1. Introduction

-

I.

Relevance of the research and key aspects. The primary objective of holding assets in the public sector is to provide various services to the community free of charge. At the same time, public sector entities use certain assets for commercial purposes (Vardiashvili 2019). Therefore, IPSAS 45 considers the receipt of future economic benefits or service potential associated with these assets as the recognition criterion for property, plant, and equipment, emphasising that assets in the public sector do not always generate cash flows. Consequently, valuation methods for cash-generating assets are, in practice, not applicable to them.

At the initial stage (based on the standards issued in 2001), the International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS) were largely based on private sector standards (IAS/IFRS). However, in the subsequent period, the IPSASB (International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board) began improving the standards, aiming to achieve rational convergence with IFRS while better reflecting the specific characteristics of the public sector. To achieve this goal, in 2021 the IPSASB developed and issued for public consultation four major exposure drafts: ED 76, ED 77, ED 78, and ED 79, which addressed:

The establishment of a measurement hierarchy;

Principles for defining fair value; and

The introduction of public sector-specific current value measurement bases, including Current Operational Value.

These projects formed the basis for the following standards:

IPSAS 46 – Measurement;

IPSAS 45 – Property, Plant and Equipment;

IPSAS 43 – Leases, among others.

In addition, amendments were introduced to the Conceptual Framework, focusing on the elimination of unused measurement bases and the incorporation into practice of fair value measurement (Vardiashvili 2024).

IPSAS 46 Measurement provides a new, unified set of guiding principles for the valuation of assets and liabilities. At the same time, by introducing Current Operational Value — a public sector-specific current value — it further develops the general concept of fair value. In doing so, it responds to stakeholder views regarding the introduction of an alternative measurement basis to fair value for assessing the current value of operational assets. The successful implementation of this standard requires an appropriate legislative framework, institutional mechanisms, and readiness of human resources.

Relevance of the research

The relevance of the study is determined by the challenges associated with the practical implementation of IPSAS 46 and the interpretation of new measurement methods — such as Current Operational Value — within the specific context of the public sector.

The aim of the research is to examine, using Georgia as an example, the readiness and attitudes of public sector entities towards IPSAS 46 Measurement, the adoption of which “will contribute to a fair reflection of the value of services, operational capacity, and the financial capacity of assets and liabilities” (IPSAS 46).

The objectives of the study are to:

Assess the legal, institutional, and technical readiness of Georgia’s public sector entities to apply the methods envisaged under IPSAS 46;

Analyse the subjective perceptions and attitudes that determine the feasibility of effective and sustainable implementation of the standard;

Identify the factors that facilitate or hinder the successful implementation of IPSAS 46 in Georgia;

Determine the impact of new measurement models on the quality, transparency, and compliance of financial reporting.

Object of the research. Under the EU–Georgia Association Agreement, Georgia has undertaken the obligation to gradually implement international standards in the field of accounting and financial reporting. An essential part of this process is the implementation of the International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS) in public sector financial reporting, which requires both technical and institutional readiness. The object of this study is the practical application of measurement methods provided by the standards in force in the public sector for non-financial assets.

Subject of the research. The subject of the study is the set of challenges that may accompany the implementation of IPSAS 46.

The research focuses on:

The perception and understanding of the standard by public sector organisations;

Their legal, technical, and human resource readiness for the implementation of IPSAS 46.

2. Results

The present study makes a significant contribution to the discourse on the challenges of adapting national systems during the implementation of International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS) in the public sector.

Based on the study’s findings, it can be argued that the effective implementation of measurement methods for non-financial assets in the public sector requires a comprehensive, systemic approach and cannot be limited solely to isolated legal amendments or modifications to reporting practices.

The study also provides a basis for assessing the current state of IPSAS implementation in Georgia, specifically IPSAS 46 Measurement, and offers valuable insights for regulatory bodies planning the adoption of similar standards in other developing countries. Particular emphasis is placed on analysing the professional experience, education, readiness, attitudes, and perceptions of accounting specialists within the context of IPSAS standards — an area that is relatively underexplored in the existing literature.

3. Methodology

The study is based on a descriptive-evaluative design, aiming to analyse the readiness and attitudes of public sector entities in Georgia in the context of implementing IPSAS 46.

Sampling:

Target group: The study involved representatives of the public sector, including financial managers, accountants, and other administrative staff from government agencies, municipalities, and legal entities under public law (LEPLs).

Sampling method: Purposive sampling was employed, selecting organisations and individuals directly involved in the financial reporting process.

Data collection: The data collection instrument was a thematically structured questionnaire, divided into blocks, hosted on the Google Forms online platform. The questionnaire was distributed electronically to the selected organisations, ensuring broad geographical and sectoral coverage.

Data analysis:

Quantitative analysis was performed using Google Forms’ automatic analysis functions, which provided visualisations in the form of charts, tables, and diagrams;

The results were generalised so that approximately 100 participants were represented, allowing for an exploratory level of interpretation;

Responses were expressed as percentages and analysed to identify potential relationships between variables;

Qualitative data — respondents’ open-ended answers — underwent thematic analysis, revealing key content patterns and trends.

