1. Introduction

The global shift toward clean energy has accelerated the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs), particularly electric intelligent vehicles (EIVs), which integrate electric propulsion with advanced computing for real-time decision-making and communication. These systems support functions such as autonomous navigation and safety monitoring, requiring continuous data processing.

However, limited

battery capacity remains a key barrier, leading to

range anxiety—the concern that EVs may deplete power before reaching a destination [

1]. Addressing this involves optimizing both

driving behavior, such as

coasting [

2], and

energy-efficient computation [

3]. The vehicle’s

central processing unit (CPU) consumes significant energy by handling sensor and environment data, reducing the overall driving range.

Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) offers a solution by offloading tasks to nearby servers, improving energy efficiency and reducing latency. Full cloud reliance is often unsuitable for delay-sensitive tasks like collision avoidance due to network latency [

4]. Hybrid strategies, such as selective offloading based on urgency [

5], have emerged to balance responsiveness and efficiency.

Additionally, the growing volume of vehicular data challenges existing

bandwidth and

storage infrastructures. Recent approaches leverage

edge architectures, where

neighboring vehicles with spare resources participate in task execution. Studies such as [

6,

7] explore

virtual machine allocation and task classification techniques that distribute computation based on task characteristics.

Building on this, we introduce a three-tier task offloading framework:

Vehicular cloud: nearby peer vehicles

Roadside edge units (RSUs): local decision control

Central cloud: global task coordination

This architecture enables intelligent offloading across tiers to minimize system-wide energy use while maintaining latency and resource constraints. The offloading process is formulated as a non-linear integer programming (NLIP) problem, and solved using a genetic algorithm (GA) tailored for dynamic vehicular networks.

Our experiments show that the GA-based approach effectively reduces energy consumption, especially when vehicle density remains below 30, making it suitable for urban deployment with moderate traffic and limited edge resources.

2. System Model and Problem Formulation

This section presents the system architecture and models for computation and energy consumption.

2.1. Network Architecture

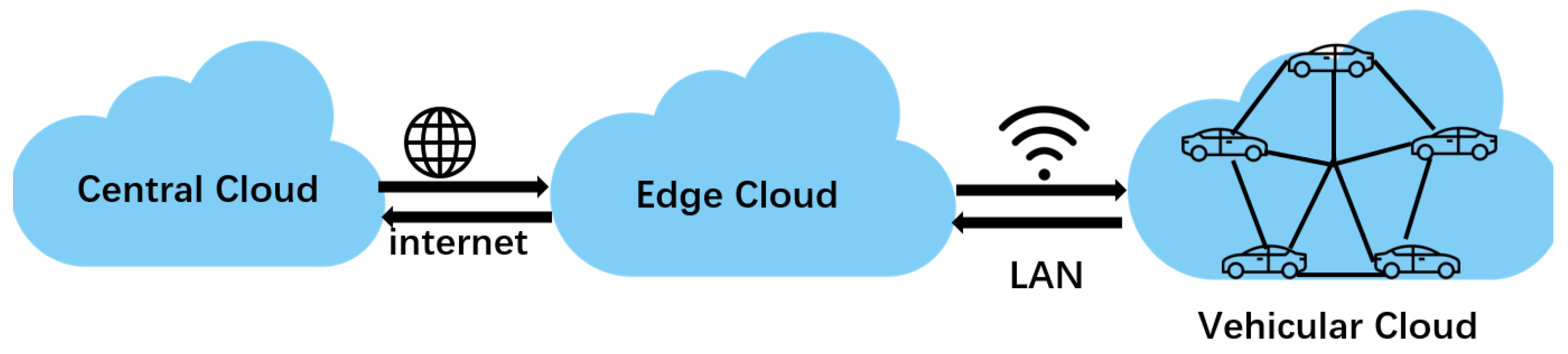

As depicted in

Figure 1, the system employs a hierarchical structure with three layers: vehicular cloud, roadside edge servers, and central cloud [

6]. Vehicles transmit real-time data (e.g., location, speed, destination) to the central cloud, which analyzes traffic and predicts the vehicle’s proximity to others within a future time window

T. This information is relayed to the edge layer, which classifies vehicles into task requesters and providers for resource sharing.

Table 1.

Notations Used in the Model

Table 1.

Notations Used in the Model

| Symbol |

Description |

| T |

Resource sharing duration |

|

CPU capacity of vehicle i at time t

|

|

Local computation workload |

|

Task load offloaded by vehicle j

|

|

MIPS of vehicle i

|

|

Estimated system parameter |

|

Total energy consumption of vehicle i

|

|

,

|

Receive/send energy of vehicle i

|

2.2. Computation Model

The resource sharing interval is , and the total number of vehicles is N. Each vehicle’s task is denoted by , where is the local workload, the offloadable portion, and the data size.

Let

be a binary matrix, where

indicates vehicle

i performs the task of vehicle

j. The constraint on computing capacity is:

The capacity

is computed as:

where

is CPU frequency and

,

are constants.

