Submitted:

25 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Sampling Procedure

2.2. Yield and Growth Measurements

2.3. Biochemical Analysis

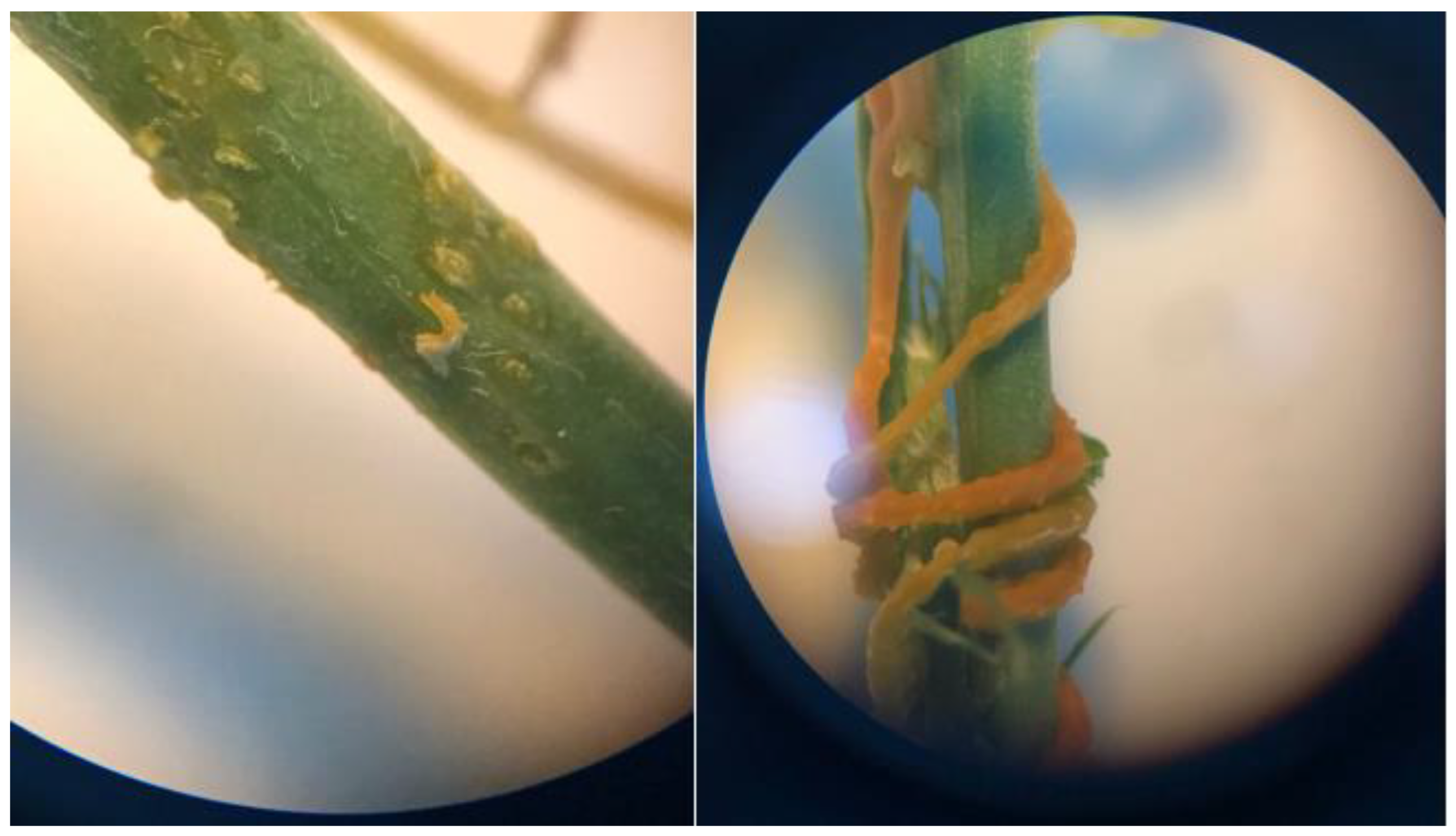

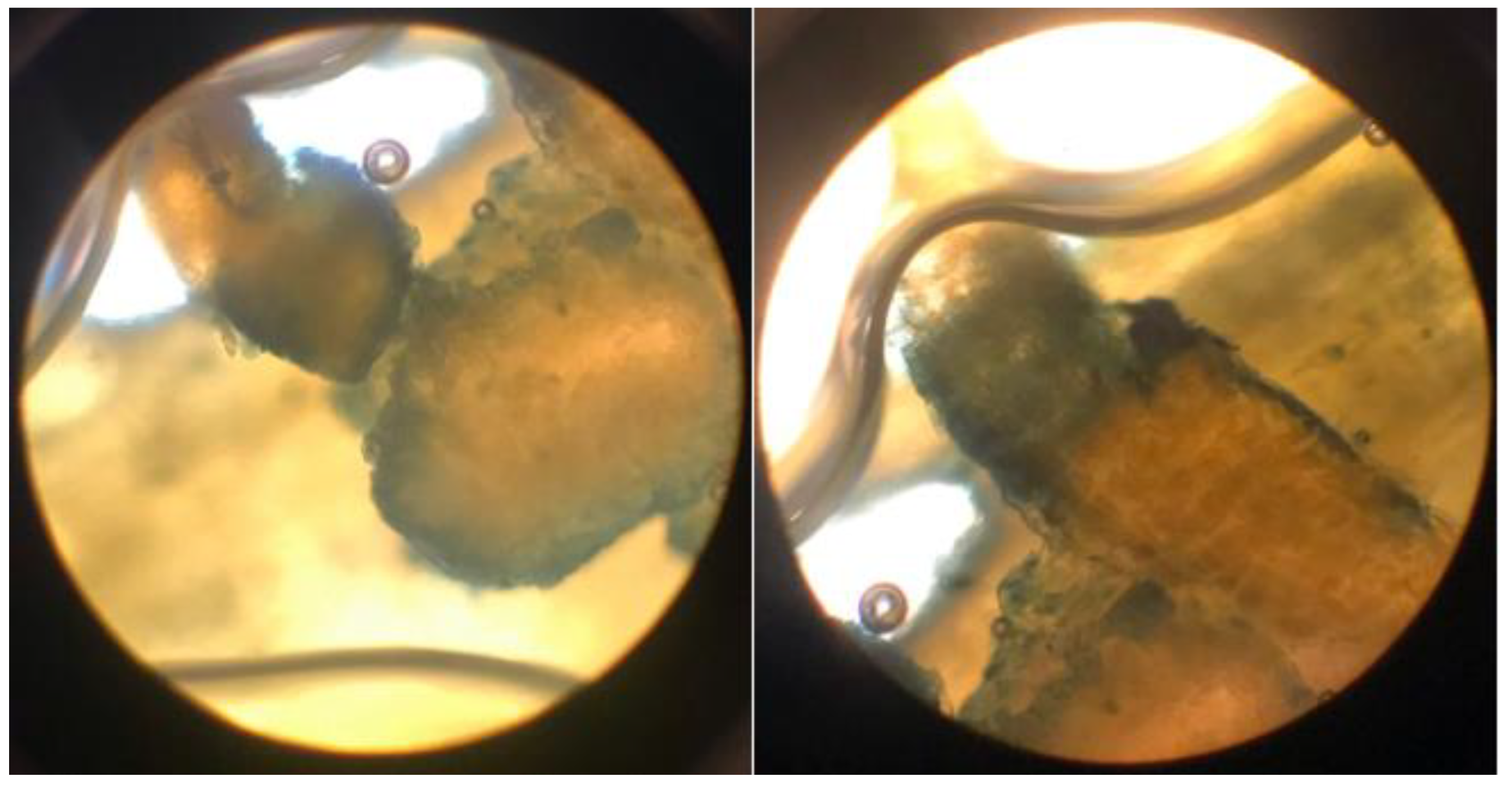

2.4. Histological Analysis of Cuscuta sp. Infection on Medicago sativa L.

2.5. Determination of DNA fragmentation in Medicago sativa and Cuscuta sp.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

