Submitted:

23 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Research Sample

2.3. Physiotherapy Examination

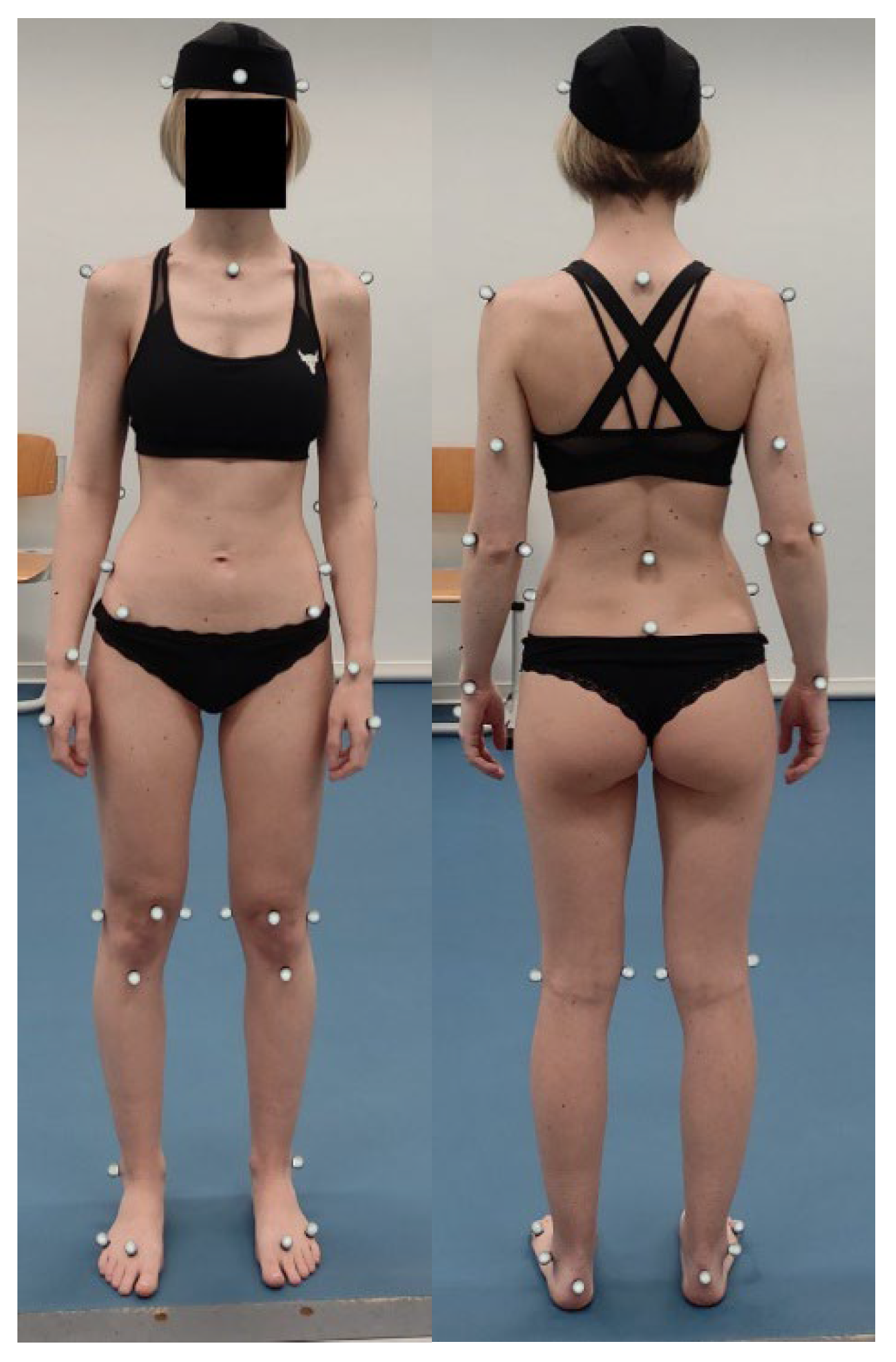

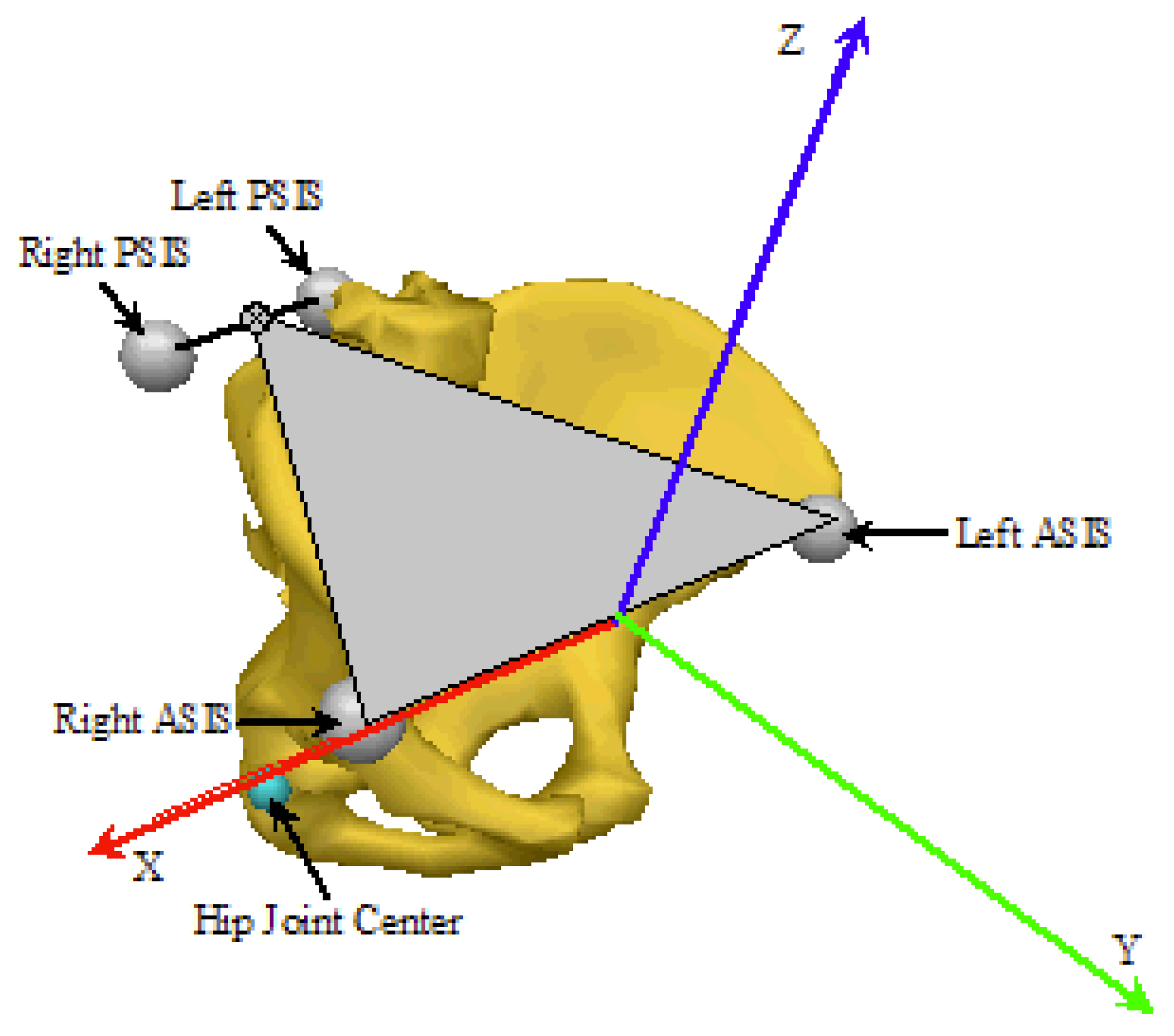

2.4. Kinematic Motion Analysis

2.5. Characteristics of the Exercise Intervention

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Data Analysis

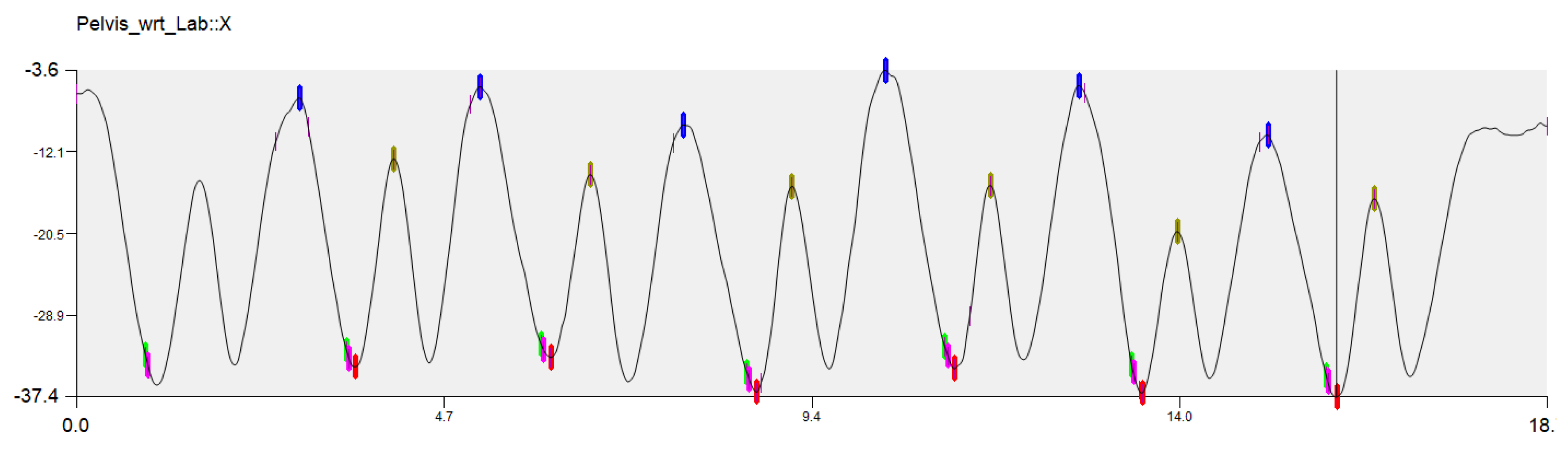

- Blue point—initial position of the pelvis before squat;

- Red point—maximum anterior pelvic tilt during the descending phase of the squat;

- Khaki point—pelvic position at maximum squat depth;

- Green point—pelvic position at 90° right hip flexion;

- Pink point—pelvic position at 90° of left hip flexion.

- Initial position of the pelvis before squat (blue point);

- PPT ROM during descending phase of the squat (difference between pelvic position at maximum squat depth—khaki point, and maximum anterior pelvic tilt during the descending phase of the squat—red point).