To ensure adherence to ethical principles, all participants were informed of the study’s objectives and the conditions for data confidentiality. Anonymity was maintained at all stages.

Documentary analysis: A wide range of documentary sources was utilised in the study. Using a simple thematic analysis, previous research was examined, including scholarly articles and publications from professional accounting organisations, in order to identify problems and challenges associated with IPSAS implementation.

4. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis

Financial reporting provides a structured overview of an entity’s resources and obligations as at the reporting date, offering users valuable information regarding the entity’s financial position. This is achieved when the information meets the qualitative characteristics defined by the Conceptual Framework for general-purpose financial reporting (Sabauri 2024).

High-quality financial reporting is positively correlated with the allocation of resources (Guangning Liu 2024). The recognition, measurement, and disclosure of information related to accounting objects enable users to understand the current financial position of entities of interest and make informed business decisions (Sabauri, Vardiashvili and Maisuradze 2023).

Measurement, as a method for determining the value of assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity in financial reporting, has a decisive impact on companies’ strategic decisions. Different measurement methods, such as historical cost, replacement cost, current value, and fair value, can result in significant differences in how a company’s financial position is presented in financial statements (Guangning Liu 2024; Maisuradze and Vardiashvili 2016).

Financial statements prepared in accordance with standards should accurately and timely reflect events that occurred during a specific period. This is crucial, as every individual or organisation is interested in assessing the entity in which they plan to invest (Sabauri 2018). Measurement is a complex process that relies on various models and professional judgement, making it often subjective. Consequently, measurement plays a critical role in presenting high-quality financial information. Recognition of elements in financial statements requires the determination of their monetary value, which can only be achieved through the measurement process, necessitating the selection of an appropriate measurement basis and method (Sabauri, Vardiashvili and Maisuradze 2022).

There are not many differences between the measurement bases and methods applied under IPSAS and IFRS; the main distinction lies in the applicability of fair value in the public sector (Vardiashvili 2024).

The valuation of assets and liabilities in public sector financial reporting has always been a highly debated topic, presenting certain challenges and giving rise to dilemmas for both academic research and practitioners (Caruana et al. 2023).

The valuation models for assets and liabilities that an entity should use under IPSAS and IFRS are generally divided into historical cost and current value models. The choice between historical or current value models as a measurement basis significantly affects the content of financial reporting and its perception by users (Vardiashvili 2024; Sabauri and Kvatashidze 2016).

According to the IFRS Conceptual Framework, the bases for measuring current value include: (a) fair value; (b) value in use for assets and fulfilment value for liabilities; and (c) current value.( Sabauri 2018)

Revaluation of assets and liabilities in the public sector, i.e., measurement at current value, should take into account the primary objectives of most public entities and the types of assets and liabilities they hold (Beke-Trivunac and Živkov 2024).

To provide detailed guidance on the revision of measurement requirements and the application of certain methods, IPSAS issued the project ED 90 – The Ripple Effect of IPSAS 46 Measurement in March 2017. The project concluded in May 2023 with the publication of IPSAS 46 Measurement and amendments to Chapter 7 of the Conceptual Framework for General-Purpose Financial Reporting by public sector entities. IPSAS 46 Measurement comes into effect on 1 January 2025, making it timely to examine the impact of its requirements on existing standards (Caruana 2025).

The amendments primarily concern methods of measurement at current value. The newly introduced methods replace previous approaches and include: Current Operational Value for assets, Cost of Fulfillment for liabilities, and Fair Value for both assets and liabilities, instead of market value (Vardiashvili 2024).

Current Operational Value, designed specifically for the public sector, is used to measure assets employed in the provision of services rather than for generating economic benefits or for sale. This amendment aims to better reflect the specific characteristics of the public sector in financial reporting (Beke-Trivunac and Živkov 2024).

Assets carrying the potential to generate benefits, which enable public entities to perform their core functions, generally do not generate cash flows but provide a tangible base for the execution of the main functions of public organisations (Vardiashvili 2018).

If an asset is held on a public entity’s balance sheet for the purpose of service delivery, the use of fair value is generally inappropriate, as it fails to satisfy two key concepts: highest and best use, and the maximisation of market data utilisation. According to the highest and best use principle, property should be used in a way that generates maximum benefit—whether financial, social, or economic.

In the public sector, there are numerous examples of deviations from the highest and best use principle. For instance, a school building located in the city centre could potentially generate higher financial returns if converted into a commercial centre; however, this will not occur because the provision of educational services is a public service that the public organisation, as the owner, is obliged to provide in accordance with its purpose. Although the standard allows for consideration of alternative uses of non-financial assets from a legislative perspective, the highest and best use is ultimately determined from the perspective of market participants, rather than the owning organisation, which may intend to use the asset in its own way (IPSAS 46).

In such situations, it is essential to assess the significance of cash flows generated by the asset. To determine this, an entity may independently develop criteria, in line with the standard’s requirements, enabling the distinction between cash-generating and non-cash-generating assets (Vardiashvili 2024), as this affects the types of assets held by the entity.

