Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

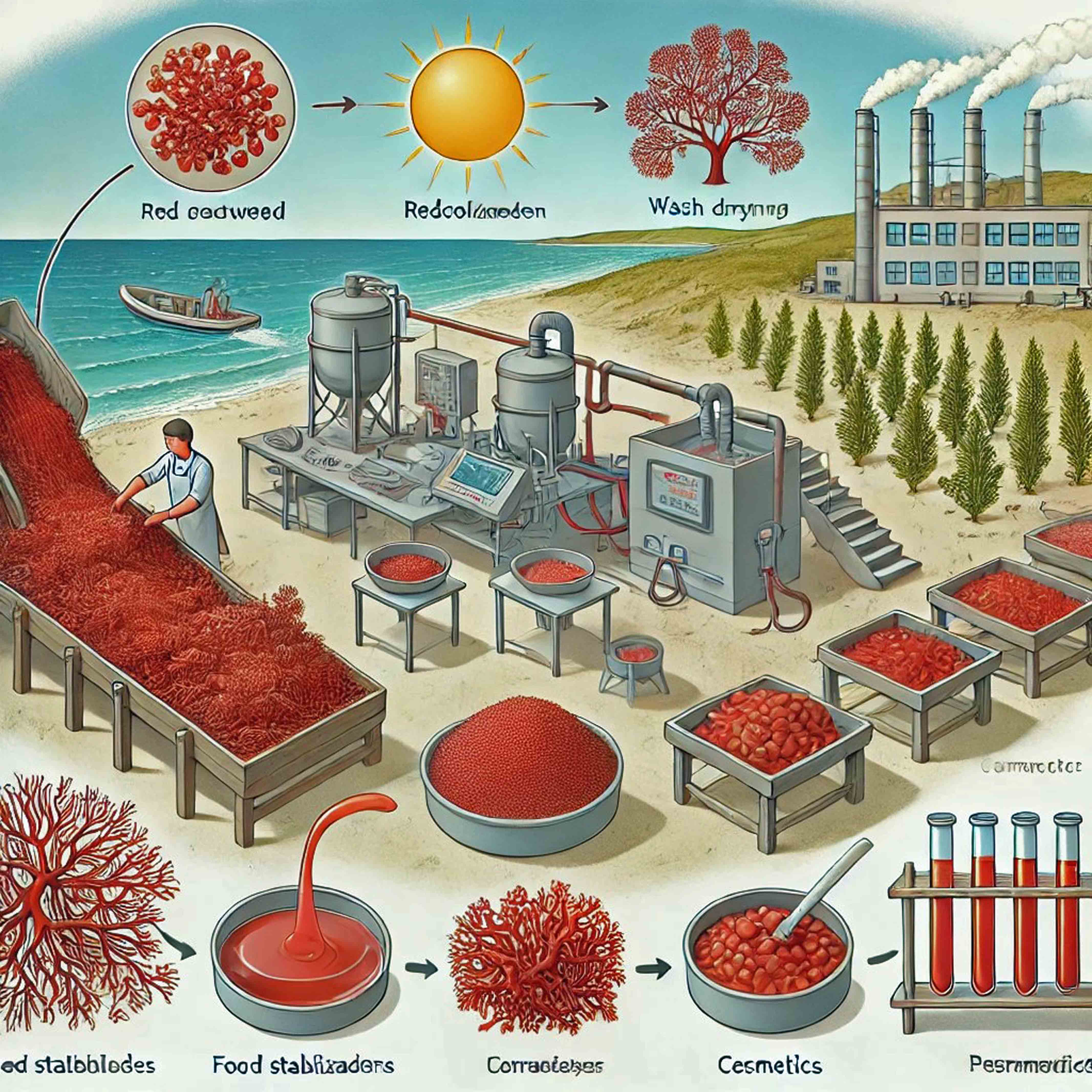

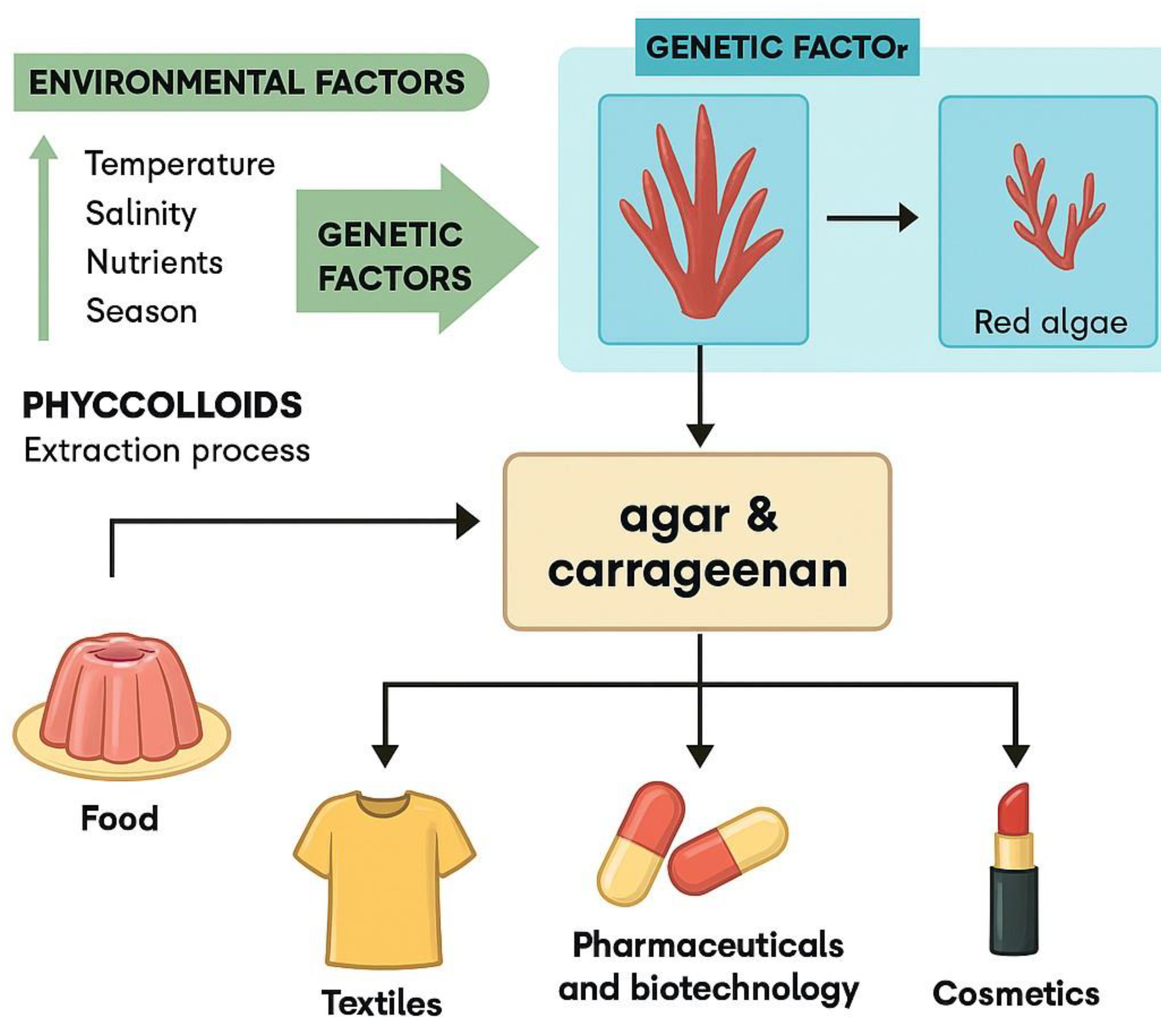

Phycocolloids derived from red algae, including agar, carrageenan, and related sulfated polysaccharides, have attracted growing interest due to their multifunctional properties and wide-ranging industrial applications. These marine biopolymers exhibit unique structural characteristics and bioactivities that support their use in food, pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and biomedical sectors. This review provides a comprehensive synthesis of current knowledge on red algae phycocolloids, beginning with their biological origin, biosynthetic pathways, and ecological roles. It highlights recent advances in extraction and purification technologies, with a focus on improving yield, safety, and environmental sustainability. The review also explores emerging applications in drug delivery, tissue engineering, and green technologies, underscoring their potential in sustainable innovation. Key challenges—including regulatory constraints, scalability, and the need for interdisciplinary collaboration—are discussed, along with future directions for research and industrial development. This work aims to support the strategic integration of red algae phycocolloids into next-generation biotechnological solutions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Drivers of Polysaccharide Production

