Submitted:

28 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

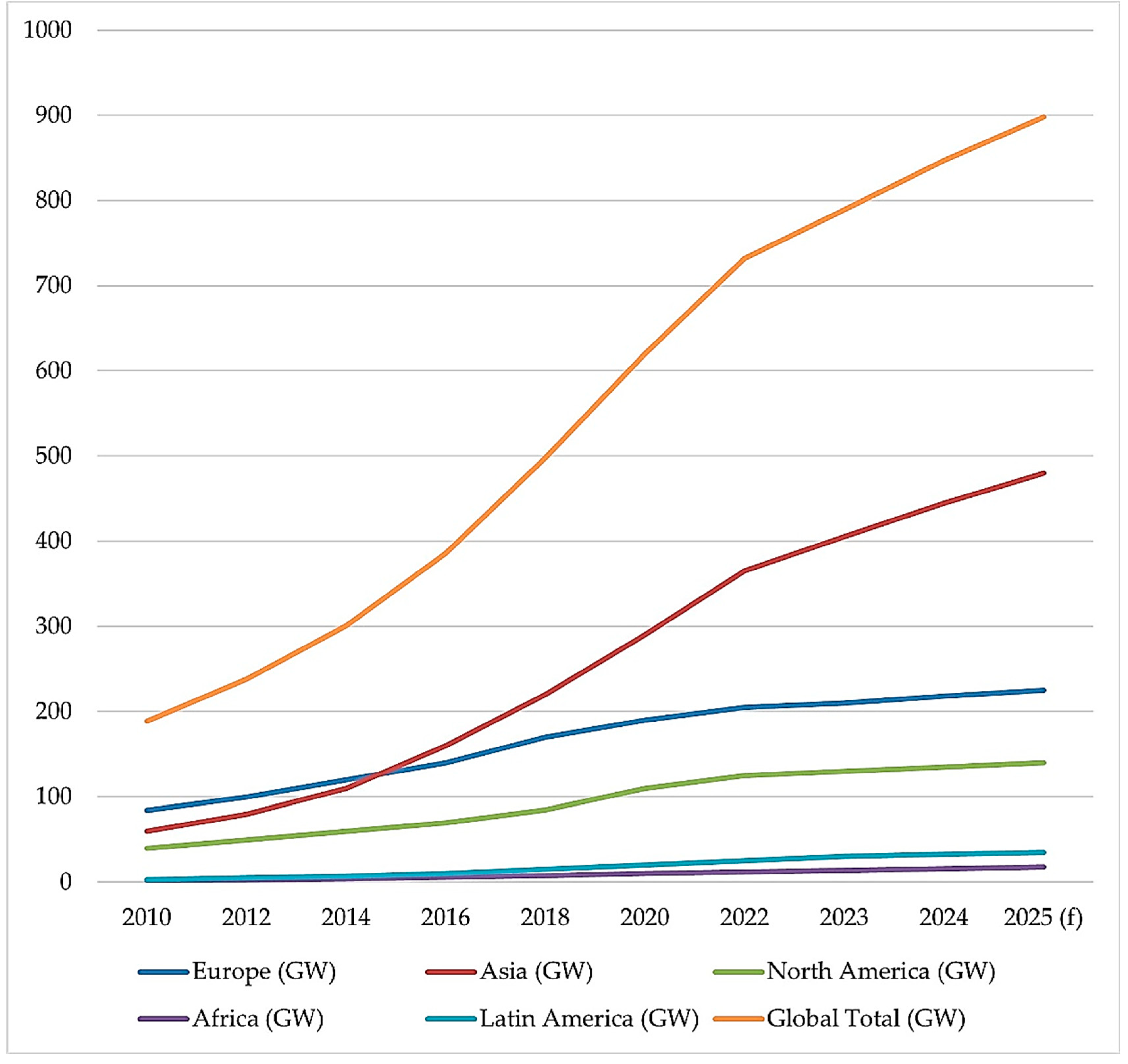

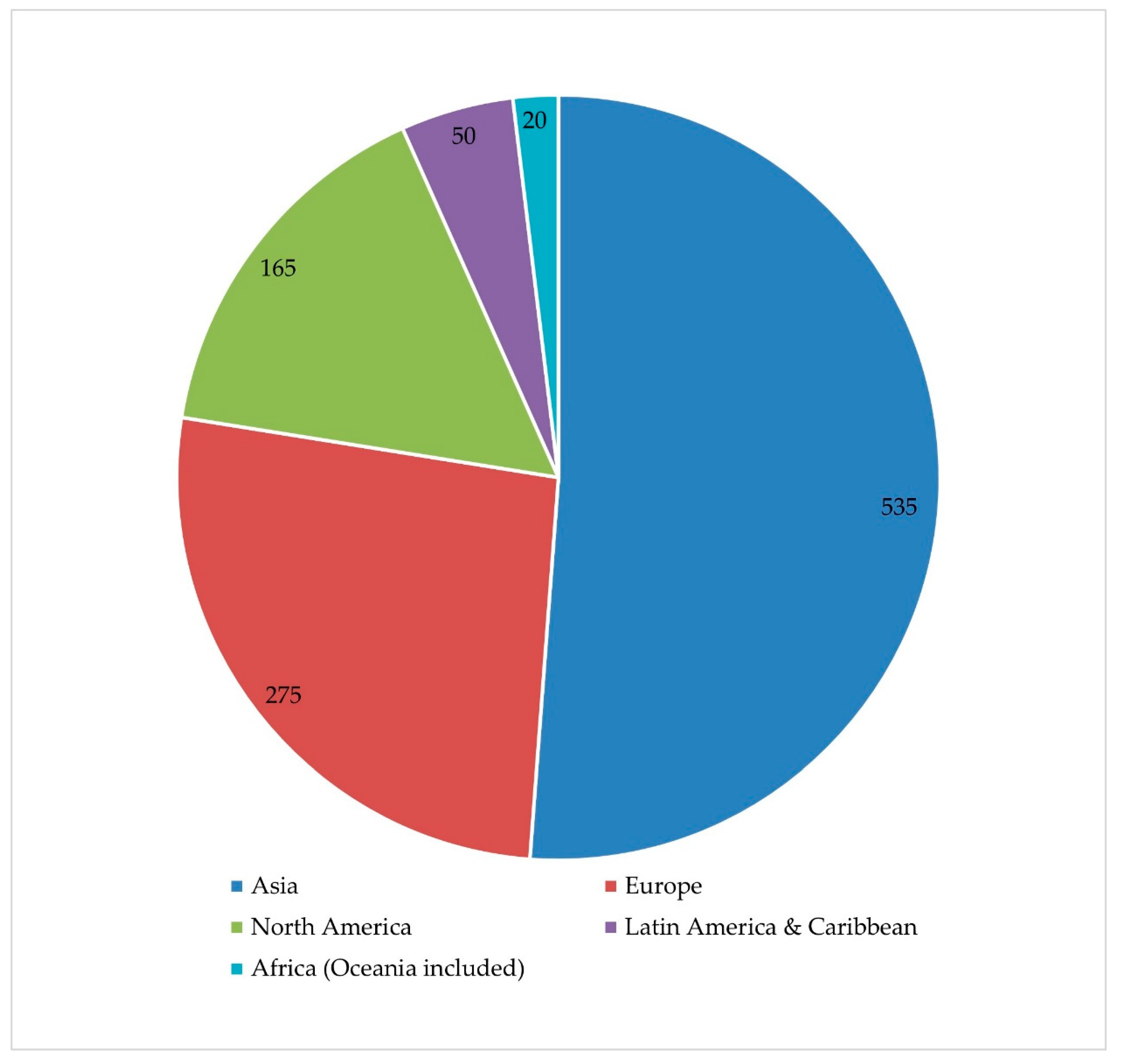

2. State of the Art in Wind Power Plant Integration

2.1. Challenges of Wind Power Plant Integration

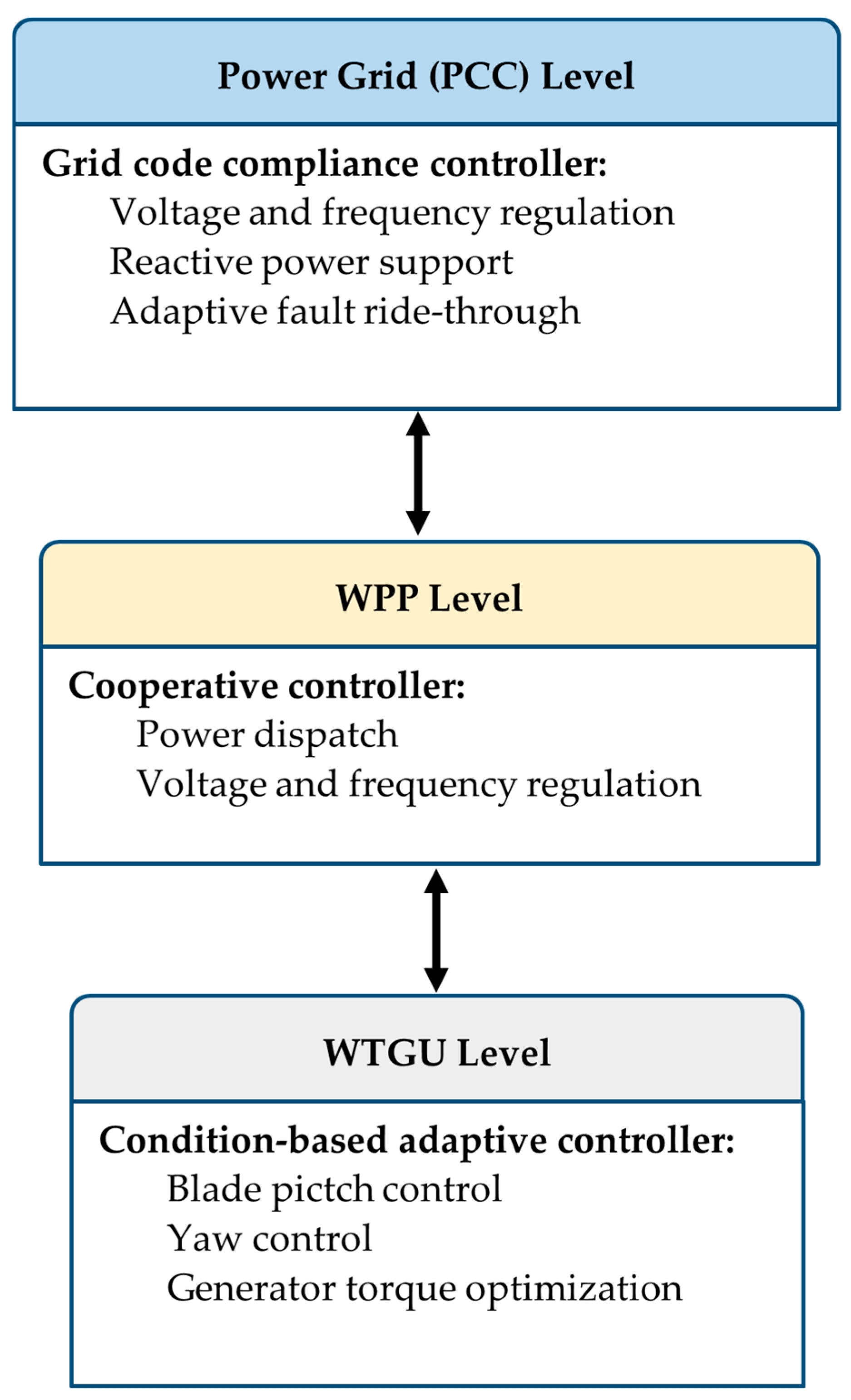

2.2. Traditional and Adaptive Control Approaches