Within the framework of IPSAS 46 developed by the International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board, Current Operational Value is considered a measurement basis specifically tailored for the public sector. It better reflects the value of assets that carry service potential and for which no active market exists. Despite the theoretical advantages of this measurement method, existing literature highlights both its benefits (Caruana 2025; Vardiashvili 2025b) and challenges — including its subjective nature, limited information, and practical difficulties (Beke-Trivunac and Živkov 2024; Liu 2024).

In the article D90 – The Ripple Effect of IPSAS 46 Measurement, the author emphasises the significance of Current Operational Value as a new measurement method that differs from fair value and better suits assets without an active market. The article also notes uncertainties regarding the application of this value in specific standards (IPSAS 31, IPSAS 43), raising concerns about the reliability and subjectivity of valuations. In conclusion, the historical cost model remains practically more suitable for the public sector, as the current value model requires subjective assessments, which may compromise transparency and accountability in reporting (Caruana 2025).

IPSAS 46 introduced not only Current Operational Value but also Fair Value, replacing market value, in public sector measurement methods.

Fair Value can be challenging to apply in the public sector for the following reasons:

Many assets are held for current operational use, making the determination of a sale price impractical;

If an asset cannot be sold, the costs of revaluation may outweigh the benefits of updating its measurement; and

Many assets are specialised or restricted, meaning that no market exists from which information can be obtained, complicating the determination of fair value (Maisuradze and Vardiashvili 2023; Jikia 2019).

Changes to commonly applied measurement methods in public sector accounting standards (IPSAS) are reflected not only in IPSAS 46 but also in updates to other standards. The implementation of all these standards forms part of the broader IPSAS adoption process. “The adoption of IPSAS by governments improves both the quality of financial information provided by public sector entities globally and comparability” (IPSASB 2022).

In this context, Polzer et al. note that “the expected benefits of IPSAS adoption for governments include, among other aspects, increased accountability and transparency, improved decision-making processes, and enhanced efficiency” (IPSASB 2022).

Among the advantages of adopting IPSAS is that they provide governments and local public institutions with an economic and financial perspective, ensure the quality and consistency of public financial reporting, reflect the transparency and efficiency of public institutions, promote a performance-oriented culture, enhance the functioning of internal control and transparency in the public sector, and provide more comprehensive and consistent information on expenditures and revenues, facilitating more consistent and comparable financial reporting over time and across entities (Beșteliu 2021).

Beșteliu (2021) further identifies the benefits of IPSAS adoption as “the continuous improvement of the quality of financial reporting by public institutions to provide relevant, reliable information, while ensuring consistency between reporting periods and among public institutions within our country; and the establishment of a comparative reporting framework at the national level for both private and public sector environments.” The author emphasises that “in Romania, we can discuss convergence of national public sector norms with international public sector accounting standards rather than mere harmonisation or compliance.” The conclusion is that “the application of IPSAS standards is considered a true revolution, potentially much more significant than for economic entities, because public institutions are managed in a manner similar to private entities, with recognition of obligations, inheritance, and double-entry accounting” (Beșteliu 2021).

In the article The Magic Shoes of IPSAS: Will They Fit Turkey?, Ristea, Seda Ada, and Christiaens (2018) examine the discrepancies between formal and actual harmonisation of IPSAS in Turkey (2010–2014) using a mixed-methods approach. The authors demonstrate that coercive pressure alone is insufficient for effective implementation and highlight institutional, legal, and cultural obstacles, including state dominance, translation challenges, and a lack of social pressure.

The adoption of IPSAS is progressing globally; however, certain challenges remain, particularly regarding the improvement of accountants’ competencies in the public sector and the establishment of robust institutional structures to support IPSAS-based reporting (UNCTAD 2021).

In relation to the implementation of this standard, attention is focused on the extent to which public sector entities are prepared to use the model effectively. Accordingly, the present study is based on the following primary hypothesis:

H1:

Professional readiness, resource availability, attitude towards development, and perceived need constitute a precondition for the adoption and application of IPSAS 46 within public sector entities in Georgia.

5. Results and Analysis

IPSAS 46 Measurement entered into force on 1 January 2025. Accordingly, this study sought to determine the extent to which Georgia’s public sector is prepared to accommodate the changes introduced by this standard.

As part of the analysis, the first step was to establish whether the requirements of the new standard are reflected in the accounting and reporting guidance documents of Georgia’s central government, autonomous republics, and local self-government budgetary organisations.

Based on official sources published on the website of the Ministry of Finance of Georgia, it was determined that, during the first half of 2025, these changes had not yet been incorporated into the relevant documents.

Target Population and Sample Size

To assess and present evidence on the extent to which the public sector is prepared to adopt new measurement methods, the survey commenced with questions concerning the work experience, educational background, and positions held by public sector employees (

Table 1).

The study involved approximately 1,000 respondents. The target population comprised accountants employed in public sector entities, representatives of academia, and members of professional organisations. Despite representing different areas of professional activity, all participants shared one common characteristic: professional involvement in public sector financial reporting and the process of standards implementation. Consequently, they can be considered competent and informed stakeholders, capable of providing in-depth and accurate evaluations of the core issues addressed in this research.

