1. Introduction

Bladder cancer (BC) is one of the most common malignancies, with more than 610,000 new cases and 220,000 deaths annually. The disease ranks as the sixth most common cancer and the ninth leading cause of cancer death worldwide with highest incidence rates in Europe [

1].

At diagnosis, about 70% of tumors are still confined to the urothelium or lamina propria and have not invaded the muscle layer [

1]. For non–muscle-invasive BC (NMIBC), transurethral resection followed by intravesical chemotherapy with mitomycin C or gemcitabine is the standard therapy. Patients with intermediate, high and very high risk might also receive Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) immunotherapy to lower the likelihood of disease progression [

2]. However, recurrence rates remain high, affecting about 31-78% of patients depending on risk group within 5 years after treatment [

3]. Regular cystoscopic follow-up is therefore required. Progression to muscle-invasive BC (MIBC) necessitates radical treatment such as cystectomy with chemotherapy or radio-chemotherapy [

4]. In metastatic disease, prognosis for BC patients is poor with median survival of only a few months [

5]. Recent advances in the treatment of BC include the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) [

6] and the application of antibody drug conjugates (ADC) such as enfortumab vedotin [

7] and sacituzumab govitecan [

8]. Despite these developments, clinical outcomes in BC remain unsatisfactory. Novel targeted therapies are needed to eradicate residual tumor cells in localized disease, to reduce recurrence, and to improve both survival and quality of life.

Photoimmunotherapy (PIT) represents a highly specific approach within the field of targeted photodynamic therapy (PDT). In this strategy, tumor-specific monoclonal antibodies, antibody fragments, or ligands are covalently coupled to photosensitizers (PS), thereby enabling preferential accumulation of the conjugates in malignant tissues through recognition of cell-surface antigens. Upon adequate tumor localization, the PS moiety can be selectively activated by radiation with red or near-infrared light, which penetrates tissue effectively and is non-ionizing in nature. Activation of the PS leads to the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including singlet oxygen, peroxides, and hydroxyl radicals via photochemical reactions. ROS induce oxidative stress, leading to damage of cellular organelles and biomolecules, followed by the release of neoantigens and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), ultimately promoting immunogenic cell death [

9]. PIT is particularly suitable for tumors that both (i) express antigens amenable to antibody targeting and (ii) are accessible to light delivery, either externally or via interstitial fiber-optic approaches. Compared to conventional chemotherapy or radiotherapy, PIT provides spatiotemporal precision and reduced systemic toxicity, while retaining the immunological advantages of PDT [

10].

For the PIT of NMIBC, cell surface antigens like the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), Nectin cell adhesion molecule 4 (Nectin-4) and the Trophoblast cell surface antigen-2 (TROP-2) are conceivable targets.

Overexpression of EGFR, a tyrosine kinase of the ErbB receptor family, correlates with tumor grade, muscle invasion and recurrence of BC and therefore serves as a prognostic marker. Based on immunohistological studies, EGFR is present in about 12-40% of NMIBC patients [

11,

12].

The cell adhesion molecule Nectin-4 is particularly overexpressed in various solid tumors, including urothelial cancer [

13,

14]. It promotes tumor angiogenesis, cell growth, proliferation, migration and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and was found to be heterogeneously expressed in approximately 87-90% of patients with NMIBC [

15,

16,

17]. Nectin-4 serves as target of the ADC enfortumab vedotin (EV), which is indicated as first-line therapy in combination with pembrolizumab for patients not suitable for platinum chemotherapy or for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer, who have previously received ICI and a platinum-containing chemotherapy [

18].

TROP-2 is a type I transmembrane glycoprotein consisting of 323 amino acids, serves as a calcium signal transducer and contributes to proliferation, adhesion, Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and death of tumor cells [

13,

19,

20]. In an immunohistological panel of 102 patients with NMIBC, TROP-2 expression was detected in all samples and high expression of TROP-2 was significantly associated with tumor grade (P=0.001), stage (P<0.001), and recurrence (P=0.03) [

21]. TROP-2 antigen is the target of the ADC sacituzumab govitecan, which is approved for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer in patients previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy and ICI [

22].

We have recently published the novel silicon phthalocyanine dye WB692-CB2 (Abs.

max 692 nm / Em.

max 703 nm), which is the first light activatable PS that can be directly conjugated to cysteines via a maleimide linker. Following incubation of prostate cancer cells with a conjugate composed of a cysteine-modified antibody directed against the prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) and WB692-CB2, subsequent red-light irradiation effectively induced pyroptosis as main cell death mechanism [

9]. In the present study, we established a PIT strategy against BC cells employing WB692-CB2-conjugated antibodies directed against EGFR, Nectin-4 and TROP-2.

