Submitted:

22 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Properties and Limitations of PBS and Chitosan

- Poly(butylene succinate) (PBS)

- Chitosan (CS)

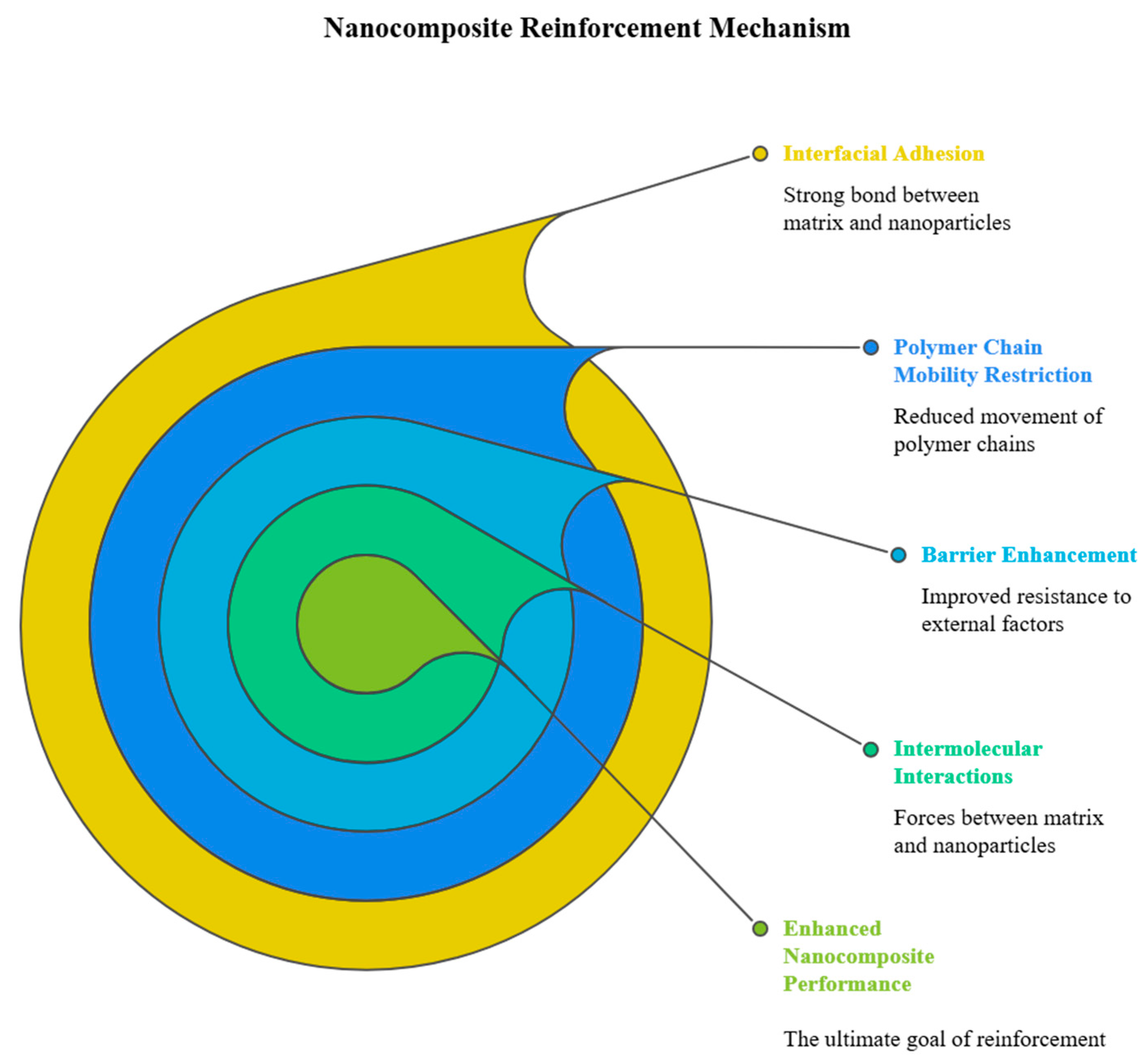

- Structure–Property Relationships

- Mechanical Properties

- Thermal Behavior

- Barrier and Surface Properties

