Submitted:

08 January 2026

Posted:

09 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

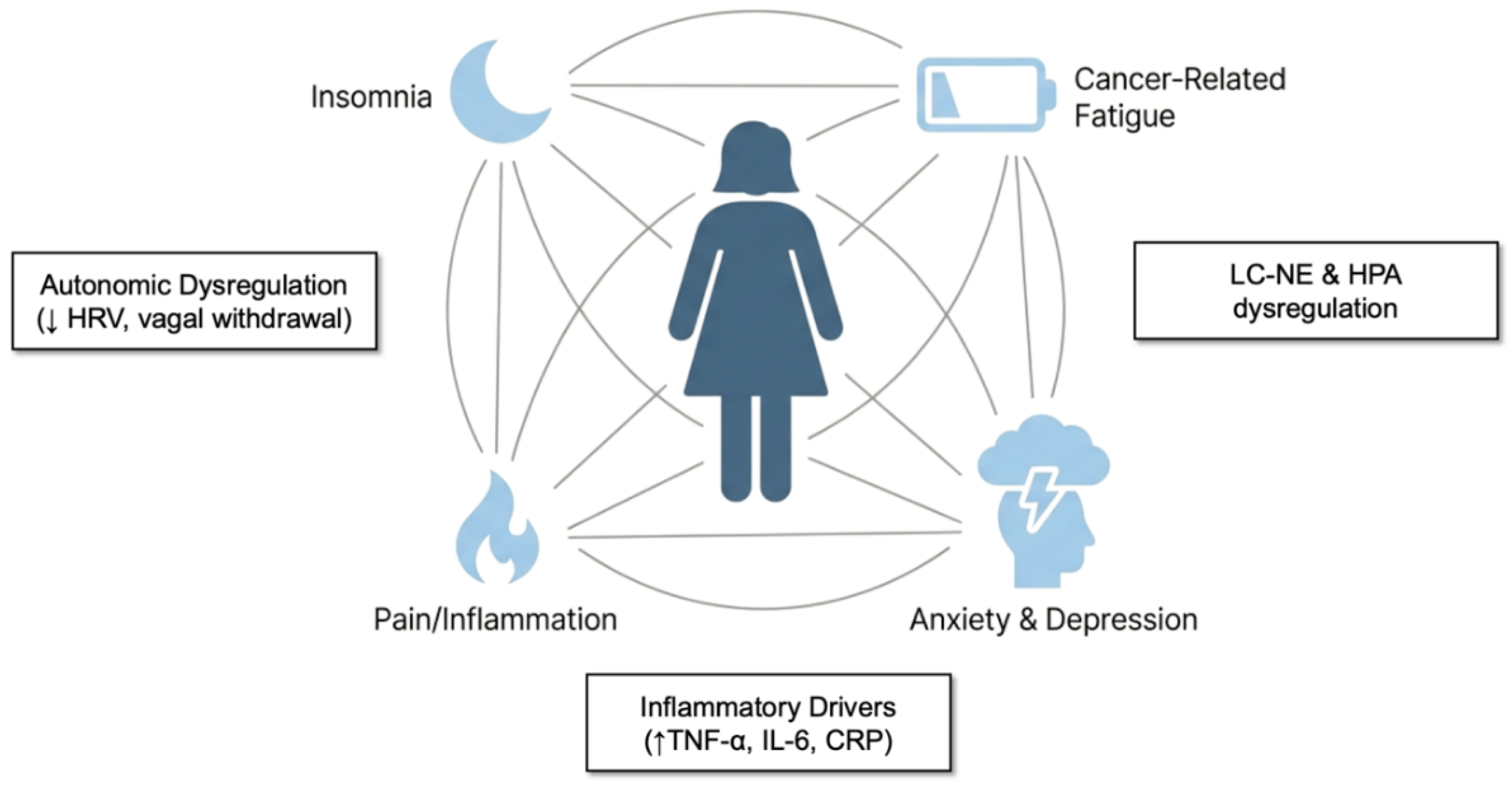

Symptom Clusters in Breast Cancer Survivorship: A Neuroimmune-Autonomic Perspective

Conceptualizing Symptom Clusters

Clinical Burdens

Inflammation Across Clusters

Autonomic Dysregulation and Reduced Vagal Tone Across Clusters

A Dysfunctional Psycho-Neuroimmune Loop

Rationale for Vagal Intervention

Psychophysiological Clusters: Inflammatory & Autonomic Mechanisms

Insomnia and Hyperarousal: Cytokine Activation, Dysregulated Arousal, and Sympathetic Dominance

Anxiety and Depression: Neuroimmune–HPA Imbalance and Vagal Withdrawal

Pain and Nociceptive Amplification: Cytokine Sensitization and Autonomic Dysregulation

Cancer-Related Fatigue: Neuroimmune Exhaustion and Blunted Vagal Signaling

Mechanistic Overlap Across Clusters

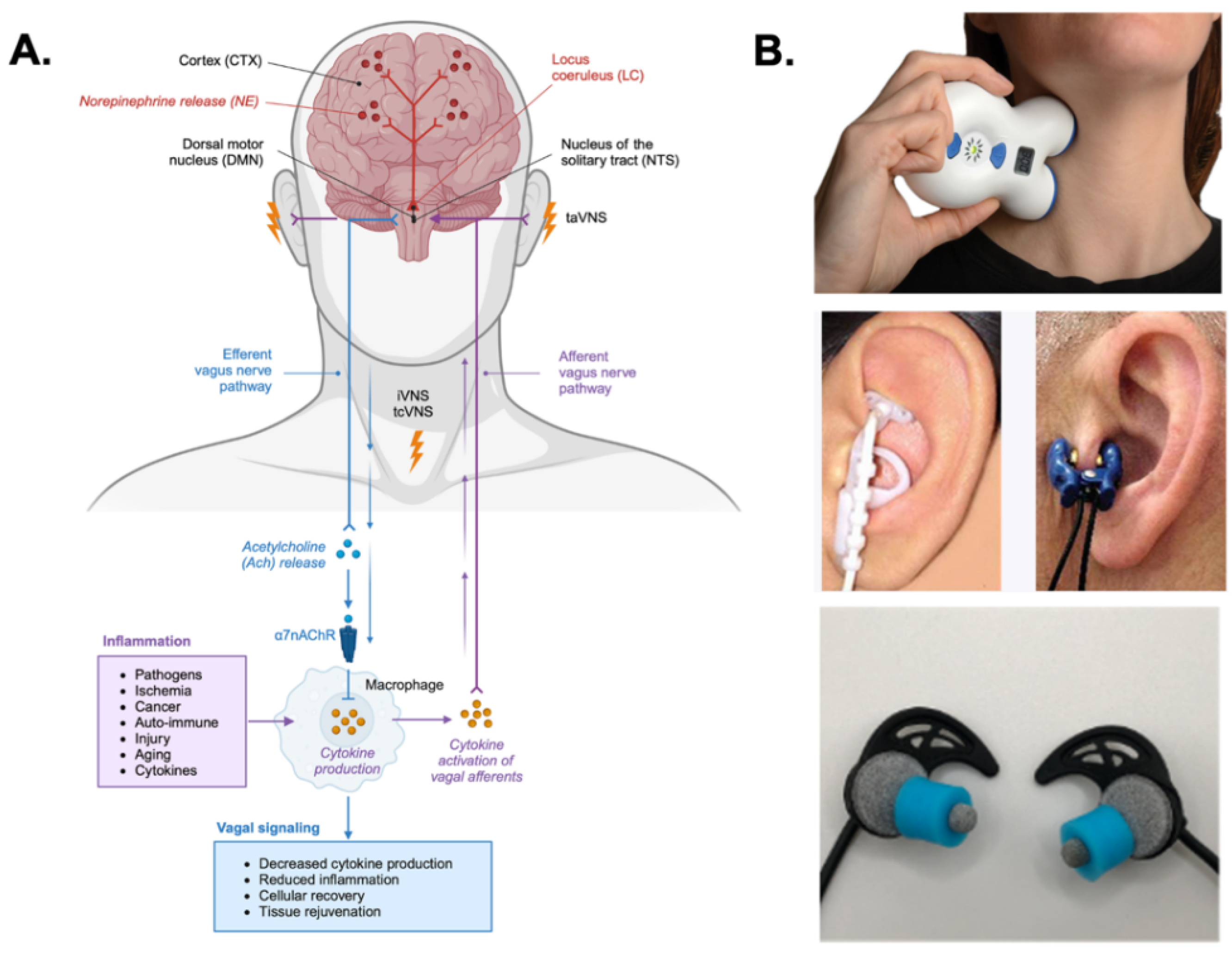

Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation

Central Pathway of VNS Through the NTS

Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Pathway (CAIP) and Cytokine Suppression

