1. Introduction

Printed circuit boards (PCBs) form the backbone of electronic systems by mechanically supporting and electrically connecting components. Even minor PCB surface defects – such as scratches, open circuits, or solder shorts – can cause malfunctions and degrade overall system performance [

1]. Ensuring product quality and reliability therefore requires effective PCB defect detection. Traditionally, manufacturers have relied on manual visual inspection and automated optical inspection (AOI) for PCB quality control [

2]. Manual inspection is labor-intensive and prone to inconsistency, while conventional machine-vision methods struggle with the complexity of PCB patterns and the diverse appearances of defects [

2]. AOI techniques (e.g., template comparison or design-rule checking) can detect many defects but often require strict image alignment and controlled lighting; they also have difficulty generalizing to new defect types [

3]. In practice, as new defect patterns continually emerge with changes in manufacturing processes, rule-based AOI systems must be frequently recalibrated to handle unseen anomalies [

3]. These limitations, combined with the subjective and error-prone nature of human inspection, have driven a shift towards deep learning-based approaches for PCB defect detection [

4].

Deep learning, especially convolutional neural networks (CNNs), can automatically learn discriminative visual features and has achieved superior accuracy in general image recognition tasks – in some cases even approaching or exceeding human-level performance [

5]. By leveraging CNN models, PCB inspection systems become more adaptable to diverse or subtle defects without requiring explicit modeling of each defect type. In recent years, numerous studies have applied deep CNNs to PCB defect detection and reported significant improvements in detection accuracy over traditional methods [

4]. For example, a 2021 study by Kim et al. developed a skip-connected convolutional autoencoder to identify PCB defects and achieved a detection rate up to 98% with false alarm rate below 2% on a challenging dataset [

1]. This demonstrates the potential of deep learning to provide both high sensitivity and reliability in detecting tiny flaws on PCB surfaces, which is critical for preventing failures in downstream electronics.

Object detection models based on deep learning now dominate state-of-the-art PCB inspection research [

6]. In particular, one-stage detectors such as the You Only Look Once (YOLO) family have gained popularity for industrial defect detection due to their real-time speed and high accuracy [

7,

8]. Unlike two-stage detectors (e.g., Faster R-CNN) that first generate region proposals and then classify them, one-stage YOLO models directly predict bounding boxes and classes in a single forward pass – making them highly efficient [

6,

8]. Early works demonstrated the promise of YOLO for PCB defect detection. For example, Adibhatla et al. applied a 24-layer YOLO-based CNN to PCB images and achieved over 98% defect detection accuracy, outperforming earlier vision algorithms [

9]. Subsequent studies have confirmed YOLO’s advantages in this domain, showing that modern YOLO variants can even rival or surpass two-stage methods in both detection precision and speed [

6,

8]. The YOLO series has evolved rapidly—from v1 through v8 and, most recently, up to v11—with progressive architectural and training refinements (e.g., stronger backbones, decoupled/anchor-free heads, improved multi-scale fusion, advanced data augmentation, and Intersection-over-Union (IoU) aware losses) that collectively enhance accuracy–latency trade-offs across application domains [

10] For instance, the latest YOLO models employ features like cross-stage partial networks, mosaic data augmentation, and CIoU/DIoU losses to better detect small objects and improve localization [

11,

12]. YOLOv5, in particular, has become a widely adopted baseline in PCB defect inspection, valued for its strong balance of accuracy and efficiency in finding tiny, low-contrast flaws in high-resolution PCB images [

13,

14]. Open-source implementations of YOLOv5 provide multiple model sizes (e.g., YOLOv5s, m, l, x) that can be chosen to trade off speed and accuracy, facilitating deployment in real-world production settings [

13]. However, standard YOLO models still encounter difficulties with certain PCB inspection challenges, such as extremely small defect targets, complex background noise, and limited training data. This has motivated researchers to embed additional modules into the YOLO framework and to explore semi-supervised training strategies tailored to PCB defect detection.

One major challenge in PCB defect inspection is the very small size and subtle appearance of many defect types (e.g., pinhole voids, hairline copper breaks). These tiny defects may occupy only a few pixels and can be easily missed against intricate PCB background patterns [

4]. To address this, recent works have integrated attention mechanisms into YOLO detectors to help the network focus on important features. In particular, channel attention modules such as the Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) and Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) have been added to emphasize defect-relevant feature channels and suppress irrelevant background information [

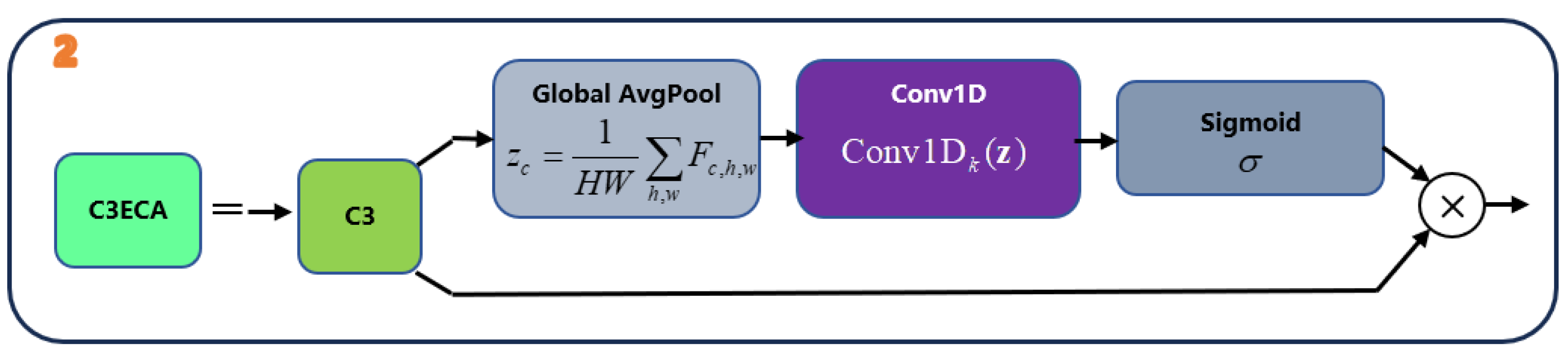

15]. For example, Xu et al. reported that inserting a CBAM module into a YOLOv5-based model improved recognition of intricate, small PCB defects under complex backgrounds by enhancing the model’s attention to critical regions. A lightweight variant, Efficient Channel Attention (ECA), has proved effective in detection settings; by applying a short 1-D convolution to model local cross-channel dependencies—without the dimensionality reduction used in SE/CBAM—ECA enhances feature saliency with negligible computational overhead [

