1. Introduction

Sustainability has become a critical focus in global policy, requiring integrated solutions that balance environmental protection, social equity, and economic development (Mosconi et al., 2024; Huang & Akbari, 2024). Within this context, packaging plays a central role. It ensures product integrity, enables logistics, influences consumer behaviour and contributes significantly to environmental pressures (Ibrahim et al., 2022;Coelho, Corona, Ten Klooster, et al., 2020). The definition of packaging by the scientific community has changed over time. It now encompasses any material used to contain, protect, deliver, or preserve products (Mosconi et al., 2024;European Commission, 2022). The primary purpose of packaging is to safeguard products during distribution, storage, transport, trade, and use (Banaeian et al., 2015). Additionally, packaging should be designed to allow for reuse whenever possible (Miao et al., 2023). The growth of international supply chains has resulted in a higher demand for packaging and, consequently, increased waste (Gustavo et al., 2018). The packaging industry has expanded significantly, contributing to global GDP while also putting considerable pressure on environmental systems (Coelho, Corona, ten Klooster, et al., 2020). In many countries, packaging waste accounts for 15 to 20% of total municipal solid waste (Sastre et al., 2022). The European Commission estimates that, without intervention, packaging waste could surpass 100 million tonnes by 2040 (Silva & Pålsson, 2022). This scenario highlights the necessity for strong policy frameworks and innovative strategies for packaging design and lifecycle management. In response to this context, the European Commission has introduced the Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR), which builds on Directive 2018/852/EU. This regulation focuses on five key areas: waste prevention, recyclability, recycled content, compostable packaging, and reusable packaging. It is part of the European Green Deal and the Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP). The goal is to reduce packaging waste, promote a circular economy through optimized design, increase recycled content in packaging materials and promote a functional single market for secondary materials (Regulation of the European Parlament and of the Council on Packaging and Packaging Waste, n.d.). While regulatory ambition is increasing, industry practices often lag behind. Many packaging materials still remain non-recyclable or overly complex in their composition (Geueke et al., 2018). The literature highlight the need to transition towards eco-design principles that minimize the use of virgin resources, prioritize post-consumer recyclates, and ensure effective performance throughout the supply chain (Reichert et al., 2020;Miao et al., 2023). The European Commission also aims to enhance environmental sustainability by setting reduction responsible for the proper disposal of the packaging waste generated by their products (Sumter et al., 2021). This system not only shifts the financial burden from public administration to producers, but also encourages innovation, improves recycling rates, and reduces public costs. However, there are some challenges associated with EPR, such as incomplete cost coverage, administrative complexity, and the need for harmonization. Therefore, careful management is required to ensure the effectiveness of the system (Rigamonti et al., 2014). The regulation imposes limits on hazardous substance concentrations in packaging, requires compliance for market placement, mandates manufacturers to reduce packaging weight and volume while considering safety and functionality (Seier et al., 2023). It also establishes provisions for compostable packaging and introduces specific targets to increase the use of recycled materials in packaging, with a focus on plastic products. Manufacturers are obliged to ensure that a predetermined percentage of plastic material in packaging is derived from post-consumer plastic waste. Recent scientific literature indicates that manufacturers have only recently begun to tackle the issue of overpackaging by implementing concrete initiatives aimed at creating more environmentally sustainable outer packaging (Georgakoudis & Tipi, 2020). Driven by scientific and technological advancements, the integration of circularity principles into packaging design and production processes, supported by regulatory frameworks, compels the industry to adopt policies that promote eco-design and sustainable production practices. This shift represents a crucial step toward more efficient and sustainable resource management (Sumter et al., 2021). Additionally, environmental pressures related to the use of materials and waste generation from disposable packaging necessitate a move away from single-use packaging. Studies suggest that reusable packaging systems have environmental and potential economic benefits over single-use systems (Coelho et al., 2020; Mahmoudi & Parviziomran, 2020; Bradley & Corsini, 2023). Moreover, the importance of packaging design has been emphasized in relation to logistics and environmental performance. Design choices impact fill rates, transportation efficiency, and associated emissions, as extensively reviewed in recent literature (Ahmad et al., 2022). Several systematic literature reviews have explored the drivers and barriers of sustainable packaging, highlighting performance outcomes and industry dynamics, and revealing key factors that influence its adoption and implementation (Afif et al., 2021). Additionally, (Meherishi et al., 2019) noted the importance of sustainable packaging within supply chain management, particularly in the context of the circular economy. They emphasized that aligning design strategies with logistics can enhance both environmental and economic benefits. As a result, manufacturers and retailers have a significant impact on developing future packaging policies and directly influence the market (Joltreau, 2022). The importance of designing packaging with an eco-design approach takes on further significance within the supply chain system, with significant impacts on logistics costs and environmental sustainability (Silva & Pålsson, 2022). Eco-design and sustainable packaging are crucial for minimizing the environmental impact of products. Ecodesign optimizes the life cycle of products, reducing their negative effects on the environment by using fewer resources and limiting harmful emissions. Innovations in packaging design aimed at making packaging environmentally friendly would benefit manufacturers, transport companies, and meet consumer expectations focused on sustainability (Ilg, 2019). By adopting eco-design and sustainable packaging, significant contributions can be made towards preserving the planet for future generations (Zimon et al., 2019.). An alignment between science and policymakers is essential for achieving a transition towards sustainable packaging. Despite the extensive research on sustainable packaging, there remains a lack of clarity regarding how well this academic work aligns with the specific priorities and requirements outlined in the PPWR. Although numerous literature reviews have explored various aspects of sustainability in packaging, such as material innovation, environmental impacts, and economic considerations, these analyses are often conducted in isolation and do not explicitly reference or systematically link their findings to the structured intervention areas and policy goals established by the PPWR. Consequently, there is a significant gap in understanding whether and how current scientific findings are necessary to address unresolved policy challenges. Previous research has begun to explore these intersections. Tarantino et al. (2023) conducted a systematic review focusing on the transition to sustainable packaging in alignment with EU regulations. Their work revealed that scientific evidence regarding packaging materials and end-of-life treatment often does not connect effectively with policy design. In parallel, Mosconi et al. (2024) proposed regulatory and technical strategies aimed at enhancing packaging waste management in compliance with EU requirements. This paper builds upon earlier studies (Mosconi et al., 2024; Tarantino et al., 2023) and seeks to provide a broader and more integrative analytical framework. However, there is still a lack of comprehensive mapping of the literature that aligns directly with the five pillars of the PPWR. The lack of alignment creates a knowledge gap: it is unclear to what extent scientific literature supports the implementation of the PPWR and where further research is needed to tackle its policy challenges. To address this issue, the present study conducts a systematic literature review specifically focused on the five intervention areas defined by the Regulation: waste prevention, recyclability, recycled content, compostable packaging, and reusable packaging. Due to the complex nature of packaging sustainability (Sazdovski et al., 2022), this sector requires ongoing research and a multidisciplinary approach to effectively address its environmental, financial, and regulatory challenges. Most existing studies focus on individual areas rather than providing a holistic perspective. This examination will take place within the context of the First Action Plan for the Circular Economy (CEAP) introduced in 2015. Each intervention area will be evaluated concerning the various areas for improvement identified through the examination of different articles (Silva & Pålsson, 2022). The focus will be on reducing environmental impact, optimizing supply chain efficiency, enhancing the packaging development process and ensuring compliance with existing regulations. This approach aims to identify current and future opportunities for the packaging industry from both industrial and circular economy perspectives. Additionally, the study seeks to establish a relationship between the areas of intervention identified by the Regulation and the existing scientific and economic literature on packaging. This connection will promote the effective implementation of circular economy concepts. The research will also explore critical aspects such as innovation, sustainability, and producer responsibility, which are vital for waste prevention, packaging minimization, reuse, and recycling. Furthermore, it will examine factors influencing not only the packaging sector but also aspects of marketing and design, which are often driven by aesthetic considerations or the desire to enhance product attractiveness (Politis et al., 2019). To guide this investigation and provide a structured analysis, the following research questions have been formulated:

RQ1: To what extent does current academic literature address the five intervention areas defined by the PPWR, specifically, waste prevention, recyclability, recycled content, compostable packaging, and reusable packaging?

RQ2: How are the four improvement dimensions, environmental impact, supply chain efficiency, packaging development, and regulatory compliance, addressed in the academic literature across the five PPWR intervention areas?

RQ3: What are the key research gaps that may limit the successful implementation of the PPWR? How can academic literature promote innovation, Extend Producer Responsibility and integrate circular economy principles into packaging policies and practices?

2. Methodology

This paper seeks to explore how the intervention priorities set by the European Commission, including Waste Prevention, Recyclability, Recycled Content, Compostable Packaging, and Reusable Packaging, are reflected in the academic literature and aligned with the objectives of the Regulation. Each intervention area will be evaluated concerning the various areas for improvement identified through the examination of different articles enhancements (Silva & Pålsson, 2022). The emphasis will be on minimise environmental impact, improve supply chain efficiency, enhance packaging development process and ensure compliance with existing regulations. To conduct the Systematic Literature Review (SLR), this paper adopts the PSALSAR frameworkproposed by Mengist et al., 2019). The process unfolds across six sequential steps, namely: (i) Protocol, which involves defining the purpose of the study; (ii) Search, which entails determining the best approach to use when collecting papers; (iii) Appraisal, which involves selecting papers based on specific criteria; (iv) Synthesis, which involves cataloguing the papers; (v) Analysis, which involves analyzing the papers; and (vi) Report, which involves presenting a clear and concise overview of the entire systematic literature review (SLR) process for all interested parties. Steps (i) to (iv) are discussed in this document, while step (v) is explained in section 3 and steps (vi) are discussed in sections 4 and 5.

In order to establish the purpose of this study during the protocol phase, the CIMO methodology is used, which stands for context, intervention, mechanism, and outcome. This approach involves using interventions in a given context to generate mechanisms that ultimately lead to desired outcomes (Denyer & Tranfield, 2009.). By following this methodology, we were able to gain a comprehensive understanding of the study and guide our research accordingly with

Table 1.

