Submitted:

24 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Objectives

- To design and implement a gamified educational resource, Marine Dobble, adapted to local marine species, as an innovative strategy within Environmental Education for Sustainability and for the integration of ocean literacy into the classroom.

- To foster knowledge, curiosity, and environmental awareness among 1º ESO students regarding marine biodiversity, its habitats, adaptations, and the challenges associated with global change.

- To explore the potential of gamification as an active methodology to promote motivation, participation, and the development of pro-environmental attitudes among students.

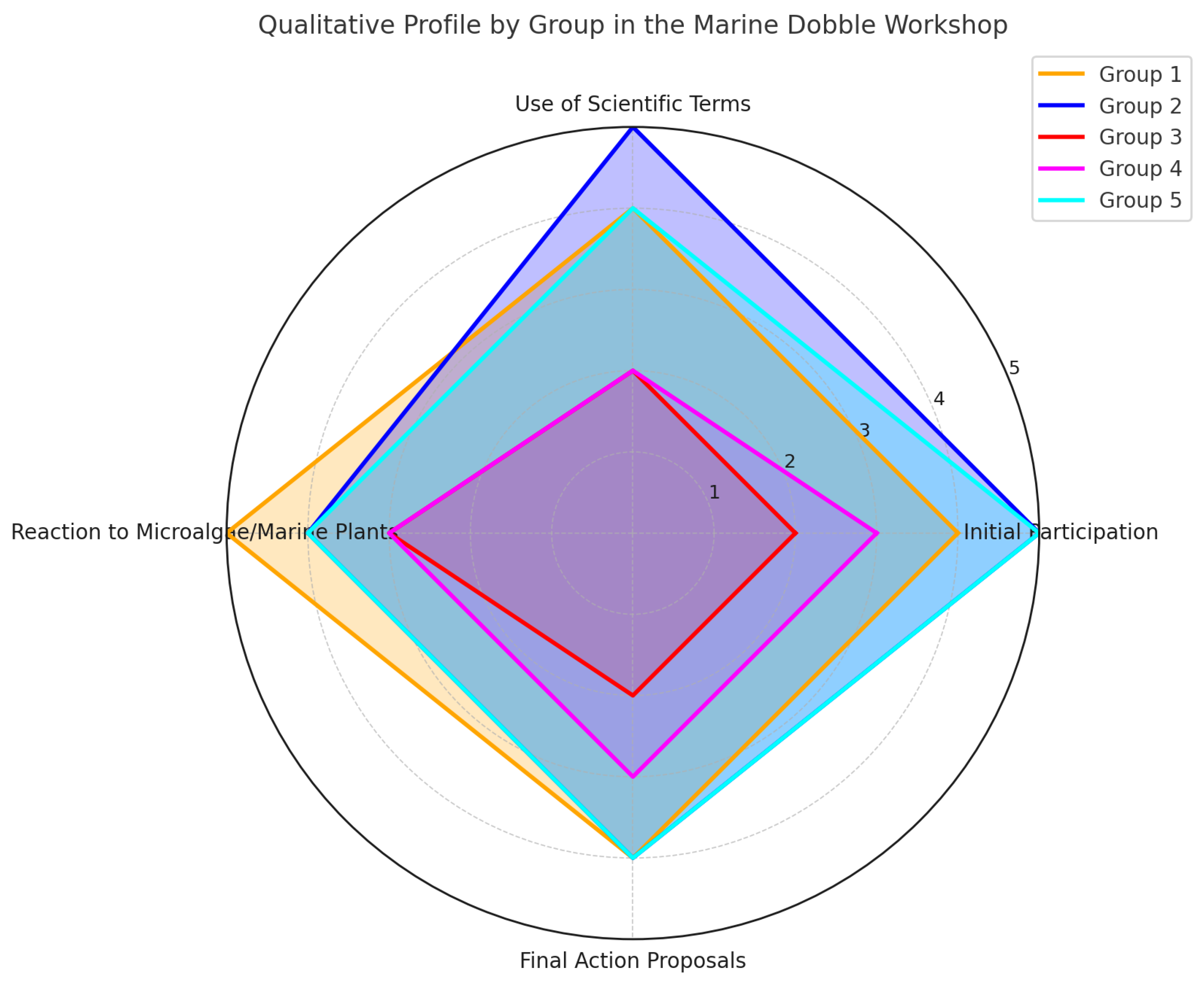

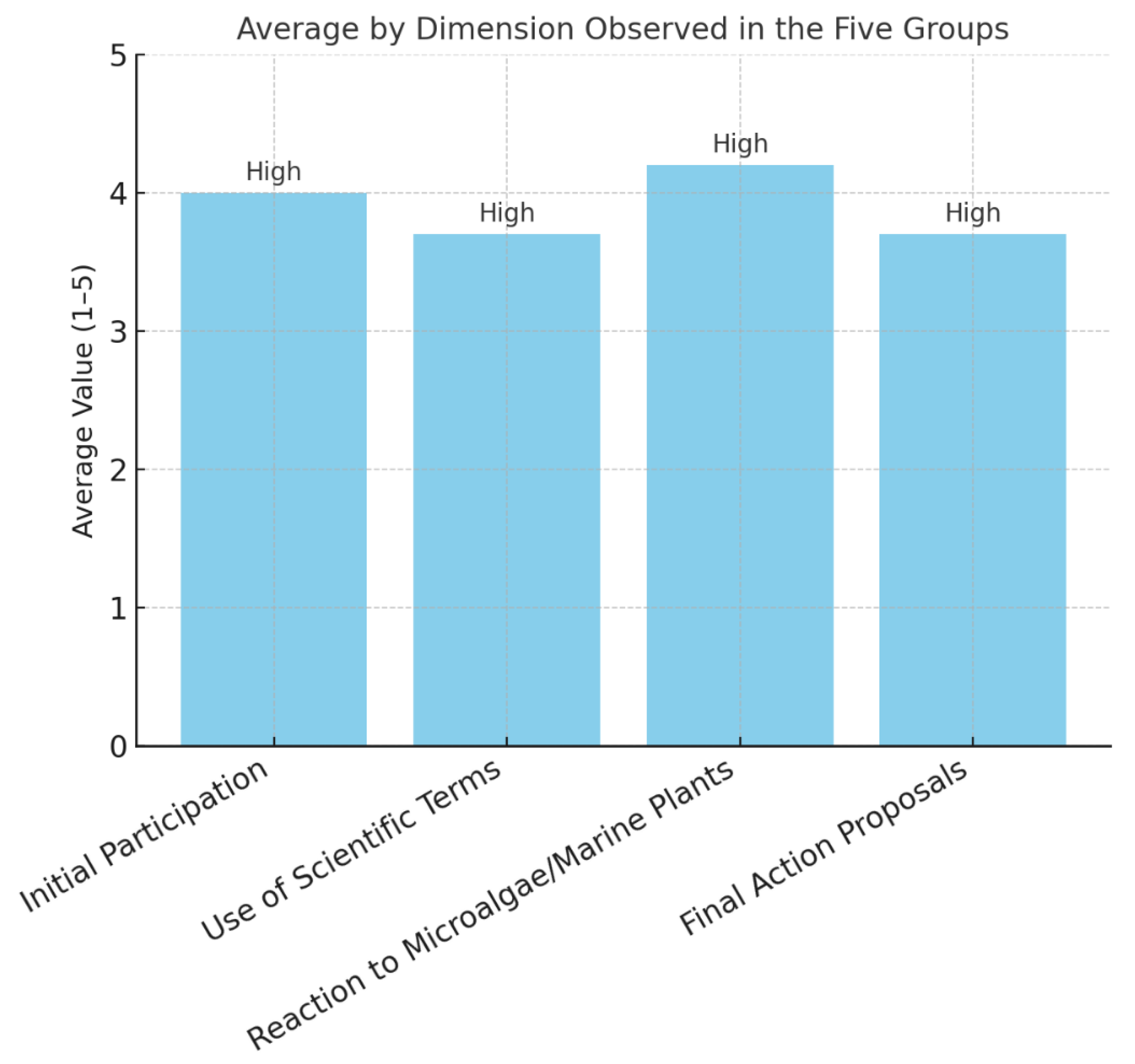

- To qualitatively analyze students’ responses to the proposal, considering indicators such as participation, use of scientific vocabulary, emotional reactions to new content and suggested actions for ocean conservation.

