Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA)

2.2. Patient Cohort

2.3. Tissue Microarray (TMA) Construction

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

2.5. IHC Quantitation with QuPath

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

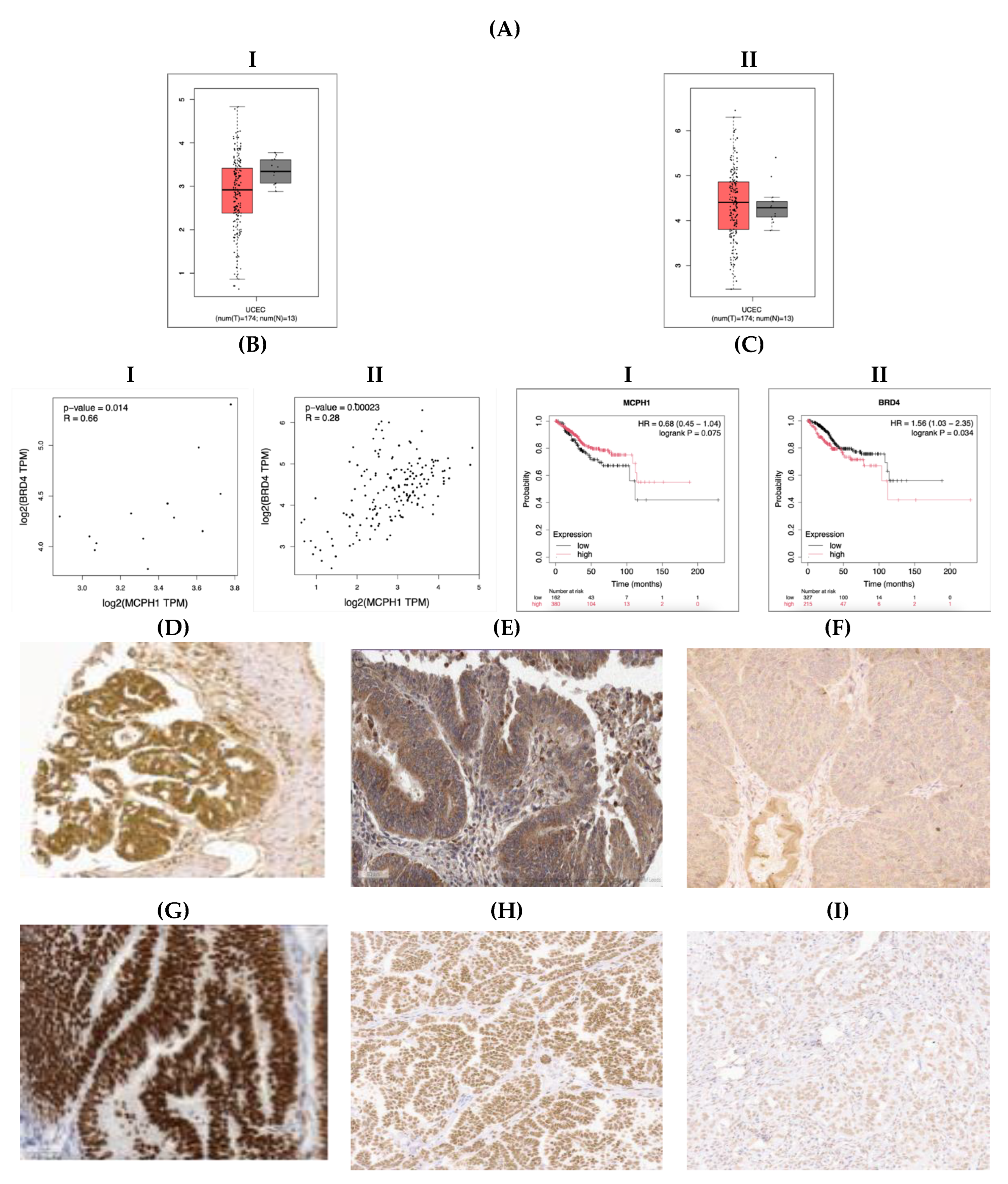

3.1. MCPH1 and BRD4 mRNA Expression in Normal Endometrium and EC Samples

3.2. MCPH1 and BRD4 Protein Expression in EC

3.3. Patient Demographic Data

3.4. Correlation of MCPH1 and BRD4 Expression with Clinicopathological Data

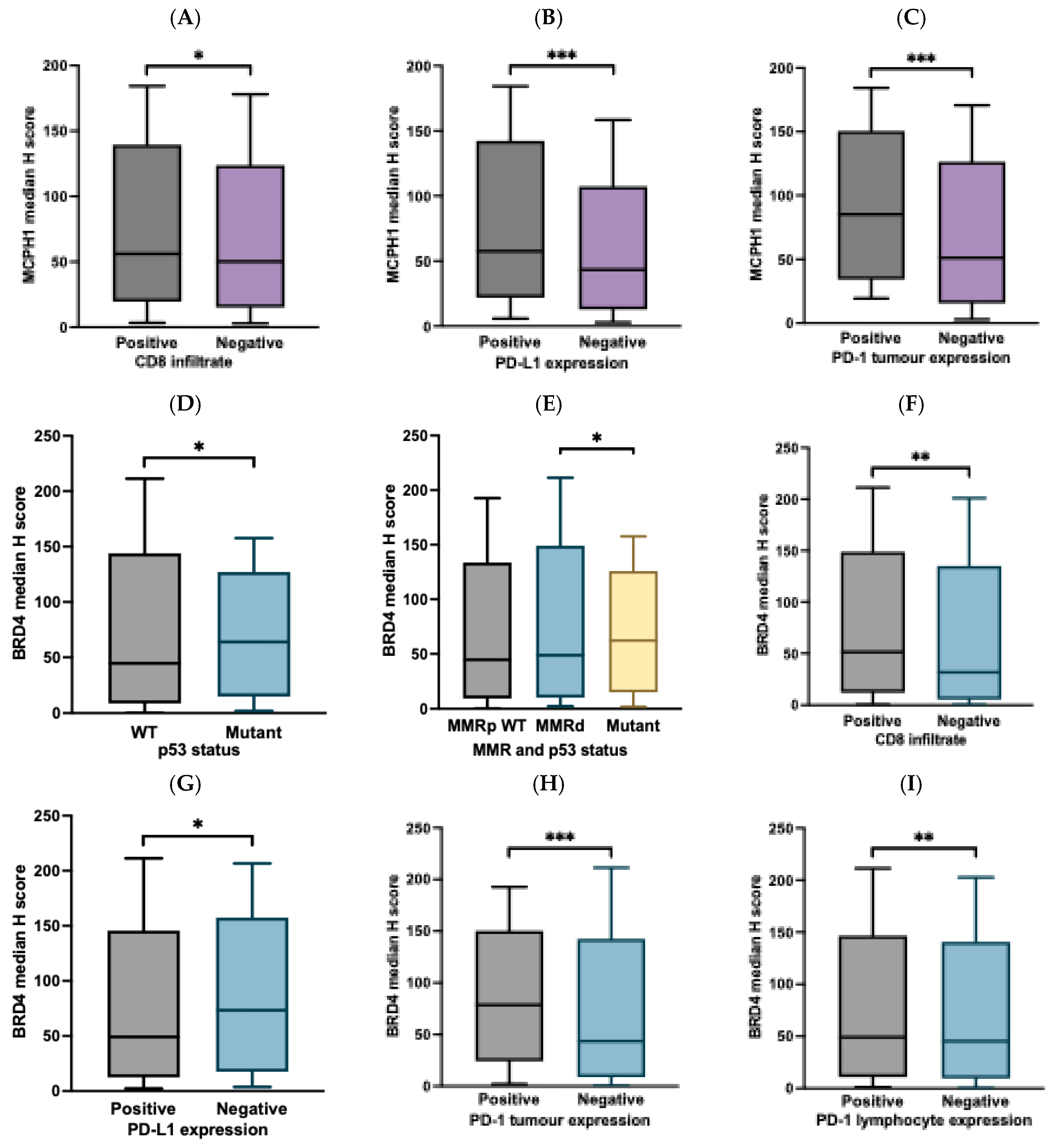

3.5. Correlation of MCPH1 and BRD4 Expression with ICI Biomarkers

3.6. Univariate and Multivariate Analyses in EC and Survival

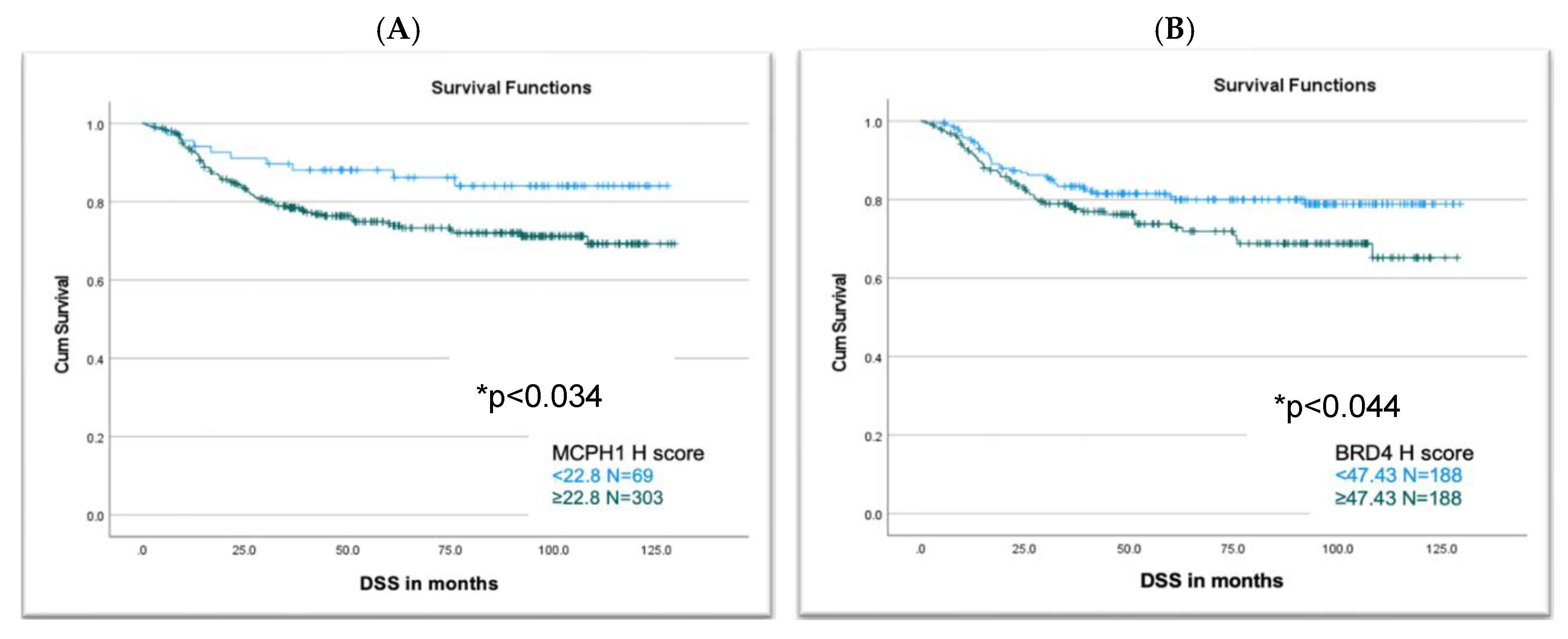

3.7. MCPH1 and BRD4 Expression Association with Survival

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:17–48.

- Mullins MA, Cote ML. Beyond obesity: the rising incidence and mortality rates of uterine corpus cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(22):1851–53. [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®), Uterine Neoplasms, Version 2.2024.

