1. Introduction

For critically ill patients in the intensive care unit with severe bacterial infections, the rapid and targeted initiation of adequate antibiotic therapy is of utmost importance for the patient’s outcome. However, antibiotic resistance has an increasingly important influence on the effectiveness of therapy and the chances of clinical recovery. The current worldwide increase in antibiotic-resistant bacteria has therefore been defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as one of the 10 greatest global health threats to humanity [

1,

2,

3], which requires decisive action through differentiated measures.

Antibiotic resistance is mainly caused by overuse or misuse of antibiotics. The choice of substance used plays the major role here, but dosage aspects and the resulting low antibiotic levels in the blood or the target organ system are also relevant, as this can lead to the selection of resistant subpopulations of pathogens under antibiotic therapy. The choice of substance as well as the appropriate dosage of antibiotics is therefore not only important for patient outcome, but also for the development of resistance itself. Therefore, structured optimization measures against antibiotic resistance are of utmost medical importance. In addition to the pharmacological developments, the rational and responsible use of antibiotics is particularly important. This preventive approach to avoiding resistance is subsumed under the term Antibiotic Stewardship (ABS), also called antimicrobial stewardship (e.g. [

4]).

The aim of ABS is to treat patients in the best possible way and at the same time prevent selection processes and resistance from occurring in the bacteria. To this end, it would be desirable to regularly evaluate and optimize the rational use of antimicrobial substances with an integrative approach that combines routine intensive care and microbiological data from the clinic with mathematical and methodological analyses: a clinical decision support system. To establish such a system, however, the hurdles arising from the complexity of the clinical situation as briefly outlined below must be overcome.

At the beginning of an ABS with a chance of success is the clear identification of the infection. In addition to the actual microbiological identification of the pathogen, ABS includes in particular the selection of the appropriate antibiotic, including pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic aspects. Clinically, the efficacy of a substance is determined by measuring the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). The MIC is the lowest effective concentration of an antibiotic that still prevents the replication of a pathogen in a culture. Clinical threshold values defined for the respective pathogens (in Europe by the EUCAST - “European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing”) then identify a pathogen as resistant (R) or sensitive (S) to the respective antibiotic tested and support clinicians in selecting the correct substance in the form of the so-called antibiogram [

5]. However, the aspect of the active substance concentration achieved in the target compartment is also of decisive importance [

6,

7].

Attempts to ensure sufficiently high antibiotic levels and thus a sufficient dosage have been made, for example, by determining the blood or tissue levels of a substance as part of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) and any resulting dose adjustments [

8,

9]. However, a third category “I” in antibiograms (English for “increased exposure”) also addresses the requirement for sufficient antibiotic levels, which clinically means that the substance has been tested as sensitive but requires an increased dosage. With regard to the overall cohort, the local resistance situation in the form of ward and/or hospital-specific resistance statistics also plays a relevant role.

As mentioned, the clinical requirements of ABS also include careful and appropriate microbiological diagnostics. A comprehensive prevalence and mortality study recently addressed which pathogens are the most problematic cases [

3]. In summary, in 2019, approximately 14% of all deaths were due to a bacterial infection, based on the 33 most important pathogens. Furthermore, 56% of sepsis-associated deaths died as a result of these 33 infections. It is also noteworthy that 55% of deaths from the 33 bacterial species were due to infections of

Previously, the 6 pathogens from the so-called ESKAPE series

Enterococcus faecium

Staphylococcus aureus

Klebsiella pneumoniae

Acinetobacter baumannii

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Enterobacter

were discussed as particularly critical with the highest clinical relevance [

2]. It almost goes without saying that successful ABS must keep an eye on the prevalence of these pathogens, which are classified as particularly dangerous, especially with regard to the development of resistance.

In a recent article we presented first steps toward harnessing the complex dynamics of antibiotic resistance [

10]. These analyses have been based on the clinical and microbiological data of a German hospital over an observation period of more than 7 years, which we evaluated descriptively and semi-quantitatively in order to obtain a basis for informed and intelligent action in terms of antibiotic stewardship. The main focus was on the particularly dangerous pathogens mentioned above. The aim of the present work is to extend the results from the recent study and deepen the insights by analyzing the same data set with a focus on the heterogeneity of antibiotic use.

So far we observed an increase in the resistance rate with increasing overall consumption, while increases over time independent of consumption are fairly moderate. Vancomycin and cefuroxim turned out as exceptions in the development of resistance, as resistance to these substances appears to decrease with increasing consumption. However, there have been substantial dose adjustments for these substances, which are likely to be decisive here. An intra-host increase in resistance due to treatment time on the one hand and repeated treatments on the other has been observed.

Within the sub-cohort of ineffectively treated patients due to resistance, mortality increased on average, but with ampicillin/sulbactam being a striking exception. Patients with infections caused by ampicillin-resistant bacteria turned out to have a lower mortality rate. Globally, 5 million infection-related deaths per year are attributed to antimicrobial resistance (cf. [

11]). However, this does not rule out the possibility of sporadic resistant germ variants that are less deadly than the susceptible variants. Interaction with a presumably greatly reduced microbiome is more likely. Further confounders can only be speculated upon.

The observed resistance rates of the eight most frequently administered antibiotics showed a temporal variability that includes random fluctuations as well as decidedly regular cycles. It has been argued that, in terms of evolutionary dynamics, it seems plausible that the proportion of resistant pathogen variants in a population follows a logistic growth process toward a carrying capacity, i.e., a stable equilibrium [

11]. The fluctuations we observed do not support this presumably oversimplified evolutionary dynamic, which can at best be maintained with constant or even increasing consumption of the corresponding antibiotic. Rather, it seems likely that with declining antibiotic consumption, the susceptible pathogen variant can gain an evolutionary advantage. In other words, the development of resistance is not a strictly irreversible evolutionary process. The concept of equilibrium in the sense of an asymptotically stable fixed point of one-dimensional logistic dynamics does not reflect the coupled dynamics of antibiotic consumption and evolutionary resistance development. The assumption tested by the authors [

11] that carrying capacity correlates with consumption, i.e., that environmental capacity is a function of consumption, is not particularly meaningful.

However, we have not yet considered individual pathogen-antibiotic pairs (referred to by [

11] as bug-drug pairs) in our evaluation, what we make up for in this publication. Specifically, we present a simple model that couples the “idle” dynamics in the form of a logistic growth process with differential antibiotic consumption. We consider this type of coupling to be more appropriate than a direct dependence of a presumed carrying capacity on consumption. In this regard, it is worth noting that the proportion of resistance to piperacillin/tazobactam across all pathogens shows remarkable constancy over time [

10], suggesting that the (total) trajectory in this special case has indeed stabilized at a carrying capacity that has already been reached. This is not a contradiction for the case of a constant consumption over the entire observation time.

Also shown previously (cf. [

10]), the time series associated with the various antibiotics showed pairwise time lag correlations, which indicates the existence of retardedly mediated cross-resistance. In particular, we refer back to these last-mentioned observations of complex time-delayed interactions in order to take a closer look at these relationships specifically with regard to possible resonances between dynamic consumption patterns and the incidence of resistance.

In this context, it is worth recalling the idea of cyclical variation in antibiotic use to suppress resistance without dispensing with antibiotic treatment and without the pressure to constantly develop new active agents. We therefore revisit the most important basic ideas and existing work already described in our recently published papers to outline the background [

10,

12]. Cyclical allocation of antibiotics or so-called mixing (other terms are in circulation) are strategies at hospitals with the aim of contributing to a reduction in the prevalence of resistant germs by means of spatial (between departments, mixing) or cyclical (temporal) variations in the proportions of consumption of different antibiotic groups. According to a systematic review [

13], there is only one randomized controlled trial (RCT) on the effectiveness of such strategies. However, there are some studies that at least compared systematic cyclical administration strategies and standard administration between clinics or carried out before-and-after comparisons (cross-over) [

13,

14]. In the RCT study, cycling performed worse than the control ABS [

13].

Noteworthy, in numerous studies, “mixing” was chosen as the control strategy, i.e. an alternating exchange between departments. Cycling, i.e. a temporal periodic change simultaneously across all departments, showed no difference to the mixing procedure, which is not surprising from a theoretical point of view if one assumes sufficiently isolated conditions between the departments. Nevertheless, all studies (RCT and cohort studies) including the cross-over studies were considered together in the meta-analyses, regardless of whether they tested against “mixing” or “without strategy”, which must be viewed very critically and neglects the important separate consideration of mixing and cycling. Of note, in the meta-analysis by [

14], a distinction was made between the two control strategies as part of a secondary analysis. In Gram-positive bacteria, the cycling strategy showed a slightly stronger effect in terms of avoiding resistance. It appears that there is no general evaluation independent of other biological and medical boundary conditions. It is therefore possible that the cycling concept itself is not well thought out. The question of whether cycling or mixing contributes to the “rational and responsible use of antibiotics” has therefore not been conclusively clarified.