To gather relevant academic contributions, the search process utilized two prominent scientific databases: Scopus and ScienceDirect. We developed ten distinct search queries using carefully chosen keywords that align with the thematic priorities of the European Regulation. The review process adhered to the principles of the PRISMA framework, which, includes several key phases: identification, screening, eligibility determination, data extraction, quality assessment, data analysis and reporting. In the identification stage, the search strings were constructed around the core intervention areas outlined by the EU Regulation (

Table 2).

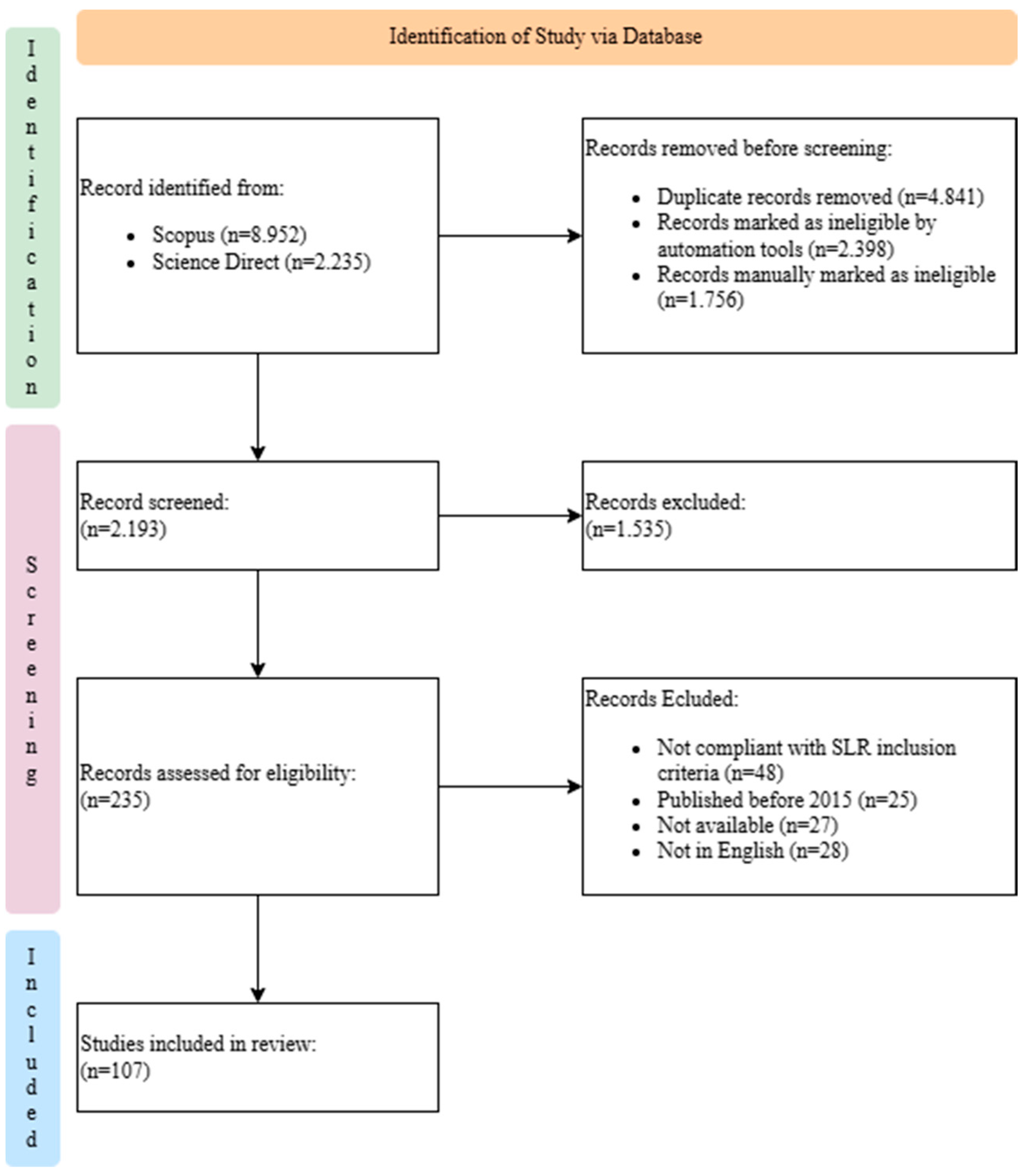

The search process identified a total of 11.188 potentially relevant documents for the literature review, 8.953 from Scopus and 2.235 from ScienceDirect. Once the documents were collected, they were accompanied by relevant information and corresponding abstracts. To streamline the screening process, all records were uploaded into the Rayyan platform, following the methodology suggested by Pellegrini & Marsili (2021). To ensure consistency and transparency during the selection phase, a set of eligibility criteria was established (

Table 3). Only peer-reviewed journal articles and review papers were included. Other document types such as conference papers, book chapters, and editorials were excluded to ensure quality. The review considered only English-language articles for consistency and accessibility. Additionally, the inclusion criteria restricted the selection to articles published within the last decade, specifically from 2015 to 2024. This time frame was chosen to capture developments in academic research after European Commission adopted the First Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP) in 2015. Consequently, only articles published from 2015 were included for further analysis.

The selection of articles for inclusion in the SLR was conducted using the Rayyan platform, based on predefined eligibility criteria. This process followed a structured workflow by the PRISMA flowchart (

Figure 1), ensuring a transparent and replicable methodology. The screening process was divided into several stages:

The inclusion criteria for the SLR were established in

Table 4. This process involved translating the areas of intervention outlined in the European Regulation on packaging into technical and scientific language. This translation allowed for a thorough analysis of the remaining 339 articles, enabling us to determine which articles should be included or excluded.

At the end of the screening process, 107 articles were identified, which represents 1.67% of the total initial articles, excluding duplicates. These selected articles were analyzed concerning the improvements highlighted in the European Commission’s impact assessment. The analysis specifically focused on the reduction of environmental impact, optimization of supply chain efficiency, enhancement of the packaging development process and compliance with existing regulations.

Among the selected articles, the Journal of Cleaner Production emerged as the most frequently international journal with the highest number of cited papers in this SLR, with 18 articles. This was followed by Sustainability, which accounted for 13 articles (

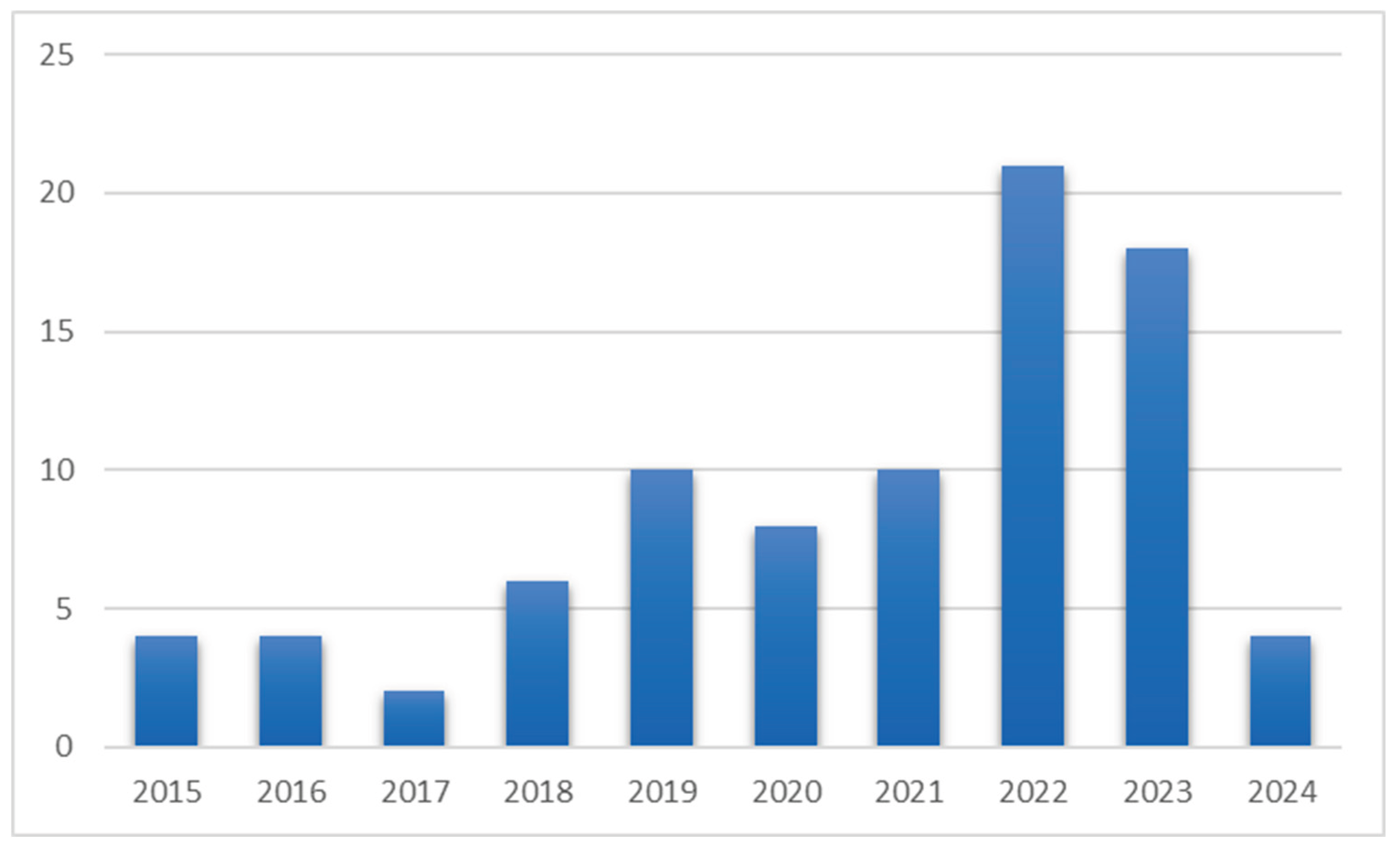

Table 5). In terms of publications trend, the distribution of articles shows a strong concentration in recent years: approximately two-thirds of the selected publications were published in 2022 and 2023, highlighting the increasing importance and relevance of the topics addressed (

Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Publication years of the selected papers.