As shown in

Table 1, the majority of respondents hold advanced academic qualifications: 25% have a bachelor’s degree, while 58% hold a master’s degree. Professional experience levels among the respondents are also notably high. These findings indicate that a significant proportion of those engaged in accounting-related activities already possess specialised expertise and, most likely, the relevant professional competencies. This enhances both the reliability of the survey and the analytical significance of the research findings.

"Accounting education forms the fundamental basis of accounting practice; therefore, it is consistently regarded as part of the effort to bridge the gap between theoretical education and practical application" (United Nations, Review of Practical Implementation of International Standards of Accounting and Reporting in the Private and Public Sectors). It also represents a key factor in assessing the extent to which individuals are prepared for the practical implementation of IPSAS.

Figure 1. Public Sector Readiness for IPSAS Implementation: Level of Knowledge, Training, and Attitudes Towards Adoption

Figure 1. Public Sector Readiness for IPSAS Implementation. The figure combines four categories: Category 1 – respondents’ self-assessment of IPSAS knowledge (6% do not know, 66% average knowledge, 28% good knowledge); Category 2 – experience with IPSAS training (57% have attended, 32% have not attended but willing to participate, 11% have not attended and do not intend to); Category 3 – perception of the necessity of IPSAS implementation (1% not necessary, 18% necessary because required by law, 81% necessary as it improves financial reporting); Category 4 – expectations regarding the timeline for IPSAS adoption (7% within 1–2 years, 35% within 3–4 years, 58% do not know).

In Figure 1, Categories 1 and 2 reflect participation in training and readiness regarding IPSAS. The purpose of the questions was to determine how well-informed and prepared professional accountants are in relation to the International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS). To this end, participants were asked several interrelated questions, including self-assessment of their knowledge and prior experience with relevant training.

Analysis of the responses revealed that, in Georgia, despite the growing strategic importance of IPSAS implementation for improving public financial management, only 28% of accountants in this sector possess a good knowledge of IPSAS. This indicates the need for targeted educational interventions. The strategic communication focus should be on 43% of employees (32% have not undergone training, and 11% have no interest), to enhance their motivation and awareness of the standards’ significance.

Categories 3 and 4 illustrate the perceptions regarding the IPSAS implementation process. These questions highlighted accountants’ views on the adoption of international standards within the Georgian public sector. The results show that, despite a consensus on the necessity of recognition and a generally optimistic attitude towards the implementation process, some respondents remain uncertain about the completion timeline, likely due to challenges, resource constraints, or lack of experience.

Regarding the use of subsequent measurement models for recognized main assets (Figure N1), it is evident that the majority—91%—employ the historical cost model, indicating a conservative practice. This approach is straightforward and does not require frequent revaluations or external assessments. The low utilization of the revaluation model (9%) may suggest a lack of resources, limited methodological or personnel support, or a preference for practical simplicity.

Figure N1. Use of Subsequent Measurement Models for Recognized Main Assets.

Although 91% of respondents indicated using the historical cost model in the previous item, the question regarding the use of the fair value model revealed that 59% reported employing the fair value approach to some extent. This likely applies to specific assets or transactions where fair value is necessary—for instance, assets received through non-exchange transactions or financial instruments.

The next question focused on the valuation method used for assets obtained through non-exchange transactions. Approximately three-quarters of respondents reported valuing these assets at historical cost, even though non-exchange transactions generally exclude any consideration. This may indicate either misinterpretation of the standards by accounting personnel or, again, a lack of resources.

Furthermore, Figure N2 illustrates the readiness of financial departments to value assets at current operational value. According to the responses, 58% believe that non-financial assets should be assessed by licensed valuation experts, while 42% support valuation by the financial department staff.

Figure 2. Responsible Entity for Valuation of Non-Financial Assets – Respondents’ Perspectives.

According to the study results (Diagram №3), 23% of assets in the financial statements are recorded at historical cost. These include assets not subject to depreciation, such as unfinished construction, land, library collections, unfinished intangible assets, inherited assets, and valuables. Meanwhile, 76% of assets are recorded at carrying amount, and only 1% at fair value.

Figure №3. The valuation methods used by respondents for reflecting assets in financial statements are:.

