Introduction

Ewing sarcoma (ES) is the second most common primary bone malignancy in children and adolescents after osteosarcoma [

1,

2]. Approximately 25% of patients present with metastatic disease at diagnosis, and despite advances in multimodality therapy, outcomes remain suboptimal: disease-related mortality occurs in 30–40% of patients with localized disease and up to 80% in those with metastatic disease [

3]. Interval-compressed VDC/IE administered every 14 days has improved frontline management of metastatic ES [

4,

5]; however, relapse remains common within the first two years, and late recurrences are also observed [

6,

7,

8]. These challenges underscore the need for more effective consolidation strategies to improve long-term outcomes.

High-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem-cell transplantation (HDCT–ASCT) has been explored as a potential approach for high-risk and relapsed/refractory ES. While prospective trials, such as EWING 99 and EWING 2008, have reported mixed results with limited evidence for improved overall survival (OS) or event-free survival (EFS) and substantial treatment-related toxicity [

9,

10,

11], retrospective series have suggested that some patients may derive benefit from HDCT–ASCT, though findings are heterogeneous [

12,

13,

14,

15]. As a result, there remains uncertainty regarding which patients may truly benefit from this intensive but infrequently employed modality.

To address this knowledge gap, we conducted a single-center, retrospective study of patients with advanced ES who received HDCT–ASCT following at least one prior line of therapy. Our objectives were to characterize survival outcomes—including progression-free survival (PFS), post-transplant overall survival (OS-2), and OS—and to identify pragmatic prognostic factors such as age at diagnosis, primary tumor site, and metastatic organ involvement. By clarifying the impact of these clinical factors, our study aims to inform patient selection and optimize the use of HDCT–ASCT within current ES treatment paradigms.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a single-center, retrospective cohort study of patients with Ewing sarcoma who underwent high-dose chemotherapy followed by HDCT–ASCT. The analysis included all consecutive eligible patients with complete baseline and outcome data (N = 46). Eligibility criteria Inclusion criteria were: (i) histologically confirmed disease; (ii) receipt of HDCT–ASCT per institutional protocol; and (iii) available demographics, disease characteristics, and follow-up sufficient to evaluate survival endpoints. Patients with missing key covariates or inadequate follow-up were excluded.

Data Collection and Covariates

From electronic records we abstracted age at diagnosis, sex, stage at presentation (locally advanced vs metastatic), primary tumor site (upper extremity, lower extremity, vertebra, pelvis, soft tissue), baseline metastatic involvement (lung, liver, bone, brain; coded as binary variables), and number of prior systemic therapy lines before HDCT–ASCT (≤2 vs >2). Transplant-related parameters included collected stem-cell count and engraftment/recovery metrics.

Transplant Procedures and Definitions

All patients received high-dose ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide) as the conditioning regimen prior to ASCT, per institutional practice. Supportive care was delivered according to institutional standards; regimens were not uniform across ancillary measures and were not compared. Engraftment was defined as the first of three consecutive days on which either the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) exceeded 2,000/µL or the platelet count exceeded 20,000/µL, in the absence of exogenous support (i.e., without G-CSF administration or platelet transfusion). Engraftment duration was calculated as the number of days from ASCT to that first qualifying day. The collected stem-cell dose was recorded as the total product collected prior to ASCT.

Endpoints

Three time-to-event outcomes were prespecified: Overall survival (OS): time from diagnosis to death from any cause; survivors were censored at last follow-up. Post-transplant overall survival (OS-2): time from ASCT to death. Progression-free survival (PFS): time from ASCT to first objective progression/relapse or death, whichever occurred first.