- Bell DW, Ellenson LH. Molecular Genetics of Endometrial Carcinoma. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease. 2019;14:339-67. [CrossRef]

- Abdulfatah E, Wakeling E, Sakr S, Al-Obaidy K, Bandyopadhyay S, Morris R, et al. Molecular classification of endometrial carcinoma applied to endometrial biopsy specimens: Towards early personalized patient management. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;154(3):467-74. [CrossRef]

- Concin N, Matias-Guiu X, Vergote I, Cibula D, Mirza MR, Marnitz S, et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021;31(1):12-39. [CrossRef]

- Talhouk A, McConechy MK, Leung S, Yang W, Lum A, Senz J, et al. Confirmation of ProMisE: A simple, genomics-based clinical classifier for endometrial cancer. Cancer. 2017;123(5):802-13. [CrossRef]

- Brunner MC, Chambers CA, Chan FK, Hanke J, Winoto A, Allison JP. CTLA-4-Mediated inhibition of early events of T cell proliferation. J Immunol. 1999;162(10):5813-20.

- Yusof MN, Chew KT, Kampan NC, Shafiee MN. Expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 in Endometrial Cancer: Molecular and Clinical Significance. Vol. 24, Int J of Mol Sci. 2023;24(20):15233. [CrossRef]

- Howitt BE, Shukla SA, Sholl LM, Ritterhouse LL, Watkins JC, Rodig S, et al. Association of Polymerase e-Mutated and Microsatellite-Instable Endometrial Cancers with Neoantigen Load, Number of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes, and Expression of PD-1 and PD-L1. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:1319–23. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita H, Nakayama K, Ishikawa M, Nakamura K, Ishibashi T, Sanuki K, et al. Microsatellite instability is a biomarker for immune checkpoint inhibitors in endometrial cancer. Oncotarget 2018;9:5652. [CrossRef]

- Lin-Zhi Z, Hong-Qi X, Jie C. Mismatch repair gene MSH6 correlates with the prognosis, immune status and immune checkpoint inhibitors response of endometrial cancer. Frontiers in Immunology 2024;15:1302797.