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Results of Physiotherapy Examination

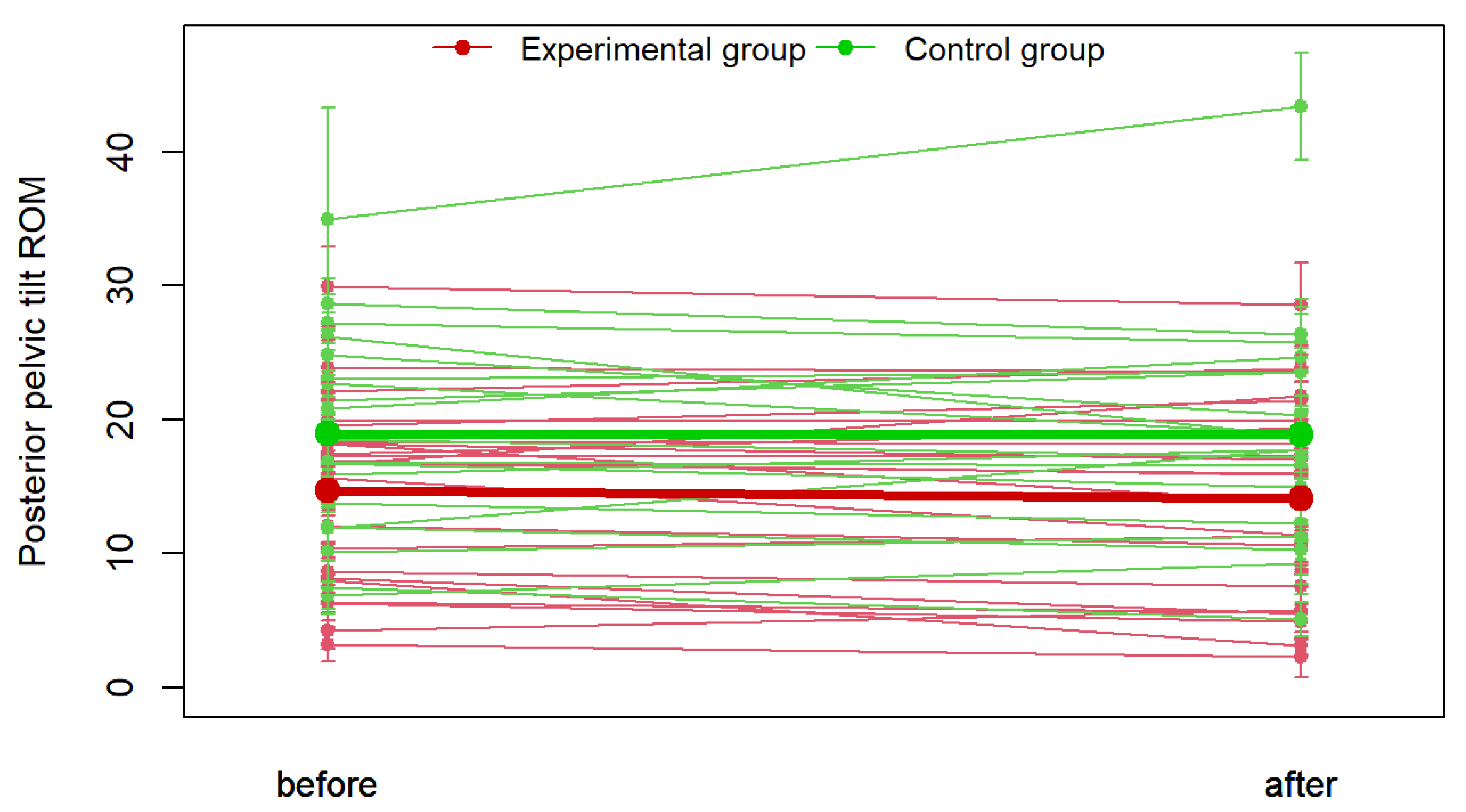

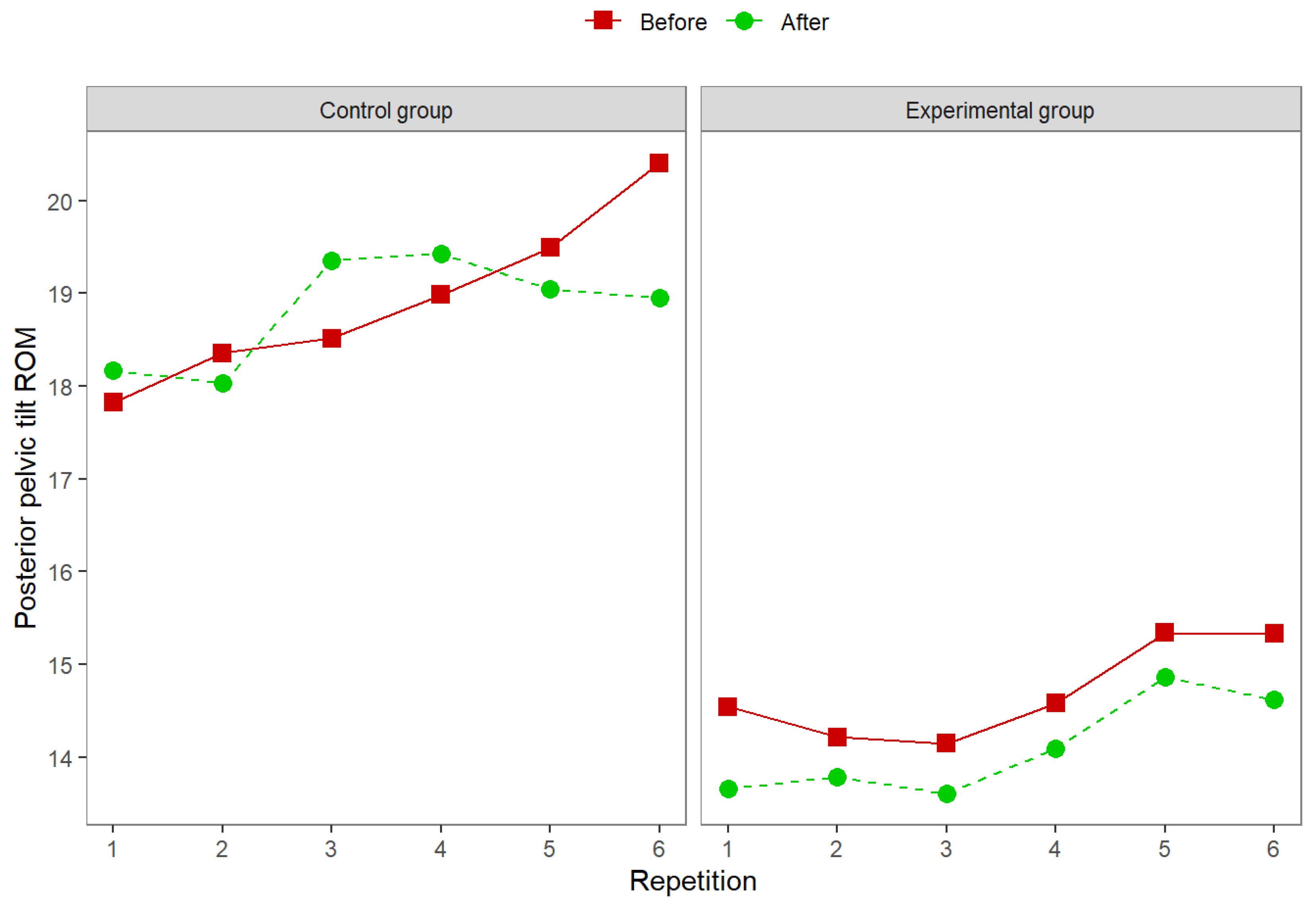

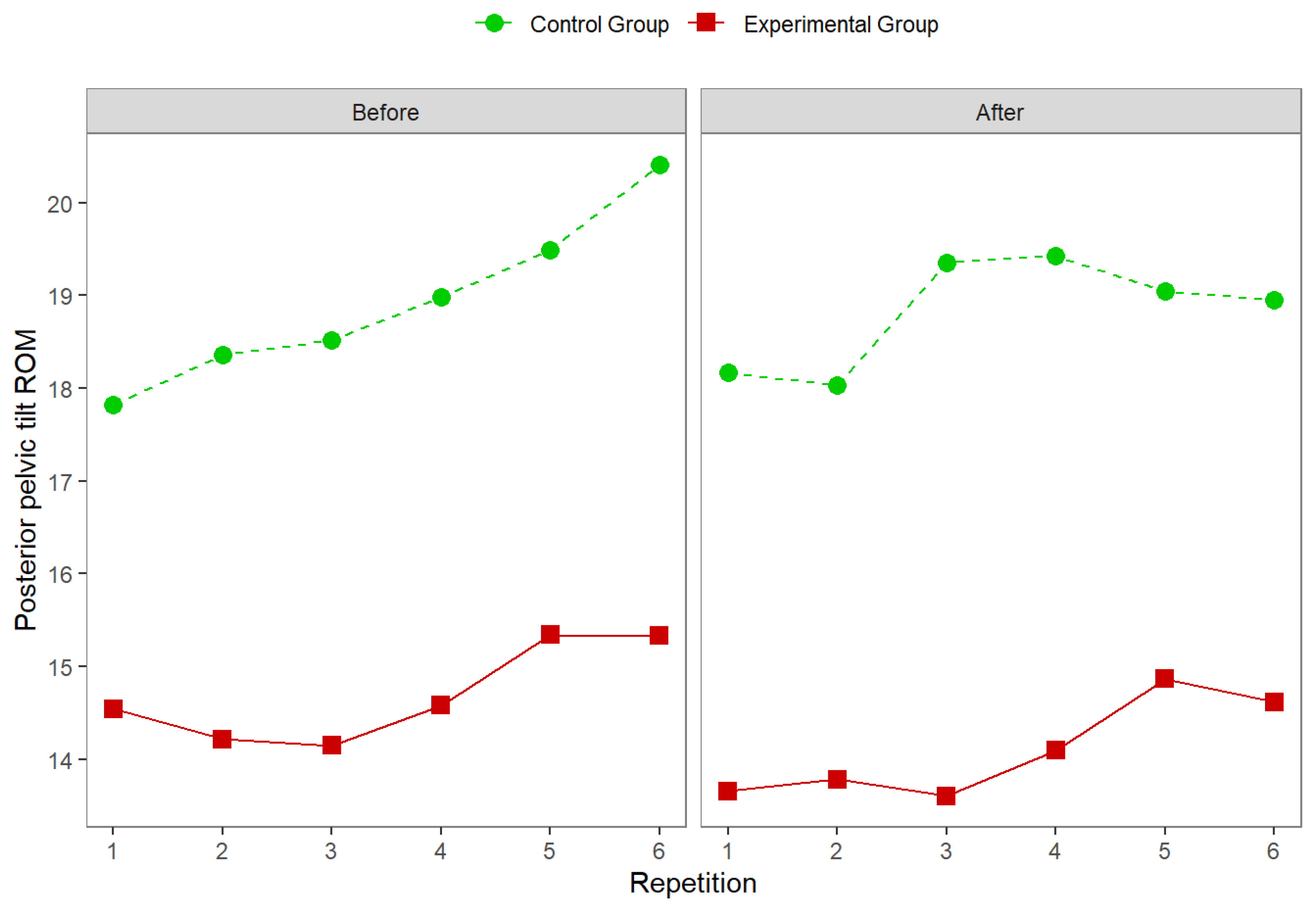

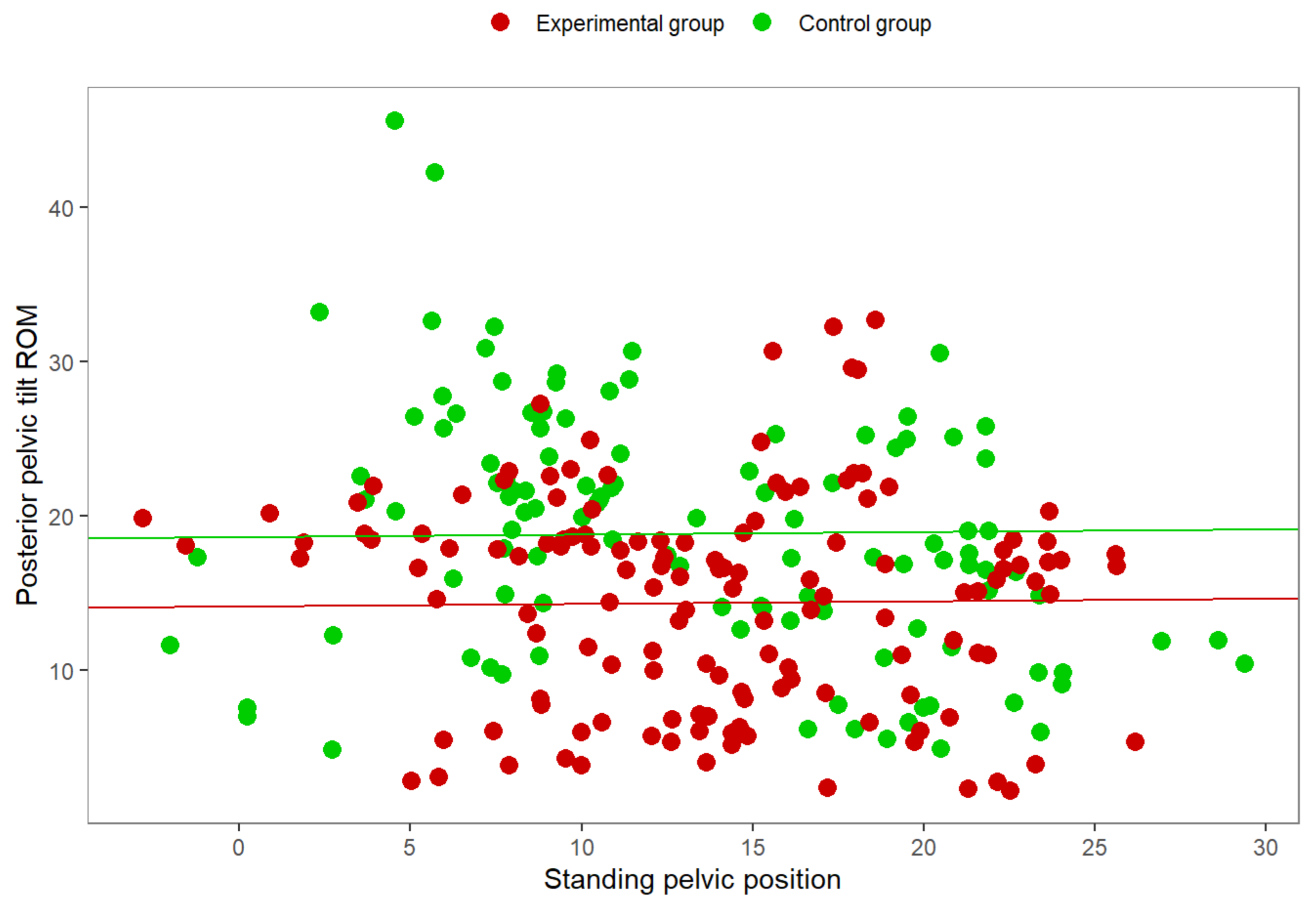

3.3. Results of the 3D Kinematic Motion Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PPT | Posterior pelvic tilt |

| 1RM | One repetition maximum |

| ROM | Range of motion |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| ASIP | Anterior superior iliac spine |