2. Results

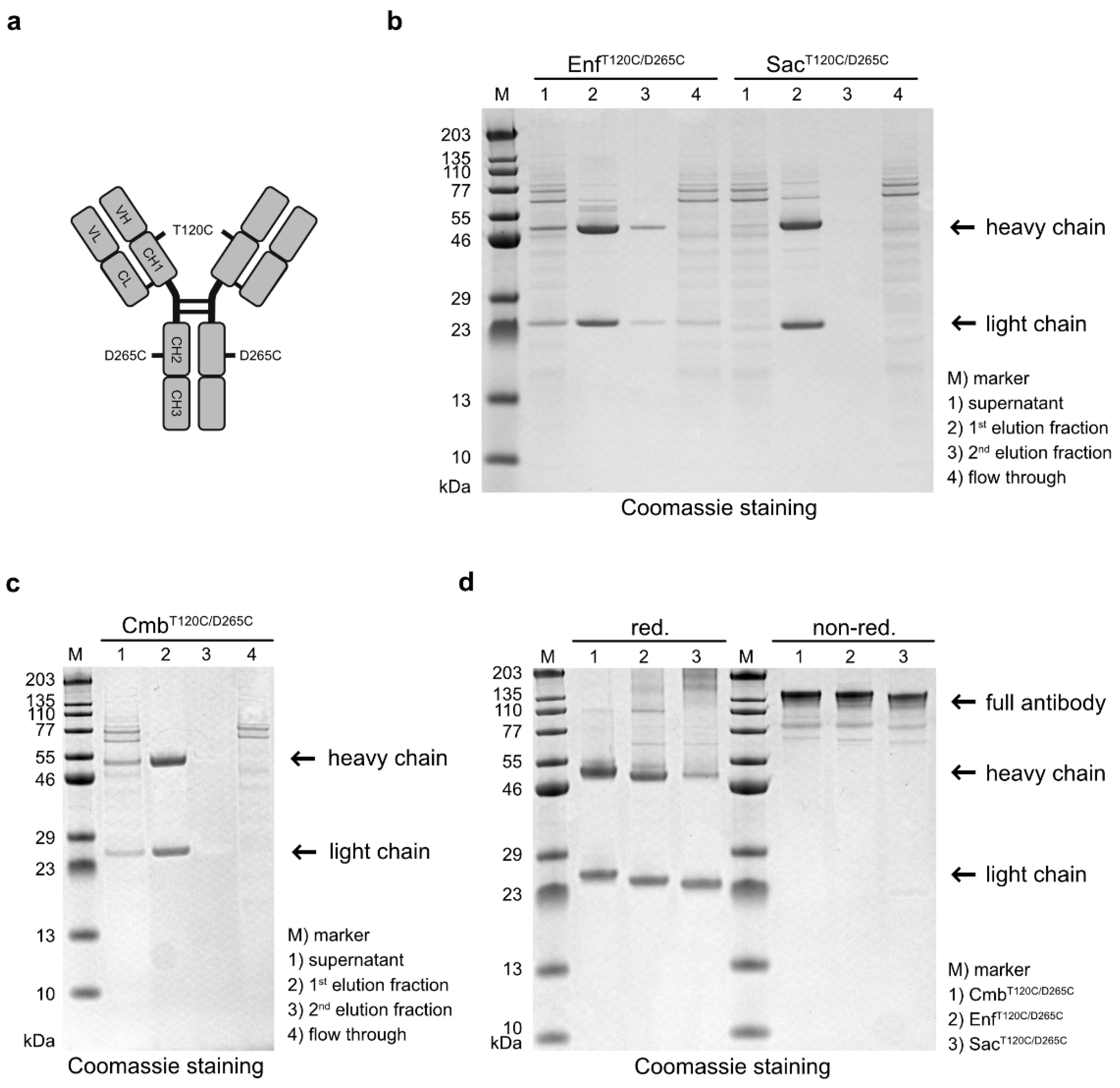

Antibody variants targeting EGFR, Nectin-4 and TROP-2 were generated by cloning the VH and VL domains of Cetuximab (Cmb), Enfortumab (Enf) and Sacituzumab (Sac), respectively, into human hIgG1 heavy- and light chain expression vectors carrying cysteine mutations at positions T120 and D265 in the heavy chain (

Figure 1a). After expression in Expi293T cells and purification by affinity chromatography, the cysteine-modified antibodies Cmb

T120C/D265C, Enf

T120C/D265C and Sac

T120T/D265C were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. All antibodies were detected in the first elution fraction (

Figure 1b,c). Under reducing conditions, the expected ~ 49-50 kDa heavy and ~ 23 kDa light chains were observed, whereas under non-reducing conditions, intact antibodies with a molecular weight of ~ 145 kDa were detected (

Figure 1d). This proved that all antibody variants were correctly assembled as full-length IgG molecules in our expression system.

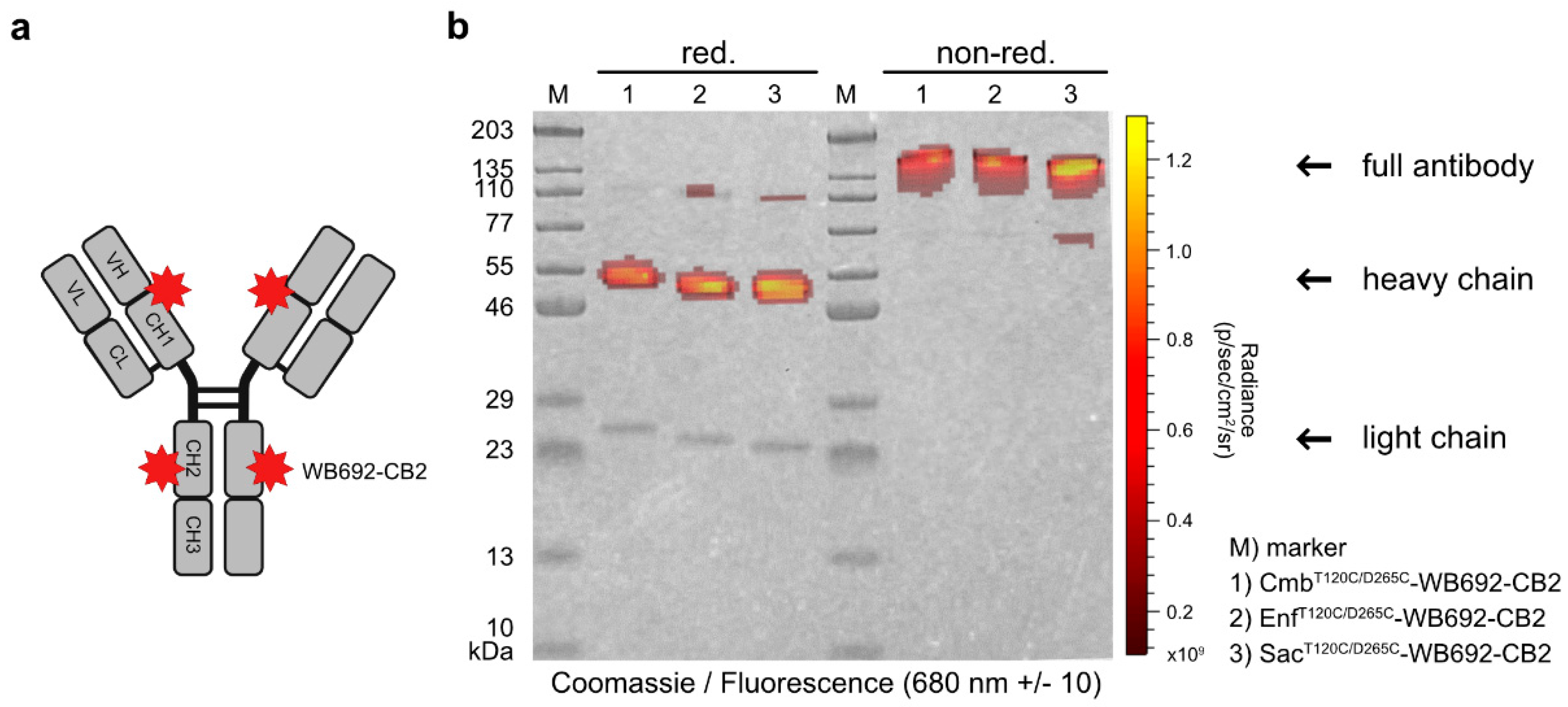

In the next step, the PS dye WB692-CB2 was coupled to the cysteine-modified antibodies via a maleimide linker (

Figure 2a). The insertion of two cysteine mutations per heavy chain theoretically allows the coupling of up to four dye molecules per antibody. Using our established coupling protocol, in which ten dye molecules were added per antibody molecule, we achieved dye-to-antibody ratios of 3.05, 3.08 and 3.13 for Cmb

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2, Enf

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 and Sac

120T/265C-WB692-CB2, respectively. Analysis of the conjugates under red light (680 ± 10 nm) revealed fluorescence signals corresponding to the heavy chains (

Figure 2b), confirming the successful coupling of the dye to the cysteine mutations.