Stimulation Parameters, Comfort, and Feasibility in Survivors

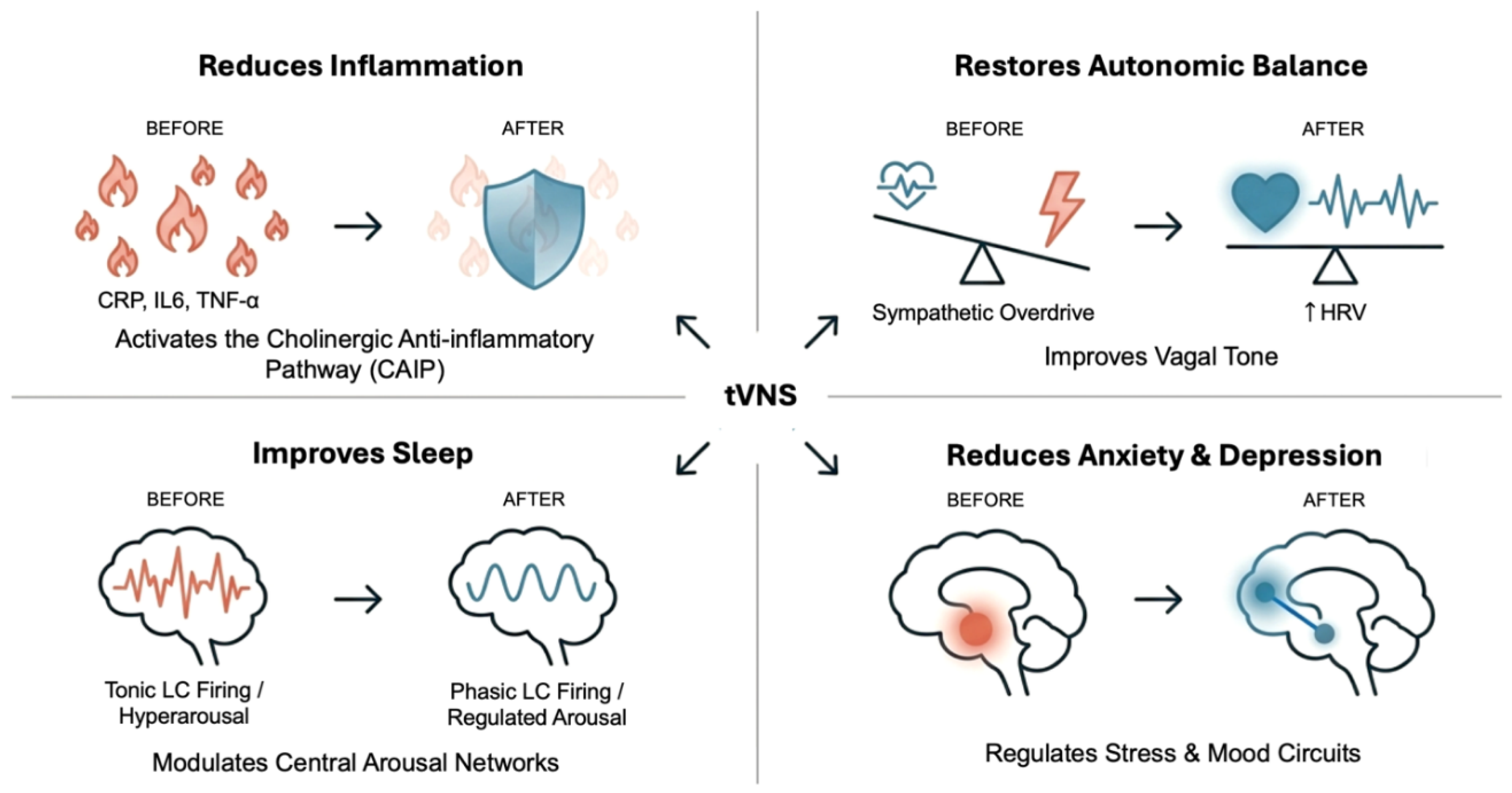

Effects of Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation on Symptom Cluster Outcomes across Clinical Indications

Inflammation

Insomnia

Anxiety and Depression

Pain and Nociceptive Disorder

Cancer-Related Fatigue (CRF)

