1. Introduction

Precipitation plays a critical role in the hydrological cycle [1, 2] and is the most essential input for runoff simulation [

3]. Accurate precipitation data enhances the reliability of hydrological simulations [

4], facilitating sustainable water resource management and water-related risk prediction [

5]. Historically, precipitation datasets for hydrologic models have primarily relied on gauge observations [

6]. However, economic and geographical limitations often result in sparse and unevenly distributed rain gauge stations in underdeveloped countries and remote mountainous areas [

7].

Advances in observational techniques and inverse algorithms have enabled the development of precipitation products from gauge stations, reanalysis, and satellites, offering unprecedented opportunities for global and regional-scale real-time monitoring and flood-drought warnings. Gauge-based precipitation products, such as those from the Climate Prediction Center (CPC) [

8], utilize data from global gauge stations and various interpolation techniques, with accuracy primarily determined by gauge station density and quantity [

9]. Recent years have seen growing research interest in developing reanalysis products through numerical weather models and data assimilation techniques. These methods offer an alternative to traditional observations, enabling more detailed and accurate analysis of weather patterns and trends [

10]. Ongoing enhancements to the Integrated Forecast System (IFS) in modeling processes, core dynamics, and data assimilation [

11] have made the publicly available ERA5 dataset one of the most advanced resources.

Satellite precipitation products integrate high-resolution spatiotemporal infrared imagery with accurate passive microwave precipitation estimates [

12], offering advantages such as spatial continuity, global coverage, and near-real-time data acquisition compared to ground-based observations [

13]. Currently, widely used satellite products include the Climate Hazards Group Infrared Precipitation with Station data (CHIRPS), Global Satellite Mapping of Precipitation (GSMaP), and Integrated Multi-satellitE Retrievals for GPM (IMERG). The Multi-Source Weighted-Ensemble Precipitation (MSWEP) dataset, which integrates observational, satellite, and reanalysis data, also provides reliable global precipitation estimates.

Numerous studies have examined the impact of various precipitation inputs on hydrological simulations, utilizing both single and combined products [

14]. Zeng et al. (2024) [

15] assessed the performance of nine gridded precipitation products in hydrological simulations across four Gandaki River Basin sub-basins using the HBV model. The results revealed significant variations among the precipitation datasets, with ERA5-Land, IMERGEF V06, and MSWEP V2.8 showing superior performance in both precipitation estimation and hydrological simulation. Aryal et al. (2023) [

16] employed the SWAT model to assess streamflow predictions from four satellite-derived precipitation products in the Myagdi Khola Basin. The results demonstrated that satellite-based products effectively predicted streamflow in complex basins, with corrected precipitation products showing superior performance and better adaptability in Himalayan watersheds. While these precipitation products have been widely used in semi-distributed hydrological models, their application in fully distributed models remains limited. Moreover, their performance is constrained by errors, indicating potential for further improvement [

17].

Integration-based methods synthesize information from multiple sources, with merged precipitation products generally outperforming single-source products [

18]. The BMA method is a weighted ensemble approach that aligns ensemble predictions with observed data through relative model capability assessment and weight optimization [

19]. Compared to traditional ensemble methods, BMA more effectively incorporates weight uncertainty into estimations, resulting in improved performance [

20]. Recently, numerous researchers have applied the BMA approach to enhance precipitation estimation. Ma et al. (2018) [

21] employed the dynamic BMA algorithm in a hybrid experiment with multi-satellite precipitation data. The results demonstrated that dynamic BMA data reduced errors compared to ensemble members, outperforming both SMA and OOR methods in generating precipitation ensembles, particularly beneficial for merging multi-satellite data in sparsely observed regions. Yumnam et al. (2022) [

22] introduced a Quantile-based Bayesian Model Averaging (QBMA) method to blend three satellite precipitation products in the Vamsadhara Basin. Their findings indicated that QBMA products, with bias-corrected inputs, reduced errors and outperformed IMERG products. Wei et al. (2023) [

23] developed a modifiable BMA framework, employing optimal weights and variable initial comparison methods to quantitatively assess different input impacts on BMA predictions. The results revealed significant variations in BMA prediction performance based on input sources, with CPC emerging as the primary influencing factor. However, BMA-based merged precipitation products have been rarely applied in hydrological simulations. Assessing the impact of BMA-merged precipitation products on runoff simulation is both valuable and essential.

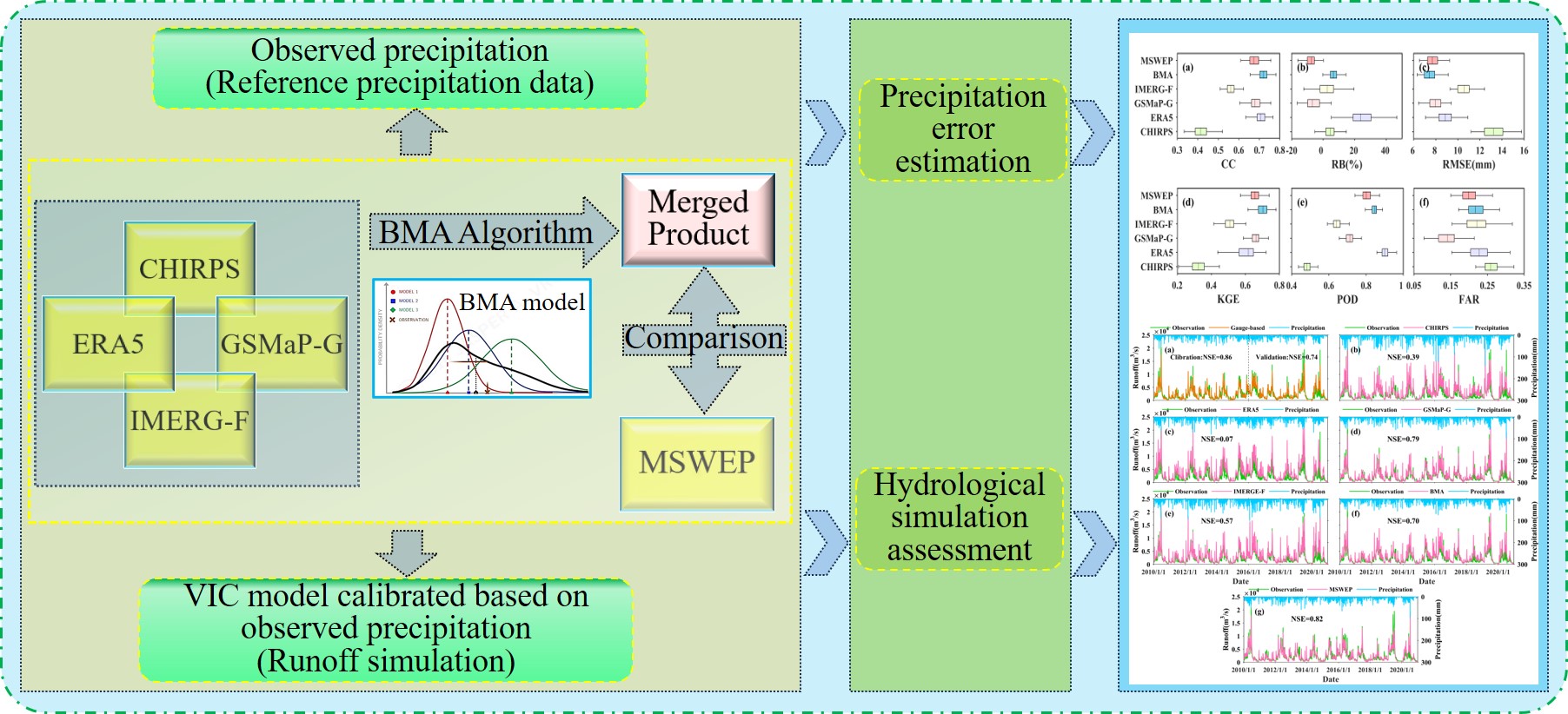

This study employs the BMA algorithm as the core framework for integrating multiple precipitation datasets to create a merged precipitation product. A combined approach of precipitation estimation and hydrological simulation is utilized to evaluate the merged product's applicability in the study area. The experimental design incorporates four precipitation datasets (CHIRPS, ERA5, GSMaP, and IMERG) from 2008 to 2020. The ensemble precipitation product MSWEP serves as a comparative dataset, with the Ganjiang River Basin in China selected as the study area. Multiple metrics are employed to assess the BMA-merged product's capability in estimating precipitation across daily, monthly, and seasonal timescales. The widely adopted VIC distributed hydrological model [

6,

24] is then used to evaluate the merged precipitation product's effectiveness in simulating daily and monthly runoff. Finally, the error propagation ratio is applied to analyze how different products mitigate errors from precipitation to runoff. The study's findings are anticipated to offer more reliable precipitation estimates, contributing to enhanced hydrological understanding and improved precipitation input for regional hydrological simulations.

2. Study area and data

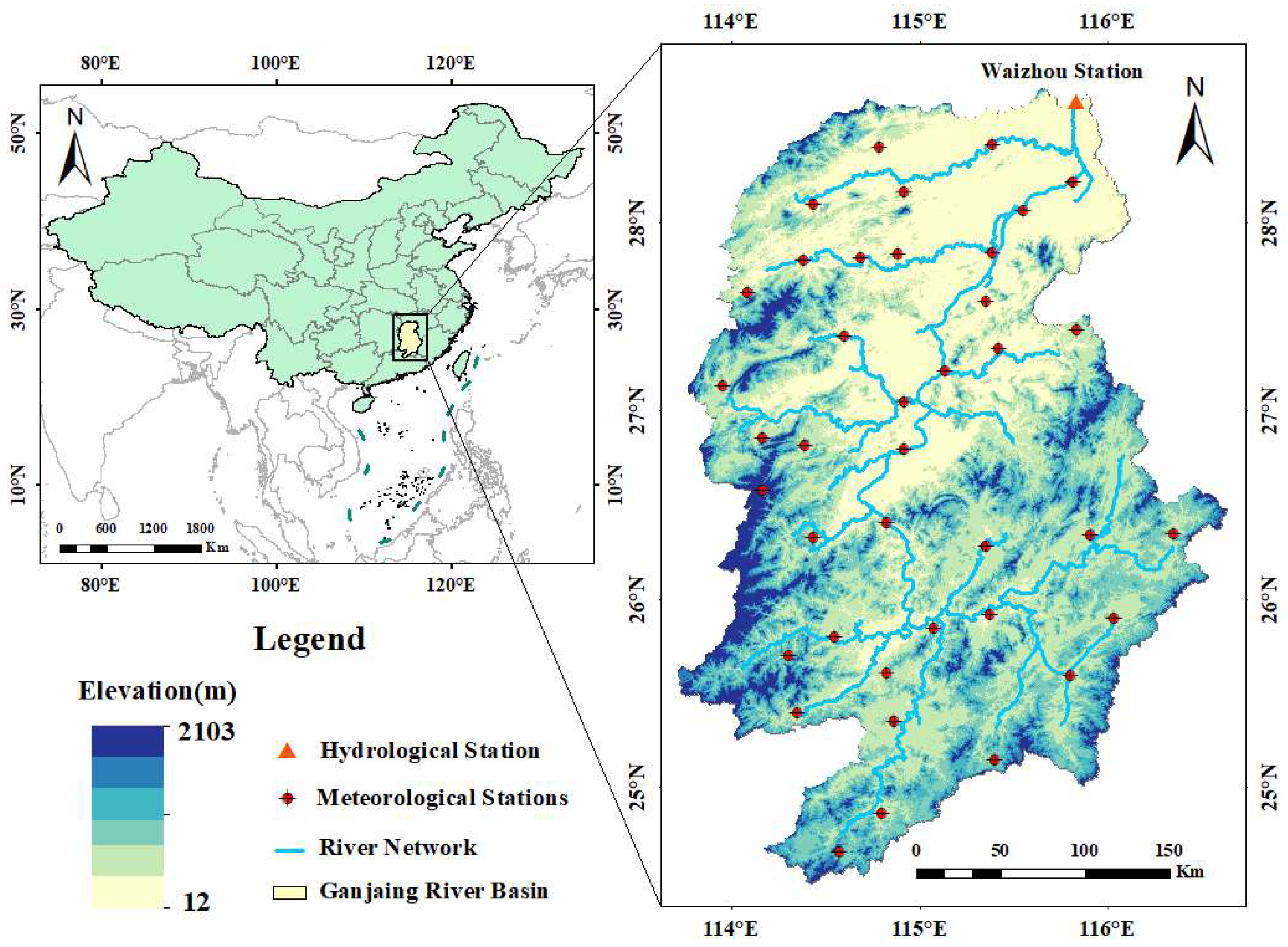

2.1. Study Area

The Ganjiang River, the seventh-largest tributary of the Yangtze River, is situated in Jiangxi Province, southeastern China. The Ganjiang River Basin spans approximately 83,385 km², monitored by the Waizhou Hydrological Station (115.84°E, 28.63°N). Elevation ranges from 12 to 2,103 m (

Figure 1), with higher elevations in the south and lower elevations in the north. The Ganjiang River Basin's landscape is characterized by mountains and hills (64.7%), low hills (31.5%, below 200 m above sea level), and plains and water bodies (3.9%). The average temperature is approximately 18°C, with annual precipitation ranging from 1,400 to 1,800 mm.

