Submitted:

23 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. pH and Bacteria in Composting

3.2. Air and Bacteria in Composting

3.3. Temperature and Bacteria in Composting

3.4. Moisture and Bacteria in Composting

3.5. Nutrients and Bacteria in Composting

3.6. Electrical Conductivity (EC) and Bacteria in Composting

3.7. Material Size and Bacteria in Composting

3.8. Toxic Chemical and Bacteria in Composting

3.9. Radiation and Bacteria in Composting

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pawlak, K.; Kołodziejczak, M. The Role of Agriculture in Ensuring Food Security in Developing Countries: Considerations in the Context of the Problem of Sustainable Food Production. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umesha, S.; Manukumar, H.M.; Chandrasekhar, B. Sustainable Agriculture and Food Security. J. Agric. Biotech. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- Pinstrup-Andersen, P.; Pandya-Lorch, R. Food Security and Sustainable Use of Natural Resources: A 2020 Vision. Ecol. Econ. 1998, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anani, O.A.; Adetunji, C.O. Role of Pesticide Applications in Sustainable Agriculture. In Appl. Soil Chem. 2021, 235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, M.; Ibrahim, F.; Oyetola, S.O. Sustainable Agriculture in Relation to Problems of Soil Degradation and How to Amend Such Soils for Optimum Crop Production in Nigeria. Int. J. Res. Agric. Food Sci. 2018, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bardos, R.P.; Thomas, H.F.; Smith, J.W.; Harries, N.D.; Evans, F.; Boyle, R.; Howard, T.; Haslam, A. The development and use of sustainability criteria in SuRF-UK’s sustainable remediation framework. Sustainability. 2018, 10, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Gupta, S.P. Empowering Sustainable Agriculture: Harnessing AI for Enhanced Yields, Resource Efficiency, and Eco-Friendly Farming Practices. In AI and Ecological Change for Sustainable Development. Springer. 2025, 183–216. [Google Scholar]

- Das, U.; Ansari, M.A. The Nexus of Climate Change, Sustainable Agriculture and Farm Livelihood: Contextualizing Climate Smart Agriculture. Clim. Res. 2021, 84, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabinjo, O.; Opatola, S. Agriculture: A Pathway to Create a Sustainable Economy. Turk. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 2023, 4, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamakaula, Y. Sustainable Agriculture Practices: Economic, Ecological, and Social Approaches to Enhance Farmer Welfare and Environmental Sustainability. West Sci. Nat. Technol. 2024, 2, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, J.Z.; Dakina, I.; Modasir, H.L.; Monteza, M.G.; Ocor, J.D.; Orillo, E.P.E.; Fuentes, J. Sustainability of Agricultural Cooperatives: A Comprehensive Analysis. Preprint. 2023.

- Cozzolino, E.; Salluzzo, A.; Piano, L.D.; Tallarita, A.V.; Cenvinzo, V.; Cuciniello, A.; Caruso, G. Effects of the Application of a Plant-Based Compost on Yield and Quality of Industrial Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Grown in Different Soils. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayara, T.; Basheer-Salimia, R.; Hawamde, F.; Sánchez, A. Recycling of Organic Wastes through Composting: Process Performance and Compost Application in Agriculture. Agronomy 2020, 10(11), 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelbesa, W.A. Effect of Compost in Improving Soil Properties and Its Consequent Effect on Crop Production A Review. J. Nat. Sci. Res. 2021, 12(10), 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Erhart, E.; Hartl, W. Compost Use in Organic Farming. In Genetic Engineering, Biofertilisation, Soil Quality and Organic Farming; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 311–345. [Google Scholar]

- Manea, E.E.; Bumbac, C. Sludge Composting Is This a Viable Solution for Wastewater Sludge Management? Water. 2024, 16(16), 20734441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, X.; Bai, Z.; Chadwick, D.; Misselbrook, T.; Sommer, S.G.; Ma, L. Mitigation of Ammonia, Nitrous Oxide and Methane Emissions during Solid Waste Composting with Different Additives: A Meta-Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremaghani, A. Utilization of Organic Waste in Compost Fertilizer Production: Implications for Sustainable Agriculture and Nutrient Management. Law Econ. 2024, 18(2), 86–98. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Dong, Q.; Saleem, M.; Wu, X.; Wang, N.; Ding, S.; Gao, Z. Microbial-Based Detonation and Processing of Vegetable Waste for High Quality Compost Production at Low Temperatures. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 369, 133276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guardia, A.; Mallard, P.; Teglia, C.; Marin, A.; Le Pape, C.; Launay, M.; Petiot, C. Comparison of Five Organic Wastes Regarding Their Behaviour during Composting: Part 1, Biodegradability, Stabilization Kinetics and Temperature Rise. Waste Manag. 2010, 30(3), 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milinković, M.; Lalević, B.; Jovičić-Petrović, J.; Golubović-Ćurguz, V.; Kljujev, I.; Raičević, V. Biopotential of Compost and Compost Products Derived from Horticultural Waste—Effect on Plant Growth and Plant Pathogens’ Suppression. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2019, 121, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, R.; Suárez-Estrella, F.; Jurado, M.M.; López-González, J.A.; Estrella-González, M.J.; Toribio, A.J.; López, M.J. Sustainable Approach to the Control of Airborne Phytopathogenic Fungi by Application of Compost Extracts. Waste Manag. 2023, 171, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironov, V.; Shchelushkina, A.; Selitskaya, O.; Nikolaev, Y.; Merkel, A.; Zhang, S. Introducing Autochthonous Bacterium and Fungus Composition to Enhance the Phytopathogen-Suppressive Capacity of Composts against Clonostachys rosea, Penicillium solitum and Alternaria alternata In Vitro. Agronomy. 2023, 13(11), 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, H.; Islam, M. R.; Tasnim, N.; Roy, B. N.; Islam, M. S. Opportunities and challenges for establishing sustainable waste management. Trash or Treasure: Entrepreneurial Opportunities in Waste Management 2024, 79–123. [Google Scholar]