- Biodegradation Behavior

- Applications

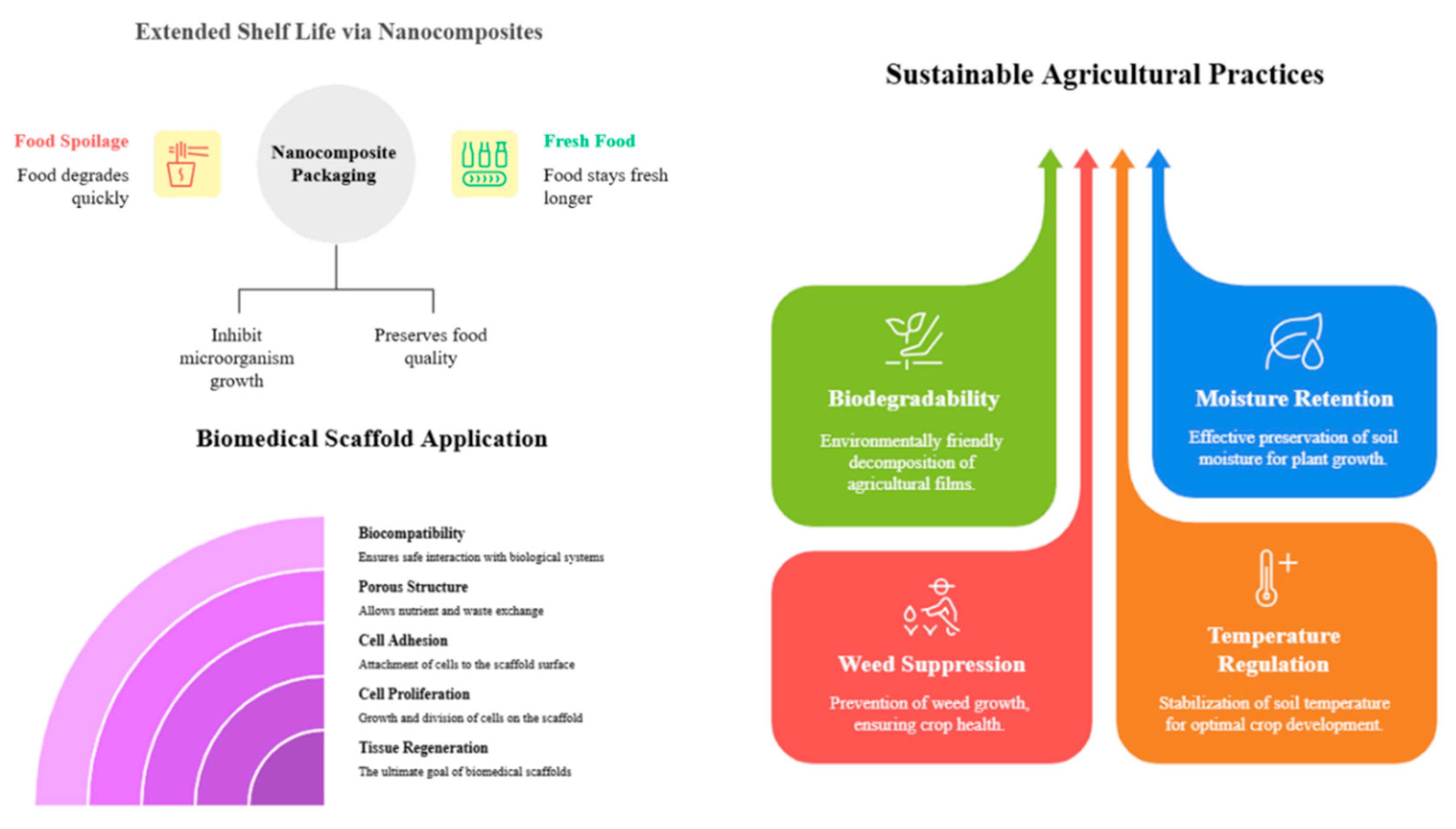

- Packaging Applications

- Biomedical Applications

- Agricultural Applications

- Other Emerging Applications

- Environmental and Economic Considerations

- Environmental Sustainability and Life-Cycle Assessment