Figure 2.

Publication years of the selected papers.

3. Results

This systematic literature review scrutinizes 107 articles published between 2015 and 2024. This section will first provide an overview of the literature based on the articles' meta-data, including an analysis of the topics, contexts, sectors and methods of analysis. Secondly, the research aims to establish a correlation between the structure of the Proposal for a Regulation and the specific areas of intervention identified by the European Commission, which include waste prevention, recyclability, recycled content, compostable packaging, and reusable packaging.

3.1. Overview of the Literature

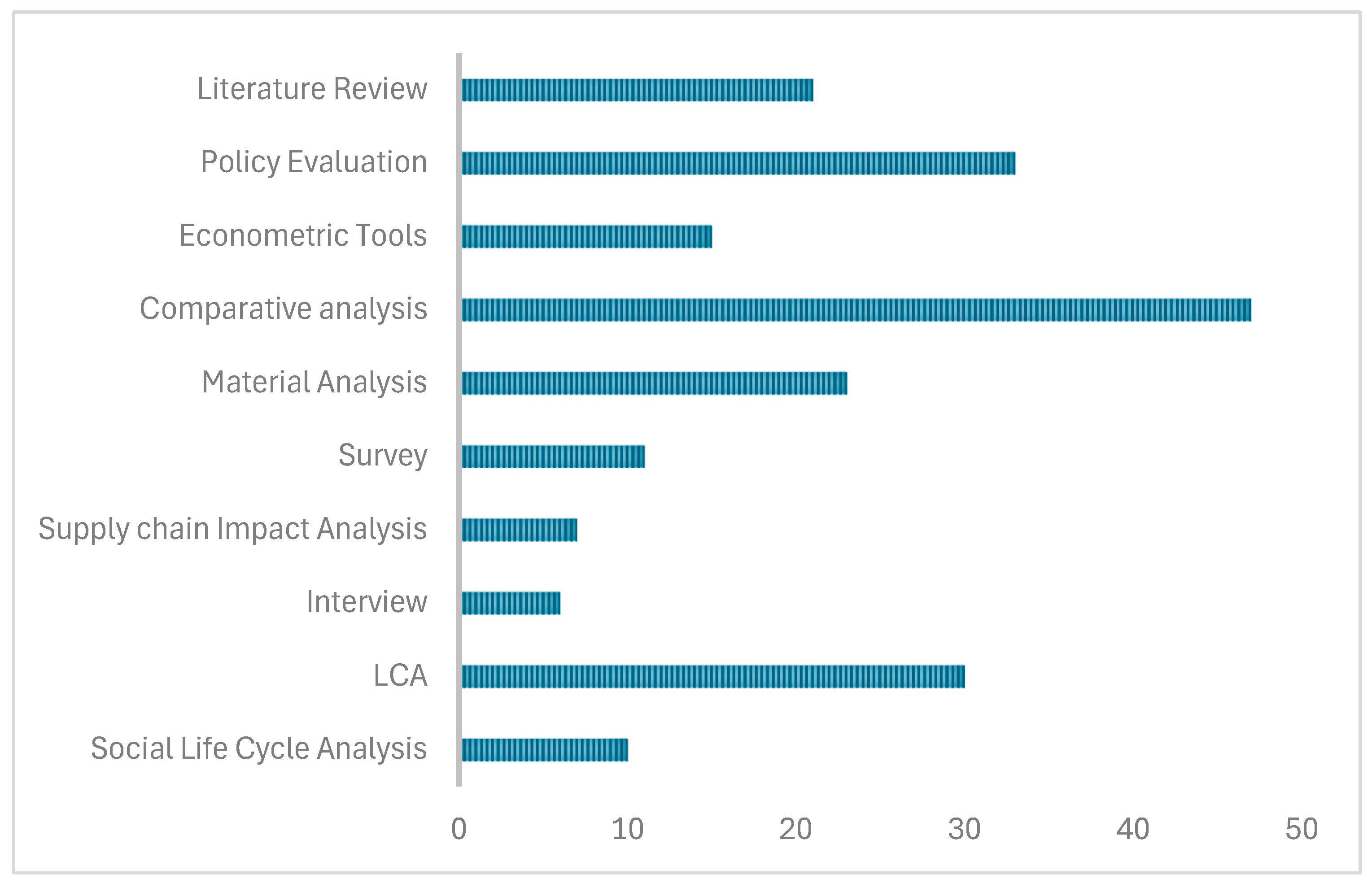

In order to address the research questions in a comprehensive manner, an analysis of the methodologies predominantly used by the authors in the selected documents was conducted. The results of the analysis are presented in a

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Predominant Methodological Approaches Utilized.

Figure 3.

Predominant Methodological Approaches Utilized.

The analysis of the data in

Figure 3 reveals a diverse range of methodologies employed in the study of packaging sustainability. Notably, Comparative Analysis is the most commonly used approach. As highlighted by Batista et al. (2024 and Hossain et al. (2022), this method facilitates the comparison of different scenarios, allowing for the identification of both the strengths and weaknesses of various interventions. For instance, it helps explain the limited growth in the biopolymer sector, which is largely attributed to a lack of consumer awareness. Policy Evaluation is the second most important area, underscoring the significance of regulatory policies in promoting sustainable packaging. For instance, Campbell-Johnston et al. (2021 analysis demonstrates how targeted regulatory incentives can guide manufacturers toward designs that prioritize reusability and recyclability. Following this, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a crucial tool for quantifying environmental impacts throughout the packaging lifecycle (Zimon et al., 2019; Pigosso et al., 2015). Ceschin & Gaziulusoy (2016) highlight that the LCA perspective provides a comprehensive overview - from production to disposal - and aids in developing eco-design strategies (Adams et al., 2016). Material analysis also plays a vital role, emphasizing the necessity of understanding material properties to enhance recycling, composting, or reuse processes (Kędzia et al., 2022; Ragaert et al., 2019). Additionally, conducting a literature review is important for contextualizing the current state of the field, as demonstrated by Silva & Pålsson (2022) and Ada et al. (2023), who point to the predominance of studies focused on the food sector and the need to expand research into other areas (Choudhary et al., 2019). In the field of economics, while Econometric Tools and Economic Analysis may have a more limited scope, they are crucial for assessing the costs and benefits of packaging innovations. For instance, Hage et al. (2016) and (Li et al. (2018) illustrate that some companies often prioritize optimizing existing systems, which can delay the adoption of more sustainable technologies. Meanwhile, Medina-Mijangos et al. (2021.) and Friederike Sträter & Rhein Katharina Friederike Sträter (2023) demonstrate how Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) policies can impact the long-term choices of producers and consumers. The Survey and the Social Life Cycle Analysis focus on analyzing consumer behavior within large samples (Matyi & Tamás, 2023; Sulami et al., 2023) and assessing socio-economic impacts at various stages of the product life cycle (Civancik-Uslu et al., 2019). From this perspective, adopting cassava starch-based packaging could offer benefits to small local businesses (Poltronieri et al., 2015; Casarejos et al., 2018). The Supply Chain Impact Analysis emphasizes how packaging decisions can affect the entire supply chain (Vegter et al., 2020; Almeida et al., 2022). It highlights that managing packaging sustainably requires a reorganization of logistics and production processes. Lastly, interviews are the least utilized tool; however, they offer valuable qualitative insights into the motivations and perceptions of consumers and stakeholders (Mansilla-Obando et al., 2024; Gustavo et al., 2018; Miao et al., 2023; Bryant, 2019). Overall, the analysis indicates that Comparative Analysis, Policy Evaluation, and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) are the most commonly employed methodologies. However, it is crucial to incorporate integrative methods—such as economic analysis, supply chain impact assessments, and social perspectives—to fully understand the complexity of a sustainable packaging system. This complexity arises from the close and dynamic interplay between environmental, economic, and social factors.