- To assess the replicability and transferability of the experience to other formal and non-formal educational contexts, as a contribution to the 2030 Agenda and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 14: Life Below Water.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Theoretical Principles: Environmental Education for Sustainability and Ocean Literacy.

- The Earth has one big ocean with many features.

- The ocean and the life within it shape the Earth.

- The ocean influences climate and weather.

- The ocean makes the Earth habitable.

- The ocean supports a great diversity of life and ecosystems.

- The ocean and humans are inextricably interconnected.

- The ocean is largely unexplored.

2.2. Gamification as an Active Methodology in Environmental Education Workshops

3. Methodology

3.1. Context and Participants

3.2. Design of the Educational Experience

| Workshop Phase | Topics Worked | Didactic Intentions |

|---|---|---|

| Pause 1: Marine Habitats | Diversity of marine habitats and species distribution (seafloor, beaches, open waters). | Recognize the variety of marine ecosystems and their ecological importance. |

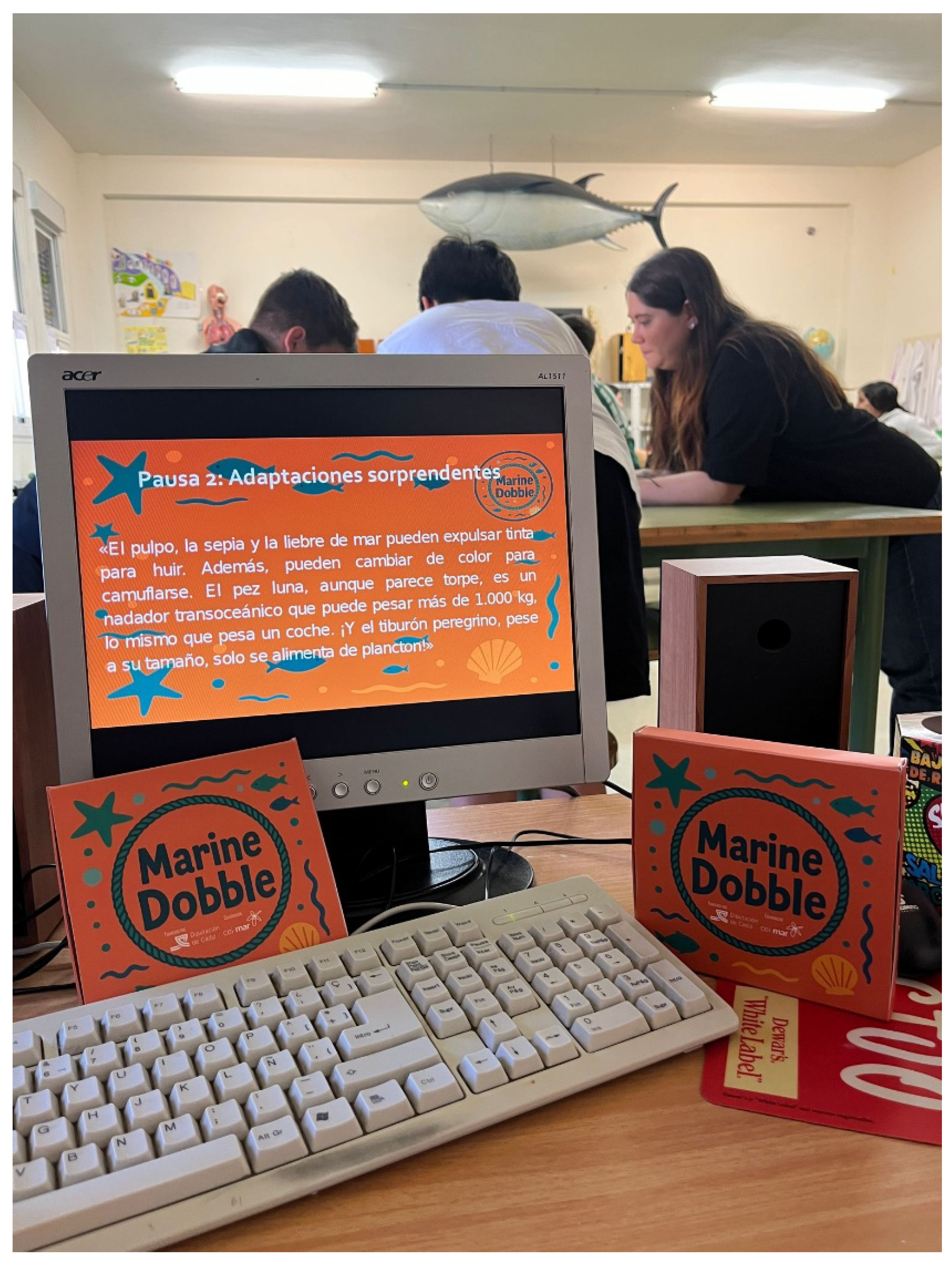

| Pause 2: Surprising Adaptations | Physiological and behavioral adaptations of species (camouflage, ink, filtration). | Appreciate the adaptive richness of marine organisms and their connection with the environment. |

| Pause 3: Did You Know…? | Scientific curiosities: distinctions between algae and plants, remarkable species, living fossils. | Foster wonder, scientific thinking, and interest in biodiversity. |

| Pause 4: Ocean Challenges | Environmental impacts: pollution, warming, threatened species, and plastics. | To understand the relationship between human activities and environmental degradation. |

| Pause 5: Commitment to the Ocean | Individual and collective commitment to ocean conservation from land. | To promote awareness and responsible action in addressing ocean challenges. |

