Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

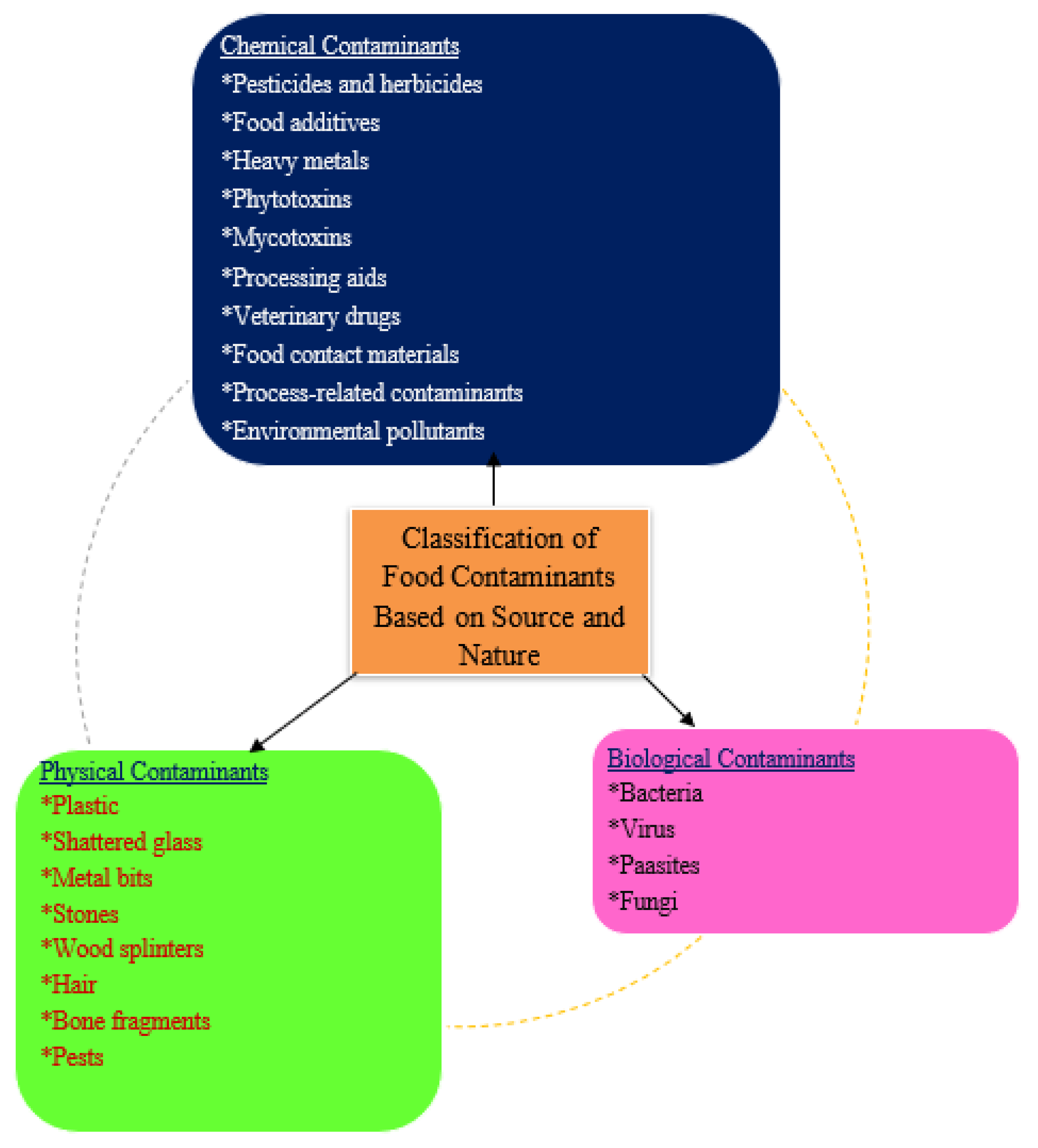

3. Classification of Food Contaminants Based on Source and Nature

3.1. Chemical Contaminants

3.2. Biological Contaminants

3.3. Physical Contaminants

4. Emerging Contaminants

5. Mechanisms of Toxicity

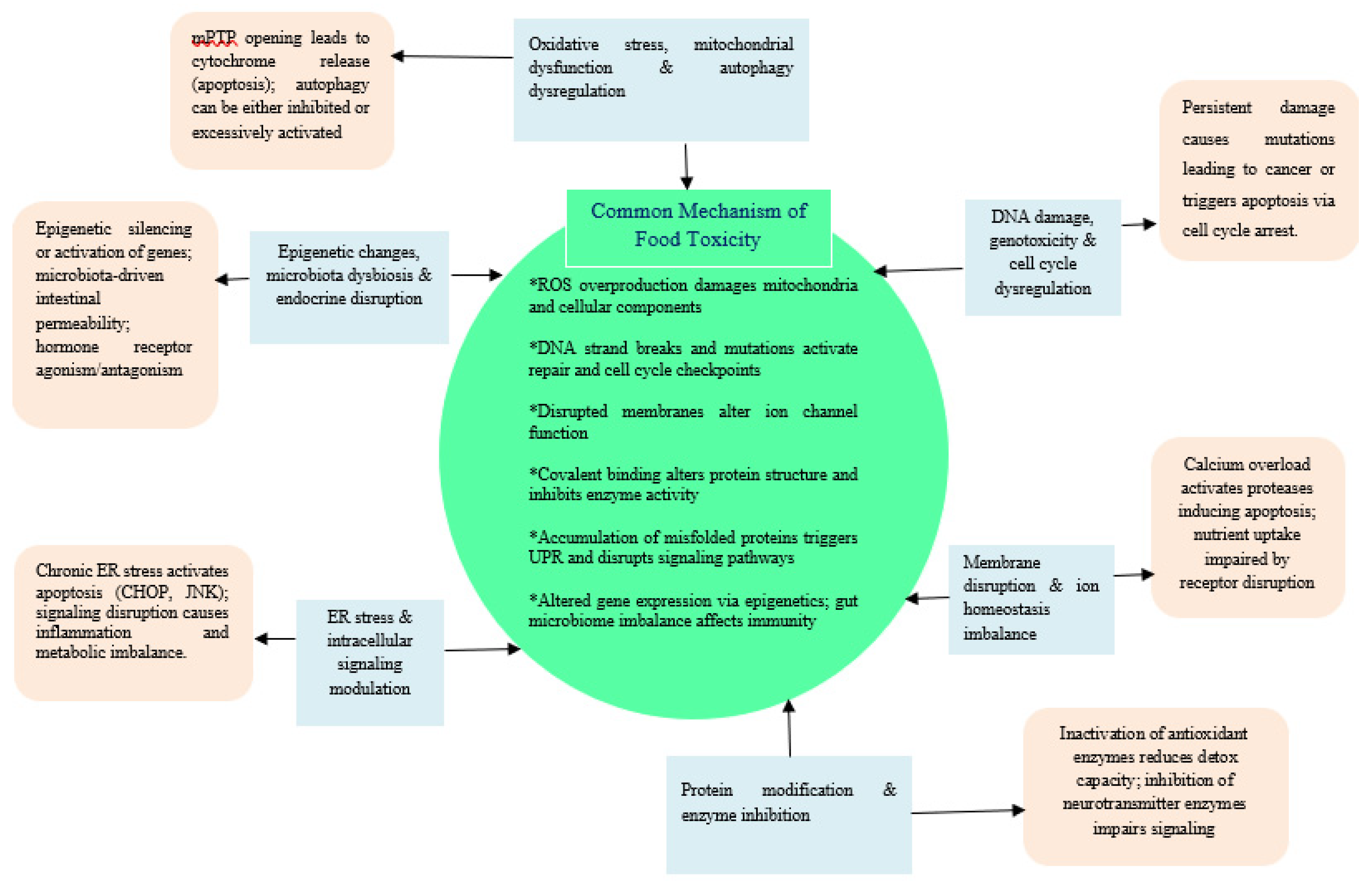

5.1. Molecular Mechanisms

5.2. Cellular Mechanisms

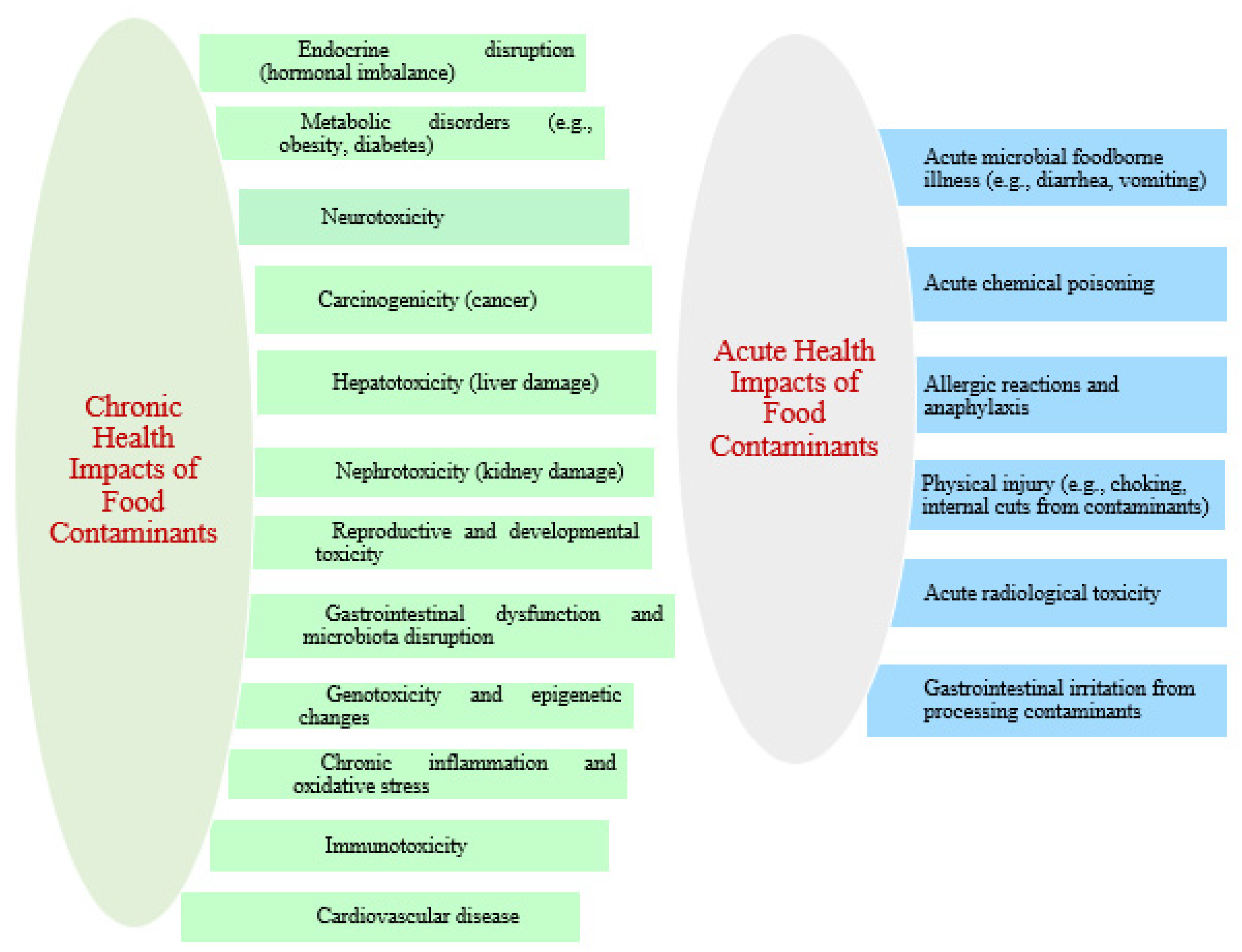

6. Health Risks from Food Contaminants

6.1. Chronic Health Impacts

6.2. Acute Health Impacts

7. Mitigation Strategies and Policy or Control Measures

7.1. Mitigation Strategies of Chemical Food Contaminants

7.2. Policy and Control Strategies

7.3. Mitigation Strategies for Biological Food Contaminants

7.4. Policy and Control Measures (Biological Contaminants)

7.5. Mitigation Strategies of Physical Contaminants

7.6. Policy and Control Measures (Physical Contaminants)

8. Limitations

9. Future Directions

10. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement: Gudisa B

References

- Altaf Hussain M. Food Contamination: Major Challenges of the Future. Foods 2016, 5, 21. [CrossRef]

- Codex Alimentarius Commission (1995). General Standard for Contaminants and Toxins in Food and Feed (CXS 193-1995). FAO/WHO. Available at: http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/codex-texts/dbs/standards/en/.

- World Health Organization (2024). Food Safety. WHO. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/food-safety.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (2024). Food Safety and Quality. FAO. Available at: http://www.fao.org/food-safety/en/.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2024). Mycotoxins in Food. FDA. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/food/chemicals/mycotoxins-food.

- European Food Safety Authority (2024). CONTAM Panel on Mycotoxins. EFSA. Available at: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/mycotoxins.

