Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background/Objectives: Diarrhoea in older adults can lead to dehydration and malnutrition, impair gut barrier function, and impact overall health and quality of life. This pilot study evaluated the effects of a new oral rehydration solution (ORS) with the postbiotic ABB C22® on diarrhoea and associated inflammation in an elderly population. Methods: Forty-seven participants with diarrhoea were randomized to receive treatment with either ORS enriched with ABB C22®, or standard treatment of ORS with placebo. Participants were treated for a maximum of 14 days across two hospital centres in Barcelona, Spain. The primary endpoints of the study were the reduction in faecal levels of the inflammatory biomarkers calprotectin, lactoferrin and immunoglobulin A. Secondary endpoints included changes in stool consistency and tolerability. Results: At day 14, the ORS + ABB C22® group showed greater reductions from baseline in faecal calprotectin and lactoferrin levels compared with the ORS + placebo group, with lactoferrin-positive cases being halved by day 3. Stool consistency according to the Bristol stool scale improved in both groups. No adverse events were reported in either group. Conclusions: This study highlights that inflammation associated with diarrhoea is often overlooked. While standard ORS improves stool consistency and hydration parameters, it does not address the underlying inflammation in a largely frail population. ABB C22® postbiotic-enriched ORS showed superior anti-inflammatory effects compared with ORS + placebo. These results suggest that postbiotics may offer a novel approach to treating both the symptoms and inflammation associated with diarrhoea. Further research is needed to confirm the clinical benefits of postbiotic-enriched ORS formulations in larger patient populations, and to assess their effect on other digestive diseases.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

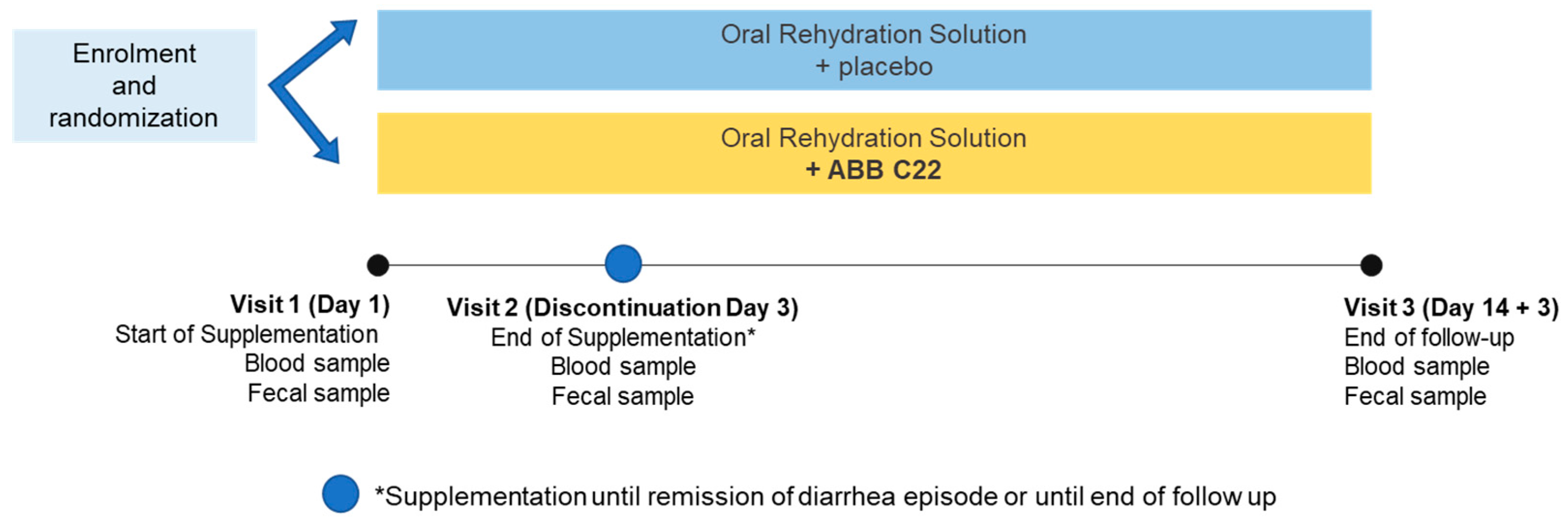

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population Selection and Randomization

