1. Introduction

Brown spot needle blight (BSNB) caused by an ascomycete foliar pathogen

Lecanosticta acicola (Thüm.) Syd. is one of the serious emerging threats for pines in Europe [

1]. The pathogen completes its lifecycle on needles resulting in their necrosis and premature loss. Potentially, severe defoliation may lead to stunted development of young trees and reduced growth. Tree mortality due to

L. acicola infections has been reported multiple times for several pine species [see [

1], and literature cited therein]. The disease has been known since at least the late 19th century from south-eastern USA [

2], and from early 20th century onwards it was recognized as a serious threat to native pines in the region [

3,

4].

Since then, the pathogen spread to numerous locations worldwide causing varying levels of damage. In short, the current range of

L. acicola includes Europe, Eastern North America, Central America (including Columbia), and east Asia. The current disease reports can be readily tracked using a dedicated geo-database (established originally for

Dothistroma spp. and

Fusarium circinatum) available at

https://www.portalofforestpathology.com [

1,

5,

6]. Despite including some older unverified data, the database is the most comprehensive up-to-date source for

L. acicola occurrence currently available.

The first reliable record of BSNB in Europe is from

P. radiata in Spain and dates back to 1940s [

7]. For several decades relatively slow expansion of the pathogen was observed on the continent resulting in new disease reports from Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, and Croatia (then part of Yugoslavia) [see [

1], and literature cited therein]. The situation changed, however, during the last two decades when numerous new BSNB outbreaks occurred throughout the continent resulting in the pathogen being present in 24 European countries [

1].

The pathogen itself originates from North / Central America where numerous

Lecanosticta species occur [

1,

8]. Of these

L. acicola is the most widespread and the only one occurring outside North / Central America. It is a genetically diverse species encompassing three main lineages described based on variety of genetic data [

8,

9,

10]. Two of the lineages, that is northern lineage (originally from eastern USA and Canada) and southern lineage (originally from southern USA), are present in Europe. Thus, the results of genetic analyses show that the current occurrence of

L. acicola in Europe is a result of multiple independent introduction events [

9,

10].