2.1. Abiotic Factors

2.2. Biotic Factors

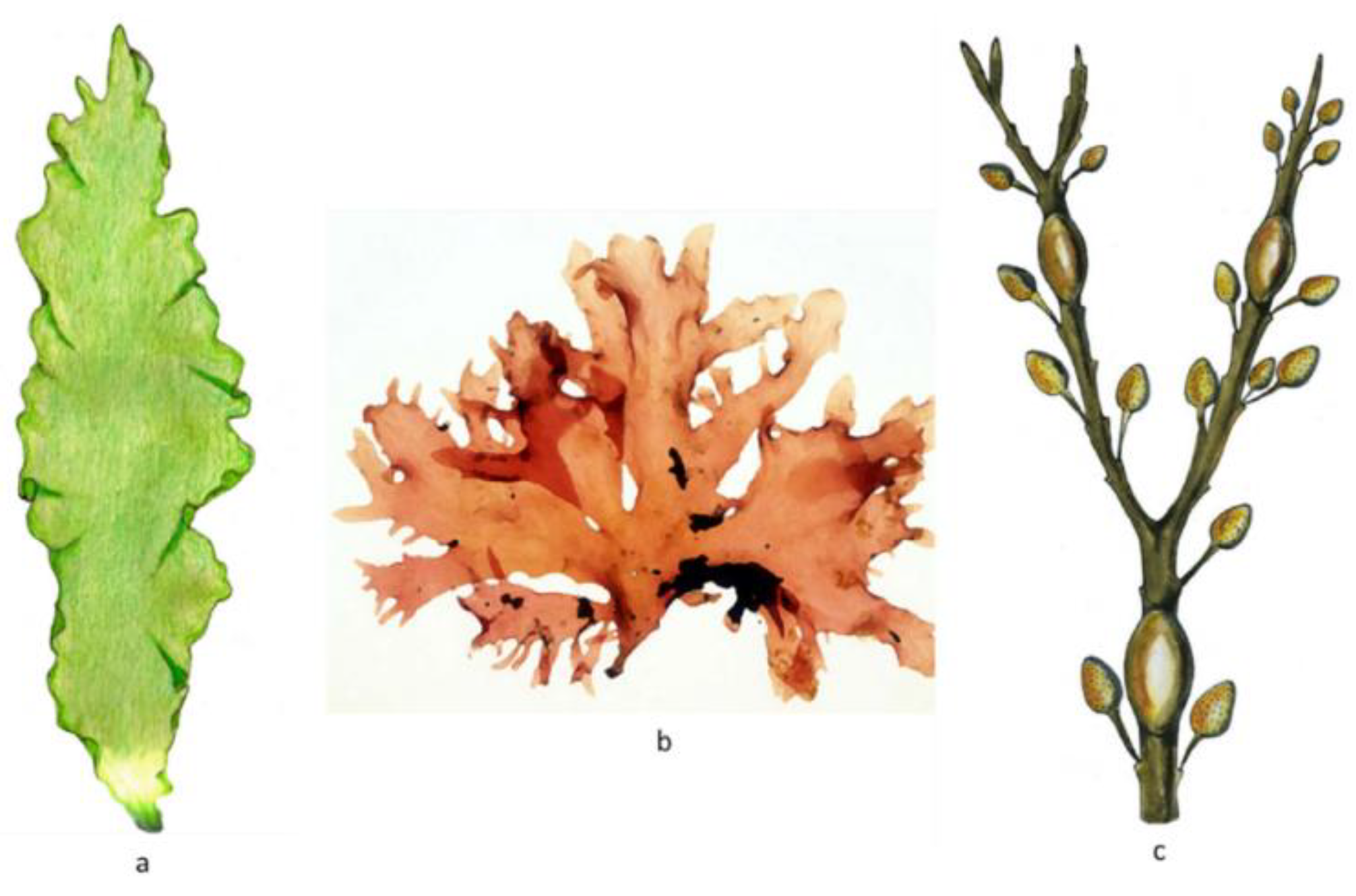

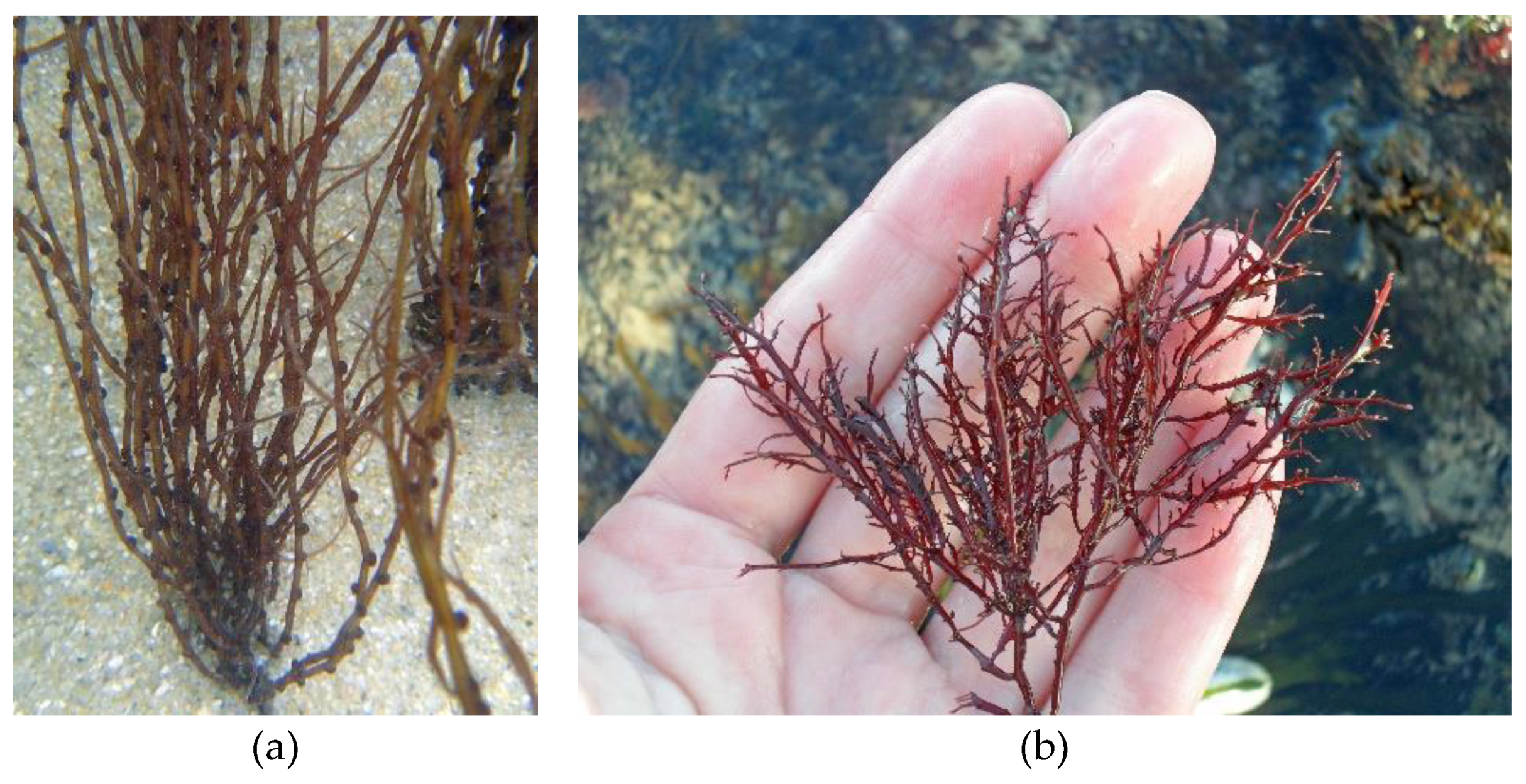

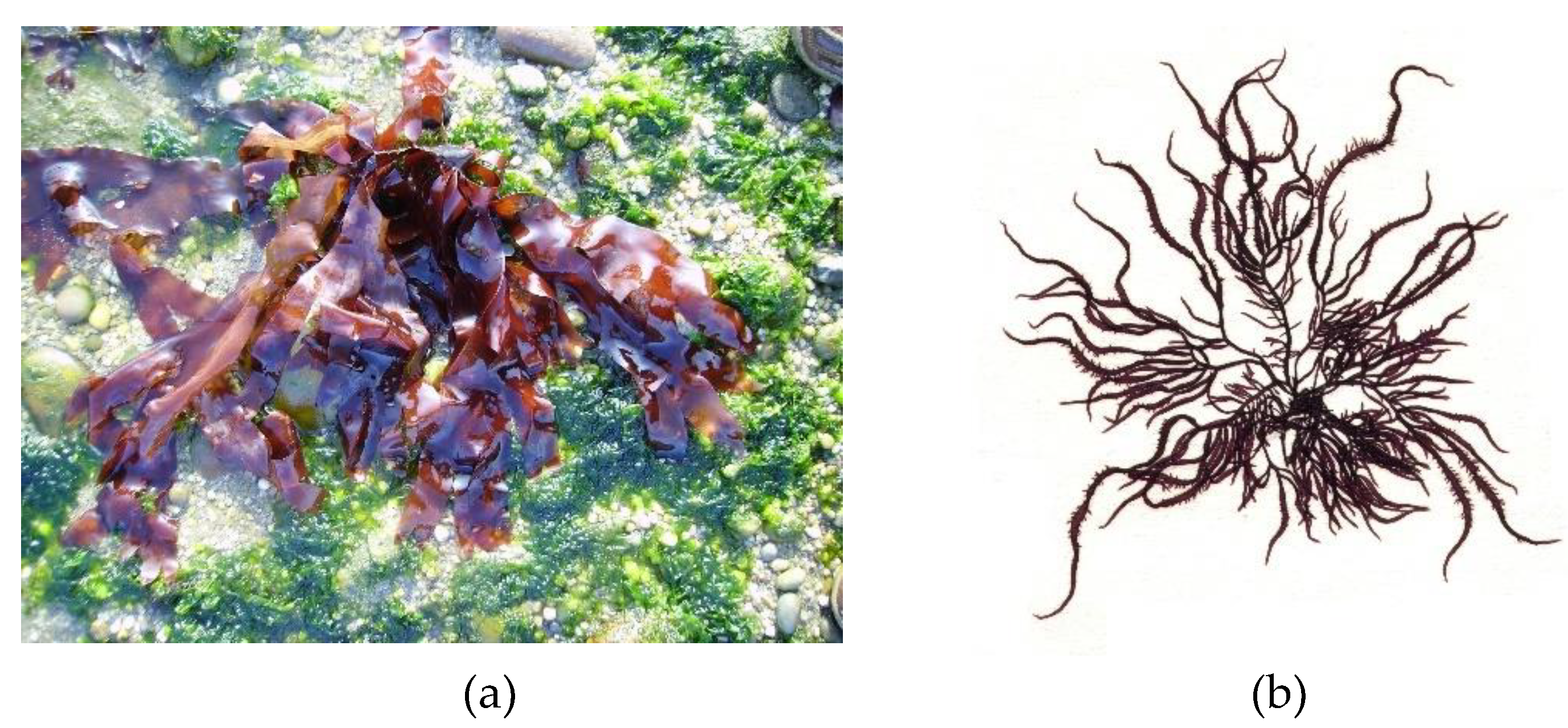

3. Red Macroalgae Polysaccharide Studies in Polysaccharide Production

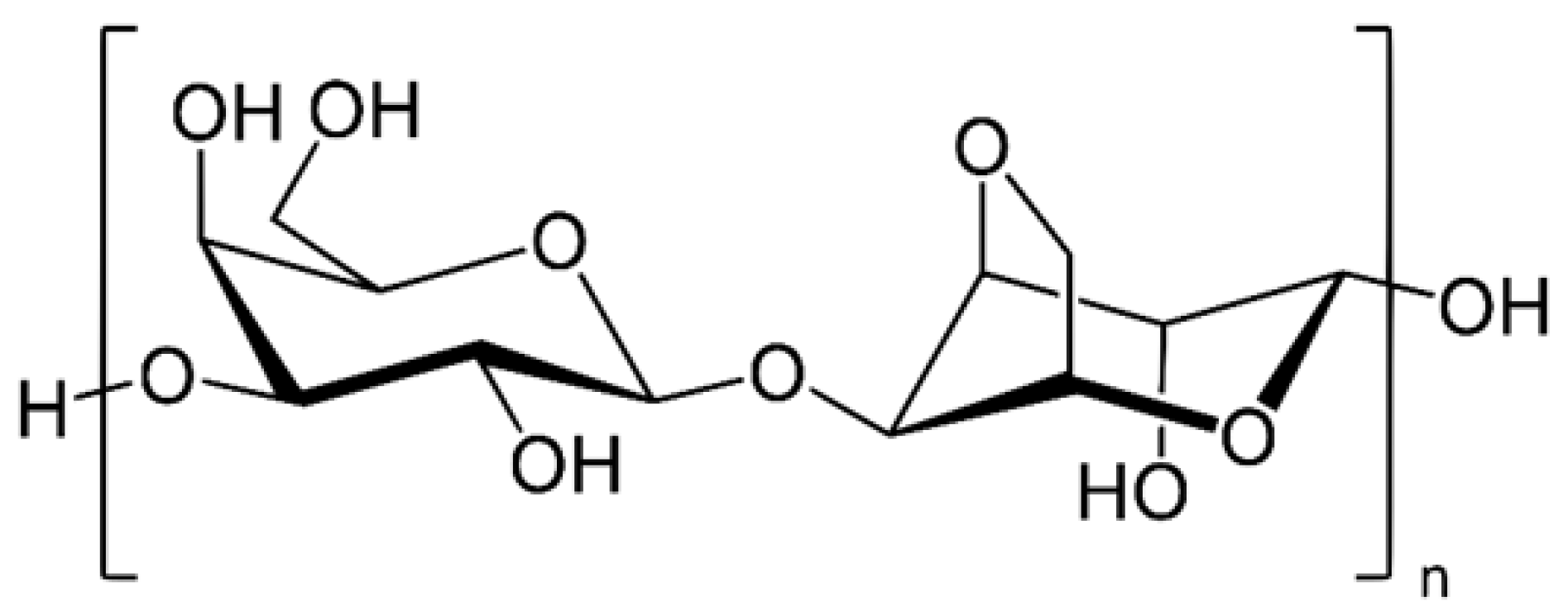

3.1. Agar

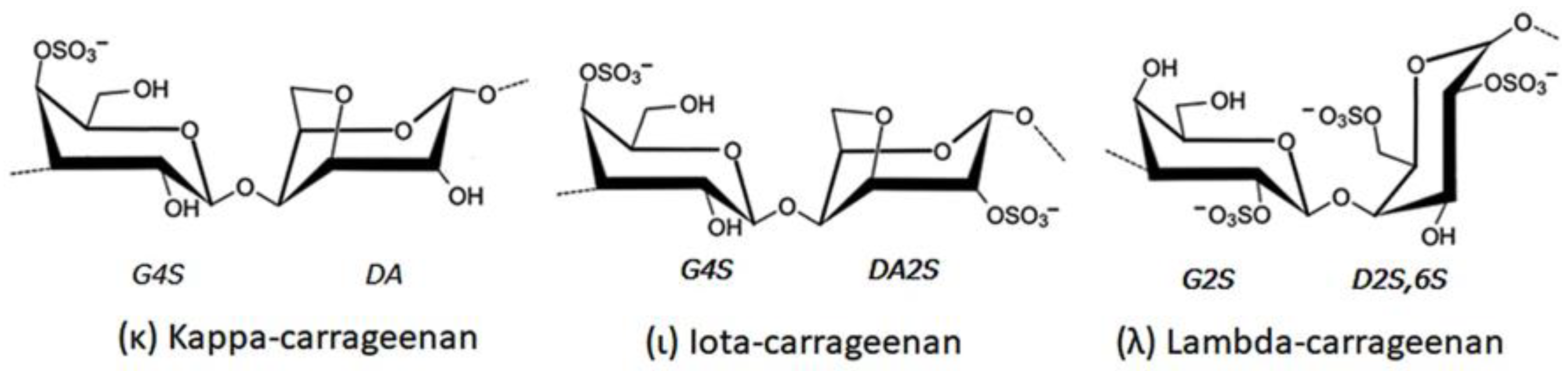

3.2. Carrageenan

4. Extraction Technologies and Safety Measures for Phycocolloid Production

4.1. Industrial Extraction Methods

4.1.1. Agar

4.1.2. Carrageenan

4.2. Industrial Safety Measures

4.3. Technical Characteristics of Agar and Carrageenan

4.3.1. Agar

4.3.2. Carrageenan

4.4. RD of Polysaccharide Extraction Methods

5. Seaweed Polysaccharides’ Current Industrial Applications

5.1. Food Industry

5.2. Pharmaceutical and Medical Industry

5.3. Cosmetic Industry

5.4. Agriculture and Industry

5.5. Livestock Industry

6. Industrial Innovation: Emerging Applications of Seaweed Polysaccharides

6.1. Pharmaceutical Applications

6.2. Food Packaging

7. Future Road for Red Seaweed Polysaccharide Exploitation

7.1. Seaweed-Based Biodegradable Packaging Materials

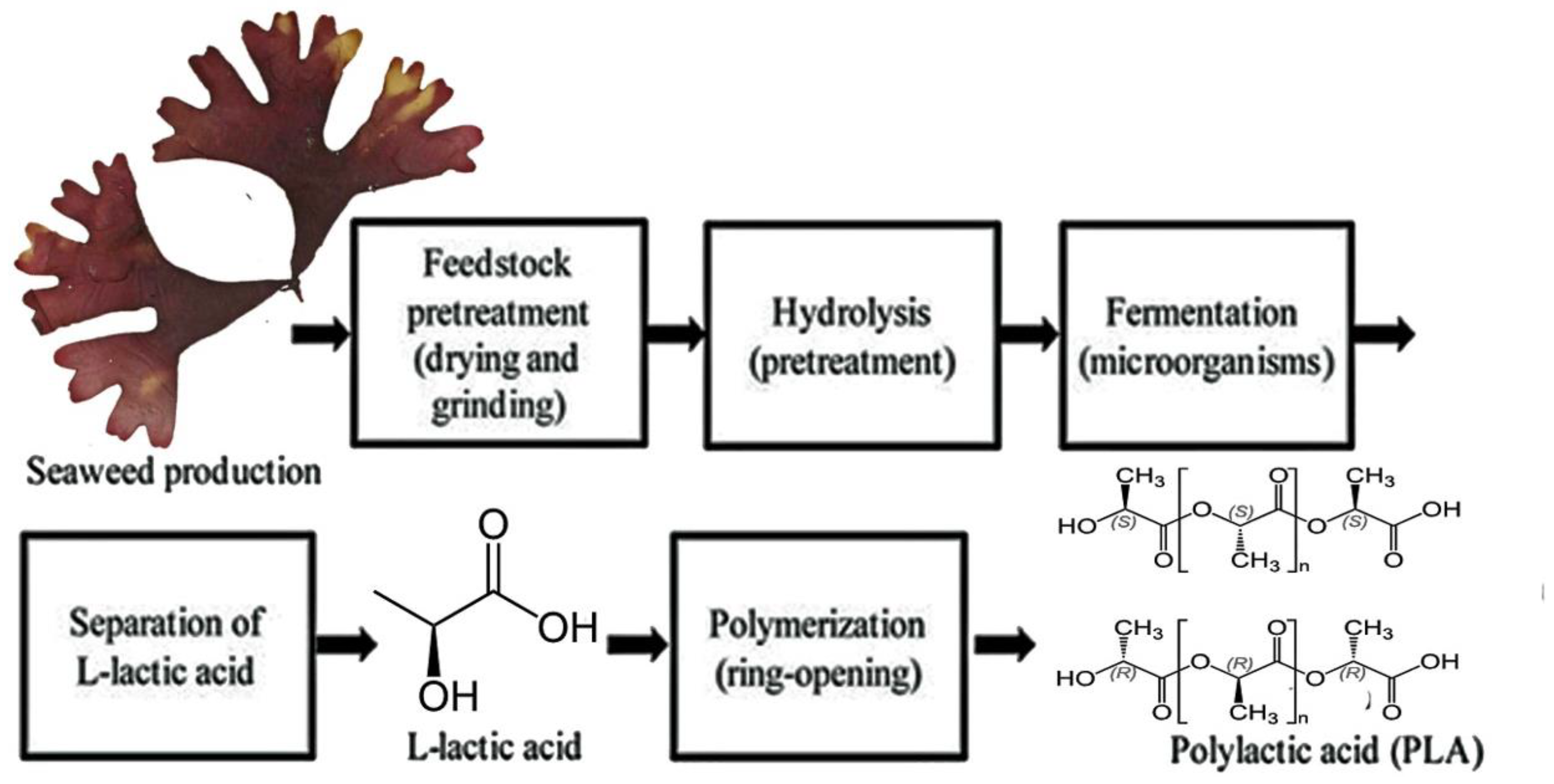

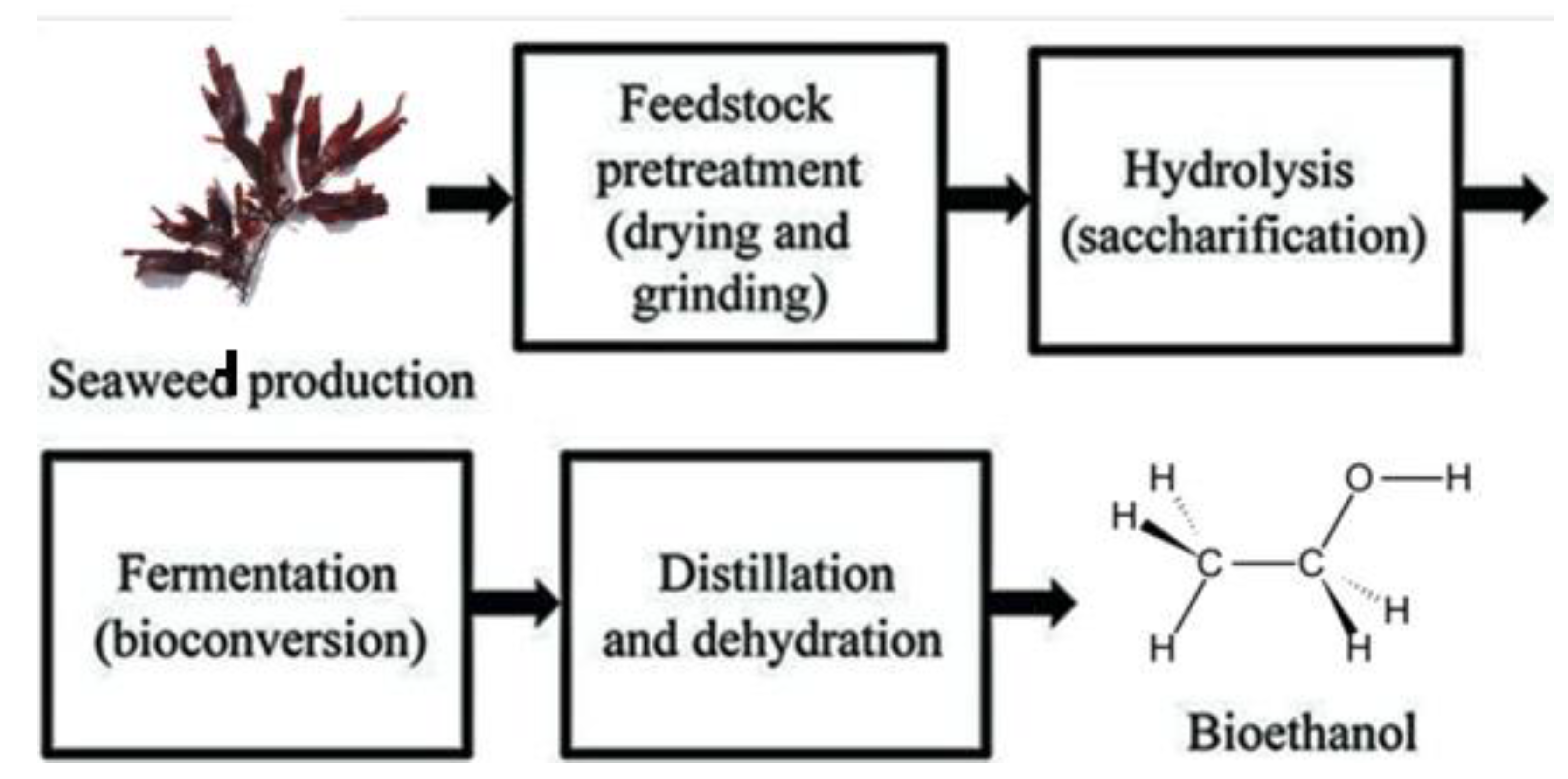

7.2. Seaweed Holds Significant Potential as a Sustainable Energy Source for Drug Manufacturing Processes

8. Conclusions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CO2 - Carbon Dioxide Covid -19 - Corona Virus Disease – 2019 EAE - Enzyme-Assisted Extraction FDA - Food and Drug Administration GDP - Gross Domestic Product GRAS - Generally Recognized as Safe HPAEC - High-Performance Anion Exchange Chromatography IMATA - Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture MAE - Microwave-Assisted Extraction mRNA - messenger RNA PHA - Polyhydroxyalkanoates PLA - Polylactide siRNA - small interfering RNA SRC - Semi-Refined Carrageenan UAE - Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction |

References

- Mendes, M.; Cotas, J.; Pacheco, D.; Ihle, K.; Hillinger, A.; Cascais, M.; Marques, J. C.; Pereira, L.; Gonçalves, A. M. M. , Red Seaweed (Rhodophyta) Phycocolloids: A Road from the Species to the Industry Application. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L. , Macroalgae. Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, M. V.; Pacheco, D.; Cotas, J.; Mouga, T.; Afonso, C.; Pereira, L. , Red Seaweed Pigments from a Biotechnological Perspective. Phycology 2022, 2, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, P.; Carpena, M.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Echave, J.; Soria-Lopez, A.; Garcia-Perez, P.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Cao, H.; Nie, S.; Xiao, J.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Prieto, M. A. , Seaweed polysaccharides: Emerging extraction technologies, chemical modifications and bioactive properties. