Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

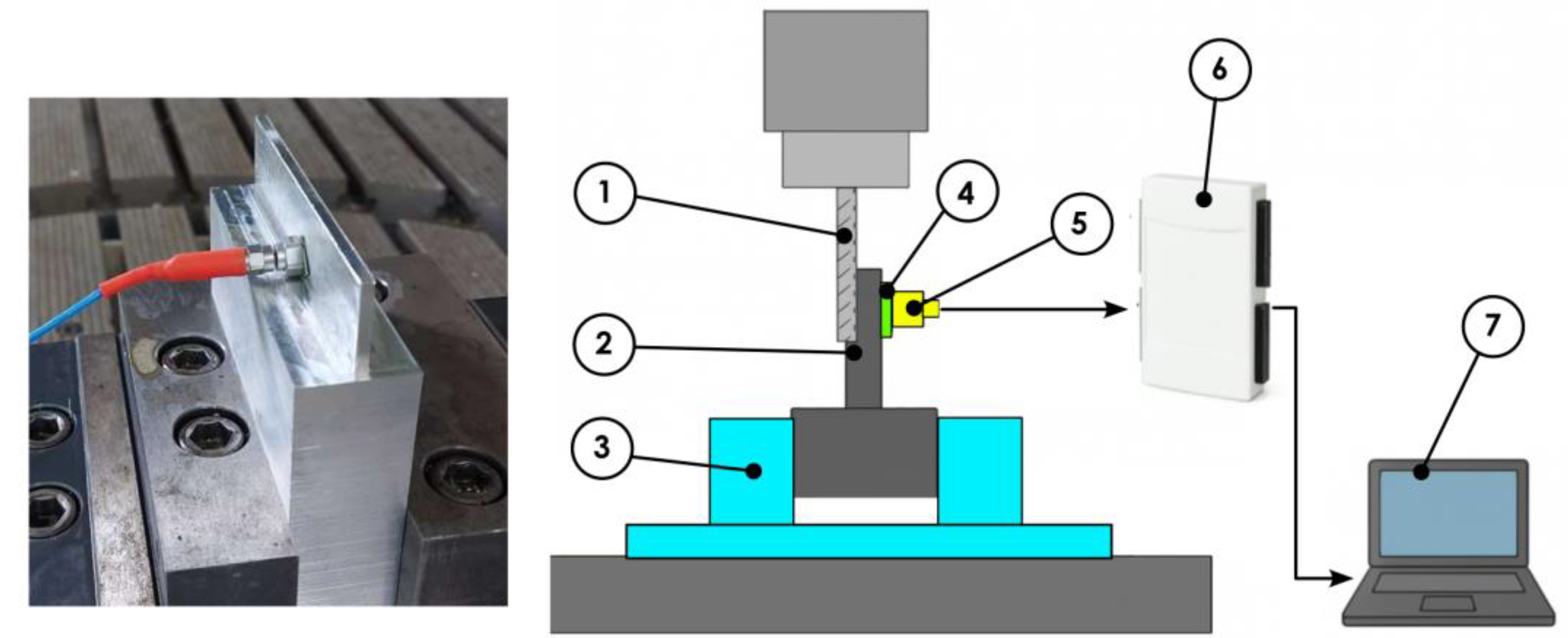

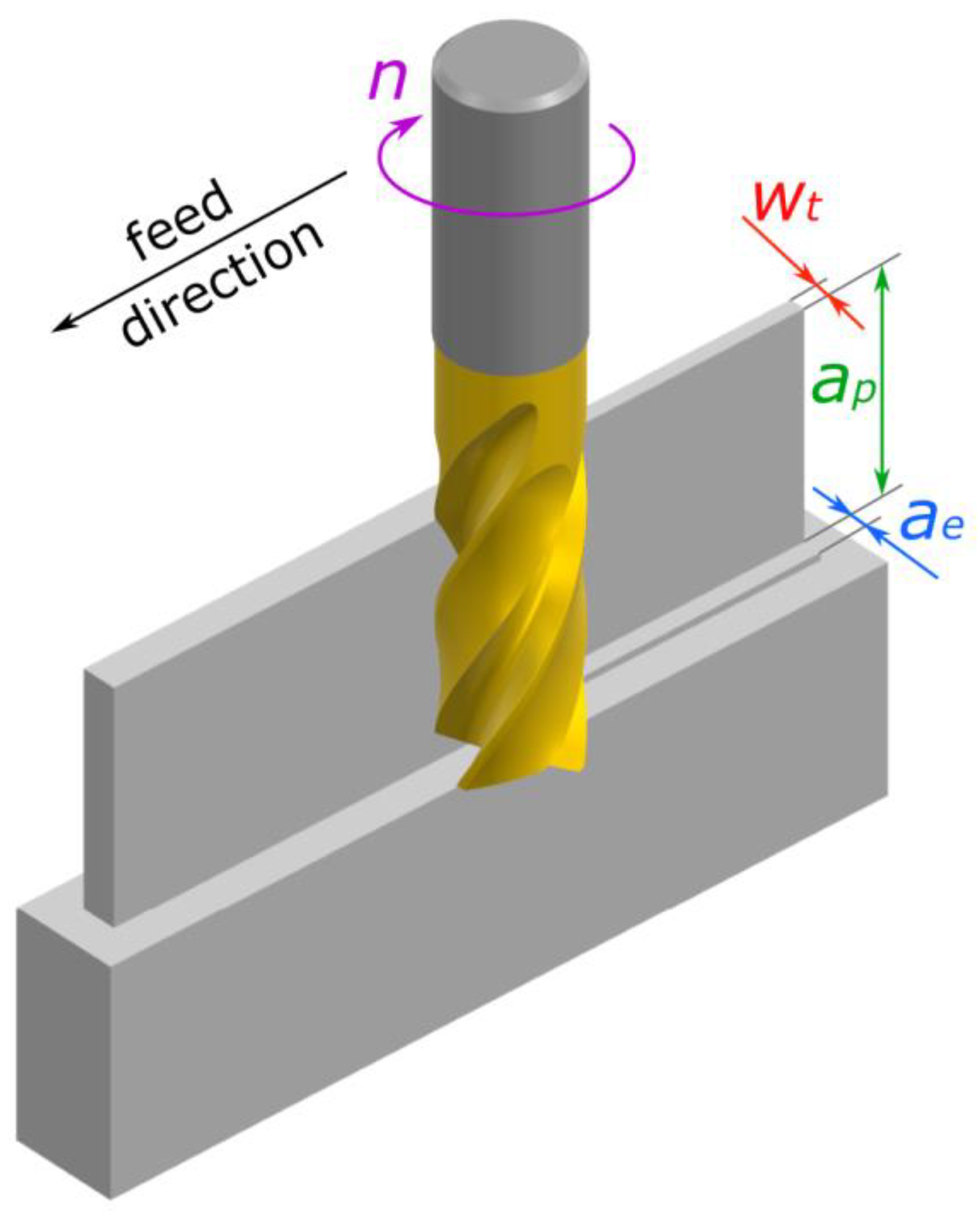

2. Materials and Methods

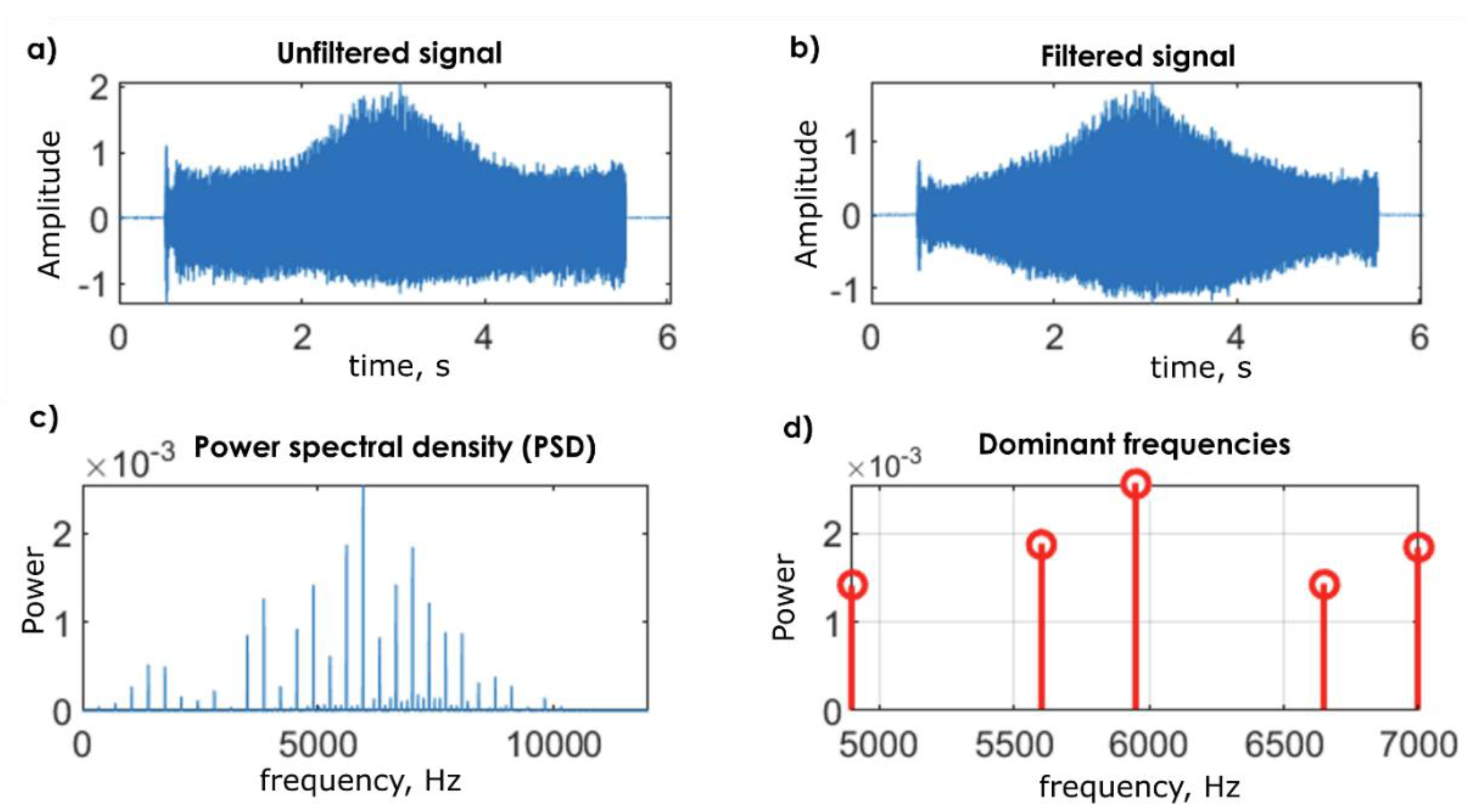

3. Vibration Signal Analysis Method

- The original (unfiltered) vibration signal as a function of time,

- The filtered vibration signal,

- The power spectral density (PSD),

- The dominant frequencies identified based on the peaks in the PSD using the findpeaks function.