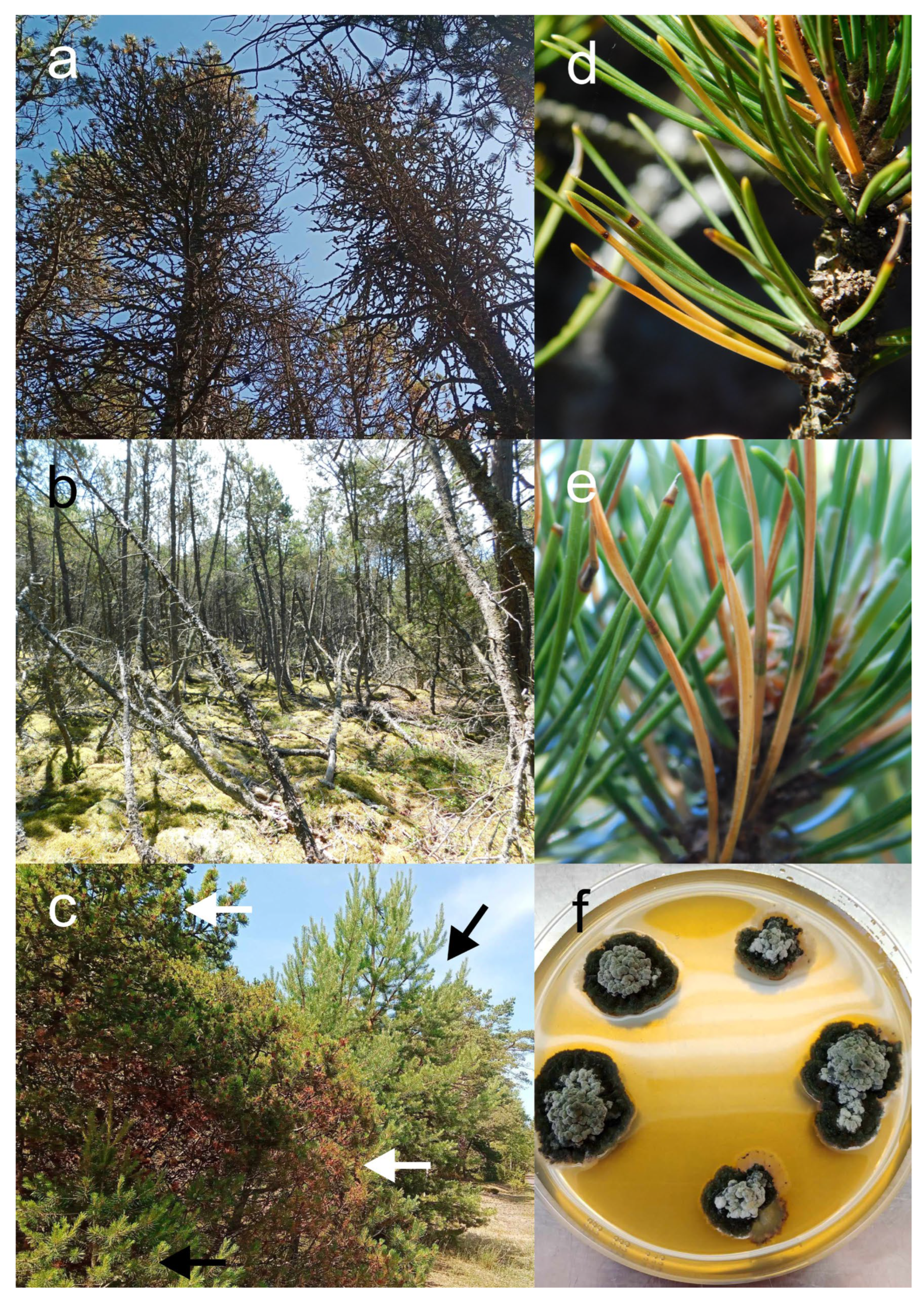

Typical BSNB symptoms start with development of yellow, sometimes light grey-green or reddish brown, spots surrounding infection points on needles [

8]. As the disease develops, these spots turn brown, often surrounded by a yellow halo, and for some host species also resin soaked [

11]. These symptoms are followed by dieback of entire needle starting from the tip and its premature shedding. The disease is usually much more prevalent on the previous years’ needles leaving the new growth temporally unaffected and the damage starts from the lower part of the crown [

1,

8]. However, the effect is much less pronounced in

Pinus mugo thickets, which are characterized by relatively low and compact canopy even at advanced age. The disease symptoms described above are similar, especially at the early stage, to those caused by

Dothistroma spp. This lead to numerous instances of misidentification in the past, thus molecular identification methods are now generally required for BSNB reporting.

As of today, Tubby et al. [

1] provides the most comprehensive list of species, almost exclusively pines, for which susceptibility to

L. acicola infection has been established. There are three susceptibility levels recognized in this review, i.e., low, medium and high. Interestingly, numerous species are listed in more than one category. This is the case for some very important central European pines; for instance,

P. sylvestris,

P. mugo, and

P. nigra, which have been determined to be either less, moderately, or highly susceptible depending on the region and growth conditions. Such observations demonstrate that numerous factors affect susceptibility of particular pine species to

L. acicola infection and that at least some of these factors are independent of species’ genetic makeup.

The first record of BSNB in Poland dates back to 2011 [

12,

13] when it was reported from the Karkonosze range of the Sudetes (Karkonosze National Park). However, this symptom-based report lacks molecular verification and should, therefore, be treated with caution. The first confirmed BSNB from Poland comes from 2017 [

14] and was supported by microscopic observations, isolations of

L. acicola cultures, and a variety of molecular detection methods. This time the pathogen was detected on the coast of the Baltic Sea, however, some confusion pertains to the exact site. Whereas the location is reported as Ustka environs, the coordinates point to Białogóra, which is more than 80 km east along the coast. Nevertheless, four new locations were added since then to the

