Submitted:

24 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dietary Supplement

2.2. In Vitro Evaluation of Oat Beta-Glucans on Cell Viability and Cytotoxicity

2.3. Study Design, Subjects, Clinical Symptoms and Main Complaint

2.4. Colonoscopy and Histopathological Examination

2.5. Peripheral Blood Haematology and Biochemical Assays

2.6. Calprotectin and Occult Blood Stool Assays

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

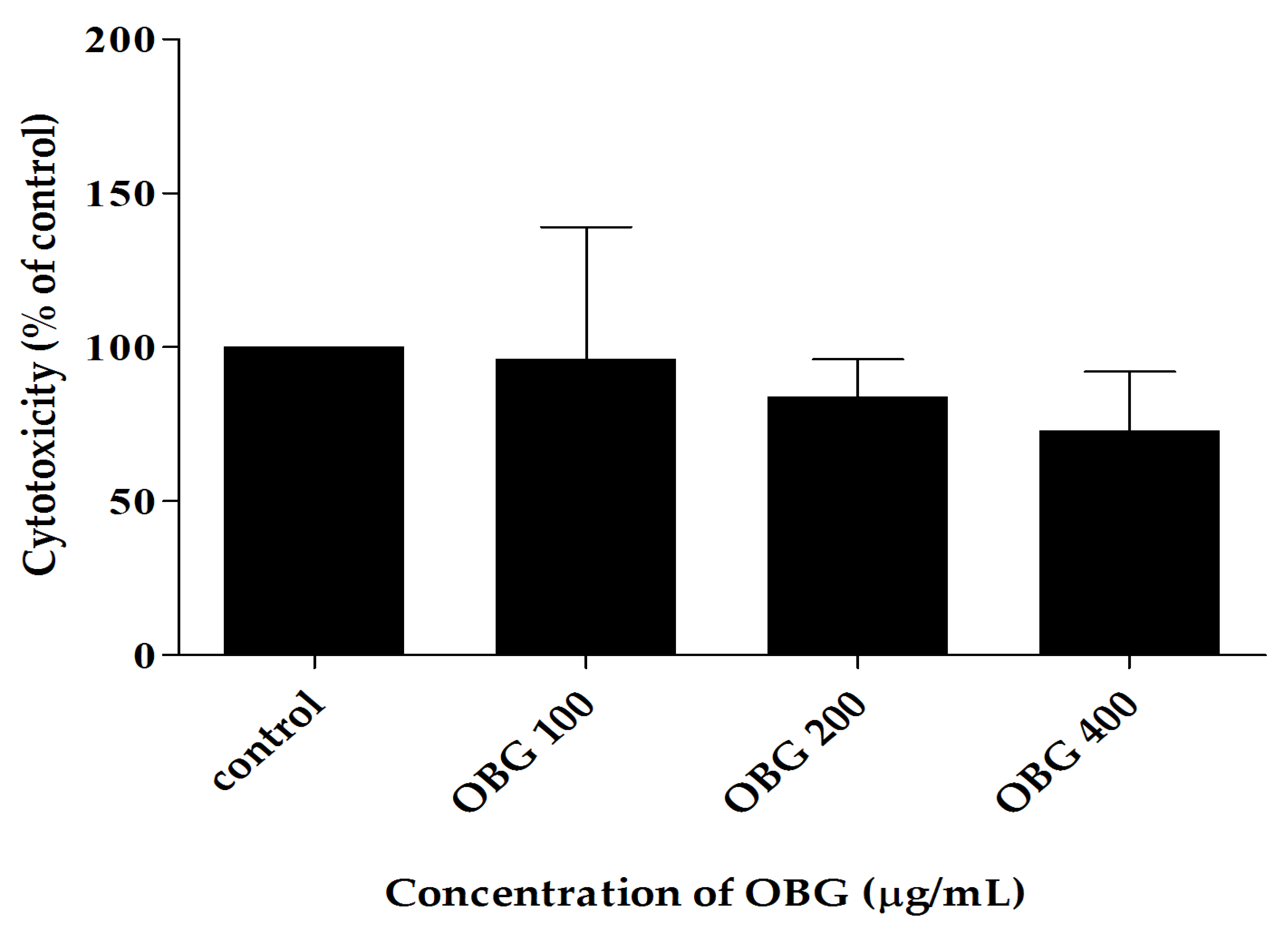

3.1. The In-Vitro Toxicity of Beta-Glucan

3.2. The Clinical Characterisation, Symptoms and Disease Activity Index (DAI)

Case 1: A Women

Case 2: A Man

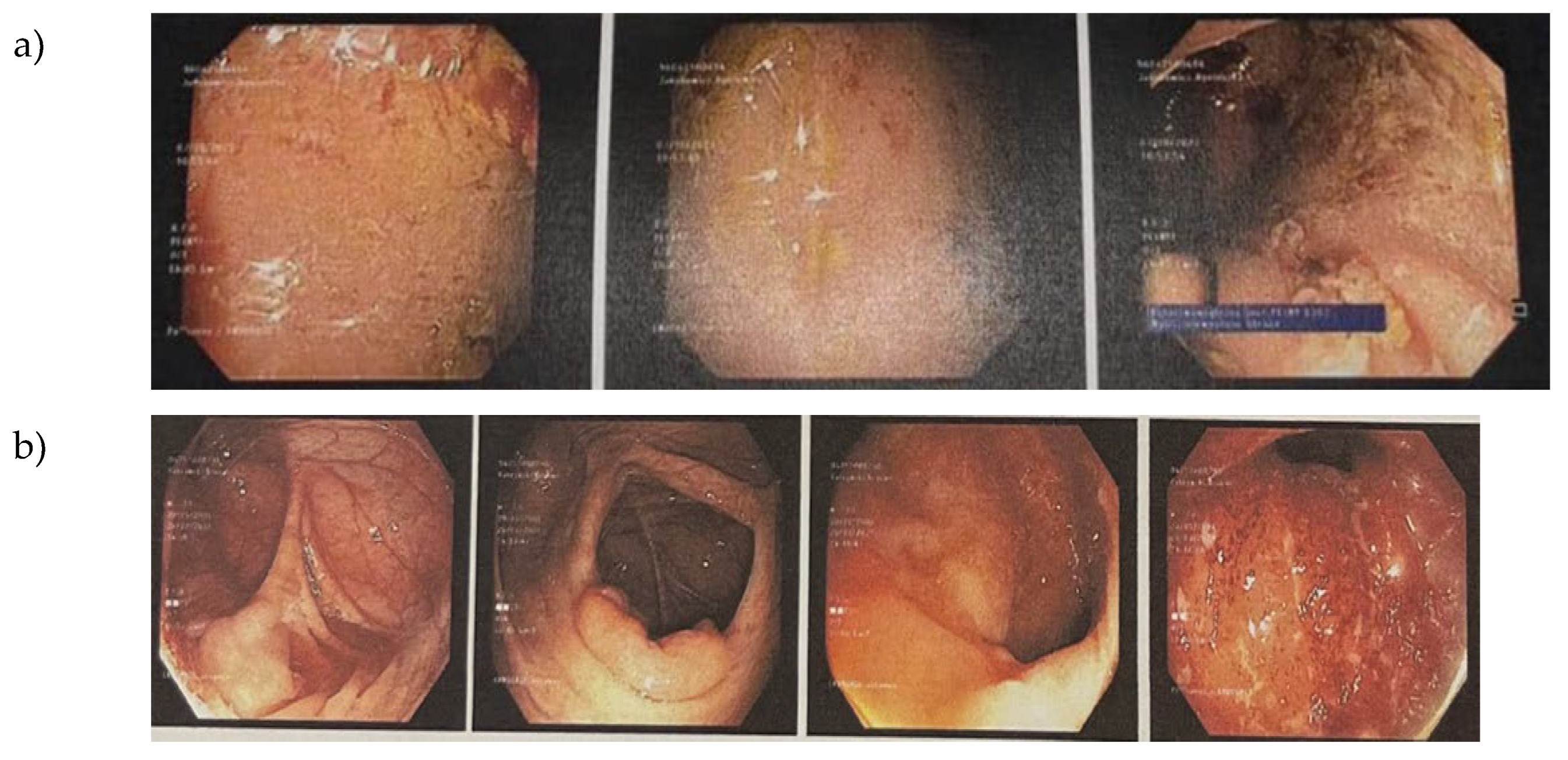

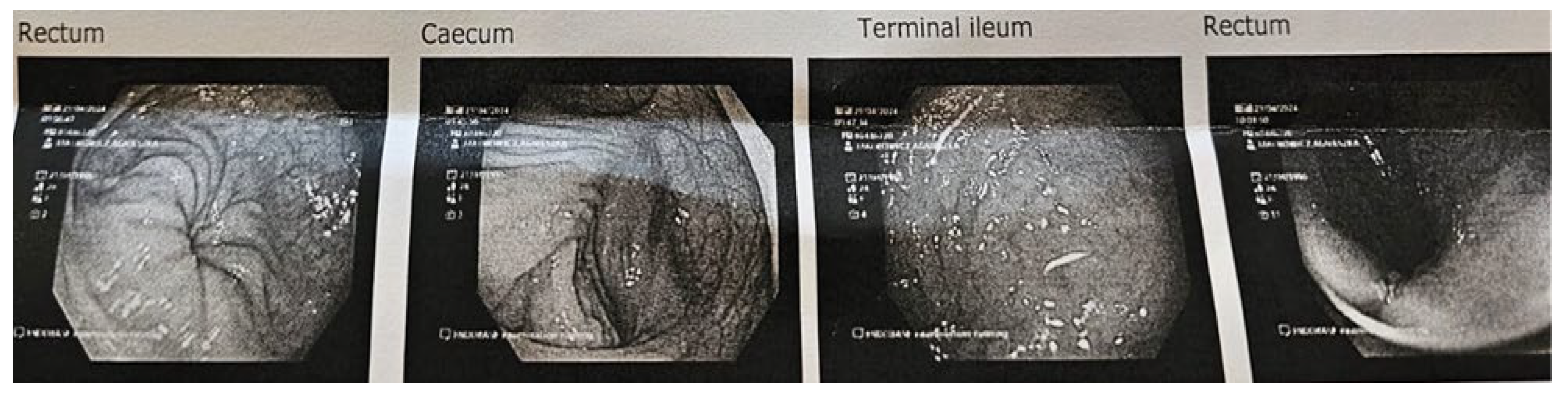

3.3. Endoscopy and Histological Examination of Biopsy Specimens

3.4. Peripheral Blood Haematology

3.5. Blood Serum Biochemical and Immunological Parameters Before and After OBG Dietary Intervention

3.6. The Fecal Calprotectin Level and Presence of Occult Blood

