Submitted:

28 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1)

- How can remote sensing data alone be used to develop a reservoir operation scheme that enhances the accuracy of flow estimation by the DHM at dam sites?

- 2)

- To what extent does incorporating reservoir operations into DHM calibration improve hydrological (flood) estimates across the basin, and what are the associated spatial-temporal effects?

2. Study Area

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. DRIVE-Dam Hydrological Model Framework

3.2.1. DRIVE Model

3.2.2. Development and Coupling of Reservoir Scheme in DRIVE

3.3. Satellite-Based Reservoir Storage Reconstruction

3.3.1. H-A-V Relationship Extraction from FABDEM

3.3.2. Reconstructing Storage Dynamics

3.4. DRIVE-Dam Calibration and Experimental Setup

3.5. Performance Metrics and Model Validation

4. Results

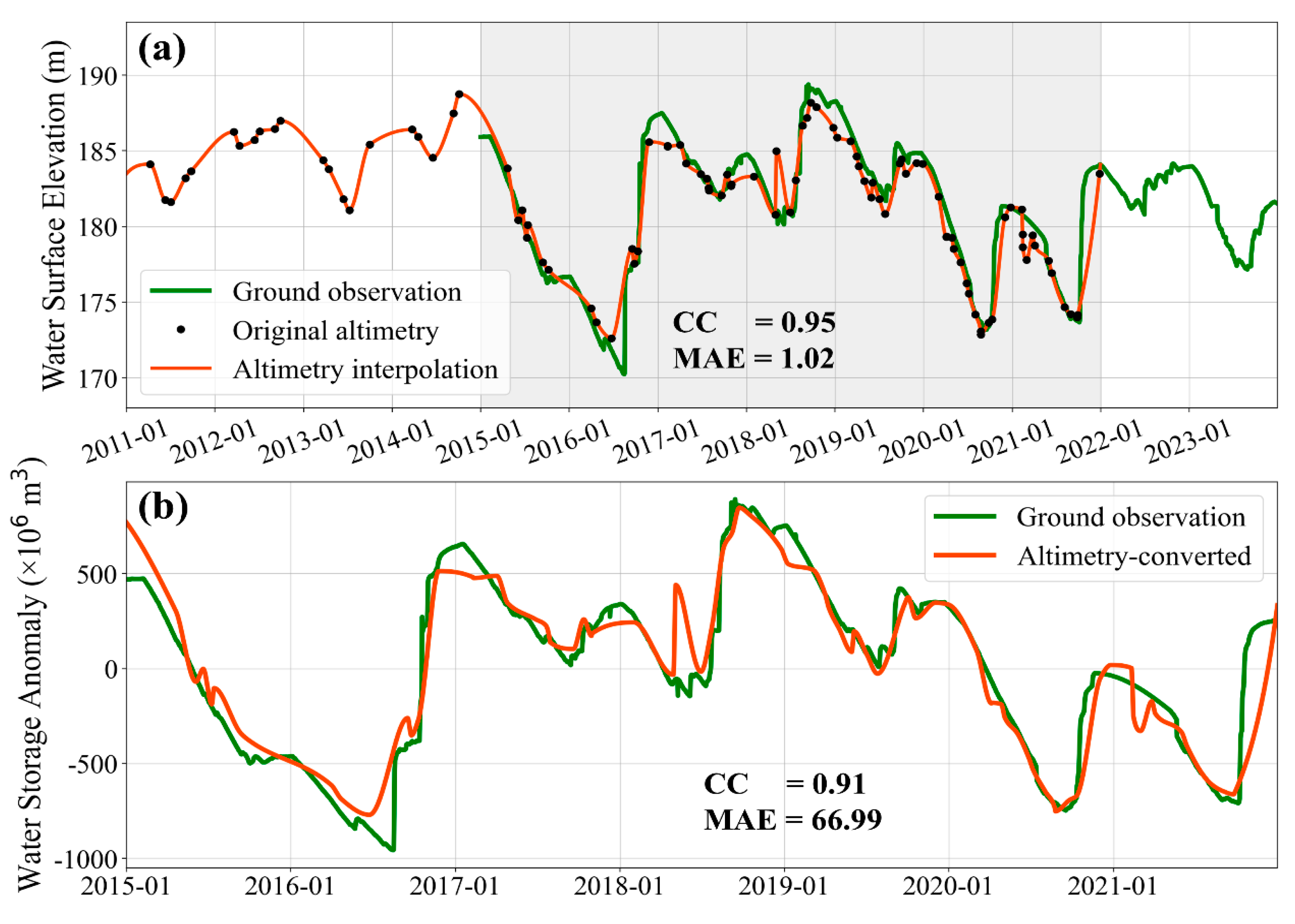

4.1. Validation of Satellite-Derived Reservoir Dynamics

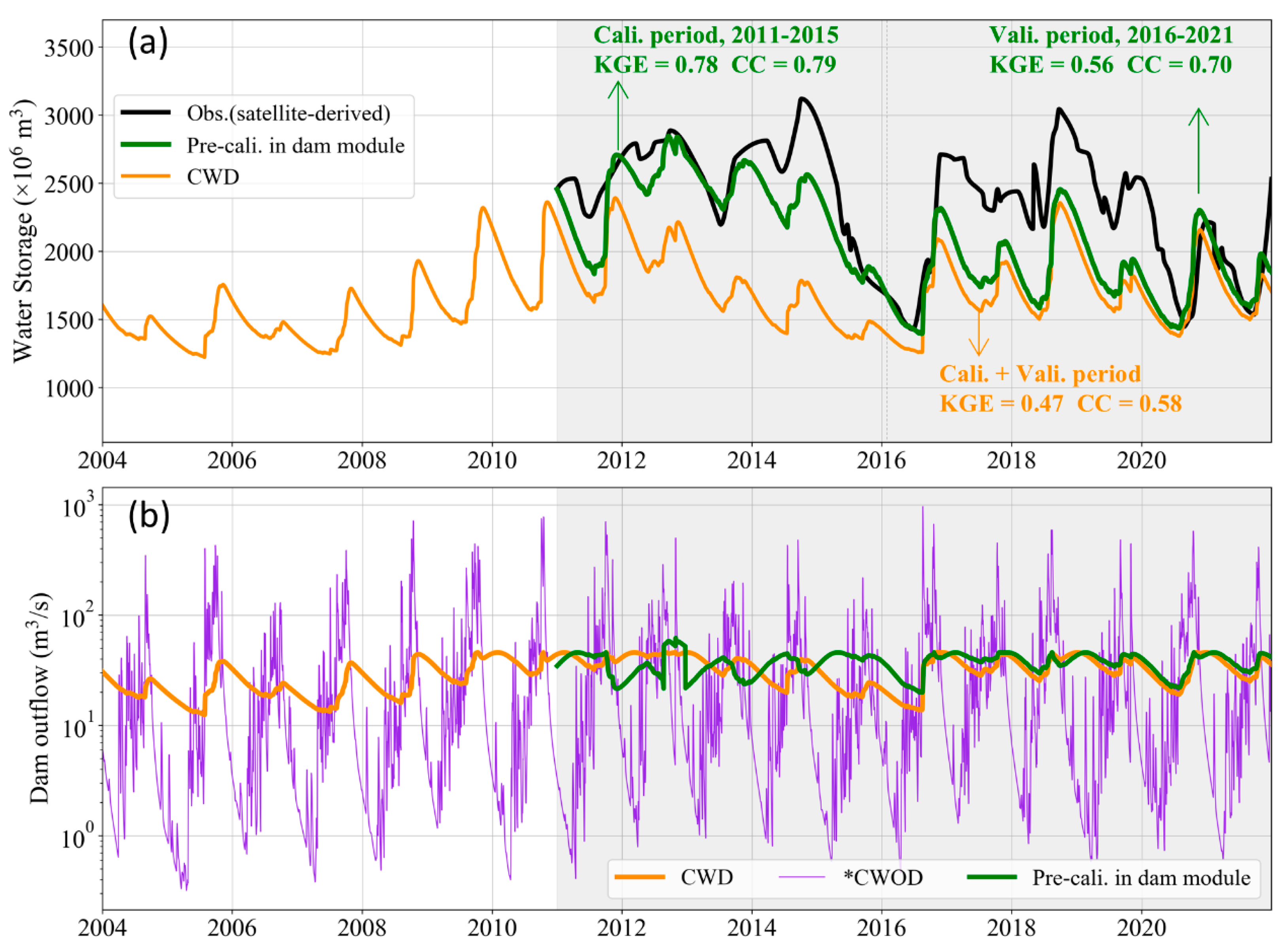

4.2. Pre-Calibration of Reservoir Operation Scheme

4.3. Performance Evaluation of Streamflow Simulation

4.3.1. Long-Term Modelling Skills

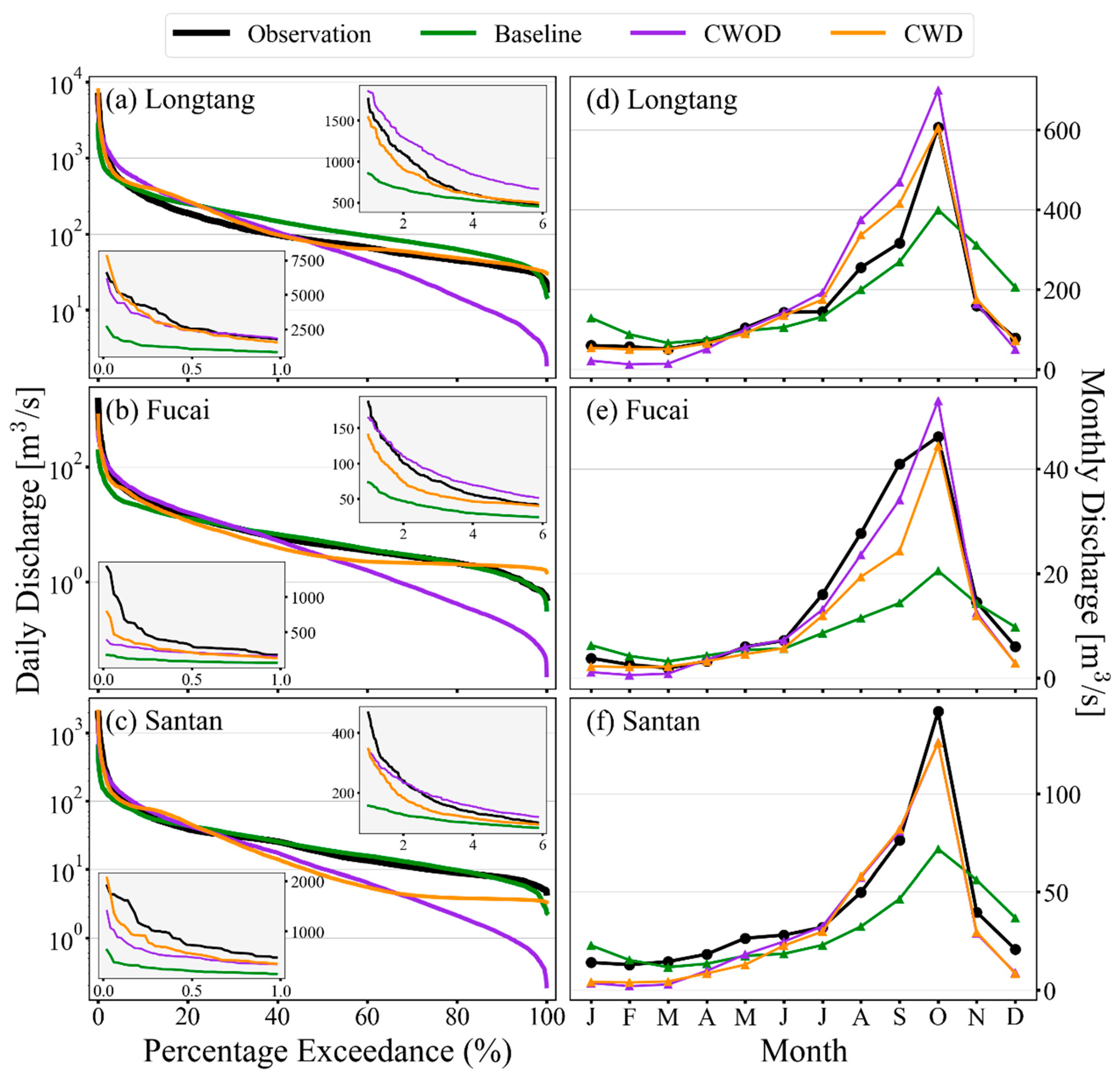

4.3.2. Flow Duration and Seasonality

4.4. Model Skills in Capturing Flood Events