3.2. Intervention Areas

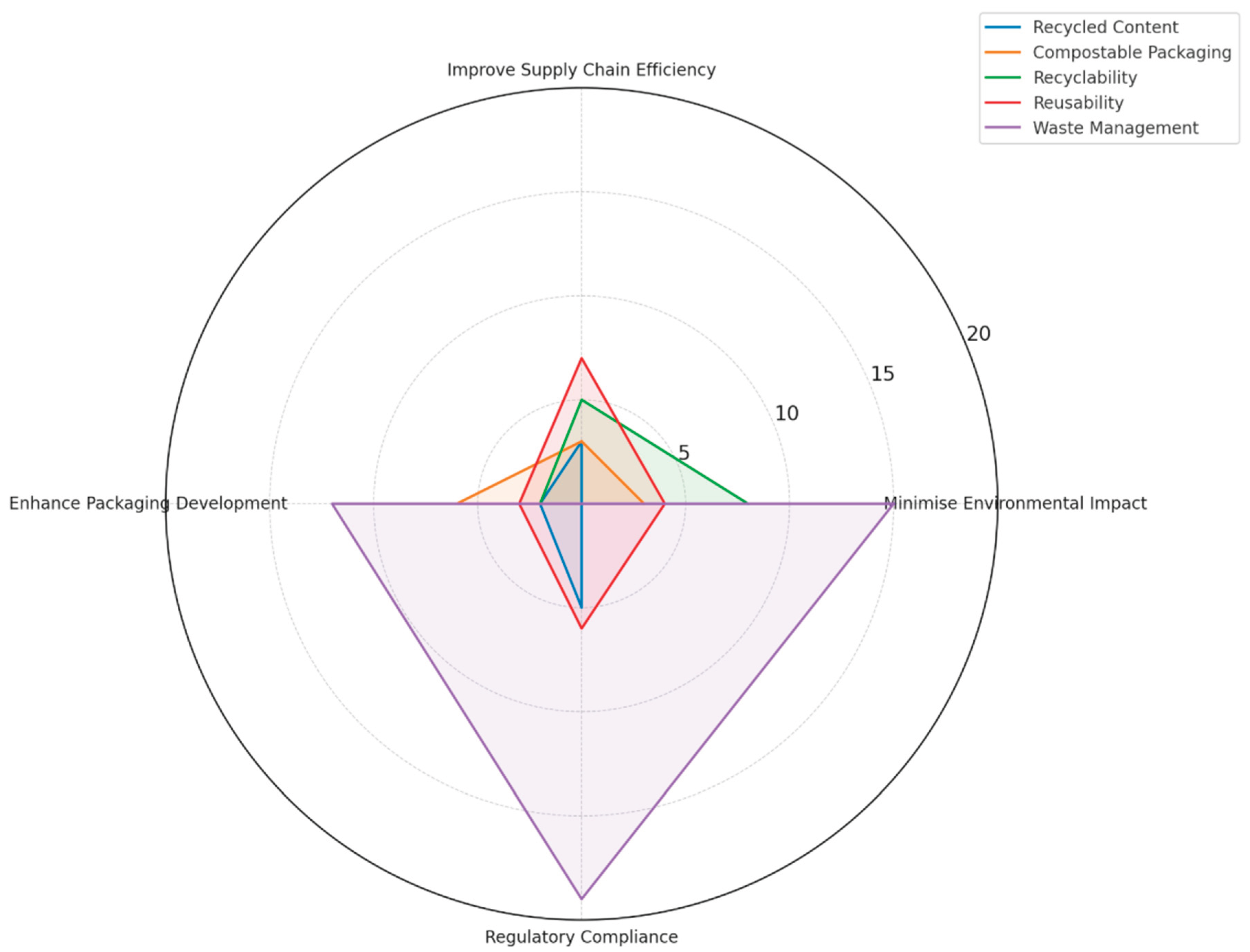

The Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation outlines requirements for the entire life cycle of packaging, from its composition to its disposal, to enable its placement on the market. This initiative is built on key pillars, including strategies to prevent and minimize packaging waste, promote the reduction of material use, and encourage reuse and recycling. Additionally, it supports innovation through eco-design and the development of compostable packaging (Commissione Europea, 2022). In the current study, various areas for improvement have been identified through the examination of different articles (Silva & Pålsson, 2022). These encompass the minimes of environmental impact, improve supply chain efficiency, enhance packaging development process and implication regulatory compliance (

Figure 4). The analysis of these aspects, along with the counting of publications related to these areas of interest, plays a critical role in determining the research direction and industry development in the field. The analysis of the scientific literature (

Figure 4) reveals a clear trend in research focus across five key intervention areas: Waste Prevention, Recyclability, Recycled Content, Compostable Packaging, and Reusable Packaging. The highest concentration of studies is found in Waste Prevention, followed by Reusable Packaging, Compostable Packaging and Recyclability. Recycled Content has received comparatively less attention.

3.2.1. Waste Prevention

Waste prevention is one of the most thoroughly researched areas of intervention, as shown in

Figure 4, which emphasizes its crucial role in reducing environmental impact. The literature primarily concentrates on strategies designed to minimize packaging waste, improve material efficiency, and implement Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) mechanisms (Tencati et al., 2016). These approaches aim to promote a more circular model for packaging (W. Li et al., 2019). The primary strategy for waste prevention focuses on reducing packaging during the design phase (Allacker et al., 2017). This ensures that materials are used efficiently without compromising product protection or quality (Arora et al., 2023). Studies show that excessive packaging can account for up to 65% of a product's total cost, making packaging optimization essential for lowering both economic and environmental impacts (Georgakoudis & Tipi, 2020). Research indicates that minimizing packaging can be achieved through methods such as lightweighting, material substitution, and modular design, which help reduce material consumption while maintaining functionality (Escursell et al., 2020). E-commerce is recognized as a significant contributor to the increase in packaging waste, as its growth leads to higher material consumption and waste generation (Jang et al., 2023). However, research demonstrates that retail can reduce CO₂ emissions by up to 84% compared to e-commerce, primarily due to its lower reliance on single-use shipping materials (Guarnieri et al., 2019). E-commerce is often more logistically efficient for long-distance deliveries, especially in rural areas, where consolidated shipments can help minimize transport emissions (Trivellas et al., 2020). Consumer perception and market trends play a crucial role in waste prevention. Excessive packaging can harm a brand’s image and negatively influence consumer attitudes, as more buyers now link sustainable packaging with corporate responsibility (Y. S. Chen et al., 2017). Research indicates that brands that focus on minimal, yet effective packaging designs build greater consumer trust and reduce the use of unnecessary materials (Monnot et al., 2019). Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) mechanisms are essential for promoting waste prevention by shifting the responsibility on producers (Kumar Pani & Pathak, 2021). This shift incentivizes manufacturers to design packaging that is easier to reuse, recycle, or minimize in volume (Walls, 2016.). By internalizing the environmental costs associated with waste disposal, EPR frameworks encourage manufacturers to invest in eco-design innovations, which help to reduce packaging waste at its source (Pouikli, 2027). However, even though EPR systems are widely implemented in Europe, packaging collection rates remain relatively low, especially in developing countries where waste management infrastructure is lacking (Compagnoni, 2022). A significant challenge in current EPR discussions is their primary focus on managing waste at the end of its lifecycle, rather than incorporating waste prevention at the design stage (Campbell-Johnston et al., 2021). Strengthening the connection between EPR policies and packaging design is vital for optimizing the circularity of materials (Eonore Maitre-Ekern, 2020). Future regulatory frameworks should prioritize design-for-reduction principles, ensuring that producers actively work to minimize material use before waste is generated (Diggle & Walker, 2020). Despite substantial research focused on waste prevention, there are still significant gaps, especially in optimizing supply chain efficiency and enhancing packaging development processes. The existing literature reveals a scarcity of studies that integrate logistics, supply chain optimization, and packaging waste reduction, even though these areas are interconnected and collectively impact sustainability goals.

3.2.2. Reusability

Reusability is one of the most thoroughly studied areas of intervention. This attention is due to its multiple benefits, as reusable packaging helps reduce environmental impact, improve supply chain efficiency, enhance packaging development, and ensure compliance with regulations. Research consistently shows that reusing packaging significantly reduces material consumption by extending the life cycle of packaging units (Muranko et al., 2021). In contrast to single-use options, reusable packaging systems lower the demand for virgin materials, which in turn reduces the extraction and processing of raw materials (Gatt & Refalo, 2022). This decrease contributes to less overall resource depletion and lower emissions (Allacker et al., 2017). Studies indicate that adopting reusable packaging, such as multi-purpose drums, can result in a 65% reduction in energy consumption, a 75% decrease in solid waste generation, and substantial reductions in greenhouse gas emissions compared to single-use packaging (Coelho, Corona, Ten Klooster, et al., 2020). The production of packaging consumes a significant amount of energy and is heavily dependent on fossil fuel-derived energy sources (Frischknecht et al., 2015). By reducing the frequency of production cycles, reusable packaging can lower overall energy consumption and effectively decrease carbon footprints across various industrial sectors (Pauer et al., 2019). However, the environmental benefits of reusable packaging systems largely depend on logistical factors, such as transport distances and fill rates, which affect the overall sustainability of reuse-based models (Friederike Sträter & Rhein Katharina Friederike Sträter, 2023). The successful implementation of reusable packaging systems relies on well-structured return logistics (Banaeian et al., 2015). This ensures efficient collection, cleaning, and redistribution of the packaging (Mansilla-Obando et al., 2024). Studies indicate that supply chains characterized by long geographical distances or low fill rates may sometimes prefer disposable systems due to the transportation impact associated with returning empty packaging units (Lu et al., 2022). Conversely, closed-loop supply chains and high-density distribution models have been found to enhance both the economic viability and environmental performance of reusable systems (Tan et al., 2023). From an economic perspective, reusable packaging requires an initial investment, as companies must develop reverse logistics infrastructure and cleaning processes (De Canio, 2023). However, once implemented at scale, reusable packaging can reduce long-term costs by decreasing dependency on raw materials, improving efficiency in storage and transportation, and lowering disposal expenses (Lin et al., 2023). Additionally, standardized reusable packaging systems, especially in B2B transactions, have demonstrated a significant reduction in supply chain inefficiencies while fostering greater collaboration among industry stakeholders (Ruggerio, 2021). Legislation plays a crucial role in promoting the market expansion of reusable packaging. The European Commission's impact assessment highlights the importance of policy interventions in encouraging a shift toward reusable solutions (Medina-Mijangos et al., 2021.). Key measures that have effectively supported this transition include banning single-use packaging for specific applications, implementing taxes on disposable packaging, and establishing mandatory deposit-return schemes. These initiatives have been instrumental in encouraging the adoption of reusable alternatives (Beswick-Parsons et al., 2023;Agnusdei et al., 2022). However, the success of such policies largely hinges on consumer participation and industry adaptation, which necessitates better alignment between regulation, innovation, and economic feasibility (Kazancoglu et al., 2023). The effectiveness of reusable packaging varies greatly based on the type of product, consumer behavior, and logistical challenges. Research has shown that sectors such as fruits, eggs, and bottled water have high potential for implementing reuse strategies, which require ambitious frameworks to be successful (Ellsworth-Krebs et al., 2022). Additionally, multi-use packaging systems have been shown to decrease the need for recycling and incineration, supporting a more circular approach to material management (Tan et al., 2023). Integrating eco-design principles into the development of reusable packaging is crucial. Standardized, modular, and durable designs can enhance usability, lower the risk of contamination, and improve consumer acceptance (Bishop et al., 2021). Additionally, incorporating digital tracking systems, like RFID technology, can optimize reverse logistics, leading to greater efficiency in the collection and redistribution of these packages (Friedrich et al., 2021). As shown in

Figure 4, reusable packaging is a well-researched topic with broad industry applicability and alignment with circular economy principles. Continued efforts are needed to refine regulatory frameworks, develop reuse infrastructure, and enhance technological innovations for effective implementation in global supply chains.