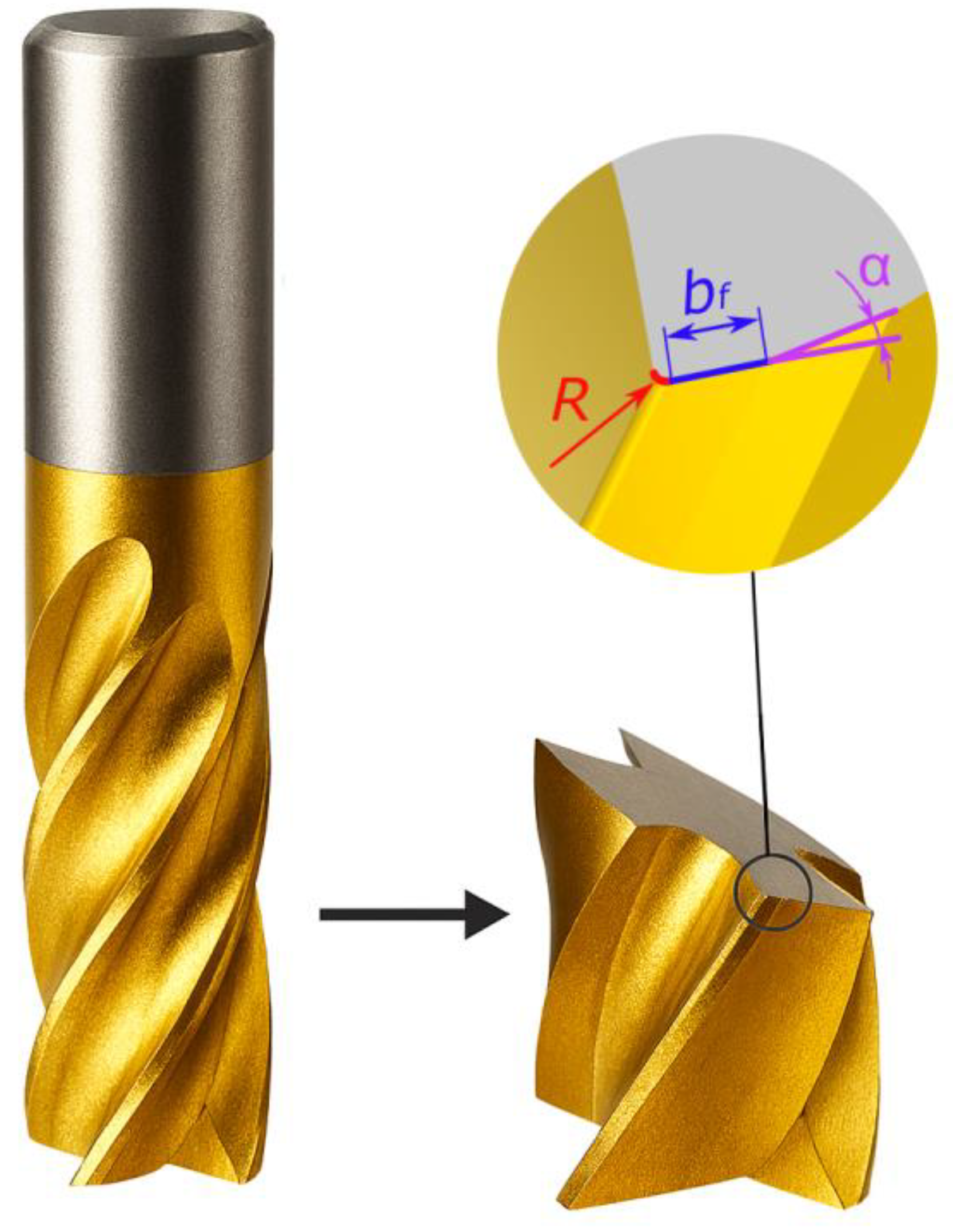

4. Analysis of the Influence of Cutting-Edge Microgeometry

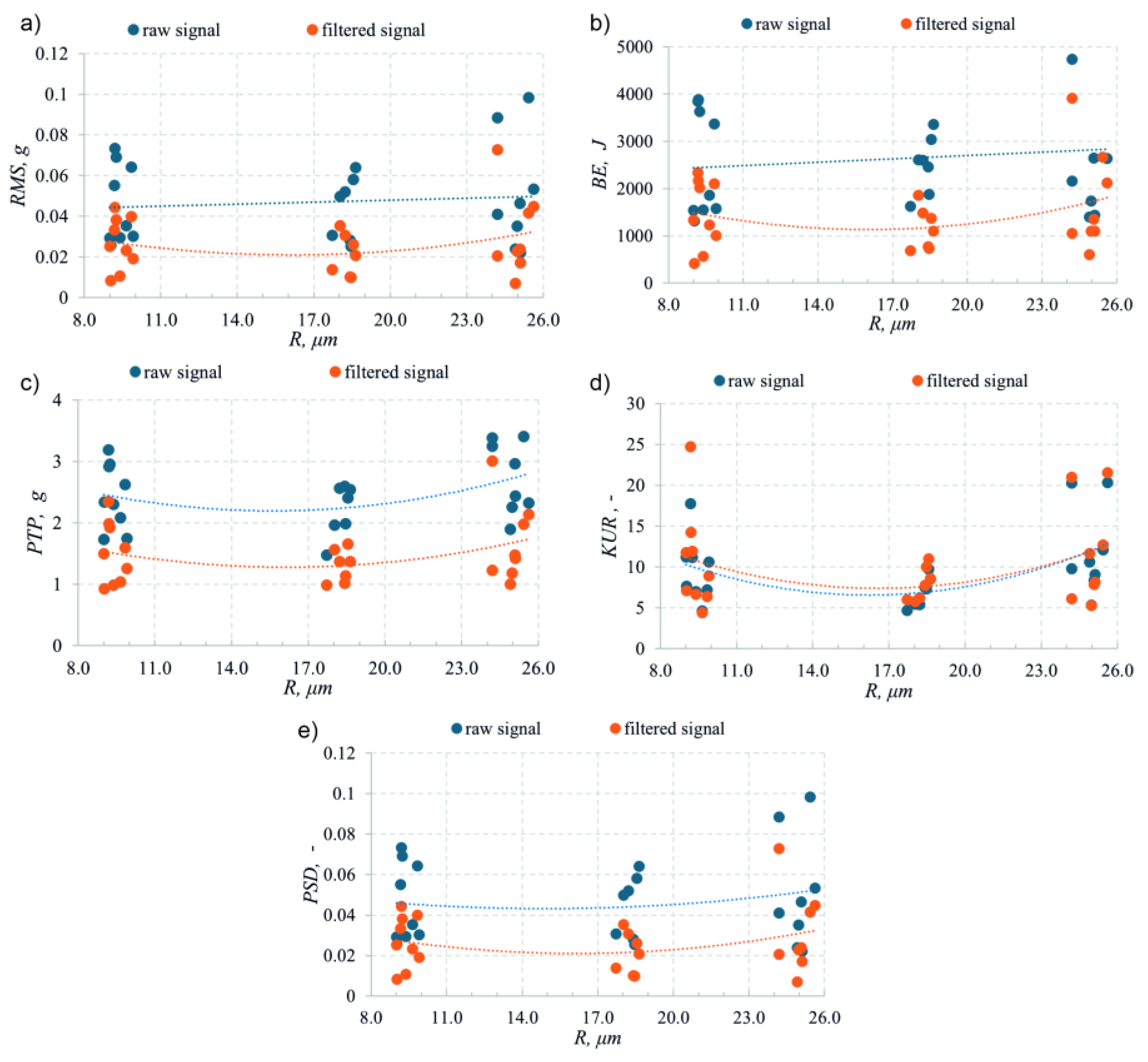

4.1. The Role of Cutting Edge Radius

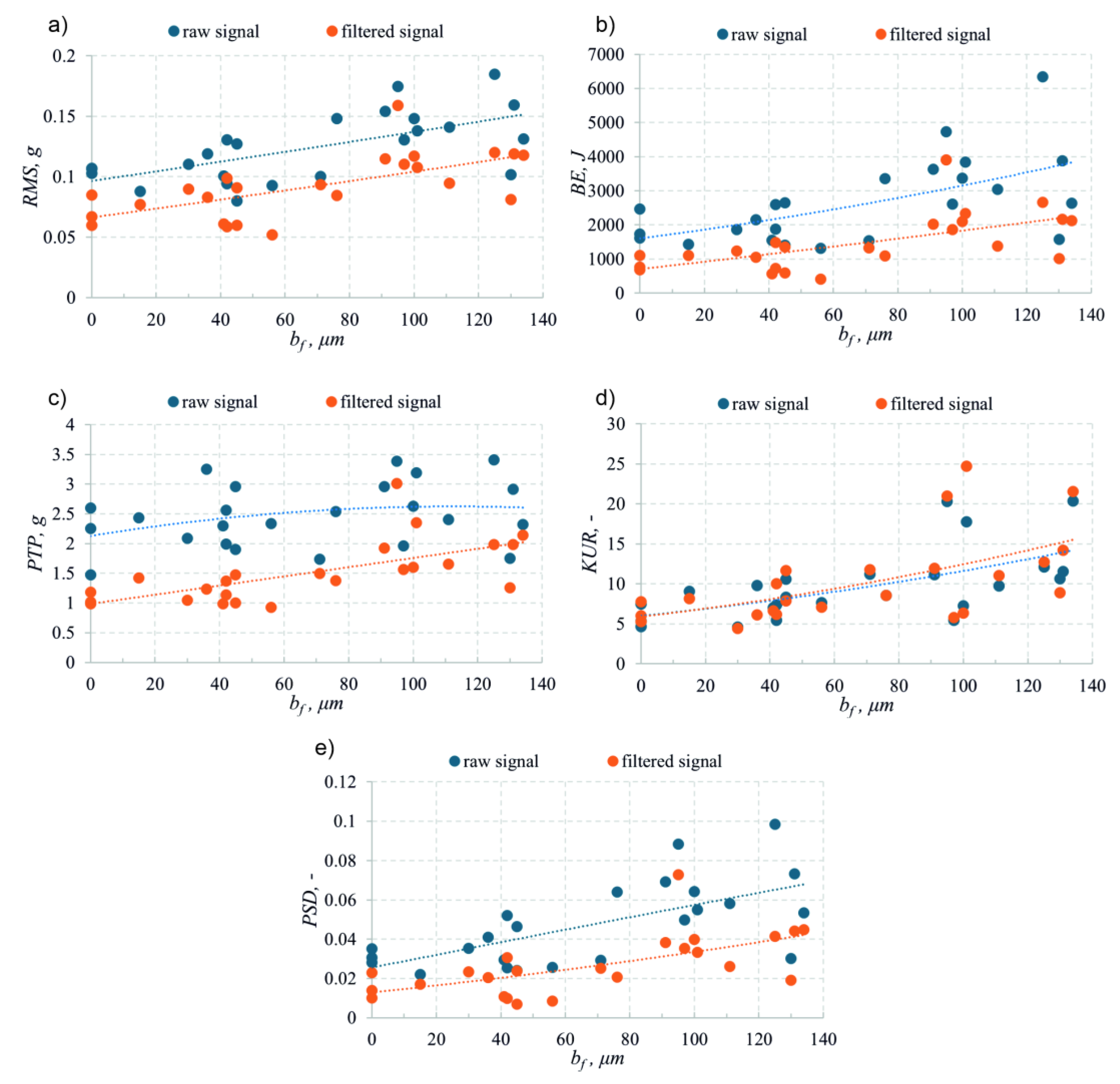

4.2. The Influence of Zero-Clearance Flank Width on Process Dynamics