- de la Cruz García C, Moragas G S, Nordqvist D, et al. (2023). Food contact materials. In: Food Saf. Manag. pp. 385–402.

- Sharma S, Mishra A, Shukla K, et al. (2020). Food contamination: its stages and associated illness. Int. J. Pharm. Chem. Biol. Sci., 10(4).

- Mahunu G K, Osei-Kwarteng M, Ogwu M C, et al. (2024). Safe food handling techniques to prevent microbial contamination. In: Food Saf. Qual. Glob. South, Springer, pp. 427–461.

- Agnihotri A, Aruoma O I (2020). Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease: a nutritional toxicology perspective of the impact of oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, nutrigenomics and environmental chemicals. J. Am. Coll. Nutr., 39(1), 16–27. [CrossRef]

- Ali S S, Al-Tohamy R, Koutra E, et al. (2021). Nanobiotechnological advancements in agriculture and food industry: applications, nanotoxicity, and future perspectives. Sci. Total Environ., 792, 148359. [CrossRef]

- Urban-Chmiel, R.; Osek, J.; Wieczorek, K. Methods of Controlling Microbial Contamination of Food. Pathogens 2025, 14, 492. [CrossRef]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Lead exposure-Level 3 risk. Seattle: University of Washington; 2024 (https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/diseases-injuries-risks/factsheets/2021-lead-exposure-level-3-risk).

- Gibb H, Devleesschauwer B, Bolger PM, et al. World Health Organization estimates of the global and regional disease burden of four foodborne chemical toxins, 2010: a data synthesis. F1000Res. 2015 Dec 3;4:1393. [CrossRef]

- Lebelo K, Malebo N, Mochane M J, et al. (2021). Chemical contamination pathways and food safety implications along various stages of food production: a review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 18(11), 5795. [CrossRef]