L. acicola geo-database, all from

P. mugo from sites following Baltic coastline: two forest locations and two urban greenery / ornamental plantings. Such a distribution shows that

L. acicola occurrence is directly connected to the

P. mugo as its primary host and to the coastal region of the south-eastern Baltic Sea.

This region is notorious for relatively frequent occurrence of

P. mugo, either in coastal forests and as ornamentals. The history of its presence in the south eastern coast of the Baltic Sea starts approximately in 1820s on Curonian Spit where it was introduced, using Danish stock material, to stop dramatic dune shifts [

15]. The species is particularly well suited for dune stabilization due to its pioneer ecological strategy, wind firmness, as well as sandy substrata and salt-spray tolerance [

16,

17]. These very proprieties made the species ideal as a fore-crop and for afforestation of most exposed dune ridges [

17,

18]. The example of Curonian Spit success led to wide introduction of

P. mugo throughout the region as well as in wider Baltic area including Denmark, Norway, Finland, Sweden, Estonia, Lithuania, and Poland [

16,

19].

Although,

P. mugo subsp.

mugo (referred throughout this paper as

P. mugo or dwarf mountain pine) is a native species in Poland, its natural occurrence is restricted to several mountain locations in southern Poland, both in Carpathians and Sudetes. There it forms its own mountain belt, respectively above and below Norway spruce upper mountain forest and alpine meadow belts [

20]. Thus, for the rest of the country, including the Baltic coastal region, it is actually an exotic species occurring outside of its natural habitat. According to BDL database [

19] there are 177 variously-sized (average size 3,6 ha) forest subcompartments on the Polish coast with dominant share of

P. mugo. However, these are not evenly distributed as there are three major mountain pine reach areas: the Wiślana Spit, Hel peninsula (around the Hel town itself, but not along the entire Hel Spit), and the open coast region stretching from Karwia to the east and Rowy to the West including Słowiński National Park. Only nine

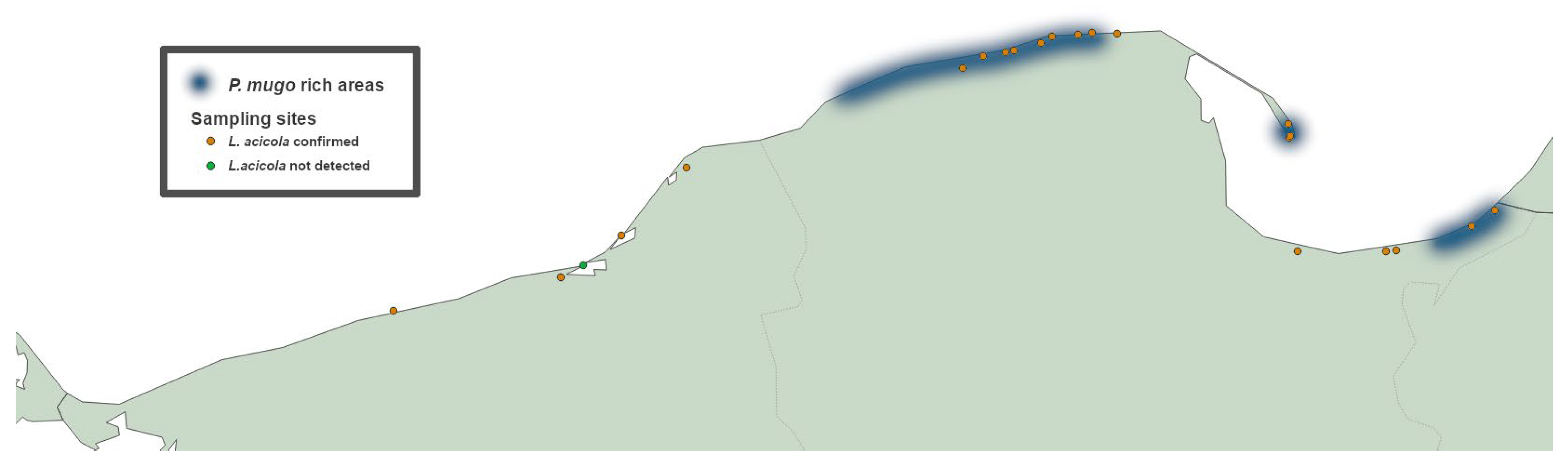

P. mugo dominated subcompartments occur outside these areas, five at the base of the Gdańsk Bay and four far to the west from Rowy (see

