1. Introduction

Gender-responsive disaster management (GRDM) has emerged as a critical approach for enhancing disaster resilience and reducing the impact of disasters on communities. Research has continued to demonstrate that disasters affect men, women, and gender minorities in different ways due to social, economic, and cultural inequalities that pre-exists in various societies (Abdalla et al., 2024; Alaiyemola et al., 2023; Mukhopadhyay, 2011; Erman et al., 2021; Ejem et al., 2025; Ginige et al., 2009; Enarson et al., 2017; Bradshaw, 2015). As a result, researchers have found that mainstreaming gender perspectives into disaster risk reduction (DRR) and management is important to address these disparities and also leverage the unique knowledge, skills, and leadership capacities of women, minorities and marginalized groups to support community resilience (Ejem et al. 2025; Abdalla et al., 2024; Yarramsetty & Prasanna, 2024; Tobi et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2022; Roy & Mukherjee, 2024; Khalid et al., 2021).

Studies from diverse contexts—including Oman, Indonesia, Bangladesh, the Caribbean, and the Philippines—highlight that empowering women, mainstreaming gender in policy and practice, and ensuring inclusive participation in all phases of disaster management lead to more effective preparedness, response, and recovery (Abdalla et al., 2024; Brenner et al., 2024; Septanaya & Fortuna, 2023; Ramailis & Sakir, 2024; Hasan et al., 2019; Gaisie et al., 2021; Chisty et al., 2021). However, challenges remain, such as persistent patriarchal norms, insufficient policy implementation, and the need for intersectional approaches that include all gender identities (Zaidi & Fordham, 2021; Oktari et al., 2021; Gaillard et al., 2017; Bradshaw, 2015). This review synthesizes the latest evidence on how GRDM improves disaster resilience and reduces impact, identifies mechanisms and barriers, and highlights best practices and research gaps.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Gender Responsive Disaster Management

Disaster management is the organized efforts to prepare for, respond to, and recover from disasters, aiming to minimize harm and restore normalcy. The focus of disaster reduction is on the various strategies and actions that reduce the likelihood and impact of disasters, often through three distinct processes, namely early warning systems, risk assessment, and community education. On the other hand, disaster resilience refers to the capacity of individuals, communities, or systems to anticipate, withstand, adapt to, and recover from adverse events, stressing not just survival but also their ability to bounce back stronger. Gender-responsive disaster management recognizes that disasters affect men and women in different ways due to social, economic, and cultural factors, and seeks to address these disparities by actively involving women in planning, decision-making, and recovery processes (Abdalla et al., 2024; Ejem et al., 2025).

Research demonstrates that integrating gender perspectives is pivotal to achieving a more effective disaster risk reduction, as women’s knowledge, leadership, and adaptive skills are crucial for community resilience and recovery (Achmad et al., 2024; Abdalla et al., 2024; Yarramsetty & Prasanna, 2024; Erman et al., 2021; Brenner et al., 2024; Ramailis & Sakir, 2024; Septanaya & Fortuna, 2023; Inal et al., 2018). Nevertheless, traditional disaster management has been shown to often overlooks women’s needs and contributions, leading inadequate support and increased vulnerability for women, children, the aged and other vulnerable groups (Ejem et al., 2025; Yarramsetty & Prasanna, 2024; Achmad et al., 2024; Samiullah et al., 2015; Inal et al., 2018).

Gender mainstreaming, which is the process of ensuring policies and practices are sensitive to gender differences. has been shown to lessen disaster vulnerability and promote equality, but the snag is that implementation gaps remain at local and national levels (Sartorio & Davalos, 2025; Brenner et al., 2024; Ramailis & Sakir, 2024; Septanaya & Fortuna, 2023; Olonade et al., 2021). Empowering women through education, training, and participation in disaster planning not only protects vulnerable groups but also strengthens overall community resilience and supports broader development goals (Abdalla et al., 2024; Brenner et al., 2024; Achmad et al., 2024; Ramailis & Sakir, 2024; Septanaya & Fortuna, 2023; Sartorio & Davalos, 2025; Owoeye, 2021).