- Teschke R (2022). Aluminum, arsenic, beryllium, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, copper, iron, lead, mercury, molybdenum, nickel, platinum, thallium, titanium, vanadium, and zinc: molecular aspects in experimental liver injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 23(20), 12213. [CrossRef]

- Mdeni N L, Adeniji A O, Okoh A I, et al. (2022). Analytical evaluation of carbamate and organophosphate pesticides in human and environmental matrices: a review. Molecules, 27(3), 618. [CrossRef]

- Chen H, Singh H, Bhardwaj N, et al. (2022). An exploration on the toxicity mechanisms of phytotoxins and their potential utilities. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol., 52(3), 395–435. [CrossRef]

- Bachheti A, Sharma A, Bachheti R K, et al. (2020). Plant allelochemicals and their various applications. In: Co-Evolut. Second. Metab., pp. 441–465. [CrossRef]

- Hellberg R S, Chu E (2016). Effects of climate change on the persistence and dispersal of foodborne bacterial pathogens in the outdoor environment: a review. Crit. Rev. Microbiol., 42(4), 548–572. [CrossRef]

- Vinay G M, Pathiam S, Kumar D, et al. (2025). Food additives and processing aids used in bread-making: an overview. J. Sci. Res. Rep., 31(1), 19–36. [CrossRef]

- Morley P S, Apley M D, Besser T E, et al. (2005). Antimicrobial drug use in veterinary medicine. J. Vet. Intern. Med., 19(4), 617–629. [CrossRef]

- Caneschi A, Bardhi A, Barbarossa A, et al. (2023). The use of antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance in veterinary medicine, a complex phenomenon: a narrative review. Antibiotics, 12(3), 487. [CrossRef]

- Geueke B, Muncke J (2018). Substances of very high concern in food contact materials: migration and regulatory background. Packag. Technol. Sci., 31(12), 757–769. [CrossRef]

- Sheth A (2023). Thermal processing and food-related. In: Essent. Pharmatoxicol. Drug Res., 1, 343.