- Almansour, M.; Akrami, M. Towards Zero Waste: An In-Depth Analysis of National Policies, Strategies, and Case Studies in Waste Minimisation. Sustainability. 2024, 16(22), 10105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, I.R.; Maniruzzaman, K.M.; Dano, U.L.; AlShihri, F.S.; AlShammari, M.S.; Ahmed, S.M.S.; Alrawaf, T.I. Environmental sustainability impacts of solid waste management practices in the global South. IJERPH. 2022, 19, 12717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maalouf, A.; Mavropoulos, A. Reassessing Global Municipal Solid Waste Generation. Waste Manag. Res. 2023, 41(4), 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priya, A.K.; Alghamdi, H.M.; Kavinkumar, V.; Elwakeel, K.Z.; Elgarahy, A.M. Bioaerogels from Biomass Waste: An Alternative Sustainable Approach for Wastewater Treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 136994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazdani, S.; Lakzian, E. Conservation; Waste Reduction/Zero Waste. In Pragmatic Engineering and Lifestyle; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2023; pp. 131–152. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan-Ajao, O.Q.; Ajayi, O.G.; Omoniyi, T.E. Assessing the Potential of Anaerobic Digestion as a Sustainable Solution for Organic Waste Management and Renewable Energy Generation. Adeleke Univ. J. Eng. Technol. 2025, 8(1), 276–285. [Google Scholar]

- Taddese, S. Municipal Waste Disposal on Soil Quality. A Review. A Review. Acta Sci. Agric. 2019, 3(12), 09–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, E.J. Growing Unculturable Bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194(16), 4151–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, P.A.; Angert, E.R. Small but Mighty: Cell Size and Bacteria. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7(7), a019216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, D.; Satyanarayana, T. Diversity of hot environments and thermophilic microbes. In Thermophilic Microbes in Environmental and Industrial Biotechnology: Biotechnology of Thermophiles; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 3–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fenchel, T.; King, G.M.; Blackburn, T.H. Bacterial Biogeochemistry: The Ecophysiology of Mineral Cycling; Academic Press: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Saralov, A.I. Adaptivity of Archaeal and Bacterial Extremophiles. Microbiology. 2019, 88(4), 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gong, J.; Li, J.; Xin, Y.; Hao, Z.; Chen, C.; Li, J. Insights into Bacterial Diversity in Compost: Core Microbiome and Prevalence of Potential Pathogenic Bacteria. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 718, 137304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetgin, A.; Tümük, D.; Odek, M.; Bay, D.; Avşar, C.; Atun, M.; Gezerman, A.O. Exploring the Role of Bacterial Communities in the Composting Process. Med. Med. Chem. 2025, 2(1), 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Satyaprakash, M.; Nikitha, T.; Reddi, E.U.B.; Sadhana, B.; Vani, S.S. Phosphorous and Phosphate Solubilising Bacteria and Their Role in Plant Nutrition. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6(4), 2133–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuson, H.H.; Weibel, D.B. Bacteria–Surface Interactions. Soft Matter 2013, 9(17), 4368–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.C.; Wuertz, S. Bacteria and Archaea on Earth and Their Abundance in Biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17(4), 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayilara, M.S.; Olanrewaju, O.S.; Babalola, O.O.; Odeyemi, O. Waste Management through Composting: Challenges and Potentials. Sustainability. 2020, 12(11), 4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen, P.; Hultman, J.; Paulin, L.; Auvinen, P.; Romantschuk, M. Bacterial Diversity at Different Stages of the Composting Process. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.P.; Huang, G.H.; Lu, H.W.; He, L. Modeling of Substrate Degradation and Oxygen Consumption in Waste Composting Processes. Waste Manag. 2008, 28(8), 1375–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Xie, B.; Khan, R.; Shen, G. The Changes in Carbon, Nitrogen Components and Humic Substances during Organic-Inorganic Aerobic Co-Composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 271, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles-Castellano, A.B.; López, M.J.; López-González, J.A.; Suárez-Estrella, F.; Jurado, M.M.; Estrella-González, M.J.; Moreno, J. Comparative Analysis of Phytotoxicity and Compost Quality in Industrial Composting Facilities Processing Different Organic Wastes. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Wang, B.; Ji, Y.; Xu, F.; Zong, P.; Zhang, J.; Tian, Y. Thermal Decomposition of Castor Oil, Corn Starch, Soy Protein, Lignin, Xylan, and Cellulose during Fast Pyrolysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 278, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, A.L.; Karwal, M.; Kj, R.; Narwal, E. Aerobic composting versus anaerobic composting: Comparison and differences. Food Sci. Rep. 2021, 2, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ayilara, M.S.; Olanrewaju, O.S.; Babalola, O.O.; Odeyemi, O. Waste Management through Composting: Challenges and Potentials. Sustainability 2020, 12(11), 4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B Anielak, A. M.; Świderska-Dąbrowska, R.; Łomińska-Płatek, D.; Dąbrowski, T.; Piaskowski, K. Methods for Obtaining Humus Substances: Advantages and Disadvantages. Applied Sciences. 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neher, D.A.; Weicht, T.R.; Dunseith, P. Compost for Management of Weed Seeds, Pathogen, and Early Blight on Brassicas in Organic Farmer Fields. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2015, 39(1), 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, M.; Awasthi, M.K.; Chen, H.; Awasthi, S.K.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, Z. Measurement of Cow Manure Compost Toxicity and Maturity Based on Weed Seed Germination. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amuah, E.E.Y.; Fei-Baffoe, B.; Sackey, L.N.A.; Douti, N.B.; Kazapoe, R.W. A Review of the Principles of Composting: Understanding the Processes, Methods, Merits, and Demerits. Org. Agric. 2022, 12(4), 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padan, E.; Bibi, E.; Ito, M.; Krulwich, T.A. Alkaline pH Homeostasis in Bacteria: New Insights. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2005, 1717, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Munekata, P.E.; Dominguez, R.; Pateiro, M.; Saraiva, J.A.; Franco, D. Main Groups of Microorganisms of Relevance for Food Safety and Stability: General Aspects and Overall Description. In Innovative Technologies for Food Preservation. 2018, 53–107. [Google Scholar]

- Pinel, I.S.M.; Hankinson, P.M.; Moed, D.H.; Wyseure, L.J.; Vrouwenvelder, J.S.; van Loosdrecht, M.C. Efficient Cooling Tower Operation at Alkaline pH for the Control of Legionella pneumophila and Other Pathogenic Genera. Water Res. 2021, 197, 117047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanekar, P.P.; Kanekar, S.P. Alkaliphilic, Alkalitolerant Microorganisms. In Diversity and Biotechnology of Extremophilic Microorganisms from India; 2022; pp. 71–116. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Z.; Guo, J.; Wu, Z.; He, C.; Wang, L.; Bai, M.; Cheng, C. Nanomaterials Enabled Physicochemical Antibacterial Therapeutics: Toward the Antibiotic Free Disinfections. Small 2023, 19(50), 2303594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, N.; Liu, L. Microbial Response to Acid Stress: Mechanisms and Applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104(1), 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bååth, E.; Anderson, T.H. Comparison of Soil Fungal/Bacterial Ratios in a pH Gradient Using Physiological and PLFA-Based Techniques. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2003, 35(7), 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, A.; Vaidya, B.; Khatri, K.; Goyal, A.K.; Gupta, P.N.; Mahor, S.; Vyas, S.P. Targeted intracellular delivery of therapeutics: An overview. Pharmazie 2007, 62, 643–658. [Google Scholar]