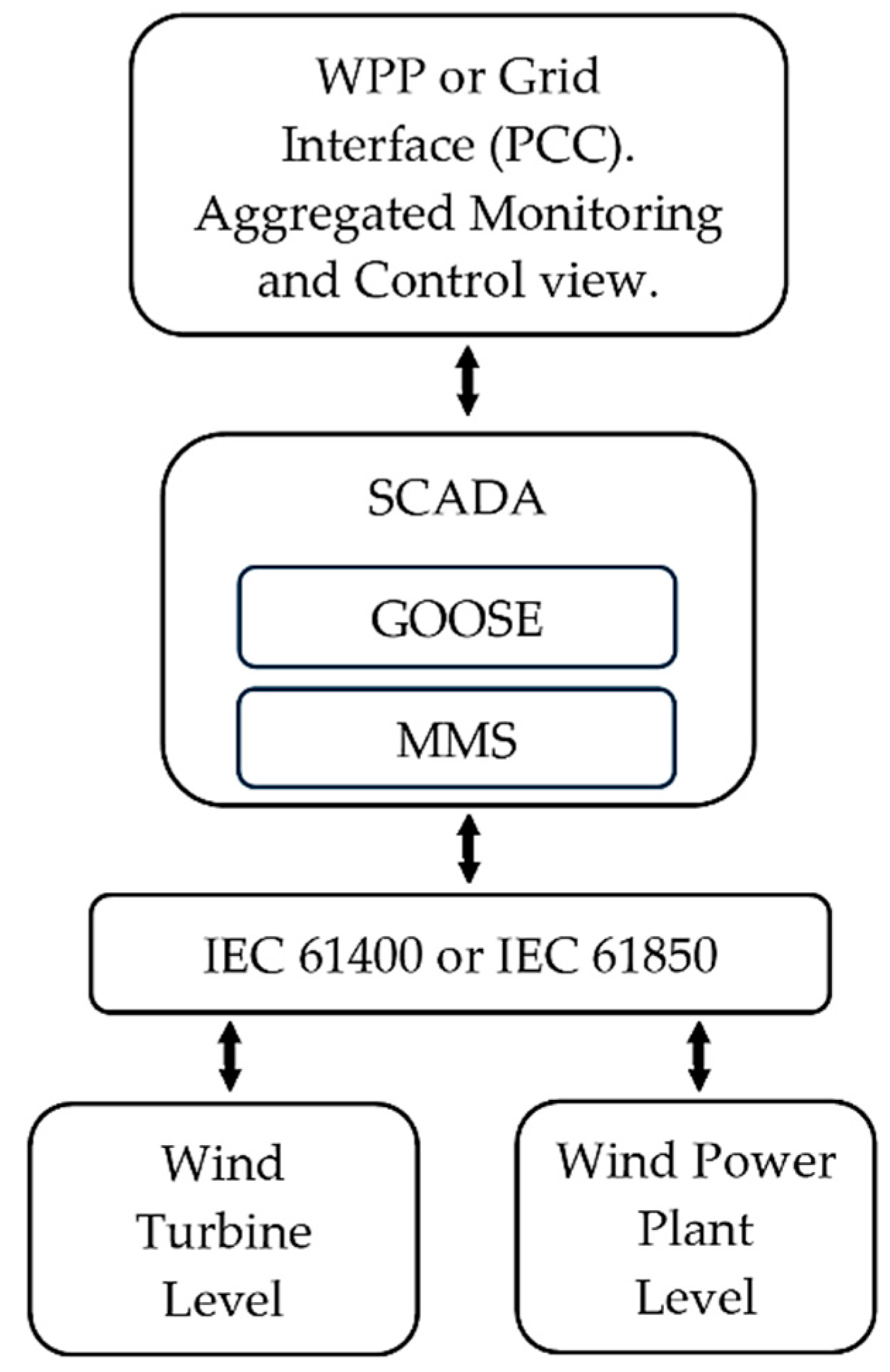

2.3. Communication and Interoperability Issues

2.4. Standards Overview

3. Adaptive Control Strategies for WPPs

3.1. Turbine-Level Adaptive Control

3.2. Plant-Level Adaptive Control

3.3. Hybrid and Storage-Assisted Adaptive Schemes

3.4. Emerging AI- and ML-Based Adaptive Methods

5. Interoperability Frameworks and Standards