VNS and Breast Cancer Biology

Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Generative AI Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So, W.K.W.; Law, B.M.H.; Ng, M.S.N.; He, X.; Chan, D.N.S.; Chan, C.W.H.; McCarthy, A.L. Symptom clusters experienced by breast cancer patients at various treatment stages: A systematic review. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 2531–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.; Cramarossa, G.; Bruner, D.; Chen, E.; Khan, L.; Leung, A.; Lutz, S.; Chow, E. A literature review of symptom clusters in patients with breast cancer. Expert Rev. Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2011, 11, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorentino, L.; Rissling, M.; Liu, L.; Ancoli-Israel, S. The Symptom Cluster of Sleep, Fatigue and Depressive Symptoms in Breast Cancer Patients: Severity of the Problem and Treatment Options. Drug Discovery Today. Dis. Models 2011, 8, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjerkeset, E.; Röhrl, K.; Schou-Bredal, I. Symptom cluster of pain, fatigue, and psychological distress in breast cancer survivors: prevalence and characteristics. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 180, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, J.; McDonald, R.; Zhang, L.; Verma, S.; Leahey, A.; Ecclestone, C.; Bedard, G.; Pulenzas, N.; Bhatia, A.; Chow, R.; et al. Quality of life (QOL) and symptom burden (SB) in patients with breast cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissane, D.W.; Grabsch, B.; Love, A.; Clarke, D.M.; Bloch, S.; Smith, G.C. Psychiatric Disorder in Women with Early Stage and Advanced Breast Cancer: a Comparative Analysis. Aust. New Zealand J. Psychiatry 2004, 38, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bultz, B.D. Patient Care and Outcomes: Why Cancer Care Should Screen for Distress, the 6th Vital Sign. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 3, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byar, K.L.; Berger, A.M.; Bakken, S.L.; Cetak, M.A. Impact of Adjuvant Breast Cancer Chemotherapy on Fatigue, Other Symptoms, and Quality of Life. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2006, 33, E18–E26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, D.C.; Shaffer, K.M.; Tiersten, A.; Holland, J. Physical Symptom Burden and Its Association With Distress, Anxiety, and Depression in Breast Cancer. Psychosomatics 2018, 59, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarenmalm, E.K.; Browall, M.; Gaston-Johansson, F. Symptom Burden Clusters: A Challenge for Targeted Symptom Management. A Longitud. Study Examining Symptom Burd. Clust. Breast Cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2014, 47, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, A.; Jacobs, J.; Haggett, D.; Jimenez, R.; Peppercorn, J. Evaluation and management of insomnia in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 181, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissane, D.W.; Ildn, J.; Bloch, S.; Vitetta, L.; Clarke, D.M.; Smith, G.C.; McKenzie, D.P. Psychological morbidity and quality of life in Australian women with early-stage breast cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Med. J. Aust. 1998, 169, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Li, W.; Tang, L.; Fan, X.; Yao, S.; Zhang, X.; Bi, Z.; Cheng, H. Depression in breast cancer patients: Immunopathogenesis and immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2022, 536, 215648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.K.; Oh, S.; Kim, J.; Choi, J.S.; Hwang, K.T. Psychological Impact of Type of Breast Cancer Surgery: A National Cohort Study. World J. Surg. 2022, 46, 2224–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Z.M.; Deal, A.M.; Nyrop, K.A.; Chen, Y.T.; Quillen, L.J.; Brenizer, T.; Muss, H.B. Serial Assessment of Depression and Anxiety by Patients and Providers in Women Receiving Chemotherapy for Early Breast Cancer. Oncol. 2021, 26, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savard, J.; Simard, S.; Blanchet, J.; Ivers, H.; Morin, C.M. Prevalence; Characteristics, C. and Risk Factors for Insomnia in the Context of Breast Cancer. Sleep 2001, 24, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, M.R. Depression and Insomnia in Cancer: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Effects on Cancer Outcomes. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2013, 15, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, S.; Sereika, S.; Harpel, C.; Diego, E.; Steiman, J.G.; McAuliffe, P.F.; Wesmiller, S. Factors associated with sleep disturbances in women undergoing treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, D.D.; Bashoura, L.; Sheshadri, A.; Manzullo, E.; Faiz, S.A. The Impact of Immunotherapy on Sleep and Circadian Rhythms in Patients with Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1295267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnant, M.; Fitzal, F.; Rinnerthaler, G.; Steger, G.G.; Greil-Ressler, S.; Balic, M.; Heck, D.; Jakesz, R.; Thaler, J.; Egle, D.; et al. Duration of Adjuvant Aromatase-Inhibitor Therapy in Postmenopausal Breast Cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shien, T.; Iwata, H. Adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 50, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, D.; Giese-Davis, J. Depression and cancer: mechanisms and disease progression. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrar, M.; Peddie, N.; Agnew, S.; Diserholt, A.; Fleming, L. Breast Cancer Survivors’ Lived Experience of Adjuvant Hormone Therapy: A Thematic Analysis of Medication Side Effects and Their Impact on Adherence. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 861198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanft, T.; Day, A.; Ansbaugh, S.; Armenian, S.; Baker, K.S.; Ballinger, T.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Dickinson, K.; Fairman, N.P.; Felciano, J.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Survivorship, Version 1.2023. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. JNCCN 2023, 21, 792–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollica, M.A.; McWhirter, G.; Tonorezos, E.; Fenderson, J.; Freyer, D.R.; Jefford, M.; Luevano, C.J.; Mullett, T.; Nasso, S.F.; Schilling, E.; et al. Developing national cancer survivorship standards to inform quality of care in the United States using a consensus approach. J. Cancer Surviv. 2024, 18, 1190–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefford, M.; Nekhlyudov, L.; Smith, A.L.; Chan, R.J.; Lai-Kwon, J.; Hart, N.H. Survivorship Care for People Affected by Advanced or Metastatic Cancer: Building on the Recent Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer-ASCO Standards and Practice Recommendations. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2025, 45, e471752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachman, D.R.; Barton, D.L.; Swetz, K.M.; Loprinzi, C.L. Troublesome Symptoms in Cancer Survivors: Fatigue, Insomnia, Neuropathy, and Pain. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 3687–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, L.; Ancoli-Israel, S. Insomnia and its treatment in women with breast cancer. Sleep Med. Rev. 2006, 10, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edinger, J.D.; Arnedt, J.T.; Bertisch, S.M.; Carney, C.E.; Harrington, J.J.; Lichstein, K.L.; Sateia, M.J.; Troxel, W.M.; Zhou, E.S.; Kazmi, U.; et al. Behavioral and psychological treatments for chronic insomnia disorder in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2021, 17, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, L.; Zachariae, R.; Caruso, R.; Palagini, L.; Campos-Ródenas, R.; Riba, M.B.; Lloyd-Williams, M.; Kissane, D.; Rodin, G.; McFarland, D.; et al. Insomnia in adult patients with cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline. ESMO Open 2023, 8, 102047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, E.; Salem, D.; Swift, J.K.; Ramtahal, N. Meta-analysis of dropout from cognitive behavioral therapy: Magnitude, timing, and moderators. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 83, 1108–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, J.M.; Merk, F.L.; Anderson, J.; Aggarwal, A.; Stark, L.J. Expanding Access to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Purposeful and Effective Model for Integration. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2024, 31, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraldes, V.; Caldeira, E.; Afonso, A.; Machado, F.; Amaro-Leal, Â.; Laranjo, S.; Rocha, I. Cardiovascular Dysautonomia in Patients with Breast Cancer. Open Cardiovasc. Med. J. 2022, 16, e187419242206271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagundes, C.P.; Murray, D.M.; Hwang, B.S.; Gouin, J.-P.; Thayer, J.F.; Sollers, J.J.; Shapiro, C.L.; Malarkey, W.B.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. Sympathetic and parasympathetic activity in cancer-related fatigue: More evidence for a physiological substrate in cancer survivors. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011, 36, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, A.; Koenig, J.; Bruns, B.; Bendszus, M.; Friederich, H.-C.; Simon, J.J. Brain activation and heart rate variability as markers of autonomic function under stress. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giese-Davis, J.; Wilhelm, F.H.; Tamagawa, R.; Palesh, O.; Neri, E.; Taylor, C.B.; Kraemer, H.C.; Spiegel, D. Higher vagal activity as related to survival in patients with advanced breast cancer: an analysis of autonomic dysregulation. Psychosom. Med. 2015, 77, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Fu, W. Heart rate variability in the prediction of survival in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 89, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricon-Becker, I.; Fogel, E.; Cole, S.W.; Haldar, R.; Lev-Ari, S.; Gidron, Y. Tone it down: Vagal nerve activity is associated with pro-inflammatory and anti-viral factors in breast cancer – An exploratory study. Compr. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 7, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aston-Jones, G.; Cohen, J.D. AN INTEGRATIVE THEORY OF LOCUS COERULEUS-NOREPINEPHRINE FUNCTION: Adaptive Gain and Optimal Performance. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2005, 28, 403–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, L.; Boddington, L.; Steffan, P.J.; McCormick, D. Vagus nerve stimulation induces widespread cortical and behavioral activation. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, 2088–2098.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, F.A.; Chavan, S.S.; Miljko, S.; Grazio, S.; Sokolovic, S.; Schuurman, P.R.; Mehta, A.D.; Levine, Y.A.; Faltys, M.; Zitnik, R.; et al. Vagus nerve stimulation inhibits cytokine production and attenuates disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, 8284–8289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, L.; Yang, Y.; Chi, M.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Ouyang, W.; Li, W.; He, L.; Wei, T. Diagnostic role of heart rate variability in breast cancer and its relationship with peripheral serum carcinoembryonic antigen. PloS One 2023, 18, e0282221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-B.; Lai, H.-Z.; Long, J.; Ma, Q.; Fu, X.; You, F.-M.; Xiao, C. Vagal nerve activity and cancer prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, B.W.; Austelle, C.W. The Future Is Noninvasive: A Brief Review of the Evolution and Clinical Utility of Vagus Nerve Stimulation. Focus (Am. Psychiatr. Publ. ) 2022, 20, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmati, P.R.; Abd-Elsayed, A.; Staats, P.S.; Bautista, A. Noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation: History, mechanisms, indications, and obstacles. In Vagus Nerve Stimulation; Elsevier, 2025; pp. 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Afra, P.; Adamolekun, B.; Aydemir, S.; Watson, G.D.R. Evolution of the Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) Therapy System Technology for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy. Front. Med. Technol. 2021, 3, 696543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Wu, M.; Li, L.; Rong, P. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulators: a review of past, present, and future devices. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2022, 19, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redgrave, J.; Day, D.; Leung, H.; Laud, P.J.; Ali, A.; Lindert, R.; Majid, A. Safety and tolerability of Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve stimulation in humans; a systematic review. Brain Stimul. 2018, 11, 1225–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullahi, A.; Wong, T.W.L.; Ng, S.S.M. Putative role of non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation in cancer pathology and immunotherapy: Can this be a hidden treasure, especially for the elderly? Cancer Medicine 2023, 12, 19081–19090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, J.Y.Y.; Keatch, C.; Lambert, E.; Woods, W.; Stoddart, P.R.; Kameneva, T. Critical Review of Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation: Challenges for Translation to Clinical Practice. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austelle, C.W.; O’Leary, G.H.; Thompson, S.; Gruber, E.; Kahn, A.; Manett, A.J.; Short, B.; Badran, B.W. A Comprehensive Review of Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Depression. Neuromodulation: Technol. Neural Interface 2022, 25, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magoun, H.W. AN ASCENDING RETICULAR ACTIVATING SYSTEM IN THE BRAIN STEM. Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry 1952, 67, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbin, M.A.; Lafe, C.W.; Simpson, T.W.; Wittenberg, G.F.; Chandrasekaran, B.; Weber, D.J. Electrical stimulation of the external ear acutely activates noradrenergic mechanisms in humans. Brain Stimul. 2021, 14, 990–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, J.-H.; Nahas, Z.; Lomarev, M.; Denslow, S.; Lorberbaum, J.P.; Bohning, D.E.; George, M.S. A review of functional neuroimaging studies of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). Journal of Psychiatric Research 2003, 37, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Lu, K.-H.; Powley, T.L.; Liu, Z. Vagal nerve stimulation triggers widespread responses and alters large-scale functional connectivity in the rat brain. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0189518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jung, H.R.; Kim, J.B.; Kim, D.-J. Autonomic Dysfunction in Sleep Disorders: From Neurobiological Basis to Potential Therapeutic Approaches. J. Clin. Neurol. 2022, 18, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangos, E.; Ellrich, J.; Komisaruk, B.R. Non-invasive Access to the Vagus Nerve Central Projections via Electrical Stimulation of the External Ear: fMRI Evidence in Humans. Brain Stimul. 2015, 8, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clancy, J.A.; Mary, D.A.; Witte, K.K.; Greenwood, J.P.; Deuchars, S.A.; Deuchars, J. Non-invasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Healthy Humans Reduces Sympathetic Nerve Activity. Brain Stimul. 2014, 7, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Silberstein, S.D. Vagus Nerve and Vagus Nerve Stimulation, a Comprehensive Review: Part I. Headache: J. Head Face Pain 2016, 56, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, M.; Evancho, A.; Tyler, W.J. Bilateral transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of insomnia in breast cancer. Scientific Reports 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austelle, C.W.; Cox, S.S.; Wills, K.E.; Badran, B.W. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS): recent advances and future directions. Clin. Auton. Res.: Off. J. Clin. Auton. Res. Soc. 2024, 34, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, S.-Y.; Rohan, K.J.; Parent, J.; Tager, F.A.; McKinley, P.S. A Longitudinal Study of Depression, Fatigue, and Sleep Disturbances as a Symptom Cluster in Women With Breast Cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2015, 49, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Barsevick, A.M.; Tulman, L.; McDermott, P.A. Treatment-Related Symptom Clusters in Breast Cancer: A Secondary Analysis. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2008, 36, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, M.J.; Miaskowski, C.; Paul, S.M. Symptom clusters and their effect on the functional status of patients with cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2001, 28, 465–470. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, M.J.; Cho, M.H.; Cooper, B.A.; Miaskowski, C. The effect of symptom clusters on functional status and quality of life in women with breast cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2010, 14, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.-P.; Von Ah, D.; Chen, M.-K.; Saligan, L.N. Relationship of cancer-related fatigue with psychoneurophysiological (PNP) symptoms in breast cancer survivors. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 68, 102469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, A.M.; Visovsky, C.; Hertzog, M.; Holtz, S.; Loberiza, F.R. Usual and Worst Symptom Severity and Interference With Function in Breast Cancer Survivors. J. Support. Oncol. 2012, 10, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbestad, F.E.; Ammitzbøll, G.; Horsbøll, T.A.; Andersen, I.; Johansen, C.; Zehran, B.; Dalton, S.O. The long-term burden of a symptom cluster and association with longitudinal physical and emotional functioning in breast cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2023, 62, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnew, S.; Crawford, M.; MacPherson, I.; Shiramizu, V.; Fleming, L. The impact of symptom clusters on endocrine therapy adherence in patients with breast cancer. Breast 2024, 75, 103731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miaskowski, C.; Barsevick, A.; Berger, A.; Casagrande, R.; Grady, P.A.; Jacobsen, P.; Kutner, J.; Patrick, D.; Zimmerman, L.; Xiao, C.; et al. Advancing Symptom Science Through Symptom Cluster Research: Expert Panel Proceedings and Recommendations. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109, djw253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, J.E. The role of neuro-immune interactions in cancer-related fatigue: Biobehavioral risk factors and mechanisms. Cancer 2019, 125, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, J.E. Cancer-related fatigue—mechanisms; risk factors, and treatments. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 11, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potosky, A.L.; Graves, K.D.; Lin, L.; Pan, W.; Fall-Dickson, J.M.; Ahn, J.; Ferguson, K.M.; Keegan, T.H.M.; Paddock, L.E.; Wu, X.-C.; et al. The prevalence and risk of symptom and function clusters in colorectal cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv.: Res. Pract. 2022, 16, 1449–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.L.; Dickinson, K.; Hsiao, C.-P.; Lukkahatai, N.; Gonzalez-Marrero, V.; McCabe, M.; Saligan, L.N. Biological Basis for the Clustering of Symptoms. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 32, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.-H.; Li, J.-R.; Feng, Y.; Li, S.-W.; Qiu, H.; Hong, J.-F. The Association Between Sleep Disturbance and Proinflammatory Markers in Patients With Cancer: A Meta-analysis. Cancer Nursing 2023, 46, E91–E98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Tan, X.; Tang, C. Estrogen-immuno-neuromodulation disorders in menopausal depression. J. Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-N.; Dantzer, R.; Langley, K.E.; Bennett, G.J.; Dougherty, P.M.; Dunn, A.J.; Meyers, C.A.; Miller, A.H.; Payne, R.; Reuben, J.M.; et al. A Cytokine-Based Neuroimmunologic Mechanism of Cancer-Related Symptoms. Neuroimmunomodulation 2004, 11, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleeland, C.S.; Bennett, G.J.; Dantzer, R.; Dougherty, P.M.; Dunn, A.J.; Meyers, C.A.; Miller, A.H.; Payne, R.; Reuben, J.M.; Wang, X.S.; et al. Are the symptoms of cancer and cancer treatment due to a shared biologic mechanism?: A cytokine-immunologic model of cancer symptoms. Cancer 2003, 97, 2919–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, M.R.; Olmstead, R.; Carroll, J.E.; Disturbance, S.; Duration, S. and Inflammation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies and Experimental Sleep Deprivation. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 80, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H.; Ancoli-Israel, S.; Bower, J.E.; Capuron, L.; Irwin, M.R. Neuroendocrine-Immune Mechanisms of Behavioral Comorbidities in Patients With Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 971–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, A.; Allavena, P.; Sica, A.; Balkwill, F.; Nature, C.-R.I. 2008, 454, 436–444. [PubMed]