Cycling according to a fixed scheme (scheduled cycling) means that the informed, i.e. rational use of antibiotics is deliberately avoided, so that conceptually a control rather than an intervention strategy is defined here. In this context, it is worth recalling that in a seminal cycling study published by [

15], the authors investigated interrupted time series in the administration of aminoclycosides. These irregular antibiotic prescriptions followed an observed pattern in the emergence of resistant germs rather than a fixed periodic cycling scheme. In retrospect, it appears that the authors intuitively used the method that is now referred to as “clinical cycling” and which is actually superior to scheduled cycling because it is based on clinical evidence for the necessity of adapting the antibiotic consumption. Unsurprisingly, scheduled cycling is explicitly not recommended in a German S3 guideline [

16], whose validity has expired 2024-01-31, by the way.

Despite the aforementioned counterarguments, the poor performance of “scheduled cycling” does no speak against cycling per se, but rather against cycling that is not carried out intelligently. One could even say that conceptually, scheduled cycling corresponds more to a “placebo-like” (control) ABS, whereas clinical cycling based on clinical expertise corresponds to the intervention group. In the context of this interpretation, the many studies on cycling are in fact rather evaluation procedures for assessing whether the respective “clinical cycling” is viable on the basis of implicit clinical knowledge in comparison to a non-informed cycling strategy. In other words, despite the clinically contra-indicated settings of scheduled cycling programs, these strategies represent a kind of basic model structure whose quantitative explanation is the basis for the description of more complex switching strategies (clinical cycling).

In our own preliminary work [

12], we have created and published a mathematical framework that is suitable for adequately quantifying the effect of clinical cycling and, in borderline cases, scheduled cycling. Subsequent correlation analyses revealed a relationship between the heterogeneity of antibiotic consumption and the prevalence of resistant pathogens, indicating a reduction in the prevalence of resistant germs. The heterogeneity changes on the pathogen side follow the changes on the consumption side. It is worth mentioning that in most of the older studies conducted, a quantification of the degree of mixing or cyclic variation has rarely been used. An exception is the study by [

17], in which an antibiotic heterogeneity index (AHI) was used. This work was followed by few publications in which AHI or a similar quantification of heterogeneity was discussed (e.g. [

18]), but if so, then only in passing. Of note, AHI is invariant to swapping the antibiotic classes. This means that if the consumption shares of two antibiotics are swapped, AHI remains unchanged. This has to be kept in mind when discussing cycling strategies based on AHI. The view expressed in publication [

19] that the focus in ABS on strategies of cyclical prescribing has shifted to a focus on heterogeneity sounds as if these were disjoint strategies. However, when correctly quantified, variations in the administration of antibiotics, including cyclical prescribing, result in a corresponding change in heterogeneity.

Measures of heterogeneity or, more generally, of diversity are frequently used in ecological studies to calculate “mixing”, i.e. the degree of heterogeneity. These measures are related to entropies, which originated in statistical physics for the quantitative description of mixing processes (dispersions) and similar phenomena. The Shannon entropy known from information theory is, like AHI, a global entropy, i.e. invariant to permutations of the species. Local heterogeneity measures should be used in order to be able to record changes over time. The Kullback-Leibler entropy is such a local entropy and has proven its worth in our preliminary work in the context of ABS as well as of spatio-temporal epidemic patterns [

12,

20]. However, the concrete choice of the final form of the analysis algorithms depends on specific conditions.

Theoretically, it would be conceivable to extrapolate the observed mixing states of antibiotic consumption and predict the resistance incidence. Alternatively, it appears to be appealing to create possible interaction scenarios, in such a way that an “optimal cycling regime” defined by the best possible reduction of resistance is achieved. However, such a project is a real challenge due to the necessary constraints, such as those imposed by biological and clinical conditions and regulations. Our preliminary work represents an important step in this direction, also taking into account clinical constraints (antibiogram, pharmacokinetics and microbiological parameters, guidelines) [

8,

9,

10,

12,

20]. In this publication, an exploratory observational study, we explore the relationship between antibiotic consumption heterogeneity and resistance emergence for the intensive care unit of a German University hospital, located in Bochum.

4. Discussion

We analyzed secondary data from an intensive care unit with regard to the association between antibiotic use and the development of pathogen resistance to these antibiotics. This immediately reveals the greatest limitation, namely that secondary data analyses generally make it difficult to interpret the observed associations in a causal manner. However, we looked at the evolution of antibiotic resistance from a mathematical-dynamic modeling perspective, so that functional dependencies can be inferred with due caution, i.e., only within the scope of the validity of the dynamic models.

In general, it is valid that secondary data analyses using mechanistic models in biology and medicine–meaning models that incorporate well-defined laws–can achieve a similarly high level of evidence as experimental studies. In fact, the field of antibiotic stewardship must be structurally classified as healthcare research or epidemiological research rather than as a field of traditional clinical studies. Controlled and randomized studies are only possible, if at all, as cluster-randomized studies or with sequential intervention and control designs (stepped wedge, cf. [

32]). As in healthcare research, there is often an extremely long delay before the intervention takes effect, even if it is significant. This so-called EbM-lag (see e.g. [

33]) necessitates the use of pragmatic study designs, preferably incorporating mechanistic models to ensure a high degree of predictability.

In the present study, too, it would be desirable to refer to biochemical laws, but realistically, we are dependent here on the recording and modeling of phenotypic characteristics or proxy variables. The sensitivity levels S, I, and R would be a good example. Using the exact MICs instead of the three-part classification would certainly be an option, but it would require increased effort in the laboratory. We are keeping this option open for upcoming analyses, in particular to better reflect the problematic classification of the middle category “increased exposure.” Relying on biochemical laws at this point would inflate the degree of complexity to an unmanageable level. Nevertheless, we are convinced that even modeling using intrinsic variables that capture a structural state macroscopically can contribute to easily interpretable findings and allow conclusions to be drawn.