- Stadler D, Berthiller F, Suman M, et al. (2020). Novel analytical methods to study the fate of mycotoxins during thermal food processing. Anal. Bioanal. Chem., 412, 9–16. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar A B, Naseem S, Yasar A, et al. (2021). Persistent organic pollutants (POPs): sources, types, impacts, and their remediation. Environ. Pollut. Remediat., pp. 213–246. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Z.; Singh, V.P. The Relative Impact of Toxic Heavy Metals (THMs) (Arsenic (As), Cadmium (Cd), Chromium (Cr)(VI), Mercury (Hg), and Lead (Pb)) on the Total Environment: An Overview. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K.; Lee, S.S.; Zhang, M.; et al. Heavy Metals in Food Crops: Health Risks, Fate, Mechanisms, and Management. Environ. Int. 2019, 125, 365–385. [CrossRef]

- Available: https://www.fda.gov/food/environmental-contaminants-food/lead-food-and-foodwares, January 06/2025.

- Available: https://www.fda.gov/food/alerts-advisories-safety-information/fda-issues-warning-about-imported-cookware-may-leach-lead-august-2025.

- Available: https://www.fda.gov/food/environmental-contaminants-food/mercury-food, January 17, 2025.

- Flannery BM, Dolan LC, Hoffman-Pennesi D, et al. U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s interim reference levels for dietary lead exposure in children and women of childbearing age. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2020 Feb;110:104516. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www2.bgs.ac.uk/groundwater/health/arsenic/Bangladesh/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Available online: https://www2.bgs.ac.uk/groundwater/downloads/bangladesh/reports/Vol1Summary.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Edmunds WM, Ahmed KM, Whitehead PG. A review of arsenic and its impacts in groundwater of the Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna delta, Bangladesh. Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts. 2015;17(6):1032-46. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www2.bgs.ac.uk/ groundwater/downloads/bangladesh/reports/Vol2MainBook.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Mahajan, M.; Gupta, P.K.; Singh, A.; et al. A comprehensive study on aquatic chemistry, health risk and remediation techniques of cadmium in groundwater. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 818, 151784. [CrossRef]

- The Flint Water Crisis: What’s Really Going On? Available online: https://www.acs.org/education/chemmatters/past-issues/ 2016-2017/december-2016/flint-water-crisis (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Basic Information about Lead in Drinking Water. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/ basic-information-about-lead-drinking-water (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Mititelu, M.; Neacs, u, S.M.; Busnatu, S, S.; et al. Assessing Heavy Metal Contamination in Food: Implications for Human Health and Environmental Safety. Toxics 2025, 13, 333. [CrossRef]

- Alum E A, Urom S M, Ben C M (2016). Microbiological contamination of food: mechanisms and prevention. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res., 5(3), 65–78.

- Garvey M (2019). Food pollution: a comprehensive review of chemical and biological sources of food contamination and impact on human health. Nutrire, 44(1), 1. [CrossRef]

- Anukwonke C C, Tambe E B, Nwafor D C, et al. (2022). Climate change and interconnected risks to sustainable development. In: Clim. Change Soc. Sci.: Constr. Crit. Engagem., pp. 71–86.

- Awuchi C G, Ondari E N, Ogbonna C U, et al. (2021). Mycotoxins affecting animals, foods, humans, and plants: occurrence, toxicities, and prevention. Foods, 10(6), 1279. [CrossRef]

- Abdolshahi A, Yancheshmeh B S (2020). Food contamination. In: Mycotoxins Food Saf., 5 June.

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)|European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). The European Union One Health 2023 Zoonoses report. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e9106.

- EFSA and ECDC (European Food Safety Authority and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control). The European Union One Health 2022 zoonoses report. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e8442.

- Asuming-Bediako, N.; Kunadu, A.P.H.; Abraham, S.; et al. Campylobacter at the human–food interface: The African perspective. Pathogens 2019, 8, 87. [CrossRef]

- Koluman, B.U.; Koluman, A. Vero-Toxigenic Escherichia coli (VTEC): To sum up all we know. J. Gastroenterol. Res. 2017, 1, 14–23.

- Scallan, E.; Hoekstra, B.M.; Angulo, F.J.; et al. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—Major pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 7–15. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Gooneratne, R.; Hussain, M.A. Listeria monocytogenes in fresh produce: Outbreaks, prevalence and contamination levels. Foods 2017, 6, 21. [CrossRef]

- Yenew C, Mekonen S, Ambelu A, Yeshiwas AG. Mitigation of Fungal Contamination in Vegetables: Key Factors From a Study in Debre Tabor, Ethiopia. Food Science & Nutrition. 2025 Jul;13(7):e70412. [CrossRef]

- Alamri, M. S., Qasem, A. A., Mohamed, A. A., et al. (2021). Food packaging’s materials: A food safety perspective. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 28(8), 4490–4499. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed S F, Mofijur M, Nuzhat S, et al. (2021). Recent developments in physical, biological, chemical, and hybrid treatment techniques for removing emerging contaminants from wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater., 416, 125912. [CrossRef]

- Bujang, A., Ain, N., Sarah, S., & Nurfadzliyana, N. (2020). An overview of potential hazards and control measures of food delivery service activities. Advances in Transportation and Logistics Research, 3, 892–898.

- Cavalheiro, C. P., da Silva, M. C. A., Leite, J. S. F., et al. (2020). Physical hazards in meat products: Consumers’ complaints found on a Brazilian website. Food Control, 108, 106892. [CrossRef]

- Singh, P. K., Singh, R. P., Singh, P., et al. (2019). Food hazards: Physical, chemical, and biological. Academic Press.