- Grivennikov, S.I.; Greten, F.R.; Karin, M. Immunity, Inflammation, and Cancer. Cell 2010, 140, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajj, A.; Chamoun, R.; Salameh, P.; Khoury, R.; Hachem, R.; Sacre, H.; Chahine, G.; Kattan, J.; Khabbaz, L.R. Fatigue in breast cancer patients on chemotherapy: a cross-sectional study exploring clinical, biological, and genetic factors. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janelsins, M.C.; Heckler, C.E.; Peppone, L.J.; Kamen, C.; Mustian, K.M.; Mohile, S.G.; Magnuson, A.; Kleckner, I.R.; Guido, J.J.; Young, K.L.; et al. Cognitive Complaints in Survivors of Breast Cancer After Chemotherapy Compared With Age-Matched Controls: An Analysis From a Nationwide, Multicenter, Prospective Longitudinal Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, K.J. The inflammatory reflex. Nature 2002, 420, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoski, S.G.; Jones, L.W.; Krone, R.J.; Stein, P.K.; Scott, J.M. Autonomic dysfunction in early breast cancer: Incidence, clinical importance, and underlying mechanisms. Am. Heart J. 2015, 170, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.-F.; Jin, F.-J.; Li, N.; Guan, H.-T.; Lan, L.; Ni, H.; Wang, Y. Adrenergic receptor β2 activation by stress promotes breast cancer progression through macrophages M2 polarization in tumor microenvironment. BMB Rep. 2015, 48, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosswell, A.D.; Lockwood, K.G.; Ganz, P.A.; Bower, J.E. Low heart rate variability and cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 45, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloter, E.; Barrueto, K.; Klein, S.D.; Scholkmann, F.; Wolf, U. Heart Rate Variability as a Prognostic Factor for Cancer Survival – A Systematic Review. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro-Morán, E.; Fernández-Lao, C.; Galiano-Castillo, N.; Cantarero-Villanueva, I.; Arroyo-Morales, M.; Díaz-Rodríguez, L. Heart Rate Variability in Breast Cancer Survivors After the First Year of Treatments: A Case-Controlled Study. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2016, 18, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arab, C.; Dias, D.P.M.; Barbosa, R.T.D.A.; Carvalho, T.D.D.; Valenti, V.E.; Crocetta, T.B.; Ferreira, M.; Abreu, L.C.D.; Ferreira, C. Heart rate variability measure in breast cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 68, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvinen, K.H.; Murray, N.P.; Arastu, H.; Allison, R.R.; Reactivity, S.; Behaviors, H. Compliance to Medical Care in Breast Cancer Survivors. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2013, 40, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, M.R.; Cole, S.W. Reciprocal regulation of the neural and innate immune systems. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, T.M.; McKinley, P.S.; Seeman, T.E.; Choo, T.-H.; Lee, S.; Sloan, R.P. Heart rate variability predicts levels of inflammatory markers: Evidence for the vagal anti-inflammatory pathway. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 49, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, J.; Rupprecht, S.; Künstler, E.C.S.; Hoyer, D. Heart rate variability as a marker and predictor of inflammation, nosocomial infection, and sepsis – A systematic review. Auton. Neurosci. 2023, 249, 103116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan, R.P.; McCreath, H.; Tracey, K.J.; Sidney, S.; Liu, K.; Seeman, T. RR Interval Variability Is Inversely Related to Inflammatory Markers: The CARDIA Study. Mol. Med. 2007, 13, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Yu, K.; Xu, S.; Qiu, P.; Lyu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y. Chronic stress-induced immune dysregulation in breast cancer: Implications of psychosocial factors. J. Transl. Intern. Med. 2023, 11, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, K.; Mao, J.J.; Su, I.; DeMichele, A.; Li, Q.; Xie, S.X.; Gehrman, P.R. Prevalence and risk factors for insomnia among breast cancer patients on aromatase inhibitors. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bower, J.E.; Radin, A.; Ganz, P.A.; Irwin, M.R.; Cole, S.W.; Petersen, L.; Asher, A.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Crespi, C.M. Inflammation and dimensions of fatigue in women with early stage breast cancer: A longitudinal examination. Cancer 2025, 131, e70038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddick, B.K.; Nanda, J.P.; Campbell, L.; Ryman, D.G.; Gaston-Johansson, F. Examining the Influence of Coping with Pain on Depression, Anxiety, and Fatigue Among Women with Breast Cancer. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2005, 23, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, P.L.; Buysse, D.J. Sleep disturbances and depression: risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2008, 10, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslau, N.; Roth, T.; Rosenthal, L.; Andreski, P. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: A longitudinal epidemiological study of young Adults. Biol. Psychiatry 1996, 39, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, B.W.; Mithoefer, O.J.; Summer, C.E.; LaBate, N.T.; Glusman, C.E.; Badran, A.W.; DeVries, W.H.; Summers, P.M.; Austelle, C.W.; McTeague, L.M.; et al. Short trains of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) have parameter-specific effects on heart rate. Brain Stimul. 2018, 11, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilz, M.J. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation - A brief introduction and overview. Auton. Neurosci. 2022, 243, 103038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, W.J. Auricular bioelectronic devices for health, medicine, and human-computer interfaces. Front. Electron. 2025, 6, 1503425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, E.R.; Neumann, H.; Knutzen, S.M.; Henriksen, E.N.; Amidi, A.; Johansen, C.; von Heymann, A.; Christiansen, P.; Zachariae, R. Interventions for insomnia in cancer patients and survivors-a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024, 8, pkae041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, J.R.; MacLean, A.W.; Brundage, M.D.; Schulze, K. Sleep disturbance in cancer patients. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 54, 1309–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockefeer, J.P.M.; De Vries, J. What is the relationship between trait anxiety and depressive symptoms, fatigue, and low sleep quality following breast cancer surgery? Psycho-Oncol. 2013, 22, 1127–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palesh, O.; Aldridge-Gerry, A.; Ulusakarya, A.; Ortiz-Tudela, E.; Capuron, L.; Innominato, P.F. Sleep Disruption in Breast Cancer Patients and Survivors. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2013, 11, 1523–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palesh, O.; Aldridge-Gerry, A.; Zeitzer, J.M.; Koopman, C.; Neri, E.; Giese-Davis, J.; Jo, B.; Kraemer, H.; Nouriani, B.; Spiegel, D. Actigraphy-Measured Sleep Disruption as a Predictor of Survival among Women with Advanced Breast Cancer. Sleep 2014, 37, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, C.; Nouriani, B.; Erickson, V.; Anupindi, R.; Butler, L.D.; Bachmann, M.H.; Sephton, S.E.; Spiegel, D. Sleep Disturbances in Women With Metastatic Breast Cancer. Breast J. 2002, 8, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortner, B.V.; Stepanski, E.J.; Wang, S.C.; Kasprowicz, S.; Durrence, H.H. Sleep and Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2002, 24, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliff, C.G.; Zepeda, S.G.; Hall, M.H.; Tullos, E.A.; Fowler, S.; Chaoul, A.; Spelman, A.; Arun, B.; Cohen, L. Patient characteristics associated with sleep disturbance in breast cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 2601–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzierzewski, J.M.; Donovan, E.K.; Kay, D.B.; Sannes, T.S.; Bradbrook, K.E. Sleep Inconsistency and Markers of Inflammation. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, M.R.; Olmstead, R.; Bjurstrom, M.F.; Finan, P.H.; Smith, M.T. Sleep disruption and activation of cellular inflammation mediate heightened pain sensitivity: a randomized clinical trial. Pain 2023, 164, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, M.R.; Opp, M.R. Sleep Health: Reciprocal Regulation of Sleep and Innate Immunity. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 129–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, J.M. The role of cytokines in sleep regulation. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008, 14, 3408–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnet, M.H.; Arand, D.L. Hyperarousal and insomnia: State of the science. Sleep Med. Rev. 2010, 14, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglis, M.G. Autonomic dysfunction in primary sleep disorders. Sleep Med. 2016, 19, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, A.; Bozzali, M. Potential Interactions between the Autonomic Nervous System and Higher Level Functions in Neurological and Neuropsychiatric Conditions. Frontiers in Neurology 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoccoli, G.; Amici, R. Sleep and autonomic nervous system. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2020, 15, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-C.; Zhang, J.; Thayer, J.F.; Mednick, S.C. Understanding the roles of central and autonomic activity during sleep in the improvement of working memory and episodic memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2022, 119, e2123417119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann, D.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Feige, B.; Voderholzer, U.; Berger, M.; Perlis, M.; Nissen, C. The hyperarousal model of insomnia: A review of the concept and its evidence. Sleep Med. Rev. 2010, 14, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Substance, A.; Services, A.M.H. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. In Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Krebber, A.M.H.; Buffart, L.M.; Kleijn, G.; Riepma, I.C.; De Bree, R.; Leemans, C.R.; Becker, A.; Brug, J.; Van Straten, A.; Cuijpers, P.; et al. Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: a meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psycho-Oncol. 2014, 23, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsaras, K.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Mitsi, D.; Veneti, A.; Kelesi, M.; Zyga, S.; Fradelos, E.C. Assessment of Depression and Anxiety in Breast Cancer Patients: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev.: APJCP 2018, 19, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar]