- Biodegradation Pathways and Environmental Compatibility

- Economic Feasibility and Industrial Challenges

- Sustainability Trade-Offs and Future Prospects

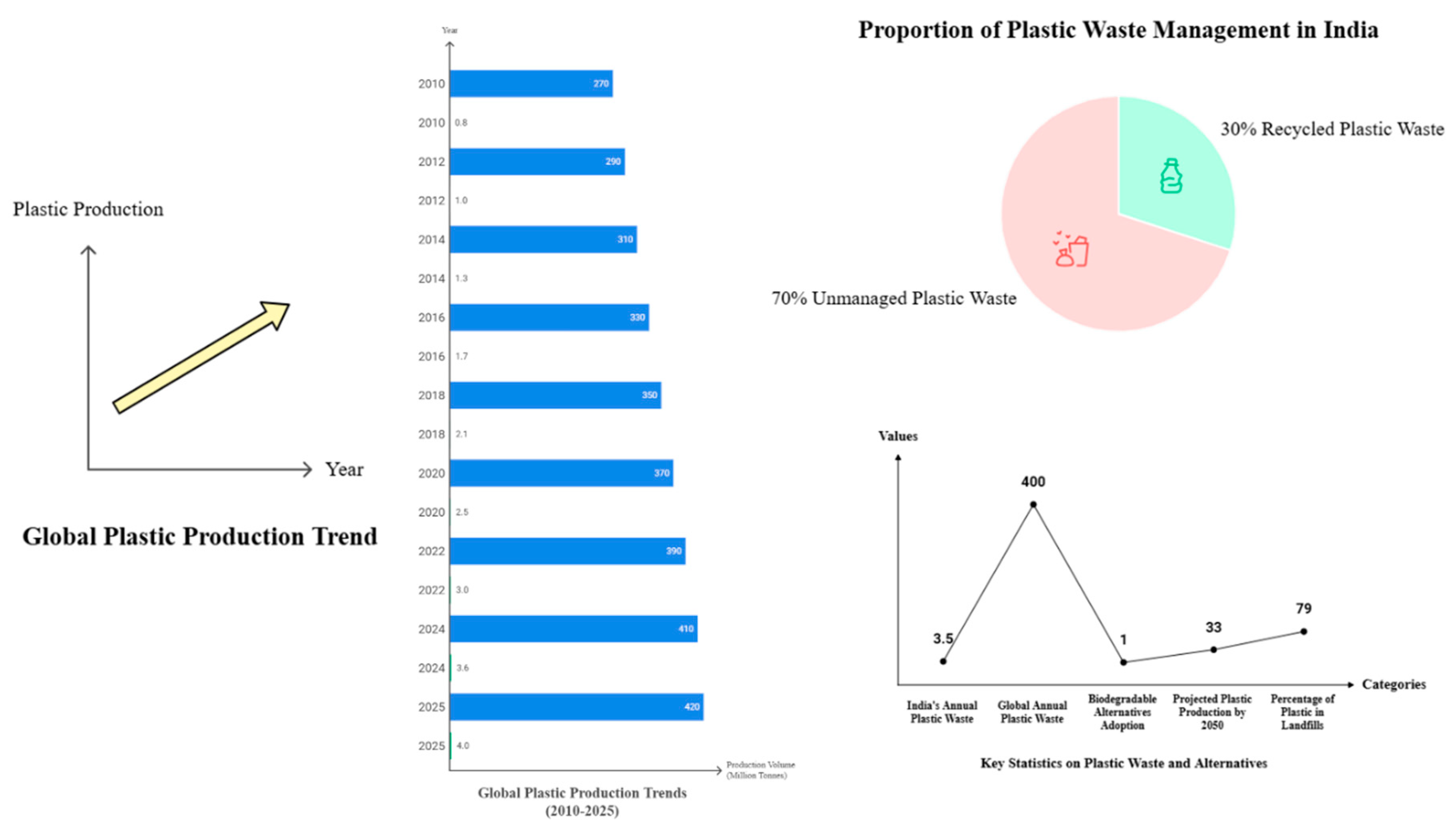

- Current Status in India

- Sustainable / Biodegradable Plastic Recycling and Alternative Applications in India

