1. Introduction

Among the various ecological consequences of road networks, wildlife roadkill stands out as one of the most prominent threats (Taylor and Goldingay 2010; Pinto et al. 2020). The risk of vehicle collision with terrestrial vertebrates varies according to species’ life history, as animal movement is essential for foraging, reproduction, and survival (Fahrig 2007; Medrano-Vizcaíno et al. 2022). In addition to biological factors, road characteristics—such as speed limits, traffic intensity, and road curvature—further exacerbate the likelihood of accidents (Jamhuri et al. 2020; Medrano-Vizcaino et al. 2023). Given that collisions with wildlife can also be fatal for humans, especially those involving medium and large mammals (Freitas and Barszcz 2015; Abra et al. 2019), improving road safety is paramount to safeguard both biodiversity and road users (Rytwinski et al. 2016; Ascensão et al. 2017).

Medium and large mammals, particularly those with greater mobility, are more likely to cross roads during their movement periods compared to species with smaller home ranges (Poessel et al. 2014). Many of these species utilize riverbanks as movement corridors (Bueno et al. 2015), making them especially vulnerable in areas where roads intersect with waterways (Martins et al. 2024a). According to Medrano-Vizcaíno et al. (2022), mammals most at risk of roadkill in Latin America tend to be slow-moving, diurnal, medium-sized (e.g., between 2 and 35 kg), or scavengers. Rytwinski and Fahrig (2012) suggest that large mammals, especially those with low reproductive rates and high mobility, are particularly vulnerable to roadkill, which significantly impacts their populations. In Brazil, four species account for over 30% of all recorded mammal roadkill data: the crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous) (Linnaeus 1766), six-banded armadillo (Euphractus sexcinctus) (Linnaeus 1758), southern tamandua (Tamandua tetradactyla) (Linnaeus 1758), and giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) Linnaeus, 1758 (Cirino et al. 2022). However, only the giant anteater is listed as threatened with extinction (ICMBio 2024).

Despite the substantial investments made in road infrastructure in Brazil (Silva et al. 2016), funding for wildlife roadkill mitigation measures remains insufficient. Prioritizing which road segments to address for mitigation is a complex task. Identifying roadkill hotspots—areas with a high concentration of roadkill incidents—serves as a useful tool in the decision-making process (Coelho et al. 2012). However, roadkill hotspots are subject to seasonal fluctuations due to changes in vehicle flow and population dynamics in nearby ecosystems (Teixeira et al. 2017). Consequently, defining mitigation strategies based solely on hotspots carries inherent risks, as the situation can vary over time. Traditional mitigation measures often focus on actions such as the installation of wildlife crossings and fencing along roads that pass through native vegetation and riparian zones (Cirino et al. 2022; (Martins et al. 2024b). However, such approaches may not be sufficient, as species have different habitat preferences and movement patterns (Abra et al. 2020). One alternative is to group species into functional categories, allowing for the evaluation of roadkill impacts on sets of species with similar ecological characteristics (Dornelles 2015; Secco et al. 2024). In addition to understanding species’ movement and behavior, identifying the landscape patterns that influence roadkill occurrence is essential for informing conservation and road safety efforts (Santos et al. 2023). By linking landscape variables with georeferenced roadkill data, researchers can develop reliable predictive models to better understand spatial patterns of roadkill (Freitas et al. 2015).

This approach is particularly relevant in anthropized regions and those experiencing landscape changes, where understanding the interplay between species and their environment can guide effective mitigation strategies. The Cantareira-Mantiqueira Corridor, traversed by the Dom Pedro I Highway (SP-065) in São Paulo state, has undergone significant land-use changes in recent decades (Boscolo et al. 2017). This landscape mosaic is a priority area for the conservation of medium and large mammals due to its high connectivity potential between Atlantic Forest fragments (Hilasaca et al. 2021). With this background in mind, we seek to answer the following research question: which landscape variables contribute most to the occurrence of medium and large mammal roadkill in the Cantareira-Mantiqueira Ecological Corridor? We propose the following hypotheses: H1 – A higher percentage of forest cover correlates with increased roadkill rates for mammals that avoid anthropogenic areas (Freitas et al. 2013); H2 – A higher percentage of anthropogenic areas (e.g., agriculture and urbanization) correlates with higher roadkill rates for more generalist mammal species, which are commonly found in these areas (Bueno et al. 2015); and H3 – A greater proportion of water bodies correlates with increased roadkill incidents involving capybaras (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) (Ascensão et al. 2019).

