1. Introduction

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) or drones have expanded their applications in various sectors, including military operations, facility management, entertainment, and education, equipped with cameras and sensors. Among the types of UAVs used in academic and research settings, educational drones such as the CoDrone EDU are a good option due to their affordability, user-friendliness, and adaptability for experimental purposes. These platforms typically rely on one-to-one communication protocols, operating through dedicated radio frequency (RF) remote controllers. This configuration provides a simple, cost-effective solution for indoor flight experiments that do not require high-end specifications or complex control systems [

1]. For example, the CoDrone EDU provides support for individual operation, making it ideal for basic programming education and simple flight tasks.

The strategy implemented to achieve control of multiple drone missions involves the use of GCS configurations, which can range from simple operator interfaces to sophisticated control hubs with several components [

2]. In this paper, GCS is called Drone Control Station (DCS) and refers to the set of RF remote controls connected to a computer. This DCS plays a significant role in addressing the mission by serving as the main communication interface between human operators and the drone.

Recently, the interest in multiple drone missions has driven the need for scalable and synchronized control mechanisms [

3,

4], where ensuring reliable control and responsiveness between the drones is the goal [

5]. However, the simplicity of the CoDrone EDU creates crucial limitations because it has low communication abilities, where the remote control has a connection with an individual drone, making it difficult to use in a multi-drone mission. This constraint highlights the necessity for adaptable and scalable control architectures that are not only efficient but also customized to the capabilities of low-cost educational drones [

6].

To overcome the challenges of controlling multi-drone missions, this work adopts an object-oriented approach (OOA) to define and organize components. This simplifies the management of complex missions but also improves scalability, allowing for the integration of multiple behaviors and mission requirements. From this perspective, the yellow card detection scenario serves as a practical case study to test and compare control architectures for multi-drone coordination.

Integrating educational drones into multi-drone systems using existing architectures to support more synchronized and scalable operations, this work explores how control strategies can be effectively implemented despite the limitations imposed by low-resource environments, with two architectures for enabling coordinated control of multiple CoDrone EDU units: the strategies use native drone control software that operates within their built-in protocol. The first approach involves a DCS centralized control architecture that connects various drones to a single DCS via a USB hub. The second approach introduces a custom client-server control architecture, utilizing TCP/IP protocols to establish communication between the many DCS and the drones, thereby enabling a scalable multi-drone mission.

Flight tests were conducted using the CoDrone EDU to evaluate the proposed architectures. These experiments followed an object-oriented scenario in which key performance aspects, such as scalability, inspection coverage, and mission time, were measured. The findings of this study are relevant to environments where cost-efficiency, system simplicity, and accessibility are prioritized, offering insight into how lightweight control architectures can enhance the capabilities of educational drones in collaborative missions.

This work contributes by exploring and evaluating two distinct control architectures for coordinating multiple CoDrone EDU units. These approaches address the limitations of the default one-to-one drone control model that is commonly found in low-cost educational platforms. This study highlights the trade-offs between simplicity and scalability, demonstrating that even low-cost educational drones can successfully execute coordinated missions when paired with the appropriate communication strategy.

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents key concepts and background research,

Section 3 introduces related work, and

Section 4 describes the drone control station for multiple drone missions.

Section 5 presents the experimentation,

Section 6 opens the discussion, and Section 7 summarizes key research work with contributions.

2. Concept and Background

We describe important concepts in the following section to understand educational drones, drone control stations, and the multi-drone environment.

2.1. Educational Drone

Currently, a wide range of educational drones is available on the market, each offering different capabilities depending on specific learning goals. Examples include the DJI Tello EDU [

7], CoDrone EDU [

8], and the Crazyflie Drone Bundle [

9], all of which support programming in Python. These platforms are specifically designed for education [

10], enabling students to learn beginner programming concepts, develop problem-solving skills, and experiment with autonomous flight control. Their flexibility and programmability make them useful resources for classroom teaching and research applications related to swarm coordination, sensor integration, and basic autonomous behaviors.

CoDrone EDU

Drone developed by Robolink,

CoDrone EDU [

11], is a compact and programmable educational drone using languages such as Python through its dedicated CoDrone EDU library. Its affordability, simplicity, and easy learning tools make it ideal for educational purposes. The drone has a lightweight frame with four rotors, an integrated microcontroller, and sensors including a gyroscope, accelerometer, barometer, and infrared proximity detectors, as well as an RGB LED, a small speaker, and ports for expansion modules. Communication occurs over a 2.4 GHz RF link via a dedicated controller, meaning each drone can only connect to one controller at a time, cause challenges for multi-drone coordination.

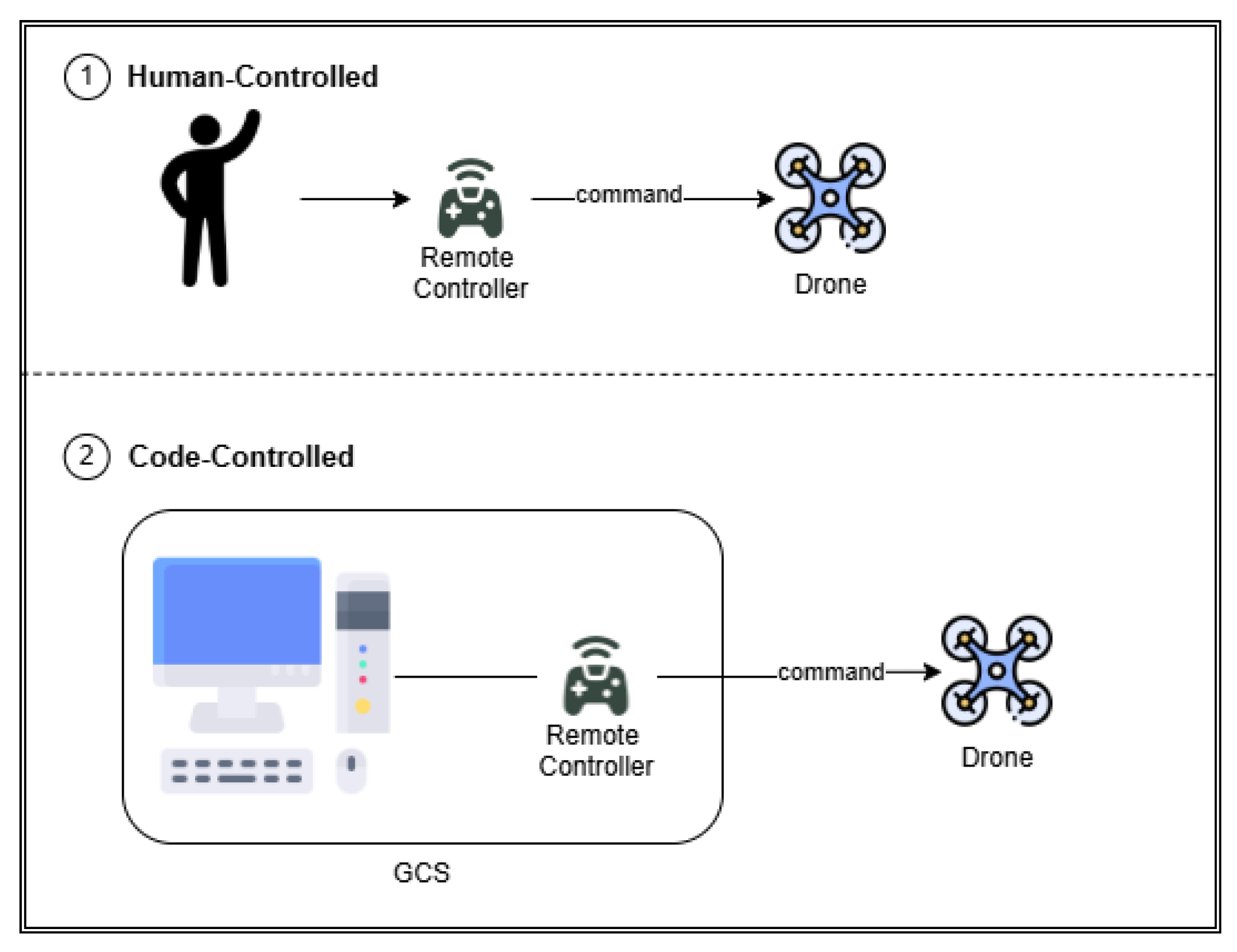

Figure 1 illustrates how the CoDrone EDU is controlled, where an individual can directly operate it with the remote control (Human-controlled) or through code (programming), and it is limited to connecting with just one drone (Code-controlled). Our research focuses on code-controlled.

2.2. Object-Oriented Approach

The Object-Oriented Approach (OOA) is a methodology for analyzing, designing, and programming systems based on objects [

12]. Within this principles, the definition of use cases capture functional requirements by describing how external actors interact with the system, while class diagrams provide visual representation of the system’s structure, showing classes, their attributes, methods, and relationships, thus creating a bridge between requirements and design.

In the context of multi-drone missions, OOA allows drones to be explored as an autonomous component that collaborates with entities within a broader framework. Each drone can be modeled as a class with attributes such as location, battery status, sensor data readings, and methods (take-off, land, scan area, data, etc.). Control architectures, such as centralized or client-server, can then be modeled as higher-level classes that coordinate the interaction. OOA principles facilitates scalability, as new drones or behaviors can be integrated without reconfiguring the whole system, and supports synchronization by treating mission objectives as shared objects accessed by multiple drones. In this way, the Object-Oriented Approach provides a systematic foundation for designing and evaluating control architectures that enable reliable and efficient multi-drone missions.

2.3. Drone Control Stations

The concept of a GCS serves as the main command and control for a UAV. The GCS serves as a link between the human operator and the drone, enabling control and mission management. GCSs may be stationary or mobile and usually feature software that enables operators to set mission parameters, oversee real-time drone performance, obtain and examine telemetry data, and control payload systems if necessary. The complexity of a GCS can differ significantly according to its intended use [

13]. In multi-drone settings, the GCS needs to manage multiple communication channels at once, coordinate command distributions, and simultaneously process telemetry from various sources.

GCSs are essential to enhancing the reliability, efficiency, and safety of UAV missions, especially those that engage multiple drones with restricted onboard autonomy. Following the basic GCS configuration, this paper refers to the DCS as a set of remote controls that are connected to an individual drone via radio frequency and linked via USB to a computer.

3. Related work

In academic and educational field, research has widely used the UAVs into the multiple drone systems due to their flexibility in programming, their safety, affordability, flexibility and appropriateness. As the studies in [

14] shows the use of educational drone like Tello EDU, for planning of collaborative group flights that are helpful in prototyping of hardware and software. It demonstrates their ability to be used in secure tasks and classroom or laboratory settings. The study shows that the cost-effective drones help to carry the collaborative mission in restricted and supervised environment making them useful in research projects and collective learnings. Despite, the cost effectiveness Tello EDU gives the better communication options for control flexibility, Wi-fi capabilities and SDK integration. However, CoDrone EDU only uses the Radio frequency (RF) for communication that gives the constraints communication environment as compare to that of Tello EDU but it remains useful for experimentation and training especially in classroom environment and educational settings where its security, affordability and ease to use are important factors.

