

CYB2::LpDLDH maintained a moderate fermentation profile (

Figure 6a). Glucose was almost completely consumed within 48 h, and the D-LA titer increased from 20.42 g/L to 32.82 g/L compared with the control (without ICCs). In contrast, the F118Δ

PDC1::LpDLDH strain showed markedly impaired glucose utilization, indicating strong growth inhibition by ICCs (

Figure 6b). Supplementation with 3 g/L CaCO₃ substantially improved this strain’s performance, enabling full glucose consumption within 48 h and increasing the D-LA titer from 20.31 g/L to 42.36 g/L (

Figure 6c). This enhancement demonstrates the buffering and detoxification effects of CaCO₃ under weak-acid and aldehyde stress. Microscopic images (

Figure 6, bottom panels) depict cellular morphology and flocculation behavior after 72 h of fermentation. The Δ

CYB2 strain exhibited strong cell aggregation and compact floc structures, whereas the Δ

PDC1 strain showed mostly dispersed cells with reduced adhesion. CaCO₃ buffering enhanced cell integrity and aggregation, indicating a stabilizing effect against ICC-induced acid stress and supporting sustained D-LA production.

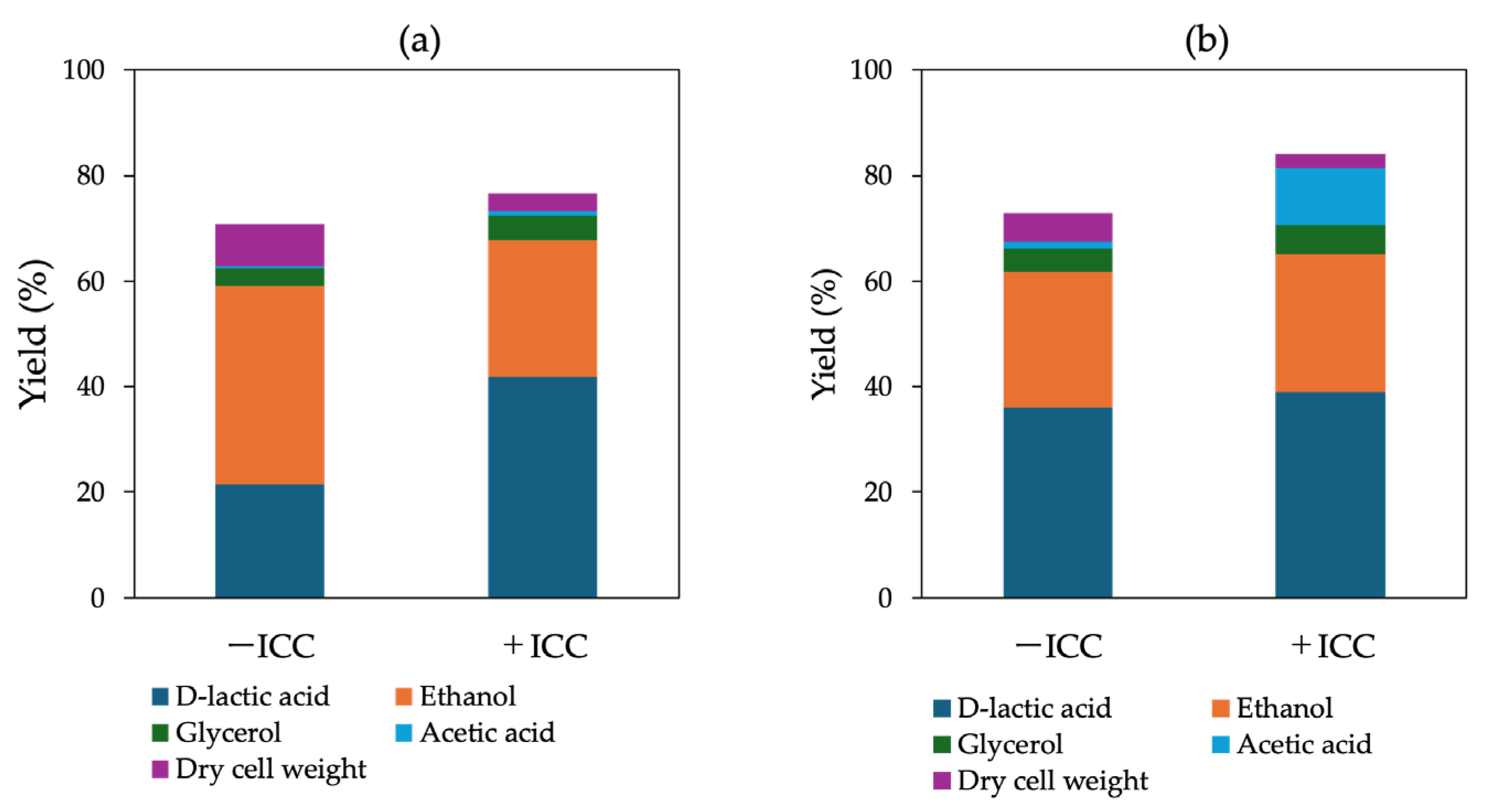

Carbon flux analysis revealed that F118Δ

CYB2::LpDLDH redirected pyruvate toward D-LA rather than biomass or ethanol production (

Figure 7a), as reflected by reduced biomass yield and ethanol formation. This metabolic shift, coupled with higher ICCs tolerance, suggests that F118Δ

CYB2::LpDLDH can efficiently reallocate carbon resources under stress, while F118Δ

PDC1::LpDLDH relies on external neutralization to sustain productivity. Despite its growth limitation, CaCO₃-supplemented F118Δ

PDC1::LpDLDH achieved the highest D-LA titer among all tested conditions (

Figure 7b).

