Submitted:

24 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Primitives and the single observable.

What we prove.

Why it matters.

- Clean separation of concerns. Analytic special–function estimates are not needed: once maps are isometric/contractive and intertwine , the inequality is a two–line argument in (Cauchy–Schwarz in the comparison geometry), with the calibration/expectation behaving as in [12].

Conceptual position.

Scope and hypotheses.

Contributions (at a glance).

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

Proof idea in one line.

Organization.

2. Setting and Standing Hypotheses

Boundary comparison geometry.

Interchangeability (calibration).

DSFL residual on .

Admissible kernels.

Teichmüller kernel class.

Well–Posedness, Invariances, and Basic Calculus

Data–Processing Inequality and Composition

Well–Posedness, Invariances, and Basic Calculus

Data–Processing Inequality and Composition

Gluing and Pachner Moves

Quantitative Refinements and Robustness

Consequences for Algorithms and Exact Recursion

Teichmüller Specialization: Why Admissibility Holds and What It Buys

Consequences (scientific takeaways).

- Certified triangulation robustness. The DSFL residual is a Lyapunov functional along Pachner sequences; any pipeline of local simplifications cannot inflate calibrated mismatch.

- Quantitative seam control. Principal angles between boundary polarizations bound leakage and algorithmic conditioning by and .

- Recursion reliability. Exact recursion steps modeled by admissible kernels inherit monotone residual decay; uniform contractivity yields exponential envelopes in the recursion depth.

- Chart independence. By Proposition 1, reparametrizations/changes of boundary chart by unitary/metaplectic transforms preserve the value of .

- Perturbation stability. Under spectral gaps, Davis–Kahan (Lemma 5) gives Lipschitz robustness of and against boundary perturbations.

3. Main Results

3.1. Strengthenings, Equality Cases, and Strictness

3.2. Quantitative and Robust Variants

3.3. Compositions, Randomization, and Certification

3.4. Consequences for Exact Recursion and DSFL Envelopes

3.5. Categorical and Structural Corollaries

Scientific consequences (summary).

- Gluing robustness: is a Lyapunov functional under Pachner moves (Theorem 5); triangle–free simplification pipelines cannot inflate calibrated mismatch.

- Quantitative interfaces: principal angles control seam leakage and conditioning (Proposition 9); Davis–Kahan stability (Sec. Section 2) transfers to robustness of and .

- Noisy pipelines: small violations of admissibility produce controlled slack (Theorem 6), useful for discretized numerics and floating–point implementations.

- Probabilistic guarantees: residuals form a supermartingale for randomized admissible updates (Theorem 7), yielding convergence and certification criteria.

- Categorical packaging: DSFL provides a natural transformation to a residual modular functor with projective unitarity (Proposition 10).

- asinglecomparison Hilbert geometry in which both channels live and the residual is measured;

- admissibility, i.e. boundary/interior mapsintertwinethe calibration and arenonexpansivein ;

- for the concrete Teichmüller class, two structural identities: theunitarityof the edge operator and thepentagon (five–term) identity, which together force the gluing operator to be (projectively) unitary and to intertwine the calibration.

4. Teichmüller Kernels: Why Admissibility Holds

4.1. Operators and Identities

Heisenberg pair and modular double.

Faddeev quantum dilogarithm and edge operator.

4.2. Isometry and Intertwining for Pachner Moves

4.3. Consequences and Refinements

Equality and strictness.

Projective phases and anomaly line.

Robustness to discretization/regularization.

Caps/cups and .

Seam conditioning via principal angles.

No special–function estimates.

Consequences.

- Axioms ⇒ Theorems. In Teichmüller TQFT, gluing stability becomes a Theorem (unitarity + pentagon + calibration) rather than an axiom.

- Chart–independence of certification. Because , residual certification (no inflation) is invariant under unitary changes of boundary charts (metaplectic transforms).

- Numerical robustness. The proof is purely operator–theoretic; it carries over to finite–dimensional discretizations once we enforce (approximate) intertwining and spectral–norm by construction (see next section).

5. Minimal Verification Harness (Reproducible Tests)

Aim.

