Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

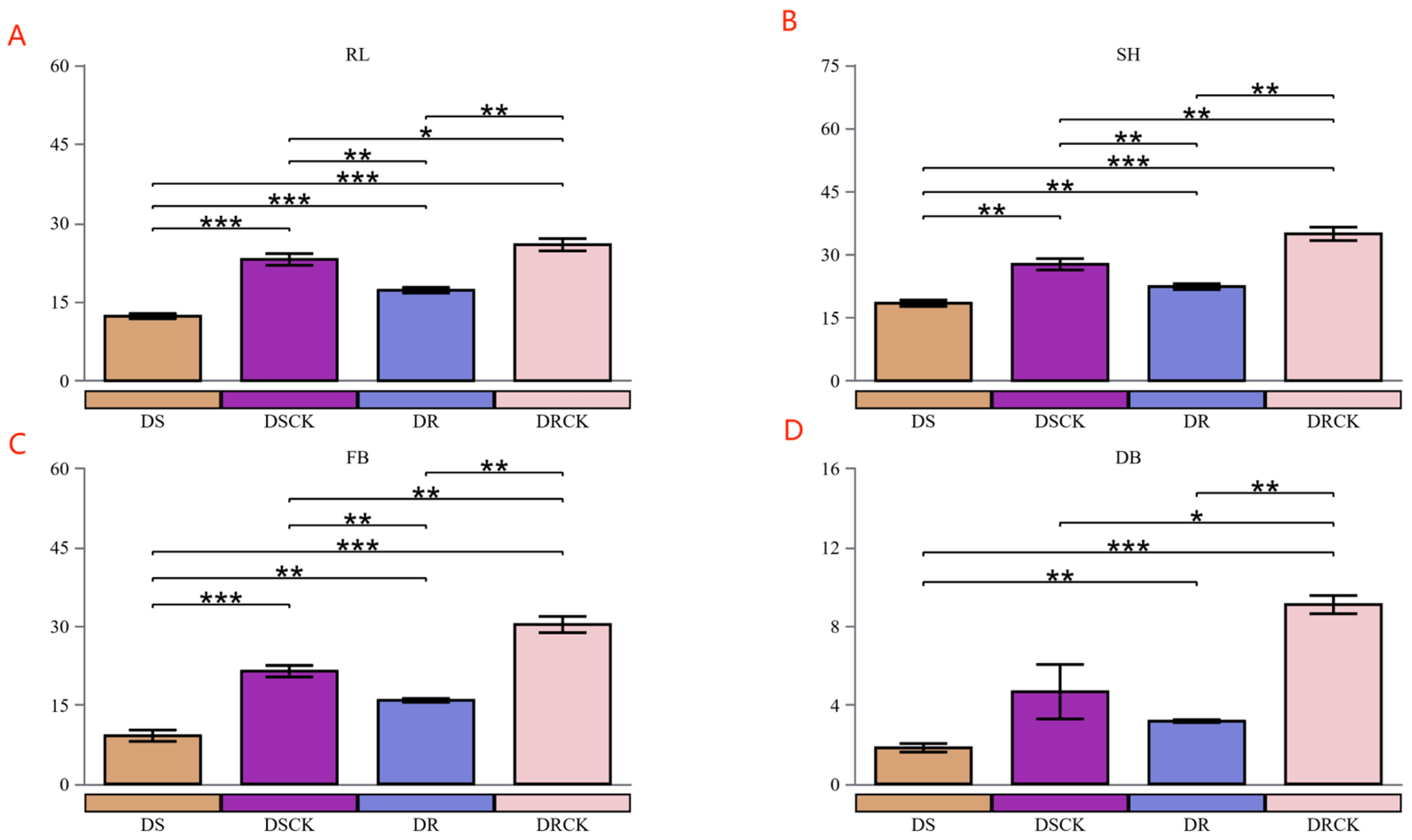