2.3. Study Treatment and Intervention

2.4. Laboratory Analyses

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

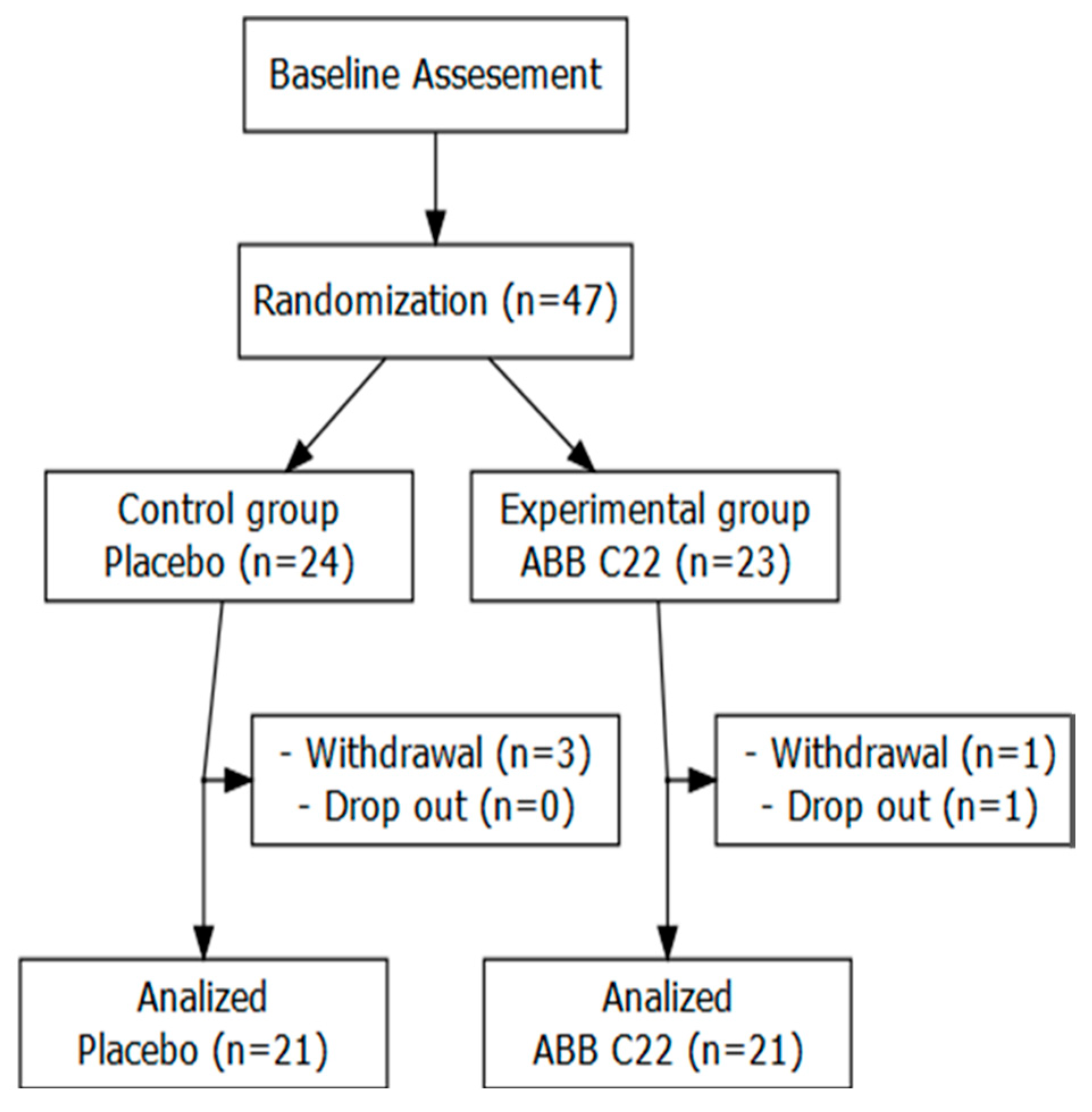

3.1. Participants

3.2. Biomarker Levels

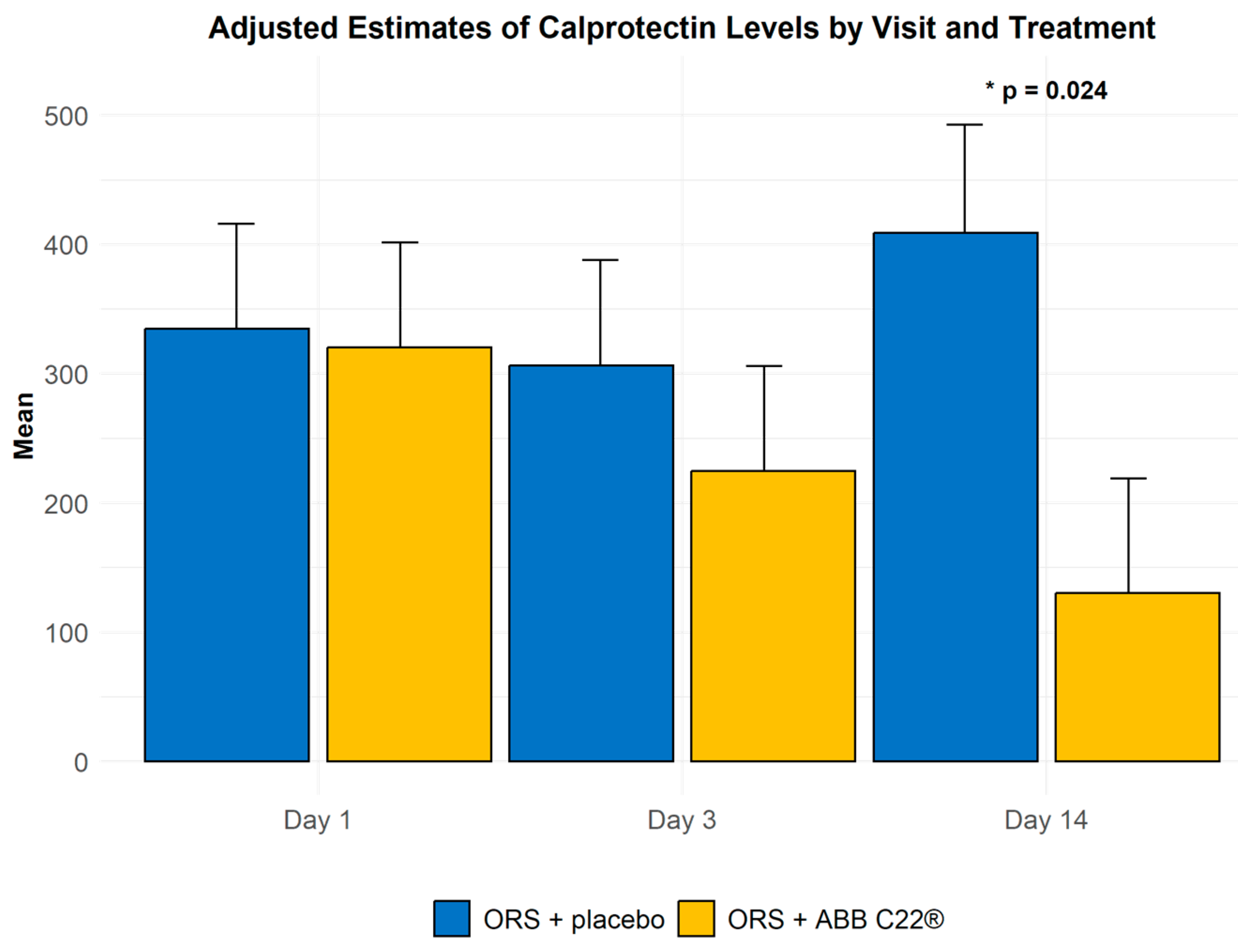

3.2.1. Inflammatory Markers

3.2.2. Faecal Consistency (Bristol stool scale)

3.3. Tolerability and Safety

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Brien, L.; Wall, C.; Wilkinson, T.J.; Gearry, R.B. Chronic Diarrhoea in Older Adults and the Role of Dietary Interventions. Nutr. Healthy Aging 2022, 7(1–2), 39–50. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Diarrhoeal Disease. World Health Organization Fact Sheets. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Slotwiner-Nie, P.K.; Brandt, L.J. Infectious Diarrhea in the Elderly. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 30(3), 625–635. [CrossRef]

- Malek, M.A.; et al. The Epidemiology of Rotavirus Diarrhea in Countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. J. Infect. Dis. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Akhondi, H.; Simonsen, K.A. Bacterial Diarrhea. In StatPearls, 2021.

- Schiller, L.R. Chronic Diarrhea Evaluation in the Elderly: IBS or Something Else? Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.; Voigt, W.; Jordan, K. Review: Chemotherapy-Induced Diarrhea: Pathophysiology, Frequency and Guideline-Based Management. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Mushtaq, M. Antibiotic Associated Diarrhea in Children. Indian Pediatr. 2009.

- Nguyen, D.L. Guidance for Supplemental Enteral Nutrition Across Patient Populations. Am. J. Manag. Care 2017, 23, S210–S219.