Statistical Analysis

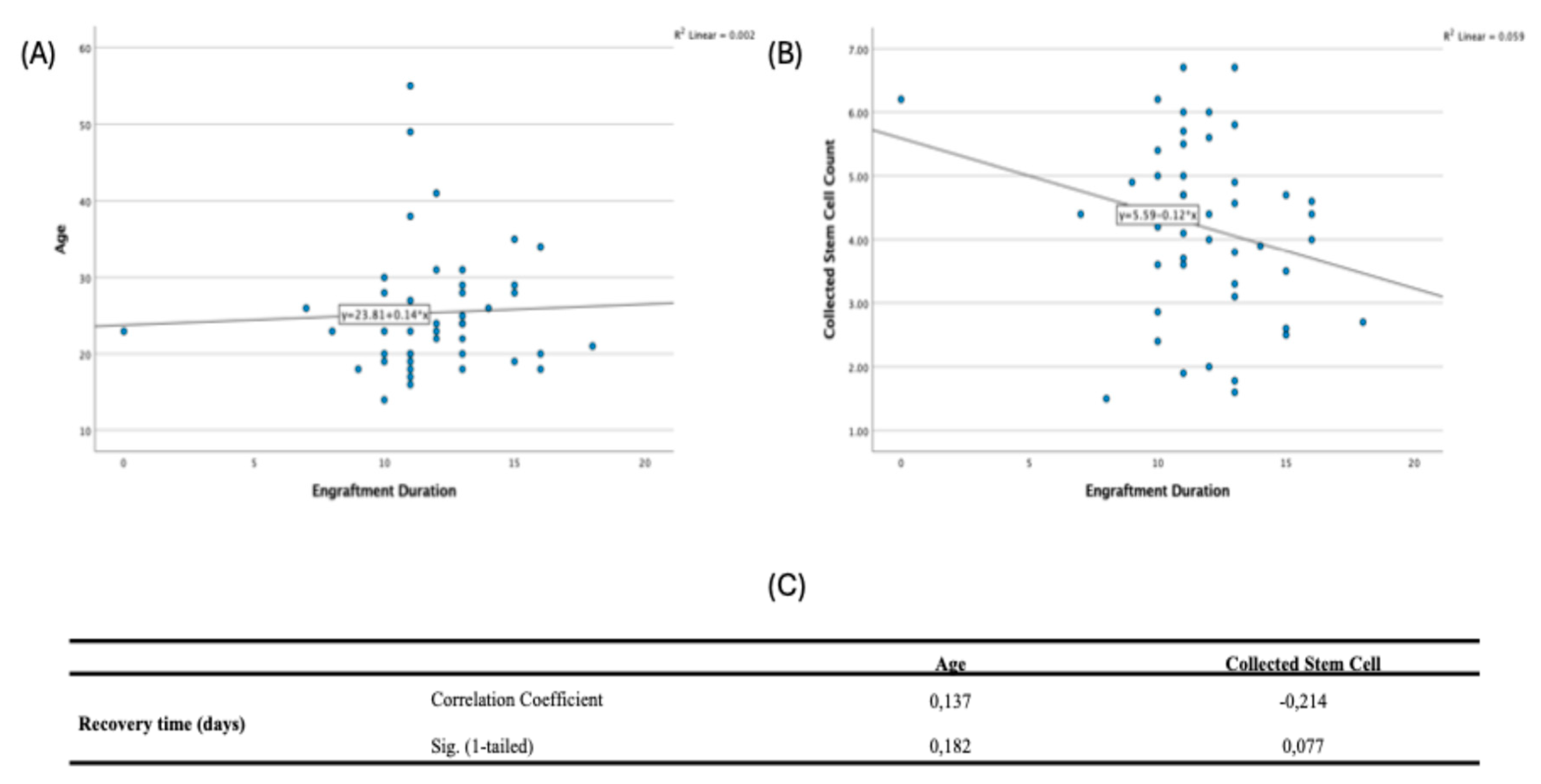

Baseline characteristics are summarized as counts/percentages or medians with ranges. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by log-rank tests. To evaluate prognostic factors, we fitted Cox proportional hazards models for each endpoint. For models assessing primary tumor site, upper extremity served as the reference category; for models assessing metastatic site, each organ site (lung, liver, bone, brain) was entered as a binary covariate. Proportional-hazards assumptions were checked by visual inspection of log–log plots and Schoenfeld-type diagnostics. Correlations among age at diagnosis, collected stem-cell count, and recovery time were examined using Spearman’s rank correlation (one-tailed p-values reflecting directional hypotheses). All other tests were two-sided with α = 0.05. Analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics v27.

Results

Among 46 patients, the median age at diagnosis was 23.5 years (range 14–55); 32 (69.6%) were male. At presentation, 36 (78.3%) had locally advanced and 10 (21.7%) had metastatic disease. Primary sites were soft tissue in 16 (34.8%), lower extremity in 13 (28.3%), vertebra in 7 (15.2%), and pelvis or upper extremity in 5 (10.9%) each. Baseline metastases most frequently involved the lung (35; 76.1%) and bone (30; 65.2%), with less frequent liver (5; 10.9%) and brain (3; 6.5%) involvement. Before HDCT–ASCT, 37 (80.4%) had received ≤2 prior therapy lines (

Table 1).

