Submitted:

24 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Age-Related Differences in Effects of Negative Emotions on Cognition

1.2. Age-Related Differences in Effects of Emotions on Arithmetic Performance

1.3. Emotions and Arithmetic: A Strategy Perspective

1.4. Overview of the Present Study

2. Experiment 1. Age-Related Differences in Effects of Emotions on Strategy Selection

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Stimuli

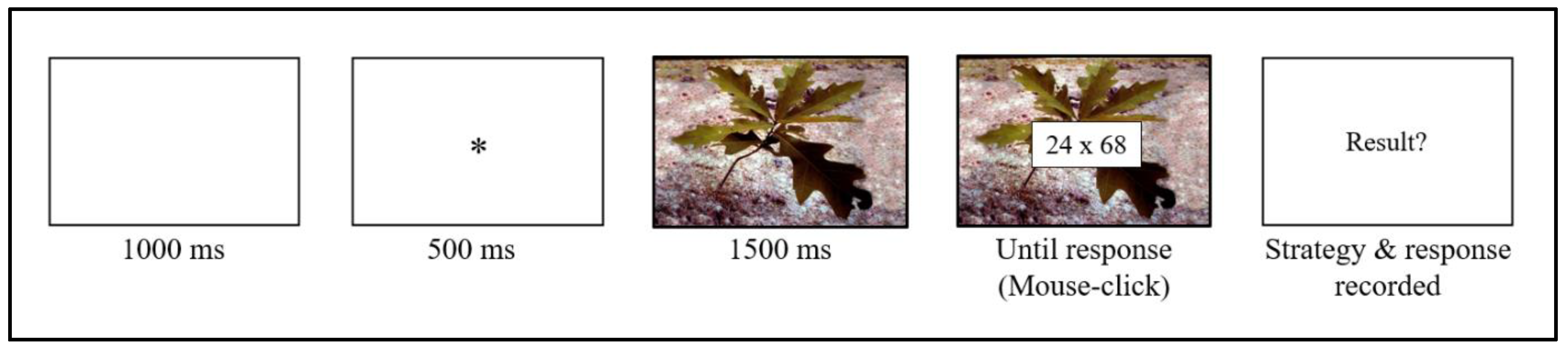

2.1.3. Procedure

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Effects of Emotions on Better Strategy Selection

2.2.2. Effects of Emotions on Performance

2.3. Summary of Findings

3. Experiment 2: Age-Related Differences in Effects of Emotions on Strategy Execution

3.1. Method

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Age-Related Differences in Effects of Emotions on Mean Estimation Times

3.2.2. Age-Related Differences in Effects of Emotions on Percentages of Correct Responses and Percentages of Deviations

3.3. Summary of Findings

4. General Discussion

4.1. How Several Types of Negative Emotions Influence Strategic Aspects of Arithmetic Performance

4.2. Age-Related Changes in Effects of Negative Emotions on Strategy Aspects of Arithmetic Performance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allard, E. S., & Isaacowitz, D. M. (2008). Are Preferences in Emotional Processing Affected by Distraction? Examining the Age-Related Positivity Effect in Visual Fixation within a Dual-Task Paradigm. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 15(6), 725–743. [CrossRef]

- Allen, V. C., & Windsor, T. D. (2019). Age differences in the use of emotion regulation strategies derived from the process model of emotion regulation: A systematic review. Aging & mental health, 23(1), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Almdahl, I. S., Martinussen, L. J., Agartz, I., Hugdahl, K., & Korsnes, M. S. (2021). Inhibition of emotions in healthy aging: age-related differences in brain network connectivity. Brain and Behavior, 11(5), e02052. [CrossRef]

- Ashley, V., & Swick, D. (2009). Consequences of emotional stimuli: Age differences on pure and mixed blocks of the emotional Stroop. Behavioral and Brain Functions, 5, Article 14. [CrossRef]

- Barber, S. J., & Kim, H. (2022). The positivity effect: A review of theories and recent findings. In G. Sedek, T. M. Hess, & D. R. Touron (Eds.), Multiple pathways of cognitive aging: Motivational and contextual influences (pp. 84–104). Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Berger, N., Richards, A., & Davelaar, E. J. (2019). Preserved proactive control in ageing: A stroop study with emotional faces vs. words. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1906. [CrossRef]

- Blanchette, I., & Campbell, M. (2012). Reasoning about highly emotional topics: Syllogistic reasoning in a group of war veterans. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 24(2), 157–164. [CrossRef]

- Blanchette, I., & Caparos, S. (2018). When emotions improve reasoning: The possible roles of relevance and utility. New Paradigm Psychology of Reasoning, 163-177.