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Ground Observation Data

Precipitation data from 2008 to 2020 were obtained from the China Gauge-based Daily Precipitation Analysis (CGDPA), developed by the China Meteorological Administration (CMA) (

https://data.cma.cn/). The dataset features a 0.25°/24h spatiotemporal resolution and undergoes rigorous quality control for extreme values, internal consistency, and spatial consistency [

25]. Daily maximum and minimum temperatures and average wind speed data were also obtained from the CMA, subject to strict quality control before publication.

2.2.2. Satellite, Reanalysis and Ensemble Precipitation Products

In this study, error analysis was conducted at a 0.25° spatial resolution. Therefore, all precipitation products were resampled to a 0.25° spatial resolution and aggregated to a daily temporal resolution before error calculation. Basic information on the evaluated products is presented in

Table 1.

CHIRPS, initially designed for agricultural drought detection, combines improved inverse-distance weighting (IDW) interpolation with precipitation estimates derived from infrared cold cloud duration (CCD) retrievals [

26], aiming to provide a comprehensive, credible, and timely precipitation dataset. The latest version, CHIRPS 2.0, with a spatial resolution of 0.25°, is available at

https://data.chc.ucsb.edu/products/CHIRPS-2.0.

ERA5, the latest generation of atmospheric reanalysis products, employs improved four-dimensional data assimilation. It integrates model data with global observations, offering broader temporal coverage (1950–present) and superior spatiotemporal resolution (0.25°/1h) compared to ERA-Interim (0.76°/6h) [

27]. The data are available at

https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47.

The satellite-based precipitation products from the GSMaP project are developed by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). JAXA aims to create high-resolution global precipitation maps by integrating core satellite data from the GPM program with joint infrared and multi-band passive microwave algorithms, including front-back deformation techniques and Kalman filters [

28]. The GSMaP-Gauge (GSMaP-G) data used in this study are available at

https://sharaku.eorc.jaxa.jp/GSMaP.

IMERG, an algorithm for GPM, generates third-level products with the goal of producing advanced global precipitation datasets. IMERG combines precipitation estimates from multiple microwave sensors, microwave-corrected infrared satellite data, and monthly rain gauge observations, calibrated using its algorithm [

29]. IMERG operates in three stages: Early, Later, and Final. This study uses IMERG Final Run Version 06B (IMERG-F), available for free download from NASA’s official website:

https://doi.org/10.5067/GPM/IMERG/3B-HH/06.

MSWEP, a comprehensive global precipitation dataset developed by the Beck team, employs a multi-source weighted-ensemble approach, integrating nearly all available precipitation observations [

18]. It uniquely integrates gauge, satellite, and reanalysis data to produce highly accurate precipitation estimates for each location [

30]. This study uses MSWEP version 2.8 as the benchmark, reflecting the BMA precipitation merging effect. Compared to earlier versions, MSWEP 2.8 features reduced peak precipitation values, extended record lengths, and near real-time updates. The data are available at

https://www.gloh2o.org/mswep/.

2.2.3. Runoff Data and Others

Daily runoff data for the VIC model were obtained from the Waizhou Station in Jiangxi Province (2008–2020). Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data for the Ganjiang River Basin were sourced from the Geospatial Data Cloud (

https://www.gscloud.cn/) at a 90 m resolution. Land cover parameters, including vegetation types and leaf area index (LAI), were obtained from the Global Land Cover Classification dataset (1 km resolution;

http://www.landcover.org/data/landcover). Soil data were extracted from the Harmonized World Soil Database (HWSD), published by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO;

http://www.fao.org/soils-portal/data-hub).

3. Methods

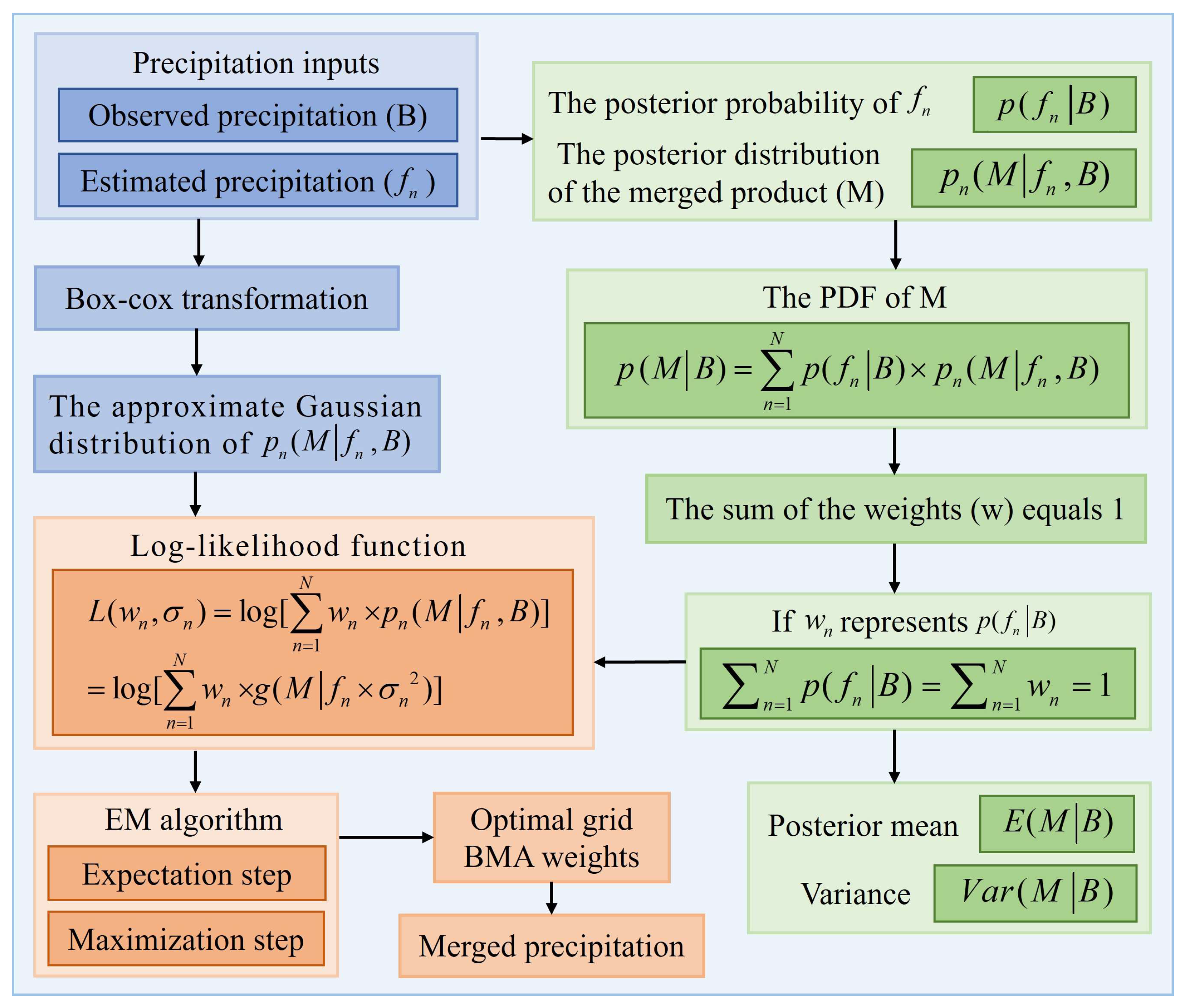

3.1. Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA)

Based on Bayesian theory, the statistical ensemble model BMA combines inference and prediction based on ensemble membership to obtain a more reliable probability set [

31]. In this study, the BMA method with adjusted posterior probability density function (PDF) is used to merge multi-source precipitation datasets for better fit with ground observations. According to the law of total probability, the PDF of BMA-merged precipitation product is expressed as:

Where M represents the merged precipitation product; B represents the observed precipitation; N is the number of precipitation inputs; represents the precipitation estimates of the nth member; denotes the posterior probability of the precipitation input, and determined as the likelihood of the ensemble members; represents the posterior distribution of from estimated and observed precipitation.

Each member's posterior probability is determined using observations from the same period, guaranteeing that the sum of the weights equals 1. If

represents

, and

, then the formula can be written as:

Moreover, the posterior mean

and variance

of the merged product can be written as:

Where represents the variability between the estimated and observed precipitation.

Generally, the prior probability distribution of precipitation does not conform to the Gaussian assumption and is normally distributed. Before executing the BMA algorithm, it is necessary to perform a Box-Cox transformation on the original and observed precipitation data to obtain an approximate Gaussian distribution of

. The weights of the input precipitation dataset can be effectively estimated using the maximum likelihood function:

Where,

represents the Gaussian distribution. The EM algorithm iterated through the E (expectation) and the M (maximization) steps until the log-likelihood equation was maximized [

32,

33]. During the iterative process, the prior BMA weights of single members were set to 1/