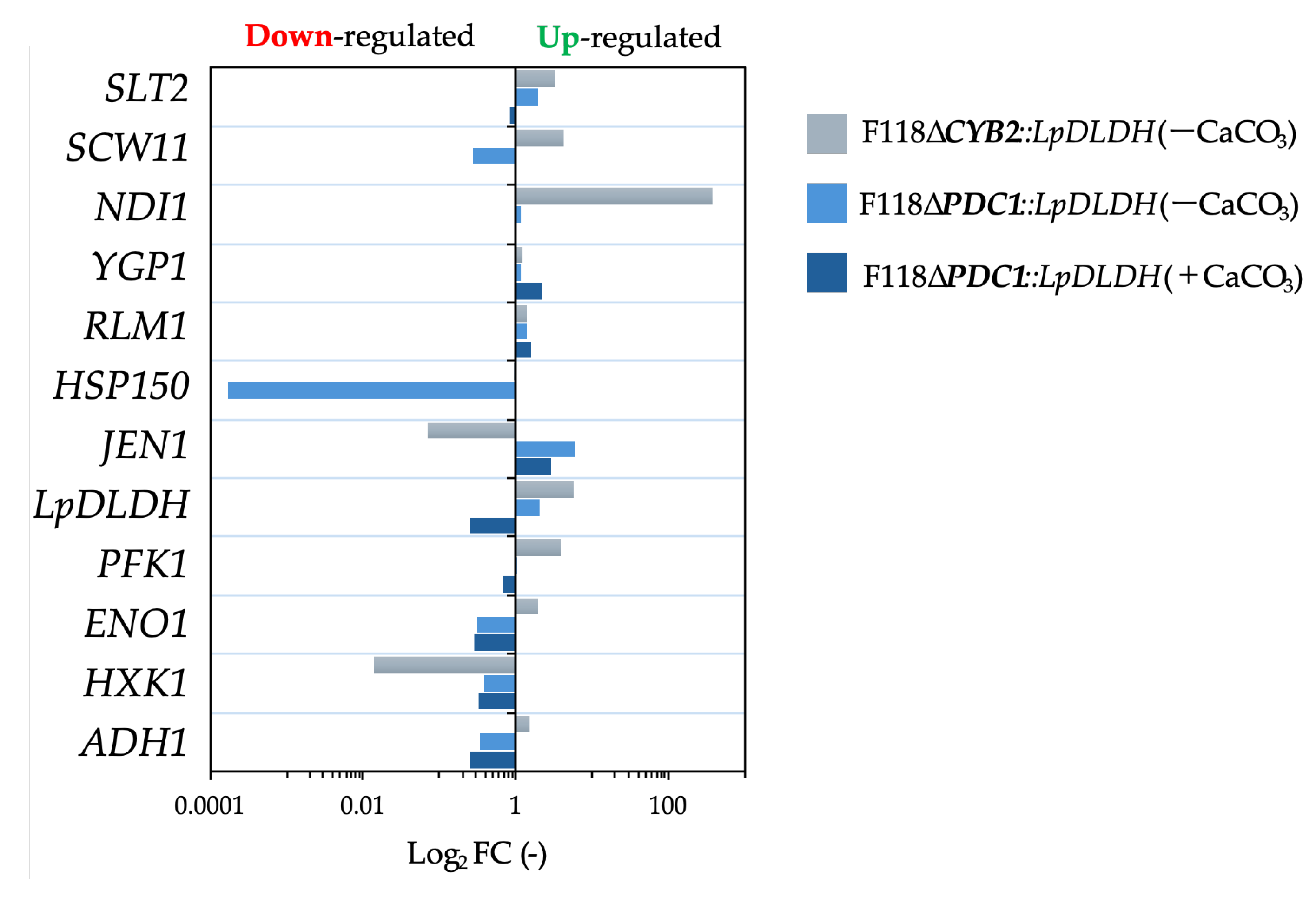

To further elucidate transcriptional responses to ICCs, genes associated with carbon metabolism, stress adaptation, and energy regulation were analyzed by qPCR in cells cultured in YPD100 medium, with or without 5% ICCs. The target genes included those involved in glycolysis and ethanol metabolism (

HXK1, PFK1, ENO1, ADH1, LpDLDH), lactic acid formation (

LpDLDH), lactate transport (

JEN1), stress and cell-wall remodeling (

SLT2, RLM1, SCW11, HSP150, YGP1), and mitochondrial energy metabolism (

NDI1). As illustrated in

Figure 8, several genes were significantly upregulated in the presence of ICCs, including

PFK1 and

ENO1 (glycolysis),

ADH1 (ethanol metabolism),

LpDLDH (lactate production), and

JEN1 (lactate export). Stress-related genes (

SLT2, RLM1, YGP1, SCW11) also showed increased expression, indicating activation of the cell wall integrity (CWI) and general stress response pathways. Notably, NDI1 expression was markedly induced in F118Δ

CYB2::LpDLDH, suggesting enhanced mitochondrial NADH oxidation and energy turnover, which may contribute to increased stress tolerance. In F118Δ

PDC1::LpDLDH, strong

LpDLDH induction under CaCO₃ supplementation indicated partial recovery of lactate flux, compensating for the loss of pyruvate decarboxylase activity and growth inhibition.