- Blanchette, I.,&Richards, A. (2004). Reasoning about emotional and neutral materials: Is logic affected by emotion? Psychological Science, 15(11), 745–752. [CrossRef]

- Brady, B., Kneebone, I. I., Denson, N., & Bailey, P. E. (2018). Systematic review and meta-analysis of age-related differences in instructed emotion regulation success. PeerJ, 6, e6051. [CrossRef]

- Caparos, S., & Blanchette, I. (2017). Independent effects of relevance and arousal on deductive reasoning. Cognition and emotion, 31(5), 1012-1022. [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L. L., & DeLiema, M. (2018). The positivity effect: A negativity bias in youth fades with age. Current opinion in behavioral sciences, 19, 7-12. [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L. L., Pasupathi, M., Mayr, U., & Nesselroade, J. R. (2000). Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(4), 644–655. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, H. A., Johannes, K., Poppenk, J. L., Moscovitch, M., & Anderson, A. K. (2013). Evidence for the differential salience of disgust and fear in episodic memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142(4), 1100–1112. [CrossRef]

- Charles, S. T. (2010). Strength and vulnerability integration: A model of emotional well-being across adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 136(6), 1068–1091. [CrossRef]

- Chukwuorji, J. C., & Allard, E. S. (2022). The age-related positivity effect and emotion regulation: Assessing downstream affective outcomes. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 95(4), 455-469. [CrossRef]

- Cisler, J. M., Olatunji, B. O., & Lohr, J. M. (2009). Disgust, fear, and the anxiety disorders: A critical review. Clinical psychology review, 29(1), 34-46. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, P. S., McFarland, C. P., & Glisky, E. L. (2006). Effects of emotion on item and source memory in young and older adults. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 6(4), 306-322. [CrossRef]

- Davis, S. D., Peterson, D. J., Wissman, K. T., & Slater, W. A. (2019). Physiological Stress and Face Recognition : Differential Effects of Stress on Accuracy and the Confidence–Accuracy Relationship. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 8(3), 367 375. [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, J., & Hermans, D. (Eds.). (2010). Cognition and emotion: Reviews of current research and theories. Psychology Press. [CrossRef]

- Deltour, J. J. (1993). Echelle de vocabulaire de Mill Hill de J. C. Raven [Raven’s Mill–Hill Vocabulary Scale]. Adaptation française et normes européennes du Mill Hill et du Standard Progressive Matrices de Raven (PM38). Braine-le-Château, France: Editions l’Application des Techniques Modernes.

- DiGirolamo, M. A., McCall, E. C., Kibrislioglu Uysal, N., Ho, Y. W., Lind, M., & Isaacowitz, D. M. (2023). Attention to emotional stimuli across adulthood and older age: A novel application of eye-tracking within the home. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 152(5), 1439–1453. [CrossRef]

- Doerwald, F., Scheibe, S., Zacher, H., & Van Yperen, N. W. (2016). Emotional competencies across adulthood: State of knowledge and implications for the work context. Work, Aging and Retirement, 2(2), 159-216. [CrossRef]

- Duverne, S., & Lemaire, P. (2005). Aging and mental arithmetic. In J. I. D. Campbell (Ed.), Handbook of mathematical cognition (pp. 397–411). Psychology Press.

- Ebner, N. C., & Johnson, M. K. (2010). Age-group differences in interference from young and older emotional faces. Cognition and Emotion, 24(7), 1095-1116. [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P. (1992). Are there basic emotions? Psychological Review, 99(3), 550–553. [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P., Dalgleish, T., & Power, M. (1999). Basic emotions. San Francisco, USA.

