1. Introduction

Driven by the increasing demand for sustainable, biodegradable materials, biopolymer-based composites have been extensively investigated as alternatives to petroleum derived polymers. Various biopolymers have been used as alternatives, focusing on polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), polylactic acid (PLA) and polysaccharide polymers, such as starch, cellulose and chitosan [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Among these, chitosan, a linear polysaccharide derived from chitin, has emerged as a promising candidate due to its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and inherent antimicrobial properties [

5,

6]. However, its practical application is often limited by drawbacks, such as poor mechanical strength, thermal instability, and pronounced hydrophilicity, which compromises its performance in humid environments [

7,

8]. Moreover, considerably high rigidity, along with elevated water vapor and oxygen permeabilities, has been observed in chitosan films prepared by film casting [

4,

9]. Thus, further optimization of both mechanical and barrier properties of these biopolymer membranes is highly required.

Two different approaches are generally used for this purpose; the introduction of compatible nanomaterial inclusions and/or blending with a water-soluble polymer (even synthetic), which do not affect the environmental footprint. To address these limitations, blending chitosan with synthetic polymers, like polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), has gained traction, as PVA enhances mechanical robustness, flexibility, and water resistance while retaining the eco-friendly profile of the composite material. The use of these blends is not only focused on packaging applications but also on biomedical applications, such as wound healing, controlled drug delivery and others [

10,

11,

12]. Nevertheless, since optimal interfacial compatibility between chitosan and PVA remains debatable and depends on parameters such as molecular weight of PVA and chitosan’s degree of deacetylation, it has become a necessity to develop novel strategies to further improve the blend material’s overall properties [

13,

14,

15].

The addition of nanocellulose, either as nanocrystalline cellulose (CNC) or nano-lignocellulose (NLC), is used as reinforcing material in blend systems due to its large surface area per mass unit that allows the formation of extensive hydrogen bonds with hydrophilic polymeric matrices. Notably, nanocellulose enhances the interfacial stress transfer of PVA [

16], elasticity, biocompatibility and gas barrier properties in both PVA [

17,

18,

19] and chitosan composites [

20,

21]. These studies have primarily focused on the incorporation of plant-derived nanocellulose into selected PVA/chitosan blend ratios, with their effects on material properties for packaging applications being examined. PVA was also utilized as the primary matrix, with chitosan being incorporated at varying concentrations (e.g., 10% wt. [

22,

23], 25% wt. [

24], 30% wt. [

25], and 5–20% wt. [

26]), while nanocellulose was added at 1% or 3% wt. However, the utilization of chitosan as the primary matrix, along with critical aspects such as gas permeability measurements (CO₂, O₂, and N₂) and mechanical performance, parameters crucial for packaging applications, has not been systematically explored. In a related study by Solikhin et al. [

27], the addition of 15% wt. chitosan and varying cellulose CNC loadings to PVA was reported to yield improved miscibility, and enhancements in mechanical performance were observed with the incorporation of minimal CNC amounts (0.5%).

While considerable attention has been directed toward chitosan/PVA composites reinforced with nanocellulose for packaging applications, prior studies have largely adopted fixed blend ratios or a single type of cellulosic reinforcement. In such studies, either the chitosan/PVA ratio or the nanocellulose content was held constant, restricting the analysis of compositional variations on overall performance. Additionally, the scope of characterization has typically been narrowed, with mechanical properties examined only sporadically and gas permeability, a critical parameter for packaging applications, remaining unaddressed. To date, no study has systematically explored the combined impact of modifying both the chitosan/PVA matrix composition and the type/loading of nanocellulosic reinforcements on a comprehensive set of functional properties and the possible selective effect of each inclusion on the properties of PVA-rich or chitosan-rich blends. By addressing these limitations, the current study introduces a novel approach by integrating two structurally distinct nanocelluloses (nanocrystalline cellulose, CNC and nano-lignocellulose, NLC) into chitosan/PVA matrices with systematically varied ratios. A thorough assessment of gas permeability behavior (CO₂, O₂, N₂), mechanical performance, and blend miscibility is conducted, elucidating structure-property relationships that advance the development of biopolymer nanocomposites for sustainable packaging solutions. This multi-parametric investigation not only bridges existing knowledge gaps but also establishes a methodological framework for tailoring material performance through synergistic adjustments in polymer composition and nanoscale reinforcement strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Chitosan (medium molecular weight, CAS Number: 9012-76-4) glacial acetic acid (min 99.8%, CAS Number: 64-19-7) and Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) (Mw of 89−98 kDa with 99+% hydrolyzed, CAS Number: 9002-89-5) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Aqueous 11.5-12.5 wt% CNC suspension (CAS Number: 9004-34-6) was purchased from the University of Maine (Orono, Maine, USA). Nano-lignocellulose (NLC) was produced and kindly provided by CERTH (Thessaloniki, Greece). Specifically, hardwood biomass underwent thermal treatment at 190

oC for 90 min, and was subsequently milled/grinded in 500 mL stainless steel bowls using a laboratory planetary ball mill (Pulverisette 5 Planetary Mill, premium line, Fritsch GmbH, Idar-Oberstein, Germany), modifying an established protocol for producing various grades of nanocellulose [

28]. The pretreated suspension was placed in the milling bowls together stainless steel balls of 15 mm and 3 mm diameter, maintaining a respective mass ratio of 0.74 g g

-1. The total ball-to-material (biomass) mass ratio was set to 5.6 g g

-1. Milling was carried out at rotation speed of 300 rpm for a total 8 hr, using 1 min on/2 min off cycles prevent overheating, with reversed rotation applied in each other cycle. Finally, ultrapure water was obtained by a Milli-Q RG apparatus water purification unit.

2.2. Sample Preparation

Chitosan-Cellulose Composites

About 1 wt.% chitosan powder was dissolved in 1% v/v glacial acetic acid aqueous solution under mechanical stirring at room temperature for 3 hr. The final solution was allowed to rest overnight until the insoluble moieties precipitated and then the supernatant clear pale-yellow solution was collected. About 20ml aqueous suspension containing different nanocellulose concentrations (0, 1, 5, 10 wt.%) of CNC or NLC, was mixed with the chitosan solution. The chitosan/nanocellulose mixtures were homogenized under vigorous mechanical stirring for 2hr at room temperature, before being sonicated for 10 minutes at 45W. The final homogenized mixtures in the form of stable suspensions obtained were cast on glass petri dishes and dried for 1 week at room temperature without further treatment before characterization.

Chitosan-PVA-Cellulose Composites

Aqueous solutions of 4 wt.% PVA were prepared by dissolving the polymer in triple distilled water at 85°C under (magnetic) stirring for 1 hour. After stirring, the transparent PVA solution was let to room temperature to cool down. Several mixtures of chitosan/PVA blends at weight ratios of 100/0, 75-25, 50-50, 25-75 and 0/100 were prepared, with the processes of adding cellulosic suspensions and film casting, being the same as described above.

2.3. Analytical Techniques

2.3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was employed to evaluate the morphological characteristics (including size and shape) of cellulosic material and its (homogeneous) distribution within chitosan and chitosan/PVA blend matrices. To identify structural variations resulting from increased filler content, as well as potential defects or agglomerates, film samples were cryogenically fractured using liquid nitrogen. Imaging was performed with a Zeiss SUPRA 35VP SEM system at an accelerating voltage of 2-5 kV, optimized for individual sample stability.

2.3.2. Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR)

ATR-FTIR spectra of solid samples were acquired using a Bruker Alpha-II Diamond ATR spectrometer, covering the wavenumber range of 400–4000 cm⁻¹. Spectra were recorded by co-adding 24 scans at a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹, with a minimum of five replicate measurements averaged for statistical reliability.

2.3.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

X-ray diffraction was used to identify the crystalline phase and detect changes in chitosan/PVA blends before and after adding various loadings of nanocellulose materials. XRD measurements were carried out with a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer equipped by a Cu lamp (λCuKa =1.54046 Å) at a scanning rate 0.5°/min over a range 5°–30° (2θ).

2.3.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements were performed on a Q100 system (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) equipped with a liquid nitrogen cooling accessory. To investigate the melting behavior of PVA in each chitosan/PVA blend and in their nanocomposites, each sample (approximately 6-8 mg) was heated from room temperature to 240 °C at a rate of 10 °C min⁻¹ under a nitrogen flow of 50 mL min⁻¹. Data were collected from the first heating cycle to reflect the actual state of the prepared composites. The Crystallinity Index (Cr.I %) of PVA was determined from the endothermic melt peak using:

Where

is the measured heat fusion,

is the standard heat fusion for 100% crystalline PVA (138.6 J g

-1) [

29], and φ is the weight fraction of both the added chitosan and fillers.

2.3.5. Gas Permeability Measurements

Single-gas permeation was evaluated using the Wicke-Kallenbach method. A circular membrane (effective area: 6.97 cm²) was installed in a custom permeation cell, with the retentate and permeate chambers sealed by Viton O-rings and held under vacuum clamp. The cell temperature was maintained at 30 °C via two coil heaters (BL Sistemi) and a thermocouple (RS Components) controlled by a dedicated temperature regulator. Gas flow rates on both sides were set with two mass flow controllers (Aera FC7700C) at atmospheric pressure. Helium served as the sweep gas at 20 cm³ min⁻¹. Permeate compositions were determined on a Shimadzu gas chromatograph (GC-2014) fitted with a thermal conductivity detector and Porapak Q column for CO₂ analysis, while N₂ and O₂ were measured using a quadrupole mass spectrometer with a secondary electron multiplier. The O₂ signal at m/z=32 was calibrated against a known O₂ standards.

2.3.6. Mechanical Characterization

A hydraulic mechanical testing system (MTS R58 Mini Bionix) was employed for the tensile tests of both, neat blend and nanocomposite materials. The MTS system was equipped with a load cell of 25 kN. Tensile properties of all membranes were determined according to modified ASTM D882 [

30], while the crosshead moving speed was set to 3 mm min-

1.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Chitosan/PVA Ratio on the Blends’ Properties

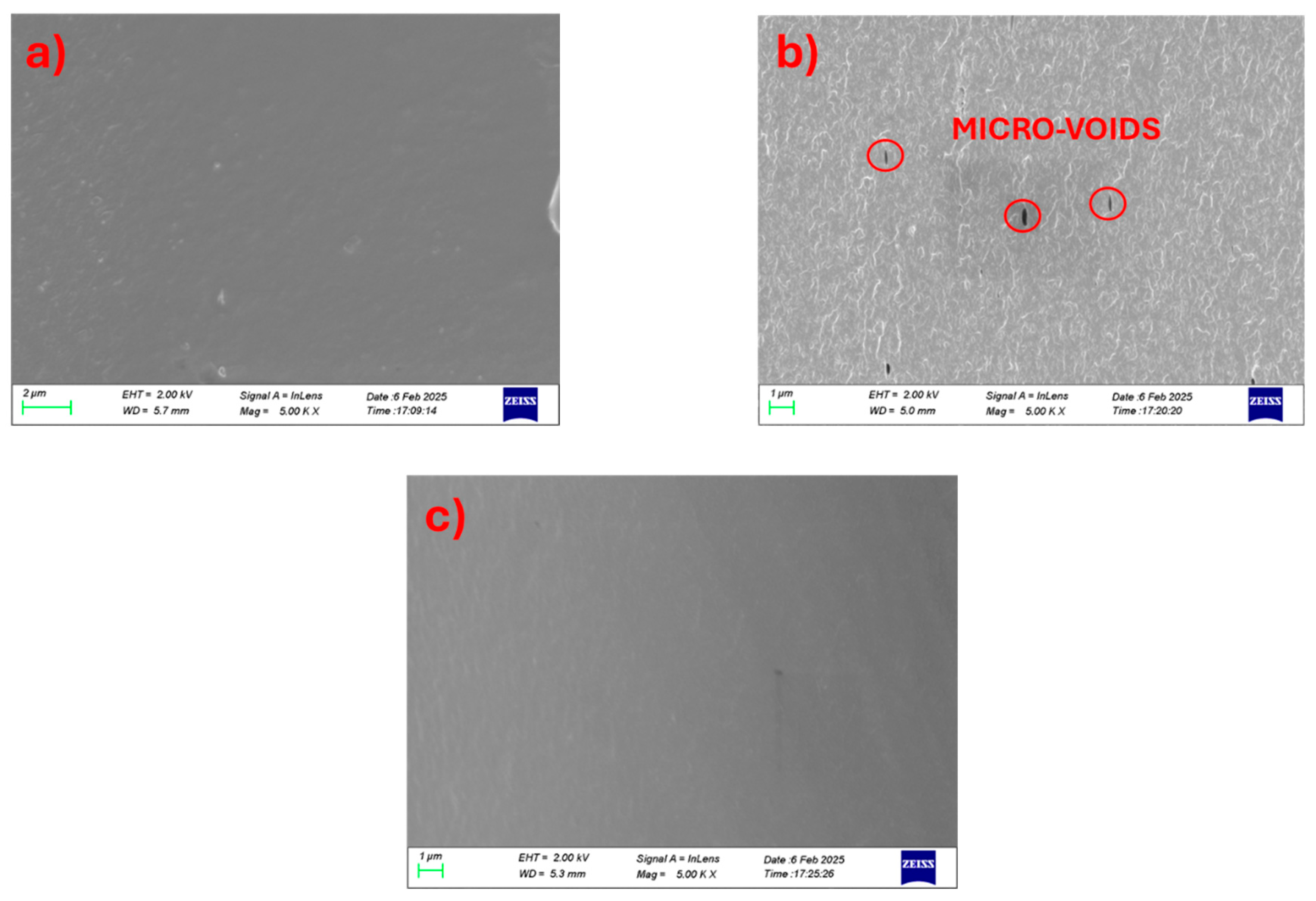

The miscibility of the chitosan/PVA blend was observed to be significantly influenced by the relative proportions of the two polymers, as evidenced by SEM analysis of cryo-fractured cross-sectional morphologies. In the 25-75 chitosan/PVA formulation (