3.3. Specific Competencies and Core Knowledge Addressed According to the LOMLOE

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Observation Instrument

4.2. Start of the Workshop: Activation of Prior Ideas and Predisposition

4.3. Game: Motivation, Interaction, and Connection with Content

4.4. Didactic Pauses: Wonder, Understanding, and Dialogue

Pause 1: Marine Habitats

Pause 2: Surprising Adaptations

Pause 3: Did You Know…?

Pause 4: Ocean Problems

Pause 5: Commitment to the Ocean

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

6. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vilches, A.; Gil, D.; Cañal, P. La educación científica y el cambio global. Revista Eureka sobre Enseñanza y Divulgación de las Ciencias 2010, 7, 2–19. [Google Scholar]

- Guevara Herrero, M.; Bravo Torija, B.; Pérez Martín, D. Cultura oceánica y didáctica de las ciencias: una revisión crítica. Revista Eureka sobre Enseñanza y Divulgación de las Ciencias 2020, 17, 3403. [Google Scholar]

- Vilches, A.; Gil, D.; Cañal, P. Educación para la sostenibilidad: un reto para la educación actual. Revista Eureka sobre Enseñanza y Divulgación de las Ciencias 2008, 5, 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Murga-Menoyo, M. Educación para la sostenibilidad: principios pedagógicos y didácticos. Revista Internacional de Educación Ambiental y Ciencias 2018, 3, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Martín, D.; Bravo-Torija, B. Educación para la sostenibilidad en la escuela: una propuesta de enfoque didáctico. Didácticas Específicas 2018, 19, 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cava, F.; Schoedinger, S.; Strang, C.; Tuddenham, P. Ocean Literacy: The Essential Principles of Ocean Sciences K–12; NOAA: Washington, DC, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, D.; Marrero, M. Educating for Ocean Literacy: A How-To Guide for Effective Education; Springer: Cham, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Armario, M.; Brenes, M.; Ageitos, N.; Puig, B. ¿Las orcas pasan o se quedan? Alambique 2024, pp. 15–21.