- Eerkens AL, Brummel K, Vledder A, et al. Neoadjuvant immune checkpoint blockade in women with mismatch repair deficient endometrial cancer: a phase I study. Nat Commun 2024;15:7695. [CrossRef]

- Lin SY, Elledge SJ. Multiple tumor suppressor pathways negatively regulate telomerase. Cell. 2003;113(7):881-9. [CrossRef]

- Jackson AP, Eastwood H, Bell SM, Adu J, Toomes C, Carr IM, et al. Identification of Microcephalin, a Protein Implicated in Determining the Size of the Human Brain. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2002;71(1):136-42. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Z-W, Tapias A, Bruhn C, Gruber R, Sukchev M, Wang Z-Q. DNA damage response in microcephaly development of MCPH1 mouse model. DNA Repair. 2013;12(8):645-55. [CrossRef]

- Zhang B, Wang E, Dai H, Hu R, Liang Y, Li K, et al. BRIT1 regulates p53 stability and functions as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34(10):2271-80. [CrossRef]

- Denu RA, Burkard ME. Analysis of the “centrosome-ome” identifies MCPH1 deletion as a cause of centrosome amplification in human cancer. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):11921. [CrossRef]

- Bilbao C, Ramírez R, Rodríguez G, Falcón O, León L, Díaz-Chico N, et al. Double strand break repair components are frequent targets of microsatellite instability in endometrial cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(15):2821-7. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Li M, Liu Z, Kang W, Cui Y, Han J, et al. The Oncogenic Role of Human Microcephalin Gene Revealed by Pan-Cancer Analysis. 2022. Available from: http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2022.11.18.22282275. [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa T, Filippakopoulos P. Functions of bromodomain-containing proteins and their role in homoeostasis and cancer. Nature Reviews. 2017;18(4):246-62. [CrossRef]

- Sun, SY. Essential roles of BRD4 in cancer: DNA damage, transcription regulation, and signal transduction. Global Translational Medicine. 2023;2(3):1442. [CrossRef]

- Shi J, Vakoc CR. The Mechanisms behind the Therapeutic Activity of BET Bromodomain Inhibition. Molecular Cell. 2014; (54):728-36. [CrossRef]

- Donati B, Lorenzini E, Ciarrocchi A. BRD4 and Cancer: Going beyond transcriptional regulation. Molecular Cancer. 2018;17:164. [CrossRef]

- Pang Y, Bai G, Zhao J, Wei X, Li R, Li J, et al. The BRD4 inhibitor JQ1 suppresses tumor growth by reducing c-Myc expression in endometrial cancer. J Transl Med. 2022;20(1):336. [CrossRef]

- Fu Y, Yang B, Cui Y, Hu X, Li X, Lu F, et al. BRD4 inhibition impairs DNA mismatch repair, induces mismatch repair mutation signatures and creates therapeutic vulnerability to immune checkpoint blockade in MMR-proficient tumors. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11(4):e006070. [CrossRef]

- Saglam O, Cao B, Wang X, Toruner GA, Conejo-Garcia JR. Expression of epigenetic pathway related genes in association with PD-L1, ER/PgR and MLH1 in endometrial carcinoma. PLoS One. 2022;17(2). [CrossRef]

- Lam FC, Kong YW, Huang Q. et al. BRD4 prevents the accumulation of R-loops and protects against transcription–replication collision events and DNA damage. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4083. [CrossRef]

- Tanimoto S, Sone K, Jonouchi Y, Hachijo R, Suzuki E, Tsuboyama N, et al. BET inhibitor JQ1 induces apoptosis of ovarian and endometrial endometrioid carcinoma cells by downregulating c-Myc. Oncol Lett. 2024;29(3):106. [CrossRef]

- Gyorffy, B. Integrated analysis of public datasets for the discovery and validation of survival-associated genes in solid tumors. Innovation. 2024;5(3):100625. [CrossRef]

- Prat, J. FIGO’s staging classification for cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum. J Gynecol Oncol. 2015;26(2):87-9.

- Johnson RJ, Cummings M, Thangavelu A, Theophilou G, Hutson R, Broadhead T, Nugent D, De Jong D, Munot S, Laios A, Allen K, Mappa G, Gahir N, Zubayraeva A, Grzelinski M, Orsi NM. PD-L1 and PD-1 expression is an independent prognostic marker in endometrial cancer, especially those with high-risk features. (in preparation for submission).

- Bankhead P, Loughrey MB, Fernández JA, Dombrowski Y, McArt DG, Dunne PD, et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):16878. [CrossRef]

- Yusof MN, Chew KT, Kampan NC, Shafiee MN. Expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 in Endometrial Cancer: Molecular and Clinical Significance. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(20):15233. [CrossRef]

- Cao W, Ma X, Fischer JV, Sun C, Kong B, Zhang Q. Immunotherapy in endometrial cancer: rationale, practice and perspectives. Biomarker Research. 2021;9(11):49. [CrossRef]

- Engerud H, Berg HF, Myrvold M, Halle MK, Bjorge L, Haldorsen IS, et al. High degree of heterogeneity of PD-L1 and PD-1 from primary to metastatic endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;157(1):260-67. [CrossRef]