5.1. Role of IEC 61850 in Renewable Integration

5.2. IEC 61400-25 and Wind-Specific Communication

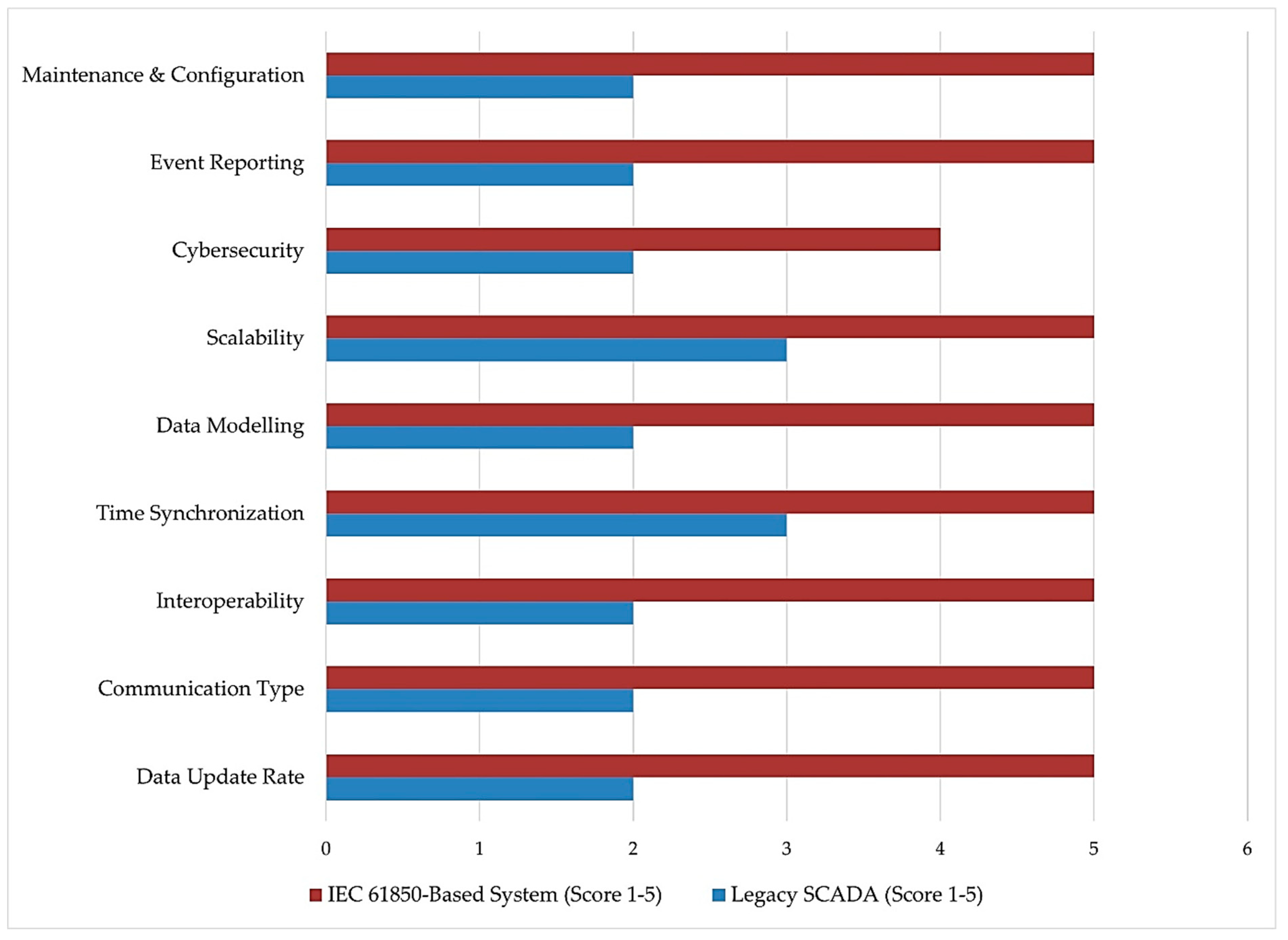

5.3. SCADA versus IEC 61850: Strengths and Limitations

5.4. Cybersecurity and Interoperability Challenges

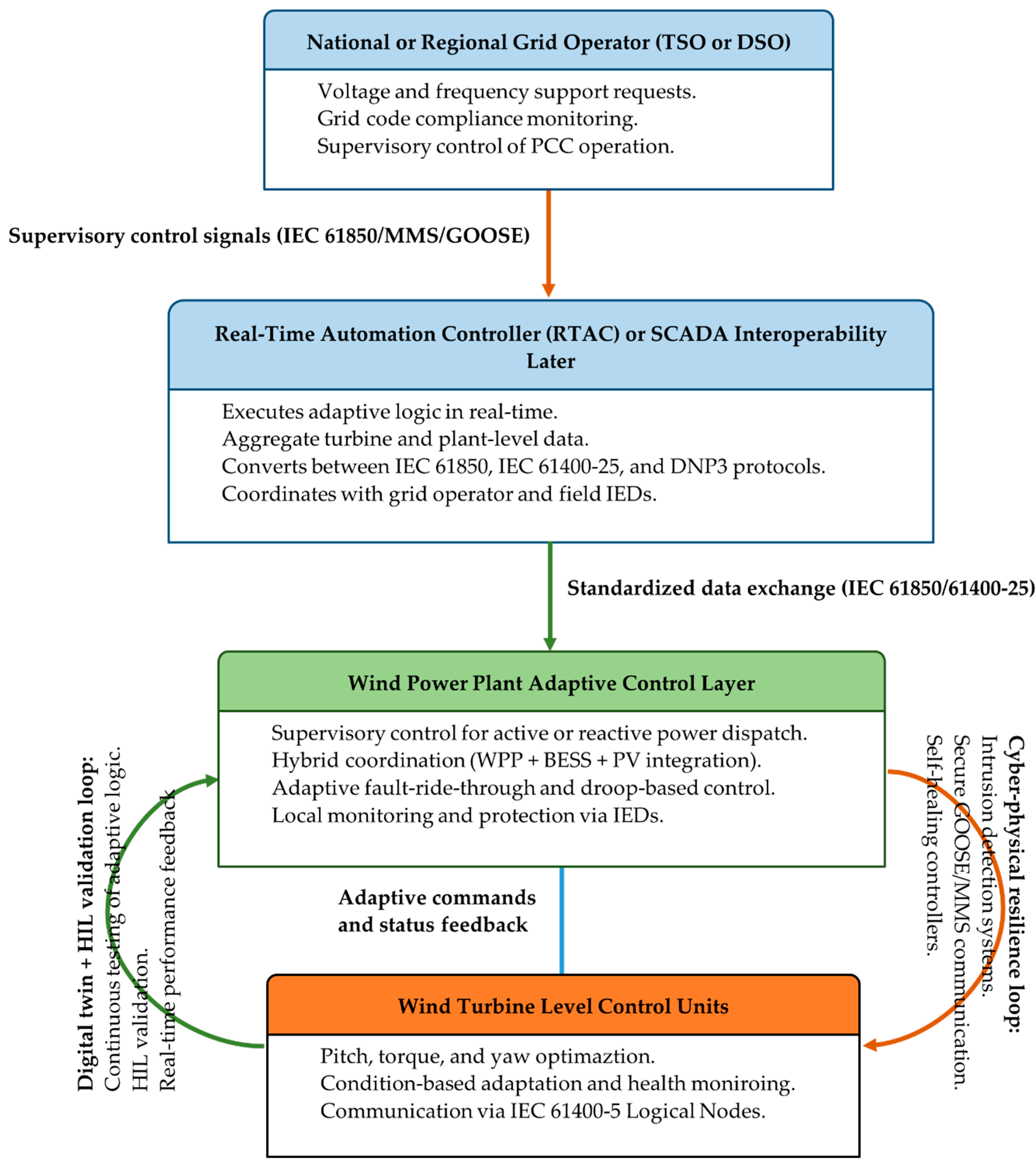

6. Real-Time Automation Controllers (RTACs) and Implementation Platforms

6.1. RTAC Applications in Microgrids and Renewable-Rich Systems

6.2. RTACs for WPP Control and Monitoring

6.3. Advantages over Traditional SCADA

- Scalability: RTACs can be deployed in small microgrids, medium-scale WPPs, or even utility-scale renewable clusters, making them versatile across system sizes.

