Clinical and experimental observations indicate that exposure to certain psychotropic drugs, withdrawal states, and stimulant overdose can precipitate network hyperexcitability and, in some cases, seizures or cognitive/affective disturbances. While individual episodes of excessive firing are often transient, accumulating evidence suggests that inadequate metabolic compensation can convert these episodes into persistent mitochondrial dysfunction—principally via Ca²⁺ overload, mPTP activation, and ROS-mediated mtDNA/ETC damage—thus producing enduring physiological and structural deficits.

Most studies focus on a single scale (molecular/cellular, slice, animal, or clinical measurement), leaving a gap in causal chain validation across scales—from network discharge to mitochondrial failure to system-level dysfunction. In addition, standardized, sensitive biomarkers to detect focal neuronal ATP deficits in humans are limited, complicating translational inference. To evaluate how pharmacological exposures influence disease risk or progression, we need an integrative mechanistic framework that is experimentally tractable.

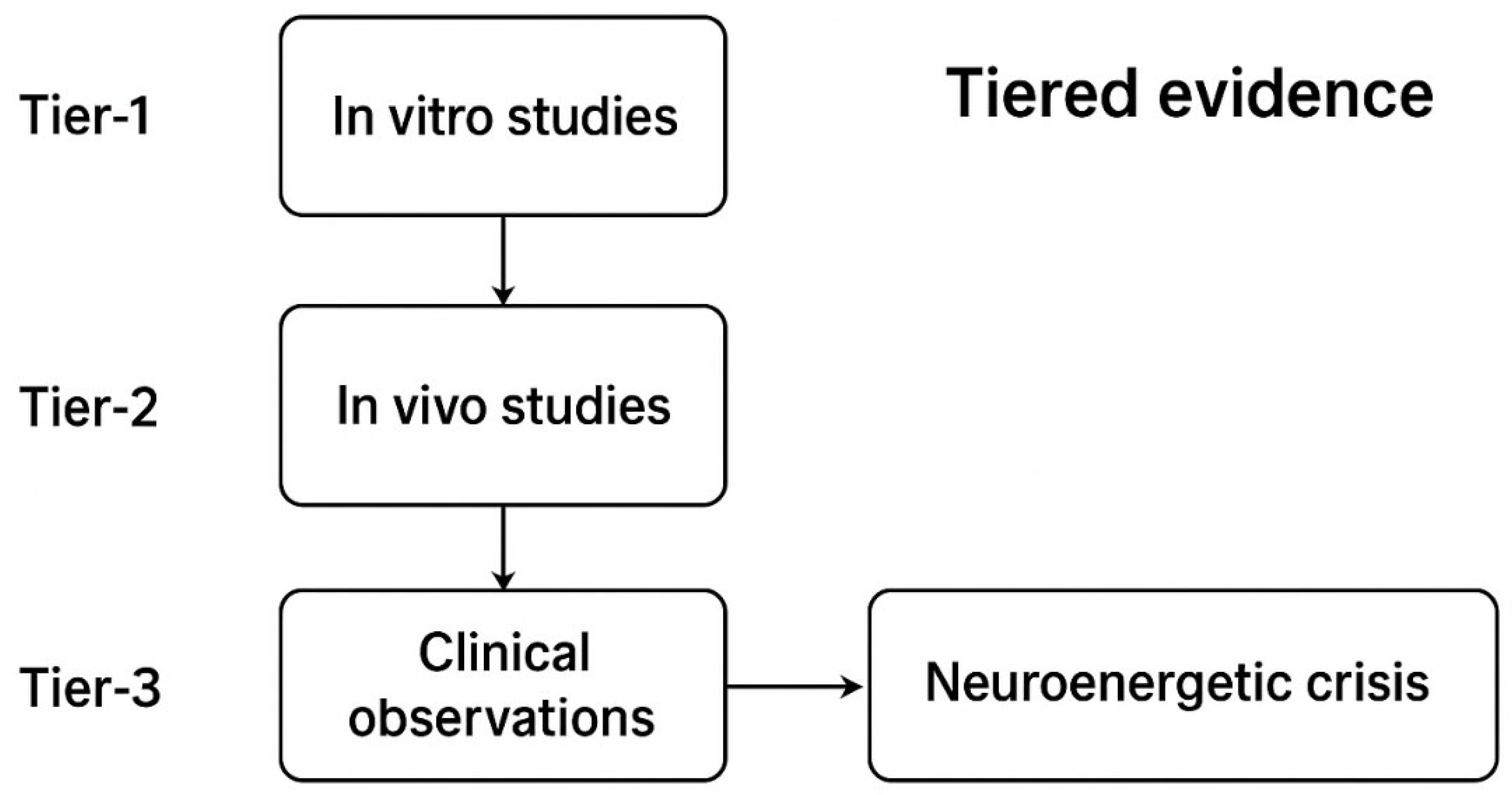

We synthesize the literature into an operational model centered on the pathway: activity → ion-pump load → mitochondrial Ca²⁺ overload → mPTP/ΔΨm collapse → ATP drop → pump failure → positive feedback sustaining bioenergetic failure. We identify mechanistic nodes (MCU, ANT, F-ATP synthase, VDAC–hexokinase), describe glial-neuronal metabolic coupling failures (EAAT dysfunction, lactate shuttling), and link scaffold destabilization to synaptic loss. We stratify evidence into three tiers (human electrophysiology/cohort data; in-vivo animal manipulations; molecular/cellular experiments) and propose prioritized experimental and translational strategies to close the causal loop and develop clinically actionable biomarkers.

Chapter 1 Psychotropic Pharmacology & Excitability Liabilities

Psychotropic agents across multiple pharmacologic classes modulate synaptic transmission and membrane conductances in ways that measurably alter network excitability. This chapter provides a mechanistic bridge linking drug action — with attention to dose, chronicity, and withdrawal — to electrophysiological signatures of network hyperexcitability that elevate neuronal ATP demand. By mapping receptor- and channel-level effects to firing motifs (e.g., sustained bursting, synchronized discharges, progressive threshold lowering) and the consequent energy pathways (ion pumping, Ca²⁺ clearance, mitochondrial respiration), the chapter prepares the reader for Chapter 2, Neuroenergetic Dynamics in Hyperexcitable States: ATP Homeostasis and Experimental Evidence. The chapter’s aims are to (1) summarize pharmacodynamic drivers of hyperexcitability, (2) stratify evidence linking drug exposure to electrophysiological outcomes, (3) describe electrophysiological signatures that elevate ATP demand, and (4) highlight targeted gaps with experimental recommendations.

1.1. Pharmacological Mechanisms and Excitability Profiles of Major Drug Classes

Below we describe major psychotropic classes, their primary targets and downstream electrophysiological consequences, and representative primary literature or systematic reviews supporting each mechanistic linkage.

