1. Introduction

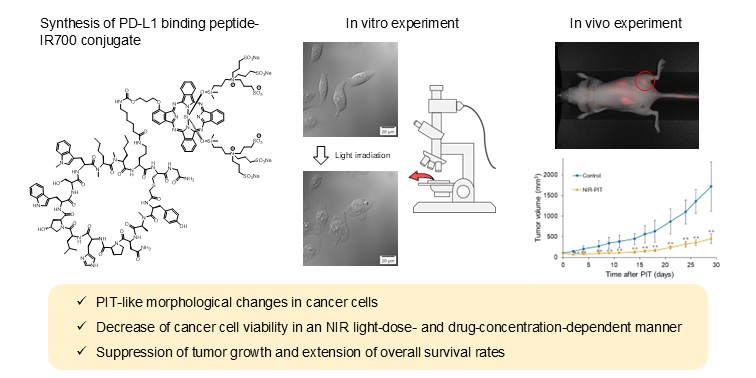

Near-infrared photoimmunotherapy (NIR-PIT) is a new targeted treatment for cancer [

1,

2,

3,

4]. It combines target-directed molecules that bind to cancer cells with the photoabsorber IRDye700DX (IR700) and selectively kills the target cells by irradiation with NIR light. NIR-PIT involves the administration of a PIT drug, binding the drug to its target on cancer cells, and subsequent irradiation with NIR light. The target-directed molecules used in NIR-PIT are primarily monoclonal antibodies that selectively bind to specific antigens expressed on the surface of cancer cells. Irradiation with NIR light at approximately 690 nm from the outside of the body induces a structural change in IR700, which imposes stress on membrane proteins and causes cell membrane damage. Consequently, target cells immediately swell, rupture, and undergo necrosis-like cell death [

5,

6]. Owing to this mechanism, NIR-PIT exhibits high specificity, immediate therapeutic efficacy, and low invasiveness because it relies solely on light, and light can be reapplied according to the therapeutic response. Moreover, the cetuximab-IR700 conjugate targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) was approved in Japan in 2020 and has shown promising clinical results [

7,

8,

9]. However, this is the only antibody-based drug currently in clinical use, with the development of new antibody-based drugs for novel targets being costly and time-consuming.

Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) is an important molecule involved in immune suppression; it has attracted attention as a target for cancer immunotherapy. As an immune checkpoint molecule, PD-L1 is a cell membrane protein belonging to the B7 family and is mainly expressed in cancer and antigen-presenting cells [

10,

11,

12]. It inhibits T cell activation by binding to PD-1 receptors on the surface of T cells. It inhibits T cell proliferation, cytokine production, and cytotoxic activity, thereby suppressing autoimmune responses and enabling cancer cells to evade the immune system. PD-L1 is overexpressed in many types of cancer, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), gastric cancer, and breast cancer [

13,

14]. Multiple immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis have been approved as cancer treatments [

14,

15,

16]. Additionally, NIR-PIT with anti-PD-L1 antibodies has demonstrated sufficient therapeutic effects in mouse xenograft models [

17,

18]. Therefore, the clinical application of NIR-PIT for targeting PD-L1 is highly desirable. However, antibody-based drugs are costly and their development is challenging. In contrast, peptides can be chemically synthesized at low production costs [

19]. Additionally, because of their small size, they exhibit high permeability within tumors, enable more uniform and deeper penetration than antibodies, and have the potential to enhance the therapeutic effects of NIR-PIT [

20]; their efficacy in photoimmunotherapy has been reported [

21].

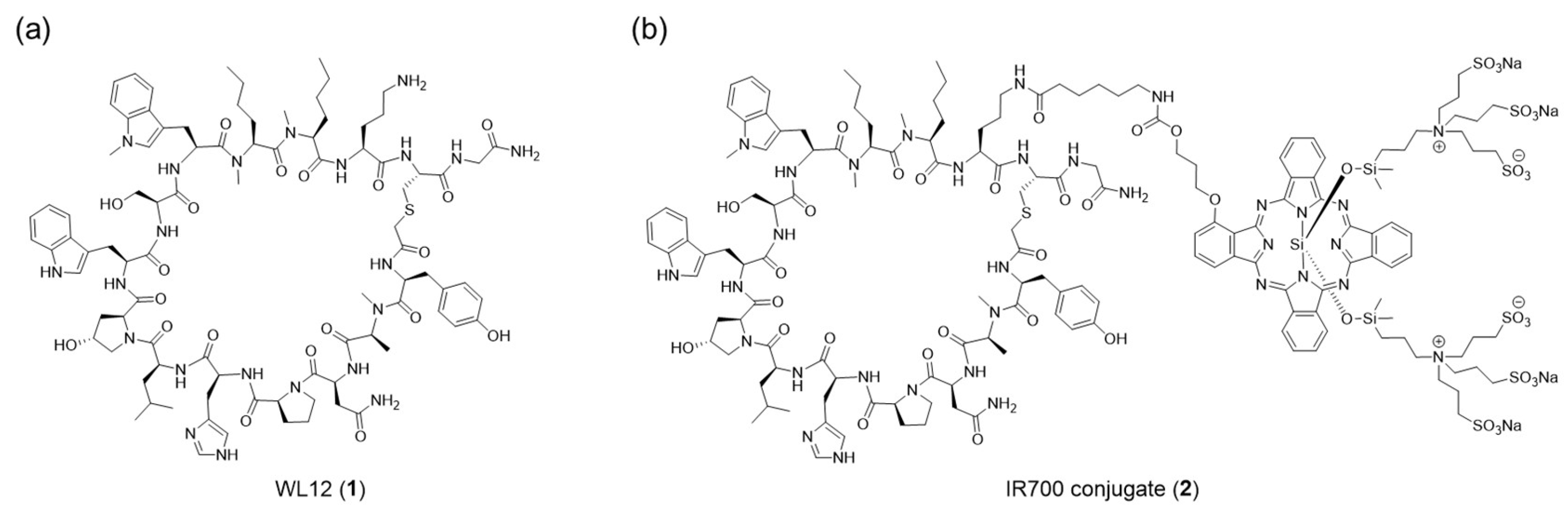

WL12 is a synthetic cyclic peptide with high affinity for PD-L1 (

Figure 1a) [

22]. It has a molecular mass of approximately 2 kDa and has recently been investigated as a positron emission tomography (PET) imaging probe following labeling with

64Cu or

68Ga [

22,

23,

24]. They have been reported to have high accumulation in cancer cells and favorable pharmacokinetics. Furthermore, ⁶⁸Ga-NOTA-WL12 has been used in a first-in-human study in patients with NSCLC, enabling clear and safe visualization of cancers [

25]. As WL12 is a cyclic peptide containing

N-methylation, it is expected to have high metabolic stability, affinity, and selectivity for its targets as previously reported [

26,

27,

28]. These properties mitigate typical peptide liabilities such as rapid degradation and lower affinity and selectivity than antibodies. Thus, WL12 is a promising target-directed molecule for NIR-PIT. In the present study, we developed a novel PIT drug using WL12 as a PD-L1 targeting scaffold (

Figure 1b). We synthesized a WL12-IR700 conjugate and evaluated its performance as an NIR-PIT drug in vitro and in vivo.