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

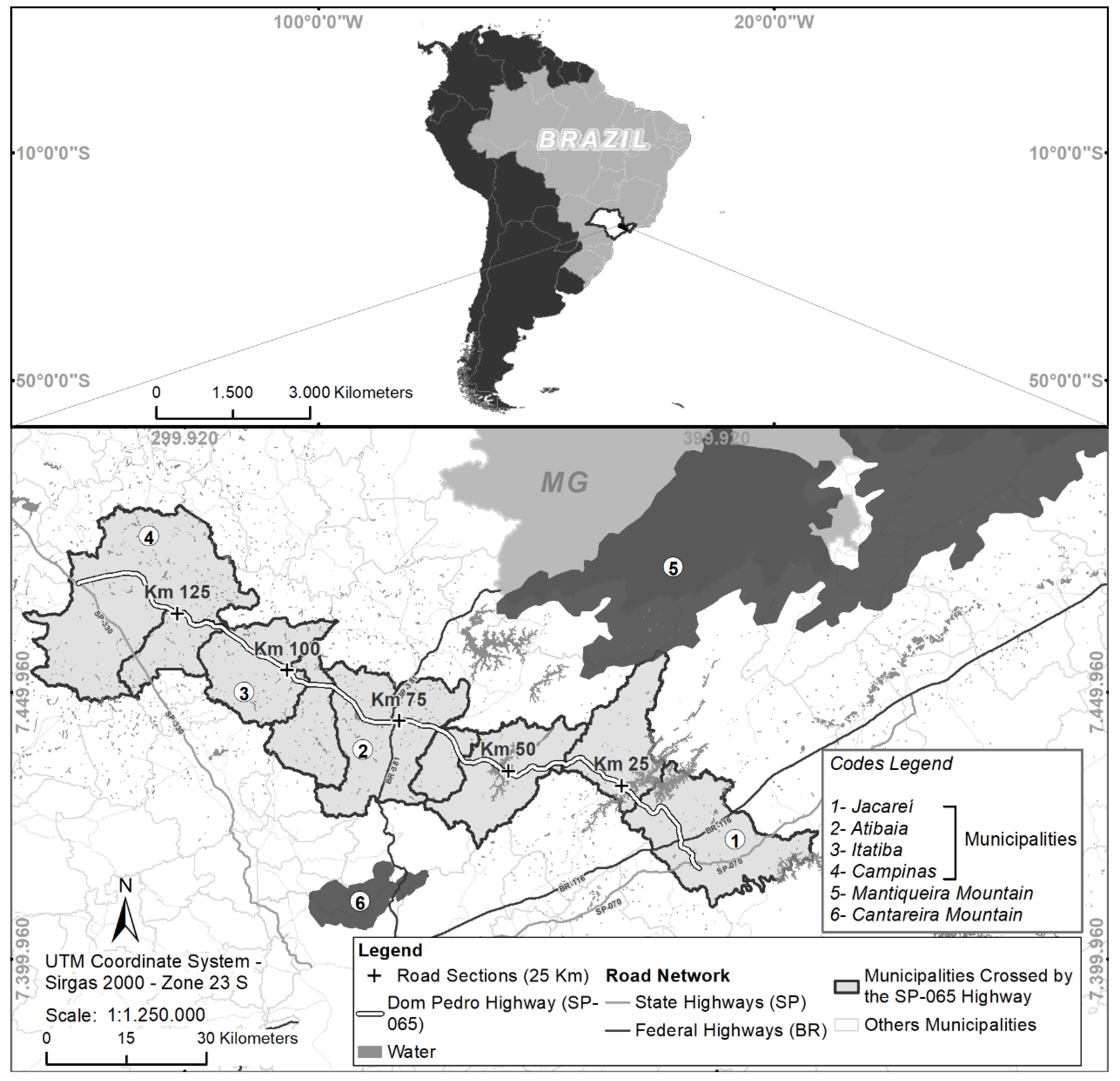

The study area is part of the Long-Term Ecological Research Program of the Cantareira-Mantiqueira Ecological Corridor (PELD CCM), located at the transition between the northeastern state of São Paulo and the southern region of Minas Gerais, Brazil. The region serves as a connection between two major mountain ranges: the Cantareira and Mantiqueira mountains (Boscolo et al. 2017) (

Figure 1). The landscape mosaic includes various forest types in different successional stages, conservation units (CUs), agricultural plantations, pastures, silviculture (mainly

Eucalyptus spp.), wetlands, rivers, highways, villages, and even large urban centers (Hilasaca et al. 2021). The Cantareira-Mantiqueira Ecological Corridor lies within the Atlantic Forest biome, which contains small forest fragments (84% of them are smaller than 50 ha), under significant edge effects and a high degree of isolation (with an average distance of approximately 1,440 meters between two fragments) (Ribeiro et al. 2009).

The PELD CCM research has been carried out in the municipalities of Bragança Paulista, Itatiba, Atibaia, Mairiporã, São Paulo, and Joanópolis (

Figure 1). In that way, for this study we analyzed data on roadkill incidents involving medium and large mammals along the Dom Pedro I Highway (SP-065), which traverses these landscapes. The highway is one of the most important in the state of São Paulo, with an average of 450,000 vehicles passing daily (CRB 2024). Its construction, planned in 1960, was intended to connect the Anhanguera (SP-330) and Dutra (BR-116) highways, diverting traffic from the São Paulo metropolitan area (CRB 2024). Spanning 145 kilometers, it facilitates the flow of traffic between the Paraíba Valley and the Greater Campinas area (ARTESP 2022). From 1988 to 2009, the Dom Pedro I Highway was managed by Desenvolvimento Rodoviário S.A. (DERSA), a state-controlled mixed-economy company (ARTESP 2022). DERSA was responsible for its duplication and the creation of the access road to the Governador Carvalho Pinto Highway (SP-070) (DER 2024). Since April 2009, the highway has been under the management of the Rota das Bandeiras concessionaire (DER 2024).

Regarding mitigation measures, the SP-065 highway has two wildlife underpasses installed in the Campinas municipality area (at km 143+555 and km 144+450), each consisting of circular culvert (diameter greater than 2 meters). Additionally, the concessionaire mapped 33 another culverts, 12 cattle underpasses, and 52 existing bridges along the highway where adaptations can be made, such as natural embankments, guiding fences, and dry underpasses, to function as wildlife passages. The highway also features 38 wildlife crossing warning signs. Traffic speed is controlled by 15 fixed radar units, with 11 on the southbound lanes and 4 on the northbound lanes.

2.2. Roadkill Data

The highway concessionaires are responsible for the maintenance of the highways they manage. This includes daily inspections every three hours in the state of São Paulo (Abra et al. 2021) of sections under their jurisdiction, specifically looking for roadkill incidents. In an effort to standardize the way accidents are recorded and to monitor the disposal of carcasses, the São Paulo State Environmental Company (CETESB) requires state road operators to generate periodic reports on wildlife mortality (CETESB 2018). Accordingly, we requested data from the Dom Pedro I Highway (SP-065) between April 2014 and June 2021, collected by the Rota das Bandeiras concessionaire. The data were validated by an environmental consulting firm hired by the concessionaire.