Benzodiazepines (GABA_A positive allosteric modulators): Mechanism: Positive allosteric modulation of GABA_A receptors produces rapid enhancement of inhibitory tone. With chronic exposure, compensatory neuroadaptations occur (subunit expression changes, postsynaptic receptor desensitization/downregulation, and altered glutamatergic receptor function), so abrupt cessation or rapid tapering can produce rebound hyperexcitability. The phenomenon of benzodiazepine withdrawal–associated seizures and increased network excitability is documented in clinical case series and mechanistic animal and slice studies; in vitro exposure of hippocampal slices to clonazepam produces epileptiform discharges that are amplified following drug withdrawal (Davies, 1987; PMID:3435838; DOI:10.1016/0006-8993(87)91639-8), and clinical case-series analyses corroborate the risk of withdrawal seizures with abrupt cessation or high-dose use (Lader, clinical case analyses/reviews; PMID:21815323).

Mechanistic notes: Upregulation of NMDA receptor function and shifts in NMDA/AMPA balance have been implicated in benzodiazepine-withdrawal hyperexcitability, and NMDA receptor antagonists (e.g., MK-801, ifenprodil) markedly reduce behavioral and electrophysiological withdrawal signs in rodent models (Tsuda et al., 1998; PMID:9593834; DOI:10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00052-3). Additional mechanistic work documents NMDA-related receptor subunit changes during chronic benzodiazepine exposure and withdrawal (see Van Sickle et al., 2004; PMID:15266351).

Selective Serotonin / Serotonin–Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs / SNRIs): Mechanism: Inhibition of SERT/NET elevates extracellular monoamines and engages diverse postsynaptic receptors (including 5-HT_2A/2C), which can indirectly modulate glutamatergic and GABAergic transmission. Clinical and pharmacoepidemiologic studies indicate a modestly elevated seizure risk associated with several modern antidepressants, particularly shortly after treatment initiation and in vulnerable subgroups (e.g., youth, post-TBI). A recent systematic meta-analysis of newer antidepressants quantified this association (Yang et al., 2023; PMID:37996536; DOI:10.1007/s00228-023-03597-y).

Mechanistic notes: In several animal studies, chronic SSRI exposure has been reported to facilitate chemical or electrical kindling and to lower seizure thresholds under specific protocols (Li et al., 2018; DOI:10.1111/epi.14435), although effects are compound-, dose- and model-dependent—hence the need for PK-anchored translational paradigms.

Antipsychotics (D2/5-HT2A antagonists; complex pharmacology): Mechanism: Antipsychotics primarily antagonize D2 and 5-HT2A receptors but also have off-target effects (ion channel interactions, effects on intracellular signalling and redox balance). Several antipsychotics—especially at high doses—have been shown in mechanistic studies to impair mitochondrial function (e.g., inhibition of Complex I activity, alterations in ΔΨm) Recent experimental work further demonstrates that olanzapine and other antipsychotics impair mitophagosome–lysosome fusion and disrupt mitochondrial quality control, leading to structural and functional mitochondrial deficits (Chen et al., 2023; Patergnani et al., 2021), and increase oxidative-stress markers. in neural tissue (Burkhardt et al., 1993; PMID:8098932; Balijepalli et al., 1999; DOI:10.1016/S0028-3908(98)00215-9), supporting a direct mitochondrial route to energetic vulnerability.

Clinical implication: Some antipsychotic compounds have been shown, in preclinical preparations, to perturb mitochondrial function — for example, classical antipsychotics such as haloperidol inhibit mitochondrial complex I activity in rodent brain preparations and induce protein thiol oxidation, and certain second-generation agents (e.g. olanzapine) have been reported to impair mitophagy and mitochondrial morphology in cellular and small-animal models. These preclinical data support the plausibility of a pathway by which pharmacologic exposure could lower the energetic reserve of neural tissue and thereby interact with activity-dependent ATP demand. However, the human in-vivo evidence that routine therapeutic exposures to antipsychotics produce clinically meaningful ATP failure in brain is limited; thus, claims that antipsychotics directly cause energy-failure–mediated hyperexcitability should be presented as a hypothesis supported mainly by preclinical experimental data rather than as established causation.

Psychostimulants (DAT/NET substrates and inhibitors): Mechanism: Psychostimulants increase extracellular monoamines via transporter inhibition or reverse transport, producing cortical and subcortical excitation. Clinically, stimulant exposure can provoke seizures in overdose or in predisposed individuals, but large pharmacoepidemiologic investigations report heterogeneous risk profiles that depend on indication, age, and baseline seizure history; notably, a population-based self-controlled case series found an increased seizure incidence in the first 30 days after initiating methylphenidate (Man et al., 2020; Lancet Child Adolesc Health; PMID:32450123; DOI:10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30159-0), whereas longer-term treatment was not associated with an increased risk.

Polypharmacy and Withdrawal / Kindling Phenomena: Mechanism: Combined use of several psychotropics—or repeated cycles of exposure followed by withdrawal—can produce additive or synergistic effects on excitability (compound receptor adaptations, overlapping withdrawal states). Repeated withdrawal episodes produce a “kindling” or sensitization effect in multiple substance models (alcohol, benzodiazepines), whereby successive withdrawals elicit progressively larger hyperexcitable responses and lower seizure threshold. The kindling model—first described in classic experimental studies and subsequently replicated across substance-withdrawal paradigms—has robust experimental and translational support and provides a mechanistic framework for cumulative excitability following repeated withdrawal or polydrug exposure (classic kindling literature; e.g., Goddard et al., 1969, and subsequent substance-withdrawal studies).

1.2. Evidence Stratification: Linking Drug Exposure to Network Hyperexcitability (Tiered Evidence)

To aid interpretation and experimental design, we stratify evidence connecting psychotropic exposure to electrophysiological hyperexcitability into three tiers. Representative studies and reviews are cited for each tier.

A recent meta-analysis of observational studies found increased seizure risk for SSRIs (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.32–1.66) and SNRIs (OR 1.65, 95% CI 1.24–2.19), with the largest relative risk observed in short-term users (<30 days) (Yang et al., 2023).

Clinical electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) studies report that psychotropic medication class and dosing affect seizure threshold and seizure dynamics during repeated ECT sessions (Cho et al., 2017), supporting a translational link between medication exposure and altered network excitability in humans.

Repeated benzodiazepine withdrawal paradigms in rodents increase seizure susceptibility, with evidence implicating NMDA-dependent mechanisms and attenuation by NMDA antagonists (Tsuda et al., 1998; see also Davies et al., 1988).