2. Results

2.1. Synthesis of the WL12-IR700 conjugate

Synthesis of the WL12-IR700 conjugate (2) is shown in

Scheme 1. WL12 (1) was obtained via 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc) solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) using a microwave peptide synthesizer, chloroacetylation at the N-terminus, deprotection, cleavage from the resin, and an intramolecular cyclization reaction. The amino group of the ornithine residue in 1 was then reacted with IR700 N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (IR700 NHS ester) to obtain WL12-IR700. WL12 possesses only one amine group that can react with NHS ester. Analysis confirmed that the expected 1:1 conjugated compound of WL12 and IR700 was obtained (

Figure S1).

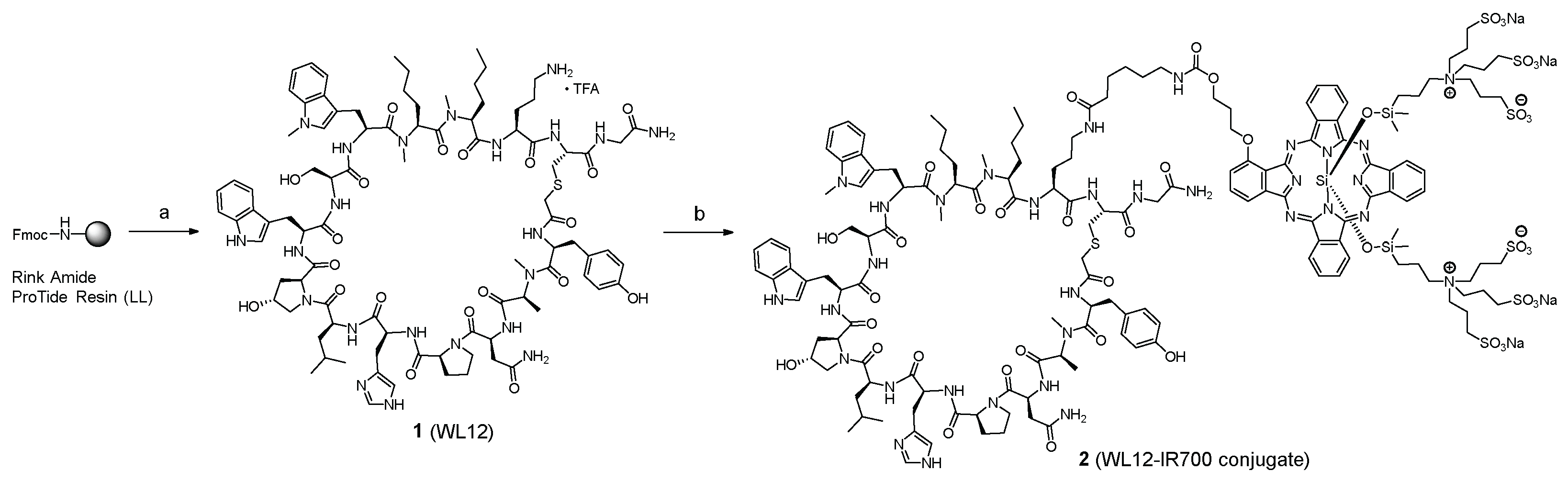

2.2. Binding to cancer cells

To evaluate the binding of WL12-IR700 to PD-L1 on cancer cell membranes, the fluorescence of WL12-IR700 bound to the cells was measured using a flow cytometer (

Figure 2). WL12-IR700 bound to MDA-MB-231 cells, which highly express PD-L1 [

29].

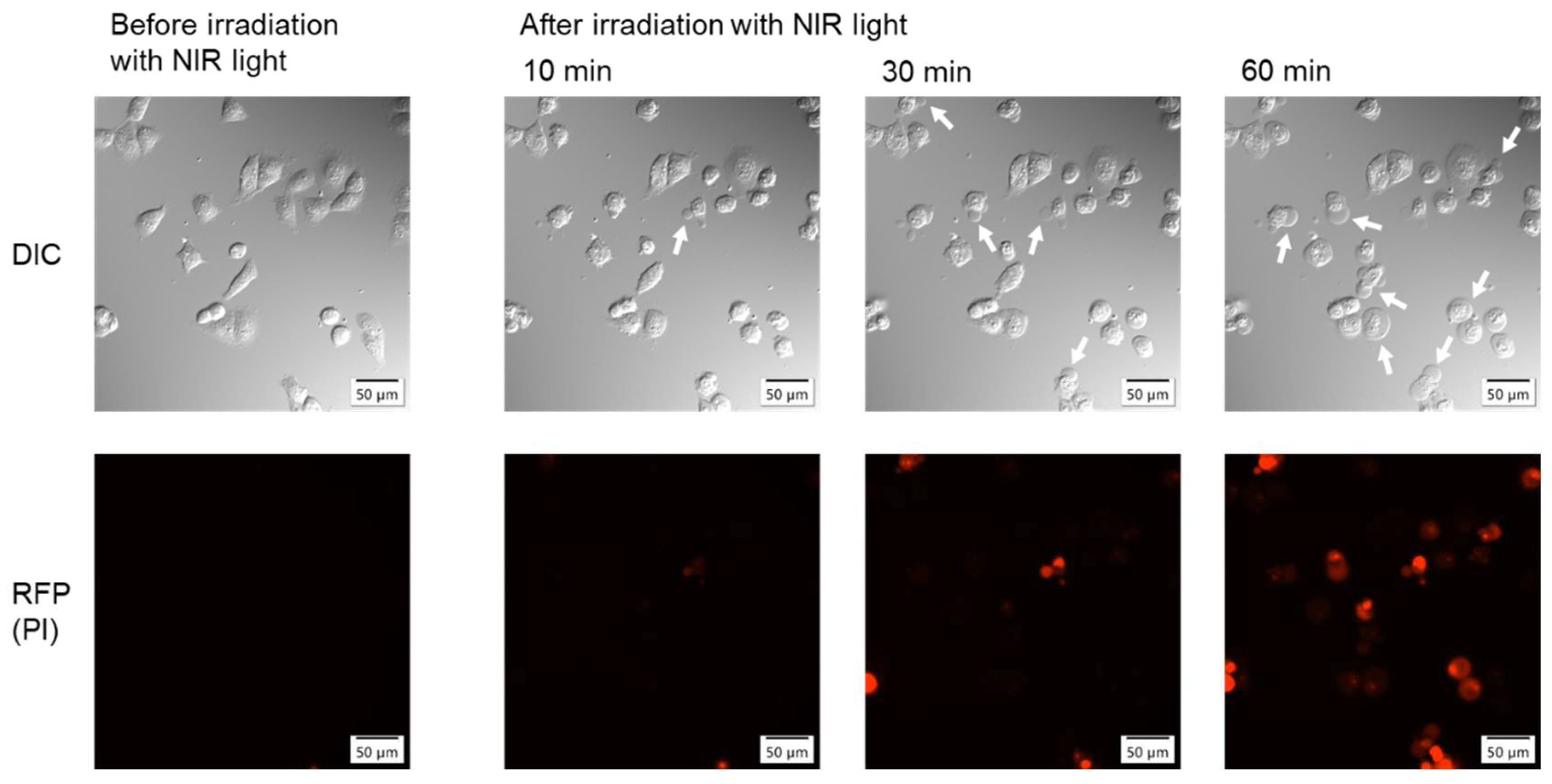

2.3. Microscopic observation

Morphological changes in cells before and after NIR light irradiation were observed using a fluorescence microscope (

Figure 3). The upper panels show differential interference contrast (DIC) images. Morphological changes, such as bleb formation and swelling, were observed in some cells 10 min after irradiation and in most cells 60 min after irradiation. Bleb formation and swelling are characteristic morphological changes observed in NIR-PIT with antibody-based drugs [

1,

2]. In the lower panels, the fluorescence of propidium iodide (PI), which intercalates into nuclear DNA, was observed in the cells, indicating cell membrane destruction. The number of cells positive for red fluorescence also increased over time after irradiation, similar to the morphological changes.