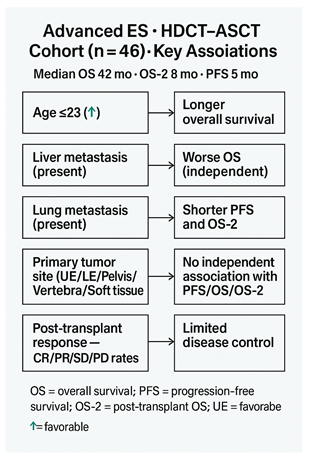

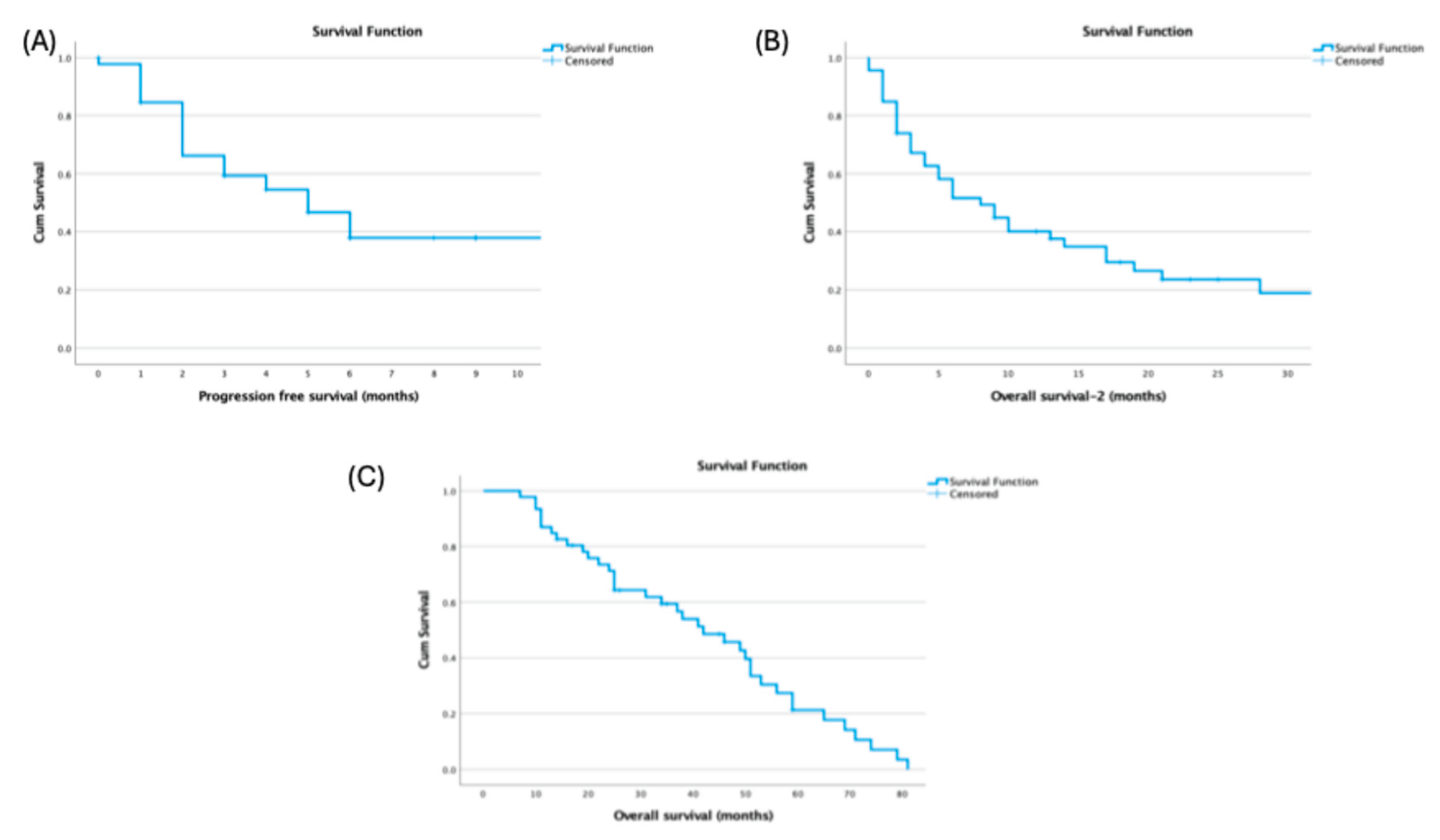

Median OS from diagnosis was 42.0 months (95% CI, 28.89–55.10), median progressioPFS after HDCT–ASCT was 5.0 months (95% CI, 2.89–7.11), and post-transplant OS-2 was 8.0 months (

Figure 1).

