Submitted:

23 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

‘I think it may fairly be assumed, in the light of what we now know, that no other measure will, statistically speaking, furnish so delicate and precise a measure of the general constitutional fitness of individuals as will their duration of life.’Raymond Pearl, 1923

1. Introduction

2. Results

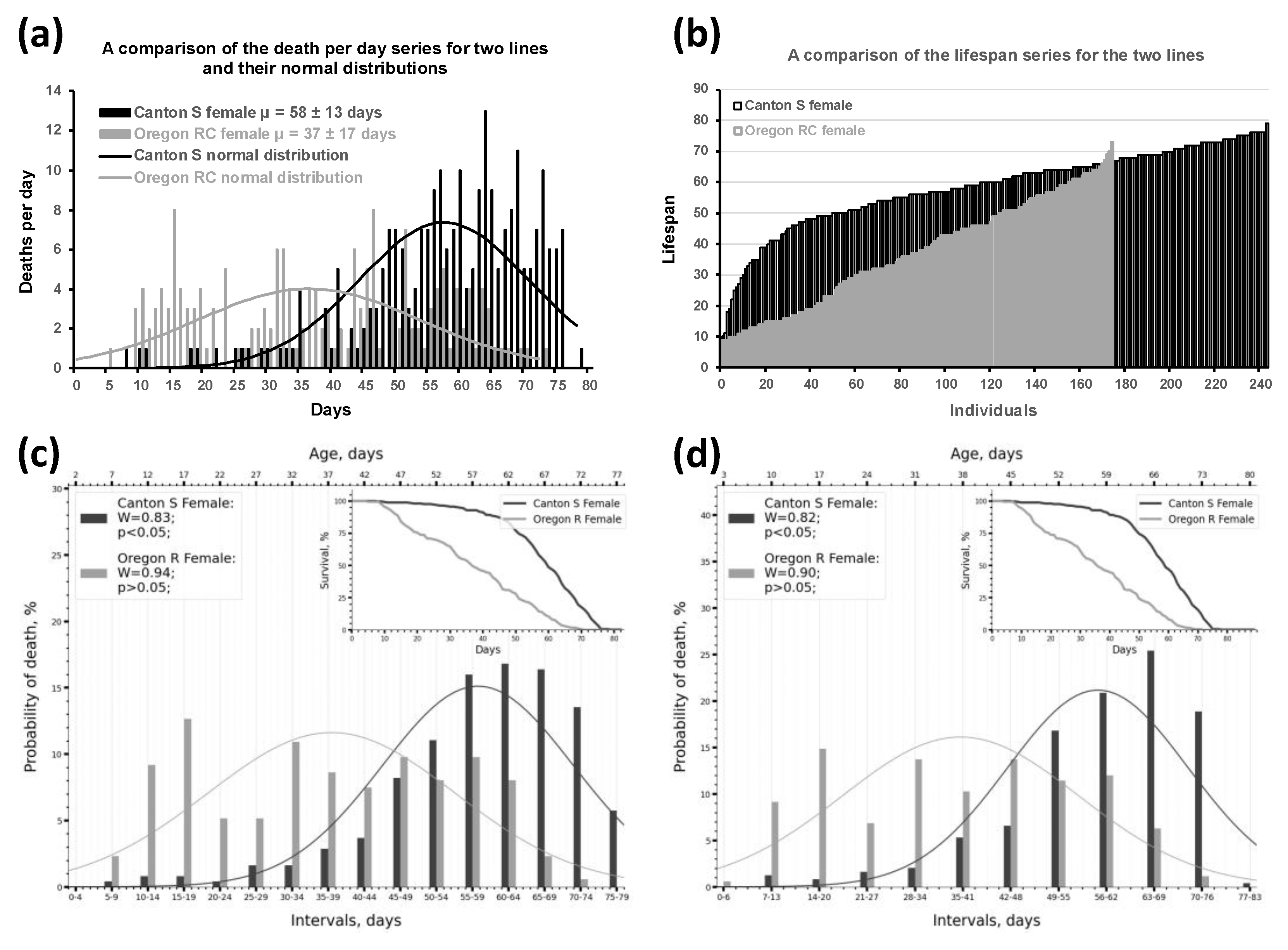

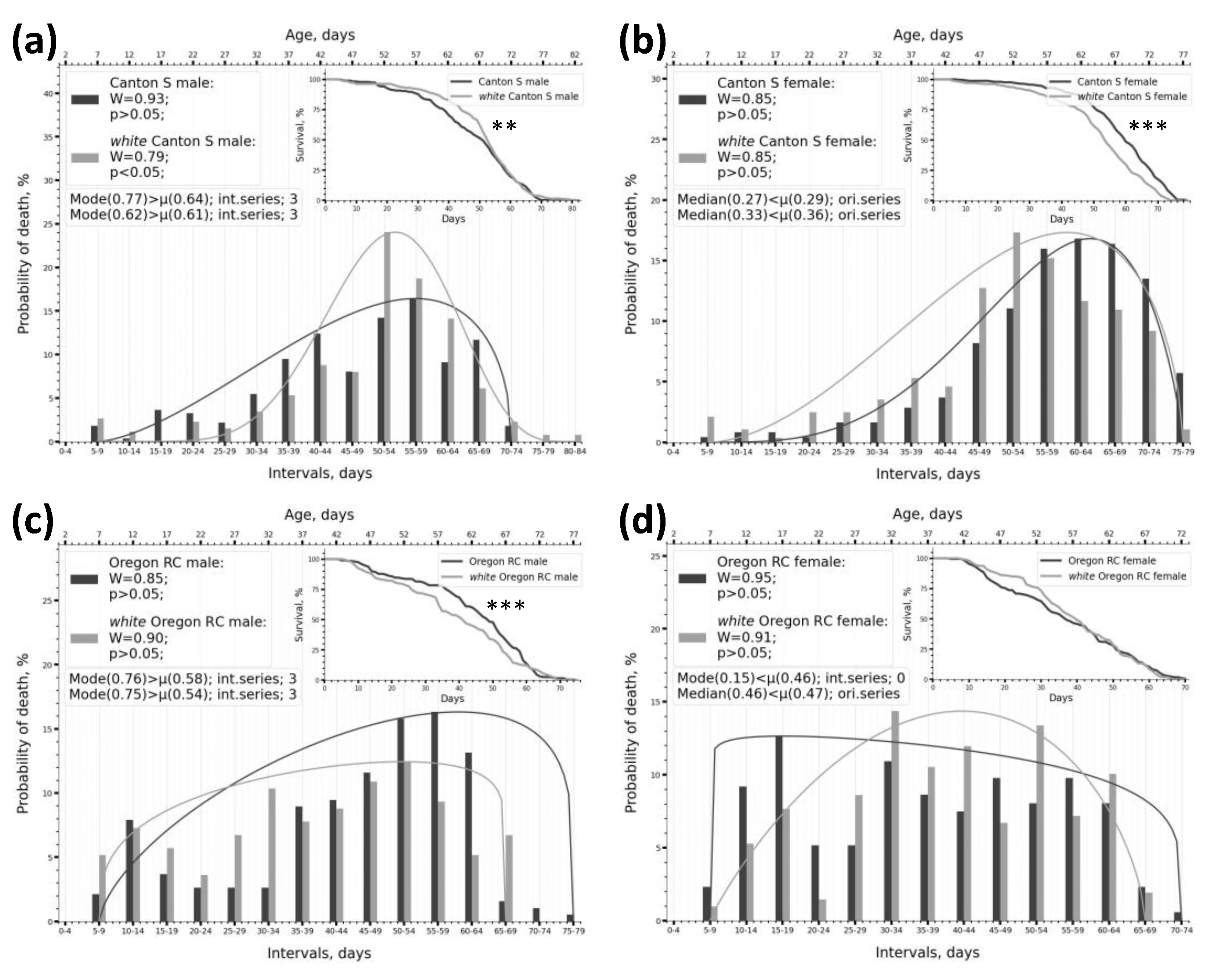

2.1. Dividing Survival Data into Intervals Enables an Effective Assessment of Phenotype Frequencies by Lifespan Within the Sample

2.2. Using Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk Normality Tests to Describe the Parameters of the Lifespan Distribution