Figure 1). Considering reports on the occurrence of

L. acicola in multiple sites on the Polish coast [

14] and its reported fast spread in the neighboring countries [

21] one should assume the Baltic population of

P. mugo in Poland is highly threatened by damage caused by BSNB.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the extent of BSNB spread on P. mugo in the Polish coast of Baltic Sea with the particular emphasis on dense thickets established for dune stabilization. In this study, we also provide the current information on the host range of L. acicola occurring in the Polish Baltic region.

2. Materials and Methods

The observations in the field and collection of needle samples were carried out in three major surveys: in summer 2023 (Jul 6th to Jul 11th), winter 2023 (Dec 18th to Dec 21st) and summer 2024 (Jul 4th to Jul 9th). Some locations were revisited in summer 2025 to confirm the continued presence of the disease and the severity of symptoms. The exact list of visited locations is presented in

Table 1, whereas

Figure 1 shows their geographic distribution. Most of the sites comprise dense patches of

P. mugo dwarf forest planted on shifting sand dunes for the exact purpose of their stabilization and afforestation. Sites of this type were selected in a systematic manner using BDL database [

19]. Using the database, we identified all forest subcompartments with

P. mugo as a dominant species along the entire length of the Polish Baltic coast. As the subcompartments proved to be unevenly distributed along the coastline, we adopted the following rule for selection of survey sites: in areas where

P. mugo dominated stands were relatively frequent we visited subcompartments in c.a. 5 km intervals; wherever

P. mugo subcompartments occurred rarer than 5 km from each other we visited all of them. Using this approach, the entire Polish coast of Baltic Sea was mapped and examined for presence of BSNB in

P. mugo dominated stands. The only exceptions were stands within Słowiński National Park.

The surveys conducted at each site included search for BSNB characteristic symptoms on needles within

P. mugo stands, as well as on the needles of

P. sylvestris and / or

P. nigra individuals if present within or in direct proximity to the examined stand. For every forest location (indicated as dune forest in

Table 1), general observations of disease severity were recorded. Disease severity was considered high if the proportion of infected needles exceeded 30% of the overall amount of still unshed needles throughout the entire stand, any estimation below 30% of infected needles was considered low. When found, symptomatic needles were collected to paper envelopes (3 to 7 envelopes per site) at random from various points across the forest subcompartment or group of ornamentals. When no typical BSNB symptoms were observed on needles within the examined stand, a single sample was collected comprising needles from various trees with unspecific symptoms of any kind visible on needles, usually consisting of necroses or discolorations. In this form the needle samples were stored at -20 °C for further processing.

For most of the sites, the presence of

L. acicola was confirmed by two-step isolation of pure cultures of the pathogen; these locations are indicated in

Table 1 by a number of isolates grown from needle samples collected at that site. Prior to isolations the needles were placed in moist chambers (25-cm-wide Petri plates with wet paper towels) for 2–3 days to stimulate production of conidia. Moist-chamber-incubated needles were then examined under a stereomicroscope (mag. 30 ×) for the presence of conidia visible as olive-green conidial mass erupting from fruiting bodies. The isolation itself started with dispersing the conidial mass, each time from a separate needle, in a droplet of sterile water placed directly on the fruiting body with a Pasteur pipette. Then, water carrying dispersed spores was sucked back into the same pipette and transferred to a Petri plate with MEA+TH medium [Malt Extract, 20 g/L + LAB-AGAR 15 g/L (Biomaxima, Lublin, Poland) + tetracycline hydrochloride 0.085 mg/ml (Polfa Tarchomin, Poland)], where they were spread over the medium with a Drigalski spatula. The plates were incubated at 20 °C in the dark for 3–6 days until 0.1–0.5 mm diameter colonies of