16]. Kim et al. demonstrated that adding an ECA module into a YOLOv5 backbone boosted the detection of small objects in aerial images, as the channel attention helped highlight faint targets against cluttered backgrounds [

16]. Similarly, an enhanced YOLOv5 model for surface inspection found that integrating ECA improved the identification of fine defects (especially tiny or low-contrast features) compared to using SE attention alone [

17]. These findings underscore that incorporating efficient attention mechanisms enables YOLO models to better capture subtle defect cues that might otherwise be overlooked. A streamlined ECA module is embedded in the YOLOv5 backbone to adaptively accentuate faint PCB defect patterns, enabling clearer separation of true defect signals from background circuitry.

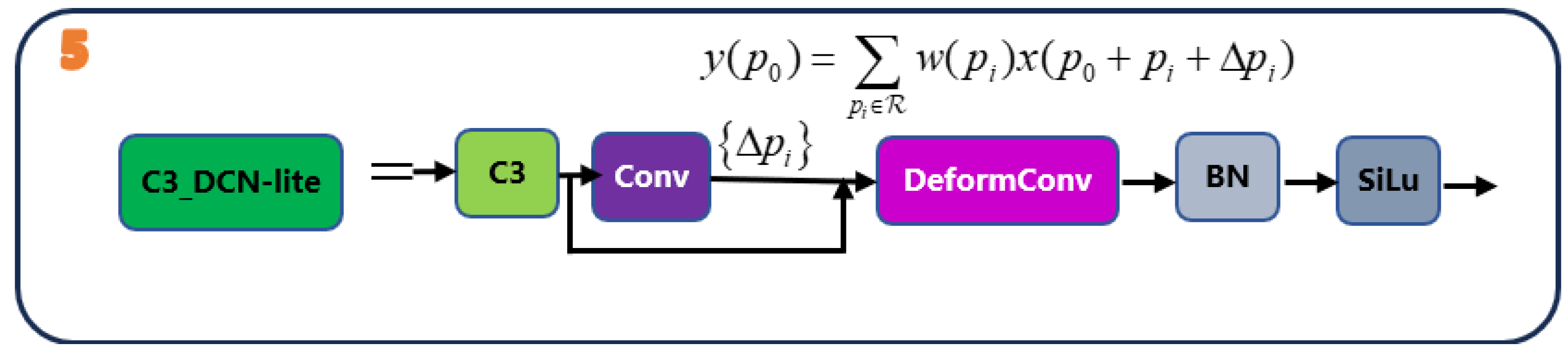

Another limitation of vanilla YOLO detectors lies in the fixed sampling grid of standard convolutions, which restricts the receptive field from conforming to irregular defect geometries on PCB. Deformable Convolutional Networks (DCN) alleviate this constraint by learning location-dependent offsets so that kernels adaptively sample informative positions, effectively “bending” to follow fine discontinuities, burrs, and spurious copper patterns. By aligning the sampling lattice with true object boundaries, deformable convolutions help prevent the mixing of faint defect signals with background textures and thereby preserve small-object detail during feature extraction [

12]. Recent journal studies show that inserting a deformable layer into YOLO backbones or necks yields measurable gains on small-object benchmarks by retaining object cues and reducing background interference [

18,

19]. In the PCB context, improved YOLO variants that integrate DCN (or DCNv2) into high-resolution feature paths report enhanced localization of tiny, irregular defects and higher mean Average Precision, attributable to better spatial alignment around hairline breaks and micro-holes [

20]. Beyond PCB imagery, complementary evidence from aerial and industrial surface datasets confirms that lightweight DCN blocks can be deployed with modest computational overhead to sharpen feature selectivity on thin, elongated structures—an effect particularly valuable for defect edges and gaps [

19,

21]. Following these insights, a DCN-lite layer is placed in the YOLOv5 neck to introduce spatial flexibility where fine spatial detail is most critical, aiming to increase sensitivity to minute or oddly shaped PCB anomalies while preserving throughput [

20,

22].