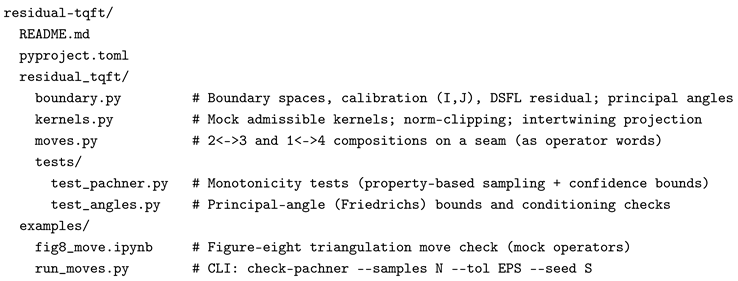

A. Repository Skeleton (Annotated)

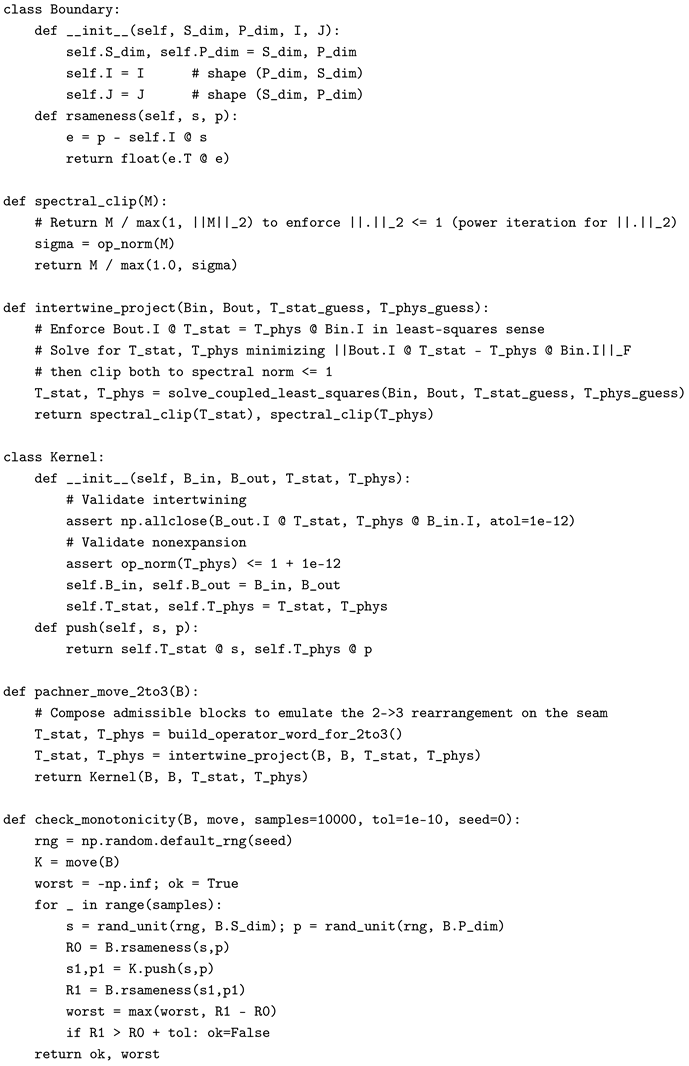

B. Core API (Pythonic Pseudocode with Enforcement)

C. Acceptance Criterion and Statistical Confidence

Numerical stability notes.

- Intertwining enforcement. Use intertwine_project once per move instance to project a guessed pair onto the affine subspace , then clip both by spectral_clip.

- Operator norm. Estimate via the power method with a stringent stopping tolerance (e.g. ); add a safety factor in the assertion.

- Principal angles (optional). Provide principal_cosine(Pin,Pout) via SVD of to log the conditioning proxy .

D. What the harness proves in practice

6. Afterword

6.1. Universality Principle and a Converse

- Ψ is nonexpansive on theresidual directions: for all e;

- Intertwining holds: .

6.2. Robustness, Limits, and Failure Modes

Small violations.

Failure modes.

- Nonintertwining. If has large operator norm, the residual can inflate by even when .

- Expansion. If , then directions e in the top singular subspace inflate the residual by .