N. The detailed process of the BMA algorithm is shown in

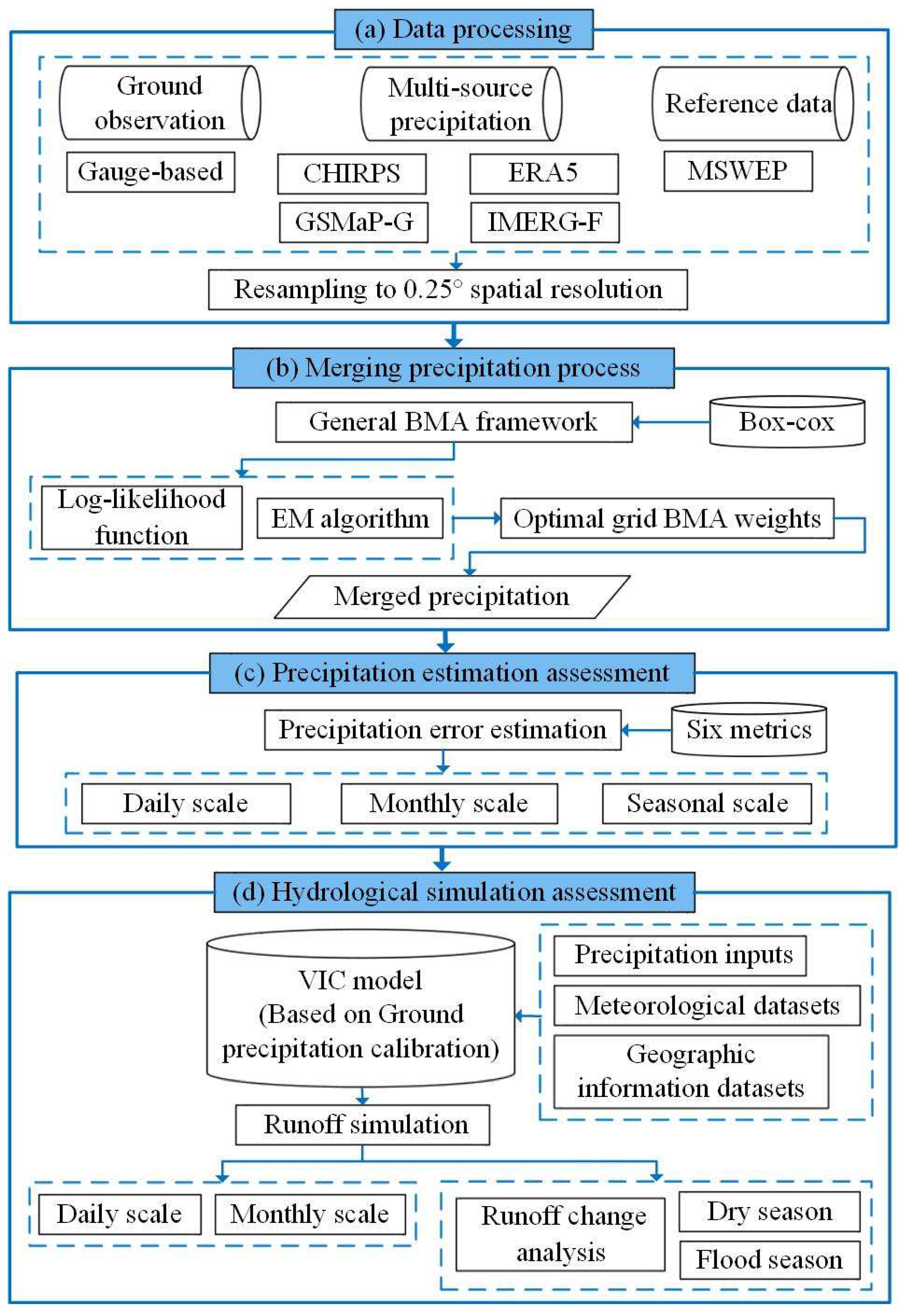

Figure 2.

3.2 VICHydrologicalModel

The VIC distributed hydrological model, with its large-scale, gridded, and physically robust characteristics, facilitates integration with various climate models, enabling the consideration of comprehensive effects from weather, soil, terrain, and vegetation. Furthermore, the model effectively addresses complex application scenarios, making it ideal for long-term hydrological and material cycle studies. Owing to these advantages, the VIC model, since its inception in 1994, has been widely applied in runoff simulation and effectively used to evaluate the hydrological impacts of precipitation products [

34].

Version 4.2d of the VIC model is employed in this study, using original station-observed precipitation data, BMA-merged precipitation data, precipitation data from four ensemble members, and MSWEP precipitation data at daily and monthly scales. To optimize model parameters, observed precipitation data are used as inputs for the warm-up (2008–2009), calibration (2010–2015), and validation (2016–2020) periods. The Shuffled Complex Evolution (SCE-UA) algorithm is utilized to optimize model parameters, using the Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE) as the objective function. To ensure a fair assessment, the same initial ranges are applied to soil parameter values across different precipitation inputs (

Table 2).

3.3 EvaluationMetrics

The evaluation metrics in this study are categorized into two types: accuracy assessment of precipitation estimation and accuracy assessment of VIC model runoff simulation. This study employs six metrics—CC, RB, RMSE, KGE, POD, and FAR—to assess the consistency between estimated and observed precipitation. CC measures the degree of linear correlation, RB evaluates systematic deviation, RMSE represents the average error, KGE integrates linear correlation, systematic bias, and total error, POD indicates the correct detection of rainfall events, and FAR identifies false detection. For calculating POD and FAR, a threshold of 1 mm/day is set to determine the occurrence of rain/no-rain events. The Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE) is employed to evaluate the performance of the VIC model runoff simulation. Descriptions, equations, and value ranges of the metrics are provided in

Table 3.

Table 2.

Soil parameter variables of the VIC model and their initial value ranges.

Table 2.

Soil parameter variables of the VIC model and their initial value ranges.

| Parameters |

Unit |

Description |

Value range |

b_infilt

Dsmax

|

-

mm/day |

Variable infiltration capacity curve

Maximum velocity of base flow |

[0.1, 0.4]

[0, 30] |

| Ds

|

- |

Fraction of Dsmax where non-linear

baseflow begins |

[0.1, 1] |

| Ws

|

- |

Fraction of maximum soil moisture

where non-linear baseflow occurs |

[0.1, 1] |

| D2

|

m |

The second soil-layer thickness |

[0.1, 1] |

| D3

|

m |

The third soil-layer thickness |

[0.1, 3] |

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the methodology used in this study.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the methodology used in this study.

