1. Introduction

According to the Global Cancer Statistics 2022, colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality in both sexes and ranks third in terms of incidence [

1]. Colonoscopy remains the gold standard for colorectal cancer screening, as it enables the early detection of malignant and premalignant lesions. However, its diagnostic accuracy is highly dependent on the quality of bowel preparation, which ensures adequate visualization of the mucosa and potential abnormalities [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Inadequate bowel cleansing may result in missed lesions, prolonged procedure times, and the need for repeat colonoscopies, emphasizing the need for effective preparation regimens [

2].

A variety of bowel cleansing agents are available, broadly classified into hyperosmolar solutions and iso-osmotic polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based preparations. The introduction of ascorbic acid, which has a laxative effect, has allowed for a reduction in the required PEG solution volume from 4 liters to 2 liters without compromising efficacy or safety [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

In recent years, ultra-low-volume (<1L PEG) formulations have been developed to further enhance patient compliance. Unlike 2L PEG solutions, 1L PEG formulations contain significantly higher concentrations of sodium ascorbate and ascorbic acid, as well as sodium sulfate, sodium chloride, and potassium chloride [

13].

Currently, Plenvu is the only 1L PEG bowel preparation available on the Slovenian market. Its efficacy and safety have been demonstrated in multiple clinical studies [

8,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

In Slovenia, the traditional approach to bowel preparation has involved 2L PEG (Moviprep) combined with Donat Mg, a mineral water containing magnesium, magnesium sulfate, and sodium sulfate. This combination has been shown to be highly effective in achieving good to excellent bowel cleansing [

24].

In our study, we aimed to compare the effectiveness of different bowel preparation protocols for colonoscopy and assess their acceptability among patients.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a multicenter prospective study that included patients over the age of 18 undergoing elective colonoscopy for diagnostic or screening purposes. The study was carried out at three gastroenterology centers: Diagnostic Center Bled, Diagnostic Center Rogaška, and the Department of Gastroenterology at the University Medical Center Ljubljana. The study was conducted from March 8, 2023, to August 31, 2023.

Patients were randomly assigned to one of three groups, each following a different bowel preparation regimen:

Moviprep + Donat Mg group: Patients consumed 2 liters of Moviprep solution and 2 liters of Donat Mg.

Plenvu group: Patients consumed 1 liter of Plenvu and 1 liter of clear water.

Plenvu + Donat Mg group: Patients consumed 1 liter of Plenvu, 2 liters of Donat Mg, and 1 liter of clear water.

Prior to the procedure, all patients received standardized written instructions detailing the bowel preparation process and the colonoscopy procedure. During the bowel preparation phase, patients completed a questionnaire which assessed nine different categories of side effects, which were selected based on the most commonly reported adverse effects of bowel cleansing agents. Patients rated the severity of each side effect on a scale from 0 (none) to 4 (very severe). Additionally, the questionnaire included a question (Yes/No) on whether they would undergo the same preparation regimen again, and assesment of global tolerability score, ranging from 0 to 10 (with 10 being the best possible rating).

The primary outcomes of the study were bowel cleanliness, assessed using the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS), polyp detection rate (PDR) and adenoma detection rate (ADR). Furthermore, we wanted to evaluate the overall patient experience with bowel preparation, including the assessment of side effects, patient satisfaction with the preparation process, and willingness to use the same preparation method in the future.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

Patient characteristics were compared using the chi-square test, while differences in mean age were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA).

ANOVA was also employed to compare bowel cleanliness, as assessed by the BBPS, the mean number of polyps among groups, and the overall tolerability score. The chi-square test was used to compare PDR and ADR between groups, as well as patients’ willingness to reuse the same bowel preparation regimen (Yes/No responses).

For pairwise comparisons of differences in BBPS scores and the mean number of polyps per colonoscopy, pairwise t-tests were conducted. The chi-square test was used for pairwise comparisons of PDR and ADR.

The evaluation of individual adverse effects was analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test, while the overall tolerability of the bowel preparation was compared using ANOVA.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

A total of 304 patients participated in the study. In four cases, only a partial colonoscopy was performed—one patient had a history of right-sided colectomy, while three underwent incomplete procedures for reasons unrelated to bowel preparation. Patients who underwent only partial colonoscopy were excluded from the final analysis.