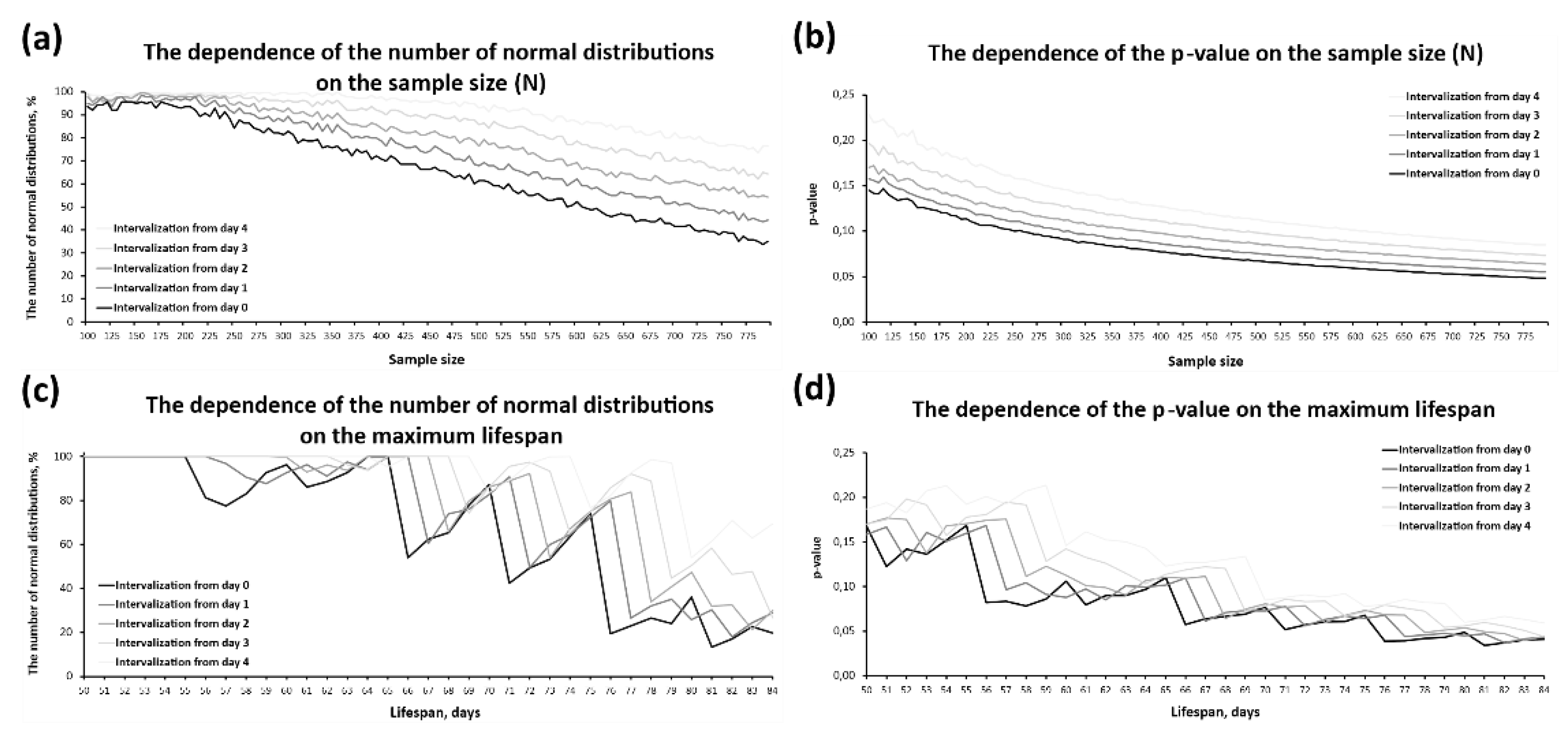

2.3. Peculiarities of SW Test Functioning Under Different Intervalisation Conditions and on Samples of Various Types

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | ||||||||||

| Genotype | Sex | µ, days |

Internalization* from | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| day 0 | day 1 | day 2 | day 3 | day 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| W | p-value** | Number of intervals | W | p-value | Number of intervals | W | p-value | Number of intervals | W | p-value | Number of intervals | W | p- value |

