INTRODUCTION

Patients previously treated with antibiotics are more likely to carry and be infected by antibiotic-resistant bacteria [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This resistance arises from two key biological phenomena: the alteration of the body’s microbiome by antibiotics, promoting resistant bacteria growth, and the survival and increased numbers of “persister” phenotypes through initial treatments [

2,

3,

5]. The link between antibiotic use and resistance is intricate, with empirical evidence indicating that this correlation can persist for years [

6], though it typically diminishes much sooner and often has resolved 6 months after antibiotic use [

4]. But antibiotic-resistant bacteria are acquired and can persist for long periods of time in travelers, even when they have not taken any antibiotics [

7,

8]. Thus, there are factors other than just antibiotic use associated with “persistence”.

Global studies reveal that poor infection control, driven by factors like inadequate socio-economic infrastructure, is more strongly associated with resistance spread than antimicrobial usage itself [

9,

10]. Factors such as poor governance, corruption, inadequate refrigeration, compromised water quality, and insufficient sanitation contribute to the proliferation of resistant bacteria. Environmental and socio-economic factors create differences in individual infectiousness and risks of becoming infected, can complicate the understanding of the “persistence” of antibiotic resistance.

This paper aims to explain how heterogeneous risk of infection among individuals (a familiar complication in several other medical contexts [

5,

11,

12,

13,

14]) can lead to an observed correlation between resistance and historical antimicrobial use even when that correlation is not causally related. Hence, it is prudent to take extra care when considering the persistence of antibiotic resistance that is measured from observational studies.

Segregating observed data into sub-samples of similar individuals is one way to reduce heterogeneity in the unobserved characteristics of the sample data. For example, settings with higher infection rates (and acquisition and carriage of resistant bacteria), such as hospitals and aged care facilities, are typically analyzed separately from community data. When creating separate sub-samples is impractical, statistical models aim to incorporate covariates to account for underlying unobserved risk rates.

However, the diversity of microenvironments in any population can be very large. Influences such as work conditions, neighborhood characteristics, housing quality, socio-economic status, ethnicities, schools, and life histories, can result in significant individual variations in infection risk and the likelihood of contracting resistant infections. Often, it is challenging to statistically characterize these diverse microenvironments. Even with disaggregated data, identifying sufficient high-quality covariates to mitigate infection risk heterogeneity’s distorting effects remains a formidable task, and it remains a confounding factor when interpreting statistical results from observational studies.

To demonstrate how heterogeneous infection and carriage risks by themselves can mimic aspects of the persistence phenomenon usually attributed to antibiotic use, we employ a simple counterfactual model devoid of biological persistence caused by antibiotic use. Antibiotics obviously do influence rates of antibiotic resistance and persistence. But to see what other factors might also have major effects, our model assumes that prior antibiotic use itself has strictly no effect on the development or persistence of resistant bacteria. This assumption means that prior antibiotic use is assumed to have no effect on either the future risks for any one individual or on general disease carriage rates in the population. This model assumption is adopted to show what other factors can also result in “persistence” of resistant bacteria in a population. Here, in each sub-population the circulating carriage rate or prevalence of resistant bacteria is due solely to local socioeconomic and environmental factors.

METHODS

Observational data are collected when individuals who are infected seek medical treatment and undergo testing. Imagine a population made up of two communities, A and B. In each period, individuals in Community A have a higher likelihood of becoming infected and, if infected, are more likely to have a resistant infection. Importantly, we assume for the sake of this model that there is no biological link between prior antibiotic use and the risk of antimicrobial resistance, either at the individual or community level. Additionally, the risk of infection for any individual is assumed to be constant in each time period.

