Submitted:

15 July 2023

Posted:

18 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample collection and experimental design

2.2. Cells and Reagents

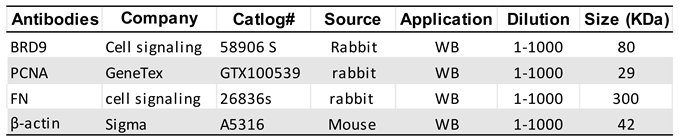

2.3. Protein extraction and Western Blot analysis

2.4. Proliferation assay

2.6. Measurement of Cell Cycle Phase Distribution

2.7. RNA-sequencing

2.8. Transcriptome Profiles Analysis

2.8.1. Transcriptome Data Analysis

2.8.2. Differential gene expression analysis

2.8.3. Pathway Analysis of DEGs

2.8.4. Functional and Regulatory Enrichment Analysis

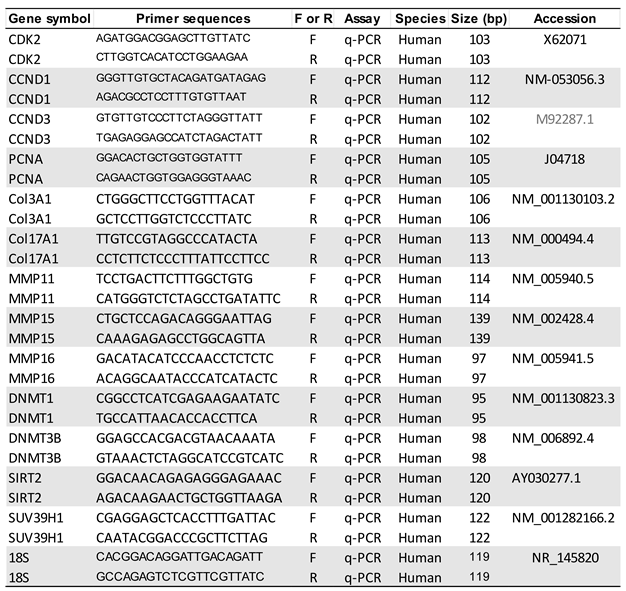

2.9. RNA extraction and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

2.10. Statistical analysis

3. Results

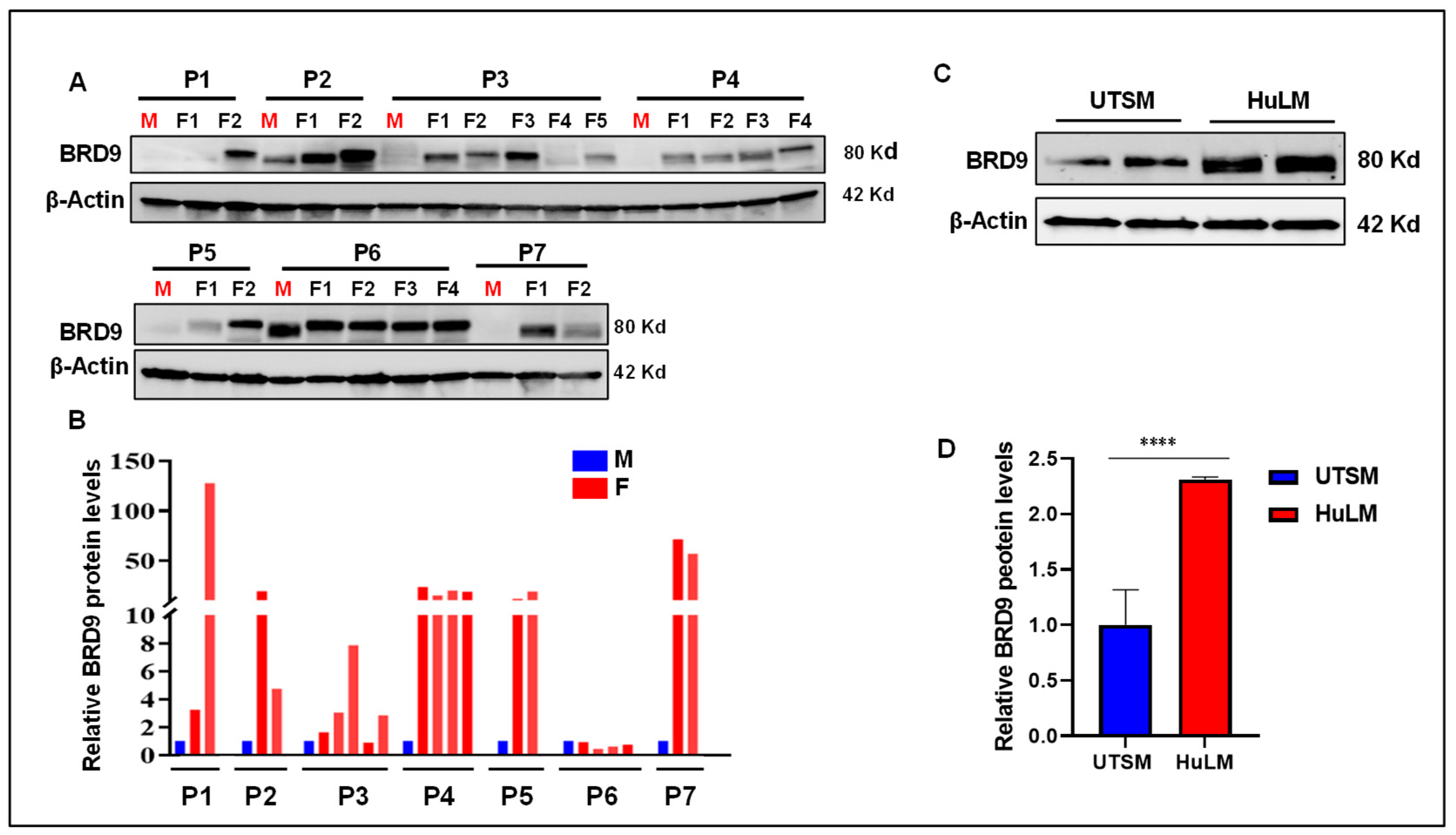

3.1. The level of BRD9 protein is aberrantly upregulated in uterine fibroids

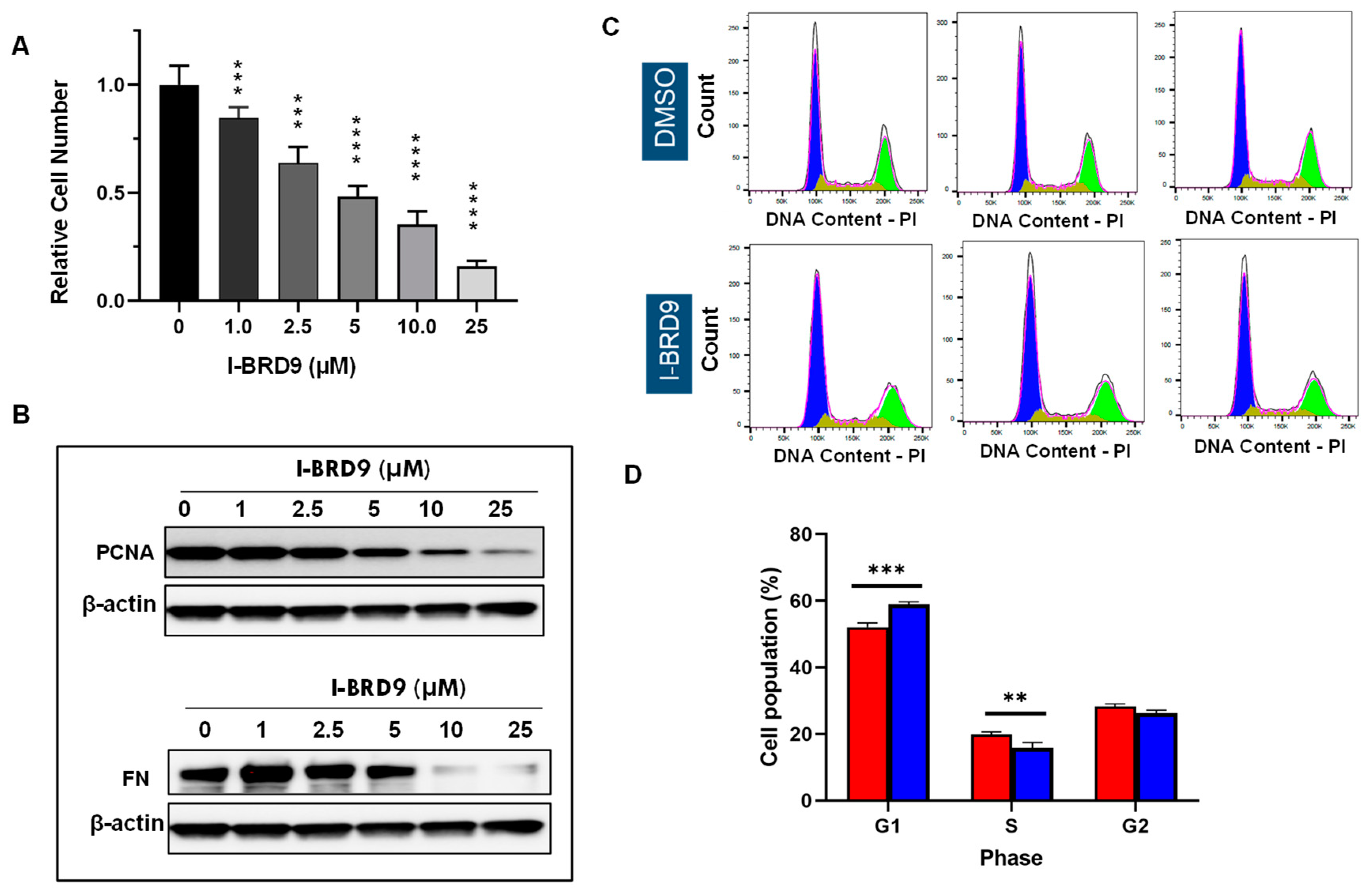

3.2. Inhibition of BRD9 showed decreased cell proliferation and anti-fibrotic characteristics in uterine fibroid cells