- Ageitos, N.; Puig, B.; López, A.; Ojeda-Romano, G.; Pintado, J. Desde las orcas hasta la vida marina en suspensión. Promover la cultura oceánica. In Pensar científicamente. Problemas sistémicos y acción crítica; Puig, B., Crujeiras-Pérez, B., Blanco-Anaya, P., Eds.; Graó: Barcelona, 2023; pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Plan de Acción de Educación Ambiental para la Sostenibilidad (PAEAS) 2021–2025; MITECO: Madrid, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mogollón, J.; Pujol, R.; Sabariego, M. Competencias para la sostenibilidad: un marco de referencia en educación superior. Revista de Educación Ambiental y Sostenibilidad 2022, 2, 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Río, J.; Méndez-Giménez, A. Metodologías activas y educación física: una revisión sistemática. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y del Deporte 2020, 20, 113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Tilbury, D. Education for Sustainable Development: An Expert Review of Processes and Learning; UNESCO: París, 2011. [Google Scholar]

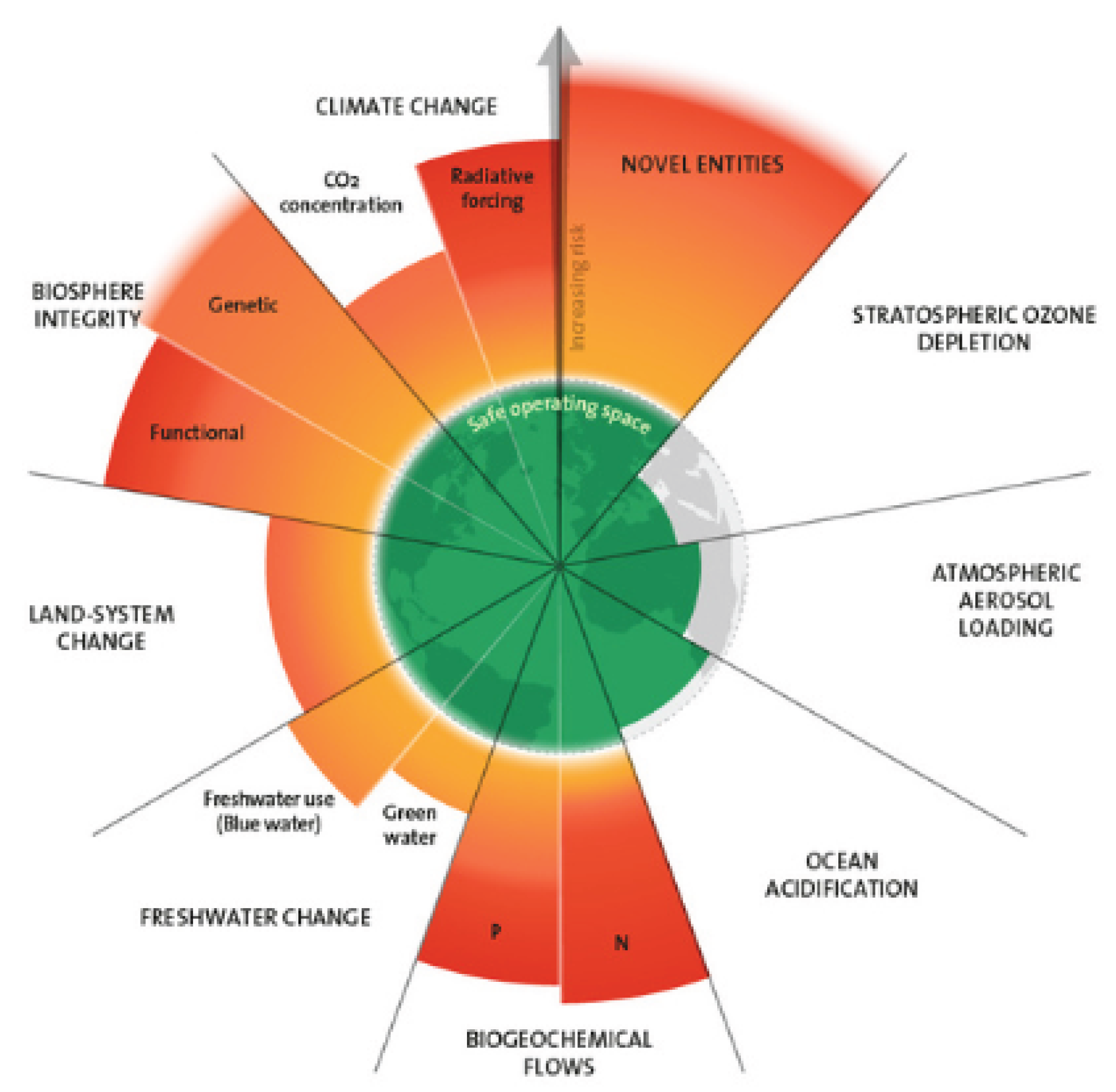

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, A.; Chapin, F.; Lambin, E.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, A. La educación ambiental en tiempos de crisis ecosocial. Revista Universitaria de Educación Ambiental 2010, 12, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, K.; Steffen, W.; Rockström, J.; Lenton, T.; Folke, C.; Liverman, D.; et al. Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Science Advances 2023, 9, eadh2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jambeck, J.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; et al. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusher, A.; Hollman, P.; Mendoza-Hill, J. Microplastics in fisheries and aquaculture: Status of knowledge on their occurrence and implications for aquatic organisms and food safety; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 615, FAO: Rome, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Benavides, A.; Cardona, R.; López, J. Estrategias didácticas activas en la enseñanza de las ciencias. Revista Electrónica de Educación en Ciencias 2020, 15, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A. Beyond unreasonable doubt: Education and learning for socio-ecological sustainability in the Anthropocene; Wageningen University: Wageningen, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNECE. Learning for the future: Competences in Education for Sustainable