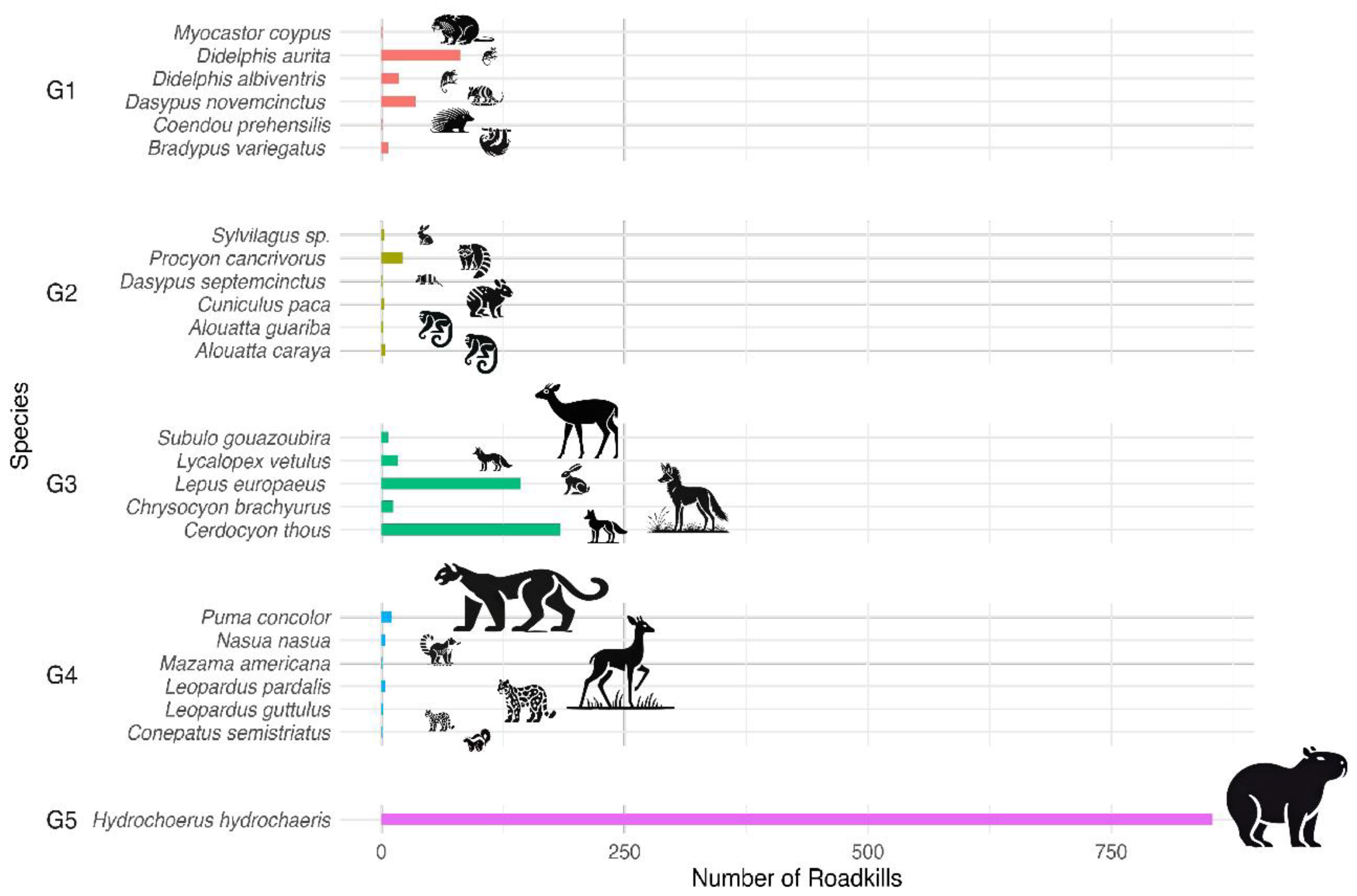

2.3. Functional Groups

The medium and large mammals recorded (body mass ≥ 1 kg) (Paglia et al. 2012; Ascensão et al. 2019) were classified into five functional groups based on their home range size and use of anthropogenic areas, such as pastures, agricultural plantations and reservoirs (IUCN 2024). The home range classification was based on the median values obtained from the literature (Varela et al. 2010; Benavides et al. 2017; Dias et al. 2019; Feijó 2020; Broekman et al. 2023). The established functional groups were as follows: G1 – Mammals with small home ranges (< 30,635 ha) common in anthropogenic areas; G2 – Mammals with small home ranges (< 30,635 ha) that avoid anthropogenic areas; G3 – Mammals with large home ranges (≥ 30,635 ha) common in anthropogenic areas; G4 – Mammals with large home ranges (≥ 30,635 ha) that avoid anthropogenic areas; G5 – Capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) (Linnaeus 1766). Although the capybara has a large home range (≥ 30,635 ha) and is common in anthropogenic areas, it was placed in a separate group due to being the most abundant species in the dataset, with a roadkill rate significantly higher than the other species in group G3. Data for small mammals were excluded from the analysis due to difficulties in species identification by traffic inspectors (Abra et al. 2018), as well as under-sampling (Santos and Ascenção 2019).