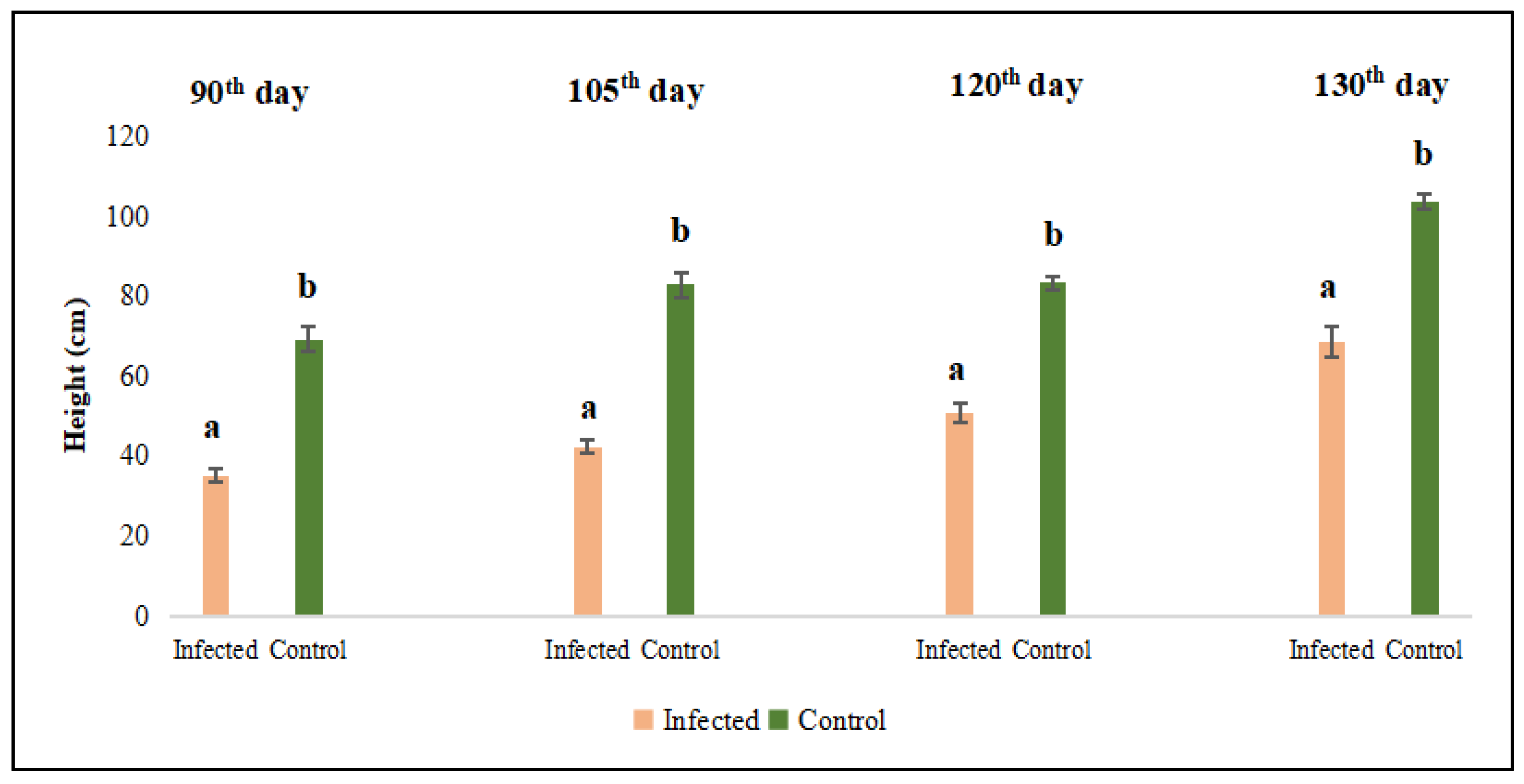

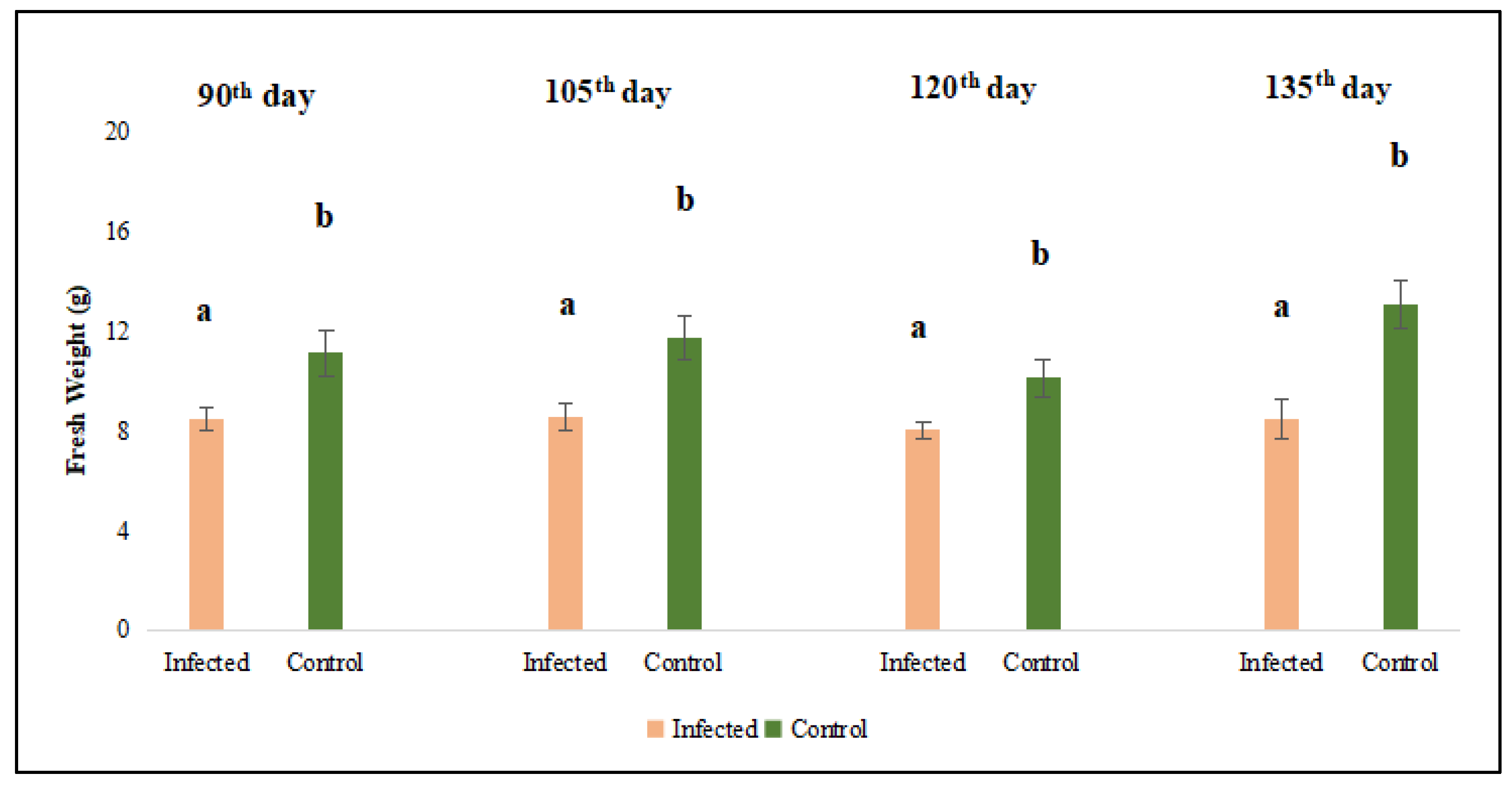

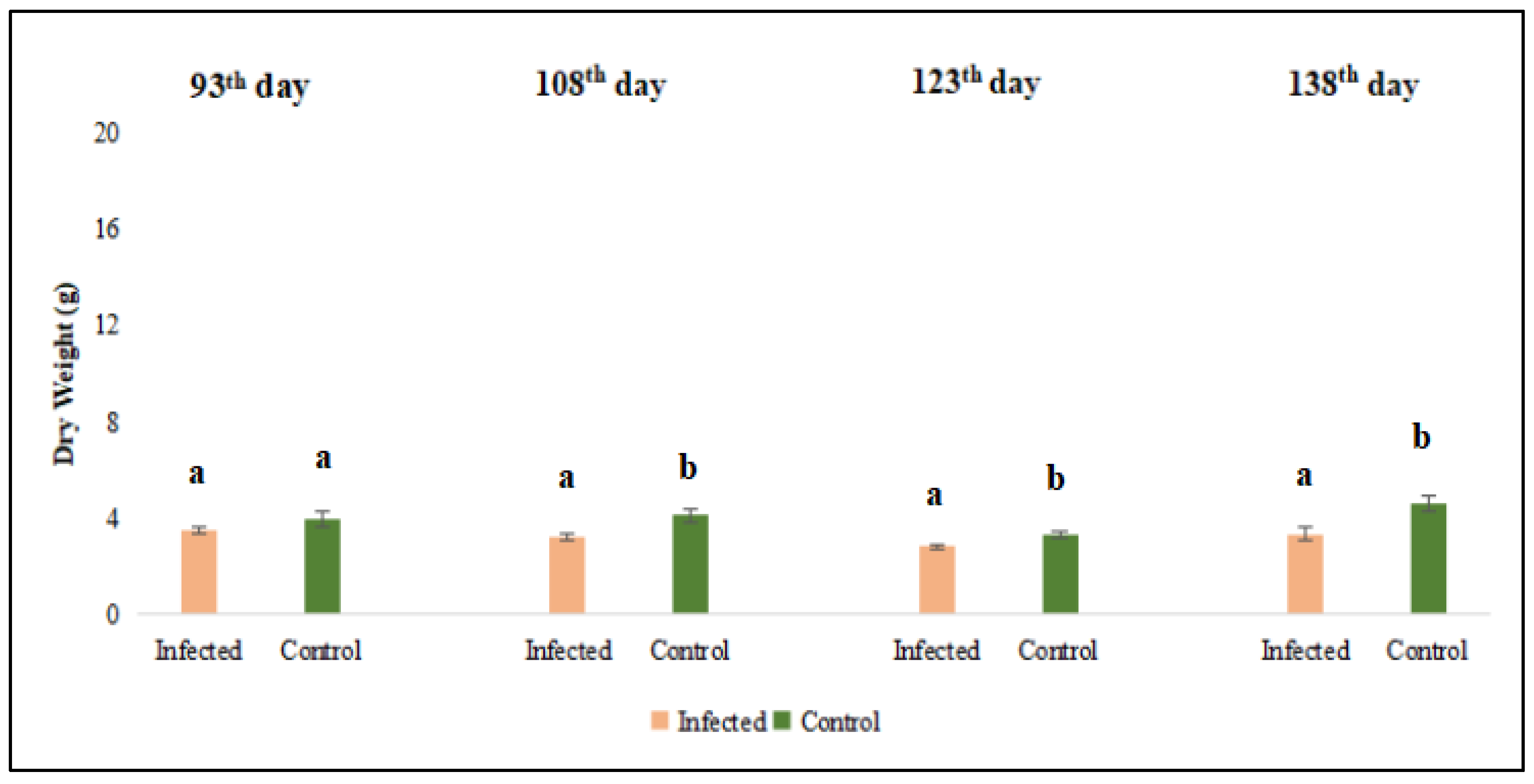

3.1. Yield and Growth Measurements

3.2. Biochemical Analysis

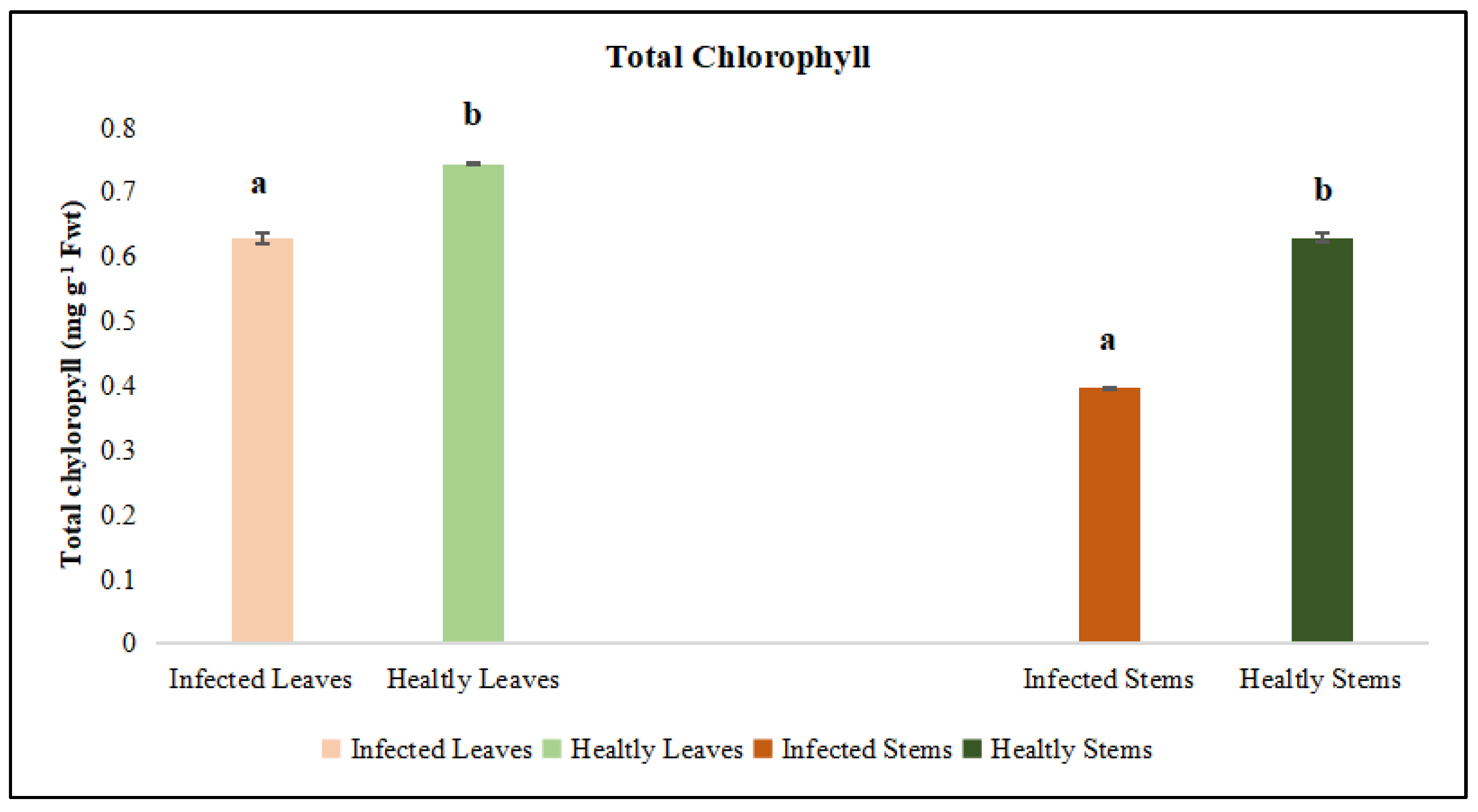

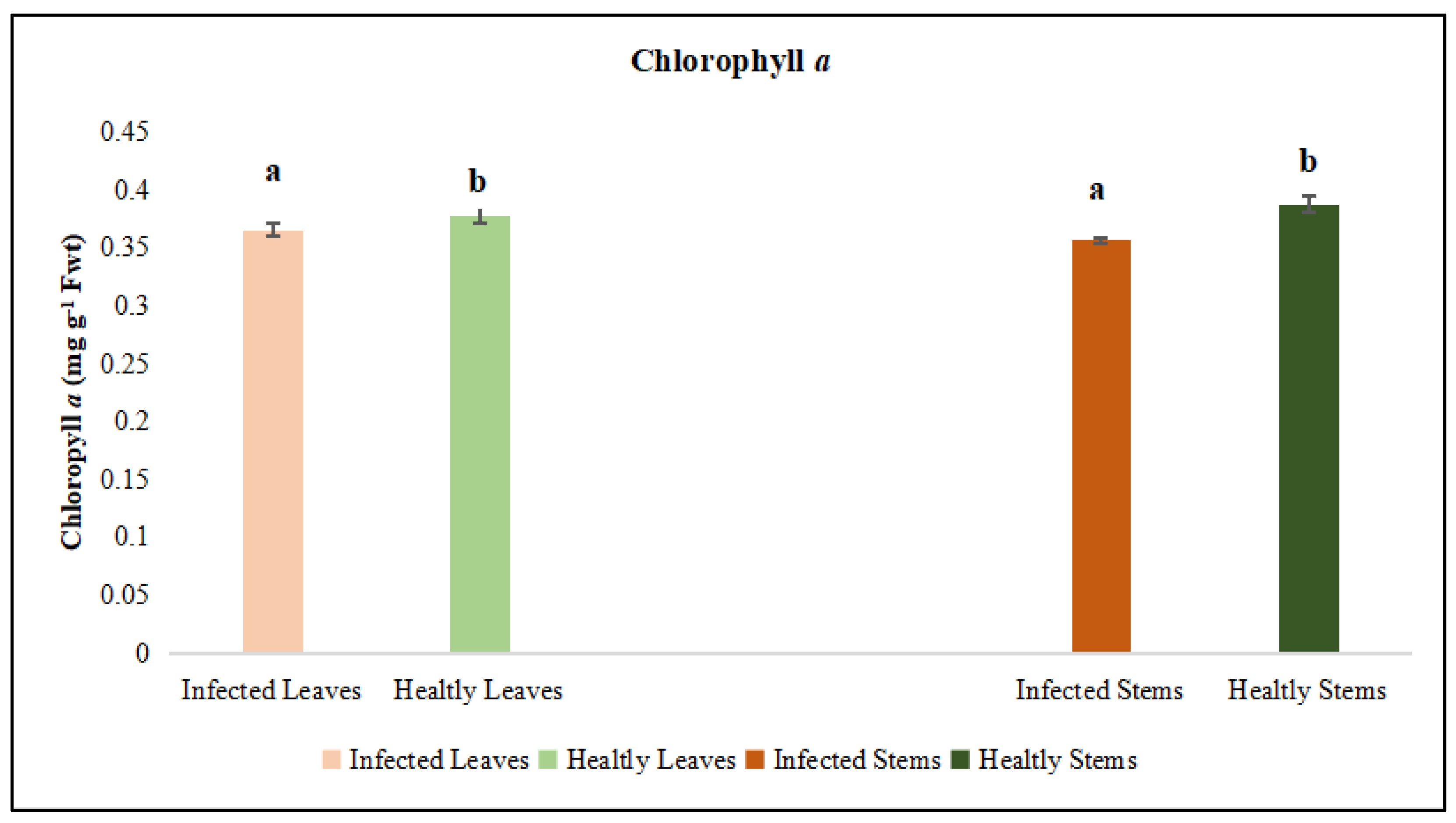

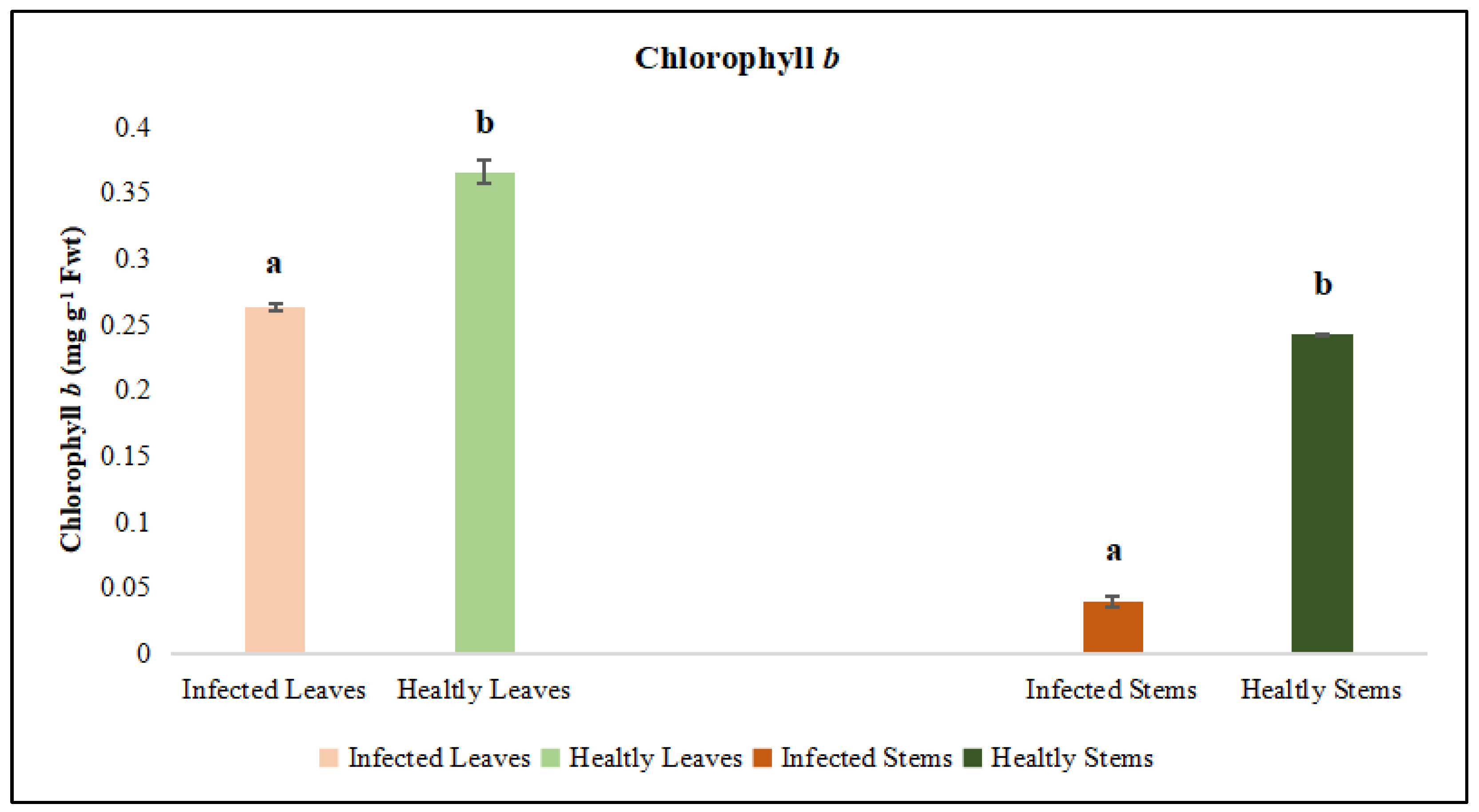

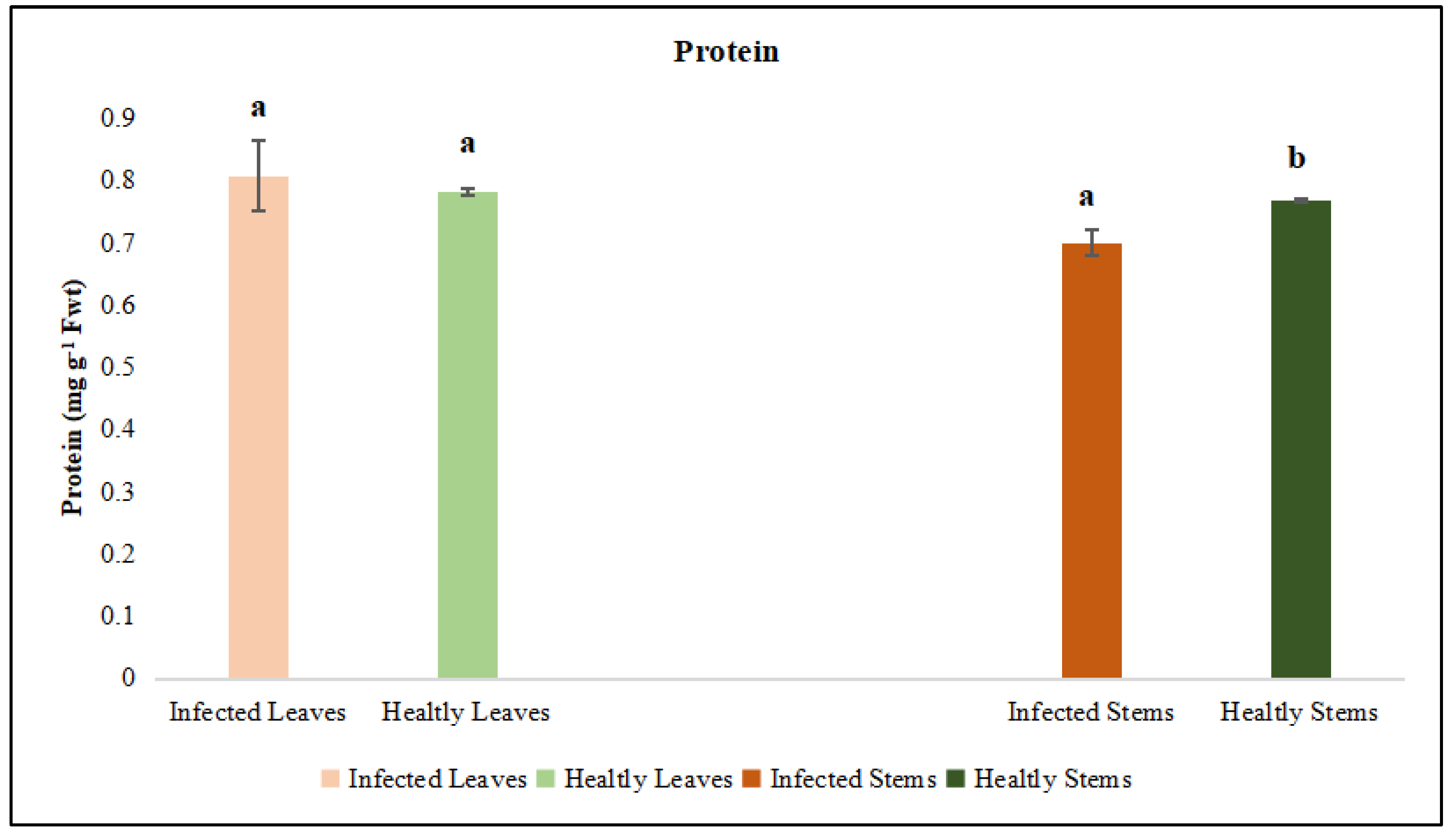

3.2.1. Chlorophyll and Protein Contents

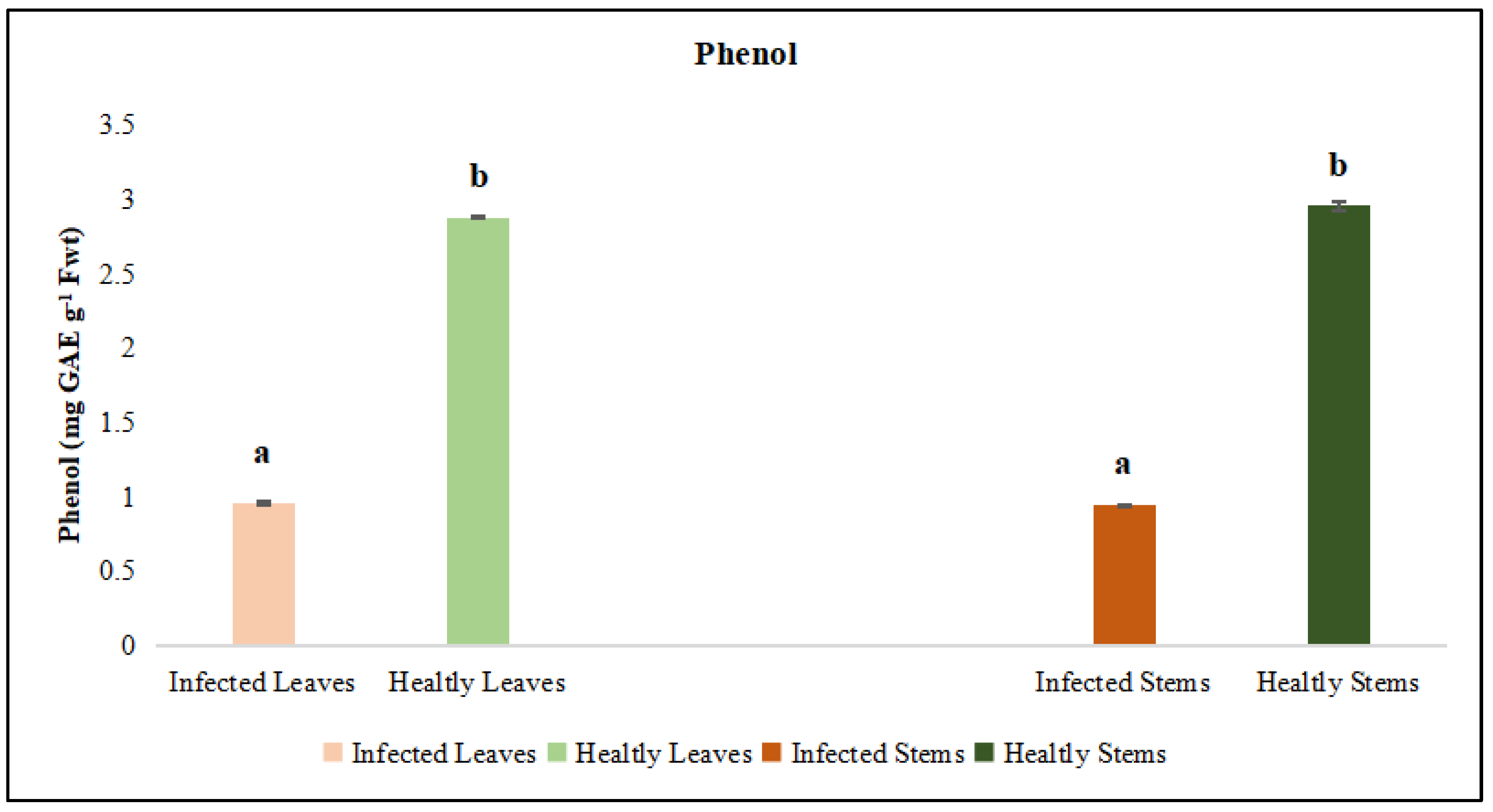

3.2.2. Quantitative Evaluation of Phenolic Compounds

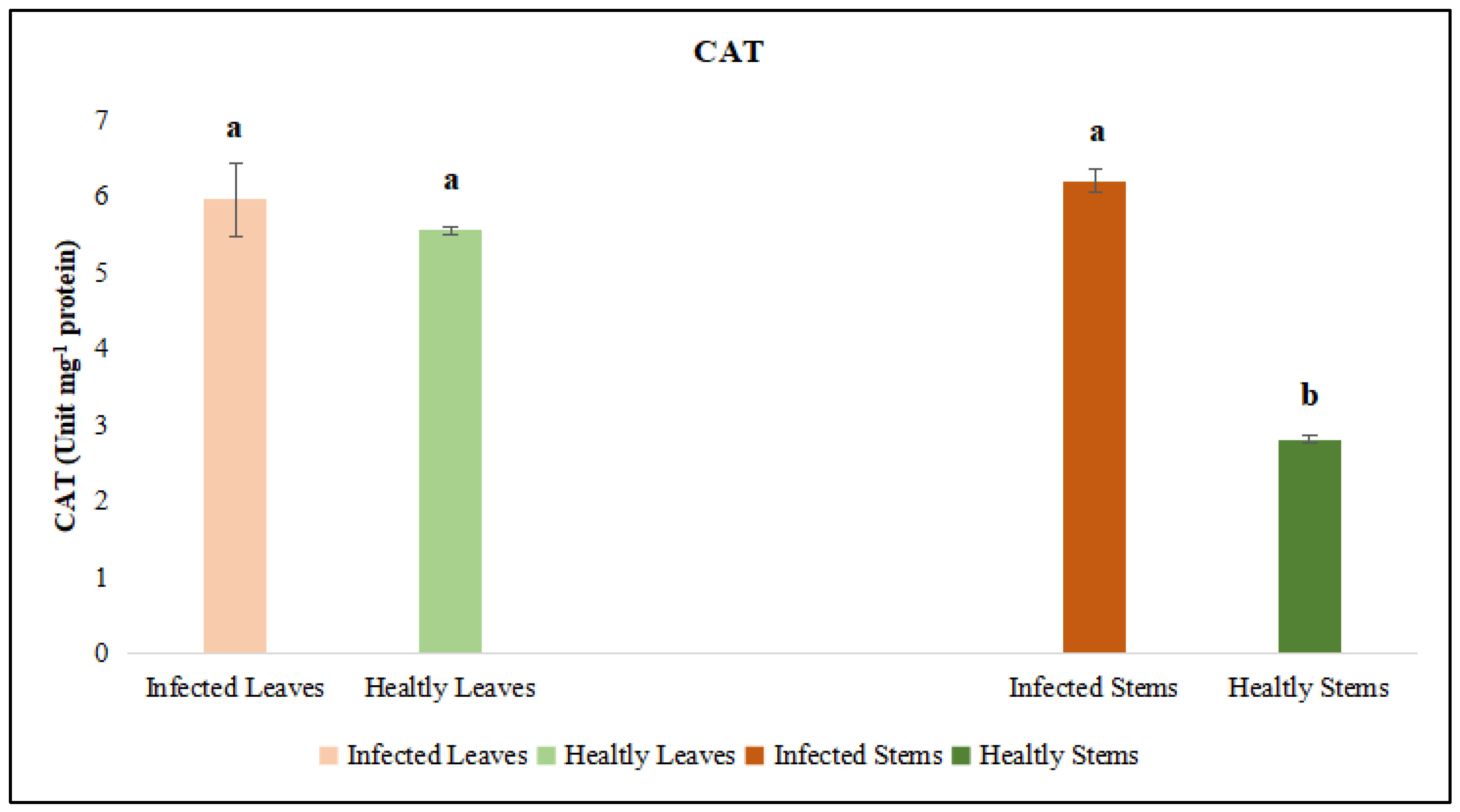

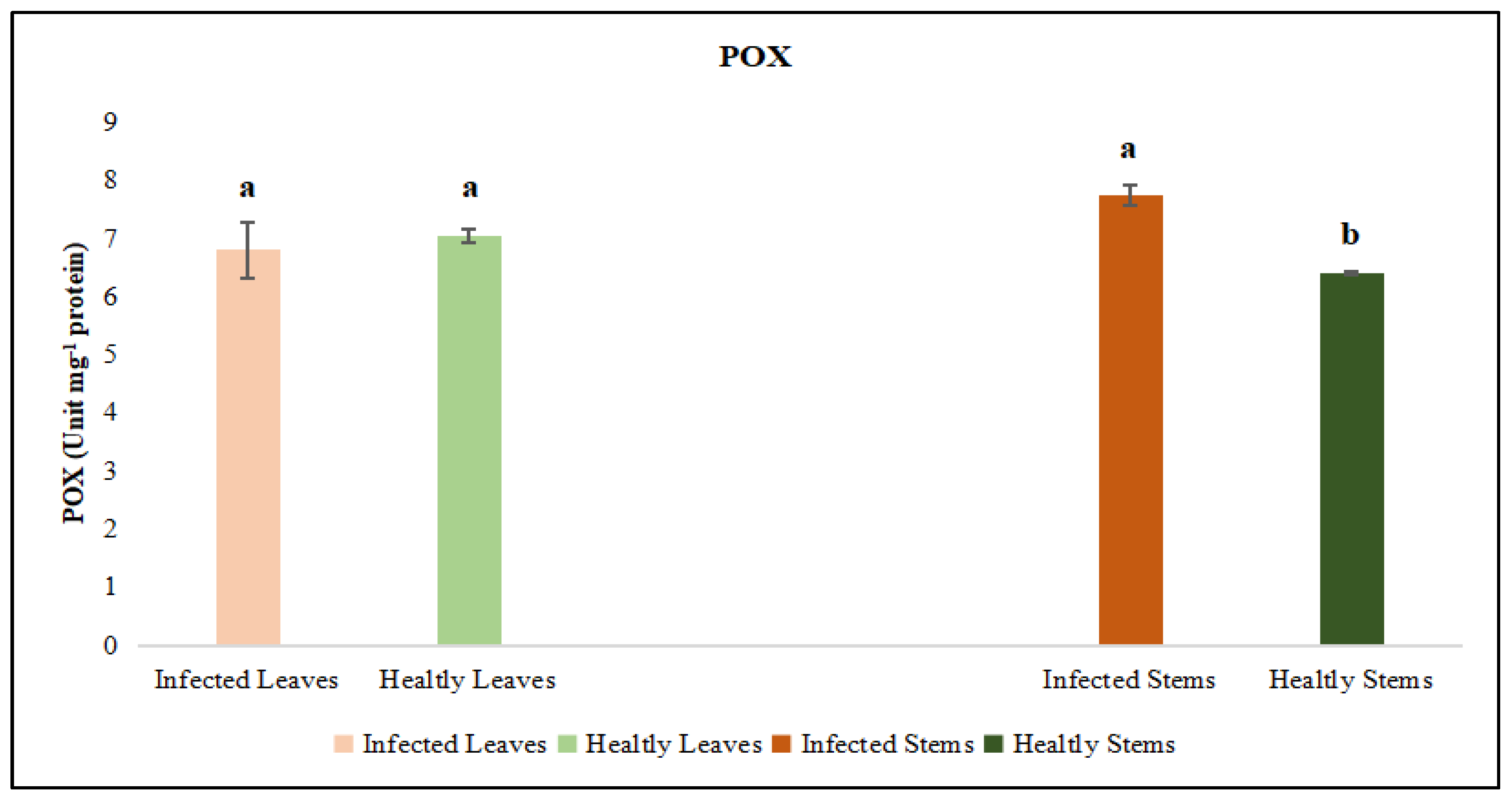

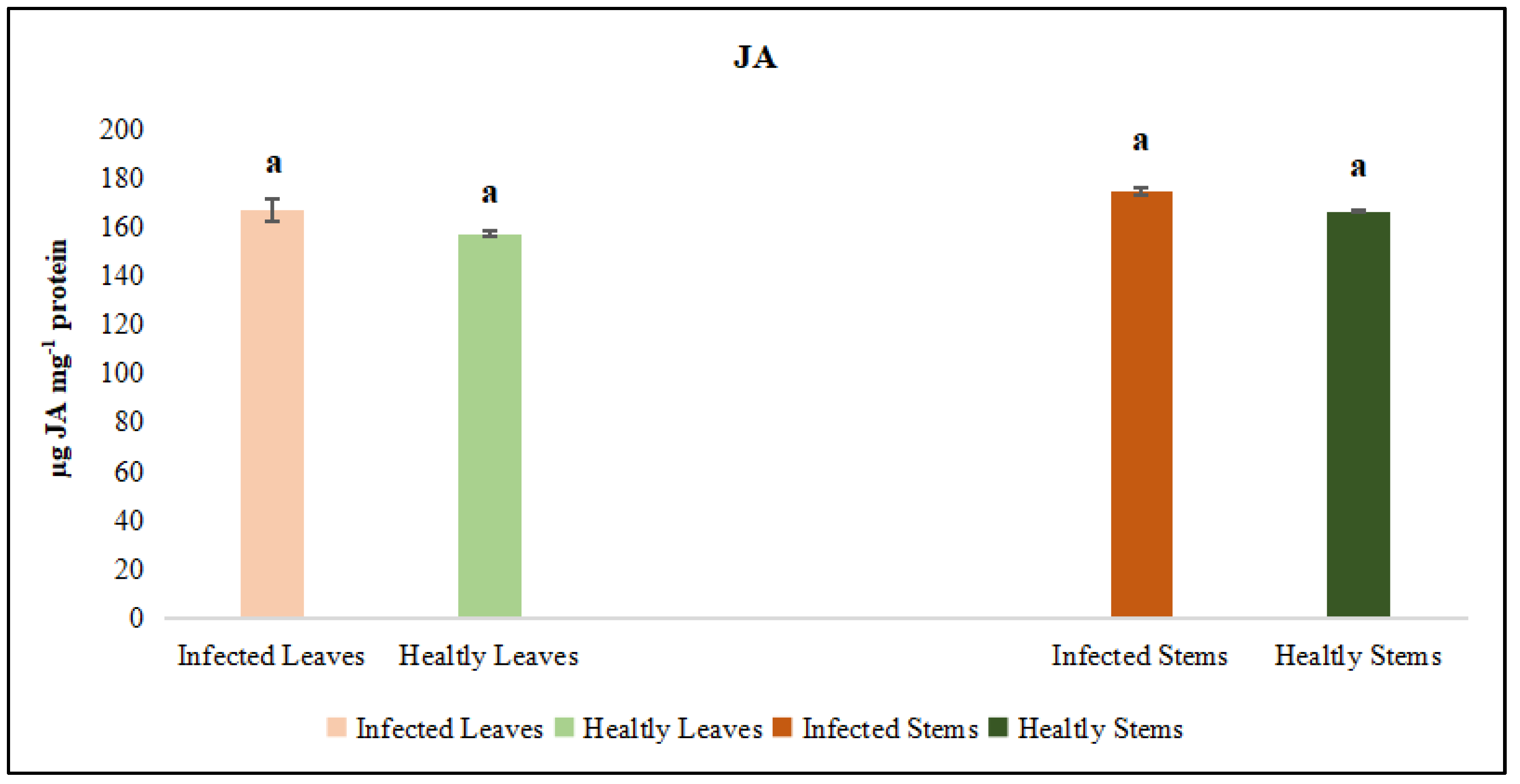

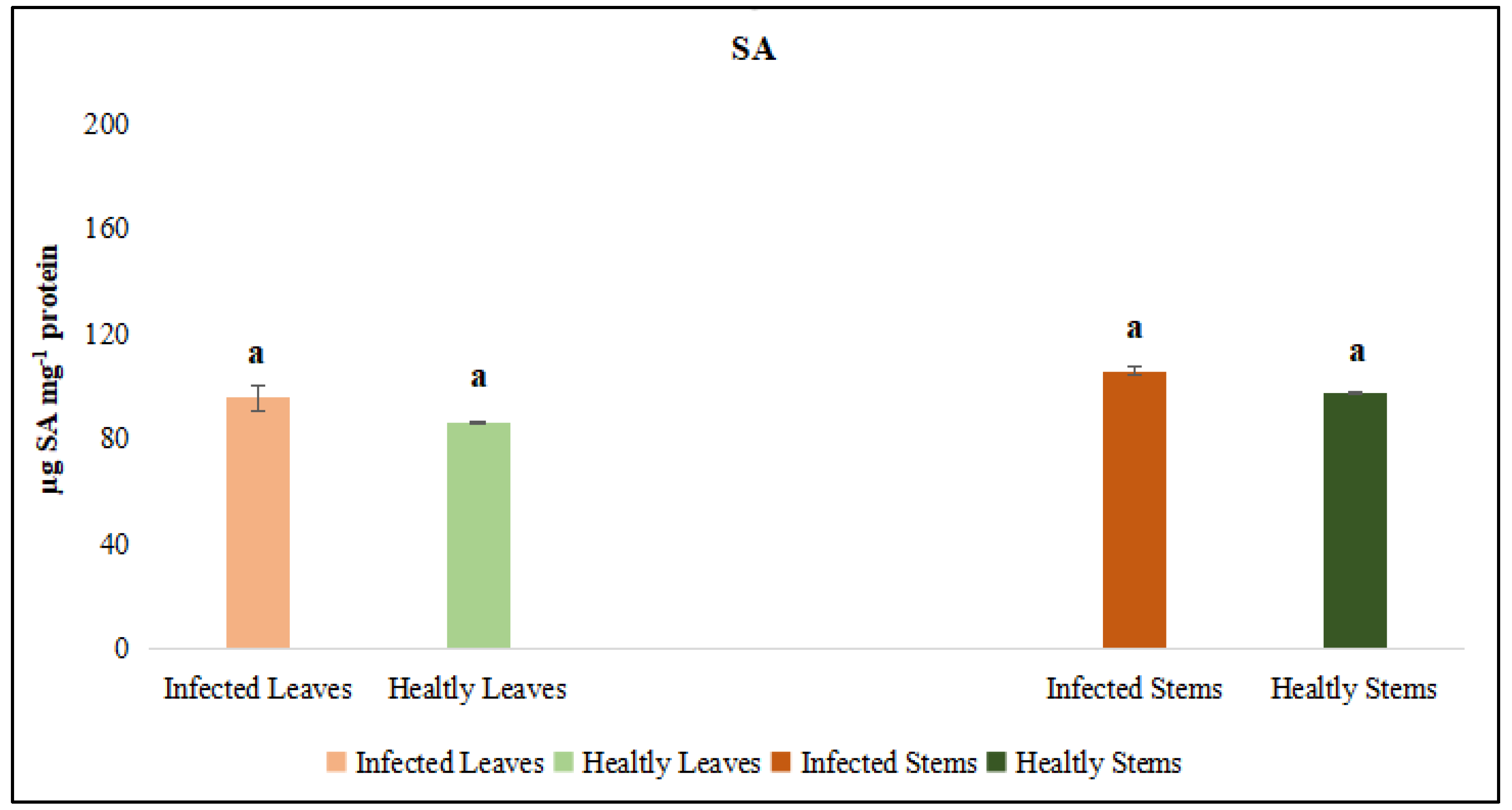

3.2.3. Quantitative Assessment of Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

3.2.4. Evaluation of Callose Responses Induced by Parasitic Infection in Plants

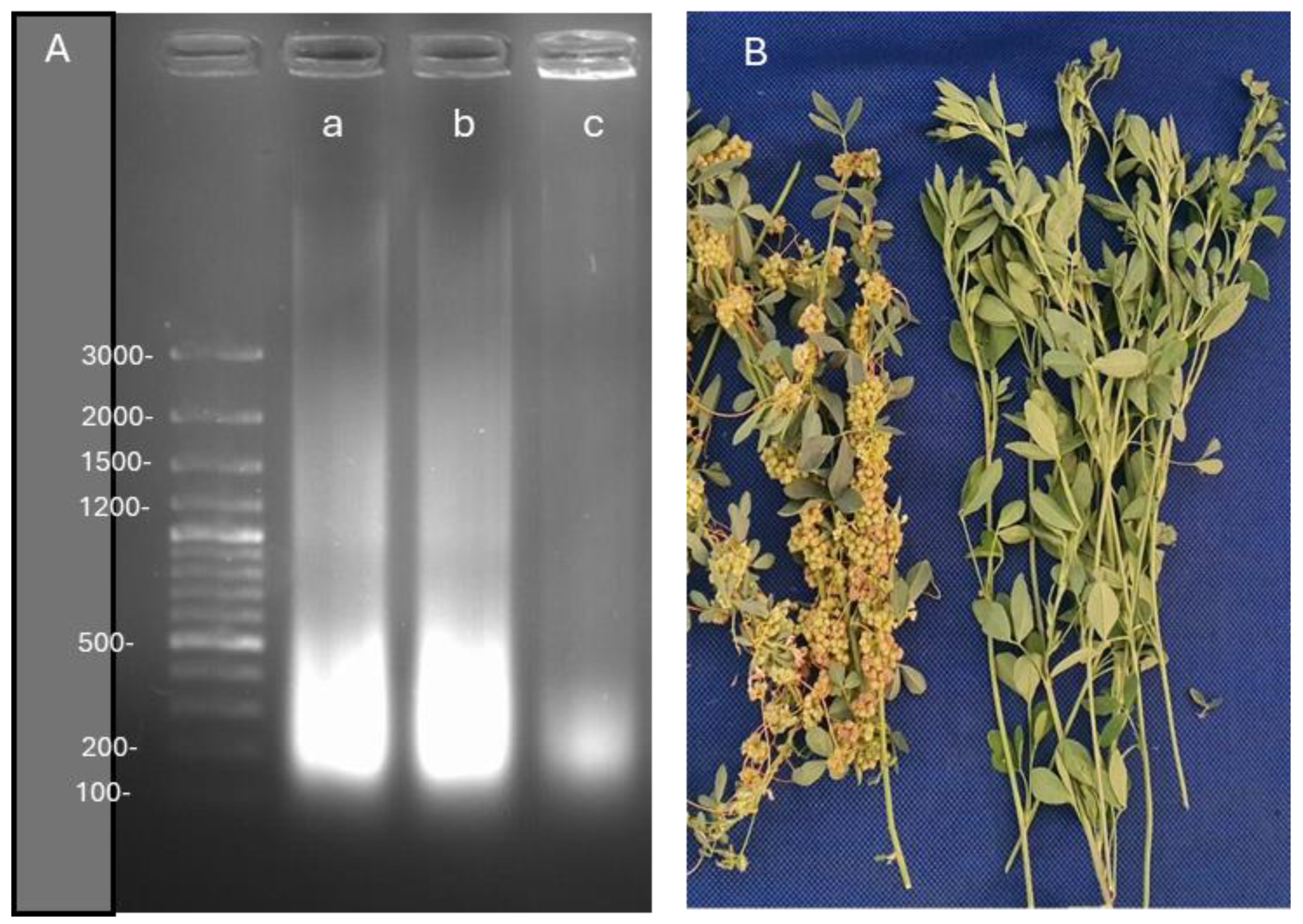

3.2.5. Evaluation of DNA damage in Medicago sativa infected with Cuscuta sp.

A-DNA fragmentation images, B-Infected and control lucerne plants with Cuscuta sp.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAT | Catalase |

| POX | Peroxidase |

| JA | Jasmonic acid |

| SA | Salicylic acid |

| Fwt | Fresh |

| Dwt | Dry |

| HGT | Horizontal Gene Transfer |

References

