1. Symptomatic Slow-Acting Drugs for Osteoarthritis

Symptomatic slow-acting drugs for osteoarthritis (SySADOAs) are a class of drugs characterized by a symptomatic effect on osteoarthritis (OA) with delayed onset (1 to 3 months) but prolonged action, and with efficacy persisting for several months after discontinuing treatment. This class of drugs includes chondroitin (sulfated [CS] or not), diacerein, glucosamine (sulfated [GS] or not), avocado-soybean unsaponifiables (ASUs), and intra-articular hyaluronic acids (IAHA).

These drugs primarily aim to reduce pain and improve functional status. Their efficacy has mainly been studied in knee and hip OA, as well as in hand OA for some of them.

The SySADOA class of drugs was first described in the 1990s [

1,

2] and then internationalized by Michel Lequesne [

3].

There are many preparations available containing one or more of these products as active compounds. In most countries, they are considered as dietary supplements and sold over the counter. However, in some countries, including France, some of these preparations — historically the oldest — are classified as drugs due to their pharmaceutical grade, preparation and production methods, and are or have been covered by national health systems/health insurances.

These medicines are generally well tolerated, apart from diacerein, which causes frequent diarrhea and, in some cases, hepatitis. For this reason, European health authorities have prohibited its use in patients over 65 years old.

Treatment recommendations for the management of OA (knee, hand, and hip) currently vary widely regarding SySADOAs. The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology recommends them as symptomatic treatments with no structural effect in knee and hip OA [

4,

5], but only advises the use of chondroitin (specifically CS) in its recent guidelines for the management of hand OA [

6] based on a high-quality randomized controlled trial [

7]. The American College of Rheumatology does not recommend using them, except for IAHA, which can be used under certain conditions [

8]. The OsteoArthritis Research Society International (OARSI) also does not recommend them, except for IAHA [

9]. The European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO) has issued positive recommendations for CS and GS of pharmaceutical grades, as well as for IAHAs as second- or third-line treatments [

10]. Finally, the French Society of Rheumatology's guidelines for the management of knee OA positively recommend their use as symptomatic treatments, including IAHA [

11]. So do also other national societies of rheumatology therapeutic recommendations for the management of OA, in many countries.

These drugs have been widely copied, and today, many different preparations marketed as “dietary supplements” or “nutraceuticals” are available for each of them on the OA and joint health market.

Consequently, there is a wide variety of products containing chondroitin and glucosamine (sulfated or not), the two most commonly reproduced compounds, which are often combined with each other or other ingredients.

These chondroitin and glucosamine preparations vary significantly regarding their extraction methods and purification techniques, resulting in notable differences in content, composition, purity, bioavailability, biological effects, and safety [

12]. Chondroitin is a major glycosaminoglycan in the structure of the cartilage matrix (notably playing a role in its hydration).