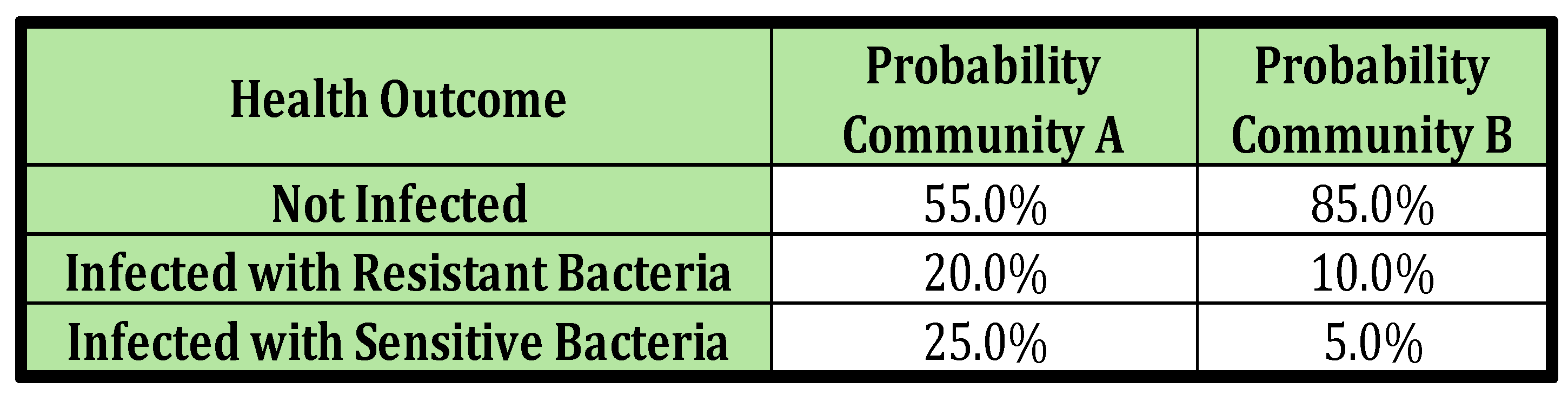

To make the discussion more tangible, we construct a numerical example. Suppose the two communities, A and B, make up 30% and 70% of the total population respectively. Additionally, assume that the infection risk profile of an individual in each community over the course of some arbitrary period of time (e.g. six months, or one year) aligns with what’s presented in

Table 1. The observational data are typically generated when those who are infected present themselves clinically for treatment. The insights generated in this paper arise from the implications of elementary probability calculations discussed with the Results.