6.5. Categorical Consequences and Anomaly Bookkeeping

6.6. Algorithmic and Numerical Consequences

Certification by supermartingales.

- almost–sure convergence of ;

- tail bounds for empirical violation rates via Hoeffding/Bernstein, enabling reproducible pass/fail certificates;

- linear semi–log decay when the mean contraction is uniform ().

Seam conditioning.

6.9. Teichmüller Specialization: Why It Works “for Free”

- Unitarity. The edge operator (built from and the metaplectic Gaussian) is unitary on the modular–double Plancherel space.

- Pentagon identity. The move holds as a strong operator identity (no approximation).

- Pointer compatibility. Orthogonal conditional expectations onto MASAs commute with unitary conjugations of those MASAs (change of polarization).

6.10. Outlook: Envelopes, Modularity, and Testable Conjectures

DSFL envelopes and resurgence.

Quantum modularity link (program).

Practical takeaway.

Author’s Note.

Acknowledgments

Appendix A. Notation

| Symbol | Type / Domain | Meaning / Assumptions |

|---|---|---|

| Spaces and geometry | ||

| Hilbert space | Comparison geometry for both channels; inner product , norm . | |

| Linear space | Statistical channel space (e.g., vacuum/constraint objects). | |

| Closed subspace | Physical channel space (e.g., observables/fields inside ). | |

| Projector | Metric projection onto the admissible statistical subspace; encodes statistical gauge. | |

| Channels and maps | ||

| State (stat.) | Statistical channel. In one-budget model: , , . | |

| State (phys.) | Physical channel. | |

| Linear map | Interchangeability (calibration/embedding) of s into . | |

| Linear map | Statistical representative of p; satisfies . | |

| Linear map | Calibration operator (units/indices/gauge); often . | |

| Interchangeability identities | ||

| Identity | Pushing p to then back gives p. | |

| Identity | Pushing s to then back gives the projected s. | |

| Residuals (mismatch measures) | ||

| Scalar | Physical-side residual: . | |

| Scalar | Statistical-side residual: . | |

| Scalar | Canonical residual (often ). | |

| Scalar | Differential residual (e.g., ). | |

| Propagation and DSFL parameters (optional, when dynamics are used) | ||

| Element of | Residual vector in . | |

| Operator on | Dissipative/elliptic part (Dirichlet/Lichnerowicz/constitutive). | |

| g | Element of | Controlled remainder (lower orders, background drift). |

| Scalar | Gap/coercivity constant: . | |

| Scalar | Remainder bound: . | |

| Scalar | DSFL rate in (when dynamics are present). | |

| Angles and subspace geometry | ||

| Subspaces of | Physical subspace and calibrated statistical range. | |

| Projectors | Orthogonal projectors onto U and V. | |

| Angle | Friedrichs angle: . | |

| Matrices/bases | Orthonormal bases spanning U and V; CS/SVD: , . | |

| Admissible (“entanglement-like”) redistribution | ||

| Linear map | Statistical operation (Markov/coherent/CPTP marginal). | |

| Linear map | Physical operation (contractive in ). | |

| Intertwining | Identity | , . |

| Contractivity | Inequality | , . |

| Residual monotonicity | Inequality | . |

| One-budget (statistical resource) model | ||

| Fixed template | Global statistical prototype (primordial sameness), normalized. | |

| Nonnegative weight | Share field, ; . | |

| Kernel | Markov kernel: , ; preserves . | |

| Budget/causality constraints | ||

| Counter | Local complexity/effective rank/energy counter; monotone & subadditive. | |

| Speed | Carrier/relay speed (e.g., wave speed, Lieb–Robinson velocity). | |

| Length | Correlation diameter/interaction range. | |

| Causal ceiling | Bound | for a moving volume . |

| Sector shorthands (used in mini-cases) | ||

| PDE | — | , , Helmholtz split , Poincaré . |

| OA/QMS | — | GNS space; conditional expectation (orthogonal projector). |

| OU/free | — | , covariance , gap . |

| Constants frequently used | ||

| Scalar | Uniform ellipticity margin (PDE). | |

| Scalars | Poincaré/spectral constants (domain/semigroup). | |

| Scalar | Hamiltonian/spectral gap (OU/free field). | |

| Scalars | Coercivity/remainder (DSFL template). | |

| Scalar | Dissipation rate ( when used dynamically). | |

References

- Ponsot, B.; Teschner, J. Liouville bootstrap via harmonic analysis on a noncompact quantum group. arXiv 2000, arXiv:hep-th/9911110. [Google Scholar]