- Slonczewski, J.L.; Fujisawa, M.; Dopson, M.; Krulwich, T.A. Cytoplasmic pH measurement and homeostasis in bacteria and archaea. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2009, 55, 1–317. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.; Yin, R.; Cheng, J.; Xu, Z.; Chen, J.; Gao, X.; Luo, W. Bacterial dynamics for gaseous emission and humification during bio-augmented composting of kitchen waste with lime addition for acidity regulation. Science of the Total Environment. 2022, 848, 157653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smårs, S.; Gustafsson, L.; Beck-Friis, B.; Jönsson, H. Improvement of the composting time for household waste during an initial low pH phase by mesophilic temperature control. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 84, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendt-Potthoff, K.; Koschorreck, M.; Ercilla, M.D.; España, J.S. Microbial activity and biogeochemical cycling in a nutrient-rich meromictic acid pit lake. Limnologica 2012, 42, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundberg, C.; Smårs, S.; Jönsson, H. Low pH as an inhibiting factor in the transition from mesophilic to thermophilic phase in composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2004, 95, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bascón, M.; Díez-Gutiérrez, M.A.; Hernández-Navarro, S.; Corrêa-Guimarães, A.; Navas-Gracia, L.M.; Martín-Gil, J. Use of potato peelings in composting techniques: A high-priority and low-cost alternative for environmental remediation. Soil Dyn. Plant 2008, 72–89. [Google Scholar]

- Muscolo, A.; Papalia, T.; Settineri, G.; Mallamaci, C.; Jeske-Kaczanowska, A. Are raw materials or composting conditions and time that most influence the maturity and/or quality of composts? Comparison of obtained composts on soil properties. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim, K.; Soudi, B.; Boukhari, S.; Perissol, C.; Roussos, S.; Thami Alami, I. Composting parameters and compost quality: A literature review. Org. Agric. 2018, 8, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Selvam, A.; Wong, J.W.C. Influence of lime on struvite formation and nitrogen conservation during food waste composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 217, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insam, H.; De Bertoldi, M. Microbiology of the Composting Process. In Waste Management Series. 2007, 8, 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Njokweni, S.G.; Steyn, A.; Botes, M.; Viljoen-Bloom, M.; van Zyl, W.H. Potential Valorization of Organic Waste Streams to Valuable Organic Acids through Microbial Conversion: A South African Case Study. Catalysts 2021, 11, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, Y.R.; Li, L.; Liu, J.; Butler, D. Stepwise pH Control to Promote Synergy of Chemical and Biological Processes for Augmenting Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production from Anaerobic Sludge Fermentation. Water Research. 2019, 155, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddadin, M.S.; Haddadin, J.; Arabiyat, O.I.; Hattar, B. Biological Conversion of Olive Pomace into Compost by Using Trichoderma harzianum and Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Bioresource Technology 2009, 100, 4773–4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nozhevnikova, A.N.; Mironov, V.V.; Botchkova, E.A.; Litti, Y.V.; Russkova, Y.I. Composition of a Microbial Community at Different Stages of Composting and the Prospects for Compost Production from Municipal Organic Waste. Applied Biochemistry and Microbiology 2019, 55, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, D.; Qi, C.; Li, G.; Yuan, J. Effects of Oxygen Levels on Maturity, Humification, and Odor Emissions during Chicken Manure Composting. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 369, 133326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbe, M.A.; Nazhad, M.; Sánchez, C. Composting as a Way to Convert Cellulosic Biomass and Organic Waste into High-Value Soil Amendments: A Review. BioResources 2010, 5, 2808–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayilara, M.S.; Olanrewaju, O.S.; Babalola, O.O.; Odeyemi, O. Waste Management through Composting: Challenges and Potentials. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puyuelo, B.; Gea, T.; Sánchez, A. A New Control Strategy for the Composting Process Based on the Oxygen Uptake Rate. Chemical Engineering Journal 2010, 165, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P.; Koyama, M.; Nakasaki, K. Effects of Oxygen Supply Rate on Organic Matter Decomposition and Microbial Communities during Composting in a Controlled Lab-Scale Composting System. Waste Management 2022, 153, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argun, Y.A.; Karacali, A.; Calisir, U.; Kilinc, N. Composting as a Waste Management Method. Journal of International Environmental Application and Science 2017, 12, 244–255. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Clark, O.G.; Leonard, J.J. Influence of Free Air Space on Microbial Kinetics in Passively Aerated Compost. Bioresource Technology 2009, 100, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wei, Y.; Kou, J.; Han, Z.; Shi, Q.; Liu, L.; Sun, Z. Improve Spent Mushroom Substrate Decomposition, Bacterial Community and Mature Compost Quality by Adding Cellulase during Composting. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 299, 126928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, A. L.; Karwal, M.; Dutta, D.; Mishra, R. P. Composting: phases and factors responsible for efficient and improved composting. Agriculture and Food: e-Newsletter. 2021, 1, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggieri, L.; Gea, T.; Artola, A.; Sánchez, A. Air Filled Porosity Measurements by Air Pycnometry in the Composting Process: A Review and a Correlation Analysis. Bioresource Technology 2009, 100, 2655–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, A.L.; Karwal, M.; Dutta, D.; Mishra, R.P. Composting: Phases and Factors Responsible for Efficient and Improved Composting. Agriculture and Food: e-Newsletter 2021, 1, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Azim, K.; Soudi, B.; Boukhari, S.; Perissol, C.; Roussos, S.; Thami Alami, I. Composting Parameters and Compost Quality: A Literature Review. Organic Agriculture 2018, 8, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, D.; Qi, C.; Li, G.; Yuan, J. Effects of oxygen levels on maturity, humification, and odor emissions during chicken manure composting. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2022, 369, 133326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. K.; Wang, M. H. S.; Cardenas Jr, R. R.; Sabiani, N. H. M.; Yusoff, M. S.; Hassan, S. H.; Hung, Y. T. Composting processes for disposal of municipal and agricultural solid wastes. Solid Waste Engineering and Management 2022, 1, 399–523. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, F.; O’Neill, T.; Rynk, R.; Gilbert, J.; Wisbaum, S.; Halbach, T. Passively Aerated Composting Methods, Including Turned Windrows. In The Composting Handbook. 2022, 159–196. [Google Scholar]