Number of intervals | |||||||||||||

| w1118 (2024) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Canton S | M | 34.8 | 0.89 | 0.091 | 13 | 0.91 | 0.153 | 14 | 0.87 | 0.038 | 14 | 0.91 | 0.146 | 14 | 0.92 | 0.271 | 13 | ||||||||||

| F | 33.1 | 0.94 | 0.478 | 13 | 0.93 | 0.262 | 14 | 0.94 | 0.457 | 14 | 0.92 | 0.242 | 14 | 0.93 | 0.282 | 14 | |||||||||||

| w1118 Canton S |

M | 31.6 | 0.80 | 0.005 | 14 | 0.82 | 0.008 | 14 | 0.81 | 0.006 | 14 | 0.78 | 0.004 | 13 | 0.81 | 0.008 | 13 | ||||||||||

| F | 25.2 | 0.84 | 0.019 | 13 | 0.83 | 0.017 | 13 | 0.81 | 0.009 | 13 | 0.80 | 0.006 | 13 | 0.79 | 0.005 | 13 | |||||||||||

| Oregon RC | M | 35.2 | 0.78 | 0.005 | 12 | 0.81 | 0.014 | 12 | 0.81 | 0.009 | 13 | 0.80 | 0.007 | 13 | 0.76 | 0.003 | 12 | ||||||||||

| F | 27.9 | 0.92 | 0.324 | 11 | 0.93 | 0.400 | 11 | 0.95 | 0.654 | 11 | 0.92 | 0.294 | 12 | 0.92 | 0.289 | 12 | |||||||||||

|

w1118 Oregon RC |

M | 33.7 | 0.85 | 0.034 | 12 | 0.85 | 0.034 | 12 | 0.83 | 0.023 | 12 | 0.81 | 0.017 | 11 | 0.82 | 0.020 | 11 | ||||||||||

| F | 25.1 | 0.88 | 0.106 | 11 | 0.90 | 0.239 | 10 | 0.88 | 0.135 | 10 | 0.86 | 0.086 | 10 | 0.89 | 0.176 | 10 | |||||||||||

| w67c23 (2024) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Canton S | M | 33.3 | 0.83 | 0.010 | 15 | 0.77 | 0.002 | 15 | 0.80 | 0.004 | 15 | 0.87 | 0.029 | 15 | 0.87 | 0.039 | 14 | ||||||||||

| F | 31.2 | 0.90 | 0.123 | 14 | 0.77 | 0.003 | 13 | 0.74 | 0.001 | 13 | 0.93 | 0.305 | 13 | 0.90 | 0.157 | 13 | |||||||||||

| w67c23 Canton S |

M | 39.7 | 0.97 | 0.756 | 17 | 0.95 | 0.456 | 17 | 0.93 | 0.254 | 16 | 0.92 | 0.158 | 16 | 0.95 | 0.521 | 16 | ||||||||||

| F | 37.5 | 0.94 | 0.408 | 16 | 0.96 | 0.699 | 16 | 0.98 | 0.965 | 16 | 0.95 | 0.433 | 16 | 0.96 | 0.713 | 15 | |||||||||||

| Oregon RC | M | 36.4 | 0.94 | 0.417 | 15 | 0.93 | 0.314 | 14 | 0.93 | 0.298 | 14 | 0.94 | 0.381 | 14 | 0.96 | 0.650 | 14 | ||||||||||

| F | 26.7 | 0.92 | 0.232 | 13 | 0.91 | 0.222 | 12 | 0.93 | 0.393 | 12 | 0.90 | 0.161 | 12 | 0.92 | 0.267 | 12 | |||||||||||

|

w67c23 Oregon RC |

M | 45.6 | 0.84 | 0.008 | 17 | 0.87 | 0.019 | 17 | 0.87 | 0.029 | 16 | 0.87 | 0.028 | 16 | 0.87 | 0.030 | 16 | ||||||||||

| F | 41.7 | 0.87 | 0.039 | 15 | 0.87 | 0.035 | 15 | 0.88 | 0.055 | 15 | 0.86 | 0.027 | 14 | 0.89 | 0.088 | 14 | |||||||||||

| w67c23 (2012) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Canton S | M | 47.9 | 0.92 | 0.251 | 14 | 0.91 | 0.117 | 15 | 0.92 | 0.200 | 15 | 0.93 | 0.253 | 15 | 0.91 | 0.117 | 15 | ||||||||||

| F | 58.3 | 0.83 | 0.010 | 15 | 0.82 | 0.007 | 15 | 0.80 | 0.004 | 15 | 0.83 | 0.009 | 15 | 0.81 | 0.004 | 16 | |||||||||||

|

w67c23 Canton S |

M | 50.7 | 0.80 | 0.003 | 16 | 0.81 | 0.003 | 17 | 0.82 | 0.004 | 17 | 0.81 | 0.004 | 16 | 0.82 | 0.005 | 16 | ||||||||||

| F | 52.2 | 0.89 | 0.063 | 15 | 0.89 | 0.067 | 15 | 0.84 | 0.010 | 16 | 0.84 | 0.008 | 16 | 0.87 | 0.032 | 15 | |||||||||||

| Oregon RC | M | 44.6 | 0.87 | 0.036 | 15 | 0.87 | 0.031 | 15 | 0.89 | 0.063 | 15 | 0.89 | 0.072 | 15 | 0.89 | 0.066 | 15 | ||||||||||

| F | 37.2 | 0.94 | 0.457 | 14 | 0.94 | 0.438 | 14 | 0.97 | 0.906 | 14 | 0.95 | 0.637 | 14 | 0.91 | 0.143 | 14 | |||||||||||

|

w67c23 Oregon RC |

M | 39.4 | 0.98 | 0.946 | 13 | 0.91 | 0.204 | 13 | 0.93 | 0.274 | 14 | 0.92 | 0.220 | 14 | 0.91 | 0.155 | 14 | ||||||||||

| F | 39.4 | 0.95 | 0.587 | 13 | 0.92 | 0.290 | 13 | 0.95 | 0.608 | 13 | 0.96 | 0.772 | 12 | 0.92 | 0.287 | 13 | |||||||||||