- Eliades, M., Mansell, W., & Blanchette, I. (2013). The effect of emotion on statistical reasoning: Findings from a base rates task. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 25(3), 277–282. [CrossRef]

- Fabre, L., & Lemaire, P. (2019). How emotions modulate arithmetic performance: A study in arithmetic problem verification tasks. Experimental Psychology, 66(5), 368–376. [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior research methods, 39(2), 175-191. [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of psychiatric research, 12(3), 189-198. [CrossRef]

- Framorando, D., & Gendolla, G. H. (2018). The effect of negative implicit affect, prime visibility, and gender on effort-related cardiac response. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 4, 354-363. [CrossRef]

- Framorando, D., & Gendolla, G. H. (2019). Prime warning moderates implicit affect primes’ effect on effort-related cardiac response in men. Biological Psychology, 142, 62-69. [CrossRef]

- French, J. W., Ekstrom, R. B., & Price, I. A. (1963). Kit of reference tests for cognitive factors. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

- Fung, H. H., Gong, X., Ngo, N., & Isaacowitz, D. M. (2019). Cultural differences in the age-related positivity effect: Distinguishing between preference and effectiveness. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 19(8), 1414–1424. [CrossRef]

- Geurten, M., & Lemaire, P. (2022). Influence of emotional stimuli on metacognition: A study in arithmetic. Consciousness and Cognition, 106, 103430. [CrossRef]

- Geurten, M., & Lemaire, P. (2023). Domain-specific and domain-general metacognition for strategy selection in children with learning disabilities. Current Psychology, 42(17), 14297-14305. [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, C., Göbel, S. M., & Inglis, M. (2018). An introduction to mathematical cognition. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Harmon-Jones, E., Harmon-Jones, C., Amodio, D. M., & Gable, P. A. (2011). Attitudes toward emotions. Journal of personality and social psychology, 101(6), 1332. [CrossRef]

- Isaacowitz, D. M. (2012). Mood regulation in real time: Age differences in the role of looking. Current directions in psychological science, 21(4), 237-242. [CrossRef]

- Isaacowitz, D. M., & Choi, Y. (2011). The malleability of age-related positive gaze preferences: Training to change gaze and mood. Emotion, 11(1), 90–100. [CrossRef]

- Isaacowitz, D. M., Wadlinger, H. A., Goren, D., & Wilson, H. R. (2006). Is there an age-related positivity effect in visual attention? A comparison of two methodologies. Emotion, 6(3), 511–516. [CrossRef]

- Isaacowitz, D. M., Wadlinger, H. A., Goren, D., & Wilson, H. R. (2006). Selective preference in visual fixation away from negative images in old age? An eye-tracking study. Psychology and Aging, 21(1), 40–48. [CrossRef]

- Kadosh, R. C., & Dowker, A. (Eds.). (2015). The Oxford handbook of numerical cognition. Oxford Library of Psychology.

- Kensinger, E. A., & Corkin, S. (2004). Two routes to emotional memory: Distinct neural processes for valence and arousal. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(9), 3310-3315. [CrossRef]

- Kleinsorge, T. (2007). Anticipatory modulation of interference induced by unpleasant pictures. Cognition & Emotion, 21(2), 404–421. [CrossRef]

- Kleinsorge, T. (2009). Anticipation selectively enhances interference exerted by pictures of negative valence. Experimental Psychology, 56(4), 228–235. [CrossRef]

- Knight, M., Seymour, T. L., Gaunt, J. T., Baker, C., Nesmith, K., & Mather, M. (2007). Aging and goal-directed emotional attention: Distraction reverses emotional biases. Emotion, 7(4), 705–714. [CrossRef]

- Knops, A. (2019). Numerical cognition. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, S., Piel, M., & Wolf, O. T. (2005). Impaired Memory Retrieval after Psychosocial Stress in Healthy Young Men. Journal of Neuroscience, 25(11), 2977 2982. [CrossRef]