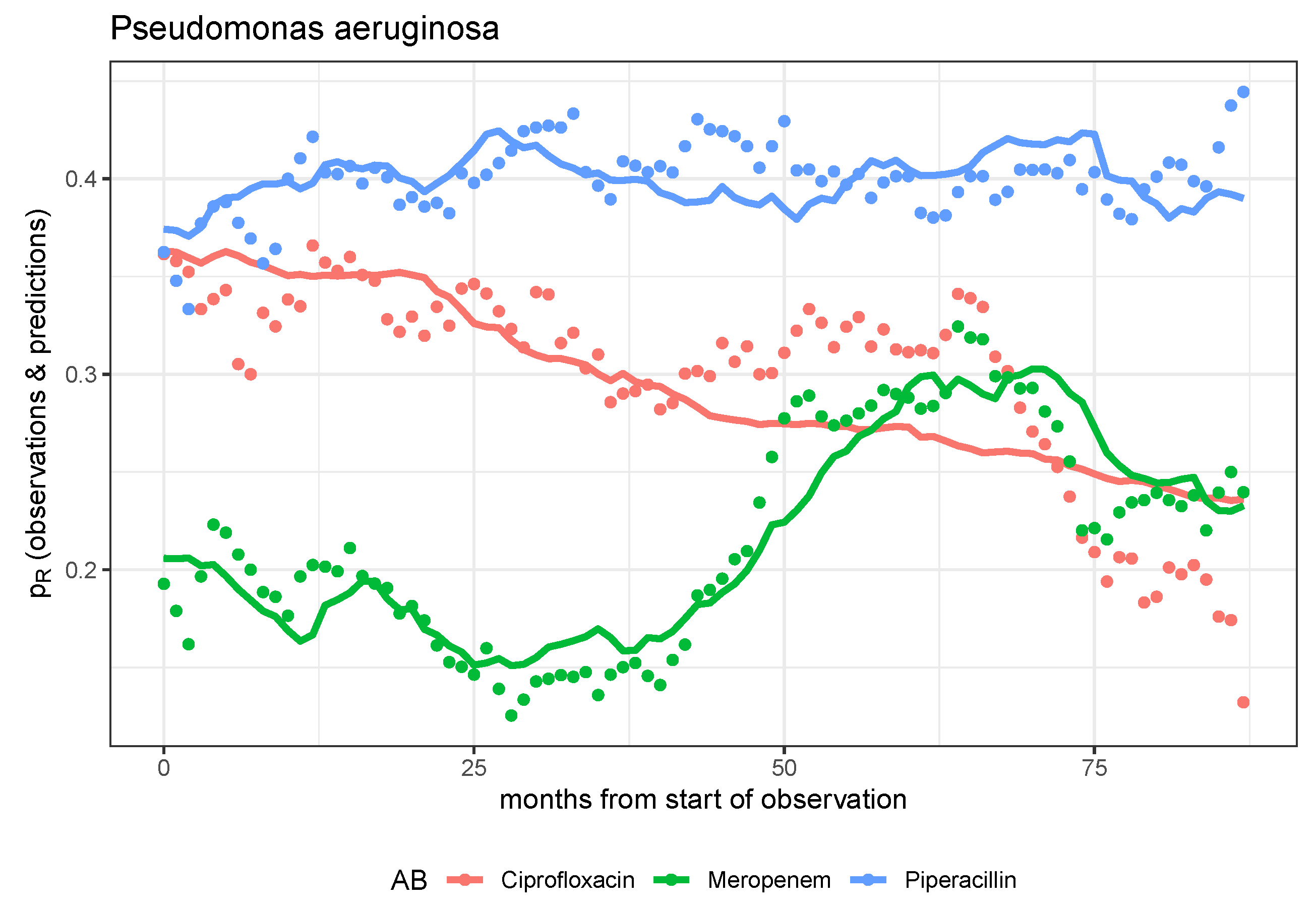

Specifically, back to what we did, mutually independent dynamic models designed to predict the evolution of pathogen resistance to antibiotics for each pathogen-antibiotic pair have generally proven to be insufficient. The dynamics of resistance can only be explained reasonably satisfactorily for a few pairs on the basis of these mono-causal models, whereby in these cases it is most often the effects of the control parameters describing the transfer from consumption to resistance that become significant. We postulate that there are interactions between pathogen-antibiotic pairs, for example in the form of cross-resistance. However, empirical validation of suitable coupled dynamic models is not feasible on the basis of the data set, which is too small for this purpose. However, we note that the model-based prediction is particularly good for the combination of P. aeruginosa and meropenem. If further studies show that the meropenem resistance of P. aeruginosa is independent of the consumption of all other antibiotics, the only stewardship strategy ultimately available is the long-term reduction of meropenem consumption.

Alternatively, we move to a higher phenomenological level, so to speak, and switch to a scalar quantification of the heterogeneity of antibiotic consumption, i.e., to the description of an intrinsic structural feature. We also summarize the resistances of all pathogens. In this way, we can provide some evidence that the evolution of resistance can be favorably influenced, i.e., resistance reduced, by a constant mixing of antibiotic consumption shares. A suitable quantitative representation of the mixing process is provided by the Kullback-Leibler divergence for a momentary distribution of consumption shares, whereby the reference distribution is defined by the distribution in the immediately preceding time interval. This representation is equivalent to Shannon entropy with this very reference instead of uniform distribution.

The mere statement that constant mixing in antibiotic use is beneficial in terms of resistance development may seem sobering. The scalar quantification of the mixing process, which is therefore subject to massive information loss, is difficult to operationalize. Realistically, however, due to numerous clinical and biological restrictions, only a few antibiotics are suitable for consumption permutations anyway. From our perspective, it makes sense to subject what is known as clinical cycling to much stricter control and to move beyond pure unspoken heuristics into a controlled exploratory phase. It would be desirable for several clinics to coordinate their efforts so that comparisons of different strategies can ultimately be carried out, thereby creating at least a quasi-experimental situation, perhaps even in the form of cluster randomization.

It should be noted that the evaluations of the time series depend to a not entirely negligible extent on the smoothing procedures used. Even monthly aggregation results in a loss of information, but due to the highly fluctuating time series using smaller base elements, it is no longer possible to evaluate them meaningfully, at least not within the framework of the model approaches used. The smoothing and aggregate levels applied are the result of a compromise between fundamental feasibility and precision. Similarly, the restriction to the most commonly administered antibiotics and the most important pathogens represents a limitation that was unavoidable due to the otherwise unmanageable fluctuations. In the long term, however, antibiotics that have been used less frequently to date should also be included in strategic considerations.

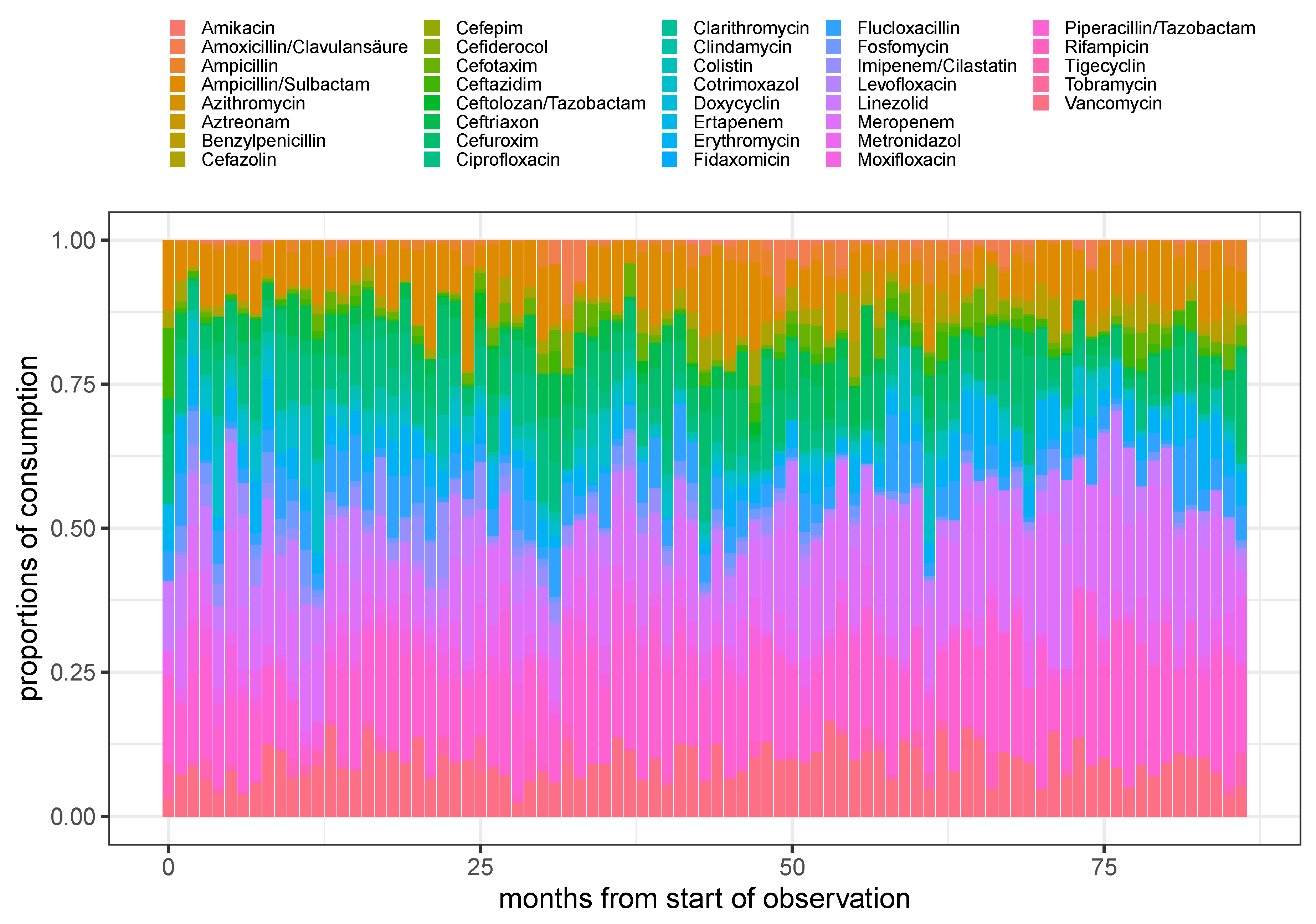

Figure 1.

Stacked barplot of the proportions of consumption for all (not too rarely) administered antimicrobials over time using monthly aggregated consumptions.

Figure 1.

Stacked barplot of the proportions of consumption for all (not too rarely) administered antimicrobials over time using monthly aggregated consumptions.