2.3. Energy Consumption Model

The energy use includes computational and communication components. Processing energy is modeled by:

When offloading reduces CPU frequency to

, the energy saved is:

Communication energy for data transfer depends on task size

and bandwidth

:

Receiving and sending energy per vehicle are:

Total energy per vehicle

i at time

t is:

The objective is to minimize total energy imbalance across all vehicles:

subject to the constraints:

and

3. Algorithms

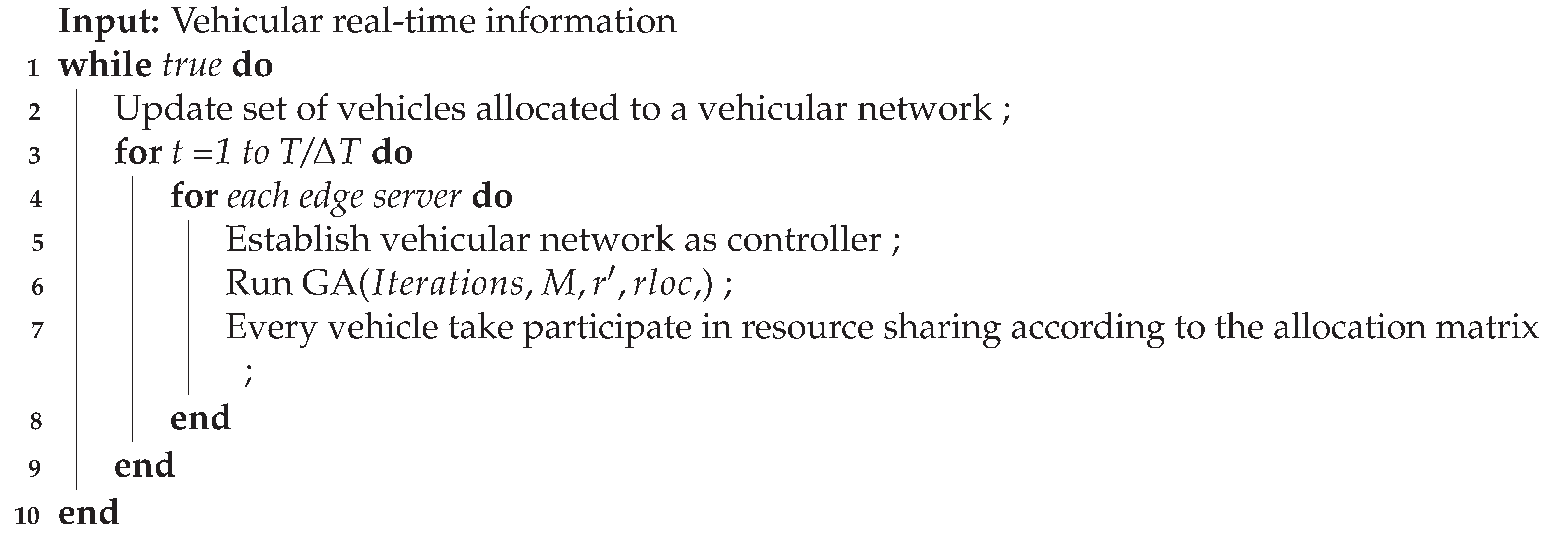

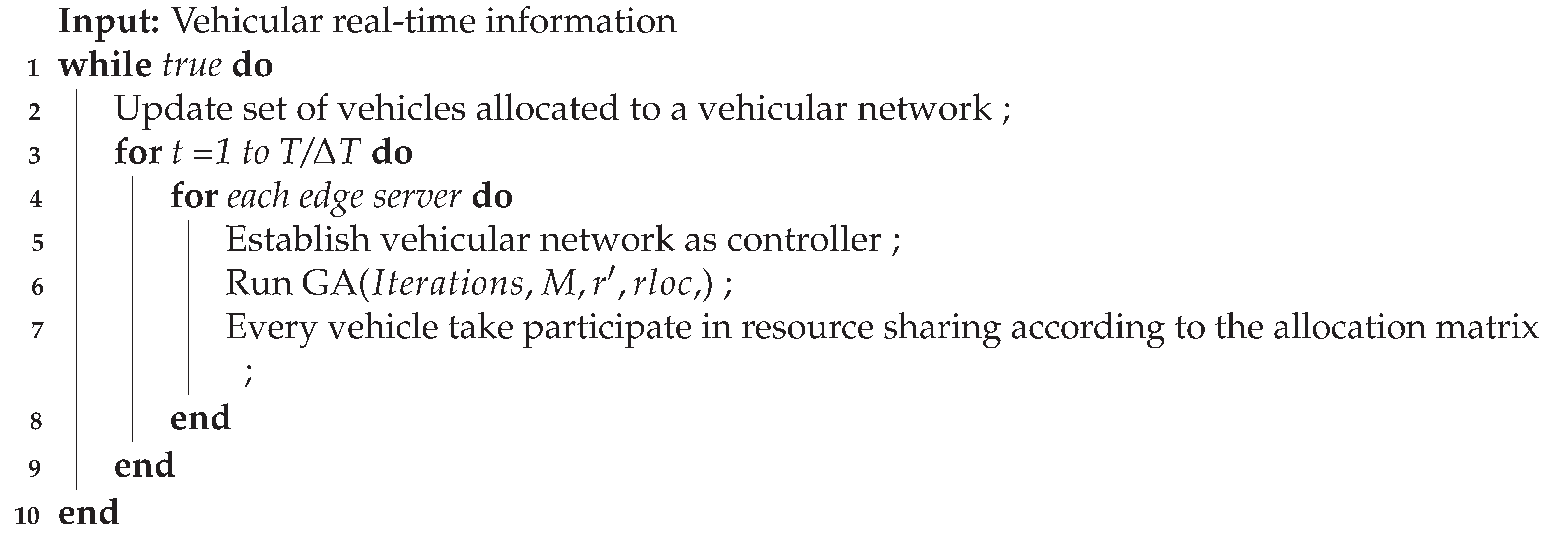

We design a greedy algorithm 1 to minimize the energy consumption of all time slot. For each moment, the central cloud returns the vehicles contained in each edge cloud and the time of participating in resource sharing, and all the edge cloud forms a vehicular cloud, then run genetic algorithm to minimize the energy consumption of a time slot.

|

Algorithm 1: Greedy algorithm |

|

Genetic algorithm is a adaptive heuristic optimization method, which is proposed by John Holland in 1970s[

8]. Based on Darwin’s theory of natural selection, it simulates the process of natural selection and reproduction to solve optimization problems. Similarly to individuals with favorable variation surviving , the solutions in the algorithm imitate the behavior of chromosomes, such as the mutations of genes and the crossovers of chromosomes. In recently, the genetic algorithm has been used for real-time path planning[

9], maximum coverage deployment in Wireless Sensor Networks[

10], and intrusion detection[

11].

In genetic algorithm, a population is composed of randomly generated solutions, and all individuals in the population are composed of encoded strings similar to chromosomes[

12]. Similar to natural selection, with the iteration, the diversity decreases, but the preserved individuals are excellent adaptive individuals. In other words, the preserved solutions are are locally optimal.