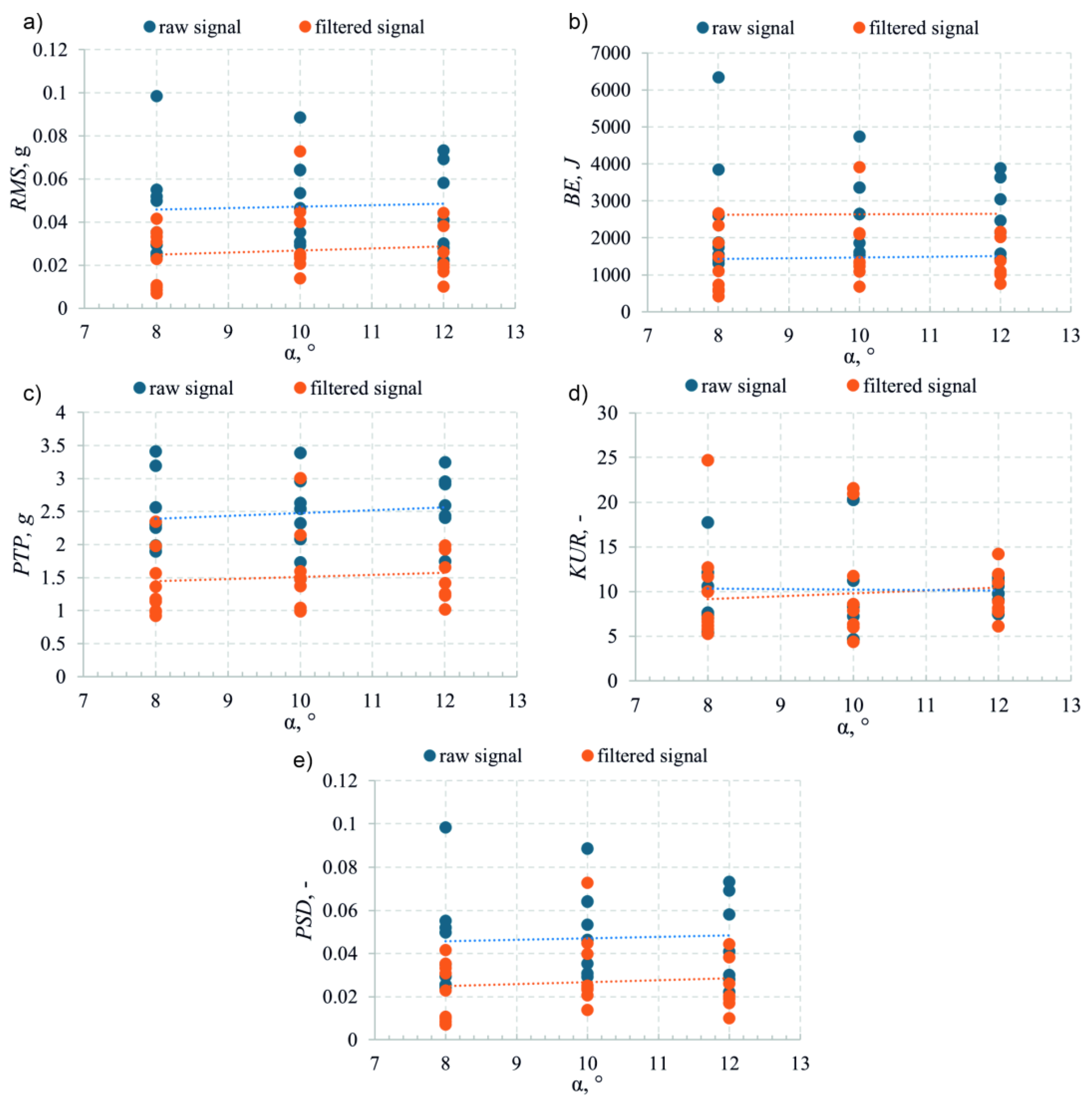

4.3. The Role of Clearance Angle

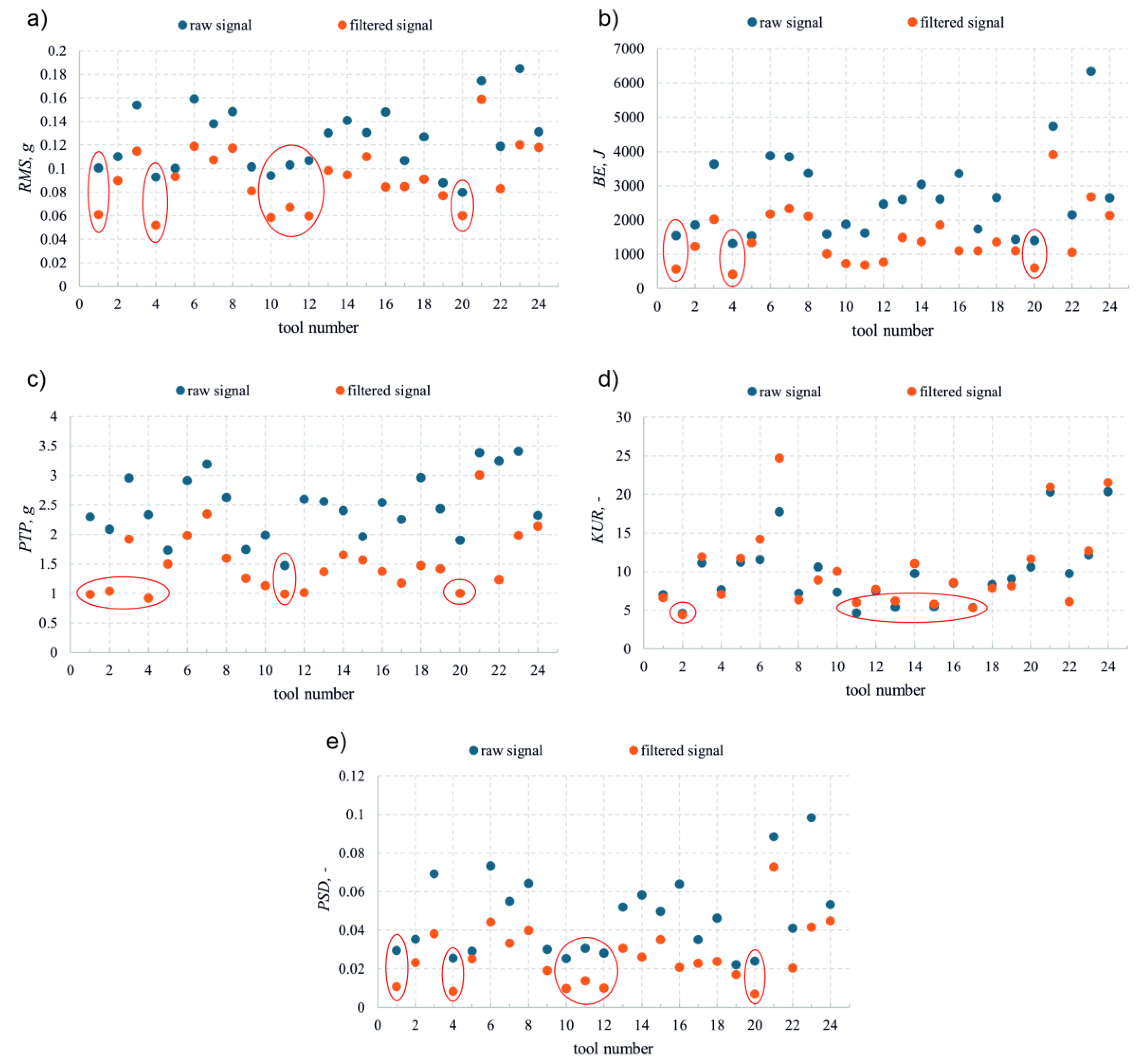

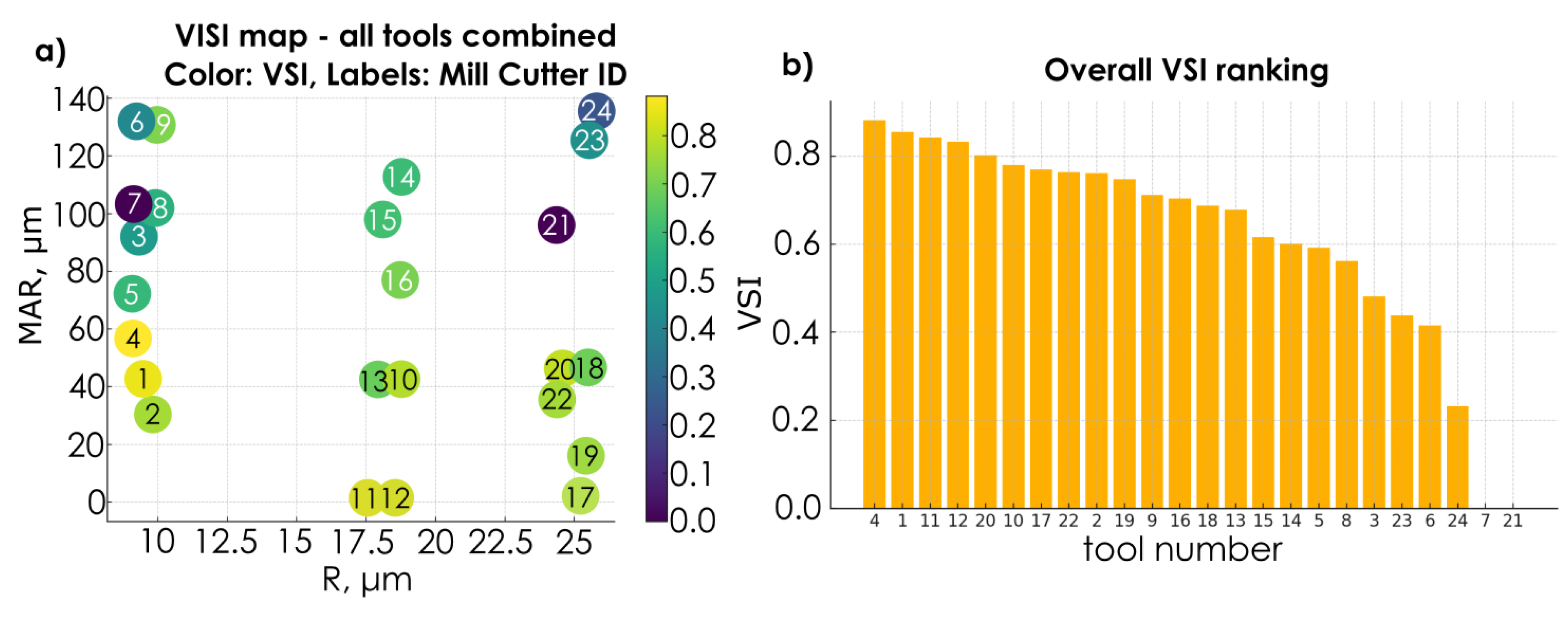

4.4. Analysis of Tool Ranking in Terms of Process Dynamics