- Gaweł, E.; Grzelak, M. Protein from lucerne in animals supplement diet. Journal of Food Agriculture and Environment. 2014, 12, 314–319. [Google Scholar]

- Dechassa, N.; Regassa, B. Current Status, Economic Importance and Management of Dodders (Cuscuta spp.) of Important Crops. Advances in Life Science and Technology. 2021, 87, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masanga, J.; Mwangi, B.N.; Kibet, W.; Sagero, P.; Wamalwa, M.; Oduor, R.; Ngugi, M.; Alakonya, A.; Ojola, P.; Bellis, ES.; Runo, S. Physiological and ecological warnings that dodders pose an exigent threat to farmlands in Eastern Africa. Plant Physiology. 2021, 185, 1457–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokla, A.; Melnyk, CW. Developing a thief: Haustoria formation in parasitic plants. Developmental biology. 2018, 442, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Shen, G.; Wu, J. Jasmonic acid and salicylic acid transcriptionally regulate CuRe1 in cultivated tomato to activate resistance to parasitization by dodder Cuscuta australis. Plant Diversity. 2025, 47, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradkhani, S.; Jabbari, H. The effects of foliar spray of chitosan nanoparticles on tomato resistance against of Cuscuta campestris yunck. The Open Medicinal Chemistry Journal. 