Submitted:

28 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.1.1. Fertilized Egg Acquisition and Incubation

2.1.2. Larval Rearing and Grow-Out

2.2. Sampling and Observation

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Embryonic Development

3.1.1. Cleavage Stage

3.1.2. Blastula Stage

3.1.3. Gastrula Stage

3.1.4. Neurula Stage

3.1.5. Organogenesis Stage

3.1.6. Hatching Stage

3.2. Larvae Characteristics

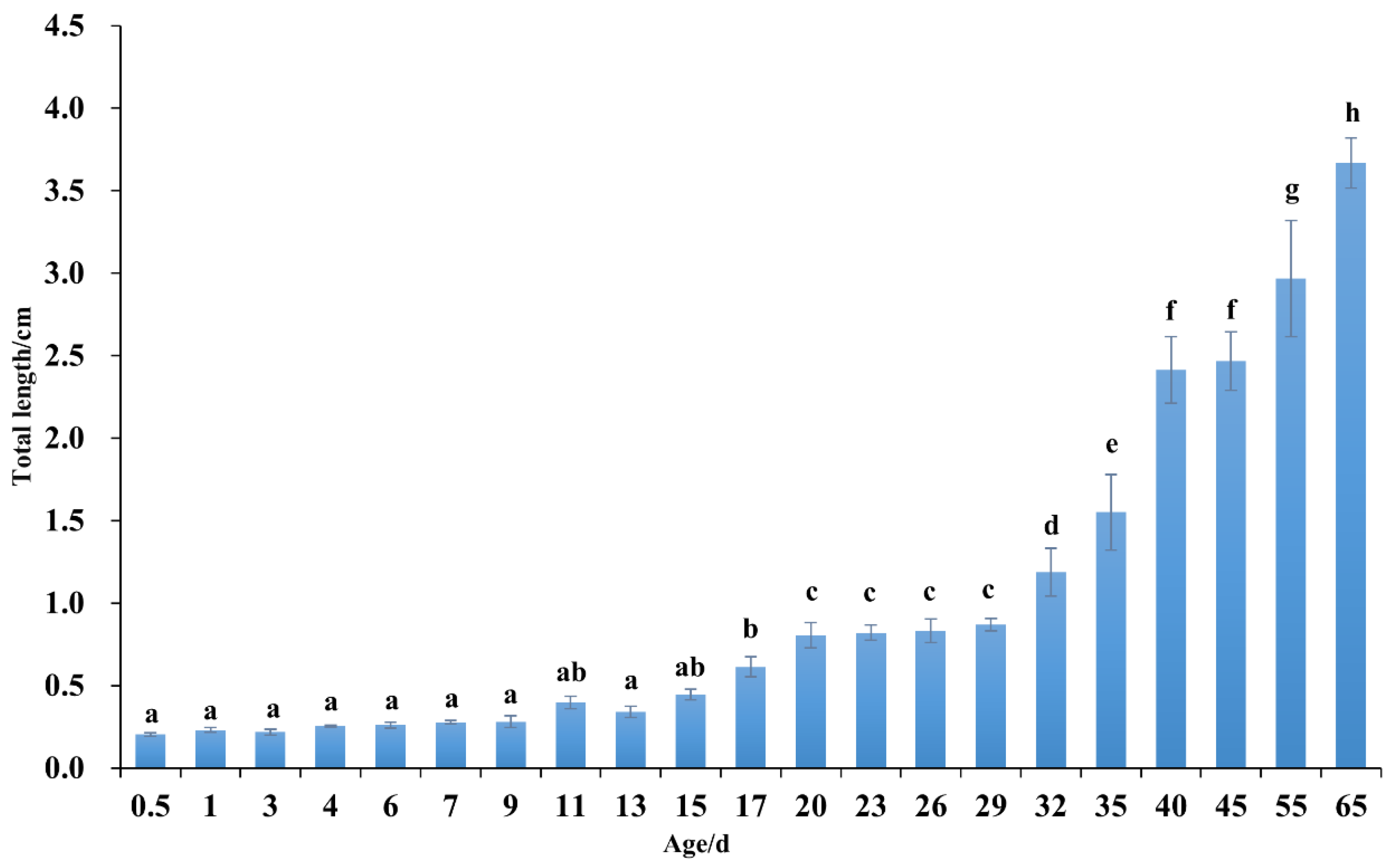

