1. Introduction

The main reasons to admit a permanent electric field in the Milky Way Galaxy have been reported at the 37

held in Berlin in 2021, Germany [

1]. These reasons, arranged in a logical inference and based on experimental data, take advantage of the energy density of cosmic rays, about 1

/

, and the

applied to a system of charged particles. Cosmic nuclei are fully ionized atomic nuclei and globally form a huge system of charged particles extended up to the Galaxy radius of

m, 15

, and elevations above the Galactic midplane of 2

. Electrons are only 1.5 per cent of the cosmic-ray population at about 10

and still less electron fractions are observed at higher energies up to 1

[

2,

3] and above. Recently (2024), in Namibia, the HESS gamma-ray telescope observed an electron fraction of about 0.02 per cent of the proton flux at 40

.

This work, in order to redundantly prove the existence of the

, contrary to the previous one [

1], makes the opposite move: electric fields of simple charge configurations are reliably computed from

and, then, patiently connected to pertinent features of

cosmic rays measured by many experiments.

The two essential pertinent features are: (

) the position of cosmic-ray sources in spiral galaxies. The

is a spiral galaxy. Its radio emission and that from nearby spiral galaxies as well, particularly synchrotron emission, unambiguously determine the position of the sources (see, for example, ref. [

4,

5,

6]). Sources are located in molecular and atomic clouds and store the negative charge

(the subscript

w is for widow electrons). Orbital electrons lost by the accelerated cosmic-ray nuclei leaving the sources retain the negative charge

and are referred to as

. Cosmic-ray nuclei are fully stripped nuclei and transport the charge

(the subscript

cr is for cosmic rays) being,

= -

.

() Cosmic nuclei do have overwhelming kinetic energies in comparison to any sort of cosmic materials. These high energies enable cosmic-ray nuclei to propagate far away from the sources where they are generated. As a consequence, the motion of the nuclei creates a halo of positive electric charge around the negatively charged sources because cosmic-ray nuclei transport and disseminate only positive charge. In essence: halo size is larger than source size both structures storing the same opposite charge, = - and this spatial mismatch, ultimately, generates the Galactic electric field.

All cosmic-ray nuclei circulating in the

transport the total positive charge

in the range

-

C evaluated elsewhere [

1]. In order to easily intercompare the results of different calculations, the nominal charge

= -

=

C 1 is arbitrarily adopted lying in the range

-

[

1] and nominally and shortly set at

C. The total number of cosmic rays,

, circulating at a given instant in the

is about

≃

/

q =

/(

)×(1.21) =

where

q is the average electric charge per cosmic-ray nucleus and

=

from cosmic-ray data. Here

is an order of magnitude estimate.

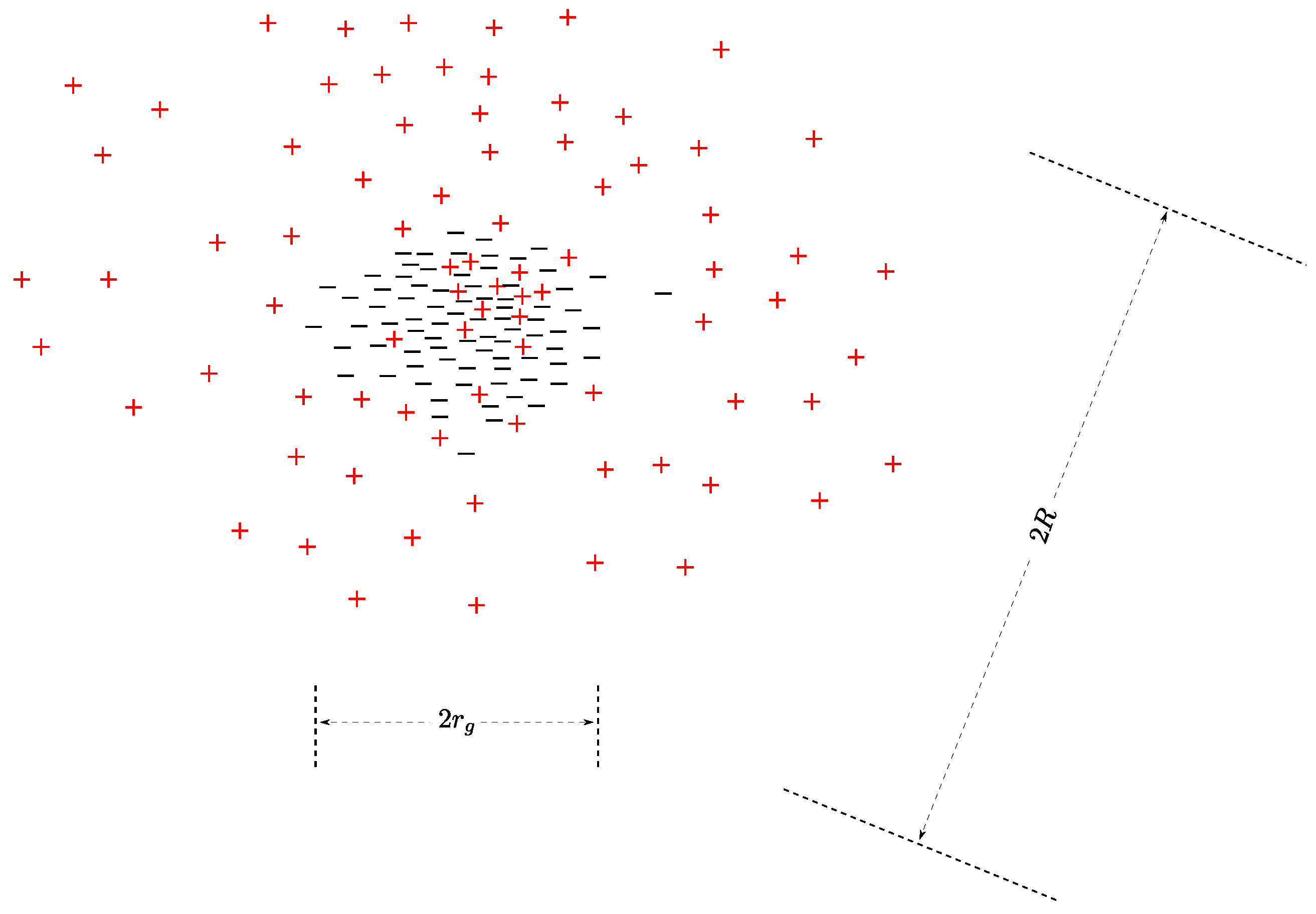

A highly schematic picture of the positions of the negative

and positive

charges in the arbitrary spherical volume of galactic size is in

Figure 1. This picture reflects the facts

and

in the sense that the negative charge occupies the central region while the positive charge lies peripherally.

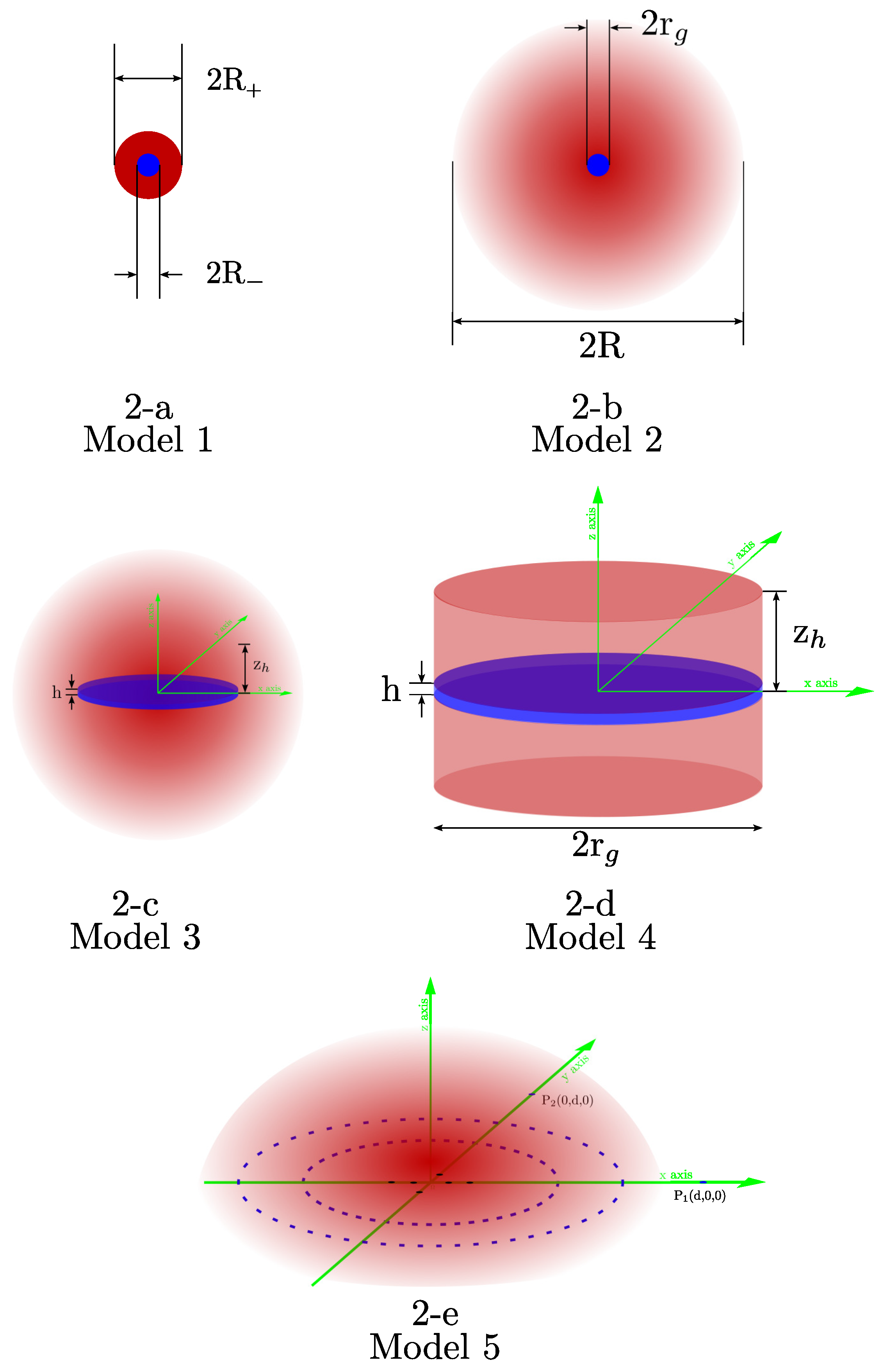

Five diverse charge configurations (

Figure 2) are examined in this study, all with total zero charge, namely,

= -

. The simplest charge configuration is the double, concentric spheres with constant charge density shown in

Figure 2-a (

Section 2). The second configuration (

Section 3) consists of two concentric spheres: a uniformly negatively charged sphere surrounded by positively charged spherical halo with decreasing density from the center (

Figure 2-b).

The third configuration (

Section 4) derives from the second one: the internal sphere storing the negative charge

is replaced by a flat disk of volume

2

h where

h is the half thickness of the disk and

its radius (

Figure 2-c).

The fourth configuration (

Figure 2-d and

Section 5) has no spherical form : it consists of two highly squashed, concentric cylinders with the same radius and different heights,

h and

(

h for halo of positive charge). The fifth configuration (

Figure 2-e and

Section 6) consists of six discrete negative pointlike charges constrained by the charge equality

= -

=

C and a size of about 15

. The number of six charges is thoroughly arbitrary but uncritical. A positively charged halo with decreasing charge density from the center (

Figure 2-e) completes the structure.

Why the

electric field cannot be dissolved in time and space is dealt with in

Section 7.

,

and

closes this study (

Section 8) highlighting its empirical basis.

2. The Electric Field Of Two Concentric

Uniformly Charged Spheres

Imagine a sphere of radius

with negative electric charge

uniformly distributed over its volume. The intensity of the electric field

(

r) is straightforwardly determined from elementary

:

where

=

F/

m and

=

/ (4/3)

is the negative charge density in the sphere. Equation (1-a) applies in the range

r≤

while (1-b) in

r≥

. Here, of course, it is

=

= -

C.