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci Nutr. 2023, 63, 1901–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kravchenko, A. O.; Byankina Barabanova, A. O.; Glazunov, V. P.; Yakovleva, I. M.; Yermak, I. M. , Seasonal variations in a polysaccharide composition of Far Eastern red seaweed Ahnfeltiopsis flabelliformis (Phyllophoraceae). J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H. P. S. A.; Lai, T. K.; Tye, Y. Y.; Rizal, S.; Chong, E. W. N.; Yap, S. W.; Hamzah, A. A.; Fazita, M. R. N.; Paridah, M. T. A review of extractions of seaweed hydrocolloids: Properties and applications. EXPRESS Polym. Lett. 2018, 12, 296–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafting, J. T.; Craigie, J. S.; Stengel, D. B.; Loureiro, R. R.; Buschmann, A. H.; Yarish, C.; Edwards, M. D.; Critchley, A. T. , Prospects and challenges for industrial production of seaweed bioactives. J. Phycol. 2015, 51, 821–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Poza, S.; Leandro, A.; Cotas, C.; Cotas, J.; Marques, J. C.; Pereira, L.; Gonçalves, A. M. M. , The Evolution Road of Seaweed Aquaculture: Cultivation Technologies and the Industry 4.0. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlander, M. Advances in cultivation of Gelidiales. In Nineteenth International Seaweed Symposium: Proceedings of the 19th International Seaweed Symposium, held in Kobe, Japan, 26-31 March, 2007.; Borowitzka, M. A.; Critchley, A. T.; Kraan, S.; Peters, A.; Sjøtun, K.; Notoya, M., Eds. Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2009; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Buia, M. C.; Palumbo, A.; Mohany, M.; Wadaan, M. A. M.; Hozzein, W. N.; Beemster, G. T. S.; AbdElgawad, H. , Ocean acidification affects biological activities of seaweeds: A case study of Sargassum vulgare from Ischia volcanic CO2 vents. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 259, 113765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roleda, M. Y.; Hurd, C. L. Seaweed nutrient physiology: application of concepts to aquaculture and bioremediation. Phycologia 2019, 58, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-K.; Lim, Y.-Y.; Leow, A. T.-C.; Namasivayam, P.; Ong Abdullah, J.; Ho, C.-L. , Biosynthesis of agar in red seaweeds: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 164, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véliz, K. , Chandía, N., Rivadeneira, M. et al. Seasonal variation of carrageenans from Chondracanthus chamissoi with a review of variation in the carrageenan contents produced by Gigartinales. J. Appl. Phycol. 2017, 29, 3139–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Amado, A. M.; Critchley, A. T.; van de Velde, F.; Ribeiro-Claro, P. J. A. , Identification of selected seaweed polysaccharides (phycocolloids) by vibrational spectroscopy (FTIR-ATR and FT-Raman). Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 1903–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, C.; Correia, A.P.; Freitas, M.V.; Baptista, T.; Neves, M.; Mouga, T. Seasonal Changes in the Nutritional Composition of Agarophyton vermiculophyllum (Rhodophyta, Gracilariales) from the Center of Portugal. Foods 2021, 10, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Cotas, J. , Seaweed: a sustainable solution for greening drug manufacturing in the pursuit of sustainable healthcare. Explor. Drug Sci. 2024, 2, 50–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptak, S. H.; Hjuler, A. L.; Ditlevsen, S. I.; Fretté, X.; Errico, M.; Christensen, K. V. , The effect of seasonality and geographic location on sulphated polysaccharides from brown algae. Aquac. Res. 2021, 52, 6235–6243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theobald, E. J.; Irving, A. D.; Capper, A.; Costa, J. F.; Diaz-Pulido, G.; Andrews, E. L.; Kelly, J.; Jackson, E. L. , Selection of marine macroalgae for nutrient biofilter and bioproduct trials in the coastal waters of Queensland, Australia. Aquac. Int. 2024, 32, 9631–9669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, P.; Carpena, M.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Echave, J.; Soria-Lopez, A.; Garcia-Perez, P.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Cao, H.; Nie, S.; Xiao, J.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Prieto, M. A. , Seaweed polysaccharides: Emerging extraction technologies, chemical modifications and bioactive properties. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2023, 63, 1901–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liao, W.; Huang, Y.; Wen, Y.; Chu, Y.; Zhao, C. , Global seaweed farming and processing in the past 20 years. Food Production, Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2022, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Poza, S.; Leandro, A.; Cotas, C.; Cotas, J.; Marques, J. C.; Pereira, L.; Gonçalves, A. M. M. , The Evolution Road of Seaweed Aquaculture: Cultivation Technologies and the Industry 4.0. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 6528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M. Q.; Azhar, M. A.; Munaim, M. S. A.; Ruslan, N. F.; Alsubhi, L. M.; Ahmad, N.; Noman, A. E. , Seaweed organic compounds source of hydrocolloids and sustainable food packaging: properties, application, and future direction. Discov. Food 2024, 4, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoraj, M.; Çalış, D.; Trzaska, K.; Mironiuk, M.; Chojnacka, K. , Advancements in algal biorefineries for sustainable agriculture: Biofuels, high-value products, and environmental solutions. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 58, 103224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L. , Atlantic algae as food and their extracts. Explor. Foods Foodomics 2023, 1, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, G. A. P. Cultivation of the wild seaweed Gracilaria gracilis under laboratory scale: The Effect of Light Intensity and Nutrients on Growth, Pigment and Total Soluble Protein Content, 2019. Master’s degree Thesis, Escola Superior de Turismo e Tecnologia do Mar, Instituto Politécnico de Leiria, Portugal, 129 pp.