- Textile and Fabric Applications

- Road and Construction Applications

- Agricultural and Household Alternatives

- Summary of Reported Works on PBS/Chitosan Bio-Nanocomposites

Future Directions

- Molecular Design and Tailored Functionalization

- Integration of Multi-Scale Bio-Based Nanoparticles

- Green and Scalable Processing Technologies

- Life-Cycle Assessment and End-of-Life Strategies

- Functional Applications and Smart Composites

- Circular Economy and Industrial Implementation

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. A. Fayshal, “Current practices of plastic waste management, environmental impacts, and potential alternatives for reducing pollution and improving management,” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 23, p. e40838, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Singh and T. R. Walker, “Plastic recycling: A panacea or environmental pollution problem,” npj Mater. Sustain., vol. 2, no. 1, p. 17, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Kalauni, A. Vedrtnam, S. P. Sharma, A. Sharma, and S. Chaturvedi, “A comprehensive review of recycling and reusing methods for plastic waste focusing Indian scenario,” Waste Manag Res, vol. 43, no. 9, pp. 1378–1399, Sep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, A. K. Awasthi, F. Wei, Q. Tan, and J. Li, “Single-use plastics: Production, usage, disposal, and adverse impacts,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 752, p. 141772, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xie, S. Gao, D. Zhang, C. Wang, and F. Chu, “Bio-based polymeric materials synthesized from renewable resources: A mini-review,” Resources Chemicals and Materials, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 223–230, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Barletta et al., “Poly(butylene succinate) (PBS): Materials, processing, and industrial applications,” Progress in Polymer Science, vol. 132, p. 101579, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Harugade, A. P. Sherje, and A. Pethe, “Chitosan: A review on properties, biological activities and recent progress in biomedical applications,” Reactive and Functional Polymers, vol. 191, p. 105634, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Ramesh, M. Tamil Selvan, and A. Saravanakumar, “Evolution and recent advancements of composite materials in structural applications,” in Applications of Composite Materials in Engineering, Elsevier, 2025, pp. 97–117. [CrossRef]

- S. Sharma et al., “Polymeric nanocomposites: Recent advances, challenges, techniques, and biomedical applications,” Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises, vol. 83, no. 6, pp. 1019–1039, Nov. 2025. [CrossRef]

- V. Lunetto, M. Galati, L. Settineri, and L. Iuliano, “Sustainability in the manufacturing of composite materials: A literature review and directions for future research,” Journal of Manufacturing Processes, vol. 85, pp. 858–874, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Barletta et al., “Poly(butylene succinate) (PBS): Materials, processing, and industrial applications,” Progress in Polymer Science, vol. 132, p. 101579, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Aliotta, M. Seggiani, A. Lazzeri, V. Gigante, and P. Cinelli, “A Brief Review of Poly (Butylene Succinate) (PBS) and Its Main Copolymers: Synthesis, Blends, Composites, Biodegradability, and Applications,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 4, p. 844, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Dmitruk, J. Ludwiczak, M. Skwarski, P. Makuła, and P. Kaczyński, “Influence of PBS, PBAT and TPS content on tensile and processing properties of PLA-based polymeric blends at different temperatures,” J Mater Sci, vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 1991–2004, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Su, R. Kopitzky, S. Tolga, and S. Kabasci, “Polylactide (PLA) and Its Blends with Poly(butylene succinate) (PBS): A Brief Review,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 11, no. 7, p. 1193, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Hisham, M. H. Maziati Akmal, F. Ahmad, K. Ahmad, and N. Samat, “Biopolymer chitosan: Potential sources, extraction methods, and emerging applications,” Ain Shams Engineering Journal, vol. 15, no. 2, p. 102424, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. El Knidri, R. Belaabed, A. Addaou, A. Laajeb, and A. Lahsini, “Extraction, chemical modification and characterization of chitin and chitosan,” International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, vol. 120, pp. 1181–1189, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Biswal and S. K. Swain, “Chitosan: A Smart Biomaterial,” in Chitosan Nanocomposites, S. K. Swain and A. Biswal, Eds., in Biological and Medical Physics, Biomedical Engineering., Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2023, pp. 1–25. [CrossRef]