- Kondratiev S, Sabo E, Yakirevich E, Lavie O, Resnick MB. Intratumoral CD8+ T lymphocytes as a prognostic factor of survival in endometrial carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(13):4450-6. [CrossRef]

- Lainé A, Gonzalez-Lopez AM, Hasan U, Ohkuma R, Ray-Coquard I. Immune Environment and Immunotherapy in Endometrial Carcinoma and Cervical Tumors. Cancers. 2023;15(7):2042. [CrossRef]

- Santin AD, Bellone S, Buza N, Choi J, Schwartz PE, Schlessinger J, et al. Regression of chemotherapy-resistant polymerase ϵ (POLE) ultra-mutated and MSH6 hyper-mutated endometrial tumors with nivolumab. Clinical Cancer Research. 2016;22(23):5682-7. [CrossRef]

- Heredia Soto V, Pellinen T, Turkki R, Ramón Patiño JL, Ruz-Caracuel I, García de la Calle LE, et al. Prognostic role of CD3, CD4, CD8 and FOXP3 positive populations in early-stage endometrial carcinoma. Annals of Oncology. 2020;31:862P.

- Strickland KC, Howitt BE, Shukla SA, Rodig S, Ritterhouse LL, Liu JF, et al. Association and prognostic significance of BRCA1/2-mutation status with neoantigen load, number of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and expression of PD-1/PD-L1 in high grade serous ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(12)13587-98. [CrossRef]

- Behnke A, Mack M, Fieres J, Christmann M, Bürkle A, Moreno-Villanueva M, et al. Expression of DNA repair genes and its relevance for DNA repair in peripheral immune cells of patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1). [CrossRef]

- Stewart CJR, Crook ML. SWI/SNF complex deficiency and mismatch repair protein expression in undifferentiated and dedifferentiated endometrial carcinoma. Pathology. 2015;47(5). [CrossRef]

- Alsolami M, Aboalola D, Malibari D, Alghamdi T, Alshekhi W, Jad H, et al. The emerging role of MCPH1/BRIT1 in carcinogenesis. Frontiers in Oncology. 2023;13. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Baek GH, Ramanand SG, Sharp A, Gao Y, Yuan W, et al. BRD4 Promotes DNA Repair and Mediates the Formation of TMPRSS2-ERG Gene Rearrangements in Prostate Cancer. Cell Rep. 2018;22(3):796-808. [CrossRef]

- Drumond-Bock AL, Wang L, Wang L, Cybula M, Rostworowska M, Kinter M, et al. Increased expression of BRD4 isoforms long (BRD4-L) and short (BRD4-S) promotes chemotherapy resistance in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Genes Cancer. 2023;12;14:56-76.

- Jones D, Lin D. Amplification of the NSD3-BRD4-CHD8 pathway in pelvic high-grade serous carcinomas of tubo-ovarian and endometrial origin. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017; 7(2):301-7.

- Chen Y, Zhao W, Bi F, Pan X, Yin L, Zhao C. Significance of TP53 Mutational Status-Associated Signature in the Progression and Prognosis of Endometrial Carcinoma. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022.1817339. [CrossRef]

- Zhou JX, Agborbesong E, Li LX, Li X. Bromodomain Protein BRD4-Mediated Mutant p53 Transcription Promotes TNBC Progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(23):15163. [CrossRef]

- Efe G, Dunbar KJ, Sugiura K, Cunningham K, Carcamo S, Karaiskos S, et al. p53 Gain-of-Function Mutation Induces Metastasis via BRD4-Dependent CSF-1 Expression. Cancer Discov. 2023;13(12). [CrossRef]

- Latif AL, Newcombe A, Li S, Gilroy K, Robertson NA, Lei X, et al. BRD4-mediated repression of p53 is a target for combination therapy in AML. Nat Commun. 2021; 11;12(1):241. [CrossRef]

- Feroz B, Pan TL, Leitner K, Ebner C, Steger K, Kildal W, et al. Tumoral programmed cell death 1 (PD1) expression in endometrial carcinoma is a prognostic marker for patient outcome. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2024;34(11):1711-18. [CrossRef]

- Hu J, Li G, He X, Gao X, Pan D, Dong X, Huang W, Qiu F, Chen LF, Hu X. Brd4 modulates metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation by regulating colonic macrophage infiltration in high-fat diet-fed mice. Commun Biol. 2024;28;7(1):1708. [CrossRef]

- Chen C, Xu L, Gao R, Wang S, Zhang Y, Wang C, Zeng C, Li Y. Transcriptome-Based Co-Expression of BRD4 and PD-1/PD-L1 Predicts Poor Overall Survival in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Front Pharmacol. 2021;11:582955. [CrossRef]

- Chen P, Zhou J, Li J, Zhang Q, Zuo Q. TIPE1 suppresses osteosarcoma tumor growth by regulating macrophage infiltration. Clinical and Translational Oncology. 2019;21(3):334-341. [CrossRef]