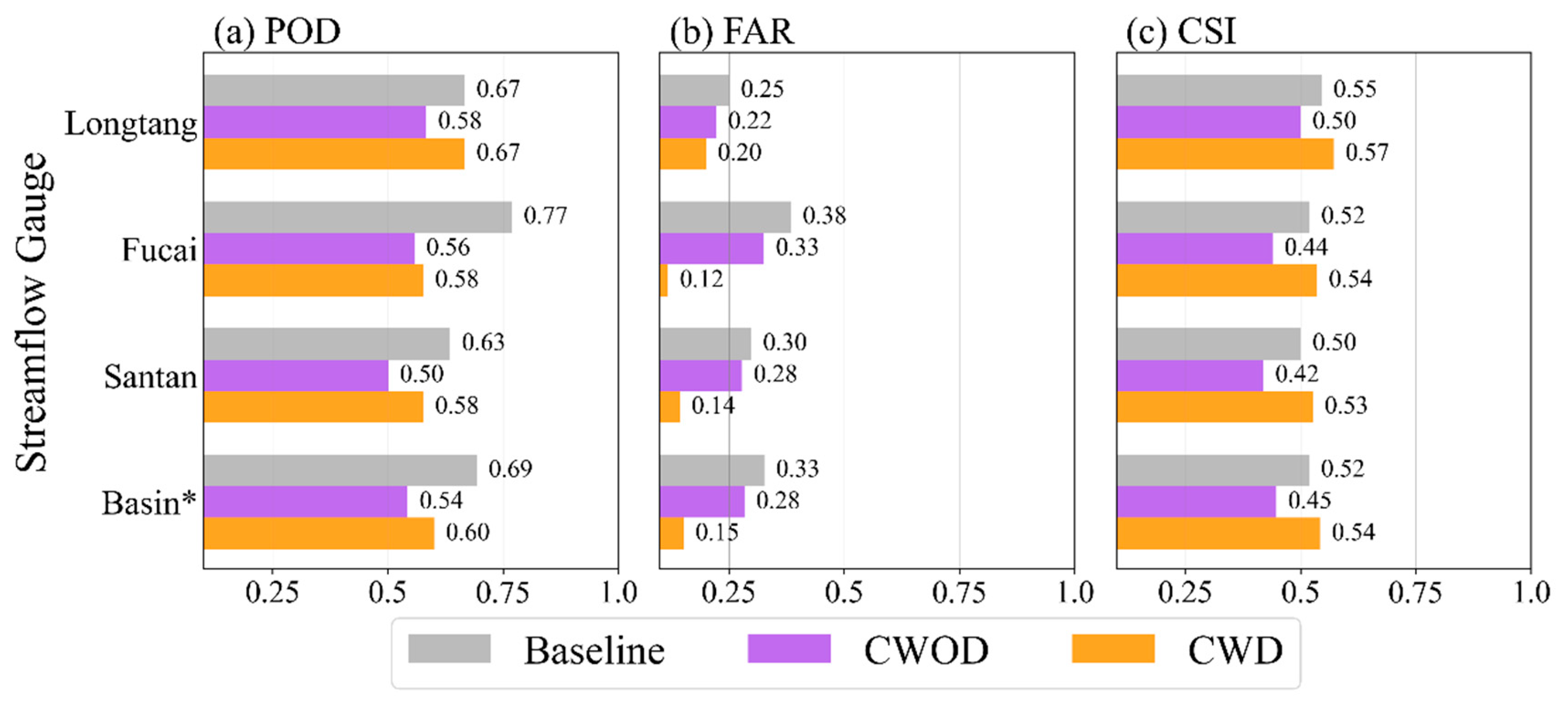

4.4.1. Flood Event Detection Capability

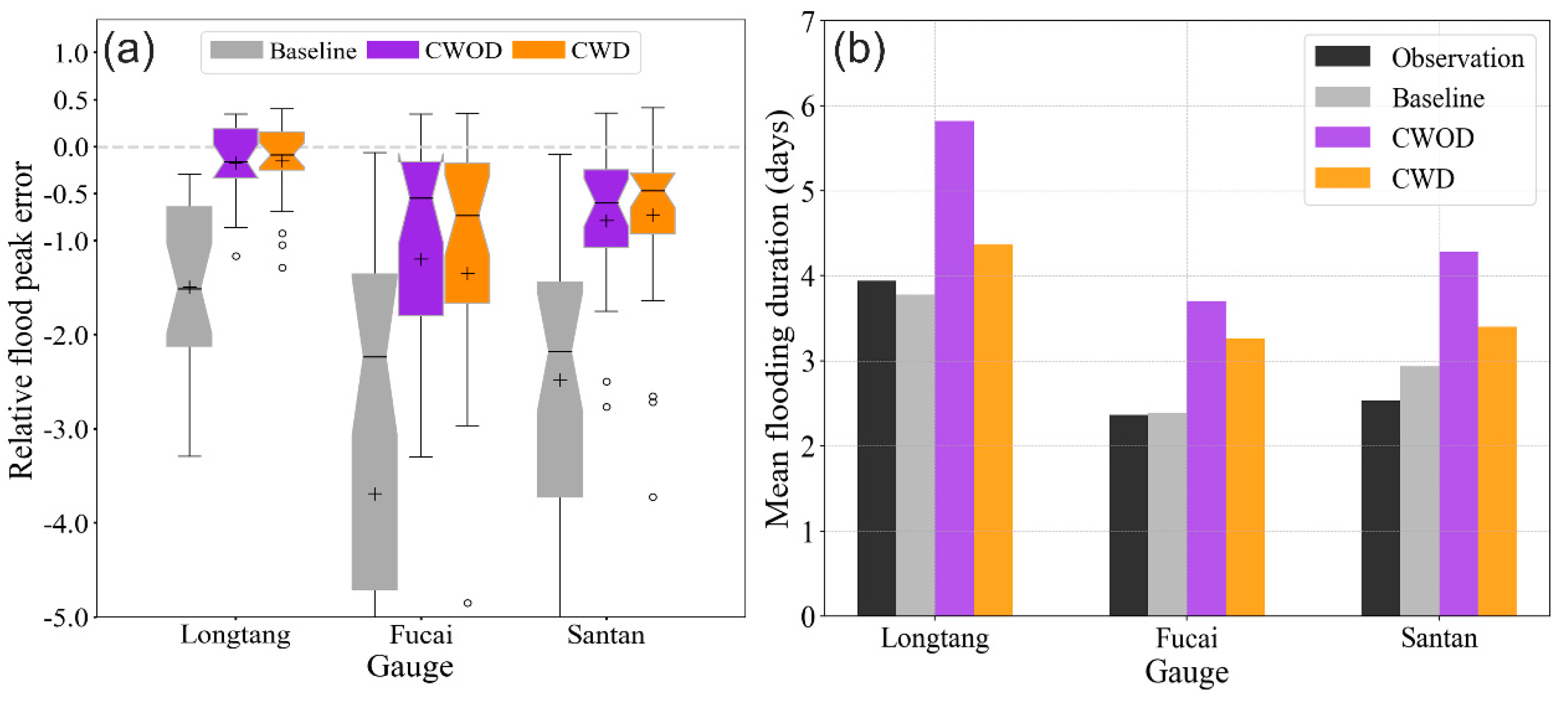

4.4.2. Flood Peak and Duration

5. Discussion

5.1. Advanced H-A-V Extraction Based on Water Connectivity

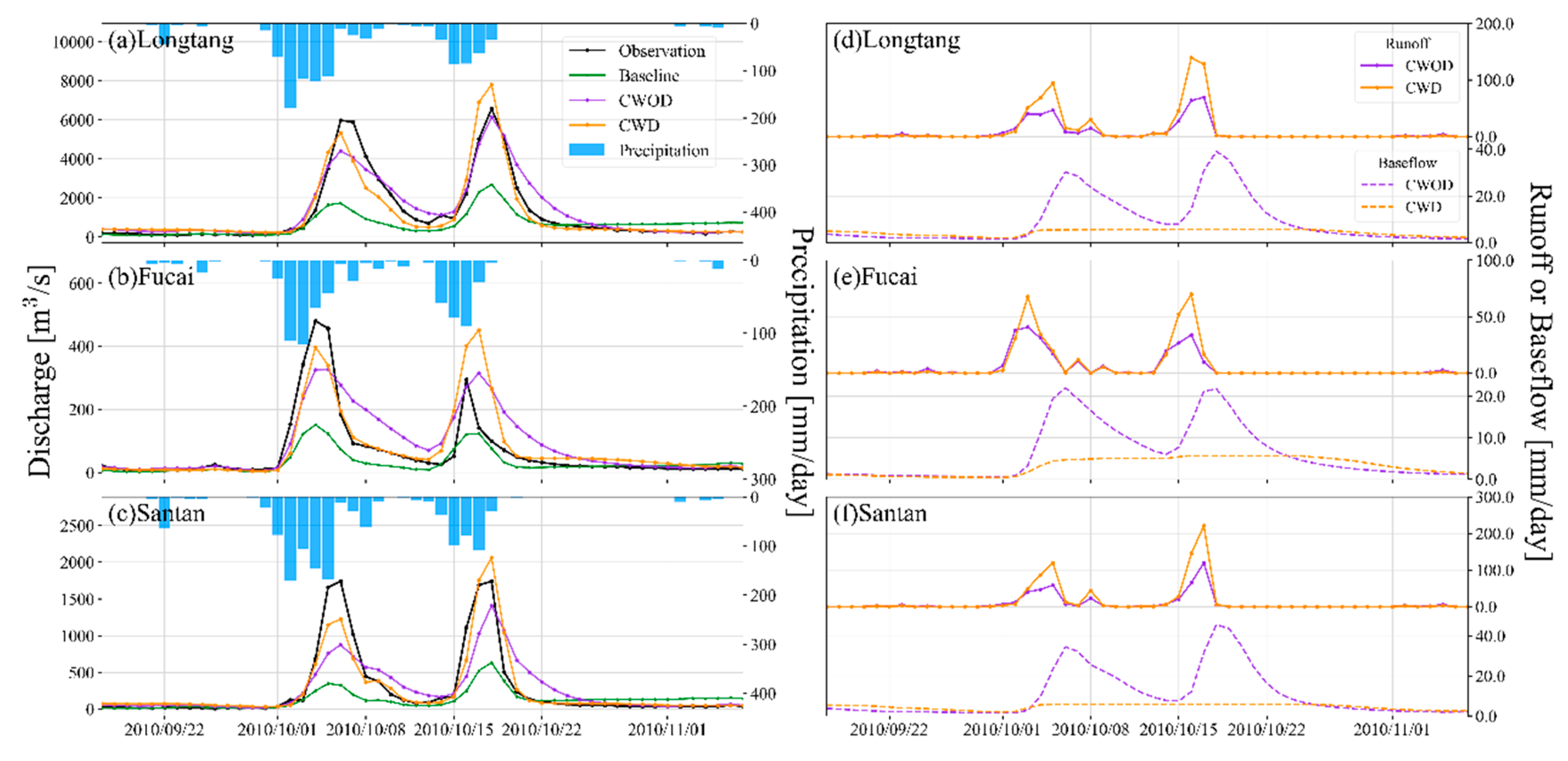

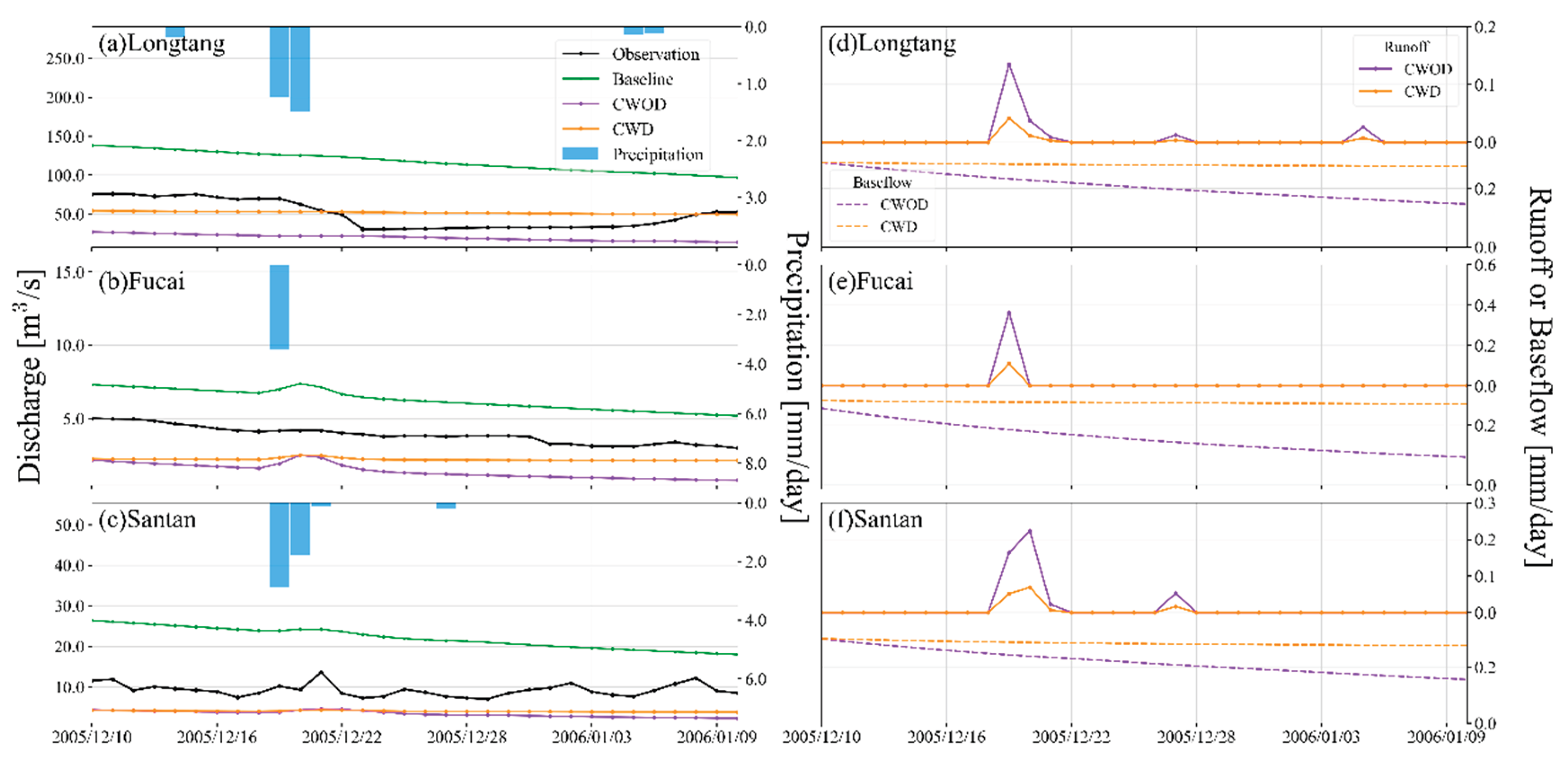

5.2. Diagnosis of Hydrological Response Mechanism

5.3. Synergistic Benefits of Enhanced Model Structure and Parameterization

6. Conclusions

- High-temporal-resolution (daily) reservoir dynamics can be successfully reconstructed by combining sparse satellite altimetry with DEM-derived topographic information, supporting the development of reservoir operation schemes under data-scarce conditions.

- The explicit representation of reservoir processes contributes positively to DHM calibration, improving the overall accuracy of hydrological estimations across the watershed. In particular, flood modeling performance was notably enhanced, with the POD increasing from 0.54 to 0.60 and the FAR decreasing from 0.28 to 0.15. The improvements originate from the calibration process, with the simulated hydrograph reflecting dam-induced flood peak attenuation in wet seasons and water supplementation in dry seasons, closely matching downstream regulated observations.