Thus, 300 patients were analyzed: 101 from the Clinical Department of Gastroenterology, 101 from DC Bled, and 98 from DC Rogaška. For bowel preparation, 94 patients used Moviprep with Donat Mg, 96 used Plenvu, and 110 used Plenvu with Donat Mg.

The baseline characteristics of the included patients are presented in

Table 1. Statistical analysis revealed a significant difference in the distribution of sex between groups (p = 0.034), but this difference was no longer statistically significant after post-hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction. No statistically significant differences were observed in age characteristics between groups.

3.2. Boston Bowel Preparation Scale

In all patients, bowel cleanliness was assessed using the BBPS. Each colon segment was evaluated separately, along with the total BBPS score. Adequate bowel cleanliness was defined as a total BBPS ≥ 6, with no individual segment scoring less than 2.

Adequate bowel cleanliness was achieved in 96.3% of cases: 97.9% in the Moviprep + Donat Mg group, 95.83% in the Plenvu group, and 95.5% in the Plenvu + Donat Mg group, with no statistically significant differences (p = 0.625).

Analysis of BBPS scores by individual segments and total score did not reveal any statistically significant differences among the three bowel preparation regimens. Similarly, pairwise comparisons between individual groups did not show any statistically significant differences (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

A lower mean score was observed for the right colon compared to the other colon segments within the same bowel preparation regimen. Statistical analysis revealed a significant difference in segmental cleanliness within the Plenvu group (p = 0.036) and the Plenvu + Donat Mg group (p = 0.027). In the Moviprep + Donat Mg group, this difference was not observed, though the results were close to statistical significance (p = 0.058).

3.3. Lesion Detection

Among the 300 colonoscopies performed, polyps were detected in 152 patients and adenomas in 140 patients.

There were no statistically significant differences in polyp or adenoma detection among the analyzed outcomes, including the mean number of polyps per colonoscopy, PDR, ADR, right colon PDR, and right colon ADR (

Table 2). Pairwise comparisons between groups also did not reveal statistically significant differences (

Table 3).

3.4. Bowel Preparation Tolerability and Experience

During bowel preparation for colonoscopy, patients completed a questionnaire assessing their cleansing experience. Adverse effects, categorized into nine groups, were rated on a 0 to 4 scale, where 0 indicated no symptoms and 4 represented a severe adverse effect (

Table 4).

No statistically significant differences were observed in the frequency or severity of adverse effects among the different bowel preparation regimens. The most prominent adverse effect across all three regimens was thirst (

Table 4).