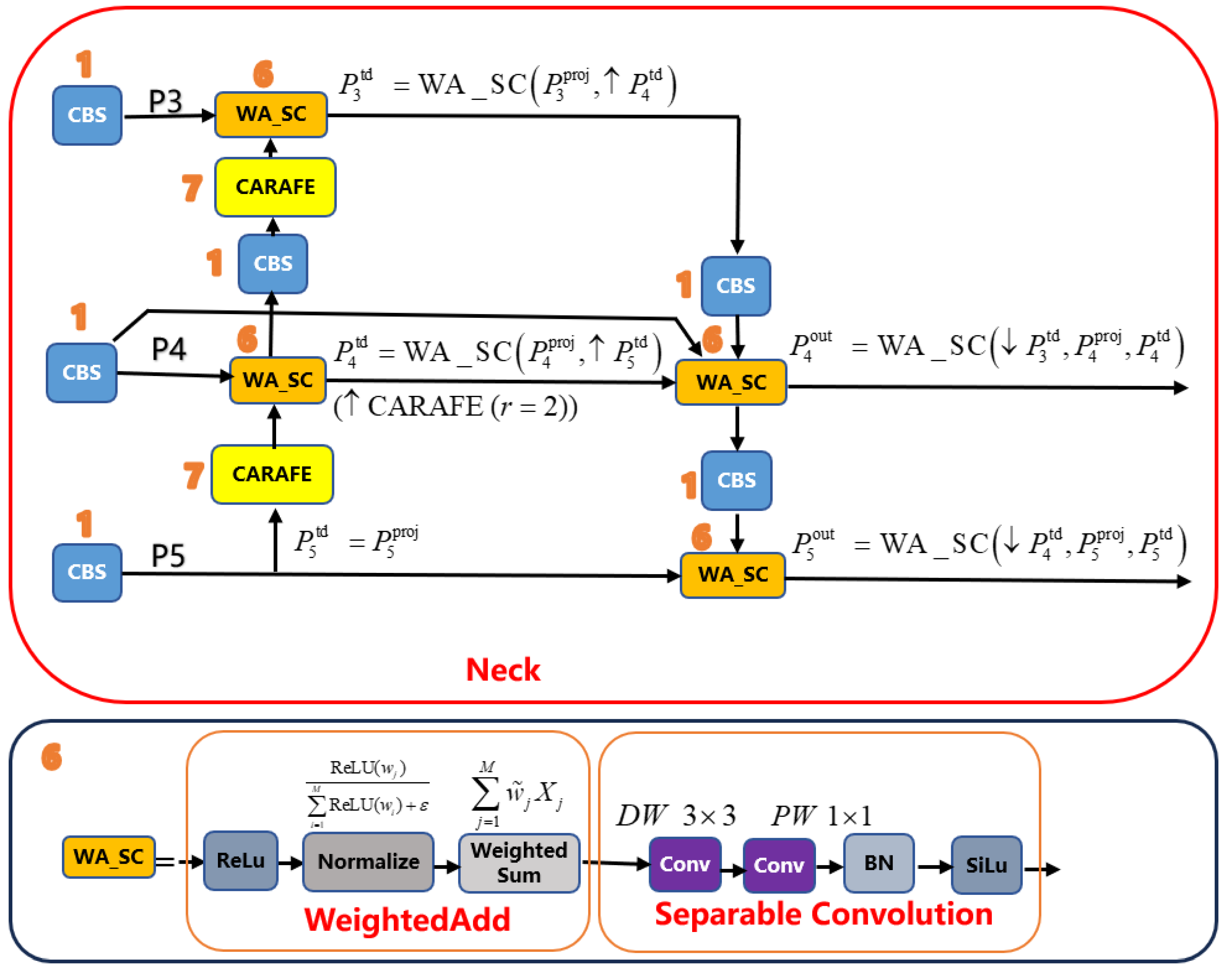

Effective multi-scale feature fusion is essential in PCB inspection, where target sizes span from large solder bridges to sub-pixel pinholes. While the original YOLOv5 neck adopts a Path Aggregation Network (PANet), recent work shows that bi-directional pyramid designs with learnable fusion weights strengthen small-object representations and improve robustness to scale variation. In particular, Bi-Directional Feature Pyramid Networks (BiFPN) iteratively propagate information top-down and bottom-up, balancing low-level spatial detail with high-level semantics and yielding consistent gains over PANet-style necks in one-stage detectors [

23]. Journal studies report that replacing or augmenting PANet with BiFPN leads to higher precision and recall on small targets by avoiding attenuation of fine details during fusion [

24]. In PCB-focused research, lightweight YOLO variants that integrate BiFPN in the neck achieve superior accuracy on micro-defects, indicating that normalized, weighted cross-scale aggregation is particularly beneficial for tiny, low-contrast structures [

25]. Beyond PCB imagery, enhanced (augmented/weighted) BiFPN formulations further validate these trends in diverse vision tasks, demonstrating that learnable cross-scale weights can reduce information loss and emphasize discriminative cues at small scales [

26]. Guided by this evidence, the proposed model adopts a BiFPN neck to more effectively blend high-resolution detail and contextual semantics before detection, improving sensitivity to both macro-level faults and minute solder splashes. [

27,

28].

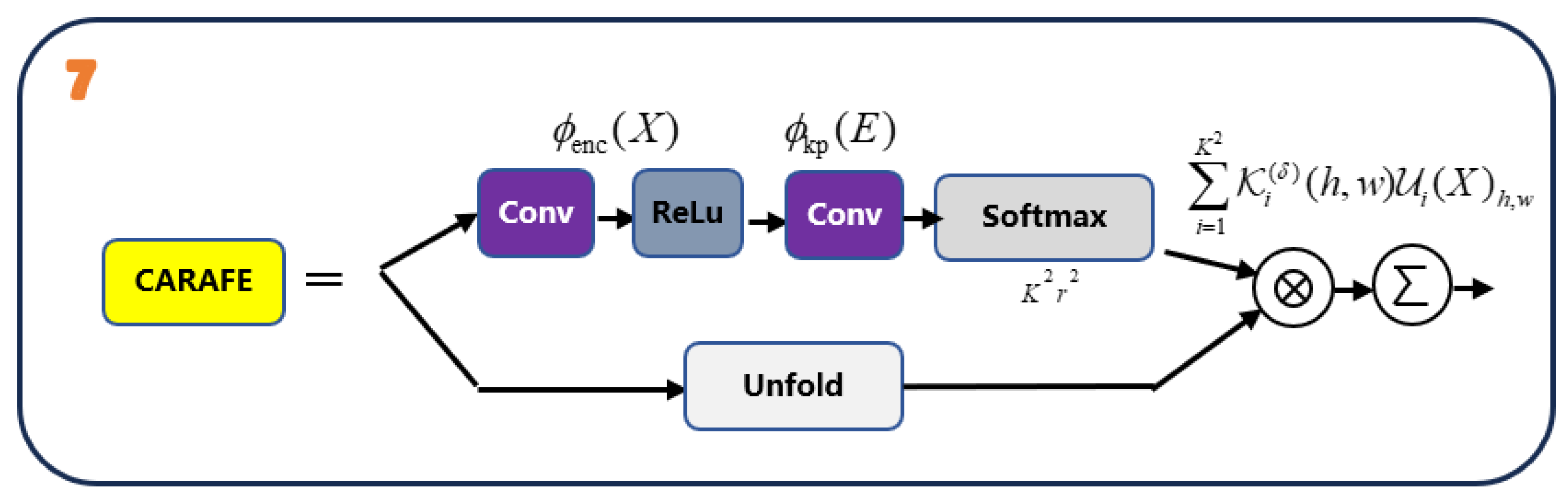

In addition to stronger feature fusion, refining the upsampling operator in the neck materially benefits small-defect detection. Fixed schemes (e.g., nearest-neighbor) can blur fine edges and attenuate weak responses, causing misses on hairline cracks or pinholes [

29]. A learnable alternative is Content-Aware ReAssembly of Features(CARAFE), which predicts position-specific reassembly kernels from local content and reconstructs high-resolution features with a larger effective receptive field [

30]. Unlike fixed interpolation, CARAFE preserves boundary and texture cues during upscaling and has been shown to improve one-stage detectors on cluttered scenes with numerous tiny targets [

31]. Recent journal studies report that inserting CARAFE into YOLO-style necks yields higher precision/recall on small objects while maintaining real-time feasibility due to the module’s lightweight design [

32]. Further evidence from remote-sensing benchmarks indicates that CARAFE reduces information loss and better aligns multi-scale features compared with naïve interpolation, boosting mAP for dense small targets [

33]. Guided by these results, the present YOLOv5-based architecture replaces nearest-neighbor upsampling with CARAFE at top-down pathways to retain minute PCB defect details during feature magnification and to strengthen the downstream detector’s sensitivity to thin, low-contrast flaws [

34].