- Nikaeen, M.; Nafez, A.H.; Bina, B.; Nabavi, B.F.; Hassanzadeh, A. Respiration and Enzymatic Activities as Indicators of Stabilization of Sewage Sludge Composting. Waste Management. 2015, 39, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harindintwali, J.D.; Zhou, J.; Yu, X. Lignocellulosic Crop Residue Composting by Cellulolytic Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria: A Novel Tool for Environmental Sustainability. Science of the Total Environment. 2020, 715, 136912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartini, S.; Hidayat, N.; Rohma, N.A.; Paul, R.; Pangestuti, M.B.; Utami, R.N.; Melville, L. Sustainable Strategies for Anaerobic Digestion of Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunches in Indonesia: A Review. International Journal of Sustainable Energy. 2022, 41, 2044–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stentiford, E. Composting and Compost. Environmental Science and Technology. 2013, 37, 187–204. [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi, M.K.; Mahar, A.; Ali, A.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z. Component Technologies for Municipal Solid Waste Management. In Municipal Solid Waste Management in Developing Countrie. 2016, 75–110. [Google Scholar]

- Yasmin, N.; Jamuda, M.; Panda, A.K.; Samal, K.; Nayak, J.K. Emission of Greenhouse Gases (GHGs) during Composting and Vermicomposting: Measurement, Mitigation, and Perspectives. Energy Nexus. 2022, 7, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, R. S.; Shah, A. N.; Tahir, M. B.; Umair, M.; Nawaz, M.; Ali, A.; Assiri, M. A. Recent trends and advances in additive-mediated composting technology for agricultural waste resources: A comprehensive review. ACS omega 2024, 9, 8632–8653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaras, A.; Arslanoglu, H. Preparation and Characterization of Novel Iron (III) Hydroxide Paper Mill Sludge Composite Adsorbent for Chromium Removal. Sakarya University Journal of Science. 2019, 23, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Kim, I.H.; Lee, T.J.; Kim, K.Y.; Kim, D. Effect of Temperature on Bacterial Emissions in Composting of Swine Manure. Waste Management. 2014, 34, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyatake, F.; Iwabuchi, K. Effect of High Compost Temperature on Enzymatic Activity and Species Diversity of Culturable Bacteria in Cattle Manure Compost. Bioresource Technology. 2005, 96, 1821–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekunle, I.M.; Adekunle, A.A.; Akintokun, A.K.; Akintokun, P.O.; Arowolo, T.A. Recycling of organic wastes through composting for land applications: A Nigerian experience. Waste Manag. Res. 2011, 29, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, A.; Belguith, K.; Jedidi, N.; Cherif, A.; Cherif, M.; Boudabous, A. Microbial characterization during composting of municipal solid waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2001, 80, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringel-Scaia, V.M.; Qin, Y.; Thomas, C.A.; Huie, K.E.; McDaniel, D.K.; Eden, K.; Allen, I.C. Maternal influence and murine housing confound impact of NLRP1 inflammasome on microbiome composition. J. Innate Immun. 2019, 11, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finore, I.; Feola, A.; Russo, L.; Cattaneo, A.; Di Donato, P.; Nicolaus, B.; Romano, I. Thermophilic bacteria and their thermozymes in composting processes: A review. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourti, O.; Jedidi, N.; Hassen, A. Behaviour of main microbiological parameters and of enteric microorganisms during the composting of municipal solid wastes and sewage sludge in a semi-industrial composting plant. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2008, 4, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eamens, G.J.; Dorahy, C.J.; Muirhead, L.; Enman, B.; Pengelly, P.; Barchia, I.M.; Cooper, K. Bacterial survival studies to assess the efficacy of static pile composting and above ground burial for disposal of bovine carcases. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 110, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, N.J. Bacterial membranes: The effects of chill storage and food processing. An overview. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002, 79, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepesteur, M. Human and livestock pathogens and their control during composting. Critical reviews in environmental science and technology. 2022, 52, 1639–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashenafi, M. Thermal effects in food microbiology. In Thermal Food Processing: New Technologies and Quality; 2012; pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Heinlin, J.; Morfill, G.; Landthaler, M.; Stolz, W.; Isbary, G.; Zimmermann, J.L.; Karrer, S. Plasma medicine: Possible applications in dermatology. JDDG J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2010, 8, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieille, C.; Zeikus, G.J. Hyperthermophilic enzymes: Sources, uses, and molecular mechanisms for thermostability. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2001, 65, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Kang, C.; Niu, L.; Zhao, D.; Li, K.; Bai, Y. Antibacterial activity and a membrane damage mechanism of plasma-activated water against Pseudomonas deceptionensis CM2. LWT. 2018, 96, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Han, S.; Lin, Y. Role of microbes and microbial dynamics during composting. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2023, 169–220. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, P.; Edwards-Jones, G.; Jones, D.L. In-vessel cocomposting of green waste with biosolids and paper waste. Compost Sci. Util. 2007, 15, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, F.C. Composting of municipal solid waste and its components. In Microbiology of Solid Waste. 2020, 115–154. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbe, M.A.; Nazhad, M.; Sánchez, C. Composting as a way to convert cellulosic biomass and organic waste into high-value soil amendments: A review. BioResources 2010, 5, 2808–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horve, P.F.; Lloyd, S.; Mhuireach, G.A.; Dietz, L.; Fretz, M.; MacCrone, G.; Ishaq, S.L. Building upon current knowledge and techniques of indoor microbiology to construct the next era of theory into microorganisms, health, and the built environment. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2020, 30, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Koestler, R.J.; Warscheid, T.; Katayama, Y.; Gu, J.D. Microbial deterioration and sustainable conservation of stone monuments and buildings. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiquia, S.M.; Tam, N.F.Y.; Hodgkiss, I.J. Microbial activities during composting of spent pig-manure sawdust litter at different moisture contents. Bioresour. Technol. 1996, 55, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, W.; Kroukamp, O.; McKelvie, J.; Korber, D.R.; Wolfaardt, G.M. Microbial metabolism in bentonite clay: Saturation, desiccation and relative humidity. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 129, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artola, A.; Barrena, R.; Font, X.; Gabriel, D.; Gea, T.; Mudhoo, A.; Sánchez, A. Composting from a sustainable point of view: Respirometric indices as a key parameter. Dyn. Soil Dyn. Plant 2009, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Hu, J.; Shan, Y.; Yin, Q.; Le, Y. Effects of turning frequency on the reduction, humification and stabilization of organic matter during composting: Laboratory-scale research. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2014, 23, 2381–2387. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, N.; Onwusogh, U.; Mackey, H. R. Exploring the metabolic features of purple non-sulfur bacteria for waste carbon utilization and single-cell protein synthesis. Biomass conversion and biorefinery. 2024, 14, 12653–12672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Li, G.; Jiang, T.; Schuchardt, F.; Chen, T.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, Y. Effect of aeration rate, C/N ratio and moisture content on the stability and maturity of compost. Bioresource technology. 2012, 112, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, A.L.; Karwal, M.; Dutta, D.; Mishra, R.P. Composting: Phases and factors responsible for efficient and improved composting. Agric. Food e-Newsletter. 2021, 1, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperband, L.R. Composting: Art and science of organic waste conversion to a valuable soil resource. Lab. Med. 2000, 31, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colmenares, J.C.; Varma, R.S.; Lisowski, P. Sustainable hybrid photocatalysts: Titania immobilized on carbon materials derived from renewable and biodegradable resources. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 5736–5750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasirajan, S.; Ngouajio, M. Polyethylene and biodegradable mulches for agricultural applications: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 501–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, R.; Zabaniotou, A.A.; Skoulou, V. Synergistic effects between lignin and cellulose during pyrolysis of agricultural waste. Energy Fuels. 2018, 32, 8420–8430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbe, M.A.; Nazhad, M.; Sánchez, C. Composting to convert cellulosic biomass and organic waste into high-value soil amendments: A review. BioResources. 2010, 5, 2808–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modderman, C. Composting with or without Additives. In Animal Manure: Production, Characteristics, Environmental Concerns, and Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; Volume 67. [Google Scholar]