3.2.3. Compostable Packaging

The literature, emphasizes compostable packaging as an important area of research. While compostable packaging is consistent with the principles of a circular economy, the findings reveal several challenges in its practical implementation. These challenges primarily concern environmental impact, regulatory compliance, and consumer perception (Gastaldi et al., 2024). Compostable Packaging refers to a type of packaging that can be sustainably disposed of through composting (Reichert et al., 2020). This means that the packaging can be transformed into compost, a type of fertilizer, through a process in which organic materials are broken down by microorganisms under controlled conditions (Wojnowska-Baryła et al., 2020). Unlike conventional plastics, which can linger in the environment for decades, compostable materials are intended to decompose through microbial activity in controlled settings (Kędzia et al., 2022). The use of compostable packaging is closely related to bioplastics (Matyi & Tamás, 2023), with global production projected to reach 2.43 million tons in 2024, representing a 15% increase compared to 2019. This growth reflects a rising interest in alternative materials; however, both consumer awareness and industrial adaptation are still limited, which hinders widespread adoption (Kakadellis et al., 2022). While compostable packaging offers a promising solution for reducing environmental impact, there are several scientific concerns that need to be addressed. A significant issue is the risk of shifting environmental burdens (Sastre et al., 2022). Although compostable materials can help reduce plastic waste, their overall sustainability depends on factors such as land use, resource consumption, and their ability to biodegrade under real-world conditions (Kakadellis et al., 2022). One of the primary environmental concerns related to compostable packaging is land-use change. The production of bioplastics often requires converting agricultural land, which can lead to increased carbon emissions, disrupt ecosystems, and compete with food production (Gastaldi et al., 2024). Therefore, the life cycle assessment (LCA) of compostable materials must consider land-use emissions, as these can significantly affect the actual sustainability performance of bioplastics compared to conventional plastics (Reichert et al., 2020). Another challenge is the specific composting conditions required for biodegradation. Many compostable packaging materials need to be processed in industrial composting facilities, as they do not break down effectively in home composting systems or natural ecosystems (Casarejos et al., 2018). Without access to appropriate waste management infrastructure, these materials risk being mismanaged, contaminating recycling streams, or ending up in landfills, where their decomposition can release methane emissions, further exacerbating environmental issues (Kędzia et al., 2022;Jabarzare & Rasti-Barzoki, 2020). Regulatory frameworks are essential for the effective implementation of compostable packaging. The European Commission’s impact assessment highlights several key points: the establishment of clear biodegradability standards, the differentiation between home compostable and industrially compostable materials, and the development of mandatory labeling requirements (Regulation of the European Parlament and of the Council on Packaging and Packaging Waste, 2023). These measures are crucial to ensure that consumers can easily distinguish compostable packaging from conventional plastics. Despite these policy efforts, achieving compliance remains a challenge. Research indicates that many compostable materials often end up in landfills, where they do not decompose efficiently due to insufficient oxygen and microbial activity necessary for composting (Gastaldi et al., 2024). This underscores the need for integrated waste management policies that align composting regulations with consumer education and industrial processing capabilities (Kędzia et al., 2022).

3.2.4. Recyclability

The analysis of scientific literature emphasizes recyclability as a well-researched area of intervention. The focus of this research is largely on recyclability’s role in reducing environmental impact and ensuring compliance with regulations, in line with the objectives set by the European Commission. However, there remains a significant gap in understanding how to optimize supply chain efficiency, despite its potential to improve the overall effectiveness of recycling systems (Farooque et al., 2019). Recyclability is essential for reducing waste generation and promoting material reuse within a circular economy (Allacker et al., 2017). Research highlights that incorporating recyclability considerations during the design phase is crucial for facilitating effective recovery, sorting, and reprocessing (Zhu et al., 2022). Single-layer and monomaterial packaging materials are the easiest to recycle, unlike multilayer and composite materials, which often face technical difficulties in separation and reprocessing (Medina-Mijangos et al., 2021). The management of recyclable packaging at the end of its life significantly impacts its environmental footprint (Batista et al., 2019). Research highlights the importance of developing guidelines for material selection that prioritize highly recyclable polymers and fiber-based materials to minimize contamination in recycling streams (Silva & Pålsson, 2022). Additionally, the introduction of advanced recycling technologies, such as chemical recycling and enzymatic depolymerization, could enhance the recyclability of materials that are traditionally considered non-recyclable (Geueke et al., 2018). Despite the importance of recyclability in research, few studies address its connection to supply chain efficiency. The effectiveness of recycling systems relies not only on the design of materials but also on various logistical and operational factors that affect collection, sorting, and reprocessing (Hahladakis & Iacovidou, 2018). To maximize material recovery rates, efficient reverse logistics networks are crucial, yet research in this area is still limited. Optimizing supply chain coordination can greatly enhance recyclability outcomes by reducing contamination rates, improving material sorting accuracy, and lowering processing costs (Almeida et al., 2022). In the realm of packaging development, Gardas et al., (2019) recommend further exploration of emerging technologies, such as additive manufacturing and 3D printing, to conceive innovative packaging solutions. These technologies could improve traceability and quality control within recycling systems (Hage et al., 2016). Moreover, consumer behavior significantly impacts recyclability outcomes (Antonopoulos et al., 2021). Research shows that companies should invest in awareness campaigns and incentive programs to encourage consumers to properly separate and dispose of recyclable materials (Panchal et al., 2021). Recyclability is a crucial area of intervention in circular economy research. However, future advancements will necessitate a more comprehensive approach that includes supply chain optimization, material innovation, and consumer participation to maximize the environmental and economic advantages of recyclable packaging.

3.2.5. Recycled Content

The analysis of scientific literature reveals that the use of recycled content is an important area of focus within circular economy frameworks, yet it is less researched compared to other packaging strategies like waste prevention, recyclability, and reusability. Most of the attention in this area is centered around regulatory compliance, as policy frameworks set mandatory targets for incorporating recycled materials into packaging production (Firoozi Nejad et al., 2021). However, despite these regulatory incentives and a growing environmental consciousness, the industrial adoption of recycled content remains limited due to technical, economic, and consumer-related challenges (Ibrahim et al., 2022). Regulations play a crucial role in promoting the use of recycled materials, especially through policies that require a minimum percentage of recycled content in packaging. According to Moyaert (2022), certification schemes and supply chain tracking mechanisms are essential for ensuring transparency, compliance, and the integrity of recycled materials. Traceability systems are particularly crucial for hazardous material streams, where regulatory compliance and material safety must be verified throughout the recycling process (Gianvincenzi et al., 2024). The adoption of traceability systems, such as blockchain-based certification, can enhance the verification of recycled content and help prevent false claims about sustainability (Radusin et al., 2020). However, despite regulatory frameworks promoting the use of recycled materials, challenges continue to hinder the achievement of consistent and high-quality recycled content in packaging (Seier et al., 2023). Research shows that many industries are still reluctant to increase their dependence on recycled polymers due to uncertainties regarding supply, quality inconsistencies, and variations in cost (Ragaert et al., 2019;Vegter et al., 2020;Friederike Sträter & Rhein Katharina Friederike Sträter, 2023). A major barrier to using recycled content is the mechanical performance limitations of recycled polymers. Compared to virgin plastics, recycled materials often have lower strength, durability, and processability, limiting their use in high-performance packaging (Radusin et al., 2020). The degradation of polymer chains during recycling reduces their physical properties, often requiring blending with virgin materials to meet industrial standards (Zimon et al., n.d.). Contamination is another significant concern in recycled material streams. Non-recyclable residues and varied material compositions can create quality inconsistencies, making it difficult for manufacturers to ensure uniformity in recycled packaging products (Moyaert et al., 2022). In addition, consumer perception plays a crucial role in the market viability of packaging containing recycled materials (Ibrahim et al., 2022). Research suggests that negative associations with color, texture, and odor variations in recycled packaging can influence purchasing decisions (Kazulytė & Kruopienė, 2018). Companies must therefore prioritize design and branding strategies to enhance the aesthetic and functional appeal of recycled packaging, ensuring that it meets consumer expectations for quality and sustainability (Radusin et al., 2020). Research on recycled content is still somewhat limited compared to other areas of focus. However, the importance of incorporating recycled materials into packaging production is growing, driven by regulatory requirements and the push for sustainability. Advancing the technical, economic, and consumer-related aspects of recycled content is crucial for increasing its adoption and ensuring that packaging systems align with the goals of a circular economy.

3.3. Methodological Integration Across PPWR Intervention Areas

Table 6 shows a comprehensive analysis of the methodologies employed in the studies reviewed in the systematic literature review. It relates these methods to the five areas of intervention identified by the European Commission in the packaging sector: Waste Prevention, Recyclability, Recycled Content, Compostable Packaging, and Reusable Packaging. The table reveals that the analyzed articles do not rely on a single methodology; instead, they often utilize multiple approaches to provide a more complete and multidimensional perspective on packaging sustainability. This choice of methodology is crucial for addressing the complex challenges of the circular economy by integrating environmental, economic, regulatory, and social analyses.

The most commonly used methodologies by the authors include Life Cycle Analysis (LCA), Comparative Analysis, Policy Evaluation, and Material Analysis (

Figure 3). Among these, LCA is particularly prominent across all intervention areas, highlighting its essential role in evaluating the environmental impacts and shaping sustainability strategies (Ceschin & Gaziulusoy, 2016;Huang & Akbari, 2024). Since packaging sustainability includes environmental, economic, and regulatory aspects, the use of LCA reflects a strong commitment to data-driven decision-making. Comparative Analysis is frequently employed in Reusability, Recyclability, and Compostable Packaging, underscoring its value in benchmarking the environmental and economic performance of various packaging solutions (Moyaert et al., 2022). Policy Evaluation is prominently used in Waste Prevention and Reusability, focusing on the regulatory aspects of sustainable packaging, including Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) mechanisms (Pouikli, 2017). Material Analysis is critical in the contexts of Recyclability and Compostable Packaging, as it provides essential technical validation of material properties, biodegradability, and recyclability potential (Hahladakis & Iacovidou, 2018). Despite their potential to offer valuable insights into logistics, financial feasibility, and consumer acceptance, methodologies such as Supply Chain Impact Analysis, Social Life Cycle Analysis, and Economic Tools are currently underutilized. Future research should prioritize these methodologies to address significant gaps in the assessment of sustainable packaging.