The “kindling” phenomenon—progressive worsening of withdrawal severity and increased seizure propensity after repeated withdrawal cycles—has been demonstrated in alcohol and related substance-withdrawal models (Becker & Littleton, Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1996; DOI:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01760.x) and in experimental studies of repeated ethanol withdrawal (e.g., repeated-withdrawal rodent studies; see also withdrawal kindling experimental reports, e.g. DOI:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00731.x).

In vitro hippocampal slice preparations exposed acutely to clonazepam exhibit epileptiform discharges within hours and show an exacerbation of excitability on withdrawal, providing a tightly controlled mechanistic demonstration of receptor- and network-level adaptation (Davies et al., 1987).

Organotypic and acute slice studies report NMDA receptor subunit changes and seizure-locked mitochondrial/Ca²⁺ dynamics during epileptiform activity that plausibly relate to benzodiazepine tolerance/withdrawal; calcium/mitochondrial transients and NMDA-related changes have been described in slice models of epileptiform activity (Kovács et al., 2001) and mitochondrial Ca²⁺/ΔΨm dynamics have been shown to follow epileptiform discharges in slice cultures (Kovács et al., 2005).

Interpretive note: These tiers are complementary: Tier-1 studies provide clinical relevance and population-level risk estimates; Tier-2 offers longitudinal, circuit-level insight; Tier-3 permits high-resolution mechanistic dissection. Translational confidence increases when concordant effects are observed across tiers with PK-anchored dosing and temporally resolved recording of electrophysiology.

1.3. Dose, Regimen, and Neuroadaptive Dependencies

Excitability liabilities are strongly dependent on pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters:

Dose magnitude and exposure duration matter: chronic/high-dose benzodiazepine exposure produces GABA_A receptor adaptive changes and associated network hyperexcitability on withdrawal (e.g., receptor/subunit expression change data in chronic benzodiazepine models — Chen et al., Neuroscience 1999; DOI:10.1016/S0306-4522(99)00118-9; supporting slice/animal physiology: Davies et al., J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1988; PMID:3183966). Acute, low-to-moderate therapeutic dosing is often tolerated without measurable pro-convulsant effects in many patients, but population risk is nonzero and concentrated in vulnerable subgroups (meta-analytic/large-cohort evidence above; Yang et al., 2023; PMID:37996536).

Taper speed and withdrawal dynamics: Rapid discontinuation after chronic, high-dose exposure leads to more severe rebound hyperexcitability and higher seizure risk than gradual tapering; repeated withdrawal cycles further amplify this vulnerability (kindling). repeated withdrawal cycles amplify this vulnerability consistent with “kindling” paradigms (experimental and clinical literature; Becker & Littleton, 1996; repeated-withdrawal experimental reports e.g. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1993 Becker & Hale, 1993).

Polypharmacy interactions: Concurrent agents with complementary excitatory mechanisms or overlapping withdrawal syndromes can create supra-additive excitability. For example, benzodiazepine withdrawal combined with antidepressant-mediated serotonergic modulation can alter seizure thresholds unpredictably; such combinations require careful PK/PD evaluation.

PK/PD anchoring in preclinical designs: Many preclinical reports use supratherapeutic doses or non-clinically relevant regimens. To improve translational validity, studies must specify plasma/CSF exposures and align them with human therapeutic ranges.

1.4. Electrophysiological Signatures and Implications for ATP Demand

Drug-related changes in network activity produce specific electrophysiological signatures that have distinct energetic consequences. The following mapping links observable electrophysiology to ATP demand mechanisms.

Signature → Mechanistic ATP demand: Sustained high-frequency bursting (repeated rapid action-potential trains) markedly increases Na^+/K^+-ATPase workload to restore ionic gradients, and the Na^+/K^+ pump is a dominant ATP consumer during neuronal activity ((Attwell & Laughlin, 2001). Recent in-slice optical biosensor work further shows Na^+/K^+ pump activity tightly controls glycolytic activation, linking firing-driven Na^+ entry to rapid metabolic demand (Meyer et al., eLife 2022; DOI:10.7554/eLife.81645).

Synchronized population discharges and interictal spikes produce large transmembrane ionic currents and intracellular Ca²⁺ elevations that increase ATP demand for ion pumps and Ca²⁺ clearance and impose mitochondrial Ca²⁺ handling load; experimental slice studies show mitochondrial Ca²⁺ transients and ΔΨm changes that closely follow epileptiform discharges (Kovács et al., J Neurosci 2005; DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4000-04.2005), consistent with amplified cytosolic and mitochondrial ATP usage during paroxysmal events.

Progressive lowering of seizure threshold (the kindling phenomenon) produces elevated baseline excitability with intermittent paroxysmal discharges; chronically increased baseline activity yields persistent ATP consumption and increases the probability of acute energetic mismatch during high-demand events (animal and clinical kindling literature; Becker & Littleton, Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1996; DOI:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01760.x).

Measurement endpoints and experimental readouts: These electrophysiological signatures are measurable by scalp/ intracranial EEG, local field potentials (LFP), and in vitro extracellular recordings. When coupled with simultaneous metabolic readouts (real-time ATP sensors, measurement of oxygen/glucose utilization, mitochondrial membrane potential, or NAD(P)H autofluorescence), these endpoints permit direct assessment of the translation from firing pattern to energetic strain—an approach advocated in the following experimental roadmap.

1.5. Intersection with Direct Mitochondrial Toxicity

Two convergent mechanistic routes create heightened vulnerability to energetic failure:

The electrical (demand) route: drug-induced increases in firing raise ion-pump and Ca²⁺-clearance demands and thereby ATP consumption; neurons with preexisting mitochondrial compromise are more likely to experience energetic failure under such load (Attwell & Laughlin, 2001; Meyer et al., eLife 2022; DOI:10.7554/eLife.81645).

Mitochondrial route (supply side): Some psychotropics—most notably several antipsychotics at high concentrations—have been shown to impair mitochondrial electron transport chain activity (Complex I inhibition), reduce mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), and increase reactive oxygen species. These direct mitochondrial insults diminish ATP production capacity.

Convergence: When a drug both increases ATP demand (via network excitation) and impairs mitochondrial ATP production, the combination may increase the risk of energetic mismatch. This two-hit logic (demand + supply impairment) is a useful conceptual model for framing potential risks; direct evidence linking typical clinical exposures to excitotoxic injury in humans remains limited and should be framed by evidence tier.