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IBD | inflammatory bowel disease |

| CD | Crohn disease |

| UC | ulcerative colitis |

| DAI | Disease Activity Index |

| LCAI | Lichtinger Colitis Activity Index |

| MES | Endoscopic Mayo score |

| BSFS | Bristol Stool Form Scale |

| OBG | low-molar-mass oat beta-glucan |

| FC | fecal calprotectin |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| ALT | alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | aspartate aminotransferase |

| WBC | white blood cells |

| RBC | red blood cells |

| NLR | neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| 5-ASA | 5-aminosalicylic acid |

| PAMP | pathogen-associated molecular pattern |

| BRM | biological response modifier |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| TNF-alpha | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| IL-1beta | interleukin-1 beta |

| Il-6 | interleukin-6 |

| Il-8 | interleukin-8 |

| Il-10 | interleukin-10 |

| Il-12 | interleukin-12 |

| CR3 | complement receptor 3 |

| NK | natural killer cells |

| NF-kB | nuclear factor kappa-B |

| THP-1 | Tohoku Hospital Pediatrics-1 cells line |

| HT29-MTX | human colon cancer cell line Methotrexate resistant |

| HeLa | immortal cell lines originating from Henrietta Lacks’ cervical cancer |

References

- Roda, G.; Marocchi, M.; Sartini, A.; Roda, E. Cytokine Networks in Ulcerative Colitis. Ulcers 2011, 2011, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Wangchuk, P.; Yeshi, K.; Loukas, A. Ulcerative Colitis: Clinical Biomarkers, Therapeutic Targets, and Emerging Treatments. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2024, 45, 892–903. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhou, G.; Lin, J.; Li, L.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, M.; Zhang, S. Serum Biomarkers for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020, 7, 10.3389/fmed.2020.00123.