4. Discussions

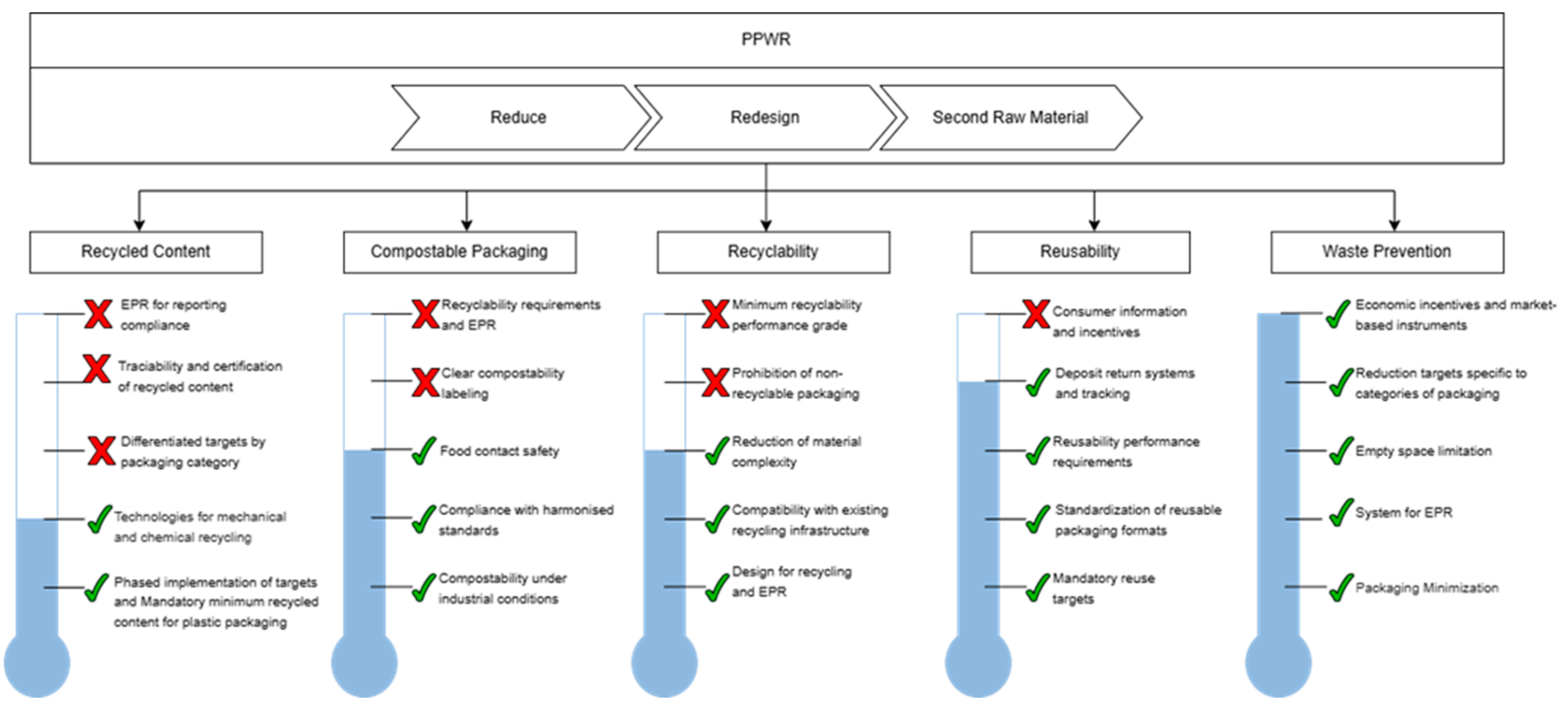

The distribution of research publications across the five intervention areas defined by the PPWR, Waste Prevention, Reusability, Recyclability, Compostable Packaging, and Recycled Content, shows varying levels of scientific maturity and alignment with regulatory goals. The PPWR introduces a comprehensive framework designed to reduce packaging waste through three strategic approaches: reduction, redesign, and the valorization of secondary raw materials. In this context,

Figure 5 illustrates how current academic literature addresses the specific regulatory requirements for each intervention area, employing a "circularity thermometer" approach to depict the relative maturity and extent of research coverage.

Waste prevention is a key area, particularly regarding the challenges of packaging waste. Literature reviews are frequently employed to synthesize various findings and assess the current state of art (Adams et al., 2016;Ruggerio, 2021;Sastre et al., 2022;Meherishi et al., 2019;Silva & Pålsson, 2022). Comparative analysis is also commonly used to evaluate prevention strategies across different packaging formats and regulatory contexts (Boesen et al., 2019;Herrera et al., 2022;Mansilla-Obando et al., 2024). Many of these studies emphasize the environmental benefits of material reduction, lightweighting, and design optimization, usually supported by LCA (Frischknecht et al., 2015;Niero, 2023). EPR is consistently identified as a vital policy mechanism for waste prevention, with numerous studies assessing its effectiveness and scalability through policy evaluation (Tencati et al., 2016;Eonore Maitre-Ekern, 2020). While minimizing environmental impact remains the primary focus of research, other aspects such as packaging development and regulatory compliance have received comparatively less attention (Banaeian et al., 2015;L. H. Chen et al., 2020Bryant, 2019;Ruggerio, 2021; Lifset et al., 2023). The alignment between literature and the regulatory priorities outlined in the PPWR is particularly strong in this area. The requirements defined by the PPWR, such as packaging minimization, the establishment of EPR, systems, limitations on empty space in packaging, reduction targets specific to product categories and the introduction of economic incentives and market-based instruments, are well-supported by existing research. For instance, the principles of Design for minimization are widely discussed for their ability to reduce material use and life cycle impacts (Allacker et al., 2017). EPR frameworks are frequently identified as key drivers of innovation in eco-design (Kumar Pani & Pathak, 2021). Additionally, studies examine the role of economic instruments like modulated fees and material taxes in promoting sustainable packaging decisions (Tencati et al., 2016;Diggle & Walker, 2020). This convergence indicates that waste prevention is the most advanced and policy aligned area among the five intervention domains of the PPWR (

Figure 5). The area of reusability has evolved into a complex area of research, emphasizing its increasing importance within the circular economy and the PPWR. Central to this field is the interaction between design, consumer behavior, and policy, which influences the variety of methodologies employed. Policy evaluation is particularly significant, as it assesses the effectiveness of reuse-related regulatory instruments, such as mandatory reuse targets and deposit-return systems, and their potential for harmonized implementation across Member States (Steinhorst & Beyerl, 2021;Beswick-Parsons et al., 2023). Survey-based methodologies are also commonly used to analyze consumer acceptance, return behaviors, and the effectiveness of reuse schemes in different market contexts (Herrmann et al., 2022;Kazancoglu et al., 2023). From a regulatory standpoint, current academic research aligns with several key requirements of the PPWR concerning reusability. In particular, studies offer valuable insights into mandatory reuse targets, the standardization of reusable packaging formats, reusability performance requirements, and the design and implementation of deposit-return systems and tracking technologies. Muranko et al. (2021) and Coelho, Corona, ten Klooster, et al. (2020) highlights the environmental and economic advantages of standardized, durable packaging formats that extend product lifecycles. Similarly, the integration of RFID and IoT-based systems for tracking reuse cycles is widely discussed as a means to enhance return logistics and supply chain transparency (Friedrich et al., 2021). However, a critical area that remains underexplored is consumer information and incentives. Although some studies address behavioural factors, such as perceived convenience, hygiene concerns, and willingness to engage in reuse schemes, there is a lack of detailed analysis on how targeted communication strategies or economic incentives can encourage consumer participation (Tan et al., 2023;Ellsworth-Krebs et al., 2022). This gap is particularly significant, as the success of reusable packaging systems, especially in B2C applications, largely depends on consumer participation and behavioural change (Bishop et al., 2021). Reusability has emerged as a well-established area of research that meets most regulatory requirements outlined in the PPWR. Compostable packaging is receiving increased attention in academic research for its potential to reduce environmental impact and promote sustainable packaging design. Common methodologies in this field include LCA, Material Analysis, and Comparative Analysis, which evaluate the biodegradation performance, environmental effects, and suitability of compostable materials (Reichert et al., 2020;Kędzia et al., 2022). The literature aligns with several requirements of the PPWR, focusing on the compostability of materials under industrial conditions and compliance with European safety standards (Gastaldi et al., 2024). These aspects are addressed through biodegradability testing and risk analysis. However, there is a gap regarding clear compostability labeling, which is crucial for reducing consumer confusion (Casarejos et al., 2018). While some studies mention consumer misconceptions about biodegradable versus compostable materials, there is limited research on effective labeling strategies or their impacts. Additionally, recyclability requirements for compostable materials and their integration into EPR schemes are rarely discussed, which is essential for cohesive waste management and policy (Regulation of the European Parlament and of the Council on Packaging and Packaging Waste, 2025). Further, the economic feasibility and supply chain implications of compostable packaging are often underexplored. Challenges like limited industrial composting infrastructure and contamination risks are acknowledged but not analyzed in-depth (Jabarzare & Rasti-Barzoki, 2020). Recyclability is a well-studied area in the literature, especially from an environmental point of view. The most common methods used are LCA, comparative analysis, and policy evaluation. These approaches help assess how materials can be recycled, their impact on the environment and how policies support recycling. Many studies focus on designing packaging to be easily recyclable, reducing the complexity of materials and ensuring that packaging is compatible with current recycling infrastructure (Allacker et al., 2017;Silva & Pålsson, 2022). These elements are well aligned with the requirements of the PPWR. The literature also includes research on EPR, which encourages companies to design packaging that is easier to recycle and to take responsibility for its end-of-life (Kumar Pani & Pathak, 2021). This again supports the goals of the PPWR, especially in pushing producers to improve packaging design and recycling outcomes. Some important areas related to recyclability are not adequately addressed in current research. For instance, while the regulation includes a ban on non-recyclable packaging and new requirements for a minimum recyclability performance grade, these topics are not extensively explored in the literature. Few studies examine how effectively packaging is recycled in real-life systems or how the sorting and collection processes influence recyclability (Farooque et al., 2019;Medina-Mijangos et al., n.d.). Additionally, although the design of packaging has been well-studied, there is a lack of focus on recycling logistics, including collection systems, sorting efficiency, and the market for secondary raw materials. These factors are crucial for effective recycling but remain underexplored (Almeida et al., 2022;Antonopoulos et al., 2021). Recyclability aligns with several key requirements of the PPWR , such as designing for recycling, simplifying materials, and ensuring compatibility with recycling infrastructures. However, it pays less attention to the regulations concerning the ban on non-recyclable packaging and minimum performance standards, which are expected to become increasingly important in the future. Further research is needed in these areas to fully support the implementation of the PPWR. Although recycled content is important in the context of the circular economy, it remains one of the least explored areas in academic research. Most studies focus on material analysis, comparative analysis and policy evaluations to compare recycled materials with virgin materials, assess economic impacts, and examine compliance with regulations (Radusin et al., 2020Moyaert et al., 2022). These studies primarily address the mandatory minimum recycled content targets for plastic packaging and the development of mechanical and chemical recycling technologies, which align with several key requirements of the PPWR. However, several important regulatory aspects are still insufficiently covered in the literature. For example, the differentiated targets by packaging category, the traceability and certification of recycled content, and the EPR mechanisms for compliance reporting are rarely discussed in detail. These elements are essential for ensuring transparency and preventing greenwashing (Ibrahim et al., 2022;Seier et al., 2023). Moreover, technical challenges such as contamination, polymer degradation, and inconsistent quality in recycled materials are acknowledged but not sufficiently analyzed. These issues directly affect the reliability and scalability of using recycled content in packaging, particularly when high-performance or food contact standards are required (Ragaert et al., 2017;Kazulytė & Kruopienė, 2018). Additionally, consumer perception can act as a barrier, as concerns about the safety and functionality of recycled packaging may reduce acceptance (Ibrahim et al., 2022). While the literature addresses some areas aligned with the PPWR, many critical regulatory dimensions remain under-researched. Compared to other intervention areas, recycled content is the least aligned with the PPWR's requirements.