| PSIP | Posterior superior iliac spine |

| REML | Restricted Maximum Likelihood |

| rANOVA | Repeated measures analysis of variance |

| cm | Centimeter |

| FAI | Femoroacetabular impingement syndrome |

References

- Chelly, M.S.; Fathloun, M.; Cherif, N.; Amar, M.B.; Tabka, Z.; Van Praagh, E. Effects of a Back Squat Training Program on Leg Power, Jump, and Sprint Performances in Junior Soccer Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 2241–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebenson, C. Rehabilitation of the Spine: A Patient-Centered Approach, 3rd ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Fernandez, A.; Petros, P.E. A four month squatting-based pelvic exercise regime cures day/night enuresis and bowel dysfunction in children 7–11 years. Cent. Eur. J. Urol. 2020, 73, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, K.H.; Coburn, J.W.; Costa, P.B.; Pamukoff, D.N. Hip and Knee Kinetics During a Back Squat and Deadlift. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 1364–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Styles, W.J.; Matthews, M.J.; Comfort, P. Effects of Strength Training on Squat and Sprint Performance in Soccer Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 1534–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myer, G.D.; Kushner, A.M.; Brent, J.L.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Hugentobler, J.; Lloyd, R.S.; Vermeil, A.; Chu, D.A.; Harbin, J.; McGill, S.M. The Back Squat: A Proposed Assessment of Functional Deficits and Technical Factors That Limit Performance. Strength Cond. J. 2014, 36, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Bottom Position of Your Squat: A Defining Characteristic of Your Human Existence. Juggernaut Training Systems. Available online: https://www.jtsstrength.com/bottom-position-squat-defining-characteristic-human-existence/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Nielsen, S.R. Posterior Pelvic Tilt in Barbell Back Squats: A Biomechanical Analysis. Master’s Thesis, Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, Oslo, Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Todoroff, M. Dynamic Deep Squat: Lower-Body Kinematics and Considerations Regarding Squat Technique, Load Position, and Heel Height. Strength Cond. J. 2017, 39, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vašíčková, L. Sezení ve Vozíku: Zvýšení Pohybového Potenciálu a Prevence Komplikací, 1st ed.; Grada: Prague, Czech Republic, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, J.M.; Fetto, J.; Rosen, E. Musculoskeletal Examination, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- What is Pelvic Tilt & How Do You Fix it? National Academy of Sports Medicine. Available online: https://blog.nasm.org/what-is-pelvic-tilt-how-do-you-fix-it (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- McGill, S. Back Mechanic: The Step-By-Step McGill Method to Fix Back Pain, 1st ed.; Stuart McGill: Waterloo, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sedláková, S. Záda, Která Cvičí, Nebolí: Cvičíme Podle Ludmily Mojžíšové, 5th ed.; Vyšehrad: Prague, Czech Republic, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, B.; Schoenfeld, B. To Crunch or Not to Crunch: An Evidence-Based Examination of Spinal Flexion Exercises, Their Potential Risks, and Their Applicability to Program Design. Strength Cond. J. 2011, 33, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, H.; Wirth, K.; Klusemann, M. Analysis of the Load on the Knee Joint and Vertebral Column with Changes in Squatting Depth and Weight Load. Sports Med. 2013, 43, 993–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comfort, P.; McMahon, J.J.; Suchomel, T.J. Optimizing Squat Technique-Revisited. Strength Cond. J. 2018, 40, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B.J. Squatting Kinematics and Kinetics and Their Application to Exercise Performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 3497–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagwell, J.J.; Snibbe, J.; Gerhardt, M.; Powers, C.M. Hip kinematics and kinetics in persons with and without cam femoroacetabular impingement during a deep squat task. Clin. Biomech. 2016, 31, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catelli, D.S.; Kowalski, E.; Beaulé, P.E.; Smit, K.; Lamontagne, M. Asymptomatic Participants With a Femoroacetabular Deformity Demonstrate Stronger Hip Extensors and Greater Pelvis Mobility During the Deep Squat Task. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2018, 6, 2325967118782484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catelli, D.S.; Kowalski, E.; Beaulé, P.E.; Lamontagne, M. Muscle and Hip Contact Forces in Asymptomatic Men With Cam Morphology During Deep Squat. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 716626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolber, M.J.; Feldstein, A.P.; Masaracchio, M.; Liu, X.; Hanney, W.J. Influence of Femoral Acetabular Impingement on Squat Performance. Strength Cond. J. 2018, 40, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, K.; Hamai, S.; Higaki, H.; Gondo, H.; Ikebe, S.; Nakashima, Y. Pre- and post-operative evaluation of pincer-type femoroacetabular impingement during squat using image-matching techniques: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2018, 42, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, E.O.; Howell, D.R.; Borg, D.R.; Sugimoto, D.; Meehan, W.P. Functional Deep Squat Performance is Associated with Hip and Ankle Range of Motion. J. Athl. Enhanc. 2016, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, B. Bodyweight Strength Training Anatomy, 1st ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-H.; Kwon, O.-Y.; Park, K.-N.; Jeon, I.-C.; Weon, J.-H. Lower Extremity Strength and the Range of Motion in Relation to Squat Depth. J. Hum. Kinet. 2015, 45, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straub, R.K.; Powers, C.M. A Biomechanical Review of the Squat Exercise: Implications for Clinical Practice. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2024, 19, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, K.; Feit, M.K. Functional Training Anatomy, 1st ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Comfort, P.; McMahon, J.J.; Suchomel, T.J. Optimizing Squat Technique-Revisited. Strength Cond. J. 2018, 40, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Samukawa, M.; Kasahara, S.; Tohyama, H. The center of pressure position in combination with ankle dorsiflexion and trunk flexion is useful in predicting the contribution of the knee extensor moment during double-leg squatting. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 14, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B.J. Squatting Kinematics and Kinetics and Their Application to Exercise Performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 3497–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt Wink. Available online: https://startingstrength.com/training/butt-wink (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Braidot, A.A.; Brusa, M.H.; Lestussi, F.E.; Parera, G.P. Biomechanics of front and back squat exercises. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2007, 90, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edington, C.P. Lumbar Spine Kinematics and Kinetics During Heavy Barbell Squat and Deadlift Variations. Master’s Thesis, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Masi, M. Hack Your Squat: Learn how to identify fundamental flaws in the back squat and fix them so you and your clients can get back to safely training and performing at maximum potential!, 1st ed.; 2020.

- Stoppani, J. Jim Stoppani’s Encyclopedia of Muscle & Strength, 1st ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, M.S.; Kim, S.T.; Shin, S.; Jeon, S.M. Squat Posture and Spinopelvic parameters—Radiographic Assessment. J. Musculoskelet. Res. 2021, 24, 2150001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKean, M.R.; Dunn, P.K.J.; Burkett, B. The Lumbar and Sacrum Movement Pattern During the Back Squat Exercise. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 2731–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulsen, F.; Waschke, J. Sobotta Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System, 16th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pirola, V. Handbook of Kinesiology: Functional Anatomy, Biomechanics, Assessment of Joints and Muscles, 1st ed.; Edra Publishing: Palm Beach Gardens, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon, R.W. Cinematographic Analysis of the Passive Straight-Leg-Raising Test for Hamstring Muscle Length. Phys. Ther. 1982, 62, 1269–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R.W.; Gajdosik, R.L.; LeVeau, B.F. Relationship of Pelvic and Thigh Motions During Unilateral and Bilateral Hip Flexion. Phys. Ther. 1985, 65, 1501–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewberry, M.J.; Bohannon, R.W.; Tiberio, D.; Murray, R.; Zannotti, C.M. Pelvic and femoral contributions to bilateral hip flexion by subjects suspended from a bar. Clin. Biomech. 2003, 18, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.; Bohannon, R.; Tiberio, D.; Dewberry, M.; Zannotti, C. Pelvifemoral rhythm during unilateral hip flexion in standing. Clin. Biomech. 2002, 17, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohannon, R.W.; Bass, A. Research describing pelvifemoral rhythm: A systematic review. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2017, 29, 2039–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelvic Tilt and Squats: Butt Winking and Posterior Pelvic Tilt. Available online: https://theprehabguys.com/pelvic-tilt-and-squat-depth/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- How Anterior Pelvic Tilt Influences Your Squat Depth. Available online: https://www.primalmobility.com/blog/how-anterior-pelvic-tilt-affects-squat-depth (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Petr, M.; Šťastný, P. Funkční Silový Trénink, 1st ed.; Univerzita Karlova v Praze, Fakulta Tělesné Výchovy a Sportu: Prague, Czech Republic, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tlapák, P. Tvarování Těla pro Muže a Ženy, 11th ed.; ARSCI: Prague, Czech Republic, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Beat Butt Wink: Squat Big Without Hurting Your Back. Available online: https://www.bodybuilding.com/content/beat-butt-wink-squat-big-without-hurting-your-back.html (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Kushner, A.M.; Brent, J.L.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Hugentobler, J.; Lloyd, R.S.; Vermeil, A.; Chu, D.A.; Harbin, J.; McGill, S.M.; Myer, G.D. The Back Squat: Targeted Training Techniques to Correct Functional Deficits and Technical Factors That Limit Performance. Strength Cond. J. 2015, 37, 13–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitow, L. Palpation and Assessment in Manual Therapy: Learning the Art and Refining Your Skills, 4th ed.; Handspring Publishing: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lewit, K. Manipulační Léčba, 6th ed.; Euromedia: Prague, Czech Republic, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Malanga, G.A.; Mautner, K. Musculoskeletal Physical Examination: An Evidence-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Haladová, E.; Nechvátalová, L. Vyšetřovací Metody Hybného Systému, 3rd ed.; Národní Centrum Ošetřovatelství a Nelékařských Zdravotnických Oborů: Brno, Czech Republic, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Berryman Reese, N.; Bandy, W.D. Joint Range of Motion and Muscle Length Testing, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, D.C.; Azen, S.P.; Lin, C.-M.; Spence, C.; Baron, C.; Lee, L. Reliability of Goniometric Measurements. Phys. Ther. 1978, 58, 1355–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandbhir, V.N.; Cunha, B. Goniometer; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, CA, USA, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558985/.