Figure 1a), a uniform and continuous structure was noted, signifying effective compatibility and homogeneous distribution of chitosan within the PVA matrix. By contrast, the 50-50 blend (

Figure 1b) displayed a markedly rougher surface morphology characterized by prominent micro-voids, indicative of phase separation and weak interfacial adhesion between the polymer phases at this composition [

13]. In the 75-25 chitosan/PVA blend (

Figure 1c), a smooth and continuous morphology was again observed, suggesting enhanced miscibility when chitosan predominates in the matrix. Moreover, according to Flory-Huggins theory, symmetric blending ratios may be favorable to intramolecular interactions within each polymer chains, reducing the blend miscibility. These findings imply that intermediate ratios may induce partial immiscibility, potentially due to disruptions in hydrogen bonding equilibrium or reduced molecular entanglement. Chain entanglements act as physical crosslinks that contribute to the mechanical integrity and phase stability of polymer blends. A lower degree of entanglement between polymer chains can weaken interfacial adhesion and promote phase separation.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was utilized to investigate the thermal transitions of chitosan/PVA blends and evaluate their miscibility by monitoring changes in glass transition temperature (T

g) and melting point (T

m). While identification of PVA’s glass transition is highly influenced by the residual water content, the molecular weight and sample pretreatment (e.g., drying), in the present study T

g is well defined and found ~45

oC, while chitosan shows a glass transition at ~90

oC. It should be noted, however, that chitosan’s glass transition is a subject of controversy, with the source of extraction or the method followed strongly influencing it [

31].

As illustrated in

Figure 2a, neat chitosan and PVA were found to display distinct T

g and T

m values, respectively. In blended samples, the detection of a single or dual T

g is a key indicator of polymer compatibility. For the 25-75 chitosan/PVA ratio, a single broadened T

g was detected, indicative of miscibility and the development of a single-phase region characterized by overlapping polymer segment dynamics. Conversely, the 75-25 and 50-50 blends exhibited two distinct T

g values, signifying phase separation and the coexistence of immiscible domains [

13,

14,

32]. Furthermore, a gradual decrease in T

m with higher PVA content was noted, reflecting structural reorganization within PVA's crystalline regions [

33].

The relationship between miscibility and mechanical performance was further investigated through elongation at break values (

Figure 2c), as evidenced by the corresponding stress-strain curves (

Figure S1). An almost steady increase in elongation was observed with rising PVA content, peaking at 100% PVA. This behavior reflects the flexibility of PVA and its capacity to improve the ductility of the blend system. Interestingly, the lowest elongation values were recorded for the 50-50 composition, aligning with DSC (

Figure 2a) and SEM (

Figure 2b) findings that identified phase separation at this blend ratio [

33]. The diminished elongation at this intermediate ratio was attributed to weak interfacial adhesion and inefficient stress transfer between the polymer phases, characteristic of immiscible systems.

Finally, ATR-FTIR and XRD were also used to examine the behavior of the prepared blends related to the mixing ratio (

Figure 2c and d, respectively). Due to similar spectral characteristics in both PVA and chitosan FTIR spectra (1700-800 cm

-1), few peaks are discrete, especially those of protonated chitosan (protonated amine), NH

3+ str. vibration at 1545 cm

-1 being notably shifted to 1556cm

-1 in the case of 25-75 blend, indicating probable interaction between chitosan and PVA, which is strongly depended on composition. However, the PVA characteristic peaks of O-C-C str. (1141 cm

-1) and C-OH str. (1088 cm

-1) vibrations remained unaffected. The characteristic XRD peak of chitosan at approximately 12° (12.7°), which is attributed to regions of partial crystalline organization due to intra- and/or intermolecular hydrogen bonding (between NH

3+ and –OH groups) [

34], exhibits notable variations in intensity or even in its detection depending on the composition of the chitosan/PVA blend. The contribution of the well-defined crystalline structure of PVA is observed through the diffraction peak of the (101) plane at 19.7°. In the 75-25 chitosan/PVA blend, the intensity of the chitosan-associated peak at ~12° is higher than that of neat chitosan, suggesting that the addition of a small amount of PVA promotes intermolecular interactions between chitosan and PVA chains. These interactions, mainly hydrogen bonds between hydroxyl and amino groups, can restrict chain mobility and lead to a higher degree of local ordering within the chitosan phase. In contrast, in the 50-50 and 25-75 compositions, this peak is completely absent. This can be attributed to two concurrent mechanisms: on one hand, the increasing PVA content promotes intermolecular interactions that disrupt the structural organization of chitosan, leading to the loss of the characteristic peak, while on the other hand, the reduced chitosan content may not allow a sufficiently distinct contribution to be detected in the diffraction pattern.

These findings confirm that morphological observations, supported by DSC, mechanical property tests, FTIR, and XRD, can act as a reliable indicator of blend miscibility, confirming the immiscibility of 50-50 blend ratio, while 75-25 ratio shows an intermediate miscibility profile.

3.2. Effect of Cellulose Type/Loading on Chitosan/PVA Blends’ Properties

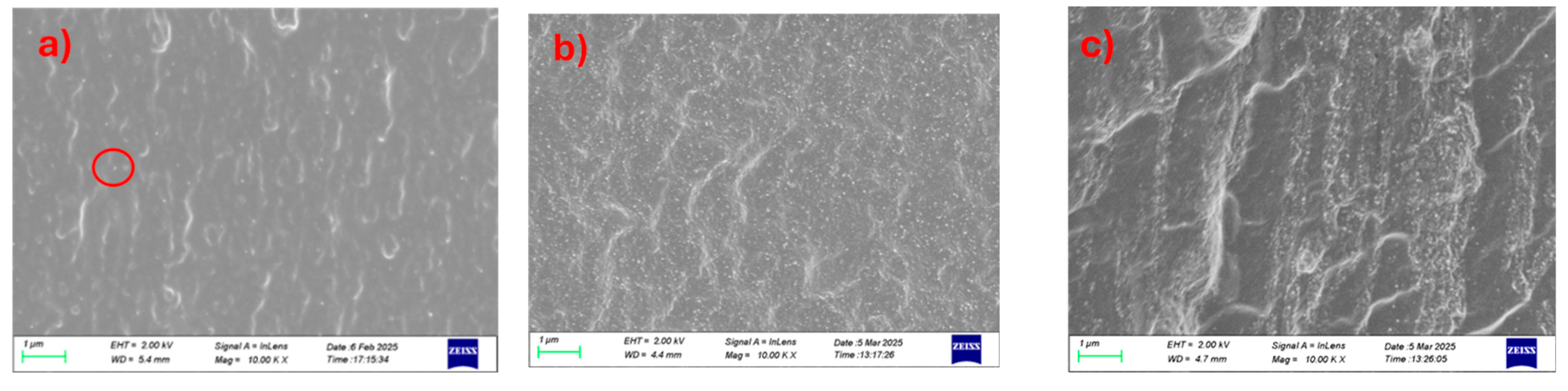

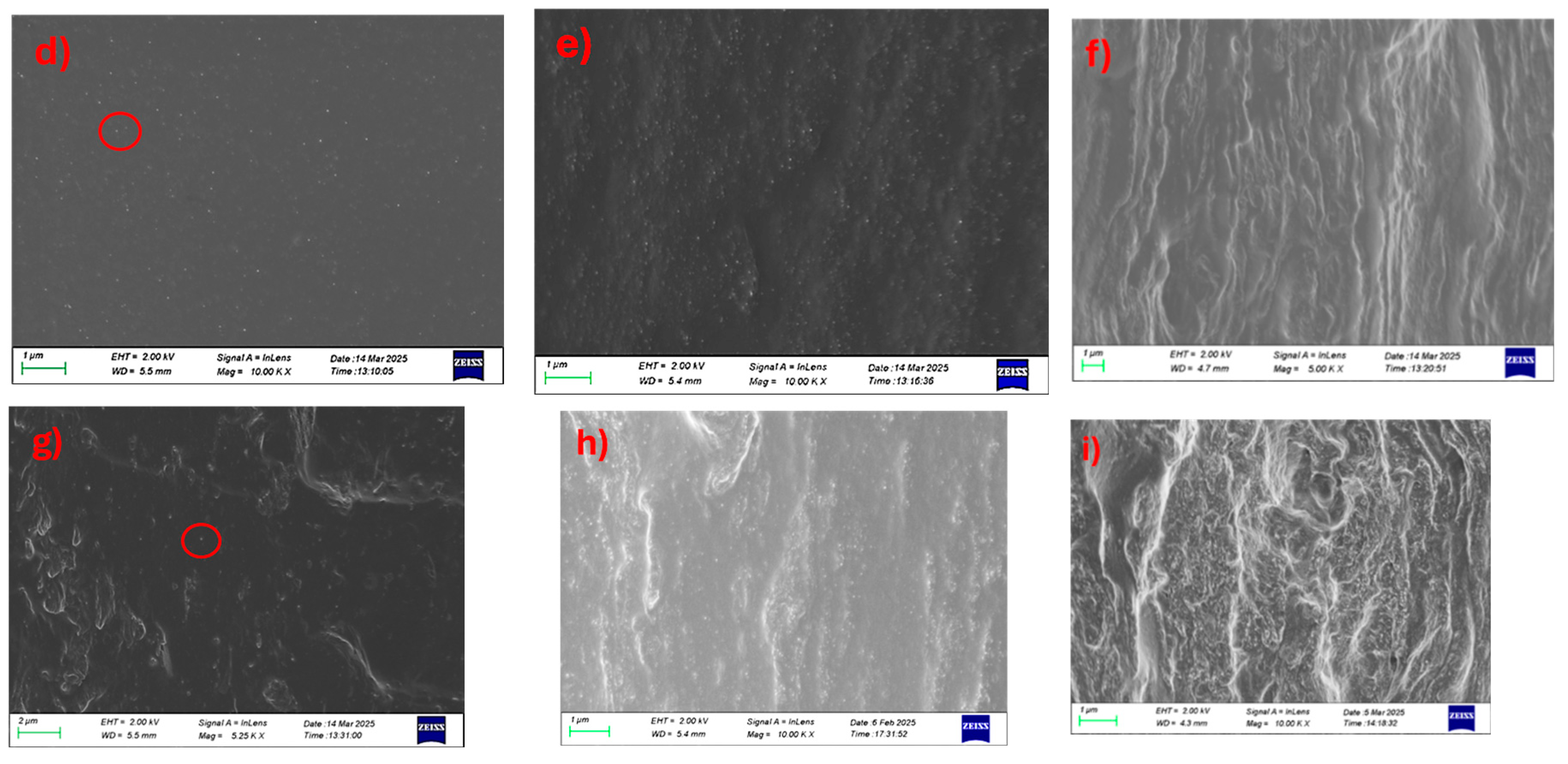

3.2.1. Microscopic Properties

Morphological characterization

The cryo-cut SEM images reveal the morphological evolution and dispersion behavior of CNC within chitosan/PVA matrices at different blend ratios and CNC loadings. The needle-shape structures of CNC have mean width of 40±10 nm and characteristic low length (350±100 nm) giving an aspect ratio of around 10 [

16]. In the 25-75 chitosan/PVA composites (

Figure 3a–c), CNC dispersion appears relatively homogeneous at 1 and 5% loading (a and b), with minimal agglomeration and a smooth matrix. As the CNC content increases to 10% (c), the surface roughness becomes more pronounced, and visible CNC-rich domains emerge, indicating agglomeration and decreased dispersion uniformity. For the 50-50 blends (

Figure 3d–f), the 1% CNC-loaded sample (

Figure 3d) exhibits a similarly smooth morphology with good CNC integration, while the 5% loading is giving a moderate behavior. 10% CNC-loaded sample (

Figure 3f) displays increased microstructural heterogeneity and CNC clustering, suggesting a critical threshold beyond which dispersion is compromised. In the 75-25 chitosan/PVA composites (

Figure 3g–i), even the 1% CNC sample (g) shows signs of CNC aggregation, and these features become more evident in the 5% and 10% (h and i), with clear phase separation and agglomerate formation dominating the fractured surface. A general trend observed across all blend ratios is that CNC dispersion deteriorates with increasing nanofiller content, while higher chitosan content also appears to correlate with reduced CNC dispersion quality (

Figure S2). This suggests that PVA-rich matrices may provide a more favorable environment for CNC stabilization and uniform distribution, likely due to better compatibility and hydrogen bonding interactions between CNC and PVA.