Development; United Nations Economic Commission for Europe: Geneva, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C. Key competencies in sustainability: a reference framework for academic program development. Sustainability Science 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escorcia, J.; Orozco, L. Educación ambiental transformadora. Praxis & Saber 2022, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Castillo, J. Estudio de los flujos de dispersión de los residuos plásticos en el Golfo de Cádiz. Revista Eureka sobre Enseñanza y Divulgación de las Ciencias 2019, 16, 3501. [Google Scholar]

- España. Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de diciembre, por la que se modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación (LOMLOE). Boletín Oficial del Estado, 2020.

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From game design elements to gamefulness: defining “gamification”. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, New York, 2011; pp. 9–15. [CrossRef]

- Kapp, K. The gamification of learning and instruction: game-based methods and strategies for training and education; John Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zichermann, G.; Cunningham, C. Gamification by design: Implementing game mechanics in web and mobile apps; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel, D. The Psychology of Meaningful Verbal Learning; Grune & Stratton: New York, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, J. Learning, Creating, and Using Knowledge: Concept Maps as Facilitative Tools in Schools and Corporations; Routledge: New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Milanés, O.; Menezes, P.; Quellis, L. Educación ambiental transformadora. Revista Pedagógica 2019, 21, 500–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lirussi, F.; Ziglio, E.; Curbelo Pérez, D. One Health y las nuevas herramientas para promover la salud. Revista Iberoamericana de Bioética 2021, pp. 1–15.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 2020 NOAA Science Report; NOAA Science Council: Silver Spring, MD, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barboza, L.; Vethaak, A.; Lavorante, B.; Lundebye, A.; Guilhermino, L. Marine microplastic debris. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2018, 133, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aragón, L.; Brenes-Cuevas, C. A gamified teaching proposal using an escape box to explore marine plastic pollution. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).