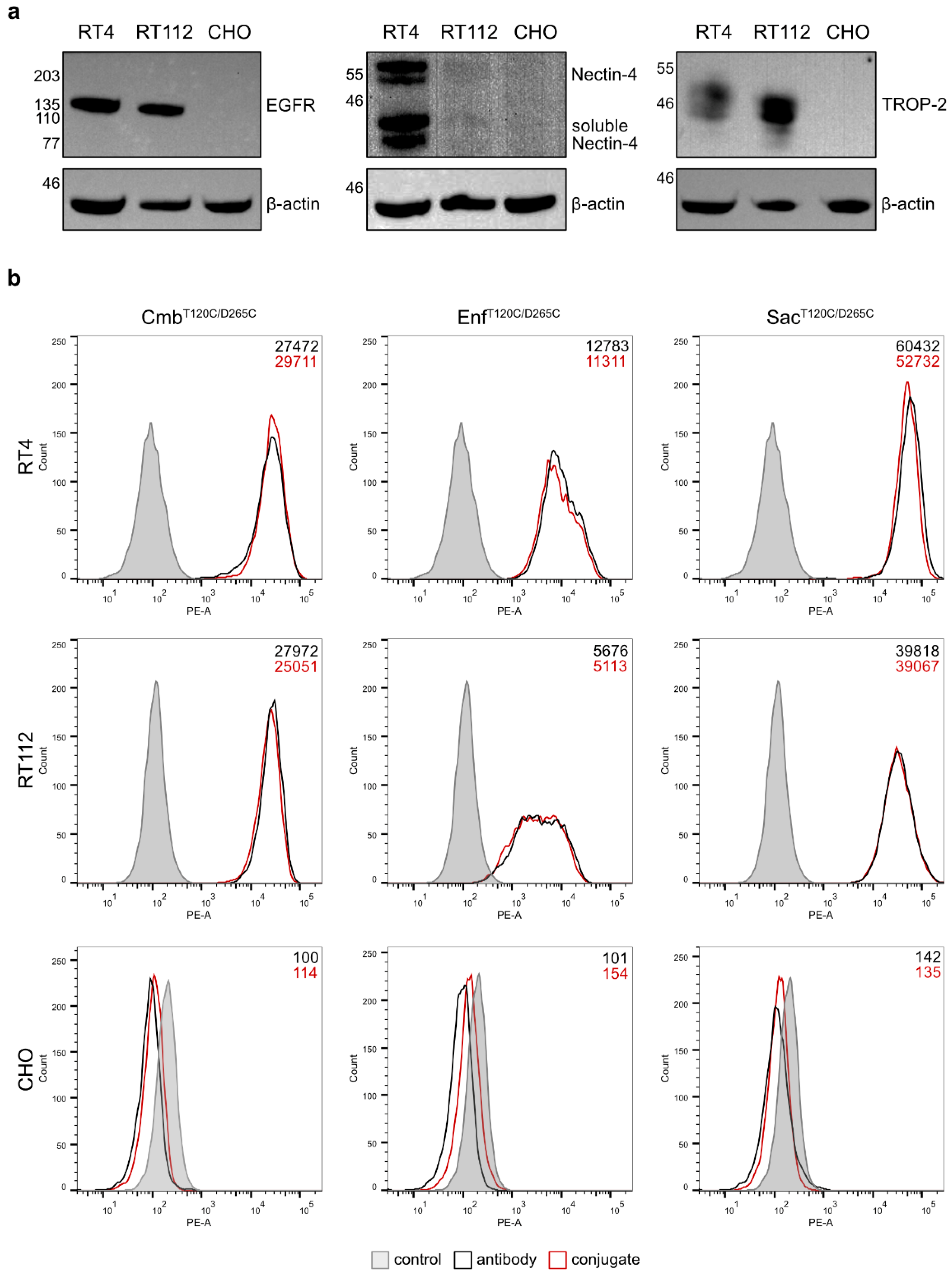

The binding properties of the antibodies and their conjugates were evaluated on RT4 and RT112 BC cells. Western Blot analyses of cell lysates confirmed RT4 cells were EGFR

high, Nectin-4

high and TROP-2

high, whereas RT112 cells were characterized as EGFR

high, Nectin-4

low and TROP-2

high. The hamster cell line CHO served as a negative control and showed no detectable expression of any of the three antigens (

Figure 3a). Flow cytometry revealed strong and specific binding of the antibodies and their corresponding conjugates to RT4 and RT112 cells, with the highest mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values observed for Sac

T120C/D265C, followed by Cmb

T120C/D265C and Enf

T120C/D265C, and their respective conjugates (

Figure 3b). No binding was detected in CHO control cells. This proved that the coupling of our dye WB692-CB2 did not impair the antigen-specific binding of the antibodies.