2.4. Landscape Variables and Analysis Scale

For land use and land cover (LULC), we used data from MapBiomas (MapBiomas Project 2021), with a 30 m pixel size. Prior to selecting MapBiomas collection 8, we reviewed the LULC data for the period corresponding to the time when roadkill data were collected (2014-2021) and found that the landscape remained stable (i.e. 94% with the same LULC in 2014 and in 2021). Our variables of interest, expressed as percentages, included: forest, pasture, agriculture, silviculture, urbanized areas, land use mosaics, and water bodies. These classes were chosen because they are predominant around the highway. For each functional group, we considered influence radii of specific dimensions (Ciocheti 2014; Dornelles 2015), as the species within each group have distinct home ranges and habitat requirements. The radius was used to create a buffer, with the center given by the geographical coordinates of the roadkill records. This allowed us to calculate the landscape composition within the buffers. For functional groups G1 and G2 (small home range mammals), an initial radius of 500 m was used, ensuring that the landscape variables around these animals’ core habitats are accurately captured, reflecting their immediate surroundings and ecological interactions. Also, smaller buffers would not fit well with the spatial resolution of the LULC map. For functional groups G3, G4, and G5 (large home range mammals), an initial radius of 3,000 m was used. To assess the effect of scale (Jackson and Fahrig 2012), we also analyzed buffers with double the initial radius for all functional groups.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The records of mammal roadkill incidents were linked to landscape variables in order to identify ecological patterns that could explain vehicle collisions with wildlife. For each roadkill event, we generated a random point to represent a pseudo-absence of roadkill. These points, along with the actual roadkill occurrences, were then used to create a presence-absence matrix, with equal numbers of presence (1) and absence (0) entries for each functional group.

To estimate the relative likelihood of roadkill, we built generalized linear models (GLMs) using a binomial distribution, where the presence and absence data served as the response variable. The proportion of the seven landscape variables within the influence radii of each roadkill event were used as predictor variables. Separate groups of models were constructed for each functional group. We tested for correlations between the landscape variables, excluding models with variables with a correlation greater than 0.6 or less than -0.6 between themselves. Models exhibiting multicollinearity (Variance Inflation Factor > 4.0) were also discarded. All models were ranked using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and selected based on their corrected AIC (AICc), with lower AICc values indicating better-fitting models. Models with a ΔAICc ≤ 2 and evidence ratio less than 2 were considered equally plausible. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.3.3 (R Core Team, 2024), with the packages ‘bbmle’, ‘numDeriv’, ‘efeitos’, ‘ggplot2’, and ‘corrplot’.

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of Roadkill Incidents

Between April 2014 and June 2021, a total of 1,418 medium- and large-sized mammals were recorded as roadkill along the Dom Pedro I Highway (SP-065), representing 24 different species (

Table 1). The estimated roadkill rate was 0.00357 individuals/km/day. Among the georeferenced records, 854 (~60%) were capybaras (

Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) – classified as Group G5. The second most affected species was the crab-eating fox (

Cerdocyon thous) (Linnaeus 1766), with 184 records (~13%), followed by the European hare (

Lepus europaeus) (Pallas 1778), with 143 records (~10%). Together, these three species accounted for 83% of the dataset. The European hare is an exotic herbivore and invasive species in Brazilian biomes (Freitas et al. 2015), introduced for sport hunting along the border of Rio Grande do Sul and Uruguay in the 1950s (Rosa et al. 2017). Eight species included in the dataset are listed in at least one of two threat categories—endangered or vulnerable—at the local (São Paulo, 2018), regional (MMA 2022), or global (IUCN 2023-1) levels (

Table 1).

When analyzing the relative abundance of roadkill across functional groups, Group G5 (capybaras) was by far the most represented. The second most frequent group was G3 (large home range mammals common in anthropogenic areas), comprising five species and approximately 25% of the records. This was followed by G1 (small home range mammals common in anthropogenic areas), represented by six species and 10% of the records. Groups G2 (small home range mammals that avoid anthropogenic areas) and G4 (large home range mammals that avoid anthropogenic areas) each contributed just over 4% of the total roadkill, with both groups represented by six species each. The classification of mammals into their respective functional groups based on the adopted criteria is illustrated in

Figure 2.

3.2. Model Selection

From the analyses conducted, four models were selected based on AICc across the different evaluated scales (

Table 2). For Group G1 – small home-range mammals commonly found in anthropic areas – the best model indicated a positive effect of native forest and pasture on roadkill occurrences within a 500 m radius. Conversely, a negative relationship was observed for the land-use mosaic in this model (

Figure S1). For Group G3 – large home-range mammals commonly found in anthropic areas – two models were selected, one for a 3,000 m radius and another for a 6,000 m radius. However, the 3,000 m radius model had the lowest AICc value (1000.77). In both models, pasture and agriculture showed a positive effect on roadkill occurrences (

Figure S2 and S3), although the p-values for pasture were not statistically significant (3,000 m radius:

p = 0.069; 6,000 m radius:

p = 0.110). For Group G5 – capybara (

Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) – positive effects of pasture and agriculture were observed within a 3,000 m radius, while, similar to Group G1, the land-use mosaic had a negative effect (

Figure S4). At the 6,000 m radius, the same influences were observed. However, these results were also not statistically significant (

p > 0.05).

For Group G1 (1,000 m radius), Group G2 (500 m and 1,000 m radii), and Group G4 (3,000 m and 6,000 m radii), the null model was selected as the best model. This suggests that factors not included in the models likely play a stronger role in explaining roadkill occurrences than the evaluated landscape variables. However, it is important to note that Groups G2 and G4 had low sample sizes (35 and 23 roadkill records, respectively), which may have been insufficient to detect patterns in the relationship between roadkill occurrences and landscape characteristics. Regarding land use and cover, the predominant classes surrounding the highway were the land-use mosaic, pasture, and forest, both at the 3 km and 6 km radii (

Table S1). Some land-use classes within the buffers, such as other non-vegetated areas, mining, wetlands, and rocky outcrops, were minimally represented and therefore excluded from the analyses.