- Blom W M, Michelsen-Huisman A D, van Os-Medendorp H, et al. (2018). Accidental food allergy reactions: products and undeclared ingredients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol., 142(3), 865–875. [CrossRef]

- Esteban P, Catarina T F, Conrado C, et al. (2017). Allergen management as a key issue in food safety. In: Food Saf. Prot., pp. 195–241.

- Bodin L, Menetrier F (2021). Treatment of radiological contamination: a review. J. Radiol. Prot., 41(4), S427. [CrossRef]

- Rajkhowa S, Sarma J, Das A R (2021). Radiological contaminants in water: pollution, health risk, and treatment. In: Contam. Water, pp. 217–236. [CrossRef]

- Eze CG, Okeke ES, Nwankwo CE, et al. Emerging contaminants in food matrices: An overview of the occurrence, pathways, impacts and detection techniques of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Toxicology Reports. 2024 Jun 1;12:436-47. [CrossRef]

- B. Ruffle, U. Vedagiri, D. Bogdan, M. et al. Perfluoroalkyl Substances in U.S. market basket fish and shellfish, Environ. Res. 190 (2020) 109932. [CrossRef]

- S. Genualdi, W. Young, L. Dejager, T. Begley, Method development and validation of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances in foods from FDA’s total diet study program, J. Agric. Food Chem. 69 (2021) 5599–5606. [CrossRef]

- Alengebawy A, Abdelkhalek ST, Qureshi SR, et al (2021). Heavy metals and pesticides toxicity in agricultural soil and plants: Ecological risks and human health implications. Toxics. 9(3):42. [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Armendáriz, C.; Alejandro-Vega, S.; Paz-Montelongo, S.; et al. Microplastics as Emerging Food Contaminants: A Challenge for Food Safety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1174. [CrossRef]

- Karri, V.; Kumar, V.; Ramos, D.; Oliveira, E. Comparative In Vitro Toxicity Evaluation of Heavy Metals (Lead, Cadmium, Arsenic, and Methylmercury) on HT-22 Hippocampal Cell Line. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2018, 184, 226–239. [CrossRef]

- Rather I A, Koh W Y, Paek W K, et al. (2017). The sources of chemical contaminants in food and their health implications. Front. Pharmacol., 8, 830. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava R, Singh Y, White JC, et al. Mitigating toxic metals contamination in foods: bridging knowledge gaps for addressing food safety. Trends in food science & technology. 2024 Nov 1;153:104725. [CrossRef]

- Onyeaka H, Ghosh S, Obileke K, et al. Preventing chemical contaminants in food: Challenges and prospects for safe and sustainable food production. Food Control. 2024 Jan 1;155:110040. [CrossRef]

- Moe B, Peng H, Lu X, et al (2016). Comparative cytotoxicity of fourteen trivalent and pentavalent arsenic species determined using real-time cell sensing. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 49, 113–124. [CrossRef]

- Rana S V, Wakode S, Sharma A, et al. (2020). Effect of environmental toxicants on neuronal functions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int., 27, 44906–44921. [CrossRef]

- Kordas K, Ravenscroft J, Cao Y, et al. (2018). Lead exposure in low- and middle-income countries: perspectives and lessons on patterns, injustices, economics, and politics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 15(11), 2351. [CrossRef]

- Sterckeman T, & Thomine S (2020). Mechanisms of cadmium accumulation in plants. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences, 39(4), 322–359. [CrossRef]

- Tang Z, & Zhao F-J (2021). The roles of membrane transporters in arsenic uptake, translocation and detoxification in plants. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 51(21), 2449–2484. [CrossRef]

- Xu Z-R, Cai M-L, Chen S-H, et al (2021). High-affinity sulfate transporter Sultr1; 2 is a major transporter for Cr (VI) uptake in plants. Environmental Science & Technology, 55(3), 1576–1584. [CrossRef]

- Kubier A, Wilkin RT, & Pichler T (2019). Cadmium in soils and groundwater: A review. Applied Geochemistry, 108, Article 104388. [CrossRef]

- Collin S, Baskar A, Geevarghese DM, Ali MNVS, et al (2022). Bioaccumulation of lead (Pb) and its effects in plants: A review. Journal of Hazardous Materials Letters, 3, Article 100064. [CrossRef]

- Kuraeiad S, & Kotepui M (2021). Blood lead level and renal impairment among adults: A metaanalysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18 (8), 4174. [CrossRef]

- Kumar A, Kumar A, Mms C-P, et al (2020). Lead toxicity: Health hazards, influence on food chain, and sustainable remediation approaches. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2179. [CrossRef]

- Pawar B, Dhamne SA, Pingale PL, et al. Thermal processing and food-related toxicants. InEssentials of Pharmatoxicology in Drug Research 2023 Jan 1 (pp. 343-368). Academic Press.

- Li L, Zhao J. Association of urinary and blood lead concentrations with all-cause mortality in US adults with chronic kidney disease: a prospective cohort study. Scientific Reports. 2024 Oct 5;14(1):23230. [CrossRef]

- Singh B, Pavithran N, Rajput R (2023). Effects of food processing on nutrients. Curr J Appl Sci Technol. 42(46):34-49.

- Sekoai PT, Mhlongo SI, Ezeokoli OT (2019). Abatement of microbial contaminants in ethanol fermentation: review. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol.18(4):795-821.

- Asuku A O, Ayinla M T, Ajibare A J, et al. (2024). Heavy metals and emerging contaminants in foods associated with neurotoxicity. In: Emerg. Contam. Food Prod., CRC Press, pp. 236–250.

- Bihn EA, Reiners S (2018). Good agricultural and manufacturing practices in vegetable production. In: Handb Veg Process. 109-34.