In contrast to the CNC-based composites, the SEM images of chitosan/PVA membranes incorporated with long fibrous NLC, do not exhibit distinct dispersion features within the cross-sectional area. This discrepancy is primarily attributed to the morphological characteristics of NLC, which consists of high aspect ratio fibers typically several microns in length and approximately 50 nm in diameter, as shown in our previous work [

16]. During membrane formation, these elongated fibers tend to be settled not in a well-defined orientation, thereby being beneath the cryo-fractured surface. As a result, the distribution and orientation of NLC within the matrix cannot be reliably assessed through visual inspection of cryo-cut cross sections (

Figure S3), similarly to PVA and chitosan composites (

Figure S4). Consequently, alternative characterization techniques may be required to evaluate the dispersion state and structural integration of NLC within the composite membranes

. An example of well-dispersed inclusions in the scale of microns though, can be found in optical images of

Figure S5, in which CNC composites (a) show great transparency, while NLC is well-dispersed up to 5% loading in each case (b, c).

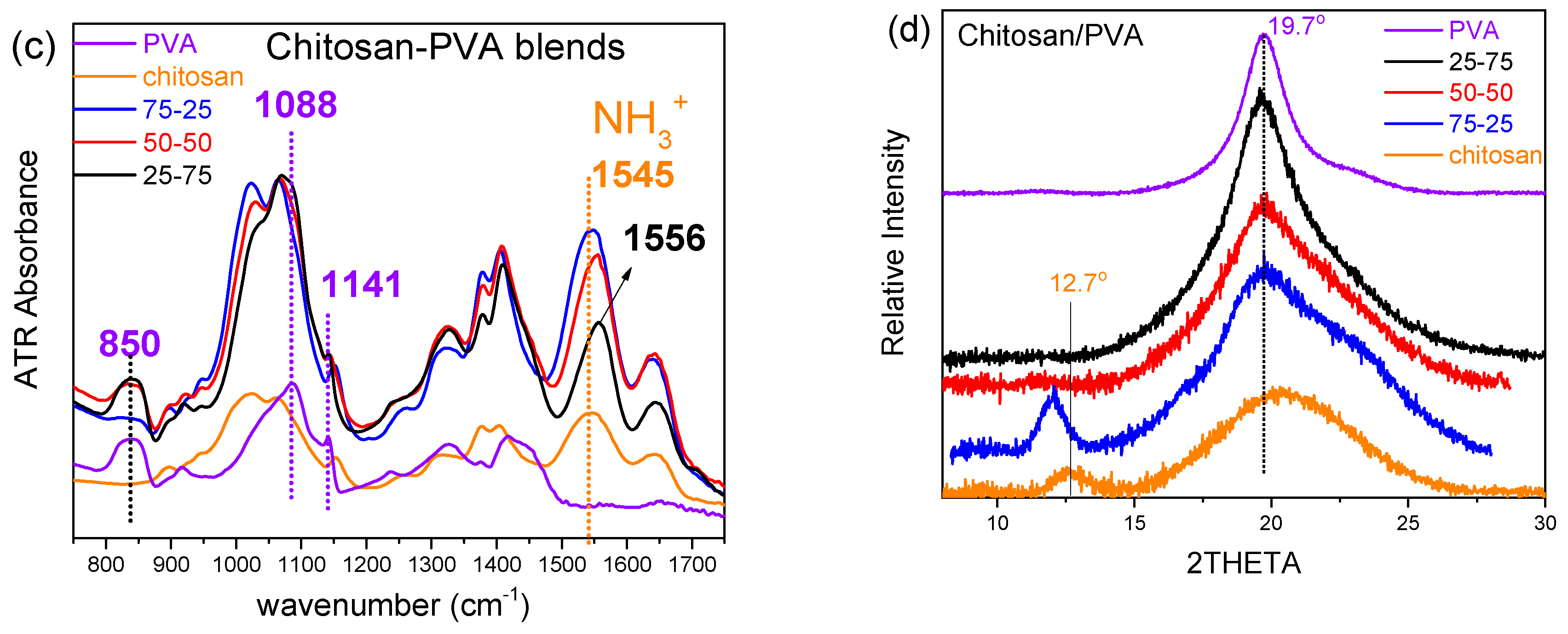

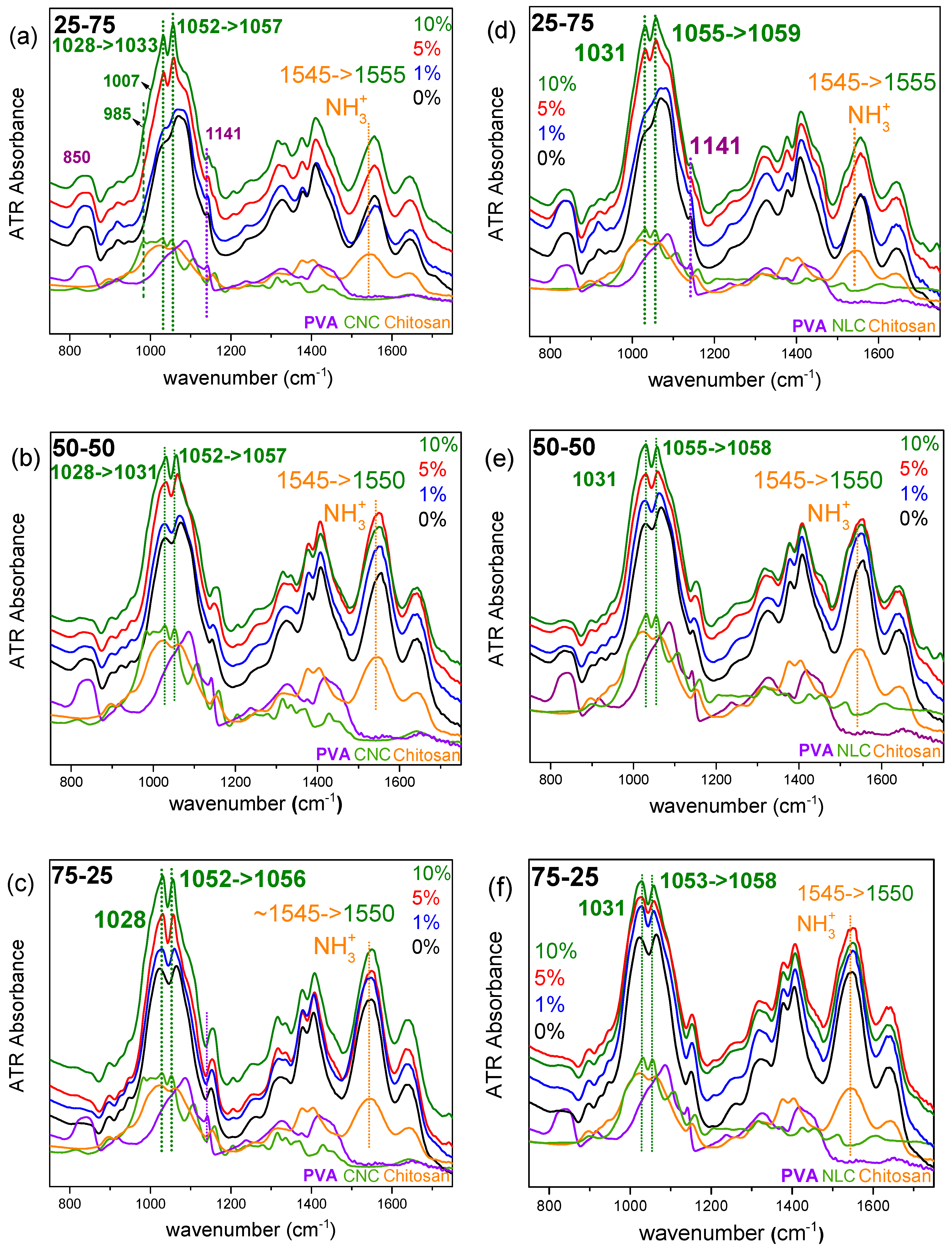

Structure at Molecular Level (ATR-FTIR)

FTIR spectroscopy is a straight-forward technique for studying molecular interactions and compatibility in chitosan/PVA/cellulose nanocomposites, as it directly probes the vibrational modes associated with functional groups responsible for hydrogen bonding. Additionally, spectral analysis can highlight changes in polymer backbone conformation and crystallinity induced by nanocellulose incorporation [

16]. Thus, ATR-FTIR offers a rapid, non-destructive approach to link the effect of cellulose type/loading from molecular to macroscopic, such as mechanical and gas barrier properties.

As discussed earlier in

Figure 2c, there are several peaks in the 1700-800 cm

-1 spectral area of chitosan and PVA, which overlap, while only a few are distinct, with PVA’s CH

2 bending vibration at 840 cm

-1 and chitosan’s NH

3+ str. vibration at 1545 cm

-1 being characteristic. In

Figure 4a-c, ATR spectra of CNC composites of the various chitosan/PVA ratio blends are represented, in which the initial frequency of chitosan’s NH

3+ vibration, is shifted to higher frequency on each blend by CNC addition. Commonly, peaks observed between 1150-950 cm⁻¹ are attributed to C-O stretching vibrations, with shifts in these peaks indicating alternations in the attached hydroxyl group, such as hydrogen bonding, etc. Cellulose, similarly to chitosan and PVA, displays strong peaks in this region due to its extensive structure containing abundant C-O groups.

In a detailed spectroscopic study under controlled temperature and humidity conditions, Maréchal and Chanzy attributed many of these bands to C-O vibrations of the primary alcohol groups (C6H

2–O6H at ~1000, 1015, and 1035 cm⁻¹) and the two secondary alcohols (specifically C3–O3H at ~1060 cm⁻¹ and C2–O2H at ~1110 cm⁻¹) within each glucopyranose unit. The three distinct peaks associated with the primary alcohols correspond to different conformations, determined by the orientation of the C6H

2–O6H group relative to the C5–C6 bond, with the ~1035 cm⁻¹ peak being dominant for the crystalline allomorph I

β [

36].

The vibrational energy of O–H groups, as well as adjacent C–O bonds, is significantly affected by the formation of intra- and intermolecular hydrogen bonds. Variations in the strength of these bonds, due to physical or chemical modifications, can cause peak shifts for both the O–H and adjacent C–O stretching vibrations, typically on the order of ~10 cm⁻¹ [

37]. It has already been discussed [

36] that strengthening hydrogen bonding leads to a decrease in the O–H vibrational frequency, while it has the opposite effect on the associated C–O vibrations.

Indeed, in all CNC composite systems (

Figure 4a-c), the characteristic C–O stretching vibrations of cellulose at 1052 cm⁻¹ (as well as the one at 1028 cm⁻¹ in the 25-75 blend) are observed at higher frequencies within the composite membranes (1033 and 1057 cm⁻¹, respectively). Conversely, the O–H stretching vibrations at 3288 cm⁻¹ (

Figure S7.a) shift to lower frequencies, enhancing the hypothesis of new hydrogen-bond formation between cellulose and the polymeric matrix, as also discussed in previous works [

16,

17,

38]. This observed shift indicates that both primary and secondary alcohol groups of cellulose are involved in forming hydrogen bonds with the polymer matrix. These interactions may also lead to conformational changes in the cellulose polymer chain, which could explain the marked reduction in intensity of the cellulose-associated bands at 985 and 1007 cm⁻¹ in the composite spectra (indicative peaks are highlighted in

Figure 4a).

Regarding the cellulose structure in the corresponding NLC-containing systems (

Figure 4.d–f), a similar discussion can be made as in the case of CNC. The contribution of peak intensity related to different conformations of primary and secondary alcohols appears to differ between NLC and CNC. Additionally, the frequencies of the characteristic C–O stretching vibrations of primary and secondary alcohols in the NLC spectrum show slight differences compared to CNC (1031 and 1055 cm⁻¹). Within the composites, shifts are observed only for the secondary alcohol vibration (from 1055 to 1059 cm⁻¹), suggesting that alterations occur mainly in these groups. It should be noted that in the high-frequency spectral window, due to spectral complexity in the region, potential shifts of the O–H stretching vibrations are not clearly discernible (

Figure S7.b).

According to the above, two observations warrant further investigation. First, in the chitosan/nanocellulose composites (

Figure S6), the imprint of cellulosic inclusion is not distinct in the spectrum of the respective composites. Chitosan and cellulose, both being polysaccharides with similar 1-4 linked glycosidic structures, show similar spectral contributions especially in the 1200-800 cm⁻¹ spectral window, with amorphous chitosan exhibiting broader peaks. As a result, any discrete cellulose peaks become spectrally buried under the strong chitosan absorptions, rendering them invisible in the composite spectrum particularly considering the relatively low loading ratios of cellulose material (less than 10% and as low as 1%). Second, chitosan chains form an extensive intra- and inter-molecular hydrogen bond network (involving NH₃⁺ and C-OH groups), which competes with potential cellulose-chitosan interactions.