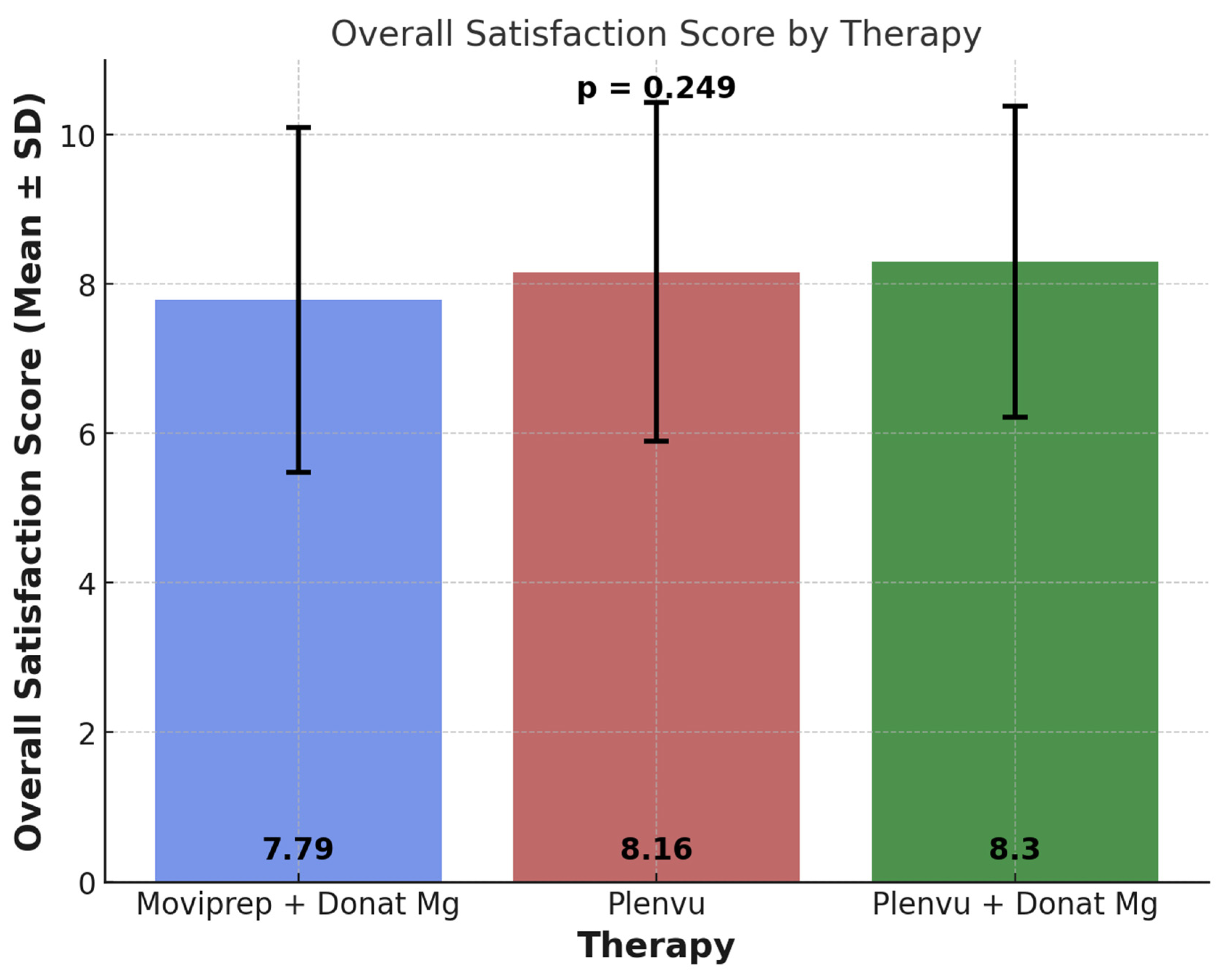

Patients evaluated their overall experience with bowel preparation. The highest average rating was given to the Plenvu + Donat Mg regimen, followed by Plenvu, while the lowest rating was assigned to Moviprep + Donat Mg (

Figure 1). Despite the observed differences in mean scores among the groups, statistical analysis did not reveal a significant difference (p = 0.249).