- Harshitha T, Dasalkar AH, Parinitha A, et al (2024). Food additives and preservatives. In: Front Food Biotechnol.249-82.

- Meena V, Dotaniya M L, Saha J K, et al. (2020). Impact of lead contamination on agroecosystem and human health. In: Lead Plants Environ., pp. 67–82.

- Omotayo O P, Omotayo A O, Mwanza M, et al. (2019). Prevalence of mycotoxins and their consequences on human health. Toxicol. Res., 35, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Elmassry M M, Zayed A, Farag M A (2022). Gut homeostasis and microbiota under attack: impact of the different types of food contaminants on gut health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr., 62(3), 738–763. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2020). Codex Alimentarius: Food Standards, Guidelines and Codes of Practice. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int.

- Matta G, & Gjyli L (2016). Mercury, lead and arsenic: Impact on environment and human health. Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 9(2), 718–725.

- Danyo EK, Ivantsova MN, Selezneva IS (2024). Ionizing radiation effects on microorganisms in food industry. Foods Raw Mater. 12(1):1-2.

- Amir S, Shah S T, Mamoulakis C, et al. (2021). Endocrine disruptors acting on estrogen and androgen pathways cause reproductive disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 18(4), 1464. [CrossRef]

- Elumalai A, Shanmugasundaram S (2024). Emerging biological control agents in food safety. In: Non-Thermal Technol Food Ind. 290-9.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2021). International Food Safety Authorities Network (INFOSAN). Rome: FAO. Available from: https://www.fao.org.

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) (2019). EFSA J. European Union. Available from: https://www.efsa.europa.eu.

- United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (2016). Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA). Washington, DC: FDA. Available from: https://www.fda.gov.

- Gurikar C, Shivaprasad D P, Sabillón L, et al. (2023). Impact of mycotoxins and their metabolites associated with food grains. Grain Oil Sci. Technol., 6(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Jukes DJ (2014). Regulatory frameworks and monitoring of food safety. In: Jukes DJ, editor. Food Saf Manag: Pract Guide Food Ind. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing. p. 1-29.

- Igbal Z, Iqbal M, Shabbir G, et al (2018). Surveillance of foodborne contaminants: approaches and challenges in developing countries. J Food Sci. 83(5):1340-1348. [CrossRef]

- Pesticide Action Network (2020). Pesticide regulation and surveillance in agriculture. PAN International. Available from: https://www.paninternational.org.

- Shigaki T (2020). Health effects of environmental pollutants. In: Gut Remediat Environ Pollut:1-29.

- Zadeh HH, Fallah Z (2021). Pesticide residues and their impacts on public health: a review of global data and regulations. Public Health Nutr. 24(4):670-683.

- Chichester C, Tracey E (2017). Advances in food safety technologies and practices. Food Control. 73:267-275.

| Types | Examples | Key Characteristics | Cause / Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical contaminants | |||

| Pesticides and herbicides [17] | Organophosphates, carbamates, pyrethroids, and glyphosate. | Synthetic compounds used to control pests; persistent | Agricultural application, contaminated soil or water |

| Food additives [25] | MSG, nitrates, and nitrites | Substances added to enhance taste, preserve, or improve appearance | Intentional addition during processing; overuse can be harmful |

| Heavy metals [10] | Lead, mercury, chromium, nickel, and cadmium | Non-biodegradable elements; accumulate in environment | Natural mineral content, industrial pollution, mining, combustion, fertilizers |

| Phytotoxins [41] | Cyanogenic glycosides, ricin, saponins, and tannins. | Naturally occurring plant toxins | Certain plant species, improper processing or storage |

| Mycotoxins [18,19] | Aflatoxins, ochratoxins, fumonisins, deoxynivalenol, zearalenone, and ergot alkaloids | Fungal secondary metabolites | Mold growth in crops during harvest, storage, or transport |

| Processing aids [20] | Amylase, solvents like hexane, catalysts such as nickel, and antifoaming agents | Used in manufacturing or processing | Residual chemicals from food processing steps |

| Veterinary drugs [21,22] | Antibiotics like tetracyclines, hormones like estradiol, and antiparasitics like ivermectin | Drugs administered to livestock | Residues in meat, milk, or eggs from treated animals |

| Food contact materials [23] | BPA, phthalates, mineral oil hydrocarbons, and PFAS | Chemicals migrating from packaging or equipment | Leaching from plastic containers, cans, coatings, and non-stick surfaces |

| Process-related contaminants [24,25] | Acrylamide, PAHs, chloropropanols, furan, and nitrosamines | Formed during heating, smoking, or processing | Thermal treatment, frying, smoking, roasting, chemical reactions in processed food |

| Environmental pollutants [26] | Dioxins, PCBs, and POPs like DDT and HCB | Persistent organic pollutants | Industrial discharge, waste incineration, pesticide use, environmental contamination |

| Biological contaminants | |||

| Bacteria [42,43,49,50,51,52] | Salmonella, E. coli, and Listeria monocytogenes | Single-celled microorganisms; may produce toxins | Contaminated water, raw food, poor hygiene, inadequate cooking |

| Virus [43] | Norovirus and Hepatitis | Require living hosts to replicate | Contaminated food or water, infected handlers |

| Paasites [42,43] | Giardia lamblia, Toxoplasma gondii, and Trichinella spiralis | Eukaryotic organisms infecting humans via food | Contaminated water, undercooked meat, unwashed produce |

| Fungi [45,46,53] | Molds and yeasts | Eukaryotic microorganisms | Contaminated crops, poor storage conditions |