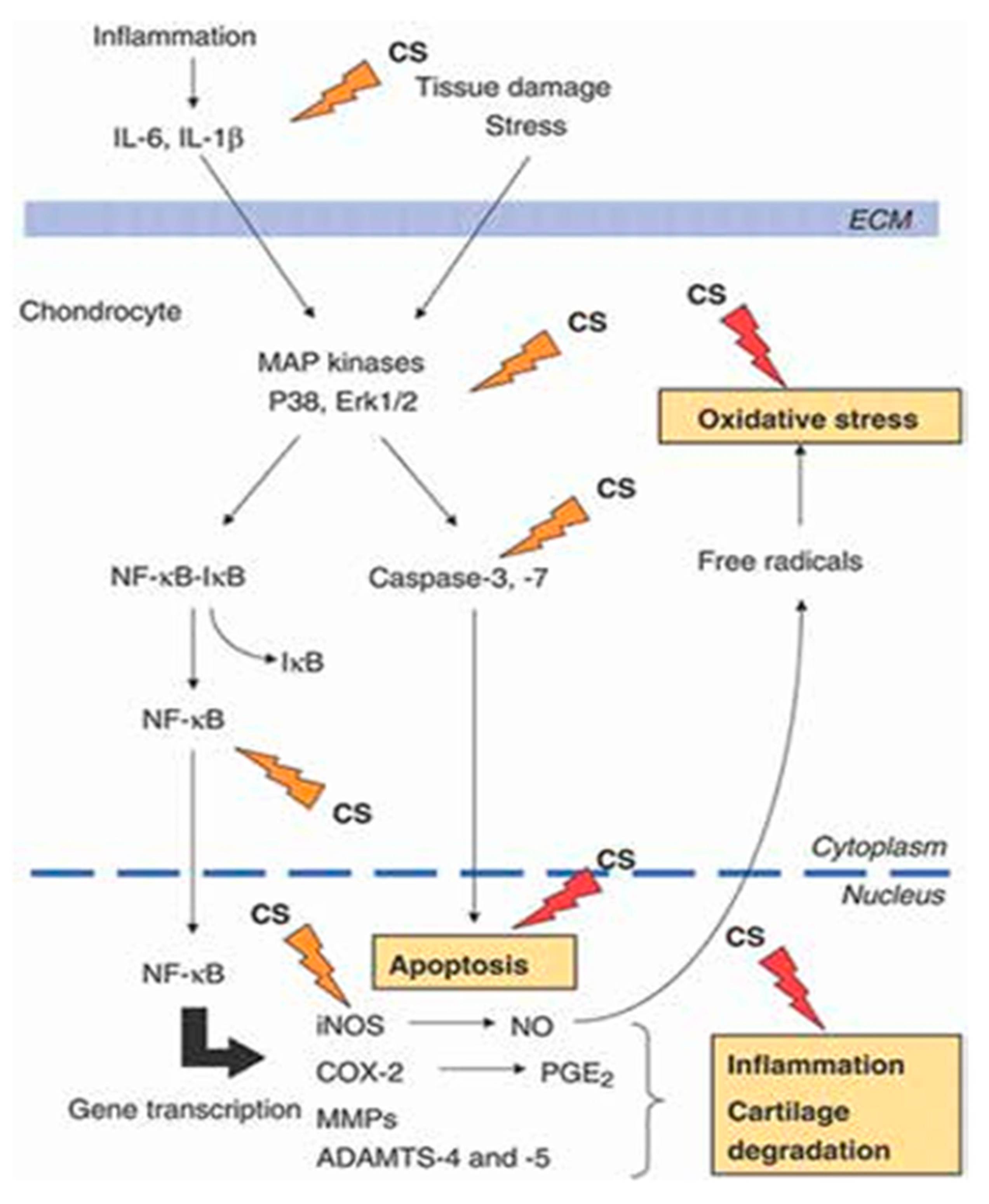

Figure 1 summarizes the potential pathophysiological targets of CS on the chondrocyte in OA.

Glucosamine and chondroitin are linked to proteoglycans in the cartilage matrix. In available dietary supplements, they may be sulfated or not, and the doses vary greatly (ranging from 50 to 500 mg per dosage unit for glucosamine and from 50 to 400 mg for chondroitin).

To illustrate the variety of preparations that mimic brand-name medicines,

Figure 2 shows the ASU-containing products listed by Christiansen et al. in their literature review on ASUs [

14].

Initially reimbursed in France, SySADOAs have undergone a succession of suppression of reimbursements: from 65% to 35%, then to 15%, and finally a total delisting on March 1, 2015, for glucosamines—the last SySADOAs to be cancelled from reimbursement after ASU, diacerein, and CS. These medicines are now sold at free with widely varying prices in pharmacies.

2. Dietary Supplements and Nutraceuticals for Joint Health and Osteoarthritis

Dietary supplements take the form of capsules, tablets, liquids, or powders. They are designed to “correct nutritional deficiencies”, maintain adequate nutrient intake, and support specific physiological functions according to international regulatory definitions. They are not medicines and, as such, they cannot claim to have pharmacological, immunological, or metabolic effects. Therefore, they are not intended to treat or prevent diseases in humans or modify physiological functions. The regulations governing them vary from country to country, including differences within the European Union.

Nutraceuticals (formed from the words “nutrition” and “pharmaceutical”) are substances supposed to have therapeutic and nutritional effects. There is a growing demand for them. However, due to the varying legislation in different countries, nutraceuticals face safety issues and challenges in justifying health claims. They can be defined as food or parts of food products that provide medical benefits, including the prevention and/or treatment of diseases.

Additionally, the term “nutraceutical” is commonly used in marketing, but it has no consensual regulatory definition. Currently, these products are not subject to specific regulations regarding their composition, manufacturing, packaging, etc. In the United States, the term is not even defined by legislation.

Following the launch of SySADOAs, a large number of dietary supplements for joint health have been commercialized. These supplements vary greatly in presentation, composition, and dosage. Currently, France ranks third in Europe for dietary supplement consumption [

15].

A comprehensive search of joint supplements available in France in early 2024 yielded a list of no fewer than 1,462 products (including all products, with different dosages, presentations, and unit counts per box).

Figure 3 shows the six main products currently used in France by patients with OA. Most contain chondroitin and/or glucosamine, sulfated or unsulfated.

These supplements are currently dispensed freely by pharmacists without any prescription in most cases, at the patient's request. They are not reimbursed, and their prices vary considerably from one pharmacy to another. Additionally, they are widely distributed and available for direct order online, as well as sold in some supermarkets. This is also the case in many other countries worldwide.

Searching for the words “chondroitin”, “glucosamine”, “avocado-soybean unsapo-nifiables”, and “diacerein” in France yields the following results for medicines: CS: Chondrosulf® 400, 800, or 1200 mg and Structum® 500; diacerein: ART 50 mg, Zondar 50, and Diacérhéine Biogaran 50; GS: Osaflexan 1178 mg and Dolenio 1178 (discontinued in 2022); glucosamine hydrochloride: Flexea® 625, Structoflex® 625, and Voltaflex® 625; ASU: Piasclédine® 300 mg.

Unlike medicines, the European Food Safety Authority has ruled that dietary supplements containing CS—i.e., non-medication products—are not entitled to make joint health claims, since data on the efficacy of CS in OA have been systematically obtained from randomized, controlled clinical trials involving the pharmaceutical grade CS, as detailed below.

Similarly, regarding GS-containing dietary supplements, claims of effects on “mobility” or “joint surface health”, as well as claims of “slowing down the process of cartilage destruction and consequently reducing the risk of OA”, have been prohibited since 2012.

3. Clinical Evidence of the Efficacy and Safety of SySADOAs

A large number of randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials have been conducted and published. These trials mainly involved CS [16-23], GS [24-30], ASUs [31-36], and to a lesser extent, diacerein [

37,

38]. A key point is that nearly all of these trials were conducted using medicines in patients with radiologically advanced, symptomatic OA. As for chondroitin and glucosamine, an academic initiated trial was conducted using non-pharmaceutical-grade CS and glucosamine hydrochloride. The results were negative overall, but a significant improvement in pain and functional discomfort versus placebo in the most symptomatic patients at baseline was reported [

39], which seems consistent with the effects of these treatments.

As for chondroitin, a recent review by Honvo et al. [

29] found only two trials involving a dietary supplement and products of various origins without further specification, as shown in

Table 1.