2.2. Disaster Resilience

Disaster resilience refers to the ability of individuals, communities, and systems to prepare for, respond to, and recover from disasters while minimizing negative impacts and adapting to future risks. The literature highlights that resilience is a multidimensional concept, evolving from simply “bouncing back” after a disaster to encompassing adaptation, transformation, and proactive risk management strategies such as “building back better” and “bouncing forward” (Graveline & Germain, 2022; Parker, 2020). Key components of disaster resilience include social capital, economic stability, governance, infrastructure, human capital, and the empowerment of marginalized groups, with social networks playing a central role in reducing disaster impacts and enhancing recovery (Mayer, 2019; Khan et al., 2022). Evidence in existing studies has shown that measurement of resilience has advanced through the development of indices and quantitative models, yet there are still subsisting challenges regarding validating these tools and ensuring they accurately reflect real-world outcomes (Zobel & Khansa, 2014; Khan et al., 2022; Bakkensen et al., 2017; Zobel, 2011).

2.3. Theoretical Framework: Disaster Crunch Model

The disaster crunch model, also known as the Pressure and Release (PAR) model, is a commonly used framework for understanding how disasters arise from the interaction between hazards and underlying vulnerabilities. The model shows that vulnerability is rooted in socio-economic and political processes and must be addressed to reduce the risk of disaster. The assumption is that disaster happens only when a hazard affects vulnerable people. A natural phenomenon by itself is not a disaster and a vulnerable people without a trigger event do not experience a disaster. Disaster only happens when hazards (trigger event) meets vulnerability (unsafe conditions) (Ejem et al., 2024).

The disaster crunch model conceptualizes disasters as the outcome of increasing “pressure” from root causes (such as poverty, poor governance, and lack of access to resources), dynamic pressures (like rapid urbanization or population growth), and unsafe conditions (such as living in hazard-prone areas), which together “crunch” against a triggering hazard event to produce disaster impacts (Saha, 2014; Smyth & Hai, 2012).

The disaster crunch model has also been adapted to emphasize gendered vulnerabilities, recognizing that women and men experience disasters differently due to social roles and inequalities, and calling for disaster risk reduction strategies that address these differences (Smyth & Hai, 2012). Overall, the disaster crunch model remains a foundational tool for analyzing disaster risk, guiding both research and practical interventions to reduce vulnerability and build resilience (Saha, 2014; Smyth & Hai, 2012; Elwood, 2009).