3.3. Observations on Larval Feed Transition and Growth and Development

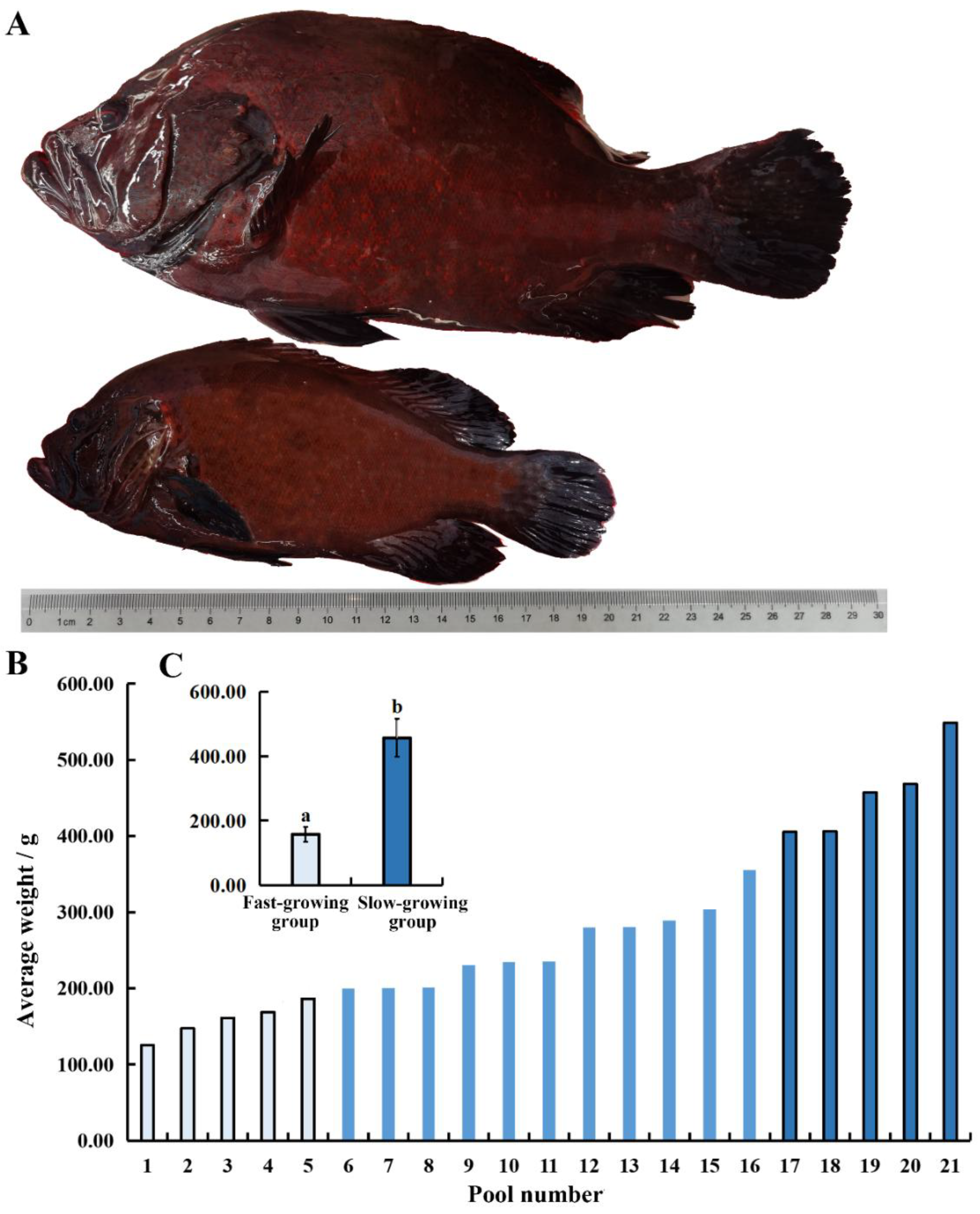

3.4. Evaluating Growth Performance

4. Discussion

4.1. Embryonic Development

4.2. Growth Performance Evaluation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- SUO X, YAN X, TAN B, et al. Lipid Metabolism Disorders of Hybrid Grouper (♀Epinephelus Fuscointestinestatus × ♂E. Lanceolatu) Induced by High-Lipid Diet. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2022, 9: 990193.