- R. Priyadarshi and J.-W. Rhim, “Chitosan-based biodegradable functional films for food packaging applications,” Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, vol. 62, p. 102346, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Fiallos-Núñez et al., “Eco-Friendly Design of Chitosan-Based Films with Biodegradable Properties as an Alternative to Low-Density Polyethylene Packaging,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 16, no. 17, p. 2471, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Merijs-Meri et al., “Melt-Processed Polybutylene-Succinate Biocomposites with Chitosan: Development and Characterization of Rheological, Thermal, Mechanical and Antimicrobial Properties,” Polymers, vol. 16, no. 19, p. 2808, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. J. Bailey and K. I. Winey, “Dynamics of polymer segments, polymer chains, and nanoparticles in polymer nanocomposite melts: A review,” Progress in Polymer Science, vol. 105, p. 101242, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Kim et al., “Highly reinforced poly(butylene succinate) nanocomposites prepared from chitosan nanowhiskers by in-situ polymerization,” International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, vol. 173, pp. 128–135, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Monika, A. K. Pal, S. M. Bhasney, P. Bhagabati, and V. Katiyar, “Effect of Dicumyl Peroxide on a Poly(lactic acid) (PLA)/Poly(butylene succinate) (PBS)/Functionalized Chitosan-Based Nanobiocomposite for Packaging: A Reactive Extrusion Study,” ACS Omega, vol. 3, no. 10, pp. 13298–13312, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B.-M. Tofanica, A. Mikhailidi, M. E. Fortună, R. Rotaru, O. C. Ungureanu, and E. Ungureanu, “Cellulose Nanomaterials: Characterization Methods, Isolation Techniques, and Strategies,” Crystals, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 352, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhao et al., “Thermal, crystallization, and mechanical properties of polylactic acid (PLA)/poly(butylene succinate) (PBS) blends,” Polym. Bull., vol. 81, no. 3, pp. 2481–2504, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhao et al., “Thermal, crystallization, and mechanical properties of polylactic acid (PLA)/poly(butylene succinate) (PBS) blends,” Polym. Bull., vol. 81, no. 3, pp. 2481–2504, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Qi, J. Wu, J. Chen, and H. Wang, “An investigation of the thermal and (bio)degradability of PBS copolyesters based on isosorbide,” Polymer Degradation and Stability, vol. 160, pp. 229–241, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Chandarana, S. Bonde, S. Sonwane, and B. Prajapati, “Chitosan-based packaging: leading sustainable advancements in the food industry,” Polym. Bull., vol. 82, no. 11, pp. 5431–5462, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- W. Cui and L. Xiang, Natural Polymers for Biomedical Applications, 1st ed. Wiley, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Yanat and K. Schroën, “Preparation methods and applications of chitosan nanoparticles; with an outlook toward reinforcement of biodegradable packaging,” Reactive and Functional Polymers, vol. 161, p. 104849, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Yu, D. Wang, N. Geetha, K. M. Khawar, S. Jogaiah, and M. Mujtaba, “Current trends and challenges in the synthesis and applications of chitosan-based nanocomposites for plants: A review,” Carbohydrate Polymers, vol. 261, p. 117904, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. U. Arif, M. Y. Khalid, M. F. Sheikh, A. Zolfagharian, and M. Bodaghi, “Biopolymeric sustainable materials and their emerging applications,” Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, vol. 10, no. 4, p. 108159, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Andrew and H. N. Dhakal, “Sustainable biobased composites for advanced applications: recent trends and future opportunities – A critical review,” Composites Part C: Open Access, vol. 7, p. 100220, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Khandeparkar, R. Paul, A. Sridhar, V. V. Lakshmaiah, and P. Nagella, “Eco-friendly innovations in food packaging: A sustainable revolution,” Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy, vol. 39, p. 101579, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Palmieri, J. N. A. Tagoe, and L. Di Maio, “Development of PBS/Nano Composite PHB-Based Multilayer Blown Films with Enhanced Properties for Food Packaging Applications,” Materials (Basel), vol. 17, no. 12, p. 2894, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Sun, K. Zhang, and J. Wang, “Development of PEG-coated MgO NPs/chitosan hybrid nanocomposite loaded with ciprofloxacin drug for synergistic bacterial sepsis treatment: In vitro antibacterial and biocompatibility studies,” Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, vol. 114, p. 107461, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Su et al., “Hemostatic and antimicrobial properties of chitosan-based wound healing dressings: A review,” International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, vol. 306, p. 141570, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Mohammadalipour, F. Alihosseini, E. B. Toloue, S. Karbasi, and Z. Mohammadalipour, “Evaluation of PHB-chitosan/CNC scaffolds’ applicability for bone tissue engineering via MG-63 osteoblastic cell cultivation and osteogenic markers gene expression,” International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, vol. 320, p. 146041, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Jiffrin et al., “Electrospun Nanofiber Composites for Drug Delivery: A Review on Current Progresses,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 18, p. 3725, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Hofmann et al., “Plastics can be used more sustainably in agriculture,” Commun Earth Environ, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 332, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. G. Hayes et al., “Biodegradable Plastic Mulch Films for Sustainable Specialty Crop Production,” in Polymers for Agri-Food Applications, T. J. Gutiérrez, Ed., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019, pp. 183–213. [CrossRef]