The study in [

15] gives the analysis between contemporary mobile network-driven interactions including the 5G and LTE, and conventional RF-based communications. Greater coverage and fast data speed are offered by the mobile network’s communication. But some draw backs are also affiliated with these networks which include the difficulty of sustainable communication due to increasing interference carry out by the line-of sight transmission. On the other hand, traditional radio frequency communication, used mainly in educational drones gives the low latency and simple implementation with stable connection in restricted environment that make it better and practical option for short range and indoor missions. For small-sized multiple drone platforms like the ones assessed in this work, RF communication is yet dependable considering its short range and sensitivity to signal destruction in more complicated scenarios [

16]. It also emphasizes how crucial it is to choose suitable ways to communicate based on particular task specifications, operational settings, and system constraints. A GCS program for multiple ground control systems and multiple drones collaboration is implemented in the work in [

17]. The paper specifically presents IP-based GCS-to-GCS control, which provides improved interaction possibilities. The study repots the importance of GCS for the drone management and remotely piloted aircraft systems (RPAS) these study shows the need of DCS systems as an adaptable, effective and scalable in order meet the requirements of the hardware constrains and operational needs.

In conclusion, the previous research works show that the adaptable communication frameworks and strong design of GCS are important for the successful collaboration of multi-UAV systems. Our proposed study focuses on the using these techniques for the educational systems with the restricted radio frequency communication and onboard processing ability. Therefore, the previous studies illustrate the importance of the robust GCS design and flexible communication frameworks to enable the effective coordination in multi-UAV systems. These findings give the strong foundation for our proposed investigation, which focuses on enhancing the concept of the educational platforms with restricted RF communication and limited onboard computational resources.

Drone Control Station for Multiple Drone Missions

The Drone Control Station (DCS) manages the control of multiple drones. The DCS consists of hardware and software, where the missions are defined and the drone's remote control establishes the connection with the drone. For drones with limited communication skills, the DCS needs to design and implement physical and software strategies to control multiple drones. The following sections present key processes, ideas, and models for developing DCS.

3.1. Development of Drone Control System: Overall Process

Using an OOA allows the organization of multi-drone mission control into well-structured components, separating drone-specific functions, mission logic, and control architecture.

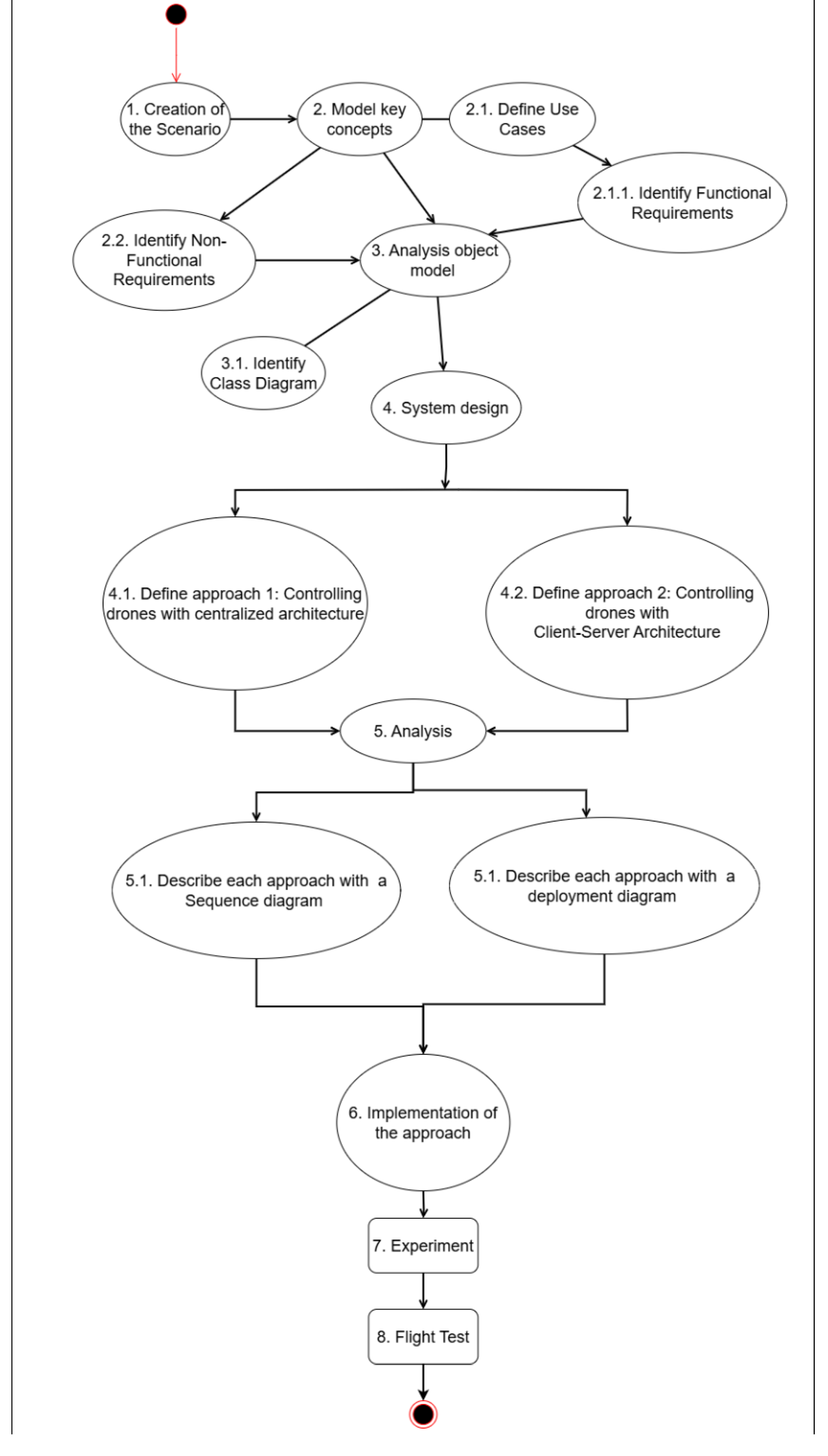

Figure 2 illustrates the process followed under OOA strategies. It begins with the creation of the scenario, the modeling of key concepts, and the definition of use cases, which serve to identify both functional requirements (FRs) and non-functional requirements (NFRs). Based on this analysis, an object model is derived, which leads to the development of a class diagram and subsequent system design. Finally, alternative control approaches are proposed and analyzed, paving the way for their implementation, experimentation, and validation through flight tests.

3.2. DCS Requirements

3.2.1. A Scenario for DCS Use

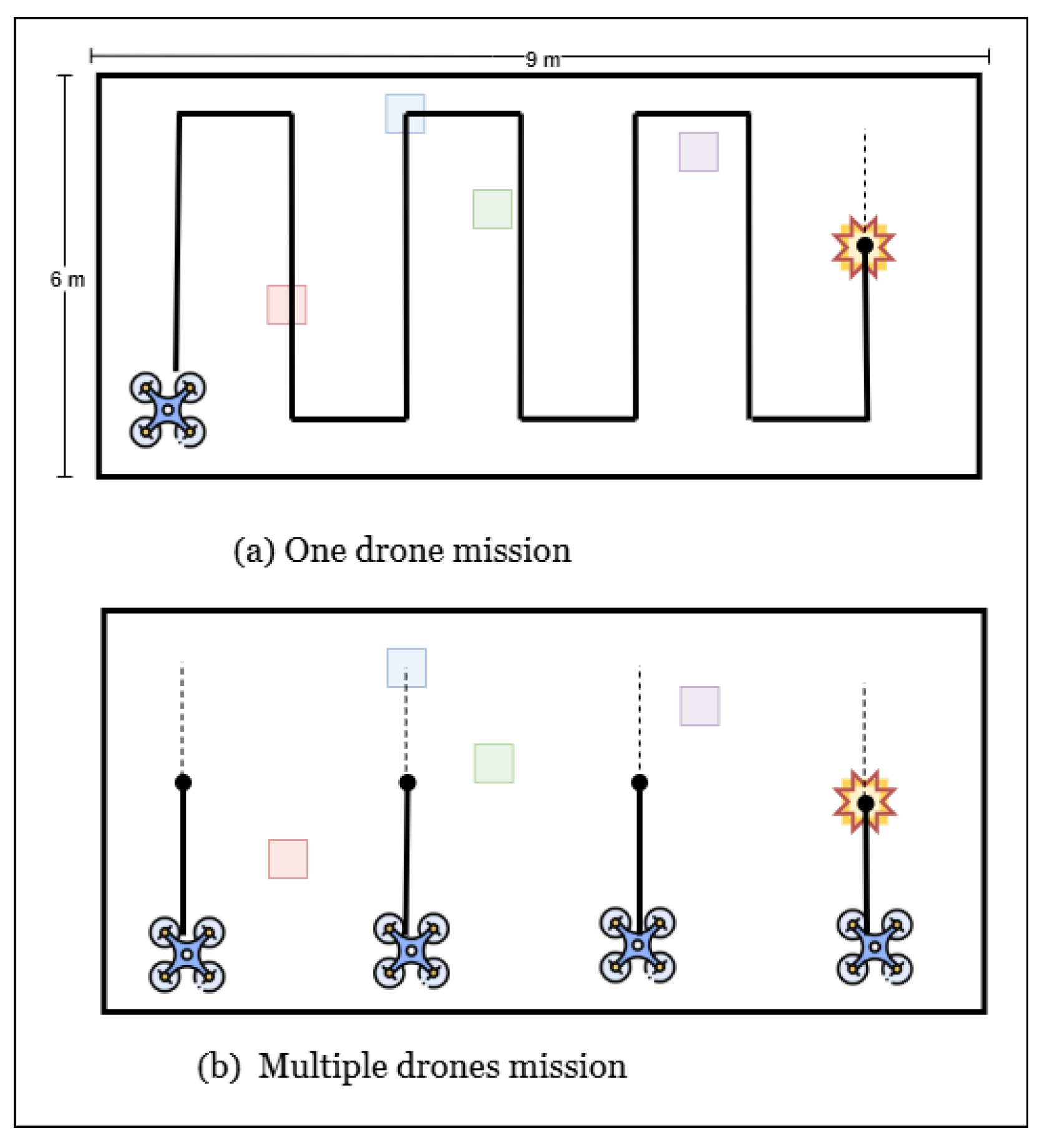

As part of a school study, a team of students uses drones to locate a yellow card that has been positioned on the classroom ground. The goal is to do the work as quickly as possible. The Drone Control System (DCS) and the actual drones are the two primary parts of the system. While each unmanned aircraft follows flight patterns and detects objects, the DCS is in charge of mission organizing, coordinating, and communication. Juan is the main drone operator; he uses only one drone to carry the flight test. He gives the mission commands and starts the mission flight through the DCS that links with the drone controller interface. During flight operation, he observes that the sensor of the drones can detect the limited range that requires the shorter spacing for complete coverage that cause increase in the mission time. To optimize performance, he configures multiple drones through the DCS, assigning each one a coordinated flight path that together covers the entire classroom, reducing overlap or blind spots, as shown in

Figure 3. Once one of the drones detects the yellow card, all drones automatically halt their missions and proceed to land. The drone that identifies the card emits an audible alert, signaling the successful completion of the search.