RESULTS

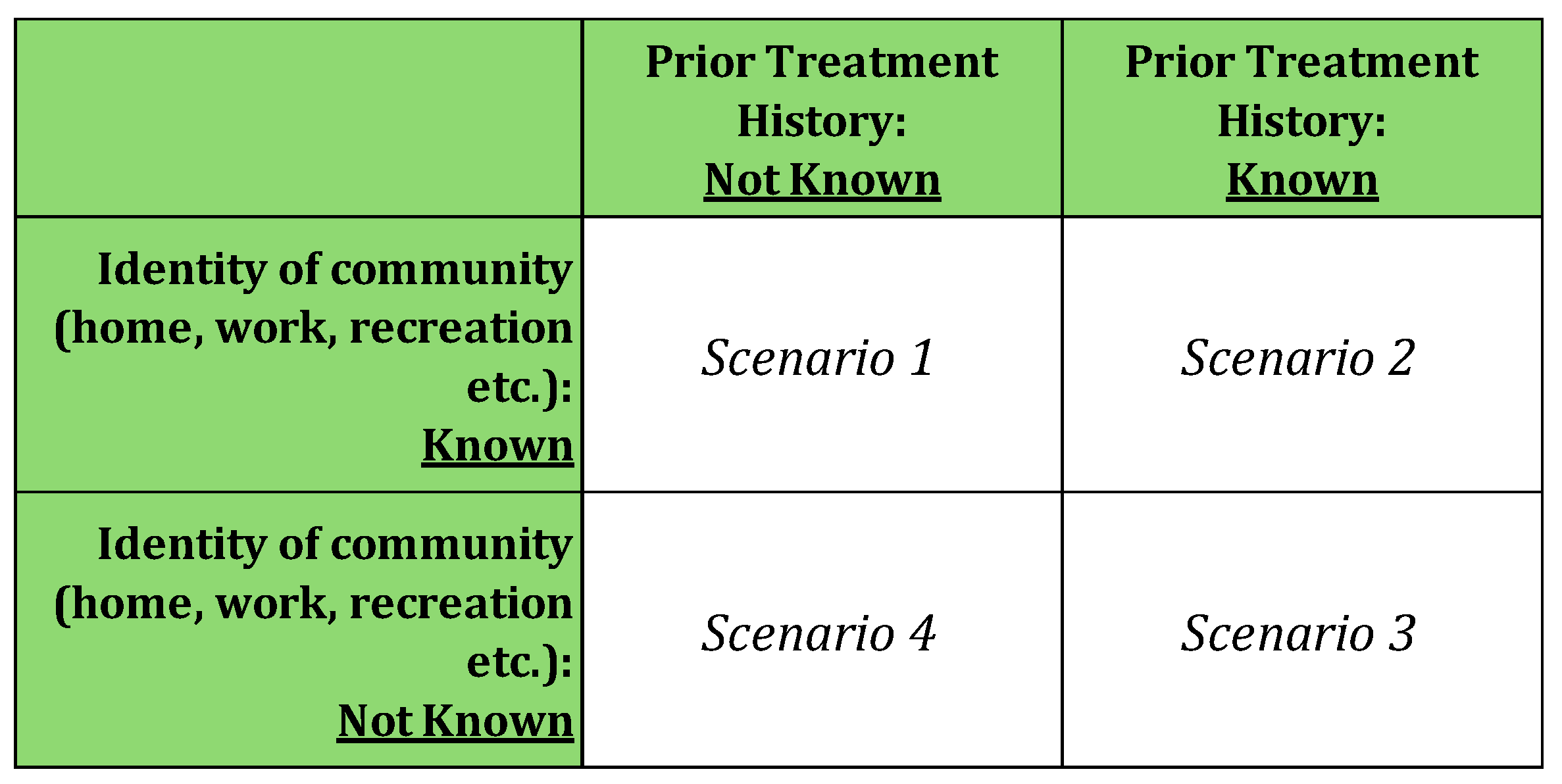

Here, we distinguish four scenarios that describe what might be known about the medical treatment history and community life of people presenting for treatment. These scenarios are shown in

Table 2. In clinical practice, what is known about a patient will usually be an amalgam of knowledge from different information sources, however, the simple categorization of scenarios here is useful to clarify the key insights of this paper. In clinical practice, a common scenario is likely to be one has some knowledge about the patient’s clinical history, and where the patient lives is known (e.g. house, apartment, community nursing home) although usually their total community life experience (interaction with others etc.), still won’t be known.

Scenario 1: The individual’s community identity is known, but their history of prior infection is not known. This is the most straightforward scenario, as the risk of infection remains constant in each period and solely depends on the community the individual belongs to. For instance, in our numerical example, if the individual is from Community A, the risk of any infection in each period is consistently (20%+25%) or 55%, and the risk of resistant infection is always 25%. For an individual from Community B, these risks are (10%+5%) or 20% and 5% respectively (as per

Table 1).

This corresponds to knowing patient is from a nursing home, but the patient comes with no medical history records

Scenario 2: The individual’s community identity is known, and their history of prior infection is known. The risk profiles of this scenario are identical to those in Scenario 1. Even if the clinician is aware of the individual’s prior infection history, it provides no additional information in our model, because by assumption we are modelling a case where there are no lasting biological effects of previous infection and treatment. Hence, there is no additional useful information contained in the clinical history of infection.

This corresponds to knowing a patient is from a nursing home and the patient comes with their medical history records including antibiotic and other drug therapy.

Scenario 3: Neither the individual’s community identity nor their history of prior infection is known. This scenario is slightly more complex than Scenario 1 in that health outcome probabilities can be calculated as the population-weighted average of the risks in each community. For instance, the probability of any infection is [0.3*(0.20+0.25) +0.7*(.10+.05)] or 24%, and the probability of a resistant infection is [0.30.25+0.7.05] or 11%.

This equates to an unconscious patent presenting to emergency with no known history or known place of residence.

Scenario 4: The individual’s community is unknown, but his or her clinical history of infection is known. Importantly, this scenario is analogous to clinical situations where the treating physician is unaware of the patient’s infection risks (here it is because the community membership is not known) but does have access to the patient’s medical case history. In terms of conventional statistical analysis, this corresponds to missing environmental covariates that identify the individual’s community, factors such as occupational exposure to infection risk, residential circumstances such as poor housing, details of travel to high-risk destinations, etc. Clinical history now becomes relevant because it implicitly contains information on a person’s community, and hence the underlying risk of resistant infection.

Scenario 4 corresponds to a patient where all their medical history is available but a sufficiently detailed biographical history of jobs, residences, travel etc. has not been collected either because of the patient’s unwillingness to supply such information.

The analysis that follows uses Scenario 4, the most clinically realistic of the four scenarios to use in our model to look at the effects if antibiotic use is excluded as having a persistent effect. Scenario 4 corresponds to having patients where all their medical history is available on file, but a sufficiently detailed demographic and biographical history of jobs, residences, travel, lifestyle, etc. is not collected either because of the cost of garnering and recording such detailed information, or because of patients’ unwillingness to supply such information. Even if much of this information was informally known by the clinician as a result of previous patient contact, such detailed information will be rarely if ever recorded in a usable form for ex post empirical statistical analysis by researchers studying the persistence issue.

The more recently a person was infected, the greater the chance that that person comes from the high-risk community. Thus, even when there is no biological dependence of future health outcomes upon prior outcomes, clinical history helps predict future outcomes, and that predictability declines with time since last infection and treatment. The upcoming numerical example is used to provide a concrete illustration of this phenomenon.

Over four time periods, with three possible outcomes in each period (Not Infected or Infected-Sensitive or Infected-Resistant), there are (3*3*3*3) =81 permutations of the possible sequences of health outcomes. The discussion that follows focuses on sequences having Infected-Resistant outcomes in the fourth period when outcomes in the prior three periods are known.