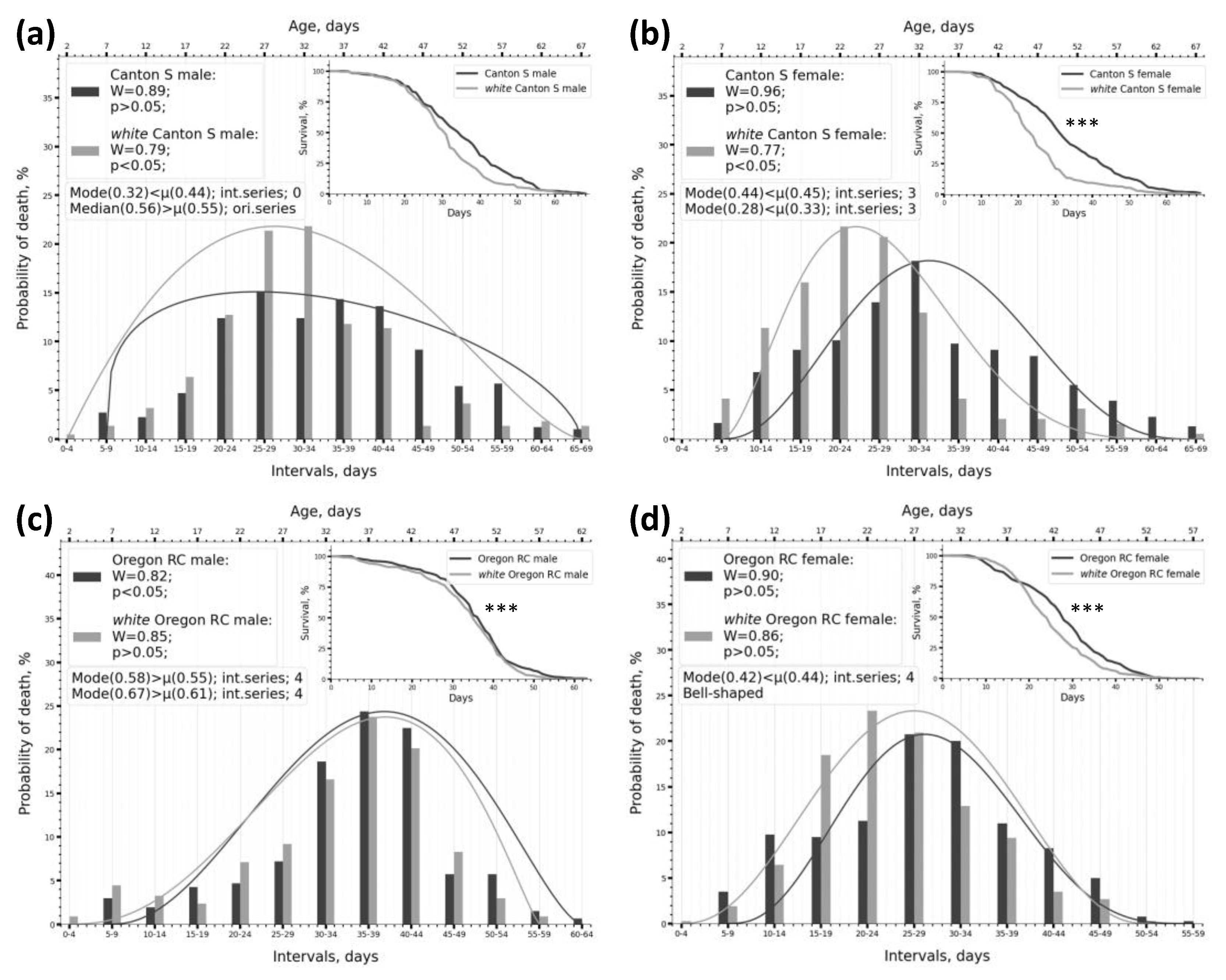

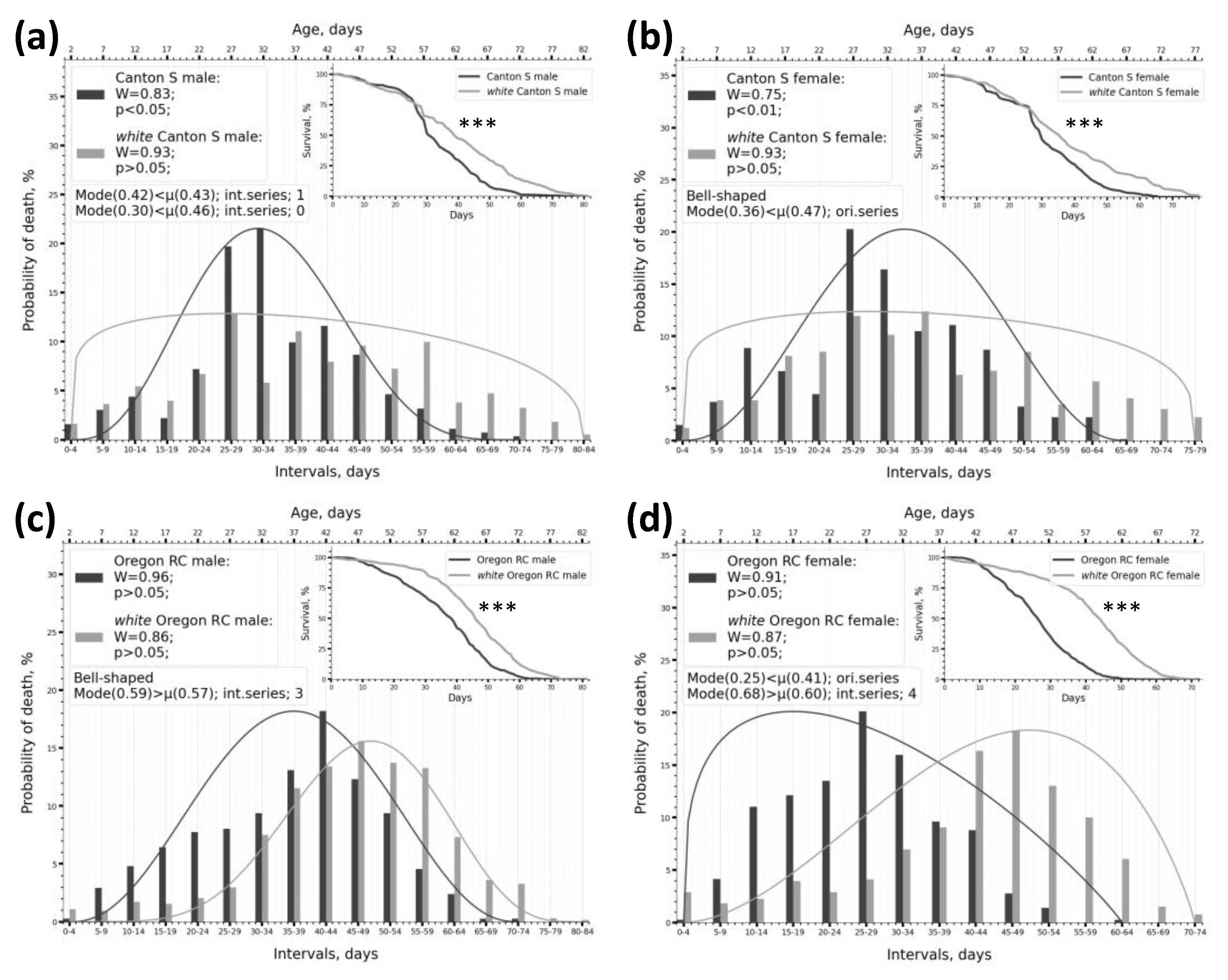

2.4. Peculiarities of SW Test Functioning Under Different Intervalisation Conditions and on Samples of Various Types

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Drosophila Lines and Survival Data for Analysis

3.2. Partitioning Survival Data into Intervals (Obtaining Frequency/Probability Series of Lifespan)

3.3. Formal Description of Frequency/Probability Series of Phenotypes by Lifespan and Mortality Series Using the Normal Distribution Function

3.4. Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test Calculation for Single Samples

3.5. Calculation of the Two Sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test

3.6. Shapiro-Wilk Test Calculation for Single Samples

3.7. Calculating the β-Distribution of Lifespan

4. Discussion

4.1. The Situation with the Study of Lifespan Distributions in General

4.2. The Destabilisation of Ontogenesis and Changes in Lifespan Distribution Under Genetic Interventions

4.3. Selection of Tests for Analysing Lifespan Data to Determine Normality

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Falconer, D.S.; Mackay, T.F.C. Introduction to Quantitative Genetics.; Longman: London, UK, 1996, 1996;

- Bylino, O.V.; Ogienko, A.A.; Batin, M.A.; Georgiev, P.G.; Omelina, E.S. Genetic, Environmental, and Stochastic Components of Lifespan Variability: The Drosophila Paradigm. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 4482. [CrossRef]

- Olshansky, S.J.; Willcox, B.J.; Demetrius, L.; Beltrán-Sánchez, H. Implausibility of Radical Life Extension in Humans in the Twenty-First Century. Nat Aging 2024, 4, 1635–1642. [CrossRef]

- Flatt, T.; Partridge, L. Horizons in the Evolution of Aging. BMC Biology 2018, 16, 93. [CrossRef]

- Fleming, T.R.; O’Fallon, J.R.; O’Brien, P.C.; Harrington, D.P. Modified Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test Procedures with Application to Arbitrarily Right-Censored Data. Biometrics 1980, 36, 607–625. [CrossRef]

- Mantel, N. Evaluation of Survival Data and Two New Rank Order Statistics Arising in Its Consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep 1966, 50, 163–170.