- Pereira, L. , Non-indigenous seaweeds in the Iberian Peninsula, Macaronesia Islands (Madeira, Azores, Canary Islands) and Balearic Islands: Biodiversity, ecological impact, invasion dynamics, and potential industrial applications. Algal Res. 2024, 78, 103407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandro, A.; Pacheco, D.; Cotas, J.; Marques, J.C.; Pereira, L.; Gonçalves, A.M.M. Seaweed’s Bioactive Candidate Compounds to Food Industry and Global Food Security. Life 2020, 10, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurd, C. , Shaken and stirred: the fundamental role of water motion in resource acquisition and seaweed productivity. PiP 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. P.; Singh, P. , Effect of temperature and light on the growth of algae species: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamede, M.; Cotas, J.; Bahcevandziev, K.; Pereira, L. Seaweed Polysaccharides in Agriculture: A Next Step towards Sustainability. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghali, M.; Mohamed, I. M. A.; Osman, A. I.; Rooney, D. W. , Seaweed for climate mitigation, wastewater treatment, bioenergy, bioplastic, biochar, food, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 97–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Sudhakar, K.; Mamat, R. , Macroalgae farming for sustainable future: Navigating opportunities and driving innovation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrier, B.; Rolland, E.; Gupta, V.; Reddy, C. R. K. , Production of genetically and developmentally modified seaweeds: exploiting the potential of artificial selection techniques. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Healy, L.; Zhang, Z.; Maguire, J.; Sun, D.-W.; Tiwari, B. K. , Novel postharvest processing strategies for value-added applications of marine algae. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 4444–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafeuille, B.; Tamigneaux, É.; Berger, K.; Provencher, V.; Beaulieu, L. Impact of Harvest Month and Drying Process on the Nutritional and Bioactive Properties of Wild Palmaria palmata from Atlantic Canada. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, A.; Sobuj, M. K. A.; Islam, M. S.; Chakroborty, K.; Tasnim, N.; Ayon, M. H.; Hossain, M. F.; Rafiquzzaman, S. M. , Seaweed polysaccharides: Sources, structure and biomedical applications with special emphasis on antiviral potentials. Fut. Foods 2024, 10, 100440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Cotas, J.; Gonçalves, A. M. , Seaweed Proteins: A Step towards Sustainability? Nutrients 2024, 16, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Beltagi, H.S.; Mohamed, A.A.; Mohamed, H.I.; Ramadan, K.M.A.; Barqawi, A.A.; Mansour, A.T. Phytochemical and Potential Properties of Seaweeds and Their Recent Applications: A Review. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbar, W. A.; Rahim, H. U.; Rutigliano, F. A. , Microbial- and seaweed-based biopolymers: Sources, extractions and implications for soil quality improvement and environmental sustainability - A review. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 359, 120964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagahawatta, D. P.; Liyanage, N. M.; Jayawardena, T. U.; Yang, F.; Jayawardena, H. H. A. C. K.; Kurera, M. J. M. S.; Wang, F.; Fu, X.; Jeon, Y.-J. , Functions and values of sulfated polysaccharides from seaweed. Algae 2023, 38, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, P.; Levrel, H.; Viard, F.; Frangoudes, K.; Girard, S.; Scemama, P. , Ecosystem services assessment and compensation costs for installing seaweed farms. Marine Policy 2016, 71, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolache, A.I.; Andrei, G. A Comprehensive Review of Multi-Use Platforms for Renewable Energy and Aquaculture Integration. Energies 2024, 17, 4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancarlo, L. C.; Mark, E. H. , Activated chemical defenses in tropical versus temperate seaweeds. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2000, 207, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomartire, S. , Gonçalves. A.M.M. An Overview of Potential Seaweed-Derived Bioactive Compounds for Pharmaceutical Applications. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R. P.; Reddy, C. R. K. , Seaweed–microbial interactions: key functions of seaweed-associated bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 88, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macrae, O. C.; Vickers, C. J. , The significance of microbiota in New Zealand seaweed aquaculture N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2024, 59, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, K.; Kontogiorgos, V., Seaweed Polysaccharides (Agar, Alginate Carrageenan). In Encyclopedia of Food Chemistry, Melton, L.; Shahidi, F.; Varelis, P., Eds. Academic Press: Oxford, 2019; pp 240-250. [CrossRef]

- Sudha, P. N.; Aisverya, S.; Nithya, R.; Vijayalakshmi, K. , Chapter Eight - Industrial Applications of Marine Carbohydrates. In Advances in food and nutrition research, Kim, S.-K., Ed. Academic Press 2014, 73, pp–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Lee, Z. J.; Ye, S.; Barrow, C. J.; Dunshea, F. R.; Suleria, H. A. R. , A Review on Seaweeds and Seaweed-Derived Polysaccharides: Nutrition, Chemistry, Bioactivities, and Applications. Food Rev. Int. 2024, 40, 1312–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.; Obando, J.M.C.; Santos, T.C.d.; Cavalcanti, D.N.; Teixeira, V.L. Abiotic Factors Modulating Metabolite Composition in Brown Algae (Phaeophyceae): Ecological Impacts and Opportunities for Bioprospecting of Bioactive Compounds. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, D.; Cotas, J.; Rocha, C. P.; Araújo, G. S.; Figueirinha, A.; Gonçalves, A. M. M.; Bahcevandziev, K.; Pereira, L. , Seaweeds’ carbohydrate polymers as plant growth promoters. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2021, 2, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Dias, J. S.; Romaní, A.; Teixeira, J. A.; Rocha, C. M. R. , Valorization of Seaweed Carbohydrates: Autohydrolysis as a Selective and Sustainable Pretreatment. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 17143–17153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalegerie, F.; Gager, L.; Stiger-Pouvreau, V.; Connan, S., Chapter Eight - The stressful life of red and brown seaweeds on the temperate intertidal zone: effect of abiotic and biotic parameters on the physiology of macroalgae and content variability of particular metabolites. In Advances in Botanical Research, Bourgougnon, N., Ed. Academic Press: 2020; Vol. 95, pp 247-287. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.-M.; Aweya, J. J.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Tang, S.; Zhang, W.; Cheong, K.-L. , Bioactive polysaccharides from red seaweed as potent food supplements: a systematic review of their extraction, purification, and biological activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 275, 118696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Liu, H.-Y.; Li, H.; Wu, D.-T.; Zhong, L. L. D.; Gan, R.-Y.; Gao, H. , Recent advances in the influences of drying technologies on physicochemical properties and biological activities of plant polysaccharides. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 13024–13044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-K.; Lim, Y.-Y.; Leow, A. T.-C.; Namasivayam, P.; Abdullah, J. O.; Ho, C.-L. , Factors affecting yield and gelling properties of agar. J. Appl. Phycol. 2017, 29, 1527–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhein-Knudsen, N.; Ale, M. T.; Ajalloueian, F.; Yu, L.; Meyer, A. S. , Rheological properties of agar and carrageenan from Ghanaian red seaweeds. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 63, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomin, V. H. , Structural and functional insights into sulfated galactans: a systematic review. Glycoconj. J. 2010, 27, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, G.S.; Pereira, S.G.; Genisheva, Z.A.; Gomes, A.M.; Teixeira, J.A.; Rocha, C.M.R. Advances in Extraction Methods to Recover Added-Value Compounds from Seaweeds: Sustainability and Functionality. Foods 2021, 10, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.-K.; Lim, Y.-Y.; Leow, A. T.-C.; Namasivayam, P.; Ong Abdullah, J.; Ho, C.-L. , Biosynthesis of agar in red seaweeds: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 164, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Astráin, B.; Sainz-Villegas, S.; Guinda, X.; Fernández de la Hoz, C.; Juanes, J. A. , Assessment of the growth capacity of newly sprouted shoots of Gelidium corneum (Florideophyceae, Rhodophyta) through field-based experiments. Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 202, 106781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castejón, N.; Parailloux, M.; Izdebska, A.; Lobinski, R.; Fernandes, S.C.M. Valorization of the Red Algae Gelidium sesquipedale by Extracting a Broad Spectrum of Minor Compounds Using Green Approaches. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, F.; Xiao, A. Pretreatment Techniques and Green Extraction Technologies for Agar from Gracilaria lemaneiformis. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, S. , 18 - Ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted extraction and modification of algal components. In Functional Ingredients from Algae for Foods and Nutraceuticals, Domínguez, H., Ed. Woodhead Publishing: 2013; pp 585-605. [CrossRef]