- Powden, C.J.; Hoch, J.M.; Hoch, M.C. Reliability and minimal detectable change of the weight-bearing lunge test: A systematic review. Man. Ther. 2015, 20, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horschig, A.; Sonthana, K.; Neff, T. The Squat Bible: The Ultimate Guide to Mastering the Squat and Finding Your True Strength; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valle, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kališko, O.; Ježková, A. Metody kinezioterapie I: Učební Text, 1st ed.; Univerzita, J.E., Ed.; Purkyně v Ústí nad Labem, Fakulta Zdravotnických Studií: Ústí nad Labem, Czech Republic, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Laslett, M. Evidence-Based Diagnosis and Treatment of the Painful Sacroiliac Joint. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 16, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Wurff, P.; Buijs, E.J.; Groen, G.J. A Multitest Regimen of Pain Provocation Tests as an Aid to Reduce Unnecessary Minimally Invasive Sacroiliac Joint Procedures. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2006, 87, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, V.; Herbenová, A.; Jandová, J.; Pavlů, D. Svalové Funkční Testy. Grada: Prague, Czech Republic, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hardcastle, P.; Nade, S. The significance of the Trendelenburg test. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 1985, 67-B, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 66. Naqvi, U.; Sherman, A.L. Muscle Strength Grading; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, CA, USA, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK436008/.

- Kolář, P.; Bitnar, P.; Horáček, O.; Dyrhonová, O.; Kříž, J. Rehabilitace v Klinické Praxi, 2nd ed.; Galén: Prague, Czech Republic, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel, P. Hluboký Stabilizační Systém Páteře a Bolest Zad, 1st ed.; Grada: Prague, Czech Republic, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J.; Aasa, U.; Berglund, L. How accurate are visual assessments by physical therapists of lumbo-pelvic movements during the squat and deadlift? Phys. Ther. Sport 2021, 50, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, M.A.; Whelan, D.F.; Ward, T.E.; Delahunt, E.; Caulfield, B.M. Technology in Strength and Conditioning: Assessing Bodyweight Squat Technique With Wearable Sensors. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 2303–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclachlan, L.; White, S.G.; Reid, D. Observer Rating Versus Three-Dimensional Motion Analysis of Lower Extremity Kinematics During Functional Screening Tests: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2015, 10, 482–492. [Google Scholar]