- Wang, C.; Li, Q.; Redden, D.T.; Weindruch, R.; Allison, D.B. Statistical Methods for Testing Effects on “Maximum Lifespan.” Mech Ageing Dev 2004, 125, 629–632. [CrossRef]

- Moskalev, A.; Shaposhnikov, M. Pharmacological Inhibition of NF-κB Prolongs Lifespan of Drosophila Melanogaster. Aging (Albany NY) 2011, 3, 391–394. [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. The Chi-Square Test of Independence. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2013, 23, 143–149. [CrossRef]

- Sturges, H.A. The Choice of a Class Interval. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1926, 21, 65–66.

- Morgan, T.H. Sex Limited Inheritance in Drosophila. Science 1910, 32, 120–122. [CrossRef]

- Green, M.M. 2010: A Century of Drosophila Genetics through the Prism of the White Gene. Genetics 2010, 184, 3–7. [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.; Porter, M.; Narwold, K.; Bhat, K.; Dauwalder, B.; Roman, G. Mutants of the White ABCG Transporter in Drosophila Melanogaster Have Deficient Olfactory Learning and Cholesterol Homeostasis. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, A.; Nishimura, T.; Takano, T.; Naito, S.; Yoo, S.K. White Regulates Proliferative Homeostasis of Intestinal Stem Cells during Ageing in Drosophila. Nat Metab 2021, 3, 546–557. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Qiu, S. Frequency-Specific Modification of Locomotor Components by the White Gene in Drosophila Melanogaster Adult Flies. Genes Brain Behav 2021, 20, e12703. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Grimau, V.; Pérez-Gálvez, A.; Busturia, A.; Fontecha, J. Lipidomic Profiling of Drosophila Strains Canton-S and White1118 Reveals Intraspecific Lipid Variations in Basal Metabolic Rate. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 2024, 201, 102618. [CrossRef]

- Rickle, A.; Sudhakar, K.; Booms, A.; Stirtz, E.; Lempradl, A. More than Meets the Eye: Mutation of the White Gene in Drosophila Has Broad Phenotypic and Transcriptomic Effects. Genetics 2025, iyaf097. [CrossRef]