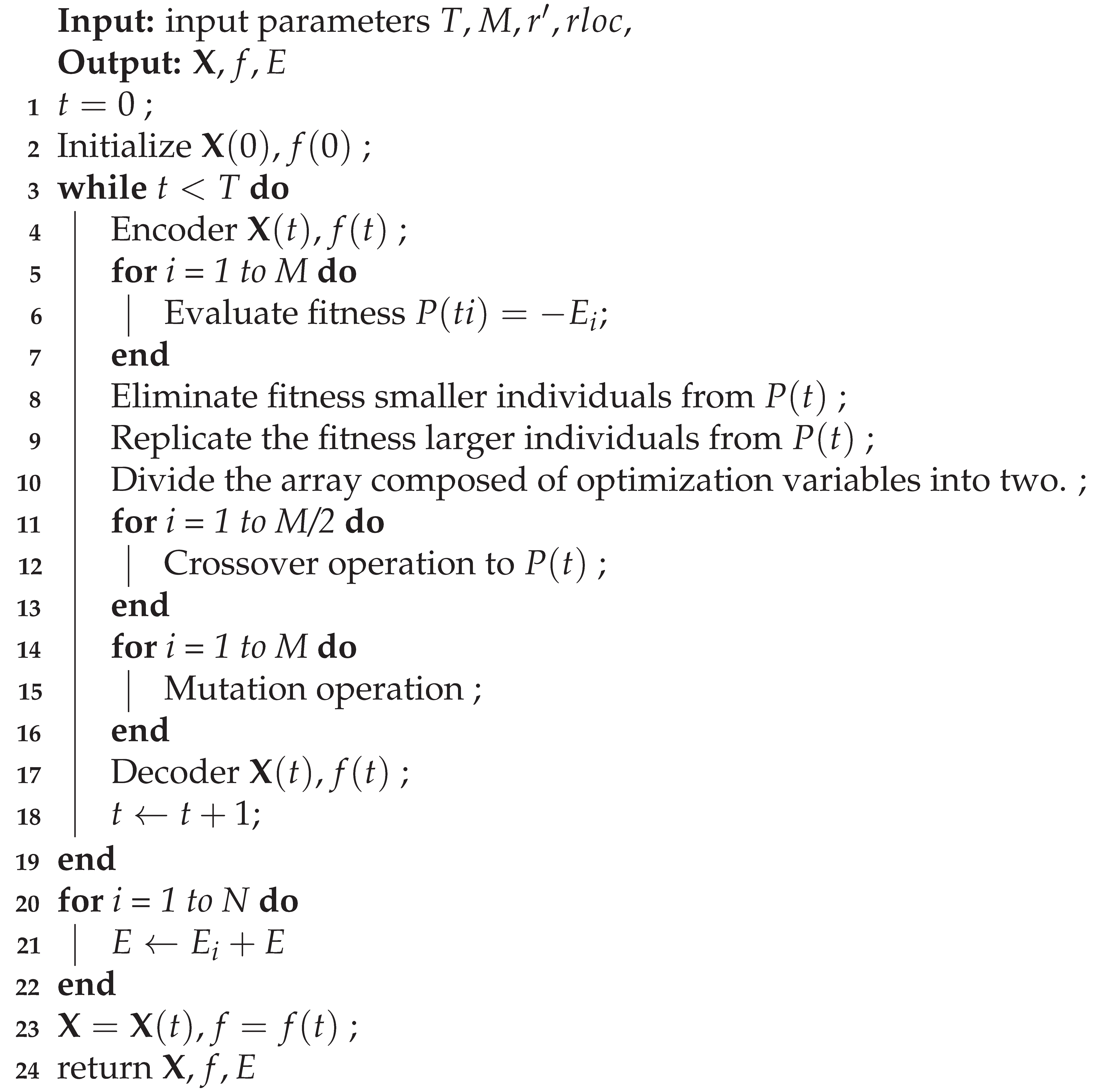

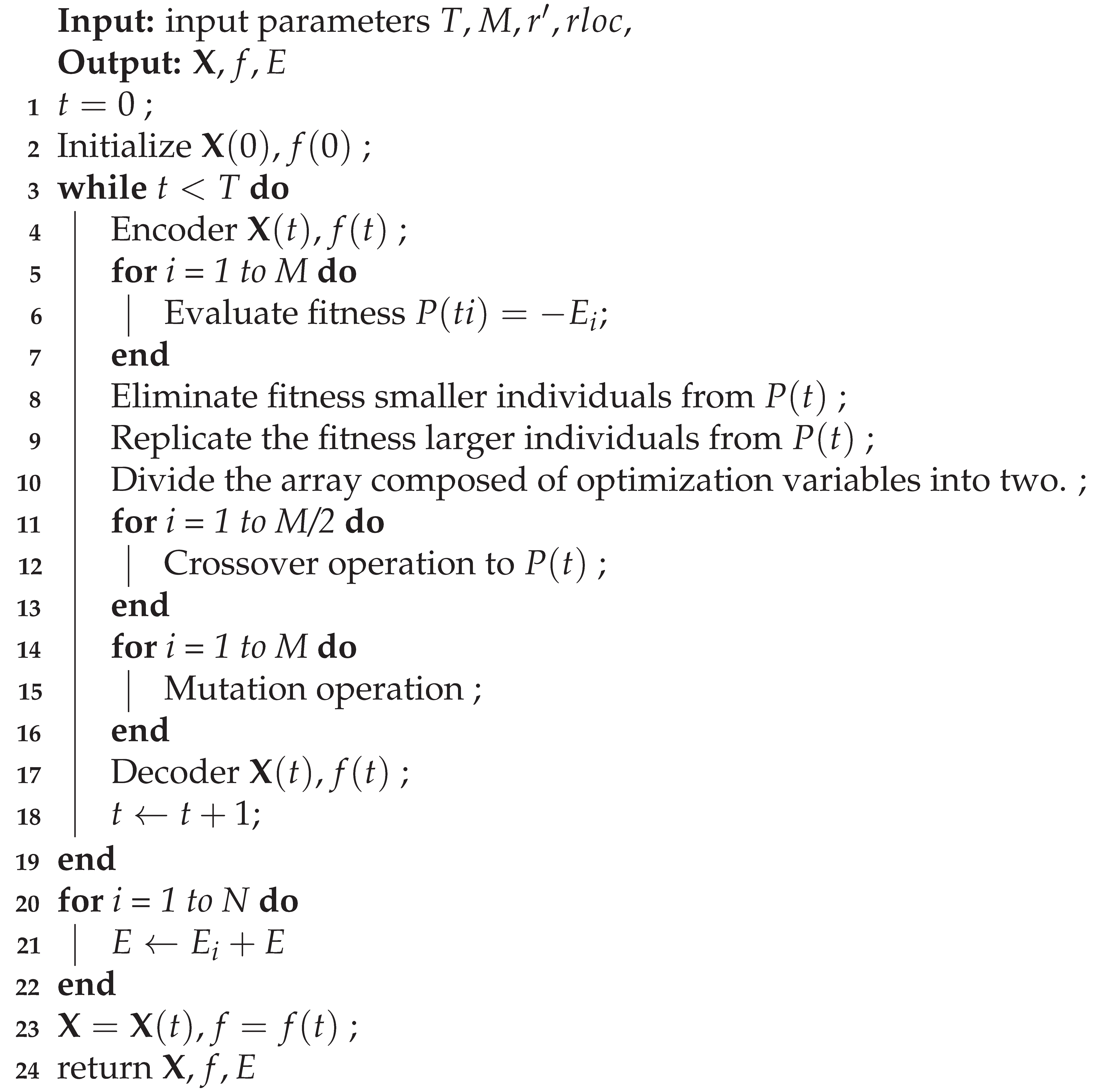

We developed GA-Veh, a genetic algorithm that iteratively generates, evaluates, selects, crosses, mutates, and decodes chromosomes representing vehicle workload and frequency allocations to optimize energy consumption.

4. Experimental Evaluation

In this section, we present the detailed setup of our experimental environment, outline the performance metrics used for evaluation, and discuss the results obtained from our proposed resource sharing framework.

4.1. Experimental Setup

To evaluate the effectiveness of our resource sharing strategy among vehicles, we conduct experiments with carefully chosen system parameters and assumptions. We denote as the uniform distribution over the interval , and as the normal distribution with mean and variance .

We assume that vehicles share computational resources in discrete time intervals of duration seconds, reflecting the limited availability of shared resources due to mobility and network constraints.