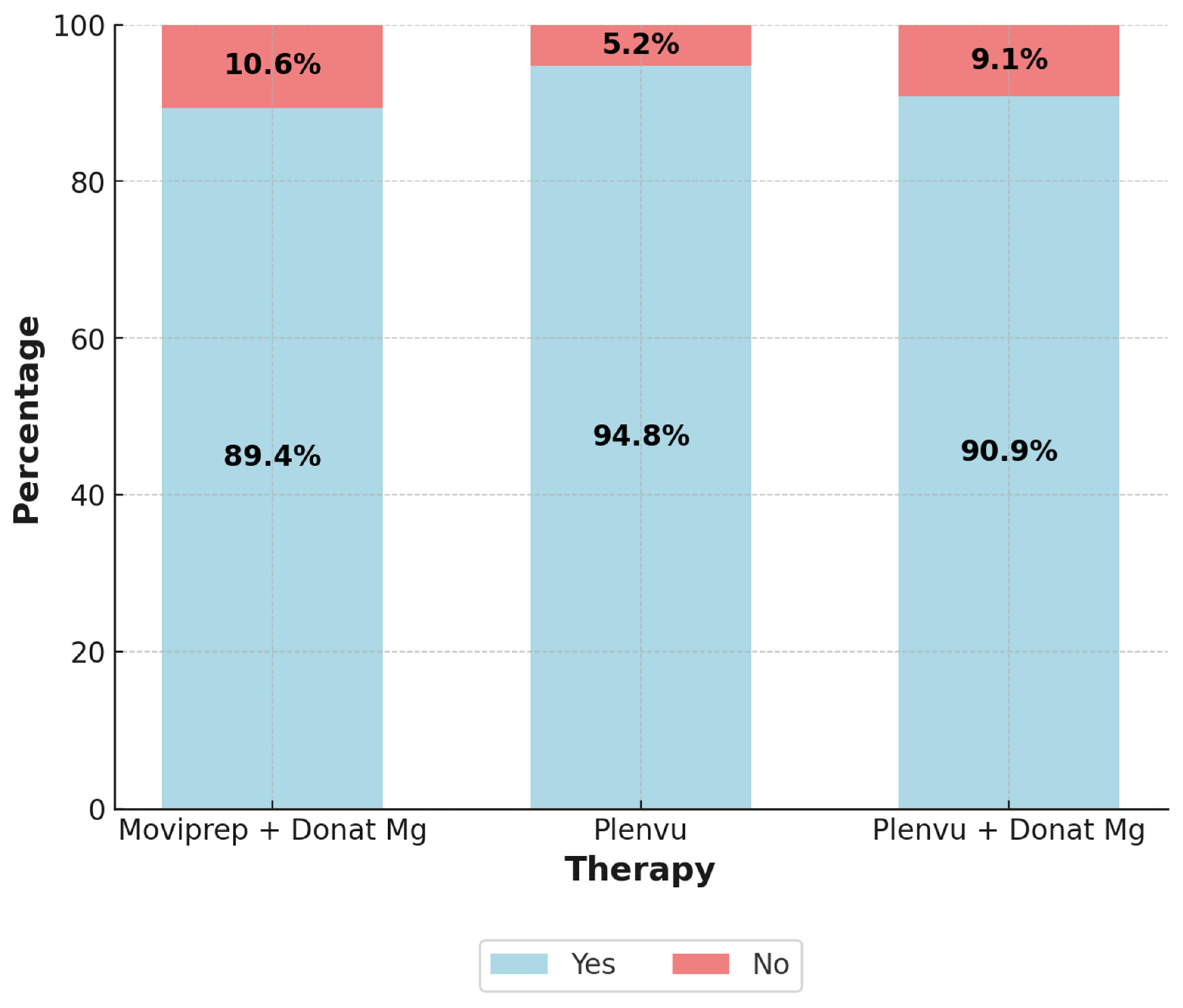

Patients were asked whether they would choose the same bowel preparation regimen if they required a repeat colonoscopy, the results are presented in

Figure 2. Despite the minor differences between groups, statistical analysis did not reveal a significant difference (p = 0.375).

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4. Discussion

Donat Mg mineral water has traditionally been used as a laxative in Slovenia [

25]. Based on a study demonstrating the efficacy of Donat Mg in combination with 2L of PEG, it is also used as a component of bowel preparation regimens for colonoscopy [

24]. Several bowel preparation regimens combine PEG with osmotic, stimulant, or prokinetic agents [

26,

27,

28,

29]. To our knowledge, there was no other study using an agent similar to Donat Mg as an adjunctive component in bowel preparation.

High-quality colonoscopy is essential for the detection and removal of premalignant colorectal lesions, thereby preventing the development of colorectal cancer. The key factor in successful colonoscopy is adequate bowel preparation, as it directly impacts quality indicators such as ADR, cecal intubation rate, procedural safety, and patient tolerability [

3,

4,

5,

6,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

Adequate bowel cleansing, as defined by the BBPS, is a total BBPS score ≥6 with no individual segment scoring below 2, which is considered sufficient to ensure the identification of polyps >5 mm [

35]. It is well established that the right colon more frequently harbors flat lesions, including sessile serrated lesions, which pose a greater challenge for detection [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Additionally, interval colorectal cancers, which result from missed lesions, are more commonly found in the right colon than in the left colon [

40].

A key challenge in the development of bowel preparation regimens is the effectiveness of cleansing the right colon, as its anatomical and physiological characteristics make it more difficult to clean compared to the left colon [

41]. This trend was also observed in our study.