The limited (to non-observed, in the case of CNC) spectral shift or intensity of the protonated amine str. vibration at 1545 cm

-1 (

Figure S6), probably highlights that chitosan-cellulose interactions are not significantly important. Apart from the changes corresponding to those of PVA composites in the C–O vibrations of cellulose, the simultaneous shift of the vibration of the protonated amino group (at any case of ternary systems) can account for the enhanced interaction of chitosan with PVA. The already known changes caused by the presence of cellulose in the PVA –OH environment likely allow oxygen atoms to act as hydrogen bond acceptors, with the protonated amino group of chitosan acting as the donor.

Summarizing these findings, in the ternary chitosan/PVA/nanocellulose composites, two distinct interactions were identified by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. First, in chitosan-cellulose binary blends, the spectra remained essentially unchanged relative to neat chitosan, indicating that the chitosan-chitosan interactions dominate over the chitosan-cellulose ones. This is further confirmed in the hybrid composites by the absence of any appreciable shift in the protonated-amine deformation band at ~1550 cm⁻¹ upon cellulose addition, signifying that the intrinsic chitosan network is more affected by PVA blending ratio. Second, cellulose-PVA interactions were evidenced by consistent shifts of the C-O stretching vibrations of cellulose (originally at ~1030 and ~1050 cm⁻¹ shifted by ~4 cm-1) in both binary PVA-cellulose and ternary systems. Thus, while cellulose remains spectrally absent within the chitosan domains, its hydroxyl groups continue to engage PVA chains via hydrogen bonding, enhancing the affinity of chitosan with PVA, improving miscibility at any blending ratio.

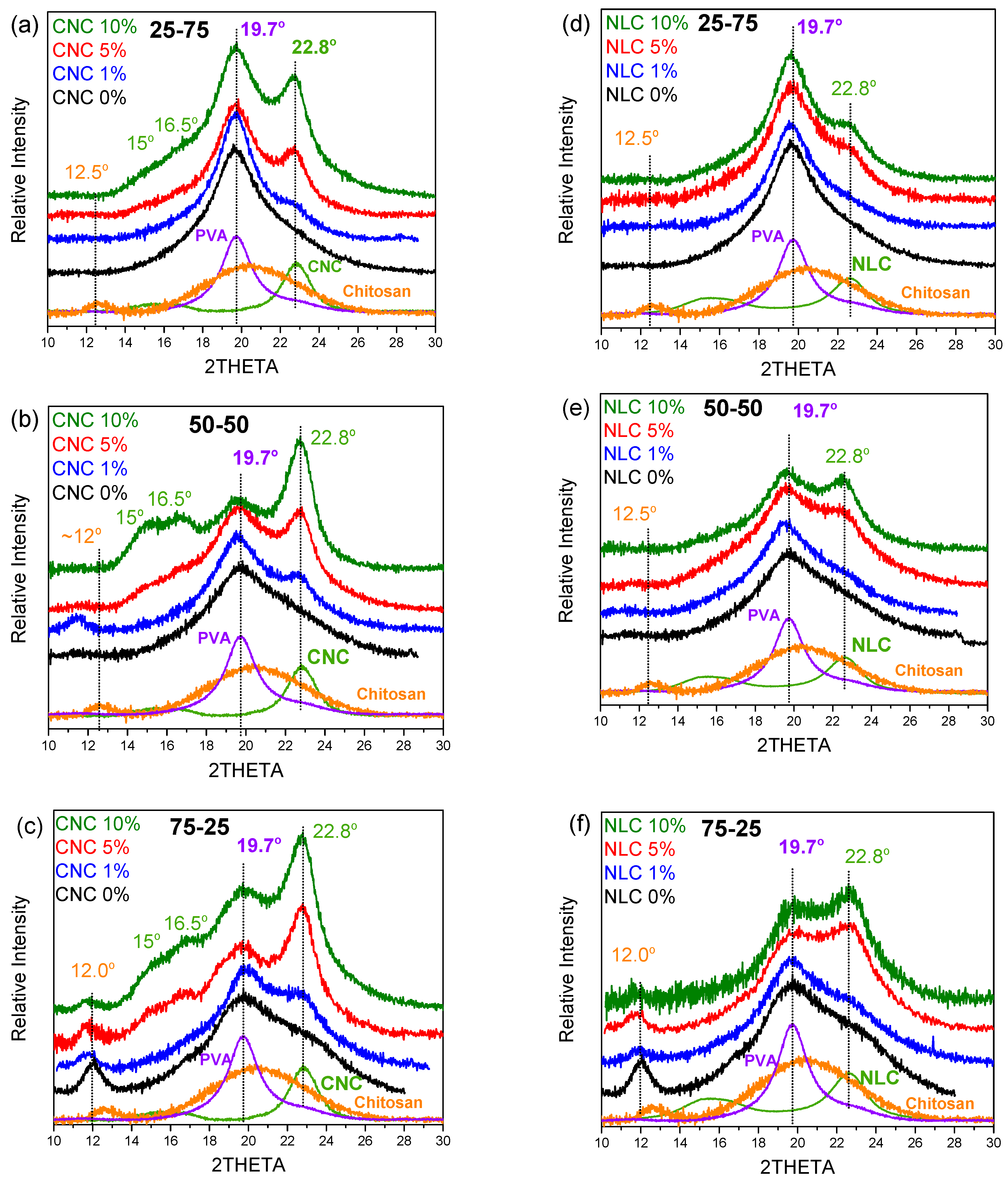

Study of the Effect in Crystal Structure

Chitosan is a polysaccharide whose native crystalline polymorphs arise from ordered hydrogen-bond networks between adjacent glucosamine chains. According to [

39], four distinct chitosan conformations have been identified: one native crystal form and three acid-salt derivatives, all adopting variants of the extended two-fold helix. However, commercial medium molecular weight chitosan (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich, 75–85 % deacetylated) is typically isolated in a largely amorphous state due to its variable degree of deacetylation, chain length heterogeneity, and residual content. Consequently, its X-ray diffraction pattern is dominated by a broad amorphous halo centered around 20

o, reflecting the lack of long-range order. Nevertheless, upon drying or mild annealing, intermolecular hydrogen bonds are reorganized to produce a partially ordered polymorph, which manifests as a weak diffraction peak at approximately 12

o. This feature is attributed to the regular spacing of chitosan chains bridged by interchain hydrogen bonds and bound water molecules and serves as a spectroscopic indicator of formed “crystalline” domains within an otherwise amorphous matrix [

40].

Figure 5a shows the X-Ray diffraction graphs of both initial cellulosic materials, chitosan/PVA matrix and relevant blend/x% nanocellulose composite series. Reference nanocellulose materials (CNC and NLC), possess a characteristic sharp peak at 22.7

o (200) and a doublet of peaks at ~15

o (1

0) and ~16.5

o (110), assigned to the cellulose I

β allomorph [

41].

As previously discussed, in the binary systems, the primary diffraction peak of PVA at 19.7° remains unaffected, while chitosan contributes both to the amorphous phase, evidenced by a broad peak at around 20° and the characteristic peak at ~12°, which is associated with regions of partial crystalline organization. Upon incorporation of CNC (

Figure 5.a–c), the sharp diffraction peak of cellulose at 22.8

o emerges, with its intensity increasing monotonically from 1% to 10% loading, while similar increment is observed at the other CNC peaks too. In contrast, the NLC composites (

Figure 5.d–f) display lower contribution of cellulose (22.8°) within the broad blend’s diffraction profile, even at 10 wt % loading. This sparse NLC diffraction arises from its lower intrinsic crystallinity and from the micrometer-length fibers’ tendency to lie in different order than CNC, to the film plane, thereby reducing the population of lattice planes favorably oriented for effective diffraction. Consequently, despite equivalent mass fractions, CNC is far more “traceable” than NLC, highlighting the influence of filler crystallinity, size, and orientation on the detectability of nanofillers in polymer composites.

In any case, no differences in peak position or other diffraction profile arises, indicating that the crystalline structure of chitosan/PVA blend is largely maintained after the incorporation of either CNC or NLC. As the applied conditions were mild and only the minimum, sufficient to ensure solubility and film formation, by employing only mild acid concentration and casting at room temperature to dissolve chitosan and form films without inducing thermal crystallization, each component shows its own crystal structure contribution in the blend graphs, suggesting that no crystallization of chitosan or other changes achieved in any crystal structure. The fact that no shifts of chitosan, PVA or cellulose contribution is observed, indicates that the incorporation of both nanocelluloses does not affect the structural uniformity of the polymer blend matrix but rather improves molecular ordering in the amorphous regions.

Finally, crystallinity index calculations of PVA contribution within the composite, become challenging and inaccurate due to overlapping peaks and baseline complexity within the area of interest. In contrast, DSC, where the PVA melting endotherm appears as a distinct peak, offers a more reliable and precise means of quantifying crystalline content in these composites.