- Bower, J.E. Behavioral Symptoms in Patients With Breast Cancer and Survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.L.; Jeong, S.M.; Jeon, K.H.; Kim, B.; Jung, W.; Jeong, A.; Han, K.; Shin, D.W. Depression risk among breast cancer survivors: a nationwide cohort study in South Korea. Breast Cancer Res. 2024, 26, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biparva, A.J.; Raoofi, S.; Rafiei, S.; Masoumi, M.; Doustmehraban, M.; Bagheribayati, F.; Shahrebabak, E.S.V.; Mejareh, Z.N.; Khani, S.; Abdollahi, B.; et al. Global depression in breast cancer patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0287372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessami, A.; Ghadirzadeh, E.; Ashrafi, S.; Taghavi, F.; Elyasi, F.; Gheibi, M.; Zaboli, E.; Alizadeh-Navaei, R.; Gelvardi, F.A.; Hedayatizadeh-Omran, A.; et al. Depression, anxiety, and stress in breast cancer patients: prevalence, associated risk factors, and clinical correlates. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, M.; Lesur, A.; Perdrizet-Chevallier, C. Depression, quality of life and breast cancer: a review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2008, 110, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giese-Davis, J.; Wilhelm, F.H.; Conrad, A.; Abercrombie, H.C.; Sephton, S.; Yutsis, M.; Neri, E.; Taylor, C.B.; Kraemer, H.C.; Spiegel, D. Depression and Stress Reactivity in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Psychosom. Med. 2006, 68, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, N.; Zhong, L.; Wang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, B.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Z. Prognostic value of depression and anxiety on breast cancer recurrence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 282,203 patients. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 3186–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.; Haviland, J.; Greer, S.; Davidson, J.; Bliss, J. Influence of psychological response on survival in breast cancer: a population-based cohort study. Lancet 1999, 354, 1331–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, F.; Vanderpool, R.C.; McLouth, L.E.; Romond, E.H.; Chen, Q.; Durbin, E.B.; Tucker, T.C.; Tai, E.; Huang, B. Influence of depression on breast cancer treatment and survival: A Kentucky population-based study. Cancer 2023, 129, 1821–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, N.G.; Cohen-Woods, S.; Balfour, D.A.; Burt, M.G.; Waterman, A.L.; Koczwara, B. Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Dysfunction in People With Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e70366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.H.; Rizvi, M.A.; Fatima, M.; Mondal, A.C. Pathophysiological implications of neuroinflammation mediated HPA axis dysregulation in the prognosis of cancer and depression. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2021, 520, 111093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosain, R.; Gage-Bouchard, E.; Ambrosone, C.; Repasky, E.; Gandhi, S. Stress reduction strategies in breast cancer: review of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic based strategies. Semin. Immunopathol. 2020, 42, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, M.; Thayer, J. How heart rate variability affects emotion regulation brain networks. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2018, 19, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thayer, J.F.; Lane, R.D. A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation and dysregulation. J. Affect. Disord. 2000, 61, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaz, B.; Sinniger, V.; Pellissier, S. The Vagus Nerve in the Neuro-Immune Axis: Implications in the Pathology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, V.A.; Tracey, K.J. The vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex—linking immunity and metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sălcudean, A.; Bodo, C.-R.; Popovici, R.-A.; Cozma, M.-M.; Păcurar, M.; Crăciun, R.-E.; Crisan, A.-I.; Enatescu, V.-R.; Marinescu, I.; Cimpian, D.-M.; et al. Neuroinflammation-A Crucial Factor in the Pathophysiology of Depression-A Comprehensive Review. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Casado, A.; Álvarez-Bustos, A.; De Pedro, C.G.; Méndez-Otero, M.; Romero-Elías, M. Cancer-related Fatigue in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Review. Clin. Breast Cancer 2021, 21, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.-R.; Nackley, A.; Huh, Y.; Terrando, N.; Maixner, W. Neuroinflammation and Central Sensitization in Chronic and Widespread Pain. Anesthesiology 2018, 129, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, J.; Jarczok, M.N.; Ellis, R.J.; Hillecke, T.K.; Thayer, J.F. Heart rate variability and experimentally induced pain in healthy adults: A systematic review. Eur. J. Pain 2014, 18, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, M.A.; Stokes, S.; Regina, F.; Susko, K.; Hendry, W.; Anderson, A.; Sofge, J.; Ginsberg, J.; Burch, J. Heart rate variability (HRV) training for symptom control in cancer survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 148–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, G.; Favieri, F.; Leemhuis, E.; De Martino, M.L.; Giannini, A.M.; De Gennaro, L.; Casagrande, M.; Pazzaglia, M. Ear your heart: transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on heart rate variability in healthy young participants. PeerJ 2022, 10, e14447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spada, G.E.; Masiero, M.; Pizzoli, S.F.M.; Pravettoni, G. Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback in Cancer Patients: A Scoping Review. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, A.M.; Mooney, K.; Alvarez-Perez, A.; Breitbart, W.S.; Carpenter, K.M.; Cella, D.; Cleeland, C.; Dotan, E.; Eisenberger, M.A.; Escalante, C.P.; et al. Cancer-Related Fatigue, Version 2.2015. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2015, 13, 1012–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palagini, L.; Miniati, M.; Riemann, D.; Zerbinati, L. Insomnia; Fatigue, and Depression: Theoretical and Clinical Implications of a Self-reinforcing Feedback Loop in Cancer. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2021, 17, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, W.J.; Boasso, A.M.; Mortimore, H.M.; Silva, R.S.; Charlesworth, J.D.; Marlin, M.A.; Aebersold, K.; Aven, L.; Wetmore, D.Z.; Pal, S.K. Transdermal neuromodulation of noradrenergic activity suppresses psychophysiological and biochemical stress responses in humans. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.; Yang, M.-H.; Zhang, G.-Z.; Wang, X.-X.; Li, B.; Li, M.; Woelfer, M.; Walter, M.; Wang, L. Neural networks and the anti-inflammatory effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation in depression. J. Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, N.; Mudge, J.D.; Kasole, M.; Chen, R.C.; Blanz, S.L.; Trevathan, J.K.; Lovett, E.G.; Williams, J.C.; Ludwig, K.A. Auricular Vagus Neuromodulation—A Systematic Review on Quality of Evidence and Clinical Effects. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 664740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peuker, E.T.; Filler, T.J. The nerve supply of the human auricle. Clin. Anat. 2002, 15, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, P.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, R.; Fang, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.; Vangel, M.; Sun, S.; et al. Effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on major depressive disorder: A nonrandomized controlled pilot study. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 195, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, H.; Kreiselmeyer, G.; Kerling, F.; Kurzbuch, K.; Rauch, C.; Heers, M.; Kasper, B.S.; Hammen, T.; Rzonsa, M.; Pauli, E.; et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (t-VNS) in pharmacoresistant epilepsies: A proof of concept trial. Epilepsia 2012, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazzi, L.; Usai, S.; Bussone, G.; EHMTI-0036. Gammacore device for treatment of migraine attack: preliminary report. J. Headache Pain 2014, 15, G12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naritoku, D.K.; Terry, W.J.; Helfert, R.H. Regional induction of fos immunoreactivity in the brain by anticonvulsant stimulation of the vagus nerve. Epilepsy Res. 1995, 22, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulsey, D.R.; Riley, J.R.; Loerwald, K.W.; Rennaker, R.L.; Kilgard, M.P.; Hays, S.A. Parametric characterization of neural activity in the locus coeruleus in response to vagus nerve stimulation. Exp. Neurol. 2017, 289, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Egroo, M.; Koshmanova, E.; Vandewalle, G.; Jacobs, H.I.L. Importance of the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system in sleep-wake regulation: Implications for aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep Med. Rev. 2022, 62, 101592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aston-Jones, G.; Rajkowski, J.; Cohen, J. Role of locus coeruleus in attention and behavioral flexibility. Biol. Psychiatry 1999, 46, 1309–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.E.; Yizhar, O.; Chikahisa, S.; Nguyen, H.; Adamantidis, A.; Nishino, S.; Deisseroth, K.; De Lecea, L. Tuning arousal with optogenetic modulation of locus coeruleus neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2010, 13, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, M.H.; Nakamura, Y.; Clemente, C.D.; Sterman, M.B. Afferent vagal stimulation: Neurographic correlates of induced eeg synchronization and desynchronization. Brain Res. 1967, 5, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, M.H.; Nakamura, Y. EEG response to afferent abdominal vagal stimulation. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1968, 24, 396. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrakowski, P.; Blaszkiewicz, M.; Skalski, S. Changes in the Electrical Activity of the Brain in the Alpha and Theta Bands during Prayer and Meditation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurel, N.Z.; Wittbrodt, M.T.; Jung, H.; Shandhi, M.M.H.; Driggers, E.G.; Ladd, S.L.; Huang, M.; Ko, Y.-A.; Shallenberger, L.; Beckwith, J.; et al. Transcutaneous cervical vagal nerve stimulation reduces sympathetic responses to stress in posttraumatic stress disorder: A double-blind, randomized, sham controlled trial. Neurobiol. Stress 2020, 13, 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moazzami, K.; Pearce, B.D.; Gurel, N.Z.; Wittbrodt, M.T.; Levantsevych, O.M.; Huang, M.; Shandhi, M.M.H.; Herring, I.; Murrah, N.; Driggers, E.; et al. Transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation modulates stress-induced plasma ghrelin levels: A double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 342, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, A.; Fischer, R.; Borges, U.; Laborde, S.; Achtzehn, S.; Liepelt, R. The effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) on cognitive control in multitasking. Neuropsychologia 2023, 187, 108614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifilio, E.; Shortell, D.; Olshan, S.; O’Neal, A.; Coyne, J.; Lamb, D.; Porges, E.; Williamson, J. Impact of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation on healthy cognitive and brain aging. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1184051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeska, C.; Klepzig, K.; Hamm, A.O.; Weymar, M. Ready for translation: non-invasive auricular vagus nerve stimulation inhibits psychophysiological indices of stimulus-specific fear and facilitates responding to repeated exposure in phobic individuals. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billman, G.E. Heart Rate Variability ? A Historical Perspective. Front. Physiol. 2011, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Paso, G.A.R.; Langewitz, W.; Mulder, L.J.M.; Van Roon, A.; Duschek, S. The utility of low frequency heart rate variability as an index of sympathetic cardiac tone: A review with emphasis on a reanalysis of previous studies. Psychophysiology 2013, 50, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.S.; Bentho, O.; Park, M.-Y.; Sharabi, Y. Low-frequency power of heart rate variability is not a measure of cardiac sympathetic tone but may be a measure of modulation of cardiac autonomic outflows by baroreflexes: Low-frequency power of heart rate variability. Exp. Physiol. 2011, 96, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, E.R.; Szabadi, E. Functional neuroanatomy of the noradrenergic locus coeruleus: its roles in the regulation of arousal and autonomic function part I: principles of functional organisation. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2008, 6, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, W.J.; Wyckoff, S.; Hearn, T.; Hool, N. The Safety and Efficacy of Transdermal Auricular Vagal Nerve Stimulation Earbud Electrodes for Modulating Autonomic Arousal, Attention, Sensory Gating, and Cortical Brain Plasticity in Humans. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Tu, S.; Sheng, J.; Shao, A. Depression in sleep disturbance: A review on a bidirectional relationship, mechanisms and treatment. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 2324–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagundes, C.P.; Brown, R.L.; Chen, M.A.; Murdock, K.W.; Saucedo, L.; LeRoy, A.; Wu, E.L.; Garcini, L.M.; Shahane, A.D.; Baameur, F.; et al. Grief depressive symptoms, and inflammation in the spousally bereaved. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 100, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, T.M.; Schatzberg, A.F. On the Interactions of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis and Sleep: Normal HPA Axis Activity and Circadian Rhythm, Exemplary Sleep Disorders. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 3106–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Gao, G.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; et al. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation at 20 Hz Improves Depression-Like Behaviors and Down-Regulates the Hyperactivity of HPA Axis in Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress Model Rats. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paredes, E.C.; Goyes, D.; Mak, S.; Yardimian, R.; Ortiz, N.; McLaren, A.; Stauss, H.M. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation inhibits mental stress-induced cortisol release—Potential implications for inflammatory conditions. Physiol. Rep. 2025, 13, e70251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, R.; Wong, J.; Cerami, K.; Viegas, A.; Chen, M.; Kania, A.; Stauss, H. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation may elicit anti-inflammatory actions through activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in humans. Physiology 2023, 38, 5734481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, M.N.; Pearce, B.D.; Biron, C.A.; Miller, A.H. Immune modulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis during viral infection. Viral Immunol. 2005, 18, 41–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, C.R.; Xiong, W. The Mechanism of Action of Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Treatment-Resistant Depression. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 2018, 41, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howells, F.M.; Stein, D.J.; Russell, V.A. Synergistic tonic and phasic activity of the locus coeruleus norepinephrine (LC-NE) arousal system is required for optimal attentional performance. Metab. Brain Dis. 2012, 27, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.D.; Wittbrodt, M.T.; Gurel, N.Z.; Shandhi, M.H.; Gazi, A.H.; Jiao, Y.; Levantsevych, O.M.; Huang, M.; Beckwith, J.; Herring, I.; et al. Transcutaneous Cervical Vagal Nerve Stimulation in Patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): A Pilot Study of Effects on PTSD Symptoms and Interleukin-6 Response to Stress. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 6, 100190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Cai, T.; Li, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhao, X.; Wu, D.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation reduces cytokine production in sepsis: An open double-blind, sham-controlled, pilot study. Brain Stimul. 2023, 16, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, M.; Akan, A.; Mueller, M.R. Transcutaneous Stimulation of Auricular Branch of the Vagus Nerve Attenuates the Acute Inflammatory Response After Lung Lobectomy. World J. Surg. 2020, 44, 3167–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, T.; Szeles, J.C.; Kitzberger, R.; Holbik, J.; Grieb, A.; Wolf, H.; Akyaman, H.; Lucny, F.; Tychera, A.; Neuhold, S.; et al. Percutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Reduces Inflammation in Critical Covid-19 Patients. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 897257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynan, A.; Brines, M.; Chavan, S.S. Control of inflammation using non-invasive neuromodulation: past, present and promise. Int. Immunol. 2022, 34, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.-J.; Wu, J.; Gong, L.-J.; Yang, H.-S.; Chen, H. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation in anti-inflammatory therapy: mechanistic insights and future perspectives. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1490300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhong, Z.; Li, J.; Feng, Y. Efficacy of transauricular vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: a randomized controlled exploratory study. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 45, 2289–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falvey, A. Vagus nerve stimulation and inflammation: expanding the scope beyond cytokines. Bioelectron. Med. 2022, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazoukis, G.; Stavrakis, S.; Armoundas, A.A. Vagus Nerve Stimulation and Inflammation in Cardiovascular Disease: A State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e030539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.L.; O’Leary, G.H.; Austelle, C.W.; Gruber, E.; Kahn, A.T.; Manett, A.J.; Short, B.; Badran, B.W. A Review of Parameter Settings for Invasive and Non-invasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) Applied in Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 709436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forte, G.; Troisi, G.; Pazzaglia, M.; Pascalis, V.D.; Casagrande, M. Heart Rate Variability and Pain: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniusas, E.; Kampusch, S.; Tittgemeyer, M.; Panetsos, F.; Gines, R.F.; Papa, M.; Kiss, A.; Podesser, B.; Cassara, A.M.; Tanghe, E.; et al. Current Directions in the Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation I – A Physiological Perspective. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, M.F.; Albusoda, A.; Farmer, A.D.; Aziz, Q. The anatomical basis for transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation. J. Anat. 2020, 236, 588–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Fujiwara, T. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation in healthy individuals, stroke, and Parkinson’s disease: a narrative review of safety, parameters, and efficacy. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, A.Y.; Marduy, A.; de Melo, P.S.; Gianlorenco, A.C.; Kim, C.K.; Choi, H.; Song, J.J.; Fregni, F. Safety of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 22055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austelle, C.W.; Sege, C.T.; Kahn, A.T.; Gregoski, M.J.; Taylor, D.L.; McTeague, L.M.; Short, E.B.; Badran, B.W.; George, M.S. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Attenuates Early Increases in Heart Rate Associated With the Cold Pressor Test. Neuromodulation 2024, 27, 1227–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, D.A.; Wintering, N.; Vedaei, F.; Steinmetz, A.; Mohamed, F.B.; Newberg, A.B. Changes in brain functional connectivity associated with transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation in healthy controls. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2025, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokota, H.; Edama, M.; Kawanabe, Y.; Hirabayashi, R.; Sekikne, C.; Akuzawa, H.; Ishigaki, T.; Otsuru, N.; Saito, K.; Kojima, S.; et al. Effects of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation at left cymba concha on experimental pain as assessed with the nociceptive withdrawal reflex, and correlation with parasympathetic activity. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2024, 59, 2826–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, I.; Johns, M.A.; Pandža, N.B.; Calloway, R.C.; Karuzis, V.P.; Kuchinsky, S.E. Three Hundred Hertz Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation (taVNS) Impacts Pupil Size Non-Linearly as a Function of Intensity. Psychophysiology 2025, 62, e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deligiannidis, K.M.; Robakis, T.; Homitsky, S.C.; Ibroci, E.; King, B.; Jacob, S.; Coppola, D.; Raines, S.; Alataris, K. Effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on major depressive disorder with peripartum onset: A multicenter, open-label, controlled proof-of-concept clinical trial (DELOS-1). J Affect Disord 2022, 316, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.; Chen, C.; Falahpour, M.; MacNiven, K.H.; Heit, G.; Sharma, V.; Alataris, K.; Liu, T.T. Effects of Sub-threshold Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation on Cingulate Cortex and Insula Resting-state Functional Connectivity. Front Hum Neurosci 2022, 16, 862443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsal, S.; Corominas, H.; de Agustín, J.J.; Pérez-García, C.; López-Lasanta, M.; Borrell, H.; Reina, D.; Sanmartí, R.; Narváez, J.; Franco-Jarava, C.; et al. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation for rheumatoid arthritis: a proof-of-concept study. Lancet Rheumatol 2021, 3, e262–e269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, F.; Giannoni, A.; Navari, A.; Degl’Innocenti, E.; Emdin, M.; Passino, C. Acute right-sided transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation improves cardio-vagal baroreflex gain in patients with chronic heart failure. Clin. Auton. Res. 2025, 35, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, Z.; Han, Y.; He, J.; Zhao, B.; Wang, L.; Duan, Y.; Huo, J.; Wang, T.; et al. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Chronic Insomnia Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2451217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackland, G.L.; Patel, A.B.U.; Miller, S.; del Arroyo, A.G.; Thirugnanasambanthar, J.; Ravindran, J.I.; Schroth, J.; Boot, J.; Caton, L.; Mein, C.A.; et al. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation and exercise capacity in healthy volunteers: a randomized trial. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 1634–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatik, S.H.; Arslan, M.; Demirbilek, Ö.; Özden, A.V. The effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on cycling ergometry and recovery in healthy young individuals. Brain Behav 2023, 13, e3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.D.; Gurel, N.Z.; Jiao, Y.; Wittbrodt, M.T.; Levantsevych, O.M.; Huang, M.; Jung, H.; Shandhi, M.H.; Beckwith, J.; Herring, I.; et al. Transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation blocks stress-induced activation of Interleukin-6 and interferon-γ in posttraumatic stress disorder: A double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled trial. Brain Behav Immun Health 2020, 9, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wei, M.; Jiao, Y.; Xue, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, R.; Zeng, X.; Sun, J.; Qin, W. Site-Specific Stimulation Imperative: Lessons from a Failed Auricular-Cervical Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation Comparison Using Closely Matched Parameters. Brain Stimulation 2025, 103022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewes, A.M.; Brock, C.; Rasmussen, S.E.; Møller, H.J.; Brock, B.; Deleuran, B.W.; Farmer, A.D.; Pfeiffer-Jensen, M. Short-term transcutaneous non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation may reduce disease activity and pro-inflammatory cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis: results of a pilot study. Scand J Rheumatol 2021, 50, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brock, C.; Rasmussen, S.E.; Drewes, A.M.; Møller, H.J.; Brock, B.; Deleuran, B.; Farmer, A.D.; Pfeiffer-Jensen, M. Vagal Nerve Stimulation-Modulation of the Anti-Inflammatory Response and Clinical Outcome in Psoriatic Arthritis or Ankylosing Spondylitis. Mediat. Inflamm 2021, 2021, 9933532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Li, W.; Chen, J.D.; Liu, F. Ameliorating effects and mechanisms of transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation on abdominal pain and constipation. JCI Insight 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Moraes, T.L.; Costa, F.O.; Cabral, D.G.; Fernandes, D.M.; Sangaleti, C.T.; Dalboni, M.A.; Motta, E.M.J.; de Souza, L.A.; Montano, N.; Irigoyen, M.C.; et al. Brief periods of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation improve autonomic balance and alter circulating monocytes and endothelial cells in patients with metabolic syndrome: a pilot study. Bioelectron Med 2023, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguenard, A.L.; Tan, G.; Rivet, D.J.; Gao, F.; Johnson, G.W.; Adamek, M.; Coxon, A.T.; Kummer, T.T.; Osbun, J.W.; Vellimana, A.K.; et al. Auricular vagus nerve stimulation for mitigation of inflammation and vasospasm in subarachnoid hemorrhage: a single-institution randomized controlled trial. J Neurosurg 2025, 142, 1720–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurido-Soto, O.J.; Tan, G.; Nielsen, S.S.; Huguenard, A.L.; Donovan, K.M.; Xu, I.; Giles, J.; Dhar, R.; Adeoye, O.; Lee, J.-M.; et al. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Reduces Inflammatory Biomarkers after Large Vessel Occlusion Stroke: Results of a Prospective Randomized Open-Label Blinded Endpoint Trial. Stroke Res. 2025, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, F.I.; Souza, P.H.L.; Uehara, L.; Ritti-Dias, R.M.; da Silva, G.O.; Segheto, W.; Pacheco-Barrios, K.; Fregni, F.; Corrêa, J.C.F. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Improves Inflammation but Does Not Interfere with Cardiac Modulation and Clinical Symptoms of Individuals with COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Life 2022, 12, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeom, J.W.; Kim, H.; Park, S.; Yoon, Y.; Seo, J.Y.; Cho, C.-H.; Lee, H.-J. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) improves sleep quality in chronic insomnia disorder: A double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled trial. Sleep Med. 2025, 133, 106579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Qiao, M.; Ma, Y.; Luo, Y.; Fang, J.; Yang, Y. The efficacy and safety of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation in the treatment of depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 337, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Rong, P.; Wang, Y.; Jin, G.; Hou, X.; Li, S.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, W.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation vs Citalopram for Major Depressive Disorder: A Randomized Trial. Neuromodulation 2022, 25, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Tang, H.; Liu, C.; Ma, J.; Liu, G.; Niu, L.; Li, C.; Li, J. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation for post-stroke depression: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 354, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.M.A.; Brites, R.; Fraião, G.; Pereira, G.; Fernandes, H.; De Brito, J.A.A.; Generoso, L.P.; Capello, M.G.M.; Pereira, G.S.; Scoz, R.D.; et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation modulates masseter muscle activity, pain perception, and anxiety levels in university students: a double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1422312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.D.; Gurel, N.Z.; Wittbrodt, M.T.; Shandhi, M.H.; Rapaport, M.H.; Nye, J.A.; Pearce, B.D.; Vaccarino, V.; Shah, A.J.; Park, J.; et al. Application of Noninvasive Vagal Nerve Stimulation to Stress-Related Psychiatric Disorders. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goadsby, P.; Grosberg, B.; Mauskop, A.; Cady, R.; Simmons, K. Effect of noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation on acute migraine: An open-label pilot study. Cephalalgia 2014, 34, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silberstein, S.D.; Mechtler, L.L.; Kudrow, D.B.; Calhoun, A.H.; McClure, C.; Saper, J.R.; Liebler, E.J.; Engel, E.R.; Tepper, S.J. A.C.T.S.G. on Behalf of the, Non–Invasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation for the ACute Treatment of Cluster Headache: Findings From the Randomized, Double-Blind, Sham-Controlled ACT1 Study. Headache: J. Head Face Pain 2016, 56, 1317–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tassorelli, C.; Grazzi, L.; De Tommaso, M.; Pierangeli, G.; Martelletti, P.; Rainero, I.; Dorlas, S.; Geppetti, P.; Ambrosini, A.; Sarchielli, P.; et al. Noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation as acute therapy for migraine: The randomized PRESTO study. Neurology 2018, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.; Gianlorenço, A.C.; Andrade, M.F.; Camargo, L.; Menacho, M.; Avila, M.A.; Pacheco-Barrios, K.; Choi, H.; Song, J.-J.; Fregni, F. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation effects on chronic pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Rep. 2024, 9, e1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laqua, R.; Leutzow, B.; Wendt, M.; Usichenko, T. Transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation may elicit anti- and pro-nociceptive effects under experimentally-induced pain — A crossover placebo-controlled investigation. Auton. Neurosci. 2014, 185, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, S.; Jiang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Pan, D.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Efficacy and safety of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation plus pregabalin for radiotherapy-related neuropathic pain in patients with head and neck cancer (RELAX): a phase 2 randomised trial. EClinicalMedicine 2025, 86, 103345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranow, C.; Atish-Fregoso, Y.; Lesser, M.; Mackay, M.; Anderson, E.; Chavan, S.; Zanos, T.P.; Datta-Chaudhuri, T.; Bouton, C.; Tracey, K.J.; et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation reduces pain and fatigue in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, double-blind, sham-controlled pilot trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntire, L.K.; McKinley, R.A.; Goodyear, C.; McIntire, J.P.; Brown, R.D. Cervical transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation (ctVNS) improves human cognitive performance under sleep deprivation stress. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Li, Z.; Lyu, B.; Deng, H.; Wang, J.; Hou, B.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, W.; Zhao, L. The Role of Transcutaneous Vagal Nerve Stimulation in Cancer-Related Fatigue and Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Radiotherapy: A Randomized, Double-Blinded and Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. *Biol. *Phys. 2022, 114, S6–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Couck, M.; Caers, R.; Spiegel, D.; Gidron, Y. The Role of the Vagus Nerve in Cancer Prognosis: A Systematic and a Comprehensive Review. J. Oncol. 2018, 2018, 1236787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsutsumi, T.; Ide, T.; Yamato, M.; Kudou, W.; Andou, M.; Hirooka, Y.; Utsumi, H.; Tsutsui, H.; Sunagawa, K. Modulation of the myocardial redox state by vagal nerve stimulation after experimental myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008, 77, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ek, M.; Kurosawa, M.; Lundeberg, T.; Ericsson, A. Activation of Vagal Afferents after Intravenous Injection of Interleukin-1β: Role of Endogenous Prostaglandins. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 9471–9479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubeykovskaya, Z.; Si, Y.; Chen, X.; Worthley, D.L.; Renz, B.W.; Urbanska, A.M.; Hayakawa, Y.; Xu, T.; Westphalen, C.B.; Dubeykovskiy, A.; et al. Neural innervation stimulates splenic TFF2 to arrest myeloid cell expansion and cancer. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijmen, E.; Vannucci, L.; De Couck, M.; De Grève, J.; Gidron, Y. Therapeutic potential of the vagus nerve in cancer. Immunol. Lett. 2018, 202, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumaria, A.; Ashkan, K. Neuromodulation as an anticancer strategy. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 20521–20522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symptom Cluster | Neuroimmune Mechanisms | Psychophysiological (Arousal) Mechanisms | Key Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insomnia and Sleep Disturbance (Hyperarousal) | Inflammatory activation disrupts sleep regulatory circuits. Chronic stress and reduced vagal input promote tonic Locus Coeruleus–Norepinephrine (LC–NE) overactivation. |