L. acicola emerged. The single

L. acicola colonies were then transferred, along with a 1–2 mm

3 agar block, onto a new MEA+TH plates paying particular attention to select only colonies which were well-separated from each other and located as far as possible from contaminating yeast mold colonies. The resulting

L. acicola isolates were incubated at 20 °C in the dark until they reached c.a. 1 cm diameter.

All acquired isolates were identified molecularly using species-specific PCR primers [

22]. For two locations with ornamental

P. mugo plantings (Mielno and Rusinowo), as well as for two forest locations without visible BSNB symptoms (Dźwirzyno – winter 2023 survey and Łazy – all surveys), the

L. acicola occurrence was tested directly in 10 independent needle samples with the same PCR approach. The procedure started with DNA extraction, either from MEA+TH grown mycelium or from needle tissue. Mycelium fragments for isolation (10–30 mg) were collected with a sterile scalpel directly from the colonies, placed in a 2-ml microcentrifuge tube with two stainless steel beads (⌀ 3 mm) and homogenized in an oscillation mill (MM 200; Retsch, Germany) for 2 min at 25 Hz. Needle fragments (c.a. 15-mm-long) carrying symptoms, either typical BSNB symptoms and fruiting bodies or any unspecific symptoms, were dissected and pre-comminuted with sterile scissors. Then, the samples were transferred to 2-ml microcentrifuge tubes with three stainless steel beads (⌀ 3 mm) and homogenized using the same oscillation mill (6 min at 25 Hz). Total genomic DNA for both types of samples was extracted using GeneJET Genomic DNA Purification Kit (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and stored at -80 °C for further analysis. The identification test itself relies on the use of

L. acicola species-specific primers LAtef-F and LAtef-R targeting translation elongation fator 1-α region [

22]. Appropriate positive and negative (molecular grade water) controls were included in all runs. Reaction mixtures comprised 1 × PCR Mix Plus Green PCR ready mix (A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland), 8 mmol MgCl

2, and 0.08 μm each primer in a total volume of 25 μl. Amplifications were run on a T100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad) using the following cycling profile: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min., 25 touchdown cycles consisting of 30 s of denaturation at 94 °C, 30 s of annealing at decreasing temperatures (0.5°/cycle from 67.5 °C in the 1st to 55 °C in the 25th cycle), and 1 min of elongation at 72 °C, for 20 next cycles a constant annealing temperature of 55 °C was used, followed by final elongation step at 72 °C for 10 min. The reaction results were verified using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis [8 V/cm, 30 min., 2% agarose gel supplemented with SimplySafe DNA stain (0,001%, EURx, Gdańsk, Poland)]. Positive identifications were indicated by the successful amplification of the target product of 237 bp.

3. Results

In this study, the BSNB occurrence in

P. mugo stands along the Polish Baltic coast was investigated. Most of the observations were conducted during three surveys in summer 2023, winter 2023, and summer 2024, however some locations were visited multiple times. During the surveys, characteristic symptoms of the disease (see

Figure 2) were observed in vast majority of forest locations, which were the main focus of this study, as well as in several ornamental plantings (

Table 1). These include Białogóra, Choczewo Forest District, that is the very site where the disease was observed for the first time on the Polish coast of Baltic Sea. For all these sites the presence of BSNB pathogen

L. acicola was confirmed by the isolation of pure cultures and / or by species-specific PCR assay. The only site where BSNB symptoms were not observed during all visits was Łazy (Karniszewice Forest District). The BSNB free status of this site was further indicated by negative results of PCR test for

L. acicola conducted after each survey based on needle samples carrying unspecific symptoms. Thus in total, the pathogen was detected in 21 out of 22 surveyed locations (

Table 1), with multiple sites yielding numerous isolates, indicating an established and widespread occurrence of