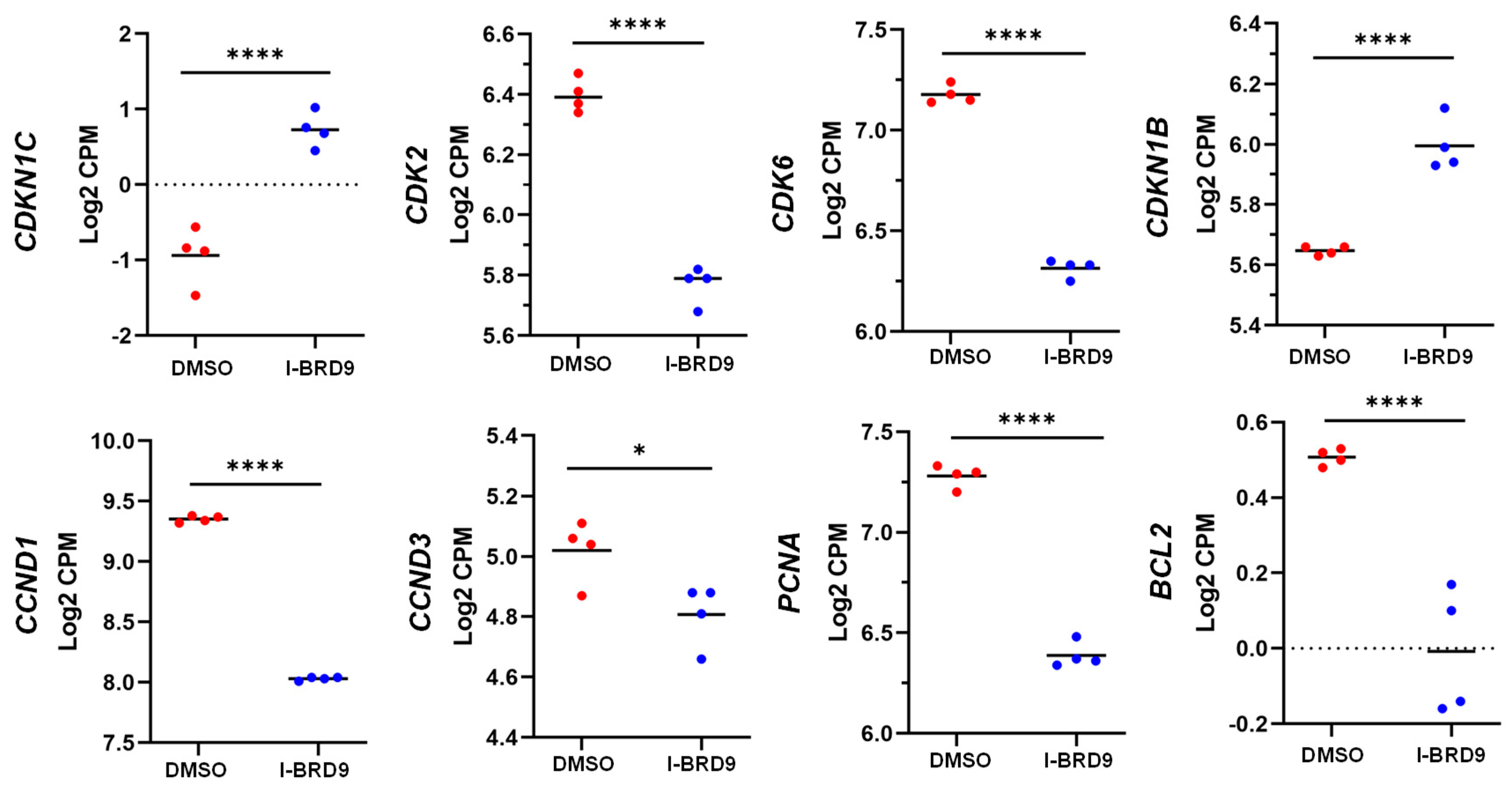

3.3. Inhibition of BRD9 induced apoptosis, necrosis, and cell cycle arrest in uterine fibroid cells

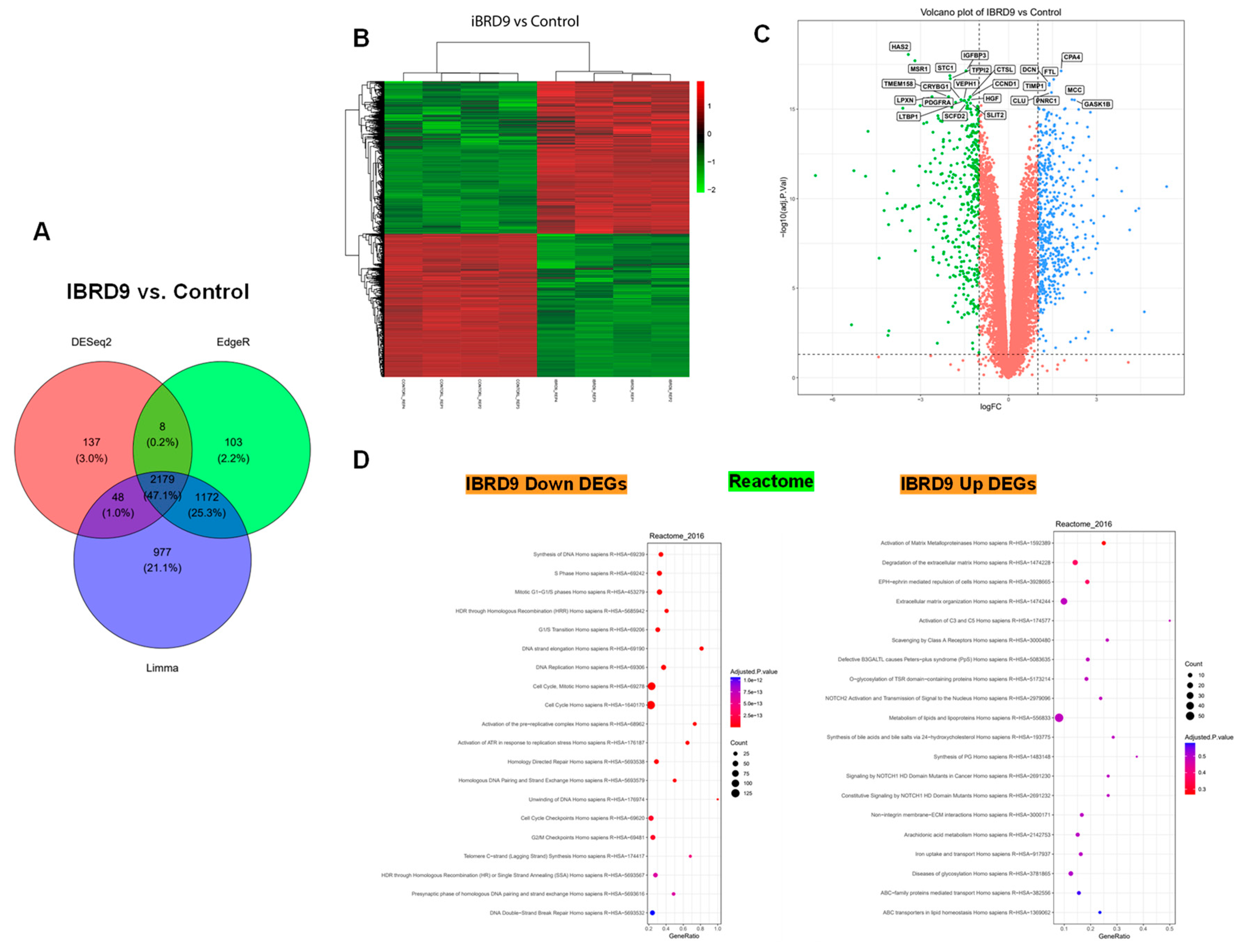

3.4. BRD9 inhibition causes extensive changes in the UF cell transcriptome

3.4.1. Differentially expressed genes upon I-BRD9 Treatment

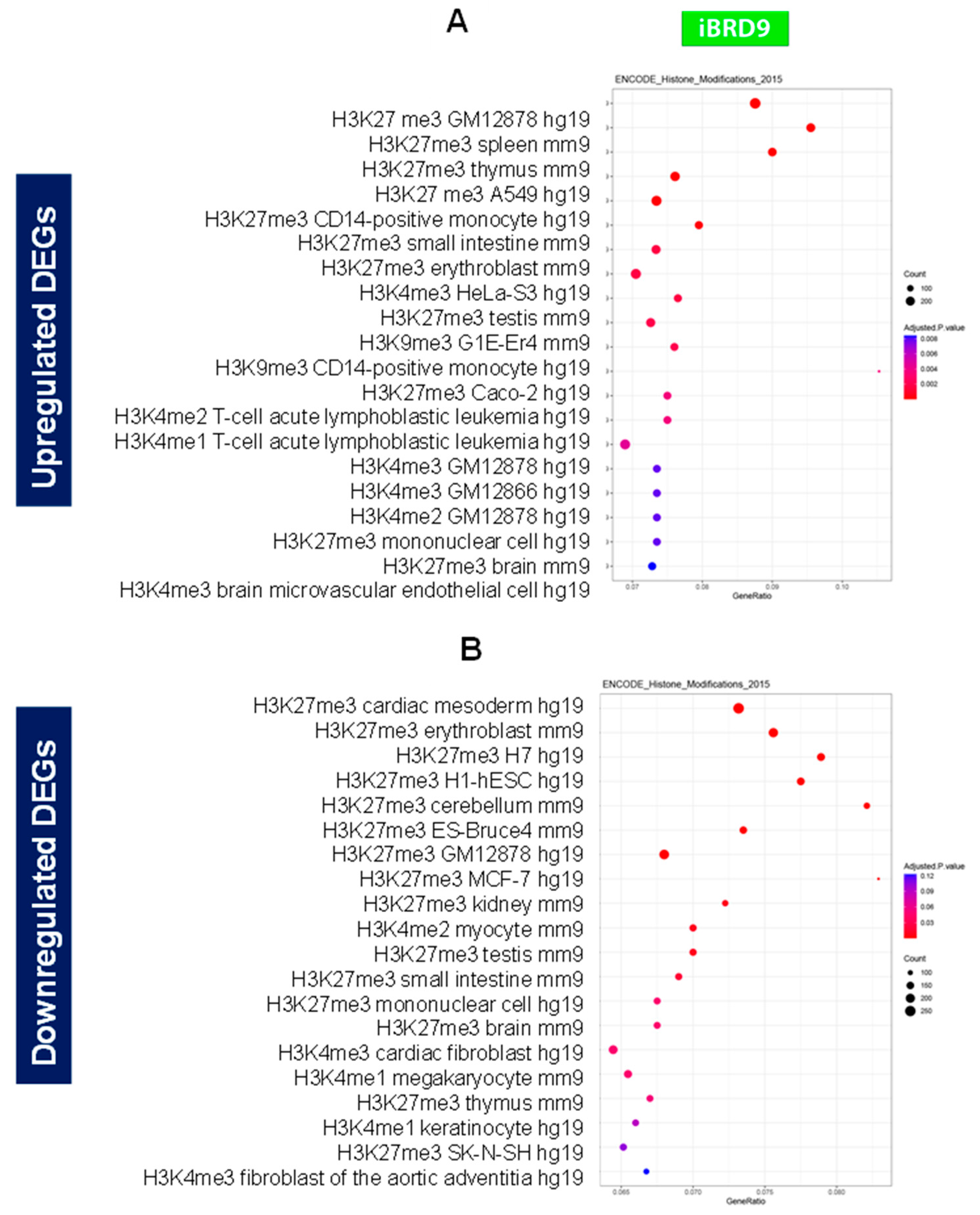

3.4.2. Enrichment pathway analysis

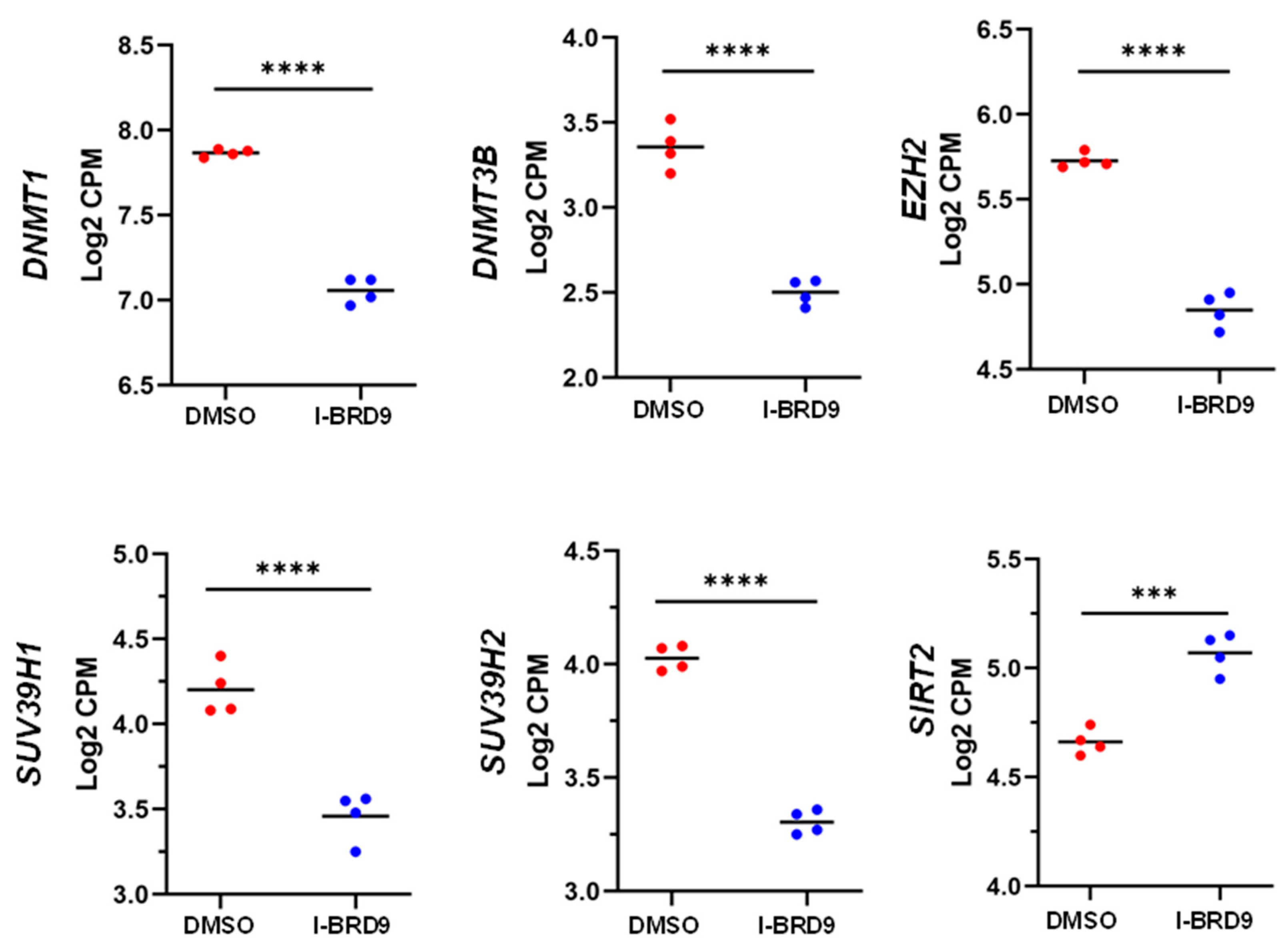

3.4.3. Inhibition of BRD9 altered the gene expression correlating to epigenetic modifications

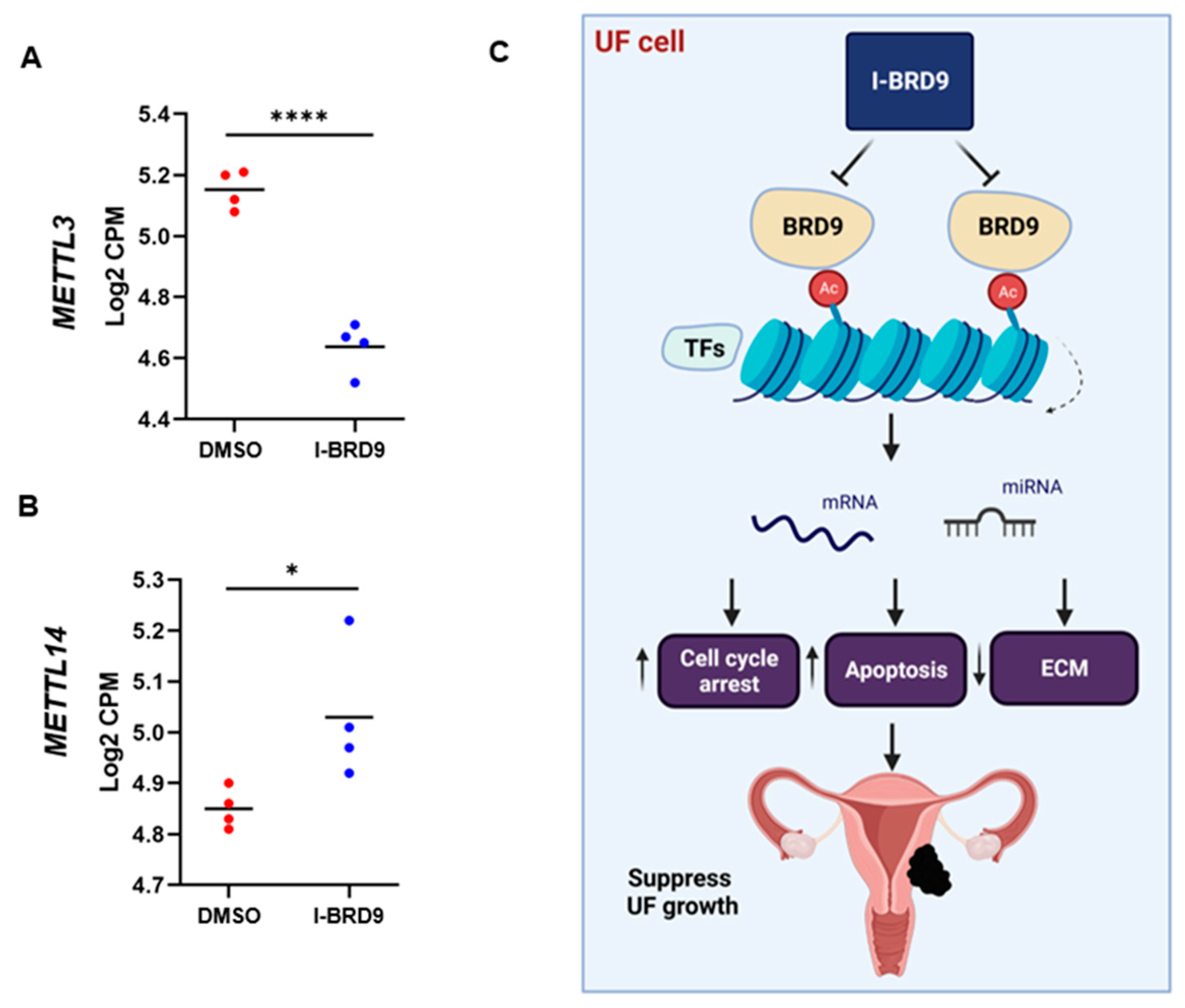

3.4.4. Inhibition of BRD9 altered gene expression associated with miRNA regulation

3.4.5. Inhibition of BRD9 altered the levels of m6A regulators in UF cells

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

References

- Yang, Q., et al., Comprehensive Review of Uterine Fibroids: Developmental Origin, Pathogenesis, and Treatment. Endocr Rev, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bulun, S.E., Uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med, 2013. 