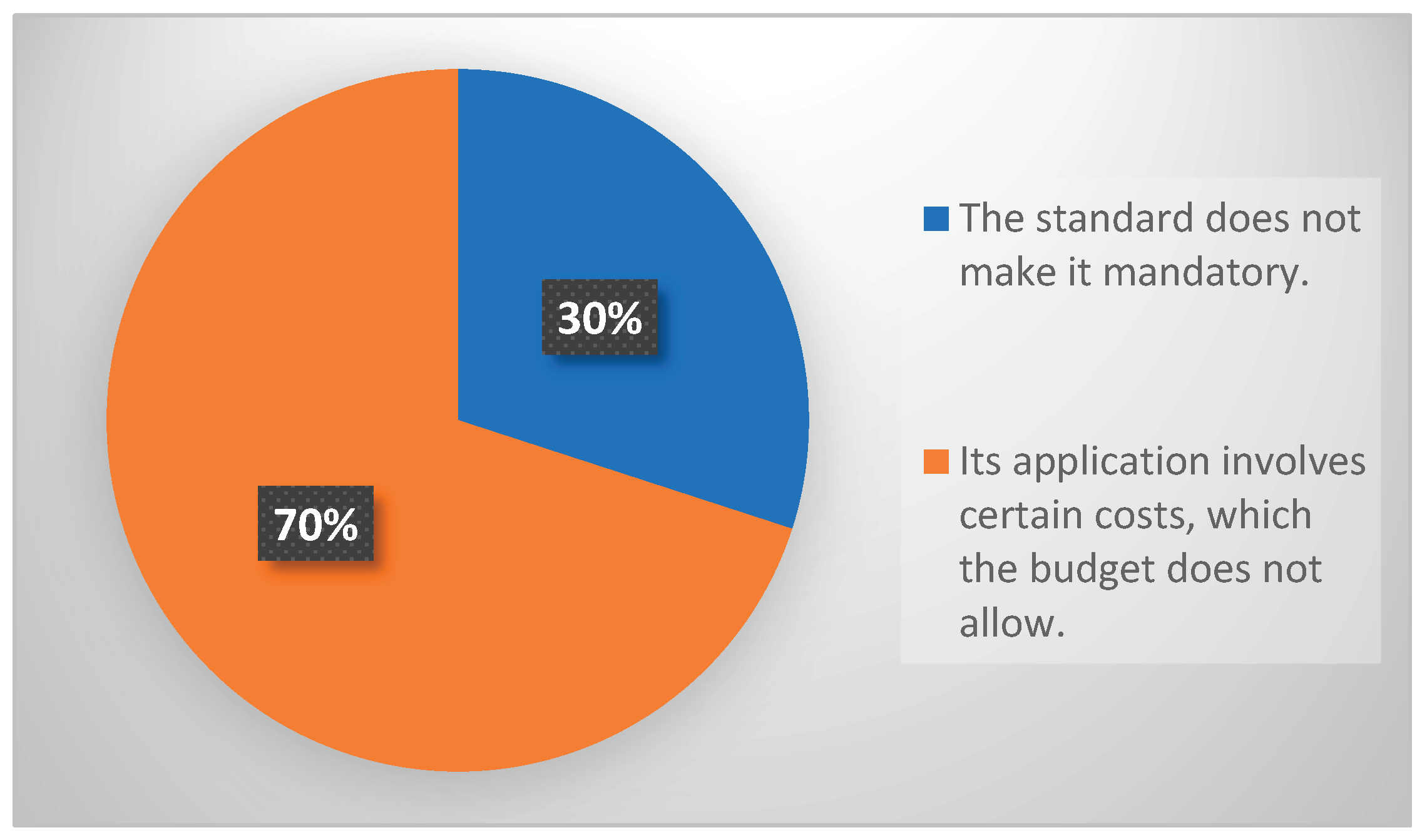

The next question (Diagram №4) addressed why respondents do not use the fair value method for asset valuation. Thirty percent of respondents indicated that the reason is Article 11 of the “Instructions on the Preparation of Financial Accounting and Reporting Based on International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS) for Public Sector Organizations.” According to this article, certain IPSAS requirements — including asset impairment and fair value measurement — are not mandatory until 1 January 2027 (Vardiashvili 2025). Seventy percent of respondents cited limited budgets as the main reason for not using the fair value model, which prevents them from financing the associated costs. These costs notably include hiring external experts, conducting market research, and developing methodological support.

According to the legislation in force in Georgia, the fair value assessment of assets must be carried out by licensed valuation experts, which makes the process particularly challenging for public institutions with limited financial and human resources. As a result, impairment assessments are not systematically conducted, and assets are often recorded at historical cost, even when clear indicators of impairment exist (Vardiashvili 2018).

The Public Sector Accounting Assessment (PULSE) Report of Georgia (May 2025) notes that property, plant, and equipment (PPE), intangible assets, investment properties, and employee benefits generally demonstrate significant conceptual alignment with IPSAS standards, yielding mostly A or B ratings. However, the actual implementation level is assessed as low, primarily receiving C or D ratings, especially for PPE, machinery and equipment, leases, service concession arrangements, and biological assets.

Figure N4.

Use of the Fair Value Model.

Figure N4.

Use of the Fair Value Model.

According to IPSAS 12, inventories should be measured at the lower of cost and net realisable value (or current replacement cost). Nevertheless, due to the small volume of inventories in the public sector, this requirement has limited practical application.

5.1. Effects of Non-Use of Current Value

The financial statements of public sector entities are not publicly accessible, creating limitations in assessing the data obtained from the study. Consequently, it is not possible to accurately evaluate the impact of this decision on the financial indicators of specific institutions.

The reviewed literature indicates that the quality of accounting valuation directly affects the transparency of reporting, which is critical for both investors and regulatory authorities (Liu 2024). When appropriate asset valuation methods are not applied, the transparency and comparability of financial reporting decrease, which often directly influences the decisions of stakeholders.

Selecting an appropriate basis and method for asset valuation significantly determines the quality of financial reporting, comparability among public institutions, and—at the national level—ensures a framework for comparability across both private and public sector environments.