6.4. Integration with IEC Standards

7. Validation Methods: Simulation and Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL)

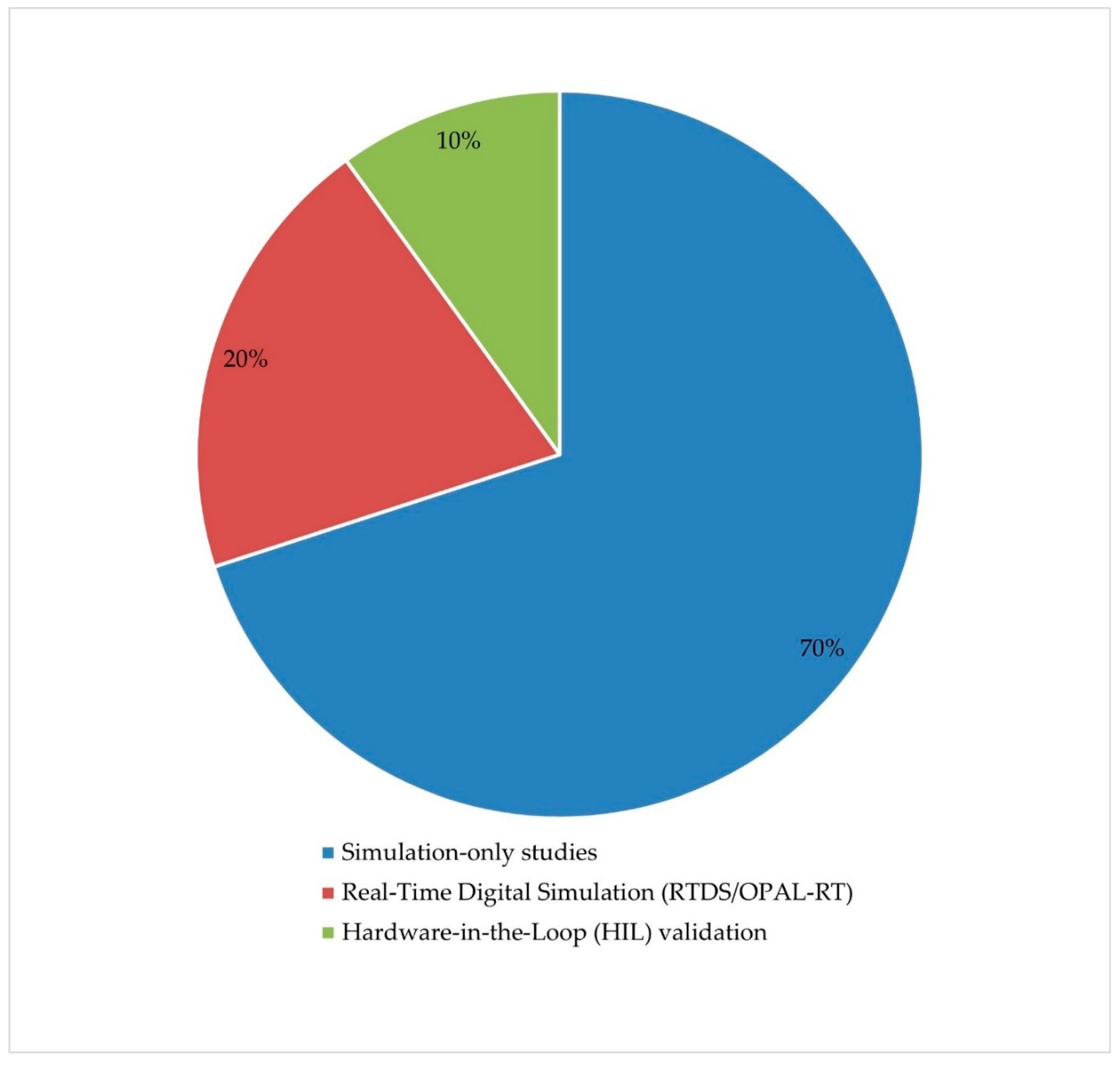

7.1. Simulation-Only Approaches and Their Limitations

7.2. Real-Time Digital Simulation Platforms

7.3. Relay and Controller Testing with HIL

7.5. Trends and Future Directions in HIL Validation

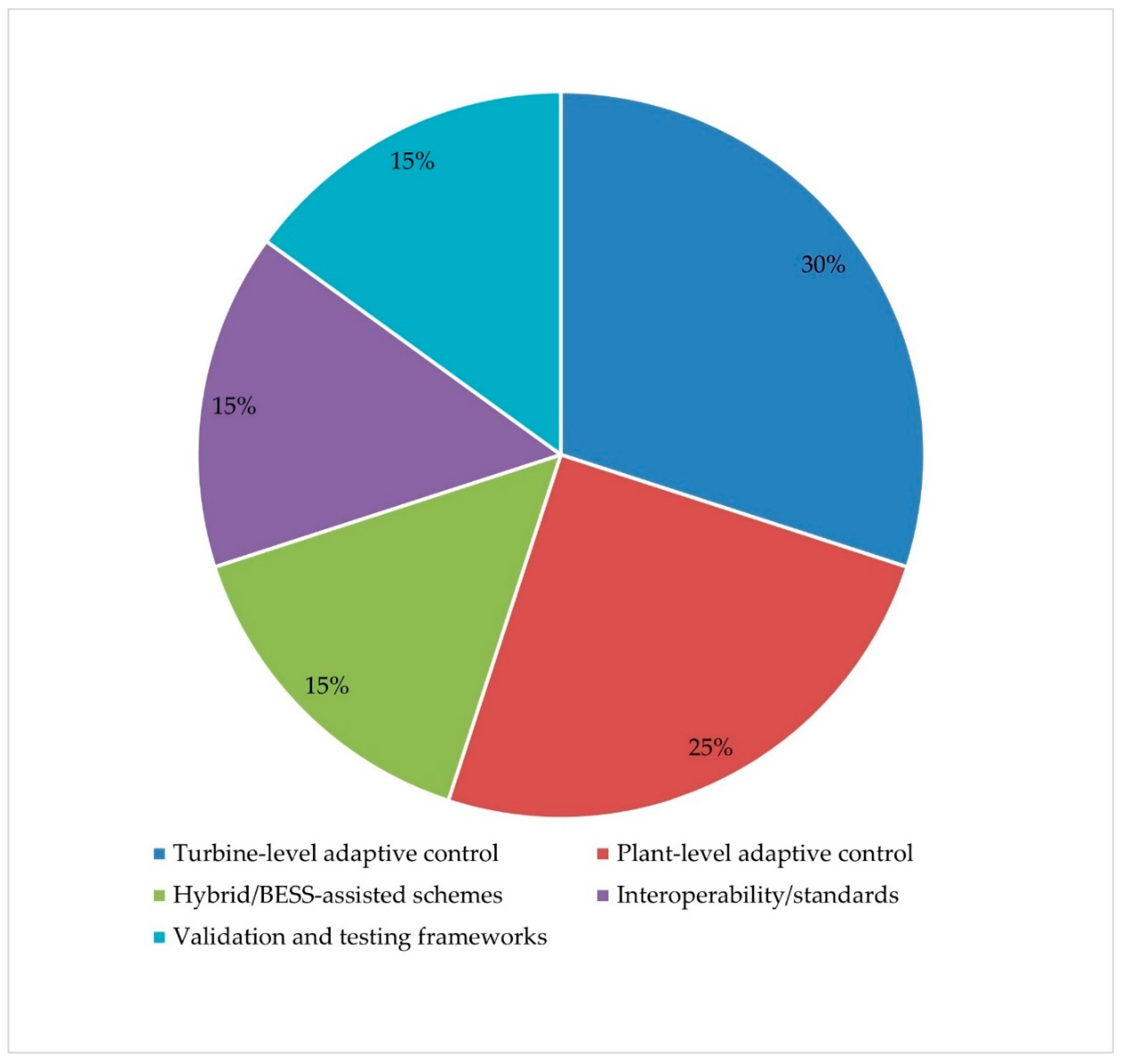

8. Comparative Analysis of Literature and Research Gaps

8.1. Comparative Insights Across Approaches

8.2. Identified Research Gaps

- Focus on local rather than system-level integration. Most adaptive control research is constrained to the turbine-level [25,26] or microgrid-scale applications [39], whereas plant-wide adaptive coordination at the PCC remains underexplored [31]. This creates a disconnect between academic advances and the needs of transmission system operators who must manage high-integration wind on bulk networks.

- Limited application of IEC standards in adaptive operation. While IEC 61850 and IEC 61400-25 are well established for monitoring and protection [17,27,28], their potential to enable real-time adaptive coordination across monitoring, operation, and protection has not been realized. As a result, communication architectures remain fragmented, and true interoperability is lacking [18,40].