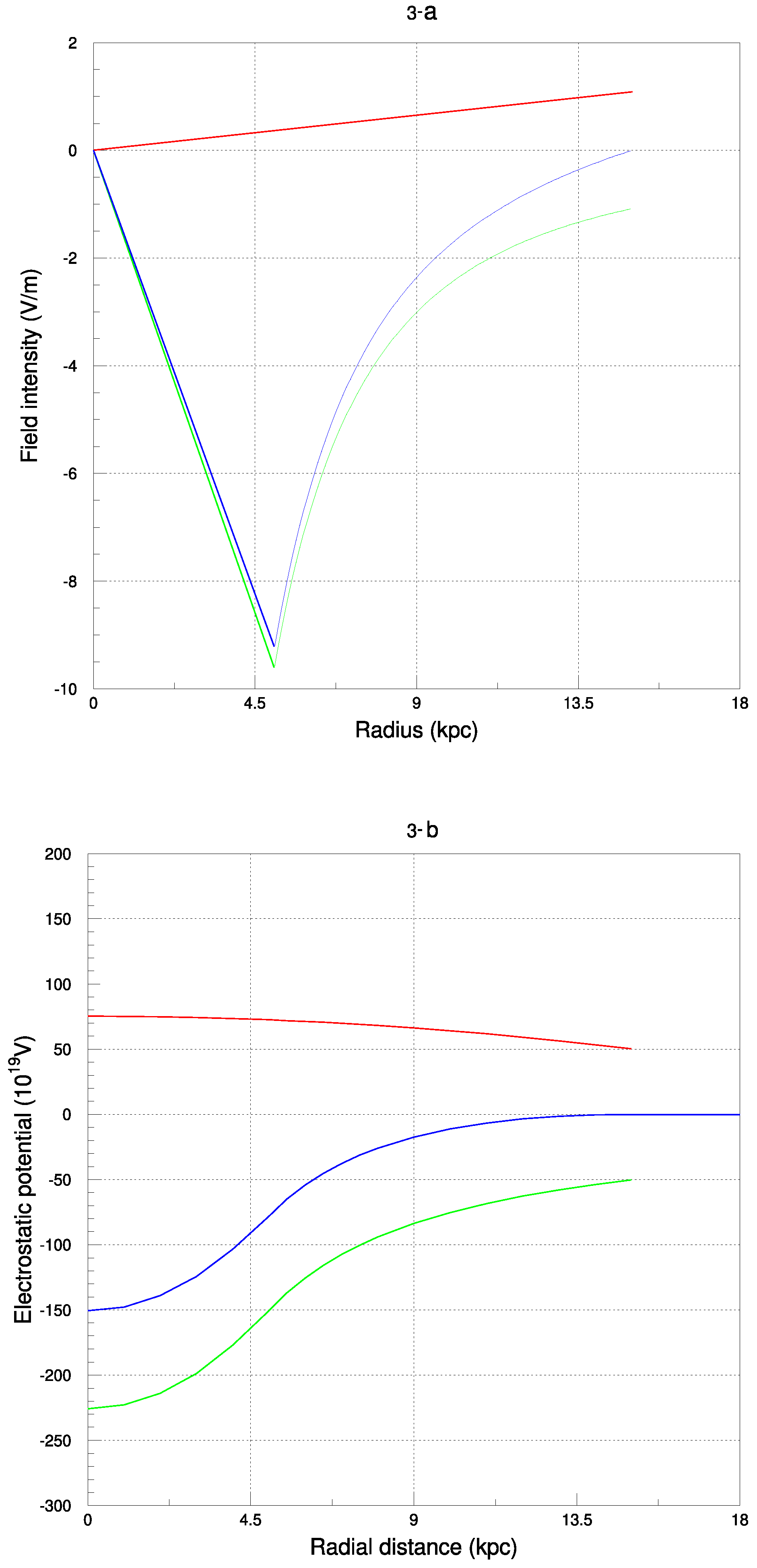

Due to the spherical symmetry, the field intensity

(

r) is zero at the center, then, it augments with increasing radial distance

r according to (1-a) up to the sphere radius

as displayed in

Figure 3-a. At radial distance r ≥

the field strength decreases as 1/

as it is well known.

Consider further a second sphere of radius of positive electric charge and density = / (4/3) concentric to the sphere of radius . The corresponding electric field (r) has expressions analogous to those (1-a) and (1-b) except for the positive charge sign, and .

The total field E(r) is the sum of two components: E(r)= r) + r) at any distance r from the sphere center. If = - and = the field strength is, of course, null everywhere. Whenever a slight offset in the positive and negative charge distributions occurs, a finite electric field sets on inside the sphere.

For example, the arbitrary parameters,

= 5

,

= 3

= 15

,

= -

=

C yield charge densities

= -

C/

,

=

C/

and field intensities

(15

) = 1.0819

V/

m and

(5

) = -

V/

m, respectively. The radial profile of the total electric field,

E(

r), is shown in

Figure 3-

a (blue curve) along with

(

r) (red curve) and

(

r) (green curve). The field vanishes beyond

= 3

= 15

as shown in same figure.

The potential for the negative charge

reads:

Equation (2-a) applies in the interval r ≤ while (2-b) in r≥. Analogous equations hold for the positive charge .

This is the simplest conceivable charge configuration with a vague kinship to cosmic-ray data. The vague kinship are facts

and

(

Section 1), namely, the negative charge predominates in the core of the spherical volume while the positive charge in the periphery.

3. Two Concentric Spheres With Unequal Profiles Of Charge Densities

A step forward from the previous charge configuration toward physical reality is the removal of the uniform charge distribution of the positive charged halo of the cosmic-ray nuclei.

The displacement of cosmic-ray nuclei from the sources of finite size produces a charge density

2 featured by 1/

r where

r is the distance from the source up to a characteristic distance

R. The simple behavior 1/

r is in the radial interval

r<

R. Accordingly, the positive electric charge density per unitary volume,

(

r), reads:

where

k is a constant. From elementary

the electric field intensity

(

r) generated by the charge distribution (3) is constant, directed outwardly and it is:

where

is the total positive electric charge transported by cosmic rays and

the characteristic distance of the propagation. For example, with

=

C and

R = 300

, at any arbitrary radial distance satisfying,

, it turns out:

=

V/

m.

As cosmic-ray sources of this

2 retain a total negative electric charge,

=

having spherical symmetry of diameter 2

, in a generic point

r such that

, the intensity of the resulting electric field

E(

r) is:

where

/

is the field strength of the negative charge only, designated by

(

r). Because of the postulated spherical symmetries of the positive and negative charge distributions and the common origin

, the electric field

(

r) vanishes beyond the distance

R.

Inside the sphere, 0 ≤

r≤

, the field intensity

is:

/ 4

similarly to Equation (

1). Accordingly:

which coincides with the outer field given by Equation (5) at the point

r =

= 15

. Hence, the electric field intensity

E(

r) for

r<

R is always less than

(

r) by the constant amount

=

/ 4

. The profile of

E(

r) versus radius is shown in

Figure 4. For example at the distance

r =

= 15

it turns out,

(

) =

V/

m, which is about 400 times greater than

(

r) of Equation (

6) with

R = 300

. For any other distances

r<

the ratio

(

r)/

(

r) decreases.

In the region, 0 ≤r≤ = 15 of the spherical volume (4/3) = , the mean energy of the electrostatic field given by equation (5) is and, accordingly the mean electrostatic energy density is /.

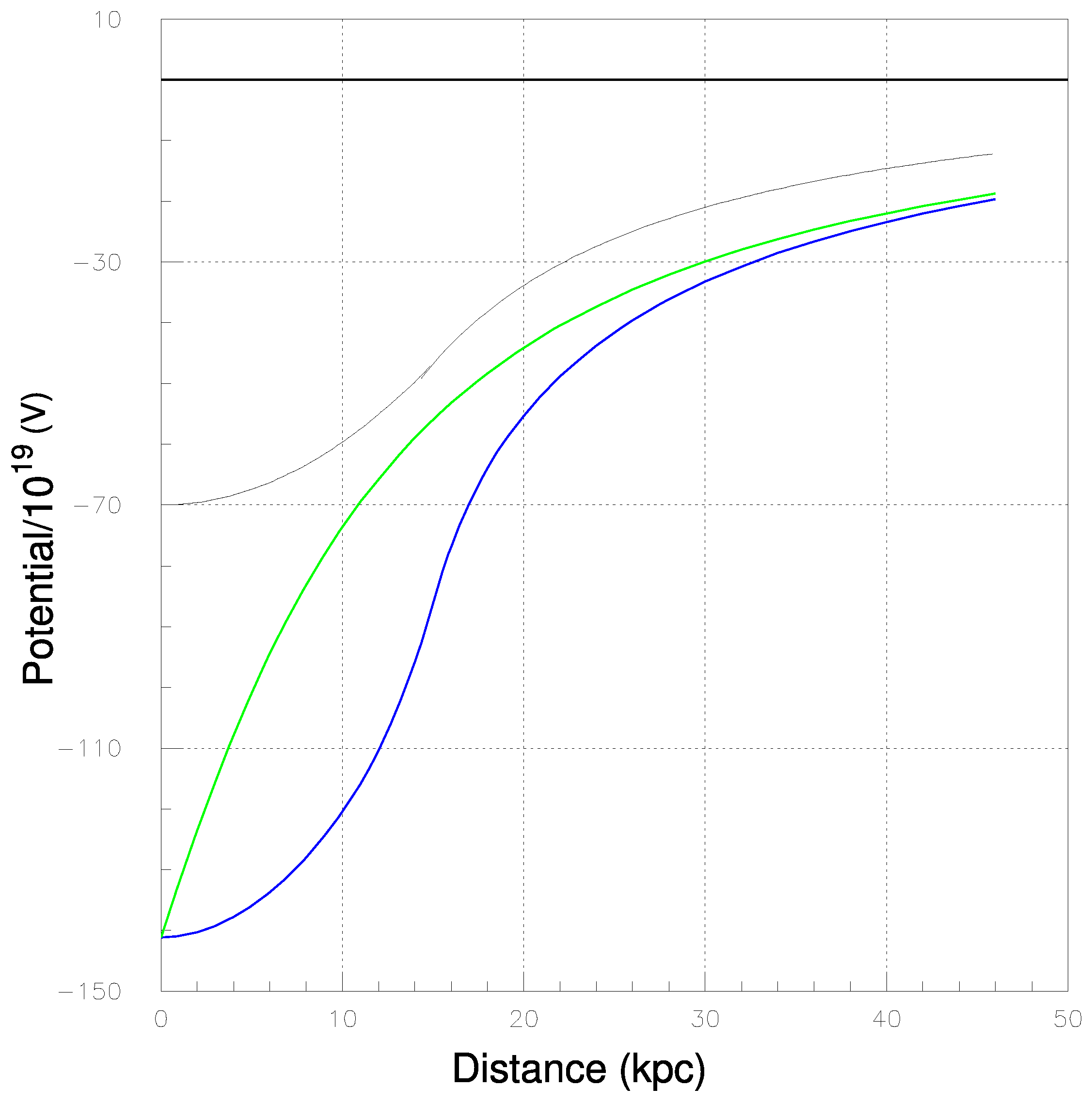

The radial profile of the electrostatic potential related to the electric field represented by Equation (5) and (6) , in the same conditions specified above, setting

D≡

/4

=

V takes the form:

Equation (7-a) holds for

while the (7-b) for

.

Figure 5 shows the profile of the potential (black curve) in the range,

for

= 15

and

n = 20 being

n =

R/

. The classical normalization condition of zero electrostatic potential at very large distances has been adopted.

4. A Positively Charged Sphere Concentric To A Negatively Charged Disk

Sources of cosmic rays in the

Milky Way Galaxy like other nearby spiral galaxies are distributed on a thin disk. This fact is proved by redundant evidence via radio, infrared and optical emission from

regions, molecular clouds and neutral Hydrogen clouds as recapitulated in

Section 1 by the fact

. As a consequence, a thin disk, instead of a sphere, better adheres to the spatial dissemination of the cosmic-ray sources.

An artistic view of this charge configuration (

3) is delineated in

Figure 2-c.

The negative charge

has a cylindrical symmetry and, therefore, the electric field and potential have two components: radial

r and elevation

z (

Figure 2-

c).