- McClave, S.A.; Dibaise, J.K.; Mullin, G.E.; Martindale, R.G. ACG Clinical Guideline: Nutrition Therapy in the Adult Hospitalized Patient. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2016. [CrossRef]

- McClave, S.A.; et al. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.G.; Greenough, W.B., III. Approach to Acute Diarrhea in the Elderly. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 1993, 22(3), 517–533. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, X. Hydration Status in Older Adults: Current Knowledge and Future Challenges. Nutrients 2023, 15(11), 2609. [CrossRef]

- Wittbrodt, M.T.; Millard-Stafford, M. Dehydration Impairs Cognitive Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50(11), 2360–2368. [CrossRef]

- Brandt, K.G.; Castro Antunes, M.M.; Silva, G.A. Acute Diarrhea: Evidence-Based Management. J. Pediatr. (Rio J.) 2015, 91(6 Suppl 1), S36–S43. [CrossRef]

- McFarland, L.V. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Saccharomyces boulardii in Adult Patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 2202–2222. [CrossRef]

- Guarner, F.; et al. WGO Global Guidelines: Probiotics and Prebiotics. J. of Clin. Gastroent. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000002002 .

- Czerucka, D.; Rampal, P. Diversity of Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 Mechanisms of Action Against Intestinal Infections. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Feizizadeh, S.; Salehi-Abargouei, A.; Akbari, V. Efficacy and Safety of Saccharomyces boulardii for Acute Diarrhea. Pediatrics 2014. [CrossRef]

- Szajewska, H.; Kołodziej, M. Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis: Saccharomyces boulardii in the Prevention of Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhoea. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Tung, J.M.; Dolovich, L.R.; Lee, C.H. Prevention of Clostridium difficile Infection with Saccharomyces boulardii: A Systematic Review. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, J.Z.; et al. Probiotics for the Prevention of Clostridium difficile-Associated Diarrhea in Adults and Children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.H.; et al. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Multicenter Trial of Saccharomyces boulardii in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Effect on Quality of Life. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Binder, H.J. Role of Colonic Short-Chain Fatty Acid Transport in Diarrhea. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.M.; et al. Effects of Saccharomyces boulardii on Fecal Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Microflora in Patients on Long-Term Total Enteral Nutrition. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 11, 6165–6169. [CrossRef]

- Piqué, N.; Berlanga, M.; Miñana-Galbis, D. Health Benefits of Heat-Killed (Tyndallized) Probiotics: An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Nataraj, B.H.; Ali, S.A.; Behare, P.V.; Yadav, H. Postbiotics-Parabiotics: The New Horizons in Microbial Biotherapy and Functional Foods. Microb. Cell Fact. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Carrera Marcolin, L.; Cuñé Castellana, J.; Martí Melero, L.; de Lecea, C.; Tintoré Gazulla, M. Synergistic Effect of Postbiotic Yeast ABB C22® on Gut Inflammation, Barrier Function, and Protection from Rotavirus Infection in In Vitro Models. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 4, 811–823. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO); United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). Clinical Management of Acute Diarrhoea: WHO/UNICEF Joint Statement. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/68627/WHO_FCH_CAH_04.7.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Generoso, S.V.; et al. Protection Against Increased Intestinal Permeability and Bacterial Translocation Induced by Intestinal Obstruction in Mice Treated with Viable and Heat-Killed Saccharomyces boulardii. Eur. J. Nutr. 2011, 50, 261–269. [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, J.B.; Glerup, H.; Tarp, B. Saccharomyces boulardii Fungemia Caused by Treatment with a Probioticum. BMJ Case Rep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Appel-da-Silva, M.C.; Narvaez, G.A.; Perez, L.R.R.; Drehmer, L.; Lewgoy, J. Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii Fungemia Following Probiotic Treatment. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Binder, H.J., Brown, I., Ramakrishna, B.S., Young, G.P.; Oral rehydration therapy in the second decade of the twenty-first century. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;16(3):376. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Morón JM, Argüelles-Arias F, Pallarés-Manrique H, Ramos-Lora M. Utilidad de la calprotectina fecal en la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Rev Asoc Peru Dermatol. 2017;40(2):70-78.

- Olafsdottir, E.; Aksnes, L.; Fluge, G.; Berstad, A. Faecal calprotectin levels in infants with infantile colic, healthy infants, children with inflammatory bowel disease, children with recurrent abdominal pain and healthy children. Acta Paediatr. 2002, 91, 45–50. [CrossRef]

- Langhorst, J.; Elsenbruch, S.; Koelzer, J.; Rueffer, A.; Michalsen, A.; Dobos, G.J. Noninvasive markers in the assessment of intestinal inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases: Performance of fecal lactoferrin, calprotectin, and PMN-elastase, CRP, and clinical indices. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 103, 162–169.