- Azim, K.; Soudi, B.; Boukhari, S.; Perissol, C.; Roussos, S.; Thami Alami, I. Composting Parameters and Compost Quality: A Literature Review. Org. Agric. 2018, 8, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Gao, H.; Li, J.; Pang, F.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, Y.; He, Z. Losses and transformations of nitrogen at low value of C/N ratio compost. Russian Agricultural Sciences. 2019, 45, 543–549. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, C.H.; Richards, K.G. The Continuing Challenge of Nitrogen Loss to the Environment: Environmental Consequences and Mitigation Strategies. Dyn. Soil Dyn. Plant. 2008, 2, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Azis, F.A.; Choo, M.; Suhaimi, H.; Abas, P.E. The Effect of Initial Carbon to Nitrogen Ratio on Kitchen Waste Composting Maturity. Sustainability. 2023, 15, 6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietz, D.N.; Haynes, R.J. Effects of Irrigation-Induced Salinity and Sodicity on Soil Microbial Activity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2003, 35, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Guo, D.; He, L.; Liu, F.; Yu, J. Electrical Conductivity of Nutrient Solution Influenced Photosynthesis, Quality, and Antioxidant Enzyme Activity of Pakchoi (Brassica campestris L. ssp. chinensis) in a Hydroponic System. PLoS ONE. 2018, 13, e0202090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin, D. L.; Yemoto, K. Salinity: Electrical conductivity and total dissolved solids. J. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. 2020, 84, 1442–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M. N.; Anuar, M. I.; Abd Aziz, N.; Murdi, A. A. Function and application of Soil Electrical Conductivity (EC) sensor in agriculture: A Review. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, S.P. Soil Properties Influencing Apparent Electrical Conductivity: A Review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2005, 46, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.A.; Jones, S.B.; Wraith, J.M.; Or, D.; Friedman, S.P. A Review of Advances in Dielectric and Electrical Conductivity Measurement in Soils Using Time Domain Reflectometry. Vadose Zone J. 2003, 2, 444–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengasamy, P. Soil Processes Affecting Crop Production in Salt-Affected Soils. Funct. Plant Biol. 2010, 37, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietz, D.N.; Haynes, R.J. Effects of Irrigation-Induced Salinity and Sodicity on Soil Microbial Activity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2003, 35, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, D.F.; Timmer, V.R. Fertilizer-Induced Changes in Rhizosphere Electrical Conductivity: Relation to Forest Tree Seedling Root System Growth and Function. New For. 2005, 30, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalfitano, C.A.; Del Vacchio, L.D.V.; Somma, S.; Cuciniello, A.C.; Caruso, G. Effects of Cultural Cycle and Nutrient Solution Electrical Conductivity on Plant Growth, Yield and Fruit Quality of ‘Friariello’ Pepper Grown in Hydroponics. Hortic. Sci. 2017, 44, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, N.S.; Al-Daood, B.H. Response of Asiatic Lily to Nutrient Solution Recycling in a Closed Soilless Culture. Acta Hortic. 2005, 697, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y. L.; Taylor, A. B.; McMANUS, H. A. Evolution of the life cycle in land plants. Syst. Evolution. 2012, 50, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherubini, F.; Bargigli, S.; Ulgiati, S. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Waste Management Strategies: Landfilling, Sorting Plant and Incineration. Energy. 2009, 34, 2116–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, A. L.; Ladha, J. K.; Pathak, H.; Padre, A. T.; Dawe, D.; Gupta, R. K. Yield and soil nutrient changes in a long-term rice-wheat rotation in India. SSSAJ. 2002, 66, 162–170. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit, R.E. Organic Matter, Humus, Humate, Humic Acid, Fulvic Acid and Humin: Their Importance in Soil Fertility and Plant Health. CTI Res. 2004, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sultanbawa, F.; Sultanbawa, Y. Mineral nutrient-rich plants–Do they occur? Appl. Food Res. 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumus, İ.; Şeker, C. Influence of Humic Acid Applications on Modulus of Rupture, Aggregate Stability, Electrical Conductivity, Carbon and Nitrogen Content of a Crusting Problem Soil. Solid Earth. 2015, 6, 1231–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naorem, A.; Jayaraman, S.; Dang, Y. P.; Dalal, R. C.; Sinha, N. K.; Rao, C. S.; Patra, A. K. Soil constraints in an arid environment—challenges, prospects, and implications. Agronomy. 2023, 13, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Badiyal, A.; Dhiman, S.; Bala, J.; Walia, A. Exploring Halophiles for Reclamation of Saline Soils: Biotechnological Interventions for Sustainable Agriculture. J. Basic Microbiol. 2025, e70048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, S.; Abrahamsen, P.; Petersen, C.T.; Styczen, M. Daisy: Model Use, Calibration, and Validation. Trans. ASABE. 2012, 55, 1317–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin, D.L.; Lesch, S.M. Apparent Soil Electrical Conductivity Measurements in Agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2005, 46, 11–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, N. R.; Costa, J. L. Delineation of management zones with soil apparent electrical conductivity to improve nutrient management. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2013, 99, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, R.M.A.; Serralheiro, R.P. Soil Salinity: Effect on Vegetable Crop Growth. Horticulturae. 2017, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismayilov, A. I.; Mamedov, A. I.; Fujimaki, H.; Tsunekawa, A.; Levy, G. J. Soil salinity type effects on the relationship between the electrical conductivity and salt content for 1: 5 soil-to-water extract. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre-Valero, J.F.; Gonzalez-Ortega, M.J.; Martinez-Alvarez, V.; Gallego-Elvira, B.; Conesa-Jodar, F.J.; Martin-Gorriz, B. Revaluing the Nutrition Potential of Reclaimed Water for Irrigation in Southeastern Spain. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 218, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.K.; Yadav, K.D. Assessment of the Effect of Particle Size and Selected Physico-Chemical and Biological Parameters on the Efficiency and Quality of Composting of Garden Waste. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107925–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Liao, J.; Abass, O.K.; Liu, L.; Huang, X.; Wei, L.; Liu, C. Effects of Compost Characteristics on Nutrient Retention and Simultaneous Pollutant Immobilization and Degradation during Co-Composting Process. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 275, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tognetti, C.; Mazzarino, M.J.; Laos, F. Improving the Quality of Municipal Organic Waste Compost. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, R.J.; Belyaeva, O.N.; Zhou, Y.F. Particle Size Fractionation as a Method for Characterizing the Nutrient Content of Municipal Green Waste Used for Composting. Waste Manag. 2015, 35, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voberkova, S.; Maxianová, A.; Schlosserová, N.; Adamcová, D.; Vršanská, M.; Richtera, L.; … Vaverková, M.D. Food Waste Composting Is It Really So Simple as Stated in Scientific Literature? A Case Study. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 723, 138202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priya, A.K.; Gnanasekaran, L.; Dutta, K.; Rajendran, S.; Balakrishnan, D.; Soto-Moscoso, M. Biosorption of Heavy Metals by Microorganisms: Evaluation of Different Underlying Mechanisms. Chemosphere. 2022, 307, 135957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayilara, M.S.; Olanrewaju, O.S.; Babalola, O.O.; Odeyemi, O. Waste Management through Composting: Challenges and Potentials. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, H.G.; Thuy, B.T.P.; Lin, C.; Vo, D.V.N.; Tran, H.T.; Bahari, M.B.; Vu, C.T. The Nitrogen Cycle and Mitigation Strategies for Nitrogen Loss during Organic Waste Composting: A Review. Chemosphere. 2022, 300, 134514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wei, Z.; Mohamed, T.A.; Zheng, G.; Qu, F.; Wang, F.; Song, C. Lignocellulose Biomass Bioconversion during Composting: Mechanism of Action of Lignocellulase, Pretreatment Methods and Future Perspectives. Chemosphere, 2022, 286, 131635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshabib, M.; Onaizi, S. A. Effects of surface active additives on the enzymatic treatment of phenol and its derivatives: a mini review. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2019, 5, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, N.; Ponti, F.; Punta, C.; Candiani, G. Effect of UV Irradiation and TiO2-Photocatalysis on Airborne Bacteria and Viruses: An Overview. Materials. 2021, 14, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, D.; Upadhyay, R.; Singh, C. S.; Boruah, N.; Mandal, N.; Chatterjee, A. Mitigation of X-ray induced DNA dadamagend expression of DNA-repair genes by antioxidative Potentilla fulgens root extract and its ethyl-acetate fraction in mammalian cells. Mutagenesis. 2021, 36, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasar, A.; Tabinda, A.B. Anaerobic Treatment of Industrial Wastewater by UASB Reactor Integrated with Chemical Oxidation Processes: An Overview. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2010, 19, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Zhang, L. Effects of Radiation with Diverse Spectral Wavelengths on Photodegradation during Green Waste Composting. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 826, 154166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zhang, L. Responses of Microorganisms to Different Wavelengths of Light Radiation during Green Waste Composting. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 171021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Sun, W.; Ao, X. Bacterial Inactivation, DNA Damage, and Faster ATP Degradation Induced by Ultraviolet Disinfection. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2020, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cui, H.; Shi, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, Z. Relationship between Bacterial Diversity and Environmental Parameters during Composting of Different Raw Materials. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 198, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M.; Jones, D.L. Critical Evaluation of Municipal Solid Waste Composting and Potential Compost Markets. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 4301–4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen, P.; Hultman, J.; Paulin, L.; Auvinen, P.; Romantschuk, M. Bacterial Diversity at Different Stages of the Composting Process. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danon, M.; Franke-Whittle, I.H.; Insam, H.; Chen, Y.; Hadar, Y. Molecular Analysis of Bacterial Community Succession during Prolonged Compost Curing. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008, 65, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neher, D.A.; Weicht, T.R.; Bates, S.T.; Leff, J.W.; Fierer, N. Changes in Bacterial and Fungal Communities across Compost Recipes, Preparation Methods, and Composting Times. PLoS ONE. 2013, 8, e79512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishan, I.; Kanekar, H.; Kalamdhad, A.S. Microbial Population, Stability and Maturity Analysis of Rotary Drum Composting of Water Hyacinth. Biologia. 2014, 69, 1303–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles-Castellano, A.B.; López-González, J.A.; Jurado, M.M.; Estrella-González, M.J.; Suárez-Estrella, F.; López, M.J. Compost Quality and Sanitation on Industrial Scale Composting of Municipal Solid Waste and Sewage Sludge. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amuah, E.E.Y.; Fei-Baffoe, B.; Sackey, L.N.A.; Douti, N.B.; Kazapoe, R.W. A Review of the Principles of Composting: Understanding the Processes, Methods, Merits, and Demerits. Org. Agric. 2022, 12, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergola, M.; Persiani, A.; Palese, A.M.; Di Meo, V.; Pastore, V.; D’Adamo, C.; Celano, G. Composting: The Way for Sustainable Agriculture. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 123, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim, K.; Soudi, B.; Boukhari, S.; Perissol, C.; Roussos, S.; Thami Alami, I. Composting Parameters and Compost Quality: A Literature Review. Org. Agric. 2018, 8, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.I.; Beheary, M.S.; Salem, E.M. Monitoring of Microbial Populations and Their Cellulolytic Activities during the Composting of Municipal Solid Wastes. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 17, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandna, P.; Nain, L.; Singh, S.; Kuhad, R.C. Assessment of Bacterial Diversity during Composting of Agricultural Byproducts. BMC Microbiol. 2013, 13, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chung, J.; Jiang, Q.; Sun, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, Y.; Ren, N. Characteristics of Rumen Microorganisms Involved in Anaerobic Degradation of Cellulose at Various pH Values. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 40303–40310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, P.; Tramonti, A.; De Biase, D. Coping with Low pH: Molecular Strategies in Neutralophilic Bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 1091–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galetakis, M.; Alevizos, G.; Leventakis, K. Evaluation of Fine Limestone Quarry By-Products for the Production of Building Elements—An Experimental Approach. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 26, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, H.N.; Jørgensen, B.B. Big Bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001, 55, 105–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayilara, M.S.; Olanrewaju, O.S.; Babalola, O.O.; Odeyemi, O. Waste Management through Composting: Challenges and Potentials. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makan, A.; Assobhei, O.; Mountadar, M. Effect of Initial Moisture Content on the In-Vessel Composting under Air Pressure of Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste in Morocco. Iran. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2013, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamodharan, K.; Varma, V. S.; Veluchamy, C.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Rajendran, K. Emission of volatile organic compounds from composting: A review on assessment, treatment and perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 695, 133725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, S.; Ham, S.; Jeong, J.; Ku, H.; Kim, H.; Lee, C. Temperature matters: bacterial response to temperature change. J. Microbiol. 2023, 61, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setlow, P.; Christie, G. New thoughts on an old topic: secrets of bacterial spore resistance slowly being revealed. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2023, 87(2), e00080–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemet, F.; Perić, K.; Lončarić, Z. Microbiological Activities in the Composting Process—A Review. Columella J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2021, 8, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, N.N.; Yadav, B.; Roopesh, M.S.; Jo, C. Cold Plasma for Effective Fungal and Mycotoxin Control in Foods: Mechanisms, Inactivation Effects, and Applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.J.; Shah, M.K.; Powell, L.C.; Armstrong, I. Application of AFM from Microbial Cell to Biofilm. Scanning. 2010, 32, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikurendra, E.A.; Nurika, G.; Herdiani, N.; Lukiyono, Y.T. Evaluation of the Commercial Bio-Activator and a Traditional Bio-Activator on Compost Using Takakura Method. J. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 23, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, Ó.J.; Ospina, D.A.; Montoya, S. Compost Supplementation with Nutrients and Microorganisms in Composting Process. Waste Manag. 2017, 69, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harindintwali, J.D.; Zhou, J.; Muhoza, B.; Wang, F.; Herzberger, A.; Yu, X. Integrated Eco-Strategies towards Sustainable Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling in Agriculture. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutter, C. N. Microbial control by packaging: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2002, 42, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caceres, R.; Malińska, K.; Marfà, O. Nitrification within Composting: A Review. Waste Manag. 2018, 72, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beesley, L.; Dickinson, N. Carbon and Trace Element Fluxes in the Pore Water of an Urban Soil following Greenwaste Compost, Woody and Biochar Amendments, Inoculated with the Earthworm Lumbricus terrestris. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, K.C.; Bleichrodt, R. Go with the Flow: Mechanisms Driving Water Transport during Vegetative Growth and Fruiting. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2022, 41, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samri, S.E.D.; Aberkani, K.; Said, M.; Haboubi, K.; Ghazal, H. Effects of Inoculation with Mycorrhizae and the Benefits of Bacteria on Physicochemical and Microbiological Properties of Soil, Growth, Productivity and Quality of Table Grapes Grown under Mediterranean Climate Conditions. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2021, 61, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayilara, M.S.; Olanrewaju, O.S.; Babalola, O.O.; Odeyemi, O. Waste Management through Composting: Challenges and Potentials. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, M.; Nandal, M.; Khosla, B. Microbes as Vital Additives for Solid Waste Composting. Heliyon. 2020, 6, e03342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Aslam, Z.; Bellitürk, K.; Iqbal, N.; Naeem, S.; Idrees, M.; Kamal, A. Vermicomposting Methods from Different Wastes: An Environment Friendly, Economically Viable and Socially Acceptable Approach for Crop Nutrition: A Review. Int. J. Food Sci. Agric. 2021, 5, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Parakh, S.K.; Singh, S.P.; Parra-Saldívar, R.; Kim, S.H.; Varjani, S.; Tong, Y.W. A Critical Review on Microbes-Based Treatment Strategies for Mitigation of Toxic Pollutants. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 834, 155444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Liang, J.; Zeng, G.; Chen, M.; Mo, D.; Li, G.; Zhang, D. Seed Germination Test for Toxicity Evaluation of Compost: Its Roles, Problems and Prospects. Waste Manag. 2018, 71, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, M.M.; Bornman, J.F.; Ballaré, C.L.; Flint, S.D.; Kulandaivelu, G. Terrestrial Ecosystems, Increased Solar Ultraviolet Radiation, and Interactions with Other Climate Change Factors. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2007, 6, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeifer, G.P.; You, Y.H.; Besaratinia, A. Mutations Induced by Ultraviolet Light. Mutat. Res. Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2005, 571, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Yu, K.; Ahmed, I.; Gin, K.; Xi, B.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, B. Key Factors Driving the Fate of Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Controlling Strategies during Aerobic Composting of Animal Manure: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 791, 148372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenikov, V.I. Technology of Livestock and Poultry Waste Aerobic Fermentation. Russ. Agric. Sci. 2016, 42, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajalakshmi, S.; Abbasi, S.A. Solid Waste Management by Composting: State of the Art. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 38, 311–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| pH | Bacteria | References |