L. acicola in coastal

P. mugo thickets.

However, the situation for the two westernmost forest sites is more complicated. These include Dźwirzyno (Gościno Forest District) and Łazy (Karniszewice Forest District). Both of the sites proved to be BSNB free either in summer 2023 (Łazy) or winter 2023 (Dźwirzyno). There were also no L. acicola detections from these sites using PCR assay. The only location in this area where BSNB symptoms were observed as early as winter 2023 is Mielno where the disease was spotted on a group of ornamentals. During the next survey in summer 2024 the Łazy site was still BSNB free, but Dźwirzyno showed typical BSNB symptoms, including readily visible L. acicola fruiting bodies on needles; based on the needle samples from 2024 a total of 42 L. acicola isolates were obtained here.

Whereas BSNB symptoms were observed in almost all examined P. mugo thickets planted along the Polish coastline, the disease severity varied between locations. The main difference in the disease incidence reflected the stage of succession of pine spices within a given dune forest. Wherever P. mugo individuals grew in monospecific compact thickets the severity of the disease was high: the incidence of diseased needles easily exceeded 30% including current year needles, resulting in high defoliation levels. The only exception to this rule is once again the westernmost Dźwirzyno site where disease incidence was low despite compact monospecific composition. The disease occurrence pattern changed when stands became overgrown by other pine species, usually by P. sylvestris but sometimes also by P. nigra. This process involves gradual decline of dwarf mountain pine due to reduced access to sunlight resulting in heavily reduced foliage and eventually dieback of P. mugo individuals. In such conditions, however, the BSNB incidence decreases significantly, rarely exceeding 30%. Succession to other pine species is of course gradual and the general trend observed throughout this type of locations is that the more overgrown P. mugo patch becomes, the lower BSNB incidence was observed.

Despite the fact that the vast majority of BSNB cases reported in this study originate from P. mugo, either forest stands or ornamental plantings, the disease could be also observed on P. sylvestris. Indeed, a total of 48 L. acicola isolates originate from P. sylvestris needles collected at two sites (see

Table 1). However, each time the Scots pine individuals, on which BSNB symptoms were observed, grew within or in direct proximity to heavily infected P. mugo thickets. The disease incidence on them was always lower compared to mountain pine. Besides that, no readily visible stand-alone cases of BSNB on pines other the P. mugo were observed. Moreover, noticeable variation in susceptibility to BSNB among P. sylvestris individuals was evident; whereas some trees displayed varying levels of infection others were completely disease free (

Figure 2c) despite heavy inoculum pressure resulting from close proximity to infected P. mugo individuals.

4. Discussion

The mass introduction of

P. mugo for dune stabilization of the coastal dunes on Polish coast dates back to at least early 20th century. According to the BDL database [

19] the oldest, still existing mountain pine stands are 114-year-old (as of 2025). Out of 177 identified subcompartments 156 have been established prior to World War II end in 1945, and only three of them are younger than 40-year-old (see

Supplementary Table S1). This is particularly evident in the eastern part of the Polish coast where the average age of

P. mugo is 91. That means there have been no new predominantly mountain pine plantings for dune stabilization east of Rowy (54°40′07.8”N 17°03′20.0”E, Słowiński National Park western margins) for 59 years, which is the age of the youngest of

P. mugo stands in this part of the coast. The advanced age of these stands results in the situation where they undergo succession to other pine species, predominantly

P. sylvestris. Thus, it can be argued based on these data that introduction of

P. mugo in this part of the coast, that is as a fore-crop, has served its purpose, as most of the dangerous shifting dunes, have been successfully afforested and the remaining few are protected for touristic and ecological reasons [

23,

24]. Only four

P. mugo dominant subcompartments exist on the Polish coast to the west of Rowy and these are much younger (average age of 36) and much more widely separated from each other. The Dźwirzyno site is unique in this regard as it is the westernmost of all the subcompartments and the only new planting of

P. mugo (22 year old) for dune stabilization along the entire Polish coast [

19]. That being said, there is a number of forest stands along the coast with minority occurrence of mountain pine. This is particularly true for the Ustka surroundings and the area of the adjutant Ustka-Wicko Morskie Central Air Force Training Range where the BDL database lists 42 forest subcompartments (see

Supplementary Table S1) with

P. mugo as the most common species within understory layer [

19]. Apart from that, numerous ornamental plantings have been established throughout Baltic regions using

P. mugo for the last few decades, which is a very popular ornamental shrub in Poland [

25].