The extensive 2015 Cochrane review of chondroitin [

23] lists 43 controlled trials versus placebo or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs using chondroitin (unspecified whether sulfated or not), either alone or in combination with glucosamine. It does not specify whether the preparation administered to patients was a pharmaceutical grade or a supplement and concludes that chondroitin has a statistically significant and clinically meaningful effect on the symptoms of knee or hip OA (pain and functional discomfort measured by the Lequesne index [

40]). The Cochrane group also points to a possible structural effect in terms of slowing radiographic joint space narrowing. In the conclusion of this review, chondroitin is described as a “dietary supplement”.

Several randomized, placebo-controlled trials have been conducted on large patient populations (up to 400 patients) over treatment periods of 2 or 3 years to evaluate the potential structural effects of these drugs. All trials used pharmaceutical-grade preparations, notably for CS and GS. In general, these studies concluded that CS [

21,

22], GS [

25], ASU [

34,

35] and diacerein [

37] may have a structural effect on knee OA in the case of CS and GS, or on hip OA in the case of ASU and diacerein, as measured by a reduction in joint space narrowing on standard radiographs (coxo/gonometry developed by Lequesne [

41]) compared to the placebo groups.

Finally, two randomized controlled trials on finger OA have been published to date. The first was an academic study [

20], comparing CS with placebo and concluded that it was effective in reducing pain and functional discomfort (Functional Index for Hand Osteoarthritis [

42]). The other study compared diacerein to placebo, with no statistically significant difference on symptoms [

43].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis by Honvo et al. [

29].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis by Honvo et al. [

29].