| Physical contaminants [55,56,57,58] | |||

| Plastic, shattered glass, metal bits, stones, wood splinters, hair, bone fragments, and pests. | Foreign objects accidentally introduced | Improper handling, packaging, machinery, or storage | |

| Mechanism | Molecular Pathway or Target | Representative Contaminants | Health Consequences | Target Body System/Organ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction [28,69,70] | ROS overproduction; mitochondrial DNA damage; mPTP opening; ATP depletion | Heavy metals, pesticides, mycotoxins | Lipid peroxidation, cell death, organ dysfunction | Liver, brain, kidney, cardiovascular system |

| DNA Damage and Genotoxicity [71,72] | DNA adducts, strand breaks, chromosomal aberrations; p53, ATM, ATR activation | Aflatoxins, heavy metals, pesticides | Mutagenesis, carcinogenesis | Liver, bone marrow, GI tract |

| Cell Cycle Dysregulation [69] | G1/S or G2/M arrest; cyclin/CDK dysregulation | Various genotoxicants | Uncontrolled proliferation or apoptosis | All proliferative tissues (e.g., liver, colon) |

| Membrane Integrity and Ion Homeostasis [69,71] | Disruption of lipid bilayers and ion channels (e.g., Ca²⁺ channels) | Cadmium, lead | Altered signaling, apoptosis, calcium overload | Neurons, cardiac muscle, renal tubules |

| Protein Modification and Enzyme Inhibition [73] | Covalent adducts with protein residues; enzyme inactivation (e.g., glutathione peroxidase, acetylcholinesterase) | Heavy metals, pesticides | Impaired detoxification, neurotransmission, cellular dysfunction | CNS, liver, erythrocytes |

| Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Stress [74] | UPR activation via CHOP and JNK pathways; misfolded protein accumulation | Chemical toxicants | Apoptosis, protein misfolding diseases | Pancreas, liver, neurons |

| Autophagy Dysregulation [78,81] | Inhibited or excessive autophagic flux; damaged organelle accumulation | Various contaminants | Oxidative stress, autophagic cell death | Neurons, hepatocytes, renal epithelium |

| Epigenetic Modifications [77] | DNA methylation, histone modification, microRNA regulation | EDCs, heavy metals | Gene silencing, carcinogenesis, heritable toxic effects | Germ cells, embryonic tissues, liver |

| Intracellular Signaling Modulation [70,79,80] | MAPK, NF-κB, PI3K/Akt pathway disruption | Multiple contaminants | Inflammation, apoptosis, metabolic imbalance | Immune system, endocrine organs, brain |

| Microbiota Dysbiosis [75] | Shift in microbial taxa; leaky gut; impaired xenobiotic metabolism | Various foodborne contaminants | Inflammation, immune dysregulation, metabolic disorders | Gastrointestinal tract, immune system |

| Endocrine Disruption [7,76,81] | Hormone receptor agonism/antagonism; altered hormone biosynthesis | EDCs (e.g., BPA, phthalates) | Reproductive, metabolic, and developmental disorders | Reproductive organs, thyroid, pancreas, brain |

| Contaminant Type | Chronic Health Impacts | Acute Health Impacts | Key Stakeholders / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Metals (lead, mercury, cadmium, arsenic) [10,28,29] | Neurodevelopmental deficits, cognitive impairment, kidney and liver damage, cardiovascular disorders, reproductive toxicity | Gastrointestinal irritation, neurological symptoms (tremors, ataxia, paresthesia), renal impairment, multi-organ failure in severe cases | Regulators (FDA, EFSA, WHO), farmers, food processors, water suppliers, public health authorities |

| Mycotoxins (aflatoxins, ochratoxin A, fumonisins) [19,20] | Hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, immunosuppression, carcinogenicity | Acute mycotoxicosis: liver damage, hemorrhagic manifestations, immunosuppression | Grain producers, storage facilities, regulatory agencies, food safety labs |

| Pesticides (organophosphates, carbamates, pyrethroids, glyphosate) [17] | Neurotoxicity, endocrine disruption, metabolic disorders | Cholinergic symptoms, paresthesia, dizziness, convulsions, gastrointestinal irritation | Farmers, agrochemical companies, regulatory bodies, public health organizations |

| Process-Related Contaminants (acrylamide, PAHs, nitrosamines) [24] | Carcinogenicity, liver and kidney injury, chronic inflammation | Nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, CNS effects at high doses | Food processors, packaging industry, regulatory agencies, risk assessors |

| Biological Contaminants (Salmonella, E. coli O157:H7, Campylobacter, Listeria, Norovirus, Giardia, Cryptosporidium) [51,52] | Chronic gastrointestinal disorders, post-infectious sequelae | Acute gastroenteritis: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever; severe outcomes like hemolytic uremic syndrome | Farmers, slaughterhouses, food processors, restaurants, public health authorities |

| Physical Contaminants (glass, metal shards, stones, plastics, insects) [57,58] | Rare long-term effects | Mechanical injury: oral and gastrointestinal lacerations, choking, perforation | Food manufacturers, processing plants, inspectors, packaging companies |

| Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs) (BPA, phthalates, PCBs, PFAS) [26] | Reproductive dysfunction, metabolic disorders, thyroid abnormalities | Acute effects rare; primarily chronic exposure concerns | Manufacturers of plastics and consumer products, regulatory bodies, researchers, healthcare providers |

| Microplastics and Chemical Residues [62,65] | Altered gut microbiota, impaired nutrient absorption, immune system disruption | Acute effects uncommon; primarily chronic exposure concern | Environmental agencies, food processors, water utilities, research institutions |