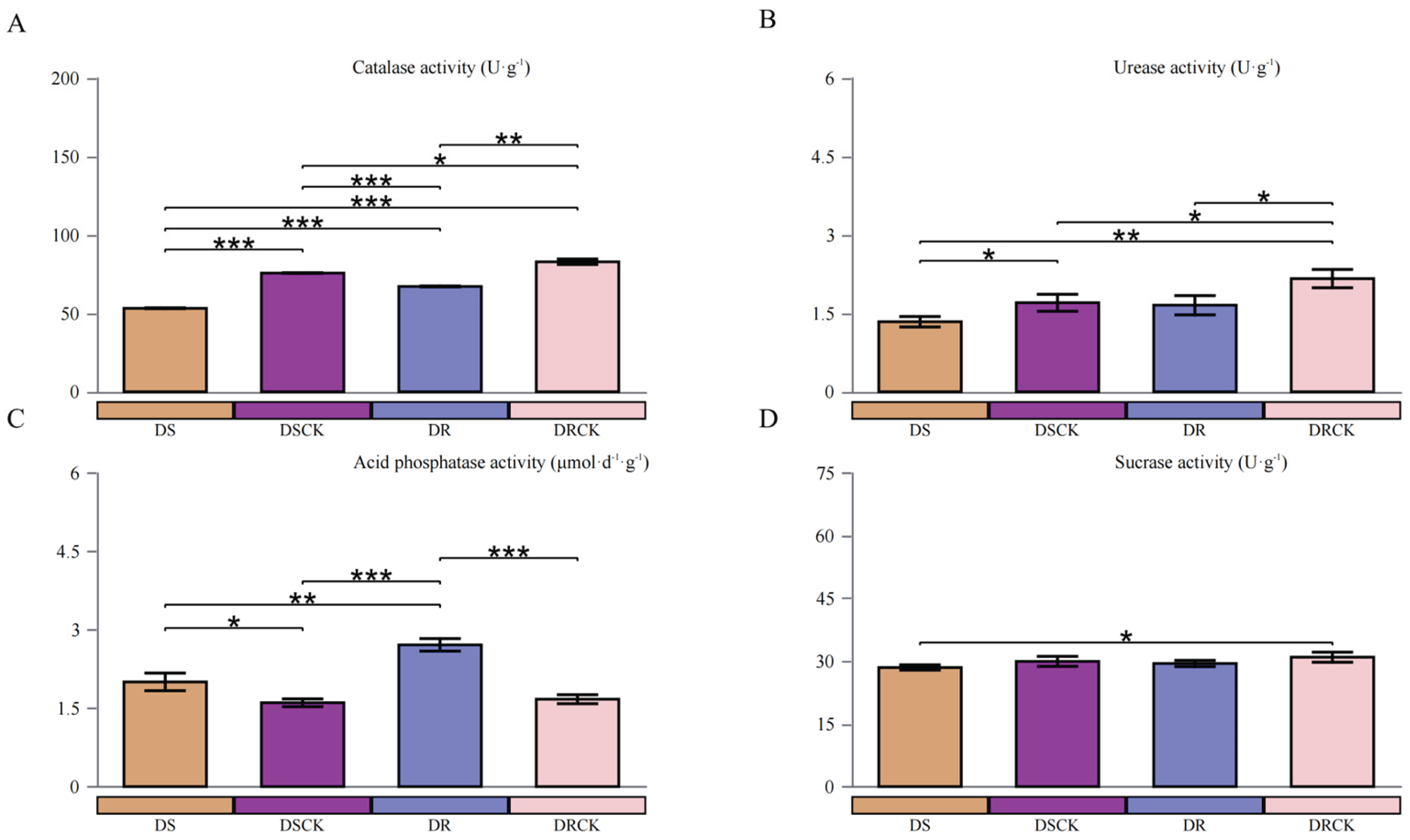

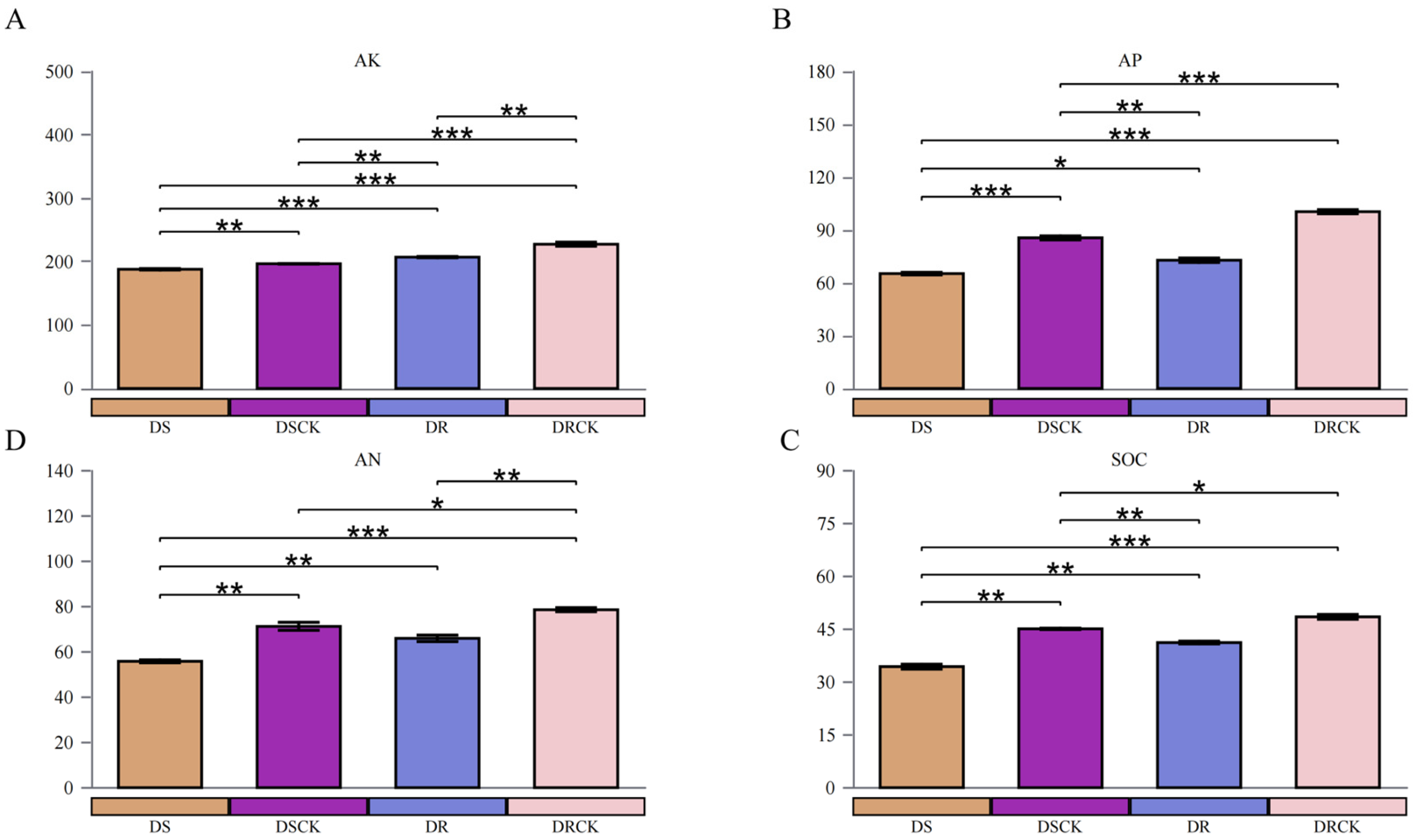

2.1. Variations in the Physicochemical Properties of Rhizosphere Soil and Physiological Indicators of Citrus Varieties under Drought Stress