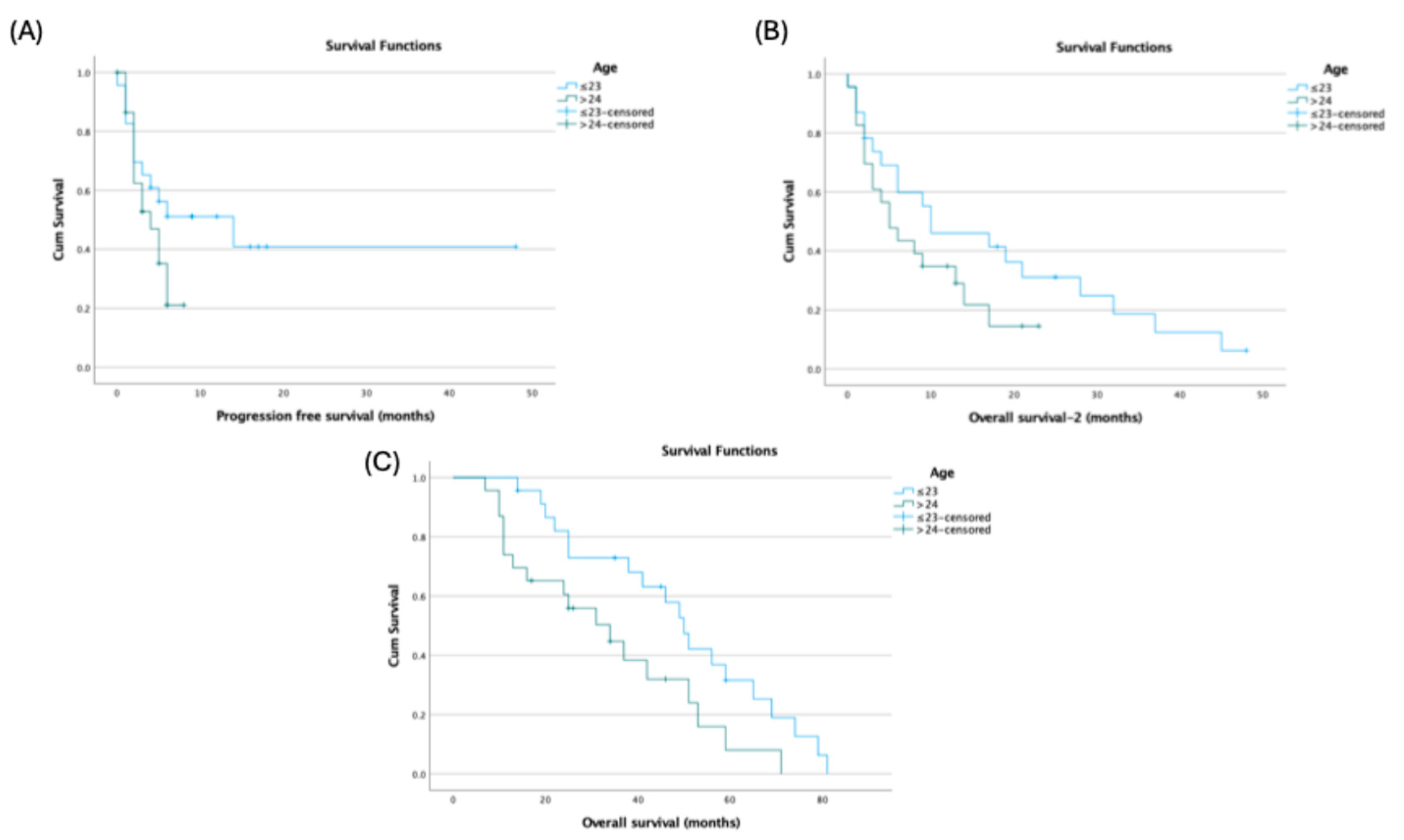

Age at diagnosis showed endpoint-specific differences: patients ≤23 years had longer PFS (14.0 vs 4.0 months; p=0.144) and OS-2 (10.0 vs 5.0 months; p=0.145) without statistical significance, but significantly longer OS (50.0 vs 34.0 months; 95% CI: 43.11–56.89 vs 16.70–51.30; p=0.027) (

Figure 2).