While architectural enhancements increase capacity, data scarcity and class imbalance remain practical bottlenecks in PCB defect inspection. In early production or when new defect modes emerge, only a handful of labeled samples may exist, making fully supervised training prone to overfitting and poor generalization. Semi-supervised object detection (SSOD) addresses this by exploiting large pools of unlabeled imagery together with few labels, commonly through pseudo-labeling and consistency regularization in teacher–student schemes [

35,

36]. This setting aligns well with PCB lines, where acquiring images at scale is easy but fine-grained annotation is costly; leveraging unlabeled frames expands the distribution of backgrounds, lighting, and rare defects seen during training [

35,

37]. Recent journal studies demonstrate that filtering uncurated unlabeled sets and enforcing consistency across augmentations markedly improves pseudo-label quality and downstream detection, boosting mAP in low-label regimes [

35]. Practical SSOD variants also integrate adaptive thresholds or active selection to suppress noisy pseudo-boxes while retaining diverse positives, further stabilizing one-stage detectors [

38,

39]. Guided by these findings, a single-cycle self-training pipeline is adopted: a detector trained on labeled PCB images generates high-confidence pseudo-labels on unlabeled data; the labeled and pseudo-labeled samples are then mixed without ratio heuristics for retraining, improving recall of subtle anomalies while keeping computational overhead modest [

36,

40]. In effect, training on both labeled and pseudo-labeled data broadens coverage of rare, small, and low-contrast defects, reducing false negatives and improving robustness in deployment [

36,

40].

This study presents a task-aligned one-stage PCB defect detector by augmenting YOLOv5x with ECA, a lightweight DCN-lite, a BiFPN, and CARAFE upsampling. A single-cycle semi-supervised scheme (pseudo-labels with τ=0.60, IoU=0.50; random mixing with ground truth) expands effective training data. On PKU-PCB, supervised mAP@0.5 improves from 0.870 (baseline) to 0.910 with reduced complexity (63.9 M params; 175.5 GFLOPs vs. 86.2 M; 203.9). With semi-supervision, the baseline reaches 0.9115 mAP, while the proposed model attains 0.943 mAP, 94.4% precision, and 91.2% recall. Ablations confirm each module’s contribution and identify robust pseudo-label settings; comparisons with recent YOLO variants show favorable accuracy–efficiency trade-offs, yielding a label-efficient, deployment-ready AOI solution for tiny, low-contrast PCB defects.

4. Conclusions

A PCB defect detection approach is presented that enhances the one-stage YOLOv5 detector with multiple architectural improvements and a semi-supervised training paradigm. The proposed model, termed PCB-SSD (Single-Stage Detector), integrates ECA, a DCN-lite deformable convolution, a BiFPN multi-scale feature fusion neck, and CARAFE upsampling into the YOLOv5x framework, and is trained with an iterative self-training scheme to leverage unlabeled data. Comprehensive experiments on a challenging PCB defect dataset show that each modification contributes to improved performance. The final Full+SSL model achieved 94.3% mAP@0.5 on the test set with 94.4% precision and 91.2% recall, significantly outperforming the baseline YOLOv5x (87.0% mAP, 91.9% precision, 83.5% recall). This result not only surpasses the baseline by a wide margin but also exceeds the accuracy of several state-of-the-art YOLO variants in the literature, especially in detecting the tiny, low-contrast defects that challenge conventional methods. Key findings and contributions of our study include: (1) The addition of lightweight attention and feature-fusion modules (ECA, BiFPN) markedly improved the model’s ability to localize small defects by focusing on important channels and combining information across scales; (2) The DCN-lite added valuable flexibility to model irregular defect shapes, and CARAFE preserved fine detail, together leading to more precise defect localization; (3) The semi-supervised training strategy proved highly effective – by learning from a large pool of unlabeled PCB images, the detector’s recall of defects increased substantially (and precision also improved), enabling reliable detection even with very limited labeled data. For instance, our model can exceed 90% mAP with only a few dozen labeled images by leveraging hundreds of unlabeled samples via pseudo-labeling. These contributions represent a practical advancement for PCB inspection: a single-stage model that is both more accurate and more data-efficient than previous solutions.

In terms of practical implications, the improved defect detector offers tangible benefits for manufacturing quality control. Its high accuracy and low false-alarm rate mean it can serve as a dependable AOI system on the production line, reducing the burden on human inspectors and catching defects that might otherwise be overlooked. Moreover, the ability to train robustly with very few labeled examples but many unlabeled ones is particularly useful in real production environments – it alleviates the typical data bottleneck, since capturing a large volume of PCB images is relatively easy, but manually labeling them is time-consuming and costly. Using our approach, manufacturers could deploy an initial model with minimal annotation effort and continuously improve it by incorporating streams of new unlabeled images (with automatic self-labeling) from ongoing production. This facilitates an adaptable defect detection system that keeps learning as new boards or new defect types emerge, without requiring exhaustive labeling for each change. Additionally, the model’s one-stage design is computationally efficient (with moderate model size and FLOPs), making it feasible to run in real-time on modern industrial GPUs or even edge devices on the factory floor for in-situ inspection.