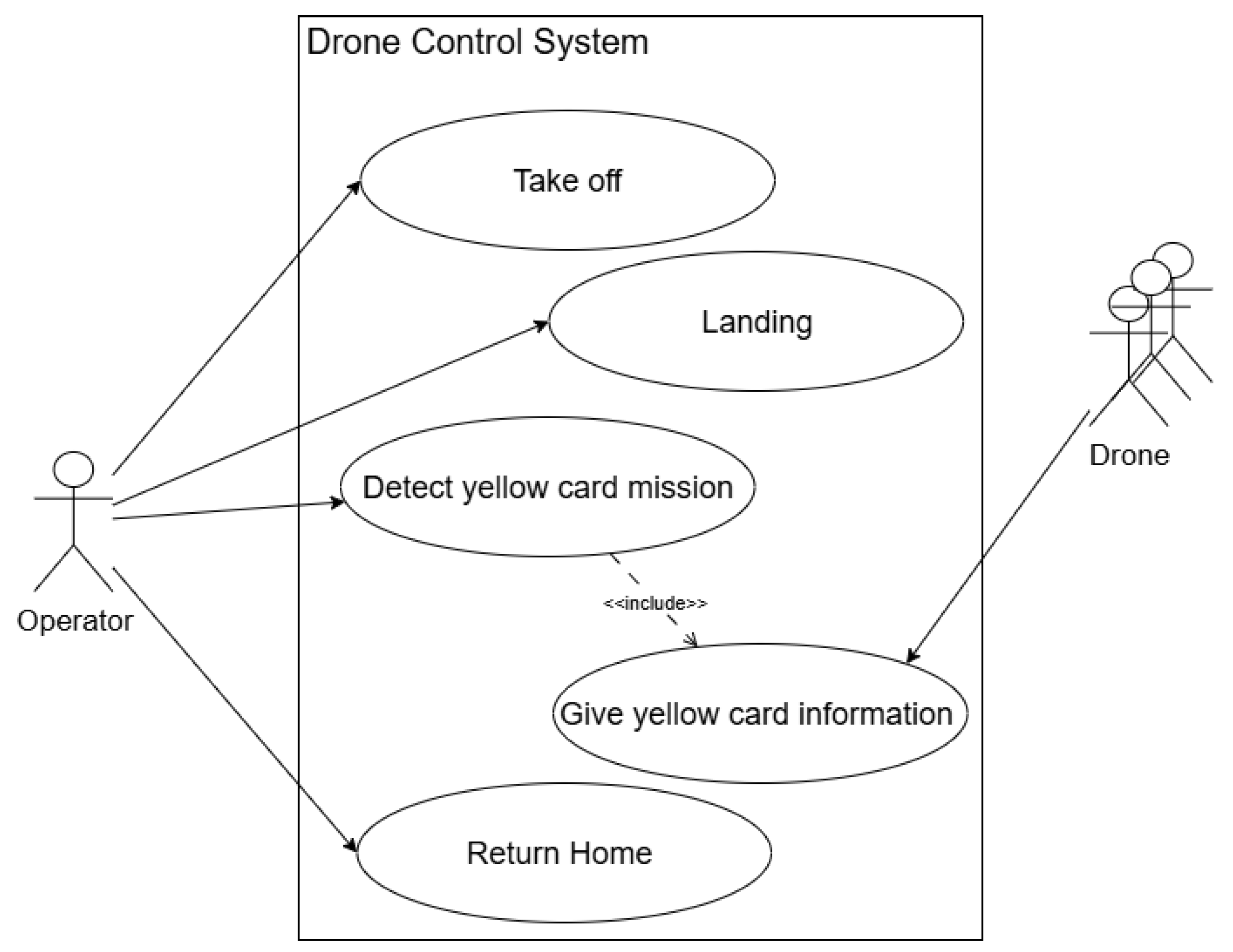

3.2.2. Modeling Use Case

The proposed scenario is structured into a use case diagram, where the systems involved are DCS and the drone, and the principal actor is the operator. We describe one use case,

Detect the yellow card mission, shown in

Figure 4.

In the use case diagram, we select the case of recognition of colored cards and then format it in detail in

Table 1.

3.2.3. Identify Functional Requirements (FRs) and Non-Functional Requirements (NFRs)

In this section, and with the support of use case modeling, the following functional and non-functional requirements are proposed as essential elements to be included in the control architectures. These requirements, which aim to ensure both the effectiveness and efficiency of multi-drone missions, are summarized in

Table 2.

3.3. Modeling Class Diagram

In this section, we model the system structure through a high-level diagram and a class diagram, which captures the essential components and their interactions within the multi-drone control architecture.

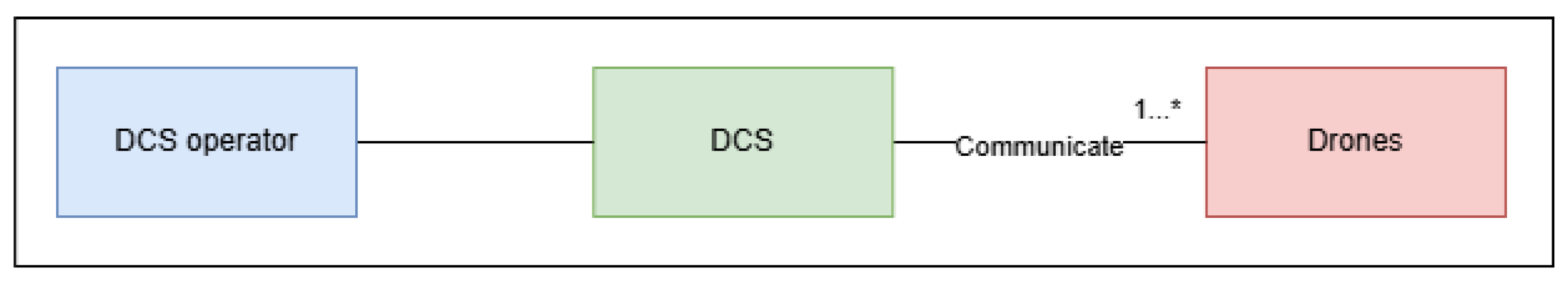

The high-level diagram shown in

Figure 5 illustrates the main components of the system: DCS operator, DCS, which is the control station, and the drones.

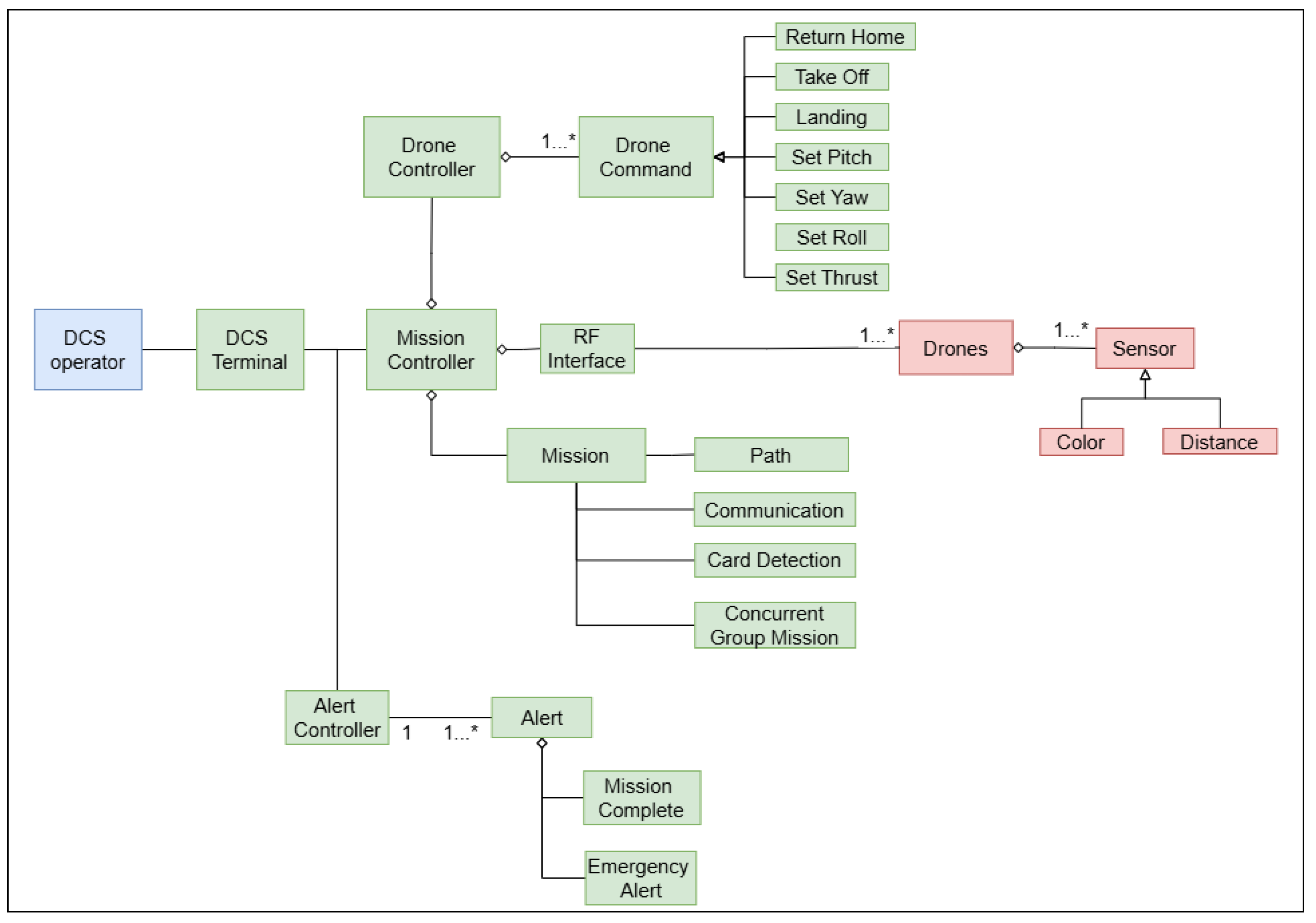

Figure 6 presents essential concepts and their relationships among the DCS modules in a class diagram, including the mission controller with the mission components as the path, communication, card detection, and concurrent group mission, drone controller with operational commands, and alert controller, to illustrate the control hierarchy and information flow during drone mission execution.