3. Methods

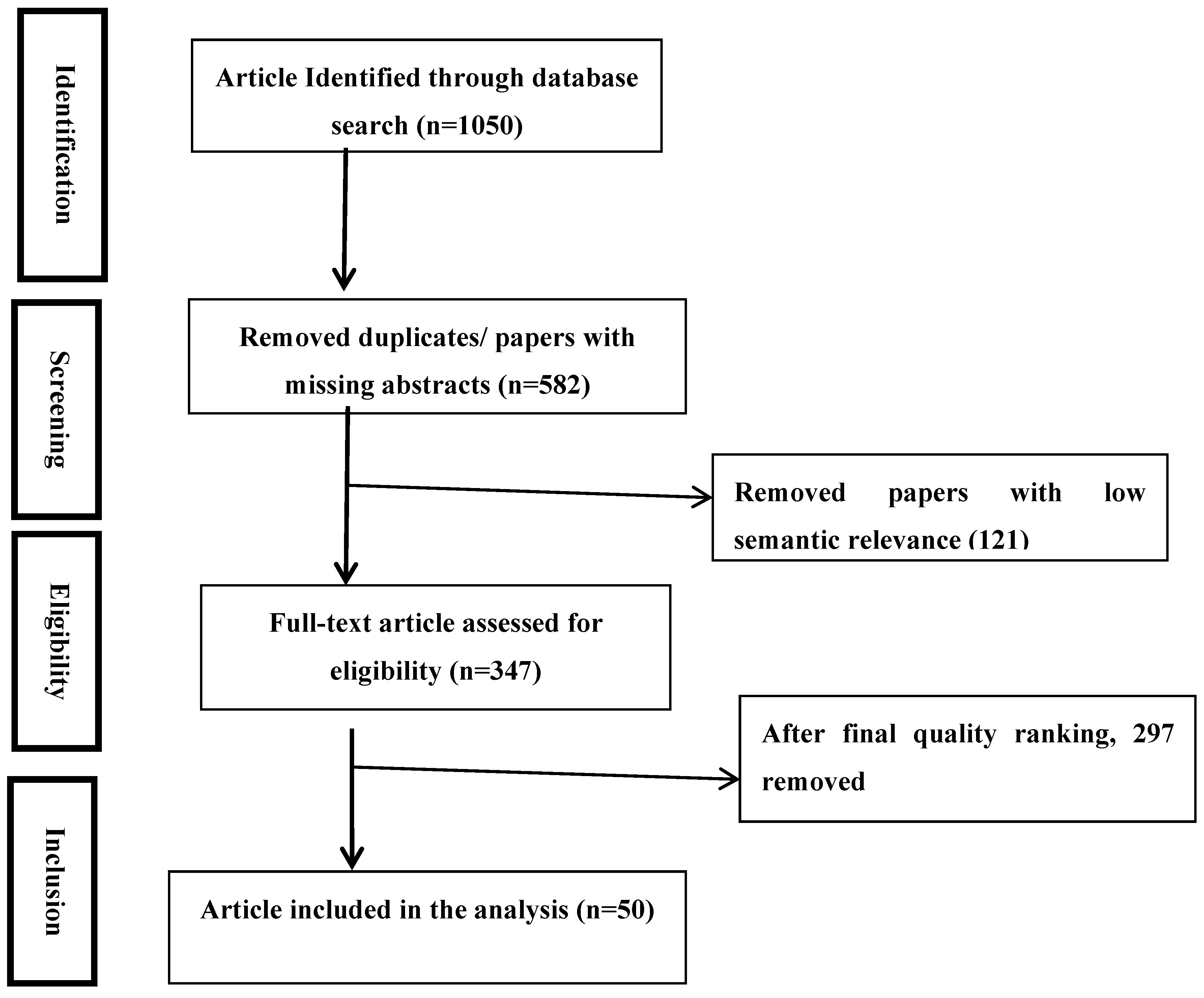

A comprehensive search was conducted on free and accessible databases such as Semantic Scholar and PubMed. The search strategy illustrated in

Figure 1 involved 21 targeted queries grouped into seven thematic areas, identifying 1,050 potentially relevant papers. After de-duplication and relevance screening, 468 papers were screened, 347 were deemed eligible, and the top 50 most relevant and high-quality papers were included in this review. A total of 21 unique searches were executed, focusing on gender, disaster management, resilience, and related mechanisms, with inclusion based on relevance, recency, and methodological rigor.

4. Results

4.1. Attributes of the Papers

The included studies span a wide range of geographies (Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, Middle East, and global reviews), methodologies (qualitative case studies, quantitative surveys, policy analyses, systematic reviews), and disaster types (cyclones, floods, earthquakes, pandemics, and climate-related hazards) (Abdalla et al., 2024; Yarramsetty & Prasanna, 2024; Septanaya & Fortuna, 2023; Tobi et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2022; Hasan et al., 2019; Erman et al., 2021; Gaisie et al., 2021; Chisty et al., 2021; Khalid et al., 2021). Many papers focus on women’s roles, but several also address broader gender and intersectionality issues, including the experiences of gender minorities (Neelima & Thomas, 2022; Gaillard et al., 2017; Diab, 2024).

4.2. Impact of Gender-Responsive Approaches

Improved resilience and reduced impact

Evidence from 11 of the studies confirm that GRDM consistently leads to better disaster preparedness, response, and recovery outcomes. Empowering women and ensuring their participation in DRR planning and implementation enhances community resilience and reduces vulnerability (Abdalla et al., 2024; Yarramsetty & Prasanna, 2024; Brenner et al., 2024; Ramailis & Sakir, 2024; Tobi et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2022; Ginige et al., 2009; Recovery & Headquarters, 2009; Roy & Mukherjee, 2024; Chisty et al., 2021; Chineka et al., 2019).

Addressing gendered vulnerabilities

Evidence from 9 of the studies shows that disasters often exacerbate existing gender inequalities, with women and marginalized groups facing higher risks and barriers to recovery. GRDM helps identify and address these vulnerabilities, such as lack of access to resources, increased risk of gender-based violence, and exclusion from decision-making (Mukhopadhyay, 2011; Hasan et al., 2019; Erman et al., 2021; Kadir, 2021; Gaisie et al., 2021; Nongmaithem, 2024; Bradshaw, 2015; Khalid et al., 2021; Gul et al., 2024).