4. Results

4.1. Accuracy Evaluation of Precipitation Estimation for Different Products

4.1.1. Daily Scale Evaluation

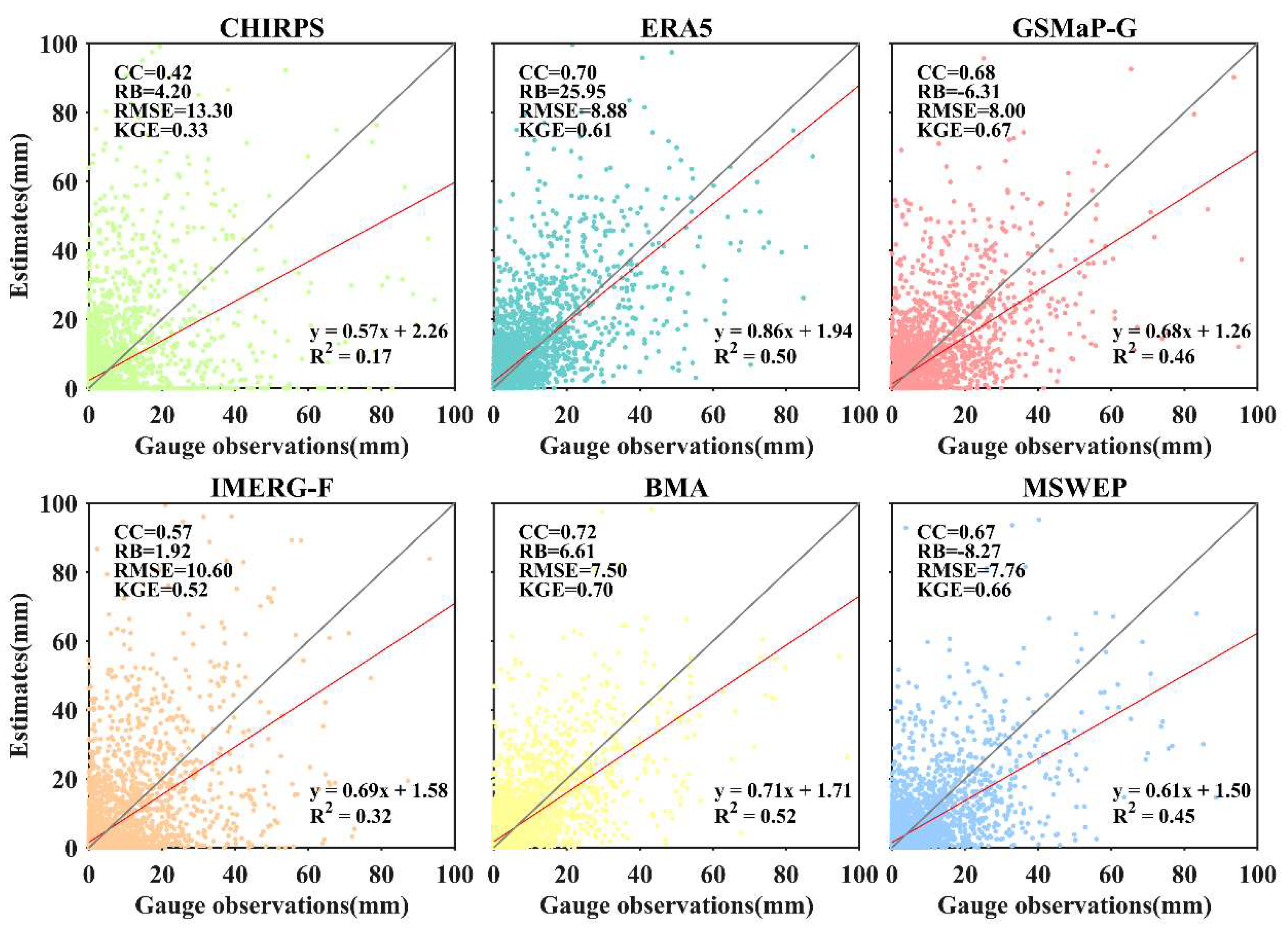

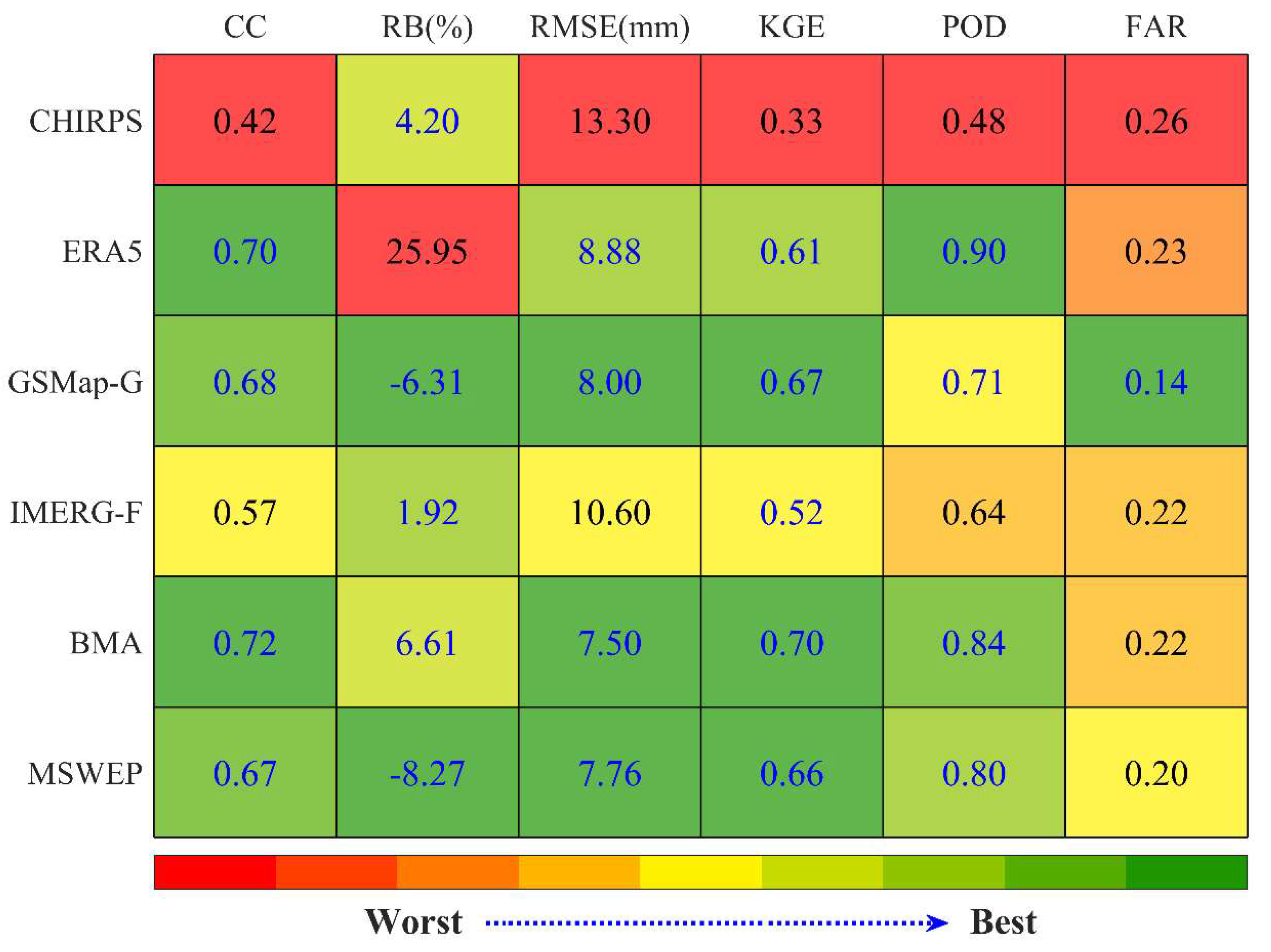

Figure 4 presents the average daily metrics performance for the BMA-merged product (hereafter BMA), its ensemble members, and MSWEP in the study area (2008–2020). Compared to individual products, BMA demonstrates significant advantages across multiple metrics, achieving the highest CC (0.72) and KGE (0.70), the smallest RMSE (7.50 mm), and outperforming most products in RB (6.61%), POD (0.84), and FAR (0.22). Some products exhibit unique strengths: IMERG-F has the lowest RB, ERA5 achieves the highest POD, and GSMaP-G records the smallest FAR. MSWEP performs well across most metrics, whereas CHIRPS demonstrates poor performance.

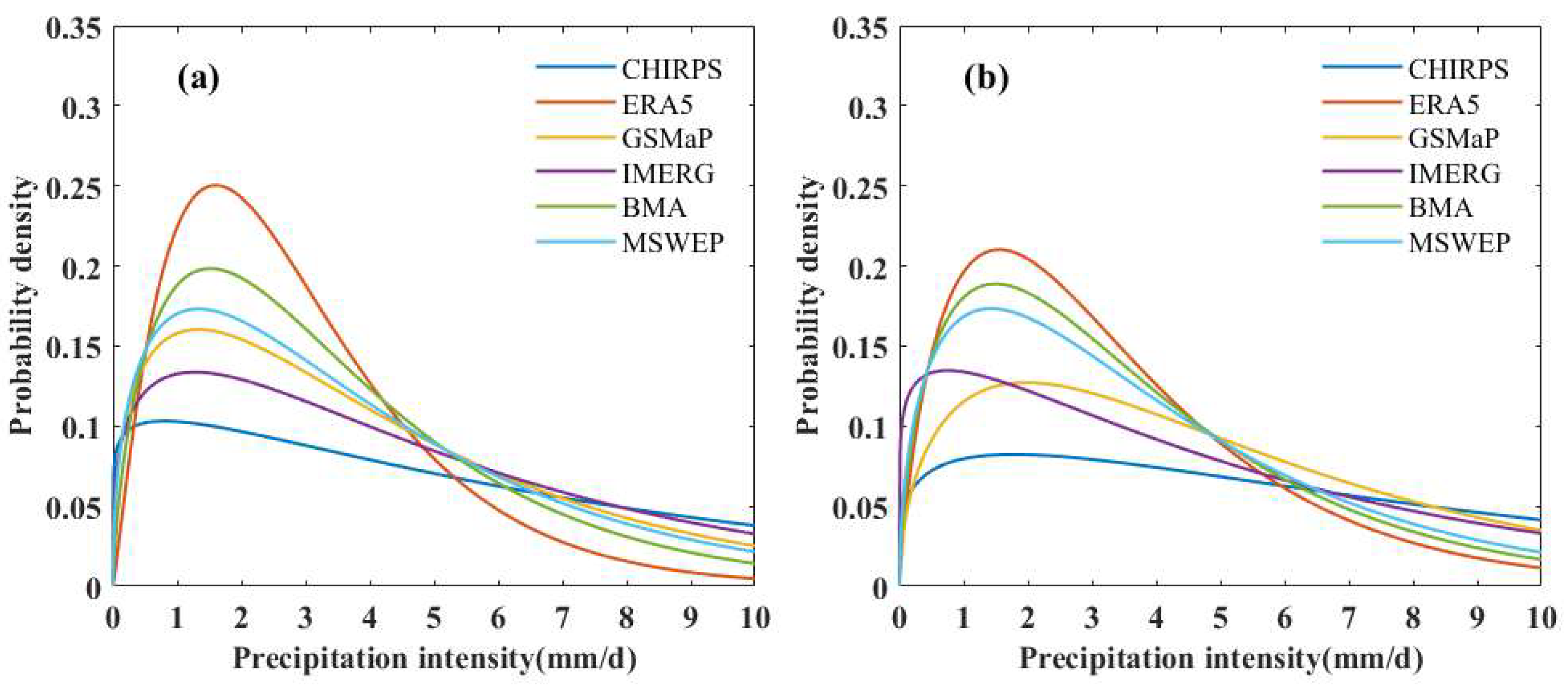

Figure 5 illustrates the probability distributions of precipitation intensity for missed [

35] and false alarm events across different products. CHIRPS, GSMaP-G, and IMERG-F show broad, flat probability distributions for both missed and false alarm events, indicating significant uncertainty in their precipitation estimates. Compared to other products, ERA5 exhibits higher RB and FAR, with a greater tendency for missed and false alarms during light rainfall (<10 mm/d). BMA displays a relatively narrow distribution and outperforms MSWEP in reducing missed and false positives.

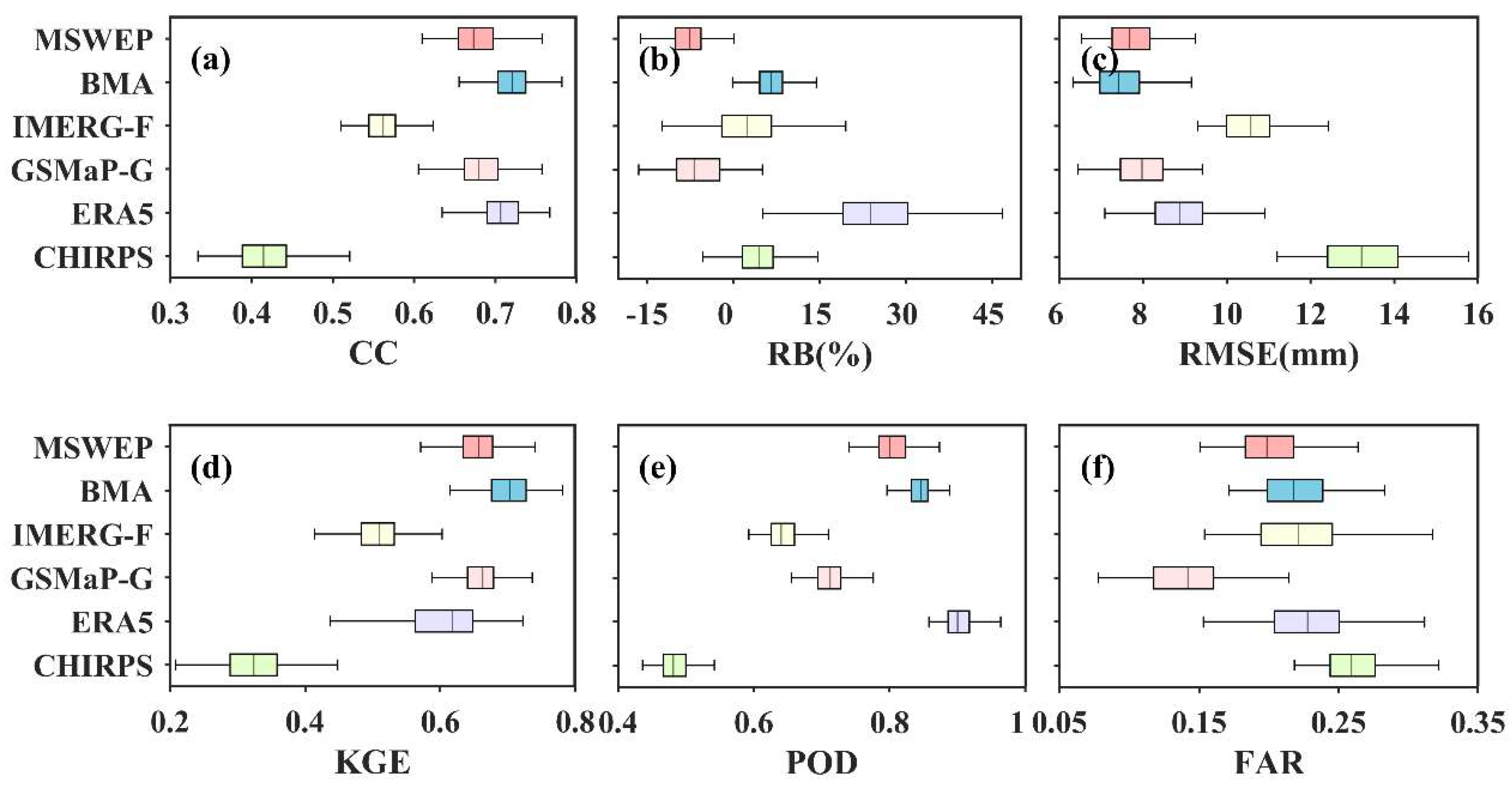

Figure 6 presents box plots of evaluation metrics for different products at the daily scale. While CHIRPS and IMERG-F perform poorly, IMERG-F’s median RB is closest to 0 (

Figure 6b). GSMaP-G performs well overall and achieves the lowest FAR among all products (

Figure 6f). ERA5 exhibits significant positive bias, severely overestimating daily precipitation in the study area, which likely contributes to its highest POD (

Figure 6b, 6e). Downscaling may reduce ERA5’s overestimation but could degrade its precipitation detection performance [

11]. BMA performs excellently across all metrics, demonstrating superior CC, RMSE, and KGE compared to MSWEP and its ensemble members, effectively addressing the limitations of CHIRPS and ERA5 with high reliability.