- “Use of plastic mulch in agriculture and strategies to mitigate the associated environmental concerns,” in Advances in Agronomy, vol. 164, Elsevier, 2020, pp. 231–287. [CrossRef]

- G. Chen et al., “Replacing Traditional Plastics with Biodegradable Plastics: Impact on Carbon Emissions,” Engineering, vol. 32, pp. 152–162, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Riseh, M. Hassanisaadi, M. Vatankhah, S. A. Babaki, and E. A. Barka, “Chitosan as a potential natural compound to manage plant diseases,” International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, vol. 220, pp. 998–1009, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou et al., “Recent advances and perspectives in functional chitosan-based composites for environmental remediation, energy, and biomedical applications,” Progress in Materials Science, vol. 152, p. 101460, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. D. Souza et al., “Impact of Cationic and Neutral Clay Minerals’ Incorporation in Chitosan and Chitosan/PVA Microsphere Properties,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 17, no. 14, pp. 21189–21205, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. Rosova et al., “Biocomposite Materials Based on Chitosan and Lignin: Preparation and Characterization,” Cosmetics, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 24, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Rajendran et al., “Replacement of Petroleum Based Products With Plant-Based Materials, Green and Sustainable Energy—A Review,” Engineering Reports, vol. 7, no. 4, p. e70108, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. Kaynak, I. S. Piri, and O. Das, “Revisiting the Basics of Life Cycle Assessment and Lifecycle Thinking,” Sustainability, vol. 17, no. 16, p. 7444, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- F. Patwary, N. Matsko, and V. Mittal, “Biodegradation properties of melt processed PBS /chitosan bio-nanocomposites with silica, silicate, and thermally reduced graphene,” Polymer Composites, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 386–397, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Wang, H. Yi, and M. Zheng, “The green synthetic approach to prepare PbS/chitosan nanocomposites and its new optical sensing active properties for 2-isonaphthol,” Polym. Sci. Ser. B, vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 474–478, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. Nath, M. Misra, F. Al-Daoud, and A. K. Mohanty, “Studies on poly(butylene succinate) and poly(butylene succinate- co -adipate)-based biodegradable plastics for sustainable flexible packaging and agricultural applications: a comprehensive review,” RSC Sustainability, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 1267–1302, 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. Baca, R. Monroy, M. Castillo, A. Elkhazraji, A. Farooq, and R. Ahmad, “Dioxins and plastic waste: A scientometric analysis and systematic literature review of the detection methods,” Environmental Advances, vol. 13, p. 100439, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Kim et al., “Comparative degradation behavior of polybutylene succinate (PBS), used PBS, and PBS/Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) blend fibers in compost and marine–sediment interfaces,” Sustainable Materials and Technologies, vol. 41, p. e01065, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. F. Alias and K. I. K. Marsilla, “Processes and characterization for biobased polymers from polybutylene succinate,” in Processing and Development of Polysaccharide-Based Biopolymers for Packaging Applications, Elsevier, 2020, pp. 151–170. [CrossRef]