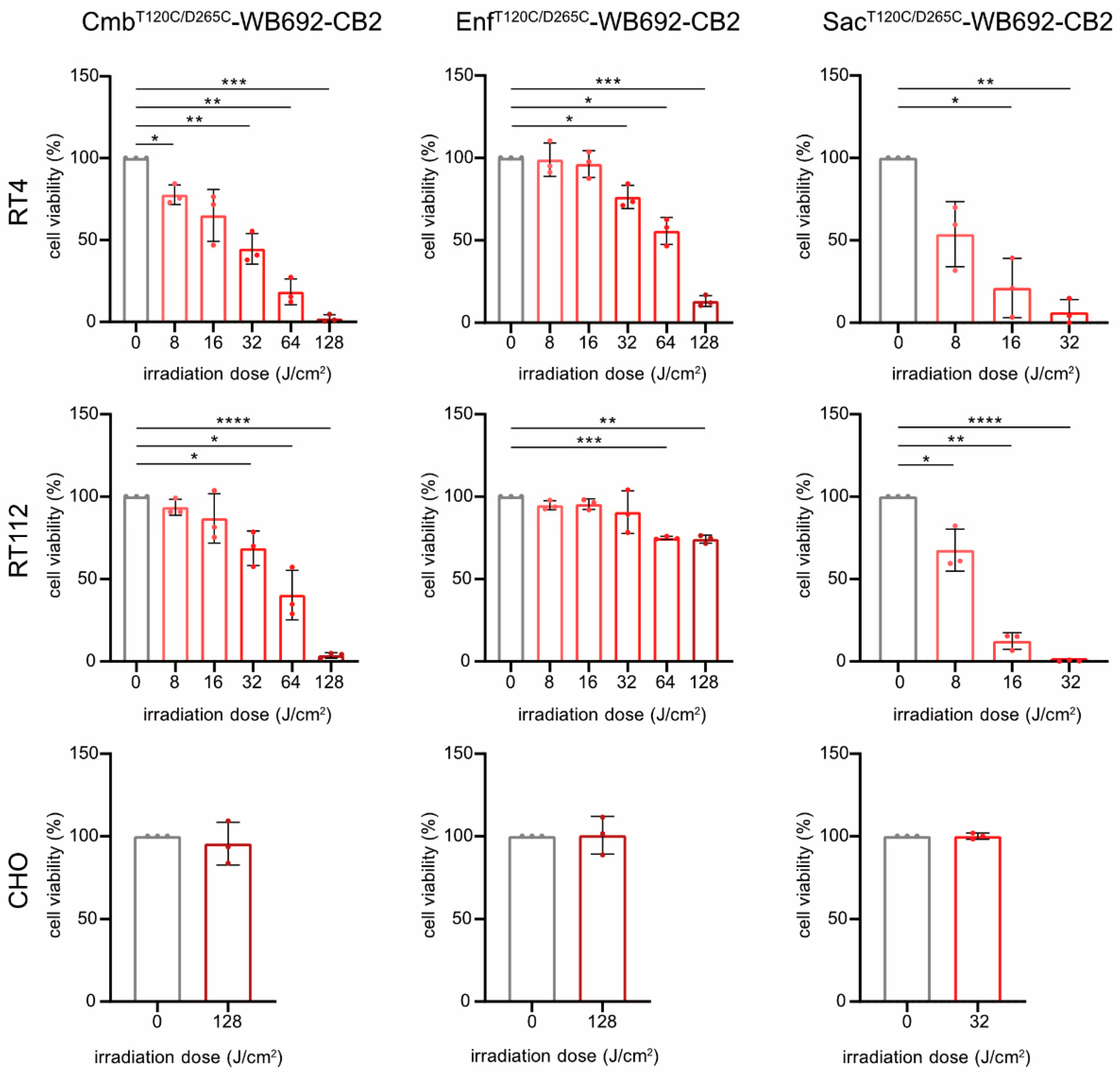

For PIT, BC cells were incubated with 10 µg/ml of each conjugate and subsequently irradiated with varying doses of red light (690 nm, 0-128 J/cm²). All conjugates induced light dose-dependent cytotoxicity in the target cells (Sac

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 > Cmb

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 > Enf

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2), consistent with their relative binding affinities. Treatment with Sac

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 significantly reduced RT4 cell viability to 6.3 ± 7.6% and completely eradicated RT112 cells at a light dose of 32 J/cm². Nearly complete ablation of BC cells was achieved with Cmb

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 at a dose of 128 J/cm², resulting in 2.1 ± 2.3% and 3.6 ± 1.5% viability for RT4 and RT112 cells, respectively. In contrast, Enf

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 exhibited the weakest phototoxic response, reducing RT4 cell viability to 13.1 ± 3.3% and RT112 cell viability to 74.2 ± 2.4% at 128 J/cm². No cytotoxic effects were observed in the antigen-negative CHO control under any conditions, demonstrating the high specificity and safety of our PIT approach (

Figure 4).

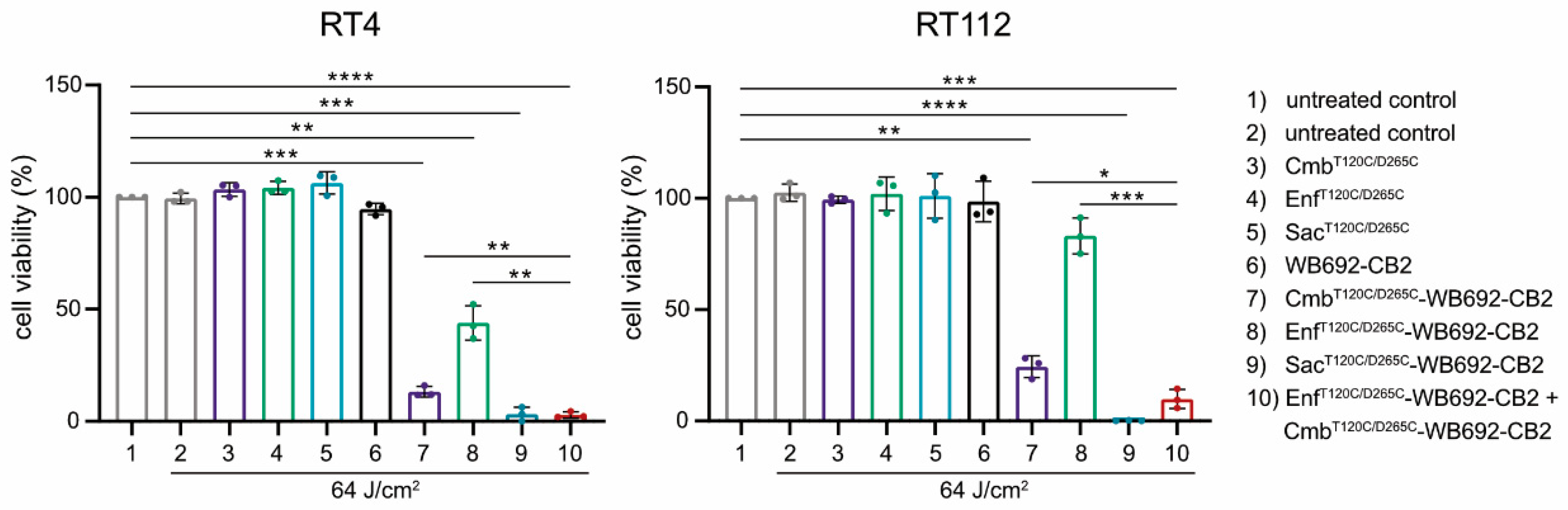

The simultaneous application of multiple conjugates was investigated to assess potential additive cytotoxic effects. BC cells were co-incubated with the conjugates Cmb

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 and Enf

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 and subsequently irradiated with a light dose of 64 J/cm². Indeed, the combined treatment with both conjugates resulted in a markedly enhanced cytotoxic response compared with either conjugate alone, indicating additive phototoxic effects. In contrast, neither the unconjugated antibodies nor the free WB692-CB2 dye exhibited any cytotoxicity under the same experimental conditions, confirming that light-induced cell killing was strictly dependent on targeted photoactivation of the conjugates (

Figure 5).

Collectively, these results demonstrate that cysteine-engineered antibody dye conjugates targeting EGFR, Nectin-4, and TROP-2 retain their antigen-specificity and induce highly selective, light-dependent cytotoxicity in BC cells. Moreover, the observed additive effects upon combined application of different conjugates suggest an additive therapeutic potential that could enhance treatment efficacy and offer meaningful benefits for patients with heterogeneous tumor antigen expression.

3. Discussion

EGFR, Nectin-4 and TROP-2 represent valuable targets for the PIT of NMIBC, as they are highly expressed on the surface of BC cells and undergo internalization after antibody binding [

12,

14,

20]. In this study, we demonstrate that the antigen-binding domains of Cetuximab, Enfortumab and Sacituzumab, originally employed as ADCs for the targeted delivery of cytotoxic agents to cancer cells [

23,

24], can also be applied to generate cysteine-modified antibodies as vehicles for intracellular transport of the photosensitizer dye WB692-CB2 in PIT. Consequently, the PIT approach against BC could be extended to other therapeutic antibodies, which are currently being tested in clinical trials in the form of ACDs directed against human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2), tissue factor (TF) or epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) [

25].