- LaMonica, H. M., Keefe, R. S., Harvey, P. D., Gold, J. M., & Goldberg, T. E. (2010). Differential effects of emotional information on interference task performance across the life span. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 2, 141. [CrossRef]

- Lallement, C., & Lemaire, P. (2021). Age-related differences in how negative emotions influence arithmetic performance. Cognition and Emotion, 35(7), 1382–1399. [CrossRef]

- Lallement, C., & Lemaire, P. (2023). Are there age-related differences in effects of positive and negative emotions in arithmetic?. Experimental Psychology, 70(5), 307. [CrossRef]

- Lallement, C., Hinault, T., Kanzari, K., & Lemaire, P. (2025). How Negative Emotions Influence Arithmetic Performance: A Magnetoencephalography Study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M., & Cuthbert, B. N. (2008). International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Affective ratings of pictures and instruction manual (Tech. Rep. A-8). Gainesville: University of Florida.

- Le Bigot, L., Knutsen, D., & Gil, S. (2018). I remember emotional content better, but I’m struggling to remember who said it!. Cognition, 180, 52-58. [CrossRef]

- Leigland, L. A., Schulz, L. E., & Janowsky, J. S. (2004). Age related changes in emotional memory. Neurobiology of aging, 25(8), 1117-1124. [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, P. (2022). Emotion and cognition: An introduction (1st ed.). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, P. (2024). Aging, emotion, and cognition: The role of strategies. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 153(2), 435. [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, P., Arnaud, L., & Lecacheur, M. (2004). Adults’ age-related differences in adaptivity of strategy choices: evidence from computational estimation. Psychology and aging, 19(3), 467. [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, P., & Reder, L. (1999). What affects strategy selection in arithmetic? The example of parity and five effects on product verification. Memory & Cognition, 27(2), 364-382. [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, P., & Siegler, R. S. (1995). Four aspects of strategic change: Contributions to children’s learning of multiplication. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 124(1), 83–97. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D., Wang, Y., Lu, F., Shu, D., Zhang, J., Zhu, C., & Luo, W. (2021). Emotional valence modulates arithmetic strategy execution in priming paradigm: an event-related potential study. Experimental Brain Research, 239(4), 1151-1163. [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, K. M., & Isaacowitz, D. M. (2015). Situation selection and modification for emotion regulation in younger and older adults. Social psychological and personality science, 6(8), 904-910. [CrossRef]

- Mather, M., & Carstensen, L. L. (2003). Aging and attentional biases for emotional faces. Psychological science, 14(5), 409-415. [CrossRef]

- Mather, M., & Carstensen, L. L. (2005). Aging and motivated cognition: The positivity effect in attention and memory. Trends in cognitive sciences, 9(10), 496-502. [CrossRef]

- Melani, P., Fabre, L., & Lemaire, P. (2024). How negative emotions influence arithmetic performance: a comparison of young and older adults. Current Psychology, 43(2), 931-941. [CrossRef]

- Melani, P., Fabre, L., & Lemaire, P. (2025). How negative emotions influence arithmetic problem-solving processes: An ERP study. Neuropsychologia, 211, 109132. [CrossRef]

- Monti, J. M., Weintraub, S., & Egner, T. (2010). Differential age-related decline in conflict-driven task-set shielding from emotional versus non-emotional distracters. Neuropsychologia, 48(6), 1697-1706. [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, J., & Freund, A. M. (2011). Age and motivation predict gaze behavior for facial expressions. Psychology and Aging, 26(3), 695–700. [CrossRef]

- Okon-Singer, H., Hendler, T., Pessoa, L., & Shackman, A. J. (2015). The neurobiology of emotion–cognition interactions: Fundamental questions and strategies for future research. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, Article 58. [CrossRef]

- Payne, J., Jackson, E., Ryan, L., Hoscheidt, S., Jacobs, J., & Nadel, L. (2006). The impact of stress on neutral and emotional aspects of episodic memory. Memory, 14(1), 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 315–341. [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2019). Achievement emotions: A control-value theory perspective. In R. Patulny, A. et al.(Eds.), Emotions in late modernity (pp. 142–157). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2012). Academic emotions and student engagement. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 259–282). Springer Science + Business Media.