In our study, we achieved adequate bowel cleanliness in 96.3% of patients, with all three regimens achieving at least 95% adequacy. This aligns with the ESGE recommendations, which set the minimum standard for adequately prepared colonoscopies at ≥90%. Furthermore, the minimum ESGE standards for ADR (25%) and PDR (40%) were exceeded across all regimens [

32].

No statistically significant differences were observed between the preparation regimens in terms of BBPS scores, both overall and by individual segments, nor in ADR and PDR for the entire colon and the right colon, which is consistent with findings from certain studies [

42,

43,

44].

On the other hand, three larger studies, contradicted our findings by demonstrating superior overall BBPS and right colon BBPS in the 1L PEG group compared to the 2L PEG group [

19,

20,

21]. Similar results were reported in the CLEANSE study and in the first study conducted on an Asian population [

18,

22]. Additionally, Ariera et al. found that the 1L PEG group achieved a higher overall BBPS and segmental BBPS scores compared to the 2L PEG group. However, after excluding patients with diabetes, the differences in overall BBPS and BBPS for the transverse colon were no longer significant, while the differences for the right and left colon BBPS remained significant [

17].

Similar to BBPS scores, we did not identify any statistically significant differences in PDR, ADR, right colon PDR, right colon ADR, or the mean number of polyps per colonoscopy when comparing the preparation regimens which is similar as in two other studies [

22,

45]. However, a significantly higher PDR in the 1L PEG group was observed in the national Dutch study and the Korean study [

18,

46]. In the MORA research group, it was found that a split-dose 1L PEG regimen was superior to 2L PEG in terms of higher right colon PDR, whereas this difference was not observed with a single-dose 1L PEG regimen [

19].

No statistically significant differences were observed in the frequency or severity of adverse effects among the different bowel preparation regimens. However, certain trends were noted. Thirst was the most frequently reported adverse effect across all three regimens, with the highest prevalence in the Plenvu group. Additionally, nausea was slightly more pronounced in this regimen. Bloating was more frequently reported in the Moviprep + Donat Mg and Plenvu + Donat Mg groups.

Other studies have similarly reported a higher incidence of thirst, nausea, and vomiting with 1L PEG, which has been attributed to the higher osmolality of the preparation [

15,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

47,

48]. To mitigate these adverse effects, it is recommended that Plenvu be adequately chilled, consumed more slowly, and taken with a larger volume of plain water; however, these measures may reduce the efficacy of the preparation [

15,

19,

21].

No significant differences were found in overall patient satisfaction with the bowel preparation regimen. The vast majority of study participants indicated that they would repeat the same preparation regimen if required. This result is notable, as previous studies have reported a lower willingness to repeat bowel preparation with 2L PEG [

17,

44,

45].

A study by Olivier et al. similarly found that over 75% of patients who had experience with both 1L PEG and 2L PEG preferred to repeat bowel preparation with 1L PEG rather than 2L PEG [

49]. Brooks et al. reached similar conclusions. The lower volume of solution required for Plenvu was frequently cited in studies as the primary reason for patient preference and satisfaction [

50].

Our study had several limitations. In addition to age, variability in colonoscopy indications have influenced ADR and PDR. Specific indications for colonoscopy were not recorded in our study; therefore, we cannot exclude variability between groups, which could have impacted PDR and ADR outcomes. This limitation could have been mitigated by including only patients undergoing colonoscopy within the framework of a national colorectal cancer screening program.

Additionally, we lacked data on comorbidities, which could also influence bowel cleansing effectiveness, as demonstrated in the study by Ariera et al. [

17]. Another limitation relates to the BBPS scoring system, which, by definition, assesses bowel cleanliness after additional endoscopic cleansing. MacPhail et al. demonstrated that total BBPS scores increase by 23% following endoscopic cleansing, with the most pronounced increase observed in the right colon [

51]. This finding suggests that BBPS is not an optimal indicator of the intrinsic effectiveness of a bowel preparation regimen. Since endoscopic cleansing is performed at the discretion of the endoscopist, human factors may further influence the results, potentially explaining the discrepancies in findings between different studies.

In our study, we compared the efficacy of two PEG-based preparations; however, to accurately assess regimen effectiveness and determine the potential added value of Donat Mg, an additional control group using Moviprep alone (without Donat Mg) would have been necessary.