Such a distribution pattern of

P. mugo stands strongly favors natural spread of

L. acicola in the eastern part of the Polish coastline. The primary dispersal mode of

L. acicola is asexual and involves water-splashed conidia [

26,

27,

28]. This is a very short distance method where infection success diminishes rapidly just 1.5 to 3 m from the source [

26], although much longer travels of conidia of 60 m have been demonstrated using spore traps [

29]. This short distance effect is most probably the reason for the greatly reduced BSNB incidence at sites where

P. mugo stands became overgrown by other pine species. Such a situation inevitably leads to increased distances between

P. mugo individuals and thus, reduced infection rates. Another factor favoring

L. acicola spread in thickets composed mostly of

P. mugo is its dwarf habit. Most spine species when matured acquire a degree of resistance to foliar diseases [

30,

31]. For the large part, this is due to higher canopy and greater spacing between trees sustained in older stands. This reduces infection rates from shed needles on the forest floor and allows for lower overall humidity at the canopy level [

32]. These effects are less pronounced in dwarf

P. mugo. The long distance natural spread in

L. acicola is achieved via wind-disseminated ascospores [

27]. Completing the sexual cycle in

L. acicola requires both mating types to be present and indeed, both MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 idiomorphs have been reported to occur in Poland, the Baltics, and the most of Europe, however, usually not in the proportions suggesting frequent sexual recombination [

10]. Thus, the potential for natural ascospore-mediated dispersal along the Polish coast exists even between areas with less frequent occurrence of

P. mugo, which is its main host in Poland and in northern and central Europe [

8].

However, human mediated dispersal is also a very important factor in

L. acicola worldwide expansion. Indeed, multiple instances of genetically identical

L. acicola individuals isolated from locations on different continents have been recorded recently using microsatellite markers [

10]. As mentioned above, the planting of

P. mugo as a dune stabilization method for the most part of the Polish coast has been phased out. Thus dispersal with forestry planting material does not seem to play a major role in the pathogen’s spread. On the contrary, transport of

P. mugo seedlings for very popular ornamental plantings poses greater threat. However, activities related to touristic traffic seem to be the most significant in

L. acicola dispersal along the Baltic coast in Poland, as the region is visited by millions of tourists each summer season. The vast majority of

P. mugo dominant subcompartments identified in this study are located in the forest belt separating coastline beaches and inland transport infrastructure, including roads, biking routes, and publicly available walkways. To access the beaches, tourists usually must cross the forest belt, from where

L. acicola conidia or entire infected needles can be vectored to other locations visited next day. Such a mechanism, that is accelerated

L. acicola spread in areas with high touristic traffic, has been previously suggested in Slovenia [

1].

Lecanosticta acicola spread in Europe is relatively well documented [

1]. For a few decades from the first outbreak of the pathogen in Spain in 1940s to late 2000s / early 2010s a number of new reports throughout western and southern Europe appeared. Since then, the spread of

L. acicola significantly accelerated resulting in numerous new country reports from central, eastern, and northern Europe. For this study, the most relevant events pertain to the spread of the BSNB pathogen in the Baltic Sea region, where it was detected for the first time in Estonia in 2008 [

33], Then in 2010 on the Curonian Spit, Lithuania [

34], in 2012 in the Latvian National Botanical Garden in Salaspils near Riga [

35] and finally in 2017 on the Polish coast [

14]. Thus, in less than a decade

L. acicola presence have been noticed along the entire south-eastern coast of the Baltic Sea except for the Kaliningrad region of Russia. However, the exact chronology of its dispersal in the region has not been established. The literature lacks any reports of systematic surveys for pine needle pathogens in

P. mugo dune population in Poland for at least the last two decades. The study of [

25], focusing on detection of

Dothistroma spp. in Poland, does include two coastal sites where

P. nigra stands were examined in 2013, however no

P. mugo stands on the coast were visited then. Therefore, it is currently impossible to establish for how long

L. acicola was present in northern Poland prior to [

14] report.