4. Discussion

Our study underscores the significant risks that roadkill poses to mammal conservation, even along relatively short road segments. 11% percent of medium and large mammal species known to occur in São Paulo state were documented in this study (Galetti 2022), including eight species threatened at the state level, three at the national level, and two globally. This research is among the few that link landscape features with the probability of roadkill for functional mammal groups on São Paulo’s highways, offering valuable insights into where species are most likely to cross roads and become vulnerable to collisions (Martins et al. 2024a). Roadkill-induced population losses are particularly concerning in the Neotropical region, where land-use changes—primarily for food and energy production—are often viewed as necessary for economic growth, which in turn drives road infrastructure expansion (Freitas et al. 2013). Generally, the most road-killed species are also the most abundant and widely distributed within their ranges (Cáceres 2011; Freitas et al. 2015; Ascensão et al. 2019). Notably, nine of the fifteen most road-killed mammal species in Brazil appear in our records (Pinto et al. 2022). Among large mammals, species like the capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous), maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus) (Illiger, 1815), puma (Puma concolor) (Linnaeus 1771), and red brocket deer (Mazama americana) (Erxleben 1777) can cause severe accidents, including human fatalities and substantial material damages (Freitas and Barszcz 2015; Abra et al. 2019).

Our results reveal that nearly two pumas (Puma concolor) are killed annually on the Dom Pedro I Highway, a concerning rate for the Atlantic Forest biome. For comparison, Secco et al. (2024) recorded three deaths of this species over four years on a 322-kilometer stretch of BR-101 in Rio de Janeiro. Given the naturally low population sizes of pumas (Oliveira et al. 2010), roadkill significantly impacts their populations, as their slow reproduction rates hinder recovery (Azevedo et al. 2013). Although we found no correlation between forest mammals’ roadkill (G2 and G4) and forest areas, the high number of species avoiding anthropogenic areas in our dataset highlights the importance of the Cantareira-Mantiqueira Corridor for conserving mammals sensitive to anthropogenic changes. While the limited sample size for G2 and G4 (n=58) may have constrained pattern detection, evidence suggests these mammals are road-killed randomly, irrespective of land-use classes (Cerqueira et al. 2021). More records may further clarify whether there is a positive effect of forest, due to potentially larger populations in these areas, or a negative effect, as mammals may move less due to readily available resources.

Mammals in functional groups G1, G3, and G5 showed positive responses to pasture and agriculture. These generalist species often inhabit transitional habitats and exploit extensive anthropogenic landscapes, sometimes establishing home ranges in such areas (Cirino et al. 2022). Resources in these environments tend to be sparse and scattered compared to natural landscapes, requiring greater movement and increasing the likelihood of crossing roads and becoming roadkill (Regolin et al. 2021). Additionally, native forest areas positively influenced roadkill rates in G1 mammals, despite their occurrence in anthropogenic areas. Exceptions include species like the nutria (Myocastor coypus) (Molina 1782), which is non-native for the São Paulo state and typically found in wetlands (IUCN 2024). Conversely, the “mosaic” land-use class negatively affected roadkill rates for G1 and G5 groups. This category, defined as a mix of agricultural and pasture areas (Souza et al. 2020), may result in fewer roadkill incidents because its mixed-use characteristics could reduce the frequency of mammal crossings, potentially offering less accessible or desirable resources compared to uniform pasture or agricultural landscapes.

Over time, natural landscapes surrounding roads are often converted into anthropogenic fields and urban areas (Dornelles 2015). This increases isolation for species less tolerant of land-use changes, explaining why such species are less frequently road-killed on older highways like Dom Pedro I (SP-065). Our results for G3 (large home range, common in anthropogenic areas) confirmed our initial hypothesis, showing increased roadkill risks in proportion to altered landscapes. Similarly, pasture positively influenced roadkill rates for G1 mammals, supporting expectations. Unexpectedly, native vegetation also showed a positive association with G1 roadkill, which aligns with their habitat use patterns. However, contrary to our hypothesis, capybara roadkill was not influenced by proximity to water bodies (Felix et al. 2014), but rather by agricultural and pasture landscapes (Bueno et al. 2013; Silva et al. 2022). This is likely because Dom Pedro I crosses two major aquatic systems—the Jaguari River and Atibainha Reservoir—where bridge structures include barriers (mainly Jersey barriers) preventing wildlife crossings while maintaining habitat connectivity below. Regarding spatial scales, our results indicate that the presence of forest fragments and pastures within a 500-meter radius of the highway increases roadkill risks for G1 mammals, such as the brown-throated sloth (Bradypus variegatus) (Schinz 1825), which depend on vegetation and frequently cross roads to access other fragments (Freitas et al. 2013). For G3 mammals, agricultural landscapes within a 3,000-meter radius also showed positive associations with roadkill, with effects extending to 6,000 meters, reflecting their broader dispersal capacities (Freitas et al. 2015). Similarly, capybara roadkill (G5) responded positively to pastures and agricultural areas within 3,000 meters of the road, likely due to abundant food resources in these matrices (Ferraz et al. 2007).

Functional group-based impact assessments proved effective, enabling multi-species mitigation strategies (Freitas et al. 2015) and optimizing resource allocation. Mitigation actions should align with the biological and behavioral traits of each group. The positive relationship between pasture/agriculture and roadkill underscores the need to shift mitigation paradigms, which typically prioritize hotspots near native vegetation and riparian forests (Cirino et al. 2022). However, landscape influence analyses should complement rather than replace hotspot identification, ensuring mitigation measures address specific ecological problems for each highway (Martins et al. 2024b). Our findings also highlight the shared responsibilities among stakeholders in addressing medium and large mammal roadkill. Road operators must enhance infrastructure to ensure genetic flow and ensure wildlife crossings occur through appropriate infrastructure, such as underpasses or overpasses, rather than across traffic lanes. Given that landscape-scale effects extend beyond the 60-meter-wide road domain (DER 2024), integrated landscape management within environmental licensing frameworks is essential. Tools like Brazil’s Rural Environmental Registry (Laudares et al. 2014) offer a legal basis for managing agricultural areas to minimize wildlife impacts (Orlowski and Nowak 2006). Municipal governments must also improve land-use planning to fulfill their responsibilities (Carvalho 2001). In this context, it is important that mitigation measures are incorporated and preserved on municipal roads.