5. Conclusions

In our study, none of the investigated bowel preparation regimens demonstrated superiority in terms of bowel cleanliness, PDR, or procedural tolerability. All three regimens achieved a high level of adequate preparation, exceeding the ESGE target standards.

The new low-volume PEG preparations represent a valuable alternative for patients requiring restricted fluid intake, while maintaining comparable efficacy to traditional regimens. Further research is needed to define the most optimal preparation protocols for different patient populations.

Author Contributions

Saša Štupar (Conceptualization: Equal; Investigation: Equal; Methodology: Supporting; Visualization: Lead; Writing: Lead); Borut Štabuc (Conceptualization: Equal; Investigation: Equal; Project administration: Supporting; Supervision: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal); Bojan Tepeš (Conceptualization: Equal; Investigation: Equal; Methodology: Equal); Katja Tepeš (Data curation: Equal); Milan Stefanovič (Conceptualization: Equal; Investigation: Equal; Project administration: Supporting); Sebastjan Stefanovič (Investigation: Equal; Project administration: Equal); Samo Plut (Conceptualization: Equal; Investigation: Supporting; Methodology: Lead; Supervision: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Lead); Conceptualization: Saša Štupar, Borut Štabuc, Bojan Tepeš, Milan Stefanovič, Samo Plut; methodology: Borut Štabuc, Bojan Tepeš, Milan Stefanovič, Samo Plut; software: Saša Štupar, Sebastjan Stefanovič; validation: Borut Štabuc, Bojan Tepeš, Samo Plut; formal analysis: Saša Štupar, Borut Štabuc; investigation: Saša Štupar, Katja Tepeš, Sebastjan Stefanovič; data curation: Saša Štupar, Borut Štabuc; writing—original draft preparation: Saša Štupar; writing—review and editing: Saša Štupar, Borut Štabuc, Samo Plut.; visualization: Saša Štupar; supervision: Samo Plut. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the National Medical Ethics Committee (Number of approval: 0120-456/2022/3).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript the authors used Copilot for the purposes of language editing and grammatical improvement. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PEG |

Polyethylene glycol |

| BBPS |

Boston Bowel Preparation Scale |

| PDR |

Polyp Detection Rate |

| ADR |

Adenoma Detection Rate |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

References

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229-263.

- Hassan C, Bretthauer M, Kaminski MF, et al. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy 2013;45:142-150.

- Sulz MC, Kroger A, Prakash M, et al. Meta-analysis of the effect of bowel preparation on adenoma detection: early adenomas affected stronger than advanced adenomas. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0154149.

- Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, et al. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61(3):378–84.

- Adler A, Wegscheider K, Lieberman D, et al. Factors determining the quality of screening colonoscopy: a prospective study on adenoma detection rates, from 12,134 examinations (Berlin colonoscopy project 3, BECOP-3). Gut. 2013;62(2):236–41.

- Lebwohl B, Kastrinos F, Glick M, et al. The impact of suboptimal bowel preparation on adenoma miss rates and the factors associated with early repeat colonoscopy. Gastro intest Endosc. 2011;73(6):1207–14.

- Xie Q, Chen L, Zhao F, et al. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of low-volume polyethylene glycol plus ascorbic acid versus standard-volume polyethylene glycol solution as bowel preparations for colonoscopy. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99092.

- Ell C, Fischbach W, Bronisch H, et al. Randomized trial of low volume PEG solution versus standard PEG+ electrolytes for bowel cleansing before colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:883–93.

- Ponchon T, Boustière C, Heresbach D, et al. A low-volume polyethylene glycol plus ascorbate solution for bowel cleansing prior to colonoscopy: the NORMO randomised clinical trial. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45(10):820-6.

- Marmo R, Rotondano G, Riccio G, et al. Effective bowel cleansing before colonoscopy: a randomized study of split-dosage versus non-split dosage regimens of high-volume versus low-volume polyethylene glycol solutions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72(2):313-20.

- Corporaal S, Kleibeuker JH, Koornstra JJ. Low-volume PEG plus ascorbic acid versus high-volume PEG as bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45(11):1380-6.