Our results show nearly ubiquitous occurrence of

L. acicola and its associated BSNB symptoms in

P. mugo stands along the Polish coast of Baltic Sea. The pathogen universally occurred in all examined sites throughout all three major areas of high

P. mugo concentration: Wiślana Spit, Hel peninsula, and the open coast region surrounding Łeba. It also occurred in all examined sites located at the base of the Gdańsk Bay. Based on this result, it is safe to assume that virtually all mountain pine dominated stands throughout this part of the coast are infected by

L. acicola. Here, we also observed numerous instances of Scots pine, a native species to Poland, being infected if present in direct proximity to heavily infected

P. mugo individuals. These were always relatively young trees (up to c.a. 30-year-old) and severity of BSNB symptoms was always lower compared to mountain pine, but the severity of symptoms on Scots pine varied significantly between individuals. In this regard, this situation is very similar to that observed for

Dothistroma septosporum whose infection of exotic pine species, including

P. mugo, results in much higher disease incidence and usually more severe damage compared to infections of native

P. sylvestris [

25]. Thus, the main concern resulting from the spread of these pathogens on exotic pines is the risk of emerges of

P. sylvestris adapted genotypes, whose economic impact on the Scots pine dominated forestry in Poland would be potentially orders of magnitude greater.

Similar, but not the same situation occurs in the western part of the Polish coast where pure or nearly pure P. mugo forest subcompartments are much less frequent. Initially, only two such sites were identified here and both proved to be L. acicola free in 2023 (Dźwirzyno, winter 2023; Łazy, summer and winter 2023). However, the pathogen was clearly present in the area detected on ornaments (Mielno, winter 2023). Already, during summer 2024 survey Dźwirzyno site showed clear signs of infection (confirmed later molecularly), as well as another newly identified site in the area (Dąbki), however, Łazy site once again remained L. acicola free.

Such results suggest the very recent dispersal of L. acicola to the area, as we believe we caught the pathogen’s introduction to Dźwirzyno site within a six-month window between July and December 2023. However, this can be also due to chance as the site is occupied by the youngest P. mugo stand among all identified on the coast. Thus, it is possible that L. acicola population already established in the area, e.g., on ornamental P. mugo plantings, did not have time to reach this particular site. This question, as well as broader history of L. acicola dispersal along the Polish Baltic coast, can be relatively easy resolved in a genetic diversity analysis.

This paper does not provide genetic diversity data for Polish coastal population of

L. acicola, thus we refrain from speculating on the papulation’s genetic makeup. However, two recent papers: a preliminary investigation of local

L. acicola diversity in Lithuania [

36] and much more comprehensive worldwide genetic diversity study [

10], do include isolates from a single Polish site. Both these analyses suggest that Polish coastal population is related to wider eastern Baltic stock, but not to

L. acicola genetic cluster dominating Curonian Spit. This, of course, suggests that the pathogen spread from the Baltics to Polish coastal regions, either naturally or via human-mediated transport, intentional or otherwise, of plant material [

36]. The alternative explanation, that is

L. acicola dispersal from the southern Poland where BSNB was previously reported (but without molecular detection of the pathogen), is much less likely, especially that

L. acicola has not been detected in two NGS based studies of fungi occurring in pine needles from southern and central Poland [

37,

38].

Thus, the extensive collection of L. acicola isolates generated in this study from multiple sites representing nearly all areas of Polish coast where P. mugo occurs, opens a unique opportunity to track the pathogen’s dispersal using molecular markers and phylogeographic methods. Such genetic data are necessary to verify our working hypothesis assuming that the situation currently observed represents the very initial stages of L. acicola expansion on the Polish coast. The work on such a genetic analysis is currently under way in our team.