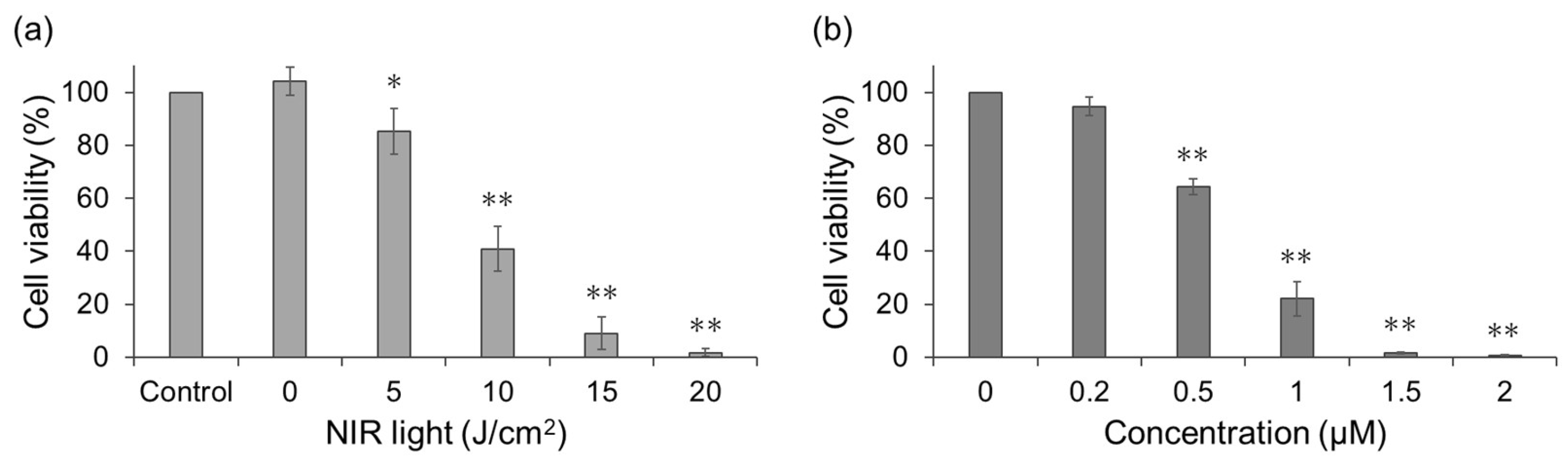

2.4. Cell viability assays

To quantify cytotoxicity, cell viability was assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (

Figure 4). First, the NIR light dose-dependent cell viability following treatment with WL12-IR700 was examined (

Figure 4a). Cell viability decreased significantly compared with that of the non-irradiated control, and this decrease was dependent on the dose of NIR light. Next, drug concentration-dependent cell viability was examined (

Figure 4b). Irradiation experiments were performed at various drug concentrations (0.2–2 µM), and cell viability decreased in a drug-concentration-dependent manner.

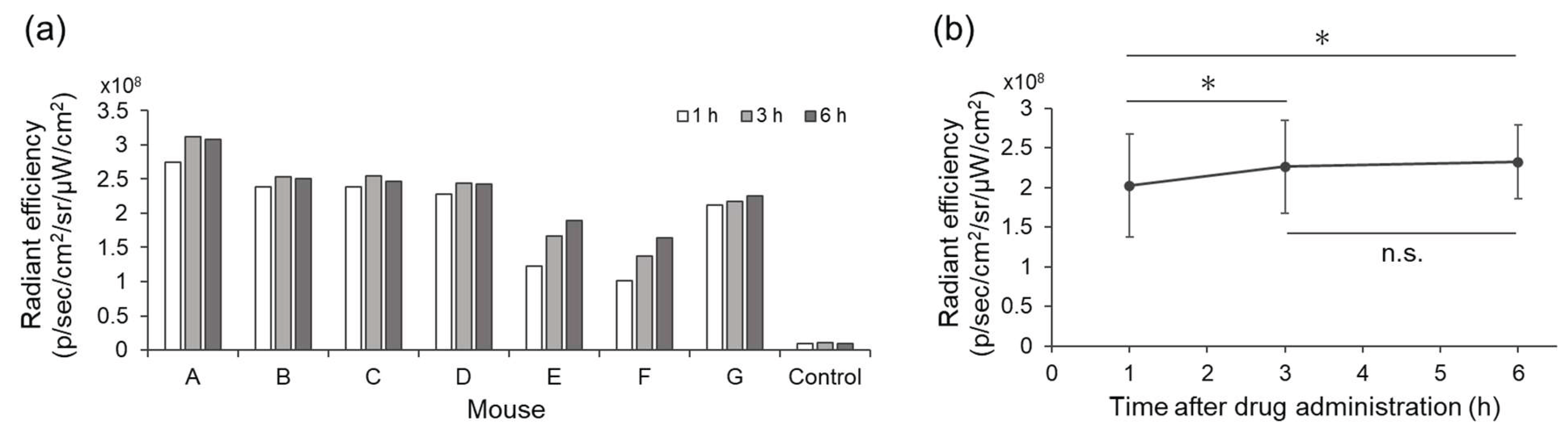

2.5. In vivo accumulation study

To evaluate the usefulness of WL12-IR700 in vivo, mice bearing MDA-MB-231 tumors were established. IR700 fluorescence in the tumor was quantified using IVIS after the intravenous injection of WL12-IR700 (

Figure 5 and

Figure S2). Radiant efficiency in the tumor at 3 and 6 h post-injection showed significantly higher fluorescence intensity than that at 1 h (

Figure 5b). Based on these results, NIR light irradiation was performed 3 h after WL12-IR700 injection in the subsequent in vivo therapeutic study.