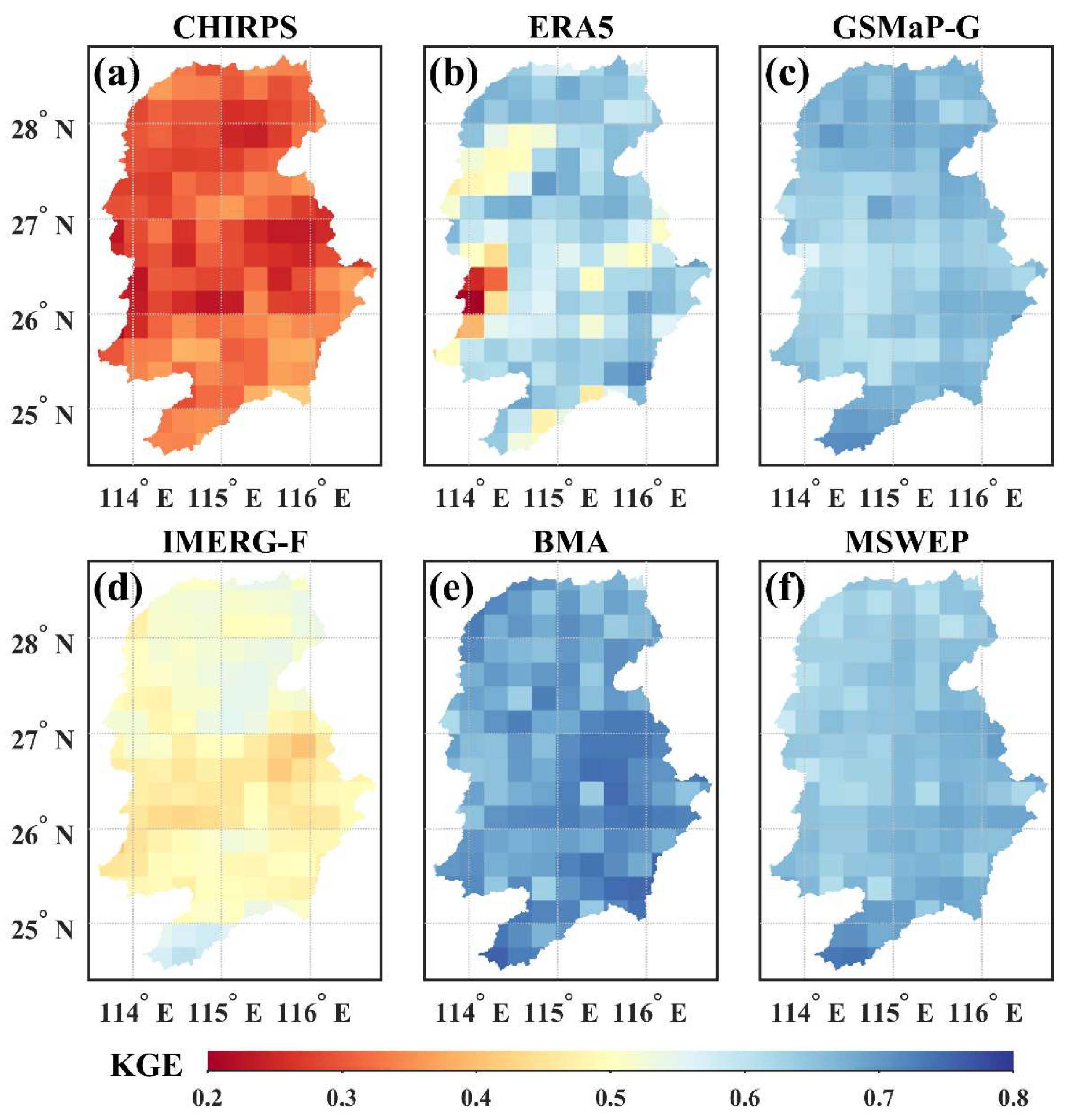

The KGE, a comprehensive metric, is widely used to assess the accuracy of precipitation products and demonstrates strong applicability across diverse river basins and hydrological environments. To analyze the spatial distribution of evaluation metrics within the basin, a KGE distribution map for six products is presented. As shown in

Figure 7, CHIRPS shows poor applicability in the study area, with KGE values mostly below 0.4. ERA5’s KGE values fluctuate significantly, exhibiting a highly uneven spatial distribution. GSMaP-G and MSWEP exhibit similar spatial distributions, with most KGE values ranging from 0.6 to 0.7, indicating good performance. BMA demonstrates excellent adaptability within the basin, with most regions showing KGE values above 0.7 and a uniform spatial distribution. The results indicate that, compared to other products, BMA offers superior precipitation estimation capabilities in the study area, highlighting its potential for hydrological modeling.

Figure 8 shows the spatial distributions of average daily precipitation in the Ganjiang River Basin (2008–2020) for gauge-based observations (hereafter Gauge-based), BMA, ensemble members, and MSWEP. Overall, all products show a similar spatial pattern, with relatively scarce precipitation in the south and abundant precipitation in the north. Gauge-based observations indicate average daily precipitation of 4–5.5 mm in the study area. Compared to Gauge-based, ERA5 significantly overestimates precipitation in most regions, with daily averages reaching 8 mm in some areas, while GSMaP-G underestimates precipitation across much of the region. IMERG-F’s average daily precipitation closely matches Gauge-based observations, but its distribution increases from southwest to northeast. MSWEP exhibits a highly uniform precipitation distribution across the basin, with daily averages of approximately 4.5 mm, slightly lower than Gauge-based. Both CHIRPS and BMA show precipitation estimates and spatial distributions close to Gauge-based, validating the applicability and feasibility of BMA’s spatial distribution.

Figure 9 presents scatter plots and evaluation metrics comparing Gauge-based observations with BMA, ensemble members, and MSWEP, illustrating the correlation and dispersion between estimated and observed precipitation. Compared to MSWEP and ensemble members, BMA’s precipitation estimates align most closely with Gauge-based observations, showing the highest correlation and lowest dispersion. ERA5 ranks second in precipitation estimation, showing high correlation and low dispersion but also significant RB. GSMaP-G and MSWEP deliver superior precipitation estimates, performing well across all metrics. CHIRPS and IMERG-F produce poor precipitation estimates, deviating significantly from observed values.

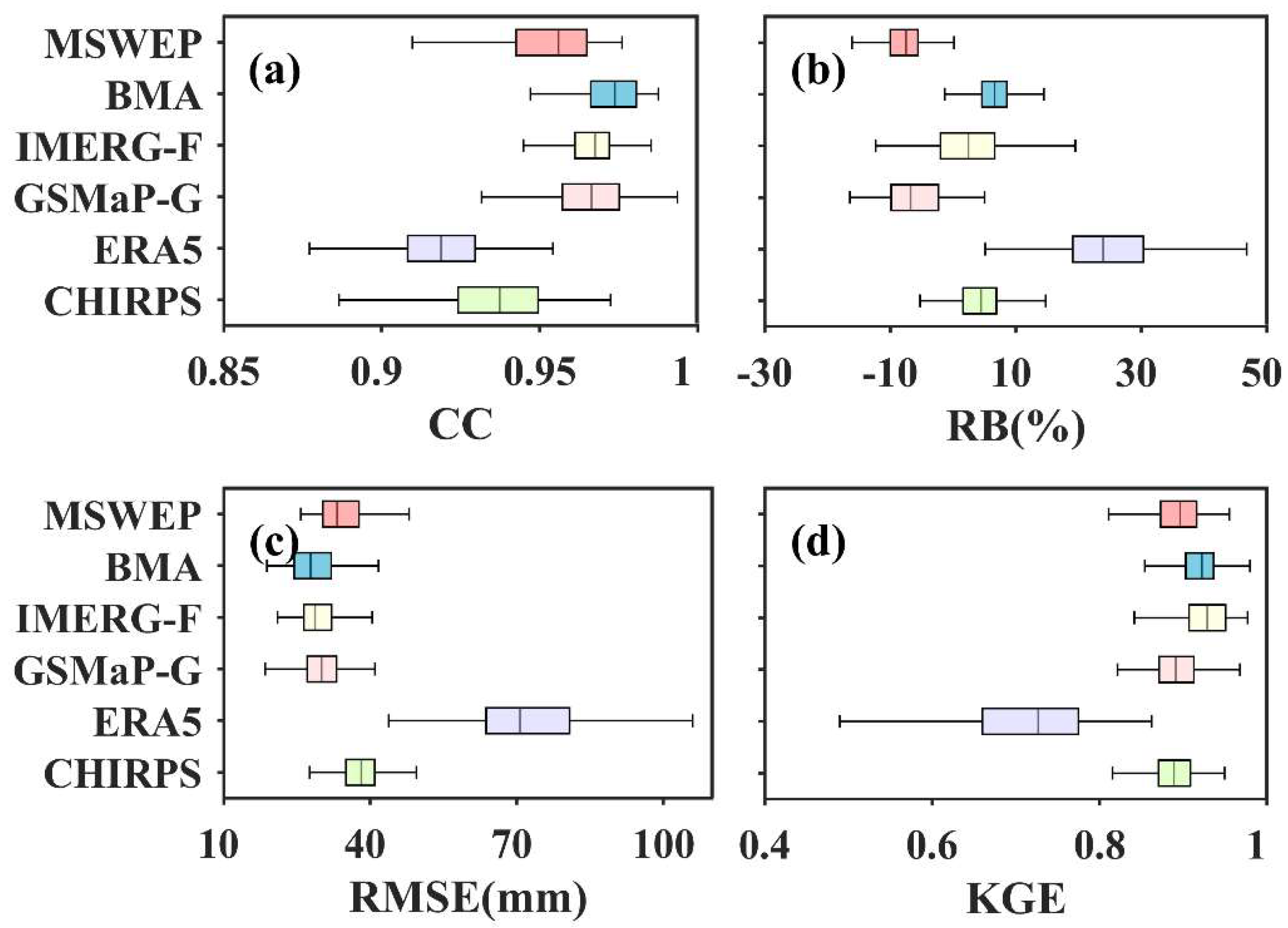

4.1.2. Monthly Scale Evaluation

As shown in

Table 4, BMA and other precipitation products exhibit significantly higher consistency with observed precipitation at the monthly scale compared to the daily scale. Even CHIRPS, which performs poorly at the daily scale, achieves CC and KGE values above 0.90 at the monthly scale. IMERG-F’s accuracy at the monthly scale far exceeds its daily performance, with RB and KGE reaching 1.93% and 0.95, respectively. Compared to MSWEP, BMA shows higher compatibility with observed precipitation, achieving the highest CC, smallest RMSE, and best characterization of monthly precipitation.

Figure 10 presents box plots of evaluation metrics for different precipitation products at the monthly scale. Compared to other products, BMA achieves the best performance in CC, RB, and RMSE, with KGE second only to IMERG-F. ERA5 performs significantly worse than other products, exhibiting low accuracy, large deviation, and low availability. The results demonstrate that BMA provides reliable precipitation estimates at the monthly scale, closely matching observed precipitation.

Figure 9.

Scatter plots of gauge-based precipitation and six precipitation products at the daily scale (2008–2020).

Figure 9.

Scatter plots of gauge-based precipitation and six precipitation products at the daily scale (2008–2020).