| Study |

Location of OA |

Age of participants in treated groups (mean ± SD) |

Nature of the compound (brand) |

CS daily dose |

Treatment duration (weeks) |

Outcome(s) data extracted for analyses |

Concomitant anti-OA medication allowed |

| Bourgeois et al. [28] |

Knee |

Active a: 63.0 ± 11.0

Active b: 63.0 ± 9.0

Placebo: 64.0 ± 8.0 |

Pharmaceutical-grade (IBSA) |

1 × 1200 mg

3 × 400 mg |

13 weeks |

Spontaneous pain, VAS; LI, total score |

NSAIDs |

| Bucsi and Poor [29] |

Knee |

Active: 60.6 ± 9.6

Placebo: 59.4 ± 9.0 |

Pharmaceutical-grade (IBSA) |

1 × 800 mg |

26 weeks |

Pain during activity, VAS; LI, total score |

None |

| Clegg et al. [30] |

Knee |

Active: 58.2 ± 10.0

Placebo: 58.2 ± 9.8 |

NA (various suppliers) |

3 × 400 mg |

24 weeks |

WOMAC pain |

None |

| Fransen et al. [31] |

Knee |

Active: 59.5 ± 8.0

Placebo: 60.6 ± 8.1 |

Dietary supplement (TSI Health Sciences, Australia) |

2 × 400 mg, once daily |

104 weeks |

WOMAC pain |

Opioids, NSAIDs |

| Gabay et al. [32] |

Hand |

Active: 63.9 ± 8.5

Placebo: 63.0 ± 7.2 |

Pharmaceutical-grade (IBSA) |

1 × 800 mg |

26 weeks |

VAS global pain |

None |

| Kahan et al. [33] |

Knee |

Active: 62.9 ± 0.5

Placebo: 61.8 ± 0.5 |

Pharmaceutical-grade (IBSA) |

1 × 800 mg |

104 weeks |

WOMAC pain |

NSAIDs |

| Mazieres et al. [34] |

Hip or knee |

Active: 64.5 ± 1.14

Placebo: 63.3 ± 1.07 |

Pharmaceutical-grade (Pierre Fabre) |

2 × 1000 mg |

13 weeks |

Pain VAS; LI, total score |

NSAIDs |

| Mazieres et al. [35] |

Knee |

Active: 67.3 ± 7.8

Placebo: 66.9 ± 8.0 |

Pharmaceutical-grade (Pierre Fabre) |

2 × 500 mg |

13 weeks |

Pain during activity, VAS; LI, total score |

NSAIDs |

| Mazieres et al. [36] |

Knee |

Active: 66.0 ± 8.8

Placebo: 66.0 ± 7.7 |

Pharmaceutical-grade (Pierre Fabre) |

2 × 500 mg |

24 weeks |

Pain on activity, VAS; LI, total score |

NSAIDs |

| Michel et al. [55] |

Knee |

Active: 62.5 ± 9.1

Placebo: 63.1 ± 10.7 |

Pharmaceutical-grade (IBSA) |

1 × 800 mg |

104 weeks |

WOMAC pain |

NSAIDs |

| Möller et al. [37] |

Knee |

Active: 58.6 ± 11.4

Placebo: 61.0 ± 10.4 |

Pharmaceutical-grade (Bioibérica) |

2 × 400 mg, once daily |

13 weeks |

Pain VAS; LI, total score |

None |

| Monfort et al. [38] |

Knee |

Active: 63.7 ± 7.6

Placebo: 65.6 ± 6.2 |

Pharmaceutical-grade (Bioibérica) |

1 × 800 mg |

17 weeks |

Knee interline pressure test, pain on NRS |

None |

| Railhac et al. [39] |

Knee |

Active: 63.6 ± 8.2

Placebo: 66.5 ± 8.1 |

Pharmaceutical-grade (Pierre Fabre) |

2 × 500 mg |

48 weeks |

Pain on motion, VAS; LI, total score |

NSAIDs |

| Reginster et al. [13] |

Knee |

Active: 65.5 ± 8.0

Placebo: 64.9 ± 8.0 |

Pharmaceutical-grade (IBSA) |

1 × 800 mg |

26 weeks |

Pain VAS; LI, total score |

None |

| Uebelhart et al. [40] |

Knee |

Active: 60.0 ± 13.0

Placebo: 57.0 ± 11.0 |

Pharmaceutical-grade (IBSA) |

1 × 400 mg |

52 weeks |

Spontaneous pain, VAS |

None |

| Uebelhart et al. [41] |

Knee |

Active: 63.2 ± 9.1

Placebo: 63.7 ± 8.1 |

Pharmaceutical-grade (IBSA) |

1 × 800 mg |

26 weeksa

|

Spontaneous pain, VAS; LI, total score |

None |

| Wildi et al. [42] |

Knee |

Active: 59.7 ± 9.4

Placebo: 64.9 ± 9.5 |

Pharmaceutical-grade (Bioibérica) |

2 × 400 mg |

26 weeks |

WOMAC pain |

NSAIDs |

| Zegels et al. [43] |

Knee |

Active a: 65.4 ± 10.4

Active b: 65.3 ± 8.8

Placebo: 64.9 ± 10.6 |

Pharmaceutical-grade (IBSA) |

1 × 1200 mg

3 × 400 mg |

13 weeks |

Global pain, VAS; LI, total score |

None |

4. Pharmaceutical-Grade SySADOAs versus Supplements/Nutraceuticals: The Example of CS

Are Chondroitin Supplements and Medicines Biologically Equivalent?

Stellavato et al. compared the qualities and biological properties of dietary supplements versus pharmaceutical preparations of CS in two studies, one on European products [

44], the second on products available in the United States [

45]. In the European study, ten supplements were compared with two CS pharmaceutical-grade products. The American study compared three supplements and two pharmaceutical-grade products.

Neither the European CS supplements, nor those marketed in the USA, have demonstrated the properties and biological effects of CS pharmaceutical-grade preparations on the various pathophysiological targets in OA in these two studies carried out in vitro on cell cultures.

CS dietary supplements had lower purity and higher residue levels than medicines; all supplements had some non-soluble fraction. They all contained keratan sulfate, which made up more than 50% of the total level of glycosaminoglycans declared on the label. Nine of the ten supplements in the European study and all three American supplements contained far less chondroitin than indicated on the label.

Cells treated with samples that were diluted to present the same concentration of chondroitin in the medium exhibited cytotoxicity for seven out of ten of the dietary supplements, while the CS drugs preserved their viability. Pharmaceutical-grade CS products reduced the NF kappa B pathway (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer pathway of activated B cells), which is associated with the pathophysiology of OA, by increasing in vitro and vivo (animal models) the expression of inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-1 beta, tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, cyclooxygenase-2, chemokines and colony-stimulating factors, and were shown to regulate cartilage oligometric matrix protein (COMP) and hyaluronidases.

Analyses of the American supplements produced similar conclusions [

45]. The bioavailability and plasma concentration of pharmaceutical-grade preparations, particularly GS, correspond to levels of potential clinical efficacy.

Restaino et al. [

46], assuming that the manufacturing of chondroitin or glucosamine supplements for anti-OA purposes is not subject to the same quality control rules as pharmacological-grade preparations, analyzed 25 supplements versus two pharmaceutical-grade products from eight European countries, using high-resolution chromatography, amperometric detection, triple detection chromatography, capillary electrophoresis, single- and two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and cell models of human chondrocytes and synoviocytes to study their biological effect. Of the 25 samples, 19 contained up to 60.3% less chondroitin and/or glucosamine than indicated on the packaging. All the supplements showed high levels of keratan sulfate contamination, up to 47%. Additionally, CS of various animal origins and molecular weights were identified in over 32% of the samples. Only one sample had an in vitro biological effect almost comparable to that of the drugs.

These three studies suggest that dietary supplements are far from having the physicochemical qualities and biological properties of pharmaceutical-grade preparations, which are a prerequisite for a positive effect on patients' joint health.

This is endorsed by the ESCEO working group led by Bruyère et al. [

47], which emphasized that, based on available evidence, the ESCEO favors the use of CS or GS products judiciously selected for their pharmaceutical qualities, in order to optimize clinical benefit and patient compliance. This recommendation to use only evidence-based formulations also applies to other SySADOAs (ASU, diacerein).

ASUs at a dose of 300 mg were clinically compared with pharmaceutical-grade CS in 361 patients with femorotibial gonarthrosis over 6 months, with good clinical efficacy in both treatment groups, in terms of pain and functional discomfort (-4 points on the Lequesne index), and good tolerability (gastrointestinal effects in both groups, judged to be unrelated to the treatments) [

48]. This is one of the few comparisons between Sy-SADOAs, apart from studies of CS or GS versus the combination of the two.

However, to our knowledge, no clinical trial has compared a SySADOA with its dietary supplement counterpart.

As far as ASUs are concerned, to the best of our knowledge, all controlled clinical trials conducted in knee and/or hip OA have used the controlled drug preparation reimbursed in France and other countries, and not ASU-NMX 1000TM (Nutramax Laboratories Inc., Edgewood, MD, USA). It was noted that in the latter preparation, a dietary supplement, one of the main molecules of the original ASUs, citrostadienol, was absent, and that the tocopherol content (which is very high in pharmaceutical-grade ASUs) was very low.

Similarly, trials involving CS, GS drugs, and diacerein in OA have always been conducted with pharmaceutical-grade preparations.

5. Combination of CS and/or GS + Other Products: The Realm of Supplements

Many combinations with CS can be found in literature, starting with the common combination of CS + glucosamine sulfated or not.

There are also a wide variety of “soups” combining a large number of components: CS + GS + collagen + vitamin D + harpagophytum, curcumin, ginger, etc.

In addition, there are combinations of a more limited number of products such as CS + omega 3 or 6, CS + S adenosyl-methionine, and CS + collagen. Given that the vast majority of these products have never been evaluated in randomized controlled clinical trials, there is clearly no evidence of any added value of these different compounds compared to pharmaceutical preparations of CS or GS alone.