1.6. Outstanding Research Gaps (Targeted Recommendations)

The literature reveals several specific gaps that must be addressed to move from association to mechanistic causation:

Within-subject co-recording across modalities: Very few studies concurrently record pharmacokinetics (plasma/CSF drug levels), high-resolution electrophysiology (EEG/LFP), and direct metabolic metrics (ATP imaging, O_2/glucose consumption) in the same subjects across exposure and withdrawal phases. Such within-subject, temporally resolved datasets are essential to link dosing → electrophysiology → ATP dynamics; to date, only a few animal studies have combined high-resolution electrophysiology with genetically encoded ATP/pyruvate sensors (i.e., simultaneous EEG/LFP + fiber-photometry), and these studies have not included concurrent pharmacokinetic sampling — a clear Tier-1 design shortfall (Furukawa et al., 2025; doi:10.1111/jnc.70044; PMCID: PMC11923518).

PK-anchored preclinical paradigms: Many preclinical studies use supratherapeutic doses or do not report plasma/CSF exposure, limiting translational relevance. Standardization of PK reporting and explicit use of human-equivalent exposures (e.g., allometric / body-surface conversions and measured plasma/CSF levels) will improve translational inference; practical guidance for dose/exposure conversion between species is available and should be adopted by preclinical studies (Nair & Jacob, 2016 for a pragmatic conversion method).

Chronic exposure & repeated withdrawal models with metabolic readouts: While kindling is well-described behaviorally and electrophysiologically, its chronic metabolic consequences (e.g., cumulative mitochondrial compromise, long-term ATP depletion) are sparsely characterized. Longitudinal repeated-withdrawal (kindling) paradigms combined with mitochondrial/ATP readouts are scarce; targeted longitudinal work combining PK, electrophysiology and metabolic imaging is needed.

Standardized EEG metrics and reporting: Heterogeneous endpoint definitions (what constitutes hyperexcitability) impede synthesis. A consensus minimal EEG reporting set—spike rates, burst frequency/power, spectral shifts, and seizure threshold metrics—would facilitate cross-study comparisons.

Human translational studies in vulnerable subpopulations are limited: population cohorts indicate age- and injury-dependent increases in seizure risk with some psychotropics (for example, increased post-TBI seizure risk associated with antidepressant exposure has been documented in large administrative cohorts), but mechanistic cohort studies that combine medication exposure, electrophysiology and metabolic imaging are lacking (e.g. Ystgaard et al., 2019 for a large cohort analysis of antidepressant exposure after TBI).

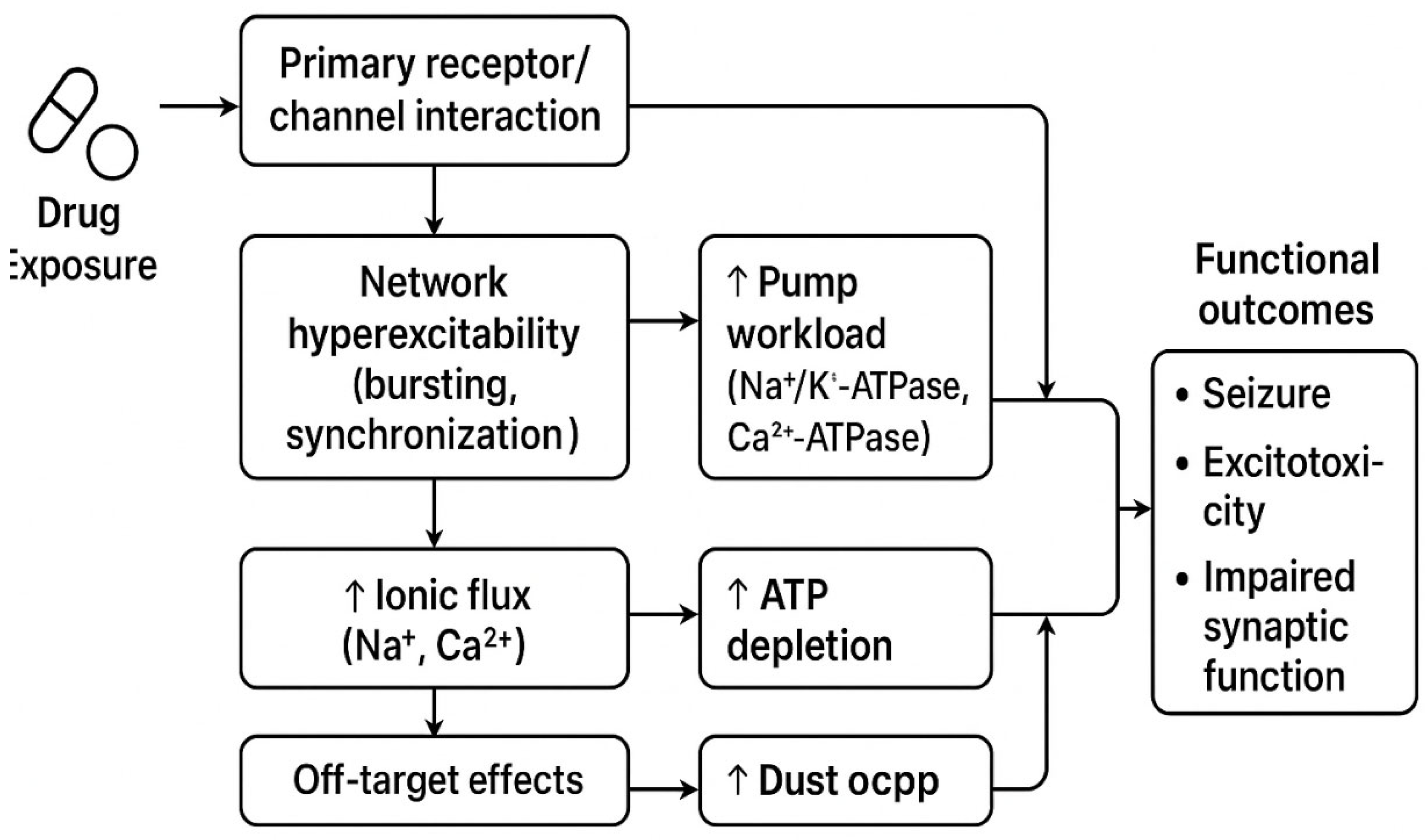

Figure 1.

The proposed mechanistic cascade linking psychotropic drugs to neuroenergetic crisis. (suggested schema) — Drug class | Primary molecular targets | Expected network excitability effect | Representative evidence (key refs) | Dose/regimen notes / PK caveats. Drug (class & dose/regimen) → Primary receptor/channel interaction → Circuit-level firing signature (bursting, spikes, lowered threshold) → Ionic and Ca^2+ pump workload → Mitochondrial Ca^2+ load & ΔΨm strain → ATP depletion risk → Functional outcomes (seizure, excitotoxicity, impaired synaptic function). *Figure created with the assistance of AI (ChatGPT).*.

Figure 1.