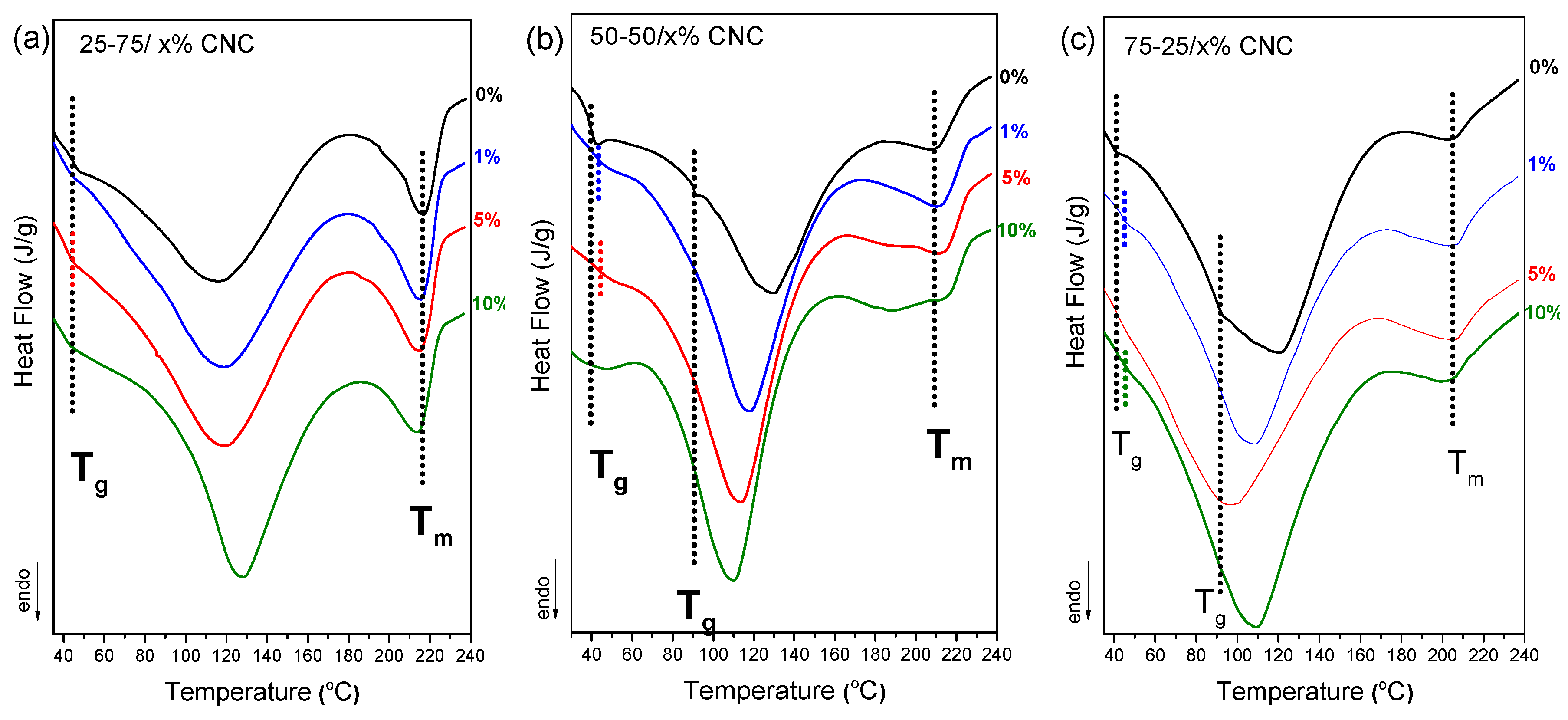

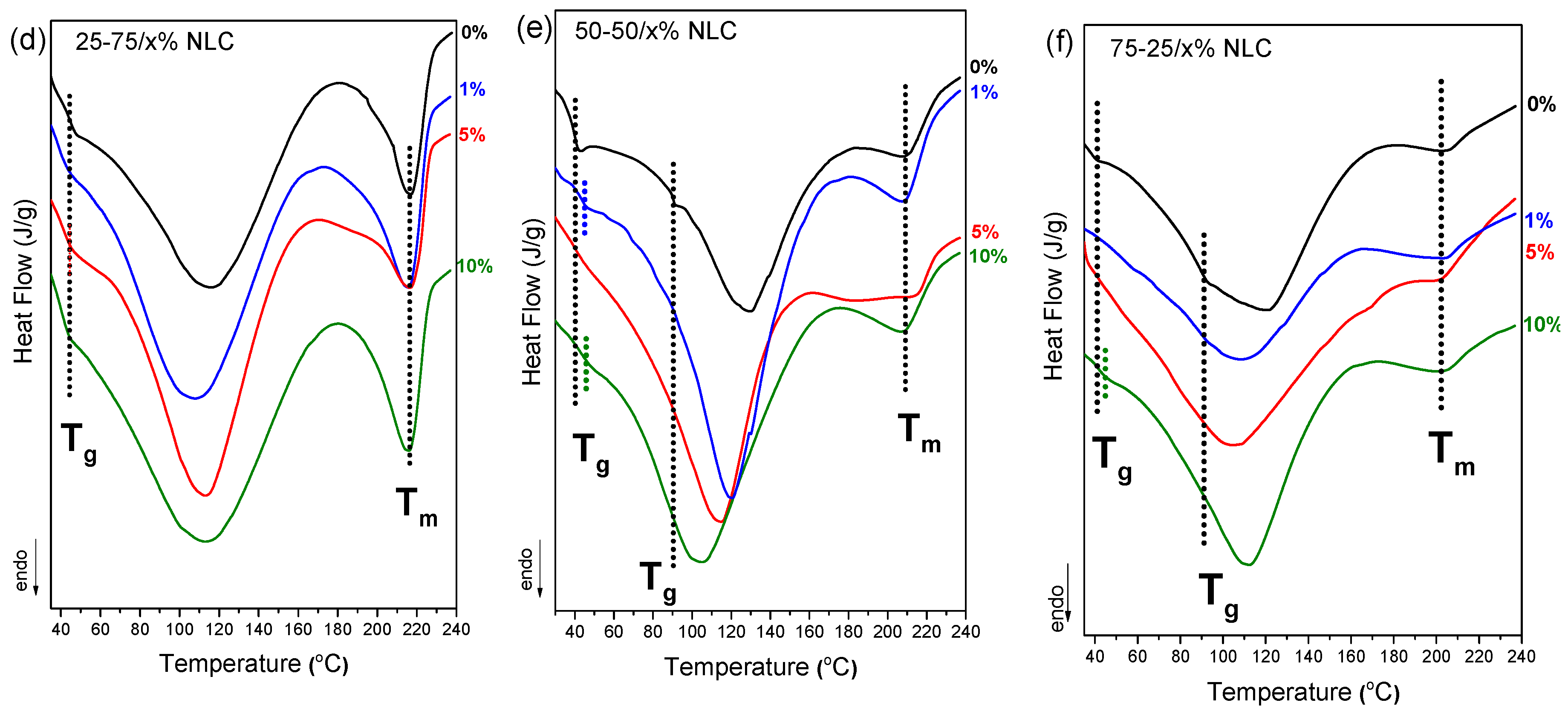

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis was performed to investigate the thermal behavior and phase compatibility of chitosan/PVA nanocellulose composites with varying CNC and NLC content, as depicted in

Figure 6. In the control samples (0% nanocellulose), the 50-50 and 75-25 chitosan/PVA blends show limited miscibility as discussed earlier, with 2 distinct T

g being observed in both cases. Upon incorporation of CNC at 1–10% concentrations, a single T

g was observed across all compositions (

Figure 6.a–c). The appearance of a single, well-defined glass transition temperature (T

g) indicates the formation of a more homogeneous polymer network and serves as evidence of enhanced miscibility. Nanocellulose, due to its ability to form strong hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl groups of PVA and in turn, PVA with the amino groups of chitosan, acts as a compatibilizer by reinforcing intermolecular interactions. This behavior likely explains the observed improvement in polymer miscibility across all blend ratios. Similar results have been observed in the case of NLC composite blends (

Figure 6.d-f).

Moreover, the degree of crystallinity of the PVA phase in each chitosan/PVA/nanocellulose composite was quantified, by normalizing the enthalpy of the endothermic melting peak to the PVA mass fraction. As summarized in

Table 1, the 1% nanocellulose inclusions consistently yielded the highest crystallinity indices across all blend ratios, reaching approximately 40-45 % for 25-75 composites (40.3 % CNC, 46.7 % NLC), ~37 % for 50-50 composites, and ~50 % for 75-25 based membranes (55.0 % CNC, 48.0 % NLC). In each series, further increases in filler content (5 % and 10 %) led to a gradual reduction of PVA crystallinity, suggesting that low levels of nanocellulose act as more effective nucleating agents whereas higher loadings despite they also enhance crystallinity, the increment is lower [

42,

43]. Furthermore, the melting temperature (T

m) was consistently observed to almost the same value after each nanocellulose inclusion, apart from 50-50 blend, in which especially CNC, expands the melting endotherm peak.

3.2.2. Macroscopic Properties

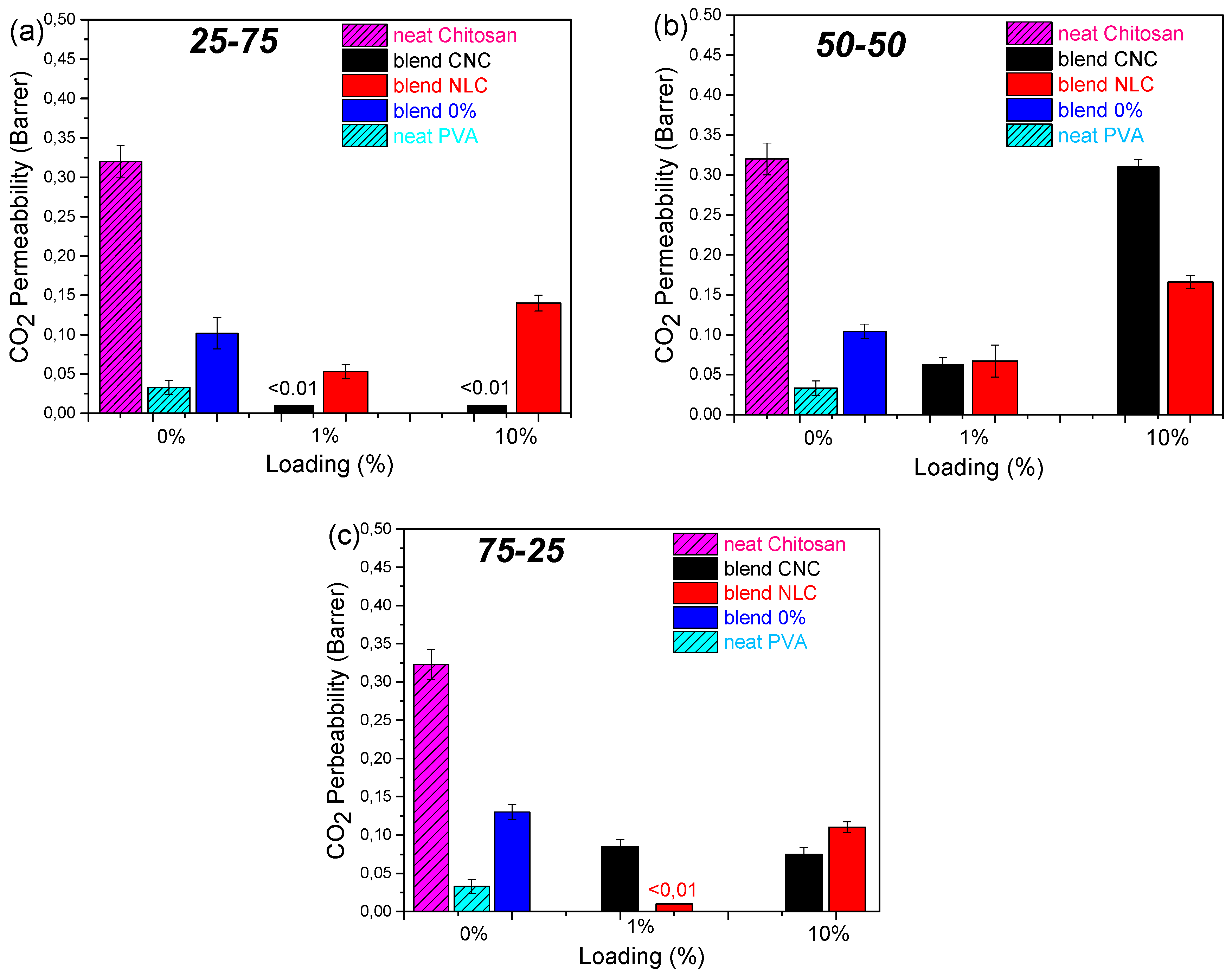

Gas Permeability Measurements

In contrast to the already studied oxygen and water vapor permeability in chitosan/PVA and chitosan/PVA/cellulose composites intended for food packaging materials [

24,

26,

44], carbon dioxide permeability remains largely uncharted to date. Since CO₂ plays a pivotal role in several packaging applications (some of them requiring blockage and others controlled permeation), where precise control of gas composition is required to suppress microbial growth, retard enzymatic browning, and extend the shelf life of fresh product, relevant CO

2 permeability measurements considered as a necessity [

45,

46]. Because CO₂ exhibits a higher solubility and distinct quadrupolar interactions with polymer chains compared to O₂ and N₂, its diffusion mechanism and barrier requirements diverge significantly from those of other gases.

Gas permeability measurements were performed on all chitosan/PVA/nanocellulose composites to elucidate the influence of filler type, loading level, and polymer blend ratios on CO₂, O₂, and N₂ permeability properties for potential packaging applications (

Figure 7). Neat chitosan (

Figure S8) exhibited the highest CO₂ permeability (0.32 Barrer), while neat PVA displayed the lowest value (0.033 Barrer); the neat 25-75, 50-50, and 75-25 blend membranes yielded intermediate permeabilities from 0.12 to 0.20 Barrer.

A pronounced suppression of CO₂ permeability was observed at 1 wt % loading for both CNC and NLC across all matrix compositions, in agreement with the maximization of crystallinity index determined by DSC. At this low filler concentration, CNC and NLC act as efficient nucleating agents, promoting denser crystalline regions within the PVA phase and thereby reducing amorphous free volume available for gas diffusion [

46]. Optimal dispersion further extends the diffusion pathway, enhancing tortuosity and barrier performance. By contrast, higher filler loadings induce particle aggregation and localized micro void formation, which compromise matrix consistency and elevate gas permeability [

48].

However, apart from these general observations on wt% loading effect, incorporation of CNC into PVA-rich matrix (25-75), shows a dramatic permeability reduction at 1 wt % CNC, where permeability fell below the detection limit (< 0.01 Barrer) and remained suppressed even at loadings up to 10%. In contrast, NLC showed a preferential behavior to chitosan-rich blend (75-25), in which total blockage of CO

2 was observed. Both nanocellulose types at 1% loading on 50-50 blend shows an equivalent 50% reduction in permeability, while higher loading in this case further disrupting the matrix consistency are leading to high CO

2 permeation. Furthermore, neat PVA exhibited minimal O₂ and N₂ permeation (0.0023 and 0.0013 Barrer, respectively), which was entirely suppressed upon incorporation of either nanocellulose. These selective enhancements of CO₂ barrier properties are ascribed to preferential interactions and network formation of CNC within PVA domains [

16] and of long-fiber NLC within chitosan domains, both of which increase path tortuosity and diminish free volume in the corresponding matrices.