In conclusion, this work demonstrates a successful fusion of modern object detection enhancements and semi-supervised learning for PCB defect inspection. The proposed Full+SSL model significantly outperforms the prior state-of-the-art on the PCB dataset, especially in detecting challenging tiny defects, while using far fewer labeled examples. These results advance the development of smarter, more reliable automated PCB inspection systems. The methodology is general and could be extended to other electronic inspection or manufacturing quality-control tasks where labeling data is difficult – combining powerful one-stage detectors with unlabeled data is a promising direction for achieving high accuracy at low annotation cost. Future research may explore applying this approach to different defect datasets or integrating more advanced pseudo-label refinement strategies (e.g., adaptive thresholds or uncertainty estimation) to further improve performance. The findings are expected to stimulate further advances in data-efficient deep learning for industrial inspection, moving toward AI systems that continuously learn and improve with minimal human intervention.

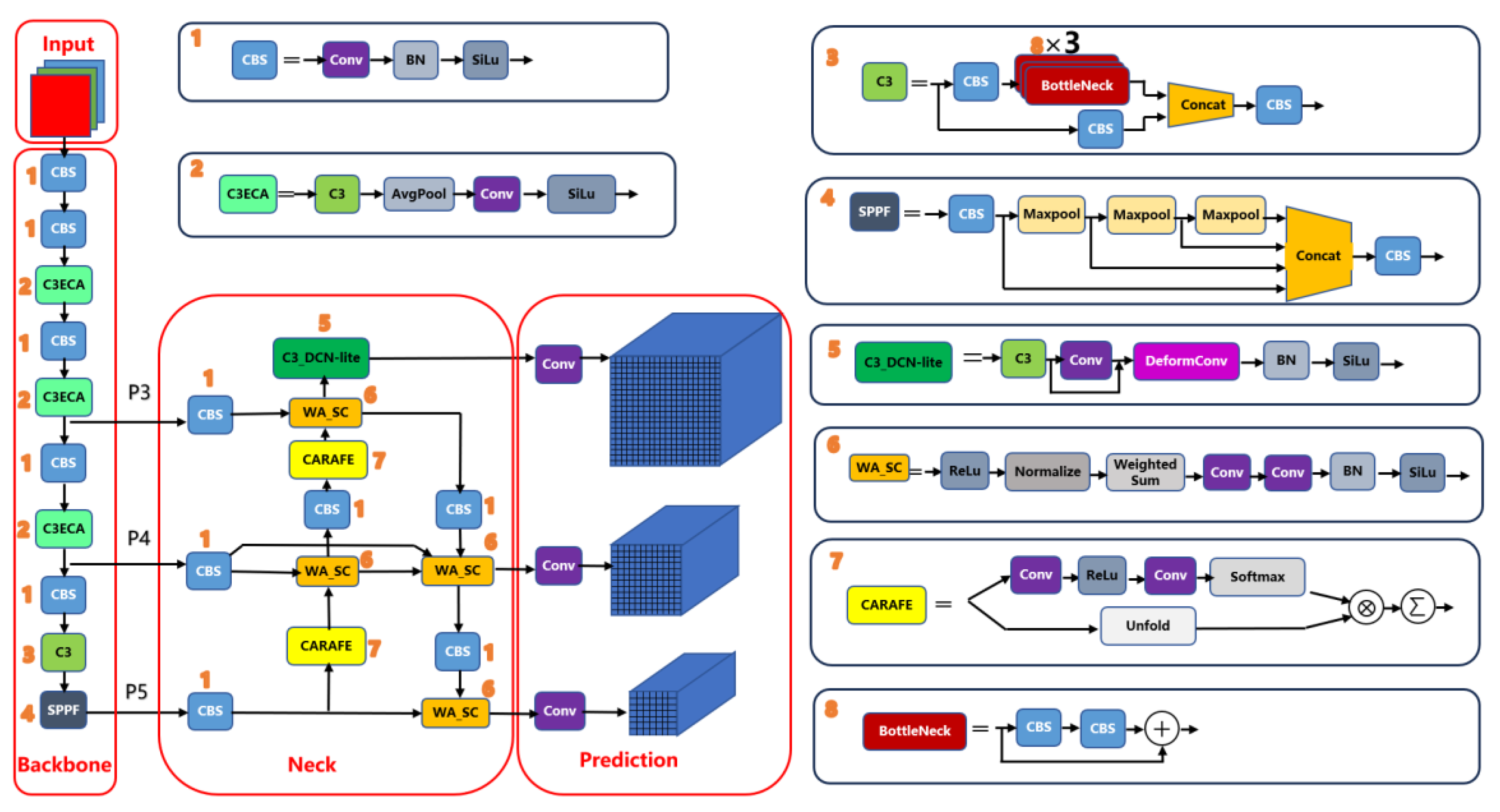

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the proposed YOLOv5x_ECA_DCN_BiFPN_CARAFE model. Starting from the YOLOv5x baseline, the design integrates four targeted modules to enhance multi-scale feature representation and sensitivity to small defects: (i) ECA in the C3 backbone blocks (green), (ii) a DCN-lite on the P3 (stride-8) feature path, (iii) a BiFPN-style bidirectional neck with learnable WeightedAdd fusion and Separable Convolution refinement (denoted “WA_SC”), and (iv) CARAFE content-aware upsampling in all top-down paths.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the proposed YOLOv5x_ECA_DCN_BiFPN_CARAFE model. Starting from the YOLOv5x baseline, the design integrates four targeted modules to enhance multi-scale feature representation and sensitivity to small defects: (i) ECA in the C3 backbone blocks (green), (ii) a DCN-lite on the P3 (stride-8) feature path, (iii) a BiFPN-style bidirectional neck with learnable WeightedAdd fusion and Separable Convolution refinement (denoted “WA_SC”), and (iv) CARAFE content-aware upsampling in all top-down paths.