- MORAVEC F, JUSTINE J-L. New Records of Species of Philometra (nematoda: Philometridae) from Marine Fishes off New Caledonia, Including P. Cephalopholidis Sp. N. from Cephalopholis Sonnerati (Serranidae). Parasitology Research, 2015, 114: 3223-3228. [CrossRef]

- LU S, LIU Y, LI M, et al. Gap-free Telomere-to-telomere Haplotype Assembly of the Tomato Hind (Cephalopholis Sonnerati). Scientific data, 2024, 11: 1268. [CrossRef]

- XIE Z, WANG D, JIANG S, et al. Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly and Transcriptome Comparison Analysis of Cephalopholis Sonnerati and Its Related Grouper Species. Biology, 2022, 11: 1053. [CrossRef]

- FANG F, GONG Z, GUO C, et al. Establishment of an Ovarian Cell Line from Tomato Grouper (cephalopholis Sonnerati) and Its Transcriptome Response to ISKNV Infection. Fish & shellfish immunology, 2025, 162: 110304. [CrossRef]

- MOHAN P, ANIL M K, GOPALAKRISHNAN A, et al. Unraveling the Spawning and Reproductive Patterns of Tomato Hind Grouper, Cephalopholis Sonnerati (valenciennes, 1828) from South Kerala Waters. Journal of Fish Biology, 2024, 105: 186-200. [CrossRef]

- DALPATHADU K R, HAPUTHANTRI S S K. Sustainability Status of the Fishery for Cephalopholis Sonnerati (tomato Hind) in Sri Lankan Waters: A Length-Based Assessment of Survival and Management Needs. Thalassas, 2024, 41: 1-13.

- OJANGUREN A, BRANA F. Thermal Dependence of Embryonic Growth and Development in Brown Trout. Journal of Fish Biology, 2003, 62: 580-90. [CrossRef]

- FUI, OTHMAN N, SHAPAWI R, et al. Natural Spawning, Embryonic and Larval Development of F2 Hybrid Grouper, Tiger Grouper Epinephelus Fuscoguttatus × Giant Grouper E. Lanceolatus. International Aquatic Research, 2018, 10: 391-402.

- LING Z, WENMING W, JINLIANG L, et al. Studies on Embryonic Development,Morphological Development and Feed Changeover of Epinephelus lanceolatus Larva. Chinese agricultural science bulletin, 2010, 26: 293-302.

- YONG-BO W, GUO-HUA C, BIN L, et al. Artificially induced spawning and embryonic development observation of the Plectropomus leopardus Lacépède. Marine Sciences, 2009, 33: 21-6.

- TINGTING Z, CHAO C, ZHAOHONG S, et al. Effects of Temperature on the Embryonic Development and Larval Activity of Epinephelus Moara. Marine Fisheries Research, 2016, 37: 28-33.

- HUANHUAN Y, YANLU L, CHAO C, et al. The Effects of Temperature on the Embryonic Development and the Larval Activity of F1 Epinephelus Moara (♀)×E. Septemfasciatus (♂). Marine Fisheries Research, 2014, 35: 109-114.

- WANG X, TIAN Y, CHEN S, et al. A Comparative Study of the Skeletal Development of Epinephelus Fuscoguttatus (♀) and E. Tukula (♂) Hybrid Progeny and E. Fuscoguttatus. Aquaculture research, 2023, 2023: 5740050.

- LIU Y, WANG L, LI Z, et al. DNA Methylation and Subgenome Dominance Reveal the Role of Lipid Metabolism in Jinhu Grouper Heterosis. International journal of molecular sciences, 2024, 25: 9740.

- YONGSHENG T, ZHANGFAN C, HUIMIN D, et al. The Family Line Establishment of the Hybrid Epinephelus Moara (♀) ×E. Lanceolatus (♂) by Using Cryopreserved Sperm and the Related Genetic Effect Analysis. Journal of Fisheries of China, 2017, 41: 1817-28.