Policy and institutional change

Research evidence shows that National and international frameworks (e.g., Sendai Framework) increasingly recognize the need for gender inclusion, but implementation gaps persist. Effective GRDM requires not just policy statements but concrete actions, such as gender-disaggregated data, targeted training, and inclusive standard operating procedures (Zaidi & Fordham, 2021; Oktari et al., 2021; Hasan et al., 2019; Recovery & Headquarters, 2009; Rimbawan & Nurhaeni, 2024).

4.3. Mechanisms and Best Practices

Women’s leadership and participation

Evidence from the literature shows that women’s involvement in disaster planning, early warning systems, and community-based risk management leads to more effective and equitable outcomes (Abdalla et al., 2024; Yarramsetty & Prasanna, 2024; Ramailis & Sakir, 2024; Lee et al., 2022; Anastasia & Nabilla, 2025; Sartorio & Davalos, 2025; Roy & Mukherjee, 2024; Amaratunga & Haigh, 2021; Alfarizi et al., 2023).

Intersectional and inclusive approaches

It was clear from the studies that addressing the needs of all genders – including sexual and gender minorities – ensures that no group is left behind and that resilience strategies are truly comprehensive (Neelima & Thomas, 2022; Gaillard et al., 2017; Diab, 2024).

Capacity building and education

Training education, and empowerment initiatives for women and marginalized groups are key to building adaptive capacity and resilience (Achmad et al., 2024; Brenner et al., 2024; Tobi et al., 2023; Yumarni et al., 2021; Rimbawan & Nurhaeni, 2024; Khalid et al., 2021).

4.4. Barriers and Critiques

Persistent patriarchal norms

Research shows that deep-rooted gender norms and power structures often limit the effectiveness of GRDM, especially where women’s participation is tokenistic or procedural rather than substantive (Septanaya & Fortuna, 2023; Oktari et al., 2021; Gaillard et al., 2017; Sartorio & Davalos, 2025; Bradshaw, 2015).

Implementation gaps

Evidence from 4 of the studies shows that many policies acknowledge gender but lack mechanisms for meaningful inclusion, monitoring, and accountability (Zaidi & Fordham, 2021; Hasan et al., 2019; Mardialina et al., 2024; Recovery & Headquarters, 2009).

Need for context-specific solutions

The reviewed bodies of literature confirm that one-size-fits-all approaches are less effective; local context, culture, and intersectional identities must be considered (Lee et al., 2022; Gaillard et al., 2017; Maobe, 2021; Tickamyer & Kusujiarti, 2020; Seira & Kurniati, 2020; Forbes-Biggs, 2020).

5. Discussion

The research strongly supports the claim that gender-responsive disaster management improves resilience and reduces disaster impact, especially when it moves beyond token inclusion to meaningful participation and empowerment of women and marginalized groups (Abdalla et al., 2024; Mukhopadhyay, 2011; Lee et al., 2022; Ginige et al., 2009; Enarson et al., 2017; Recovery & Headquarters, 2009; Roy & Mukherjee, 2024; Bradshaw, 2015; Chineka et al., 2019). High-quality evidence from diverse contexts shows that GRDM leads to more effective preparedness, response, and recovery, and helps address the root causes of gendered vulnerability (Abdalla et al., 2024; Yarramsetty & Prasanna, 2024; Brenner et al., 2024; Ramailis & Sakir, 2024; Tobi et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2022; Ginige et al., 2009; Recovery & Headquarters, 2009; Roy & Mukherjee, 2024; Chisty et al., 2021; Chineka et al., 2019). However, the quality of implementation varies: some interventions remain superficial, focusing on procedural gender mainstreaming without challenging underlying power structures or addressing intersectionality (Septanaya & Fortuna, 2023; Oktari et al., 2021; Gaillard et al., 2017; Sartorio & Davalos, 2025; Bradshaw, 2015). There is also a need for more robust monitoring, evaluation, and context-specific adaptation of GRDM strategies (Zaidi & Fordham, 2021; Hasan et al., 2019; Mardialina et al., 2024; Recovery & Headquarters, 2009).