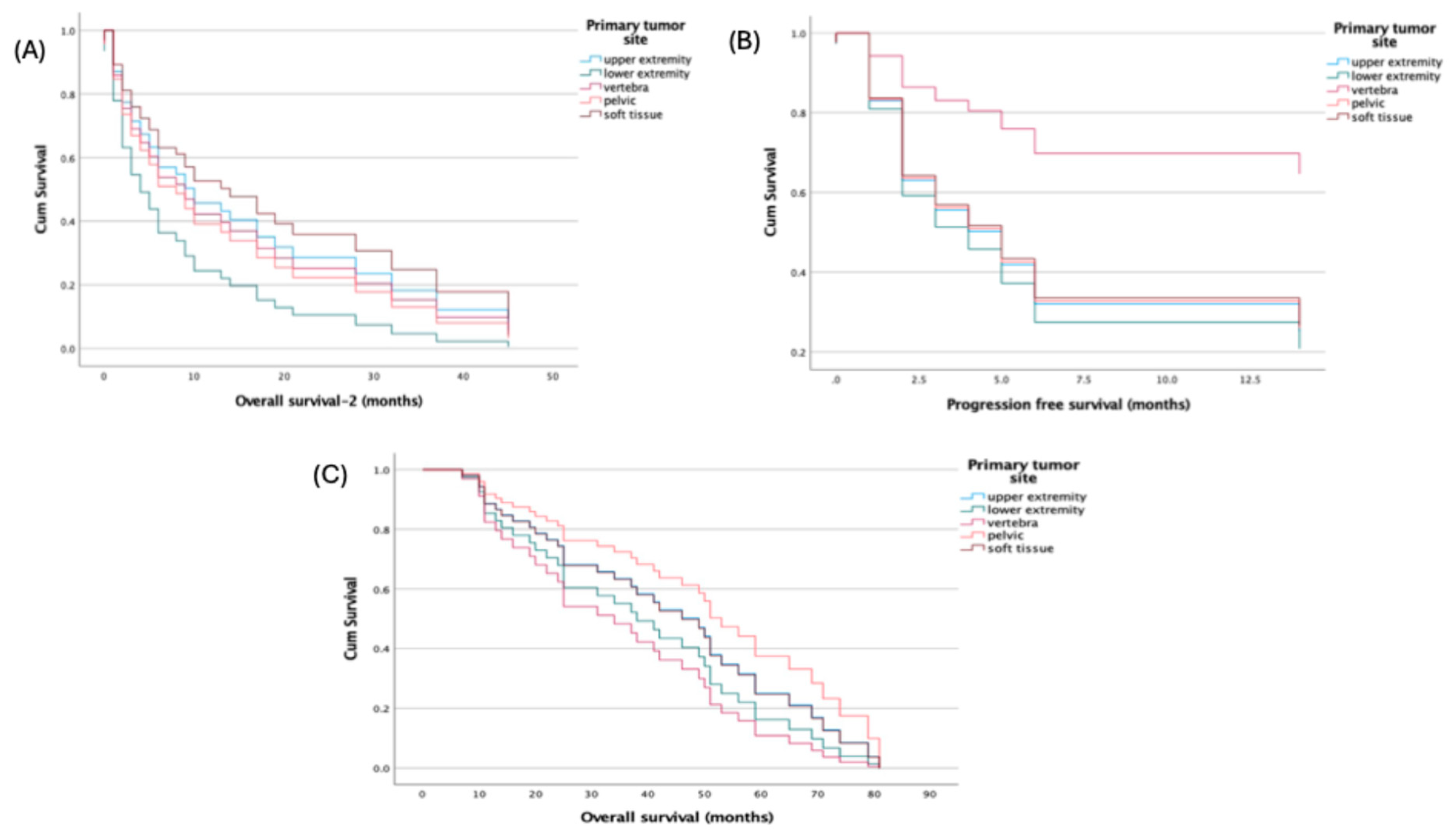

Primary tumor site was not associated with survival in multivariable Cox models using the upper extremity as reference: all hazard ratios for lower extremity, vertebra, pelvis, and soft tissue were near unity with non-significant p-values across PFS (HRs 0.316–1.137; p=0.213–0.981), OS (HRs 0.710–1.602; p=0.477–0.985), and OS-2 (HRs 0.818–1.799; p=0.313–0.884) (

Figure 3).