- Although the conventional dam-excluded calibration achieves acceptable performance at the basin outlet, it compromises accuracy in upstream regions. The resulting simulations exhibit subdued flood impulses and reduced peak intensities, accompanied by prolonged flood recession and underestimated dry-season discharges. The deterioration stems from spurious parameters resulting from calibrating a reservoir-free model (simulating natural flow) against dam-regulated observations, generating unreasonable baseflow-runoff responses.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duan, Z.; Bastiaanssen, W. Estimating water volume variations in lakes and reservoirs from four operational satellite altimetry databases and satellite imagery data. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2013, 134, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, B.F.; Wu, Y.H.; Li, Y.S. Impact of Artificial Reservoir Water Impoundment on Global Sea Level. Science 2008, 320, 212–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinti, R.A.; Condon, L.E.; Zhang, J. The evolution of dam induced river fragmentation in the United States. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belletti, B.; de Leaniz, C.G.; Jones, J.; Bizzi, S.; Börger, L.; Segura, G.; Castelletti, A.; van de Bund, W.; Aarestrup, K.; Barry, J.; et al. More than one million barriers fragment Europe’s rivers. Nature 2020, 588, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grill, G. , et al., Mapping the world’s free-flowing rivers. Nature 2019, 569, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddeland, I.; Heinke, J.; Biemans, H.; Eisner, S.; Flörke, M.; Hanasaki, N.; Konzmann, M.; Ludwig, F.; Masaki, Y.; Schewe, J.; et al. Global water resources affected by human interventions and climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 111, 3251–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettenmaier, D.P.; Milly, P.C.D. Land waters and sea level. Nat. Geosci. 2009, 2, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanasaki, N.; Kanae, S.; Oki, T. A reservoir operation scheme for global river routing models. J. Hydrol. 2006, 327, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; I E Veldkamp, T.; Frieler, K.; Schewe, J.; Ostberg, S.; Willner, S.; Schauberger, B.; Gosling, S.N.; Schmied, H.M.; Portmann, F.T.; et al. The critical role of the routing scheme in simulating peak river discharge in global hydrological models. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 075003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poff, N.L.; Allan, J.D.; Bain, M.B.; Karr, J.R.; Prestegaard, K.L.; Richter, B.D.; Sparks, R.E.; Stromberg, J.C. The Natural Flow Regime. Bioscience 1997, 47, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, H.; Leung, L.R.; Yigzaw, W.; Zhao, J.; Lu, H.; Deng, Z.; Demisie, Y.; Blöschl, G. Nonlinear Filtering Effects of Reservoirs on Flood Frequency Curves at the Regional Scale. Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 8277–8292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, M.E.; Cochrane, T.A.; Kummu, M.; Lauri, H.; Holtgrieve, G.W.; Koponen, J.; Piman, T. Impacts of hydropower and climate change on drivers of ecological productivity of Southeast Asia's most important wetland. Ecol. Model. 2014, 272, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-P.; Feng, D.; Pan, M.; Beck, H.; Lawson, K.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Shen, C. From calibration to parameter learning: Harnessing the scaling effects of big data in geoscientific modeling. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlumsky, R.; Mai, J.; Craig, J.R.; Tolson, B.A. Simultaneous Calibration of Hydrologic Model Structure and Parameters Using a Blended Model. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupzig, J.; Kupzig, N.; Flörke, M. Regionalization in global hydrological models and its impact on runoff simulations: a case study using WaterGAP3 (v 1.0.0). Geosci. Model Dev. 2024, 17, 6819–6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.V.; Sorooshian, S.; Yapo, P.O. Toward improved calibration of hydrologic models: Multiple and noncommensurable measures of information. Water Resour. Res. 1998, 34, 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Adler, R.F.; Tian, Y.; Huffman, G.J.; Li, H.; Wang, J. Real-time global flood estimation using satellite-based precipitation and a coupled land surface and routing model. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 2693–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.; Refsgaard, J.C.; Jensen, K.H. Distributed hydrological modelling of the Senegal River Basin — model construction and validation. J. Hydrol. 2001, 247, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Ajami, N., et al., Calibration of a semi-distributed hydrologic model for streamflow estimation along a river system. Journal of Hydrology 2004, 298, 112–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenault, R.; Brissette, F.; Martel, J.-L. The hazards of split-sample validation in hydrological model calibration. J. Hydrol. 2018, 566, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Sorooshian, S.; Gupta, V.K. Optimal use of the SCE-UA global optimization method for calibrating watershed models. J. Hydrol. 1994, 158, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Tolson, B.A.; Mai, J. Time to Update the Split-Sample Approach in Hydrological Model Calibration. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Hernández, F.; Liang, X.; Yuan, H. A Calibration Framework for High-Resolution Hydrological Models Using a Multiresolution and Heterogeneous Strategy. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, T.; Tavakoli, M.; Van Steenbergen, N.; De Smedt, F.; Batelaan, O.; Pereira, F.; Willems, P. Intercomparison of five lumped and distributed models for catchment runoff and extreme flow simulation. J. Hydrol. 2014, 511, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.B.; Koren, V.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Reed, S.M.; Cui, Z.; Moreda, F.; Cosgrove, B.A.; Mizukami, N.; Anderson, E.A.; et al. Results of the DMIP 2 Oklahoma experiments. J. Hydrol. 2012, 418-419, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, P.; Gupta, H.V. On the ability to infer spatial catchment variability using streamflow hydrographs. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, L.; Burek, P.; Dutra, E.; Krzeminski, B.; Muraro, D.; Thielen, J.; Pappenberger, F. GloFAS – global ensemble streamflow forecasting and flood early warning. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 1161–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, L.; Libertino, A.; Campo, L.; Dottori, F.; Gabellani, S.; Ghizzoni, T.; Masoero, A.; Rossi, L.; Rudari, R.; Testa, N.; et al. Impact-based flood forecasting in the Greater Horn of Africa. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 24, 199–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, H.; Shrestha, P.K.; Rakovec, O.; Apel, H.; Vorogushyn, S.; Kumar, R.; Thober, S.; Merz, B.; Samaniego, L. High-resolution impact-based early warning system for riverine flooding. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-C.; Huang, G.-H.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.-P. Effects of watershed subdivision level on semi-distributed hydrological simulations: case study of the SLURP model applied to the Xiangxi River watershed, China. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2013, 59, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.D.; Chowdhury, A.F.M.K.; Galelli, S. On the representation of water reservoir storage and operations in large-scale hydrological models: implications on model parameterization and climate change impact assessments. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 24, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, L.; Bucherie, A.; Libertino, A.; Campo, L.; D'Andrea, M.; Ghizzoni, T.; Gabellani, S.; Massabò, M.; Rossi, L.; Rudari, R.; et al. Operational impact-based flood early warning in Lao PDR and Cambodia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, J.; Miao, C.; Duan, Q.; Tang, Q.; Di, Z.; Liao, W.; Wu, J.; Zhou, R. Sensitivity Analysis-Based Automatic Parameter Calibration of the VIC Model for Streamflow Simulations Over China. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, J.; Miao, C.; Samaniego, L.; Xiao, M.; Wu, J.; Guo, X. CNRD v1.0: A High-Quality Natural Runoff Dataset for Hydrological and Climate Studies in China. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2021, 102, E929–E947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Gou, J.; Fu, B.; Tang, Q.; Duan, Q.; Chen, Z.; Lei, H.; Chen, J.; Guo, J.; Borthwick, A.G.; et al. High-quality reconstruction of China’s natural streamflow. Sci. Bull. 2022, 67, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; de Roo, A.; Miralles, D.G.; McVicar, T.R.; Schellekens, J.; Bruijnzeel, L.A. Global-scale regionalization of hydrologic model parameters. Water Resour. Res. 2016, 52, 3599–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Pan, M.; Lin, P.; Seibert, J.; van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; Wood, E.F. Global Fully Distributed Parameter Regionalization Based on Observed Streamflow From 4,229 Headwater Catchments. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2020, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Fan, C.; Zhu, J.; Wang, J.; Sheng, Y.; Liu, K.; Chen, T.; Zhan, P.; Luo, S.; Yuan, C.; et al. A comprehensive geospatial database of nearly 100 000 reservoirs in China. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 4017–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, P.K.; Samaniego, L.; Rakovec, O.; Kumar, R.; Mi, C.; Rinke, K.; Thober, S. Toward Improved Simulations of Disruptive Reservoirs in Global Hydrological Modeling. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Zhao, T.; Chen, X. Hydrological Model Calibration for Dammed Basins Using Satellite Altimetry Information. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, J. An Operation-Based Scheme for a Multiyear and Multipurpose Reservoir to Enhance Macroscale Hydrologic Models. J. Hydrometeorol. 2012, 13, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Shi, H.; Chen, J.; Li, T. An improved operation-based reservoir scheme integrated with Variable Infiltration Capacity model for multiyear and multipurpose reservoirs. J. Hydrol. 2019, 571, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, F.; Razavi, S.; Elshamy, M.; Davison, B.; Sapriza-Azuri, G.; Wheater, H. Representation and improved parameterization of reservoir operation in hydrological and land-surface models. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 3735–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speckhann, G.A.; Kreibich, H.; Merz, B. Inventory of dams in Germany. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, M.I. , et al., Challenges in modeling and predicting floods and droughts: A review. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Water 2021, 8, e1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyaert, J.C.; Condon, L.E.; Turner, S.W.; Voisin, N. ResOpsUS, a dataset of historical reservoir operations in the contiguous United States. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Yang, M.; Wei, J.; Arnault, J.; Laux, P.; Xu, S.; Wang, H.; Yu, Z.; Kunstmann, H. Toward Improved Parameterizations of Reservoir Operation in Ungauged Basins: A Synergistic Framework Coupling Satellite Remote Sensing, Hydrologic Modeling, and Conceptual Operation Schemes. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, J. An Operation-Based Scheme for a Multiyear and Multipurpose Reservoir to Enhance Macroscale Hydrologic Models. J. Hydrometeorol. 2012, 13, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Pokhrel, Y.; Miguez-Macho, G. High-Resolution Modeling of Reservoir Release and Storage Dynamics at the Continental Scale. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 787–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busker, T.; de Roo, A.; Gelati, E.; Schwatke, C.; Adamovic, M.; Bisselink, B.; Pekel, J.-F.; Cottam, A. A global lake and reservoir volume analysis using a surface water dataset and satellite altimetry. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 669–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Melsen, L.A.; Teuling, A.J. Inferring reservoir filling strategies under limited-data-availability conditions using hydrological modeling and Earth observations: the case of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 4057–4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, M.I.; Naveau, P. Spatial variability in Alpine reservoir regulation: deriving reservoir operations from streamflow using generalized additive models. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, D.T.; Dang, T.D.; Galelli, S.; Hossain, F. Satellite observations reveal 13 years of reservoir filling strategies, operating rules, and hydrological alterations in the Upper Mekong River basin. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 26, 2345–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, M.; Herman, J.D. Modeling the behavior of water reservoir operators via eigenbehavior analysis. Adv. Water Resour. 2018, 122, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, G.; Allen, G.H.; Gao, H. Diminishing storage returns of reservoir construction. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnema, M.; Sikder, S.; Miao, Y.; Chen, X.; Hossain, F.; Pervin, I.A.; Rahman, S.M.M.; Lee, H. Understanding satellite-based monthly-to-seasonal reservoir outflow estimation as a function of hydrologic controls. Water Resour. Res. 2016, 52, 4095–4115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, B. , et al., Global Reservoir and Dam Database, Version 1 (GRanDv1): Dams, Revision 01. Global Reservoir and Dam Database, Version 1 (GRanDv1): Dams, Revision 01, 2011.