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saric-Krsmanovic, M.; Bozic, D.; Radivojevic, L.; Gajic Umiljendic, J.; Vrbnicanin, S. Response of alfalfa and sugar beet to field dodder (Cuscuta campestris Yunck.) parasitism: a physiological and anatomical approach. Canadian Journal of Plant Science. 2018, 99, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegenauer, V.; Slaby, P.; Körner, M.; Bruckmüller, J.A.; Burggraf, R.; Albert, I.; Kaiser, B.; Löffelhardt, B.; Droste-Borel. I.; Sklenar, J.; Menke, FLH.; Maček, B.; Ranjan, A.; Sinha, N.; Nürnberger, T.; Felix, G.; Krause, K.; Stahl, M.; Albert, M. The tomato receptor CuRe1 senses a cell wall protein to identify Cuscuta as a pathogen. Nature communications. 2020, 11, 5299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meighani, F.; Mamnoei, E.; Hatami, S.; Samadi-Kalkhoran, E.; Khalil-Tahmasebi, B.; Korres, NE.; Bajwa, AA. Chemical control of the field dodder (Cuscuta campestris) in new-seeded alfalfa (Medicago sativa). Agronomy. 2024, 14, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarić-Krsmanović, M.; Božić, D.; Radivojević, L.; Gajić-Umiljendić, J.; Vrbničanin, S. Impact of field dodder (Cuscuta campestris Yunk.) on physiological and anatomical changes in untreated and herbicide-treated alfalfa plants. Pesticidi i fitomedicina. 