By contrast, metastatic site showed endpoint-specific effects. For OS, the model was significant overall (score χ²=12.182, df=4, p=0.016) and liver metastasis independently predicted worse survival (HR=5.411, 95% CI: 1.610–18.182; p=0.006), whereas lung, bone, and brain metastases were not significant. For OS-2, the overall model was not significant (χ²=6.779, p=0.148), but lung metastasis was associated with increased risk (HR=2.672, 95% CI: 1.131–6.311; p=0.025). For PFS, the score test approached significance (χ²=9.409, p=0.052) and the change-from-block test was significant (χ²=11.078, p=0.026); lung metastasis was the only significant covariate (HR=6.037, 95% CI: 1.390–26.230; p=0.016), while other sites were non-significant (

Table 2).

Spearman correlations showed no significant relationships among age at diagnosis, collected stem cell count, and recovery time: age vs stem cells (ρ=−0.056, p=0.355), age vs recovery (ρ=0.137, p=0.182), and stem cells vs recovery (ρ=−0.214, p=0.077) (

Figure 4).

Safety

The median recovery time after HDCT–ASCT was 11.5 months. Hematologic toxicities were universal, with febrile neutropenia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia occurring in 100% of patients, and anemia observed in 86.9%. Non-hematologic toxicities were also common, including mucositis/stomatitis in 65.2%, nausea/vomiting in 82.6%, and diarrhea in 78.2% of patients. Liver and renal toxicities were less frequent, affecting 21.7% and 17.3% of patients, respectively. Despite the high rate of treatment-related adverse events, the mortality rate was low, with only one patient (2.1%) succumbing to treatment-related complications (

Table 2)

| Toxicity |

n |

% |

| Febrile neutropenia |

46 |

%100 |

| Neutropenia |

46 |

%100 |

| Anemia |

40 |

%86.9 |

| Thrombocytopenia |

46 |

%100 |

| Mucositis/stomatitis |

30 |

%65.2 |

| Nausea/vomiting |

38 |

%82.6 |

| Diarrhea |

36 |

%78.2 |

| Liver toxicity |

10 |

%21.7 |

| Renal toxicity |

8 |

%17.3 |

| Death |

1 |

%2.1 |

Discussion

ES is a rare, biologically aggressive tumor that predominantly affects children and adolescents. In our cohort, the median age was 23 years, reflecting a young-adult population. Despite therapeutic advances, outcomes—particularly for patients with metastatic disease—remain suboptimal. We conducted a single-center, retrospective analysis of 46 patients with locally advanced or metastatic ES treated with high-dose chemotherapy followed by HDCT–ASCT, evaluating survival endpoints and examining clinicopathologic factors associated with OS and PFS.

Based on the Euro-EWING 99 and EWING 2008 results (≈287 patients across relevant cohorts), HDCT/ASCT did not improve survival in patients with isolated pulmonary metastases and was associated with greater acute toxicity; accordingly, this strategy has not been adopted as routine in that subgroup. By contrast, in localized high-risk ES, busulfan–melphalan (BuMel)–based HDCT/ASCT demonstrated clinically meaningful benefit in EFS/OS over standard consolidation, albeit with increased toxicity, and is therefore considered for carefully selected, fit patients in experienced centers rather than as universal standard therapy [

9]. In the EWING 2008 R3 trial (n=109), high-dose treosulfan–melphalan followed by HDCT/ASCT did not confer a significant improvement in EFS or OS and was associated with greater acute toxicity, although a prespecified subgroup signal suggested a 3-year EFS advantage in patients <14 years of age [

10].

For relapsed or refractory ES, several retrospective trials reported improved outcomes with HDCT-ASCT compared to conventional chemotherapy [

12,

13,

14,

15]. In a multicenter cohort by Rasper et al. (n = 239), HDCT/ASCT as consolidation was associated with higher 2-year EFS among chemosensitive patients; however, early relapse remained a strong adverse prognostic factor [

12]. In a cohort of 196 patients with refractory or recurrent Ewing sarcoma, Windsor et al. showed that HDCT–ASCT conferred a significantly longer median post-relapse survival than non–high-dose salvage therapy (standard-dose, transplant-free regimens): 76.0 vs 10.5 months. [

13]. Ferrari et al. demonstrated that achieving a second complete remission (CR2) was strongly prognostic for post-relapse survival [

14]. Shankar et al. found that disease-free interval (DFI) >2 years was the only independent predictor of improved survival [

15]. These studies collectively highlight that HDCT/ASCT may benefit carefully selected, chemosensitive patients, although heterogeneity in regimens and potential selection bias limit definitive conclusions.