- Perrier A, Didelot A, Laurent-Puig P, Blons H, Garinet S. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Biomolecules 2020;10:1061. [CrossRef]

- Lovén J, Hoke HA, Lin CY, Lau A, Orlando DA, Vakoc CR, et al. Selective inhibition of tumour oncogenes by disruption of super-enhancers. Cell. 2013;153(2): 320-334. [CrossRef]

- Casey SC, Tong L, Li Y, Do R, Walz S, Fitzgerald KN, GouwAM, Baylot V, Gutgemann I, Eilers M, et al. MYC regulates the antitumor immune response through CD47 and PD-L1. Science. 2016;353:227-231. [CrossRef]

- Wu SY, Lee CF, Lai HT, Yu CT, Lee JE, Zuo H, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, Ge K, Wan Y, Chiang CM. Opposing Functions of BRD4 Isoforms in Breast Cancer. Mol Cell. 2020;78(6):1114-32. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | MCPH1 N=372 N (%) | BRD4 N=376 N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age distribution | 372 | 376 |

| ≥ 50 | 322 (86.6) | 325 (86.4) |

| < 50 | 50 (13.4) | 51 (13.6) |

| Tumour grade | 372 | 376 |

| Low (grade I and II) | 219 (58.8) | 223 (59.3) |

| High (grade III) | 153 (41.1) | 153 (40.6) |

| FIGO stage | 372 | 376 |

| Stage I | 231 (62.0) | 235 (62.5) |

| Stage II | 38 (10.2) | 37 (9.8) |

| Stage III | 73 (19.6) | 74 (19.7) |

| Stage IV | 30 (8.0) | 30 (7.9) |

| Histological subtypes | 372 | 376 |

| Endometrioid | 262 (70.4) | 266 (70.7) |

| Serous | 30 (8.0) | 30 (7.9) |

| Clear cell | 11 (2.9) | 10 (2.6) |

| Carcinosarcoma | 24 (6.4) | 25 (6.6) |

| Mixed | 43 (11.5) | 43 (11.4) |

| Mucinous | 1(0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Undifferentiated | 1(0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Lymphovascular space invasion status | 369 | 373 |

| Present | 195 (52.8) | 197 (52.8) |

| Absent | 174 (47.2) | 176 (47.1) |

| Lymph node status | 372 | 377 |

| Non sampled | 74 (19.8) | 77 (20.4) |

| Positive | 56 (15) | 57 (15.1) |

| Negative | 242 (65) | 243 (64.4) |

| Cervical stromal invasion | 371 | 375 |

| Positive | 86 (23.1) | 86 (22.9) |

| Negative | 285 (76.8) | 289 (77.0) |

| Depth of myometrial invasion | 372 | 376 |

| Invasion of inner half | 186 (50) | 189 (50.2) |

| Invasion of outer half | 186 (50) | 187 (49.7) |

| Received Chemotherapy | 372 | 376 |

| Yes | 153 (41.1) | 63 (16.7) |

| No | 219 (58.8) | 313 (83.2) |

| Received Radiotherapy | 372 | 376 |

| Yes | 133 (35.7) | 133 (35.3) |

| No | 239 (64.2) | 243 (64.6) |

| Vital status | 372 | 376 |

| Alive | 285 (76.6) | 289 (76.9) |

| Deceased | 87 (23.4) | 87 (23.13) |

| Parameter | MCPH1 H score expression | BRD4 H score expression | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous* | Categorised** | Continuous* | Categorised** | |||||||

| Median | p value | Low (<22.8) N (%) |

High (≥22.8) N (%) |

p value | Median | p value | Low (<47.43) N (%) |

High (≥47.43) N (%) |

p value | |

| Age distribution | ||||||||||

| < 50 ≥ 50 |

53.40 53.13 |

0.933 | 9 (2.4) 60 (16.1) |

41 (11.0) 262 (70.4) |

0.915 | 43.54 48.73 |

0.318 | 29 (7.7) 159 (42.3) |

22 (5.9) 166 (44.1) |

0.292 |

| Tumour grade | ||||||||||

| Low grade High grade |

56.63 49.66 |

0.274 | 41 (11) 28 (7.5) |

178 (47.8) 125 (33.6) |

0.918 | 44.78 52.36 |

0.054 | 117 (31.1) 71 (18.9) |

106 (28.2) 82 (21.8) |

0.248 |

| FIGO stage | ||||||||||

| Stage I Stage II Stage III Stage IV |

53.22 61.41 53.54 51.56 |

0.764 |

48 (12.9) 6 (1.6) 12 (3.2) 3 (0.8) |

183 (49.2) 32 (8.6) 61 (16.4) 27 (7.3) |

0.454 |

47.07 44.09 51.82 50.82 |

0.661 | 120 (31.9) 20 (5.3) 35 (9.3) 13 (3.5) |

115 (30.6) 17 (4.5) 39 (10.4) 17 (4.5) |

0.777 |

| Histological subtypes | ||||||||||

| Endometrioid Serous Clear cells Carcinosarcoma Mixed Mucinous Undifferentiated |