- Hanazaki, R.; Yamazaki, D.; Yoshimura, K. Development of a Reservoir Flood Control Scheme for Global Flood Models. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Yamazaki, D.; Pokhrel, Y.; Zhao, G. Improving Global Reservoir Parameterizations by Incorporating Flood Storage Capacity Data and Satellite Observations. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, B.; Beames, P.; Mulligan, M.; Zarfl, C.; De Felice, L.; van Soesbergen, A.; Thieme, M.; de Leaniz, C.G.; Anand, M.; Belletti, B.; et al. The Global Dam Watch database of river barrier and reservoir information for large-scale applications. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.T.; Gu, V.X. Global Dam Tracker: A database of more than 35,000 dams with location, catchment, and attribute information. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawker, L.; Uhe, P.; Paulo, L.; Sosa, J.; Savage, J.; Sampson, C.; Neal, J. A 30 m global map of elevation with forests and buildings removed. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 024016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. , Water Conservancy Gazetteer of Hainan Province (2001–2010). Hainan Provincial Local Chronicles. 2013, Haikou: Local Chronicles Publishing House. 353.

- Jiang, X.; Ren, F.; Li, Y.; Qiu, W.; Ma, Z.; Cai, Q. Characteristics and Preliminary Causes of Tropical Cyclone Extreme Rainfall Events over Hainan Island. Adv. Atmospheric Sci. 2018, 35, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, B.; Liermann, C.R.; Revenga, C.; Vorosmarty, C.; Fekete, B.; Crouzet, P.; Döll, P.; Endejan, M.; Frenken, K.; Magome, J.; et al. High-resolution mapping of the world's reservoirs and dams for sustainable river-flow management. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 9, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaperow, J.R.; Li, D.; Margulis, S.A.; Lettenmaier, D.P. A near-global, high resolution land surface parameter dataset for the variable infiltration capacity model. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehner, B.; Verdin, K.; Jarvis, A. New Global Hydrography Derived From Spaceborne Elevation Data. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 2008, 89, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Kimball, J.S.; Mantua, N.; Stanford, J. Automated upscaling of river networks for macroscale hydrological modeling. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Kimball, J.S.; Li, H.; Huang, M.; Leung, L.R.; Adler, R.F. A new global river network database for macroscale hydrologic modeling. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, G.J. , et al., NASA Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Integrated Multi-satellitE Retrievals for GPM (IMERG) Version 07. 2023.

- Huffman, G.J. , et al., Integrated Multi-satellite Retrievals for the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Mission (IMERG), in Satellite Precipitation Measurement: Volume 1, V. Levizzani, et al., Editors. 2020, Springer International Publishing: Cham. p. 343-353.