Overall, our findings emphasize the critical need for targeted conservation measures and adaptive management strategies that consider the specific traits and behaviors of different mammal groups. By addressing landscape influences alongside road-specific features, mitigation efforts can more effectively balance biodiversity conservation with road safety.

5. Conclusions

The presence of various forest-dwelling, rare, and threatened species reinforces the significance of the Cantareira-Mantiqueira Corridor for medium and large mammal conservation. Generalist species face higher roadkill risks in pasture and agricultural matrices, while native vegetation positively influences roadkill rates for small home-range generalist mammals. On the Dom Pedro I Highway (SP-065), scale effects varied from 500 meters to 3,000 meters around roadkill sites, reflecting the biological traits of the functional groups analyzed. Mitigation measures should shift from traditional hotspot-focused approaches near native vegetation to encompass agricultural and open land-use matrices. In highly fragmented landscapes, where few native vegetation areas remain, many mammals use pastures and agricultural fields as both transit routes and habitats. Since our results show these matrices significantly contribute to roadkill, mitigation measures must address these land-use classes to enhance road safety and biodiversity conservation. Also, clear research questions must guide mitigation strategies, focusing on whether the goal is to reduce roadkill or mitigate barrier effects. These strategies should then target specific species or groups and be tailored to the surrounding landscape attributes. Future research should further investigate the relationship between roadkill and forest-dwelling mammal species. Specifically, studies could explore whether defaunation processes affect populations near roads. For Dom Pedro I, assessing potential barrier effects on G2 and G4 species would offer valuable insights into their movement and habitat use.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: Quantitative characterization of land-use and cover classes surrounding the Dom Pedro I highway (SP-065), Figure S1: Selected model for functional group G1 with a 500 m radius, where G1 represents small home-range mammals (<30.635 ha) commonly found in anthropic areas, Figure S2: Selected model for functional group G3 with a 3,000 m radius. G3 represents large home-range mammals (≥30.635 ha) commonly found in anthropic areas. The p-value for the pasture variable was > 0.05, Figure S3: Selected model for functional group G3 with a 6,000 m radius. G3 represents large home-range mammals (≥30.635 ha) commonly found in anthropic areas. The p-value for the pasture variable was > 0.05, Figure S4: Selected model for functional group G5 with a 3,000 m radius. G5 represents the capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris, Linnaeus 1766).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.R, S.R.F and F.A.A.; Methodology, S.R.F, A.L.-C.; Validation, S.R.F and A. L.-C.; Formal Analysis, A.L.-C. and F.A.A; Investigation, A.L.-C. and F.A.A; Resources, F.A.A; Data Curation, S.R.F and F.A.A; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, F.A.A and A.L.-C; Writing – Review & Editing, S.R.F and A. L.-C; Visualization, A. L.-C; Supervision, S.R.F; Project Administration, F.A.A.; Funding Acquisition, F.A.A. and M.C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We also thank to São Paulo State Environmental Company (CETESB) for providing roadkill data.

References

- Abra FD, Huijser MP, Magioli M, Bovo AAA, de Barros KMPM (2021) An estimate of wild mammal roadkill in São Paulo state, Brazil. Heliyon 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Abra FD, Canena A da C, Garbino GST, Medici EP (2020) Use of unfenced highway underpasses by lowland tapirs and other medium and large mammals in central-western Brazil. Perspect Ecol Conserv 18(4). 247-256. [CrossRef]

- Abra FD, Granziera BM, Huijser MP, Ferraz KMPMDB, Haddad CM et al (2019) Pay or prevent? Human safety, costs to society and legal perspectives on animal-vehicle collisions in São Paulo state, Brazil. Plos One 14(4). [CrossRef]

- Abra FD, Huijser MP, Pereira CS, Ferraz KM (2018) How reliable are your data? Verifying species identification of road-killed mammals recorded by road maintenance personnel in São Paulo State, Brazil. Biol Conserv 225. 42-52. [CrossRef]

- Abreu EF, Casali D, Costa-Araújo R, Garbino GST, Libardi GS et al (2024) Lista de Mamíferos do Brasil, versão 2023-1. Comitê de Taxonomia da Sociedade Brasileira de Mastozoologia (CTSBMz). https://www.sbmz.org/mamiferos-do-brasil/. Accessed 01 June 2024.

- ARTESP (2022) Agência de Transportes do Estado de São Paulo. Rodovias e concessionárias. http://www.artesp.sp.gov.br. Accessed 7 Sept 2022.

- Ascensão F, Yogui D, Alves M, Medici EP, Desbiez A (2019) Predicting spatiotemporal patterns of road mortality for medium-large mammals. J Environ Manag 248. [CrossRef]

- Ascensão F, Desbiez AL, Medici EP, Bager A (2017) Spatial patterns of road mortality of medium–large mammals in Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Wildlife Res 44(2): 135-146. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo FC, Lemos FG, Almeida L, Campos C, Beisiegel B et al (2013) Avaliação do risco de extinção da Onça-parda Puma concolor (Linnaeus, 1771) no Brasil. BioBrasil 3(1): 107-121. [CrossRef]

- Benavides C, Arce A, Pacheco LF (2017) Home range and habitat use by pacas in a montane tropical forest in Bolivia. Acta Amazonica 47: 227-236. [CrossRef]

- Boscolo D, Tokumoto PM, Ferreira PA, Ribeiro JW, dos Santos JS (2017) Positive responses of flower visiting bees to landscape heterogeneity depend on functional connectivity levels. Perspect Ecol Conserv 15(1): 18-24. [CrossRef]

- Broekman MJE, Hoeks S, Freriks R, Langendoen MM, Runge KM et al (2023) HomeRange: A global database of mammalian home ranges. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 32(2): 198–205. [CrossRef]