369(14): p. 1344-55. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, E.A., et al., Uterine fibroids. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2016. 2: p. 16043. [CrossRef]

- Whynott, R.M., K.C.C. Vaught, and J.H. Segars, The Effect of Uterine Fibroids on Infertility: A Systematic Review. Semin Reprod Med, 2017. 35(6): p. 523-532. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., et al., The Mechanism and Function of Epigenetics in Uterine Leiomyoma Development. Reprod Sci, 2016. 23(2): p. 163-75. [CrossRef]

- Berta, D.G., et al., Deficient H2A.Z deposition is associated with genesis of uterine leiomyoma. Nature, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K. and M.C. Barton, Bromodomain Histone Readers and Cancer. J Mol Biol, 2017. 429(13): p. 2003-2010. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.M., et al., Aberrant epigenetic regulation of bromodomain BRD4 in human colon cancer. J Mol Med (Berl), 2012. 90(5): p. 587-95. [CrossRef]

- Sahni, J.M. and R.A. Keri, Targeting bromodomain and extraterminal proteins in breast cancer. Pharmacol Res, 2018. 129: p. 156-176. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q. and A. Al-Hendy, Non-coding RNAs: an important regulatory mechanism in pathogenesis of uterine fibroids. Fertil Steril, 2018. 109(5): p. 802-803. [CrossRef]

- Chuang, T.D., A. Rehan, and O. Khorram, Functional role of the long noncoding RNA X-inactive specific transcript in leiomyoma pathogenesis. Fertil Steril, 2021. 115(1): p. 238-247. [CrossRef]

- George, J.W., et al., Integrated Epigenome, Exome, and Transcriptome Analyses Reveal Molecular Subtypes and Homeotic Transformation in Uterine Fibroids. Cell Rep, 2019. 29(12): p. 4069-4085 e6. [CrossRef]

- Moyo, M.B., J.B. Parker, and D. Chakravarti, Altered chromatin landscape and enhancer engagement underlie transcriptional dysregulation in MED12 mutant uterine leiomyomas. Nat Commun, 2020. 