Consider a disk of center

, radius

and thickness 2

h with

= 15000

and

h=125

. Let the negative charge

= -

C be uniformly distributed inside the disk volume, and assume further, that the positive charge of the cosmic rays (positively charged nuclei) diminishes in the whole space as

k/

r following equation (3) up to the maximum distance from the center

R. Here

r is the generic distance from the center

and

k a suitable constant. The calculation adopts,

R = 300

,

k = -

/2

= -

C/

and a total positive charge

equal to that of widow electrons,

. This geometrical form with the negative electric charge

enshrouded by the charged cocoon of cosmic nuclei

would imitate the electrostatic structure of a common disk galaxy like the

Milky Way Galaxy or

better than the concentric double sphere with zero charge previously examined (

2 in

Section 3).

The function k/r is equal to that of the crude surrogate of the spherical galaxy expressed by Equation (3) and it produces a constant electric field intensity of V/m if = C and R = 300 , always directed outwardly, as previously remarked.

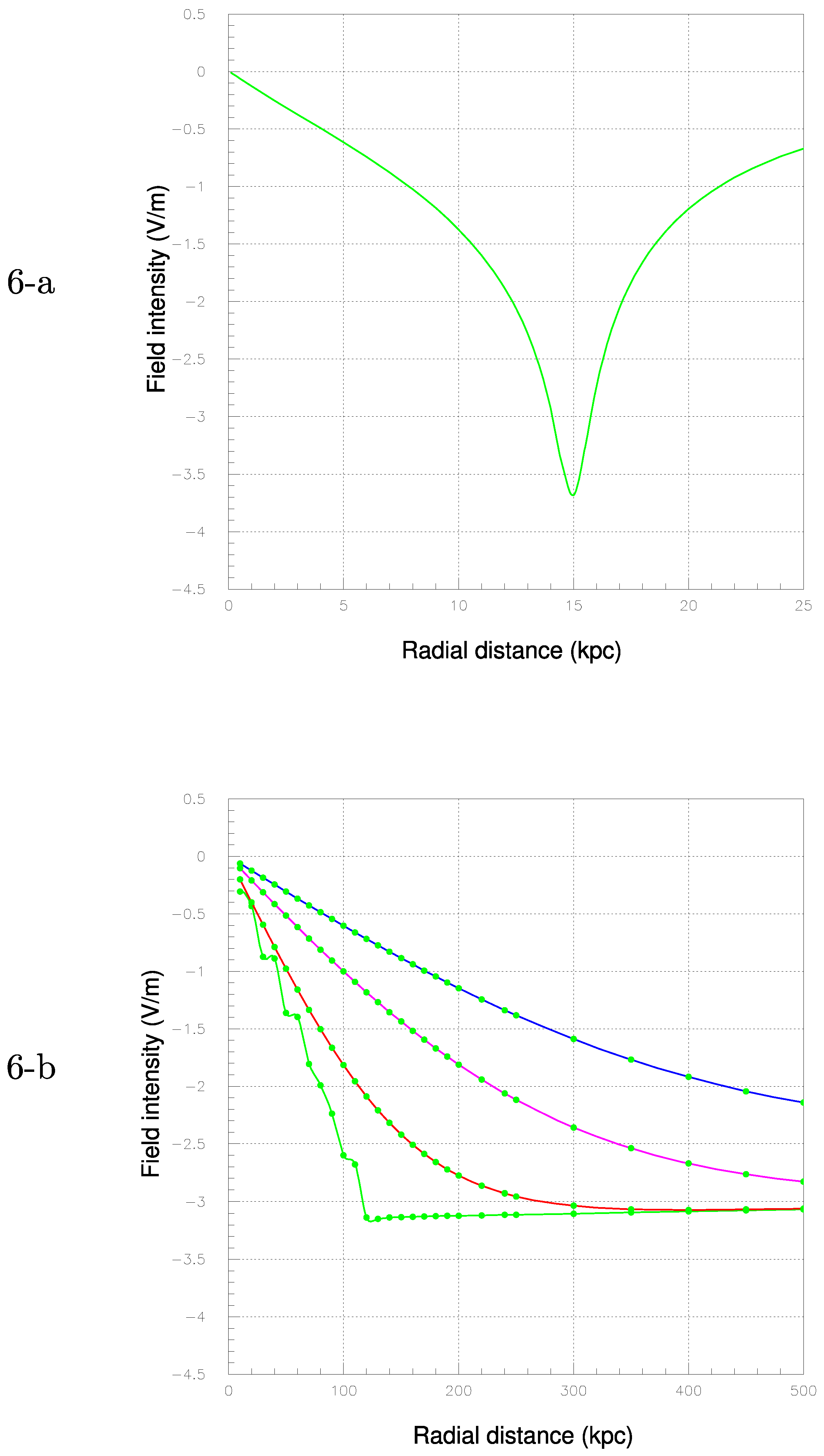

The electric field of this structure denoted by

can be decomposed in a radial and vertical (also elevation

z) components,

and

, respectively, in such a way that:

=

+

. The intensity

versus radius

r up to 25

is shown in

Figure 6-

a. As it is quickly realized, in the range 0 <

r<

the field profile turns out to be concave relative to a linear trend (for instance the trends represented in

Figure 3-

a and 4 in the radial range 0 <

r< 15

). Thus, the field strength

vanishes at the origin

and takes the maximum value of - 3.7

V/

m on the rim e. g.

r =

= 15

.

The intensity

versus elevation

z at the four arbitrary radii

r = 0,

r=

,

r =

and

r =

are shown in

Figure 6-

b. The

profile for

r = 0 (green curve) joins the profile in

Figure 6-

a (green curve) in the range

<

r< 250

and completes it. For

r = 0 the

field strength attains its maximum of 3.38

V/

m at elevations

z above 125

. As expected for an ideal, infinite uniformly charged slab, the field strength

is almost constant close to the slab (highly flat cylinder in the present case) even with a finite slab.

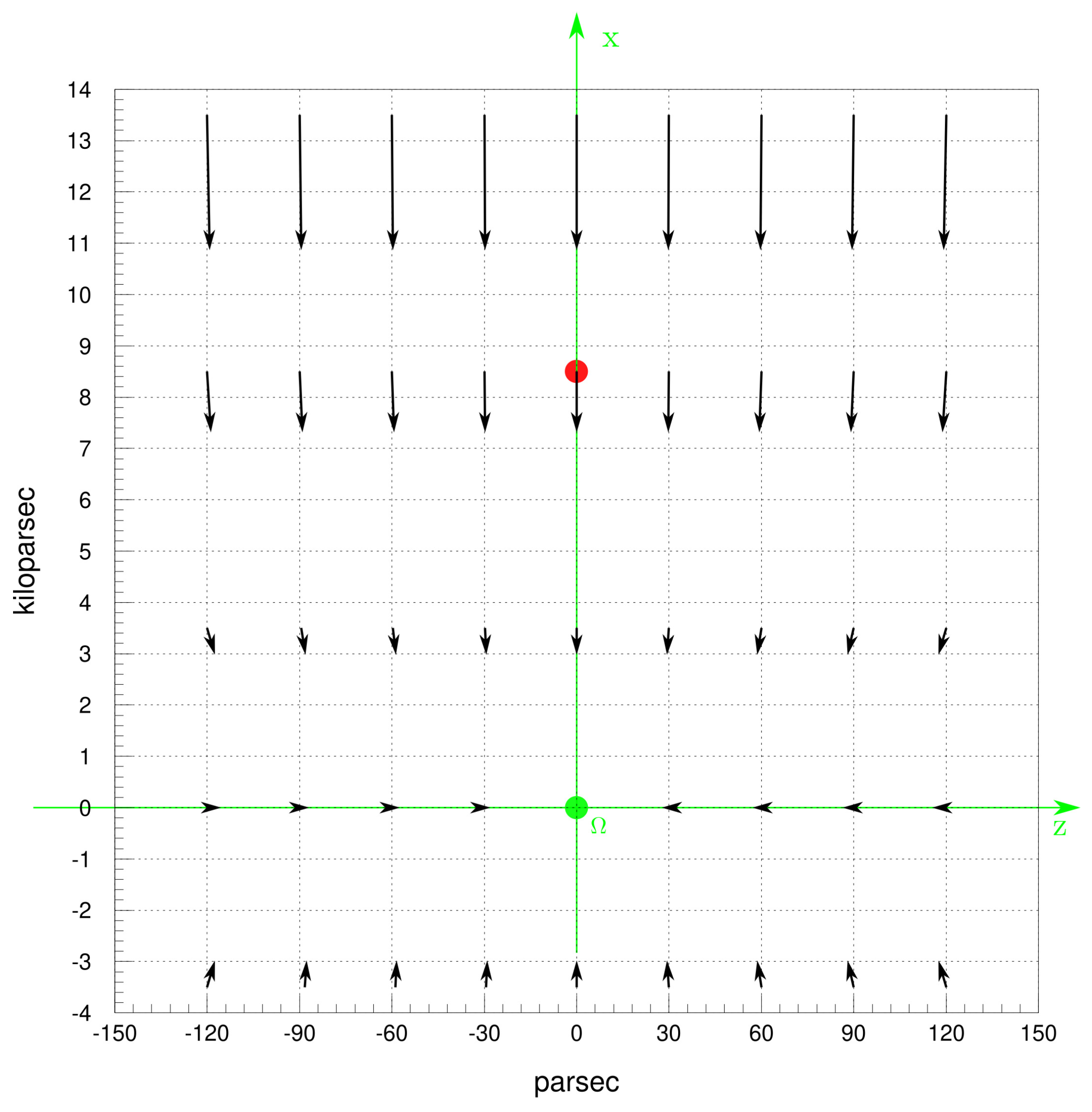

Assimilating the

Milky Way Galaxy to this structure (

3), in the nominal position of the solar system, i. e.

r =

and

z = 0 it is:

=

V/

m. The electric field

inside the disk, around the solar system (

r =

and

z = 0) in the plane

xz normal to the Galactic midplane

xy is visualized by the vector array in

Figure 7. Note that the unit length in the

x and

z axes differ by a factor 80.

The electric field of

3 has an approximate spherical symmetry in regions far away from the center and imitates the spherical symmetry of the double sphere with zero charge (

2 in

Section 3). For example, in the position

z = 400

and

r = 0 it results,

=

V/

m while for

r = 400

and

z = 0 it results:

=

V/

m so that:

-

=

V/

m. Given the smallness of this difference it turns out that at large distance from the center

the field strength

is almost independent from the direction.