- Bueno C, Sousa COM, Freitas SR (2015) Habitat or matrix: which is more relevant to predict road-kill of vertebrates? Braz J Biol 75: 228-238. [CrossRef]

- Bueno C, Faustino MT, Freitas SR (2013) Influence of landscape characteristics on capybara road-kill on highway BR-040, southeastern Brazil. Oecol Aust 17(2): 130-137. [CrossRef]

- Cáceres NC (2011) Biological characteristics influence mammal road kill in an Atlantic Forest – Cerrado interface in south-western Brazil. Ital J Zool 78(3): 379-389. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho SND (2001) Estatuto da cidade: aspectos políticos e técnicos do plano diretor. São Paulo Perspect 15: 130-135. [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira RC, Leonard PB, da Silva LG, Bager A, Clevenger AP et al (2021) Potential movement corridors and high road-kill likelihood do not spatially coincide for felids in Brazil: Implications for road mitigation. Environ Manag 67(2): 412-423. [CrossRef]

- CETESB (2018) Companhia Ambiental do Estado de São Paulo. Decisão de Diretoria n. 141/2018/I. https://cetesb.sp.gov.br/decisoes-de-diretoria/. Accessed 25 Ago 2022.

- Ciocheti G (2014) Spatial and temporal influences of road duplication on wildlife road kill using habitat suitability models. Thesis, Universidade Federal de São Carlos.

- Cirino DW, Lupinetti-Cunha A, Freitas CH, Freitas SR (2022) Do the roadkills of different mammal species respond the same way to habitat and matrix? Nat Conserv 47: 65-85. [CrossRef]

- Coelho IP, Teixeira FZ, Colombo P, Coelho AVP, Kindel A (2012) Anuran road-kills neighboring a peri-urban reserve in the Atlantic Forest, Brazil. J Environ Manag 112: 17-26. [CrossRef]

- CRB (2024) Concessionária Rota das Bandeiras. Informações sobre a Dom Pedro I (SP-065). www.rotadasbandeiras.com.br. Accessed 30 May 2024.

- DER (2024) Departamento de Estradas de Rodagem do Estado de São Paulo. Malha Rodoviária do Estado de São Paulo. http://www.der.sp.gov.br. Accessed 30 Mai 2024.

- Dias DDM., Almeida MDOS, Araújo-Piovezan TGD, Dantas JO (2019) Spatiotemporal ecology of two neotropical herbivorous mammals. Pap Avulsos Zoo 59: e20195910. [CrossRef]

- Dornelles SDS (2015) Impactos da duplicação de rodovias: variação da mortalidade de fauna na BR 101 Sul. São Carlos. Thesis, Universidade Federal de São Carlos.

- Fahrig L (2007) Non-optimal animal movement in human-altered landscapes. Funct Ecol 21(6): 1003-1015. [CrossRef]

- Feijó A (2020). Dasypus septemcinctus (Cingulata: Dasypodidae). Mamm Species 52(987): 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Felix GA, Almeida Paz ICL, Piovezan U, Garcia RG, Lima KAO et al (2014) Feeding behavior and crop damage caused by capybaras (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) in an agricultural landscape. Braz J Biol 74: 779-786. [CrossRef]

- Ferraz KMPB, Ferraz SFB, Moreira JR, Couto HTZ, Verdade LM (2007) Capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) distribution in agroecosystems: a cross-scale habitat analysis. J Biogeogr 34(2): 223-230. [CrossRef]

- Freitas SR, Barszcz LB (2015) A perspectiva da mídia online sobre os acidentes entre veículos e animais em rodovias brasileiras: uma questão de segurança? Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente 2015, 33: 261-276. [CrossRef]

- Freitas SR, Oliveira AN, Ciocheti G, Vieira MV, Matos DMS (2015) How landscape features influence road-kill of three species of mammals in the Brazilian savanna? Oecol Aust 18: 35–45. [CrossRef]

- Freitas SR, Cláudia OMS, Bueno C. Effects of landscape characteristics on roadkill of mammals, birds and reptiles in a highway crossing the Atlantic Forest in southeastern Brazil. International Conference on Ecology and Transportation (ICOET) 2013. Arizona.

- Galetti M, Carmignotto AP, Percequillo AR, Santos MCO, Ferraz KMPMBF et al (2022) Mammals in São Paulo State: diversity, distribution, ecology, and conservation. Biota Neotrop v22(spe): e20221363. [CrossRef]

- Hilasaca LMH, Gaspar LP, Ribeiro MC, Minghim R (2021) Visualization and categorization of ecological acoustic events based on discriminant features. Ecol Indic 126: 107316. [CrossRef]

- ICMBio (2024) Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade. Salve. https://salve.icmbio.gov.br/. Accessed 3 Sept 2024.

- IUCN (2024) International Union for Conservation of Nature. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species – Habitats Classification Scheme (Version 3.1). https://www.iucnredlist.org/resources/habitat-classification-scheme. Accessed 27 May 2024.

- IUCN (2023) International Union for Conservation of Nature. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. https://www.iucnredlist.org/. Accessed 22 Jan 2023.

- Jackson HB, Fahrig L (2012) What size is a biologically relevant landscape? Landsc Ecol 27: 929-941. [CrossRef]

- Jamhuri J, Edinoor MA, Kamarudin N, Lechner AM, Ashton-Butt A et al (2020) Higher mortality rates for large-and medium-sized mammals on plantation roads compared to highways in Peninsular Malaysia. Ecol Evol 10(21): 12049-12058. [CrossRef]

- Laudares SSA, da Silva KG, Borges LAC (2014) Cadastro Ambiental Rural: uma análise da nova ferramenta para regularização ambiental no Brasil. Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente 31. [CrossRef]

- MapBiomas Project (2021) Collection 3.0 of Annual Series of Land Use and Land Cover Maps of Brazil. http://mapbiomas.org/map#coverage. Accessed 20 May 2024.