The implication of this research is that as disasters become more frequent and severe due to climate change, ensuring that DRR and management strategies are gender-responsive are matters of equity, effectiveness and sustainability (Erman et al., 2021; Ginige et al., 2009; Enarson et al., 2017; Recovery & Headquarters, 2009; Bradshaw, 2015).

The evidence base is strong for the benefits of GRDM, but further research is needed on intersectionality, long-term outcomes, and the experiences of gender minorities (Neelima & Thomas, 2022; Gaillard et al., 2017; Diab, 2024).

6. Conclusions

The literature review provides robust evidence that gender-responsive disaster management improves disaster resilience and reduces impact, especially when it involves meaningful and inclusive implementation. However, persistent barriers, implementation gaps, and the need for intersectional approaches remain.

The research gap matrix in

Table 1 below highlights the research coverage and gaps by topic and study attributes on gender-responsive disaster management, and this situates areas of need for future research attention.

Despite the evidence that gender-responsive disaster management is a proven strategy for improving resilience and reducing disaster impact, further research and action are needed to address persistent gaps and ensure truly inclusive and effective disaster risk reduction.

References

- Abdalla, S., Ramadan, E., and Mamari, W. (2024). Enhancing gender-responsive resilience: The critical role of women in disaster risk reduction in Oman. Progress in Disaster Science. [CrossRef]

- Achmad, Z., Nuryananda, P., Haq, J., Budiwitjaksono, G., and Agustina, Z. (2024). The Importance of Gender-Based Standard Operating Procedures for Disaster Management in East Java. Jurnal Sosial Humaniora. [CrossRef]

- Alaiyemola, A. O., Akanmode, O., Iwelumor, O., & Ake, M. (2023, April). Re-Appraising Women to Women Discrimination Towards Attaining Gender Equality. In 2023 International Conference on Science, Engineering and Business for Sustainable Development Goals (SEB-SDG) (Vol. 1, pp. 1-4). IEEE.

- Alfarizi, M., Nada, S., Isti’adatul, F., and Alia, F. (2023). Integrating gender mainstreaming in disaster risk reduction through providing geospatial information to create community resilience in Muntuk Village, Bantul Regency. E3S Web of Conferences. [CrossRef]

- Amaratunga, D., and Haigh, R. (2021). Yumarni, Tri and Amaratunga, Dilanthi Resource capability for local government in mainstreaming gender into disaster risk reduction: evidence from Indonesia.

- Anastasia, A., and Nabilla, F. (2025). Forest fire disasters and ecological crisis: Impacts on women. ASEAN Natural Disaster Mitigation and Education Journal. [CrossRef]

- Bakkensen, L., Fox-Lent, C., Read, L., and Linkov, I. (2017). Validating Resilience and Vulnerability Indices in the Context of Natural Disasters. Risk Analysis, 37. [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G., Chen, S., Bagrodia, R., and Galatzer-Levy, I. (2023). Resilience and Disaster: Flexible Adaptation in the Face of Uncertain Threat. Annual review of psychology. [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, S. (2015). Engendering development and disasters... Disasters, 39 Suppl 1, S54-75. [CrossRef]

- Brenner, R., Arias, C., and Schmitt, A. (2024). Gender inclusive planning for disasters: Strategic planning to build adaptive capacity and resilience. Journal of emergency management, 23 2, 201-210. [CrossRef]

- Brenner, R., Arias, C., and Schmitt, A. (2024). Gender inclusive planning for disasters: Strategic planning to build adaptive capacity and resilience. Journal of emergency management, 23 2, 201-210. [CrossRef]

- Chineka, J., Musyoki, A., Kori, E., and Chikoore, H. (2019). Gender mainstreaming: A lasting solution to disaster risk reduction. Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 11. [CrossRef]

- Chisty, M., Rahman, M., Khan, N., and Dola, S. (2021). Assessing Community Disaster Resilience in Flood-Prone Areas of Bangladesh: From a Gender Lens. Water. [CrossRef]

- Demiroz, F., and Haase, T. (2019). The concept of resilience: a bibliometric analysis of the emergency and disaster management literature. Local Government Studies, 45, 308 - 327. [CrossRef]