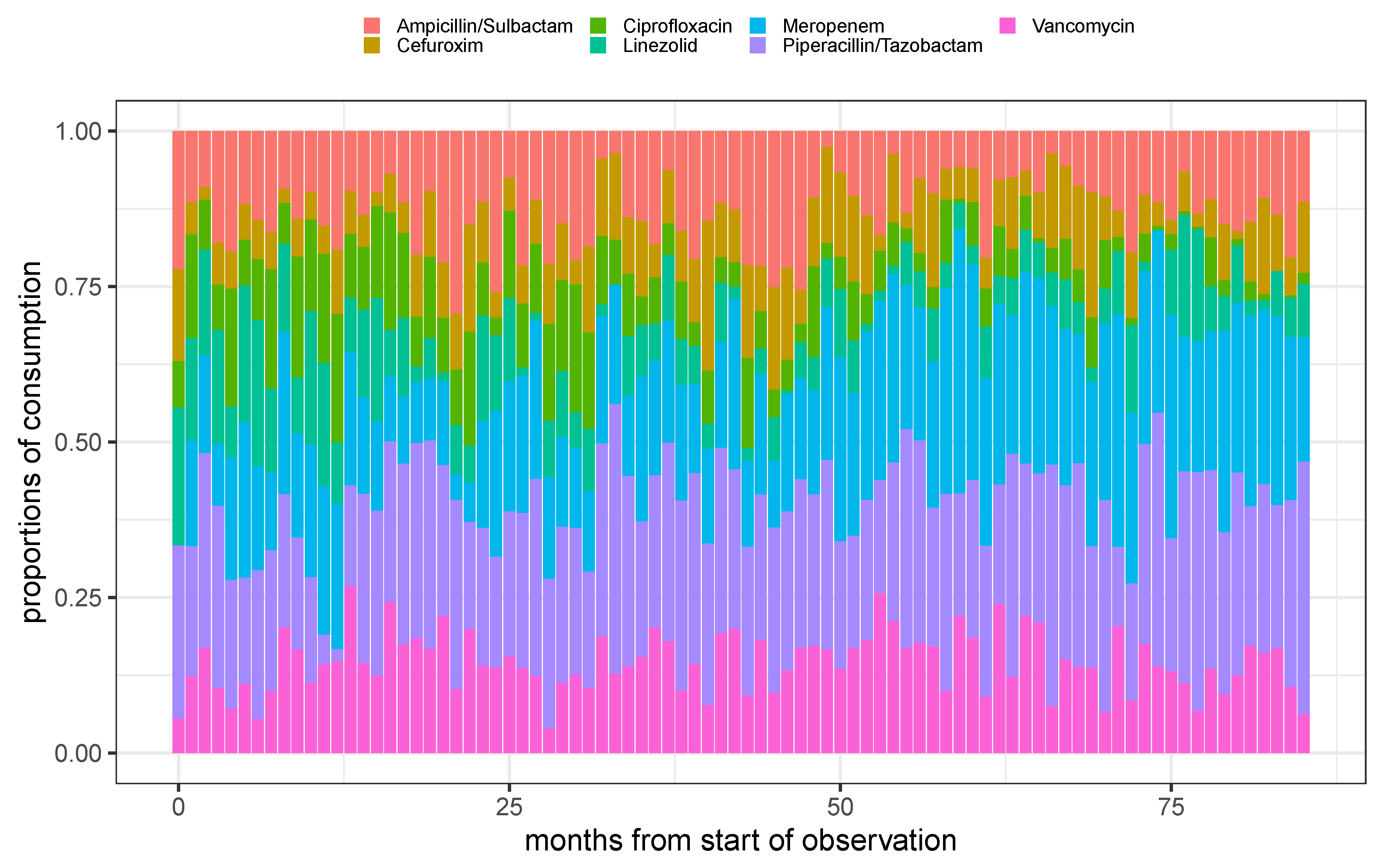

Figure 2.

Stacked barplot of the proportions of consumption for the 7 most frequent administered antimicrobials over time using monthly aggregated consumptions.

Figure 2.

Stacked barplot of the proportions of consumption for the 7 most frequent administered antimicrobials over time using monthly aggregated consumptions.

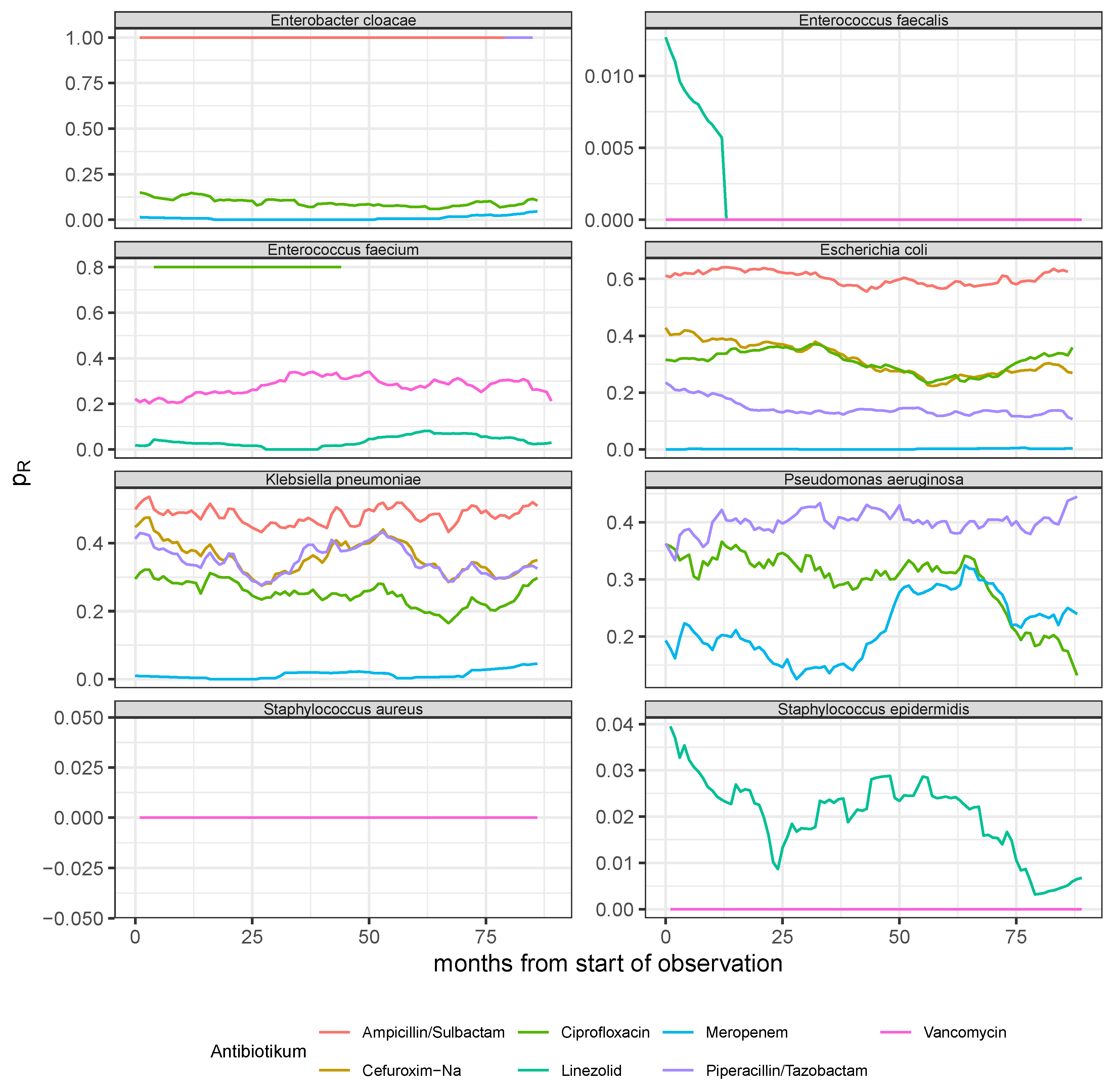

Figure 3.

Resistance rate time series derived from monthly aggregated antibiogram results of the 8 most common pathogens (see panel headers) with respect to the experimentally applied substances out of the 7 most frequently administered antibiotics (cf. legend for the color code).

Figure 3.

Resistance rate time series derived from monthly aggregated antibiogram results of the 8 most common pathogens (see panel headers) with respect to the experimentally applied substances out of the 7 most frequently administered antibiotics (cf. legend for the color code).

Figure 4.

Observed time series and model predictions of the three rates of resistance of P. aeruginosa to ciprofloxacin, meropenem, and piperacillin, respectively.

Figure 4.

Observed time series and model predictions of the three rates of resistance of P. aeruginosa to ciprofloxacin, meropenem, and piperacillin, respectively.