In the initial three periods, there are (3*3*3) =27 permutations of the possible sequences of health outcomes that can be observed. In each community, the probability of each sequence is calculated by multiplying together the risk of each outcome in the sequence. As an example of the calculation, the historical sequence (Not Infected, Infected-Resistant, Infected-Sensitive) occurs in community A with probability = 0.55 ∗ 0.25 ∗ 0.2 = 2.75%, and in Community B with probability = 0.85 ∗ 0.05 ∗ 0.10 = 4.25%.

In each community, the probability of any three-period sequence followed by Infected-Resistant in the fourth period is simply the probability of that prior sequence multiplied by the probability of Infected-Resistant. Continuing the example above, the probability of the sequence (Not Infected, Infected-Resistant, Infected-Sensitive) followed by Infected-Resistant in the fourth period in Community A is simply = 0.0275*0.25 = 0.687%, and in Community B it is =

Insights can be obtained by collecting sequences into meaningful groups. For instance, one grouping could be of all sequences of prior history where an individual experiences one each of Not Infected, Infected-Sensitive, and Infected-Resistant in the first three periods. There are six such sequences that make up that group (Not Infected, Infected-Sensitive, Infected Resistant Not Infected, Infected-Resistant, Infected-Sensitive, Not Infected, Infected-Resistant Infected-Sensitive, Infected-resistant, Not Infected Infected-Resistant, Infected-Sensitive, Not Infected Infected-Resistant, Not Infected, Infected-Sensitive).

Consider groupings of sequences that could occur in periods one to three where:

Sequences grouped by the number of times an individual has been Infected-Sensitive or Infected-Resistant in the first three periods.

Sequences grouped by the number of periods elapsed since the individual’s most recent infection.