- Diab, J. (2024). A Beirut blast: how inclusive disaster management for refugees and hosts reassembled a community in a disintegrated city. Gender and Development, 32, 799 - 820. [CrossRef]

- Ejem, A. A. and Ben-Enukora, C. A. (2025). Gendered impacts of 2022 floods on livelihoods and health vulnerability of rural communities in select Southern states in Nigeria. Discover Social Science and Health. 5, 67. [CrossRef]

- Elwood, A. (2009). Using the disaster crunch/release model in building organisational resilience. Journal of Business Continuity and Emergency Planning. [CrossRef]

- Enarson, E., Fothergill, A., & Peek, L. (2017). Gender and disaster: Foundations and new directions for research and practice. Handbook of disaster research, 205-223. [CrossRef]

- Erman, A., De Vries Robbe, S., Thies, S., Kabir, K., and Maruo, M. (2021). Gender Dimensions of Disaster Risk and Resilience. World Bank Other Operational Studies, The World Bank. [CrossRef]

- Forbes-Biggs, K. (2020). Applying a Gender Lens to Reduce Disaster Risk in Southern Africa: The Role of Men’s Organisations. In How Gender Can Transform the Social Sciences: Innovation and Impact. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 169-176. [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, J., Sanz, K., Balgos, B., Dalisay, S., Gorman-Murray, A., Smith, F., and Toelupe, V. (2017). Beyond men and women: a critical perspective on gender and disaster. Disasters, 41 3, 429-447. [CrossRef]

- Gaisie, E., Adu-Gyamfi, A., and Owusu-Ansah, J. (2021). Gender and household resilience to flooding in informal settlements in Accra, Ghana. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 65, 1390 - 1413. [CrossRef]

- Ginige, K., Amaratunga, D., and Haigh, R. (2009). Mainstreaming gender in disaster reduction: why and how?. Disaster Prevention and Management, 18, 23-34. [CrossRef]

- Graveline, M., and Germain, D. (2022). Disaster Risk Resilience: Conceptual Evolution, Key Issues, and Opportunities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 13, 330 - 341. [CrossRef]

- Gul, S., Khan, N., Nisar, S., Ali, Z., and Ullah, U. (2024). Impact of Climate Change-Induced Flood on Women’s Life: A Case Study of 2022 Flood in District Nowshera, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Journal of Asian Development Studies. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M., Nasreen, M., and Chowdhury, M. (2019). Gender-inclusive disaster management policy in Bangladesh: A content analysis of national and international regulatory frameworks. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 41, 101324. [CrossRef]

- Kadir, S. (2021). Viewing disaster resilience through gender sensitive lens: A composite indicator-based assessment. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. [CrossRef]

- Keating, A., and Hanger-Kopp, S. (2020). Practitioner perspectives of disaster resilience in international development. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, Z., Meng, X., and Khalid, A. (2021). A Qualitative Insight into Gendered Vulnerabilities: A Case Study of the Shishper GLOF in Hunza Valley, Pakistan. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M., Anwar, S., Sarkodie, S., Yaseen, M., Nadeem, A., and Ali, Q. (2022). Comprehensive disaster resilience index: Pathway towards risk-informed sustainable development. Journal of Cleaner Production. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C., Huang, K., Kuo, S., Lin, Y., Ke, K., Pan, T., Tai, L., Cheng, C., Shih, Y., Lai, H., and Ke, B. (2022). Gender matters: The role of women in community-based disaster risk management in Taiwan. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. [CrossRef]

- Maobe, A. and Atela, J. (2021). Gender Intersectionality and Disaster Risk Reduction - Context Analysis. Tomorrow’s Cities Working Paper 006. [CrossRef]

- Mardialina, M., Anam, S., Karjaya, L., Hidayat, A., and Lestari, B. (2024). The ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance on Disaster Management (AHA Centre): Examining Gender-Based Approach in the 2018 Lombok Earthquake. JAS (Journal of ASEAN Studies). [CrossRef]

- Mayer, B. (2019). A Review of the Literature on Community Resilience and Disaster Recovery. Current Environmental Health Reports, 6, 167 - 173. [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, S. (2011). Women, gender, and disaster: global issues and initiatives. Journal of Resources, Energy and Development, 8, 59 - 60. [CrossRef]