- Pessoa, L. (2009). How do emotion and motivation direct executive control?. Trends in cognitive sciences, 13(4), 160-166. [CrossRef]

- Raven, J. C. (1958). Guide to using the Mill Hill Vocabulary Scale with the Progressive Matrices Scales.

- Riediger, M., & Bellingtier, J. A. (2022). Emotion regulation across the lifespan. The Oxford handbook of emotional development, 92-109.

- Reed, A. E., & Carstensen, L. L. (2012). The theory behind the age-related positivity effect. Frontiers in psychology, 3, 339. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M. D., Watkins, E. R., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2013). Handbook of cognition and emotion. Guilford Press.

- Samanez-Larkin, G. R., Robertson, E. R., Mikels, J. A., Carstensen, L. L., & Gotlib, I. H. (2009). Selective attention to emotion in the aging brain. Psychology and Aging, 24(3), 519–529. [CrossRef]

- Sands, M., & Isaacowitz, D. M. (2017). Situation selection across adulthood: The role of arousal. Cognition and Emotion, 31(4), 791-798. [CrossRef]

- Sands, M., Livingstone, K. M., & Isaacowitz, D. M. (2018). Characterizing age-related positivity effects in situation selection. International journal of behavioral development, 42(4), 396-404. [CrossRef]

- Sasse, L. K., Gamer, M., Büchel, C., & Brassen, S. (2014). Selective control of attention supports the positivity effect in aging. PloS one, 9(8), e104180. [CrossRef]

- Scheibe, S., & Carstensen, L. L. (2010). Emotional aging: Recent findings and future trends. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65(2), 135-144. [CrossRef]

- Schimmack, U., & Derryberry, D. (Ed.). (2005). Attentional Interference Effects of Emotional Pictures: Threat, Negativity, or Arousal? Emotion, 5(1), 55–66. [CrossRef]

- Talamini, F., Eller, G., Vigl, J., & Zentner, M. (2022). Musical emotions affect memory for emotional pictures. Scientific reports, 12(1), 10636. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R. C., & Hasher, L. (2006). The influence of emotional valence on age differences in early processing and memory. Psychology and Aging, 21(4), 821–825. [CrossRef]

- Uittenhove, K., & Lemaire, P. (2015). The effects of aging on numerical cognition. The Oxford handbook of numerical cognition, 345-366. [CrossRef]

- Uittenhove, K., & Lemaire, P. (2018). Performance control in numerical cognition: Insights from strategic variations in arithmetic during the life span. In Heterogeneity of function in numerical cognition (pp. 127-145). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, F., & De Houwer, J. (2007). Do emotional stimuli interfere with response inhibition? Evidence from the stop signal paradigm. Cognition and Emotion, 21(2), 391–403. [CrossRef]

- Viesel-Nordmeyer, N., & Lemaire, P. How different negative emotions affect young and older adults’ arithmetic performance in addition and multiplication problems? Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, in press.

- Wager, T. D., Kang, J., Johnson, T. D., Nichols, T. E., Satpute, A. B., and Barrett, L. F. (2015). A Bayesian model of category-specific emotional brain responses. PLoS Comput. Biol. 11:e1004066. [CrossRef]

- Waring, J. D., Greif, T. R., & Lenze, E. J. (2019). Emotional response inhibition is greater in older than younger adults. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 961. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, R. C., & Fernandes, M. A. (2021). Divided attention at encoding or retrieval interferes with emotionally enhanced memory for words. Memory, 29(3), 284-297. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C., Jiang, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, D., & Luo, W. (2021). Arithmetic performance is modulated by cognitive reappraisal and expression suppression: Evidence from behavioral and ERP findings. Neuropsychologia, 162, 108060. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C., Li, P., Li, Y., Jiang, Y., Liu, D., & Luo, W. (2022). Implicit emotion regulation improves arithmetic performance: An ERP study. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 22(3), 574-585. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C., Zhang, Z., Lyu, X., Wang, Y., Liu, D., & Luo, W. (2024). Mathematical problem solving is modulated by word priming. PsyCh journal, 13(3), 465–476. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Young adults | Older adults | Fs |