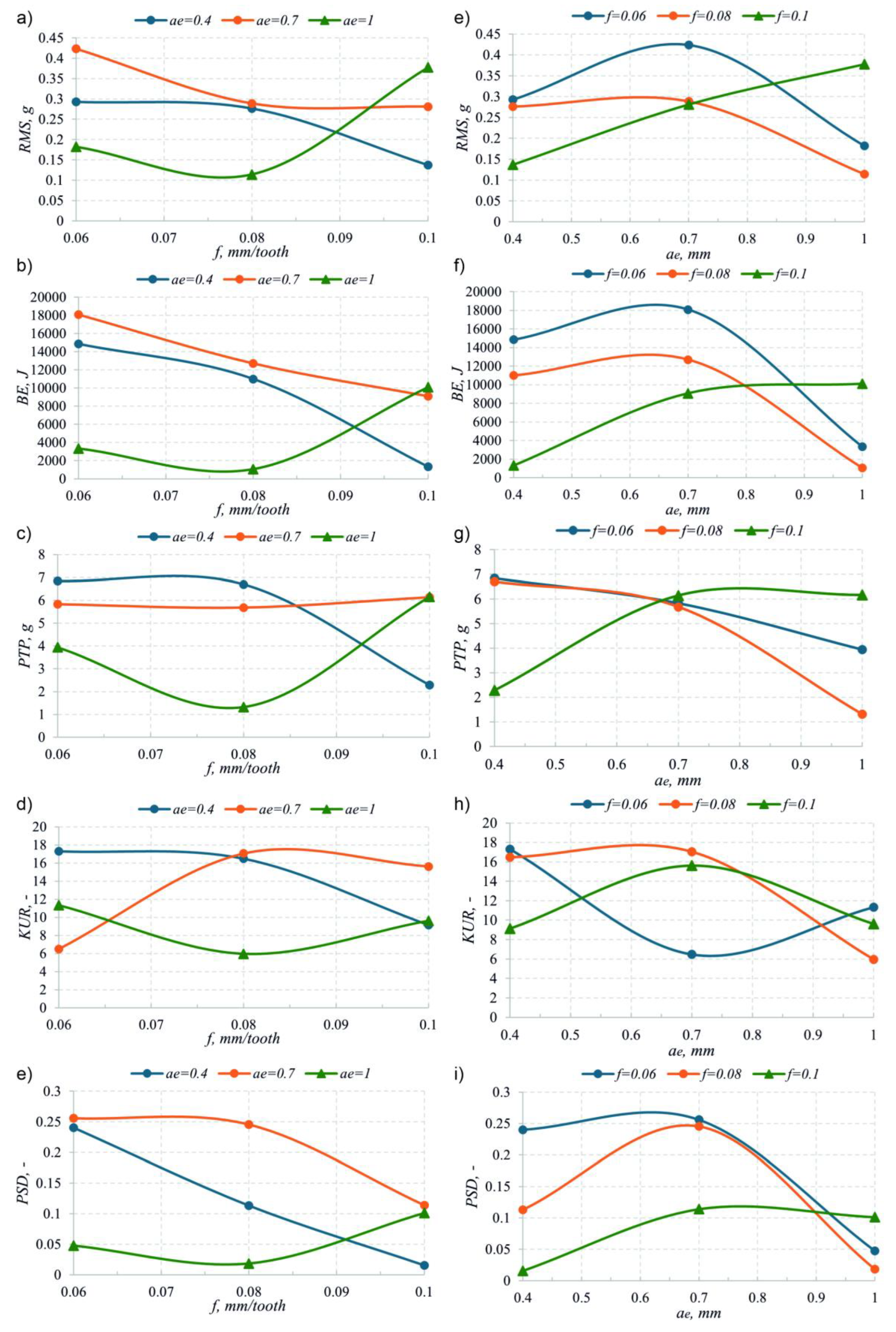

4.5. The Influence of Cutting Parameters

5. Conclusions

- The relationship between vibration parameters and the cutting edge radius R is non-monotonic. The lowest values of RMS, band energy, kurtosis, and PSD were obtained for a radius of approximately 18–19 µm. An excessively small radius leads to stress concentration and the initiation of microvibrations, while an excessively large radius increases the contact area and intensifies friction and material ploughing effects.