5. Two Concentric Squashed Cylinders With Positive And Negative Charge

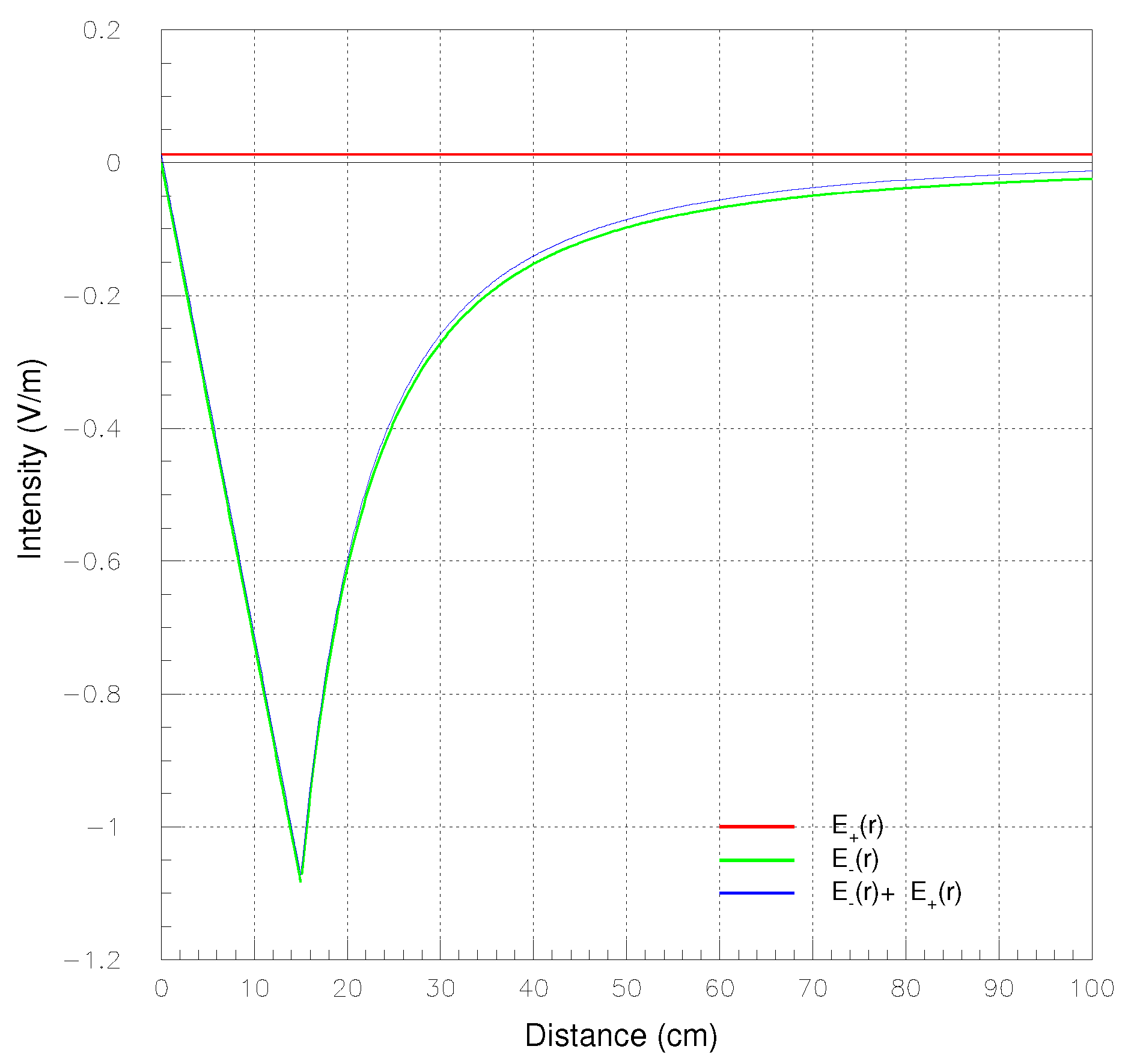

In 4 the electrostatic field (r,z) results from the sum of the fields of two separate single disks which are denoted by (r,z) for the charge and (r,z) for the charge being = + . For sake of simplicity,

two uniform charge distributions in the two volumes 2h (disk) and 2 (halo) are used in the calculation having, respectively, charge densities = C/ and = C/.

To begin with, the field strength E(r,0) along the radial direction for z = 0, and E(0,z) along the z axis for r = 0 are calculated. The x axis is chosen as generic radial direction. This choice does not lack of generality as the field (r,z) has cylindrical symmetry. These two field profiles, to be evaluated along two particular directions, facilitate the description of (r,z) at any space point inside and outside the .

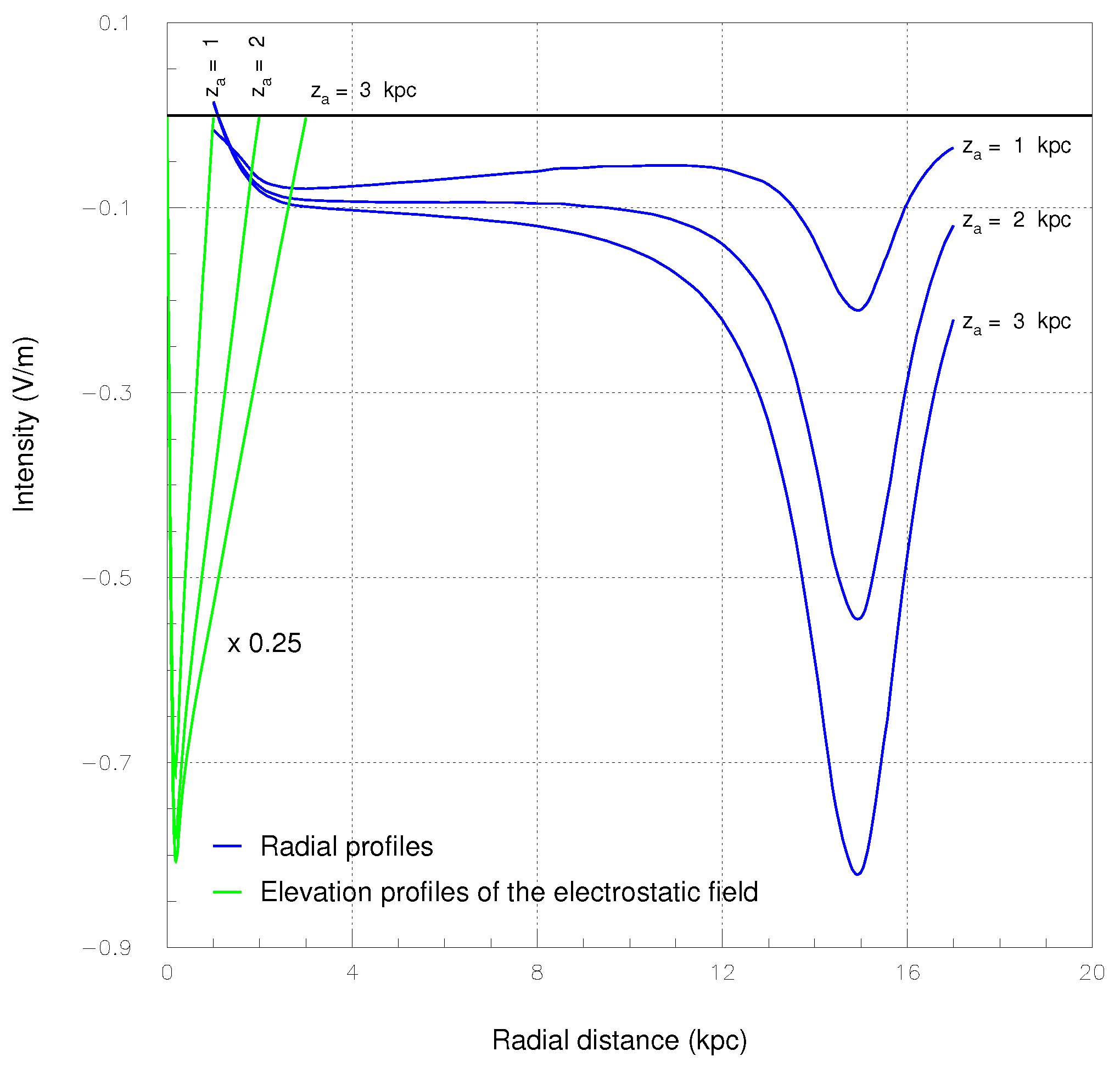

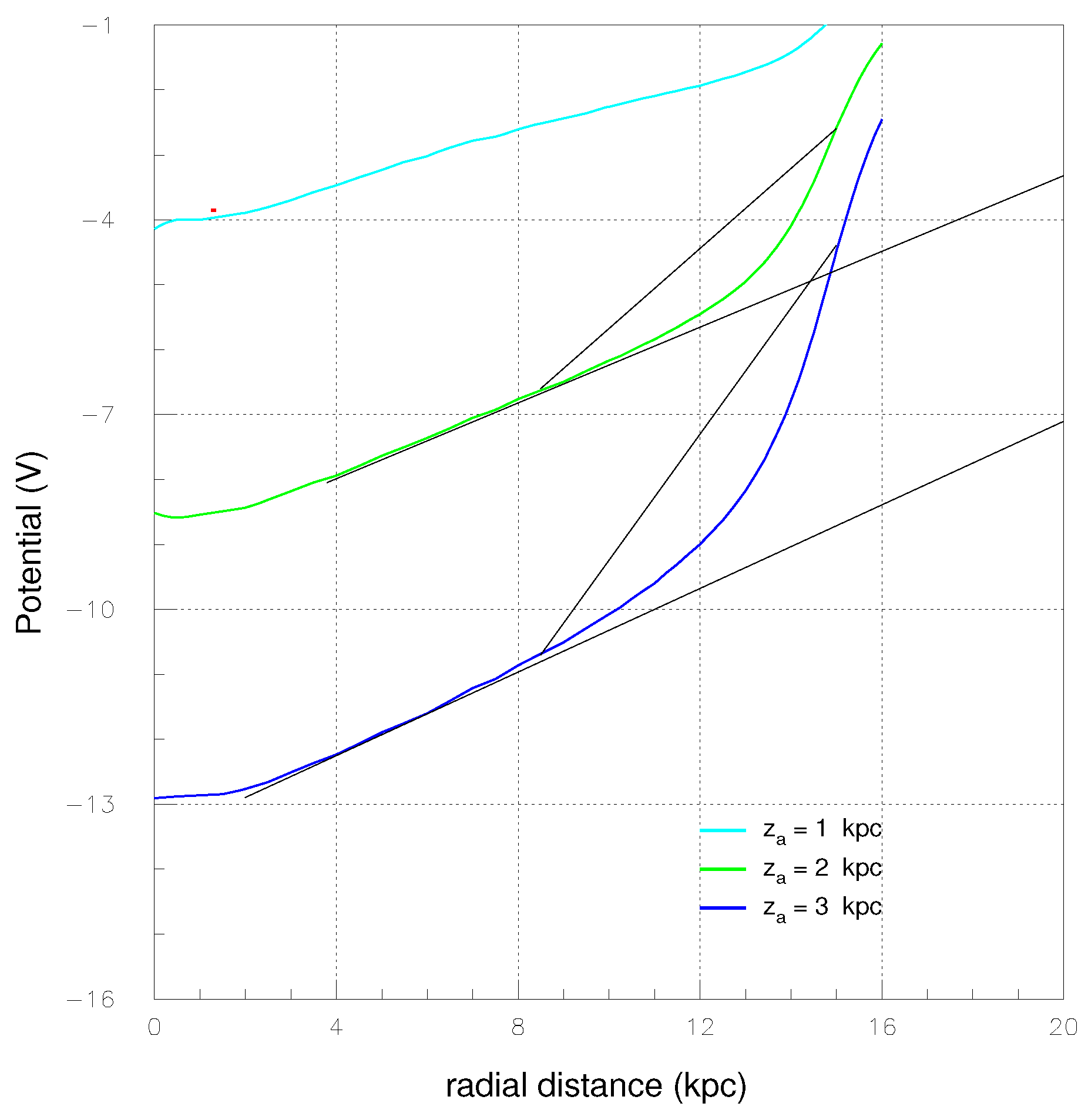

Radial field profiles,

E(

r,0) versus

r, are shown in

Figure 8 (blue curves) for

= 1, 2 and 3

. For example, for

= 2 the field intensity is almost constant in the range 3 ≤

r≤ 9

, then rapidly increases, reaching the maximum of 0.55

V/

m at the radial distance

r=

=15

, then, as expected, attenuates as any electrostatic body with of finite roundish form.

The field profiles in elevation,

E(0,

z)/4 versus

z, are shown in

Figure 8 (green curves) for

= 1, 2 and 3

. Field strengths are reduced by a round factor 4 to facilitate the visual comparison with radial strength

E(

r,0) in the same figure. The field

(0,

z) has maximum intensity for

z≤ 1

and direction toward the disk interior. For instance, at

= 1

the maximum of

E(0,

z) is

/

m at the elevation

z= ± 175

. Beyond the distance of 1

the direction of the field

(0,

z) points toward the exterior. Field intensity spans the interval 1-5

/

m, lower by 3 orders of magnitude than that in the range

r≤ 1

which however is not visible in

Figure 8.

Let us examine some aspects of the individual fields and quite useful in the following. Generally, for a preassigned radial distance and a halo size , the field intensity (0,z) decreases if z ≤ . For instance, for z = 1 and = 3 , the field intensity (0,3) is /m while for z = 1 and = 5 the field intensity (0,5) is /m.

Whenever is greater than h, the intensity (0,z) in the range z≤ is lower than ∣ (0,z) ∣ in the same range and the resulting field = + is directed toward the disc midplane. On the contrary, for z≥ the inequality, (0,z) ≥ ∣ (0,z) ∣ holds and the direction of the field is points outwardly. In the specified conditions E(0,z) vanish and changes sign. Consequently, there exists a coordinate ±z labelled for which the field (0,z) vanishes and changes sign. Of course, is a function of r.