- Clark RE, Godfrey JD, Choudhary A, et al. Low-volume polyethylene glycol and bisacodyl for bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy: a meta-analysis. Ann Gastroenterol. 2013;26(4):319-324.

- Available online: http://www.cbz.si/.

- DeMicco MP, Clayton LB, Pilot J, et al; NOCT Study Group. Novel 1 L polyethylene glycol-based bowel preparation NER1006 for overall and right-sided colon cleansing: a randomized controlled phase 3 trial versus trisulfate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018 Mar;87(3):677-687.e3.

- Schreiber S, Baumgart DC, Drenth JP, et al. Colon cleansing efficacy and safety with 1 L NER1006 versus sodium picosulfate with magnesium citrate: a randomized phase 3 trial. Endoscopy 2019;51(1):73-84.

- Worthington J, Thyssen M, Chapman G, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a new 2 litre polyethylene glycol solution versus sodium pico sulphate + magnesium citrate solution for bowel cleansing prior to colonoscopy. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:481–488.

- Arieira C, Dias de Castro F, Boal Carvalho P, et al. Bowel cleansing efficacy for colonoscopy: prospective, randomized comparative study of same-day dosing with 1-L and 2-L PEG + ascorbate. Endosc Int Open. 2021;9(11):E1602-E1610.

- Hong SN, Lee CK, Im JP, et al. Efficacy and safety of split-dose bowel preparation with 1 L polyethylene glycol and ascorbate compared with 2 L polyethylene glycol and ascorbate in a Korean population: a phase IV, multicenter, randomized, endoscopist-blinded study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95(3):500-511.e2.

- Bisschops R, Manning J, Clayton LB, et al. Colon cleansing efficacy and safety with 1 L NER1006 versus 2. L polyethylene glycol plus ascorbate: a randomized phase 3 trial. Endoscopy 2018;51(1):60-72.

- Maida M, Sinagra E, Morreale GC, et al. Effectiveness of very low-volume preparation for colonoscopy: A prospective, multicenter observational study. World J Gastroenterol. 202028;26(16):1950-1961.

- Bednarska O, Nyhlin N, Schmidt PT, et al. The Effectiveness and Tolerability of a Very Low-Volume Bowel Preparation for Colonoscopy Compared to Low and High-Volume Polyethylene Glycol-Solutions in the Real-Life Setting. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12(5):1155.

- Ahmad A, Marshall S, Bassett P, et al. Evaluation of bowel preparation regimens for colonoscopy including a novel low volume regimen (Plenvu): CLEANSE study. BMJ Open Gastro 2023;10:e001070.

- Choi SH, Yoon WE, Kim SH, et al. Comparison of Two Types of 1-L Polyethylene Glycol-ascorbic Acid as Colonoscopic Bowel Preparation: A Prospective Randomized Study. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2022;80(2):85-92.

- Tepeš B, Mlakar DN, Metličar T. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy with magnesium sulphate and low-volume polyethylene glycol. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26(6):616-20.

- Bothe G, Coh A, Auinger A. Efficacy and safety of a natural mineral water rich in magnesium and sulphate for bowel function: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Eur J Nutr. 2017;56(2):491-499.

- Choi SJ, Kim ES, Choi BK, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of 1-L polyethylene glycol solution with ascorbic acid plus prucalopride versus 2-L polyethylene glycol solution with ascorbic acid for bowel preparation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(12):1619-1624.

- Tangvoraphonkchai K, Manasirisuk W, Sawadpanich K, et al. Lubiprostone plus polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution (PEG-ELS) versus PEG-ELS for bowel preparation in chronic constipation: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):16265.

- Soh JS, Kim KJ. Combination could be another tool for bowel preparation? World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(10):2915-21.

- Banerjee R, Chaudhari H, Shah N, et al. Addition of Lubiprostone to polyethylene glycol(PEG) enhances the quality & efficacy of colonoscopy preparation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16(1):133.

- Calderwood AH, Jacobson BC. Comprehensive validation of the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72(4):686-92.

- Guo R, Wang YJ, Liu M, et al. The effect of quality of segmental bowel preparation on adenoma detection rate. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19(1):119.