- Soto, D. (Ed.). Integrated mariculture: a global review, 2009. FAO Fish. Tech. Pap. No. 529. Rome, FAO. 2009. 183 p. ISBN 978-92-5-106387-3.

- Matos, C.; Moreira, M.M.; Loureiro, H.; Gomes, L.R. Demystifying E407 and E407a Additives (Carrageenans) Through Their Gastronomic Alchemy: A Contribution to Increase Consumer Sovereignty. Gastronomy 2024, 2, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, M.; Aggett, P.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; Filipič, M.; Frutos, M. J.; et al. , Re-evaluation of carrageenan (E 407) and processed Eucheuma seaweed (E 407a) as food additives. EFSA Journal 2018, 16, e05238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Necas, J.; Bartosikova, L. Carrageenan: a review. Vet. Med-Czech. 2013, 58, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, M.; Cotas, J.; Gutiérrez, I.B.; Gonçalves, A.M.M.; Critchley, A.T.; Hinaloc, L.A.R.; Roleda, M.Y.; Pereira, L. Advanced Extraction Techniques and Physicochemical Properties of Carrageenan from a Novel Kappaphycus alvarezii Cultivar. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomartire, S.; Gonçalves, A.M.M. Novel Technologies for Seaweed Polysaccharides Extraction and Their Use in Food with Therapeutically Applications — A Review. Foods 2022, 11, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarman, K.; Sadi, U.; Santoso, J.; Hardjito, L. , Carrageenan and its Enzymatic Extraction. In Encyclopedia of Marine Biotechnology, 2020; pp 147-159. 147-159. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Viñas, M.; Rivas, S.; Torres, M.D.; Domínguez, H. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Carrageenan from Sarcopeltis skottsbergii. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heriyanto, H.; Kustiningsih, I.; Sari, D. , The effect of temperature and time of extraction on the quality of Semi Refined Carrageenan (SRC). MATEC Web of Conferences 2018, 154, 01034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, J.; Gerhäuser, J.; Gaukel, V.; Wefers, D. , Commercially available carrageenans show broad variation in their structure, composition, and functionality. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 2989–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafie, M. H.; Kamal, M. L.; Zulkiflee, F. F.; Hasan, S.; Uyup, N. H.; Abdullah, S.; Mohamed Hussin, N. A.; Tan, Y. C.; Zafarina, Z. , Application of Carrageenan extract from red seaweed (Rhodophyta) in cosmetic products: A review. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2022, 99, 100613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomartire, S.; Gonçalves, A.M.M. Algal Phycocolloids: Bioactivities and Pharmaceutical Applications. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvizu-Higuera, D.L.; Rodríguez-Montesinos, Y.E.; Murillo-Álvarez, J.I.; Muñoz-Ochoa, M.; Hernández-Carmona, G. Effect of alkali treatment time and extraction time on agar from Gracilaria vermiculophylla. J. Appl. Phycol. 2008, 20, 515–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, L.; Tiwari, B.; Garcia-Vaquero, M. , Chapter 9 - Emerging extraction techniques: Microwave-assisted extraction. In Sustainable Seaweed Technologies, Torres, M. D.; Kraan, S.; Dominguez, H., Eds. Elsevier: 2020; pp 207-224. [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, R. D.; Sousa, A. M. M.; Gonçalves, M. P.; Nilsson, M.; Hilliou, L. , Production and properties of agar from the invasive marine alga, Gracilaria vermiculophylla (Gracilariales, Rhodophyta). J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 22, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, K. H. M.; Guaratini, T.; Barros, M. P.; Falcão, V. R.; Tonon, A. P.; Lopes, N. P.; Campos, S.; Torres, M. A.; Souza, A. O.; Colepicolo, P.; Pinto, E. , Metabolites from algae with economical impact. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2007, 146, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Carmona, G.; Freile-Pelegrín, Y.; Hernández-Garibay, E. Conventional and alternative technologies for the extraction of algal polysaccharides. In Functional Ingredients from Algae for Foods and Nutraceuticals; Dominguez, H., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2013; pp. 475–516. ISBN 9780857095121. [Google Scholar]

- Rupert, R.; Rodrigues, K. F.; Thien, V. Y.; Yong, W. T. L. , Carrageenan from Kappaphycus alvarezii (Rhodophyta, Solieriaceae): Metabolism, Structure, Production, and Application. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, J.; Anandhakumar, R.; Shanmugam, M. (2015). Effect of alkaline treatment on the sulfate content and quality of semi-refined carrageenan prepared from seaweed Kappaphycus alvarezii Doty (Doty) farmed in Indian waters. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 14, 1584–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L. , Bioactivities, isolation and purification methods of polysaccharides from natural products: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 92, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M. A.; Jaafar, J.; Ismail, A. F.; Othman, M. H. D.; Rahman, M. A. , Chapter 1 - Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy. In Membrane Characterization, Hilal, N.; Ismail, A. F.; Matsuura, T.; Oatley-Radcliffe, D., Eds. Elsevier: 2017; pp 3-29. 3-29. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, P.; Cotas, J.; Pacheco, D.; Figueirinha, A.; da Silva, G. J.; Pereira, L.; Gonçalves, A. M. M., Seaweed as Food: How to Guarantee Their Quality? In Sustainable Global Resources of Seaweeds Volume 2: Food, Pharmaceutical and Health Applications, Ranga Rao, A.; Ravishankar, G. A., Eds. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp 309-321. [CrossRef]

- Cherniienko, A.; Lesyk, R.; Zaprutko, L.; Pawełczyk, A. , IR-EcoSpectra: Exploring sustainable ex situ and in situ FTIR applications for green chemical and pharmaceutical analysis. J. Pharm. Anal. 2024, 14, 100951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ordóñez, E.; Rupérez, P. FTIR-ATR spectroscopy as a tool for polysaccharide identification in edible brown and red seaweeds. Food Hydrocoll. 2011, 25, 1514–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Yin, J.-Y.; Nie, S.-P.; Xie, M.-Y. Applications of infrared spectroscopy in polysaccharide structural analysis: Progress, challenge and perspective. Food Chem.: X 2021, 12, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandanjon, L.; Burlot, A.-S.; Zamanileha, E.F.; Douzenel, P.; Ravelonandro, P.H.; Bourgougnon, N.; Bedoux, G. The Use of FTIR Spectroscopy as a Tool for the Seasonal Variation Analysis and for the Quality Control of Polysaccharides from Seaweeds. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, C.; Moreira, M.M.; Loureiro, H.; Gomes, L.R. Demystifying E407 and E407a Additives (Carrageenans) Through Their Gastronomic Alchemy: A Contribution to Increase Consumer Sovereignty. Gastronomy 2024, 2, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashedy, S.H.; Abd El Hafez, M.S.M.; Dar, M.A.; Cotas, J.; Pereira, L. Evaluation and Characterization of Alginate Extracted from Brown Seaweed Collected in the Red Sea. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotas, J.; Tavares, J.O.; Silva, R.; Pereira, L. Seaweed as a Safe Nutraceutical Food: How to Increase Human Welfare? Nutraceuticals 2024, 4, 323–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Nakagawa, M.; Cheng, S. Emerging Trends in Green Extraction Techniques for Bioactive Natural Products. Processes 2023, 11, 3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Chaudhary, K.; Amin, S.; Raana, S.; Zahid, M.; Naeem, M.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A.; Aadil, R. M. , Recent advances in the implementation of ultrasound technology for the extraction of essential oils from terrestrial plant materials: A comprehensive review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 107, 106914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noelia, F.; Maria Jesus, G.-M.; Daniela, R.; Eduarda, F.; Herminia, D.; Marisa, F. , Algae Polysaccharides’ Chemical Characterization and their Role in the Inflammatory Process. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, M. Novel Extraction Methods, Yield, Structural and Rheological Properties of Carrageenan from Novel Kappaphycus alvarezii Strains from the Philippines. Master Dissertation, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal, 2023, 142 p. (Available online at: https://estudogeral.uc.pt/retrieve/265167/Disserta%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20Corrigida%20-%20Madalena%20Miguel%20Memdes%20Afonso.pdf (Accessed on October 22, 2025).