Physiological hyperarousal. Sympathetic dominance and reduced vagal tone. Sustained activation of wake-promoting systems. |

Reduced heart rate variability (HRV) indexing weakened vagal tone. Elevated Interleukin-6 (IL-6), Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), and C-reactive protein (CRP). |

| Anxiety and Depression (Affective Dysregulation) | Elevated inflammatory tone. HPA axis dysregulation (e.g., elevated catecholamines and cortisol) is triggered by chronic stress. High chronic cytokine levels increase depressive and anxiety symptoms. | Autonomic imbalance and sympathetic dominance. Vagal withdrawal limits the capacity for emotional regulation. Chronic sympathetic activation and dysregulated LC-NE signaling worsen anxiety. |

Lower HRV (associated with diminished emotional regulation). Elevated IL-6, TNF-α, and CRP. Dysregulated cortisol rhythms. |

| Cancer-Related Fatigue (CRF) | High inflammation load driven by autonomic dysregulation. Proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., CRP, IL-6 and TNF-α) correlate with greater fatigue severity. | Reduced vagal tone and shift toward sympathetic dominance. Weakened inhibitory control over inflammatory pathways due to disrupted Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Pathway (CAIP) reflex. | Lower High-Frequency Heart Rate Variability (HF-HRV). Elevated IL-6 and TNF-α. Flattened diurnal cortisol rhythms. |

| Pain and Nociceptive Amplification | Inflammatory processes sustain pain by causing cytokine-driven nociceptive sensitization. Cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF- α contribute to central sensitization and increased nociceptor excitability. | Autonomic dysregulation. Increased sympathetic tone enhances nociceptor sensitization. Impaired vagal tone reduces inhibitory descending pain modulation. |

Reduced HRV (correlated with heightened pain intensity). Elevated IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β. |

| Cognitive Impairment | Chronic inflammation is associated with impaired executive function and reduced attentional control. Pro-inflammatory cytokines trigger brain fog or cognitive slowing. | Chronic distress and low parasympathetic tone promote tonic LC-NE overactivation (hyperarousal), which contributes to cognitive impairment. | Decreased HRV. Diminished pupillary reactivity or pupillary dilation (as scalable proxies of tonic LC firing and cognitive effort). |

| Standard-of-Care (SOC) | SOC Limitations | Proposed Advantages of tVNS |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Interventions (e.g., benzodiazepines, opioids, and antidepressants) | Associated with risks of severe adverse effects, drug interactions, and drug abuse or dependence. | Is a non-pharmacologic adjunct that has demonstrated safety and tolerability, with common adverse events being only mild and transient (e.g., skin irritation, headache). |