- Shen, Y.; Liu, D.; Jiang, L.; Nielsen, K.; Yin, J.; Liu, J.; Bauer-Gottwein, P. High-resolution water level and storage variation datasets for 338 reservoirs in China during 2010–2021. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 5671–5694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, O.E.J.; Bates, P.D.; Quinn, N.D.; Savage, J.T.S.; Uhe, P.F.; Cooper, A.; Collings, T.P.; Addor, N.; Lord, N.S.; Hatchard, S.; et al. A 30 m Global Flood Inundation Model for Any Climate Scenario. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Lettenmaier, D.P.; Wood, E.F.; Burges, S.J. A simple hydrologically based model of land surface water and energy fluxes for general circulation models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1994, 99, 14415–14428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. , et al., From China’s Heavy Precipitation in 2020 to a “Glocal” Hydrometeorological Solution for Flood Risk Prediction. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences 2021, 38, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wu, H.; Alfieri, L.; Gu, G.; Yilmaz, K.K.; Li, C.; Jiang, L.; Huang, Z.; Chen, W.; Wu, W.; et al. A time-space varying distributed unit hydrograph (TS-DUH) for operational flash flood forecasting using publicly-available datasets. J. Hydrol. 2024, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wu, H.; Tao, J.; Kimball, J.S.; Alfieri, L.; Chen, X. Satellite-Based Evapotranspiration in Hydrological Model Calibration. Remote. Sens. 2020, 12, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, Z.; Revilla-Romero, B.; Salamon, P.; Burek, P.; Hirpa, F.A.; Beck, H. The impact of lake and reservoir parameterization on global streamflow simulation. J. Hydrol. 2017, 548, 552–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, N.; Wei, J.; Yang, M.; Yan, D.; Yang, C.; Gao, H.; Arnault, J.; Laux, P.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Model Estimates of China's Terrestrial Water Storage Variation Due To Reservoir Operation. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; Beck, H.E.; Renzullo, L.J.; Wada, Y. Remotely sensed reservoir water storage dynamics (1984–2015) and the influence of climate variability and management at a global scale. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 26, 3785–3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busker, T.; de Roo, A.; Gelati, E.; Schwatke, C.; Adamovic, M.; Bisselink, B.; Pekel, J.-F.; Cottam, A. A global lake and reservoir volume analysis using a surface water dataset and satellite altimetry. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 669–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Long, D.; Huang, Q.; Han, P.; Zhao, F.; Wada, Y. High-temporal-resolution water level and storage change data sets for lakes on the Tibetan Plateau during 2000–2017 using multiple altimetric missions and Landsat-derived lake shoreline positions. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1603–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H. Satellite remote sensing of large lakes and reservoirs: from elevation and area to storage. WIREs Water 2015, 2, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Song, C.; Wang, J.; Ke, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ma, R.; Luo, Z. Remote Sensing-Based Modeling of the Bathymetry and Water Storage for Channel-Type Reservoirs Worldwide. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, F.N.; Butland, J. A Method for Constructing Local Monotone Piecewise Cubic Interpolants. SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comput. 1984, 5, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Sorooshian, S.; Gupta, V. Effective and efficient global optimization for conceptual rainfall-runoff models. Water Resour. Res. 1992, 28, 1015–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J. and R. Eberhart. Particle swarm optimization. in Proceedings of ICNN’95 - International Conference on Neural Networks. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, N.K.; Hossain, F.; Bonnema, M.; Lee, H.; Chishtie, F. Towards a global Reservoir Assessment Tool for predicting hydrologic impacts and operating patterns of existing and planned reservoirs. Environ. Model. Softw. 2021, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaei, B.; Read, L.K.; Casali, M.; Sampson, K.M.; Yates, D.N. GLOBathy, the global lakes bathymetry dataset. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigzaw, W.; Li, H.; Demissie, Y.; Hejazi, M.I.; Leung, L.R.; Voisin, N.; Payn, R. A New Global Storage-Area-Depth Data Set for Modeling Reservoirs in Land Surface and Earth System Models. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 10–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Chen, F.; Jia, X.; Cai, X.; Yang, C.; Du, Y.; Ling, F. GRDL: A New Global Reservoir Area-Storage-Depth Data Set Derived Through Deep Learning-Based Bathymetry Reconstruction. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassoni-Andrade, A.C.; de Paiva, R.C.D.; Fleischmann, A.S. Lake Topography and Active Storage From Satellite Observations of Flood Frequency. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Gleason, C.J. More flow upstream and less flow downstream: The changing form and function of global rivers. Science 2024, 386, 1305–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Pavelsky, T.; Cretaux, J.; Morrow, R.; Farrar, J.T.; Vaze, P.; Sengenes, P.; Vinogradova-Shiffer, N.; Sylvestre-Baron, A.; Picot, N.; et al. The Surface Water and Ocean Topography Mission: A Breakthrough in Radar Remote Sensing of the Ocean and Land Surface Water. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Unit | Calibration Range | Default Value in baseline-run |

| Binfilt | N/A | 0.01–1.0 | 0.2 |

| Ds | fraction | 0.01–1.0 | 1 |

| Dsmax | mm/day | 0.01–50.0 | 10 |

| Ws | fraction | 0.01–1.0 | 0.65 |

| d2 | m | 0.30–2.0 | 1.5 |

| d3 | m | 0.30–2.0 | 1.5 |

| Simulation Scenario | NSE | KGE | CC | PBIAS | RMSE | ||||||||||

| Cali. | Vali. | Cali. | Vali. | Cali. | Vali. | Cali. | Vali. | Cali. | Vali. | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.79 | 0.76 | -1.41 | 3.84 | 276.63 | 240.11 | |||||

| CWOD | 0.84 | 0.72 | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 12.92 | 11.99 | 160.56 | 175.88 | |||||

| CWD | 0.84 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 7.96 | 9.41 | 162.90 | 157.69 | |||||

| Scenario | Parameter | |||||

| Binfilt | Ds | Dsmax | Ws | d2 | d3 | |

| CWOD | 0.44 | 0.43 | 31.80 | 0.11 | 1.49 | 0.54 |

| CWD | 0.12 | 0.05 | 5.65 | 0.95 | 0.69 | 1.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).