|---|---|---|

| pH = 4-6 | Acidophilic bacterial | Lorenzo et al., 2018 |

| pH = 6-8 | Neutrophil bacterial | Pinel et al., 2021 |

| pH = 9-11 | Alkaliphilic bacterial | Kanekar et al., 2022 |

| Temperature | Bacteria | References |

|---|---|---|

| 0-40°C | Mesophilic bacteria | Adekunle et al., 2011 |

| 40-50°C | Thermophilic bacteria | Hassen et al., 2001 |

| 50-55°C | Bacilli species | Ringel-Scaia et al., 2019 |

| 55-121°C | Thermus | Finore et al., 2023 |

| Moisture | Bacterial response | References |

|---|---|---|

| Lower than 30% | Limit bacteria activity | Liu et al., 2020 |

| 50-60% | Advantages of bacteria activity | Tiquia et al., 1996 |

| More than 65% | Bacilli species | Stone et al., 2016 |

| C: N Ratio | Bacterial response | References |

|---|---|---|

| 25:1 to 30:1 | Optimal | Azim et al., 2018 |

| Higher than 40:1 | Restricted | Brinton et al., 2000 |

| Less than 20:1 | Odor problems | Stark et al., 2008 |

| Electrical Conductivity | Plant type | References |

|---|---|---|

| 0.8 - 1.8 mS/cm | General Plants | Jacobs et al., 2005 |

| 1.6 - 1.8 mS/cm | Vegetables | Amalfitano et al., 2017 |

| 2 - 2.2 mS/cm | Fruit trees | Karam et al., 2005 |

| Below 0.2 mS/cm | Deficient | Maestre et al., 2019 |

| Material size | Heat retention | Moisture | C/N ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5–15 mm | 7 days | 23.37% | 16.91 |