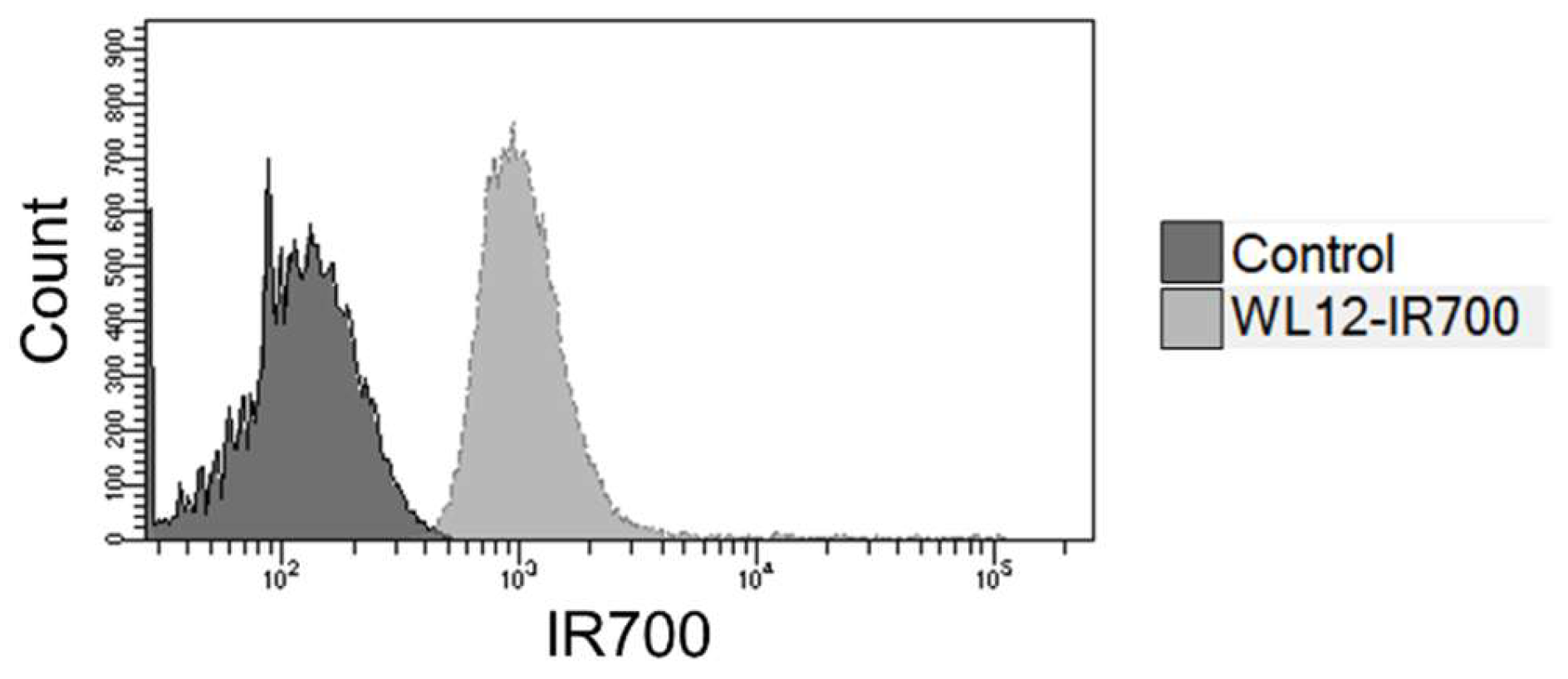

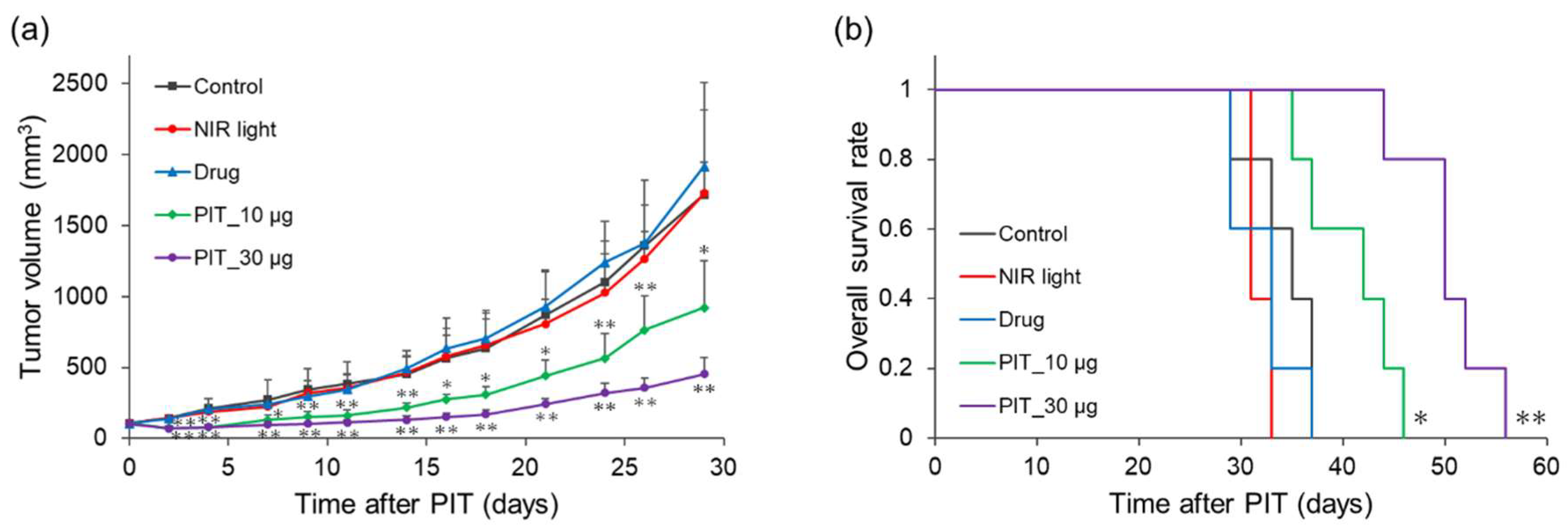

2.6. In vivo therapeutic experiment

Therapeutic effects were evaluated in mice bearing MDA-MB-231 tumors (

Figure 6). The tumor volumes in the NIR light and drug groups increased similarly to those in the control group. In contrast, the two PIT groups significantly suppressed the increase in tumor volume compared to that in the control group from early time points after treatment initiation (

Figure 6a). Overall survival was not prolonged in the NIR light and drug groups, whereas both PIT groups showed significant survival extension (

Figure 6b). The median survival times in control, NIR light, drug, PIT_10 µg, and PIT_30 µg groups were 35, 31, 33, 42, and 50 days, respectively.

3. Discussion

This study demonstrated that a PD-L1 targeting peptide-based NIR-PIT drug, the WL12 peptide with site-selective conjugation of IR700, can induce canonical phototherapeutic cytotoxicity in vitro and therapeutic benefit in vivo. The WL12 peptide employed in this study has been extensively characterized in previous nuclear medicine studies, with its high affinity and selectivity for PD-L1 established [

22,

23]. Docking studies further indicated that the amino group of the ornithine residue on WL12, which is used for chelator attachment in radiolabeling, points away from the PD-L1 binding interface [

22,

23]. Similarly, IR700 was introduced into the ornithine residue. Although the conjugate of bulky IR700 might reduce WL12 affinity for its target, it demonstrated sufficient binding to target-positive cells (

Figure 2). In contrast to antibodies in which IR700 is randomly introduced at multiple lysine residues, the WL12 scaffold permits site-selective attachment of IR700 at the distal amine, which is expected to preserve binding while conferring light-activatable cytotoxicity.