53.28 46.26 73.43 43.18 71.78 00.00 00.00 |

0.093 | 51 (13.7) 7 (1.9) 2 (0.5) 3 (0.8) 6 (1.6) 0 (0) 0 (0) |

211 (56.7) 23 (6.2) 9 (2.4) 21 (5.6) 37 (9.9) 1 (0.3) 1 (0.3) |

0.896 | 44.66 63.00 31.20 57.63 48.85 00.00 00.00 |

0.131 | 139 (37) 11 (2.9) 6 (1.6) 9 (2.4) 21 (5.6) 1 (0.3) 1 (0.3) |

127 (33.8) 19 (5.1) 4 (1.1) 16 (4.2) 22 (5.9) 0 (0) 0 (0) |

0.316 |

| Histological categorised | ||||||||||

| Endometrioid Non-endometrioid |

53.28 52.11 |

0.577 | 51 (13.7) 18 (4.8) |

211 (56.7) 92 (24.7) |

0.482 | 44.66 56.97 |

0.030 | 139 (37) 49 (13) |

127 (33.8) 61 (16.2) |

0.174 |

| Lymphovascular space invasion | ||||||||||

| Positive Negative |

52.95 53.37 |

0.712 | 34 (9.2) 34 (9.2) |

161 (43.6) 140 (37.9) |

0.603 | 49.50 42.21 |

0.052 | 93 (24.9) 93 (24.9) |

104 (27.9) 83 (22.3) |

0.277 |

| Lymph node status | ||||||||||

| Positive Negative |

52.11 52.14 |

0.829 | 10 (3.4) 45 (15.1) |

46 (15.4) 197 (66.1) |

0.898 | 44.46 53.84 |

0.501 | 26 (8.7) 122 (40.7) |

31 (10.3) 121 (40.3) |

0.533 |

| Cervical stromal involvement | ||||||||||

| Positive Negative |

53.11 53.22 |

0.366 | 10 (2.7) 59 (15.9) |

76 (20.5) 226 (60.9) |

0.058 | 49.13 47.07 |

0.402 | 40 (10.7) 147 (39.2) |

46 (12.3) 142 (37.9) |

0.478 |

| Depth of myometrial invasion | ||||||||||

| Invasion of inner half Invasion of outer half |

53.92 51.56 |

0.917 | 37 (9.9) 32 (8.6) |

149 (40.1) 154 (41.4) |

0.505 | 43.54 62.66 |

0.132 | 100 (26.6) 88 (23.4) |

89 (23.7) 99 (26.3) |

0.257 |

| Adjuvant Chemotherapy | ||||||||||

| Yes No |

51.45 53.37 |

0.580 | 8 (2.2) 61 (16.4) |

54 (14.5) 249 (66.9) |

0.210 | 44.78 48.47 |

0.531 | 34 (9) 154 (41) |

29 (7.7) 159 (42.3) |

0.490 |

| Adjuvant Radiotherapy | ||||||||||

| Positive Negative |

52.96 53.32 |

0.692 | 27 (7.3) 42 (11.3) |

106 (28.5) 197 (53) |

0.517 | 44.90 48.85 |

0.692 | 70 (18.6) 118 (31.4) |

63 (16.8) 125 (33.2) |

0.450 |

| Adjuvant Therapy | ||||||||||

| Positive Negative |

52.46 53.39 |

0.810 | 29 (7.8) 40 (10.8) |

124 (33.3) 179 (48.1) |

0.866 | 44.90 48.85 |

0.980 | 80 (21.3) 108 (28.7) |

73 (19.4) 115 (30.6) |

0.462 |

| Event of EC death | ||||||||||

| Alive Deceased |

52.96 55.22 |

0.126 | 59 (15.9) 10 (2.7) |

226 (60.8) 77 (20.7) |

0.053 | 45.37 54.52 |

0.192 | 152 (40.4) 36 (9.6) |

137 (36.4) 51 (13.6) |

0.067 |

| Parameter | MCPH1 H score expression | BRD4 H score expression | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous | Categorised | Continuous | Categorised | |||||||