- The width of the zero-clearance flank land bf significantly affects process dynamics — with its increase, a distinct rise in vibration energy and signal impulsiveness is observed. The most favorable conditions were obtained at a width of approximately 40 µm, beyond which the dynamic characteristics of the process deteriorate.

- The primary clearance angle within the investigated range does not exert a significant influence on vibration levels or process dynamics. Its role is limited to ensuring proper contact between the tool and the workpiece and preventing rubbing on the flank surface.

- Technological parameters shape the dynamics of the process in a nonlinear manner. A moderate feed rate (fz = 0.08 mm/tooth) most often leads to reduced vibration amplitude and effective suppression of resonance components. However, excessively high feed rates result in a rapid increase in vibration energy and exceedance of the process dynamics.

- The radial depth of cut (ae) affects all analyzed indicators in a strongly feed-dependent manner. The most stable cutting conditions were achieved for ae = 1.0 mm combined with a moderate feed, resulting in minimal RMS, BE, PTP, kurtosis, and PSD values.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

| BE | Band Energy |

| PTP | Peak-to-Peak (Amplitude) |

| KUR | Kurtosis |

| PSD | Power Spectral Density |

| VSI | Vibration Severity Index |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| TCM | Tool Condition Monitoring |

| HHT-EA | Hilbert–Huang Transform with Empirical Approach |

| TMD | Tuned Mass Damper |

| LTMDI | Lathe/Toolholder Tuned Mass Damper Insert |

| R | Cutting-Edge Radius |

| bf | Zero-Clearance Flank Land Width |

| α | Primary Clearance Angle |

| fz | Feed per Tooth |

| ae | Radial Depth of Cut |

| ap | Axial Depth of Cut |

| wt | Wall Thickness |

| n | Spindle Speed |

References

- Lin, M.; Wang, C.; Yue, T.; Guo, G.; Guan, W.; Shen, B. Deformation Prediction in Flank Milling of Thin-Walled Parts Based on Cutter-Workpiece Engagement. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2024, 115, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buk, J.; Sułkowicz, P.; Szeliga, D. The Review of Current and Proposed Methods of Manufacturing Fir Tree Slots of Turbine Aero Engine Discs. Materials 2023, 16, 5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Ba, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, L.; Gao, F.; Zhang, F.; Ma, J. Prediction of Milling Deformation for Frame-Type Thin-Walled Parts Considering Workblank Initial Residual Stress and Milling Force. JMMP 2025, 9, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehranizadeh, F.; Berenji, K.R.; Yıldız, S.; Budak, E. Chatter Stability of Thin-Walled Part Machining Using Special End Mills. CIRP Annals 2022, 71, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepan, G.; Hajdu, D.; Iglesias, A.; Takacs, D.; Dombovari, Z. Ultimate Capability of Variable Pitch Milling Cutters. CIRP Annals 2018, 67, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Song, Q.; Jin, P.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Ma, H. Chatter Suppression Techniques in Milling Processes: A State of the Art Review. Chinese Journal of Aeronautics 2024, 37, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Yang, Y.; Yu, J.; Yang, G. Improving Processing Stability of Thin-Walled Casing Workpieces by Sucker-Mounted TMD: Optimization, Design, and Implementation. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2024, 216, 111512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ma, R.; Xu, K.; Han, Q. Closed-Form Solutions for the Optimal Design of Lever-Arm Tuned Mass Damper Inerter (LTMDI). Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2024, 206, 110889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, H.-C.; Wan, M.; Zhang, W.-H. A New Cutting Tool Filled with Metallic Lattice and Design Method for Vibration Suppression in Milling. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2024, 212, 111310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, X.; Wan, M.; Yang, Y. Prediction and Suppression of Chatter in Milling of Structures with Low-Rigidity: A Review. Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Science and Technology 2021, 1, 2021010–2021010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, D.; Liu, H.; Qiao, H.; Wang, X. Timely Online Chatter Detection in End Milling Process. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2016, 75, 668–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.-Y.; Raihany, U.; Kuo, S.-W.; Chen, Y.-Z. Sound Detection Monitoring Tool in CNC Milling Sounds by K-Means Clustering Algorithm. Sensors 2021, 21, 4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, S.; Diaz-Elsayed, N. Tool Condition Monitoring in the Milling of Low- to High-Yield-Strength Materials. Machines 2025, 13, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Devia, J.H.; Chen, Y.; Dao, D.V.; Li, H. Chatter Detection in Milling Processes—a Review on Signal Processing and Condition Classification. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2023, 125, 3943–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpysa, J.; Zawada-Michałowska, M.; Pieśko, P.; Habrat, W.; Lisowicz, J. Machinability Assessment of Aluminium Alloy EN AW-7075 T651 Under Varying Machining Conditions. Acta Mechanica et Automatica 2025, 19, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkena, B.; Biermann, D. Cutting Edge Geometries. CIRP Annals 2014, 63, 631–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, S.; Du, J.; Sun, Y. State-of-the-Art in Cutting Performance and Surface Integrity Considering Tool Edge Micro-Geometry in Metal Cutting Process. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2022, 77, 380–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, K.; Fu, C.; Weng, J.; Hu, C. Cutting Edge Microgeometries in Metal Cutting: A Review. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2021, 116, 2045–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulemova, J.; Janda, Z. Influence of the Cutting Edge Radius and the Cutting Edge Preparation on Tool Life and Cutting Forces at Inserts with Wiper Geometry. Procedia Engineering 2014, 69, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, D.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X. Effects of Cutting Edge Radius on Cutting Force, Tool Wear, and Life in Milling of SUS-316L Steel. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2020, 111, 2833–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hronek, O.; Zetek, M. The Influences of Cutting Edge Radius on Surface Roughness When Milling Nickel Alloy. In DAAAM Proceedings; Katalinic, B., Ed.; DAAAM International Vienna, 2017; Vol. 1, pp. 1037–1043 ISBN 978-3-902734-11-2.