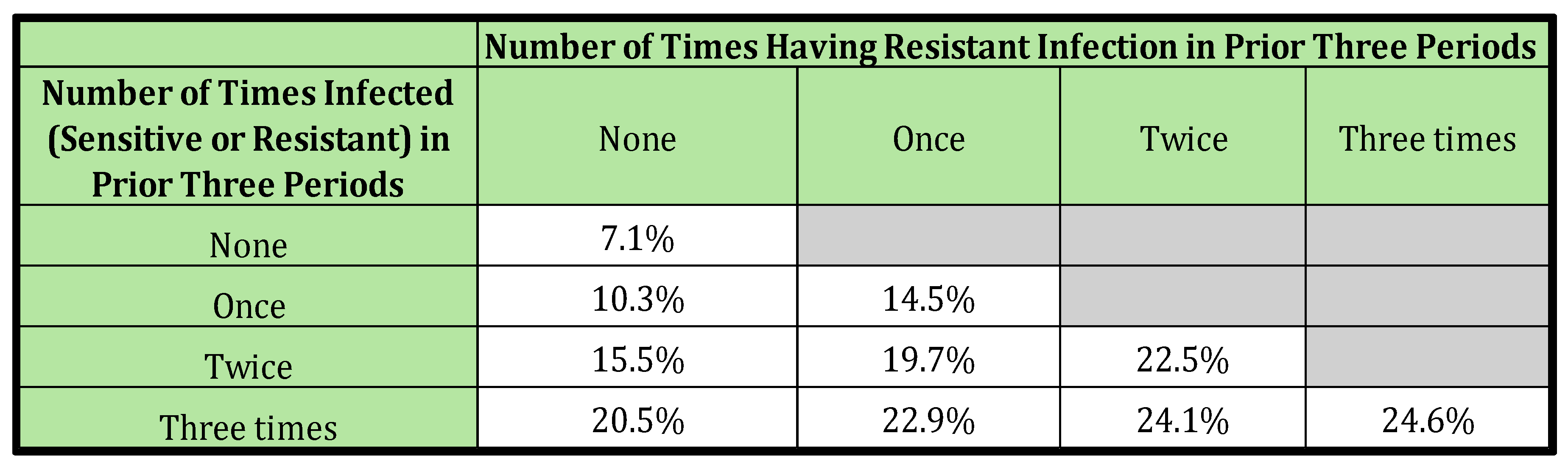

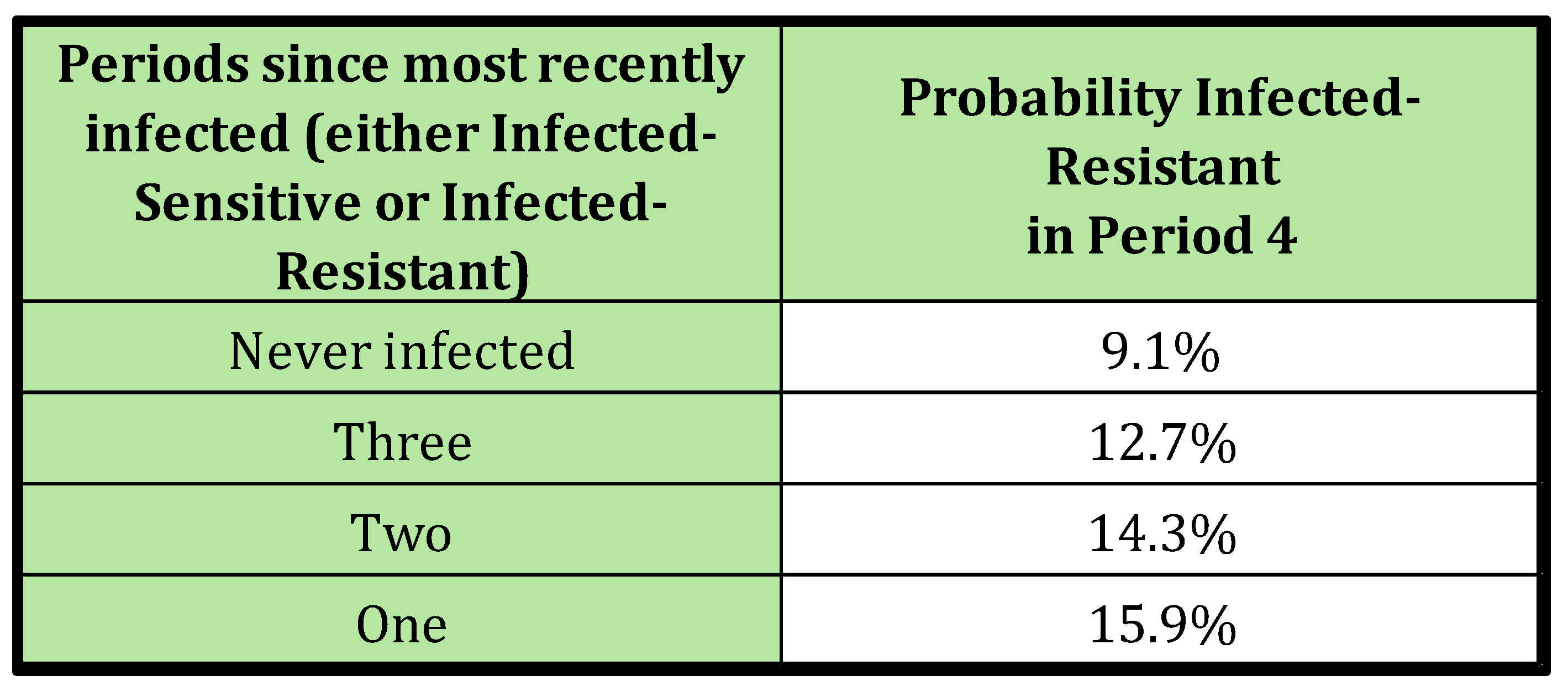

The conditional probability of health outcomes in the fourth period for the above grouping of sequences are presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4. Explanation of the calculation follows.