Also, in

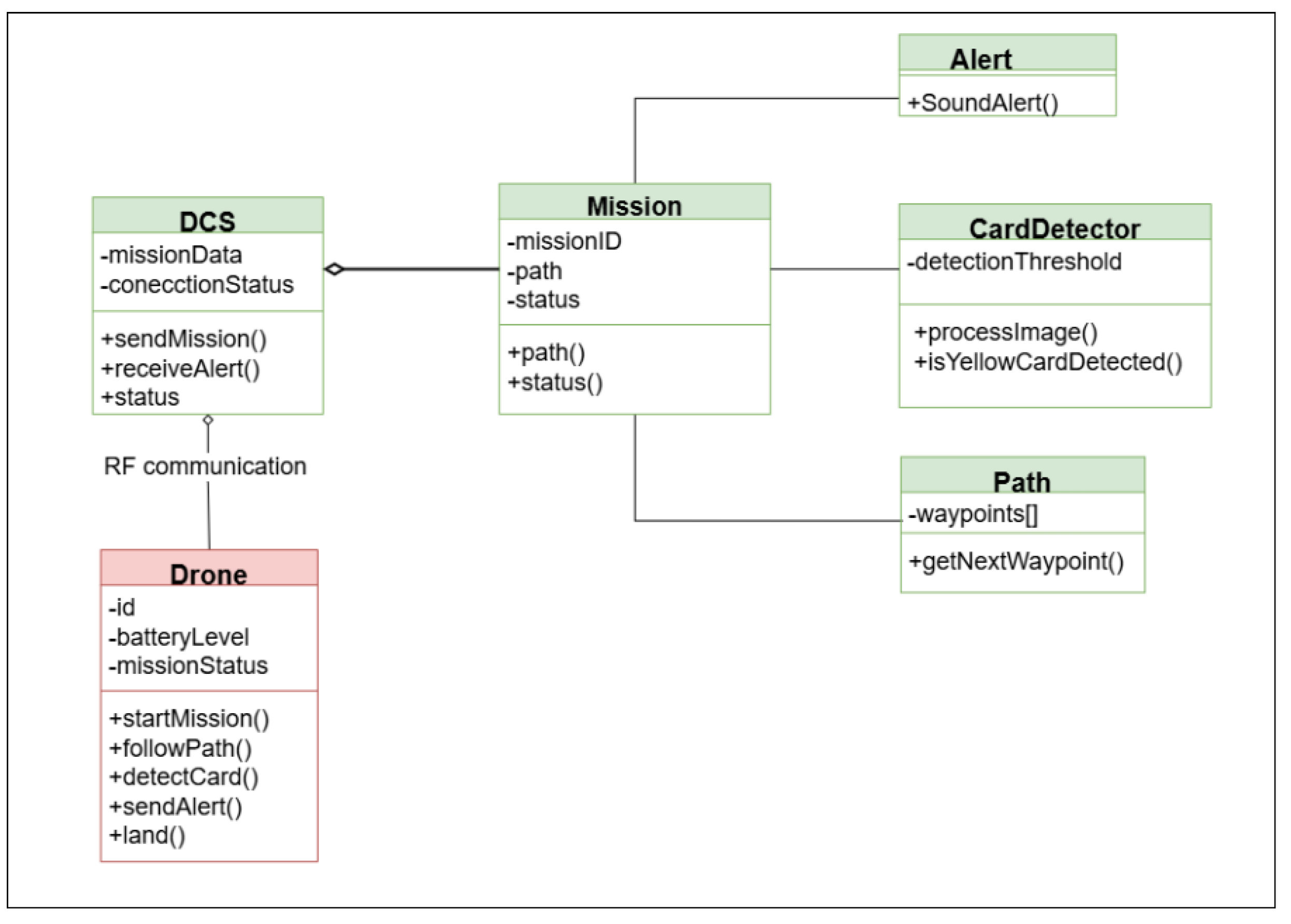

Figure 7, the class diagram of the multi-drone mission control defines the detailed system components, such as the DCS, Drone, and Mission, with components as Path, CardDetector, and Alert, and their relationships. The diagram shows how the DCS composes and sends missions to the Drone, how the Drone executes navigation and detection functions through its subsystems, and how alerts are generated and communicated back to the DCS. The diagram offers a detailed description that connects functional requirements to the system’s object-oriented architecture by outlining attributes, methods, and associations.

3.4. DCS Architecture

3.4.1. Exploring Architectures to Control Multiple Drones

A contrast analysis of many well-known frameworks was carried out in order to assess suitable management structures for managing numerous educational drones, taking into consideration variables like flexibility, degree of complexity, price, and suitability for low-resource learning contexts (refer to

Table 3). Evaluation of potential drone control strategies and justification for choosing one over another in multi-drone settings. These architectures include One-to-One RF Communication, peer-to-peer (P2P) exchange of information, Mesh Network Architecture [

18], Client-Server Architecture over TCP/IP, Peer-to-Peer (P2P) communication, Cloud-Based Communication [

19], and Centralized with a USB Hub.

Due to its limitations of scalability and inter-drone communication, which results in a high instructional burden, the One-to-One RF Communication approach, which is frequently used in educational drones, was not chosen. In a similarly, Mesh Network and P2P Architectures were found inappropriate for educational contexts because of their degree of complexity in terms of both hardware and software, which is not facilitated by simple drone platforms. Cloud-based Communication [

20] was excluded due to its reliance on internet connectivity and concerns about latency, which compromise real-time responsiveness.

In contrast, Client-Server Architecture over TCP/IP was selected for its scalability and support for synchronized multi-drone control through common networking setups. Additionally, the Centralized DCS with USB Hub configuration was chosen for its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and feasibility in classrooms, despite limitations in dynamic task flexibility due to port constraints.