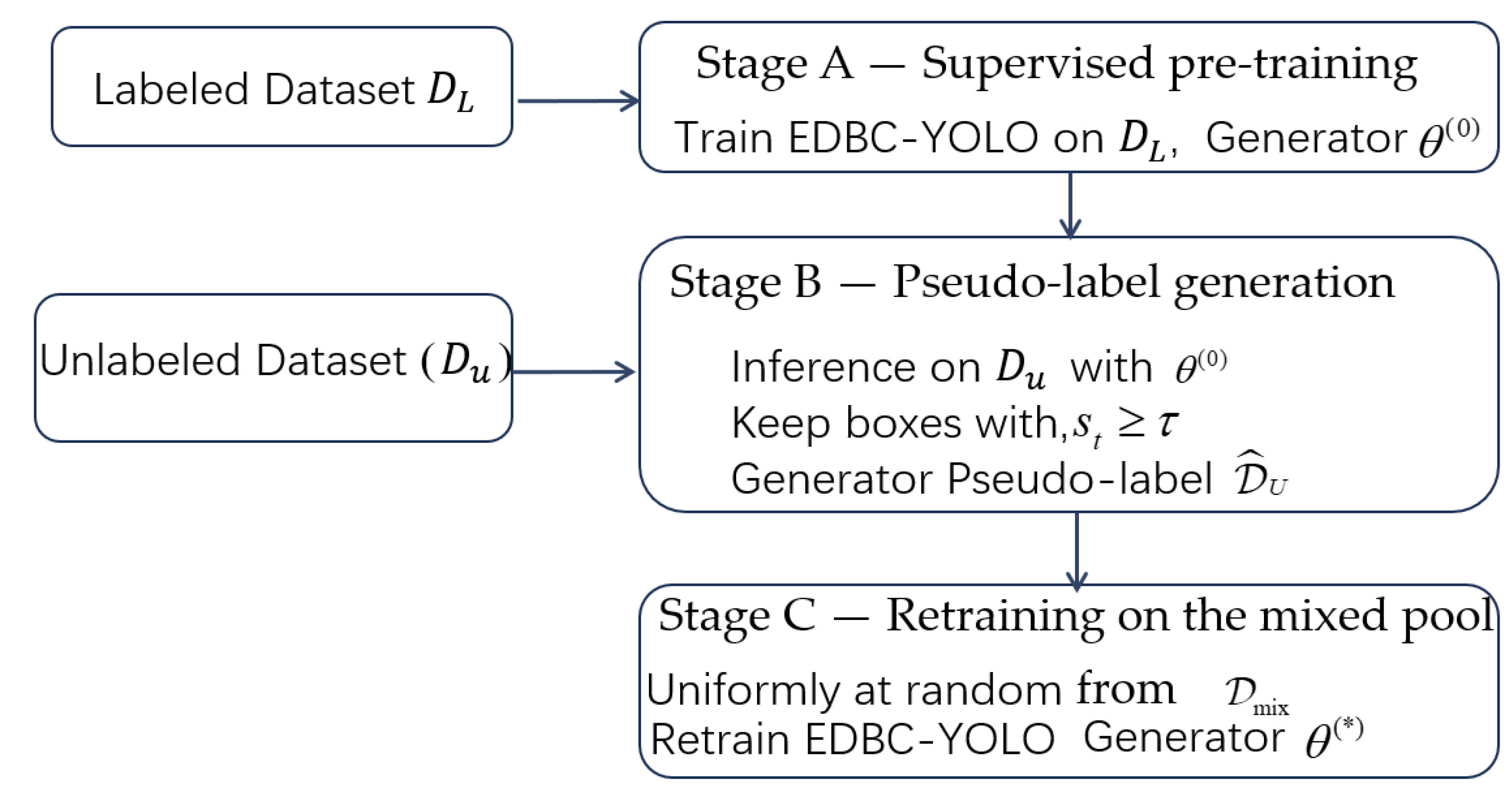

Figure 6.

Flowchart of the single-cycle semi-supervised training pipeline. .

Figure 6.

Flowchart of the single-cycle semi-supervised training pipeline. .

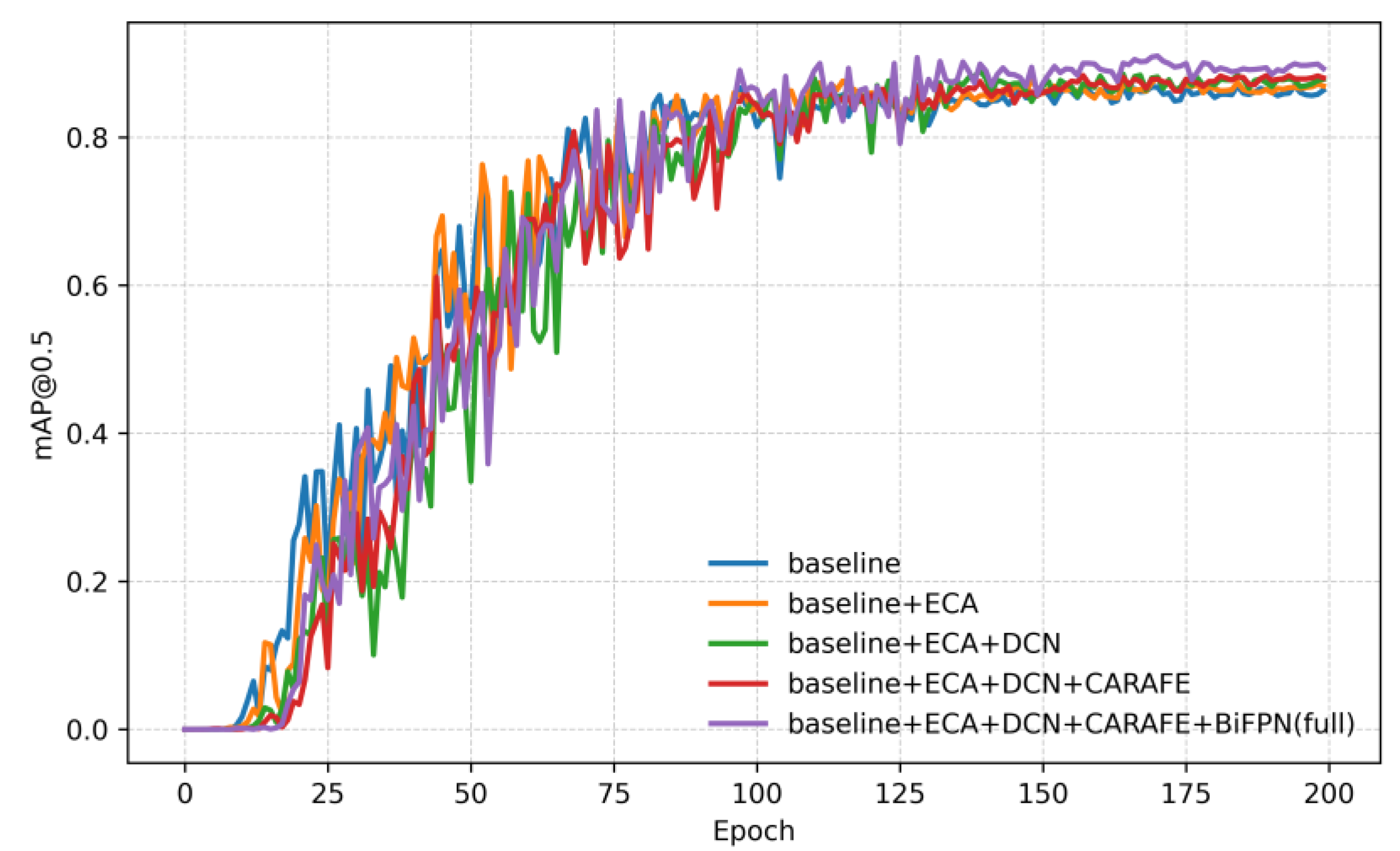

Figure 7.