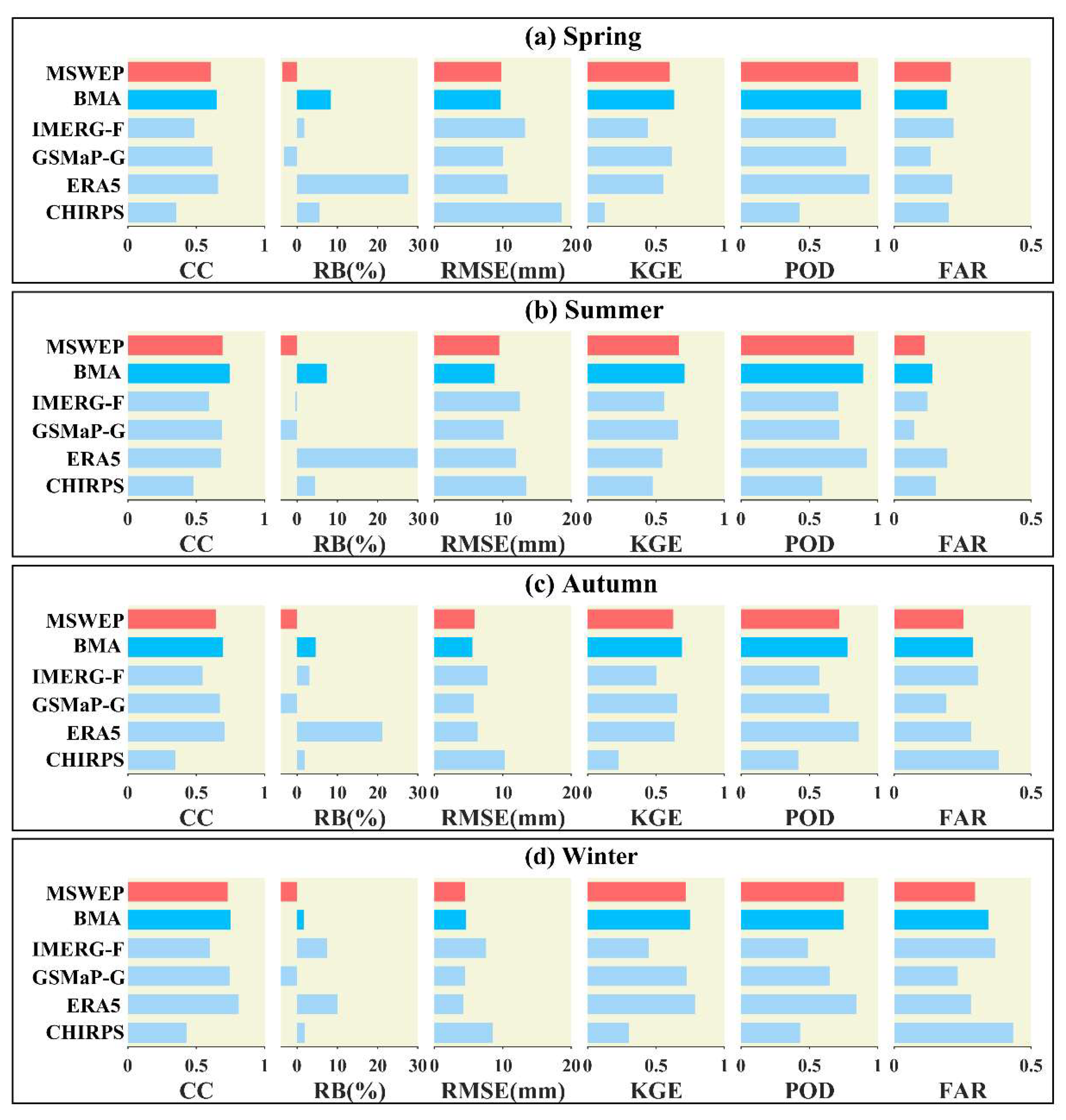

4.1.3. Seasonal Scale Evaluation

Figure 11 illustrates the seasonal evaluation metrics for six precipitation products in the study area (2008–2020). The dataset is divided into four seasons for metric calculation: spring (March–May), summer (June–August), autumn (September–November), and winter (December–February). The evaluation results highlight significant improvements and substantial advantages of BMA across different seasons. The BMA scheme effectively addresses the deficiencies of CHIRPS (poor CC, RMSE, etc.), ERA5 (larger RB), and IMERG-F (poor KGE, POD, etc.) in precipitation estimation across seasons.

Among these, CHIRPS, ERA5, and IMERG-F exhibit low accuracy, large deviations, and poor detection capabilities. CHIRPS and IMERG-F show relatively high availability in summer, while ERA5 demonstrates high availability in winter. For most metrics, BMA outperforms MSWEP and other products in spring, particularly in CC, RMSE, and KGE (

Figure 9a). During summer, ERA5’s deviation increases to 30%, while BMA and other products demonstrate better metric evaluation capabilities (

Figure 9b). In autumn, BMA’s RB and RMSE further decrease, but all products show varying degrees of deterioration in POD and FAR performance (

Figure 9c). In winter, BMA achieves the best results in CC, RB, RMSE, and KGE, demonstrating strong performance. CHIRPS performs poorly in FAR, with rainfall events near 0.5 failing to align correctly (

Figure 9d). These results indicate that BMA and other products exhibit seasonal variations and differences in precipitation estimation. Most products perform better in POD and FAR during spring and summer, and in CC, RB, RMSE, and KGE during autumn and winter.

Figure 10.

Box plots of monthly-scale evaluation metrics for six precipitation products (2008–2020).

Figure 10.

Box plots of monthly-scale evaluation metrics for six precipitation products (2008–2020).

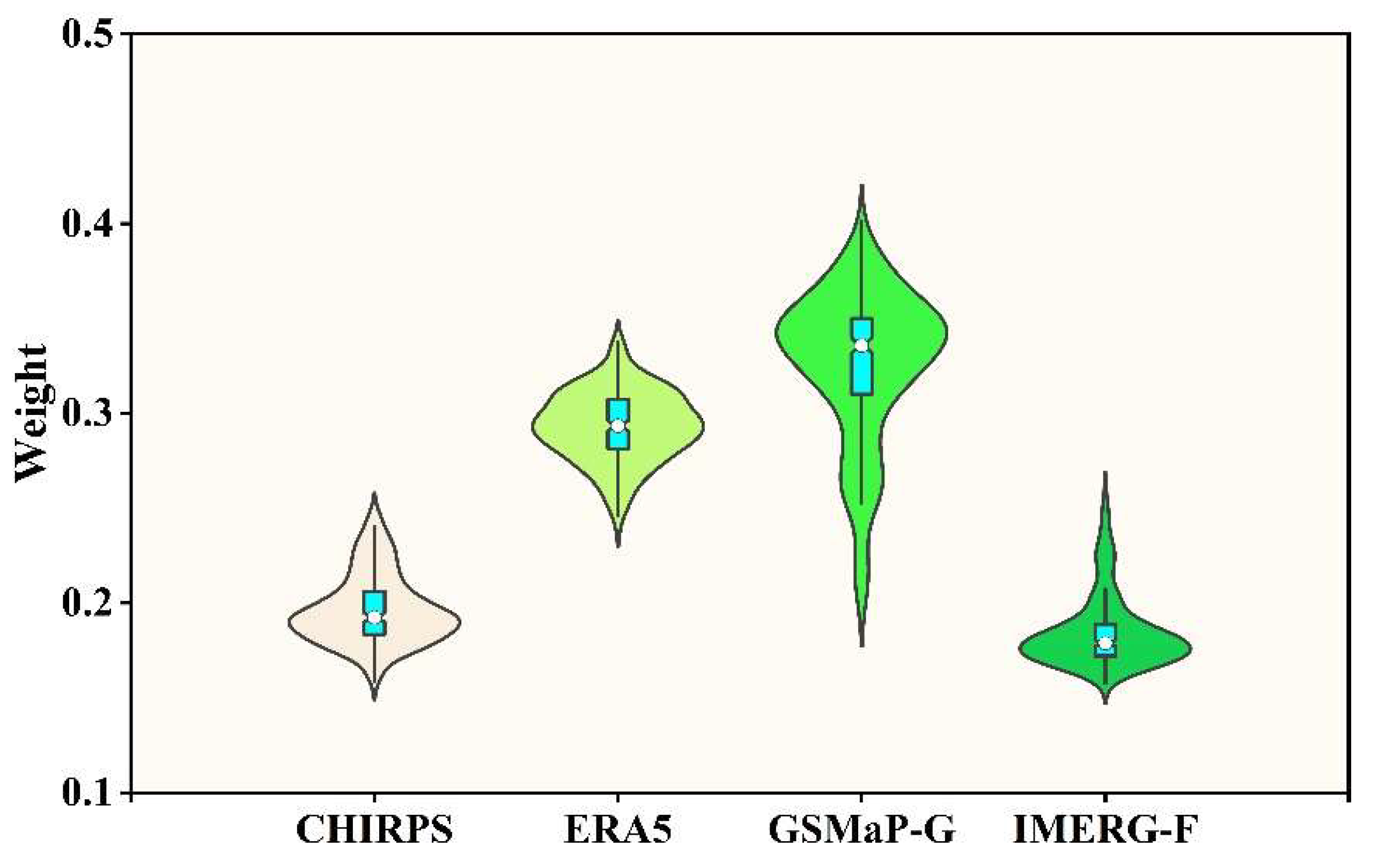

4.2. Weight Analysis of BMA Ensemble Members

In this study, optimal weights for each ensemble member across 234 grids in the Ganjiang River Basin are calculated using 2008–2020 as the training period.

Figure 12 shows the weight distribution for the four ensemble members in BMA across the Ganjiang River Basin. Higher weights are assigned to better-performing members in BMA, as the feasibility of individual products is determined by their consistency with observed precipitation [

31,

36]. GSMaP-G generally receives the highest weight, contributing the most to BMA, with a median of 0.34 and weights ranging from 0.18 to 0.42. ERA5 contributes the second highest to BMA, with weights ranging from 0.25 to 0.35. CHIRPS and IMERG-F have similar weights, with medians of 0.19 and 0.17, respectively, contributing less to BMA.

Figure 11.

Seasonal average evaluation metrics of six precipitation products (2008–2020).

Figure 11.

Seasonal average evaluation metrics of six precipitation products (2008–2020).

Figure 12.

Relative weights of the four ensemble members of BMA in the Ganjiang River Basin (2008–2020).

Figure 12.

Relative weights of the four ensemble members of BMA in the Ganjiang River Basin (2008–2020).

4.3. Hydrological Simulation Driven by Different Precipitation Products

4.3.1. Daily Scale Simulation

Figure 13 compares observed daily runoff with runoff simulations from daily precipitation data estimated by BMA, its ensemble members, and MSWEP. Gauge-based simulations yield excellent results, with NSE values of 0.86 during calibration and 0.74 during verification, demonstrating high feasibility for daily runoff prediction (

Figure 13a). CHIRPS and IMERG-F produce poor runoff simulations, with NSE values below 0.6 and simulated runoff significantly exceeding observed values (

Figure 13b,e). ERA5’s NSE is only 0.07, with simulated runoff far exceeding observed values, making the results unreliable (

Figure 13c). Both GSMaP-G and MSWEP achieve reliable runoff simulations, with NSE values of 0.79 and 0.82, respectively. GSMaP-G more accurately captures peak flows, while MSWEP’s simulated runoff trend closely matches observed trends (

Figure 13d,g). BMA’s runoff simulation also achieves favorable results, with an NSE of 0.70. The simulated and observed runoff trends are closely aligned, and the estimated precipitation trend matches the observed, making the results highly reliable. Although BMA’s runoff simulation shows slight overestimation, it remains acceptable and outperforms other products (

Figure 13f).

4.3.2. Monthly Scale Simulation

Figure 14 compares observed monthly runoff with runoff simulations from various precipitation products at the monthly scale. From daily to monthly scales, all products except ERA5 show improved simulation accuracy with higher NSEs, while ERA5’s NSE drops to -0.15, indicating unreliable results. Notably, MSWEP-driven monthly runoff simulations achieve an NSE of 0.91, closely matching observed runoff. BMA’s NSE increases to 0.71, with its monthly runoff simulation closely aligning with observed values, particularly for high-discharge flood events. This demonstrates BMA’s superior applicability for runoff simulation in the study area.

4.3.3. Analysis of Runoff Changes During Wet and Dry Periods

The wet season in the Ganjiang River (2010–2020) spans May to August, while the dry season spans November to February.

Figure 15 compares observed runoff (hereafter OBR) with average monthly runoff simulations from different products during wet and dry seasons.

Figure 15a shows observed runoff and simulated results from precipitation products during the wet season. Gauge-based simulations yield average monthly runoff closely matching OBR during the wet season, achieving ideal results. CHIRPS and IMERG-F produce poor simulation results, with a tendency to overestimate average monthly runoff. ERA5’s simulated average monthly runoff consistently exceeds OBR, rendering the results unreliable. GSMaP-G’s average monthly runoff closely matches OBR from 2010 to 2015 but significantly exceeds it from 2016 to 2020. MSWEP’s average monthly runoff simulations are reliable, closely resembling OBR. BMA also achieves ideal results in simulating wet season runoff. Although simulated runoff is slightly higher than OBR in most years, BMA demonstrates good feasibility and applicability for wet season runoff prediction.