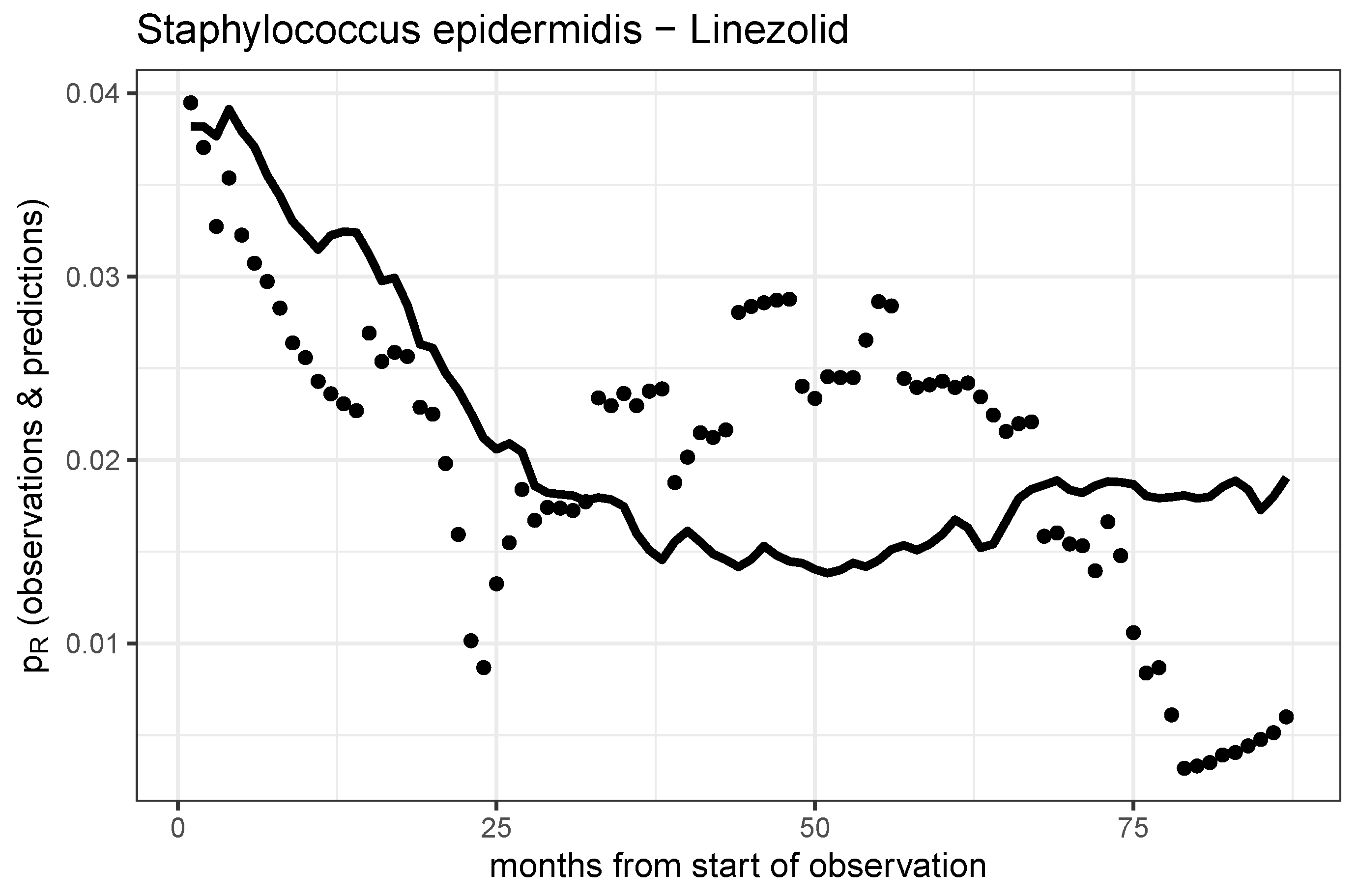

Figure 5.

Observed time series and model prediction of the rate of resistance of S. epidermidis to linezolid.

Figure 5.

Observed time series and model prediction of the rate of resistance of S. epidermidis to linezolid.

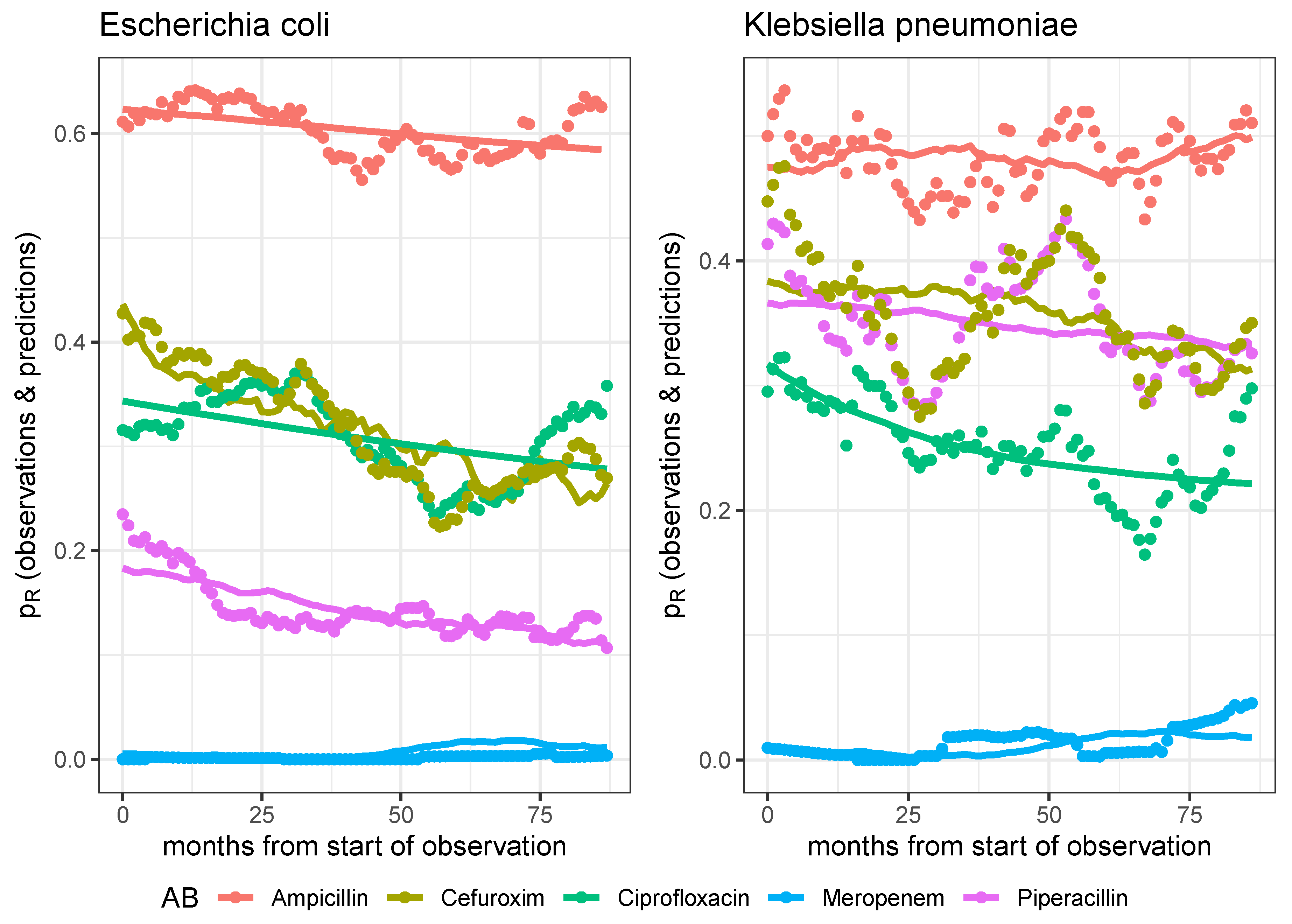

Figure 6.

Observed time series and model predictions of the respective five rates of resistance of E. coli (left panel) and K. pneumoniae (right panel) to ciprofloxacin, meropenem, piperacillin, cefuroxim, and ampicillin, respectively.

Figure 6.

Observed time series and model predictions of the respective five rates of resistance of E. coli (left panel) and K. pneumoniae (right panel) to ciprofloxacin, meropenem, piperacillin, cefuroxim, and ampicillin, respectively.