- Insufficient real-time and HIL validation. Simulation-only studies remain the norm [20]–[22], with very few adaptive schemes tested under real-time or HIL conditions [23,24]. The lack of large-scale, hardware-inclusive validation undermines confidence in the deployability of these systems. Furthermore, cybersecurity, increasingly a concern in IEC 61850-enabled networks, is rarely addressed in validation studies [33,47].

8.3. Emerging Opportunities

9. Future Research Directions

9.1. Toward Holistic Adaptive Frameworks

9.2. Expanding Interoperability with IEC Standards

9.3. Cyber-Physical Resilience

- Designing intrusion detection systems tailored for renewable-rich environments.

- Developing self-healing controllers capable of isolating compromised components.

- Extending HIL testbeds to simulate cyberattacks alongside electrical disturbances.

9.4. Integration of Digital Twins and HIL Platforms

9.5. AI- and Data-Driven Adaptive Methods

10. Conclusions

References

- Singh, B.K.; Coulter, J.; Sayani, M.A.G.; Sami, S.M.; Khalid, M.; Tepe, K.E. , “Survey on Communication Architectures for Wind Energy Integration with the Smart Grid,” Int. J. Environ. Stud., vol. 70, no. 5, pp. 765–776, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Energy, A.I.R. , “Renewable Capacity Statistics 2024,” 2024. [Online]. Available: www.irena.