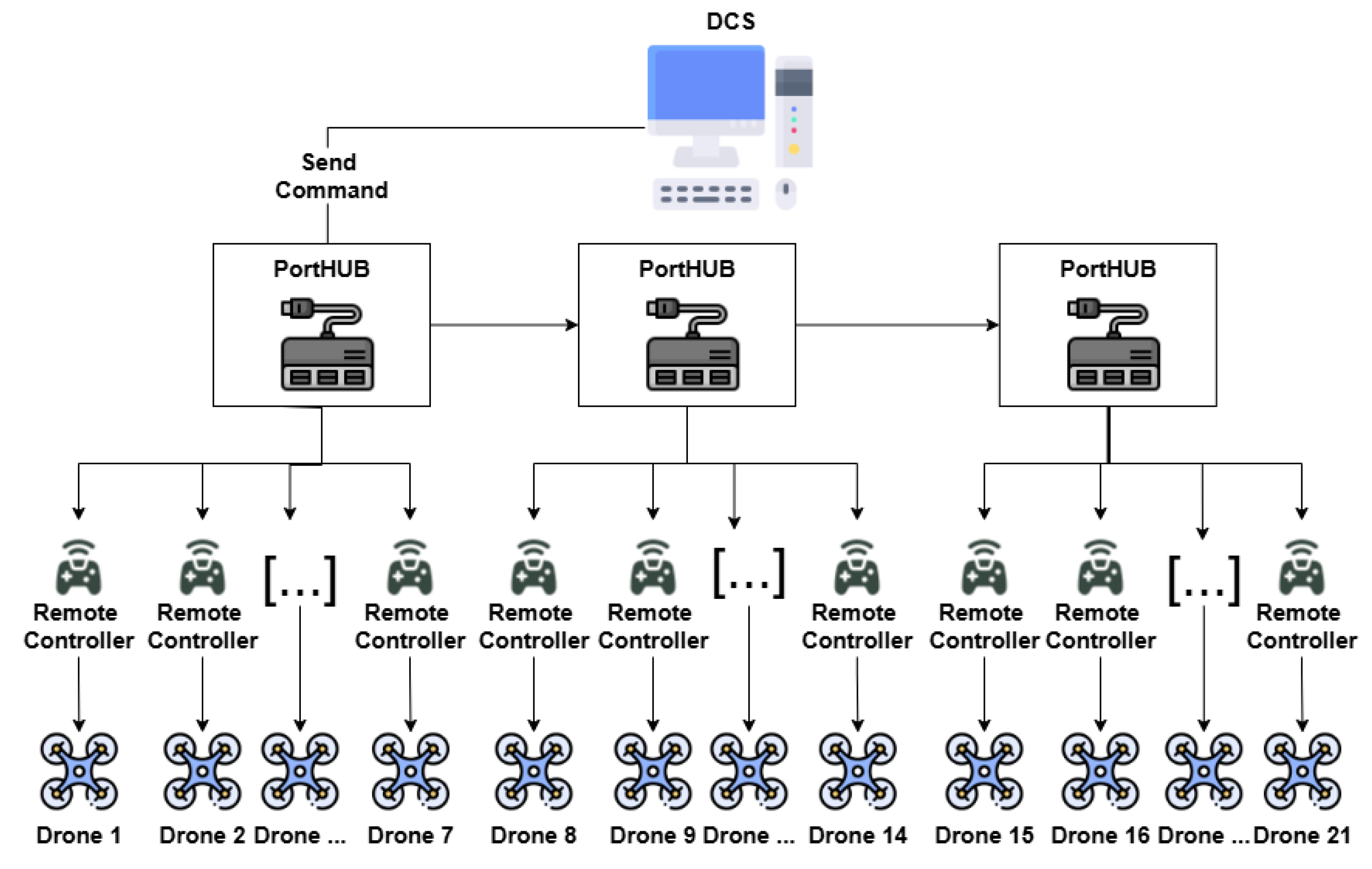

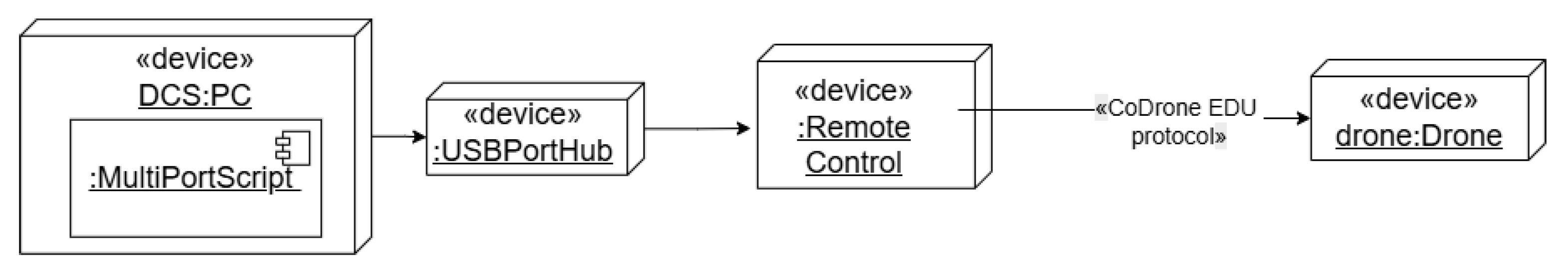

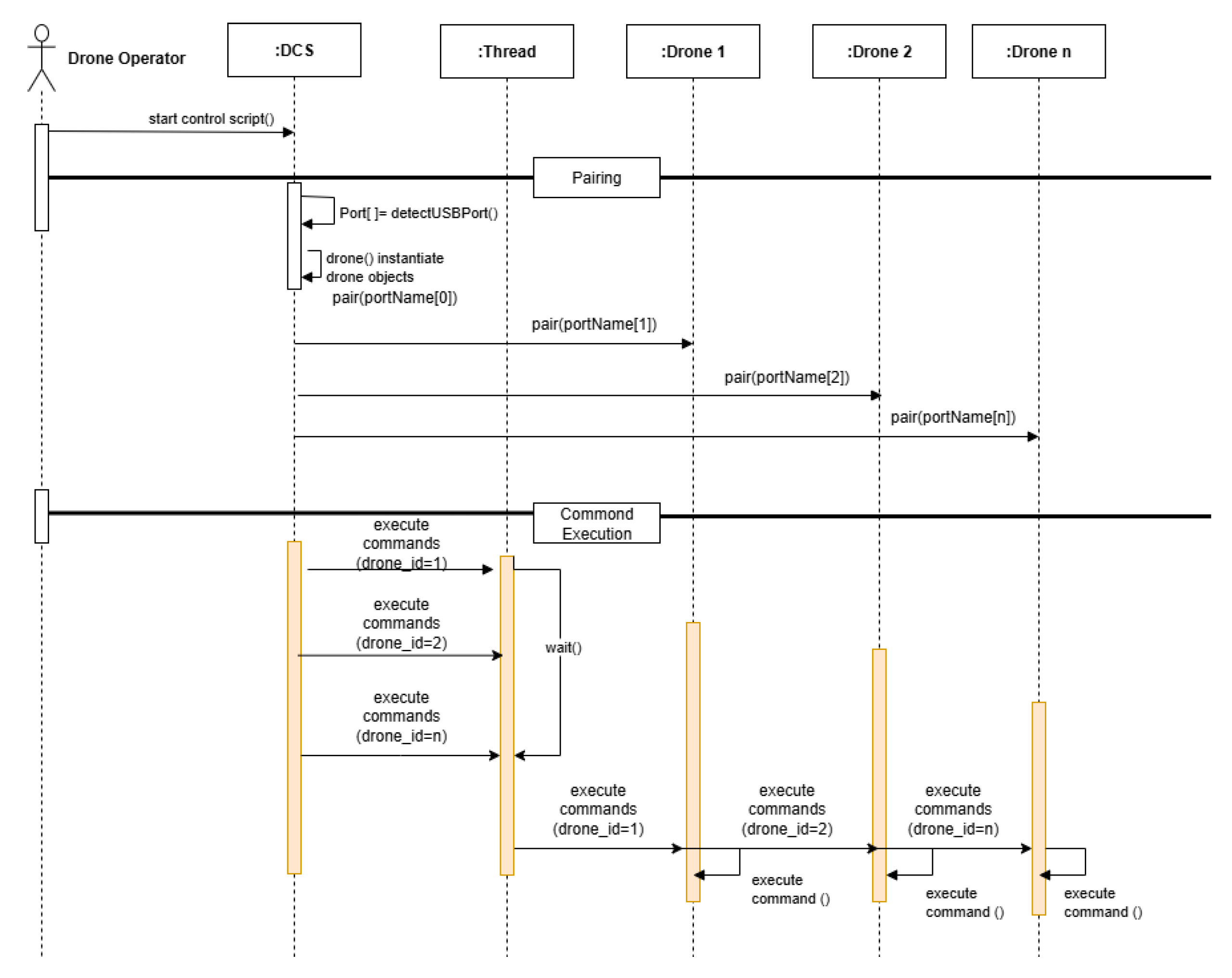

3.4.2. Controlling Drones with Centralized Architecture

In this approach, every drone receives instructions from the main DCS via a centralized Python program that uses the thread-based package and the CoDrone EDU library. The software program prepares for each drone to get the command and finish a coordinated operation. With the aid of a USB hub, drone recognition and operations are controlled according to the particular USB port that each controller for the drone is linked to. Although this configuration makes it possible to control several drones at once, it is inevitably limited by the physical constraints of the available USB ports. The DCS transmits control commands to each drone connected via a USB port hub, enabling the connection of multiple drones, as shown in

Figure 8.

Centralized architecture in

Figure 9 offers a straightforward implementation and maintains full compatibility with the existing CoDrone EDU programming framework. The main DCS executes a centralized Python script that leverages the CoDrone EDU library to issue commands to each drone using the threading package. The program waits until every drone receives the command and completes a synchronized mission. Drone identification and control are managed based on the specific USB port to which each remote controller is connected, facilitated by the use of a USB hub. While this setup enables simultaneous management of multiple drones, it is inherently constrained by the physical limitations of available USB ports.

Following the Object-Oriented Approach,

Figure 10 illustrates the deployment diagram, showing the main DCS and the connections of multiple drones, including the one-to-many multiplicity that enables the DCS to interface with multiple drone units simultaneously.

One benefit of the centralized architecture is that it requires little alteration to the current CoDrone EDU configuration, enabling it to be simple to use and operate. Additionally, it has a lesser degree of complexities, making it especially appropriate for students at entry level or in resource-constrained educational settings. However, the range of RF remote controllers and USB ports that are available may restrict the total amount of drones that may be commanded at once using this approach. The sequence diagram in

Figure 11 shows the procedure that the DCS starts when the control script is run, which helps to clarify the commands that flow within the DCS and the drones. The first step in drone pairing is identifying the names of the USB ports that each drone is connected to. The sequential nature of the commands transmission, which transmits commands to the drone single at a time, reflects the inherent limitations of the centralized communication architecture.