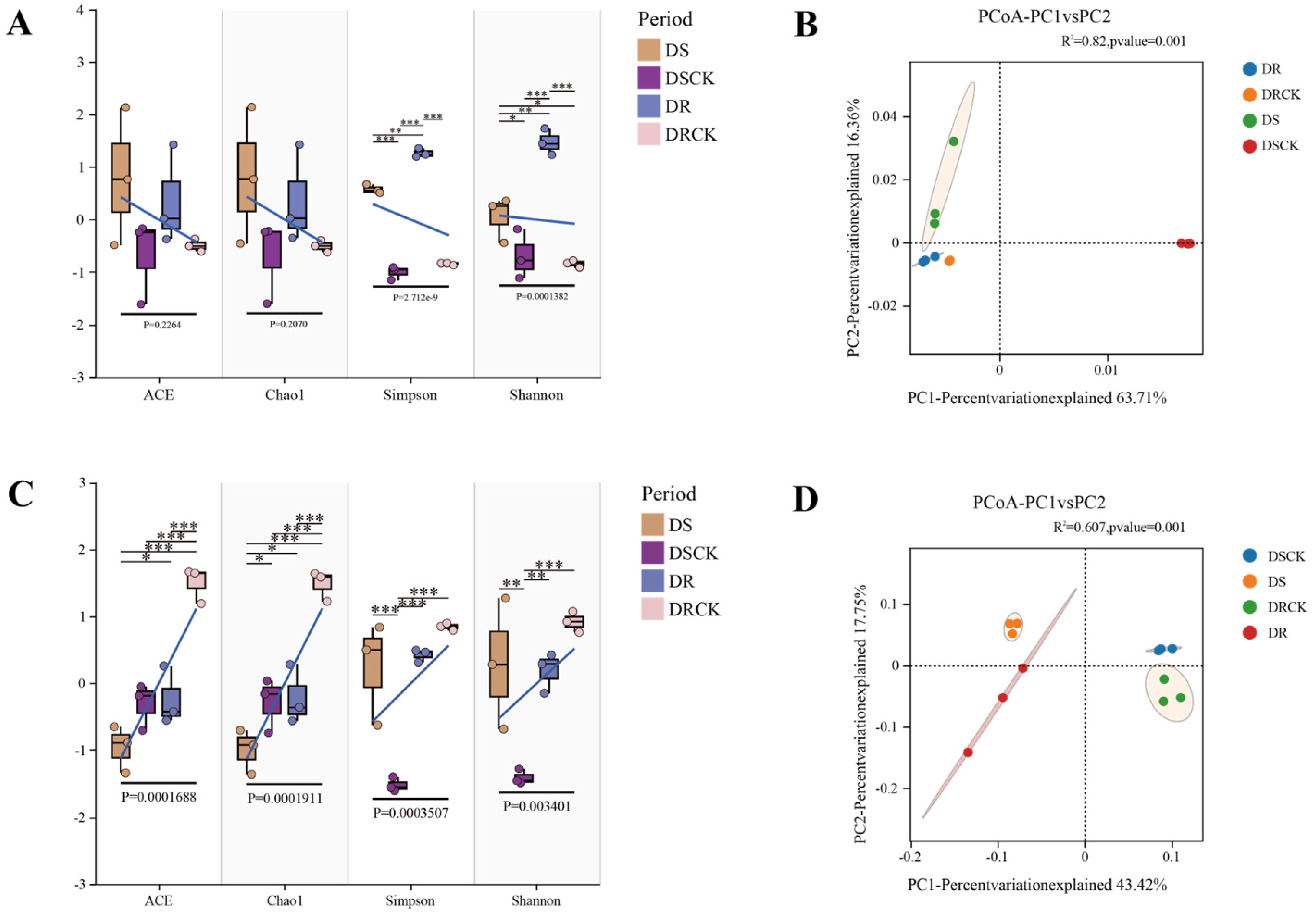

2.2. Diversity of Rhizosphere Microbial Communities of Different Citrus Under Drought Treatment

2.3. Functional Classification of Rhizosphere Microbial Communities

2.4. Correlation Analysis of Soil Characteristics and Microbial Community Structure and Co-Occurrence Network Analysis of Rhizosphere Microorganisms

3. Discussion

3.1. The Growth and Rhizosphere Microenvironment of Citrus With Different Genotypes Under Drought Stress

3.2. Drought - Induced Reorganization of Root Microbial Communities in Citrus with Different Genotypes

3.3. Functional shifts in the microbiome: From pathogen enrichment to strategic adaptation

3.4. Correlation Analysis and Network Complexity Reveal the Mechanisms of Different Drought Resistances

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cultivar Selection and Field Experiment Design