The proposed mechanistic cascade linking psychotropic drugs to neuroenergetic crisis. (suggested schema) — Drug class | Primary molecular targets | Expected network excitability effect | Representative evidence (key refs) | Dose/regimen notes / PK caveats. Drug (class & dose/regimen) → Primary receptor/channel interaction → Circuit-level firing signature (bursting, spikes, lowered threshold) → Ionic and Ca^2+ pump workload → Mitochondrial Ca^2+ load & ΔΨm strain → ATP depletion risk → Functional outcomes (seizure, excitotoxicity, impaired synaptic function). *Figure created with the assistance of AI (ChatGPT).*.

1.7. Conclusion and Transition to Neuroenergetic Consequences

As detailed in the preceding sections, multiple psychotropic classes can lower seizure threshold and promote network hyperexcitability through receptor adaptations and withdrawal phenomena (

Section 1.1–1.5). The electrophysiological signatures of this hyperexcitability—such as sustained bursting and synchronized discharges—as exemplified in

Section 1.1–1.5, are intrinsically linked to high ATP consumption. This mechanistic foundation now leads us to a critical question: how do these electrical events translate into measurable neuroenergetic crises? The next chapter will directly examine the experimental evidence for ATP depletion under such hyperexcitable states.

This chapter synthesizes mechanistic pharmacology and cross-tier evidence suggesting that psychotropic drugs can create excitability liabilities via receptor adaptation, mitochondrial perturbation, and repeated withdrawal (kindling). Electrophysiological signatures such as sustained bursting and synchronized discharges map onto major ATP-consuming processes (e.g., Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase, Ca²⁺ clearance); when supply-side impairments coexist, the likelihood of energetic mismatch increases. These claims should be interpreted within the evidence-tier framework described above.

These mechanistic linkages provide a plausible, testable framework that motivates the experimental paradigms in the next chapter; however, the human causal chain remains to be confirmed by within-subject Tier-1 studies. Chapter 2, "Neuroenergetic Dynamics in Hyperexcitable States: ATP Homeostasis and Experimental Evidence", evaluates ATP homeostasis experimentally and quantifies how the firing signatures described here translate into measurable ATP depletion, mitochondrial dysfunction, and downstream synaptic consequences. The combined narrative—pharmacology → electrophysiology → energy imbalance—provides a structured framework for organizing existing data and for designing translational experiments to test causal links; empirical validation across evidence tiers is required before strong causal claims are asserted.

Chapter 2. Neuroenergetic Dynamics in Hyperexcitable States: ATP Homeostasis and Experimental Evidence

Having established the pharmacologically-induced electrophysiological signatures that predict elevated energy demand (Chapter 1,

Section 1.6), we now turn to the empirical evidence linking hyperexcitability to perturbations in ATP homeostasis. This chapter evaluates how the firing motifs described previously—bursting, synchronization, and kindling—directly drive ATP-consuming processes and under what conditions they lead to a measurable energy deficit.

2.1. ATP Metabolism in the CNS Under Hyperexcitable Load

Fast synaptic signaling imposes large ATP demands dominated by restoration of ion gradients through Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase, with additional costs from Ca²⁺ clearance and vesicle recycling. Classic energy-budgeting work established that signaling-related costs constitute a major fraction of cerebral ATP consumption and that higher firing rates greatly increase energy use (Attwell & Laughlin, 2001; J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. doi:10.1097/00004647-200110000-00001; Harris et al., 2012). More recent mechanistic cell- and circuit-level studies show causality in the pump-driven pathway: increased Na⁺ influx during activity activates Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase and stimulates glycolysis (Meyer et al., 2022).

Figure 2.

A tiered evidence framework for studies linking psychotropic drugs to neuroenergetic crisis. (Place “Fig. 2” schematic here: activity → Na⁺ influx → Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase work → glycolytic & mitochondrial upregulation → ATP turnover under hyperexcitability.) *Figure created with the assistance of AI (ChatGPT).*.

Figure 2.

A tiered evidence framework for studies linking psychotropic drugs to neuroenergetic crisis. (Place “Fig. 2” schematic here: activity → Na⁺ influx → Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase work → glycolytic & mitochondrial upregulation → ATP turnover under hyperexcitability.) *Figure created with the assistance of AI (ChatGPT).*.

2.2. Evidence Stratification: From Direct Co-Measurements to Correlated Readouts

A recent in vivo mouse study using cell-type specific FRET sensors (Thy1::ATeam for neuronal ATP; Mlc1-tTA::tetO-PYRS for astrocytic pyruvate) combined hippocampal fiber photometry with EEG during electrically-evoked seizure paradigms and reported rapid neuronal ATP decreases concurrent with astrocytic pyruvate increases (Furukawa et al., 2025).

Complementary in vivo work using neuronal ATeam sensors has demonstrated cortex-wide fluctuations of intracellular ATP across sleep–wake states (Natsubori et al., 2020), validating the feasibility and physiological sensitivity of in vivo ATP imaging and supporting its use as a translational tool for linking activity with energy dynamics.

In acute hippocampal slices, elevating Na⁺ influx and Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase activity drives glycolysis; glycolytic NADH signals track stimulus-evoked ion pumping, implicating ATP turnover coupling to bursts and sustained firing (Díaz-García et al., 2021; Meyer et al., 2022). Organotypic and acute slice studies using genetically encoded ATP or ATP:ADP sensors (ATeam, PercevalHR) robustly report cellular ATP status under metabolic and excitatory challenges, supporting experimental designs where seizure-like activity (e.g., 0 Mg²⁺, high K⁺, kainate) can be combined with real-time ATP imaging (Imamura et al., 2009; Tantama et al., 2013; Lerchundi et al., 2020; Marvin et al., 2024).

Human ^31P-MRS(I) quantifies high-energy phosphates (ATP, PCr, Pi) and intracellular pH in vivo; clinical epilepsy studies report regional alterations of energy metabolites interictally and can capture transient activation-related changes, although sensitivity at clinical field strengths is a limitation (Hetherington et al., 2002; Frontiers Aging Neurosci. review, 2023).

2.3. Pharmacology–Energy Overlap: From Drug-Induced Hyperexcitability to ATP Demand

The prior chapter detailed how certain psychotropics can lower seizure threshold or enhance network excitability (e.g., via GABA_A modulation/withdrawal, 5-HT receptor-mediated glutamatergic facilitation, Na⁺ channel effects, dopaminergic stimulants). Here, we emphasize the energetic consequence: any sustained hyperexcitability imposes increased Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase work and Ca²⁺ handling, pushing ATP turnover upward and risking acute ATP shortfall when production cannot keep pace (Johannessen Landmark et al., 2016).