- A. P. Khedulkar et al., “Bio-based nanomaterials as effective, friendly solutions and their applications for protecting water, soil, and air,” Materials Today Chemistry, vol. 46, p. 102688, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Riofrio, T. Alcivar, and H. Baykara, “Environmental and Economic Viability of Chitosan Production in Guayas-Ecuador: A Robust Investment and Life Cycle Analysis,” ACS Omega, vol. 6, no. 36, pp. 23038–23051, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. Issahaku, I. K. Tetteh, and A. Y. Tetteh, “Chitosan and chitosan derivatives: Recent advancements in production and applications in environmental remediation,” Environmental Advances, vol. 11, p. 100351, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Huang, Q. Dong, S. Che, R. Li, and K. H. D. Tang, “Bioplastics and biodegradable plastics: A review of recent advances, feasibility and cleaner production,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 969, p. 178911, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu et al., “Breaking the nanoparticle’s dispersible limit via rotatable surface ligands,” Nat Commun, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 3581, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Tanveer, S. A. R. Khan, M. Umar, Z. Yu, M. J. Sajid, and I. U. Haq, “Waste management and green technology: future trends in circular economy leading towards environmental sustainability,” Environ Sci Pollut Res Int, vol. 29, no. 53, pp. 80161–80178, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Nøklebye, H. N. Adam, A. Roy-Basu, G. K. Bharat, and E. H. Steindal, “Plastic bans in India – Addressing the socio-economic and environmental complexities,” Environmental Science & Policy, vol. 139, pp. 219–227, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Barone et al., “Rethinking single-use plastics: Innovations, polices, consumer awareness and market shaping biodegradable solutions in the packaging industry,” Trends in Food Science & Technology, vol. 158, p. 104906, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- P. Singh, V. K. Pandey, R. Singh, K. Singh, K. K. Dash, and S. Malik, “Unveiling the potential of starch-blended biodegradable polymers for substantializing the eco-friendly innovations,” Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, vol. 15, p. 101065, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Stroescu, A. R. Marc, and C. C. Mureșan, “A Comprehensive Review on Sugarcane Bagasse in Food Packaging: Properties, Applications, and Future Prospects,” HPM, vol. 32, no. 1–2, pp. 169–184, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Kovacs and M. Garai-Fodor, “Compostable Bag Project- Possible Marketing Strategies for Applying Microplastic-Free Packaging in Practice,” in Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Lifelong Education and Leadership for ALL (ICLEL 2024), vol. 34, C. F. De Sousa Reis, M. Fodor-Garai, and O. Titrek, Eds., in Atlantis Highlights in Social Sciences, Education and Humanities, vol. 34. , Dordrecht: Atlantis Press International BV, 2025, pp. 742–761. [CrossRef]

- K. Samneingjam, J. Mahajaroensiri, M. Kanathananun, C. V. Aranda, M. Muñoz, and S. Limwongsaree, “Enhancing Polypropylene Biodegradability Through Additive Integration for Sustainable and Reusable Laboratory Applications,” Polymers, vol. 17, no. 5, p. 639, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- N. Khan, K. Sudhakar, and R. Mamat, “Bio-based papers from seaweed and coconut fiber: sustainable materials for a greener future,” Carbon Resources Conversion, vol. 8, no. 4, p. 100329, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Rajbongshi, A. Saikumar, and L. S. Badwaik, “Valorization of areca nut husk and water hyacinth fibers into biodegradable plates for sustainable packaging,” Sustainable Food Technol., p. 10.1039.D5FB00319A, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Huang, Q. Dong, S. Che, R. Li, and K. H. D. Tang, “Bioplastics and biodegradable plastics: A review of recent advances, feasibility and cleaner production,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 969, p. 178911, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Lee, D. Lee, J. Lee, and Y.-K. Park, “Current methods for plastic waste recycling: Challenges and opportunities,” Chemosphere, vol. 370, p. 143978, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Shanker et al., “Plastic waste recycling: existing Indian scenario and future opportunities,” Int J Environ Sci Technol (Tehran), vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 5895–5912, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Enking et al., “Recycling processes of polyester-containing textile waste–A review,” Resources, Conservation and Recycling, vol. 219, p. 108256, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ma et al., “The utilization of waste plastics in asphalt pavements: A review,” Cleaner Materials, vol. 2, p. 100031, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Agyeman, N. K. Obeng-Ahenkora, S. Assiamah, and G. Twumasi, “Exploiting recycled plastic waste as an alternative binder for paving blocks production,” Case Studies in Construction Materials, vol. 11, p. e00246, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Hofmann et al., “Plastics can be used more sustainably in agriculture,” Commun Earth Environ, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 332, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Kim et al., “Highly reinforced poly(butylene succinate) nanocomposites prepared from chitosan nanowhiskers by in-situ polymerization,” International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, vol. 173, pp. 128–135, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Kim et al., “Trans crystallization behavior and strong reinforcement effect of cellulose nanocrystals on reinforced poly(butylene succinate) nanocomposites,” RSC Adv., vol. 8, no. 28, pp. 15389–15398, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. C. M. Fernandes et al., “Novel transparent nanocomposite films based on chitosan and bacterial cellulose,” Green Chem., vol. 11, no. 12, p. 2023, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Y.-P. Zhang et al., “Preparation and Characterization of Bio-Nanocomposites Film of Chitosan and Montmorillonite Incorporated with Ginger Essential Oil and Its Application in Chilled Beef Preservation,” Antibiotics, vol. 10, no. 7, p. 796, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