To further elucidate the molecular responses of engineered S. cerevisiae strains to inhibitory chemical compounds (ICCs), we examined transcriptional and metabolomic alterations during fermentation. Genes associated with glycolysis, ethanol metabolism, D-LA production, stress adaptation, and mitochondrial energy regulation were analyzed via quantitative PCR in cells cultivated in YPD100 medium, with or without 5% ICCs. The genes selected for analysis included HXK1, PFK1, ENO1, ADH1, and PDC1 (carbon metabolism); LpDLDH (D-LA production); JEN1 (lactate transport); SLT2, RLM1, SCW11, HSP150, and YGP1 (cell-wall integrity and stress response); and NDI1 (mitochondrial energy metabolism).

As depicted in

Figure 8, several glycolytic genes (

PFK1, ENO1) and ethanol-related genes (

ADH1) were significantly upregulated under ICC exposure, indicating an enhanced flux through upper glycolysis and redox rebalancing. The strong induction of

LpDLDH and

JEN1 suggested that the lactate synthesis and export system remained active even under inhibitor stress, supporting continued D-LA accumulation. Stress-responsive genes (

SLT2, RLM1, YGP1, SCW11) were also markedly upregulated, reflecting the activation of the cell wall integrity (CWI) and general stress response pathways.

Notably, NDI1 expression was strongly induced in F118ΔCYB2::LpDLDH, suggesting reinforcement of mitochondrial NADH oxidation to sustain ATP generation and mitigate redox imbalance. Conversely, F118ΔPDC1::LpDLDH exhibited enhanced LpDLDH expression, particularly under CaCO₃ supplementation, indicating a partial recovery of lactate flux that compensated for the loss of pyruvate decarboxylase activity and associated growth inhibition.