Searches on PubMed to identify available literature yield variable results, depending on the keywords selected

“Dietary supplements vs. drugs-and-osteoarthritis”: 10 articles. These include six randomized placebo-controlled trials involving Phytalgic, vitamin E, natural mineral algae-derived supplements (Aquamin F), Phellodendron and citrus fruits, methylsulfonyl-methane (MSM) and boswellic acid, garlic supplements, and shea nut oil extracts, a review of four clinical trials with green-lipped mussels, a trial carried out in Russia, a study in rats and, finally, a paper on the characterization of supplement consumers in the United States.

“Dietary supplements-and-osteoarthritis”: 671 articles. Recent papers relevant to our article include 1/a literature review on curcumin by Bannuru [

49], 2/a systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of ginger in gonarthrosis by Araya-Quintallina [

50], 3/another meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials testing the efficacy of ginger in OA by Bartels et al. [

51], 4/and finally, a meta-analysis of the impact of dietary supplements on OA symptoms by Mathieu et al. [

52].

“SySADOA-and-nutraceutical-and-osteoarthritis”: 9 articles. A very comprehensive review of alternative treatments and supplements was recently published by our ESCEO working group [

53]. Alongside autologous cartilage graft techniques, cell therapies (mesenchymal cells), and platelet extracts (platelet-rich plasma), a large number of products have been identified and listed for use in OA as supplements and/or nutraceuticals: vitamin D, oral or intra-articular collagens, methylsulfonylmethane (MSN), S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe), curcumin and boswella, harpagophytum, ginger, marine pine extracts, polyphenols, green tea, and “cat's claw” (non-exhaustive list).

In summary, there is very limited clinical evidence to suggest the symptomatic efficacy of oral collagens, MSM, SAMe, curcumin, and ginger. Meta-analyses for the latter two products are positive but raise the problem of the variety of dosages available on the market and tested in trials. Adverse effects are rare, but ginger may be associated with an increased risk of (moderate) gastrointestinal effects.

This review concludes on alternative treatments, including dietary supplements, that: “for all the treatments analyzed, problems with trial designs limit the degree to which it is possible to draw conclusions about their clinical efficacy in OA. Clearly, none of them would pass the hurdle of regulatory approval if they were to be evaluated in the same way as current pharmaceutical treatments. However, there is not enough evidence to declare them completely ineffective. They therefore represent an area for which new, well-designed, large-scale, blinded randomized trials are needed” [

53].

6. Medicines Versus Supplements: What About Quality Standards and Safety?

As previously mentioned, the definitions of supplements and nutraceuticals, regulatory and quality standards, and compliance with these standards vary widely between countries within the European Union.

In most cases, there is no control of the quantities/doses of the components contained in end-product supplements. This contrasts with the strict standards and quality controls that accompany and govern the manufacturing and composition of a pharmaceutical preparation, notably the verification of the absence of impurities.

An investigation by the French Directorate General for Competition, Consumer Affairs and Fraud Control carried out in 2017 on dietary supplements promoted for OA analyzed 43 samples. Of the 43, over 50% were non-compliant: the quantities of CS and/or GS were different from those declared on the composition label. Quantities were generally below the advertised specifications, except in four cases where they exceeded the authorized limits for supplements [

54].

Standards are therefore not respected in terms of product description and the quantities of the various components contained in the product. The absence of effective quality controls during the production process results in the presence of impurities in the finished product. Thus, of the 10 European supplements studied by Stellavato [

44], 80% contained unsulfated chondroitins and impurities, including insoluble components, potentially plant residues, in significant quantities. Keratan sulfate was also present in 100% of cases, with levels as high as 47.9% in some products. The authors also found undeclared proteins and “indeterminate” substances that they were unable to identify in advanced chromatographic analysis.

Tolerance and Safety

These worrying observations cast a harsh light on the tolerance and safety problems associated with dietary supplements. While tolerance and possible adverse effects are known, listed (on the official and reglementary product sheet), and monitored for pharmaceutical preparations, there is virtually no “dietary supplement vigilance” or “nutraceutical vigilance” system in place. Potential adverse effects are not mentioned to patients by physicians, and above all by the pharmacists who sell these products, nor, consequently, are they monitored and centralized by authorities capable of creating an alert, should the need arise. What about treatment discontinuation due to intolerance? What about notifications of effects such as, for example, certain coagulation disorders that can occur with glucosamines in patients on anti-vitamin K or coumarin drugs?

Many products sold as supplements contain a large number of components – up to 10 or even 15 – which, in the event of an adverse effect, raises the question of which molecule is responsible and how to identify it. In addition, as previously mentioned, there is a considerable level of impurities and protein residues in unacceptable quantities, representing an additional potential source of danger.

All this is all the more worrying for food supplements, as they are very commonly considered by the public to be safe because they are perceived as “natural”, and what is “natural” is obviously seen as risk-free. This contrasts with drugs, which are known to be dangerous and the source of many adverse effects. Thus, there is a paradox between the use of products with proven efficacy in OA, whose tolerability is known and, in principle, monitored, but which, as drugs, are suspect in the eyes of the public – and sometimes even caregivers, including a number of pharmacists – and supplements with random production and quality conditions that are perceived as “natural” and completely harmless.

In reality, dietary supplements for OA are responsible for numerous adverse effects. Between 2009 and 2018, 74 reports of adverse reactions were recorded in France: hematological, gastroenterological, hepatic, and dermatological disorders; drug interactions, notably with vitamin K antagonists (for glucosamines). These reports underline the importance of consulting a healthcare professional, ongoing monitoring, and appropriate risk management for patients [

55,

56].

The issue of the safety of over-the-counter dietary supplements available in pharmacies and online is a general subject, not specific to supplements for OA or joint health.