- Pangestuti, R.; Kim, S.-K. , An Overview of Phycocolloids: The Principal Commercial Seaweed Extracts. In Marine Algae Extracts, S.-K. Kim and K. Chojnacka eds. 2015; pp. 319-330. [CrossRef]

- Holdt, S. L.; Kraan, S. , Bioactive compounds in seaweed: functional food applications and legislation. J. Appl. Phycol. 2011, 23, 543–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Critchley, A. T. , The COVID 19 novel coronavirus pandemic 2020: seaweeds to the rescue? Why does substantial, supporting research about the antiviral properties of seaweed polysaccharides seem to go unrecognized by the pharmaceutical community in these desperate times? J. Appl. Phycol. 2020, 32, 1875–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carina, D.; Sharma, S.; Jaiswal, A. K.; Jaiswal, S. , Seaweeds polysaccharides in active food packaging: A review of recent progress. TIFS 2021, 110, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Gao, X.; Cheng, C.; Liu, C.; Wang, Q.; Han, X. The Structural Characteristics of Seaweed Polysaccharides and Their Application in Gel Drug Delivery Systems. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babich, O.; Sukhikh, S.; Larina, V.; Kalashnikova, O.; Kashirskikh, E.; Prosekov, A.; Noskova, S.; Ivanova, S.; Fendri, I.; Smaoui, S.; et al. Algae: Study of Edible and Biologically Active Fractions, Their Properties and Applications. Plants 2022, 11, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L. (Ed.) Therapeutic and Nutritional Uses of Algae; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781315152844. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, D.J. A Guide to the Seaweed Industry; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2003; ISBN 9251049580. [Google Scholar]

- Udo, T.; Mummaleti, G.; Mohan, A.; Singh, R. K.; Kong, F. , Current and emerging applications of carrageenan in the food industry. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, S.; Singh, R.; Bhardwaj, S. K.; Sami, R.; Nikolova, M. P.; Chavali, M.; Sinha, S. Perspective on the therapeutic applications of algal polysaccharides. J. Polym. Environ. 2022, 30, 785–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanna, B.; Mishra, A. Nutraceutical Potential of Seaweed Polysaccharides: Structure, Bioactivity, Safety, and Toxicity. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, L. A review of the nutrient composition of selected edible seaweeds. In Seaweed: Ecology, Nutrient Composition and Medicinal Uses; Pomin, V.H., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-61470-878-0. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Zhan, X.; Wan, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C. Review for carrageenan-based pharmaceutical biomaterials: Favourable physical features versus adverse biological effects. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 121, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Hortas, L.; Flórez-Fernández, N.; Torres, M.D.; Ferreira-Anta, T.; Casas, M.P.; Balboa, E.M.; Falqué, E.; Domínguez, H. Applying Seaweed Compounds in Cosmetics, Cosmeceuticals and Nutricosmetics. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, L. Seaweeds as source of bioactive substances and skin care therapy-cosmeceuticals, algotheraphy, and thalassotherapy. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboa, E.M.; Conde, E.; Soto, M.L.; Pérez-Armada, L.; Domínguez, H. Cosmetics from Marine Sources BT. In Springer Handbook of Marine Biotechnology; Kim, S.-K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 1015–1042. ISBN 978-3-642-53971-8. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, S.; Chaudhary, K.; Malik, A.; Punia, H.; Sewhag, M.; Berkesia, N.; Nagora, M.; Kalia, S.; Malik, K.; Kumar, D.; et al. Superabsorbent Polymers as a Soil Amendment for Increasing Agriculture Production with Reducing Water Losses under Water Stress Condition. Polymers 2023, 15, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P. S.; Borza, T.; Critchley, A. T.; Prithiviraj, B. , Carrageenans from Red Seaweeds as Promoters of Growth and Elicitors of Defense Response in Plants. Front. Mar. Sci. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, M.; Allahgholi, L.; Sardari, R.R.R.; Hreggviðsson, G.O.; Nordberg Karlsson, E. Extraction and Modification of Macroalgal Polysaccharides for Current and Next-Generation Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotas, J.; Lourenço, M.; Figueirinha, A.; Valado, A.; Pereira, L. Seaweed Polysaccharides: A Rational Approach for Food Safety Studies. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Sheikh, M. A.; Ubaid, M.; Chauhan, P.; Kumar, K.; Choudhary, S. , Comprehensive exploration of marine algae diversity, bioactive compounds, health benefits, regulatory issues, and food and drug applications. Measurement: Food 2024, 14, 100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, F.; Wahab, M. A.; Nahiduzzaman, M.; Mohiuddin, M.; Iqbal, M. Z.; Shakil, A.; Mamun, A.-A.; Khan, M. S. R.; Wong, L.; Asaduzzaman, M. , Seaweed farming for food and nutritional security, climate change mitigation and adaptation, and women empowerment: A review. Aquac. Fish. 2023, 8, 463–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, S.; Jüterbock, A. O.; Lei, X.; Khanal, P. , Application of the brown macroalga Saccharina latissima (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae) as a feed ingredient for livestock: A review. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 19, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makkar, H. P. S.; Tran, G.; Heuzé, V.; Giger-Reverdin, S.; Lessire, M.; Lebas, F.; Ankers, P. , Seaweeds for livestock diets: A review. AFST 2016, 212, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B. R.; Parker, D.; Brauer, D.; Waldrip, H.; Lockard, C.; Hales, K.; Akbay, A.; Augyte, S. , The role of seaweed as a potential dietary supplementation for enteric methane mitigation in ruminants: Challenges and opportunities. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 1371–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Meza, G.M.; Elizondo-Luevano, J.H.; Cuellar-Bermudez, S.P.; Sosa-Hernández, J.E.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Parra-Saldívar, R. New Perspective for Macroalgae-Based Animal Feeding in the Context of Challenging Sustainable Food Production. Plants 2023, 12, 3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, T.; Inácio, A.; Coutinho, T.; Ministro, M.; Cotas, J.; Pereira, L.; Bahcevandziev, K. Seaweed Potential in the Animal Feed: A Review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebours, C.; Marinho-Soriano, E.; Zertuche-González, J. A.; Hayashi, L.; Vásquez, J. A.; Kradolfer, P.; Soriano, G.; Ugarte, R.; Abreu, M. H.; Bay-Larsen, I.; Hovelsrud, G.; Rødven, R.; Robledo, D. , Seaweeds: an opportunity for wealth and sustainable livelihood for coastal communities. J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 1939–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadzama, I. , Red Seaweed: A Promising Solution for Sustainable Ruminant Production. MCAES 2024, 7, 6–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanapat, M.; Prachumchai, R.; Dagaew, G.; Matra, M.; Phupaboon, S.; Sommai, S.; Suriyapha, C. , Potential use of seaweed as a dietary supplement to mitigate enteric methane emission in ruminants. STOTEN 2024, 931, 173015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Viñas, M.; Souto, S.; Flórez-Fernández, N.; Torres, M.D.; Bandín, I.; Domínguez, H. Antiviral Activity of Carrageenans and Processing Implications. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z. U.; Hasan, O.; Rahman, M. M.; Akter, M.; Rahman, M. S.; Sarker, S. , Seaweeds for the sustainable blue economy development: A study from the south east coast of Bangladesh. Heliyon 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesan, J.; Lowe, B.; Anil, S.; Manivasagan, P.; Kheraif, A. A. A.; Kang, K.-H.; Kim, S.-K., Seaweed polysaccharides and their potential biomedical applications. Starch - Stärke 2015, 67 (5-6), 381-390. [CrossRef]