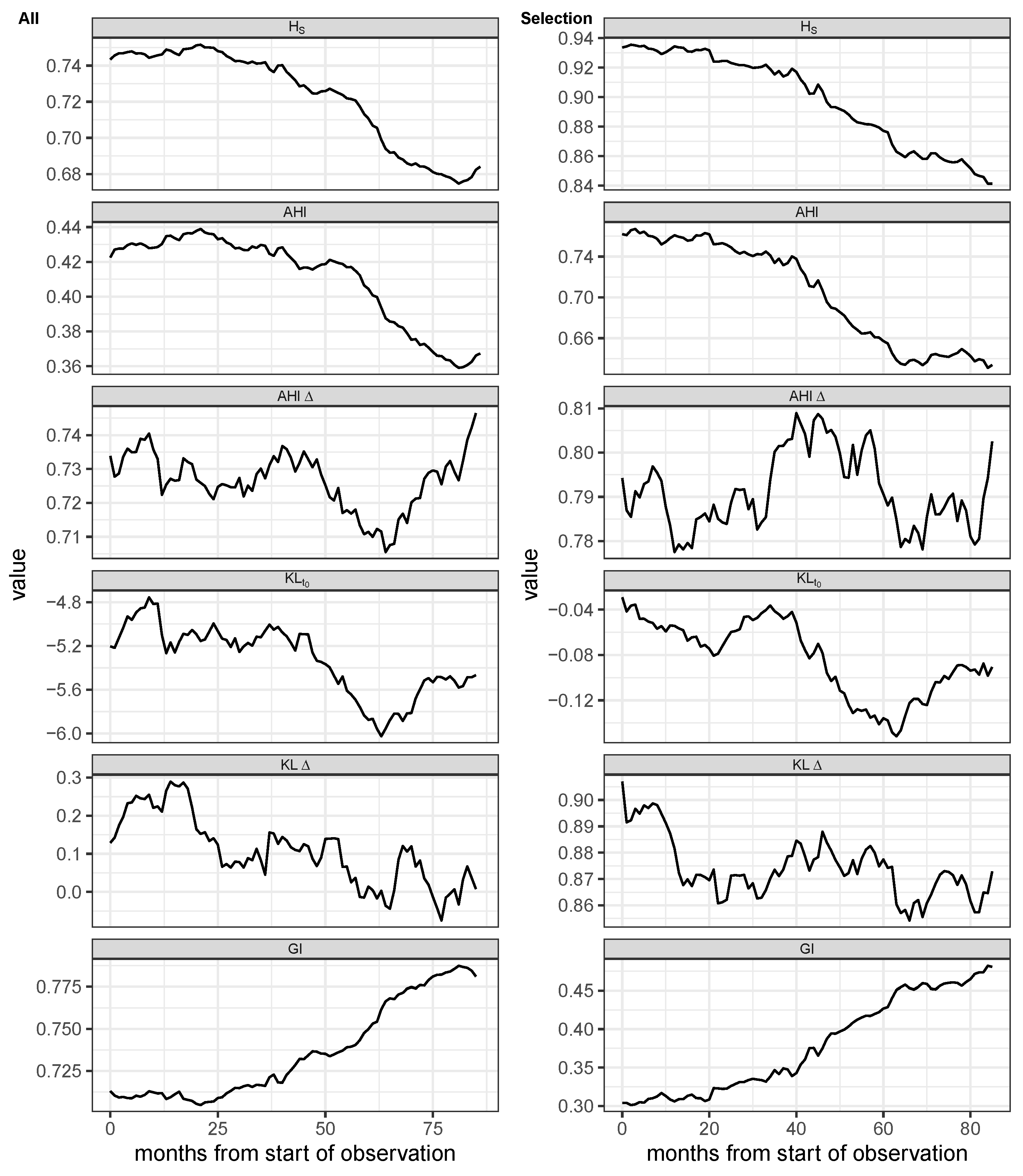

Figure 7.

Shannon entropy (), Antibiotic Heterogeneity Index (AHI) with uniform distribution as reference, AHI with distribution at previous month as reference (AHI), two versions of Kullback-Leibler divergence, one with distribution at the first observation as reference (), and one with the distribution at previous month as reference (KL), and Gini Index (GI) of monthly aggregated proportional consumption time series. First column: All antimicrobials excluding antivirals, antifungals, and rarely administered substances. Second column: Subset containing the 7 most frequent antibiotics. The entropy time series are based on monthly aggregated antibiotics consumptions and were smoothed via moving average over 12 months.

Figure 7.

Shannon entropy (), Antibiotic Heterogeneity Index (AHI) with uniform distribution as reference, AHI with distribution at previous month as reference (AHI), two versions of Kullback-Leibler divergence, one with distribution at the first observation as reference (), and one with the distribution at previous month as reference (KL), and Gini Index (GI) of monthly aggregated proportional consumption time series. First column: All antimicrobials excluding antivirals, antifungals, and rarely administered substances. Second column: Subset containing the 7 most frequent antibiotics. The entropy time series are based on monthly aggregated antibiotics consumptions and were smoothed via moving average over 12 months.

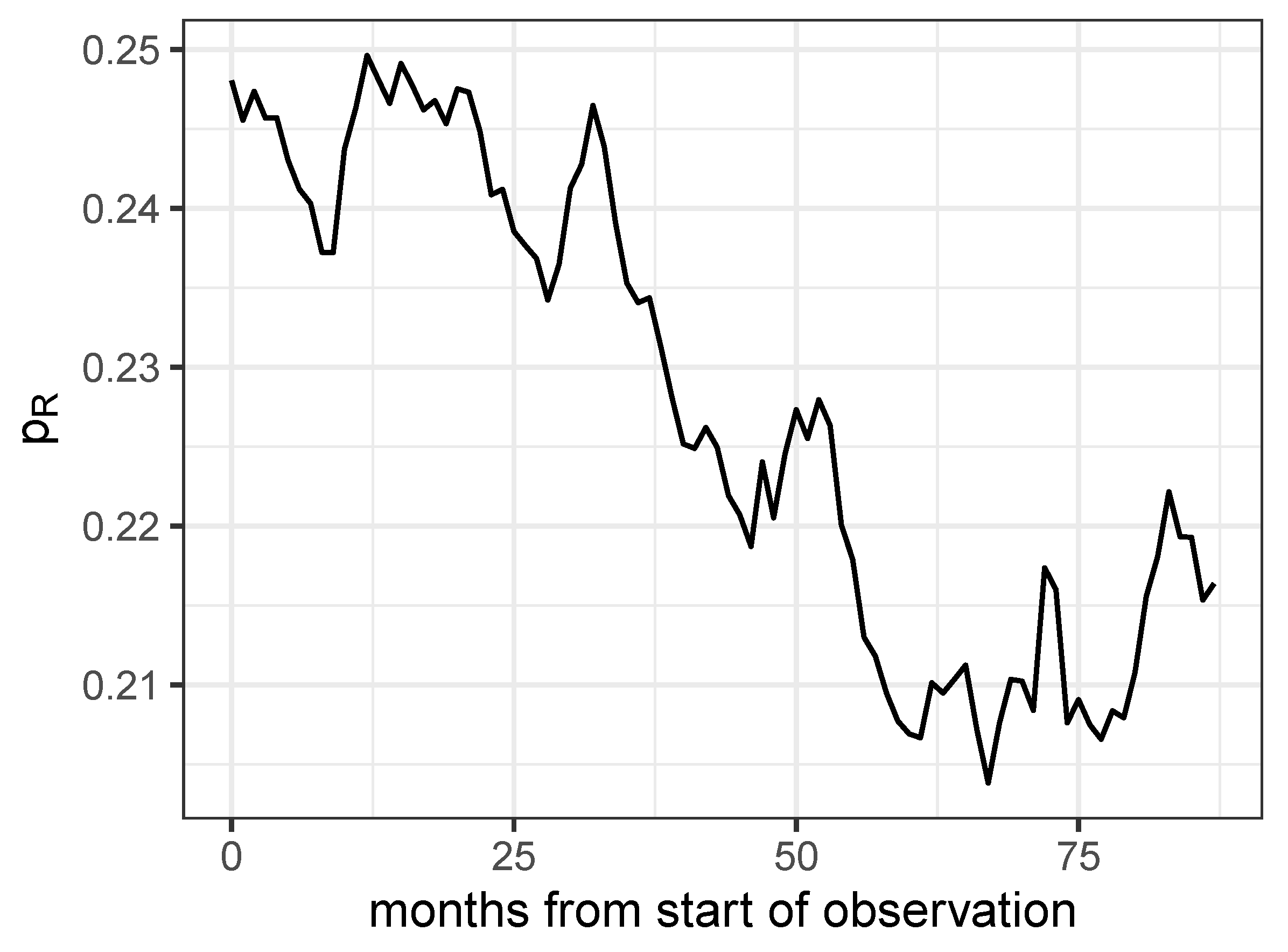

Figure 8.

Proportion of antibiograms detected as resistant for all combinations of the 8 most frequently investigated pathogens and the 7 most frequently administered antibiotics.

Figure 8.

Proportion of antibiograms detected as resistant for all combinations of the 8 most frequently investigated pathogens and the 7 most frequently administered antibiotics.