- CHEN S, TIAN Y, LI Z, et al. Heterosis in Growth and Low Temperature Tolerance in Jinhu Grouper (Epinephelus Fuscoguttatus ♀ × Epinephelus Tukula ♂). Aquaculture, 2023, 562: 738751.

- ZHOU Q, GUO X, HUANG Y, et al. De Novo Sequencing and Chromosomal-Scale Genome Assembly of Leopard Coral Grouper, Plectropomus Leopardus. Molecular ecology resources, 2020, 20: 1403-13.

- HAINING W, XIAODONG J, XUGAN W, et al. Evaluation of culture and immunity performance of the second-year-old early-maturing and late-maturing strains of the fourth selective generation during the juvenile culture of Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Journal of Fisheries of China, 2020, 44: 816-26.

- ZHANG H, LI R, ZENG Y, et al. Novel Screening of Molecular Markers Reveals Genetic Basis for Heterosis in Hybrids from Red Crucian Carp and White Crucian Carp. Aquaculture, 2025, 599: 742098. [CrossRef]

| Embryonic developmental stage | Detailed developmental stage |

Primary characteristics |

hAF |

| Fertilized egg | Fertilized egg | Spherical, with 1 oil globule | 00:00 |

| Cleavage stage | Placenta formation period | Placenta appears as a cap-like protuberance | 00:24 |

| 2-cell stage | 1st cleavage, forming 2 equivalent cells | 00:44 | |

| 4-cell stage | 2nd cleavage, forming 4 equivalent cells | 01:08 | |

| 8-cell stage | 3rd cleavage, forming 8 equivalent cells | 01:31 | |

| 16-cell stage | 4th cleavage, forming 16 cells | 01:40 | |

| 32-cell stage | 5th cleavage, forming 32 cells | 01:55 | |

| 64 cell stage | 6th cleavage, forming 64 cells of unequal size and irregular arrangement | 02:13 | |

| Multicellular stage | Continued division, increasing cell count | 02:43 | |

| Morula stage | Cells accumulate in multiple layers, appearing round, resembling a mulberry | 03:16 | |

| Blastula stage | High blastula | The blastoderm is high and concentrated, appearing like a high hat in lateral view | 03:53 |

| Low blastoderm | The blastoderm becomes lower, cells are preparing to envelop the vegetal pole | 05:13 | |

| Gastrula stage | Early gastrulation | The blastoderm covers 1/3 of the yolk, and the embryonic shield is visible laterally | 06:33 |

| Mid gastrulation | The blastoderm covers 1/2 of the yolk | 07:43 | |

| Late gastrulation | The germ layers enclose 3/4 of the yolk, embryonic shield becomes elongated, and the embryo is forming | 08:43 | |

| Neurula stage | Embryo formation stage | Embryo formation, distinct outline | 09:03 |

| Blastopore closure stage | Epiboly, blastopore completely closed | 09:40 | |

| Organogenesis stage | Optic vesicle formation stage | A pair of optic vesicles appears in the embryonic head | 11:29 |

| Somite formation stage | Somites appear in the middle of the embryo | 12:21 | |

| Otic vesicle formation stage | A pair of optic vesicles appear posterior to the optic vesicles in the head | 13:27 | |

| Brain vesicle formation stage | Brain vesicles appear between the two optic vesicles | 14:44 | |

| Heart formation stage | The heart forms ventrally, with a clear outline | 16:11 | |

| Tail bud stage | The caudal part of the embryo begins to separate from the yolk sac | 19:17 | |

| Lens formation stage | Lens appears in the embryo’s eyes | 19:59 | |

| Heartbeat stage | Heart begins to beat faintly, then gradually stabilizes | 20:41 | |

| Hatching stage | Pre-hatching stage | Embryo twitches violently | 21:54 |

| Hatching period | Head first out of membrane | 22:31 | |

| Newly hatched larvae | Larvae hatch out of membrane | 22:55 |

| Species | Incubation Water Temperature(℃) | Hatching Time(Hours) | Degree-Hours |

| sonnerati | 24.8 | 22.92 | 568.42 |

| E. lanceolatus | 29.0 | 18.50 | 536.50 |

| E. fuscoguttatus | 27.3 | 22.00 | 600.60 |

| leopardus | 30.6 | 16.53 | 505.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).