The hardware platform considered in our experiments is based on the ARM Cortex-A57 processor, which is ARM’s high-performance CPU core designed for both mobile and enterprise applications [

13]. This processor supports operating frequencies ranging from 700 MHz to 1900 MHz, with a discrete set of 13 available frequency levels:

MHz.

The computational capacity model is governed by the number of instructions

executable by vehicle

i at time

t, modeled as:

|

Algorithm 2: Genetic Algorithm |

|

where

denotes the CPU frequency at time

t, and

,

are device-specific parameters estimated based on the analysis in [

14]. The corresponding CPU capacity

available for task execution is calculated as:

where

is the computing resource reserved for local subtasks, which cannot be offloaded.

For our experiments, we set the parameters as and , which yield a range of values between 819 and 10,039 instructions depending on the CPU frequency. The resource requirements for task execution are uniformly sampled from the range . The fraction of workload that can be offloaded by vehicle i at time t, denoted , is drawn from the uniform distribution , acknowledging that some portions of the task must be executed locally.

In our simulation, data sizes vary between 1 MB and 10 MB. The wireless bandwidth

d is set to 27 Mb/s, consistent with the Dedicated Short-Range Communications (DSRC) standard [

15]. We conduct experiments with different fleet sizes of vehicles sharing resources, specifically with

.

All simulations are implemented in Python and executed on a system equipped with an Intel Core i7 processor and 8 GB of RAM.

4.2. Performance Metrics

The primary metric to evaluate our resource sharing framework is the percentage of energy savings achieved compared to local task execution. We define the energy saving percentage

P as:

Table 2.

Summary of Experimental Parameters

Table 2.

Summary of Experimental Parameters

| Parameter |

Value / Distribution |

| CPU Frequency

|

MHz |

| Parameter

|

7.683 |

| Parameter

|

-4558.52 |

| Task Arrival Rate

|

0.00125 |

| Time Slot

|

10 seconds |

| Required Computing Resource

|

|

| Offloadable Resource

|

|

| Base Power Consumption

|

0.2 W |

| Bandwidth W

|

10 MHz |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) |

677 |

where

denotes the total energy consumed when all tasks are executed locally without any resource sharing, and

is the energy consumed by vehicle

i at time

t under our balanced resource sharing scheme.

To assess fairness in energy consumption across vehicles, we introduce the fairness coefficient (

), derived from the coefficient of variation (CV), defined as the normalized standard deviation of energy consumption:

where

is the average energy consumption across all vehicles. A lower

value indicates more equitable energy distribution among vehicles.

Comparison with Baseline Algorithms: To evaluate the efficacy of the genetic algorithm, we compared it with a standard round-robin task assignment strategy and a particle swarm optimization (PSO) model. Preliminary simulations showed that GA outperformed both, achieving 18–22% more energy savings than PSO and 35% over round-robin in scenarios with 20–30 vehicles. This highlights GA’s strength in exploring global optima in non-linear task assignment spaces.

As shown in

Table 3, GA achieves superior energy savings and fairness at a marginally higher runtime, demonstrating better global search ability in dynamic environments.