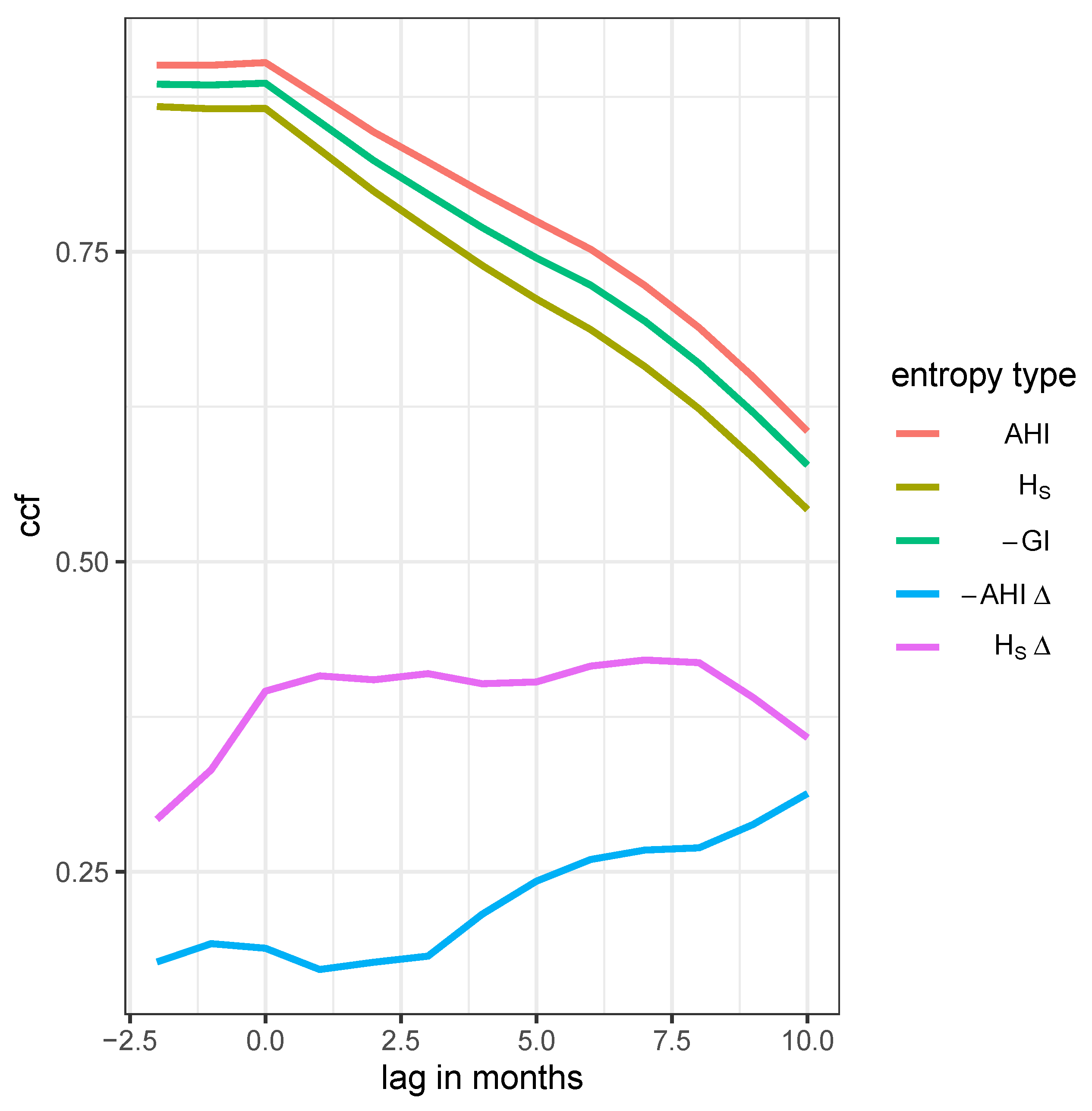

Figure 9.

Time lag cross correlation function (CCF) between the proportion of resistance and one of five entropies: AHI, Shannon entropy (), Gini index (GI), differential AHI, and the differential Shannon entropy , respectively, as annotated in the legend labels.

Figure 9.

Time lag cross correlation function (CCF) between the proportion of resistance and one of five entropies: AHI, Shannon entropy (), Gini index (GI), differential AHI, and the differential Shannon entropy , respectively, as annotated in the legend labels.

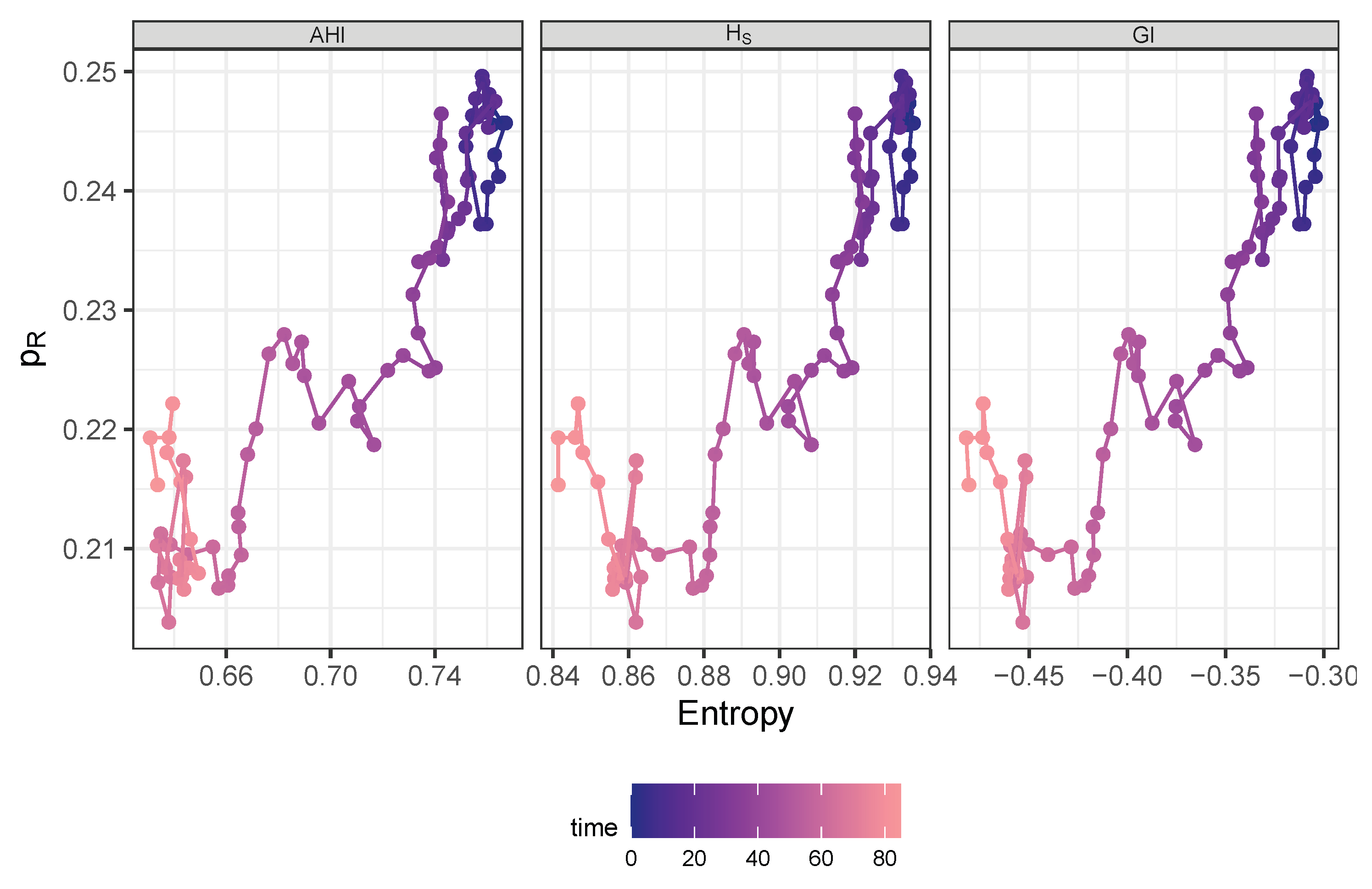

Figure 10.

Trajectory in phase space spanned by AHI (left panel), Shannon entropy (middle panel), or negative Gini index (right panel), respectively and share of resistance drawn with color gradient by time starting at dark blue and ending at bright red.

Figure 10.

Trajectory in phase space spanned by AHI (left panel), Shannon entropy (middle panel), or negative Gini index (right panel), respectively and share of resistance drawn with color gradient by time starting at dark blue and ending at bright red.

Table 1.

The 9 most frequently administered antimicrobials.

Table 1.

The 9 most frequently administered antimicrobials.

| antibiotic |

n days |

n individuals |

| piperacillin/tazobactam i.v. |

8,227 |

1,752 |

| meropenem i.v. |

6,643 |

1,011 |

| caspofungin i.v. |

3,598 |

439 |

| vancomycin i.v. |

3,455 |

637 |

| ampicillin/sulbactam i.v. |

2,927 |

903 |

| flucloxacillin i.v. |

2,448 |

406 |

| linezolid i.v. |

2,434 |

371 |

| ciprofloxacin i.v. |

2,384 |

547 |

| cefuroxim i.v. |

2,265 |

596 |

Table 2.