Figure 15b shows observed runoff and simulated results from precipitation products during the dry season. From November 2015 to February 2016, average monthly runoff from OBR and other products is significantly higher than in other years, with minimal differences in other dry seasons. As runoff decreases in the dry season, deviations between simulated runoff and OBR decrease, but CHIRPS, ERA5, and IMERG-F remain significantly higher, indicating poor feasibility. GSMaP-G, MSWEP, and BMA’s average monthly simulated runoff during the dry season closely matches OBR, with credible results.

5. Discussion

5.1. Influence of Precipitation Inputs on BMA

In this study, the BMA method is employed to merge four precipitation products into a unified daily precipitation dataset. The performance of this merged product is systematically evaluated and compared in

Section 4.1. Generally, the selection of precipitation products, including their types and quantities, requires careful consideration when developing ensemble-based datasets. The accuracy of individual products significantly influences BMA data quality, as different products exhibit substantial performance variations due to diverse retrieval algorithms, terrain, and climate effects. Typically, higher-performing members are assigned greater weights in BMA [

21,

31]. Chen et al. (2015) [

37] suggested that poorly performing members in BMA would reduce the integration accuracy of merged data. This highlights the inherent influence of input precipitation datasets on BMA [

23].

The BMA-merged precipitation product significantly improves precipitation estimation, outperforming other products in daily, monthly, and seasonal accuracy evaluations. However, its runoff simulation is inferior to GSMaP-G and MSWEP on both daily and monthly scales. Among ensemble members, GSMaP-G achieves the best accuracy evaluation and the highest weight (approximately 0.34), followed by ERA5 with a weight of around 0.3. However, ERA5 significantly overestimates precipitation, and CHIRPS and IMERG-F also exhibit varying degrees of overestimation, leading to overestimated merged precipitation and biased runoff simulations. MSWEP, which integrates observations, satellites, and reanalysis, combines daily precipitation from approximately 77,000 global sites [

38], resulting in superior performance compared to other datasets in most regions. Excluding poorly performing products like CHIRPS and ERA5 and integrating gauge-based and other high-accuracy datasets could enhance the quality of merged products in future studies.

5.2. Extreme Runoff Analysis

Analysis of daily and monthly runoff in wet and dry seasons in the Ganjiang River Basin reveals notable variations in observed runoff compared to other years. Quan et al. (2009) [

39] identified a strong correlation between precipitation and discharge in the Huaihe River Basin, indicating a reliable relationship between extreme precipitation and extreme runoff. Therefore, extreme runoff is closely linked to extreme precipitation.

In mid-to-late June 2010, the Ganjiang River Basin experienced heavy rainfall due to the combined influence of cold air from the north and warm humid air from the southwest. On June 22, the Waizhou Station recorded its highest discharge. The average monthly runoff during the 2015–2016 dry season was significantly higher than in other years, driven by record precipitation in November and December 2015 due to the strongest El Niño event since May 2014, which triggered a rare winter flood. Two major floods occurred from June to July 2019, followed by a sharp decline in discharge and sustained low water levels in the second half of the year due to significant weather and climate anomalies influenced by the El Niño event. Heavy rainfall concentrated in early June to July 2019, followed by a transition to high temperatures and low rainfall, resulting in a historic drought lasting from summer to winter. In 2020, influenced by El Niño and La Niña events, a concentrated rainfall period in mid-to-early July caused a major flood in the study area.

For extreme runoff, simulation results showed significant discrepancies with observed data. Therefore, the detection capability of extreme precipitation events using BMA-merged products warrants further investigation. GSMaP-G is more accurate in simulating runoff and capturing peak flows. Future studies could select GSMaP-G and other suitable products for data merging or BMA algorithm improvements to enhance extreme runoff simulation.

5.3. Analysis of Error Propagation from Precipitation to Runoff

In this study, some precipitation products, such as ERA5, demonstrate promising performance in precipitation error evaluation but perform poorly in runoff simulation. Therefore, exploring the relationship between precipitation input errors and simulated runoff errors, as well as error propagation in hydrological models, has significant implications for data quality and model improvement [

40]. Runoff simulations may amplify or reduce precipitation errors due to the nonlinear nature of hydrological processes [

41,

42].

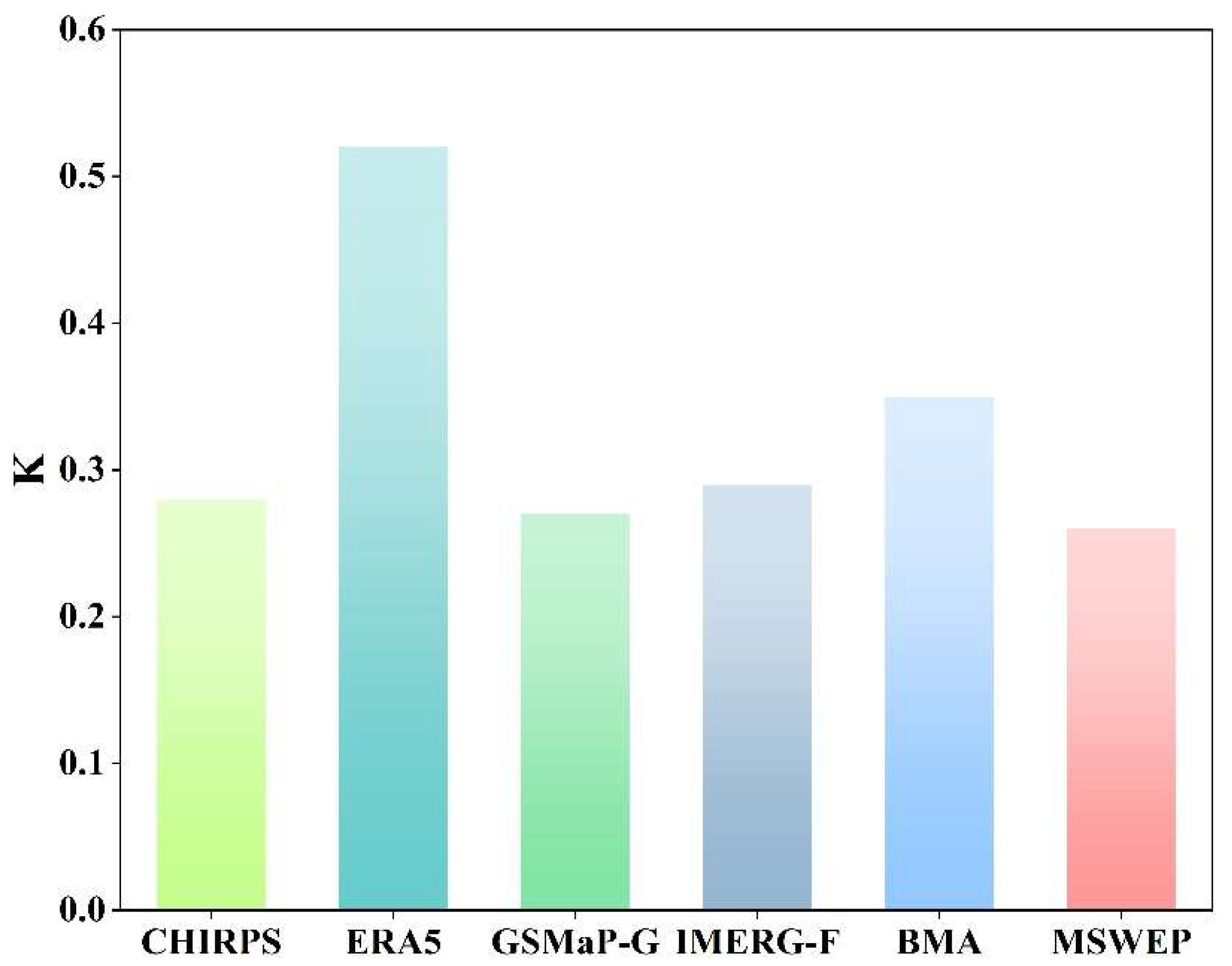

The propagation ratio K for relative root mean square error (RRMSE) quantifies the magnification (K>1) or reduction (K<1) of precipitation estimation errors during runoff simulation. As shown in

Figure 16, all selected precipitation products demonstrate strong error dampening effects in runoff simulation. ERA5’s error dampening effect is weaker than other products, suggesting that its observation technology and inversion algorithms require further improvement to enhance hydrological simulation performance in the study area. Although BMA performs best in precipitation error evaluation, its improvement in error reduction from precipitation to runoff is limited compared to other products. MSWEP and GSMaP-G show the best error dampening effects in runoff simulation, highlighting their potential for driving hydrological models in the study area. Additionally, MSWEP and GSMaP-G incorporate ground observations or data correction, suggesting that integrating observed precipitation into BMA products could more effectively reduce errors from precipitation to runoff in future studies. This section analyzes the error dampening effects of various products from precipitation to runoff, while the influence of basin size, climate zone, and season on error dampening remains to be explored.

5.4. Improvements in Future Research

This study uses a general BMA framework to weight-fuse four precipitation products and analyzes the spatial distribution of ensemble members’ relative weights in the Ganjiang River Basin. However, the temporal distribution of weights is not explored. Future research could explore adaptable BMA frameworks, such as dynamic, multi-stage, and quantile-based methods [

22,

43], to yield more reliable precipitation estimates and improved runoff simulations.

Although BMA excels in integrating precipitation products, it may be affected by spatial variations in data sources and complex geographical environments [

44]. Many studies indicate that BMA-based precipitation estimation exhibits significant uncertainties in complex terrains. Rahman et al. (2020) [

45] found that the uncertainty of the Dynamic Clustered Bayesian Model Averaging (DCBA) method was highest in glacier areas and lowest in extremely arid regions, with precision and correlation peaking at low elevations. Ma et al. (2018) [

46] found that the dynamic BMA method performed best at 1,000–3,000 m over the Tibetan Plateau, with performance deteriorating at altitudes above 4,000 m.

In this study, the mountainous areas in the southwestern Ganjiang River Basin could influence precipitation estimation [

47]. Additionally, the Ganjiang River Basin, a typical subtropical monsoon region with mild climate and abundant precipitation, is well-suited for the BMA scheme. However, the applicability of BMA in other complex climate zones, such as tropical humid and cold arid regions, remains to be investigated. Therefore, despite improved BMA performance, further research is needed to develop dynamic BMA frameworks for complex terrains and climates and incorporate new or improved data sources. Finally, the BMA scheme could be further enhanced through methods such as machine learning (ML) [

48] and neural networks (NN) [

49].

6. Conclusions

In this study, the BMA method is used to generate a merged precipitation product by fusing multi-source datasets (CHIRPS, ERA5, GSMaP-G, and IMERG-F) in the Ganjiang River Basin. BMA, its ensemble members, and MSWEP are compared and analyzed at daily, monthly, and seasonal scales. Additionally, the VIC model is employed to assess the impact of six precipitation products on simulated runoff in the basin. The main conclusions are as follows:

The performance of BMA in evaluation metrics such as CC, RMSE, and KGE on daily and monthly scales is significantly ahead of other products. The estimated precipitation demonstrates great applicability in the spatial distribution of the study area, showing good correlation and weak dispersion with observed precipitation. GSMaP-G and MSWEP exhibit better availability in the Ganjiang River Basin, while ERA5 significantly overestimates precipitation in most areas.

Seasonal evaluation reveals seasonal variations and differences in precipitation estimation between the BMA and other precipitation products. In spring and summer, the BMA performs best in terms of POD and FAR. In autumn and winter, it is significantly better than other products in RB and KGE. The BMA effectively improves deficiencies in precipitation estimation of ensemble members in different seasons.

Higher-performing ensemble members receive greater weights in BMA, with GSMaP-G achieving the highest median weight of 0.34 and contributing the most to the merged product. ERA5 follows, with weights ranging from 0.25 to 0.35. CHIRPS and IMERG-F have the lowest scores and contribute minimally to BMA.