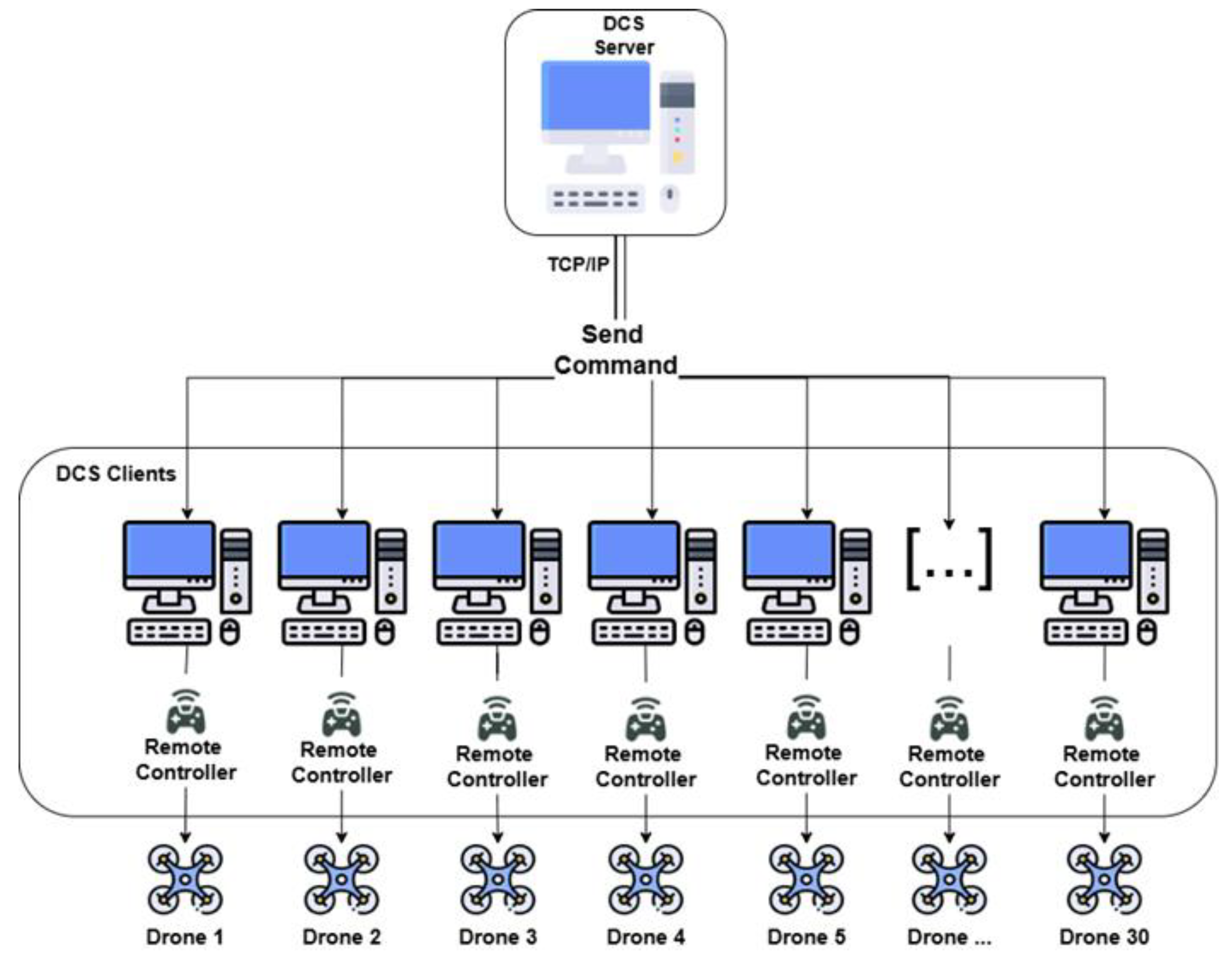

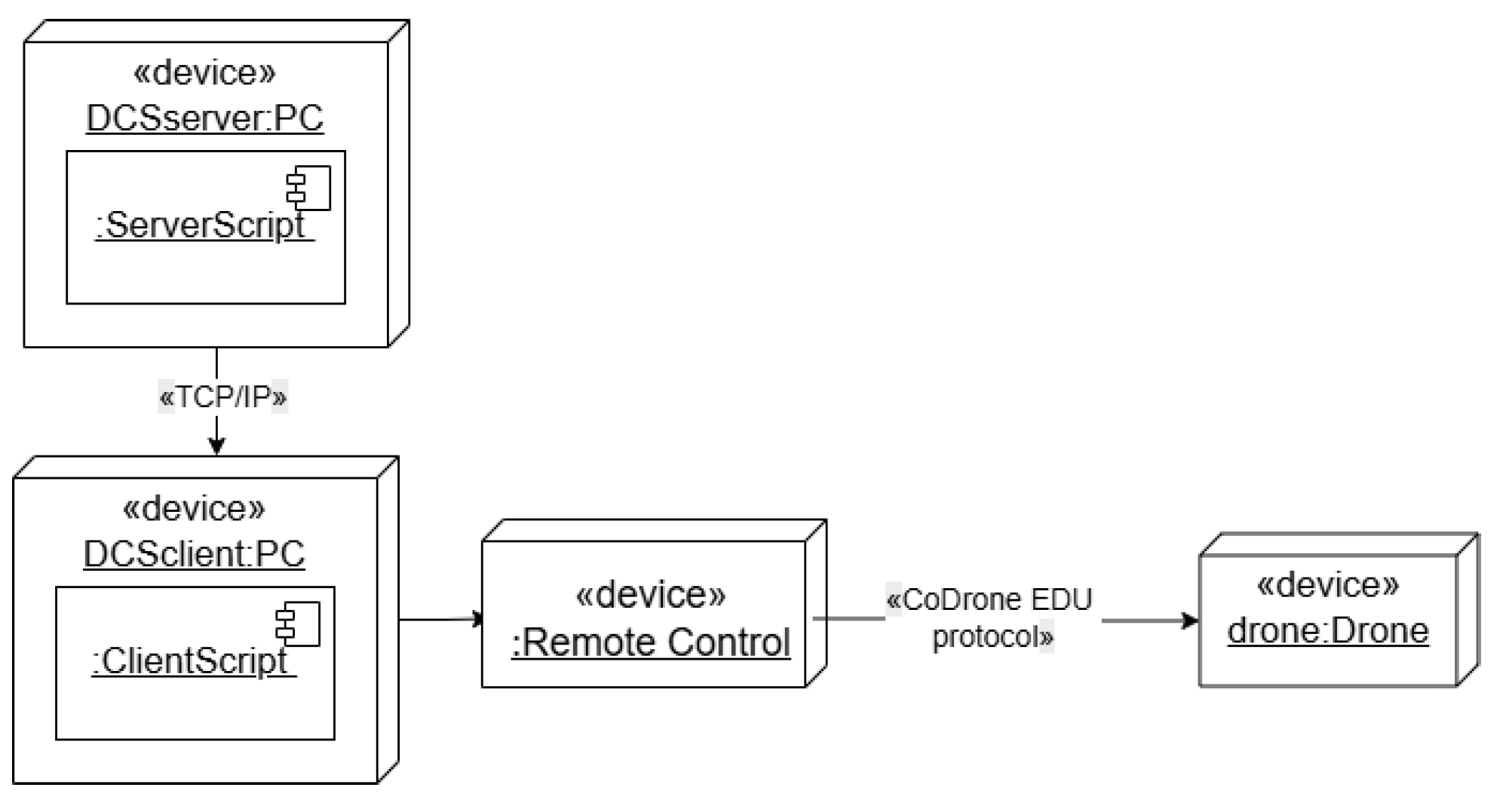

3.4.3. Controlling Drones with Client-Server Architecture

The client-server with TCP/IP over the internet connection is introduced for the Client-Server architecture. The socket programming is used to issue the commands from the server and execute by clients in a parallel way, which helps in synchronization of action among the multiple drones.

Figure 12 illustrates the structure of the Client-Server architecture.

TCP, an element of the transport protocol, is in charge of creating and preserving stable connections and making sure that data packets are sent in the right order and sequence. Additionally, by controlling, connecting, and navigating at the network layer, the Internet Protocol (IP) makes it easier for data to move between devices. Applications that need dependable and organized data exchange are especially well-suited for TCP/IP since it offers a strong and standardized foundation for client-server connection. Socket programming serves as the means of communication between central server and clients in the Client-Server architecture. Because socket programming is directly integrated with the TCP/IP protocol stack, it guarantees flexibility, real-time responsiveness, and precise control command transfer between each client node and the server.

The objective of the Client-Server design is to draw attention to the trade-offs between scalability and simplicity. Compared with traditional one-to-one systems, the Client-Server design is capable of supporting more drones due to its great scalability. Clients can be effortlessly handled from various physical places thanks to the utilization of a client and server approach, which enables remote or distribution control. The deployment diagram, which is intended to depict the physical components and interaction between the server and client GCS, is shown in

Figure 13 and adheres to the Object-Oriented Approach. The computers running the Python script are known as the GCS server and GCS client. They are connected to the internet and exchange data using TCP/IP protocols.

However, the Client-Server architecture also presents certain limitations. It requires network configuration, including software setup, which can increase system complexity. Moreover, the use of TCP/IP communication introduces slight latency due to the nature of packet transmission and data processing over the network.

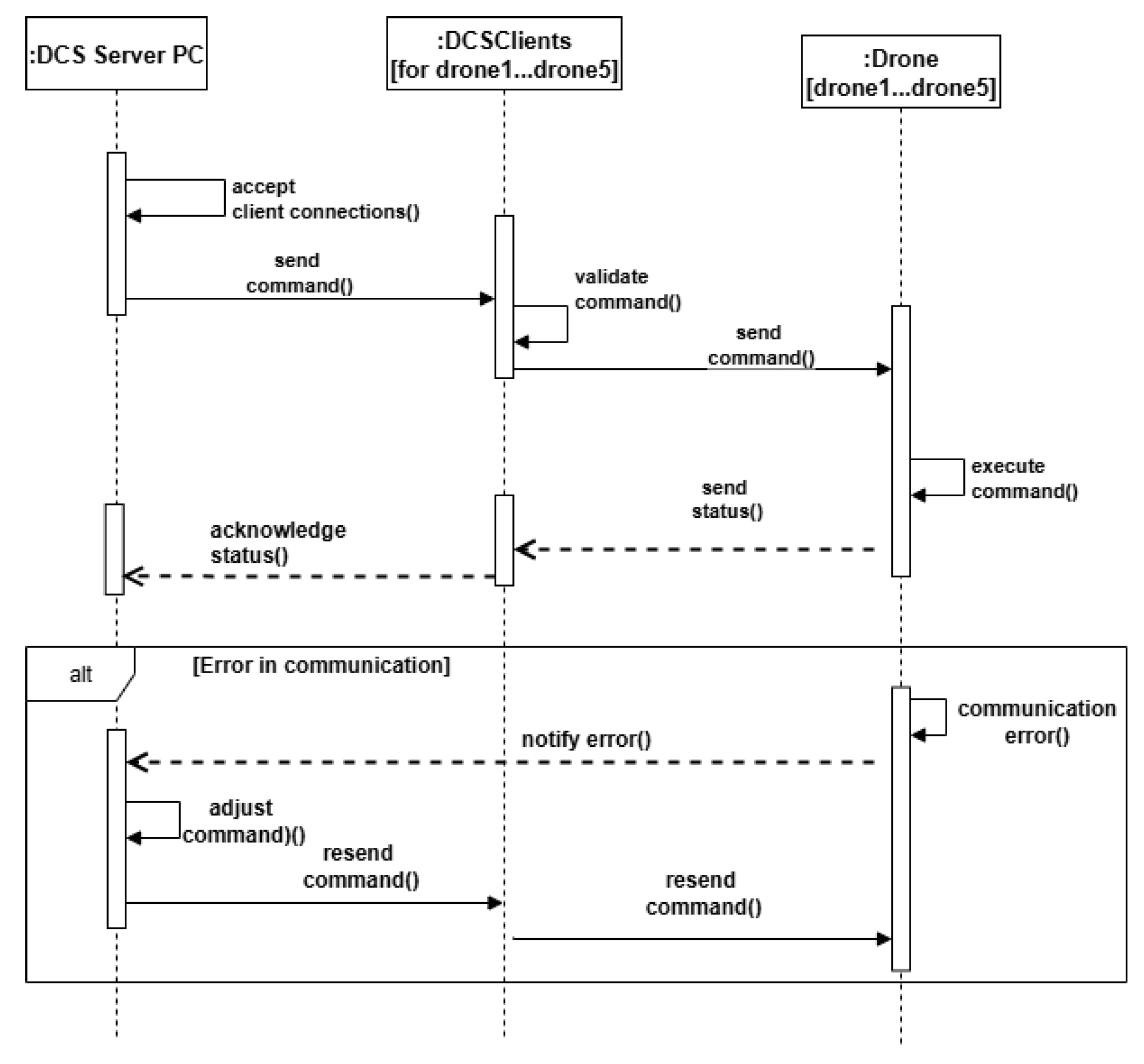

A sequence diagram represents the dynamic flow of commands from server-DCS to multiple clients-DCS, including the command delivery, receiving, and execution between entities, as shown in

Figure 14. The sequences include the initiation of the command by the server DCS, its validation, and execution by the drones. The diagram shows the messages' order and the system's synchronized operations.

4. Experimentation

The aim is to see whether these control architectures can provide the feasible and practical alternative for the operations of multiple drone environment in limited (restricted) resources environment or in academic or educational settings.

4.1. Experimental Environment

Experimental setups were conducted to evaluate and compare the proposed control architectures for multi-drone coordination. Both approaches utilized CoDrone EDU units, which were selected for their programmability and suitability for controlled laboratory testing.

Centralized Architecture: Total of 3 USB hubs were used in series to connect to one main PC for the centralized control configuration. The hubs enabled multiple drones to be attached to a single computer at once, and individual CoDrone EDU unit was connected by a separate USB controller. With the help of the standard libraries, this setup allowed central commands execution, in which all drones got orders straight from the central computer.

Client-Server Architecture: Every CoDrone EDU unit served as a client node by being connected to a different PC. A reliable and quick communication method was ensured by connecting each of the client PCs to a local Ethernet network. The control commands were aggregated and dispersed by a central server computer that was linked to a common Ethernet network. Using TCP/IP socket communication, the server communicated flight commands that were entered by the user to the clients. Then, using its local RF controller, each client computer sent the commands it had received to the appropriate drone. Additionally, the following safety measures must to be implemented before to doing any experiment:

- For every drone to participate in the mission it need to be in its optimal condition because irregular behavior can be caused by the structural problems of the drones.

- Due to the limited RF range of the communication the weak signal can cause the interference in flight path resulting in incomplete or inaccurate paths.

Python Script: To enable the control of multiple drones from the DCS, a dedicated software program is required to manage the dispatch and coordination of commands. In this study, two separate Python-based programs were developed using the CoDrone EDU API, tailored for each of the evaluated control architectures: centralized and client-server.