- Neelima, S., and Thomas, S. (2022). Improvised Gender Sensitive Disaster Impact Factor for Reinforcing Disaster Resilience Network. SSRN Electronic Journal. [CrossRef]

- Nongmaithem, J. (2024). Gendered Vulnerabilities in Disaster Responses: A Case Study of Majuli Island, Assam. Indian Journal of Social Science and Literature. [CrossRef]

- Oktari, R., Kamaruzzaman, S., Syam, F., Sofia, S., and Sari, D. (2021). Gender mainstreaming in a Disaster-Resilient Village Programme in Aceh Province, Indonesia: Towards disaster preparedness enhancement via an equal opportunity policy. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 52, 101974. [CrossRef]

- Olonade, O. Y., Oyibode, B. O., Idowu, B. O., George, T. O., Iwelumor, O. S., Ozoya, M. I., ... & Adetunde, C. O. (2021). Understanding gender issues in Nigeria: the imperative for sustainable development. Heliyon, 7(7).

- Owoeye, G. (2021). Women’s engagement in participatory politics of Kogi State, Nigeria. African Identities, 21(3), 590–602. [CrossRef]

- Parker, D. (2020). Disaster resilience – a challenged science. Environmental Hazards, 19, 1 - 9. [CrossRef]

- Ramailis, N., and Sakir, S. (2024). Increasing Women’s Resilience to Disasters: An Analysis of Gender Mainstreaming in Natural Disaster Management in Bantul, Indonesia. JISPO Jurnal Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik. [CrossRef]

- Rimbawan, I., and Nurhaeni, A. (2024). Gender Equality, Disability and Social Inclusion Approach to Disaster Management Policy: The Case of the Bali Disaster Response Authority. JISPO Jurnal Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik. [CrossRef]

- Roy, D., and Mukherjee, M. (2024). Challenges and Opportunities for Women in Disaster Risk Management. IDRiM Journal. [CrossRef]

- Saha, C. (2014). Dynamics of disaster-induced risk in southwestern coastal Bangladesh: an analysis on tropical Cyclone Aila 2009. Natural Hazards, 75, 727-754. [CrossRef]

- Sartorio, J., and Davalos, G. (2025). Gendered Participation in Resilience Building: Situating the Role of Women Leaders in Disaster-prone Communities. Journal of Health Research and Society. [CrossRef]

- El Seira, R. M., & Kurniati, E. (2020, August). Gender in Disaster Mitigation. In International Conference on Early Childhood Education and Parenting 2019 (ECEP 2019) (pp. 209-214). Atlantis Press. [CrossRef]

- Septanaya, I., and Fortuna, S. (2023). Gender mainstreaming efforts in disaster management plans: Case study West Nusa Tenggara province, Indonesia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. [CrossRef]

- Smyth, I., and Hai, V. (2012). The Disaster Crunch Model: Guidelines for a Gendered Approach.

- Tickamyer, A., and Kusujiarti, S. (2020). Riskscapes of gender, disaster and climate change in Indonesia. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 13, 233-251. [CrossRef]

- Tobi, S., Razak, K., Siow, Y., Ramlee, L., and Aris, N. (2023). Empowering women for disaster risk reduction: a case study of geologically based disaster at Yan, Kedah, Malaysia. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1144. [CrossRef]

- Yarramsetty, R., and Prasanna, B. (2024). Beyond Shelters: A Gendered Approach to Disaster Preparedness and Resilience in Urban Centers. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology (IJISRT). [CrossRef]

- Yumarni, T., Sulistiani, L., Idanati, R., and Gunarto, G. (2021). Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI) for Strengthening Disaster Resilient Village. Journal of Public Administration Studies. [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, R., and Fordham, M. (2021). The missing half of the Sendai framework: Gender and women in the implementation of global disaster risk reduction policy. Progress in Disaster Science. [CrossRef]

- Zobel, C. (2011). Representing perceived tradeoffs in defining disaster resilience. Decis. Support Syst., 50, 394-403. [CrossRef]

- Zobel, C., and Khansa, L. (2014). Characterizing multi-event disaster resilience. Comput. Oper. Res., 42, 83-94. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).