The VIC model driven by BMA achieves ideal results in daily and monthly runoff simulations, with simulated and observed runoff trends closely aligned. The average monthly runoff in wet and dry seasons closely matches observed values. The product demonstrates strong applicability in the study area and meets the requirements for long-term runoff simulation in the Ganjiang River Basin.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.N. and Y.C.; methodology, S.N.; software, J.W. and B.R.T.; validation, Y.Z. and J.J.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.C.; writing—review and editing, S.N.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42271084, 52379006, U2240223), and Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2308085US13)

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the findings of this study are included within the article. The runoff data used in this study are confidential.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the precipitation dataset producers used in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Zhang, X.; Song, Y.; Nam, W.-H.; Huang, T.; Gu, X.; Zeng, J.; Huang, S.; Chen, N.; Yan, Z.; Niyogi, D. Data fusion of satellite imagery and downscaling for generating highly fine-scale precipitation. J. Hydrol. 2024, 631, 130665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksu, H.; Taflan, G.Y.; Yaldiz, S.G.; Akgül, M.A. Evaluation of IMERG for GPM satellite-based precipitation products for extreme precipitation indices over Turkiye. Atmos. Res. 2023, 291, 106826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, A.; Roshun, S.H.; Booij, M.J. Comparison of satellite-based and reanalysis precipitation products for hydrological modeling over a data-scarce region. Clim. Dynam. 2024, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhuo, L.; Han, D.; Liu, Y.; Rico-Ramirez, M.A. Hydrological model adaptability to rainfall inputs of varied quality. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2022WR032484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, S.; Tan, M.L.; Pan, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; He, R.; Wang, Z. Correcting the bias of daily satellite precipitation estimates in tropical regions using deep neural network. J. Hydrol. 2022, 608, 127656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Kong, X.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Pang, C. Reliability of satellite-derived precipitation data in driving hydrological simulations: A case study of the upper Huaihe River basin, China. J. Hydrol. 2022, 612, 128076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.H.; Nguyen, D.L.; Nguyen, H.H. Assessing applicability of two gridded precipitation datasets for hydrological simulation in a poorly gauged river basin towards supporting sustainable water resources management. Environ. Res. 2023, 237, 116956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, P.; Chen, M.; Yang, S.; Yatagai, A.; Hayasaka, T.; Fukushima, Y.; Liu, C. A gauge-based analysis of daily precipitation over East Asia. J. Hydrometeorol. 2007, 8, 607–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Xiong, A. Validation and comparison of a new gauge-based precipitation analysis over mainland China. Int. J. Climatol. 2016, 36, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Feng, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Deng, Z. Multi-source precipitation products assessment on drought monitoring across global major river basins. Atmos. Res. 2023, 295, 106982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ma, Z.; Yan, S.; Peng, J. Do ERA5 and ERA5-land precipitation estimates outperform satellite-based precipitation products? A comprehensive comparison between state-of-the-art model-based and satellite-based precipitation products over mainland China. J. Hydrol. 2022, 605, 127353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hsu, K.-L.; Aghakouchak, A.; Sorooshian, S. Object-based assessment of satellite precipitation products. Rem. Sens. 2016, 8, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Xu, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, S.; He, K.; Zhang, S.; Ma, W.; Xu, X. AERA5-Asia: a long-term asian precipitation dataset (0. 1°, 1-hourly, 1951–2015, Asia) anchoring the ERA5-land under the total volume control by APHRODITE. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2022, 103, E1146–E1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Clark, M.P.; Knoben, W.J.; Liu, H.; Gharari, S.; Arnal, L.; Beck, H.E.; Wood, A.W.; Newman, A.J.; Papalexiou, S.M. The impact of meteorological forcing uncertainty on hydrological modeling: A global analysis of cryosphere basins. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2022WR033767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Luo, Y.-T.; Ma, S.-G.; Kang, Y.; Li, Y.-Q.; Chen, H.; Xu, C.-Y. Uncertainty estimation of hydrological modelling using gridded precipitation as model inputs in the Gandaki River Basin. J. Hydrol. -Reg. Stud. 2024, 53, 101825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, A.; Tran, T.-N.-D.; Kumar, B.; Lakshmi, V. Evaluation of Satellite-Derived Precipitation Products for Streamflow Simulation of a Mountainous Himalayan Watershed: A Study of Myagdi Khola in Kali Gandaki Basin, Nepal. Rem. Sens. 2023, 15, 4762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Tang, G.; Jing, W.; Hou, Z.; Yang, J.; Sun, J. Evaluation of Multiple Satellite, Reanalysis, and Merged Precipitation Products for Hydrological Modeling in the Data-Scarce Tributaries of the Pearl River Basin, China. Rem. Sens. 2023, 15, 5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Wood, E.F.; Pan, M.; Fisher, C.K.; Miralles, D.G.; Van Dijk, A.I.; Mcvicar, T.R.; Adler, R.F. MSWEP V2 global 3-hourly 0. 1 precipitation: methodology and quantitative assessment. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2019, 100, 473–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massoud, E.; Lee, H.; Gibson, P.; Loikith, P.; Waliser, D. Bayesian model averaging of climate model projections constrained by precipitation observations over the contiguous United States. J. Hydrometeorol. 2020, 21, 2401–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, S.; Bhat, M.S.; Alam, A.; Farooq, H.; Shiekh, H.A. Complementary use of multi-model climate ensemble and Bayesian model averaging for projecting river hydrology in the Himalaya. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 38898–38920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Hong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Tang, G.; Yao, Y.; Long, D.; Li, C.; Han, Z.; Liu, R. Performance of optimally merged multisatellite precipitation products using the dynamic Bayesian model averaging scheme over the Tibetan Plateau. J GEOPHYS RES-ATMOS 2018, 123, 814–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumnam, K.; Guntu, R.K.; Rathinasamy, M.; Agarwal, A. Quantile-based Bayesian Model Averaging approach towards merging of precipitation products. J. Hydrol. 2022, 604, 127206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Jiang, S.; Dong, J.; Ren, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, M.; Duan, Z. Fusion of gauge-based, reanalysis, and satellite precipitation products using Bayesian model averaging approach: Determination of the influence of different input sources. J. Hydrol. 2023, 618, 129234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Guo, J.; Leung, L.R. Assessment of the effects of spatial resolutions on daily water flux simulations. J. Hydrol. 2004, 298, 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Yong, B.; Gourley, J.J.; Qi, W. Real-time bias adjustment for satellite-based precipitation estimates over Mainland China. J. Hydrol. 2021, 596, 126133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.; Iqbal, M.F.; Mahmood, I. Validation of CHIRPS satellite-based precipitation dataset over Pakistan. Atmos. Res. 2021, 248, 105289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorolog. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Guo, B.; Xing, W.; Zhou, J.; Xu, F.; Xu, Y. Comprehensive evaluation of latest GPM era IMERG and GSMaP precipitation products over mainland China. Atmos. Res. 2020, 246, 105132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retalis, A.; Katsanos, D.; Tymvios, F.; Michaelides, S. Comparison of GPM IMERG and TRMM 3B43 Products over Cyprus. Rem. Sens. 2020, 12, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, H.; Song, W.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, K.; Chen, L.; Feng, T.; Linghu, S.; Alam, M. Validation of CRU TS v4. 08, ERA5-Land, IMERG v07B, and MSWEP v2. 8 Precipitation Estimates Against Observed Values over Pakistan. Rem. Sens. 2024, 16, 4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Ajami, N.K.; Gao, X.; Sorooshian, S. Multi-model ensemble hydrologic prediction using Bayesian model averaging. Adv. Water Resour. 2007, 30, 1371–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Ren, L.; Hong, Y.; Yong, B.; Yang, X.; Yuan, F.; Ma, M. Comprehensive evaluation of multi-satellite precipitation products with a dense rain gauge network and optimally merging their simulated hydrological flows using the Bayesian model averaging method. J. Hydrol. 2012, 452, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raftery, A.E.; Gneiting, T.; Balabdaoui, F.; Polakowski, M. Using Bayesian model averaging to calibrate forecast ensembles. Mon. Weather. Rev. 2005, 133, 1155–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhong, R.; Lai, C.; Chen, J. Evaluation of the GPM IMERG satellite-based precipitation products and the hydrological utility. Atmos. Res. 2017, 196, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaowei, N.; Jie, W.; Juliang, J.; Xiaoyan, X.; Yuliang, Z.; Fan, S.; Linlin, Z. Comprehensive evaluation of satellite-derived precipitation products considering spatial distribution difference of daily precipitation over eastern China. J. Hydrol. -Reg. Stud. 2022, 44, 101242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloughter, J.M.L.; Raftery, A.E.; Gneiting, T.; Fraley, C. Probabilistic quantitative precipitation forecasting using Bayesian model averaging. Mon. Weather. Rev. 2007, 135, 3209–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yuan, W.; Xia, J.; Fisher, J.B.; Dong, W.; Zhang, X.; Liang, S.; Ye, A.; Cai, W.; Feng, J. Using Bayesian model averaging to estimate terrestrial evapotranspiration in China. J. Hydrol. 2015, 528, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Li, Q.; Chen, X.; De Maeyer, P.; Yan, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Li, L. Spatiotemporal variability of the precipitation concentration and diversity in Central Asia. Atmos. Res. 2020, 241, 104954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, D.; Xing, C.; Tiexi, C.; Xing-Wu, C. Relationship between extremes of precipitation and discharge in the Huaihe River Basin. J. Nanjing Univ. (Natural Sci). 2009, 45, 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, C.M.; Pham, H.T.; Marshall, L.A.; Johnson, F.M. Which Rainfall Errors Can Hydrologic Models Handle? Implications for Using Satellite-Derived Products in Sparsely Gauged Catchments. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2020WR029331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanding, N.; Wu, H.; Tao, J.; Maggioni, V.; Beck, H.E.; Zhou, N.; Huang, M.; Huang, Z. Assessment of precipitation error propagation in discharge simulations over the contiguous United States. J. Hydrometeorol. 2021, 22, 1987–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, J.; Miao, C.; Sorooshian, S.; Duan, Q.; Guo, X.; Su, T. Satellite-based precipitation error propagation in the hydrological modeling chain across China. J. Hydrol. 2024, 130906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Guo, S.; Gu, L.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, D.; Chen, J.; Shen, Y.; Xu, C.-Y. Blending multi-satellite, atmospheric reanalysis and gauge precipitation products to facilitate hydrological modelling. J. Hydrol. 2021, 593, 125878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, D. A multiple-step scheme for the improvement of satellite precipitation products over the Tibetan Plateau from multisource information. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 873, 162378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, K.U.; Shang, S.; Shahid, M.; Wen, Y.; Khan, Z. Application of a dynamic clustered bayesian model averaging (DCBA) algorithm for merging multisatellite precipitation products over Pakistan. J. Hydrometeorol. 2020, 21, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yang, Y.; Han, Z.; Tang, G.; Maguire, L.; Chu, Z.; Hong, Y. Comprehensive evaluation of ensemble multi-satellite precipitation dataset using the dynamic bayesian model averaging scheme over the Tibetan Plateau. J. Hydrol. 2018, 556, 634–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, S. Evaluating the TRMM multisatellite precipitation analysis for extreme precipitation and streamflow in Ganjiang River basin, China. Adv. Meteorol. 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, K.; Dong, N.; Wang, H. Optimally integrating multi-source products for improving long series precipitation precision by using machine learning methods. J. Hydrol. 2022, 609, 127707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.Y.; Lee, S.-I. Fusion of Multi-Satellite Data and Artificial Neural Network for Predicting Total Discharge. Rem. Sens. 2020, 12, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).