| 15–30 mm | 8 days | 22.86% | 15.05 |

| 30–45 mm | 4 days | 21.84% | 18.13 |

| 45–75 mm | 3 days | 20.80% | 20.99 |

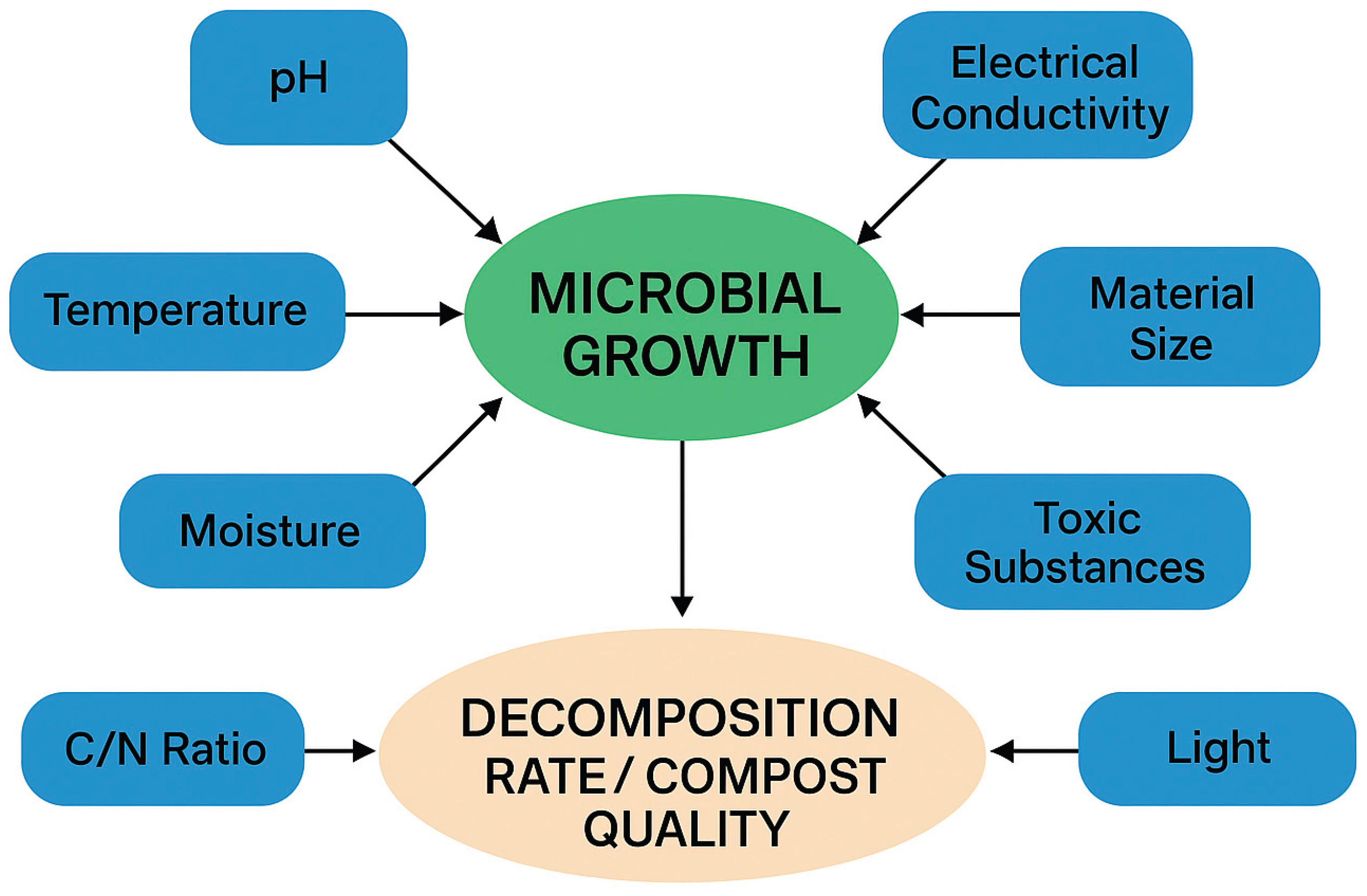

| Factors | Optimal Range | Impact on bacterial | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 6–8 (neutrophilic bacteria); acidophilic 4–6; alkaliphilic 9–11 | Effects on membrane permeability, metabolism, enzyme activity | Adjust with lime or alkaline/acidic agents as needed. |

| Temperature | Mesophilic: 20–45 °C; Thermophilic: 50–70 °C; Thermus: >55 °C | Affects metabolic rate, enzymes, microbial growth | Temperature management to optimize decomposition and kill pathogens |

| Humidity | 50–60% initially, down to ~30% final i | Maintain metabolic activity, decomposition rate | Manual test: material is moist but not leaking |

| C/N ratio | 25:1–35:1 optimal; 20:1–40:1 acceptable | Balance energy and protein, prevent odor, limit nitrogen loss | Use N-rich “greens” and C-rich “browns” |

| Electrical Conductivity (EC) | 0.8–1.8 mS/cm for plants; do not exceed 2.5 mS/cm | Too high/low EC affects microbial metabolism and plant growth. | Monitor EC during incubation; adjust with organic material |

| Material size | 15–30 mm optimal; 3–50 mm acceptable | Influence of surface area, aeration, decomposition rate | Cut, crush, screen to achieve optimal size |

| Poison | Limit heavy metals, phenols, plastics, surfactants | Enzyme inhibition, gene mutation, microbial death | Eliminate non-biodegradable waste, plastic |

| Light/UV | Avoid direct exposure to sunlight and UV rays | UV 253.7 nm, X-ray, α, β kill microorganisms | Store in shade or cool place; avoid UV-A and blue light |

| Oxy (aeration) |

AFP and FAS adequate; maintain 5–10 m³/h/ton if using air blowing | Provide O₂ for aerobic microorganisms, reduce odor | Rotate, turn or use ASP to adjust air |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).