The numerical example just discussed is very general indeed and the field inversion takes place in the whole range 0 <r≤ 15 and not only at r = 0. The behavior versus r for = 1,2,3 and 4 is shown in Figure 26 of ref. 8.

If the field configuration is examined not only for r = 0 but for an arbitrary value of r in the intervals, 0 <r≤ 15 and z≤ it results that the field is directed toward the center (exactly toward the Galactic midplane) and for z≥ the field is directed toward the exterior.

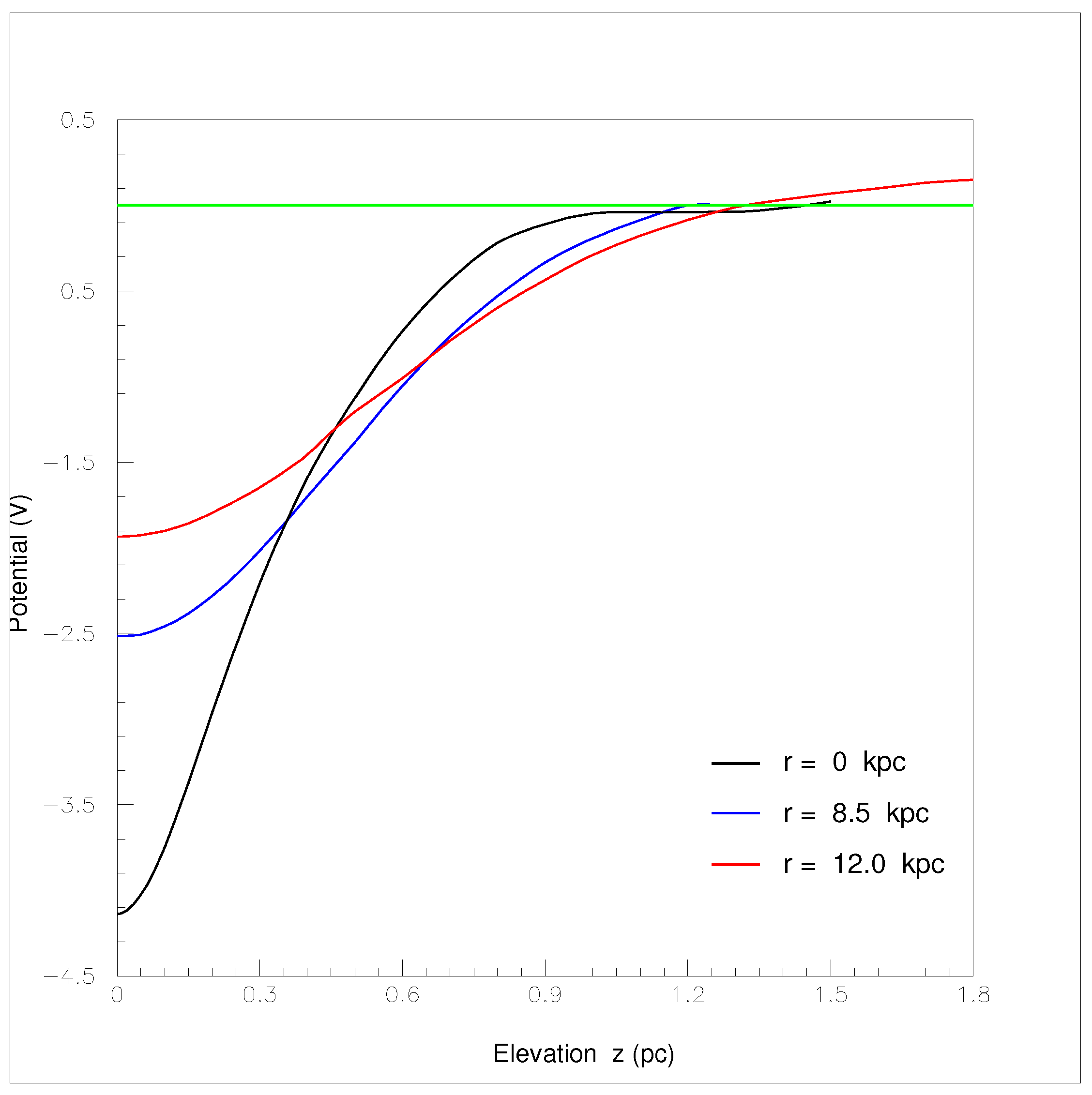

Notice that the values of the electrostatic potential

V(

r,

z) for the two squashed, concentric, coaxial cylinders (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 of

4) are thoroughly different from those of the Models 1 and 2 (

Figure 3-b and

Figure 5). As an example, the potential difference onto the Galactic midplane between the disc rim

= 15

and the solar system at

=

, namely, [

V(

,0) -

V(

,0)] is

V for

1,

V for Model 2 with

R = 300

,

= 15

and

n =

R/

= 20,

V with

R = 60

,

= 15

,

n = 4 and, finally,

V for

4 with

= 1

and

V for

4 with

= 2

. Such differences are intuitively and qualitatively expected from the charge distribution sizes.

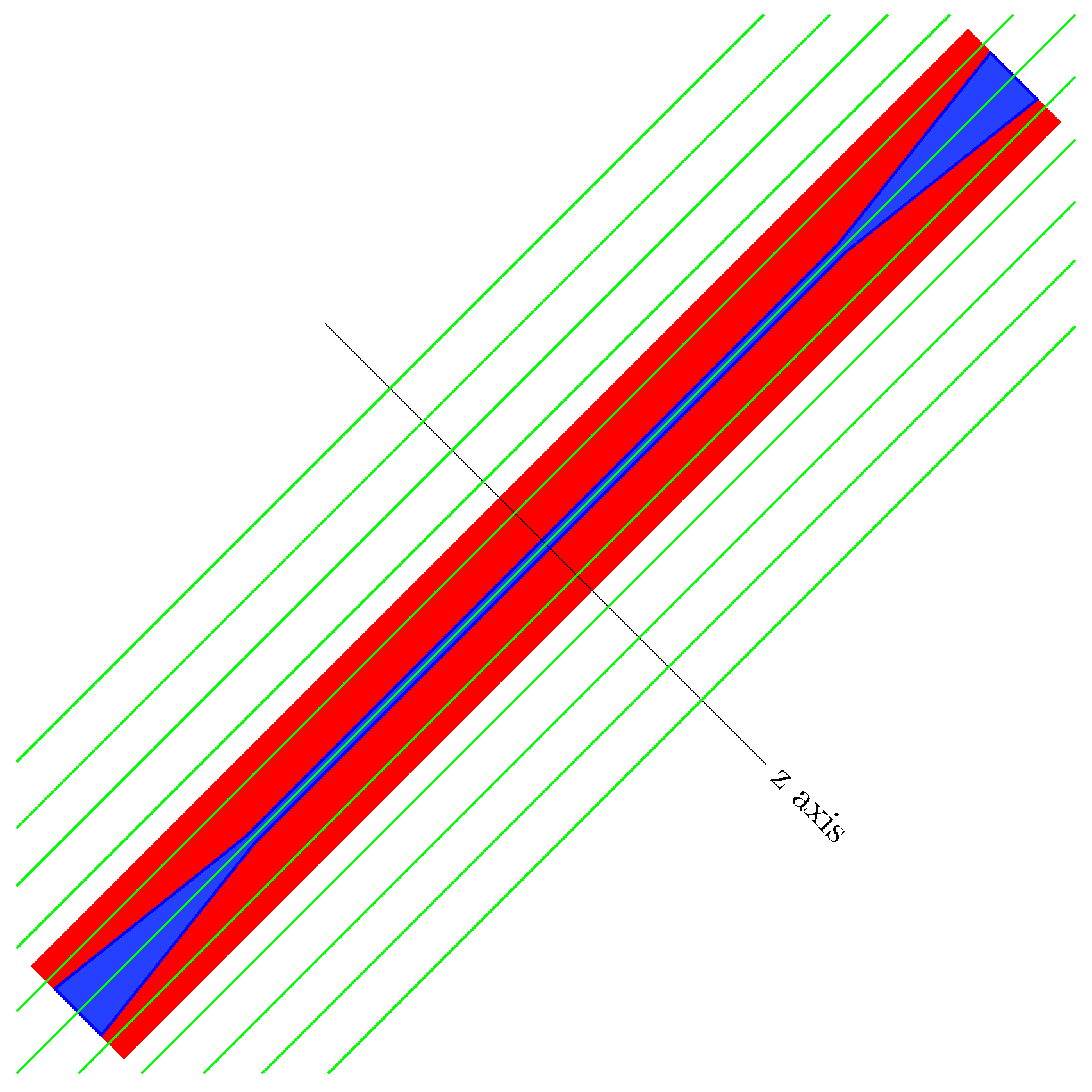

Improvements of

4 based on observational Astronomy are suggested in the legend of

Figure 11.

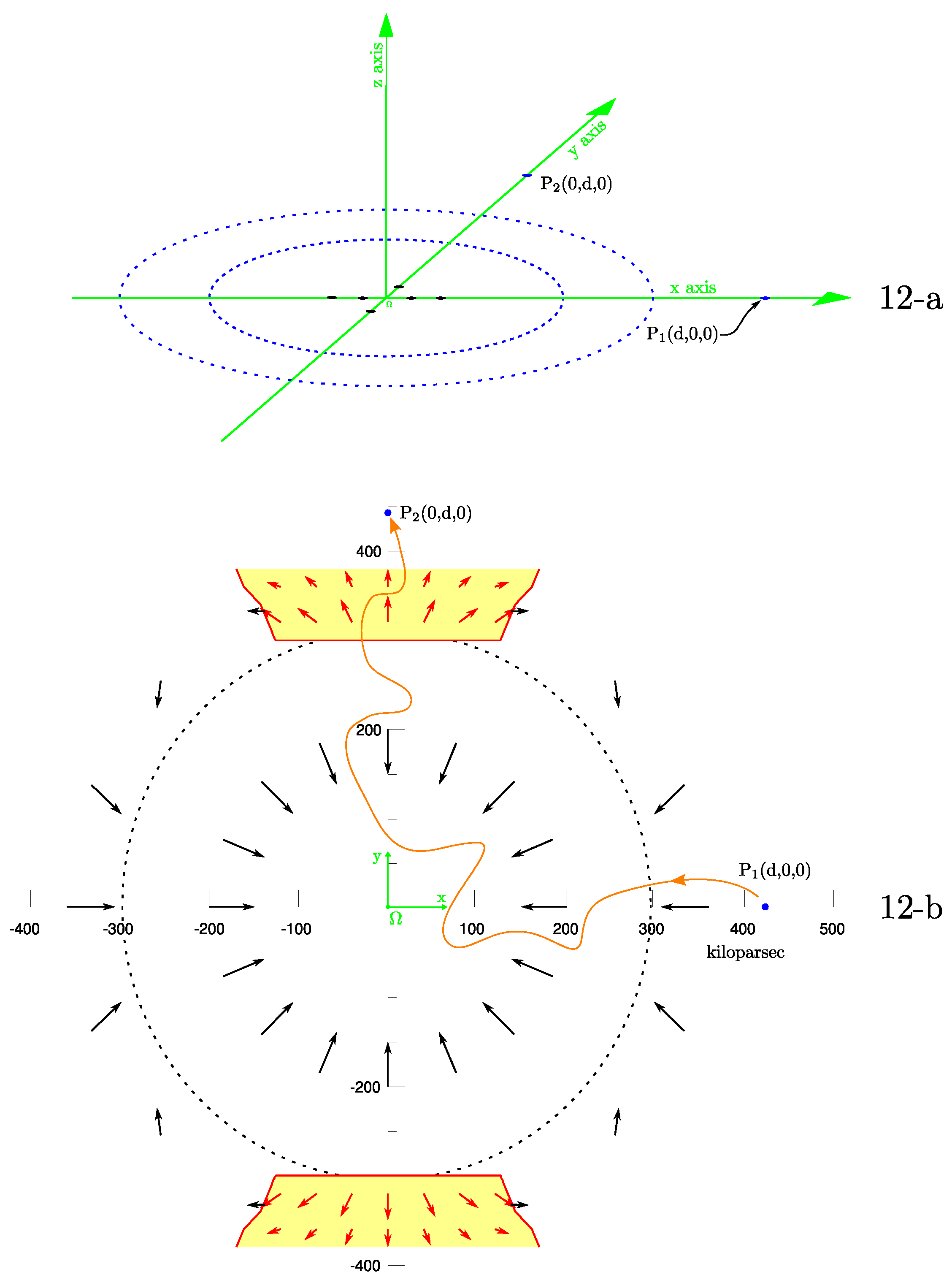

6. Discrete Charge Array Of Galactic Dimension

The electrostatic structures of 1 and 2 have a perfect radial symmetry. This implies that the electric field is strictly zero beyond the radius R, namely, beyond the maximum extension of the halo of positive electric charge transported by cosmic nuclei. What happens instead, if the radial symmetry is altered, yet maintaining the condition = - ?