11(1): p. 1019. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., et al., Targeting Class I Histone Deacetylases in Human Uterine Leiomyosarcoma. Cells, 2022. 11(23). [CrossRef]

- Hugle, M., et al., Beyond the BET Family: Targeting CBP/p300 with 4-Acyl Pyrroles. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2017. 56(41): p. 12476-12480. [CrossRef]

- Clegg, M.A., et al., Advancements in the Development of non-BET Bromodomain Chemical Probes. ChemMedChem, 2019. 14(4): p. 362-385. [CrossRef]

- Vichaikul, S., et al., Inhibition of bromodomain extraterminal histone readers alleviates skin fibrosis in experimental models of scleroderma. JCI Insight, 2022. 7(9). [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, T. and P. Filippakopoulos, Functions of bromodomain-containing proteins and their roles in homeostasis and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2017. 18(4): p. 246-262. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.G., et al., Cytotoxic activity of bromodomain inhibitor NVS-CECR2-1 on human cancer cells. Sci Rep, 2020. 10(1): p. 16330. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., et al., The Polycomb Group Protein EZH2 Impairs DNA Damage Repair Gene Expression in Human Uterine Fibroids. Biol Reprod, 2016. 94(3): p. 69. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., et al., Role of histone deacetylases in regulation of phenotype of ovine newborn pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Cell Prolif, 2013. 46(6): p. 654-64. [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I., W. Huber, and S. Anders, Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol, 2014. 15(12): p. 550. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D., D.J. McCarthy, and G.K. Smyth, edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics, 2010. 26(1): p. 139-40. [CrossRef]

- Law, C.W., et al., voom: Precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol, 2014. 15(2): p. R29. [CrossRef]