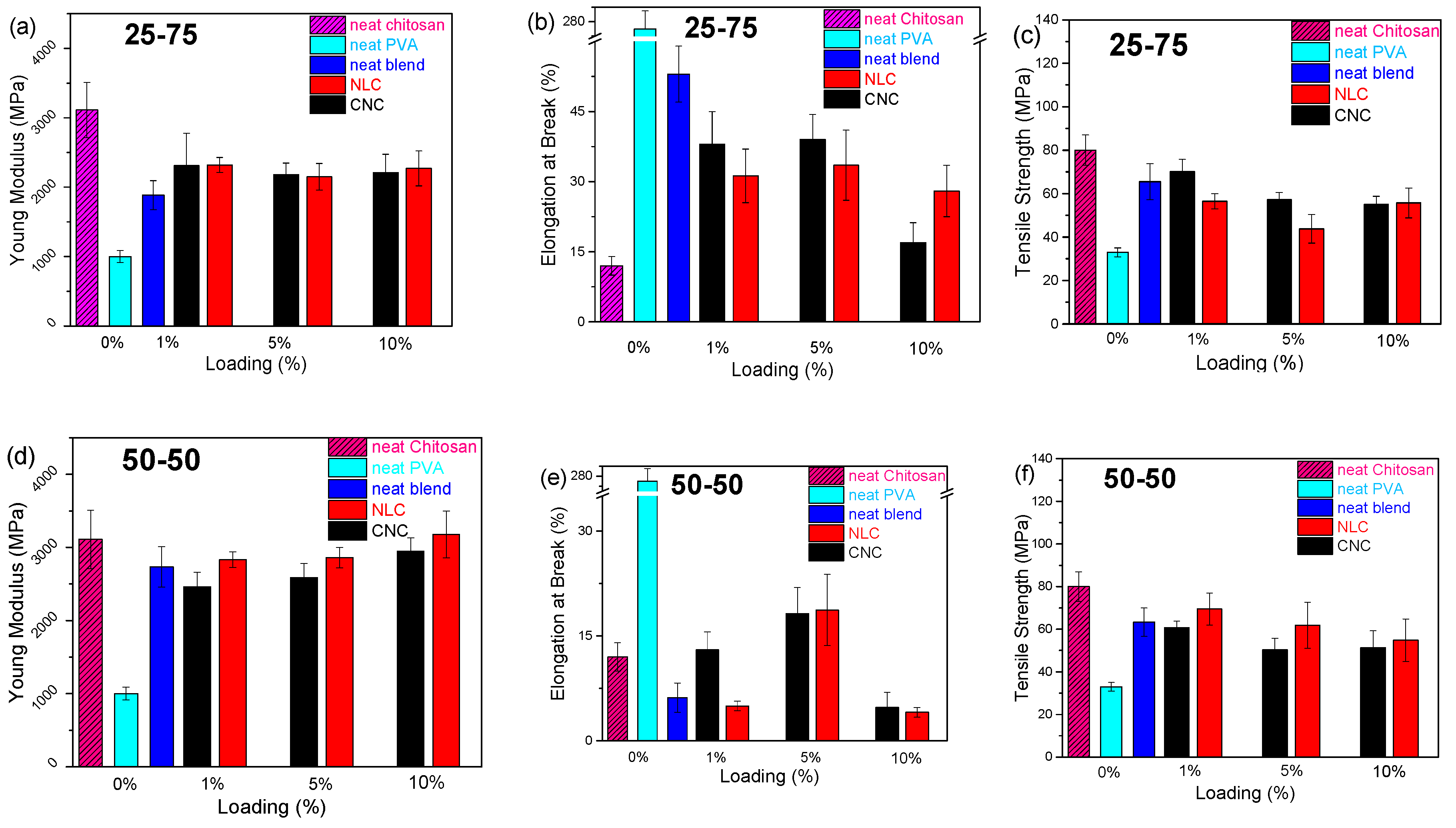

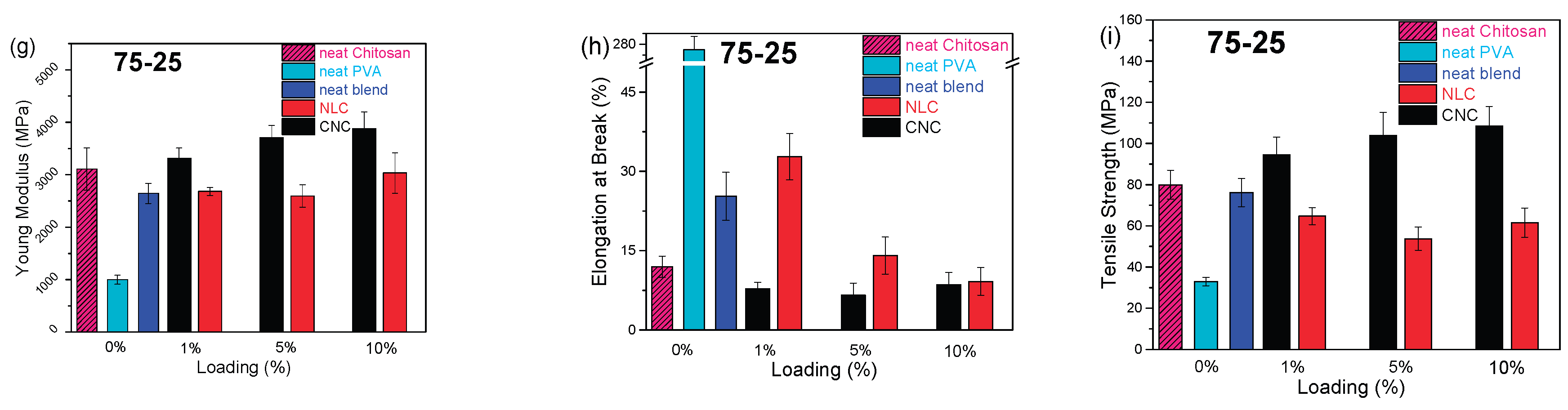

Mechanical Properties

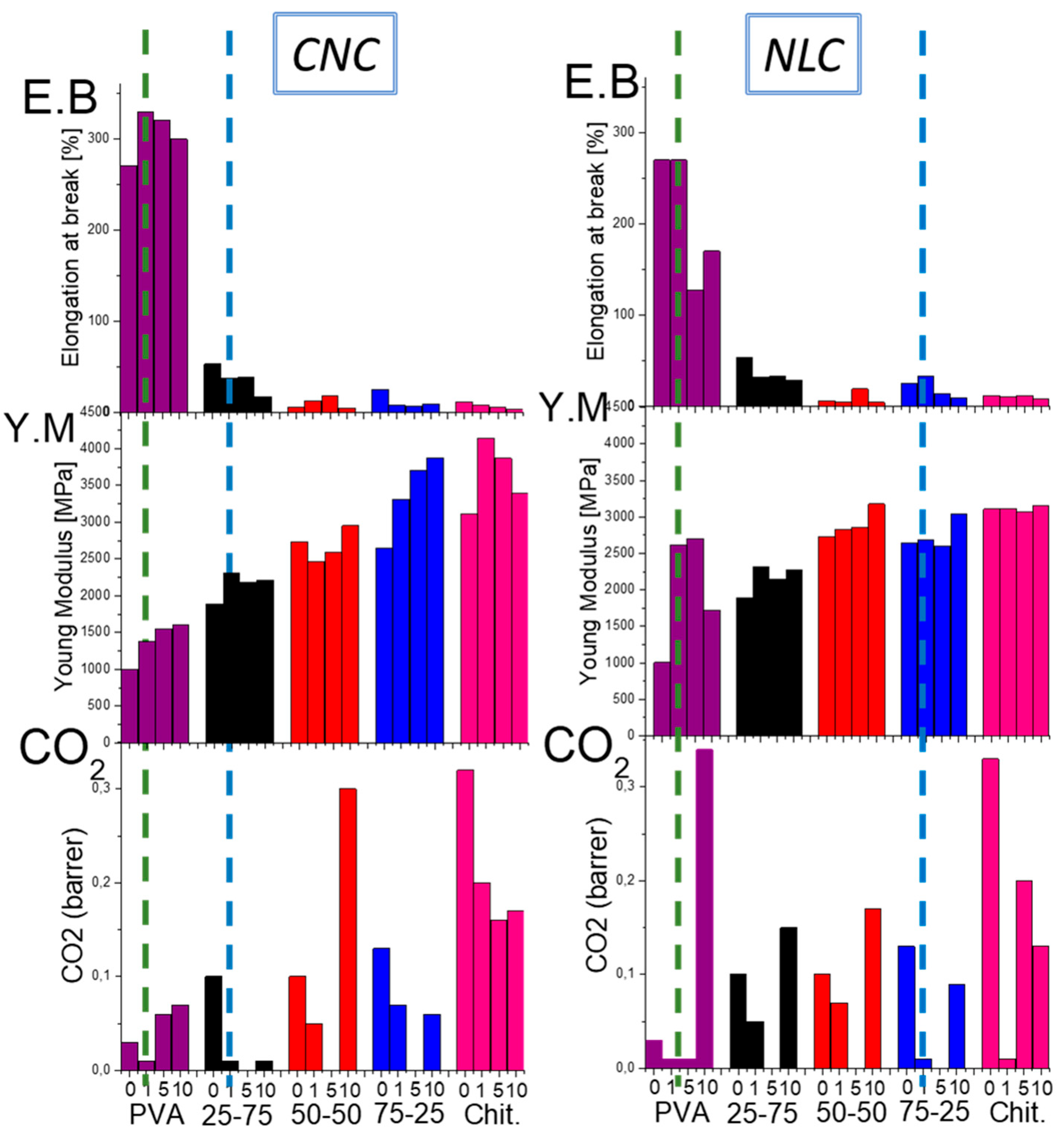

A comparative evaluation of mechanical properties is essential when introducing a multiparametric composite system for food packaging applications. Tensile strength, Young’s modulus and elongation at break have been quantified across the varying polymer blend ratios and nanocellulose types/loadings with rigid CNC versus flexible, extended NLC fibrous network offering different contributions.

Figure 8 shows a summarizing map of both Young’s Modulus, elongation at break and Tensile Strength bar plots versus loading, with all the data collected from typical stress-strain curves (

25-75 in Figure S10, 50-50 in Figure S11 and 75-25 in Figure S12).

The reinforcing effect of CNC on chitosan/PVA blends is first examined (

Figure 8, black bars). In PVA-rich matrices (25-75 chitosan/PVA,

Figure 8a-c), CNC addition induced a modest increase in Young’s modulus from 1.8 to 2.3 GPa, while elongation at break is suppressed at moderate loadings (1-5%), and tensile strength declined from ~65 to ~45 MPa. However, the presence of nanocellulose leads to a slight decreasing trend in ductility across all loading levels, suggesting that the presence of nanocrystals hinders the effective transfer of mechanical stress between polymer chains [

49]. This behavior contrasts with previous reports, in which chitosan/PVA/nanocellulose composites containing low chitosan content (<30 wt%) exhibited a slight enhancement in ductility upon the addition of small amounts of nanocellulose [

21,

22,

43]. In the 50-50 system (

Figure 8d-f), the addition of CNC influences both the Young modulus and tensile strength in a manner similar to the PVA-rich blend. The presence of CNC, previously shown to act as a compatibilizing agent between PVA and chitosan by enhancing their miscibility, also facilitates stress transfer between polymer chains due to its high specific surface area and uniform dispersion. This results in a substantial improvement in the composite’s ductility (~70% increase at 5 wt% CNC loading). Notably, dispersion quality plays a crucial role, as evidenced by the 10 wt% CNC composites, where poor dispersion leads to a markedly reduced tensile strength. Conversely, in chitosan-rich blends (75-25,

Figure 8g-i), CNC incorporation yielded the most pronounced modulus and tensile strength gains (up to 25% at 10% loading), with elongation at break being significantly suppressed (~80%), similarly to chitosan composites (

Figure S8).

The impact of long-fiber NLC (

Figure 8, red bars) differed markedly only in some cases. In the 25-75 blend, the lignocellulose increased modulus similarly to CNC at equivalent loadings, despite the 250% increase noted in neat PVA composites, is probably due to different relevance with the newly formed hybrid chitosan-PVA matrix [

16]. The negative effect of NLC on matrix ductility remains similar to the PVA, reaching an almost 100% decrease in higher loadings. In the 50-50 composites, NLC enhanced elongation, maximized at 5 wt %, such as with CNC, while maintaining elasticity and tensile strengths comparable to the unfilled blend, indicating effective stress transfer without embrittlement, again enhancing the compatibility of both polymers. In the 75-25 chitosan/PVA system, the incorporation of 1 wt % NLC yielded a marked increase in elongation at break (approximately from 20 % to 35 %), while Young’s modulus remained essentially unchanged across all loadings. At low to moderate loadings, the inherently high stiffness of the rigid NLC fibers contributes to the composite modulus in a manner similar to that of the chitosan/PVA matrix, yielding negligible net change in initial elastic response. Ultimate tensile strength, by contrast, is governed by the efficiency of stress transfer at the fiber-matrix interface, which may be compromised by the formation of agglomerated domains that act as stress concentrators.

Overall Comparison and Selection of the Appropriate Composites

In an effort to provide an overall comparison and selection of the appropriate composites for packaging applications with specific property requirements, comparative charts of the most useful functional properties, such as ductility (E.B), modulus of elasticity (Y.M), and CO₂ barrier, are presented (

Figure 9).

The matrix-selective reinforcement and CO2 barrier enhancements offered by CNC and NLC, then, can be understood in terms of filler/polymer affinity, dispersion quality, and network formation, which together govern both mechanical and permeability properties. CNC, with its highly hydroxylated surface and nanoscopic dimensions, exhibits superior compatibility and uniform dispersion within PVA-rich domains with the preferable interaction promoting crystalline PVA nucleation, yielding CO₂ tortuosity. Conversely, long fiber NLC preferentially interacts with chitosan via entanglement with the polysaccharide backbone which maximizes CO₂ pathway tortuosity, while the network of NLC interrupts the matrix affinity due to enhanced formation of agglomerating domains.

Through this study, one can easily identify the optimal composite according to the property demands of the preferred application. For example, if the application requires packaging with high ductility while being gas barrier, then PVA composites with CNC or NLC at a 1% concentration are suitable (

Figure 9 green dot lines), whereas if the preferred property is an increased modulus of elasticity, the chitosan-rich 75-25 blend with 1% NLC and the 25-75 blend with 1% CNC are ideal (

Figure 9 blue dot lines).

Table 2.

Young’s Modulus, Elongation at break and Tensile Strength of chitosan/PVA composite membranes.

Table 2.