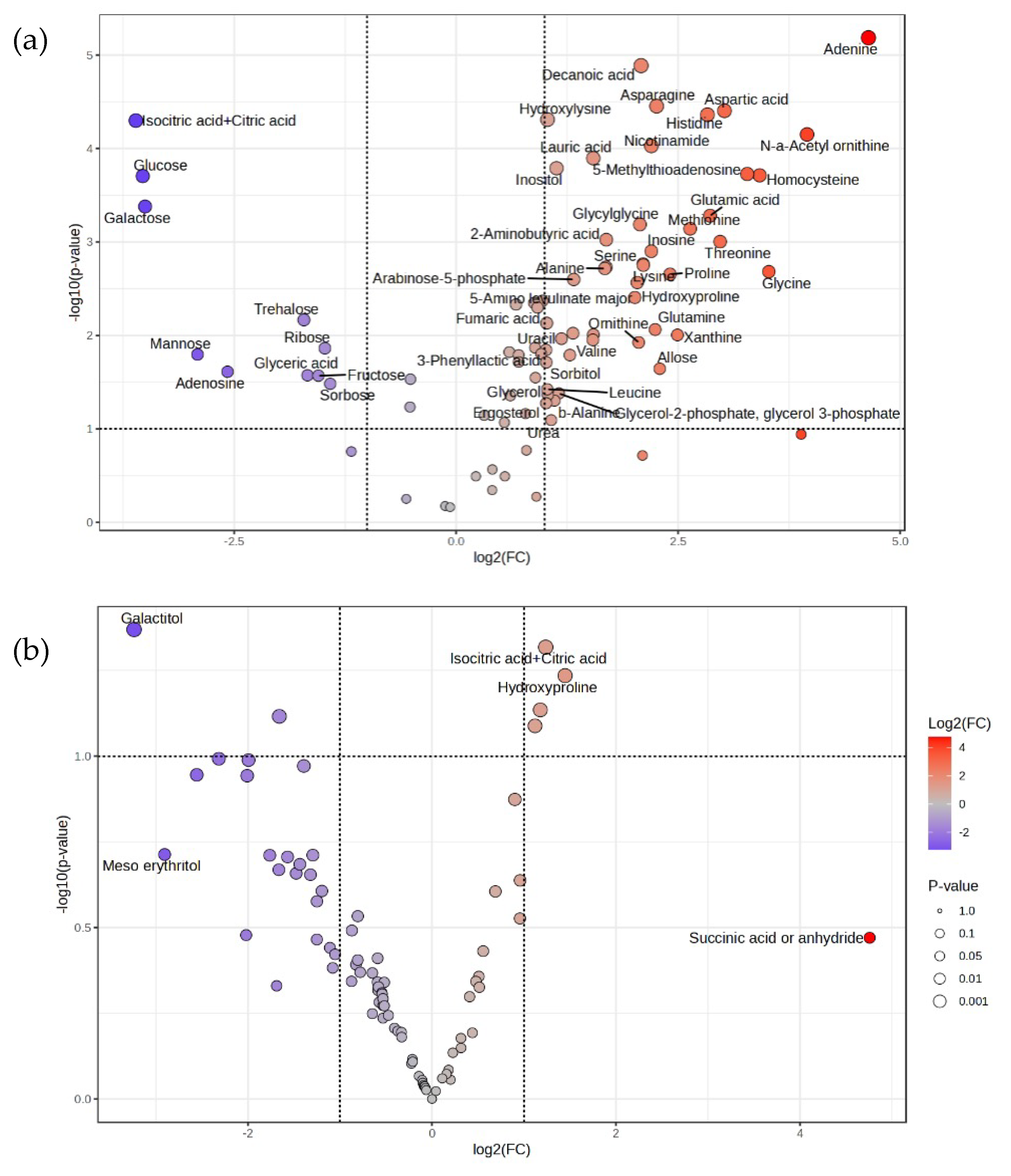

Given the tight coupling between transcriptional and metabolic networks, metabolomic profiling was performed to assess differential metabolite accumulation in response to ICC exposure. As shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, F118Δ

CYB2::LpDLDH exhibited a larger number of significantly altered metabolites, while F118Δ

PDC1::LpDLDH displayed fewer but more specific changes, consistent with its lower metabolic turnover rate.