- Kuleshov, M.V., et al., Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res, 2016. 44(W1): p. W90-7. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., et al., Altered DNA repair genes in human uterine fibroids are epigenetically regulated via EZH2 histone methyltransferase. Fertility and Sterility, 2015. 104(3). [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S., et al., Extracellular matrix in uterine leiomyoma pathogenesis: a potential target for future therapeutics. Hum Reprod Update, 2018. 24(1): p. 59-85. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S., et al., Extracellular matrix and Hippo signaling as therapeutic targets of antifibrotic compounds for uterine fibroids. Clin Transl Med, 2021. 11(7): p. e475. [CrossRef]

- Jamaluddin, M.F.B., P. Nahar, and P.S. Tanwar, Proteomic Characterization of the Extracellular Matrix of Human Uterine Fibroids. Endocrinology, 2018. 159(7): p. 2656-2669. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q. and A. Al-Hendy, Update on the Role and Regulatory Mechanism of Extracellular Matrix in the Pathogenesis of Uterine Fibroids. Int J Mol Sci, 2023. 24(6). [CrossRef]

- Leppert, P.C., F.L. Jayes, and J.H. Segars, The extracellular matrix contributes to mechanotransduction in uterine fibroids. Obstet Gynecol Int, 2014. 2014: p. 783289. [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.A., et al., Extracellular matrix (ECM) activates beta-catenin signaling in uterine fibroids. Reproduction, 2018. 155(1): p. 61-71. [CrossRef]

- Norian, J.M., et al., Characterization of tissue biomechanics and mechanical signaling in uterine leiomyoma. Matrix Biol, 2012. 31(1): p. 57-65. [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y., J. Liu, and C. He, RNA N6-methyladenosine methylation in post-transcriptional gene expression regulation. Genes Dev, 2015. 29(13): p. 1343-55. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., et al., A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol, 2014. 10(2): p. 93-5. [CrossRef]

- Jia, G., Y. Fu, and C. He, Reversible RNA adenosine methylation in biological regulation. Trends Genet, 2013. 29(2): p. 108-15. [CrossRef]

- Scheitl, C.P.M., et al., Site-specific RNA methylation by a methyltransferase ribozyme. Nature, 2020. 587(7835): p. 663-667. [CrossRef]

- Shen, H., et al., The emerging roles of N6-methyladenosine RNA methylation in human cancers. Biomark Res, 2020. 8: p. 24. [CrossRef]

- Bert, S.A., et al., Regional activation of the cancer genome by long-range epigenetic remodeling. Cancer Cell, 2013. 23(1): p. 9-22. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, N., et al., Targeting Hedgehog Pathway and DNA Methyltransferases in Uterine Leiomyosarcoma Cells. Cells, 2020. 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q. and A. Al-Hendy, The Regulatory Functions and the Mechanisms of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Cervical Cancer. Cells, 2022. 11(7). [CrossRef]

- Zaib, S., N. Rana, and I. Khan, Histone Modifications and their Role in Epigenetics of Cancer. Curr Med Chem, 2022. 29(14): p. 2399-2411. [CrossRef]

- Keyvani-Ghamsari, S., et al., Current understanding of epigenetics mechanism as a novel target in reducing cancer stem cells resistance. Clin Epigenetics, 2021. 13(1): p. 120. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M., et al., Activation of beta-Catenin Signaling and its Crosstalk With Estrogen and Histone Deacetylases in Human Uterine Fibroids. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2020. 105(4). [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., et al., Identification of Polycomb Group Protein EZH2-Mediated DNA Mismatch Repair Gene MSH2 in Human Uterine Fibroids. Reprod Sci, 2016. 23(10): p. 1314-25. [CrossRef]

- Schrump, D.S., J.A. Hong, and D.M. Nguyen, Utilization of chromatin remodeling agents for lung cancer therapy. Cancer J, 2007. 13(1): p. 56-64. [CrossRef]

- Qi, J., Bromodomain and extraterminal domain inhibitors (BETi) for cancer therapy: chemical modulation of chromatin structure. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2014. 6(12): p. a018663. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J., A. Daoud, and S.T. Eblen, Targeting Chromatin Remodeling for Cancer Therapy. Curr Mol Pharmacol, 2019. 12(3): p. 215-229. [CrossRef]

- Magnani, L., et al., Genome-wide reprogramming of the chromatin landscape underlies endocrine therapy resistance in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2013. 110(16): p. E1490-9. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D., et al., Small Molecules Targeting HATs, HDACs, and BRDs in Cancer Therapy. Front Oncol, 2020. 10: p. 560487. [CrossRef]

- Santillan, D.A., et al., Bromodomain and histone acetyltransferase domain specificities control mixed lineage leukemia phenotype. Cancer Res, 2006. 66(20): p. 10032-9. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, M.A., et al., Inhibition of BET recruitment to chromatin as an effective treatment for MLL-fusion leukaemia. Nature, 2011. 478(7370): p. 529-33. [CrossRef]

- Lucas, X. and S. Gunther, Targeting the BET family for the treatment of leukemia. Epigenomics, 2014. 6(2): p. 153-5. [CrossRef]

- Belkina, A.C., B.S. Nikolajczyk, and G.V. Denis, BET protein function is required for inflammation: Brd2 genetic disruption and BET inhibitor JQ1 impair mouse macrophage inflammatory responses. J Immunol, 2013. 190(7): p. 3670-8. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H., et al., JQ1 suppresses tumor growth through downregulating LDHA in ovarian cancer. Oncotarget, 2015. 6(9): p. 6915-30. [CrossRef]

- Richter, G.H.S., et al., Combined Inhibition of Epigenetic Readers and Transcription Initiation Targets the EWS-ETS Transcriptional Program in Ewing Sarcoma. Cancers (Basel), 2020. 12(2). [CrossRef]