Based on the MFI values gained from our flow cytometric analyses, we found highest binding of the anti-TROP-2 conjugate SacT120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 to RT4 and RT112 cells, followed by the anti-EGFR conjugate CmbT120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 and the anti-Nectin-4 conjugate EnfT120C/D265C-WB692-CB2. Accordingly, the highest cytotoxicity after PIT was achieved with the conjugate SacT120C/D265C-WB692-CB2. At a conjugate concentration of 10 µg/ml and a light dose of 32 J/cm², almost complete elimination of the BC cells was observed. In contrast, CmbT120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 required a fourfold higher light intensity (128 J/cm²) to achieve comparable efficacy, while EnfT120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 induced only limited cytotoxicity, reducing RT112 and RT4 cell viability by approximately 26% and 87% at the same dose, respectively. Overall, we identified SacT120T/D265C-WB692-CB2 as the most effective conjugate for PIT of BC cells, followed by CmbT120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 and EnfT120C/D265C-WB692-CB2. Beyond differences in antigen expression, the observed variation in the cytotoxicity among the conjugates may be attributable to differences in antigen internalization kinetics or endolysosomal degradation. Further investigations are required to elucidate the relative contributions of these processes to PIT efficacy with our dye.

We have recently shown that PIT with WB692-CB2 induced pyroptosis as main cell death mechanism in prostate cancer cells [

9]. Pyroptosis is a nonapoptotic form of programmed cell death characterized by inflammasome activation and caspase-dependent cleavage of gasdermin D, leading to the formation of pores in the cell membrane and cell burst [

26]. This causes the release of pro-inflammatory molecules that recruit lymphocytes and boost the immune system’s capacity to eliminate tumor cells. Induction of pyroptosis with antineoplastic agents is increasingly coming into focus to combat apoptosis-resistant tumor cells and to enhance the antitumor efficacy of ICI [

27]. Our future investigations will show whether this is also the case in BC cells. If confirmed, PIT could not only eradicate tumor cells but also be used to prime the immune system of NMIBC patients against tumor cells that have already spread [

28].

NMIBC can be multifocal and exhibits pronounced intra- and intertumoral antigen heterogeneity, arising from genetic mutations, altered molecular pathways, and the influence of the tumor microenvironment. This inherent heterogeneity influences disease progression, recurrence, and therapeutic outcome [

17,

29,

30]. In clinical application of PIT, it could therefore be advantageous to target different tumor antigens simultaneously. We therefore treated the BC cells with Cmb

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 and Enf

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 and found additive cytotoxic effects. Our observations are in line with another study, where higher efficacy was reached with a combinatorial PIT using conjugates consisting of the anti-EGFR antibody panitumumab or the anti-HER-2 antibody trastuzumab and the lysine-coupling PS dye IR700 compared to monotherapies in BC cells [

31]. In the context of personalized medicine, it may become feasible to access antigen expression profiles before and during PIT by biopsies and to tailor the administration of appropriate antibody dye conjugates accordingly. This could improve therapeutic outcome and reduce the risk of tumor recurrence.