- Lomartire, S. , Gonçalves. A.M.M. An Overview of Potential Seaweed-Derived Bioactive Compounds for Pharmaceutical Applications. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falshaw, R.; Bixler, H. J.; Johndro, K. , Structure and performance of commercial κ-2 carrageenan extracts. Part III. Structure analysis and performance in two dairy applications of extracts from the New Zealand red seaweed, Gigartina atropurpurea. Food Hydrocoll. 2003, 17, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Duan, G.; Yang, H. , Recent advances in exploiting carrageenans as a versatile functional material for promising biomedical applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 235, 123787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfinaikh, R. S.; Alamry, K. A.; Hussein, M. A. , Sustainable and biocompatible hybrid materials-based sulfated polysaccharides for biomedical applications: a review. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 4708–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Gulraiz, Y.; Ilyas, S.; Bashir, S. , Polysaccharide based nano materials: Health implications. Food Hydrocoll. Health 2022, 2, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Quito, E.-M.; Ruiz-Caro, R.; Veiga, M.-D. Carrageenan: Drug Delivery Systems and Other Biomedical Applications. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aga, M. B.; Dar, A. H.; Nayik, G. A.; Panesar, P. S.; Allai, F.; Khan, S. A.; Shams, R.; Kennedy, J. F.; Altaf, A. , Recent insights into carrageenan-based bio-nanocomposite polymers in food applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 192, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aga, M. B.; Dar, A. H.; Nayik, G. A.; Panesar, P. S.; Allai, F.; Khan, S. A.; Shams, R.; Kennedy, J. F.; Altaf, A. , Recent insights into carrageenan-based bio-nanocomposite polymers in food applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 192, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhao, J.; Hu, F.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, H.; Pan, S.; Shi, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, S. , Design of injectable agar-based composite hydrogel for multi-mode tumor therapy. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 180, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alboofetileh, M.; Rezaei, M.; Hosseini, H.; Abdollahi, M. , Efficacy of activated alginate-based nanocomposite films to control Listeria monocytogenes and spoilage flora in rainbow trout slice. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, Y.; Bakshi, M.; Sharma, A., Agar-agar extraction, structural properties and applications: A review. The Pharma Journal 2022, 11, 1151-1157. Available online at: https://www.thepharmajournal.com/archives/2022/vol11issue6S/PartO/S-11-6-106-220.pdf) (Accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Onyeaka, H. N.; Nwabor, O. F. , Chapter 9 - Natural active components in smart food packaging system. In Food Preservation and Safety of Natural Products, Onyeaka, H. N.; Nwabor, O. F., Eds. Academic Press: 2022; pp 119-131. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.R.V.; Alves, V.D.; Coelhoso, I.M. Polysaccharide-Based Membranes in Food Packaging Applications. Membranes 2016, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, D.; Lall, A.; Kumar, S.; Patil, T. D.; Gaikwad, K. K. , Plant-based edible films and coatings for food-packaging applications: recent advances, applications, and trends. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 1428–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, I.; Ye, H.; Aayush, K.; Yang, T., Chapter Seven - Intelligent food packaging for smart sensing of food safety. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research, Lu, X., Ed. Academic Press: 2024; Vol. 111, pp. 215-259. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, S.; Hong, H.; Zhang, L.; Luo, Y. , Spoilage-related microbiota in fish and crustaceans during storage: Research progress and future trends. CRFSFS 2021, 20, 252–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzibra, A.; Aasfar, A.; El Arroussi, H.; Khouloud, M.; Dhiba, D.; Kadmiri, I. M.; Bamouh, A. , Polysaccharides extracted from Moroccan seaweed: a promising source of tomato plant growth promoters. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 2953–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abotaleb, S.I.; Gheda, S.F.; Allam, N.G.; El-Shatoury, E.H.; Cotas, J.; Pereira, L.; Saeed, A.M. Biosynthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using Seaweed: Exploring Their Therapeutic Potentials. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, J. K.; Das, G.; Fraceto, L. F.; Campos, E. V. R.; Rodriguez-Torres, M. d. P.; Acosta-Torres, L. S.; Diaz-Torres, L. A.; Grillo, R.; Swamy, M. K.; Sharma, S.; Habtemariam, S.; Shin, H.-S. , Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. J. Nanobiotechnology 2018, 16, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, J.T.; Lopez, D. , Pharmacogenetics: An Important Part of Drug Development with A Focus on Its Application. Int. J. Biomed. Investig. 2018, 1, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rang, H. P.; LeVine, H.; Hill, R. , Chapter 3 - Therapeutic modalities. In Drug Discovery and Development (Second Edition), Hill, R. G.; Rang, H. P., Eds. Churchill Livingstone: 2013; pp. 33-40. [CrossRef]

- Rajabzadeh, N.; Fathi, E.; Farahzadi, R. , Stem cell-based regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Investig. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Li, S.; Han, S.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Y. , Antibody drug conjugate: the “biological missile” for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Tenchov, R.; Sasso, J. M.; Zhang, D.; Li, D.; Zou, L.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q. , Messenger RNA-Based Therapeutics and Vaccines: What’s beyond COVID-19? ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2023, 6, 943–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauf, A.; Ahmad, Z.; Naz, S.; Hemeg, H. A. , Introduction to Drug Repurposing: Exploring New Applications for Existing Drugs. In Drug Development and Safety, Rauf, A., Ed. IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tani, H. Recent Advances and Prospects in RNA Drug Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balina, K.; Romagnoli, F.; Blumberga, D. Seaweed biorefinery concept for sustainable use of marine resources. Energy Procedia 2017, 128, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardilhó, S.; Cotas, J.; Pacheco, D.; Gonçalves, A.M.M.; Bahcevandziev, K.; Pereira, L.; Figueirinha, A.; Dias, J.M. Valorisation of marine macroalgae waste using a cascade biorefinery approach: Exploratory study. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardilhó, S.; Cotas, J.; Pereira, L.; Oliveira, M.B.; Dias, J.M. Marine macroalgae in a circular economy context: A comprehensive analysis focused on residual biomass. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 60, 107987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschmann, A. H.; Camus, C.; Infante, J.; Neori, A.; Israel, Á.; Hernández-González, M. C.; Pereda, S. V.; Gomez-Pinchetti, J. L.; Golberg, A.; Tadmor-Shalev, N.; Critchley, A. T. , Seaweed production: overview of the global state of exploitation, farming and emerging research activity. Eur. J. Phycol. 2017, 52, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, A.; Feijoo, G.; Moreira, M. T. , Macroalgae biorefineries as a sustainable resource in the extraction of value-added compounds. Algal Res. 2023, 69, 102954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesinghe, W. A. J. P.; Jeon, Y.-J. , Enzyme-assistant extraction (EAE) of bioactive components: A useful approach for recovery of industrially important metabolites from seaweeds: A review. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, M.; Khan, M. U.; Majeed, Y.; Ntsefong, G. N.; Kirichenko, I.; Klopova, A.; Trushov, P.; Lodygin, A. , Seaweed-based films for sustainable food packaging: properties, incorporation of essential oils, applications, and future directions. Potr. S. J. F. Sci. 2023, 17, 899–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesic, A.; Meseldzija, S.; Benavides, S.; Figueroa, F.A.; Cabrera-Barjas, G. Seaweed as a Valuable and Sustainable Resource for Food Packaging Materials. Foods 2024, 13, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carina, D.; Sharma, S.; Jaiswal, A. K.; Jaiswal, S. , Seaweeds polysaccharides in active food packaging: A review of recent progress. TIFS 2021, 110, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Valado, A. Harnessing the power of seaweed: unveiling the potential of marine algae in drug discovery. Explor. Drug Sci. 2023, 1, 475–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eswar, I.; Majumder, A.; Raja mohamed, S. H.; Logesh, K.; Shek alavudeen, S. M. I.; Hariprakash, M.; Sundarraj, D. K. , Seaweed responses to ocean acidification: global impacts on growth, biochemical composition, and CO2 mitigation potential. Discov. Ocean. 2025, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiamurthy, J.; V. , G. R.; Gopal, R. K., Production and Evaluation of a Seaweed-Based Bioplastic Sheet for Food Packaging. UPJOZ 2024, 45, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Dubey, S.; Singh, K.; Mittal, R.; Quille, P.; Rajauria, G. Innovative Processing and Industrial Applications of Seaweed. Phycology 2025, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Bourgougnon, N.; Lanoisellé, J.-L.; Lendormi, T. Biofuel Production from Seaweeds: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2022, 15, 9395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Ahn, J. W.; Hwang, H.; Lee, S.-B. , Seaweed Biomass Resources in Korea. KSBB Journal 2011, 26, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, S.; Zaky, A.; Wang, Q.; Huang, J.; Abomohra, A. Integrated Marine Biogas: A Promising Approach towards Sustainability. Fermentation 2022, 8, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyper, O. M.; Zendehboudi, S.; Kerton, F. M. , The Sea’s best kept secret: the use of seaweed as a source of biohydrogen for clean and renewable energy. RSC Sustain. 2024, 2, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandra, T. V.; Hebbale, D. , Bioethanol from macroalgae: Prospects and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 117, 109479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harichandan, S. , Harnessing seaweed for biohydrogen production: An integrated ecological and energy framework. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 136, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trif, M.; Rusu, A. V.; Bellahcen, T. O.; Cherifi, O.; El Bakali, M., Sustainable and Cost-Effective Management of Residual Aquatic Seaweed Biomass. Business Opportunity for Seaweeds Biorifineries. In Seaweeds and Seaweed-Derived Compounds: Meeting the Growing Need for Healthy Biologically Active Compounds, Ozogul, F.; Trif, M.; Rusu, A., Eds. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2024; pp 367-396. [CrossRef]

| Industry | Polysaccharide | Main Applications | Specific Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Industry | Agar Carrageenan |

- Food additive (E406, GRAS approved) - Popular in jellies - Food additive (E407, GRAS approved) - Processed meat products Stabilization - Protective coating on fresh-cut packaged food |

- Low-quality agar in food products - High-quality agar in limited food items - Common use as a jellifying agent - Binds milk molecules, retains water - Gas barrier, reduces respiration, slows discoloration, and maintains texture in packaged foods |

| Pharmaceutical | Agar Carrageenan |

- Pharmaceutical grade growth media - Drug delivery systems - Functional foods with health Benefits - Medical analysis - Pharmaceutical drugs and agents - Functional foods with health benefits |

- Decreases blood glucose, prevents red blood cell Aggregation - Acts as bulking agents in laxatives, suppositories, capsules, tablets, and anticoagulants - Production and encapsulation of monoclonal antibodies, interferons, steroids, and alkaloids - Decreases blood glucose, prevents red blood cell Aggregation - Highly purified agar (agarose) used in molecular biology (electrophoresis, immune diffusion, gel chromatography) |

| Cosmetic | Agar Carrageenan |

Structural ingredients Structural ingredient |

- Used in creams, hand lotions, liquid soap, deodorants, foundation, exfoliant, cleanser, shaving cream, face moisturizer/lotion, acne and anti-aging treatments - Applications include toothpaste, hair wash products, lotions, medications, sun blocks, shaving creams, deodorant sticks, sprays, and foams |

| Agriculture | Agar Carrageenan |

Structural ingredients Functional ingredients Regulates physiological and biochemical processes in plants (e.g., cell division, photosynthesis) |

- Acts as moisture-holding hydrogel, reducing irrigation frequency, improving soil aeration, and limiting erosion - Soil conditioner, improves water retention, soil permeability, and plant performance - Regulates plant metabolic processes, including purine and pyrimidine synthesis, nitrogen and sulfur absorption - Activates plant defense systems, provides resistance to abiotic and biotic stressors |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).