An article published in the French newspaper

Le Monde on March 5, 2025 sounds the alarm about the dangers of Garcinia cambogia, a plant used in numerous “appetite suppressant” preparations to lose weight [

57]. The article points out that, although banned from pharmaceutical products since 2012, Garcinia cambogia – or Malabar tamarind – continues to be used in dietary supplements for weight loss – some 340 are marketed, mainly on the Internet. Between 2009 and March 2024, 38 cases of adverse reactions were reported in France: often serious hepatic, psychiatric, digestive (pancreatitis), cardiac, and muscular disorders. Some of these reactions have even been fatal. At present, European regulations do not prevent the use of health claims put forward by manufacturers of Garcinia cambogia-based dietary supplements: “weight control”, “reduced fat storage” and “reduced hunger”, “control of glycemia and cholesterol levels”. The

Le Monde article concludes with a quote from Philippe Besset, President of the French Federation of Pharmaceutical Unions, which represents 7,250 of France's 20,000 pharmacies: “I cannot accept that a dangerous product is sold in pharmacies: I will immediately relay the information to dispensing pharmacists with a recommendation to withdraw it from sale.” “When there's an alert from the French medicines agency, we receive a warning message in red on all French pharmacy workstations, saying ‘Withdraw the product’. This happens quite frequently, when a batch is defective... but this story concerns a dietary supplement, and many pharmacists don't have the information”.

This clearly establishes the dilemma of dietary supplements versus drugs, from the point of view of risk management and tolerance. And the pharmacist, as the main supplier of supplements in the pharmacy, has a very important role to play in providing information, as well as monitoring any adverse effects.

Likewise, physicians, and rheumatologists in particular when it comes to OA, have a role to play in this regard. Pharmaceutical-grade SySADOAs have demonstrated their effectiveness, albeit modest, in OA of the lower limbs, and in finger OA for CS. They are cited and supported in European and French guidelines for the management of OA. Thus, it is up to practitioners to prescribe them as treatments associated with other OA management modalities and to warn patients, with pedagogy, against any “substitution” of this prescription, on the one hand, and against the use of dietary supplements with often questionable qualities, on the other. Under these conditions, pharmaceutical-grade SySADOAs and, perhaps, provided additional evidence, certain supplements (collagen, curcumin, ginger, at validated dosages) could become part of the therapeutic landscape for the management of OA. In October 2024, for example, the Italian Society of Rheumatologists launched a 1-year project to clarify the efficacy, tolerability, and use of dietary supplements for OA [

58].

The problem of production conditions, the standards to be applied to dietary supplements, and the conditions under which they could be promoted for “prevention” or in certain pathological situations, was also the subject of a series of position papers issued in early 2025 by leaders in the field, including the US FDA on the HBW insight webpage: “Food Supplements In 2025: The Regulatory Challenges And Opportunities On The Horizon” [

59].

7. Conclusions

In conclusion, a wide-ranging public health debate is underway to bring order to the field of dietary supplements, and regulate their production, safety, distribution, and conditions of use.

In OA, SySADOAs (now poorly copied by dietary supplements) have proved their worth, and their use is recommended for symptomatic patients. As is often the case, it is better to opt for original products rather than imitations, and therefore to have these drugs prescribed by healthcare professionals – first and foremost pharmacists and physicians, especially rheumatologists – with information given to the patients regarding their effects, kinetics of action, and duration of use, as well as any monitoring required.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Cremer Consulting for its help in the translation and reviewing of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares he has perceived honorarium for consultancy or being speaker at symposia, or invitations at congresses by Carilène, Expanscience, IBSA, TRB in the past 3 years.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASU |

Avocado-soybean unsaponifiable |

| CS |

Chondroitin sulfate |

| ESCEO |

European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases |

| GS |

Glucosamine sulfate |

| IAHA |

Intra-articular hyaluronic acid |

| MSN |

Methylsulfonylmethane |

| OA |

Osteoarthritis |

| SAMe |

S-adenosylmethionine |

| SySADOA |

Symptomatic slow-acting drugs for osteoarthritis |

References

- Maheu, E.; Dropsy, R. Definitions and clinical experimentation of anti-osteoarthritis agents/chondro-protectors. Survey among private rheumatologists. Rev. Rhum. Mal. Osteoartic. 1990, 57, 44S–50S, (French). [Google Scholar]

- Avouac, B.; Dropsy, R. Methodology of clinical trials of basic treatments of osteoarthritis. Therapie 1993, 48, 315–319. [Google Scholar]

- Lequesne, M. Symptomatic slow-acting anti-osteoarthritis drugs: a new therapeutic concept? Rev. Rhum. Ed. Fr. 1994, 61, 75–79, (French). [Google Scholar]

- Pendleton, A.; Arden, N.; Dougados, M.; Doherty, M.; Bannwarth, B.; Bijlsma, J.W.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a task force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2000, 59, 936–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Doherty, M.; Arden, N.; Bannwarth, B.; Bijlsma, J.; Gunther, K.P.; et al. EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of hip osteoarthritis: report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2005, 64, 669–681. [Google Scholar]

- Kloppenburg, M.; Kroon, F.P.B.; Blanco, F.J.; Doherty, M.; Dziedzic, K.S.; Greibrokk, E.; et al. 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of hand osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 78, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabay, C.; Medinger-Sadowski, C.; Gascon, D.; Kolo, F.; Finckh, A. Symptomatic Effects of Chondroitin 4 and Chondroitin 6 Sulfate on Hand Osteoarthritis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial at a Single Center. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 63, 3383–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolasinski, S.L.; Neogi, T.; Hochberg, M.C.; Oatis, C.; Guyatt, G.; Block, J.; et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020, 72, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannuru, R.R.; Osani, M.C.; Vaysbrot, E.E.; Arden, N.K.; Bennell, K.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A.; et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartil. 2019, 27, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruyère, O.; Honvo, G.; Veronese, N.; Arden, N.K.; Branco, J.; Curtis, E.M.; et al. An updated algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO). Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2019, 49, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellam, J.; Courties, A.; Eymard, F.; Ferrero, S.; Latourte, A.; Ornetti, P.; et al. Recommendations of the French society of rheumatology on pharmacological treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Joint Bone Spine 2020, 87, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitaloni, M.; Moller, I.; Vergès, J. SYSADOAs: do their origin and quality make a difference in efficacy and safety? Global Rheumatol. 2021, 2–24, (PANLAR Congress). [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier, X.; Conrozier, T. Access to highly purified chondroitin sulfate for appropriate treatment of osteoarthritis: ereview. Med. Access@Point Care. 2017, 1, e134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, B.A.; Bhatti, S.; Goudarzi, R.; Emami, S. Management of Osteoarthritis with Avocado/Soybean Unsaponifiables. Cartilage 2015, 6, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IQVIA OTCIMS - Food Supplement Market tous circuits - MAT à fin Déc 2023.