For the

Centralized Architecture, the Python script utilizes the "threading" package to ensure synchronized command execution across all connected drones. The program starts by identifying and listing all active serial ports for each CoDrone EDU device. Once all the drones are connected and registered the user gives the commands according to the intended mission. Multithreaded execution is used to dispatch the command simultaneously that gives the control with synchronized behavior. It ensures that all drones perform uniformly regard less of being connected to single host computer. On the other hand, in Client-Server Architecture, an additional package is needed for the implementation of TCP/IP socket communication. The server makes and manages the connection with all participating client computers. Every client is recorded in a list and register the input to execute the commands. Whereas, the clients keeps the constant connection with the server by receiving the commands over the network and CoDrone EDU API executes them. This architecture enables distributed execution, with each drone controlled by an individual computer, providing scalability and increased processing distribution. The source code used in the experiments is available on GitHub [

21]

4.2. Flight Tests

For Centralized and Client-Server architectures, flight tests of the scenario were designed to evaluate the key performance criteria essential for the successful execution of coordinated multi-drone missions.

4.2.1. Scalability

Scalability tests assess the system’s capacity to maintain stable performance and reliable communication as the number of drones increases. These tests assess the architecture's ability to handle the increasing demand for command transmission under scaled-up conditions. The number of CoDrone EDU units was gradually increased. Real-time communication was monitored throughout, and simple flight commands (take-off and landing) were issued to evaluate the performance of the system under scaling conditions.

Initially, a single USB hub was used, with up to seven drones connected simultaneously. During this stage, the system remained stable, and all drones were able to receive commands and execute them without issues. Communication between the DCS and each drone was consistent and reliable, indicating that the centralized setup is viable for a limited number of units.

Results: When a second USB hub was connected in a daisy-chain (serial) configuration to the first hub to expand the number of ports, 14 drones in total, intermittent connectivity issues began to occur. Drones were frequently disconnected and reconnected from the host computer, and command execution became less predictable. These issues worsened with the addition of a third hub, 21 drones in total, where the connection became increasingly unstable. Although some drones could still connect, the communication link was not reliable, and synchronized control was compromised.

In this approach, the use of computers connected to the same local network is essential for establishing a stable and reliable client-server communication environment. Each client computer is connected to a single CoDrone EDU unit via its dedicated RF controller and is responsible for receiving instructions from the central server computer over a TCP/IP protocol. Clients and the server must be connected to the same network, in our case, through a wired Ethernet connection.

Result: For the experimental setup, a total of 30 client computers were used, each controlling one CoDrone EDU. The server, running the control software and managing all communication flows, was also connected to the same Ethernet network. A key requirement for this architecture is that the server must maintain a strong and consistent connection with all client devices to ensure synchronized drone control. The architecture demonstrated scalability and stability. As the number of drones increased, the system maintained reliable control without noticeable delay or signal degradation. The commands were transmitted efficiently from the server to each client, and then to the corresponding drone.

4.2.2. Inspection Coverage

To achieve greater accuracy in the mission, we propose a solution for multi-UAV route optimization that integrates the multi-traveling salesman problem (mTSP) with coverage path planning (CPP) to cover a closed environment (room) efficiently.

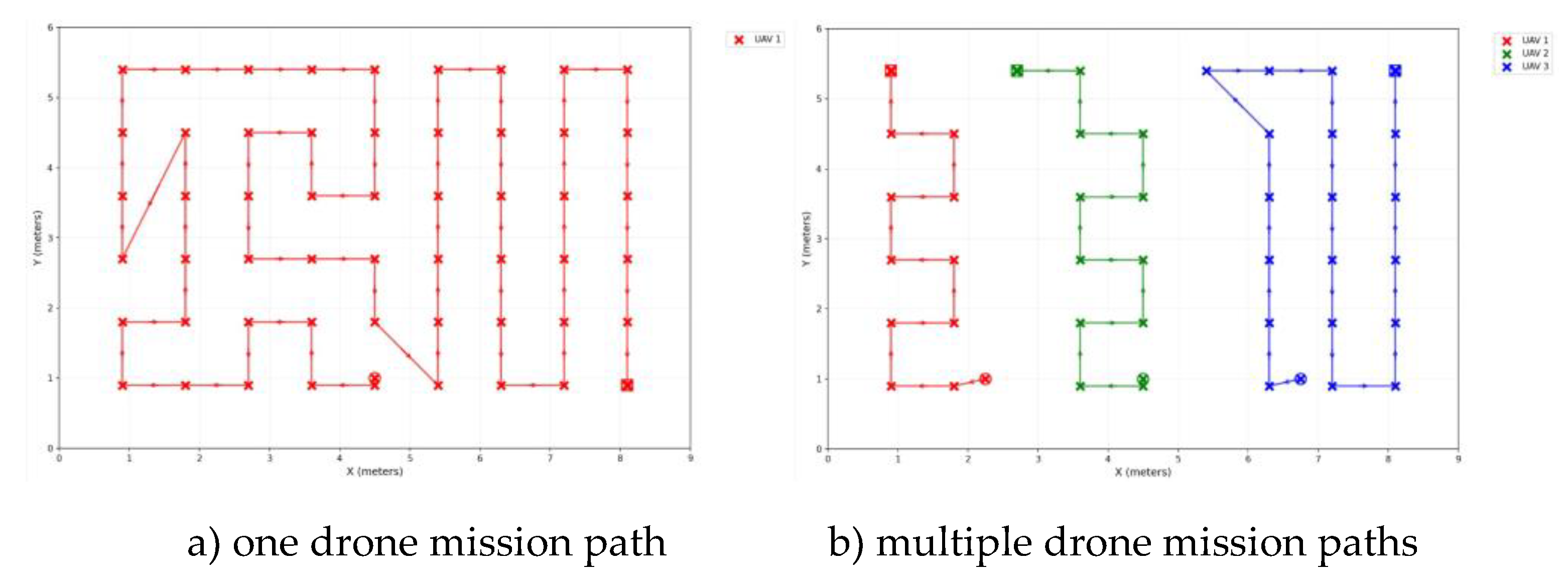

For a

9 × 6 room, two scenarios were analyzed with the help of optimization algorithms (G

reedy): one using a single drone and another using three drones. In

Figure 15, the corresponding routes for each case are shown.

While in

Table 4, the coverage and efficiency analysis of each route shows that the single-drone mission achieved a coverage of 77.8% with an efficiency of 1.547, demonstrating a more complete inspection of the environment. In contrast, the multiple-drone configuration reached a lower coverage of 61.6% but achieved a slightly higher efficiency of 1.642. These results highlight a trade-off: the single-drone approach is more effective in maximizing coverage, while the multiple-drone strategy improves efficiency by shortening path length relative to the area inspected.

4.2.3. Mission Time

In the following experiment, we measured and compared the total time required to find the yellow card on the floor (randomly placed) using two different configurations: a single drone and a multi-drone setup. The test environment consisted of a standard indoor room (6x9 meters), employing the optimized path evaluated in the previous test to ensure complete and uniform floor coverage. In the single-drone configuration, the drone was assigned to navigate through all designated waypoints sequentially. The total mission time, from takeoff to landing, was recorded and is illustrated in

Table 5.

The inspection area was divided into equal sub-zones for the multi-drone configuration, each assigned to an individual drone. All drones were launched simultaneously following the previous path, aiming to reduce the overall mission duration while maintaining full coverage.

5. Discussion

A straightforward and practical approach is the centralized architecture, which is based on sending commands from a GCS over a USB port hub. It is especially suitable for educational or classroom applications or controlled testing environments due to its simple implementation. However, there are hardware limitations, especially about the host computer's maximum USB connection capacity and communication stability. When several hubs are linked together in series, the scalability is constrained.

Significantly improved capacity and coordination across a larger number of drones are provided by the client-server approach, which is based on TCP/IP connection and several distributed GCS systems. Through the use of a centralized server, this design enables each drone to be controlled by a separate computer functioning as a client.

Although this technique improves control range and flexibility, it also necessitates more complicated programming and stable local network circumstances to guarantee dependable real-time performance. To some degree, synchronized command execution and scalability are supported by both client-server and centralized designs; yet, practical constraints are still imposed by network and hardware constraints. The availability of USB ports and physical closeness to the GCS are prerequisites for the centralized solution. Assuming dependable TCP/IP connections, the client-server architecture, on the other hand, benefits from the network's modular design, which permits more flexible drone placement and increased coverage of the area.

The results encourage the use of inexpensive drone collections for classroom instruction, testing, and experimentation by providing researchers and educators with useful insights. Furthermore, this study establishes the foundation for upcoming advancements in numerous drone coordination structures, especially in the context of educational settings with limited resources and accessibility.

5.1. Limitations

It is essential to keep the hardware constrains of the CoDrone EDU under consideration while performing the multi-drone coordination experiment. Besides, them being cost effective, and suitable for the educational setups there are still some limitations associated with its use. The Radio Frequency (RF) communication restricts drone’s remote controlling range. The limited battery life supports only limited flying duration that can also cause the inconsistent flight behavior effecting the stability and safety.

Similarly, the use of CoDrone EDU is limited to indoor only making it extremely sensitive for the outdoor environment, which can lead toward the unpredictable mission situations.

5.2. Threats to Validity

This study acknowledges several threats to validity that may affect the interpretation of the results.

Internal Validity. The flight tests were conducted under controlled classroom conditions, which may not fully reflect real-world operational environments. To minimize this threat, the same test environment was used for all experiments, ensuring consistency across both approaches.

External Validity. Only CoDrone EDU units, educational drones that have minimal sensing and connectivity capabilities, were used in the test flights. The selected drones offer a controlled and consistent environment, which makes them appropriate for verifying the suggested designs prior to scaling to more complicated systems, even though this restricts generalization to sophisticated platforms.

Construct Validity. The main metrics used to assess mission success were time needed for execution, extent, and system behavior. These criteria were chosen because they accurately represent the effectiveness and dependability of multi-drone cooperation, even though they might not capture all performance factors.

6. Conclusion

To overcome the drawbacks of their default one-to-one model, this study proposes and assesses two control strategies, centralized and Client-Server configurations, for coordinated control of numerous CoDrone EDU units. Although it is easy to use and accessible for academic use, the first architecture, a centralized one, is not scalable. Although it requires additional work to develop and network stability, the second, which is based on a client-server paradigm using TCP/IP sockets, enhances synchronization with the execution of commands.

Both centralized and client-server systems are feasible within their respective scopes, according to flight experiments, with hardware limitations being a major drawback. While the central architecture is still useful for simple applications and prototyping, the client-server structure eventually provides superior scalability. It is better suited for advanced educational or academic and research use.