- Zagórowicz, E.; Walkiewicz, D.; Kucha, P.; Perwieniec, J.; Maluchnik, M.; Wieszczy, P.; Reguła, J. Nationwide Data on Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Poland between 2009 and 2020. Pol Arch Intern Med 2022, 132. [CrossRef]

- Lönnfors, S.; Vermeire, S.; Greco, M.; Hommes, D.; Bell, C.; Avedano, L. IBD and Health-Related Quality of Life - Discovering the True Impact. J Crohns Colitis 2014, 8, 1281–1286. [CrossRef]

- Gionchetti, P. M.D.; Rizzello, F. M.D.; Venturi, A. M.D.; Ferretti, M. M.D.; Brignola, C. M.D.; Miglioli, M. M.D.; Campieri, M. M.D. Comparison of oral with rectal mesalazine in the treatment of ulcerative proctitis. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum 41(1):p 93-97, January 1998. |. [CrossRef]

- Meier, J.; Sturm, A. Current Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2011, 17, 3204–3212.

- Valvano, M.; Faenza, S.; Cortellini, F.; Vinci, A.; Ingravalle, F.; Calabrò, M.; Scurti, L.; Di Nezza, M.; Valerio, S.; Viscido, A.; et al. The Relationship Between Nutritional Status, Micronutrient Deficiency, and Disease Activity in IBD Patients: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2690. [CrossRef]

- Langholz E. Review: Current trends in inflammatory bowel disease: the natural history. Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology. 2010;3(2):77-86. [CrossRef]

- Ungaro, R. C., Mehandru, S., Allen, P. B., Peyrin-Biroulet, L., & Colombel, J. (2017). Ulcerative colitis. The Lancet, 389(10080), 1756-1770. [CrossRef]

- Pituch-Zdanowska, A.; Banaszkiewicz, A.; Albrecht, P. The Role of Dietary Fibre in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Prz Gastroenterol 2015, 10, 135–141. [CrossRef]

- Sushytskyi, L.; Synytsya, A.; Janačopíková, J.J.; Lukáč, P.; Rajsiglová, L.; Tenti, P.; Vannucci, L.E. Perspectives in the Application of High, Medium, and Low Molecular Weight Oat β-D-Glucans in Dietary Nutrition and Food Technology-A Short Overview. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kopiasz, Ł.; Dziendzikowska, K.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J. Colon Expression of Chemokines and Their Receptors Depending on the Stage of Colitis and Oat Beta-Glucan Dietary Intervention-Crohn’s Disease Model Study. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kopiasz, Ł.; Dziendzikowska, K.; Gajewska, M.; Wilczak, J.; Harasym, J.; Żyła, E.; Kamola, D.; Oczkowski, M.; Królikowski, T.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J. Time-Dependent Indirect Antioxidative Effects of Oat Beta-Glucans on Peripheral Blood Parameters in the Animal Model of Colon Inflammation. Antioxidants 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Harasym, J.; Dziendzikowska, K.; Kopiasz, Ł.; Wilczak, J.; Sapierzyński, R.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J. Consumption of Feed Supplemented with Oat Beta-Glucan as a Chemopreventive Agent against Colon Cancerogenesis in Rats. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Harasym, J.; Suchecka, D.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J. Effect of Size Reduction by Freeze-Milling on Processing Properties of Beta-Glucan Oat Bran. J Cereal Sci 2015, 61, 119–125. [CrossRef]

- Harasym, J.; Zyła, E.˙; Dziendzikowska, K.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J.; Barba, F.J. Molecules Proteinaceous Residue Removal from Oat β-Glucan Extracts Obtained by Alkaline Water Extraction. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.R.; Martin, F.; Greer, S.; Robinson, M.; Greenberger, N.; Saibil, F.; Martin, T.; Sparr, J.; Prokipchuk, E.; Borgen, L. 5-Aminosalicylic Acid Enema in the Treatment of Distal Ulcerative Colitis, Proctosigmoiditis, and Proctitis. Gastroenterology 1987, 92, 1894–1898. [CrossRef]

- Schoepfer, A.M.; Beglinger, C.; Straumann, A.; Safroneeva, E.; Romero, Y.; Armstrong, D.; Schmidt, C.; Trummler, M.; Pittet, V.; Vavricka, S.R. Fecal Calprotectin More Accurately Reflects Endoscopic Activity of Ulcerative Colitis than the Lichtiger Index, C-Reactive Protein, Platelets, Hemoglobin, and Blood Leukocytes. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013, 19, 332–341. [CrossRef]

- Suraiya, S.; Jang, W.J.; Haq, M.; Kong, I.-S. Isolation and Characterization of β-Glucan Containing Polysaccharides from Monascus Spp. Using Saccharina Japonica as Submerged Fermented Substrate. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Choromanska, A.; Kulbacka, J.; Harasym, J.; Oledzki, R.; Szewczyk, A.; Saczko, J. High- and Low-Molecular Weight Oat Beta-Glucan Reveals Antitumor Activity in Human Epithelial Lung Cancer.. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, K.; Bashir, I.; Choi, J.-S. Molecular Sciences Clinical and Physiological Perspectives of β-Glucans: The Past, Present, and Future.. [CrossRef]