The morphological changes in cells characteristic of NIR-PIT are bleb formation and cell swelling [

1,

2,

3]. These changes arise from IR700 structural changes on the cell surface upon NIR irradiation, in turn causing membrane damage [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Consistent with this mechanism, WL12-IR700 elicited rapid bleb formation and cell swelling after irradiation. Membrane permeabilization was corroborated by PI uptake. Similarly, cell death based on this mechanism has been observed using a peptide-based drug targeting EGFR [

21], suggesting that peptides have significant potential as scaffolds for NIR-PIT. Although no evidence currently exists, considering the size of the peptide-based drug, it is speculated that this significant membrane damage may be due to aggregation involving not only the drug, but also the target membrane protein.

The cytotoxicity of NIR-PIT scales with the surface density of IR700 on the membrane and the delivered light dose; light dose-response behavior has been replicated across multiple antigens and conjugate classes [

1,

2,

17,

18]. We previously revealed the light dose-dependence of a peptide-based PIT drug targeting EGFR [

21]. Likewise, this study showed NIR light dose- and drug concentration-dependent cell death in NIR-PIT with WL12-IR700 (

Figure 4). These findings support the notion that WL12-IR700 operates via a canonical NIR-PIT mechanism.

To determine the optimal timing of NIR light irradiation in therapeutic experiments, in vivo imaging was performed using IVIS. A strong IR700 signal was detected in the tumors and kidneys (

Figure 5 and

Figure S2), a distribution pattern consistent with low-molecular weight ligands that undergo rapid renal clearance [

30,

31]. In NIR-PIT, only the areas irradiated with light showed cell damage, suggesting that accumulation in the kidneys is not a major problem. To this end, tumor accumulation level was the most important factor, and the results showed a significantly higher accumulation at the tumor site at 3 and 6 h compared to 1 h post-administration, whereas no significant difference was observed between 3 and 6 h. In addition, given that NIR-PIT exerts its therapeutic effect when the drug is present on the cell membrane surface [

32] and considering that PD-L1-bound peptides undergo internalization over time, we determined that 3 h post-administration was the optimal time for NIR light irradiation.

Dose selection for in vivo experiments was based on the IR700-equivalent conversion of a clinically established antibody-based drug [

2]. The reference antibody-based drug is dosed at 100 µg with three IR700 dyes per antibody. When normalized by IR700 equivalents, the WL12-IR700 developed herein corresponds to approximately 10 µg. Therapeutic experiments were performed using 10 µg and escalated doses of 30 µg (

Figure 6). Both PIT groups showed significantly suppressed tumor volume increases compared to the control group from the early time points after NIR-PIT. Thus, peptide-based NIR-PIT is likely to have a similar effect to that utilizing antibodies. A certain degree of difference in the therapeutic effect was observed between the different doses. A superior therapeutic effect was observed with dose escalation, which was consistent with the in vitro results. Further optimization of the drug quantity and irradiation timing could enhance the fraction of IR700 residing on the cell membrane during treatment, thereby improving therapeutic outcomes. Peptide-based drugs are less expensive than their antibody-based counterparts, making it possible to increase their dosage. In addition, a PET study of WL12 in ongoing clinical trials is likely to be useful with this optimization [

25].

From a translational perspective, peptide-based NIR-PIT offers several distinct practical advantages over antibody-based drugs, including synthetic accessibility, reduced production costs, batch-to-batch homogeneity through site-selective labeling, rapid tumor accumulation kinetics, better tumor penetration, and accelerated systemic clearance that may mitigate photosensitivity risks while facilitating flexible dosing schedules or repeated administrations [

19,

33,

34,

35]. Collectively, these results position WL12-IR700 as a promising PD-L1-targeted PIT candidate and motivate systematic studies to optimize its pharmacokinetics, membrane residency at irradiation, and treatment parameters to fully leverage peptide-driven NIR-PIT in clinical practice.

This study has some limitations. First, only one cell line was used during these investigations. However, since the cytotoxic mechanism of NIR-PIT involves membrane damage after NIR light irradiation, the therapeutic effects of NIR-PIT are thought to occur independently of cell type. The therapeutic effects on other cell lines have been demonstrated with NIR-PIT using antibody-based drugs targeting PD-L1, and therapeutic effects on various cell lines have been revealed with NIR-PIT targeting other molecules [

1,

2,

17]. Second, nude mice lacking T cells were used. Because PD-L1 binds to PD-1 on T cells, the presence or absence of T cells may have affected the results. However, NIR-PIT with antibody-based drugs targeting PD-L1 has demonstrated sufficient therapeutic effects, even in an immunocompetent syngeneic model [

18]; therefore, WL12-IR700 would demonstrate therapeutic efficacy even in the presence of T cells.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Synthesis and characterization of the WL12-IR700 conjugate

4.1.1. General

Amino acid derivatives were purchased from Watanabe Chemical Inc., Ltd. (Hiroshima, Japan). IR700 NHS ester was purchased from EOS MedChem (Jinan City, China). Other reagents were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation (Osaka, Japan), Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), and CEM Corporation (Matthews, NC, USA) and were used without further purification. Preparative high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed using a COSMOSIL 5C18-ARII column (20 ID × 250 mm, Nacalai Tesque, Inc.; Kyoto, Japan) with a linear gradient of MeCN in 0.1% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) or MeCN in 0.1 M aqueous triethylammonium acetate (TEAA) at a flow rate of 9.0 mL/min on an LC-20AR system (OD, 220 or 680 nm, Shimadzu Corporation; Kyoto, Japan). For analytical HPLC, a COSMOSIL 5C18-ARII column (4.6 ID × 150 mm, Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) was employed with a linear gradient of MeCN in 0.1% aqueous TFA or MeCN in 0.1 M aqueous TEAA at a flow rate of 0.9 mL/min on an LC-20AD system (OD, 220 or 680 nm, Shimadzu Corporation). Electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectra (MS) were recorded using an LCMS-8050 instrument (Shimadzu Corporation).

4.1.2. Fmoc SPPS

Fmoc SPPS was performed using a CEM Liberty Blue automated microwave peptide synthesizer. The amino acids were coupled in 5-fold excess using 0.25 M solution of N, N'-diisopropylcarbodiimide in N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and 0.25 M solution of Oxyma Pure in DMF. Single coupling was performed for 2 min at 90 °C, and double coupling was performed twice using a single coupling protocol. Fmoc deprotections were performed for 1 min at 90 °C using a 20% (v/v) solution of piperidine in DMF. Between all the steps, the resin was washed four times with DMF.

4.1.3. Synthesis of peptide 1 (WL12)

The peptidyl resin was synthesized with Rink Amide ProTide Resin (LL) (0.025 mmol scale) by Fmoc SPPS using a microwave peptide synthesizer. All reactions after the second methylnorleucine reaction were performed by double coupling. After deprotection of the Fmoc group of the N-terminal tyrosine, the peptidyl resin was added to a 0.5 M solution of N-(chloroacetoxy)succinimide in DMF (1.0 mL) and stirred for 40 min at 20–25 °C. The resin was washed with DMF, MeOH, CHCl3, and Et2O. To cleave the resin and deprotect, the peptidyl resin was treated with TFA/1,2-ethanedithiol (EDT)/triisopropylsilane (TIS)/H2O [2.0 mL, 92.5:2.5:2.5:2.5 (v/v/v/v)] for 2 h at 20–25 °C. After filtering and concentrating under reduced pressure, the residue was poured into ice-cold Et2O. The resulting powder was collected by centrifugation and washed three times with ice-cold Et2O. The crude product was dissolved in 50% MeCN/H2O (10 mL), triethylamine (TEA; 100 µL) was added, and the mixture was stirred for 2 h at 40 °C. After concentrating MeCN under reduced pressure, the residue was lyophilized. The crude product was purified using preparative reverse phase (RP)-HPLC to obtain peptide 1 (9.02 mg, 18 % from the resin) as a freeze-dried white powder. The ESI-MS m/z calculated for C91H128N22O20S: 1880.9 (TFA desalted) recorded a peak at [M+2H]2+ m/z: 941.9.