| Median | p value |

Low (<22.8) N (%) |

High (≥22.8) N (%) |

p value | Median | p value | Low (<47.43) N (%) |

High (≥47.43) N (%) |

p value |

|

| p53 IHC staining status | ||||||||||

| Wild type (WT) Mutant |

51.06 51.34 |

0.620 | 53 (16.3) 12 (3.7) |

205 (63.1) 55 (16.9) |

0.631 | 44.66 63.98 |

0.011 | 139 (42.1) 25 (7.6) |

123 (37.3) 43 (13) |

0.017 |

| MMR IHC staining status* | ||||||||||

| MMR-proficient (MMRp) MMR-deficient (MMRd) |

52.63 52.61 |

0.972 | 41 (11.5) 24 (6.8) |

220 (62) 70 (19.7) |

0.035 | 47.5 48.7 |

0.966 | 132 (36.8) 46 (12.8) |

132 (36.8) 49 (13.6) |

0.792 |

| Mutation status | ||||||||||

|

MMRp p53WT MMRd p53 Mutant |

50.88 52.61 51.67 |

0.691 | 30 (9.1) 24 (7.3) 11 (3.3) |

139 (42.2) 70 (21.3) 55 (16.7) |

0.246 | 44.66 48.73 62.20 |

0.054 | 92 (27.5) 46 (13.8) 25 (7.5) |

80 (24) 49 (14.7) 42 (12.6) |

0.080 |

| CD8 infiltration status** | ||||||||||

| Positive Negative |

56.21 50.32 |

0.025 | 43 (16.7) 21 (22.8) |

215 (83.3) 71 (77.2) |

0.189 | 51.3 31.5 |

0.189 | 116(44.4) 61 (65.6) |

145 (55.6) 32 (34.4) |

<0.001 |

| PD-L1 CPS status | ||||||||||

| Positive Negative |

57.61 43.37 |

<0.001 | 24 (11.4) 14 (6.7) |

130 (61.9) 42 (20) |

0.117 | 49.14 73.47 |

0.012 | 76 (35.8) 19 (9.0) |

80 (37.7) 37 (17.5) |

0.056 |

| PD-1 tumour cells | ||||||||||

| Positive Negative |

85.27 51.18 |

<0.001 | 1 (0.3) 64 (17.6) |

50 (13.8) 248 (68.3) |

0.001 | 84.02 49.14 |

<0.001 | 13 (3.5) 171 (46.6) |

38 (10.4) 145 (39.5) |

<0.001 |

| PD-1 lymphocyte | ||||||||||

| Positive Negative |

52.63 53.28 |

0.845 | 8 (2.2) 57 (15.7) |

35 (9.6) 263 (72.5) |

0.899 | 65.94 44.8 |

0.003 | 12 (3.3) 172 (46.9) |

32 (8.7) 151 (41.4) |

0.001 |

| Parameter | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%) | p value | HR (95%) | p value | |

|

MCPH1 expression High ≥ 22.8 Low <22.8 |

2.014 (1.041- 3.894) | 0.038 | 2.054 (1.017-4.149) | 0.045 |

|

BRD4 expression High ≥47.4 Low <47.4 |

1.544 (1.008- 2.367) | 0.046 | 1.112 (0.694-1.791) | 0.659 |

|

Tumour grade High vs Low |

2.948 (2.174- 3.997) | <0.001 | 2.244 (1.218-4.136) | 0.010 |

|

Lymphovascular space invasion Presence vs absence |

0.190 (0.114- 0.317) | <0.001 | 0.427 (0.201-0.907) | 0.027 |

|

Cervical stromal involvement Positive vs negative |

0.313 (0.021- 0.471) | <0.001 | 0.596 (0.368-0.964) | 0.035 |

|

Depth of myometrial invasion Invasion of inner half vs Invasion of outer half |

3.766 (2.372- 5.981) | <0.001 | 2.516 (1.336-4.741) | 0.004 |

|

Mutation status MMRp p53WT MMRd p53 Mutant |

3.093 (2.356- 4.061) | <0.001 | 2.212 (1.597-3.064) | <0.001 |

|

FIGO stage Stage I Stage II Stage III Stage IV |

2.661 (2.206- 3.210) | <0.001 | 2.355 (1.729-3.208) | <0.001 |

|

Histological subtypes Non EEC vs EEC |

1.273 (1.137-1.424) | <0.001 | 2.148 (1.059-4.357) | 0.034 |

|

p53 status Mutant vs Wild type |

6.192 (3.994- 9.600) | 0.017 | 0.001 (0.000-2.427E+46) | 0.897 |

|

Chemotherapy No vs Yes |

0.337 (0.219- 0.520) | <0.001 | 1.957 (1.068-3.586) | 0.030 |

|

Lymph node status Positive vs negative |

0.818 (0.652- 1.028) | 0.085 | 1.184 (0.791-1.772) | 0.412 |

|

MMR status MMRd vs MMRp |

0.917 (0.583- 1.441) | 0.706 | 22.052 (0.000-1.535E+26) | 0.916 |

|

Age <50 vs ≥50 years |

2.027 (0.982- 4.182) | 0.056 | 1.424 (0.570, 3.558) | 0.449 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).