- Linford, N.J.; Bilgir, C.; Ro, J.; Pletcher, S.D. Measurement of Lifespan in Drosophila Melanogaster. J Vis Exp 2013, 50068. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Jasper, H. Studying Aging in Drosophila. Methods 2014, 68, 129–133. [CrossRef]

- Piper, M.D.W.; Partridge, L. Protocols to Study Aging in Drosophila. Methods Mol Biol 2016, 1478, 291–302. [CrossRef]

- Piper, M.D.W.; Partridge, L. Drosophila as a Model for Ageing. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2018, 1864, 2707–2717. [CrossRef]

- Ogienko, A.A.; Omelina, E.S.; Bylino, O.V.; Batin, M.A.; Georgiev, P.G.; Pindyurin, A.V. Drosophila as a Model Organism to Study Basic Mechanisms of Longevity. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 11244. [CrossRef]

- Louka, X.P.; Gumeni, S.; Trougakos, I.P. Studying Cellular Senescence Using the Model Organism Drosophila Melanogaster. Methods Mol Biol 2025, 2906, 281–299. [CrossRef]

- Na, H.-J.; Park, J.-S. Measuring Anti-Aging Effects in Drosophila. Bio Protoc 2025, 15, e5305. [CrossRef]

- Kolmogoroff, A. “Sulla Determinazione Empirica Di Una Legge Di Distribuzione.” ”Giornale dell’ Istituto Italiano degli Attuari. 1933, 4, 83–91.

- Feller, W. On the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Limit Theorems for Empirical Distributions. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 1948, 19, 177–189. [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, N. On the Estimation of the Discrepancy between Critical Curves of Distribution of Two Independent Samples. Bulletin Mathématique de l’Université de Moscou. 1939, 2, 1–16.

- Miller, L.H. Table of Percentage Points of Kolmogorov Statistics. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1956.

- Massey, F.J. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test for Goodness of Fit. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1951, 46, 68–78. [CrossRef]

- Facchinetti, S. A Procedure to Find Exact Critical Values of Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test. Statistica Applicata 2009, 337–359.

- Smirnov, N. Table for Estimating the Goodness of Fit of Empirical Distributions. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 1948, 19, 279–281.

- Hodges, J.L. The Significance Probability of the Smirnov Two-Sample Test. Ark. Mat. 1958, 3, 469–486. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An Analysis of Variance Test for Normality (Complete Samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [CrossRef]

- Royston, P. A Toolkit for Testing for Non-Normality in Complete and Censored Samples. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series D (The Statistician) 1993, 42, 37–43. [CrossRef]

- Warne, R.T. Statistics for the Social Sciences: A General Linear Model Approach; 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2020; ISBN 978-1-108-89431-9.

- Royston, P. Remark AS R94: A Remark on Algorithm AS 181: The W-Test for Normality. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series C (Applied Statistics) 1995, 44, 547–551. [CrossRef]

- Cramer, Н. Mathematical Methods of Statistics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, 1957; Vol. Vol. 7.;

- Robertson, H.T.; Allison, D.B. A Novel Generalized Normal Distribution for Human Longevity and Other Negatively Skewed Data. PLoS One 2012, 7, e37025. [CrossRef]

- Skulachev, V.P.; Shilovsky, G.A.; Putyatina, T.S.; Popov, N.A.; Markov, A.V.; Skulachev, M.V.; Sadovnichii, V.A. Perspectives of Homo Sapiens Lifespan Extension: Focus on External or Internal Resources? Aging 2020, 12, 5566–5584. [CrossRef]

- Stroustrup, N.; Anthony, W.E.; Nash, Z.M.; Gowda, V.; Gomez, A.; López-Moyado, I.F.; Apfeld, J.; Fontana, W. The Temporal Scaling of Caenorhabditis Elegans Ageing. Nature 2016, 530, 103–107. [CrossRef]

- Ezcurra, M.; Benedetto, A.; Sornda, T.; Gilliat, A.F.; Au, C.; Zhang, Q.; van Schelt, S.; Petrache, A.L.; Wang, H.; de la Guardia, Y.; et al. C. Elegans Eats Its Own Intestine to Make Yolk Leading to Multiple Senescent Pathologies. Curr Biol 2018, 28, 2544-2556.e5. [CrossRef]

- Kern, C.C.; Srivastava, S.; Ezcurra, M.; Hsiung, K.C.; Hui, N.; Townsend, S.; Maczik, D.; Zhang, B.; Tse, V.; Konstantellos, V.; et al. C. Elegans Ageing Is Accelerated by a Self-Destructive Reproductive Programme. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 4381. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Senturk, D.; Wang, J.-L.; Muller, H.-G.; Carey, J.R.; Caswell, H.; Caswell-Chen, E.P. A Demographic Analysis of the Fitness Cost of Extended Longevity in Caenorhabditis Elegans. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 2007, 62, 126–135. [CrossRef]

- Pearl, R.; Parker, S. Experimental Studies on the Duration of Life. VI. A Comparison of the Laws of Mortality in Drosophila and in Man. The American Naturalist 1922, 56, 398–405. [CrossRef]

- Pearl, R. Duration of Life as an Index of Constitutional Fitness*. Poultry Science 1923, 3, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Pfenninger, M. The Effect of Offspring Number on the Adaptation Speed of a Polygenic Trait 2017.

- Krohs, U. Darwin’s Empirical Claim and the Janiform Character of Fitness Proxies. Biol Philos 2022, 37, 15. [CrossRef]

- Viblanc, V.A.; Saraux, C.; Tamian, A.; Criscuolo, F.; Coltman, D.W.; Raveh, S.; Murie, J.O.; Dobson, F.S. Measuring Fitness and Inferring Natural Selection from Long-Term Field Studies: Different Measures Lead to Nuanced Conclusions. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 2022, 76, 79. [CrossRef]

- Orr, H.A. Fitness and Its Role in Evolutionary Genetics. Nat Rev Genet 2009, 10, 531–539. [CrossRef]

- Flatt, T. Life-History Evolution and the Genetics of Fitness Components in Drosophila Melanogaster. Genetics 2020, 214, 3–48. [CrossRef]

- Clancy, D.; Chtarbanova, S.; Broughton, S. Editorial: Model Organisms in Aging Research: Drosophila Melanogaster. Front Aging 2023, 3, 1118299. [CrossRef]

- Izmaĭlov, D.M.; Obukhova, L.K. Analysis of the life span distribution mode in 128 successive generations of D. melanogaster. Adv Gerontol 2004, 15, 30–35.