The information contained in accounting records and reports forms a fundamental database for budgeting, execution and monitoring processes. It is critical for the state to use accounting data and integrate it into national, statistical and financial reports, as this information forms the foundation of the budget cycle and reporting.

Special attention should also be given to the effective use of existing financial information in the direct generation of Government Finance Statistics (GFS) reports. The value of non-financial assets that does not reflect the actual condition of the asset in the relevant economic environment directly affects the quality and reliability of financial statements. (Vardiashvili 2022)

6. Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate that global convergence of financial reporting creates several challenges and issues for public sector entities, accountants, auditors, and all users of financial statements.

-

a.

The importance of awareness-raising and training in standards implementation.

A brief analysis of awareness and training related to IPSAS shows that public sector accounting professionals recognize the importance of the standards and are actively interested in acquiring relevant knowledge. However, there is still uncertainty regarding the pace of implementation and expectations. In Georgia, only 28% of public sector accountants are well familiar with IPSAS, indicating the need for targeted educational interventions and strategic communication for the remaining 72%. Effective preparation and engagement of professionals will be one of the main challenges for the successful adoption of IPSAS.

-

b.

Practical challenges of standards translation and their impact on implementation.

One significant challenge in adopting the standards is translation. Difficulties include long English sentences, using the same term for different concepts, and terminology that is difficult to translate. These factors often make certain standard requirements unclear.

-

c.

Budgetary constraints as an institutional obstacle.

The costs associated with current value measurement remain one of the main perceived barriers. Due to limited financial resources in public institutions, hiring licensed valuation experts is often not feasible.

-

d.

The role of government authorities in facilitating the transition to IPSAS.

In many countries, adopting IPSAS under the accrual basis is a voluntary initiative aimed at improving transparency and accountability in public finances (Polzer 2021). In the case of Georgia, the Association Agreement with the European Union obliges the country to gradually align its accounting and financial reporting system with international standards. Nevertheless, the mandatory application of certain requirements, including asset impairment and fair value measurement, is deferred until January 1, 2027.

As Polzer et al. note, formal rules (laws, regulations, directives) and informal rules (customs, conventions, behavioral norms, codes of conduct) act as institutional factors influencing changes in accounting practices (Polzer et al. 2019).

We believe that incorporating the obligation to apply valuation methods, as well as other IPSAS provisions, into local legislation will support and accelerate the use of universally recognized norms in public sector asset valuation. Specifically, amendments should be made to Decree №108 to remove provisions stating that current value measurement is not mandatory.

Top management commitment, often referred to as “tone at the top,” has been recognized as one of the critical factors determining the success of change programs (Isa et al., 2013).

7. Limitations of the Study and Identification of Influencing Factors

The results of this study should be considered in light of certain limitations. Firstly, the conclusions are based solely on data from Georgia and do not include information collected at the individual level, which limits the possibility of conducting formal factor analysis.

Nevertheless, based on thematic grouping, the main factors that may influence the practice of IPSAS valuation were identified:

Resources – including the competence, knowledge, experience, and training of professionals;

Availability of resources – particularly financial barriers when selecting a valuation model;

Readiness for development and recognition of need – including management’s attitude and motivation towards IPSAS.

Additionally, the study has situational limitations: it was conducted at a stage when IPSAS 46 had not yet been translated or reflected in official instructions. Accordingly, the readiness of entities to apply valuation methods was assessed only according to the prevailing circumstances.

Despite its territorial limitations, the findings of the study may be generalised to other developing countries where the implementation of IPSAS is often associated with similar challenges and issues—particularly limited resources, professional difficulties, and management attitudes (Saleh et al. 2021).

8. Recommendations

In response to the growing demand for high-quality and transparent financial reporting in accordance with IPSAS, the following measures are recommended:

- 1.

Enhancing educational interventions to raise awareness

It is essential to plan targeted training that covers both theoretical and practical aspects. Particular attention should be given to professionals who lack in-depth knowledge or have no prior information regarding the standards.

- 2.

Developing a training plan based on needs analysis

A comprehensive training and employment plan should be developed for different professional groups, including:

– Accounting and methodology staff of the Ministry of Finance;

– Accountants of budgetary organisations;

– Internal valuers and external auditors.

- 3.

Increasing motivation among less engaged groups

For those groups (approximately 11%) with neither knowledge nor interest, appropriate information should be provided, and the significance of IPSAS should be communicated through awareness campaigns based on practical examples.

- 4.

Providing strategic support during the implementation process

– Specific timelines should be set for the IPSAS implementation process;

– Guidelines and practical tools should be developed to reduce uncertainty;

– Legislative amendments should be enacted;

– The Ministry of Finance should fund a helpdesk (via telephone or online) providing appropriate accounting expertise.

The helpdesk should be considered a permanent structure within the Ministry.

- 5.

Mobilising financial and technical resources

Effective implementation of the fair value model requires:

– Appropriate training programmes;

– Technological upgrades;

– Recruitment of qualified personnel;

– Funding for external valuations and expert support.

Relevant authorities and partner organisations (e.g., the Ministry of Finance, professional associations) should assume responsibility for assessing the costs of IPSAS implementation and incorporating them into the budget.