| Experiment 1. Strategy selection | |||

| N (females/males) | 39 (29/10) | 27 (20/7) | - |

| Mean age in y.m. (SD) | 21.1 (3.2) | 70.3 (5.5) | - |

| Range | 18—32 | 65—89 | - |

| Mean number of years of formal education (SD) | 14.3 (0.8) | 14.0 (2.0) | .51 |

| Arithmetic fluency (SD) | 39.0 (12.1) | 57.6 (14.9) | 31.11*** |

| Vocabulary (SD) | 20.7 (3.9) | 26.3 (3.7) | 33.32*** |

| MMSE (SD) | - | 28.7 (1.0) | - |

| Experiment 2. Strategy execution | |||

| N (females/males) | 47 (29/18) | 46 (26/20) | - |

| Mean age in y.m. (SD) | 21.3 (3.0) | 71.3 (5.0) | - |

| Range | 18—31 | 65—86 | - |

| Mean number of years of formal education (SD) | 13.7 (1.3) | 14.4 (3.3) | 1.44 |

| Arithmetic fluency (SD) | 40.3 (16.2) | 59.2 (18.7) | 27.15*** |

| Vocabulary (SD) | 20.1 (4.6) | 26.0 (3.6) | 46.64*** |

| MMSE (SD) | - | 28.9 (1.0) | - |

| RD Problems | RU Problems | |||

| 43 x 79 | 71 x 57 | 34 x 49 | 68 x 73 | |

| 43 x 86 | 71 x 58 | 34 x 59 | 69 x 54 | |

| 46 x 83 | 72 x 46 | 48 x 71 | 72 x 49 | |

| 47 x 51 | 72 x 47 | 49 x 82 | 73 x 58 | |

| 51 x 87 | 76 x 51 | 53 x 79 | 74 x 89 | |

| 52 x 79 | 76 x 81 | 54 x 68 | 79 x 54 | |

| 57 x 61 | 79 x 42 | 58 x 63 | 79 x 63 | |

| 57 x 72 | 79 x 62 | 59 x 63 | 79 x 64 | |

| 61 x 76 | 81 x 46 | 59 x 74 | 83 x 59 | |

| 63 x 86 | 82 x 57 | 62 x 59 | 84 x 47 | |

| 68 x 71 | 86 x 53 | 64 x 87 | 84 x 48 | |

| 69 x 52 | 87 x 52 | 68 x 53 | 87 x 74 | |

| Neutral Pictures | Negative Pictures | ||

|

2038, 2190, 2393, 2397, 2397, 2411, 2440, 2480, 2570, 2840, 2850, 2880, 2890, 5510, 5520, 5530, 5740, 7000, 7004, 7006, 7010, 7012, 7020, 7025, 7026, 7030, 7031, 7035, 7040, 7041, 7050, 7053, 7059, 7080, 7090, 7100, 7110, 7150, 7161, 7175, 7179, 7185, 7187, 7217, 7235, 7491, 7705, 7950 |

Disgust | Fear | Sadness |

|

2730, 2981, 3019, 3103, 3140, 3250, 3550, 6415, 9042, 9300, 9302, 9321, 9373, 9400, 9405, 9500 |

1090, 1111, 1201, 1202, 1205, 1220, 3500, 3530, 6242, 6300, 6510, 6520, 6821, 6825, 6831, 6838 |