- Azzalini, A. The Skew-Normal Distribution and Related Multivariate Families*. Scand J Stat 2005, 32, 159–188. [CrossRef]

- Arnastauskaitė, J.; Ruzgas, T.; Bražėnas, M. An Exhaustive Power Comparison of Normality Tests. Mathematics 2021, 9, 788. [CrossRef]

- Simard, R.; L’Ecuyer, P. Computing the Two-Sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov Distribution. Journal of Statistical Software 2011, 39, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Mara, U.T. Power Comparisons of Shapiro-Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Lilliefors and Anderson-Darling Tests. 2011, 2, 21–33.

- Marsaglia, G.; Tsang, W.W.; Wang, J. Evaluating Kolmogorov’s Distribution. Journal of Statistical Software 2003, 8, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Lilliefors, H.W. On the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test for Normality with Mean and Variance Unknown. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1967, 62, 399–402. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.L. Systems of Frequency Curves Generated by Methods of Translation. Biometrika 1949, 36, 149. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, T.S.; Gendron, C.M.; Lyu, Y.; Munneke, A.S.; DeMarco, M.N.; Hoisington, Z.W.; Pletcher, S.D. Sensory Perception of Dead Conspecifics Induces Aversive Cues and Modulates Lifespan through Serotonin in Drosophila. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 2365. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Zhang, M.; Wang, S.-H.; Chieh, C.-W.; Shen, P.-Y.; Chen, Y.-L.; Chang, Y.-C.; Kuo, T.-H. The Deleterious Effects of Old Social Partners on Drosophila Lifespan and Stress Resistance. npj Aging 2022, 8, 1. [CrossRef]

- Bushey, D.; Hughes, K.A.; Tononi, G.; Cirelli, C. Sleep, Aging, and Lifespan in Drosophila. BMC Neuroscience 2010, 11, 56. [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

| Genotype | Sex | µ, days |

σ, days |

SW test w/o intervals |

SW test intervals |

KS test w/o intervals |

KS test intervals |

Two sample KS test (WT vs. mut.) |

Number of intervals | Sample size | |||||

| W | p-value* | W | p-value* | Dn | p-value* | Dn | p-value* | n | |||||||

| Canton S | M | 34.8 | ± 12.7 |

0.99 | 0.036 not norm. |

0.89 | 0.091 norm. |

0.05 | 0.285 norm. |

0.20 | 0.646 norm. |

‒ | 13 | 404 | |

| F | 33.1 | ± 13.5 |

0.98 | 0.001 not norm |

0.94 | 0.478 norm. |

0.07 | 0.091 norm. |

0.15 | 0.917 norm. |

13 | 308 | |||

| w1118 Canton S |

M | 31.6 | ± 11.2 |

0.97 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.80 | 0.005 not norm. |

0.10 | 0.018 not norm. |

0.26 | 0.307 not norm** |

p<0.001*** | 14 | 220 | |

| F | 25.2 | ± 10.7 |

0.92 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.84 | 0.019 not norm. |

0.12 | 0.011 not norm. |

0.30 | 0.197 not norm** |

p<0.001 | 13 | 194 | ||

| Oregon RC | M | 35.2 | ± 10.4 |

0.96 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.78 | 0.005 not norm. |

0.10 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.31 | 0.212 not norm** |

‒ | 12 | 472 | |

| F | 27.9 | ± 10.6 |

0.98 | 0.0001 not norm. |

0.92 | 0.324 norm. |

0.06 | 0.115 norm. |

0.19 | 0.834 norm. |

11 | 400 | |||

| w1118 Oregon RC |

M | 33.7 | ± 10.9 |

0.95 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.85 | 0.034 not norm. |

0.11 | 0.001 not norm. |

0.20 | 0.702 norm. |

p>0.05 | 12 | 337 | |

| F | 25.1 | ± 8.7 |

0.98 | 0.0004 not norm. |

0.88 |

0.106 norm. |

0.08 |

0.019 not norm. |

0.21 | 0.725 norm. |

p<0.001 | 11 | 373 | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| Genotype | Sex | µ, days |

σ, days |

SW test w/o intervals |

SW test intervals |

KS test w/o intervals |

KS test intervals |

Two sample KS test (WT vs. mut.) |

Number of intervals |

Sample size | ||||

| W | p-value* | W | p-value* | Dn | p-value* | Dn | p-value* | n | ||||||

| Canton S | M | 33.3 | ± 12.7 |

0.98 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.83 | 0.010 not norm. |

0.09 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.22 | 0.443 norm. |

‒ | 15 | 817 |

| F | 31.2 | ± 13.3 |

0.99 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.90 |

0.123 norm. |

0.11 |

<0.0001 not norm. |

0.18 | 0.740 norm. |

14 | 676 | ||

| w67c23 Canton S |

M | 39.7 | ± 18.2 |

0.99 | 0.0001 not norm. |

0.97 |

0.756 norm. |

0.06 |

0.020 not norm. |

0.12 | 0.960 not norm** |

p<0.0001 | 17 | 552 |

| F | 37.5 | ± 18.0 |

0.98 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.94 |

0.408 norm. |

0.07 |

0.012 not norm. |

0.18 | 0.654 norm. |

p<0.0001 | 16 | 493 | |

| Oregon RC | M | 36.4 | ± 13.7 |

0.98 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.94 |

0.417 norm. |

0.08 |

0.013 not norm. |

0.11 | 0.994 norm. |

‒ | 15 | 374 |

| F | 26.7 | ± 10.5 |

0.99 | 0.0075 not norm. |

0.92 | 0.232 norm. |

0.05 | 0.254 norm. |

0.17 | 0.839 norm. |

13 | 363 | ||

| w67c23 Oregon RC |

M | 45.6 | ± 14.2 |

0.97 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.84 | 0.008 not norm. |