In our cohort, median OS after diagnosis was 42 months, and post-transplant OS and PFS were 8 and 5 months, respectively, underscoring the aggressive nature of ES and the limited impact of HDCT–ASCT in altering disease trajectory. Younger age at diagnosis (≤23 years) was associated with significantly longer OS (50 months), suggesting better outcomes in younger patients, potentially due to comorbidities and treatment tolerance (9,10,16). Liver metastasis emerged as a critical prognostic factor for OS, whereas lung metastasis significantly affected PFS. Post-transplant radiologic evaluations showed complete response in 8.7%, partial response in 17.4%, stable disease in 15.2%, and progressive disease in 58.7%, indicating that HDCT–ASCT alone may be insufficient to control advanced ES (12–15,17).

Compared to other studies, our cohort exhibited a higher rate of disease progression, likely due to high tumor burden and multiple prior treatment lines. Literature reviews show that patients with high tumor burden and age >15 years have generally poorer outcomes, regardless of treatment approach (3,18–23). These findings emphasize the need for innovative strategies to improve post-transplant disease control, such as novel agents, immunotherapies, or maintenance therapies.

Highligts

Median OS after diagnosis: 42 months; post-transplant OS and PFS: 8 and 5 months, respectively. Younger age (≤23 years) associated with longer survival. Liver metastasis negatively affected OS; lung metastasis significantly affected PFS. Post-transplant radiologic response rates were low, with progressive disease observed in the majority of patients. Results emphasize the aggressive nature of ES and the limited impact of HDCT–ASCT in heavily pretreated or high tumor burden patients.

Limitations

Retrospective, single-center design limits generalizability and introduces potential selection bias. Small, heterogeneous patient population may affect the robustness of survival outcomes. Treatment regimens and prior therapies were not standardized, potentially influencing post-transplant outcomes. Lack of a control group limits causal inference regarding HDCT–ASCT efficacy. Long-term follow-up on late toxicities and quality of life was not systematically collected.

Future Perspectives

Future studies should clarify when HDCT–ASCT offers meaningful benefit in advanced ES through pragmatic, multicenter, risk-adapted designs that stratify by age (≤23 vs >23 years), metastatic pattern (especially liver vs lung), and chemosensitivity. Standardized conditioning and supportive care should be used across arms, with randomized or response-adapted comparisons of transplant versus non-transplant consolidation and evaluation of simple post-transplant maintenance approaches to prolong PFS/OS-2. Development and external validation of a parsimonious clinical risk score (age + organ involvement ± treatment response) and uniform reporting of toxicity and quality of life will be essential to guide patient selection and shared decision-making.

References

- Stiller CA, Bielack SS, Jundt G, Steliarova-Foucher E. Bone tumours in European children and adolescents, 1978-1997. Report from the Automated Childhood Cancer Information System project. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(13):2124-2135. [CrossRef]

- Bleyer A, O’leary M, Barr R, Ries LAG. Cancer epidemiology in older adolescents and young adults 15 to 29 years of age, including SEER incidence and survival: 1975-2000. Published online 2006. Accessed December 20, 2024. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20083188582.

- Cotterill SJ, Ahrens S, Paulussen M, et al. Prognostic Factors in Ewing’s Tumor of Bone: Analysis of 975 Patients From the European Intergroup Cooperative Ewing’s Sarcoma Study Group. JCO. 2000;18(17):3108-3114. [CrossRef]

- DuBois SG, Krailo MD, Glade-Bender J, et al. Randomized Phase III Trial of Ganitumab With Interval-Compressed Chemotherapy for Patients With Newly Diagnosed Metastatic Ewing Sarcoma: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(11):2098-2107. [CrossRef]

- Brennan B, Kirton L, Marec-Bérard P, et al. Comparison of two chemotherapy regimens in patients with newly diagnosed Ewing sarcoma (EE2012): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10362):1513-1521. [CrossRef]