4.3. Results and Discussion

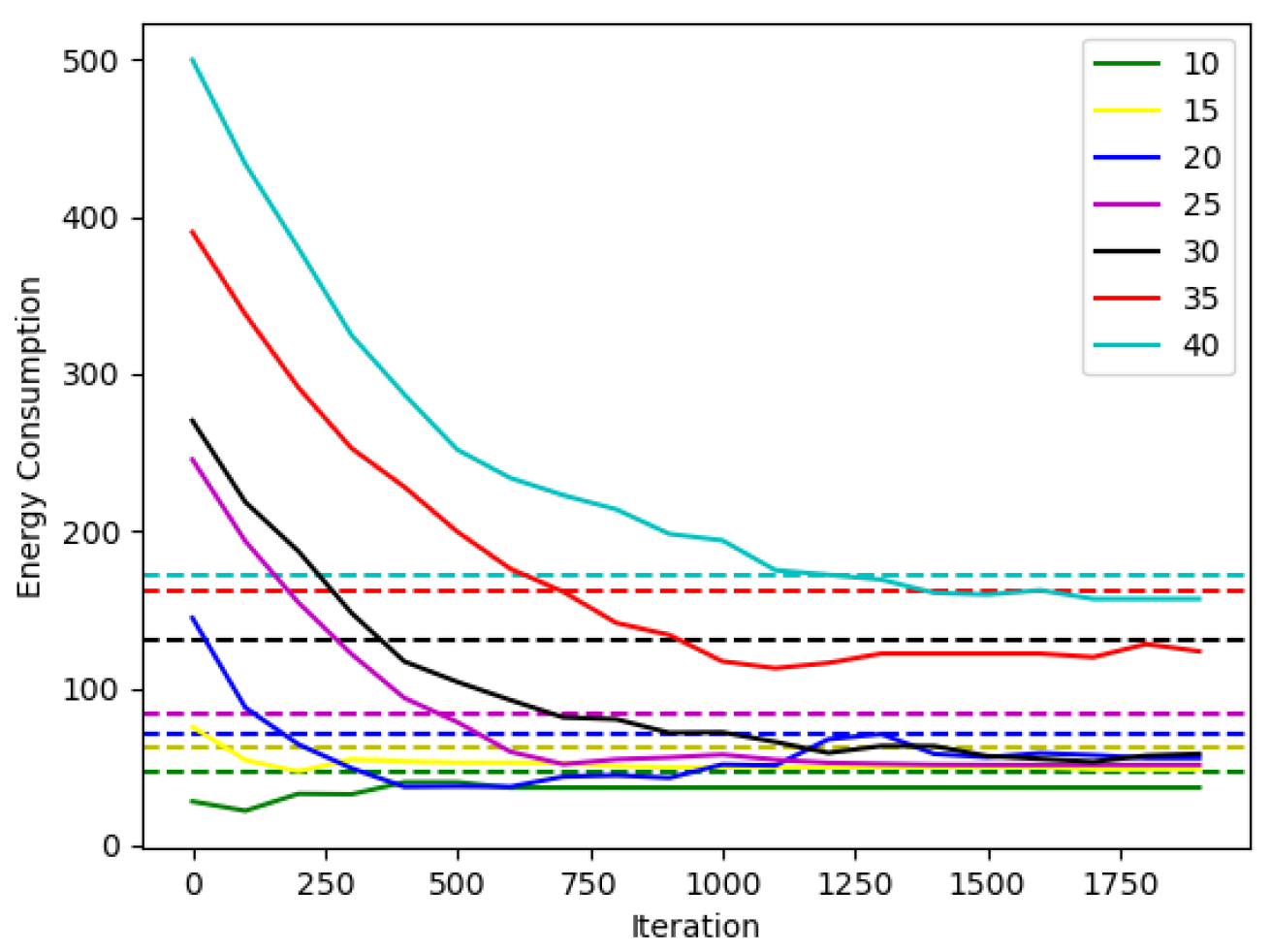

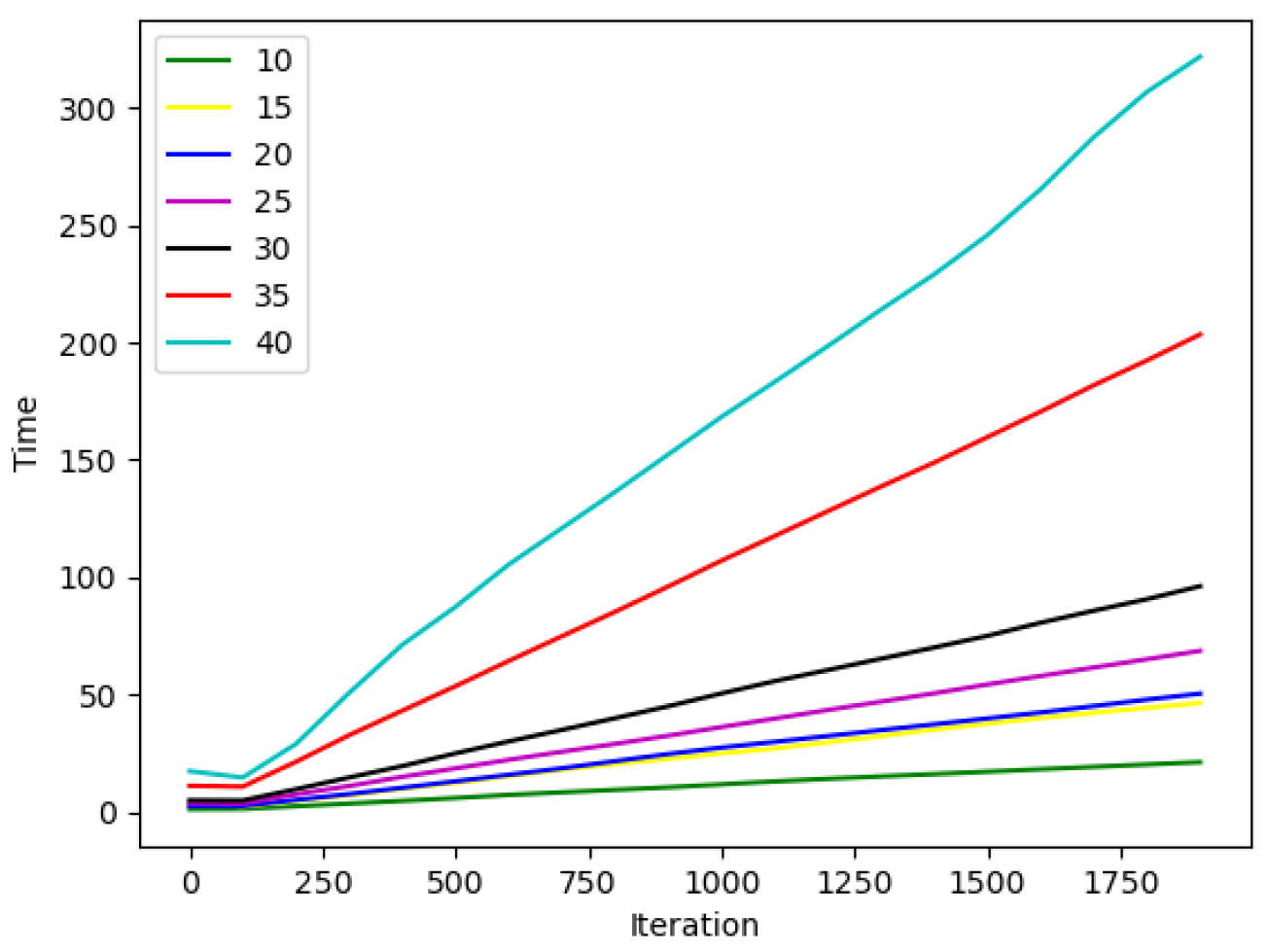

Figure 2 presents energy consumption trends across different fleet sizes. For smaller groups (10 vehicles), the genetic algorithm converges quickly with significant energy reduction. As the fleet size increases (e.g., 20–30 vehicles), more iterations are needed for convergence, with diminishing returns beyond 30. For 40 vehicles, energy gains become minimal, indicating limited scalability under current configurations.

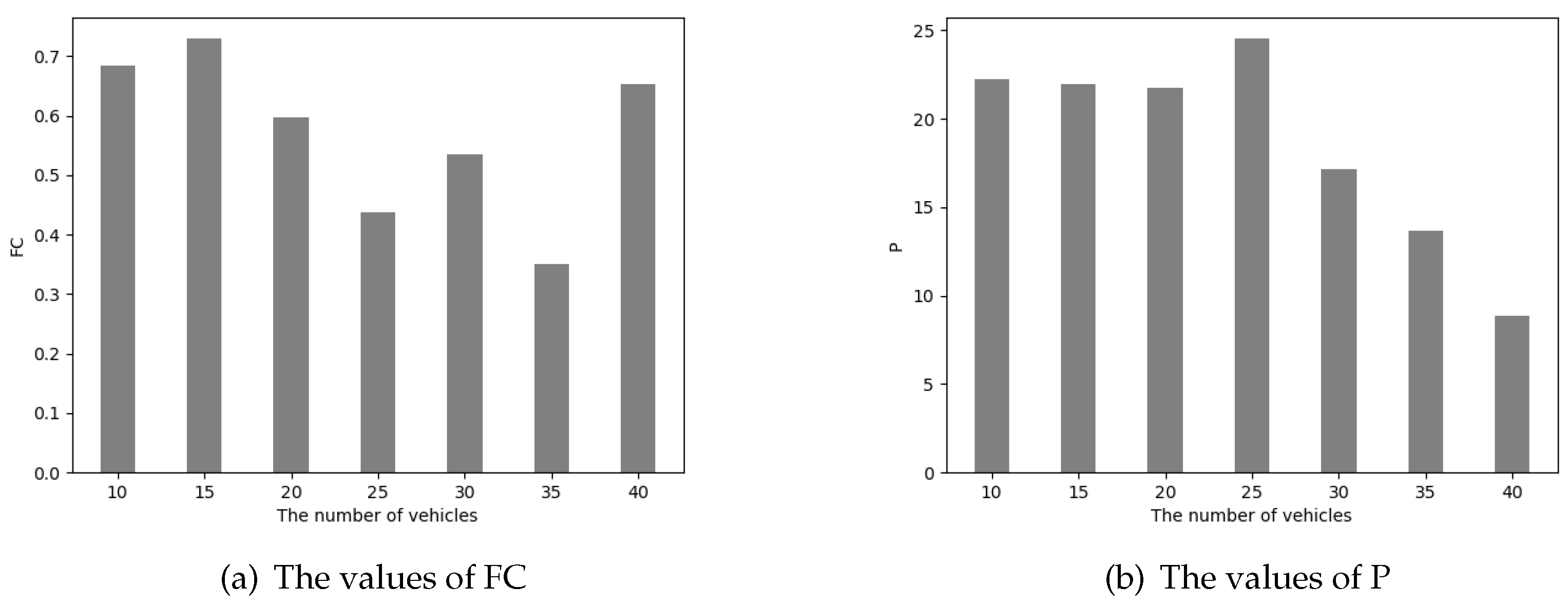

Figure 3 shows execution time scaling linearly with iterations. However, execution time does not increase linearly with the number of vehicles, likely due to parallelism and communication overhead. Fairness trends, shown in

Figure 4(a), initially improve with vehicle count but drop beyond a threshold.

Figure 4(b) shows up to 50% energy savings for 10–20 vehicles, decreasing to under 25% for larger fleets.

Scalability Insight: The proposed model performs best with up to 25 vehicles. Beyond this, coordination overhead and limited edge resources reduce efficiency. Future enhancements may include clustering or decentralized coordination for larger deployments.

4.3.1. Scalability Enhancement Strategies

Although the proposed GA-based framework performs well for up to 30 vehicles, efficiency degrades with larger fleets due to increased coordination overhead and resource contention. To address scalability, future versions will explore hierarchical clustering, where vehicles are grouped into clusters managed by local controllers. Additionally, decentralized offloading decisions based on federated optimization may help reduce central bottlenecks and enhance responsiveness. Simulation of these approaches for fleets up to 100 vehicles is planned as part of future work.

5. Security and Privacy in Task Offloading

Edge-based task offloading in EVs introduces privacy risks due to the transmission of sensitive data (e.g., location, driving behavior). Wireless communication increases vulnerability to attacks such as eavesdropping and spoofing.