- 6.

Integrating IPSAS 46 principles into national standards

To integrate IPSAS 46 principles into local regulatory documents (instructions and others), clear explanations of interpretations and practical examples should be included.

- 7.

Periodic monitoring of data

Regular surveys of this nature are recommended to assess progress and support policy development.

- 8.

Establishing institutional support mechanisms

Clear educational and institutional support structures should be developed to facilitate the practical implementation of IPSAS.

Thus, the study identified the most important factors influencing the adoption of IPSAS 46:

– Relevant local legislation and infrastructure (first level), which drive the costs associated with the initiation of implementation;

– External support and stakeholder engagement (second level), which increase the benefits for participants in the process.

Although training is considered a critical factor, its effectiveness largely depends on the provision of a legislative and infrastructural base, which also affects the optimisation of implementation costs and maximisation of benefits (Cenar & Cioban 2022).

According to World Bank materials, it is crucial that national stakeholders—accountants, auditors, non-governmental organisations, and staff of parliamentary budget offices—have access to training to gain a deep understanding of IPSAS, including its benefits, and to create incentives for reform. Such stakeholders should be able to engage in informed discussions regarding the application and adaptation of principles and standards, as well as the assessment of their implementation effectiveness. See

https://cfrr.worldbank.org/publications/pulsar-drivers-public-sector-accounting-reforms.

References

- Ada, S. S., & Christiaens, J. (2018). ‘The magic shoes of IPSAS: Will they fit Turkey?’, Journal/Source not specified. https://scispace.com/pdf/the-magic-shoes-of-ipsas-will-they-fit-turkey-512hi6wi4a.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB). (2022). Fair value measurement for not-for-profit public sector entities. Available at: https://aasb.gov.au/media/iimfb5au/ps_fvm_nfpps_entities_22-12-22.pdf.

- Beke-Trivunac, J., & Živkov, E. (2024). ‘Measurement of assets and liabilities under the IAS/IPSAS conceptual framework’. Revizor, 27(108), 263–270. [CrossRef]

- Beșteliu, N.-E. (2021). ‘Study on the possibilities of extending the application of international standards for the public sector (IPSAS) in public accounting in Romania and in the Ministry of National Defence’, Bulletin of Carol I National Defence University. [CrossRef]

- Caruana, J. (2021). The proposed IPSAS on measurement for public sector financial reporting – recycling or reiteration? Public Money and Management, 41(3), 184–191. [CrossRef]

- Caruana, J. (2025). D 90 – The ripple effect of IPSAS 46 measurement. Accounting and Management Review | Revista de Contabilidade e Gestão, 29(1), 183–198. [CrossRef]

- Caruana, J., Bisogno, M. and Sicilia, M. (2023). Exploring the measurement dilemma in public sector financial reporting. In: J. Caruana, M. Bisogno and M. Sicilia, eds. Measurement in Public Sector Financial Reporting, Public Service Accounting and Accountability. Emerald, pp.3–16. [CrossRef]

- Cenar, I., & Cioban, E. (2022). ‘Implementation of International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS): Variables and challenges, advantages and disadvantages’, Annals of the University of Petroşani, Economics, 22(1), 55–64.

- Doe-Dartey, R. K., & Valand, J. B. (2024). ‘Investigations of institutional instigations of International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS) adoption in Ghana’, ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/381050293.

- Georgian Ministry of Finance. (2020). Order No. 289 of the Minister of Finance on approval of the instruction for accounting and reporting of depreciation/amortisation by budgetary organisations (in Georgian). Tbilisi.

- Georgian Ministry of Finance. (2023). Public Finance Management Reform Strategy 2023–2026 (in Georgian). Tbilisi.

- IFRS Foundation. (2018). Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting. Available at: https://www.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/publications/pdf-standards/english/2021/issued/part-a/conceptual-framework-for-financial-reporting.pdf.

- Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW). (2023). International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) vs IPSAS in public sector financial reporting. Available at: https://www.icaew.com/technical/public-sector/public-sector-financial-reporting/financial-reporting-insights-listing/ifrs-vs-ipsas-2.

- IPSASB. (2022). Handbook of International Public Sector Accounting Pronouncements (Vol. 1). Available at: https://www.ipsasb.org/publications/2022-handbook-international-public-sector-accounting-pronouncements.

- Isa, C.R., Saleh, Z. & Abu Hasan, H. (2013). Accrual Accounting: Change and Managing Change. IPN Journal of Research and Practice in Public Sector Accounting and Management, 3(01), 101-112. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. (2024). ‘The impact of accounting measurement on the financial reporting’, Advances in Economics Management and Political Sciences, 109(1), 33–39. [CrossRef]

- Jikia, M., 2019. Some aspects of improving the methodology of economic analysis. Ecoforum, 5. ISSN 2344-2174.

- Maisuradze, M., & Vardiashvili, M. (2016). ‘Main aspects of measurement of the fair value of nonfinancial assets’, 15th International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development - Human Resources Development, Varazdin, 9–10 June.