4.1.4. Synthesis of conjugate 2 (WL12-IR700)

Peptide 1 (1.80 mg, 0.901 µmol) and N, N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA; 0.078 µL, 0.450 µmol) were added to a solution of IR700 NHS ester (0.88 mg, 0.450 µmol) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; 100 µL) and stirred for 19 h at 40 °C. The mixture was diluted with 40% MeCN/H2O. The crude product was purified by preparative RP-HPLC and passed through an ion exchange resin (Amberlite IR120B Na, ORGANO CORPORATION; Tokyo, Japan) to obtain conjugate 2 (1.12 mg, 67%, using IR700 NHS ester as the starting material) as a freeze-dried blue powder. The ESI-MS m/z calculated for C161H219N33O44S7Si34–: 3626.3 (Na+ desalted) recorded a peak at [M]4– m/z: 907.3 and [M+H]3– m/z: 1209.9.

4.2. Cell Culture

MDA-MB-231 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biowest; Nuaillé, France) and 2% (v/v) penicillin-streptomycin solution (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) and incubated at 37 °C with 95% air and 5% CO2.

4.3. Flow cytometry

Approximately 1 × 106 MDA-MB-231 cells were suspended in PBS (control, 1 mL) or a 5 µM solution of WL12-IR700 in PBS (1 mL). After incubation for 10 min at 4 °C, the samples were centrifuged, the supernatant was removed, and 1 mL of PBS was added. The samples were filtered through a 35 µm strainer cap (MTC Bio; Sayreville, NJ, USA) and then analyzed using a BD FACSymphony A1 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences; Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

4.4. Microscopic observation

Approximately 2 × 105 MDA-MB-231 cells in DMEM were seeded in a glass-bottom dish and incubated overnight at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After removal of the medium and washing with Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation), the cells were incubated with a 5 µM solution of WL12-IR700 in RPMI medium (1 mL) for 10 min at 37 °C. The solution was then replaced with RPMI medium, and 1 mg/mL solution of PI (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) was added. The cells were then irradiated with NIR light (20 J/cm2) through a 690 nm excitation filter (Semrock; Rochester, NY, USA) attached to an IX83 microscope (Olympus; Tokyo, Japan) to observe morphological changes.

4.5. Cell viability assays

Approximately 2 × 104 MDA-MB-231 cells in DMEM were seeded in 24-well plates and incubated overnight at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After removal of the medium and washing with RPMI medium, the cells were incubated with a solution of WL12-IR700 in RPMI medium (500 µL) for 10 min at 37 °C. The cells were then irradiated with NIR light using an M10-QD303 2CH regulated DC power supply (MCP Lab Electronics; Gdańsk, Poland), an AD-8724D DC power supply (A&D, Tokyo, Japan), and an LED package (Ushio Inc.; Tokyo, Japan). After removal of the solution and washing with PBS, the cells were incubated with DMEM for 24 h at 37 °C. The medium was then removed and the cells were washed with RPMI medium. CCK-8 solution (DOJINDO LABORATORIES, Kumamoto, Japan) in RPMI medium was added to each well and the cells were incubated. After incubation for 3 h at 37 °C, 100 µL of the solution was transferred to a 96-well plate. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a GloMax Discover microplate reader (Promega Corporation; Madison, WI, USA). The experiment was independently performed in triplicate.

4.6. Animal and tumor xenograft model

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee of Kansai Medical University and performed in accordance with the Rules and Regulations for Animal Experimentation stated by Kansai Medical University. Five-week-old female BALB/c nude mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory Japan, Inc. (Kanagawa, Japan) and acclimatized for 10 days. Approximately 3 × 10

6 MDA-MB-231 cells were suspended in 50 µL of PBS and 50 µL of Matrigel (Corning Life Sciences; Bedford, MA, USA), and injected subcutaneously in the right flank of each mouse. The tumor volumes were calculated using Equation (1).

4.7. In vivo accumulation study

When tumor volumes of the eight mice reached 100–200 mm3, 30 µg/mouse of WL12-IR700 was administered intravenously to seven mice. The control mouse was not administered WL12-IR700. Imaging using an IVIS Spectrum (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) was performed at 1, 3, and 6 h post-administration (Ex: 710, Ex: 780, exposure time: 1 s). The radiant efficiency of the tumor was measured by surrounding it with a region of interest (ROI). The radiant efficiency was defined as the fluorescence emission radiance per incident excitation intensity.

4.8. In vivo therapeutic experiment

When tumor volumes of the mice reached 100–150 mm3, the mice were randomly divided into five groups (five mice/group; total 25 mice): i) no treatment (Control); ii) 100 J/cm2 of NIR light irradiation without WL12-IR700 (NIR light); iii) intravenous injection of WL12-IR700 (30 µg/mouse) without NIR light irradiation (Drug); and iv) or v) intravenous injection of WL12-IR700 (10 or 30 µg/mouse) and 100 J/cm2 of NIR light irradiation (PIT_10 µg or PIT_30 µg). After checking for the accumulation of WL12-IR700 using a Pearl Trilogy (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA), NIR light irradiation using an ML7710 laser system (Modulight; Tampere, Finland) and an FD1 frontal light distributor model (Medlight; Ecublens, Switzerland) in the PIT groups was performed 3 h after administration. The tumors of the mice were measured three times per week, and mice with a tumor volume > 2000 mm3 were treated as dead.

4.9. Statistical analysis

The obtained results are presented as means with standard deviations. Statistical analysis was performed using EZR software [

36]. In the cell viability assay, the non-irradiated and NIR light irradiated groups were compared in vitro using Welch’s

t-test. In the accumulation study, the average radiant efficiency was compared using the paired

t-test adjusted by the Holm method after repeated-measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). In the therapeutic experiment, the tumor volumes of each group were compared using Dunnett’s multiple comparison test after a one-way ANOVA with respect to the control group. The overall survival rate of each group was compared with that of the control group using the log-rank test. Statistical significance was set at

p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

We developed a novel peptide-based NIR-PIT drug targeting PD-L1 using WL12, which binds to PD-L1. We synthesized a WL12-IR700 conjugate and evaluated it in cells and tumor-bearing mice. In in vitro studies, PIT-like morphological changes in cells and decreased cell viability were observed in an NIR light dose- and drug concentration-dependent manner. Additionally, in animal experiments, the PIT groups showed significant suppression of tumor growth and extension of overall survival rates compared with the control group. These results indicate the potential of NIR-PIT using WL12-IR700 targeting PD-L1.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Elution profiles on a RP-HPLC and MS data of WL12 (1) and WL12-IR700 (2); Figure S2: A representative fluorescence image of WL12-IR700 at 1, 3, and 6 h post-injection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.O.; methodology, T.O. and H.H.; validation, T.O., N.K., A.K., and H.H.; formal analysis, T.O.; investigation, T.O. and A.K.; resources, H.H.; data curation, T.O.; writing—original draft preparation, T.O.; writing—review and editing, T.O., N.K., A.K., and H.H.; visualization, T.O.; supervision, H.H.; project administration, H.H.; funding acquisition, H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the JST FOREST Program (grant number JPMJFR205I to H.H.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee of Kansai Medical University (protocol code: 25-055; date of approval: February 21, 2025).