- Uebelhart, D.; Malaise, M.; Marcolongo, R.; DeVathaire, F.; Piperno, M.; Mailleux, E.; et al. Intermittent treatment of knee osteoarthritis with oral chondroitin sulfate: a one-year, randomized, double-blind, multicenter study versus placebo. Osteoarthritis Cartil. 2004, 12, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, B.A.; Stucki, G.; Frey, D.; De Vathaire, F.; Vignon, E.; Bruehlmann, P.; et al. Chondroitins 4 and 6 Sulfate in Osteoarthritis of the Knee. A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazières, B.; Hucher, M.; Zaïm, M.; Garnero, P. Effect of chondroitin sulphate in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2007, 66, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochberg, M.C.; Martel-Pelletier, J.; Monfort, J.; Möller, I.; Castillo, J.R.; Arden, N.; et al. Combined chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine for painful knee osteoarthritis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial versus celecoxib. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 75, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabay, C.; Medinger-Sadowski, C.; Gascon, D.; Kolo, F.; Finckh, A. Symptomatic effects of chondroitin 4 and chondroitin 6 sulfate on hand osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial at a single center. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 63, 3383–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahan, A.; Uebelhart, D.; DeVathaire, F.; Delmas, P.D.; Reginster, J.Y. Long-term effect of chondroitin 4 and 6 sulfate on knee osteoarthritis. The study on osteoarthritis progression prevention. A 2-year randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildi, L.M.; Raynauld, J.P.; Martel-Pelletier, J.; Beaulieu, A.; Bessette, L.; Morin, F.; et al. Chondroitin sulphate reduces both cartilage volume loss and bone marrow lesions in knee osteoarthritis patients starting as early as 6 months after initiation of therapy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study using MRI. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 982–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.A.; Noorbaloochi, S.; MacDonald, R.; Maxwell, L.J. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 1, CD005614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero-Beaumont, G.; Roman Ivorra, J.A.; Carmen Trabado, M.; Blanco, F.J.; Benito, P.; Martin-Mola, E.; et al. Glucosamine Sulfate in the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis Symptoms. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study Using Acetaminophen as a Side Comparator. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reginster, J.Y.; Deroisy, R.; Rovati, L.C.; Lee, R.L.; Lejeune, E.; Bruyere, O.; et al. Long-term effects of glucosamine sulphate on osteoarthritis progression: a randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2001, 357, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towheed, T.E.; Maxwell, L.; Anastassiades, T.P.; Shea, B.; Houpt, J.; Robinson, V.; et al. Glucosamine therapy for treating osteoarthritis (Review). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005, 2005, CD002946. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Altman, R.D.; Abramson, S.; Bruyere, O.; Clegg, D.; Herrero-Beaumont, G.; Maheu, E.; et al. Commentary: osteoarthritis of the knee and glucosamine. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006, 14, 963–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlad, S.C.; LaValley, M.P.; McAlindon, T.E.; Felson, D.T. Glucosamine for Pain in Osteoarthritis Why Do Trial Results Differ? Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56, 2267–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honvo, G.; Bruyère, O.; Geerinck, A.; Genovese, N.; Reginster, J.Y. Efficacy of chondroitin sulfate in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a comprehensive meta-analysis exploring inconsistencies in randomized placebo-controlled trials. Adv. Ther. 2019, 36, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruyère, O.; Reginster, J.Y.; Honvo, G.; Detilleux, J. Cost-effectiveness evaluation of glucosamine for osteoarthritis based on simulation of individual patient data obtained from aggregated data in published studies. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 31, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheu, E.; Mazieres, B.; Valat, J.P.; Loyau, G.; Le Loet, X.; Bourgeois, P.; et al. Symptomatic efficacy of avocado/soybean unsaponifiables in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee and hip: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial with a six-month treatment period and a two-month follow-up demonstrating a persistent effect. Arthritis Rheum. 1998, 41, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Blotman, F.; Maheu, E.; Wulwik, A.; Caspard, H.; Lopez, A. Efficacy and safety of avocado/soybean unsaponifiables in the treatment of symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee and hip. A prospective, multicenter, three-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Rev. Rhum. (Engl Ed.) 1997, 64, 825–834. [Google Scholar]

- Appelboom, T.; Schuermans, J.; Verbruggen, G.; Henrotin, Y.; Reginster, J.Y. Symptoms modifying effect of avocado/soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) in knee osteoarthritis. A double blind, prospective, placebo-controlled study. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2001, 30, 242–247. [Google Scholar]