Furthermore, there was a 77.9% decrease in mission time when comparing the inspection time of a defined region with a single drone against a coordinated multi-drone arrangement. This outcome demonstrates the useful advantages of coordinated drone control in terms of effectiveness and time savings, particularly in situations requiring quick and consistent coverage. Both centralized and client-server systems are feasible within their respective scopes, according to flight tests, with hardware limitations being a major drawback. While the centralized architecture is still useful for simple applications and prototyping, the client-server paradigm eventually provides superior scalability and is better suited for advanced educational and research use.

Furthermore, there was a 77.9% decrease in mission time when comparing the inspection time of a defined region with a single drone against a coordinated multi-drone arrangement. These results highlight how crucial it is to choose a suitable control architecture that takes mission duration and operational objectives into account in addition to technological capabilities.

References

- S. Kravchuk and L. Afanasieva, “Formation of a wireless communication system based on a swarm of unmanned aerial vehicles,” Inf. Telecom mun. Sci., vol. 0, no. 1, pp. 11–18, Jul. 2019. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- L. Gebrehiwet, Y. Negussie, and E. Tesfaye, ”A review on drone ground control station, configurations, types, and the communication systems,” Int. J. Interdiscip. Sci. Eng. Appl., vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 1–14, Nov. 2024.

- M. Asadpour et al., ”Swarming of micro air vehicles using tethered external vision-based localization,” IEEE Trans. Robot., vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 148–165, Feb. 2017.

- M. R. Brust and C. Ribeiro, ”Edge-assisted communication architecture for UAV-based smart city applications,” Sensors, vol. 20, no. 23, pp. 1–16, Dec. 2020.

- B. Younas, J. Delgado Ruiz, and S. Ahn, “Designing an Interoperable UAV Communication Model: A NIEM-Driven Approach,” Journal of Visual Language and Computing, vol 2025, no. 2. pp. 26-34. Oct. 2025, [Online]. Available: https://ksiresearch.org/jvlc/journal/JVLC2025N2/JVLC075.pdf.

- H.-H. Chen, ”Developing a custom communication protocol for UAVs: Ground control station and architecture design,” Internet Things, vol. 27, p. 101319, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Giernacki, J. Rao, ˇ S. Sladi´c, A. Bondyra, M. Retinger, and T.Espinoza-Fraire, “DJI Tello Quadrotor as a Platform for Research and Education in Mobile Robotics and Control Engineering,” in 2022 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), pp. 735–744, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. Bai, H. Chu, H. Liu, y G.Hui, “Drones in Education: A Critical Review,” Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education (TURCOMAT), vol.12, no.11, pp.1722–1727, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Budaciu, N. Botezatu, M. Kloetzer, and A. Burlacu, “On the Evaluation of the Crazyflie Modular Quadcopter System,” in Proc. 24th IEEE Int. Conf. Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Zaragoza, Spain, 2019, pp. 1189–1195. [CrossRef]

- M. Elrod et al., “Educational drones: A comparison for STEM learning,” Journal of Robotics Education, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 123–135, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- Robolink Inc., ”CoDrone EDU– Programmable Drone for Learning,” Robolink, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.robolink.com/codrone edu/.

- G. R. Miller, “An object-oriented approach to structural analysis and design,” Computers & Structures, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 75–82, 1991. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- E. Vlasceanu and D. Popescu, ”Ground Control Station for Multi-UAV Systems,” U.P.B. Scientific Bulletin, Series C: Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, vol. 83, no. 2, pp. 253–264, 2021.

- O. Pohudina, M. Kovalevskyi, and M. Pyvovar, ”Group Flight Automation Using Tello EDU Unmanned Aerial Vehicle,” in Proc. 2021 IEEE 16th Int. Conf. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. (CSIT), Lviv, Ukraine, 2021, pp. 123–126. [CrossRef]

- P. Hell, M. Mezei, and P. J. Varga, ”Drone communications analysis,” in Proc. 15th IEEE International Symposium on Applied Machine Intelligence and Informatics (SAMI), Herl’any, Slovakia, Jan. 2017, pp. 000213–000216. [CrossRef]

- S. Hayat, E. Yanmaz, and R. Muzaffar, “Survey on unmanned aerial vehicle networks for civil applications: A communications viewpoint,” IEEE Communications Surveys and Tutorials, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 2624–2661, Fourth quarter 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, Y. Zhou, and L. Lamont, ”Communication architectures and protocols for networking unmanned aerial vehicles,” in Proc. IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), Atlanta, GA, USA, Dec. 2013, pp. 1415–1420. [CrossRef]

- J. Rodriguez-Diaz et al., “Communication technologies for drone fleet coordination: RF, cellular, and mesh networking,” Ad Hoc Networks, vol. 98, pp. 101873:1–17, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- DJI, “Elevating Operations: The Benefits of Cloud-Based Drone Management,” DJI Whitepaper, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://enterprise insights.dji.com/cloud-whitepaper.

- R. Kumar, A. Singh, and P. S. Saini, “Cloud computing for UAVs: A survey,” International Journal of Computer Applications, vol. 179, no. 27, pp. 1–4, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Delgado, “Multi-drone control with CoDrone EDU,” GitHub repository, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/alejadelg/-Multi Drone-Control.

Figure 1.

Drone Control Modes on CoDrone EDU.

Figure 1.

Drone Control Modes on CoDrone EDU.

Figure 2.

DCS development process.

Figure 2.

DCS development process.

Figure 3.

Drone detecting a yellow card on the floor.

Figure 3.

Drone detecting a yellow card on the floor.

Figure 4.

Drone Control Station use case diagram.

Figure 4.

Drone Control Station use case diagram.

Figure 5.

High-level class diagram of the DCS system.

Figure 5.

High-level class diagram of the DCS system.

Figure 6.

Detailed class diagram of the DCS System.

Figure 6.

Detailed class diagram of the DCS System.

Figure 7.

Class diagram of multi-drone mission control.

Figure 7.

Class diagram of multi-drone mission control.

Figure 8.

Drone controllers are connected to the port hub.

Figure 8.

Drone controllers are connected to the port hub.

Figure 9.

Centralized Architecture.

Figure 9.

Centralized Architecture.

Figure 10.

Deployment diagram of the Centralized Architecture.

Figure 10.

Deployment diagram of the Centralized Architecture.

Figure 11.

Sequence diagram of the Centralized Architecture.

Figure 11.

Sequence diagram of the Centralized Architecture.

Figure 12.

Client-Server Architecture.

Figure 12.

Client-Server Architecture.

Figure 13.

Deployment diagram of the Client-Server Architecture.

Figure 13.

Deployment diagram of the Client-Server Architecture.

Figure 14.

Sequence diagram of the Client-Server Architecture.

Figure 14.

Sequence diagram of the Client-Server Architecture.

Figure 15.

Mission paths.

Figure 15.

Mission paths.

Table 1.

UC-01: Detect the yellow card mission.

Table 1.

UC-01: Detect the yellow card mission.

| Use case name |

Detect the yellow card mission |

| Actors |

Operator, drones |

| Preconditions |

- Somewhere inside the room, a yellow card is on the floor.

- All the drones are pairing with the DCS.

- Drones are hovering, waiting for the mission. |

| Flow of events |

Main success flow |

1. The operator opens the script for the "Detect Yellow Card" mission on the DCS terminal.

2. The operator runs the code for the mission.

3. The DCS sends the mission commands to the drone.

4. All the drones receive the mission commands.

5. The drones start to move around the room.

6. One drone detects the yellow card.

7. Include (Give yellow card information).

8. The DCS displays the notification "Yellow card is found."

9. The DCS sends a “stop” command to all the drones.

10. All the drones stop. |

| Alternative flow |

6.a. The drones finish the mission and don’t find the yellow card.

6.b. The DSC displays “mission complete, no card detected”.

6.c. Include (Return Home)

6.d. The operator opens and runs the script for the "Detect Yellow Card" mission. |

| Postconditions |

The system shows the yellow card location. |

Table 2.

Functional and Non-Functional Requirements.

Table 2.

Functional and Non-Functional Requirements.

| ID |

Name |

Description |

| FR01 |

Mission

communication |

The DCS shall be able to send the drone’s mission parameters via RF communication. |

| FR02 |

Alternative Mission Handling |

If the yellow card is not detected, the system shall allow the operator to initiate a second flight. |

| FR03 |

Mission Execution |

The drone shall initiate the mission upon receiving the instructions from the DCS. |

| FR04 |

Path Navigation |

The drone shall follow the predefined path as indicated in the mission guidelines. |

| FR05 |

Card Detection |

The drone shall detect the presence of a yellow card within the operational area. |

| FR06 |

Alert

Generation |

Upon detecting the yellow card, the drone shall send an alert to the DCS with the detection status. |

| FR07 |

Mission

Completion |

The drone shall land and notify the DCS once the mission is completed. |

| NFR01 |

Communication Reliability |

RF communication between the DCS and the drone shall have a minimum reliability of 99% during mission execution. |

| NFR02 |

System

Usability |

The mission setup and execution process shall be operable by a trained user within 5 minutes. |

| NFR03 |

Response Time |

The drone shall send an alert to the DCS within 2 seconds of detecting the yellow card. |

| NFR04 |

Flight

Autonomy |

The drone shall be capable of completing the mission within a single battery cycle under normal conditions. |

Table 3.

Comparison of possible drone control approaches and selection rationale for multi-drone environments.

Table 3.

Comparison of possible drone control approaches and selection rationale for multi-drone environments.

| Architectures |

Limitations/Challenges |

Why was (Not)

Selected |

| One-to-One RF |

No inter-drone communication; not scalable; instructor workload |

Not-Selected: Basic method already in use, lacks coordination capabilities |

| Mesh Network |

Complex software; hardware not supported in basic drones |

Not-Selected: Incompatible with low-cost educational drones |

| Peer-to-Peer (P2P) |

High complexity, poor control in the educational context |

Not-Selected: Difficult to synchronize in real-time educational settings |

| Cloud-Based Communication |

Requires internet access; latency issues |

Not-Selected: Not suitable for real-time applications |

| Centralized with USB Hub |

Limited by USB port count; less flexible for dynamic tasks |

Selected: Cost-effective, simple to set up, and practical |

| Client-Server Architecture over TCP/IP |

Requires multiple PCs and a networking setup |

Selected: Scalable, uses common networking, enables synchronized multiple drone control. |

Table 4.

Drone mission paths coverage and efficiency.

Table 4.

Drone mission paths coverage and efficiency.

| |

Coverage |

Efficiency |

| One drone mission path |

77.8 % |

1.547 |

| Multiple drone mission paths |

61.6% |

1.642 |

Table 5.

Comparison of the time required to find the card.

Table 5.

Comparison of the time required to find the card.

| Configuration |

Time required to find the card (seconds) |

| One single Drone |

57 |

| Multi-drones Centralized Architecture |

12.2 |

| Multi-drones Client-Server Architecture |

12.6 |

| Percentage of reduced time |

77.9% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).