0.06 | 0.019 not norm. |

0.25 | 0.222 not norm** |

p<0.0001 | 17 | 641 |

| F | 41.7 | ± 14.9 |

0.94 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.87 | 0.039 not norm. |

0.12 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.22 | 0.479 not norm** |

p<0.0001 | 15 | 660 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| Genotype | Sex | µ, days |

σ, days |

SW test w/o intervals |

SW test intervals |

KS test w/o intervals |

KS test intervals |

Two sample KS test (WT vs. mut.) |

Number of intervals |

Sample size | ||||

| W | p-value* | W | p-value* | Dn | p-value* | Dn | p-value* | n | ||||||

| Canton S | M | 47.9 | ± 14.9 |

0.95 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.92 |

0.251 norm. |

0.11 |

0.003 not norm. |

0.19 | 0.720 norm. |

‒ |

14 | 274 |

| F | 58.3 | ± 13.2 |

0.92 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.83 | 0.010 not norm. |

0.09 | 0.046 not norm. |

0.22 | 0.473 norm. |

15 | 244 | ||

| w67с23 Canton S |

M | 50.7 | ± 13.8 |

0.92 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.80 | 0.003 not norm. |

0.15 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.22 | 0.406 not norm** |

p=0.005 *** |

16 | 262 |

| F | 52.2 | ± 14.7 |

0.93 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.89 |

0.063 norm. |

0.12 |

0.001 not norm. |

0.20 | 0.594 norm. |

p<0.0001 | 15 | 283 | |

| Oregon RC | M | 44.6 | ± 16.5 |

0.92 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.87 | 0.036 not norm. |

0.13 | 0.003 not norm. |

0.24 | 0.332 not norm** |

‒ |

15 | 190 |

| F | 37.2 | ± 17.4 |

0.96 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.94 | 0.407 norm. |

0.09 | 0.098 norm. |

0.18 | 0.773 norm. |

14 | 175 | ||

| w67c23 Oregon RC |

M | 39.4 | ± 17.4 |

0.96 | <0.0001 not norm. |

0.98 |

0.946 norm. |

0.10 |

0.043 not norm. |

0.11 | 0.996 norm. |

p<0.001 | 13 | 193 |

| F | 39.4 | ± 15.3 |

0.97 | 0.0002 not norm. |

0.95 | 0.587 norm. |

0.08 | 0.127 norm. |

0.14 | 0.951 norm. |

p=0.040 | 14 | 209 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| Genotype | Sex | µ, days |

Intervalisation according to Sturges's rule | Intervalisation using a five-day interval | ||||||

| W | p-value* | Number of intervals | Interval length | W | p-value | Number of intervals | Interval length | |||

| w1118 (2024) | ||||||||||

| Canton S | M | 34.83 | 0.89 | 0.221 | 9 | 7.17 | 0.89 | 0.091 | 13 | 5 |

| F | 33.09 | 0.96 | 0.885 | 9 | 7.44 | 0.94 | 0.478 | 13 | 5 | |

| w1118 Canton S |

M | 31.59 | 0.80 | 0.025 | 9 | 7.29 | 0.80 | 0.005 | 14 | 5 |

| F | 25.20 | 0.78 | 0.015 | 9 | 6.98 | 0.84 | 0.019 | 13 | 5 | |

| Oregon RC | M | 35.21 | 0.83 | 0.033 | 10 | 6.07 | 0.78 | 0.005 | 12 | 5 |

| F | 27.86 | 0.91 | 0.270 | 10 | 5.45 | 0.92 | 0.324 | 11 | 5 | |

| w1118 Oregon RC |

M | 33.69 | 0.85 | 0.065 | 10 | 5.85 | 0.85 | 0.034 | 12 | 5 |

| F | 25.11 | 0.86 | 0.086 | 10 | 5.03 | 0.88 | 0.106 | 11 | 5 | |

| w67c23 (2024) | ||||||||||

| Canton S | M | 33.28 | 0.84 | 0.035 | 11 | 7.12 | 0.83 | 0.010 | 15 | 5 |

| F | 31.21 | 0.75 | 0.006 | 10 | 6.44 | 0.90 | 0.123 | 14 | 5 | |

| w67c23 Canton S |

M | 39.70 | 0.94 | 0.521 | 11 | 7.91 | 0.97 | 0.756 | 17 | 5 |

| F | 37.53 | 0.94 | 0.574 | 10 | 7.74 | 0.94 | 0.408 | 16 | 5 | |

| Oregon RC | M | 36.36 | 0.97 | 0.901 | 10 | 7.02 | 0.94 | 0.417 | 15 | 5 |

| F | 26.68 | 0.91 | 0.310 | 10 | 5.89 | 0.92 | 0.232 | 13 | 5 | |

| w67c23 Oregon RC |

M | 45.64 | 0.86 | 0.085 | 10 | 8.38 | 0.84 | 0.008 | 17 | 5 |

| F | 41.70 | 0.87 | 0.108 | 10 | 7.47 | 0.87 | 0.039 | 15 | 5 | |

| w67c23 (2012) | ||||||||||

| Canton S | M | 47.85 | 0.94 | 0.579 | 10 | 7.64 | 0.92 | 0.251 | 14 | 5 |

| F | 58.25 | 0.85 | 0.087 | 9 | 7.95 | 0.83 | 0.010 | 15 | 5 | |

| w67c23 Canton S |

M | 50.68 | 0.80 | 0.016 | 10 | 8.52 | 0.80 | 0.003 | 16 | 5 |

| F | 52.22 | 0.86 | 0.095 | 9 | 8.06 | 0.89 | 0.063 | 15 | 5 | |

| Oregon RC | M | 44.57 | 0.86 | 0.096 | 9 | 8.17 | 0.87 | 0.036 | 15 | 5 |

| F | 36.96 | 0.96 | 0.817 | 9 | 7.70 | 0.94 | 0.457 | 14 | 5 | |

|

w67c23 Oregon RC |

M | 39.37 | 0.90 | 0.280 | 9 | 7.35 | 0.98 | 0.946 | 13 | 5 |

| F | 39.53 | 0.91 | 0.366 | 9 | 6.99 | 0.95 | 0.587 | 13 | 5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).