- Kaminski MF, Thomas-Gibson S, Bugajski M, et al. Performance measures for lower gastrointestinal endoscopy: a European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Quality Improvement Initiative. Endoscopy. 2017;49(4):378-397.

- Bretthauer M, Loberg M, Wieszczy P, et al. Effect of colonoscopy screening on risks of colorectal cancer and related death. New Engl J Med 2022;387:1547–1556.

- Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, et al. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: Recommenda tions from the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2014;147:903–924.

- Clark, BT, Protiva P, Nagar A, et al. Quantification of Adequate Bowel Preparation for Screening or Surveillance Colonoscopy in Men. Gastroenterology 2016;150:396–405.

- Lasisi F, Rex DK. Improving protection against proximal colon Cancer by colonoscopy. Expert Rev Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011;5:745–754.

- Clark BT, Laine L. High-quality bowel preparation is required for detection of sessile serrated polyps. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:1155–1162.

- Xiang L, Zhan Q, Zhao XH, et al. Risk factors associated with missed colorectal flat adenoma: a multicenter retrospective tandem colo noscopy study. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:10927–10937.

- Sawhney MS, Dickstein J, LeClair J, et al. Adenomas with high-grade dysplasia and early adenocarcinoma are more likely to be sessile in the proximal colon. Colorectal Dis 2015;17:682–688.

- Singh S, Singh PP, Murad MH, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of interval colorectal cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1375–1389.

- Pohl J, Halphen M, Kloess HR, et al. Impact of the quality of bowel cleansing on the efficacy of colonic cancer screening: A prospective, randomized, blinded study. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0126067.

- Kang SH, Jeen YT, Lee JH, et al. Comparison of a split-dose bowel preparation with 2 liters of polyethylene glycol plus ascorbic acid and 1 liter of polyethylene glycol plus ascorbic acid and bisacodyl before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86(2):343-348.

- Kim SH, Kim JH, Keum B, et al. A Randomized, Endoscopist-Blinded, Prospective Trial to Randomized, Endoscopist-Blinded, Prospective Trial to Compare the Efficacy and Patient Tolerability between Bowel Preparation Protocols Using Sodium Picosulfate Magnesium Citrate and Polyethylene-Glycol (1 L and 2 L) for Colonoscopy. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020;2020:9548171.

- Kwon JE, Lee JW, Im JP, et al. Comparable Efficacy of a 1-L PEG and Ascorbic Acid Solution Administered with Bisacodyl versus a 2-L PEG and Ascorbic Acid Solution for Colonoscopy Preparation: A Prospective, Randomized and Investigator-Blinded Trial. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0162051.

- Kamei M, Shibuya T, Takahashi M, et al. Efficacy and Acceptability of 1 Liter of Polyethylene Glycol with Ascorbic Acid vs. 2 Liters of Polyethylene Glycol Plus Mosapride and Sennoside for Colonoscopy Preparation. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:523-530.

- Theunissen F, Lantinga MA, Ter Borg PCJ, et al. Efficacy of different bowel preparation regimen volumes for colorectal cancer screening and compliance with European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy performance measures. United European Gastroenterol J. 2023;11(5):448-457.

- Jeon HJ, Keum B, Bang EJ, et al. Bowel Preparation Efficacy and Safety of 1 L vs 2 L Polyethylene Glycol With Ascorbic Acid for Colonoscopy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2023;14(3):e00532.

- Maida M, Macaluso FS, Sferrazza S, et al. Effectiveness and safety of NER1006 versus standard bowel preparations: A meta-analysis of randomized phase-3 clinical trials. Dig. Liver Dis. 2020; 52: 833–839.

- Oliveira A, Mascarenhas-Saraiva M. Tolerance and efficiency of a novel low-volume PEG + Ascorbate (NER1006) preparation in the elderly: A real-life single center study. Endoscopy 2019;51:25.

- Cash BD, Moncrief MBC, Epstein MS, et al. Patient experience with NER1006 as a bowel preparation for colonoscopy: a prospective, multicenter US survey. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21(1):70.

- MacPhail ME, Hardacker KA, Tiwari A, et al. Intraprocedural cleansing work during colonoscopy and achievable rates of adequate preparation in an open-access endoscopy unit. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81(3):525-30.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).