- Kumar Upadhyay, T.; Trivedi, R.; Khan, F.; Ahmed Al-Keridis, L.; Pandey, P.; Baran Sharangi, A.; Alshammari, N.; Abdullah, N.M.; Kumar Yadav, D.; Saeed, M.; et al. In Vitro Elucidation of Antioxidant, Antiproliferative, and Apoptotic Potential of Yeast-Derived b-1,3-Glucan Particles against Cervical Cancer Cells OPEN ACCESS EDITED BY. Frontiers in Oncology frontiersin.org Front. Oncol 2022, 12, 942075. [CrossRef]

- Al-Khuzaay, H.M.; Al-Juraisy, Y.H.; Alwan, A.H.; Tousson, E. Evaluation of Effect of β-Glucan on Cancer Cell Lines In Vitro. Al-Mustansiriyah Journal of Science 2024, 35, 17–20. [CrossRef]

- Boulifa, A.; Raftery, M.J.; Franzén, A.S.; Radecke, C.; Stintzing, S.; Blohmer, J.U.; Pecher, G. Role of Beta-(1→3)(1→6)-D-Glucan Derived from Yeast on Natural Killer (NK) Cells and Breast Cancer Cell Lines in 2D and 3D Cultures. BMC Cancer 2024, 24. [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Baruah, K.; Cox, E.; Vanrompay, D.; Bossier, P. Structure-Functional Activity Relationship of β-Glucans From the Perspective of Immunomodulation: A Mini-Review. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 521871.

- Zhong, X.; Wang, G.; Li, F.; Fang, S.; Zhou, S.; Ishiwata, A.; Tonevitsky, A.G.; Shkurnikov, M.; Cai, H.; Ding, F. Immunomodulatory Effect and Biological Significance of β-Glucans. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1615. [CrossRef]

- Kankkunen, P.; Teirilä, L.; Rintahaka, J.; Alenius, H.; Wolff, H.; Matikainen, S. (1,3)-Beta-Glucans Activate Both Dectin-1 and NLRP3 Inflammasome in Human Macrophages. J Immunol 2010, 184, 6335–6342. [CrossRef]

- Lamoth, F.; Akan, H.; Andes, D.; Cruciani, M.; Marchetti, O.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Racil, Z.; Clancy, C.J. Assessment of the Role of 1,3-β-d-Glucan Testing for the Diagnosis of Invasive Fungal Infections in Adults. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2021, 72, S102–S108. [CrossRef]

- Novak, M. and Větvička, V. (2009). Glucans as biological response modifiers. Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders - Drug Targets, 9(1), 67-75. [CrossRef]

- Ramendra, R.; Mancini, M.; Ayala, J.M.; Tung, L.T.; Isnard, S.; Lin, J.; Routy, J.P.; Nijnik, A.; Langlais, D. Glutathione Metabolism Is a Regulator of the Acute Inflammatory Response of Monocytes to (1→3)-β-D-Glucan. Front Immunol 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Camilli, G., Tabouret, G., & Quintin, J. (2018). The complexity of fungal β-glucan in health and disease: effects on the mononuclear phagocyte system. Frontiers in Immunology, 9. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Sluis, M.; Bouma, J.; Vincent, A.; Velcich, A.; Carraway, K.L.; Büller, H.A.; Einerhand, A.W.C.; Van Goudoever, J.B.; Van Seuningen, I.; Renes, I.B. Combined Defects in Epithelial and Immunoregulatory Factors Exacerbate the Pathogenesis of Inflammation: Mucin 2-Interleukin 10-Deficient Mice. Laboratory Investigation 2008, 88, 634–642. [CrossRef]