Young’s Modulus, Elongation at break and Tensile Strength of chitosan/PVA composite membranes.

| Sample description |

Young Modulus (MPa) |

Elongation at Break (%) |

Tensile Strength (MPa) |

| 0:100 0% |

1002±86 |

270±25 |

33±2 |

| 100:0 0% |

3111±400 |

12±2 |

80±7 |

| 25-75 0% |

1850±190 |

53±6 |

65±8 |

| 25-75 1% CNC/ NLC |

2310±468 |

2320±108 |

38±7 |

31±6 |

70±6 |

56±3 |

| 25-75 5% CNC/ NLC |

2180±167 |

2150±193 |

39±5 |

33±7 |

57±3 |

44±7 |

| 25-75 10% CNC/ NLC |

2210±265 |

2270±250 |

17±4 |

28±5 |

55±4 |

56±7 |

| 50-50 0% |

2732±276 |

6±2 |

63±7 |

| 50-50 1% CNC/ NLC |

2462±198 |

2832±108 |

13±3 |

5±1 |

61±3 |

70±7 |

| 50-50 5% CNC/ NLC |

2588±191 |

2861±139 |

18±4 |

19±5 |

50±5 |

62±11 |

| 50-50 10% CNC/ NLC |

2950±180 |

3176±320 |

5±2 |

4±1 |

51±8 |

55±10 |

| 75-25 0% |

1886±209 |

25±4 |

76±7 |

| 75-25 1% CNC/ NLC |

3316±196 |

2686±77 |

8±1 |

33±4 |

95±8 |

65±4 |

| 75-25 5% CNC/ NLC |

3710±229 |

2594±215 |

7±2 |

14±3 |

104±11 |

54±6 |

| 75-25 10% CNC/ NLC |

3880±317 |

3037±385 |

9±2 |

9±2 |

109±9 |

62±7 |

4. Conclusions

This study has highlighted the key characteristics and critical parameters that determine the functionality of chitosan/PVA/nanocellulose composite membranes for potential food packaging applications. Firstly, it was confirmed that the chitosan/PVA ratio is the primary factor governing their miscibility. The 25-75 (chitosan/PVA) blend exhibited a single-phase morphology, a smooth surface (as observed via SEM on cross-sectional images), and thermal behavior indicative of a homogeneous phase (i.e., a single intermediate glass transition temperature, Tg). In contrast, the 50-50 blend presented phase separation, negatively impacting mechanical properties. This was supported by the appearance of structural discontinuities (observed voids in SEM images) and the presence of two distinct Tg values, each one corresponding to each polymer. The 75-25 composition showed intermediate miscibility characteristics.

The incorporation of nanocellulose, either as cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) or nano-lignocellulose (NLC), proved to play a catalytic role in developing the crystalline network of PVA, particularly at 1 wt.% loading. At this concentration, the highest crystallinity values were recorded for all blend ratios (~40-55%), attributed to the nucleating action of nanocellulose. Moreover, optimal dispersion at low loadings resulted in remarkably low CO₂ permeability values (<0.01 Barrer) for CNC composites at the 25-75 ratio, with similarly low values observed for NLC composites at the 75-25 ratio. In contrast, higher loadings (5-10 wt.%) negatively affected performance, reducing PVA crystallinity and significantly increasing CO₂ permeability. This is likely due to filler agglomeration and the presence of localized areas within the matrix devoid of filler/nucleation sites.

The choice of nanocellulose type showed distinct effects depending on the polymer matrix: CNC was more effective in PVA-rich blends, enhancing CO₂ barrier performance and elasticity, while NLC improved the performance of chitosan-rich composites by forming a more tortuous diffusion path and thus minimizing gas permeation across the membrane. SEM and ATR-FTIR analyses confirmed that CNCs, due to their ideal aspect ratio and uniform dispersion, formed a stable network within the PVA matrix through extensive hydrogen bonding. In contrast, NLC, due to its longer fibers and weak (or absent) interaction with chitosan, was prone to aggregation even at low concentrations.

Mechanical testing revealed that the addition of 1 wt.% CNC in the 25-75 composites increased both tensile strength and Young’s modulus without significantly compromising ductility. Similarly, 1 wt.% NLC in the 75-25 composites enhanced tensile strength, with the highest ductility observed at low filler concentrations. At higher concentrations (5-10 wt.%), a decline in coherence and a sharp reduction in ductility were observed due to agglomeration.

The observed hydrogen bonding network between PVA and cellulose within the ternary composites, combined with the chitosan-PVA interaction, underscores the dual role of nanocellulose: enhancing functional performance and simultaneously promoting miscibility between PVA and chitosan. As revealed by XRD, the incorporation of either type of nanocellulose does not disrupt the structural uniformity of the matrix but improves molecular ordering in the amorphous regions, as reflected in increased crystallinity (DSC) and significantly improved gas barrier properties.

Based on a detailed analysis of both mechanical and permeability properties, it was clearly demonstrated that chitosan/PVA/nanocellulose membranes can be tailored to deliver optimized gas barrier performance, enhanced mechanical strength and elasticity, while minimizing environmental impact due to the use of biodegradable, edible raw materials. The performance of nanocomposites is directly influenced by the chitosan/PVA ratio, the type of nanocellulose used, and its loading percentage, offering a wide parameter space for tuning properties to suit modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) applications in an environmentally sustainable manner.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Comparative analysis of various Chitosan/PVA blend ratios: (a) stress-strain curves, (b) Young’s Modulus vs PVA content bar plots, (c) CO2 Permeability vs PVA content bar plots and (d) optical representation of blend films.; Figure S2: High magnification cross-section surface SEM images of Chitosan/CNC composites: (a) 0%, (b) 1%, (c) 5% and (d) 10% loading.; Figure S3: Cross-section surface SEM images of Chitosan/PVA/NLC composites at high magnification. (a) 25-75 1%, (b) 25-75 5%, (c) 25-75 10%, (d) 50-50 1%, (e) 50-50 5%, (f) 50-50 10% , (g) 75-25 1% , (h) 75-25 5%, (i) 75-25 10%.; Figure S4: High magnification cross-section surface SEM images of Chitosan/NLC composites: (a) 1%, (b) 5% and (c) 10% loading.; Figure S5; Optical images of Chitosan/PVA/nanocellulose composites, from left to right: (a) 0-1-5-10% CNC, (b) 1-5-10% NLC and (c) 5% NLC composites of 25-75, 50-50 and 75-25 blends.; Figure S6: ATR-FTIR spectra of Pure Chitosan film, cellulosic inclusion and Chitosan composites: (a) 1%, 5% and 10% CNC. (b) 1%, 5% and 10% NLC.; Figure S7: ATR-FTIR spectra at 4000-2600 cm

-1 spectral window of Pure Chitosan, pure PVA, cellulosic inclusion and 25-75 blend composites: (a) 1%, 5% and 10% CNC, (b) 1%, 5% and 10% NLC.; Figure S8: CO2 permeability (Barrer) bar plot versus cellulose loading of Chitosan/nanocellulose composites: CNC (black) and NLC (red). Values <0.01 Barrer are lower the detection limit.; Figure S9: Young Modulus (a), Elongation at Break (b) and Tensile Strength (c) bar plots vs loading of Chitosan/nanocellulose composites. CNC composites (black), NLC composites (red) and pure chitosan (blue).; Figure S10: Stress-strain curves of 25-75 (Chitosan/PVA) CNC composites (a) and NLC composites (b). The linear region (inlet).; Figure S11: Stress-strain curves of 50-50 (Chitosan/PVA) CNC composites (a) and NLC composites (b). The linear region (inlet).; Figure S12: Stress-strain curves of 75-25 (Chitosan/PVA) CNC composites (a) and NLC composites (b)The linear region (inlet).;

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.P., G.A.V., and K.S.A.; methodology, K.P. and O.K.; software, K.P. and K.S.A.; validation, K.P. and K.S.A.; formal analysis, K.P.; investigation, K.P., G.N.M., N.K., and D.V.; resources, G.A.V.; data curation, K.P. and K.S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, K.P., G.A.V and A.S.B; writing—review and editing, G.A.V., K.S.A., O.K. and G.P.; visualization, K.P., G.N.M., and K.S.A.; supervision, G.A.V., K.S.A. and A.S.B; project administration, G.A.V, A.S.B.; funding acquisition, G.A.V. and G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was co-financed by the European Union and Greek national funds through the Operational Program Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship, and Innovation, under the call RESEARCH—CREATE—INNOVATE (Project name: High Performance Industrial Materials based on Nanocellulose—HIPERION; project code: T2EDK-01394).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Prof. Costas Galiotis for access to the MTS apparatus (mechanical testing) of the Composites and NanoMaterials Lab (CNML) at ICEHT/FORTH, Patras, Greece.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jannatiha. N. and Gutiérrez T.J. Recycling and revalorization of PLA and PHA-based food packaging waste: A review. Sustainable Materials and Technologies, 2025. 44: p. e01364. [CrossRef]

- Meereboer, K.W.; Misra, M.; Mohanty, A.K. Review of recent advances in the biodegradability of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) bioplastics and their composites. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 5519–5558. [CrossRef]

- Cazón, P.; Velazquez, G.; Ramírez, J.A.; Vázquez, M. Polysaccharide-based films and coatings for food packaging: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 68, 136–148. [CrossRef]

- Elsabee, M.Z.; Abdou, E.S. Chitosan based edible films and coatings: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 1819–1841. [CrossRef]

- Muxika, A.; Etxabide, A.; Uranga, J.; Guerrero, P.; de la Caba, K. Chitosan as a bioactive polymer: Processing, properties and applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 105, 1358–1368. [CrossRef]

- Lan, W.; Wang, S.; Chen, M.; Sameen, D.E.; Lee, K.; Liu, Y. Developing poly(vinyl alcohol)/chitosan films incorporated with D-limonene: Study of structural, antibacterial, and fruit preservation properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 145, 722–732. [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, M.; Morsi, R.E.; Kerch, G.; Elsabee, M.Z.; Kaya, M.; Labidi, J.; Khawar, K.M. Current advancements in chitosan-based film production for food technology: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 121, 889–904. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Chaparro, P.; Gutierrez-Mendez, N.; Salas-Muñoz, E.; Ayala-Soto, J.G.; Chavez-Flores, D.; Hernández-Ochoa, L. Effect of the addition of essential oils and functional extracts of clove on physicochemical properties of chitosan-based films. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2015, 714254. [CrossRef]

- Rubilar, J.F.; Cruz, R.M.S.; Silva, H.D.; Vicente, A.A.; Khmelinskii, I.; Vieira, M.C. Physico-mechanical properties of chitosan films with carvacrol and grape seed extract. J. Food Eng. 2013, 115, 466–474. [CrossRef]

- Kołodziejska, M.; Jankowska, K.; Klak, M.; Wszoła, M. Chitosan as an underrated polymer in modern tissue engineering. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3019. [CrossRef]

- Zu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Shan, C.; Zu, S.; Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Ge, Y. Preparation and characterization of chitosan–polyvinyl alcohol blend hydrogels for the controlled release of nano-insulin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012, 50, 82–87. [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Yasin, T. Controlled delivery of drug from pH sensitive chitosan/poly(vinyl alcohol) blend. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 88, 1055–1060. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, D.; Sun, Y.; Li, J. Prediction on the compatibility of chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol blend based on Schneier mixing enthalpy. Thermochim. Acta 2022, 714, 179251. [CrossRef]

- Jawalkar, S.S.; Halligudi, S.B.; Sairam, M.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Molecular modeling simulations to predict compatibility of poly(vinyl alcohol) and chitosan blends: A comparison with experiments. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 2431–2439. [CrossRef]

- Naveen Kumar, H.M.P.; Prabhakar, M.N.; Venkata Prasad, C.; Madhusudhan Rao, K.; Ashok Kumar Reddy, T.V.; Chowdoji Rao, K.; Subha, M.C.S. Compatibility studies of chitosan/PVA blend in 2% aqueous acetic acid solution at 30 °C. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 82, 251–255. [CrossRef]

- Papapetros, K.; Mathioudakis, G.N.; Vroulias, D.; Koutroumanis, N.; Voyiatzis, G.A.; Andrikopoulos, K.S. Structure-properties correlations of PVA-cellulose based nanocomposite films for food packaging applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 1911. [CrossRef]

- Fortunati, E.; Puglia, D.; Luzi, F.; Santulli, C.; Kenny, J.M.; Torre, L. Binary PVA bio-nanocomposites containing cellulose nanocrystals extracted from different natural sources: Part I. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 97, 825–836. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Wang, S.; Rials, T.G. Poly(vinyl alcohol) nanocomposites reinforced with cellulose fibrils isolated by high intensity ultrasonication. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2008, 40, 218–224. [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M.-C. Structure and sorption properties of CNC reinforced PVA films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 101, 783–790. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, M.; Chauhan, G.S.; Kaushik, A.; Sharma, A. Extraction and functionalization of bagasse cellulose nanofibres to Schiff-base based antimicrobial membranes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 91, 887–894. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Biagioni, P.; Finazzi, M.; Bruni, G.; Castellano, M. Tunable green oxygen barrier through layer-by-layer self-assembly of chitosan and cellulose nanocrystals. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 92, 2128–2134. [CrossRef]