- Martins T, Freitas SR, Semensatto Junior DL, Hardt E (2024a) The influence of proximity with riparian forests and the distance from urban areas on roadkills of vertebrates in a fragmented Brazilian savanna area. Austral Ecol 49(1): e13342. [CrossRef]

- Martins T, Freitas SR, Lupinetti-Cunha A, Semensatto D, Hardt E (2024b) Combining roadkill hotspots and landscape features to guide mitigation measures on highways. J Nat Conserv 82: 126738. [CrossRef]

- Medrano-Vizcaíno P, Grilo C, Brito-Zapata D, González-Suárez M (2023) Landscape and road features linked to wildlife mortality in the Amazon. Biodivers Conserv 32(13): 4337-4352. [CrossRef]

- Medrano-Vizcaíno P, Grilo C, Silva Pinto FA, Carvalho WD, Melinski RD et al (2022) Roadkill patterns in Latin American birds and mammals. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 00: 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira TG, Tortato MA, Silveira L, Kasper CB, Mazim FB et al (2010) Ocelot ecology and its effect on the small-felid guild in the lowland neotropics. In: Macdonald WD, Loveridge AJ (eds) Biology and conservation of the wild felids, Oxford University Press, New York, pp 559–580.

- Orlowski G, Nowak L (2006) Factors influencing mammal roadkills in the agricultural landscape of south-western Poland. Pol J Ecol 54(2): 283-294.

- Paglia AP, Fonseca GAB, Rylands AB, Herrmann G, Aguiar LMS et al (2012) Annotated checklist of Brazilian mammals 2nd Edition. Conservation International, Arlington.

- Pinto FAS, Cirino DW, Cerqueira RC, Rosa C, Freitas SR (2022) How Many Mammals Are Killed on Brazilian Roads? Assessing Impacts and Conservation Implications. Diversity 14(10): 835. [CrossRef]

- Pinto FAS, Clevenger AP, Grilo C (2020) Effects of roads on terrestrial vertebrate species in Latin America. EIA Review 81: 106337. [CrossRef]

- Poessel SA, Burdett CL, Boydston EE, Lyren LM, Alonso RS et al (2014) Roads influence movement and home ranges of a fragmentation-sensitive carnivore, the bobcat, in an urban landscape. Biol Conserv 180: 224-232. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team (2024) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. www.R-project.org/. Accessed 25 Feb 2024.

- Regolin AL, Oliveira-Santos LG, Ribeiro MC, Bailey LL (2021) Habitat quality, not habitat amount, drives mammalian habitat use in the Brazilian Pantanal. Landsc Ecol 36(9): 2519–2533. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro MC, Metzger JP, Martensen AC, Ponzoni FJ, Hirota MM (2009) The Brazilian Atlantic Forest: how much is left, and how is the remaining forest distributed? Implications for conservation. Biol Conserv 142(6): 1141-1153. [CrossRef]

- Rosa CA, de Almeida Curi NH, Puertas F, Passamani M (2017) Alien terrestrial mammals in Brazil: current status and management. Biol Invasions 19: 2101-2123. [CrossRef]

- Rytwinski T, Soanes K, Jaeger JA, Fahrig L, Findlay CS et al (2016) How effective is road mitigation at reducing road-kill? A meta-analysis. PLoS one 11(11), e0166941. [CrossRef]

- Rytwinski T, Fahrig L (2012) Do species life history traits explain population responses to roads? A meta-analysis. Biol Conserv 147(1): 87-98. [CrossRef]

- Santos R, Shimabukuro A, Taili I, Muriel R, Lupinetti-Cunha A et al (2023) Mammalian Roadkill in a Semi-Arid Region of Brazil: Species, Landscape Patterns, Seasonality, and Hotspots. Diversity 15(6): 780. [CrossRef]

- Santos RAL, Ascensão F (2019) Assessing the effects of road type and position on the road on small mammal carcass persistence time. Eur J Wildl Res 65: 1-5. [CrossRef]

- São Paulo (2018) Decreto n° 63.853, de 27 de novembro de 2018. Assembleia Legislativa do Estado de São Paulo. www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/decreto/2018/decreto-63853-27.11.2018.html. Accessed 26 Jun 2024.

- Secco H, Farina LF, da Costa VO, Beiroz W, Guerreiro M et al (2024) Identifying roadkill hotspots for mammals in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest using a functional group approach. Environ Manag 73(2): 365-377. [CrossRef]

- Silva ACFB, De Menezes JFS, Santos LGRO (2022) Roadkill risk for capybaras in an urban environment. Landsc Urban Plan 222: 104398. [CrossRef]

- Silva GJC, Martins HEP, Neder Henrique D (2016) Investimentos em infraestrutura de transportes e desigualdades regionais no Brasil: uma análise dos impactos do Programa de Aceleração do Crescimento (PAC). J Polit Econ 36: 840-863. [CrossRef]

- Souza Jr CM, Shimbo JZ, Rosa MR, Parente LL, Alencar AA et al (2020) Reconstructing three decades of land use and land cover changes in brazilian biomes with landsat archive and earth engine. Remote Sens 12(17): 2735. [CrossRef]

- Taylor BD, Goldingay RL (2010) Roads and wildlife: impacts, mitigation and implications for wildlife management in Australia. Wildlife Res 37(4): 320-331. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira FZ, Kindel A, Hartz SM, Mitchell S, Fahrig L (2017) When road-kill hotspots do not indicate the best sites for road-kill mitigation. J Appl Ecol 54(5): 1544-1551. [CrossRef]

- Varela DM, Trovati RG, Guzmán KR, Rossi RV, Duarte JMB et al (2010) Red brocket deer Mazama americana (Erxleben 1777). Neotropical Cervidology, Biology and Medicine of Latin American Deer. FUNEP/IUCN, Jaboticabal/Gland, pp 151-159.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).