5. Conclusion

The present research contributes by analyzing the relationship between the European Commission's Packaging and Packaging Waste Proposal and its intervention areas, exploring the potential of packaging and eco-design in reducing environmental impact. The research focused on how these areas align with the European Commission’s impact assessment, particularly concerning their role in reducing environmental impact, optimizing supply chain efficiency, enhancing the packaging development process, and ensuring compliance with existing regulations. Through an extensive literature review of studies published between 2015 and 2024, this research provided a comprehensive overview of trends, methodological approaches, and critical gaps in the field. The results, summarized in the “Circularity Thermometer,” indicate that waste prevention and reusability are the most developed areas and align well with PPWR requirements. These areas have emerged as the most developed areas in academic research. These fields align well with the PPWR, particularly regarding packaging minimization, standardization, and deposit-return schemes. Research in these areas provides a strong foundation for supporting upstream strategies at the top of the waste hierarchy. However, the limited focus on behavioral incentives for reusability highlights a critical implementation barrier that needs to be addressed through both academic inquiry and policy design. On the other hand, recyclability and compostable packaging are only partially covered in the literature. While many studies explore environmental performance and design for recycling, there is a notable lack of focus on key PPWR provisions such as the prohibition of non-recyclable formats, minimum recyclability performance grades, and comprehensive EPR integration. In the case of compostable packaging, most research prioritizes biodegradability but overlooks challenges like sorting infrastructure, compostability labeling, and regulatory compliance mechanisms. This gap in alignment could undermine the regulation’s effectiveness in finding viable solutions. Recycled content is the least researched area, despite its strategic importance within the PPWR. Although some studies look into mechanical and chemical recycling technologies, critical requirements such as differentiated targets, traceability, certification and EPR for reporting compliance are still underexplored. This lack of research poses a risk to progress toward establishing a robust market for secondary raw materials, which is essential for supporting a circular Single Market. A key transversal finding is the EPR across the intervention areas. While EPR is widely discussed in the context of waste prevention and recyclability, it is scarcely addressed in relation to compostable packaging and recycled content. This limits the understanding of how EPR can drive innovation, assign financial responsibility, and enforce compliance across the packaging life cycle. Stronger engagement with EPR in research could help design more effective systems that foster eco-design, traceability, and the integration of post-consumer materials into production. EPR is a crucial mechanism for effectively implementing all five intervention areas related to packaging waste. However, its treatment in academic research is often fragmented. To address these challenges and contribute to the overarching goals of the PPWR, which include preventing packaging waste, reducing environmental issues and promoting circularity, policy frameworks need to support the harmonization of EPR systems. Additionally, they should encourage the development of interoperable digital tools, such as the Digital Product Passport, and facilitate the efficient circulation of secondary raw materials. This study offers a comprehensive review, however, it has some limitations. The literature selection was limited to 107 articles published between 2015 and 2024, which may have excluded relevant research from outside this timeframe or studies published in non-English sources. Additionally, the review primarily relies on secondary data and does not include any empirical research or primary data collection. While the study aims to provide a broad perspective on packaging sustainability, it may overlook specific sector challenges, especially in highly specialized industries such as pharmaceuticals, food, and electronics, which warrant further investigation. Furthermore, the results are largely influenced by European policies and regulatory frameworks, potentially failing to capture global trends in packaging sustainability. To address the research gaps identified in this paper, future studies should adopt a more integrated and systemic approach to packaging sustainability. This approach should extend beyond environmental assessments to encompass operational, economic and behavioral dimensions. Specifically, supply chain management requires closer attention, particularly in areas such as reverse logistics, the development of efficient collection and sorting systems, and the integration of closed-loop models. These models facilitate the consistent use of secondary raw materials across the EU. Research should also examine the economic viability of sustainable packaging options, including the cost-effectiveness of reusable systems and the market integration of recycled content. Evaluating financial incentives, taxation schemes and other market-based instruments could provide valuable insights into how policy mechanisms can accelerate the shift toward circular packaging solutions. In this context, the role of EPR is crucial. Future studies should go beyond descriptive policy overviews and critically assess the effectiveness of EPR schemes in driving innovation, supporting eco-design, and fostering investment in recycling infrastructure and traceability systems. Technological innovation remains a key driver of progress. More in-depth research is necessary on emerging recycling technologies, such as chemical recycling, as well as on advanced bio-based and compostable materials that can meet both performance and regulatory requirements. Studies should explore how factors such as labeling, transparency and incentive schemes influence consumer preferences and return behavior, particularly regarding reusable and compostable packaging formats. Future research should support policy and practice: a multidisciplinary approach that connects environmental science with policy evaluation, industrial engineering, and behavioral economics will be essential to achieve circular economy goals.

References

- Ada, E. , Kazancoglu, Y., Lafcı, Ç., Ekren, B. Y., & Çimitay Çelik, C. Identifying the Drivers of Circular Food Packaging: A Comprehensive Review for the Current State of the Food Supply Chain to Be Sustainable and Circular. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R. , Jeanrenaud, S., Bessant, J., Denyer, D., & Overy, P. Sustainability-oriented Innovation: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Management Reviews 2016, 18, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afif, K. , Rebolledo, C., & Roy, J. (2021). Evaluating the effectiveness of the weight-based packaging tax on the reduction at source of product packaging: The case of food manufacturers and retailers. [CrossRef]

- Agnusdei, G. P. , Gnoni, M. G., & Sgarbossa, F. (2022). Are deposit-refund systems effective in managing glass packaging? State of the art and future directions in Europe. Science of the Total Environment, 2022; 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. , Sarwo Utomo, D., Dadhich, P., & Greening, P. Packaging design, fill rate and road freight decarbonisation: A literature review and a future research agenda. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain 2022, 4, 100066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allacker, K. , Mathieux, F., Pennington, D., & Pant, R. The search for an appropriate end-of-life formula for the purpose of the European Commission Environmental Footprint initiative. International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2017, 22, 1441–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C. , Loubet, P., da Costa, T. P., Quinteiro, P., Laso, J., Baptista de Sousa, D., Cooney, R., Mellett, S., Sonnemann, G., Rodríguez, C. J., Rowan, N., Clifford, E., Ruiz-Salmón, I., Margallo, M., Aldaco, R., Nunes, M. L., Dias, A. C., & Marques, A. Packaging environmental impact on seafood supply chains: A review of life cycle assessment studies. Journal of Industrial Ecology 2022, 26, 1961–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulos, I. , Faraca, G., & Tonini, D. Recycling of post-consumer plastic packaging waste in the EU: Recovery rates, material flows, and barriers. Waste Management 2021, 126, 694–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, T. , Sarvani, ·, Chirla, R., Singla, N., Lovleen Gupta, ·, Gupta, L., & In, L. A. Product Packaging by E-commerce Platforms: Impact of COVID-19 and Proposal for Circular Model to Reduce the Demand of Virgin Packaging-commerce packaging questionnaire · Carbon footprint assessment · Packaging reuse model · Sustainable E-commerce · Packaging waste minimisation. Circular Economy and Sustainability 2023, 3, 1255–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaeian, N. , Mobli, H., Nielsen, I. E., & Omid, M. Criteria definition and approaches in green supplier selection – a case study for raw material and packaging of food industry. Production & Manufacturing Research 2015, 3, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, L. , Gong, Y., Pereira, S., Jia, F., & Bittar, A. (n.d.). Circular Supply Chains in Emerging Economies-A comparative study of packaging recovery ecosystems in China and Brazil.