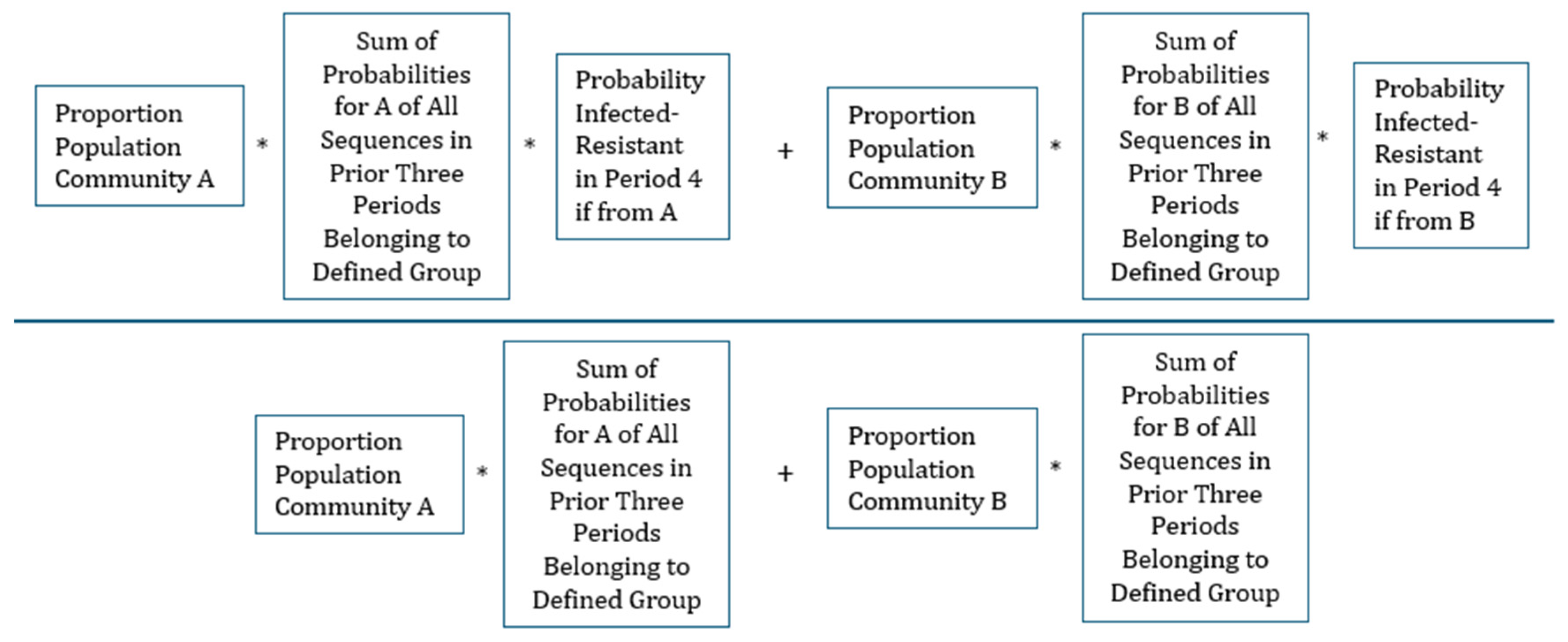

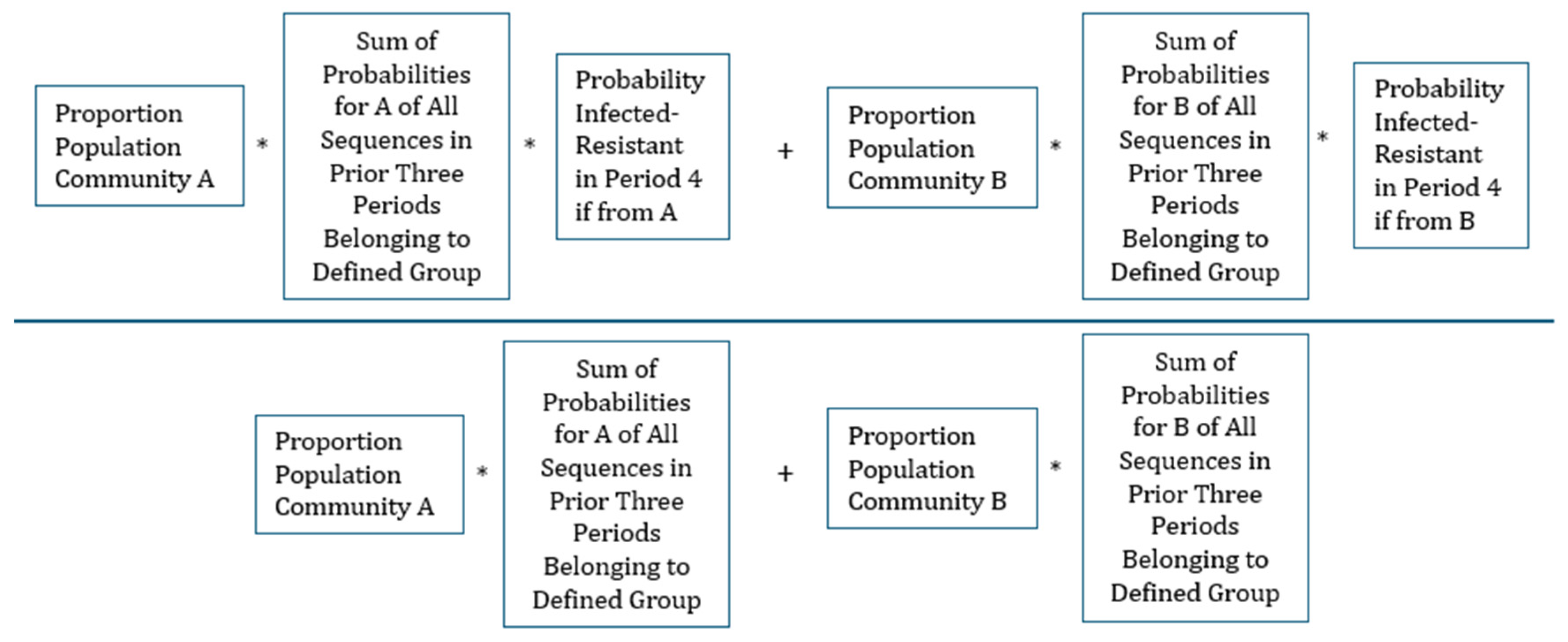

The conditional probability of being Infected-Resistant in the fourth period given one of the defined groups of prior clinical history can be calculated by familiar conditional probability formula (This equation is stated more formally in the Supplementary material).