Summary table of demographic characteristics stratified by antibiotic treatment flag. Subjects are ward stays.

Table 2.

Summary table of demographic characteristics stratified by antibiotic treatment flag. Subjects are ward stays.

| Characteristic |

Overall 1

|

w/o AB 1

|

with AB 1

|

p-value 2

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

| female |

4,141 (45%) |

2,120 (50%) |

2,021 (41%) |

|

| male |

5,057 (55%) |

2,161 (50%) |

2,896 (59%) |

|

| Unknown |

3 |

0 |

3 |

|

| Age |

66 (54, 78) |

66 (52, 78) |

66 (55, 77) |

0.4 |

| Age Group |

|

|

|

0.5 |

| < median |

4,436 (48%) |

2,081 (49%) |

2,355 (48%) |

|

| ≥ median |

4,765 (52%) |

2,200 (51%) |

2,565 (52%) |

|

| Destination |

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

| death |

1,545 (17%) |

487 (11%) |

1,058 (22%) |

|

| external hospital |

3,121 (34%) |

1,405 (33%) |

1,716 (35%) |

|

| home |

4,535 (49%) |

2,389 (56%) |

2,146 (44%) |

|

| Hospital Duration |

14 (7, 26) |

9 (4, 16) |

21 (11, 37) |

< 0.001 |

| ICU Duration |

2 (1, 5) |

1 (1, 2) |

4 (1, 9) |

< 0.001 |

Table 3.

Frequency table showing the number of occurrences of each sensitivity class S, I, R, and n.a., respectively.

Table 3.

Frequency table showing the number of occurrences of each sensitivity class S, I, R, and n.a., respectively.

| sensitivity |

challenges |

distinct IDs |

| n.a. |

537 |

148 |

| I |

12,309 |

2,477 |

| R |

41,525 |

2,951 |

| S |

101,223 |

3,406 |

Table 4.

Ten most frequently isolated pathogens.

Table 4.

Ten most frequently isolated pathogens.

| Pathogen |

n |

| Escherichia coli |

3,091 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis |

2,664 |

| Candida albicans |

2,299 |

| Enterococcus faecium |

1,745 |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

1,579 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae |

1,336 |

| Candida glabrata |

1,265 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

1,126 |

| Enterococcus faecalis |

644 |

| Enterobacter cloacae |

614 |

Table 5.

Maximum likelihood parameter estimates of the dynamic model predicting the resistance rate time courses of pathogen-antibiotic pairs. Abbreviations used: AB=antibiotic, patho=pathogen, Cipro=ciprofloxacin, Mero=meropenem, Piper=piperacillin/tazobactam, Line=Linezolid, P.aeru=Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S.epiderm=Staphylococcus epidermidis. The logarithmic parameters were actually estimated with the corresponding estimated values “log(estimates)”, therefore, the standard errors stderr refer to these values.

Table 5.

Maximum likelihood parameter estimates of the dynamic model predicting the resistance rate time courses of pathogen-antibiotic pairs. Abbreviations used: AB=antibiotic, patho=pathogen, Cipro=ciprofloxacin, Mero=meropenem, Piper=piperacillin/tazobactam, Line=Linezolid, P.aeru=Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S.epiderm=Staphylococcus epidermidis. The logarithmic parameters were actually estimated with the corresponding estimated values “log(estimates)”, therefore, the standard errors stderr refer to these values.

| patho-AB-pair |

parameter |

estimate |

log(estimate) |

stderr |

p-value |

| P.aeru-Cipro |

|

0.363 |

|

0.470 |

0.031 |

| |

r |

0.008 |

|

NaN |

NaN |

| |

C |

0.163 |

|

1.479 |

0.220 |

| |

|

0.003 |

|

1.668 |

0.000 |

| P.aeru-Mero |

|

0.206 |

|

0.633 |

0.013 |

| |

r |

0.014 |

|

9.670 |

0.659 |

| |

C |

0.122 |

|

3.666 |

0.565 |

| |

|

0.004 |

|

1.930 |

0.004 |

| P.aeru-Piper |

|

0.380 |

|

0.344 |

0.005 |

| |

r |

0.001 |

|

8.582 |

0.413 |

| |

C |

0.182 |

|

2.221 |

0.443 |

| |

|

0.002 |

|

4.721 |

0.176 |

| S.epiderm-Line |

|

0.038 |

|

4.104 |

0.426 |

| |

r |

0.009 |

|

24.934 |

0.852 |

| |

C |

0.021 |

|

20.238 |

0.848 |

| |

|

0.001 |

|

7.014 |

0.297 |

Table 6.

Maximum likelihood parameter estimates of the dynamic model predicting the resistance rate time courses of pathogen-antibiotic pairs. Abbreviations used: AB=antibiotic, patho=pathogen, Cipro=ciprofloxacin, Mero=meropenem, Piper=piperacillin/tazobactam, Ampi=ampicillin/sulbactam, Cefu=cefuroxim, K.pneu=Klebsiella pneumoniae, E.coli=Escherichia coli. The logarithmic parameters were actually estimated with the corresponding estimated values “log(estimates)”, therefore, the standard errors stderr refer to these values.

Table 6.

Maximum likelihood parameter estimates of the dynamic model predicting the resistance rate time courses of pathogen-antibiotic pairs. Abbreviations used: AB=antibiotic, patho=pathogen, Cipro=ciprofloxacin, Mero=meropenem, Piper=piperacillin/tazobactam, Ampi=ampicillin/sulbactam, Cefu=cefuroxim, K.pneu=Klebsiella pneumoniae, E.coli=Escherichia coli. The logarithmic parameters were actually estimated with the corresponding estimated values “log(estimates)”, therefore, the standard errors stderr refer to these values.

| patho-AB-pair |

parameter |

estimate |

log(estimate) |

stderr |

p-value |

| E.coli-Cipro |

|

0.344 |

|

0.646 |

0.098 |

| |

r |

0.008 |

|

5.802 |

0.411 |

| |

C |

0.028 |

|

13.496 |

0.791 |

| |

|

0.000 |

|

18.798 |

0.590 |

| E.coli-Mero |

|

0.005 |

|

NaN |

NaN |

| |

r |

0.001 |

|

8.409 |

0.42 |

| |

C |

0.288 |

|

NaN |

NaN |

| |

|

0.000 |

|

NaN |

NaN |

| E.coli-Piper |

|

0.183 |

|

1.245 |

0.173 |

| |

r |

0.056 |

|

3.829 |

0.451 |

| |

C |

0.010 |

|

8.209 |

0.571 |

| |

|

0.001 |

|

8.408 |

0.407 |

| E.coli-Ampi |

|

0.623 |

|

0.317 |

0.136 |

| |

r |

0.001 |

|

NaN |

NaN |

| |

C |

0.095 |

|

NaN |

NaN |

| |

|

0.000 |

|

28.409 |

0.736 |

| E.coli-Cefu |

|

0.436 |

|

1.074 |

0.440 |

| |

r |

0.165 |

|

6.518 |

0.782 |

| |

C |

0.270 |

|

1.349 |

0.331 |

| |

|

0.008 |

|

11.319 |

0.668 |

| K.pneu-Cipro |

|

0.317 |

|

0.848 |

0.175 |

| |

r |

0.097 |

|

5.190 |

0.653 |

| |

C |

0.212 |

|

1.647 |

0.346 |

| |

|

0.000 |

|

20.356 |

0.679 |

| K.pneu-Mero |

|

0.008 |

|

NaN |

NaN |

| |

r |

0.012 |

|

NaN |

NaN |

| |

C |

0.186 |

|

NaN |

NaN |

| |

|

0.000 |

|

2.709 |

0.004 |

| K.pneu-Piper |

|

0.366 |

|

0.601 |

0.095 |

| |

r |

0.007 |

|

7.394 |

0.496 |

| |

C |

0.075 |

|

NaN |

NaN |

| |

|

0.001 |

|

4.123 |

0.073 |

| K.pneu-Ampi |

|

0.475 |

|

0.298 |

0.012 |

| |

r |

0.004 |

|

6.965 |

0.432 |

| |

C |

0.649 |

|

0.539 |

0.423 |

| |

|

0.002 |

|

6.976 |

0.371 |

| K.pneu-Cefu |

|

0.384 |

|

0.691 |

0.166 |

| |

r |

0.015 |

|

7.140 |

0.557 |

| |

C |

0.141 |

|

3.101 |

0.527 |

| |

|

0.004 |

|

7.407 |

0.445 |