- Beswick-Parsons, R. , Jackson, P., & Evans, D. M. Understanding national variations in reusable packaging: Commercial drivers, regulatory factors, and provisioning systems. Geoforum 2023, 145, 103844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, G. , Styles, D., & Lens, P. N. L. (2021). Environmental performance comparison of bioplastics and petrochemical plastics: A review of life cycle assessment (LCA) methodological decisions. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2021; 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesen, S. , Bey, N., & Niero, M. Environmental sustainability of liquid food packaging: Is there a gap between Danish consumers’ perception and learnings from life cycle assessment? Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 210, 1193–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C. G. , & Corsini, L. A literature review and analytical framework of the sustainability of reusable packaging. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2023, 37, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C. J. We Can’t Keep Meating Like This: Attitudes towards Vegetarian and Vegan Diets in the United Kingdom. Sustainability 2019, Vol. 11, Page 6844 2019, 11, 6844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Johnston, K. , de Munck, M., Vermeulen, W. J. V., & Backes, C. Future perspectives on the role of extended producer responsibility within a circular economy: A Delphi study using the case of the Netherlands. Business Strategy and the Environment 2021, 30, 4054–4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarejos, F. , Bastos, C. R., Rufin, C., & Frota, M. N. (2018). Rethinking packaging production and consumption vis-a-vis circular economy: A case study of compostable cassava starch-based material. [CrossRef]

- Ceschin, F. , & Gaziulusoy, I. Evolution of design for sustainability: From product design to design for system innovations and transitions. Design Studies 2016, 47, 118–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. H. , Hung, P., & Ma, H. wen. Integrating circular business models and development tools in the circular economy transition process: A firm-level framework. Business Strategy and the Environment 2020, 29, 1887–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. S. , Hung, S. T., Wang, T. Y., Huang, A. F., & Liao, Y. W. (2017). The influence of excessive product packaging on green brand attachment: The mediation roles of green brand attitude and green brand image. Sustainability (Switzerland), 2017; 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S. , Nayak, R., Dora, M., Mishra, N., & Ghadge, A. (2019). An integrated lean and green approach for improving sustainability performance: a case study of a packaging manufacturing SME in the U.K. Production Planning and Control, 2019; 30, 5–6, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civancik-Uslu, D. , Puig, R., Voigt, S., Walter, D., & Fullana-I-Palmer, P. (2019). Improving the production chain with LCA and eco-design: application to cosmetic packaging. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, P. M. , Corona, B., Ten Klooster, R., & Worrell, E. (2020). Sustainability of reusable packaging-Current situation and trends. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, P. M. , Corona, B., ten Klooster, R., & Worrell, E. Sustainability of reusable packaging–Current situation and trends. Resources, Conservation & Recycling: X 2020, 6, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagnoni, M. Is Extended Producer Responsibility living up to expectations? A systematic literature review focusing on electronic waste. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 367, 133101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Canio, F. Consumer willingness to pay more for pro-environmental packages: The moderating role of familiarity ☆. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 339, 117828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diggle, A. , & Walker, T. R. (2020). Implementation of harmonized Extended Producer Responsibility strategies to incentivize recovery of single-use plastic packaging waste in Canada. [CrossRef]

- Ellsworth-Krebs, K. , Rampen, C., Rogers, E., Dudley, L., & Wishart, L. Sustainable Production and Consumption Circular economy infrastructure: Why we need track and trace for reusable packaging. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2022, 29, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eonore Maitre-Ekern, E. (2020). Re-thinking producer responsibility for a sustainable circular economy from extended producer responsibility to pre-market producer responsibility. [CrossRef]

- Escursell, S. , Llorach-Massana, P., & Roncero, M. B. (2020). Sustainability in e-commerce packaging: A review. [CrossRef]

- Farooque, M. , Zhang, A., Thürer, M., Qu, T., & Huisingh, D. Circular supply chain management: A definition and structured literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 228, 882–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozi Nejad, B. , Smyth, B., Bolaji, I., Mehta, N., Billham, M., & Cunningham, E. (2021). Carbon and energy footprints of high-value food trays and lidding films made of common bio-based and conventional packaging materials. [CrossRef]

- Friederike Sträter, K. , & Rhein Katharina Friederike Sträter, S. P. (2023). Plastic packaging: Are German retailers on the way towards a circular economy? Companies’ strategies and perspectives on consumers. [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, K. , Fritz, T., Koinig, G., Pomberger, R., & Vollprecht, D. (2021). Assessment of technological developments in data analytics for sensor-based and robot sorting plants based on maturity levels to improve austrian waste sorting plants. Sustainability (Switzerland), 2021; 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frischknecht, R. , Wyss, F., Büsser Knöpfel, S., Lützkendorf, T., & Balouktsi, M. Cumulative energy demand in LCA: the energy harvested approach. International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2015, 20, 957–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardas, B. B. , Raut, R. D., & Narkhede, B. (2019). Identifying critical success factors to facilitate reusable plastic packaging towards sustainable supply chain management Sustainability Multi-criteria decision-making Lean production Interpretive structural modeling Total interpretive structural modeling. [CrossRef]

- Gastaldi, E. , Buendia, F., Greuet, P., Benbrahim Bouchou, Z., Benihya, A., Cesar, G., & Domenek, S. Degradation and environmental assessment of compostable packaging mixed with biowaste in full-scale industrial composting conditions. Bioresource Technology 2024, 400, 130670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatt, I. J. , & Refalo, P. (2022). Reusability and recyclability of plastic cosmetic packaging: A life cycle assessment. [CrossRef]

- Georgakoudis, E. D. , & Tipi, N. S. (2020). International Journal of Sustainable Engineering ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tsue20 An investigation into the issue of overpackaging-examining the case of paper packaging An investigation into the issue of overpackaging-examining the case of paper packaging. [CrossRef]

- Geueke, B. , Groh, K., & Muncke, J. Food packaging in the circular economy: Overview of chemical safety aspects for commonly used materials. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 193, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianvincenzi, M. , Mosconi, E. M., Marconi, M., & Tola, F. Battery Waste Management in Europe: Black Mass Hazardousness and Recycling Strategies in the Light of an Evolving Competitive Regulation. Recycling 2024, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnieri, P. , Cerqueira-Streit, J. A., & Batista, L. C. (2019). Reverse logistics and the sectoral agreement of packaging industry in Brazil towards a transition to circular economy. [CrossRef]

- Gustavo, J. U. , Pereira, G. M., Bond, A. J., Viegas, C. V., & Borchardt, M. Drivers, opportunities and barriers for a retailer in the pursuit of more sustainable packaging redesign. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 187, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, O. , Sandberg, · Krister, Söderholm, P., & Berglund, · Christer. The regional heterogeneity of household recycling: a spatial-econometric analysis of Swedish plastic packing waste. Letters in Spatial and Resource Sciences 2016, 11, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahladakis, J. N. , & Iacovidou, E. Closing the loop on plastic packaging materials: What is quality and how does it affect their circularity? Science of The Total Environment 2018, 630, 1394–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, A. , Acosta-Dacal, A., Pérez Luzardo, O., Martínez, I., Rapp, J., Reinold, S., Montesdeoca-Esponda, S., Montero, D., & Gómez, M. Bioaccumulation of additives and chemical contaminants from environmental microplastics in European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Science of The Total Environment 2022, 822, 153396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, C. , Rhein, S., & Sträter, K. F. Consumers’ sustainability-related perception of and willingness-to-pay for food packaging alternatives. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2022, 181, 106219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, R. , Islam, T., Ghose, A., & Sahajwalla, V. Full circle: Challenges and prospects for plastic waste management in Australia to achieve circular economy. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 368, 133127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. , & Akbari, F. Integrated sustainability perspective and spillover effects of social, environment and economic pillars: A case study using SEY model. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 2024, 96, 102077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I. D. , Hamam, Y., Sadiku, E. R., Ndambuki, J. M., Kupolati, W. K., Jamiru, T., Eze, A. A., & Snyman, J. (2022). Need for Sustainable Packaging: An Overview. Polymers, 14. [CrossRef]

- Ilg, P. How to foster green product innovation in an inert sector. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 2019, 4, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IT IT COMMISSIONE EUROPEA. (n.d.).

- Jabarzare, N. , & Rasti-Barzoki, M. A game theoretic approach for pricing and determining quality level through coordination contracts in a dual-channel supply chain including manufacturer and packaging company. International Journal of Production Economics 2020, 221, 107480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y. , Kim, K. N., & Woo, J. Post-consumer plastic packaging waste from online food delivery services in South Korea. Waste Management 2023, 156, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joltreau, E. Extended Producer Responsibility, Packaging Waste Reduction and Eco-design. Environmental and Resource Economics 2022, 83, 527–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakadellis, S. , Lee, P. H., & Harris, Z. M. Two Birds with One Stone: Bioplastics and Food Waste Anaerobic Co-Digestion. Environments - MDPI 2022, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazancoglu, Y. , Ada, E., Ozbiltekin-Pala, M., As¸kın, R., & Uzel, A. In the nexus of sustainability, circular economy and food industry: Circular food package design. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 415, 137778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazulytė, I. , & Kruopienė, J. Production of packaging from recycled materials: Challenges related to hazardous substances. Environmental Research, Engineering and Management 2018, 74, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kędzia, G. , Ocicka, B., Pluta-Zaremba, A., Raźniewska, M., Turek, J., & Wieteska-Rosiak, B. Social Innovations for Improving Compostable Packaging Waste Management in CE: A Multi-Solution Perspective. Energies 2022, 15, 9119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Pani, S. , & Pathak, A. A. Managing plastic packaging waste in emerging economies: The case of EPR in India. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 288, 112405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D. , Zhao, Y., Zhang, L., Chen, X., & Cao, C. Impact of quality management on green innovation. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 170, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. , Wang, J., Chen, R., Xi, Y., Liu, S. Q., Wu, F., Masoud, M., & Wu, X. Innovation-driven industrial green development: The moderating role of regional factors. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 222, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifset, R. , Kalimo, H., Jukka, A., Kautto, P., & Miettinen, M. Restoring the incentives for eco-design in extended producer responsibility: The challenges for eco-modulation. Waste Management 2023, 168, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. T. , Chiang, C. W., Cai, J. N., Chang, H. Y., Ku, Y. N., & Schneider, F. Evaluating the waste and CO2 reduction potential of packaging by reuse model in supermarkets in Taiwan. Waste Management 2023, 160, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]