2.4. Mechanistic Bridges from Hyperexcitability to ATP Decline

Bursts and seizure-like discharges elevate Na⁺ influx and subsequent Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase work; in slices, glycolytic signals are dominated by Na⁺ load rather than Ca²⁺, highlighting the primacy of ion pumping in energetic costs (Meyer et al., 2022; Díaz-García et al., 2021). Human and rodent seizure-model imaging reveals massive synchronous firing and characteristic calcium motifs that reinforce the high bioenergetic-demand state (Frontiers Neurosci., kainate calcium imaging studies, 2016; Furukawa et al., 2025).

Ionic–Membrane Loop: ATP↓→Pump Inefficiency→Membrane Instability

When ATP production lags, Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase cannot fully restore gradients, predisposing neurons to membrane instability, depolarization block, or paradoxical hyperexcitability in connected circuits as K⁺ handling shifts to astrocytes. Foundational experimental work implicates the Na⁺/K⁺ pump as central to neuronal and astroglial ion homeostasis, and perturbing its capacity produces system-level excitability consequences (Meyer et al., 2022; Furukawa et al., 2025).

Beyond the activity-driven increase in ATP demand

('the electrical route'), certain psychotropic agents can also impair ATP production directly—a 'supply-side' vulnerability previously highlighted in the context of antipsychotics

(Chapter 1, Section 1.3 and 7). This mitochondrial route, while drug-specific, creates a convergent risk for energetic failure when combined with elevated demand. electrical load, several neuroactive compounds modulate mitochondrial function (e.g., respiratory chain complex I/IV, ΔΨm, ROS), establishing a parallel route to ATP compromise that can summate with pump-driven demand. Although this chapter centers on activity-driven ATP dynamics, this mitochondrial route explains why some drugs demonstrate ATP vulnerability even outside frank seizures (see next chapter on mitochondria for details).

Astrocytes buffer K⁺, clear glutamate, and shuttle metabolites (e.g., lactate). In vivo seizure models with cell-type targeted metabolic sensors report rapid increases in astrocytic pyruvate concurrent with neuronal cytosolic ATP decreases, implying a cell-type divergence and a neuron–glia supply–demand mismatch under hyperexcitability (Furukawa et al., 2025; Lerchundi et al., 2020).

To quantitatively capture the dynamic interplay between neuronal activity, mitochondrial function, and ATP homeostasis, we propose a minimal two-compartment ODE model that integrates both the electrical and mitochondrial routes of ATP demand and supply. This model serves as a testable framework for predicting ATP depletion risk under pharmacologically induced hyperexcitability.

To quantitatively bridge the chain “neuronal discharge / drug load → ATP consumption → mitochondrial stress”, we introduce a simple two-compartment ODE framework describing cytosolic and mitochondrial ATP pools and their exchanges. The equations below adopt the notation used in the Supplement and are intended to follow the Mechanistic Bridges subsection in Chapter 2, providing a compact mechanistic model that feeds into Chapter 3’s discussion of mitochondrial failure.

Core modeling assumptions (explicit)

Two well-mixed compartments: cytosolic ATP pool (A_c) and mitochondrial ATP reserve (A_m). Each compartment is spatially homogeneous (no spatial gradients inside a compartment).

Deterministic ordinary differential equations (continuous time). Stochastic fluctuations are not modeled explicitly here but can be added as noise terms if required.

Linear exchange between compartments (k_{m->c}A_m) and linear first-order losses (k_{loss}A_c). Nonlinearities (e.g., saturable transport) may be added in extended models but are omitted for this minimal framework.

Activity-driven consumption is proportional to an empirically derived firing-rate time series FR(t); drug exposure enters as an additive (or multiplicative, if calibrated) ATP load D(t). FR(t) must be preprocessed before use (see §6 Data preprocessing).

Time-invariance of baseline parameters during each analyzed window (parameters may be re-estimated across windows to capture slow adaptations).

Definitions and experimental mapping (suggested):

: cytosolic (available) ATP pool (measurable via cytosolic ATP sensors or ATP:ADP proxies).

: mitochondrial ATP reserve / mitochondrial production capacity indicator.

: glycolytic ATP production rate (estimated from lactate flux or glycolytic assays).

: mitochondrial ATP production (inferred from OCR/ΔΨm or respirometry).

: coupling rate from mitochondrion to cytosol.

: activity-dependent ATP consumption proportional to firing rate .

: additional ATP load related to drug/"ring" exposure with coupling .

: baseline cytosolic ATP loss/consumption.

: loss of mitochondrial production capacity due to dysfunction (mtDNA/ROS/mPTP effects).

Interpretation / bridge: Placing this model here turns Section 2's qualitative chain into a quantitative mapping from measurable and to , , creating a direct pipeline to the mitochondria-failure feedback discussed in Chapter 3.

2.5. What We Can Already Claim (Without Overreach)

(i) Direct in-vivo co-measurements now show epileptic hyperactivity is accompanied by neuronal ATP decreases (Tier-1) Tier-1 in-vivo co-measurements using genetically encoded ATP sensors plus EEG/fiber photometry directly demonstrate neuronal ATP decreases concurrent with epileptic hyperactivity in mouse models (Furukawa et al., 2025; Straub et al., 2025). (Furukawa et al., 2025). (ii) Activity manipulations in slices demonstrate Na⁺ load → pump work → glycolysis coupling that scales metabolic demand with excitability (Tier-2) (Díaz-García et al., 2021; Meyer et al., 2022). (iii) Human ^31P-MRS relates epileptic network dysfunction to regional high-energy phosphate alterations (Tier-3) (Hetherington et al., 2002; Frontiers Aging Neurosci., 2023). Together these support the plausible chain “drug → hyperexcitability → ATP strain,” while flagging the remaining gap: studies that simultaneously quantify drug exposure, network activity, and ATP dynamics in a single in-vivo preparation are still scarce.

2.6. Measurement Paradigms for Testing the Drug→Excitability→ATP Decline Chain

In vivo LFP/EEG combined with neuron-targeted ATP sensors (e.g., ATeam variants; next-gen iATPSnFR2) permits time-locked tracking of ATP during drug-induced hyperexcitability, extending seizure paradigms to psychotropic exposures (Imamura et al., 2009; Marvin et al., 2024; Furukawa et al., 2025).

Use low-Mg²⁺/high-K⁺/chemoconvulsants or opto/chemo-genetics to ramp activity while imaging ATP/ATP:ADP; quantify dose–time–region dependencies. Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase-centered frameworks predict ATP transients scale with ion load (Meyer et al., 2022; Díaz-García et al., 2021; Lerchundi et al., 2020).

^31P-MRS(I) at higher field strengths (with improved coils) offers translational windows to monitor HEPs pre/post drug challenge in patients with seizure risk or during withdrawal, complementing laboratory models (Hetherington et al., 2002; Frontiers Aging Neurosci., 2023).