A multipolar electric field extending in all the space is generated. Here it is desired to familiarize with this assertion with a numerical example by the examination

of a very simple electrostatic structure devoid of planar and spherical symmetries. A system of six pointlike negative charges is shown in

Figure 12-a. The total amount of negative charge is

= -

C. The six spheres lie in the

xy plane with origin

as shown in the same figure. Each sphere stores the charge

/6 and it is placed at the following (

x,

y,

z) coordinates: (-

,0, 0); (

,0, 0); (

a,0, 0); (

,0, 0), (0,

, 0) and (0,

a, 0) being

a the characteristic size of the system. Setting

a =

the maximum extension of the structure is 2

a = 15

. The spherical halo of positive charge with density

(

r) given by the Equation (

5) with

R = 300

overlaps the negative charge. The total charge within

R is zero i. e.

= -

. To simplify

Figure 12-a the positive charged halo is not shown but it is sketched in

Figure 2-c.

Beyond 2

a and within

R that is, between 15 and 300

the electric field strength behaves similarly to that of

Figure 3 of the double concentric sphere with zero charge. There are however slight differences due to the absence of the radial symmetry of the system shown in

Figure 12-a. The electric field on the

xy plane at the two radial distances 200 and 300

is shown in

Figure 12-b by a vector array.

The direction of the electric field along the

x axis points always to the center

while along the

y axis, at the characteristic distance

R -

i (

i for inversion and

i> 0) the field changes direction. In the specified conditions it turns out,

i =

. Beyond the distance

R -

i =

94

along the

y axis, the electric field points always outwardly. The electric field can be decomposed in a radial

and normal

component. In

xy plane at the approximate distance

R (

Figure 12-b) there is a line defined by all the points for which the radial electric field

vanishes. This line intercepts the coordinate

y =

-

i =

94

and

x = 0 and mimics a geographical divide: cosmic nuclei born and emitted beyond the line are accelerated toward the exterior. This region and the symmetric one are colored by yellow in

Figure 12-b and filled with red arrows.

On the contrary a cosmic nucleus, initially at rest and located at any arbitrary point along the x axis, will encounter an electric field always in the same favorable direction, precipitating toward the center of the electrostatic structure. This occurs not only along the x axis but in the entire annular region around the x axis beyond R = 300 .

The electrostatic potential generated by the 6 negative charges in a generic point

along the

x axis at the distance

d from the center

is:

Here it is desired to compare the electrostatic potential of the point

(

d, 0, 0) with that in the point

(0,

d, 0) of coordinate

d in the vicinity of

R= 300

as

Figure 12-a (not in scale) shows. Setting arbitrarily

d = 300

then, it turns out:

= -

V. The potential

generated by the positive charge is given by the Equation (7-a),

=

V and, hence, the resulting potential in

is:

=

-

= -

V. Thus, if this enormous electrostatic potential were converted into kinetic energy of a cosmic proton traveling between

and

the acquired energy is

. This elementary example highlights the huge energy gains and losses of cosmic nuclei roaming Galactic and intergalactic regions.

As the ideal and smooth charge distributions of Models 1,2,3 and 4 do not perfectly materialize in real galaxies, some features of the discrete charge distribution of 5 highlight the prominent common features of the other four models. For instance, galactic electric fields extend to all the space and do not vanish beyond the typical sizes of the charge distributions as it occurs in 1 and 2 ( i.e., beyond 30 and 300 , respectively).

Notice, finally, that both the electric field intensity and related electrostatic potential of the 5, inside and outside its characteristic size 2a = 15 , are comparable to those of the four models 1, 2, 3 and 4.

7. The Permanent Regeneration Of The Galactic Electric Field

In order to dissolve or nullify the electric field, , either the electric charge of the cosmic rays and that at the sources have to disappear from the or the electric generator powering cosmic-ray circulation has to cease operation.

The disappearance of

could occur only by charge neutralization accomplished by a hypothetical particle population transporting negative electric charges

= -

= -

C. This hypothetical population of negative charged particles has to exactly and finely compensate the positive charge

=

C over the entire

volume. The compensation mechanism has to accomplish charge neutralization at any sites of the

, not only globally. In fact, any disjoint charge distributions would generate a global electric field as it simply and unquestionably emerges from the two concentric charged spheres having an arbitrary offset in the charge distributions (

Figure 2-a and

Section 2).

The only negative charged particles with infinite lifetimes are electrons and antiprotons out of more than 300 elementary charged particles presently known. Electrons due to synchrotron emission in the magnetic field neither spatially nor energetically could accomplish such a chimeric compensation. The flux of cosmic-ray antiprotons are 4 orders of magnitude lower than those of cosmic-ray nuclei and, therefore, do not dissolve whatsoever the electric field.

Without an appropriate refurbishment of fresh cosmic rays, the electric field

would disappear in a cosmic-ray lifetime of (10-20)

years . The observed stability of the cosmic-ray intensity dictates that the field

is continuously regenerated by new born cosmic rays. The existence of cosmic rays and the stability of their intensity in the last billion years is a fact (see, for example, potassium data [

10]) which necessarily implies the existence and stability of the

electrostatic field.

The energy source powering cosmic-ray circulation ultimately derives from stars via photon ionization of interstellar gaseous materials. This theme is outside the perimeter of this work and is dealt with in [

8] (see

10 for the energy sources and

12 for an electric circuit imitating the cosmic-ray circulation through the

).

The arguments above lead to the plain conclusion that the electric field not only exists but it is an inviolable structure of the .

8. Compendium, Context And Conclusion

electric fields and related potentials have been computed with a

size of

m (15

) and the total electric charge

transported by cosmic rays which is in the range

-

C [

1], nominally set in this and other studies at

C (see footnote 1). These two input data have a solid, irrefutable empirical basis [

1,

8]. The computed intensities of the electric field span from fractions of

V/

m up to a few

V/

m and they are shown in

Figure 3-a,

Figure 4,

Figure 6 and

Figure 8. These field intensities through the

size of

m generate electrostatic potentials in the interval

-

V shown in

Figure 3-b,

Figure 5,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

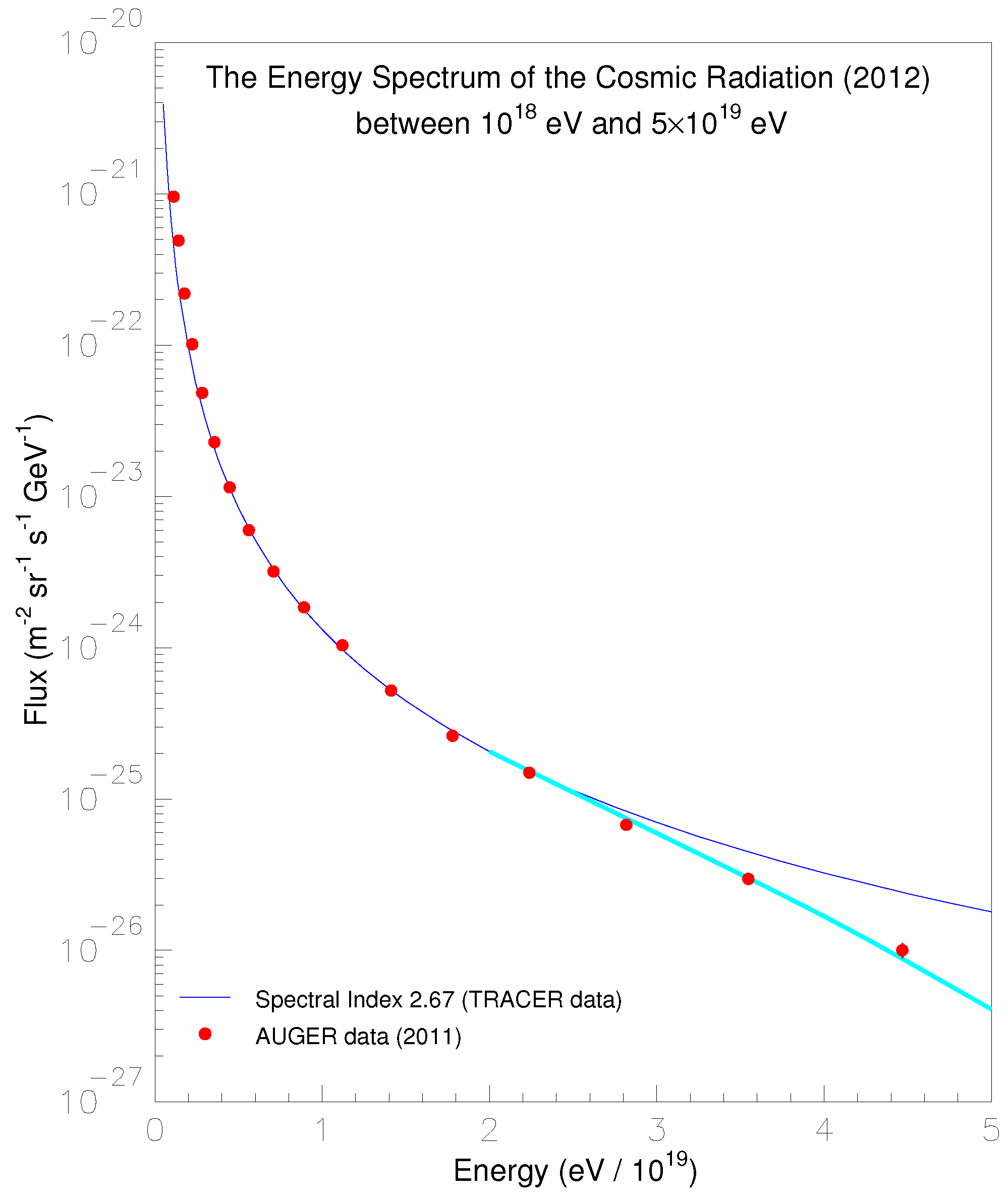

As far as the existence of the electric field is at stake, all the geometrical forms of the five models presented in this paper produce similar results. Only when fine features of the electric field have to be discerned, different models become relevant. For example, if the spectral index

of 2.65 of the cosmic-ray energy spectrum has to be predicted and correctly calculated, model 4 (two highly squashed concentric cylinders) offers the best agreement with cosmic-ray data (see [

8]

9 and 13).

Notice that quiescent, unbound protons with charge

q prone to the

electrostatic potential,

V(

r), convert in cosmic-ray protons of maximum energies,

qV =

q [

V(

) -

V(

) ] where

V(

) and

V(

) are the potentials at the radial distances

and

, respectively. Adopting the electrostatic potentials evaluated in this work and the Galactic disk radius of 15

, it turns out:

qV≃

-

, order of magnitude. From this, it descends a precious signature in the cosmic-ray energy spectrum: above the energy

qV no cosmic-ray proton is expected to circulate in the

because

qV is the maximum energy achievable by protons. For instance, if

=

(solar circle radius) and

= 15

(disk rim) then, in the

4,

V =

V(

) -

V(

) = -

V +

V =

V for a halo hight

= 2

and

V =

V for a halo hight

= 1

. These maximum energies entail a recognizable

break or

suppression in the smooth cosmic-ray energy spectrum above the ankle energy of

as displayed in

Figure 13.