4.2. Measurement of Soil Chemical Properties and Determination of Soil Enzyme Activities

4.3. Soil Microbial DNA Extraction and High-Throughput Sequencing

4.4. Bioinformatic Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, X.; Zhu, X.; Pan, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y. Agricultural Drought Monitoring: Progress, Challenges, and Prospects. J. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 750–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Rico-Medina, A.; Caño-Delgado, A.I. The Physiology of Plant Responses to Drought. Science 2020, 368, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Tyagi, A.; Park, S.; Mir, R.A.; Mushtaq, M.; Bhat, B.; Mahmoudi, H.; Bae, H. Deciphering the Plant Microbiome to Improve Drought Tolerance: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2022, 201, 104933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M.; Hong, C.; Jiao, Y.; Hou, S.; Gao, H. Impacts of Drought on Photosynthesis in Major Food Crops and the Related Mechanisms of Plant Responses to Drought. Plants 2024, 13, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Lu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, S. Response Mechanism of Plants to Drought Stress. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, U.K.; Islam, M.N.; Siddiqui, M.N.; Cao, X.; Khan, M.A.R. Proline, a Multifaceted Signalling Molecule in Plant Responses to Abiotic Stress: Understanding the Physiological Mechanisms. Plant Biol J 2022, 24, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Li, D.; Ding, J.; Xiao, X.; Liang, Y. Microbial Coexistence in the Rhizosphere and the Promotion of Plant Stress Resistance: A Review. Environmental Research 2023, 222, 115298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, K.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Feng, F.; Cheng, J.; Ma, L.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, W.; et al. Rhizosphere Bacteria Help to Compensate for Pesticide-Induced Stress in Plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 12542–12553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Ali, S.; Shahid, M.A.; Mustafa, A.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Curá, J.A. Insights into the Interactions among Roots, Rhizosphere, and Rhizobacteria for Improving Plant Growth and Tolerance to Abiotic Stresses: A Review. Cells 2021, 10, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilla-Ermita, C.J.; Lewis, R.W.; Sullivan, T.S.; Hulbert, S.H. Wheat Genotype-Specific Recruitment of Rhizosphere Bacterial Microbiota under Controlled Environments. Frontiers in plant science 2021, 12, 718264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lu, J.; Li, X.; Qiu, Q.; Chen, J.; Yan, C. Effect of Rice (Oryza Sativa L.) Genotype on Yield: Evidence from Recruiting Spatially Consistent Rhizosphere Microbiome. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2021, 161, 108395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazcano, C.; Boyd, E.; Holmes, G.; Hewavitharana, S.; Pasulka, A.; Ivors, K. The Rhizosphere Microbiome Plays a Role in the Resistance to Soil-Borne Pathogens and Nutrient Uptake of Strawberry Cultivars under Field Conditions. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, F.; Feng, Z.; Yang, C.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Feng, H.; Zhu, H.; Xu, X. Genetic Control of Rhizosphere Microbiome of the Cotton Plants under Field Conditions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2024, 108, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastochkina, O.V. Adaptation and Tolerance of Wheat Plants to Drought Mediated by Natural Growth Regulators Bacillus Spp.: Mechanisms and Practical Importance. Agric. Biol 2021, 56, 843–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Singh, A.V. Multifarious Effect of ACC Deaminase and EPS Producing Pseudomonas Sp. and Serratia Marcescens to Augment Drought Stress Tolerance and Nutrient Status of Wheat. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2021, 37, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Vishvakarma, R.; Gautam, K.; Vimal, A.; Gaur, V.K.; Farooqui, A.; Varjani, S.; Younis, K. Valorization of Citrus Peel Waste for the Sustainable Production of Value-Added Products. Bioresource technology 2022, 351, 127064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziogas, V.; Tanou, G.; Morianou, G.; Kourgialas, N. Drought and Salinity in Citriculture: Optimal Practices to Alleviate Salinity and Water Stress. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.S.; Gan, Z.-M.; Li, E.-Q.; Ren, M.-K.; Hu, C.-G.; Zhang, J.-Z. Transcriptomic and Physiological Analysis Reveals Interplay between Salicylic Acid and Drought Stress in Citrus Tree Floral Initiation. Planta 2022, 255, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.; Liu, D.-H.; Alam, S.M.; Zaman, F.; Luo, Y.; Han, H.; Ateeq, M.; Liu, Y.-Z. Molecular Physiology for the Increase of Soluble Sugar Accumulation in Citrus Fruits under Drought Stress. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2023, 203, 108056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zeng, R.; Zhou, H.; Qiu, M.; Gan, Z.; Yang, Y.; Hu, S.; Zhou, J.; Hu, C.; Zhang, J. Citrus FRIGIDA Cooperates with Its Interaction Partner Dehydrin to Regulate Drought Tolerance. The Plant Journal 2022, 111, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafqat, W.; Jaskani, M.J.; Maqbool, R.; Chattha, W.S.; Ali, Z.; Naqvi, S.A.; Haider, M.S.; Khan, I.A.; Vincent, C.I. Heat Shock Protein and Aquaporin Expression Enhance Water Conserving Behavior of Citrus under Water Deficits and High Temperature Conditions. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2021, 181, 104270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devin, S.R.; Prudencio, Á.S.; Mahdavi, S.M.E.; Rubio, M.; Martínez-García, P.J.; Martínez-Gómez, P. Orchard Management and Incorporation of Biochemical and Molecular Strategies for Improving Drought Tolerance in Fruit Tree Crops. Plants 2023, 12, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gao, T.; Liu, C.; Mao, K.; Gong, X.; Li, C.; Ma, F. Fruit Crops Combating Drought: Physiological Responses and Regulatory Pathways. Plant Physiology 2023, 192, 1768–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Teng, Y.; Zheng, J.; Khan, A.K.; Li, X.; Cui, J.; Verma, K.K.; Guo, Q.; Zhu, K. The Impact of Long-Term Mulching Cultivation on Soil Quality, Microbial Community Structure, and Fruit Quality in" Wanzhou Red Mandarin" Citrus Orchard. Frontiers in Microbiology 2025, 16, 1616151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmos-Ruiz, R.; Hurtado-Navarro, M.; Pascual, J.A.; Carvajal, M. Mulching Techniques Impact on Soil Chemical and Biological Characteristics Affecting Physiology of Lemon Trees. Plant Soil 2025, 509, 809–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-Q.; Giri, B.; Wu, Q.-S.; Zou, Y.-N.; Kuča, K. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Mitigate Drought Stress in Citrus by Modulating Root Microenvironment. Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science 2022, 68, 1217–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.-J.; Wang, Y.; Alqahtani, M.D.; Wu, Q.-S. Positive Changes in Fruit Quality, Leaf Antioxidant Defense System, and Soil Fertility of Beni-Madonna Tangor Citrus (Citrus Nanko\times C. Amakusa) after Field AMF Inoculation. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Rico-Medina, A.; Caño-Delgado, A.I. The Physiology of Plant Responses to Drought. Science 2020, 368, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seleiman, M.F.; Al-Suhaibani, N.; Ali, N.; Akmal, M.; Alotaibi, M.; Refay, Y.; Dindaroglu, T.; Abdul-Wajid, H.H.; Battaglia, M.L. Drought Stress Impacts on Plants and Different Approaches to Alleviate Its Adverse Effects. Plants 2021, 10, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, A.; Sinha, R.; Singla-Pareek, S.L.; Pareek, A.; Singh, A.K. Shaping the Root System Architecture in Plants for Adaptation to Drought Stress. Physiologia Plantarum 2022, 174, e13651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshandeh, S.; Corneo, P.E.; Yin, L.; Dijkstra, F.A. Drought and Heat Stress Reduce Yield and Alter Carbon Rhizodeposition of Different Wheat Genotypes. J Agronomy Crop Science 2019, 205, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Ma, J.; Wen, T.; Niu, G.; Wei, S.; Su, S.; Yi, L.; Cheng, Y.; Yuan, J.; Zhao, X. Cry for Help from Rhizosphere Microbiomes and Self-Rescue Strategies Cooperatively Alleviate Drought Stress in Spring Wheat. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2025, 206, 109813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudent, M.; Dequiedt, S.; Sorin, C.; Girodet, S.; Nowak, V.; Duc, G.; Salon, C.; Maron, P. The Diversity of Soil Microbial Communities Matters When Legumes Face Drought. Plant Cell & Environment 2020, 43, 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogati, K.; Walczak, M. The Impact of Drought Stress on Soil Microbial Community, Enzyme Activities and Plants. Agronomy 2022, 12, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitkreuz, C.; Herzig, L.; Buscot, F.; Reitz, T.; Tarkka, M. Interactions between Soil Properties, Agricultural Management and Cultivar Type Drive Structural and Functional Adaptations of the Wheat Rhizosphere Microbiome to Drought. Environmental Microbiology 2021, 23, 5866–5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Xu, L.; Montoya, L.; Madera, M.; Hollingsworth, J.; Chen, L.; Purdom, E.; Singan, V.; Vogel, J.; Hutmacher, R.B. Co-Occurrence Networks Reveal More Complexity than Community Composition in Resistance and Resilience of Microbial Communities. Nature communications 2022, 13, 3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canarini, A.; Fuchslueger, L.; Schnecker, J.; Metze, D.; Nelson, D.B.; Kahmen, A.; Watzka, M.; Pötsch, E.M.; Schaumberger, A.; Bahn, M. Soil Fungi Remain Active and Invest in Storage Compounds during Drought Independent of Future Climate Conditions. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 10410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierre, E.; Fabiola, Y.N.; Vanessa, N.D.; Tobias, E.B.; Marie-Claire, T.; Diane, Y.Y.; Gilbert, G.T.; Louise, N.W.; Fabrice, F.B. The Co-Occurrence of Drought and Fusarium Solani f. Sp. Phaseoli Fs4 Infection Exacerbates the Fusarium Root Rot Symptoms in Common Bean (Phaseolus Vulgaris L.). Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 2023, 127, 102108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.; Irulappan, V.; Mohan-Raju, B.; Suganthi, A.; Senthil-Kumar, M. Impact of Drought Stress on Simultaneously Occurring Pathogen Infection in Field-Grown Chickpea. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Yang, K.; Cui, L.; Sun, A.-Q.; Lu, C.-Y.; Gao, J.-Q.; Hao, Y.-L.; Ma, B.; Hu, H.-W.; Singh, B.K. Global Exploration of Drought-Tolerant Bacteria in the Wheat Rhizosphere Reveals Microbiota Shifts and Functional Taxa Enhancing Plant Resilience. Nature Food 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudeletti, D.; Crusciol, C.A.C.; Bossolani, J.W.; Moretti, L.G.; Momesso, L.; Servaz Tubaña, B.; De Castro, S.G.Q.; De Oliveira, E.F.; Hungria, M. Trichoderma Asperellum Inoculation as a Tool for Attenuating Drought Stress in Sugarcane. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 645542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashyal, B.M.; Parmar, P.; Zaidi, N.W.; Aggarwal, R. Molecular Programming of Drought-Challenged Trichoderma Harzianum-Bioprimed Rice (Oryza Sativa L.). Frontiers in microbiology 2021, 12, 655165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Singh, R.; Madhu, G.S.; Singh, V.P. Seed Biopriming with Trichoderma Harzianum for Growth Promotion and Drought Tolerance in Rice (Oryza Sativus). Agric Res 2023, 12, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, S.; Schauster, A.; Liao, H.; Ruytinx, J. Mechanisms of Stress Tolerance and Their Effects on the Ecology and Evolution of Mycorrhizal Fungi. New Phytologist 2022, 235, 2158–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, R.A.; Corrêa, A.; Joshi, J.; Kaiser, C.; Lekberg, Y.; Prescott, C.E.; Sala, A.; Karst, J. What Determines Transfer of Carbon from Plants to Mycorrhizal Fungi? New Phytologist 2024, 244, 1199–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, S.D. Mycorrhizal Fungi as Mediators of Soil Organic Matter Dynamics. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2019, 50, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Chen, C.; Zhou, J.; Yuan, J.; Lu, M.; Qiu, J.; Xiao, Z.; Tan, X. Metagenomic and Metabolomic Profiling of Rhizosphere Microbiome Adaptation to Irrigation Gradients in Camellia Oil Trees. Industrial Crops and Products 2025, 232, 121250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veach, A.M.; Chen, H.; Yang, Z.K.; Labbe, A.D.; Engle, N.L.; Tschaplinski, T.J.; Schadt, C.W.; Cregger, M.A. Plant Hosts Modify Belowground Microbial Community Response to Extreme Drought. mSystems 2020, 5, 10.1128/msystems.00092-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Carrión, V.J. Importance of Bacteroidetes in Host–Microbe Interactions and Ecosystem Functioning. Trends in microbiology 2023, 31, 959–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambon, M.C.; Cartry, D.; Chancerel, E.; Ziegler, C.; Levionnois, S.; Coste, S.; Stahl, C.; Delzon, S.; Buée, M.; Burban, B.; et al. Drought Tolerance Traits in Neotropical Trees Correlate with the Composition of Phyllosphere Fungal Communities. Phytobiomes Journal 2023, 7, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Montoya, L.; Xu, L.; Madera, M.; Hollingsworth, J.; Purdom, E.; Singan, V.; Vogel, J.; Hutmacher, R.B.; Dahlberg, J.A. Fungal Community Assembly in Drought-Stressed Sorghum Shows Stochasticity, Selection, and Universal Ecological Dynamics. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.; Tang, J.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Han, S.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Chen, G.; Chen, L.; Zhu, T. Drought Stress-mediated Differences in Phyllosphere Microbiome and Associated Pathogen Resistance between Male and Female Poplars. The Plant Journal 2023, 115, 1100–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carezzano, M.E.; Paletti Rovey, M.F.; Cappellari, L. del R.; Gallarato, L.A.; Bogino, P.; Oliva, M. de las M.; Giordano, W. Biofilm-Forming Ability of Phytopathogenic Bacteria: A Review of Its Involvement in Plant Stress. Plants 2023, 12, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Huang, X.; Zhang, J.; Cai, Z.; Jiang, K.; Chang, Y. Deciphering the Relative Importance of Soil and Plant Traits on the Development of Rhizosphere Microbial Communities. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2020, 148, 107909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Liu, F.-C.; Yao, Y.; Zhu, C.-Y.; Yi, X.-C.; Chen, B.; Xiao, G.-L. Effects of Drought Stress on Rhizosphere Soil Bacterial Community of Potato throughout the Reproductive Period. 2023.