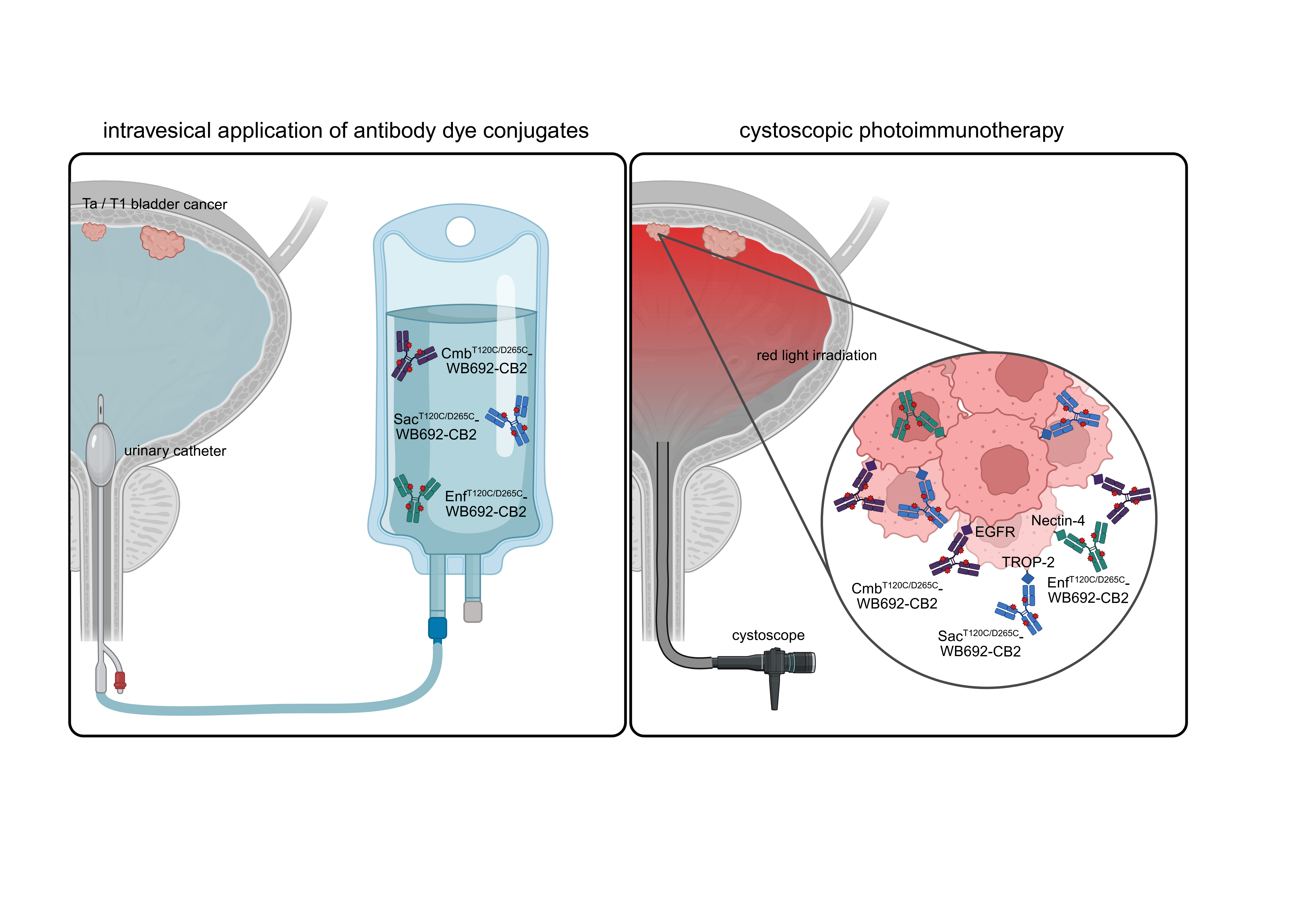

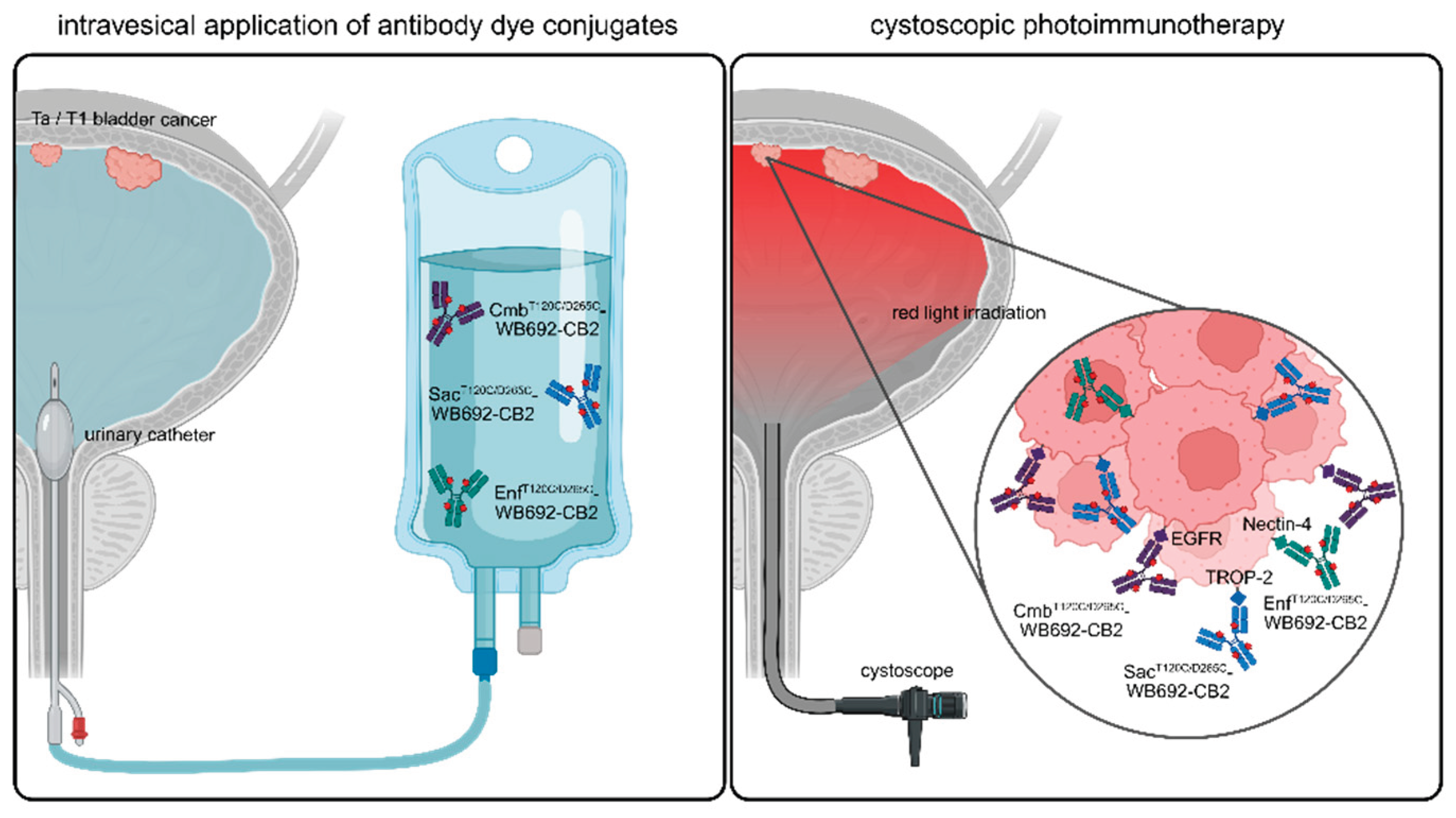

In this study, we demonstrated that PIT represents a novel, targeted and gentle therapeutic option for NMIBC. It can be performed in future by instilling the bladder with respective antibody dye conjugates via a catheter, followed by light irradiation using a cystoscope (

Figure 6). Due to its high specificity and the use of harmless light, PIT can be considered a gentle and effective alternative to conventional BCG treatment or chemotherapy.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Lines

The EGFR-, Nectin-4- and TROP-2-positive cell lines RT4, derived from a patient with a recurrent well-differentiated transitional papillary tumor, and RT112, derived from a patient with a transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder, were purchased from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (Leibniz Institute, Braunschweig, Germany). The negative control cell line CHO was obtained from Gibco (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). RT4 cells were cultivated in EMEM medium (Cytion, Eppelheim, Germany), RT112 cells in RPMI1640 medium (Gibco), and CHO cells in F-12 Nutrient Mixture Medium (Gibco) at 37°C and 5% CO2. All media were supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/ml, 100 mg/l, Sigma Aldrich).

4.2. Antibody Generation

For the generation of the heavy chains of the cysteine-modified antibodies Cetuximab (Cmb

T120C/D265C, www.kegg,jp: D03455), Enfortumab (Enf

T120C/D265C, www.kegg,jp: D11524) and Sacituzumab (Sac

T120C/D265C, www.kegg,jp: D10984), the variable heavy chain (V

H) domains and constant heavy chain (CH) domain genes of a hIgG1 antibody carrying the T120C and D265C (EU numbering) cysteine mutations were synthetized by Gene Art technology optimized for eukaryotic expression (Invitrogen, Regensburg, Germany). The variable light chains (VL) domains of the three antibodies were synthesized in paralell. The heavy chains were cloned into the expression vector pCSEH1c, and the light chains into the expression vector pCSL3k containing a human IgG1 constant light chain (CL) domain, as described previously [

9]. Transformation of the constructs was carried out in XL1-Blue MRF’ supercompetent

E. coli cells (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany), and plasmid DNA was purified using the NucleoBond® Xtra Maxi Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). All sequences were verified by Microsynth Seqlab (Göttingen, Germany).

Recombinant antibody expression was performed in EXPI293F cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using established protocols (PMID: 39246837, Wolf et al., 2024). The antibodies were purified from cell culture supernatant by affinity chromatography. In brief, supernatant containing the antibody was 1:1 diluted in PBS (pH 7.0) and pumped over a Protein G column (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA). The column was washed with PBS (pH 7.0), and the antibodies were eluted with 0.1 M glycine-HCl (pH 2.5) in two 1 ml fractions. After neutralization with 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), the antibodies were dialyzed against PBS (pH 7.4), and stored at -20 °C. Final antibody concentrations were determined using a NanoDrop Lite™-spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

3. Generation of the Antibody-Dye Conjugates

The cysteine modified antibodies Cmb

T120C/D265C, Enf

T120C/D265C and Sac

T120C/D265C were diluted in PBS, 1mM EDTA (pH 7.4) and reduced with 40 equimolar Tris-(2-Carboxyethyl)phosphine, hydrochloride (TCEP, Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) for 3 h at 37 °C on a shaking platform. Overnight dialysis against PBS, 1mM ETDA (pH 7.4) at 4°C was followed by re-oxidation with 30 equimolar dehydroascorbic acid (dhAA, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) for 4 h at room temperature. For dye conjugation, 10-fold equimolar WB692-CB2 dye was added for 1h at room temperature on a shaker, protected from light. 25-fold equimolar N-acetyl-L-cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich) was added for 15 minutes to quench the reaction. For elimination of unbound dye, the antibody-dye-solutions were purified using Protein G affinity chromatography (Cytiva), followed by dialysis against PBS (7.0). To quantify the protein concentration, Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was utilized. Dye to protein ratios were calculated as described [

9].