Training curves showing mAP@0.5 vs. epoch for five architectures: the YOLOv5x baseline and variants with incremental modules (adding ECA, DCN-lite, CARAFE, and BiFPN). The Baseline converges to the lowest mAP (≈87%), while each added module yields a higher asymptote. The Full model (with all modules) reaches the highest mAP (~91%) and converges the fastest, with significant gains evident in early and mid training. These curves illustrate consistent benefits from the proposed modules at all stages of learning.

Figure 7.

Training curves showing mAP@0.5 vs. epoch for five architectures: the YOLOv5x baseline and variants with incremental modules (adding ECA, DCN-lite, CARAFE, and BiFPN). The Baseline converges to the lowest mAP (≈87%), while each added module yields a higher asymptote. The Full model (with all modules) reaches the highest mAP (~91%) and converges the fastest, with significant gains evident in early and mid training. These curves illustrate consistent benefits from the proposed modules at all stages of learning.

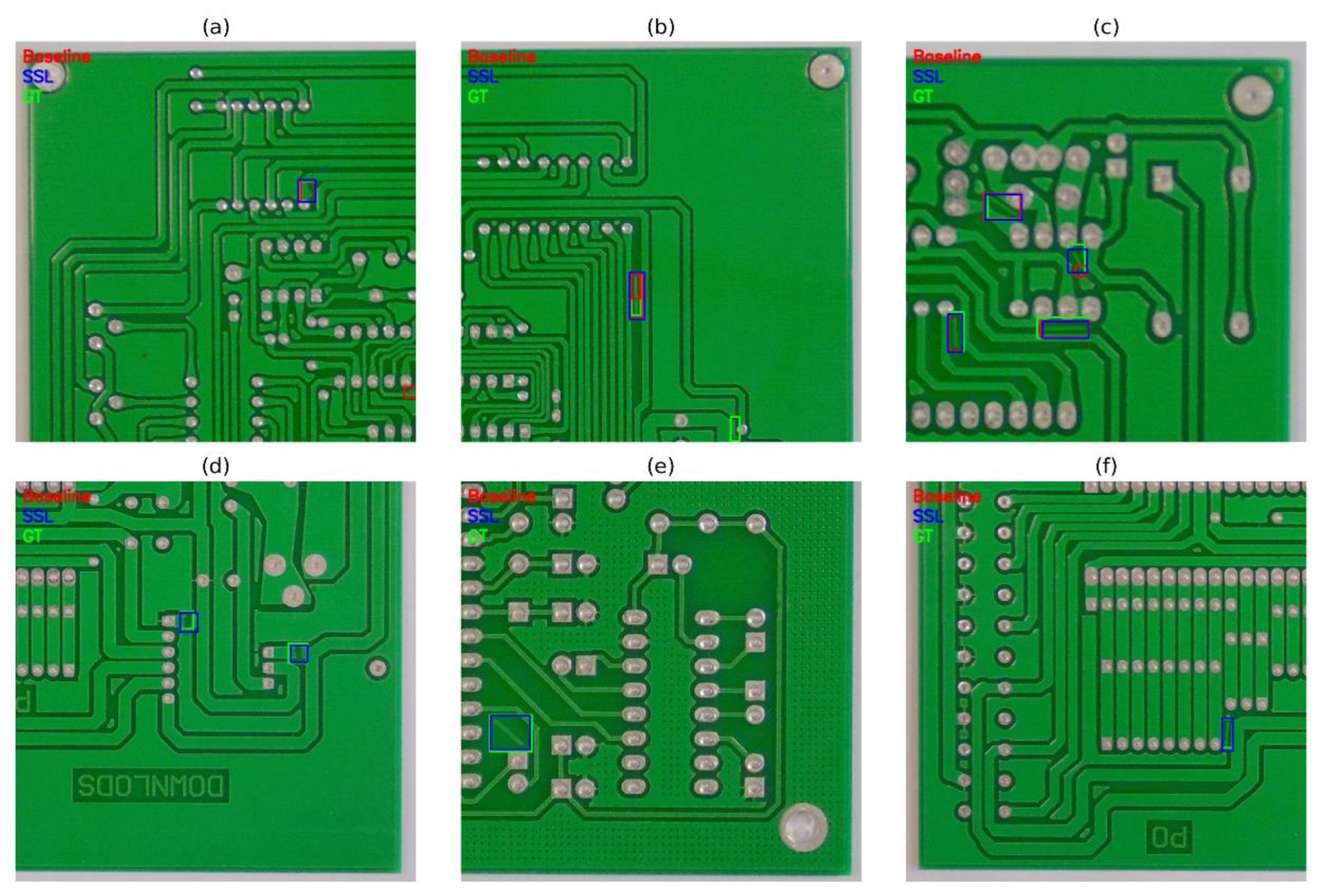

Figure 8.

Qualitative comparisons on PKU-PCB. (a) spur; (b) spurious copper; (c) spurious copper—baseline shows erroneous detections, while Full+SSL matches ground truth. (d) open circuit; (e) spurious copper; (f) spurious copper—baseline misses the defects, whereas Full+SSL detects them at the annotated locations. Colors: red = baseline, blue = Full+SSL, green = ground truth.

Figure 8.