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NIR-PIT |

Near-infrared photoimmunotherapy |

| PD-L1 |

Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| NSCLC |

Non-small cell lung cancer |

| IR700 |

IRDye700DX |

| EGFR |

Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| PD-1 |

Programmed death-1 |

| PET |

Positron emission tomography |

| Fmoc |

9-Fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl |

| SPPS |

Solid-phase peptide synthesis |

| NHS |

N-hydroxysuccinimide |

| DIC |

Differential interference contrast |

| PI |

Propidium iodide |

| CCK-8 |

Cell Counting Kit-8 |

| HPLC |

High performance liquid chromatography |

| TFA |

Trifluoroacetic acid |

| TEAA |

Triethylammonium acetate |

| ESI |

Electrospray ionization |

| MS |

Mass spectra |

| DMF |

N, N-dimethylformamide |

| EDT |

1,2-Ethanedithiol |

| TIS |

Triisopropylsilane |

| TEA |

Triethylamine |

| RP |

Reverse phase |

| DIPEA |

N, N-diisopropylethylamine |

| DMSO |

Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| ATCC |

American Type Culture Collection |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium |

| FBS |

Fetal bovine serum |

| RPMI |

Roswell Park Memorial Institute |

| PBS |

Phosphate-buffered saline |

| ROI |

Region of interest |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

References

- Mitsunaga, M.; Ogawa, M.; Kosaka, N.; Rosenblum, L.T.; Choyke, P.L.; Kobayashi, H. Cancer cell-selective in vivo near infrared photoimmunotherapy targeting specific membrane molecules. Nat Med 2011, 17, 1685–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsunaga, M.; Nakajima, T.; Sano, K.; Kramer-Marek, G.; Choyke, P.L.; Kobayashi, H. Immediate in vivo target-specific cancer cell death after near infrared photoimmunotherapy. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Choyke, P.L. Near-infrared photoimmunotherapy of cancer. Acc Chem Res 2019, 52, 2332–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, H.; Choyke, P.L.; Ogawa, M. The chemical basis of cytotoxicity of silicon-phthalocyanine-based near infrared photoimmunotherapy (NIR-PIT) and its implications for treatment monitoring. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2023, 74, 102289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Ando, K.; Okuyama, S.; Moriguchi, S.; Ogura, T.; Totoki, S.; Hanaoka, H.; Nagaya, T.; Kokawa, R.; Takakura, H.; et al. Photoinduced ligand release from a silicon phthalocyanine dye conjugated with monoclonal antibodies: A mechanism of cancer cell cytotoxicity after near-infrared photoimmunotherapy. ACS Cent Sci 2018, 4, 1559–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Okada, T.; Okada, R.; Yasui, H.; Yamada, M.; Isobe, Y.; Nishinaga, Y.; Shimizu, M.; Koike, C.; Fukushima, R.; et al. Photoinduced actin aggregation involves cell death: A mechanism of cancer cell cytotoxicity after near-infrared photoimmunotherapy. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 8338–8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahara, M.; Okano, S.; Enokida, T.; Ueda, Y.; Fujisawa, T.; Shinozaki, T.; Tomioka, T.; Okano, W.; Biel, M.A.; Ishida, K.; et al. A phase I, single-center, open-label study of RM-1929 photoimmunotherapy in Japanese patients with recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol 2021, 26, 1812–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cognetti, D.M.; Johnson, J.M.; Curry, J.M.; Kochuparambil, S.T.; McDonald, D.; Mott, F.; Fidler, M.J.; Stenson, K.; Vasan, N.R.; Razaq, M.A.; et al. Phase 1/2a, open-label, multicenter study of RM-1929 photoimmunotherapy in patients with locoregional, recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck 2021, 43, 3875–3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, N.L.; Furusawa, A.; Choyke, P.L.; Kobayashi, H. Review of RM-1929 near-infrared photoimmunotherapy clinical efficacy for unresectable and/or recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, G.J.; Long, A.J.; Iwai, Y.; Bourque, K.; Chernova, T.; Nishimura, H.; Fitz, L.J.; Malenkovich, N.; Okazaki, T.; Byrne, M.C.; et al. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J Exp Med 2000, 192, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, H.; Okazaki, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Nakatani, K.; Hara, M.; Matsumori, A.; Sasayama, S.; Mizoguchi, A.; Hiai, H.; Minato, N.; et al. Autoimmune dilated cardiomyopathy in PD-1 receptor-deficient mice. Science 2001, 291, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Strome, S.E.; Salomao, D.R.; Tamura, H.; Hirano, F.; Flies, D.B.; Roche, P.C.; Lu, J.; Zhu, G.; Tamada, K.; et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: A potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med 2002, 8, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Teng, F.; Kong, L.; Yu, J. PD-L1 expression in human cancers and its association with clinical outcomes. Onco Targets Ther 2016, 9, 5023–5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, H.M.; Zito, C.R.; Turcu, G.; Baine, M.K.; Zhang, H.; Adeniran, A.; Sznol, M.; Rimm, D.L.; Kluger, Y.; Chen, L.; et al. PD-L1 studies across tumor types, its differential expression and predictive value in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res 2017, 23, 4270–4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, O.; Robert, C.; Daud, A.; Hodi, F.S.; Hwu, W.-J.; Kefford, R.; Wolchok, J.D.; Hersey, P.; Joseph, R.W.; Weber, J.S.; et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2013, 369, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Long, G.V.; Brady, B.; Dutriaux, C.; Maio, M.; Mortier, L.; Hassel, J.C.; Rutkowski, P.; McNeil, C.; Kalinka-Warzocha, E.; et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med 2015, 372, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaya, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Sato, K.; Harada, T.; Choyke, P.L.; Hodge, J.W.; Schlom, J.; Kobayashi, H. Near infrared photoimmunotherapy with avelumab, an anti-programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 8807–8817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, F.F.; Kano, M.; Furusawa, A.; Kato, T.; Okada, R.; Fukushima, H.; Takao, S.; Okuyama, S.; Choyke, P.L.; Kobayashi, H. Near-infrared photoimmunotherapy targeting PD-L1: Improved efficacy by preconditioning the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Sci 2024, 115, 2396–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Jiang, W.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Mao, J.; Zheng, W.; Hu, Y.; Shi, J. Advance in peptide-based drug development: Delivery platforms, therapeutics and vaccines. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2025, 10, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaoka, H.; Nagaya, T.; Sato, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Watanabe, R.; Harada, T.; Gao, W.; Feng, M.; Phung, Y.; Kim, I.; et al. Glypican-3 targeted human heavy chain antibody as a drug carrier for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. Mol Pharm 2015, 12, 2151–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otani, T.; Suzuki, M.; Takakura, H.; Hanaoka, H. Synthesis and biological evaluation of EGFR binding peptides for near-infrared photoimmunotherapy. Bioorg Med Chem 2024, 105, 117717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Lesniak, W.G.; Miller, M.S.; Lisok, A.; Sikorska, E.; Wharram, B.; Kumar, D.; Gabrielson, M.; Pomper, M.G.; Gabelli, S.B.; et al. Rapid PD-L1 detection in tumors with PET using a highly specific peptide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017, 483, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, D.; Lisok, A.; Dahmane, E.; McCoy, M.; Shelake, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Allaj, V.; Sysa-Shah, P.; Wharram, B.; Lesniak, W.G.; et al. Peptide-based PET quantifies target engagement of PD-L1 therapeutics. J Clin Invest 2019, 129, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yan, S.; Li, D.; Zhu, H.; Liu, B.; Liu, S.; Zhao, W.; Yang, Z.; Wu, N.; Li, N. Radiolabelled anti-PD-L1 peptide PET/CT in predicting the efficacy of neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy in resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Nucl Med 2025, 39, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Jiang, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, T.; Ding, J.; Nimmagadda, S.; Pomper, M.G.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Z.; et al. First-in-humans evaluation of a PD-L1-binding peptide PET radiotracer in non-small cell lung cancer patients. J Nucl Med 2022, 63, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, D.; Kim, D.W.; Park, H.-S. Cyclic peptides: Promising scaffolds for biopharmaceuticals. Genes (Basel) 2018, 9, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Ghosh, P.; Nitsche, C. Biocompatible strategies for peptide macrocyclisation. Chem Sci 2024, 15, 2300–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, D.; Mori, S.; Chadli, A.; Panda, S.S. Natural cyclic peptides: Synthetic strategies and biomedical applications. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Fang, Y.-C.; Li, J. PD-L1 expression levels on tumor cells affect their immunosuppressive activity. Oncol Lett 2019, 18, 5399–5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Nomoto, T.; Takemoto, H.; Matsui, M.; Tomoda, K.; Nishiyama, N. Effect of multiple cyclic RGD peptides on tumor accumulation and intratumoral distribution of IRDye 700DX-conjugated polymers. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.; Qu, P.; Miley, M.J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.; Ming, X. P-glycoprotein targeted photodynamic therapy of chemoresistant tumors using recombinant Fab fragment conjugates. Biomater Sci 2018, 6, 3063–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Sato, K.; Nagaya, T.; Okuyama, S.; Ogata, F.; Choyke, P.L.; Kobayashi, H. Near-infrared photoimmunotherapy with galactosyl serum albumin in a model of diffuse peritoneal disseminated ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 79408–79416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, L. Strategic approaches to optimizing peptide ADME properties. AAPS J 2015, 17, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karami Fath, M.; Babakhaniyan, K.; Zokaei, M.; Yaghoubian, A.; Akbari, S.; Khorsandi, M.; Soofi, A.; Nabi-Afjadi, M.; Zalpoor, H.; Jalalifar, F.; et al. Anti-cancer peptide-based therapeutic strategies in solid tumors. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2022, 27, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Yin, F.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, C. Current progress and remaining challenges of peptide-drug conjugates (PDCs): Next generation of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs)? J Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Structures of WL12 and an IR700 conjugate.