It is a notable fact that these maximum cosmic-ray energies have been observed with the precise and unsurpassed energy resolution of the Auger experiment [

12] in the range 7-16 per cent in the energy band

-

. The break reported by the Auger experiment is at

[

11] as attested by

Figure 13. Only the unsurpassed energy resolution of the Auger experiment made possible the identification of the break in terms of the

electrostatic potential and, concomitantly, to dismiss the

GZK [

13,

14] interpretation of the same break. The HiRes Collaboration observed the

or

at the energy of

[

15] and interpreted it as

effect. This interpretation was reiterated by the Telescope Array (hereafter

TA) experiment [

16]. The critical theme of energy scales of the

and

instruments has been discussed elsewhere [

17]. The nature of the spectral break at

has been elucidated in 2013 [

18], in 2017 [

19,

20] and precognized in 2009 [

21].

The break in the energy spectrum represents a direct, solid and unmistakable support to the present evaluation of the

electrostatic potentials. It is direct because, given the electrostatic potential

V(

r), the energy achieved by cosmic-ray nuclei of atomic number

Z is just

ZqV as detailed above. It is solid because the break [

12,

15] has been reconfirmed by the Telescope Array collaboration [

16]. It is unmistakable because the Telescope Array collaboration [

16]. It is unmistakable because cosmic-ray Helium of charge 2

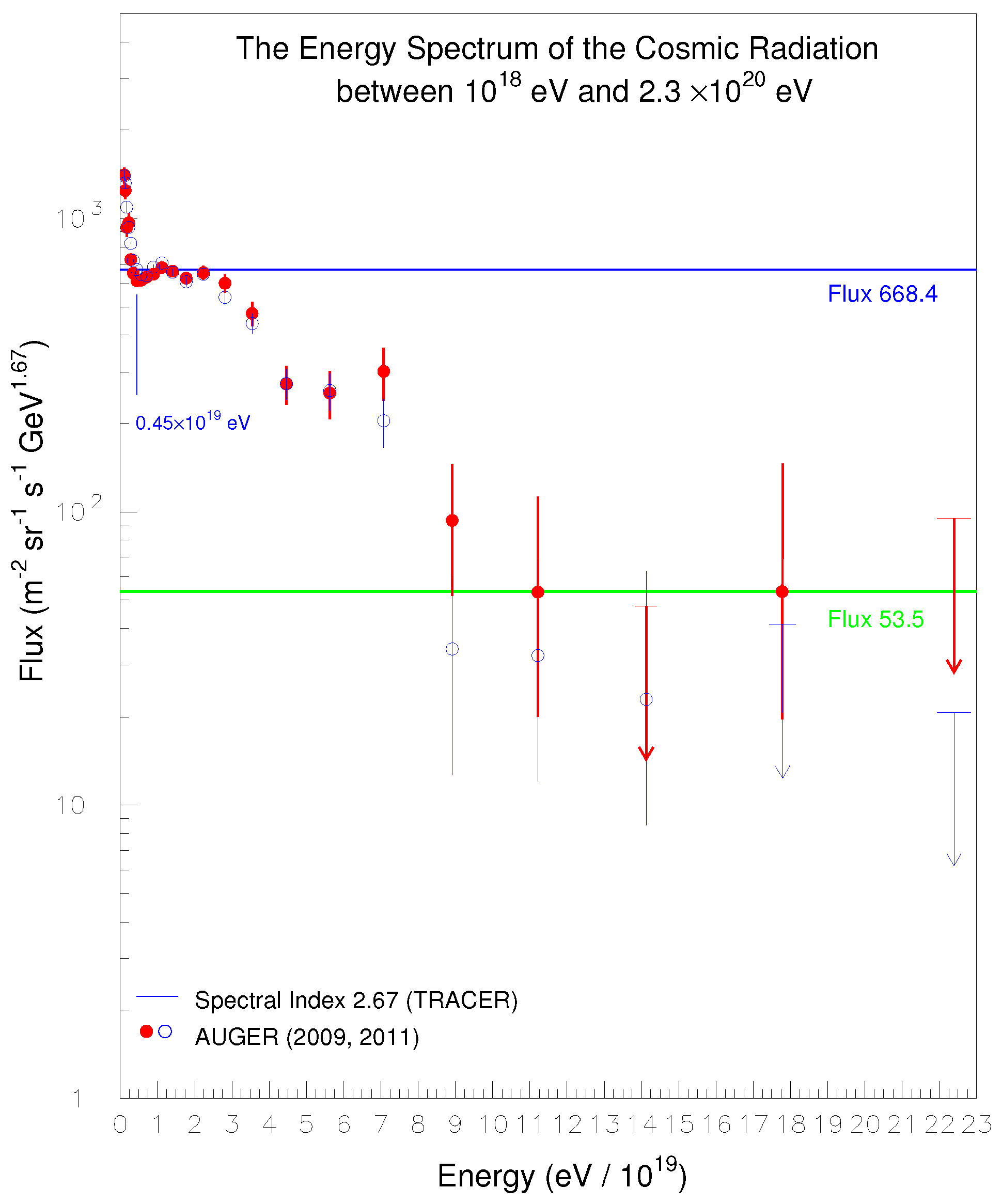

q produces a second break in the spectrum exactly where expected, namely, at the energy of

(

)

=

as displayed in

Figure 14 (on this issue see

13, Section

in [

8]).

In this and other works [

1,

8,

18,

21] the observation of the spectral break at

is regarded as a major discovery in

in the last half century but neither the discoverers (the HiRes, Auger and Telescope Array Collaborations) nor the presently prevailing cosmic-ray community recognized it as an effect of the

electrostatic potential. The spectral break was erroneously ascribed to the

effect [

13,

14] even if the stunning and unpredicted heavy chemical composition of the cosmic rays above

[

24,

25] and the spectral break at

(

Figure 13) are blatantly inconsistent with the

effect.

Closing this work it is proper to recognize and acknowledge its ultimate empirical foundation.

The negative electric charge,

= -

C from which the

electric field partially originates, resides on the thin disk made of stars, molecular and atomic Hydrogen and heavier elements. As the negative charge

rotates with the disk at about 240

/

s, a Galactic magnetic field is generated (here labeled first component). The magnetic field strength resulting from the rotating charge

is about 1

G [

1,

8] in agreement with the reiterated measurements of about 1

G performed during half a century by optical [

26,

27] and radio astronomers [

28,

29,

30,

31].

In addition to the first component, the circulation of

cosmic-ray particles through the Galaxy (see

Section 1) generates a second component of the

magnetic field of about 1

G derived elsewhere (see

14 and 15 of ref. [

8]). The derivation is simple but lengthy

3.

Adding the first component (rotating electric charge stored in the Galactic disk) to the second component (cosmic-ray circulation), the strength and magnetic filed line pattern (geometry) of the global, regular, Galactic magnetic field is obtained. The accordance of the magnetic field strength and its geometry with observations, due to its unique and variegated signature, is the ultimate empirical foundation the

electrostatic field and of this work

4.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Numerical Values of Electric Fields and Related Potentials

The charge distributions of

3 and 4 have cylindrical forms. In this case, unlike the formulae derived analytically from

, the electric fields and potentials have been calculated by a numerical method. The volume occupied by electric charge

= -

C is subdivided in half million small subvolumes each storing subcharges proportional to the subvolumes and the global electrostatic field is calculated by adding together all the subcharge elements. The method is cross-checked by structures where analytical formulae are available from classical

. In this

A some numerical data sets of electric fields of

4 are reported. The radial field profiles

E(

r,0) shown in

Figure 8 (blue curves) for

= 1, 2 and 3

are reported in

Table A1.

Table A2 reports the electrostatic potential versus elevation z of Model 4 for the positive charged halo of cosmic rays

= 1 kpc at the three radial distances r = 0, 8.5 and 12 kpc (data displayed in

Figure 9).

Table A3 reports the electrostatic potentials V(r, 0) at elevation z = 0 versus radial distance r of Model 4 for the three values

= 1, 2 and 3 kpc of the positive charged halo of cosmic rays (data displayed in

Figure 10).

Table A1.

Electric field in V/m versus radius r of Model 4 in the range 1.5 ≤ r ≤ 18 kpc for three values of the positive charged halo of the cosmic rays = 1,2 and 3 kpc.

Table A1.

Electric field in V/m versus radius r of Model 4 in the range 1.5 ≤ r ≤ 18 kpc for three values of the positive charged halo of the cosmic rays = 1,2 and 3 kpc.

| r (kpc) |

= 1 kpc |

= 2 kpc |

= 3 kpc |

| 1.5 |

-0.041 |

-0.0462 |

-0.049550 |

| 2.0 |

-0.068 |

-0.0769 |

-0.081620 |

| 2.5 |

-0.078 |

-0.0881 |

-0.094085 |

| 3.0 |

-0.079 |

-0.0917 |

-0.098739 |

| 3.5 |

-0.078 |

-0.0927 |

-0.010104 |

| 4.0 |

-0.07 |

-0.0934 |

-0.010274 |

| 4.5 |

-0.07 |

-0.0935 |

-0.010450 |

| 5.0 |

-0.07 |

-0.0937 |

-0.010603 |

| 5.5 |

-0.07 |

-0.0937 |

-0.010765 |

| 6.0 |

-0.06 |

-0.0941 |

-0.010966 |

| 6.5 |

-0.06 |

-0.0940 |

-0.011160 |

| 7.0 |

-0.060 |

-0.0942 |

-0.011394 |

| 7.5 |

-0.068 |

-0.0945 |

-0.011667 |

| 8.0 |

-0.060 |

-0.0955 |

-0.011994 |

| 8.5 |

-0.057 |

-0.0952 |

-0.012391 |

| 9.0 |

-0.056 |

-0.098 |

-0.012930 |

| 9.5 |

-0.055 |

-0.100 |

-0.013592 |

| 10.0 |

-0.055 |

-0.103 |

-0.014446 |

| 10.5 |

-0.054 |

-0.107 |

-0.015550 |

| 11.0 |

-0.054 |

-0.114 |

-0.017078 |

| 11.5 |

-0.055 |

-0.124 |

-0.018169 |

| 12.0 |

-0.058 |

-0.139 |

-0.022144 |

| 12.5 |

-0.065 |

-0.164 |

-0.016623 |

| 13.0 |

-0.075 |

-0.202 |

-0.033278 |

| 13.5 |

-0.097 |

-0.268 |

-0.043612 |

| 14.0 |

-0.0136 |

-0.371 |

-0.058729 |

| 14.5 |

-0.0190 |

-0.498 |

-0.075920 |

| 15.0 |

-0.0210 |

-0.543 |

-0.081864 |

| 15.5 |

-0.015 |

-0.434 |

-0.067690 |

| 16.0 |

-0.095 |

-0.286 |

-0.047475 |

| 16.5 |

-0.056 |

-0.182 |

-0.032094 |

| 17.0 |

-0.035 |

-0.119 |

-0.022114 |

| 17.5 |

-0.022 |

-0.081 |

-0.015702 |

| 18.0 |

-0.016 |

-0.058 |

-0.011569 |

Table A2.

Electrostatic potential in units of

V versus elevation z of Model 4 for the positive charged halo of cosmic rays

= 1 kpc at the three radial distances r = 0, 8.5 and 12 kpc (data displayed in

Figure 9).

Table A2.

Electrostatic potential in units of

V versus elevation z of Model 4 for the positive charged halo of cosmic rays

= 1 kpc at the three radial distances r = 0, 8.5 and 12 kpc (data displayed in

Figure 9).

| z (pc) |

r = 0 |

r = 8.5 kpc |

r = 12 kpc |

| 0 |

-4.14 |

-1.93380 |

-2.51648 |

| 10 |

-4.13 |

-1.93335 |

-2.51510 |

| 50 |

-4.03 |

-1.9256 |

-2.50568 |

| 150 |

-3.74 |

-1.8997 |

-2.45787 |

| 150 |

-3.37 |

-1.8560 |

-2.38254 |

| 200 |

-2.96 |

-1.7949 |

-2.28018 |

| 250 |

-2.57 |

-1.7252 |

-2.15665 |

| 300 |

-2.21 |

-1.6466 |

-2.01585 |

| 350 |

-1.88 |

-1.5564 |

-1.86311 |

| 400 |

-1.59 |

-1.4552 |

-1.70035 |

| 450 |

-1.34 |

-1.3441 |

-1.53425 |

| 500 |

-1.12 |

-1.2324 |

-1.38299 |

| 600 |

-0.732 |

-1.0091 |

-1.05266 |

| 700 |

-0.437 |

-0.79123 |

-0.76435 |

| 800 |

-0.218 |

-0.59810 |

-0.52876 |

| 900 |

-0.11 |

-0.434008 |

-0.33320 |

| 1000 |

-0.045 |

-0.289041 |

-0.192228 |

| 1100 |

-0.029 |

-0.17583 |

-0.085085 |

| 1200 |

-0.021 |

-0.085482 |

-0.0054361 |

| 1300 |

-0.021 |

-0.010932 |

0.0478883 |

Table A3.