- Luzi, F.; Fortunati, E.; Giovanale, G.; Mazzaglia, A.; Torre, L.; Balestra, G.M. Revalorization of barley straw and husk as precursors for cellulose nanocrystals extraction and their effect on PVA_CH nanocomposites. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 92, 201–217. [CrossRef]

- Fortunati, E.; Benincasa, P.; Balestra, G.M.; Luzi, F.; Mazzaglia, A.; Del Buono, D.; Puglia, D.; Torre, L. Revalorization of barley straw and husk as precursors for cellulose nanocrystals extraction and their effect on PVA/CH nanocomposites. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 92, 201–217. [CrossRef]

- Azizi, S.; Ahmad, M.B.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Hussein, M.Z.; Namvar, F. Preparation and properties of poly(vinyl alcohol)/chitosan blend bio-nanocomposites reinforced by cellulose nanocrystals. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2014, 32, 1620–1627. [CrossRef]

- Perumal, A.B.; Sellamuthu, P.S.; Nambiar, R.B.; Sadiku, E.R. Development of polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan bio-nanocomposite films reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals isolated from rice straw. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 449, 591–602. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-Z.; Chen, S.-C.; Wang, Y.-Z. Preparation and characterization of nanocomposites of polyvinyl alcohol/cellulose nanowhiskers/chitosan. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2015, 115, 60–65. [CrossRef]

- Solikhin, A.; Hadi, Y.S.; Massijaya, M.Y.; Nikmatin, S.; Suzuki, S.; Kojima, Y.; Kobori, H. Properties of poly(vinyl alcohol)/chitosan nanocomposite films reinforced with oil palm empty fruit bunch amorphous lignocellulose nanofibers. J. Polym. Environ. 2018, 26, 3316–3333. [CrossRef]

- Penloglou, G.; Tissink, A.; Bakola, V.; Kotrotsiou, O.; Pavlou, A.; Kiparissides, C. Efficient conversion of an underutilized low-lignin lignocellulosic biomass to cellulose nanocrystals and nanofibers via mild chemical-mechanical protocols. Biores. Technol. Rep. 2024. 25, 101799. [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Liu, D.; Tian, H.; Xiang, A. Non-isothermal crystallization kinetics of polyvinyl alcohol plasticized with glycerol and pentaerythritol. J. Polym. Res. 2020, 27, 66. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D882-18. Standard test method for tensile properties of thin plastic sheeting. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- Neto, C.G.T.; Giacometti, J.A.; Job, A.E.; Ferreira, F.C.; Fonseca, J.L.C.; Pereira, M.R. Thermal analysis of chitosan based networks. Carbohydr. Polym. 2005, 62, 97–103. [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, K. Miscibility and thermal stability of poly(vinyl alcohol)/chitosan mixtures. Thermochim. Acta 2009, 493, 42–48. [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Bin, Y.; Bando, M.; Nakashima, T.; Okuno, T.; Kurosu, H.; Matsuo, M. Structure and mechanical properties of chitosan/poly(vinyl alcohol) blend films. Macromol. Symp. 2007, 258, 63–81. [CrossRef]

- Costa-Júnior, E.S.; Barbosa-Stancioli, E.F.; Mansur, A.A.P.; Vasconcelos, W.L.; Mansur, H.S. Preparation and characterization of chitosan/poly(vinyl alcohol) chemically crosslinked blends for biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 76, 472–481. [CrossRef]

- Sakkara, S.; Nataraj, D.; Venkatesh, K.; Reddy, N. Influence of alkali treatment on the physicochemical and mechanical properties of starch chitosan films. Starch-Stärke 2018, 70, 1800084. [CrossRef]

- Maréchal, Y.; Chanzy, H. The hydrogen bond network in Iβ cellulose as observed by infrared spectrometry. J. Mol. Struct. 2000, 523, 183–196. [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.Y.; Yoo, D.I.; Shin, Y.; Kim, H.C.; Kim, H.Y.; Chung, Y.S.; Park, W.H.; Youk, J.H. Crystalline structure analysis of cellulose treated with sodium hydroxide and carbon dioxide by means of X-ray diffraction and FTIR spectroscopy. Carbohydr. Res. 2005, 340, 2376–2391. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Sun, X.; Tian, H.; Maiti, S.; Ma, Z. Effects of cellulose nanofibrils on the structure and properties on PVA nanocomposites. Cellulose 2013, 20, 2981–2989. [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, K.; Yui, T.; Okuyama, K. Three-D structures of chitosan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2004, 34, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, K.; Noguchi, K.; Miyazawa, T.; Yui, T.; Ogawa, K. Molecular and crystal structure of hydrated chitosan. Macromolecules 1997, 30, 5849–5855. [CrossRef]

- French, A.D. Idealized powder diffraction patterns for cellulose polymorphs. Cellulose 2014, 21, 885–896. [CrossRef]

- Ning, N.; Fu, S.; Zhang, W.; Chen, F.; Wang, K.; Deng, H.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, Q. Realizing the enhancement of interfacial interaction in semicrystalline polymer/filler composites via interfacial crystallization. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 1425–1455. [CrossRef]

- Menczel, J.D.; Prime, R.B. Thermal Analysis of Polymers: Fundamentals and Applications; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009.

- Chen, X.; Lan, W.; Xie, J. Characterization of active films based on chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol integrated with ginger essential oil-loaded bacterial cellulose and application in sea bass (Lateolabrax japonicus) packaging. Food Chem. 2024, 441, 138343. [CrossRef]

- Caleb, O.J.; Mahajan, P.V.; Al-Said, F.A.; Opara, U.L. Modified atmosphere packaging technology of fresh and fresh-cut produce and the microbial consequences—A review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 303–329. [CrossRef]

- Puligundla, P.; Jung, J.; Ko, S. Carbon dioxide sensors for intelligent food packaging applications. Food Control 2012, 25, 328–333. [CrossRef]

- Idris, A.; Muntean, A.; Mesic, B.; Lestelius, M.; Javed, A. Oxygen barrier performance of poly(vinyl alcohol) coating films with different induced crystallinity and model predictions. Coatings 2021, 11, 1253. [CrossRef]

- Idris, A.; Muntean, A.; Mesic, B. A review on predictive tortuosity models for composite films in gas barrier applications. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2022, 19, 699–716. [CrossRef]

- El Miri, N.; Abdelouahdi, K.; Zahouily, M.; Fihri, A.; Barakat, A.; Solhy, A.; El Achaby, M. Bio-nanocomposite films based on cellulose nanocrystals filled polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan polymer blend. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132, 42004. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Cross-section surface SEM images of chitosan/PVA blends at high magnification. (a) 25-75, (b) 50-50 and (c) 75-25.

Figure 1.

Cross-section surface SEM images of chitosan/PVA blends at high magnification. (a) 25-75, (b) 50-50 and (c) 75-25.

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of various chitosan/PVA blend ratios by: (a) DSC, (b) Elongation at Break vs PVA content bar plots, (c) ATR-FTIR spectra and (d) XRD graphs.

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of various chitosan/PVA blend ratios by: (a) DSC, (b) Elongation at Break vs PVA content bar plots, (c) ATR-FTIR spectra and (d) XRD graphs.

Figure 3.

Cross-section surface SEM images of chitosan/PVA/CNC composites at high magnification. (a) 25-75 1%, (b) 25-75 5%, (c) 25-75 10%, (d) 50-50 1%, (e) 50-50 5%, (f) 50-50 10%, (g) 75-25 1%, (h) 75-25 5%, (i) 75-25 10%.

Figure 3.

Cross-section surface SEM images of chitosan/PVA/CNC composites at high magnification. (a) 25-75 1%, (b) 25-75 5%, (c) 25-75 10%, (d) 50-50 1%, (e) 50-50 5%, (f) 50-50 10%, (g) 75-25 1%, (h) 75-25 5%, (i) 75-25 10%.

Figure 4.

ATR-FTIR spectra in the 1700-700 cm-1 spectral window of chitosan/PVA/nanocellulose composites. (a) 25-75 x% CNC, (b) 50-50 x% CNC, (c) 75-25 x% CNC, (d) 25-75 x% NLC, (e) 50-50 x% NLC, (f) 75-25 x% NLC.

Figure 4.

ATR-FTIR spectra in the 1700-700 cm-1 spectral window of chitosan/PVA/nanocellulose composites. (a) 25-75 x% CNC, (b) 50-50 x% CNC, (c) 75-25 x% CNC, (d) 25-75 x% NLC, (e) 50-50 x% NLC, (f) 75-25 x% NLC.

Figure 5.

X-Ray diffraction graphs of chitosan/PVA/nanocellulose composites. (a) 25-75 x% CNC, (b) 50-50 x% CNC, (c) 75-25 x% CNC, (d) 25-75 x% NLC, (e) 50-50 x% NLC, (f) 75-25 x% NLC.

Figure 5.

X-Ray diffraction graphs of chitosan/PVA/nanocellulose composites. (a) 25-75 x% CNC, (b) 50-50 x% CNC, (c) 75-25 x% CNC, (d) 25-75 x% NLC, (e) 50-50 x% NLC, (f) 75-25 x% NLC.

Figure 6.

DSC thermographs of chitosan/PVA/nanocellulose composites. (a) 25-75 x% CNC, (b) 50-50 x% CNC, (c) 75-25 x% CNC, (d) 25-75 x% NLC, (e) 50-50 x% NLC, (f) 75-25 x% NLC.

Figure 6.

DSC thermographs of chitosan/PVA/nanocellulose composites. (a) 25-75 x% CNC, (b) 50-50 x% CNC, (c) 75-25 x% CNC, (d) 25-75 x% NLC, (e) 50-50 x% NLC, (f) 75-25 x% NLC.

Figure 7.

CO2 permeability (Barrer) bar plot versus cellulose loading of chitosan/PVA/nanocellulose composites: (a) 25-75 (b) 50-50 and (c) 75-25. Values <0.01 Barrer are lower the detection limit.

Figure 7.

CO2 permeability (Barrer) bar plot versus cellulose loading of chitosan/PVA/nanocellulose composites: (a) 25-75 (b) 50-50 and (c) 75-25. Values <0.01 Barrer are lower the detection limit.

Figure 8.

Young Modulus (Y.M), Elongation at Break (E.B) and Tensile Strength (T.S) bar plots vs loading of chitosan/PVA/nanocellulose composites. CNC composites (black), NLC composites (red) and neat blends (blue). (a) 25-75 Y.M, (b) 25-75 E.B, (c) 25-75 T.S. (d) 50-50 Y.M, (e) 50-50 E.B, (f) 50-50 T.S. (g) 75-25 Y.M, (h) 75-25 E.B, (i) 75-25 T.S.

Figure 8.

Young Modulus (Y.M), Elongation at Break (E.B) and Tensile Strength (T.S) bar plots vs loading of chitosan/PVA/nanocellulose composites. CNC composites (black), NLC composites (red) and neat blends (blue). (a) 25-75 Y.M, (b) 25-75 E.B, (c) 25-75 T.S. (d) 50-50 Y.M, (e) 50-50 E.B, (f) 50-50 T.S. (g) 75-25 Y.M, (h) 75-25 E.B, (i) 75-25 T.S.

Figure 9.

Comparative chart of the main functional properties (elongation at break E.B, modulus of elasticity Y.M and CO₂ permeability) of all possible combinations of CNC and NLC composites, aiming at the selection of the appropriate composites for each application.

Figure 9.

Comparative chart of the main functional properties (elongation at break E.B, modulus of elasticity Y.M and CO₂ permeability) of all possible combinations of CNC and NLC composites, aiming at the selection of the appropriate composites for each application.

Table 1.

Crystallinity Index and melting temperature of chitosan/PVA composite membranes.

Table 1.

Crystallinity Index and melting temperature of chitosan/PVA composite membranes.

| Sample description |

Crystallinity index (%) |

Melting point (oC) |

| 0:100 0% |

41 |

227 |

| 100:0 0% |

Non Detected |

Non Detected |

| 25-75 0% |

26.0 |

216.7 |

| 25-75 1% CNC/NLC |

40.5 |

46.5 |

215.0 |

215.0 |

| 25-75 5% CNC/NLC |

39.0 |

43.0 |

215.0 |

215.0 |

| 25-75 10% CNC/NLC |

33.0 |

43.0 |

213.5 |

215.0 |

| 50-50 0% |

27.0 |

210.0 |

| 50-50 1% CNC/NLC |

38.5 |

36.5 |

210.0 |

207.5 |

| 50-50 5% CNC/NLC |

31.0 |

30.5 |

210.0 |

205.0 |

| 50-50 10% CNC/NLC |

28.5 |

32.0 |

210.0 |

207.0 |

| 75-25 0% |

39.0

|

205.0 |

| 75-25 1% CNC/NLC |

55.0

|

48.0 |

205.0 |

205.0 |

| 75-25 5% CNC/NLC |

52.0

|

41.0 |

205.0 |

205.0 |

| 75-25 10% CNC/NLC |

38.0

|

39.0 |

202.0 |

205.0 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).