2016, 31, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnon, DL. Copper enzyme is isolated chloroplast: polyphenol oxidase in Beta vulgaries. Plant Physiol. 1949, 24, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakas, S.; Dikilitas, M.; Almaca, A.; Tipirdamaz, R. Physiological and biochemical responses of (Aptenia cordifolia) to salt stress and its remediative effect on saline soils. Appl. Ecol Environ. Res. 2020, 18, 1329–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, K.; Curtis, OF.; Levin, RE.; Wikowsky, R.; Ang, W. Prevention of verification associated with in vitro shoot culture of oregano (Origanum vulgare) by Pseudomonas spp. J. Plant Physiol. 1995, 147, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvıkorová, M.; Hrubcová, M.; Vägner, M.; Macháčková, I.; Eder, J. Phenolic acids and peroxidase activity in alfalfa (Medicago sativa) embryogenic cultures after ethephon treatment. Physiol. Plant. 1994, 91, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakas, S.; Dikilitaş, M.; Tıpırdamaz, R. Biochemical and molecular tolerance of Carpobrotus acinaciformis L. halophyte plants exposed to high level of NaCl stress. Harran, J. Agric. Food Sci. 2019, 23, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosevic, N.; Slusarenko, A J. Active oxygen metabolism and lignification in the hypersensitive response in bean. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 1996, 49, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakas, SD. Development of tomato growing ın soils differing in salt levels and effects of companion plants on some physiological parameters and soil remediation. PhD thesis, Harran University, Şanlıurfa-Turkey, 2013.

- Wang, X.S.; Han, J.G. Changes of proline content, activity, and active isoforms of antioxidative enzymes in two alfalfa cultivars under salt stress. Agric. Sci Chin. 2009, 8, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annigeri, S.; Pankaj Shakil, NA.; Kumar, J.; . Singh, K. Effect of jasmonate (jasmonic acid) foliar spray on resistance in tomato infected with root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita. Ann. Plant Prot Sci. 2011, 19, 446–450. [Google Scholar]

- Rainsford, KD. Aspirin and related drugs, 1rd ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bojko, M.; Kędra, M.; Adamska, A.; Jakubowska, Z.; Tuleja, M.; Myśliwa-Kurdziel, B. Induction and characteristics of callus cultures of the medicinal plant Tussilago farfara L. Plants. 2024, 13, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Liao, R.; Zhang, Y.; Arif, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, YWP. ; Wang, Z.; Han. B.; Song, C. Establishment of callus induction and plantlet regeneration systems of Peucedanum Praeruptorum dunn based on the tissue culture method. Plant Methods. 2024, 20, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, U.; Seemüller, E. Detection of DNA of plant pathogenic mycoplasmalike organisms by a polymerase chain reaction that amplifies a sequence of the 16 S rRNA gene. Phytopathology. 1992, 82, 828–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surapu, V.; Ediga, A.; Meriga, B. Salicylic Acid Alleviates Aluminum Toxicity in Tomato Seedlings (Lycopersicum esculentum Mill.) through Activation of Antioxidant Defense System and Proline Biosynthesis. Advances in Bioscience and Biotechnology. 2014, 5, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, B.; Ölmez, F.; Çapa, B.; Dikilitas, M. Defense Pathways of Wheat Plants Inoculated with Zymoseptoria tritici under NaCl Stress Conditions: An Overview. Life. 2024, 14, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minitab. https://www.minitab.com/en-us/products/minitab-solution-center/free-trial/ (3.10. 2025.