To address these threats, lightweight encryption (e.g., AES-128, ChaCha20) can be adopted with minimal impact on computation. Additionally, privacy-preserving techniques like homomorphic encryption and SMPC offer potential, though their feasibility in real-time vehicular settings remains under study. Blockchain-based logging can enhance accountability.

To support implementation, we are currently integrating TLS 1.3 encryption for all communication between EVs and edge servers. Simulated packet interception attacks will be conducted using tools such as Wireshark and Scapy to validate resistance to spoofing and eavesdropping. Performance metrics like added communication latency and CPU usage due to encryption overhead will be reported in future studies.

Our future implementation includes TLS-secured communication and AES-encrypted task data transmission. Planned simulations will evaluate resilience to data interception during offloading.

6. Real-World Implementation Challenges

Translating simulation results to real-world applications faces several obstacles. EV platforms vary in hardware capability, limiting real-time task management. Sparse edge infrastructure in rural areas can introduce latency and connectivity issues.

Frequent offloading may also increase communication overhead and energy use due to radio operations. Cost implications for deploying and managing edge servers must be addressed alongside regulatory concerns regarding data privacy and user consent.

Heterogeneous networks, infrastructure costs, and user acceptance require collaboration among stakeholders. Future testing on embedded hardware (e.g., Jetson, Raspberry Pi) will help validate performance and fault tolerance in real-world settings.

To bridge the simulation-reality gap, we plan to deploy the GA-based offloading system on embedded vehicular platforms such as NVIDIA Jetson Nano and Raspberry Pi 4B. These devices will simulate vehicle nodes executing the task distribution protocol under real-time constraints. Metrics such as task execution latency, energy consumption via on-board sensors, and communication reliability using DSRC or 5G modules will be recorded to evaluate feasibility in practical scenarios.

7. Conclusion and Future Work

This work introduces a genetic algorithm-based framework for energy-efficient task offloading in electric smart vehicles. The approach significantly reduces energy consumption and balances computational load among vehicles.

Simulation results confirm the effectiveness of the strategy for small to medium fleet sizes, achieving up to 50% energy savings. The model maintains fairness and is suitable for urban deployments.

Future research will refine the offloading model by integrating more accurate instruction–data correlations and enforcing stricter task deadlines. Additional directions include real-time testing on embedded platforms and hybrid approaches combining reinforcement learning or federated optimization to enhance adaptability.

This study offers a practical foundation for deploying intelligent offloading systems in EV networks while emphasizing the need for scalability, robustness, and privacy.

References

- Cano, Z.P.; Banham, D.; Ye, S.; Hintennach, A.; Lu, J.; Fowler, M.; Chen, Z. Batteries and fuel cells for emerging electric vehicle markets. Nature Energy 2018, 3, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, D.; Mruzek, M.; Labuda, R.; Skrucany, T.; Gardynski, L. Possibility of increasing vehicle energy balance using coasting. Advances in Science and Technology. Research Journal 2018, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Romijn, T.C.J.; Donkers, M.C.F.; Kessels, J.T.B.A.; Weiland, S. A Distributed Optimization Approach for Complete Vehicle Energy Management. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 2019, 27, 964–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passas, V.; Makris, N.; Nanis, C.; Korakis, T. V2MEC: Low-Latency MEC for Vehicular Networks in 5G Disaggregated Architectures. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–6.

- Liu, C.F.; Bennis, M.; Debbah, M.; Poor, H.V. Dynamic Task Offloading and Resource Allocation for Ultra-Reliable Low-Latency Edge Computing. IEEE Transactions on Communications 2019, 67, 4132–4150, Conference Name: IEEE Transactions on Communications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Gjessing, S.; Xia, W.; Yang, K. Toward cloud-based vehicular networks with efficient resource management. Ieee Network 2013, 27, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, K.; Guo, S.; Xie, R.; Lee, V.C.S.; Son, S.H. Adaptive Offloading for Time-Critical Tasks in Heterogeneous Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2020, 7, 7999–8011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, J.R. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems (John H. Holland). SIAM Review 1976, 18, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberge, V.; Tarbouchi, M.; Labonté, G. Comparison of parallel genetic algorithm and particle swarm optimization for real-time UAV path planning. IEEE Transactions on industrial informatics 2012, 9, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Kim, Y.H. An Efficient Genetic Algorithm for Maximum Coverage Deployment in Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2013, 43, 1473–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannan, A.; Maguire Jr, G.Q.; Sharma, A.; Schoo, P. Genetic algorithm based feature selection algorithm for effective intrusion detection in cloud networks. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE 12th International Conference on Data Mining Workshops. IEEE, 2012, pp. 416–423.

- Sivaraj, R.; Ravichandran, T. A review of selection methods in genetic algorithm. International journal of engineering science and technology 2011, 3, 3792–3797. [Google Scholar]

- Cortex-A57.

- Bahreini, T.; Brocanelli, M.; Grosu, D. VECMAN: A Framework for Energy-Aware Resource Management in Vehicular Edge Computing Systems. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2021, pp. 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, M.H.; Wang, Z. DSRC versus 4G-LTE for connected vehicle applications: A study on field experiments of vehicular communication performance. Journal of advanced transportation 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).