- Mason, L.D., et al., The BRD9/7 Inhibitor TP-472 Blocks Melanoma Tumor Growth by Suppressing ECM-Mediated Oncogenic Signaling and Inducing Apoptosis. Cancers (Basel), 2021. 13(21). [CrossRef]

- Lu, J., et al., Gene Signature Associated With Bromodomain Genes Predicts the Prognosis of Kidney Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma. Front Genet, 2021. 12: p. 643935. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., et al., The Functional Role and Regulatory Mechanism of Bromodomain-Containing Protein 9 in Human Uterine Leiomyosarcoma. Cells, 2022. 11(14). [CrossRef]

- Boyson, S.P., et al., Functional Roles of Bromodomain Proteins in Cancer. Cancers (Basel), 2021. 13(14). [CrossRef]

- Magic, Z., G. Supic, and M. Brankovic-Magic, Towards targeted epigenetic therapy of cancer. J BUON, 2009. 14 Suppl 1: p. S79-88.

- Zhao, R. and A.G. Casson, Epigenetic aberrations and targeted epigenetic therapy of esophageal cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets, 2008. 8(6): p. 509-21. [CrossRef]

- Bai, H., et al., Genetic and epigenetic heterogeneity of epithelial ovarian cancer and the clinical implications for molecular targeted therapy. J Cell Mol Med, 2016. 20(4): p. 581-93. [CrossRef]

- Moustakim, M., et al., Chemical probes and inhibitors of bromodomains outside the BET family. Medchemcomm, 2016. 7(12): p. 2246-2264. [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y., Epigenetic cross-talk between DNA methylation and histone modifications in human cancers. Yonsei Med J, 2009. 50(4): p. 455-63. [CrossRef]

- Winter, S. and W. Fischle, Epigenetic markers and their cross-talk. Essays Biochem, 2010. 48(1): p. 45-61. [CrossRef]

- Szulwach, K.E., et al., Cross talk between microRNA and epigenetic regulation in adult neurogenesis. J Cell Biol, 2010. 189(1): p. 127-41. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, G., et al., HDAC Inhibition for the Treatment of Epithelioid Sarcoma: Novel Cross Talk Between Epigenetic Components. Mol Cancer Res, 2016. 14(1): p. 35-43. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W., et al., Investigating crosstalk between H3K27 acetylation and H3K4 trimethylation in CRISPR/dCas-based epigenome editing and gene activation. Sci Rep, 2021. 11(1): p. 15912. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y., et al., A brief review on the mechanisms of miRNA regulation. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics, 2009. 7(4): p. 147-54. [CrossRef]

- Perera, R.J. and A. Ray, Epigenetic regulation of miRNA genes and their role in human melanomas. Epigenomics, 2012. 4(1): p. 81-90. [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar, M., et al., Identification of epigenetic interactions between miRNA and DNA methylation associated with gene expression as potential prognostic markers in bladder cancer. BMC Med Genomics, 2017. 10(Suppl 1): p. 30. [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, E.D., J. Kjems, and S.J. Clark, Epigenetic architecture and miRNA: reciprocal regulators. Epigenomics, 2010. 2(6): p. 823-40. [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, R., et al., From 2646 to 15: differentially regulated microRNAs between progenitors from normal myometrium and leiomyoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2020. 222(6): p. 596 e1-596 e9. [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, B., et al., Characterization of the uterine leiomyoma microRNAome by deep sequencing. Genomics, 2012. 99(5): p. 275-81. [CrossRef]

- Ciebiera, M., et al., The Role of miRNA and Related Pathways in Pathophysiology of Uterine Fibroids-From Bench to Bedside. Int J Mol Sci, 2020. 21(8). [CrossRef]

- Rauch, S., C. He, and B.C. Dickinson, Targeted m(6)A Reader Proteins To Study Epitranscriptomic Regulation of Single RNAs. J Am Chem Soc, 2018. 140(38): p. 11974-11981. [CrossRef]

- Koranda, J.L., et al., Mettl14 Is Essential for Epitranscriptomic Regulation of Striatal Function and Learning. Neuron, 2018. 99(2): p. 283-292 e5. [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.L., et al., Epitranscriptomic m(6)A Regulation of Axon Regeneration in the Adult Mammalian Nervous System. Neuron, 2018. 97(2): p. 313-325 e6. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.J., H. Shi, and C. He, Epitranscriptomic influences on development and disease. Genome Biol, 2017. 18(1): p. 197. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., et al., YTH Domain Proteins: A Family of m(6)A Readers in Cancer Progression. Front Oncol, 2021. 11: p. 629560. [CrossRef]

- Kontur, C., et al., Ythdf m(6)A Readers Function Redundantly during Zebrafish Development. Cell Rep, 2020. 33(13): p. 108598. [CrossRef]

- Zhen, D., et al., m(6)A Reader: Epitranscriptome Target Prediction and Functional Characterization of N (6)-Methyladenosine (m(6)A) Readers. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2020. 8: p. 741. [CrossRef]

- Berlivet, S., et al., Readers of the m(6)A epitranscriptomic code. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech, 2019. 1862(3): p. 329-342. [CrossRef]

- Li, F., et al., Glutamate from nerve cells promotes perineural invasion in pancreatic cancer by regulating tumor glycolysis through HK2 mRNA-m6A modification. Pharmacol Res, 2023. 187: p. 106555. [CrossRef]

- Shimura, T., et al., Novel evidence for m(6)A methylation regulators as prognostic biomarkers and FTO as a potential therapeutic target in gastric cancer. Br J Cancer, 2022. 126(2): p. 228-237. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q. and A. Al-Hendy, The Functional Role and Regulatory Mechanism of FTO m(6)A RNA Demethylase in Human Uterine Leiomyosarcoma. Int J Mol Sci, 2023. 24(9). [CrossRef]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).