Figure 1.

Structures of WL12 and an IR700 conjugate.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the WL12-IR700 conjugate (2). Reagents and conditions: (a) (i) Fmoc-SPPS; (ii) N-(chloroacetoxy)succinimide, DMF, 20–25 °C, 40 min; (iii) TFA, EDT, TIS, H2O, 20–25 °C, 2 h; (iv) TEA, MeCN, H2O, 40 °C, 2 h (18% from the resin); (b) IR700 NHS ester, DIPEA, DMSO, 40 °C, 19 h (67% using IR700 NHS ester as the starting material).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the WL12-IR700 conjugate (2). Reagents and conditions: (a) (i) Fmoc-SPPS; (ii) N-(chloroacetoxy)succinimide, DMF, 20–25 °C, 40 min; (iii) TFA, EDT, TIS, H2O, 20–25 °C, 2 h; (iv) TEA, MeCN, H2O, 40 °C, 2 h (18% from the resin); (b) IR700 NHS ester, DIPEA, DMSO, 40 °C, 19 h (67% using IR700 NHS ester as the starting material).

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry analysis of WL12-IR700 following binding to MDA-MB-231 cells.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry analysis of WL12-IR700 following binding to MDA-MB-231 cells.

Figure 3.

Microscopic observations of cells before and after NIR light irradiation with WL12-IR700. The upper panels are DIC images, and the lower panels are fluorescence images. The white arrows indicate bleb formation.

Figure 3.

Microscopic observations of cells before and after NIR light irradiation with WL12-IR700. The upper panels are DIC images, and the lower panels are fluorescence images. The white arrows indicate bleb formation.

Figure 4.

Cell viability assessed by CCK-8 assays. (a) NIR light dose-dependent cell viability after treatment with WL12-IR700 (concentration: 2 μM). Control represents the untreated group, and its cell viability was deemed as 100%. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 with respect to treatment with 0 J/cm2 (Welch’s t-test). (b) Drug concentration-dependent cell viability after treatment with WL12-IR700 (NIR light: 20 J/cm2). Cell viability of 0 μM was deemed as 100%. **p < 0.01 with respect to treatment with 0 μM (Welch’s t-test).

Figure 4.

Cell viability assessed by CCK-8 assays. (a) NIR light dose-dependent cell viability after treatment with WL12-IR700 (concentration: 2 μM). Control represents the untreated group, and its cell viability was deemed as 100%. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 with respect to treatment with 0 J/cm2 (Welch’s t-test). (b) Drug concentration-dependent cell viability after treatment with WL12-IR700 (NIR light: 20 J/cm2). Cell viability of 0 μM was deemed as 100%. **p < 0.01 with respect to treatment with 0 μM (Welch’s t-test).

Figure 5.

Fluorescence intensity in the tumor after injection of WL12-IR700. (a) Radiant efficiency of individual mice (n = 7) and an uninjected mouse (Control). (b) Average radiant efficiency of drug-administered mice. *p < 0.05, n.s.: not significant (paired t-test adjusted by Holm method after repeated-measures ANOVA).

Figure 5.

Fluorescence intensity in the tumor after injection of WL12-IR700. (a) Radiant efficiency of individual mice (n = 7) and an uninjected mouse (Control). (b) Average radiant efficiency of drug-administered mice. *p < 0.05, n.s.: not significant (paired t-test adjusted by Holm method after repeated-measures ANOVA).

Figure 6.

Therapeutic effect of NIR-PIT with WL12-IR700 in tumor-bearing mice. (a) Average of tumor volume in each group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 with respect to the control group (Dunnett’s multiple comparison test after one-way ANOVA). (b) Overall survival rate for each group. The mice with a tumor volume > 2000 mm3 were treated as dead. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 with respect to the control group (log-rank test).

Figure 6.

Therapeutic effect of NIR-PIT with WL12-IR700 in tumor-bearing mice. (a) Average of tumor volume in each group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 with respect to the control group (Dunnett’s multiple comparison test after one-way ANOVA). (b) Overall survival rate for each group. The mice with a tumor volume > 2000 mm3 were treated as dead. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 with respect to the control group (log-rank test).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).