- Blache, Y.; Bobbert, M.; Argaud, S.; de Fontenay, B.P.; Monteil, K.M. Measurement of Pelvic Motion Is a Prerequisite for Accurate Estimation of Hip Joint Work in Maximum Height Squat Jumping. J. Appl. Biomech. 2013, 29, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, J.; Brooks, D.; Atkins, S. An examination of the hamstring and the quadriceps muscle kinematics during the front and back squat in males. Balt. J. Health Phys. Act. 2017, 9, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwell, D.J.; Petersen, S.A.; Beach, T.A.C.; Graham, R.B. The effects of squatting footwear on three-dimensional lower limb and spine kinetics. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2016, 31, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sint Jan, S.V. Color Atlas of Skeletal Landmark Definitions: Guidelines for Reproducible Manual and Virtual Palpations; Churchill Livingstone: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Swinton, P.A.; Lloyd, R.; Keogh, J.W.L.; Agouris, I.; Stewart, A.D. A Biomechanical Comparison of the Traditional Squat, Powerlifting Squat, and Box Squat. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 1805–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escamilla, R.F.; Fleisig, G.S.; Lowry, T.M.; Barrentine, S.W.; Andrews, J.R. A three-dimensional biomechanical analysis of the squat during varying stance widths. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 984–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erman, B.; Vural, F.; Dopsaj, M.; Ozkol, M.Z.; Kose, D.E.; Aksit, T.; Cè, E. The effects of fatigue on linear and angular kinematics during bilateral squat. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, R.A.; Lee, T.D.; Winstein, C.; Wulf, G.; Zelaznik, H.N. Motor Control and Learning: A Behavioral Emphasis, 6th ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, B.K.; Carty, C.P.; Horan, S.A. Effect of sex and fatigue on single leg squat kinematics in healthy young adults. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2015, 16, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mang, Z.; Kravitz, L.; Beam, J. Transfer Between Lifts: Increased Strength in Untrained Exercises. Strength Cond. J. 2022, 44, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadono, N.; Tsuchiya, K.; Uematsu, A.; Kamoshita, H.; Kiryu, K.; Hortobágyi, T.; Suzuki, S. A Japanese Stretching Intervention Can Modify Lumbar Lordosis Curvature. Clin. Spine Surg. A Spine Publ. 2017, 30, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçay, B.; Çolak, T.K.; Apti, A.; Çolak, İ. The Immediate Effect of Hanging Exercise and Muscle Cylinder Exercise on the Angle of Trunk Rotation in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; McGill, S. The effect of short-term isometric training on core/torso stiffness. J. Sports Sci. 2016, 35, 1724–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.-Z.; Kim, S.-Y. Immediate effect of trunk flexion and extension isometric exercise using an external compression device on electromyography of the hip extensor and trunk range of motion of healthy subjects. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 14, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, A.; Kaneoka, K.; Okubo, Y.; Shiraki, H. Immediate Effects of Different Trunk Exercise Programs on Jump Performance. Int. J. Sports Med. 2016, 37, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikezoe, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Nakamura, M.; Ichihashi, N. Effects of Low-Load, Higher-Repetition vs. High-Load, Lower-Repetition Resistance Training Not Performed to Failure on Muscle Strength, Mass, and Echo Intensity in Healthy Young Men: A Time-Course Study. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 3439–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usui, S.; Maeo, S.; Tayashiki, K.; Nakatani, M.; Kanehisa, H. Low-load Slow Movement Squat Training Increases Muscle Size and Strength but Not Power. Int. J. Sports Med. 2016, 37, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirono, T.; Kunugi, S.; Yoshimura, A.; Ueda, S.; Goto, R.; Akatsu, H.; Watanabe, K. Effects of home-based bodyweight squat training on neuromuscular properties in community-dwelling older adults. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2023, 35, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshiko, A.; Watanabe, K. Impact of home-based squat training with two-depths on lower limb muscle parameters and physical functional tests in older adults. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, D.-J.; Oh, H.-J.; Lee, S.-H. Effects of Sling Exercise on Pain, Trunk Strength, and Balance in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain. J. Korean Phys. Ther. 2022, 34, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, R.; Bloxham, S. A Systematic Review of the Effects of Exercise and Physical Activity on Non-Specific Chronic Low Back Pain. Healthcare 2016, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipczyk, P.; Filipczyk, K.; Saulicz, E. Influence of Stabilization Techniques Used in the Treatment of Low Back Pain on the Level of Kinesiophobia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Mesa, J.; González-Chica, D.A.; Duquia, R.P.; Bonamigo, R.R.; Bastos, J.L. Sampling: How to select participants in my research study? An. Bras. Dermatol. 2016, 91, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, K.; Thomas, S.V.; Suresh, G. Design, data analysis and sampling techniques for clinical research. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2011, 14, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdar, C.C.; Cihan, M.; Yücel, D.; Serdar, M.A. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: Simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochem. Medica 2021, 31, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tichý, M. Dysfunkce Kloubu: Podstata Konceptu Funkční Manuální Medicíny, 2nd ed.; Miroslav Tichý: Prague, Czech Republic, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harada, S.; Hamai, S.; Gondo, H.; Higaki, H.; Ikebe, S.; Nakashima, Y. Squatting After Total Hip Arthroplasty: Patient-Reported Outcomes and In Vivo Three-Dimensional Kinematic Study. J. Arthroplast. 2022, 37, 734–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, T.M.; Saxby, D.J.; Pizzolato, C.; Savage, T.; Bennell, K.; Dickenson, E.; Eyles, J.; Foster, N.; Hall, M.; Hunter, D.; et al. Squatting biomechanics following physiotherapist-led care or hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement syndrome: A secondary analysis from a randomised controlled trial. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, D.; Nakashima, Y.; Hamai, S.; Higaki, H.; Ikebe, S.; Shimoto, T.; Hirata, M.; Kanazawa, M.; Kohno, Y.; Iwamoto, Y. Kinematic Analysis of Healthy Hips during Weight-Bearing Activities by 3D-to-2D Model-to-Image Registration Technique. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 457573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogenboom, B.J.; May, C.J.; Alderink, G.J.; Thompson, B.S.; Gilmore, L.A. Three-Dimensional Kinematics and Kinetics of the Overhead Deep Squat in Healthy Adults: A Descriptive Study. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Exercise | Description | Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Cat/Cow | Assume quadruped position on knees and hands. Practice alternating from rounded back posture to arched back posture. | Identify difference between lordotic and kyphotic positions. |

| Ball Wall Squat | Pin a ball (similar to small Swiss ball) between the lower back and wall. Squat down while keeping ball pinned against the wall. The ball will roll up to the shoulder blades. Ascend and repeat. | Exercise facilitates a more vertical trunk position because horizontal force from wall serves as assistance. Ball rolling encourages the correct spinal curve. |

| Pole Squat and Fix | Perform squat near a sturdy pole or column. At apex of squat, use column as assistance to pull torso into correct position and hold. Heels must remain on the ground. | Assistance to help athlete self-generate and learn correct deep hold position. |

| Plank | Hold plank position with emphasis on maintaining lordosis throughout exercise. | Improve isometric strength of the back musculature and promote correct lumbar spine position. |

| Superman | Lay flat on stomach with your arms straight out in front and legs straight out behind. Keep arms and legs shoulder-width apart for the duration of the exercise. Lift your legs and arms simultaneously at least 6 inches off the ground. Keep each movement slow and controlled to prevent pulling muscles. | Strengthen the lower back musculature. |

| Overhead Squat | Perform squat with dowel in overhand grip overhead with elbows extended. | Strengthen back musculature and promote erect trunk during squat. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).