2.7. Caveats and Species-Level Considerations

While mouse data provide causal co-measurements (EEG/photometry + ATP), human data are correlative (^31P-MRS). Slice paradigms allow control but may not capture large-scale network topology differences between species. Thus, translating drug→hyperexcitability→ATP in mice to humans requires careful dose scaling, network context, and field-strength-appropriate human metabolic readouts (Macleod et al., 2007).

2.8. Summary: A Convergent, Testable Chain

Multiple experimental streams converge on a testable chain:

hyperexcitability → increased ion-pump work & Ca²⁺ handling → accelerated ATP turnover → measurable neuronal ATP decreases when supply lags. Recent methodological advances (genetically encoded ATP sensors, fiber photometry/2-photon imaging, in vivo EEG/LFP, ^31P-MRS) now make it feasible to begin addressing the evidence gap by co-measuring drug levels, neural activity and metabolic state in the same preparation; translation to human studies requires careful ethical and technical design.

These pharmacologically induced shifts in network excitability are expected to increase neuronal energy demand and may produce a measurable energy burden under conditions where ATP supply is constrained; direct demonstration in humans requires PK-anchored, within-subject metabolic measures. The next chapter quantifies this burden, assembling direct in vivo co-measurements and mechanistic experiments to evaluate whether hyperexcitability acutely depresses neuronal ATP and how this can be captured in translational paradigms.

Chapter 3. ATP Deficit → Mitochondrial Failure → Neuroglial Dysfunction: Mechanistic Cascade

The previous chapter established that network hyperexcitability elevates neuronal energy demand and can acutely depress intracellular ATP.This chapter examines the downstream cellular consequences of such ATP shortfalls, focusing on how ATP depletion triggers mitochondrial failure and how glial cells—particularly astrocytes and microglia—respond and amplify neuronal injury (Kovács et al., J. Cell Sci. 2012; DOI: 10.1242/jcs.099176; Kovács & Abramov, reviews on seizure-related mitochondrial dysfunction; DOI: 10.1242/jcs.099176).

The experimental evidence summarized in Chapter 2 is consistent with the hypothesis that network hyperexcitability can acutely depress intracellular ATP levels; however, much of this evidence derives from Tier-2 (in vivo animal) and Tier-3 (ex vivo) preparations, and within-subject human confirmation is limited. This chapter examines the downstream consequences of this energy deficit, focusing on how ATP depletion triggers a catastrophic cascade of mitochondrial failure and disrupts the essential homeostatic functions of glial cells.

Core proposition (experimental context): in several experimental systems an acute fall in ATP together with Ca²⁺ overload and ROS production can facilitate mPTP opening and ΔΨm collapse—events associated with impaired ATP synthesis. Extrapolation of this cascade to human in vivo states requires targeted within-subject translational work. Secondary ROS production damages mtDNA and ETC complexes, leading to a chronic reduction in ATP-generating capacity. Concomitantly, defects in mitochondrial dynamics (fission/fusion), transport and mitophagy prevent effective clearance and replacement of damaged organelles, creating a positive feedback loop that exacerbates energy failure and impairs glial homeostatic functions (e.g., EAAT-mediated glutamate uptake, K⁺ buffering, trophic support).

3.1. Astrocytes — ATP Dependence and Immediate Consequences of ATP Loss

EAAT and ion-coupled glutamate uptake. Astrocytic glutamate uptake is mediated primarily by EAAT1/EAAT2 (GLAST/GLT-1) and operates as a Na⁺-coupled transporter; its activity depends on transmembrane ion gradients maintained by Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase and on cellular ATP supply. When astrocytic ATP falls, EAAT function is compromised, resulting in prolonged extracellular glutamate transients that exacerbate neuronal NMDA/AMPA receptor activation and Ca²⁺ influx—thereby increasing neuronal metabolic burden and excitotoxic risk. This Na⁺-dependent mechanism and its ATP sensitivity are well documented in slice and in vivo studies (Díaz-García et al., eLife 2021; DOI: 10.7554/eLife.64821; Meyer et al., eLife 2022 on Na⁺/K⁺-pump → glycolysis coupling; DOI: 10.7554/eLife.81645).

Metabolic support: astrocyte glycolysis and lactate shuttle. Astrocytes provide metabolic substrates (notably lactate) to neurons and can increase glycolytic flux under high neuronal demand. However, astrocytic glycolysis itself requires ATP for hexokinase activity and for fueling glutamate-to-α-KG conversions; severe ATP depletion in astrocytes impairs these supportive pathways, compromising neuronal fuel supply precisely when demand is greatest (Pellerin & Magistretti, 1994; Lerchundi et al., Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020 for astrocyte vs neuron metabolic responses; DOI: 10.3389/fncel.2020.00080).

3.2. Acute Bioenergetic Stress: MCU, mPTP, ΔΨm Collapse and Immediate ATP Failure

Ion pumps → mitochondrial load. Intense neuronal firing raises intracellular Na⁺ and Ca²⁺; ATP consumption by Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase and Ca²⁺-ATPases escalates. Mitochondria buffer cytosolic Ca²⁺ via the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU); transient uptake can stimulate dehydrogenases and OXPHOS, but sustained overload drives matrix Ca²⁺ to pathological levels (Raffaello et al., review on MCU; Annual Review/FF literature; (Raffaello et al., 2016; De Stefani et al., 2011; Baughman et al., 2011)).

mPTP opening and ΔΨm collapse. Under combined Ca²⁺ overload and oxidative stress, the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opens; this causes collapse of ΔΨm, matrix swelling, and cessation (or reversal) of ATP synthase activity, producing abrupt ATP depletion. mPTP biology and its role in bioenergetic collapse are well established in experimental models (Bernardi et al., 2015; Giorgio et al., PNAS 2013 on F-ATPase/ANT contributions to mPTP; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1217823110).

Experimental evidence. Slice and in vivo seizure models record rapid ΔΨm loss and ATP fall within minutes of strong epileptiform activity; pharmacological MCU inhibition or mPTP modulators can mitigate these declines in experimental settings. These data link activity-driven ionic stress to rapid mitochondrial and ATP failure (Kovács et al., 2012; Abramov et al., related studies summarized in same work).

3.3. ROS, mtDNA Damage and ETC Dysfunction — The Redox Feedback Loop

ROS as amplifier. When electron flow through the ETC is perturbed (by Ca²⁺ overload, ΔΨm dissipation, or substrate limitation), electron leakage at Complexes I and III increases, producing superoxide and other ROS. ROS oxidatively damage lipids, proteins and mtDNA; damage to mtDNA—lacking robust repair—reduces expression of mtDNA-encoded ETC subunits, progressively impairing respiration. The process creates a feed-forward deterioration of ATP production (Lin & Beal, Nature 2006 on mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress; DOI: 10.1038/nature05292).