2301, 2688, 3300, 6570.1, 9002, 9050, 9184, 9250, 9900, 9902, 9903, 9904, 9905, 9910, 9911, 9920 |

|

| Young Adults (N=39) | Older Adults (N=27) | ||||||||||||||

| Neutral | Disgust | Fear | Sadness | Disgust – Neutral | Fear – Neutral | Sadness – Neutral | Neutral | Disgust | Fear | Sadness | Disgust – Neutral | Fear – Neutral | Sadness – Neutral | ||

| Better strategy selection (%) | |||||||||||||||

| Rounding - Down | 66.1 | 46.4 | 63.9 | 74.1 | -19.8*** | -2.2 | 8.0** | 59.7 | 50.2 | 56.0 | 62.1 | -9.4** | -3.7 | 2.4 | |

| Rounding - Up | 65.9 | 62.7 | 66.0 | 65.5 | -3.1 | 0.1 | -0.4 | 66.1 | 67.2 | 72.5 | 60.3 | 1.1 | 6.4* | -5.7* | |

| Means | 66.0 | 54.5 | 64.9 | 69.8 | -11.4*** | -1.0 | 3.8* | 62.9 | 58.7 | 64.2 | 61.2 | -4.2 | 1.3 | -1.6 | |

| Estimation latencies (ms) | |||||||||||||||

| Rounding - Down | 6,267 | 6,307 | 6,902 | 6,233 | 40 | 636* | -34 | 5,435 | 5,331 | 5,041 | 5,351 | -104 | -394 | -84 | |

| Rounding - Up | 7,423 | 7,091 | 8,307 | 7,459 | -332 | 884*** | 36 | 5,681 | 5,545 | 5,820 | 5,339 | -136 | 139 | -342 | |

| Means | 6,845 | 6,699 | 7,605 | 6,846 | -146 | 760*** | 1 | 5,558 | 5,438 | 5,430 | 5,345 | -120 | -128 | -213 | |

| Percentages of deviations | |||||||||||||||

| Rounding - Down | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.8 | 6.7 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 2.2** | 5.1 | 5.6 | 5.2 | 6.9 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.8 | |

| Rounding - Up | 6.7 | 6.7 | 8.7 | 6.1 | -0.1 | 2.0* | -0.7 | 4.7 | 7.2 | 6.0 | 5.7 | 2.5* | 1.4 | 1.1 | |

| Means | 5.6 | 5.6 | 6.8 | 6.4 | -0.1 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 4.9 | 6.4 | 5.6 | 6.3 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 1.4* | |

| Effects | MSe | Fs | p | η²p |

| Better strategy selection (%) | ||||

| Age | 1,103.403 | 0.492 | .485 | .008 |

| Strategy | 1,115.703 | 3.936 | .052 | .058 |

| Emotion | 189.137 | 12.808 | < .001 | .167 |

| Age x Strategy | 1,115.703 | 1.393 | .242 | .021 |

| Age x Emotion | 189.137 | 5.253 | .002 | .076 |

| Strategy x Emotion | 156.848 | 17.502 | < .001 | .215 |

| Age x Strategy x Emotion | 156.848 | 1.630 | .184 | .025 |

| Estimation latencies | ||||

| Age | 35,002,964.210 | 8.826 | .004 | .121 |

| Strategy | 2,998,814.940 | 22.365 | < .001 | .259 |

| Emotion | 2,507,559.331 | 2.979 | .050 | .044 |

| Age x Strategy | 2,998,814.940 | 7.440 | .008 | .104 |

| Age x Emotion | 2,507,559.331 | 3.185 | .040 | .047 |

| Strategy x Emotion | 1,943,481.481 | 1.248 | .294 | .019 |

| Age x Strategy x Emotion | 1,943,481.481 | 0.440 | .700 | .007 |

| Percentages of deviations | ||||

| Age | 26.431 | 0.428 | .515 | .007 |

| Strategy | 27.744 | 5.214 | .026 | .075 |

| Emotion | 18.851 | 1.705 | .172 | .026 |

| Age x Strategy | 27.744 | 3.494 | .066 | .052 |

| Age x Emotion | 18.851 | 1.358 | .259 | .021 |

| Strategy x Emotion | 12.116 | 5.954 | .001 | .085 |

| Age x Strategy x Emotion | 11.618 | 1.267 | .287 | .019 |

| Young Adults (N=47) | Older Adults (N=46) | |||||||||||||

| Neutral | Disgust | Fear | Sadness | Disgust– Neutral | Fear – Neutral | Sadness – Neutral | Neutral | Disgust | Fear | Sadness | Disgust – Neutral | Fear – Neutral | Sadness – Neutral | |