| Contaminant Class | Mitigation Strategy | Description | Examples of Mitigation | Key Stakeholders |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common Strategies to All Contaminants [83–131] | Good Agricultural and Manufacturing Practices (GAPs & GMPs) | Preventive measures at farm and processing level to reduce contamination risks. | Regulating pesticide use, sanitation in processing, pest control | Farmers, processors, manufacturers, regulators |

| Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) | Risk-based identification and control of contamination points in food production. | Metal detection, cooking, allergen cross-contact prevention, radiological monitoring | Food safety managers, QA teams, regulators | |

| Effective Sanitation and Hygiene | Cleaning, hygiene, and environmental decontamination to reduce biological, allergenic, chemical, physical, and radiological hazards. | Equipment cleaning, handwashing, soil/water decontamination in radiological zones | Food handlers, sanitation teams, supervisors | |

| Supplier Control and Raw Material Screening | Ensuring raw materials come from verified, approved sources to limit contaminants. | Supplier audits, pesticide residue and microbial testing | Procurement teams, suppliers, food safety labs | |

| Food Traceability and Recall Systems | Systems to quickly identify and remove contaminated products from the market. | Batch tracking, barcode systems, blockchain | Manufacturers, distributors, regulators | |

| Analytical Testing and Monitoring Programs | Routine laboratory tests for contaminants and environmental surveillance. | HPLC, GC-MS for chemicals; ELISA for allergens; PCR for pathogens; radionuclide assays | Food testing labs, regulatory agencies | |

| Education and Training of Personnel | Training workers on contamination risks and control measures. | Allergen control workshops, chemical handling training, hygiene protocols | Employers, trainers, safety officers | |

| Proper Labeling and Allergen Declarations | Accurate ingredient and allergen labeling to inform consumers and prevent exposure. | Ingredient lists, allergen warnings, origin labeling | Manufacturers, regulators, consumer groups | |

| Regulatory Compliance and International Standards | Compliance with global/national safety standards and contaminant limits. | Codex MRLs, FDA and EU contaminant limits | Regulators, import/export authorities | |

| Technological Interventions | Advanced technology use to reduce contaminants or enhance detection and traceability. | Irradiation, high-pressure processing, optical sorting, biosensors | Processors, tech providers | |

| Risk Communication and Public Awareness | Educate consumers on safe food handling and contamination risks. | Public advisories on outbreaks or radiological events | Public health agencies, media, NGOs | |

| Environmental and Source Control | Environmental-level controls to reduce contaminant entry into the food chain. | Regulating industrial discharge, runoff management, soil remediation | Environmental agencies, farmers, industries | |

| Chemical Contaminants [9,15,18,23,26,41,62,63,66,74,83,84,85,86,87] | Substitution of Hazardous Substances | Replace toxic chemicals with safer alternatives. | Use of natural preservatives instead of synthetic nitrites | Food chemists, manufacturers, regulators |

| Regulation and Withdrawal of High-risk Substances | Ban or restrict toxic pesticides, persistent organic pollutants, endocrine disruptors. | Banning DDT, restricting BPA | Regulators, agricultural authorities | |

| Setting and Enforcing Maximum | Residue Limits (MRLs) | Define safe residue levels specific to food types. | Codex MRLs for pesticides | Regulators, testing labs | |

| Processing Optimization | Modify processing to minimize harmful chemical formation. | Lower frying temperatures to reduce acrylamide | Food technologists, manufacturers | |

| Buffer Zones and Runoff Control | Prevent chemical drift and leaching in agricultural landscapes. | Buffer strips, water management practices | Farmers, environmental agencies | |

| Material Selection for Food Contact Surfaces | Use packaging that does not leach hazardous chemicals. | BPA-free plastics, phthalate-free films | Packaging manufacturers, regulators | |

| Biological Contaminants [10,21,26,28,29,45,55,58,60,62,73,78,87,88,90,97,98] | Thermal Inactivation | Heat treatments to kill pathogens. | Pasteurization of milk, cooking meat | Food processors, QA teams |

| Time-Temperature Control (Cold Chain) | Refrigeration/freezing to inhibit microbial growth. | Cold storage of seafood, frozen foods | Supply chain managers, retailers | |

| High-Pressure Processing (HPP) | Non-thermal pathogen inactivation while preserving food quality. | HPP treatment of juices, RTE meats | Food processors | |

| Biocontrol Agents and Competitive Exclusion | Use beneficial microbes to suppress pathogens. | Lactic acid bacteria in fermented foods | Microbiologists, producers | |

| Bacteriophage Application | Use specific phages targeting harmful bacteria. | Phages targeting Listeria in ready-to-eat meats | Biotech companies, food producers | |

| Parasitic Cyst Deactivation | Freezing or acidification to kill parasites. | Freezing fish to deactivate parasites | Processors, regulators | |

| Mycotoxin Reduction Strategies | Resistant crop varieties, drying, and toxin binders to reduce mycotoxins. | Grain drying <13% moisture, bentonite in animal feed | Farmers, feed manufacturers | |

| Physical Contaminants [11,19,24,44,56,74,86,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106] | Metal Detection and X-ray Inspection | Detection of metal and non-metal foreign objects. | Inline metal detectors, X-ray machines | Process engineers, QA teams |

| Optical Sorters and Sieving | Removal of stones, shells, and extraneous matter. | Optical sorting of nuts, sieving grains | Processors, equipment suppliers | |

| Magnetic Traps | Capture iron particles in liquids and powders. | Magnetic traps in flour mills | Equipment suppliers, processors | |

| Product Design Review | Avoid use of fragile materials that can break and contaminate food. | Avoiding glass thermometers | Product designers, QA teams | |

| Physical Segregation and Zoning | Dedicated zones to reduce cross-contamination with physical hazards. | Separate packaging rooms | Facility managers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).