- Weston CL, Douglas C, Craft AW, Lewis IJ, Machin D. Establishing long-term survival and cure in young patients with Ewing’s sarcoma. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(2):225-232. [CrossRef]

- Bacci G, Balladelli A, Forni C, et al. Adjuvant and neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for Ewing’s sarcoma family tumors and osteosarcoma of the extremity: further outcome for patients event-free survivors 5 years from the beginning of treatment. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(12):2037-2040. [CrossRef]

- Wasilewski-Masker K, Liu Q, Yasui Y, et al. Late recurrence in pediatric cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(24):1709-1720. [CrossRef]

- Dirksen U, Brennan B, Le Deley MC, et al. High-Dose Chemotherapy Compared With Standard Chemotherapy and Lung Radiation in Ewing Sarcoma With Pulmonary Metastases: Results of the European Ewing Tumour Working Initiative of National Groups, 99 Trial and EWING 2008. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(34):3192-3202. [CrossRef]

- Koch R, Gelderblom H, Haveman L, et al. High-Dose Treosulfan and Melphalan as Consolidation Therapy Versus Standard Therapy for High-Risk (Metastatic) Ewing Sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(21):2307-2320. [CrossRef]

- Haveman LM, van Ewijk R, van Dalen EC, et al. High-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous haematopoietic cell transplantation for children, adolescents, and young adults with primary metastatic Ewing sarcoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;9(9):CD011405. [CrossRef]

- Rasper M, Jabar S, Ranft A, Jürgens H, Amler S, Dirksen U. The value of high-dose chemotherapy in patients with first relapsed Ewing sarcoma. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2014;61(8):1382-1386. [CrossRef]

- Windsor R, Hamilton A, McTiernan A, et al. Survival after high-dose chemotherapy for refractory and recurrent Ewing sarcoma. European Journal of Cancer. 2022;170:131-139. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari S, Luksch R, Hall KS, et al. Post-relapse survival in patients with Ewing sarcoma. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2015;62(6):994-999. [CrossRef]

- Shankar AG, Ashley S, Craft AW, Pinkerton CR. Outcome after relapse in an unselected cohort of children and adolescents with Ewing sarcoma. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;40(3):141-147. [CrossRef]

- Whelan J, Le Deley MC, Dirksen U, et al. High-Dose Chemotherapy and Blood Autologous Stem-Cell Rescue Compared With Standard Chemotherapy in Localized High-Risk Ewing Sarcoma: Results of Euro-E.W.I.N.G.99 and Ewing-2008. JCO. 2018;36(31):3110-3119. [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich B, Ahrens S, Burdach S, et al. [High-dosage chemotherapy in primary metastasized and relapsed Ewing’s sarcoma. (EI)CESS]. Klin Padiatr. 1999;211(4):284-290. [CrossRef]

- Ahrens S, Hoffmann C, Jabar S, et al. Evaluation of prognostic factors in a tumor volume-adapted treatment strategy for localized Ewing sarcoma of bone: the CESS 86 experience. Cooperative Ewing Sarcoma Study. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;32(3):186-195. [CrossRef]

- Bacci G, Ferrari S, Bertoni F, et al. Prognostic factors in nonmetastatic Ewing’s sarcoma of bone treated with adjuvant chemotherapy: analysis of 359 patients at the Istituto Ortopedico Rizzoli. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(1):4-11. [CrossRef]

- Craft A, Cotterill S, Malcolm A, et al. Ifosfamide-containing chemotherapy in Ewing’s sarcoma: The Second United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group and the Medical Research Council Ewing’s Tumor Study. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(11):3628-3633. [CrossRef]

- Jürgens H, Exner U, Gadner H, et al. Multidisciplinary treatment of primary Ewing’s sarcoma of bone. A 6-year experience of a European Cooperative Trial. Cancer. 1988;61(1):23-32. [CrossRef]

- McLean TW, Hertel C, Young ML, et al. Late events in pediatric patients with Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone: the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Children’s Hospital experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1999;21(6):486-493.

- Paulussen M, Craft AW, Lewis I, et al. Results of the EICESS-92 Study: Two Randomized Trials of Ewing’s Sarcoma Treatment—Cyclophosphamide Compared With Ifosfamide in Standard-Risk Patients and Assessment of Benefit of Etoposide Added to Standard Treatment in High-Risk Patients. JCO. 2008;26(27):4385-4393. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).