- Krzystek-Korpacka, M.; Kempiński, R.; Bromke, M.; Neubauer, K. Biochemical Biomarkers of Mucosal Healing for Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Adults. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 367. [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, K.; Ishihara, S.; Yuki, T.; Fukuba, N.; Oshima, N.; Kazumori, H.; Sonoyama, H.; Yamashita, N.; Tada, Y.; Kusunoki, R.; et al. Fecal Calprotectin Level Correlated with Both Endoscopic Severity and Disease Extent in Ulcerative Colitis. BMC Gastroenterol 2016, 16. [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.Y.; Cheon, Chang, J. Y. and Cheon, J. H. (2018). Fecal immunochemical test and fecal calprotectin measurement are noninvasive monitoring tools for predicting endoscopic activity in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut and Liver, 12(2), 117-118. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, M.J.; Chang, K.; Song, E.M.; Hwang, S.W.; Park, S.H.; Yang, D.H.; Kim, K.J.; Byeon, J.S.; Myung, S.J.; et al. Fecal Calprotectin Predicts Complete Mucosal Healing and Better Correlates with the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity than with the Mayo Endoscopic Subscore in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. BMC Gastroenterol 2017, 17. [CrossRef]

- Steinsbø, Ø.; Aasprong, O.G.; Aabakken, L.; Karlsen, L.N.; Grimstad, T. Fecal Calprotectin Correlates with Disease Extent but Remains a Reliable Marker of Mucosal Healing in Ulcerative Colitis. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2025. [CrossRef]

- Masoodi, I., Tijjani, B. M., Wani, H., Hassan, N., Khan, A., & Hussain, S. (2011). Biomarkers in the management of ulcerative colitis: a brief review. GMS German Medical Science; 9:Doc03; ISSN 1612-3174. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, S.; Bruining, D.H.; Loftus, E. V.; Thia, K.T.; Schroeder, K.W.; Tremaine, W.J.; Faubion, W.A.; Kane, S. V.; Pardi, D.S.; de Groen, P.C.; et al. Validation of the Ulcerative Colitis Colonoscopic Index of Severity and Its Correlation With Disease Activity Measures. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2013, 11, 49-54.e1. [CrossRef]

- Zittan, E.; Kelly, O.B.; Kirsch, R.; Milgrom, R.; Burns, J.; Nguyen, G.C.; Croitoru, K.; Van Assche, G.; Silverberg, M.S.; Steinhart, A.H. Low Fecal Calprotectin Correlates with Histological Remission and Mucosal Healing in Ulcerative Colitis and Colonic Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016, 22, 623–630. [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, T.; Saruta, M. Positioning and Usefulness of Biomarkers in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Digestion 2023, 104, 30–41. [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, M.; Rosa, A. De; Serao, R.; Picone, I.; Vietri, M.T. Laboratory Markers in Ulcerative Colitis: Current Insights and Future Advances. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2015, 6, 13–22. [CrossRef]

- Sharara, A.I.; Malaeb, M.; Lenfant, M.; Ferrante, M. Assessment of Endoscopic Disease Activity in Ulcerative Colitis: Is Simplicity the Ultimate Sophistication? Key Messages • Current Endoscopic Scores for UC Have Important Limitations at Assessing Endoscopic Remission. Fur-Ther Validation and Adoption of Newer Endoscopic Scores Could Be Advantageous. Review Article Inflamm Intest Dis 2022, 7, 7–12. [CrossRef]

- Sturm, A., Maaser, C., Calabrese, E., Annese, V., Fiorino, G., Kucharzik, T., … & Stoker, J. (2018). Ecco-esgar guideline for diagnostic assessment in ibd part 2: ibd scores and general principles and technical aspects. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis, 13(3), 273-284. [CrossRef]

- Nakase, H.; Uchino, M.; Shinzaki, S.; Matsuura, M.; Matsuoka, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Saruta, M.; Hirai, F.; Hata, K.; Hiraoka, S.; et al. Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines for Inflammatory Bowel Disease 2020. J Gastroenterol 2021, 56, 489–526.

- Jaeschke, W.; Catanzaro, R.; Marotta, F.; Yazdani, A.; Sciuto, M. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Therapies and Acute Liver Injury. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D’Haens, G.; Safroneeva, E.; Thorne, H.; Laoun, R. Assessing the Clinical and Endoscopic Efficacy of Extended Treatment Duration with Different Doses of Mesalazine for Mild-to-Moderate Ulcerative Colitis beyond 8 Weeks of Induction. Inflamm Intest Dis 2023, 8, 51–59. [CrossRef]