- Lequesne, M.; Maheu, E.; Cadet, C.; Dreiser, R.L. Structural effect of avocado/soybean unsaponifiables on joint space loss in osteoartritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 47, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheu, E.; Cadet, C.; Marty, M.; Moyse, D.; Kerloch, I.; Coste, P.; et al. Randomised, controlled trial of avocado-soybean unsaponifiable (Piascledine) effect on structure modification in hip osteoarthritis: the ERADIAS study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, R.; Bartels, E.M.; Astrup, A.; Bliddal, H. Symptomatic efficacy of avocado-soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) in osteo arthritis (OA) patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008, 16, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dougados, M.; Nguyen, M.; Berdah, L.; Mazieres, B.; Vignon, E.; Lequesne, M. Evaluation of the structure-modifying effects of diacerein in hip osteoarthritis: ECHODIAH, a three-year, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 44, 2539–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rintelen, B.; Neumann, K.; Burkhard, F.L. A Meta-analysis of Controlled Clinical Studies with Diacerein in the Treatment of Osteoarthritis. Arch. Int. Med. 2006, 166, 1899–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, D.O.; Reda, D.J.; Harris, C.L.; Klein, M.A.; O’Dell, J.R.; Hooper, M.M.; et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lequesne, M.; Méry, C.; Samson, M.; Gérard, P. Indexes of severity for osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 1987, 65 Suppl, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadet, C.; Maheu, E. Évaluation radiographique de l’arthrose : critères et indices (Radiographic scoring in osteoarthritis). Rev. Rhum. (monographie) 2010, 77, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Dreiser, R.L.; Maheu, E.; Guillou, G.B.; Caspard, H.; Grouin, J.M. Validation of an algo functional index for osteoarthritis of the hand. Rev. Rhum. Engl. Ed. 1995, 62, 43s–53s. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, K.; Kim, J.W.; Moon, K.W.; Yang, J.A.; Lee, E.Y.; Song, Y.W.; Lee, E.B. The efficacy of diacerein in hand osteoarthritis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin. Ther. 2013, 35, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stellavato, A.; Restaino, O.F.; Vassallo, V.; Rosario Finamore, R.; Carlo Ruosi, R.; Cassese, E.; et al. Comparative Analyses of Pharmaceuticals or Food Supplements Containing Chondroitin Sulfate: Are Their Bioactivities Equivalent? Adv. Ther. 2019, 36, 3221–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stellavato, A.; Restaino, O.F.; Vassallo, V.; Cassese, E.; Finamore, R.; Ruosi, C.; et al. Chondroitin Sulfate in USA Dietary Supplements in Comparison to Pharma Grade Products: Analytical Fingerprint and Potential Anti-Inflammatory Effect on Human Osteoartritic Chondrocytes and synoviocytes. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restaino, O.F.; Finamore, R.; Stellevato, A.; Diana, P.; Bedidni, E.; Trifuoggi, M.; et al. European chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine food supplements: A systematic quality and quantity assessment compared to pharmaceuticals. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 222, 114984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruyère, O.; Cooper, C.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; Dennison, E.; Rizzoli, R.; Reginster, J.Y. Inappropriate claims from non-equivalent medications in osteoarthritis: a position paper endorsed by the European Society for Clinical And Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Muskuloskeletal Diseases. Aging Clinical Exp. Res. 2018, 30, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelka, K.; Coste, P.; Géher, P.; Krejci, G. Efficacy and safety of Piasclédine 300 versus chondroitin sulfate in a 6–months treatment plus 2 months observation in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Clin Rheumatol. 2010, 29, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannuru, R.R.; Osani, M.C.; El-Eid, F.; Wang, C. Efficacy of Curcumin and Boswellia for Knee Osteoarthritis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2018, 48, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya-Quintanilla, F.; Gutierrez-Espinoza, H.; Munoz-Yanez, M.J.; Sanchez-Montoya, U.; Lopez-Jeldes, J. Effectiveness of Ginger on Pain and Function in Knee Osteoarthritis: A PRISMA Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pain Physician 2020, 23, E151–E161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, E.M.; Folmer, V.N.; Bliddal, H.; Altman, R.D.; Juhl, C.; Tarp, S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of ginger in osteoarthritis patients: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015, 23, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, S.; Soubrier, M.; Peirs, C.; Monfoulet, L.E.; Boirie, Y.; Tournadre, A. A Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Nutritional Supplementation on Osteoarthritis Symptoms. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuggle, N.; Cooper, C.; Oreffo, R.O.C.; Price, A.J.; Kaux, J.F.; Maheu, E.; et al. Alternative and complementary therapies in osteoarthritis and cartilage repair. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enquête DGCCRF 2017.

- VIDAL. Les compléments alimentaires contre l’arthrose. Available online: https://www.vidal.fr/maladies/appareil-locomoteur/arthrose-rhumatismes/complements-alimentaires.html (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- ANSES. AVIS de l’Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l’alimentation, de l’environnement et du travail relatif « aux risques liés à la consommation des compléments alimentaires ». Maisons-Alfort; 2019 janv ; p. 51. Report No : « 2015-SA-0069 ».

- Le Monde. Les compléments alimentaires à base de « Garcinia cambogia » présentent des risques pour la santé, alerte l’Anses. 5 March 2025. Available online: https://www.lemonde.fr/sciences/article/2025/03/05/les-complements-alimentaires-a-base-de-garcinia-cambogia-presentent-des-risques-pour-la-sante-alerte-l-anses_6576519_1650684.html (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Collegio Reumatologi Italiani CReI. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/collegio-reumatologi-italiani-crei_reumatologia-crei-collegioreumatologi-activity 7294018397107847168N1hk?utm_source=social_share_send&utm_medium=android_app&utm_campaign=share_via (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- HBW insight webpage. Food Supplements In 2025: The Regulatory Challenges And Opportunities On The Horizon. By Tom Gallen. 28 January 2025. Available online: https://insights.citeline.com/hbwinsight/leadership/interviews/food-supplements-in-2025-the-regulatory-challenges-and-opportunities-on-the-horizon-NCCM2V4DWJCTFH7RSJKT4OBVQI/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).