4. SDS PAGE

The antibodies CmbT120C/D265C, EnfT120C/D265C and SacT120C/D265C, as well as their corresponding antibody dye conjugates CmbT120C/D265C-WB692-CB2, EnfT120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 and SacT120C/D265C-WB692-CB2, were analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing and non-reducing conditions. Protein bands were visualized by Coomassie staining (Protein Ark, Sheffield, UK) and fluorescence-based imaging (λ = 680 nm) using an IVIS 200 Imaging System (Revvity, Waltham, MA, USA).

5. Western Blot

Cells were lysed in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0,5% sodium deoxycholate, 0,05% SDS and 1% Igepal. Protein concentrations were determined using the Quick Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Equal amounts of protein (50 µg per lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE and subsequently transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Following transfer, EGFR, Nectin-4 and TROP-2 were detected using polyclonal rabbit anti-human EGFR IgG (#sc-03-G, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), polyclonal rabbit anti-human Nectin-4 IgG (#17402S, Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA, USA), and monoclonal rabbit anti-human TROP-2 IgG (#90540, Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA, USA). Horse radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated polyclonal goat anti-rabbit IgG (#P0448, Dako Denmark A/S, Glostrup, Denmark) was used as secondary antibody. ß-actin was detected as loading control using an HRP-conjugated mouse anti-human ß-actin antibody (#HRP-66009, Proteintech Group Inc., Rosemont, IL, USA). Signals were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system and imaged with an INTAS Chemo Star Imager (INTAS Science Imaging Instruments, Göttingen, Germany).

6. Flow Cytometry

Cell binding of the antibodies and antibody dye conjugates to EGFR-, Nectin-4 and TROP-2 positive BC cell lines (RT112 and RT4) and to the antigen-negative control cell line CHO was analyzed by flow cytometry. For this, 2x105 cells/well were seeded and incubated with 10 µg/ml of each antibody or antibody dye conjugate in a dilution buffer containing PBS with 3% fetal bovine serum and 0.1% sodium azide for 1 hour in the dark. A human IgG isotype control (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) was used as negative control. After washing, cells were incubated with goat anti human IgG-PE secondary antibody (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) (1:500) and eBioscience™ Fixable Viability Dye eFluor™ 450 (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) (1:1000) for 30 minutes at 4°C in the dark. Following a final washing step, the cells were resuspended in the dilution buffer and analyzed using a FACSymphony™ A1 Flow Cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany). Mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) were calculated using FlowJoTM software (Becton Dickinson).

7. Photoimmunotherapy

Target cells were seeded at a concentration of 1,25x105 cells/ml into 35 mm cell culture dishes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and cultivated for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. On the following day, cells were treated for 24 h with either 10 µg/ml of the antibodies CmbT120C/D265C, EnfT120C/D265C or SacT120C/D265C, their corresponding conjugates, or an equimolar concentration of free dye WB692-CB2. Untreated cells served as controls. After treatment, cells were washed three times with PBS and phenol-red free medium was added before irradiation. Irradiation was performed using a light-emitting diode (λ = 690 nm; LED L690-66-60, Marubeni, Tokyo, Japan) at varying light doses ranging from 0 to 128 J/cm²). For combinatorial PIT, RT112 and RT4 cells were treated with 10 µg/ml of CmbT120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 or EnfT120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 alone or in combination and irradiated with 64 J/cm² red light.

Twenty-four hours after PIT, cells were trypsinized, stained with Erythrosin B (Logos Biosystems, Gyeonoggi-do, South Korea), and the numbers of living cells were determined using a Neubauer Counting Chamber. Number of living cells of the untreated and non-irradiated control was defined as 100%, and numbers of living cells for the different treatment conditions were calculated relative to this control. Data represents mean values ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis were calculated using an unpaired Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction in GraphPad Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our study demonstrates that EGFR, Nectin-4, and TROP-2 are effective targets for PIT of NMIBC using cysteine-engineered antibody–dye conjugates. Among them, the TROP-2–directed conjugate SacT120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 showed the highest cytotoxic efficacy. These findings highlight PIT as a promising, targeted, and minimally invasive therapeutic approach for NMIBC that could complement or replace current intravesical treatments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.W and P.W.; methodology, I.W. and P.W.; investigation: I.W., N.G., C.R., S.S.-S., J.S.; validation, I.W., N.G. and P.W.; formal analysis, N.G. and I.W.; resources, D.B.W., C.G. and P.W.; writing—original draft preparation, I.W., N.G and P.W; writing—review and editing, I.W., N.G., S.S.-S., J. S., D.B.W., A.M., C.G. and P.W.; visualization, I.W., N.G.; supervision, I.W. and P.W.; project administration, P.W.; funding acquisition, D.B.W, P.W.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG, grant no. WO 2178/3–1 to P.W.), the Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK, grant no. 03THW15H04 to P.W.) and the Federal Ministry of Research, Technology and Space (BMFTR, grant no. 03VP12060 to P.W. and D.B.W.) and supported by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Freiburg.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank E.V. Wenzel and S. Dübel (TU Braunschweig) for providing the cloning vectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADC |

antibody drug conjugate |

| BC |

bladder cancer |

| BCG |

bacillus calmette-guérin |

| Cmb |

Cetuximab |

| DAMPs |

damage-associated molecular patterns |

| EGFR |

epidermal growth factor receptor |

| Enf |

Enfortumab |

| EpCAM |

epithelial cell adhesion molecule |

| EV |

Enfortumab Vedotin |

| HER-2 |

epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| ICI |

immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| MIBC |

muscle-invasive bladder cancer |

| NMIBC |

non–muscle-invasive BC |

| PDT |

photodynamic therapy |

| PIT |

photoimmunotherapy |

| PS |

photosensitizer |

| PSMA |

prostate specific membrane antigen |

| ROS |

reactive oxygen species |

| Sac |

Sacituzumab |

| TF |

tissue factor |

| TROP-2 |

trophoblast cell-Surface antigen 2 |

References

- Kaufman, D.S.; Shipley, W.U.; Feldman, A.S. Bladder cancer. Lancet (London, England) 2009, 374, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabe-Heyne, K.; Henne, C.; Mariappan, P.; Geiges, G.; Pöhlmann, J.; Pollock, R.F. Intermediate and high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: An overview of epidemiology, burden, and unmet needs. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1170124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, J.Y.; Kamat, A.M.; Black, P.C.; Grivas, P.; Shariat, S.F.; Babjuk, M. Recurrence mechanisms of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer - a clinical perspective. Nature reviews. Urology 2022, 19, 280–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenis, A.T.; Lec, P.M.; Chamie, K.; Mshs, M.D. Bladder cancer: A review. Jama 2020, 324, 1980–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigi, A.; Vafaei-Nodeh, S.; Huang, L.; Sun, S.Z.; Ko, J.J. Survival outcomes associated with first and second-line palliative systemic therapies in patients with metastatic bladder cancer. Current oncology (Toronto, Ont.) 2021, 28, 3812–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massari, F.; Di Nunno, V.; Cubelli, M.; Santoni, M.; Fiorentino, M.; Montironi, R.; Cheng, L.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; Battelli, N.; Ardizzoni, A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for metastatic bladder cancer. Cancer treatment reviews 2018, 64, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman-Censits, J.; Maldonado, L. Targeted treatment of locally advanced and metastatic urothelial cancer: Enfortumab vedotin in context. OncoTargets and therapy 2022, 15, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontes, M.S.; Vargas Pivato de Almeida, D.; Cavalin, C.; Tagawa, S.T. Targeted therapy for locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer (muc): Therapeutic potential of sacituzumab govitecan. OncoTargets and therapy 2022, 15, 1531–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, I.; Storz, J.; Schultze-Seemann, S.; Esser, P.R.; Martin, S.F.; Lauw, S.; Fischer, P.; Peschers, M.; Melchinger, W.; Zeiser, R.; Gorka, O.; Groß, O.; Gratzke, C.; Brückner, R.; Wolf, P. A new silicon phthalocyanine dye induces pyroptosis in prostate cancer cells during photoimmunotherapy. Bioact Mater 2024, 41, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.; Szoo, M.J.; van Bergen, T.D.; Seppelin, A.; Oh, J.; Saad, M.A. Near-infrared photoimmunotherapy: Mechanisms, applications, and future perspectives in cancer research. Antibody therapeutics 2025, 8, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, N.H.; Liu, H.S.; Yang, H.B.; Chan, S.H.; Su, I.J. Expression patterns of erbb receptor family in normal urothelium and transitional cell carcinoma. An immunohistochemical study. Virchows Archiv : an international journal of pathology 1997, 430, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hambalie, L.A.; Rahaju, A.S.; Mastutik, G. The correlation of emmprin and egfr overexpression toward muscle invasiveness in urothelial carcinoma of bladder. Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology 2021, 15, 2709–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ma, L.; Li, J.; Sun, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, T.; Xing, D.; Yan, S.; Zhang, M. Trop2-targeted therapies in solid tumors: Advances and future directions. Theranostics 2024, 14, 3674–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikanjam, M.; Pérez-Granado, J.; Gramling, M.; Larvol, B.; Kurzrock, R. Nectin-4 expression patterns and therapeutics in oncology. Cancer Lett 2025, 622, 217681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Han, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Li, G.; Xu, C.; Yin, M.; Zhou, P.; Shi, F.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G. Role of nectin-4 protein in cancer (review). International journal of oncology 2021, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman-Censits, J.H.; Lombardo, K.A.; Parimi, V.; Kamanda, S.; Choi, W.; Hahn, N.M.; McConkey, D.J.; McGuire, B.M.; Bivalacqua, T.J.; Kates, M.; Matoso, A. Expression of nectin-4 in bladder urothelial carcinoma, in morphologic variants, and nonurothelial histotypes. Applied immunohistochemistry & molecular morphology : AIMM 2021, 29, 619–625. [Google Scholar]

- Garczyk, S.; Degener, S.; Bischoff, F.; Schnitzler, T.; Salz, A.; Golz, R.; Buchner, A.; Schulz, G.B.; Schneider, U.; Gaisa, N.T.; Knüchel, R. Heterogenous nectin4 expression in urothelial high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Virchows Archiv : an international journal of pathology 2022, 481, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, K.S. Enfortumab vedotin to treat urothelial carcinoma. Drugs of today (Barcelona, Spain : 1998) 2020, 56, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Lan, H.; Hou, J.; Zhang, N.; Wang, X.; Lu, H. Targeting trop-2 in cancer: Recent research progress and clinical application. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Reviews on cancer 2023, 1878, 188902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Xiao, H.; Na, F.; Sun, J.; Guan, Q.; Liu, R.; Cai, L.; Li, H.; Zhao, M. Evolution of trop2: Biological insights and clinical applications. European journal of medicinal chemistry 2025, 296, 117863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, G.; Jiang, H.; Liu, M.; Chen, H.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Bo, J. Trop2 is associated with the recurrence of patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2017, 10, 1643–1650. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew Thomas, V.; Tripathi, N.; Agarwal, N.; Swami, U. Current and emerging role of sacituzumab govitecan in the management of urothelial carcinoma. Expert review of anticancer therapy 2022, 22, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.D.S.; Nogueira, K.A.B.; Fernandes, L.C.C.; Martins, J.R.P.; Reis, A.V.F.; Neto, J.B.V.; Júnior, I.; Pessoa, C.; Petrilli, R.; Eloy, J.O. Egfr targeting for cancer therapy: Pharmacology and immunoconjugates with drugs and nanoparticles. International journal of pharmaceutics 2021, 592, 120082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.J.; Galsky, M.D. Precision medicine in urothelial carcinoma: Current markers to guide treatment and promising future directions. Current treatment options in oncology 2023, 24, 1870–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruder, S.; Martinez, J.; Palmer, J.; Arham, A.B.; Tagawa, S.T. Antibody-drug conjugates in urothelial carcinoma: Current status and future. Current opinion in urology 2025, 35, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasudevan, S.O.; Behl, B.; Rathinam, V.A. Pyroptosis-induced inflammation and tissue damage. Seminars in immunology 2023, 69, 101781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Wang, X.; Deng, Y.; Li, S.; Xu, X.; Qin, Y.; Peng, L. Pyroptosis provides new strategies for the treatment of cancer. J Cancer 2023, 14, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.; Gu, W.; Wang, X.; Xia, L.; He, Y.; Dong, F.; Yang, B.; Yao, X. Distant metastasis without regional progression in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: Case report and pooled analysis of literature. World journal of surgical oncology 2022, 20, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meeks, J.J.; Al-Ahmadie, H.; Faltas, B.M.; Taylor, J.A., 3rd; Flaig, T.W.; DeGraff, D.J.; Christensen, E.; Woolbright, B.L.; McConkey, D.J.; Dyrskjøt, L. Genomic heterogeneity in bladder cancer: Challenges and possible solutions to improve outcomes. Nature reviews. Urology 2020, 17, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, C.P.; Parker, J.M.; Schaap, D.M.; Wakefield, M.R.; Fang, Y. From bench to bladder: The rise in immune checkpoint inhibition in the treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.R.; Railkar, R.; Sanford, T.; Crooks, D.R.; Eckhaus, M.A.; Haines, D.; Choyke, P.L.; Kobayashi, H.; Agarwal, P.K. Targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (egfr) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (her2) expressing bladder cancer using combination photoimmunotherapy (pit). Scientific reports 2019, 9, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).