- Kaiser, B.; Vogg, G.; Fürst, UB.; Albert, M. Parasitic plants of the genus Cuscuta and their interaction with susceptible and resistant host plants. Frontiers in plant science. 2015, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, G.; Krause, K. The parasitic plant haustorium: a trojan horse releasing microRNAs that take control of the defense responses of the host. Non-coding RNA Investigation. 2018, 2. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wafula, EK.; Kim, G.; Shahid, S.; McNeal, JR.; Ralph, PE.; Timilsena, PR.; Yu, W.; Kelly, EA.; Zhang, H.; Person, TN.; Altman, NS.; Axtell, MJ.; Westwood, JH.; dePamphilis, CW. Convergent horizontal gene transfer and cross-talk of mobile nucleic acids in parasitic plants. Nature Plants. 2019, 5, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, S.; Kim, G.; Johnson, NR.; Wafula, E.; Wang, F.; Coruh, C.; Bernal-Galeano, V.; Phifer, T.; dePamphilis. CW.; Westwood, HT.; Axtell, MJ. MicroRNAs from the parasitic plant Cuscuta campestris target host messenger RNAs. Nature. 2018, 553, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förste, F.; Mantouvalou, I.; Kanngießer, B.; Stosnach, H.; Lachner, LAM. ; Fischer, K.; Krause, K. Selective mineral transport barriers at Cuscuta-host infection sites. Physiologia Plantarum. 2020, 168, 934–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Zhang, Z.; Bi, X.; Xue, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yuan, B.; Feng, Z.; Wang, J. A Putative effector Pst-18220, from Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici, participates in rust pathogenicity and plant defense suppression. Biomolecules. 2024, 14, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Li, S.; Mo, C.; Wang, G.; Xiao, X.; Xiao, Y. A novel Meloidogyne incognita effector Misp12 suppresses plant defense response at latter stages of nematode parasitism. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2016, 7, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaazer, CJH. ; Villacis-Perez, EA.; Chafi, R.; Van Leeuwen, T.; Kant, MR.; Schimmel, BC. Why do herbivorous mites suppress plant defenses? Frontiers in plant science, 2018, 9, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettenhausen, C.; Li, J.; Zhuang, H.; Sun, H.; Xu, Y.; Qi, J.; Sun, G.; Wang, L.; Baldwin, lanT. ; Wu, J. Stem parasitic plant Cuscuta australis (dodder) transfers herbivory-induced signals among plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2017, 114, E6703–E6709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegenauer, V.; Fürst, U.; Kaiser, B.; Smoker, M.; Zipfel, C.; Felix, G.; Albert, M. Detection of the plant parasite Cuscuta reflexa by a tomato cell surface receptor. Science. 2016, 353, 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saric-Krsmanovic, M.; Bozic, D.; Radivojevic, L.; Gajic Umiljendic, J.; Vrbnicanin, S. Response of alfalfa and sugar beet to field dodder (Cuscuta campestris Yunck.) parasitism: a physiological and anatomical approach. Canadian Journal of Plant Science. 2018, 99, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolswinkel, P. Complete inhibition of setting and growth of fruits of Vicia faba L. resulting from the draining of the phloem system by Cuscuta species. Acta botanica neerlandica. 1974, 23, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, A.; Ichihashi, Y.; Farhi, M.; Zumstein, K.; Townsley, B.; David-Schwartz, R.; Sinha, NR. De novo assembly and characterization of the transcriptome of the parasitic weed dodder identifies genes associated with plant parasitism. Plant physiology. 2014, 166, 1186–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagorchev, L.; Du, Z.; Shi, Y.; Teofanova, D.; Li, J. Cuscuta australis Parasitism-Induced Changes in the Proteome and Photosynthetic Parameters of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plants. 2022, 11, 2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zawaira, A.; Lu, Q.; Yang, B.; Li, J. Transcriptome analysis reveals defense-related genes and pathways during dodder (Cuscuta australis) parasitism on white clover (Trifolium repens). Frontiers in Genetics. 2023, 14, 1106936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boex-Fontvieille, E.; Daventure, M.; Jossier, M.; Zivy, M.; Hodges, M.; Tcherkez, G. Photosynthetic control of Arabidopsis leaf cytoplasmic translation initiation by protein phosphorylation. PLoS one. 2013, 8, e70692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayvacı, H.; Güldür, ME.; Dikilitas, M. Physiological and biochemical changes in lucerne (Medicago sativa) plants infected with ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma australasia’-related strain (16SrII-D Subgroup). The Plant Pathology Journal. 2022, 38, 146–10.5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrbničanin, SP.; Sarić-Krsmanović, MM.; Božić, DM. The effect of field dodder (Cuscuta campestris Yunck.) on morphological and fluorescence parameters of giant ragweed (Ambrosia trifida L.). Pesticides and Phytomedicine/Pesticidi i fitomedicina, 2013,1(1).

- Arce-Leal, Á.P.; Bautista, R.; Rodríguez-Negrete, E.A.; Manzanilla-Ramírez, M.Á.; Velázquez-Monreal, J.J.; Santos-Cervantes, M.E.; Méndez-Lozano, J.; Beuzón, C.R.; Bejarano, E.R.; Castillo, A.G.; et al. Gene Expression Profile of Mexican Lime (Citrus aurantifolia) Trees in Response to Huanglongbing Disease caused by Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, A.F.; Al-Abdulsalam, MA. Effect of field dodder (Cuscuta campestris Yuncker) on some legume crops. Scientific Journal of King Faisal University (Basic and Applied Sciences). 2004, 5, 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Heldt, HW.; Piechulla, B. Phenylpropanoids comprise a multitude of plant secondary metabolites and cell wall components. Plant biochemistry. 2011, 4, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runyon, J.B.; Mescher, M.C. , De Moraes, C. M. Plant defenses against parasitic plants show similarities to those induced by herbivores and pathogens. Plant signaling & behavior. 2010, 5, 929–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M.; Belastegui-Macadam, XM.; Bleischwitz, M.; Kaldenhoff, R. Cuscuta spp:“Parasitic plants in the spotlight of plant physiology, economy and ecology. In Progress in botany; Springer: Berlin, The Heidelberg, 2008; pp. 267–277. ISSN 978-3-540-72954-9. [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef, A.; Leon-Reyes, A.; Ritsema, T.; Verhage, A.; Den Otter, F. C.; Van Loon, LC.; Pieterse, CM. Kinetics of salicylate-mediated suppression of jasmonate signaling reveal a role for redox modulation. Plant physiology. 2008, 147, 1358–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assanga, SBI. ; Luján, LML.; Ruiz, JCG.; McCarty, MF.; Cota-Arce, JM.; Espinoza, CLL.; Salido, AAG.; Ángulo, DF. Comparative analysis of phenolic content and antioxidant power between parasitic Phoradendron californicum (toji) and their hosts from Sonoran Desert. Results in Chemistry. 2020, 2, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, LM.; Scandalios, JG. Catalase gene expression in response to auxin-mediated developmental signals. Physiologia Plantarum. 2002, 114, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraga, S.; Sasaki, K.; Ito, H.; Ohashi, Y.; Matsui, H. A large family of class III plant peroxidases. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2001, 42, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; Wang, Z.; Wei, C.; Amo, A.; Ahmed, B.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X. Phenylpropanoid pathway engineering: An emerging approach towards plant defense. Pathogens. 2020, 9, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.İ.; Jackson, E.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Salicylic acid and jasmonic acid in plant immunity. Horticulture Research. 2025, 12, uhaf082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xu, M.; Cai, X.; Han, Z.; Si, J.; Chen, D. Jasmonate signaling pathway modulates plant defense, growth, and their trade-offs. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022, 23, 3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, DD.; Fang, X.; Chen, XY.; Mao, YB. Plant specialized metabolism regulated by jasmonate signaling. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2019, 60, 2638–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbel, M.; Brini, F.; Sharma, A.; Landi, M. Role of jasmonic acid in plants: the molecular point of view. Plant Cell Reports. 2021, 40, 1471–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Seomun, S.; Yoon, Y.; Jang, G. Jasmonic acid in plant abiotic stress tolerance and interaction with abscisic acid. Agronomy. 2021, 11, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.; Kapoor, D. Salicylic acid: it's physiological role and Interactions. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology. 2018, 11, 3171–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, PAF. , de Carvalho, HH.; Costa, JH.; de Souza Miranda, R.; da Cruz Saraiva, KD.; de Oliveira, FDB.; Gomes Filho, D.; Prisco, JT.; Gomes-Filho, E. Salt acclimation in sorghum plants by exogenous proline: physiological and biochemical changes and regulation of proline metabolism. Plant Cell Rep. 2019, 38, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrier, RR. , Paul, M.; Vineetha, MV. Estimation of salicylic acid in Eucalyptus leaves using spectrophotometric methods. Genet Plant Physiol. 2013, 3, 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Poór, P.; Borbély, P.; Bódi, N.; Bagyánszki, M.; Tari, I. Effects of salicylic acid on photosynthetic activity and chloroplast morphology under light and prolonged darkness. Photosynthetica. 2019, 57, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, CA.; Marchetta, EJ.; Kim, JH.; Castroverde, CDM. Molecular regulation of the salicylic acid hormone pathway in plants under changing environmental conditions. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2023, 48, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berim, A.; Gang, DR. Accumulation of salicylic acid and related metabolites in Selaginella moellendorffii. Plants. 2022, 11, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Ravindran, P.; Kumar, PP. Plant hormone-mediated regulation of stress responses. BMC plant biology. 2016, 16, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Han, X.; Feng, D.; Yuan, D.; Huang, LJ. Signaling crosstalk between salicylic acid and ethylene/jasmonate in plant defense: do we understand what they are whispering? International journal of molecular sciences. 2019, 20, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M.; Axtell, MJ.; Timko, MP. Mechanisms of resistance and virulence in parasitic plant–host interactions. Plant physiology 2021, 185, 1282–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagawa, M.; Yokoyama, R. Current understanding of the role of the cell wall in Cuscuta parasitism. Plant Biology. 2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turan, P.; Şentürk, G.E.; Ercan, F. Cryopreservation triggers DNA fragmentation and ultrastructural damage in spermatozoa of oligoasthenoteratozoospermic men. Marmara Medical Journal. 2017, 30, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M.; Çavuşoğlu, K.; Yalçin, E.; Acar, A. DNA fragmentation and multifaceted toxicity induced by high-dose vanadium exposure determined by the bioindicator Allium test. Scientific Reports. 2023, 13, 8493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plitta-Michalak, B.P.; Ramos, A.; Stępień, D.; Trusiak, M.; Michalak, M. PERSPECTIVE: The comet assay as a method for assessing DNA damage in cryopreserved samples. CryoLetters. 2024, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, S.; Vlachonasios, KE.; Acar, O. , & Kaldis, A. The effect of salt stress on Arabidopsis thaliana and Phelipanche ramosa interaction. Weed Research. 2013, 53, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).