Qualitative comparisons on PKU-PCB. (a) spur; (b) spurious copper; (c) spurious copper—baseline shows erroneous detections, while Full+SSL matches ground truth. (d) open circuit; (e) spurious copper; (f) spurious copper—baseline misses the defects, whereas Full+SSL detects them at the annotated locations. Colors: red = baseline, blue = Full+SSL, green = ground truth.

Table 1.

PKU-Dataset Splits and Usage Across Training Phases.

Table 1.

PKU-Dataset Splits and Usage Across Training Phases.

| Subset |

Images |

Purpose |

| Labeled train |

100 |

Used for Phase I supervised training (initial model) |

| Unlabeled pool |

1000 |

Used for Phase II pseudo-label generation in semi-supervised training |

| Validation |

600 |

Model selection, hyperparameter tuning, and early stopping |

| Test |

2134 |

Held-out evaluation of final performance (not used in training) |

Table 2.

Detection performance on the PKU-PCB test set. All models are trained only on the labeled split (100 images) in a fully supervised setting; no unlabeled data are used. Metrics include precision (P), recall (R), and mAP@0.5. Starting from the YOLOv5x baseline, modules are added cumulatively: +ECA (Efficient Channel Attention), +DCN-lite (deformable convolution), +CARAFE (content-aware reassembly upsampling), and +BiFPN (Bi-Directional Feature Pyramid Network). For reference, results for YOLOv8 and three recent YOLO-based detectors (anonymized as YOLOv9–YOLOv11) trained under the same setting are also reported. The Full model (all modules) attains the highest accuracy while using fewer parameters and GFLOPs than the baseline. Params (M) and GFLOPs are measured at input size 640×640.

Table 2.

Detection performance on the PKU-PCB test set. All models are trained only on the labeled split (100 images) in a fully supervised setting; no unlabeled data are used. Metrics include precision (P), recall (R), and mAP@0.5. Starting from the YOLOv5x baseline, modules are added cumulatively: +ECA (Efficient Channel Attention), +DCN-lite (deformable convolution), +CARAFE (content-aware reassembly upsampling), and +BiFPN (Bi-Directional Feature Pyramid Network). For reference, results for YOLOv8 and three recent YOLO-based detectors (anonymized as YOLOv9–YOLOv11) trained under the same setting are also reported. The Full model (all modules) attains the highest accuracy while using fewer parameters and GFLOPs than the baseline. Params (M) and GFLOPs are measured at input size 640×640.

| model |

stage |

P |

R |

mAP@0.5 |

Params |

GFLOPs |

| YOLOv5(baseline) |

supervised |

0.919 |

0.835 |

0.870 |

86.21 M |

203.86 |

| +ECA |

supervised |

0.906 |

0.844 |

0.880 |

86.21 M |

203.88 |

| +ECA+DCN |

supervised |

0.932 |

0.848 |

0.889 |

87.13 M |

215.69 |

| +ECA+DCN+ CARAFE |

supervised |

0.917 |

0.863 |

0.893 |

88.50 M |

217.50 |

| +ECA+DCN+ CARAFE +BiFPN (Full) |

supervised |

0.935 |

0.847 |

0.910 |

63.91 M |

175.51 |

| YOLOv8 |

supervised |

0.914 |

0.812 |

0.874 |

68.16 M |

258.15 |

| YOLOv9 |

supervised |

0.928 |

0.816 |

0.888 |

58.15 M |

192.70 |

| YOLOv10 |

supervised |

0.890 |

0.778 |

0.860 |

31.67 M |

171.05 |

| YOLOv11 |

supervised |

0.910 |

0.816 |

0.889 |

56.88 M |

195.48 |

Table 3.

Effect of SSL with 100 labeled images + 1000 unlabeled. The baseline YOLOv5x and the Full Arch model are compared after one stage of SSL training. Both models improve over their supervised counterparts, but the Full Arch yields higher precision, recall, and mAP.

Table 3.

Effect of SSL with 100 labeled images + 1000 unlabeled. The baseline YOLOv5x and the Full Arch model are compared after one stage of SSL training. Both models improve over their supervised counterparts, but the Full Arch yields higher precision, recall, and mAP.

| model |

P |

R |

mAP@0.5 |

| Baseline+SSL |

0.936 |

0.874 |

0.915 |

| Full Arch+ SSL |

0.944 |

0.912 |

0.943 |

Table 4.

Table 4. Class-wise detection results (AP@0.5, precision, recall) for the Baseline, Full, and Full+SSL models on the PCB test set. Results are shown for each of the six defect classes: open circuit, short circuit, mouse bite, spur, spurious copper, and pin-hole. The Full model outperforms the baseline in every class, and further improvements are achieved by the Full model with SSL – especially in recall (R), indicating more complete detection of defects. AP@0.5 is the Average Precision at IoU 0.5 for that class.

Table 4.

Table 4. Class-wise detection results (AP@0.5, precision, recall) for the Baseline, Full, and Full+SSL models on the PCB test set. Results are shown for each of the six defect classes: open circuit, short circuit, mouse bite, spur, spurious copper, and pin-hole. The Full model outperforms the baseline in every class, and further improvements are achieved by the Full model with SSL – especially in recall (R), indicating more complete detection of defects. AP@0.5 is the Average Precision at IoU 0.5 for that class.

| Defect Class |

baseline

P |

baseline

R |

Baseline

mAP@0.5 |

Full

P |

Full

R |

Full

mAP@0.5 |

Full +SSL

P |

Full +SSL

R |

Full +SSL

mAP@0.5 |

| open |

0.843 |

0.883 |

0.907 |

0.962 |

0.889 |

0.943 |

0.937 |

0.945 |

0.962 |

| short |

0.919 |

0.776 |

0.807 |

0.918 |

0.827 |

0.876 |

0.915 |

0.888 |

0.898 |

| mousebite |

0.954 |

0.834 |

0.881 |

0.967 |

0.800 |

0.895 |

0.975 |

0.881 |

0.941 |

| spur |

0.934 |

0.764 |

0.830 |

0.950 |

0.776 |

0.874 |

0.939 |

0.865 |

0.924 |

| copper |

0.885 |

0.828 |

0.840 |

0.882 |

0.833 |

0.904 |

0.948 |

0.916 |

0.948 |

| Pin-hole |

0.980 |

0.924 |

0.957 |

0.930 |

0.958 |

0.969 |

0.949 |

0.979 |

0.985 |