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) | Access is limited and underutilized. Patients prematurely drop from therapy. | Is safe, well tolerated, and feasible for repeated use in outpatient and home settings, making it suitable for long-term integration into survivorship care. |

| Single-Symptom Treatments | Often produces only transient relief because breast cancer symptoms are sustained by interconnected neuroimmune feedback loops. | Is a circuit-level intervention uniquely positioned to target multiple symptoms (clusters) simultaneously through up- and down-stream stream modulation of autonomic balance and anti-inflammatory pathways. |

| Implanted Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) | Requires surgically invasive procedures that present added stress and immune challenges. Can produce off-target side effects (e.g., sleep apnea and dysphonia). | Is non-invasive and offers accessibility and ease of use, positioning it as a potentially viable first-line intervention compared to surgically implanted VNS devices. |

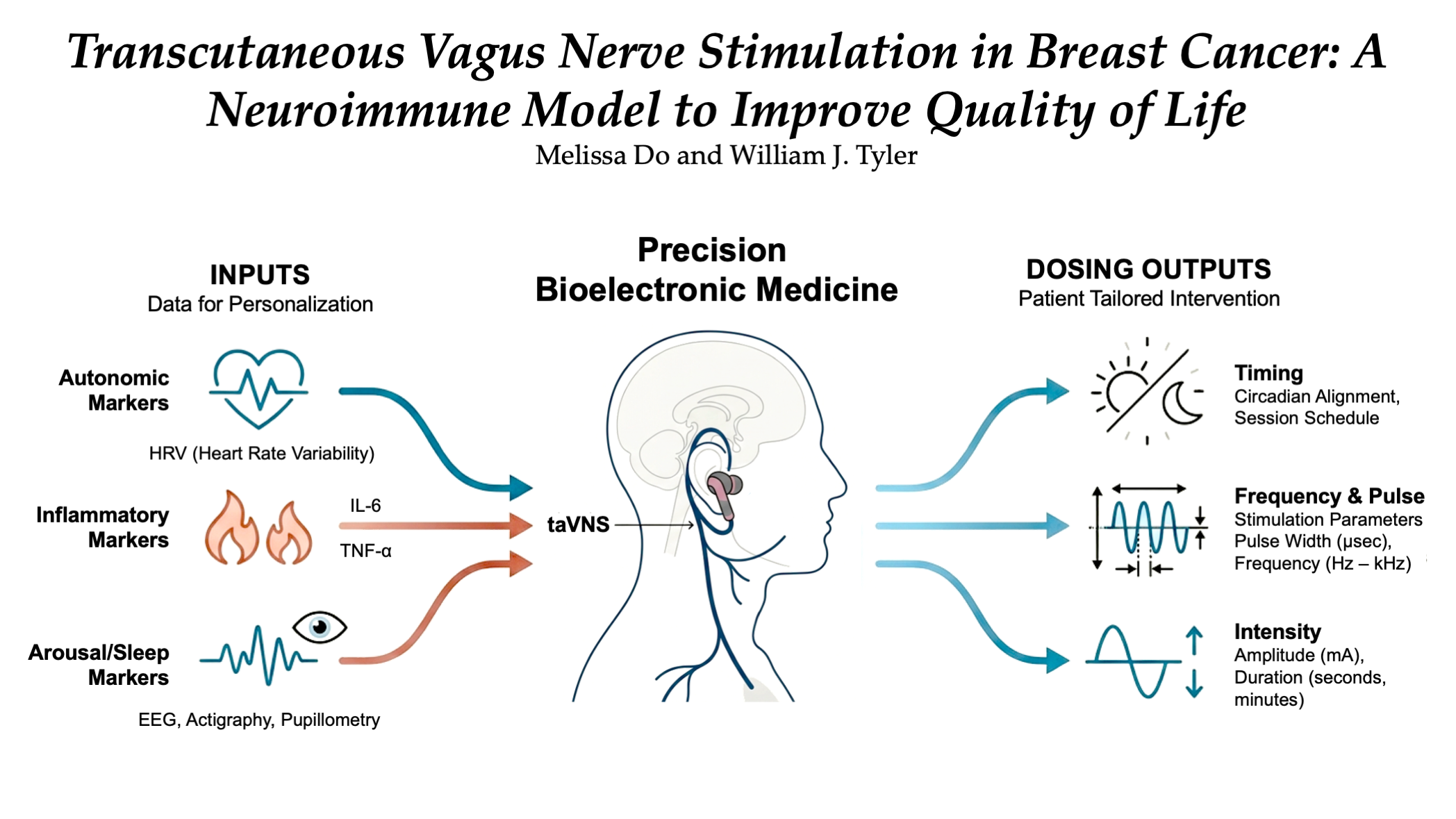

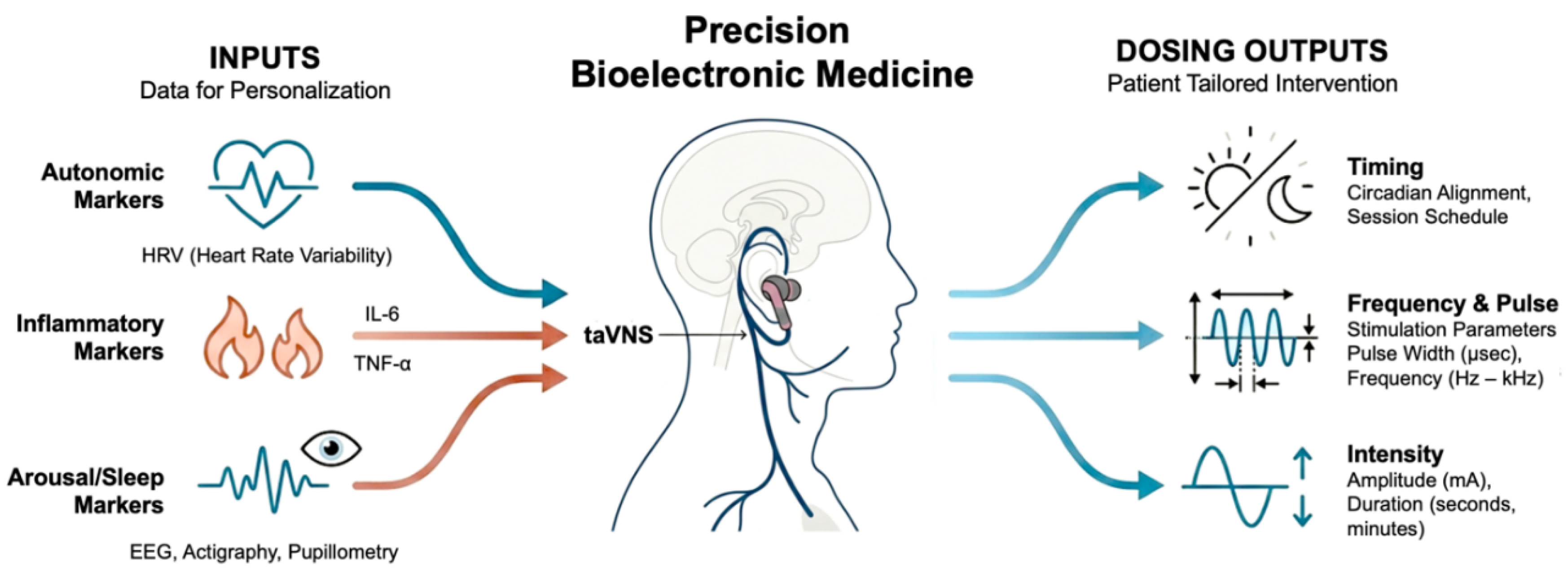

| Component | Biomarker-Informed Framework |

Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Stratification (Phenotyping) | Patients are categorized into distinct subgroups based on measurable biological and psychological data prior to intervention (phenotyping). | Symptom clusters reflect shared underlying autonomic and inflammatory dysregulation. Stratification addresses the heterogeneity of psychophysiological and quality of life burdens. |

| Biomarkers Used for Stratification | Autonomic Markers: Heart Rate Variability (HRV), Inflammatory Cytokines: IL-6, TNF-α, C-reactive protein (CRP), Arousal/Sleep Indices: EEG, pupillometry, psychomotor vigilance, reactivity, actigraphy, cortisol slope. | Low HRV (vagal withdrawal) identifies high-yield target groups for tVNS, particularly those with hyperarousal-related insomnia and anxiety. Elevated cytokines identify a “high-cytokine phenotype” potentially needing CAIP-engaging protocols to suppress chronic inflammatory signaling. Arousal markers act as scalable proxies of tonic vs. phasic Locus Coeruleus (LC) firing. |

| Phenotype-Based Targeting | Patients are matched to intervention strategies targeting their dominant drivers. For example: Hyperarousal-Insomnia Phenotype (characterized by reduced HRV and tonic LC overactivation); Inflammatory Fatigue Phenotype (characterized by elevated IL-6 and CRP, as well as brain fog). | This approach addresses breast cancer distress as a cluster-based syndrome (e.g., insomnia–fatigue–anxiety constellations) rather than disconnected complaints, moving toward cluster-stratified deployment. |

| Dosing Strategy (Personalization/Adaptivity) | Personalized tVNS delivery is implemented through individualized stimulation parameters in an open- or closed-loop manner. | This framework aims to optimize therapeutic engagement and adoption. |

| Parameters to Individualize | Modality: taVNS vs. tcVNS. Frequency, Pulse Parameters, and Duration. Timing: e.g., morning vs. daytime vs. pre-sleep administration. Intensity: Must be administered between perceptual and pain thresholds to avoid sympathetic arousal. | Dose-response studies are essential for defining optimal parameters for specific symptom constellations. Closed-loop systems dynamically adjust parameters based on real-time physiological sensing (e.g., HRV, sleep state transitions, pupillometry) to align with patient-specific psychophysiological states. |

| Clinical Endpoints (Symptom Outcomes) | Validated measures assessing the entire symptom cluster (not isolated domains). | Symptom domains include: Sleep disturbance, fatigue (Cancer-Related Fatigue), anxiety, depressive symptoms, pain interference, and cognitive function. |

| Mechanistic Endpoints (Biological Validation) | Parallel assessment of biological markers post-intervention to confirm mechanism engagement. | Mechanistic endpoints include: Changes in HRV (vagal tone restoration), Reduction in IL-6, TNF-α, and CRP (CAIP engagement and cytokine suppression), and Normalization of cortisol slope (HPA axis recalibration). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).