- Zhao, T.; Agmell, M.; Persson, J.; Bushlya, V.; Ståhl, J.E.; Zhou, J.M. Correlation between Edge Radius of the cBN Cutting Tool and Surface Quality in Hard Turning. J. Superhard Mater. 2017, 39, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M, P.; N, S.P. Effect of Cutting Edge Form Factor (K-Factor) on the Performance of a Face Milling Tool. CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology 2020, 31, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuswamy, P.; Nagarajan, S.K. Experimental Investigation on the Effect of Different Micro-Geometries on Cutting Edge and Wiper Edge on Surface Roughness and Forces in Face Milling. Lubricants 2021, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuswamy, P. Influence of Micro-Geometry of Wiper Facet on the Performance of a Milling Insert: An Experimental Investigation and Validation Using Numerical Simulation. Sādhanā 2022, 47, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, R.; Denkena, B.; Köhler, J. Prediction of Process Forces and Stability of End Mills with Complex Geometries. Procedia CIRP 2014, 14, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burek, J.; Zylka, L.; Plodzien, M.; Gdula, M.; Sulkowicz, P. The Influence of the Cutting Edge Shape on High Performance Cutting. AEAT 2018, 90, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burek, J.; Plodzien, M.; Zylka, L.; Sulkowicz, P. High-Performance End Milling of Aluminum Alloy: Influence of Different Serrated Cutting Edge Tool Shapes on the Cutting Force. Adv produc engineer manag 2019, 14, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Zhao, J.; Pei, Z.; Zhu, N. Simulation-Based Solid Carbide End Mill Design and Geometry Optimization. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2014, 71, 1889–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ruiz, J.; González-Barrio, H.; Sanz-Calle, M.; Gómez-Escudero, G.; Munoa, J.; De Lacalle, L.L. Machining Stability Improvement in LPBF Printed Components through Stiffening by Crystallographic Texture Control. CIRP Annals 2023, 72, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, U.; Altuzarra, O.; López De Lacalle, L.N.; Sánchez, J.A.; Campa, F.J. Stability Limits of Milling Considering the Flexibility of the Workpiece and the Machine. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture 2005, 45, 1669–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żyłka, Ł.; Flejszar, R.; Lajmert, P. Influence of Cutting-Edge Microgeometry on Cutting Forces in High-Speed Milling of 7075 Aluminum Alloy. Materials 2023, 16, 3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żyłka, Ł.; Flejszar, R.; Krupa, K.; Lajmert, P. Redefinition of Precision in Finishing Milling: Exploring the Influence of Tool Margin and Edge Micro-Radius on Surface Roughness. Manufacturing Letters 2024, 41, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, N.; Ravi, Y.B.; Patra, A.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Paul, S.; Mohanty, A.R.; Chattopadhyay, A.B. Estimation of Tool Wear during CNC Milling Using Neural Network-Based Sensor Fusion. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2007, 21, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S. Signal Detection Based on Power-Spectrum Sub-Band Energy Ratio. Electronics 2020, 10, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, D.; Tlach, V.; Kuric, I.; Dodok, T.; Zajačko, I.; Tucki, K. Technical Diagnostics of Industrial Robots Using Vibration Signals: Case Study on Detecting Base Unfastening. Applied Sciences 2024, 15, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; An, R.; Jiang, H.; Du, Y.; Zheng, W. Research on Fault Recognition of Roadheader Based on Multi-Sensor and Multi-Layer Local Projection. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, R.-V.; Macancela, J.C.; Ortega, L.-R.; Cabrera, D.; García Márquez, F.P.; Cerrada, M. Evaluation of Hand-Crafted Feature Extraction for Fault Diagnosis in Rotating Machinery: A Survey. Sensors 2024, 24, 5400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawalhi, N.; Randall, R.B. The Application of Spectral Kurtosis to Bearing Diagnostics. 2004.

- Pirrotta, C.; Gueli, A.M.; Imposa, S.; Salerno, G.A.; Trigona, C. Vibration Analysis at Castello Ursino Picture Gallery (Sicily, Italy) for the Implementation of Self-Generating AlN-MEMS Sensors. Sensors 2024, 24, 5617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, N.R.; Lourenço, J.; Pereira, Z.L. Desirability Function Approach: A Review and Performance Evaluation in Adverse Conditions. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2011, 107, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera Candioti, L.; De Zan, M.M.; Cámara, M.S.; Goicoechea, H.C. Experimental Design and Multiple Response Optimization. Using the Desirability Function in Analytical Methods Development. Talanta 2014, 124, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

End mill cutter number |

Edge radius R, μm |

Flank width bf, μm |

Clearance angle α, ° |

| 1 | 9.4 | 41 | 8 |

| 2 | 9.7 | 30 | 10 |

| 3 | 9.3 | 91 | 12 |

| 4 | 9.0 | 56 | 8 |

| 5 | 9.0 | 71 | 10 |

| 6 | 9.2 | 131 | 12 |

| 7 | 9.2 | 101 | 8 |

| 8 | 9.8 | 100 | 10 |

| 9 | 9.9 | 130 | 12 |

| 10 | 18.5 | 42 | 8 |

| 11 | 17.7 | 0 | 10 |

| 12 | 18.4 | 0 | 12 |

| 13 | 18.2 | 42 | 8 |

| 14 | 18.6 | 111 | 12 |

| 15 | 18.0 | 97 | 8 |

| 16 | 18.6 | 76 | 10 |

| 17 | 25.0 | 0 | 8 |

| 18 | 25.1 | 45 | 10 |

| 19 | 25.1 | 15 | 12 |

| 20 | 24.9 | 45 | 8 |

| 21 | 24.2 | 95 | 10 |

| 22 | 24.2 | 36 | 12 |

| 23 | 25.4 | 125 | 8 |

| 24 | 25.6 | 134 | 10 |

| Test number |

Feed per tooth fz, mm/tooth |

Radial depth of cut ae, mm |

| 1 | 0.06 | 0.4 |

| 2 | 0.06 | 0.7 |

| 3 | 0.06 | 1 |

| 4 | 0.08 | 0.4 |

| 5 | 0.08 | 0.7 |

| 6 | 0.08 | 1 |

| 7 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| 8 | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| 9 | 0.1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).