- Council, G.W.E. , “Global Wind Report 2024,” 2024.

- Council, G.W.E. , “Global Wind Report 2025,” 2025.

- Xia, S.; Zhang, Q.; Hussain, S.T.; Hong, B.; Zou, W. , “Impacts of Integration of Wind Farms on Power System Transient Stability,” Appl. Sci., vol. 8, no. 8, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Benseddik, A.; Kouba, N.; Boudour, M.; Hasni, M.; Menaa, M. , “Wind Farm Integration Intermittency Impact on Power System Transient Stability,” Proc. 2018 3rd Int. Conf. Electr. Sci. Technol. Maghreb, Cist. 2018, pp. 1–6, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Rachdi, T.; Saoudi, Y.; Mahmoud, I.; Florin, I.; Errachdi, A. , “The Impact of Integration Wind Turbine on the Stability of the Electricity Grid,” 2022 IEEE Inf. Technol. Smart Ind. Syst. ITSIS 2022, pp. 1–6, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; et al. , “A Phase-to-Phase Protection Algorithm With the Transient Information for the Wind Power Plant Transmission Line,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, no. June, pp. 100581–100590, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Loza, B.; Minchala, L.I.; Ochoa-Correa, D.; Martinez, S. , “Grid-Friendly Integration of Wind Energy: A Review of Power Forecasting and Frequency Control Techniques,” Sustain., vol. 16, no. 21, pp. 1–22, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Pandit, D.; Bera, A.; Saket, R.K. ; Mitra, “Probabilistic Sizing of Energy Storage Systems for Reliability and Frequency Security in Wind-Rich Power Grids,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, no. September, pp. 4608–4621, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Suboh, S.M.; Sharma, R.; Tushar, W.; Ahamad, N.B. , “Enhancing Active Power Dispatchability of WTG-BESS Through Integrated Control Considering Wind Forecast Error,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, no. January, pp. 2778–2792, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mndiya, S.J.; Ratshitanga, M.; Krishnamurthy, S. , “Active Power Reserve Provision with Large-scale WES and BESS,” in 2024 IEEE PES/IAS PowerAfrica, PowerAfrica 2024, IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Dufo-López, R.; Lujano-Rojas, J.M. , “Simulation and Optimisation of Utility-Scale PV–Wind Systems with Pumped Hydro Storage,” Appl. Sci., vol. 14, no. 16, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Pettener, A.L. , “SCADA and communication networks for large scale offshore wind power systems,” IET Conf. Publ., vol. 2011, no. 579 CP, p. 11, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Chen, Z. , “Intelligent control on wind farm,” IEEE PES Innov. Smart Grid Technol. Conf. Eur. ISGT Eur., pp. 1–6, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, D.; Catterson, V.M.; Booth, C.; Cruden, A. , “Designing wind Turbine Condition Monitoring Systems Suitable for Harsh Environments,” IET Conf. Publ., vol. 2013, no. 623 CP, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, J.; Muthukrishnan, V.; McGinn, D.; Hunt, R. , “Wind Farm Protection Using an IEC 61850 Process Bus Architecture,” in 10th IET International Conference on Developments in Power System Protection (DPSP 2010), Managing the Change, Manchester, UK, 29 March–, 2010, pp. 1–5. 1 April.

- Yu, F.R.; Zhang, P.; Xiao, W.; Choudhury, P. , “Communication systems for grid integration of renewable energy resources,” IEEE Netw., vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 22–29, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Calles, J.M.; Colmenar-Santos, A.; Ontañon-Ruiz, J.; Castro-Gil, M. , “Wind Control Centres: State of the Art,” Renew. Energy, vol. 51, pp. 93–100, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Kusiak, A.; Li, W.; Song, Z. , “Dynamic control of wind turbines,” Renew. Energy, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 456–463, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Shah, O.A.; Arora, S. , “Adaptive control strategies for effective integration of solar power into smart grids using reinforcement learning,” Energy Storage Sav., vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 327–340, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.G.; van der Hoek, D.; Ferrari, R.; van Wingerden, J.W. , “Wind tunnel testing of wind turbine and wind farm control strategies for active power regulation,” J. Renew. Sustain. Energy, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 1–16, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Golestan, S.; Golmohamadi, H.; Sinha, R.; Iov, F.; Bak-Jensen, B. , “Real-Time Simulation and Hardware-in-the-Loop Testing Based on OPAL-RT ePHASORSIM: A Review of Recent Advances and a Simple Validation in EV Charging Management Systems,” Energies, vol. 17, no. 19, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, G.; Liao, Y.; Burfield, A.D. , “Hardware-in-the-Loop Testing for Protective Relays Using Real Time Digital Simulator (RTDS),” Energies, vol. 16, no. 3, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Frutuoso, T.R.L.; Castro, R.; Pereira, R.B.S.; Moutinho, A. , “Advancements in Wind Farm Control: Modelling and Multi-Objective Optimization Through Yaw-Based Wake Steering,” Energies, vol. 18, no. 9, pp. 1–29, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sierra-García, J.E.; Santos, M. , “Exploring reward strategies for wind turbine pitch control by reinforcement learning,” Appl. Sci., vol. 10, no. 21, pp. 1–23, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Tchakoua, P.; Wamkeue, R.; Ouhrouche, M.; Slaoui-Hasnaoui, F.; Tameghe, T.A.; Ekemb, G. , “Wind Turbine Condition Monitoring: State-of-the-art Review, New Trends, and Future Challenges,” Energies, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 2595–2630, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Nomandela, S.; Mnguni, M.; Raji, A. , “Busbar Differential Protection System Testing Based on Practical Considerations Using Real-Time Digital Simulator Hardware-In-the-Loop Technique,” in 2024 6th International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Control Technologies (CEECT), Shenzhen, China, : IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024, 2024, pp. 359–363. 20–22 December. [CrossRef]