In F118ΔCYB2::LpDLDH, several amino acids (aspartic acid, histidine, serine, threonine, glycine) were significantly elevated, suggesting enhanced nitrogen assimilation and stress-driven amino acid turnover. Increased levels of adenine, nicotinamide, and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates (citric, isocitric, and fumaric acids) indicate activation of nucleotide biosynthesis and reinforcement of oxidative metabolism to maintain redox balance. In contrast, decreases in glucose, mannose, ribose, and trehalose indicated glycolytic suppression and a diversion of carbon toward maintenance metabolism and osmolyte production—strategies commonly employed to withstand weak-acid and aldehyde stress.

In F118ΔPDC1::LpDLDH, the metabolomic profile showed accumulation of succinic acid and its anhydride derivative, pointing to a redirection of pyruvate metabolism through mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC) as a gate transporter toward reductive branches of the TCA cycle. Simultaneous increases in citric and isocitric acids, coupled with declines in sugar alcohols (meso-erythritol, galactitol), suggest a shift from carbohydrate storage toward energy-generating intermediates. These results imply that in the absence of PDC1, the strain compensates for the blocked ethanol pathway by enhancing TCA cycle flux and maintaining NAD⁺/NADH homeostasis under ICC-induced oxidative stress.

An observed increase in sedoheptulose-7-phosphate (S7P) under +ICC conditions further supports the activation of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP). This change indicates enhanced NADPH production, which is vital for detoxifying furfural and other aldehyde inhibitors through reductive conversion mechanisms [

23]. By strengthening both the PPP and the TCA cycle, the cells maintain sufficient reducing equivalents (NADH/NADPH) to reduce oxidative stress and preserve metabolic function during inhibitory fermentation.

The transcriptional and metabolomic data elucidate a complex adaptive response to ICC stress. The upregulation of glycolytic and stress-protection genes, in conjunction with the activation of PPP- and TCA-associated redox balancing, illustrates a coordinated reprogramming of central metabolism. This integrative mechanism enables engineered S. cerevisiae strains to maintain D-LA production under conditions that mimic lignocellulosic hydrolysate by balancing energy generation, redox homeostasis, and stress defense pathways.