- Maisnam, P.; Jeffries, T.C.; Szejgis, J.; Bristol, D.; Singh, B.K.; Eldridge, D.J.; Horn, S.; Chieppa, J.; Nielsen, U.N. Severe Prolonged Drought Favours Stress-Tolerant Microbes in Australian Drylands. Microb Ecol 2023, 86, 3097–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Liu, Z.; Deng, Y.; Song, B.; Adams, J.M. Key Microbial Taxa Play Essential Roles in Maintaining Soil Muti-Nutrient Cycling Following an Extreme Drought Event in Ecological Buffer Zones along the Yangtze River. Frontiers in plant science 2024, 15, 1460462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walinga, I.; Kithome, M.; Novozamsky, I.; Houba, V.J.G.; Van Der Lee, J.J. Spectrophotometric Determination of Organic Carbon in Soil. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 1992, 23, 1935–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, D.S.; Brookes, P.C.; Powlson, D.S. Measuring Soil Microbial Biomass. Soil biology and biochemistry 2004, 36, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. UPARSE: Highly Accurate OTU Sequences from Microbial Amplicon Reads. Nature methods 2013, 10, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.; Beiko, R.G. 16S rRNA Gene Analysis with QIIME2. In Microbiome Analysis; Beiko, R.G., Hsiao, W., Parkinson, J., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2018; Vol. 1849, pp. 113–129 ISBN 978-1-4939-8726-9.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).