- Nomandela, S. , “Evaluation of Power Grid Voltage Instability Point using System Overloading Contingency in Real-time Simulation,” in 2024 IEEE PES/IAS PowerAfrica, IEEE, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, F.; Batmani, Y.; Bevrani, H. , “Model Reference Adaptive Controller for Simultaneous Voltage and Frequency Restoration of Autonomous AC Microgrids,” J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 1194–1202, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nomandela, S.; Mnguni, M.E.S.; Raji, A.K. , “Modeling and Simulation of a Large-Scale Wind Power Plant Considering Grid Code Requirements,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 6, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, J.; Cruz, T.; Lam, C.T.; Simoes, P. , “Smart Substation Communications and Cybersecurity: A Comprehensive Survey,” IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 2456–2493, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Song, T.J.; Lee, H.; Zaboli, A. , “Automated Cybersecurity Tester for IEC61850-Based Digital Substations,” Energies, vol. 15, no. 21, pp. 1–17, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Elbez, G.; Nahrstedt, K.; Hagenmeyer, V. , “Early Attack Detection for Securing GOOSE Network Traffic,” IEEE Trans. Smart Grid, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 899–910, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; et al. , “An adaptive frequency regulation strategy with high renewable energy participating level for isolated microgrid,” Renew. Energy, vol. 212, no. March, pp. 683–698, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, B. , “Model-Free Fast Frequency Support of Wind Farms for Tracking Optimal Frequency Trajectory,” IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 2638–2650, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nomandela, S.; Mnguni, M.E.S.; Raji, A.K. , “Systematic Development and Hardware-in-the-Loop Testing of an IEC 61850 Standard-Based Monitoring and Protection System for a Modern Power Grid Point of Common Coupling,” Energies, vol. 18, no. 5281, pp. 1–47, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Czechowski, R.; Wicher, P.; Wiecha, B. , “Cyber security in communication of SCADA systems using IEC 61850,” Proc. - Int. Conf. Mod. Electr. Power Syst. MEPS 2015, pp. 1–7, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Chandraratne, C.; Ramasamy, T.N.; Logenthiran, T.; Panda, G. , “Adaptive protection for microgrid with distributed energy resources,” Electron., vol. 9, no. 11, pp. 1–14, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Melo, A.F.S.; Roldan-Fernandez, J.M.; Gonzalez-Longatt, F.; Burgos-Payan, M.; Netto, U.C. , “Novel IEC 61850-based off-site engineering and validation methodology for protection, automation, and control systems,” Electr. Power Syst. Res., vol. 232, no. January, p. 110409, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Haque, A.; Zaman, H.; Morsalin, S.; Islam, S. , “Exploring the Potential Application of IEC 61850 to Enable Energy Interconnectivity in Smart Grid Systems,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, no. April, pp. 56910–56923, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhu, D.; Zou, X.; He, C.; Hu, J.; Kang, Y. , “Adaptive Temporary Frequency Support for DFIG-Based Wind Turbines,” IEEE Trans. Energy Convers., vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 1937–1949, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Zhang, X.-P.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. , “Adaptive Droop-Based Hierarchical Optimal Control Strategy for VSC-MTDC Grids with Large-Scale Wind Farm Integration,” in IEC Power Net Zero 2024, Bermingham, UK: IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018, 2024, p. 5.

- Li, H.; Li, X.; Xiong, W.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Kou, P. , “Cooperative Voltage and Frequency Regulation with Wind Farm: A Model-Based Offline Optimal Control Approach,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 17, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Hong, Q.; Feng, Z.; Syed, M.H.; Burt, G.M.; Booth, C.D. , “Design and Implementation of a Real-Time Hardware-in-the-Loop Platform for Prototyping and Testing Digital Twins of Distributed Energy Resources,” Energies, vol. 15, no. 18, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, R.; Liu, H.; Yavari, A. , “Digital Twins for Enhancing Efficiency and Assuring Safety in Renewable Energy Systems: A Systematic Literature Review,” Energies, vol. 17, no. 11, pp. 1–34, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chandramathi, J.S.V.; Nair, M.G.; Bel, C.A. , “Cyber-Resilient Controllers for Smart Distribution Grid Control Layers,” Energies, vol. 18, no. 15, p. 3916, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Nomandela, S.; Mnguni, M.E.S.; Raji, A.K. , “A Recap of Modern Power Grid Control Systems,” 2024 7th Asia Conf. Energy Electr. Eng., pp. 17–23, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Soe, H.M.; Htet, A. , “A Comprehensive Review of SCADA-Based Wind Turbine Performance and Reliability Modeling with Machine Learning Approaches,” J. Technol. Innov. Energy, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 68–92, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Difronzo, M.; Biswas, M.M.; Milton, M.; Ginn, H.L.; Benigni, A. , “System level real-time simulation and hardware-in-the-loop testing of mmcs,” Energies, vol. 14, no. 11, pp. 1–22, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Huu, D.N. , “A novel adaptive control approach based on available headroom of the vsc-hvdc for enhancement of the ac voltage stability†,” Energies, vol. 14, no. 11, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Luna, E.; De La Cruz, J.; Vasquez, J.C. , “New Approach for Validation of a Directional Overcurrent Protection Scheme in a Ring Distribution Network with Integration of Distributed Energy Resources Using Digital Twins,” Energies, vol. 17, no. 7, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, W. , “Research on Distributed wind Power Reactive Voltage Coordinated Control Strategy Connected to Distribution Network,” 2021 4th Int. Conf. Energy, Electr. Power Eng. CEEPE 2021, pp. 529–534, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Zhang, J.; Du, K.; Zhou, T. , “A Hybrid Deep Learning and Model Predictive Control Framework for Wind Farm Frequency Regulation,” Sustain., 2025.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).