Illustrating, the calculation with the example given above, there are six possible prior sequences (permutations) of prior history where a person can be Not Infected in only one period, Infected-Sensitive in only one period, and Infected-Resistant in only one period,

Table 3 and

Table 4 show the conditional probability of being Infected-Resistant in period four given different descriptions of a person’s clinical history in the preceding three periods.

Table 3.

Scenario 4; Probability Infected-Resistant in Period 4 Given History in Prior Three Periods.

Table 3.

Scenario 4; Probability Infected-Resistant in Period 4 Given History in Prior Three Periods.

Table 3 reveals that the probability of being infected by a resistant strain (Infected-Resistant) in period 4 is influenced by both the total number of past infections and the count of those infections that were resistant. This likelihood escalates with an increase in both these factors. This pattern emerges even though the underlying risk to any individual in either community is completely unrelated to their history. In this instance, what is mimicking the enduring biological effects of previous treatment is merely the fact that a clinical history of more infection means the individual is more likely to belong to the community with a higher infection risk, and if infected, also has an increased risk of resistant infection.

Table 4.

Scenario 4; Probability Infected-Resistant in Period 4 Given the Number of Periods Since Previous Infection.

Table 4.

Scenario 4; Probability Infected-Resistant in Period 4 Given the Number of Periods Since Previous Infection.

Table 4 illustrates that the likelihood of observing a resistant infection decreases as the time since the last infection increases. This trend mimics the pattern observed in biologically induced antimicrobial resistance, where the effect gradually diminishes as time passes since the individual’s last treatment. However, what appears to be a decline in persistence is merely a result of the fact that individuals with a longer interval since their last infection (and consequently, their last antimicrobial treatment) are more likely to originate from a community with a low risk of infection and resistance.

DISCUSSION

Antibiotic resistance is often associated with and therefore linked to antibiotic use [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. But this correlation may need not be all due to the direct effects of the antibiotics themselves. Our model shows that this same pattern can also be created by the conflating effects of unmodelled heterogeneity in the underlying risk factors. The paper shows how varying infection risks among individuals could explain the observed persistence of resistance, and where it’s not due to antibiotic use. Additionally, for purely statistical reasons the link between antibiotic use and resistance tends to weaken with time, related to the underlying subpopulations.

Well-designed statistical studies can reduce the impact of community heterogeneity on observed persistence by including variables that account for individual risks. Identifying variables that fully capture the diverse infection risks across communities is challenging, and as a result there may always be a tendency for past resistance to predict future resistance, independent of the biological effects of antibiotics.

Importantly, if the goal is only to inform clinical decisions before testing, the source of statistical persistence is less important. A model that predicts the degree of persistence is valuable, even without a biological link of antibiotic use and resistance.

However, when formulating antibiotic stewardship programs for empirical antibiotic use, it is crucial to recognize that the correlation between antibiotic use and resistance need not be due solely to antibiotic-induced changes in the microbiome. The heterogeneous spread and acquisition of resistant bacteria, or community “contagion”, is another significant factor that is easily overlooked. Unless research can confidently differentiate between (a) biological causes of persistence and (b) conflating statistical consequences of heterogenous infection risk in sub-populations, it is prudent when considering observational studies to be cautious when interpreting the role of past antibiotic use as the major factor in explaining observed rates of antibiotic resistance.

This may also explain why in many large population studies, the volumes of antibiotics used, or variations in their usage volumes, has had either no effect or only minor effects on the levels of associated antimicrobial resistance rates seen. Two studies looked at the impact of changes in antibiotic resistance rates or trends in

E. coli associated with decreases in antibiotic usage of a population [

15,

16] but no falls were seen in antibiotic resistance after reductions in antibiotic usage. In recent global studies, there was a poor correlation between antibiotic consumption and AMR levels [

9,

17]. In developed regions, such as Europe, a correlation with antibiotic usage was seen, this was not evident when using global data [

9]. The underlying socio-economic factors in countries or populations seem to have much higher impacts on resistance rates in comparison to antibiotic usage volumes [

9,

10].