- Fock, V.; Goncharov, A. Cluster ensembles, quantization and the dilogarithm. Annales Scientifiques de l’École Normale Supérieure 2009, 42, 865–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.E.; Kashaev, R. A TQFT from quantum Teichmüller theory. Communications in Mathematical Physics 2014, 330, 887–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baseilhac, S.; Benedetti, R. Analytic families of quantum hyperbolic invariants. Algebraic & Geometric Topology 2014, 14, 1983–2063. [Google Scholar]

- Pachner, U. P.L. homeomorphic manifolds are equivalent by elementary shellings. European Journal of Combinatorics 1991, 12, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faddeev, L.D.; Kashaev, R.M. Quantum Dilogarithm. Modern Physics Letters A 1994, 9, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faddeev, L.D. Discrete Heisenberg–Weyl group and modular group. Letters in Mathematical Physics 1995, 34, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiyama, J. On the Projection of Norm One in W*-Algebras. Proceedings of the Japan Academy 1957, 33, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takesaki, M. Theory of Operator Algebras I; Springer, 2003.

- Fock, V.V.; Chekhov, L.O. Quantum Teichmüller space. Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 1999, 120, 1245–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveev, S.V. Algorithmic Topology and Classification of 3-Manifolds; Vol. 9, Algorithms and Computation in Mathematics, Springer, 2007.

- Kadison, R.V. A generalized Schwarz inequality and algebraic invariants for operator algebras. Annals of Mathematics 1952, 56, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiyah, M.F. Topological quantum field theories. Publications Mathématiques de l’IHÉS 1988, 68, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimofte, T.; Gaiotto, D.; Gukov, S. 3-Manifolds and 3d Indices. Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 2013, 17, 975–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadison, R.V.; Ringrose, J.R. Fundamentals of the Theory of Operator Algebras. Vol. I: Elementary Theory; Vol. 15, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, 1997.

- Kadison, R.V.; Ringrose, J.R. Fundamentals of the Theory of Operator Algebras. Vol. II: Advanced Theory; Vol. 16, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, 1997.

- Bhatia, R. Matrix Analysis; Vol. 169, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer: New York, 1997. [CrossRef]

- Halmos, P.R. Two Subspaces. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 1969, 144, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, 10th anniversary edition ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Petz, D. Monotonicity of Quantum Relative Entropy Revisited. Reviews in Mathematical Physics 2003, 15, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.; Kahan, W.M. The Rotation of Eigenvectors by a Perturbation. SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis 1970, 7, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banach, S. Sur les opérations dans les ensembles abstraits et leur application aux équations intégrales. Fundamenta Mathematicae 1922, 3, 133–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doob, J.L. Stochastic Processes; Wiley, 1953.

- Hoeffding, W. Probability inequalities for sums of bounded random variables. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1963, 58, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björck, Å.; Golub, G.H. Numerical Methods for Computing Angles between Linear Subspaces. Mathematics of Computation 1973, 27, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashaev, R.M. Quantization of Teichmüller spaces and the quantum dilogarithm. Letters in Mathematical Physics 1998, 43, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimofte, T.; Gaiotto, D.; Gukov, S. Gauge theories labelled by three-manifolds. Communications in Mathematical Physics 2011, 325, 367–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashaev, R.M. The Hyperbolic Volume of Knots from the Quantum Dilogarithm. Letters in Mathematical Physics 1997, 39, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.E.; Kashaev, R. A TQFT from Quantum Teichmüller Theory. Communications in Mathematical Physics 2014, 330, 887–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.; Kashaev, R. A TQFT from quantum Teichmüller theory. Communications in Mathematical Physics 2014, 330, 887–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | In practice: the orthogonal projection onto on collars; see the main text for the DSFL evolution justification. |

| 2 | In practice: the orthogonal projection onto on collars; see the main text for the DSFL evolution justification. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).