Electrostatic potentials V(r, 0) at elevation z = 0 in units of

V versus radial distance r of Model 4 for the three values

= 1, 2 and 3 kpc of the positive charged halo of cosmic rays (data displayed in

Figure 10).

Table A3.

Electrostatic potentials V(r, 0) at elevation z = 0 in units of

V versus radial distance r of Model 4 for the three values

= 1, 2 and 3 kpc of the positive charged halo of cosmic rays (data displayed in

Figure 10).

| r (kpc) |

z = 1 kpc |

z = 2 kpc |

z = 3 kpc |

| 0.0 |

-4.138 |

-8.510 |

-12.794 |

| 0.5 |

-3.996 |

-8.576 |

-12.919 |

| 1.0 |

-3.995 |

-8.544 |

-12.290 |

| 1.5 |

-3.949 |

-8.490 |

-12.841 |

| 2.0 |

-3.890 |

-8.431 |

-12.769 |

| 2.5 |

-3.807 |

-8.313 |

-12.656 |

| 3.0 |

-3.696 |

-8.183 |

-12.510 |

| 3.5 |

-3.575 |

-8.051 |

-12.366 |

| 4.0 |

-3.472 |

-8.945 |

-12.239 |

| 4.5 |

-3.351 |

-7.788 |

-12.072 |

| 5.0 |

-3.230 |

-7.636 |

-11.894 |

| 5.5 |

-3.112 |

-7.502 |

-11.748 |

| 6.0 |

-3.016 |

-7.362 |

-11.602 |

| 6.5 |

-2.890 |

-7.206 |

-11.407 |

| 7.0 |

-2.786 |

-7.049 |

-11.215 |

| 7.5 |

-2.718 |

-6.926 |

-11.070 |

| 8.0 |

-2.605 |

-6.761 |

-10.857 |

| 8.5 |

-2.516 |

-6.626 |

-10.687 |

| 9.0 |

-2.441 |

-6.496 |

-10.503 |

| 9.5 |

-2.357 |

-6.326 |

-10.284 |

| 10.0 |

-2.259 |

-6.167 |

-10.073 |

| 10.5 |

-2.174 |

-6.006 |

-9.838 |

| 11.0 |

-2.094 |

-5.844 |

-9.598 |

| 11.5 |

-2.014 |

-5.654 |

-9.309 |

| 12.0 |

-1.933 |

-5.451 |

-8.998 |

| 12.5 |

-1.830 |

-5.222 |

-8.627 |

| 13.0 |

-1.726 |

-4.948 |

-8.174 |

| 13.5 |

-1.600 |

-4.588 |

-7.584 |

| 14.0 |

-1.424 |

-4.093 |

-6.788 |

| 14.5 |

-1.163 |

-3.415 |

-5.742 |

| 15.0 |

-0.844 |

-2.588 |

-4.494 |

| 15.5 |

-0.567 |

-1.840 |

-3.340 |

| 16.0 |

-0.366 |

-1.282 |

-2.454 |

References

- Codino, A. The ubiquitous mechanism accelerating cosmic rays at all the energies. In Proceedings of the 37th International Cosmic Ray Conference, 2022, p. 450, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2109.04388]. [CrossRef]

- DAMPE Collaboration.; Ambrosi, G.; An, Q.; Asfandiyarov, R.; Azzarello, P.; Bernardini, P.; Bertucci, B.; Cai, M.S.; Chang, J.; Chen, D.Y.; et al. Direct detection of a break in the teraelectronvolt cosmic-ray spectrum of electrons and positrons. 2017, 552, 63–66. [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, S.; Ackermann, M.; Ajello, M.; Atwood, W.B.; Baldini, L.; Barbiellini, G.; Bastieri, D.; Bellazzini, R.; Bloom, E.D.; Bonino, R.; et al. Cosmic-ray electron-positron spectrum from 7 GeV to 2 TeV with the Fermi Large Area Telescope. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 95, 082007. [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.; Graeve, R. The distribution of thermal and nonthermal radio continuum emission of M31. 1982, 105, 192–199.

- Tabatabaei, F.S.; Schinnerer, E.; Murphy, E.; Beck, R.; Hughes, A.; Groves, B. The resolved radio-FIR correlation in nearby galaxies with Herschel and Spitzer. In Proceedings of the The Spectral Energy Distribution of Galaxies - SED 2011; Tuffs, R.J.; Popescu, C.C., Eds., 2012, Vol. 284, IAU Symposium, pp. 400–403, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1111.6252]. [CrossRef]

- Gajović, L.; Heesen, V.; Brüggen, M.; Edler, H.W.; Adebahr, B.; Pasini, T.; de Gasperin, F.; Basu, A.; Weżgowiec, M.; Horellou, C.; et al. The low-frequency flattening of the radio spectrum of giant H II regions in M 101. 2025, 695, A41, [arXiv:astro-ph.GA/2502.08713]. [CrossRef]

- Lozinskaya, T.A.; Kardashev, N.S. The Thickness of the Gas Disk of the Galaxy from 21-cm Observations. 1963, 7, 161.

- Codino, A. The ubiquitous mechanism accelerating cosmic rays at all the energies; Società editrice Esculapio: Bologna, Italy, 2020.Corrected reprint published in 2023.

- Jackson, P.D.; Kellman, S.A. A Redetermination of the Galactic H i Half-Thickness and a Discussion of Some Dynamical Consequences. 1974, 190, 53–58. [CrossRef]

- Voshage, H.; Feldmann, H.; Braun, O. Investigations of cosmic-ray-produced nuclides in iron meteorites: 5. More data on the nuclides of potassium and noble gases, on exposure ages and meteoroid sizes. Zeitschrift Naturforschung Teil A 1983, 38, 273–280. [CrossRef]

- Salamida, F. Update on the measurement of the CR energy spectrum above 10**18-eV made using the Pierre Auger Observatory. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Cosmic Ray Conference, 8 2011.

- Abraham, J.; Abreu, P.; Aglietta, M.; Aguirre, C.; Allard, D.; Allekotte, I.; Allen, J.; Allison, P.; Alvarez-Muñiz, J.; Ambrosio, M.; et al. Observation of the Suppression of the Flux of Cosmic Rays above 4 × 1019 eV. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 061101. [CrossRef]

- Greisen, K. End to the Cosmic-Ray Spectrum? 1966, 16, 748–750. [CrossRef]

- Zatsepin, G.T.; Kuz’min, V.A. Upper Limit of the Spectrum of Cosmic Rays. Soviet Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Physics Letters 1966, 4, 78.

- Abbasi, R.U.; Abu-Zayyad, T.; Allen, M.; Amman, J.F.; Archbold, G.; Belov, K.; Belz, J.W.; Ben Zvi, S.Y.; Bergman, D.R.; Blake, S.A.; et al. First Observation of the Greisen-Zatsepin-Kuzmin Suppression. Physical Review Letters 2008, 100, 101101, [astro-ph/0703099]. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Zayyad, T.; Aida, R.; Allen, M.; Anderson, R.; Azuma, R.; Barcikowski, E.; Belz, J.W.; Bergman, D.R.; Blake, S.A.; Cady, R.; et al. The Cosmic-Ray Energy Spectrum Observed with the Surface Detector of the Telescope Array Experiment. 2013, 768, L1, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1205.5067]. [CrossRef]

- Codino, A. About the consistency of the energy scales of past and present instruments detecting cosmic rays above the ankle energy. arXiv e-prints 2017, p. arXiv:1710.06659, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1710.06659]. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1710.06659. [CrossRef]

- Codino, A. The absence of the GZK depression in the energy spectrum of the cosmic radiation. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Cosmic Ray Conference, 2013, p. 0144.

- Codino, A. About the Energy Interval beyond the Ankle Where the Cosmic Radiation Consists Only of Ultraheavy Nuclei from Zinc to the Actinides. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics 2017, pp. 225–237. [CrossRef]

- Codino, A. The energy spectrum of ultraheavy nuclei above 1020 eV. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics 2017, pp. 1540–1550, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1707.02487]. [CrossRef]

- Codino, A. Redundant failures of the dip model of the extragalactic cosmic radiation. arXiv e-prints 2009, p. arXiv:0911.4273, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/0911.4273]. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.0911.4273. [CrossRef]

- Abraham, J.; Abreu, P.; Aglietta, M.; Ahn, E.J.; Allard, D.; Allen, J.; Alvarez-Muñiz, J.; Ambrosio, M.; Anchordoqui, L.; Andringa, S.; et al. Measurement of the energy spectrum of cosmic rays above 1018 eV using the Pierre Auger Observatory. Physics Letters B 2010, 685, 239–246, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1002.1975]. [CrossRef]

- Pierre Auger Collaboration. Measurement of the cosmic ray spectrum above 4 × 1018 eV using inclined events detected with the Pierre Auger Observatory. 2015, 2015, 049–049, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1503.07786]. [CrossRef]

- Unger, M.; Engel, R.; Schüssler, F.; Ulrich, R.; Pierre Auger Collaboration. Study of the Cosmic Ray Composition above 0.4 EeV using the Longitudinal Profiles of Showers observed at the Pierre Auger Observatory. Astronomische Nachrichten 2007, 328, 614, [arXiv:astro-ph/0706.1495]. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, R.U.; Abe, M.; Abu-Zayyad, T.; Allen, M.; Anderson, R.; Azuma, R.; Barcikowski, E.; Belz, J.W.; Bergman, D.R.; Blake, S.A.; et al. Study of Ultra-High Energy Cosmic Ray composition using Telescope Array’s Middle Drum detector and surface array in hybrid mode. Astroparticle Physics 2015, 64, 49–62, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1408.1726]. [CrossRef]

- Mathewson, D.S.; Ford, V.L. Polarization observations of 1800 stars. 1971, 153, 525. [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.V.; Spitzer, Jr., L. Magnetic Alignment of Interstellar Grains. 1967, 147, 943. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.L.; Qiao, G.J. The magnetic field in the disk of our Galaxy. 1994, 288, 759–772.

- Rand, R.J.; Kulkarni, S.R. The Local Galactic Magnetic Field. 1989, 343, 760. [CrossRef]

- Rand, R.J.; Lyne, A.G. New Rotation Measures of Distant Pulsars in the Inner Galaxy and Magnetic Field Reversals. 1994, 268, 497. [CrossRef]

- Mitra, D.; Wielebinski, R.; Kramer, M.; Jessner, A. The effect of HII regions on rotation measure of pulsars. 2003, 398, 993–1005. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

Consider two equal masses m retaining the same electric charge q (see Figure 1 in [7]. They experience an electrostatic repulsion and, at the same time, a gravity pull. Equilibrium or balance between the two forces occurs when the charge-to-mass ratio is q/m = = C/ where = F/m and G = 42 /. The definition of balance charge ( the subscript b is for balance) is, ≡m and, in turn, ζ≡q/. The dimensionless variable ζ as charge unit is devoid of any subtlety, just a definition. For example, the balance charge of the is M = C where M = is an arbitrary mass adopted in works [1,8] and others. |

| 2 |

For simplicity it is admitted that in the propagation of cosmic rays the particle density from the emitting source depends on the distance r as 1/r up to a characteristic distance R. This behavior is ascribed to the chaotic components of the magnetic field around the source. |

| 3 |

The traditional concepts of Cosmic Ray Physics as freezed in textbooks and articles in top reviews are inane to determine the geometry of the regular magnetic field. In fact traditional concepts adopt the diffusive propagation of cosmic rays which do not form current loops in the Galaxy. As the diffusive propagation occurs in magnetic fields and ignores the Galactic electrostatic field, it is detached from the physical reality of the as proved by plenty of measurements. |

| 4 |

This work is dedicated to Livia Chiavaroli Codino. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).