- Maisuradze, M. & Vardiashvili, M., 2023. Applying methods for estimation of the fair value of non-financial assets. Tbilisi: Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University Press; https://tsu.ge/assets/media/files/7/Globalizacia%20ekonomikisa%20da%20biznesshi%20-%208.pdf.

- Polzer, T., Grossi, G., & Reichard, C. (2021). ‘Implementation of the international public sector accounting standards in Europe: Variations on a global theme’, Accounting Forum, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Rompotis, G. G., & Balios, D. (2023). ‘Benefits of IPSAS and their differences from IFRS: A discussion paper’, EuroMed Journal of Business, 20(2). [CrossRef]

- Sabauri, L. and Kvatashidze, N. (2016). Types of financial statements, questions of their submission and comparative analysis according to the IFRS. Proceedings of International Academic Conferences. International Institute of Social and Economic Sciences.

- Sabauri, L. (2018). Lease accounting: specifics. Proceedings of 167th The IIER International Conference, Germany, pp.17–20. Available at: https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=mjrj6wsAAAAJ&citation_for_view=mjrj6wsAAAAJ:zYLM7Y9cAGgC.

- Sabauri, L. (2018). Approval and introduction of the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) in Georgia: Challenges and perspectives. Journal of Accounting & Marketing, 7(2), pp.2–4.

- Sabauri, L. (2024). Internal audit’s role in supporting sustainability reporting. International Journal of Sustainable Development & Planning, 19(5), 1981. [CrossRef]

- Sabauri, L., Vardiashvili, M. and Maisuradze, M. (2022). Methods for measurement of progress of performance obligation under IFRS 15. Ecoforum, 11(3). ISSN 2344-2174.

- Sabauri, L., Vardiashvili, M. and Maisuradze, M. (2023). On recognition of contract asset and contract liability in the financial statements. Ecoforum.

- Sakhapov, B. R. (2024a). ‘Application of fair value for non-financial assets valuation by higher education institutions: Status and prospects’, International Accounting, 27(7), 771–787. [CrossRef]

- Sakhapov, B. R. (2024b). ‘Adaptation of the Russian accounting system for non-financial assets in accordance with the International Public Sector Accounting Standards: A problem analysis. Part 1’, International Accounting, 27(4), 444–464. [CrossRef]

- Saleh, Z., Isa, C. R., & Hasan, H. A. (2021). ‘Accounting standards (IPSAS): Issues and challenges in implementing international public sector’, Journal/Source not specified.

- United Nations; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2022). [Title not available], 23 August. Available at: https://indico.un.org/event/1000454/attachments/6619/17982/2213084E.pdf.

- Vardiashvili, M. (2022). Some issues of accounting for long-term contracts [Electronic resource]. In: Strategic imperatives of modern management: Proceedings of the 6th International Scientific and Practical Conference, 21 October 2022. Kyiv: Vadym Hetman Kyiv National Economic University, pp. 103–105.

- Vardiashvili, M. and Maisuradze, M. (2017). On recognition and measurement of the revenues according to IFRS 15. In: Economy & Business: 16th International Conference, pp.182–189. Available at: http://www.scientific-publications.net.

- Vardiashvili, M. (2018). Theoretical and practical aspects of impairment of non-cash-generating assets in the public sector entities, according to the International Public Sector Accounting Standard (IPSAS) 21. Ecoforum, 7(3), 830.

- Vardiashvili, M. (2019). Some issues of measurement of impairment of non-financial assets in the public sector. Journal of Economics and Management Engineering, 13(5), 521–526.

- Vardiashvili, M. (2024). Impact of IPSAS 43 on lease accounting. IX International Scientific Conference “Challenges of Globalization in Economics and Business,” Proceedings. [online] Available at: https://tsu.ge.

- Vardiashvili, M. (2024). Review of measurement-related changes in International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS). Economics and Business, 16(3), 42–48. [CrossRef]

- Vardiashvili, M. (2025). Measurement of non-financial assets at current operational value. Finance Accounting and Business Analysis, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (n.d.). Public Sector Accounting Assessment (PULSE) Report of Georgia. Available at: https://cfrr.worldbank.org/publications/public-sector-accounting-assessment-pulse-report-georgia.

- Zakiah Saleh, Che Ruhana Isa, & Haslida Abu Hasan. (2021). ‘Issues and Challenges in Implementing International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS)’, IPN Journal of Research and Practice in Public Sector Accounting and Management. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Characteristics of Respondents: Educational Level, Work Experience, and Positions Held — Descriptive Statistics.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Respondents: Educational Level, Work Experience, and Positions Held — Descriptive Statistics.

| Characteristics |

| Level of Education |

Years of Experience |

Current Position |

| Education |

% |

Years of Experience |

% |

Position |

% |

| High School |

1 |

1–5 years |

6 |

Certified Accountant |

65 |

| Vocational College (two-year program) |

12 |

6–10 years |

10 |

Practicing Accountant |

33 |

| Bachelor’s Degree |

25 |

11–15 years |

22 |

Trainee |

2 |

| Master’s Degree |

58 |

16–20 years |

25 |

- |

- |

| Doctoral Studies |

4 |

Over 20 years |

37 |

- |

- |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).