| Material / Product Type | Material Basis | Typical Applications | Key Challenges / Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starch-/vegetable-oil-derived compostable films & bags | Corn starch, tapioca starch, PVOH blends (e.g., GreenPlast) | Carry-bags, grocery/vegetable bags, waste bags | Production cost still higher than PE/PP; claims of biodegradability need verification; scale and supply of feedstock. | [64] |

| Compostable bioplastic-based packaging & cutlery | Plant based (sugarcane bagasse, etc) (e.g., Naturoplast) | Disposable plates, cutlery, hot-food pouches | Heat-resistance, barrier properties may lag; cost premium; certification standards. | [65] |

| Bio-bags / compostable garbage bags | Corn/vegetable starch blends (e.g., Ecolastic) | Municipal waste bags, courier bags, plant-grow bags | Composting infrastructure in India still limited; real end-of-life conditions vary. | [66] |

| Additive-modified conventional plastics (oxo-/oxo-bio) | d2w additive technology used with PE/PP (e.g., by Symphony Environmental Technologies in India) | Flexible films, carrier bags, woven sacks, thin-walled containers | Despite claims, regulatory & certification issues; biodegradability in natural environment uncertain; ‘oxo’ plastics may fragment into microplastics. | [67] |

| Novel bio-films/seaweed-based materials | Seaweed-derived films (Indian startup) | Transparent films for packaging | Early stage; scalability, cost, durability under Indian conditions need work. | [68] |

| Areca palm-leaf, bagasse, plate/utensils alternatives (not strictly plastics) | Natural fibre plates, bowls | Disposable tableware replacing plastic plates | May not match all functional needs (strength, moisture resistance); supply chain & cost factors. | [69] |

| Recycled / Sustainable Product | Material Source / Feedstock | End-use Application | Sustainability Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mosquito nets & textiles | Recycled PET bottles (polyester fibers) | Health-sector mosquito nets, clothing, ropes | Diverts plastic waste; durable; supports WHO vector control programs |

| Plastic-modified bitumen | Waste PE, PP, PS blended with bitumen | Road construction | Improves pavement life; reduces plastic waste disposal |

| Bio-composite boards | Recycled plastics + agro-fibers (coir, husk) + PLA/PBS blends | Furniture, panels, construction boards | Partial biodegradability; value addition to agro-waste |

| Agricultural films & pots | Biodegradable PBS/starch blends or recycled PE/PLA | Mulch films, nursery pots, irrigation components | Reduces plastic pollution in soil; compostable after use |

| Recycled household products | Post-consumer HDPE, PET | Containers, planters, benches, chairs | Reduces landfill load; promotes reuse economy |

| Nonwoven geotextiles | Recycled polypropylene fibers | Road underlay, erosion control | Long life; replaces virgin polymer textiles |

| Seaweed- or algae-based films | Marine biomass | Edible packaging, compostable wraps | Fully biodegradable; marine-safe innovation |

| Authors & Year | Title of Work | Nanoparticle / Bio-Filler | Matrix & Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al. | Highly reinforced poly(butylene succinate) nanocomposites prepared from chitosan nanowhiskers by in-situ polymerization | Chitosan nanowhiskers (CsWs) | PBS matrix; improved mechanical strength/toughness; biodegradable plastic substitute | [77] |

| Kim T et al. | Trans crystallization behavior and strong reinforcement effect of cellulose nanocrystals on reinforced poly(butylene succinate) nanocomposites | Cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) | PBS matrix; enhanced crystallisation and mechanical performance | [78] |

| Kusmono et al. | Fabrication and Characterization of Chitosan/Cellulose Nanocrystal/Glycerol Bio-Composite Films | Cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) + glycerol | Chitosan matrix; bio-composite film (food packaging context) | [78] |

| Fernandes et al. | Novel transparent nanocomposite films based on chitosan and bacterial cellulose | Bacterial cellulose nanofibrils | Chitosan matrix; transparent film with improved mechanical & barrier properties | [79] |

| Zhang et al | Preparation and Characterization of Bio-Nanocomposite Film of Chitosan and Montmorillonite Incorporated with Ginger Essential Oil and Its Application in Chilled Beef Preservation | Montmorillonite (as nanoplatelet) + ginger essential oil | Chitosan matrix; food packaging application (chilled beef preservation) | [80] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).