Conclusion

This paper addresses one important aspect of the complex set of factors involved in understanding the persistence of antibiotic resistance. A simplified model was used for clarity, but that abstraction was not meant in any way to deny the biological consequences of antibiotic use. An effect of antibiotic use was left out of our model to show other factors are involved as well in both rates of resistance seen and in the persistence of resistant bacteria. It is certain that more realistic subsequent theoretical models, along with further empirical research, will shed more insights into the significance of the issue raised here.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization. JB and PC, Methodology including statistical analysis. JB.,Validation. JB and PC., Formal analysis. JB and PC., Writing first draft and preparation. JB.6, Writing, review and editing. JB and PC.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yelin I., Snitser O., et al. “Personal clinical History Predicts Antibiotic Resistance of Urinary Tract Infections”, Nature Medicine Vol 25 pp1143-1152 July 2019. [CrossRef]

- Markus Huemer 1, Srikanth Mairpady Shambat, Silvio D Brugger, Annelies S Zinkernagel “Antibiotic resistance and persistence-Implications for human health and treatment perspectives” Review EMBO Rep. 2020 Dec 3;21(12):e51034. Epub 2020 Dec 8. [CrossRef]

- Remy Chait 1 2, Adam C Palmer 1, Idan Yelin 3, Roy Kishony “Pervasive selection for and against antibiotic resistance in inhomogeneous multi-stress environments” Nat Commun 2016 Jan 20:7:10333. [CrossRef]

- Nasrin D, Collignon PJ, Roberts L, Wilson EJ, Pilotto LS, Douglas RM. Effect of beta lactam antibiotic use in children on pneumococcal resistance to penicillin: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2002 Jan 5;324(7328):28-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gefen O., Balaban N., “The importance of being persistent: heterogeneity of bacterial populations under antibiotic stress” FEMS Microbiol Review Vol 33, pp704-717, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Rahman S, Kesselheim AS, Hollis A. Persistence of resistance: a panel data analysis of the effect of antibiotic usage on the prevalence of resistance. J Antibiot. 2023;76:270-278. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy K, Collignon P. Colonisation with Escherichia coli resistant to "critically important" antibiotics: a high risk for international travellers. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29:1501-6. Epub 2010 Sep 12. [CrossRef]

- Nakayama T, Kumeda Y, Kawahara R, Yamamoto Y. Quantification and long-term carriage study of human extended-spectrum/AmpC β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli after international travel to Vietnam. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020 Jun;21:229-234. Epub 2019 Nov 11. [CrossRef]

- Collignon P, Beggs JJ, Walsh TR, et al. Anthropological and socioeconomic factors contributing to global antimicrobial resistance: a univariate and multivariable analysis. Lancet Planet Health. 2018;2:e398-e405. [CrossRef]

- Collignon P, Beggs JJ. Socioeconomic Enablers for Contagion: Factors Impelling the Antimicrobial Resistance Epidemic. Antibiotics. 2019;8:86. [CrossRef]

- Andersson D.I., Hughes D., “Persistence of antibiotic resistance in bacterial populations” FEMS Microbiol Review pp901-911, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Kuntz KM, Goldie SJ. “Assessing the sensitivity of decision-analytic results to unobserved markers of risk: defining the effects of heterogeneity bias” Med Decis Making. 2002;22:218–27. [CrossRef]

- Ewout W Steyerberg 1, Marinus J C Eijkemans Heterogeneity bias: the difference between adjusted and unadjusted effects Comment Med Decis Making. 2004 Jan-Feb;24(1):102-4. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Chen X, Guo Z, Zhao S, Huang Z, Zhuang Z, et al. Superspreading and heterogeneity in transmission of SARS, MERS, and COVID-19: A systematic review. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 2021;19:5039–5046. [CrossRef]

- Guthrie B, Hernandez-Santiago V, Davey PG, Nathwani D, Marwick CA. Changes in resistance among coliform bacteraemia associated with a primary care antimicrobial stewardship intervention: a population-based interrupted time series study. PLoS Med. 2019;16:1–19. [CrossRef]

- Aliabadi S, Anyanwu P, Beech E, et al. Effect of antibiotic stewardship interventions in primary care on antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli bacteraemia in England (2013–18): a quasi-experimental, ecological, data linkage study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;3099:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Hendriksen RS, Munk P, Njage P, et al. Global monitoring of antimicrobial resistance based on metagenomics analyses of urban sewage. Global Sewage Surveillance project consortium. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1124. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Assumed Prevalence of Health Outcomes in Each Period in Each Community.

Table 1.

Assumed Prevalence of Health Outcomes in Each Period in Each Community.

Table 2.

Information Known About the Patient: Four Scenarios.

Table 2.

Information Known About the Patient: Four Scenarios.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).