- Lozoya Angulo ME, de las Heras Gómez I, Martinez Villanueva M, Noguera Velasco JA, Avilés Plaza F. Faecal calprotectin, a useful marker in discriminating between inflammatory bowel disease and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40(2):70-78. [CrossRef]

- Poullis, A.; Foster, R.; Northfield, T.C.; Mendall, M.A. Review article: Faecal markers in the assessment of activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002, 16, 675–681. [CrossRef]

- Langhorst J, Elsenbruch S, Koelzer J, Rueffer A, Michalsen A, Dobos GJ. Noninvasive markers in the assessment of intestinal inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases: performance of fecal lactoferrin, calprotectin, and PMN-elastase, CRP, and clinical indices. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(1):162–9. [CrossRef]

- Kane SV, Sandborn WJ, Rufo PA, et al. Fecal lactoferrin is a sensitive and specific marker in identifying intestinal inflammation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(6):1309–14. [CrossRef]

- Rendek Z, Falk M, Grodzinsky E, Kechagias S, Hjortswang H. Oral omeprazole and diclofenac intake is associated with increased faecal calprotectin levels: a randomised open-label clinical trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17(Suppl 1):i356. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Boateng ID, Xu J. Targeting gut microbiota and metabolism as the major probiotic mechanism: An evidence-based review. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2023;135:115–30. [CrossRef]

- Brown KH. Diarrhea and malnutrition. J Nutr. 2003 Jan;133(1):328S-332S. [CrossRef]

- DuPont HL, Hornick RB. Adverse effect of lomotil therapy in shigellosis. JAMA. 1973;226(12):1525–8. [CrossRef]

- Koo HL, Koo DC, Musher DM, et al. Antimotility agents for the treatment of Clostridium difficile diarrhea and colitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(5):598–605. [CrossRef]

- Nemeth V, Pfleghaar N. Diarrhea. [Updated 2022 Nov 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448082/.

- Lazzerini M, Wanzira H. Oral zinc for treating diarrhoea in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(12):CD005436. [CrossRef]

| ORS + placebo | ORS + ABB C22® | |

|---|---|---|

| n=21 | n=21 | |

| Age, mean (SD) years | 78.4 (8.79) | 83.5 (9.46) |

| Sex, n (%): | ||

| Male | 5 (23.8%) | 5 (23.8%) |

| Female | 16 (76.2%) | 16 (76.2%) |

| Biomarker and Study Visit | ORS + placebo | ORS + ABB C22® | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n=21 | n=21 | p-Value* | |

| Faecal calprotectin: Mean (SD) µg/g | ||||

| Day 1 | 40 | 337 (496) | 310 (679) | 0.901 |

| Day 3 | 42 | 308 (284) | 208 (261) | 0.480 |

| Day 14 | 37 | 418 (592) | 135 (129) | 0.024 |

| Faecal lactoferrin: n (%) with positive result | ||||

| Day 1 | 41 | 9 (42.9%) | 5 (25.0%) | 0.614 |

| Day 3 | 42 | 9 (42.9%) | 3 (14.3%) | 0.121 |

| Day 14 | 37 | 4 (21.1%) | 2 (11.1%) | 0.692 |

| Serum IgA: Mean (SD) mg/dL | ||||

| Day 1 | 38 | 279 (150) | 247 (124) | 0.830 |

| Day 3 | 37 | 283 (142) | 237 (111) | 0.532 |

| Day 14 | 33 | 285 (131) | 271 (128) | 0.463 |

| Study Visit | ORS + placebo | ORS + ABB C22® |

|---|---|---|

| n=21 | n=21 | |

| Day 1 | 6.29 (0.72) | 6.05 (0.80) |

| Day 3 (n=41) | 5.86 (0.73) | 5.40 (0.94) |

| Day 14 (n=39) | 4.38 (1.32) | 4.22 (1.00) |

| Treatment Group | Visit Comparison | Difference | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORS + placebo | Day 1 - Day 3 | 0.429 | -0.216 - 1.07 | 0.2562 |

| ORS + placebo | Day 1 - Day 14 | 1.905 | 1.261 - 2.55 | <.0001 |

| ORS + placebo | Day 3 - Day 14 | 1.476 | 0.832 - 2.12 | <.0001 |

| ORS + ABB C22® | Day 1 - Day 3 | 0.625 | -0.027 - 1.28 | 0.0631 |

| ORS + ABB C22® | Day 1 - Day 14 | 1.803 | 1.132 - 2.47 | <.0001 |

| ORS + ABB C22® | Day 3 - Day 14 | 1.178 | 0.499 - 1.86 | 0.0002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).