- Id, E.M.; Mechie, N.-C.; Knoop Id, R.; Petzold, G.; Ellenrieder, V.; Kunsch, S.; Pilavakis, Y.; Amanzada Id, A. Association of Serum Interleukin-6 and Soluble Interleukin-2-Receptor Levels with Disease Activity Status in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Prospective Observational Study. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Aebisher, D.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D.; Przygórzewska, A.; Ole’s, P.O.; Wo’znicki, P.W.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A. Key Interleukins in Inflammatory Bowel Disease-A Review of Recent Studies. J. Mol. Sci 2024, 2025, 121. [CrossRef]

- Vestergaard, M.V.; Allin, K.H.; Poulsen, G.J.; Lee, J.C.; Jess, T. Characterizing the Pre-Clinical Phase of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cell Rep Med 2023, 4, 101263. [CrossRef]

- Celikbilek, M.; Dogan, S.; Ozbakir, O.; Zararsiz, G.; Kücük, H.; Gürsoy, S.; Yurci, A.; Güven, K.; Yücesoy, M. Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio as a Predictor of Disease Severity in Ulcerative Colitis. J Clin Lab Anal 2013, 27, 72–76. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Pang, X.; Ji, G.; Ma, X.; Li, J.; Chang, Y.; Ma, C.; Cheng, Y. Application of the Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio in the Diagnosis and Activity Determination of Ulcerative Colitis: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Medicine 2021, 100, E27551. [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Palau, M.; Vera-Santana, B.; Morant-Domínguez, A.; Hernández-Camba, A.; Ramos, L.; Alonso-Abreu, I.; Hernández Álvarez-Buylla, N.; Arranz, L.; Vela, M.; Hernández-Guerra, M.; et al. Clinical Medicine Hematological Composite Scores in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2023 2023, 12, 7248. [CrossRef]

| Case 1 (a woman) | Case 2 (a man) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 27 | 20 |

| Diagnosis | Ulcerative Colitis | Ulcerative Colitis |

| Mayo Endoscopic score (MES) | 2 (Moderate) | 3 (Severe) |

| Key Endoscopic Findings | Oedema, erythema, absent vascular pattern, friability/contact bleeding, erosions |

Spontaneous bleeding, ulceration |

| Stool Frequency (per day) | ~15 | Up to 20 |

| The disease activity index (DAI) | 5 (moderate active disease) |

8 (active disease course) |

| Lichtiger Colitis Activity Index (LCAI) |

16 (An active disease course and no response to treatment) |

19 (An active disease course and no response to treatment) |

| Parameter | Case 1 before/after |

Case 2 before/after |

Reference range |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBC x106/μL | 4.32/4.75 | 5.3/5.57 | 4.3-5.8 |

| Hemoglobin [g/dL] | 12.2/13.0 | 14.6/16.1 | 12.0-18.0 |

| Hematocrit [%] | 37.2/39.4 | 45.6/48.0 | 34.0-52.0 |

| WBC x103/μL | 3.33 /4.4 | 5.3/6.49 | 4.2-10.0 |

| Lymphocytes x103/μL | 1.47/1.2 | 2.23/2.25 | 1.3-4.0 |

| Neutrophils x103/μL | 1.46/2.78 | 2.43/3.54 | 1.78-6.04 |

| Platelets x103/μL | 225/196 | 296/292 | 140.0-450.0 |

| NLR | 0.9/2.3 | 1.1/1.6 | 1.91-3.10 |

| Parameter | Case 1 before/after |

Case 2 before/ after |

Reference range |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALT u/L | 18 /25 | 12.9/44 | 0.0-50 |

| AST u/L | 44.0/53.0 | 19.9/37.0 | 0.0-130 |

| CRP mg/L | 1/<1 | 9.4/0.8 | 0.0-5.0 |

| Il-1beta pg/mL | 1.8/1.8 | <6,7/< 2.0 | < 6.7 |

| Il-6 pg/mL | 2.3/2.9 | 1.4/1.8 | < 2.0 |

| Il-8 pg/mL | 3.3/2.8 | 1.5/<3.0 | < 3.0 |

| Il-10 pg/mL | 1.2/1.6 | 1.9/<2,8 | < 2.8 |

| Il-12 pg/mL | 1.5/<1.9 | 1.1/<1.9 | < 1.9 |

| TNF-alpha pg/mL | <3.7/2.4 | 4.1/<7.2 | < 7.2 |

| Parameter | Case 1 before/after |

Case 2 before/ after |

Reference range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calprotectin [μg/g] | 316/<5.0 | 2640/1.0 | < 50 |

| Occult blood | Negative/Negative | Positive/Negative |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).