| Estimation latencies (ms) | ||||||||||||||

| Rounding - Down | 4,197 | 4,696 | 4,613 | 4,205 | 499*** | 416*** | 8 | 3,450 | 3,520 | 3,650 | 3,365 | 71 | 201 | -85 |

| Rounding - Up | 5,447 | 5,520 | 6,554 | 5,824 | 74 | 1107*** | 377* | 4,605 | 4,532 | 4,829 | 4,568 | -73 | 224 | -37 |

| Means | 4,822 | 5,108 | 5,583 | 5,014 | 286** | 761*** | 193 | 4,027 | 4,026 | 4,239 | 3,967 | -1 | 212 | -61 |

| Percentages of correct estimations | ||||||||||||||

| Rounding - Down | 91.3 | 90.4 | 88.7 | 92.3 | -0.9 | -2.6 | 1.0 | 96.0 | 95.7 | 95.2 | 93.9 | -0.3 | -0.8 | -2.1 |

| Rounding - Up | 86.4 | 90.0 | 81.4 | 87.5 | 3.6* | -5.0* | 1.1 | 89.0 | 91.6 | 86.4 | 90.8 | 2.6 | -2.6 | 1.8 |

| Means | 88.9 | 90.2 | 85.1 | 89.9 | 1.3 | -3.8** | 1.1 | 92.5 | 93.6 | 90.8 | 92.4 | 1.2 | -1.7 | -0.1 |

| Percentages of deviations | ||||||||||||||

| Rounding - Down | 15.7 | 16.7 | 15.5 | 15.5 | 1.0* | -0.2 | -0.2 | 15.9 | 16.3 | 14.6 | 15.6 | 0.4 | -1.3*** | -0.3 |

| Rounding - Up | 16.3 | 17.9 | 15.2 | 15.8 | 1.6** | -1.1* | -0.5 | 15.9 | 16.8 | 15.0 | 16.3 | 0.9 | -0.9 | 0.4 |

| Means | 16.0 | 17.3 | 15.3 | 15.7 | 1.3** | -0.7* | -0.3 | 15.9 | 16.6 | 14.8 | 16.0 | 0.7 | -1.1*** | 0.1 |

| Effects | MSe | Fs | p | η²p |

| Estimation latencies | ||||

| Age | 19,868,106.74 | 10.657 | .002 | .105 |

| Strategy | 2,689,218.149 | 112.065 | < .001 | .552 |

| Emotion | 2,406,205.535 | 10.877 | < .001 | .107 |

| Age x Strategy | 2,689,218.149 | 1.271 | .263 | .014 |

| Age x Emotion | 2,406,205.535 | 2.928 | .043 | .031 |

| Strategy x Emotion | 847,725.522 | 5.400 | .003 | .056 |

| Age x Strategy x Emotion | 847,725.522 | 2.931 | .047 | .031 |

| Percentages of correct responses | ||||

| Age | 557.271 | 4.863 | .030 | .051 |

| Strategy | 229.846 | 20.428 | < .001 | .183 |

| Emotion | 107.263 | 5.653 | < .001 | .058 |

| Age x Strategy | 229.846 | 0.379 | .540 | .004 |

| Age x Emotion | 107.263 | 0.905 | .432 | .010 |

| Strategy x Emotion | 95.989 | 3.567 | .020 | .038 |

| Age x Strategy x Emotion | 95.989 | 0.683 | .542 | .007 |

| Percentages of deviations | ||||

| Age | 9.780 | 1.255 | .265 | .014 |

| Strategy | 9.372 | 3.447 | .067 | .036 |

| Emotion | 7.610 | 17.112 | <.001 | .158 |

| Age x Strategy | 9.372 | 0.024 | .878 | .000 |

| Age x Emotion | 7.610 | 1.667 | .183 | .018 |

| Strategy x Emotion | 6.674 | 0.784 | .481 | .009 |

| Age x Strategy x Emotion | 6.674 | 0.888 | .431 | .010 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).