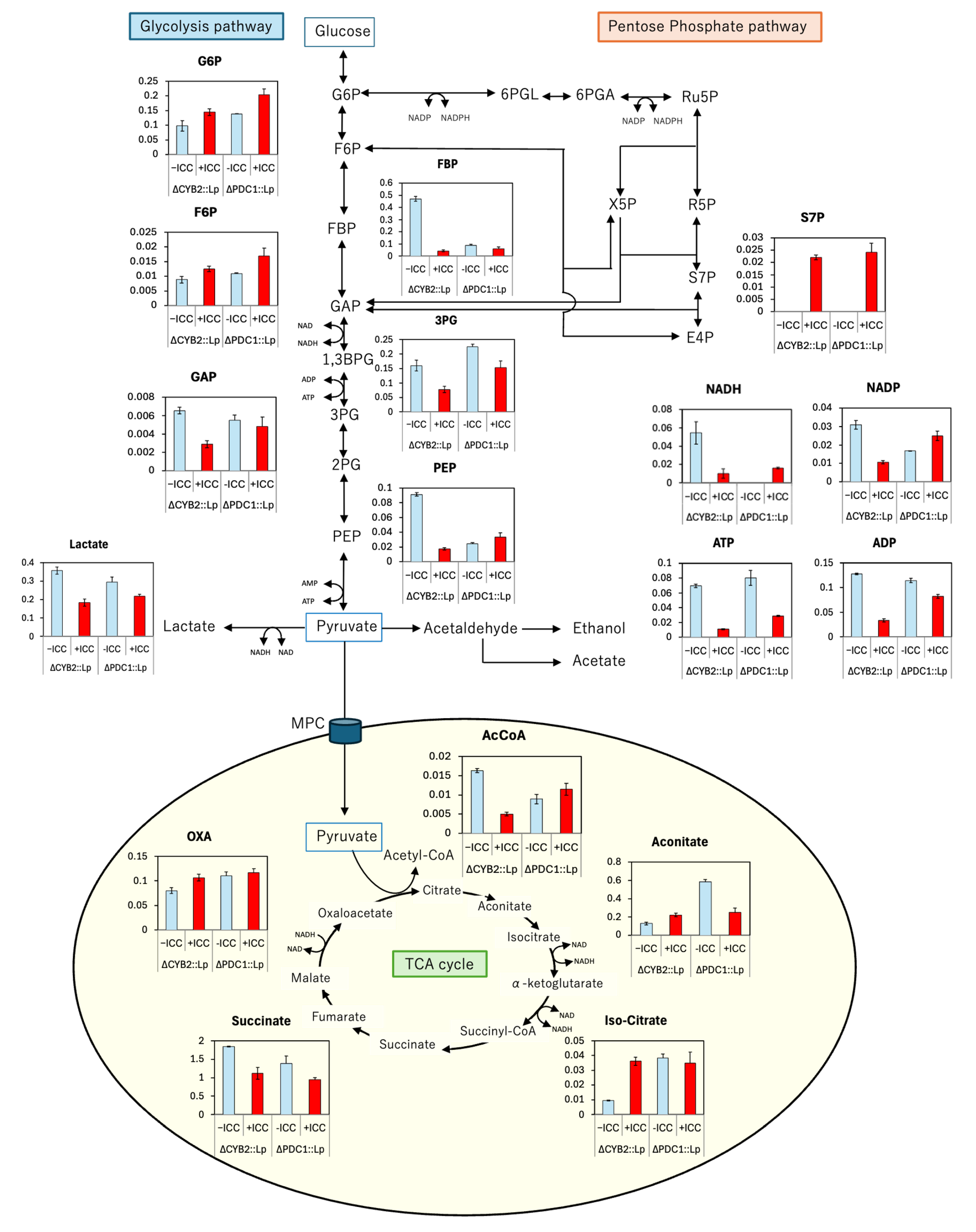

To evaluate how pH buffering by CaCO₃ influences metabolic flux during D-LA fermentation, intracellular metabolites in

S. cerevisiae F118Δ

PDC1::LpDLDH were quantified under cultures with (+CaCO₃) and without (−CaCO₃) supplementation (

Figure 11). The metabolomic map revealed that CaCO₃ markedly modulated carbon flow through glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle.

CaCO₃ buffering increased the intracellular levels of key glycolytic intermediates, including glucose-6-phosphate, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, and phosphoenolpyruvate, suggesting enhanced glycolytic throughput under stabilized pH conditions. The elevated levels of glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) and 6-phosphogluconate (6-PGL) in the PPP indicate activation of NADPH-producing reactions that support antioxidant defense and biosynthetic reduction potential. This effect is consistent with the neutralizing role of CaCO₃ in mitigating intracellular acidification, thereby relieving feedback inhibition on glycolytic enzymes and allowing continued ATP production.

Under conditions of +CaCO₃, a consistent increase in acetyl-CoA, citrate, and succinate was observed, indicating stimulation of the TCA cycle. The rise in oxaloacetate and malate further suggests that buffering maintains metabolic continuity between glycolysis and the TCA cycle through the pyruvate-to-acetyl-CoA node. These increases imply that CaCO₃ supplementation facilitates smoother energy generation and NADH reoxidation, counteracting the acid stress that otherwise restricts oxidative metabolism during unbuffered fermentation. In the absence of buffering (−CaCO₃), the accumulation of acidic end products, such as D-LA, lowers intracellular pH and limits enzyme activity in both glycolysis and the TCA cycle. The observed metabolite restoration under +CaCO₃ thus reflects improved redox homeostasis, as the buffering system prevents proton overload and promotes continuous NADH oxidation through the TCA cycle. This redox balancing effect aligns with the previously observed transcriptional upregulation of NDI1 and LpDLDH under buffered conditions, highlighting a synergistic link between pH control and metabolic adaptation. Collectively, these results demonstrate that CaCO₃ supplementation stabilizes intracellular pH, sustains glycolytic flux, enhances PPP-derived NADPH generation, and strengthens TCA-cycle activity. This integrated response maintains energy production and redox balance, thereby supporting robust D-LA fermentation even under high-acid conditions. The metabolic stabilization provided by CaCO₃ complements the genetic modifications in PDC1-deficient strains, enabling improved tolerance and productivity in lignocellulosic hydrolysate–based bioprocesses.