Evidence for mtDNA damage in stress. Oxidative mtDNA lesions (e.g., 8-oxoG) accumulate in models of excitotoxicity, ischemia-reperfusion and chronic metabolic stress; these lesions correlate with decreased Complex I/IV activities and sustained ATP deficits (review and experimental compilations; Lin & Beal, Nature 2006; DOI: 10.1038/nature05292; selected experimental reports as summarized in Kovács et al., J. Cell Sci. 2012; DOI: 10.1242/jcs.099176).

3.4. Mitochondrial Dynamics, Transport and Quality Control Failure

Fission / fusion balance. The balance of mitochondrial fission (DRP1) and fusion (OPA1, MFN1/2) determines organelle morphology and function. Under oxidative/energetic stress, DRP1 activation often drives excessive fission, producing fragmented, less efficient mitochondria that are prone to removal but—if mitophagy is insufficient—accumulate as dysfunctional organelles. Dysfunctional mitochondrial accumulation impairs local ATP supply, particularly at synapses and axon terminals (Youle & van der Bliek, 2012); Tilokani et al., 2018).

Axonal transport & focal energy failure. Motor/adaptor machinery transports mitochondria to sites of demand. Damage to transport leads to distal synaptic energy deficits even if somatic ATP seems less affected—thus impairing synaptic transmission and plasticity (reviewed in Youle & van der Bliek, Science 2012; DOI: 10.1126/science.1219855; and transport/mitochondria studies summarized in Mol. Biol. Cell and Frontiers reviews).

Mitophagy & UPRmt. Efficient mitophagy (PINK1/Parkin pathway and receptor-mediated routes) and mitochondrial UPR are essential to clear/repair damage. Under severe or repeated ATP/ROS insults, mitophagy can be overwhelmed or dysregulated, permitting accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria and long-term respiratory decline (Youle & van der Bliek, Science 2012; DOI: 10.1126/science.1219855; reviews on PINK1/Parkin pathway summarized in Mol. Cell Biol literature).

3.5. Channels & Effectors: MCU, ANT, F-ATPase, VDAC-Hexokinase — Mechanistic Nodes

MCU. MCU mediates mitochondrial Ca²⁺ uptake; its inhibition can protect against Ca²⁺-induced ΔΨm collapse in models, whereas MCU-mediated overload accelerates dysfunction (Raffaello et al., review on MCU complex; Annual Review/Frontiers summaries; (Raffaello et al., 2016; De Stefani et al., 2011; Baughman et al., 2011)).

mPTP molecular contributors (ANT, F-ATP synthase). The molecular identity of the mPTP remains debated (ANT, F-ATP synthase components implicated); nevertheless, ADP/ATP ratio and ANT conformation influence pore sensitivity—linking cellular energetics directly to pore regulation (Giorgio et al., 2013).

VDAC-Hexokinase & inflammation. Hexokinase (HK) binding to VDAC couples glycolysis to mitochondrial function; HK dissociation during stress can promote VDAC oligomerization, NLRP3 inflammasome activation and Ca²⁺ release from ER—mechanisms linking metabolic uncoupling to inflammation (Pastorino & Hoek, 2008; Baik et al., 2023).

3.6. Positive Feedback: From Acute ATP Loss to Chronic Energy Failure

Integrated loop. The elements above create a feed-forward loop: high activity → ion-pump ATP consumption → mitochondrial Ca²⁺ load and ROS → mPTP/ΔΨm collapse → immediate ATP loss → impaired pump function and ion homeostasis → further abnormal activity/ionic stress → additional mitochondrial damage (mtDNA/ETC) → persistent ATP deficit. This integrative model explains how transient high-energy events can be converted into sustained bioenergetic and structural pathology (Kovács et al., J. Cell Sci. 2012; DOI: 10.1242/jcs.099176; Bernardi et al., 2015).

3.7. Neuroglial Consequences — Astrocytes, Microglia, Oligodendrocytes, Synaptic Scaffolds

Inhibition of excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs) and the consequent failure of glutamate clearance contribute to the spread of excitotoxicity. In addition, astrocytic functions in lactate supply and K⁺ buffering are compromised under metabolic stress (Danbolt, 2001; Pellerin & Magistretti, 1994).

ATP serves not only as the cellular energy currency but also as a signaling molecule. Severe ATP depletion or excessive extracellular release of ATP can activate microglia via P2X/P2Y receptors. Energy impairment drives a metabolic shift in microglia from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis, accompanied by the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α). This creates a pro-inflammatory milieu that exacerbates neuronal damage and suppresses oligodendrocyte precursor differentiation (recent reviews and experimental studies summarized in Frontiers/Cell reports; e.g., Ransohoff & Brown reviews and recent Frontiers in Pharmacology 2024 on mitochondria–neuroinflammation; DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1469053).

Oligodendrocytes and their precursors are highly sensitive to metabolic supply. ATP deficiency disrupts myelin synthesis and ionic homeostasis, potentially leading to conduction block and secondary axonal injury. Animal studies support the pathway linking energy deficits to white matter and myelin pathology.

ATP is essential for kinase/phosphorylation pathways (e.g., CaMKII, PKA) that maintain the assembly of postsynaptic scaffolding proteins such as PSD-95 and Shank. Energy insufficiency leads to dephosphorylation or disassembly of these scaffolds, dendritic spine shrinkage, and synaptic dysfunction. Prolonged scaffold destabilization has been linked to both cognitive and affective impairments. (Source: PMC)

3.8. (Optional Brief) Drug-Toxicity Convergence

The preceding sections delineate a unified pathway from hyperexcitability to bioenergetic failure. Converging with this model, diverse psychoactive agents show in vitro/animal signals consistent with mitochondrial stress (ΔΨm change, ROS increase, decreased Complex activity, mtDNA effects); these molecular end-points align with the cascade above, though direct in vivo chain-closing evidence for clinical dosing requires separate verification. (reviews on drug-induced mitochondrial stress and seizures summarized in Kovács et al., J. Cell Sci. 2012; DOI: 10.1242/jcs.099176; and translational caveats in ALTEX 2021; DOI: 10.14573/altex.2007082).

In sum, experimental systems, ATP depletion can act as both an amplifier and potential precipitant of mitochondrial dysfunction: via mechanisms such as mPTP/ΔΨm collapse, ROS-driven mtDNA/ETC damage and impaired mitochondrial quality control. Whether transient energetic crises convert into sustained glial dysfunction and system-level neural impairment in humans remains to be established (evidence mainly Tier-2/3). The astrocyte–neuron metabolic partnership is particularly vulnerable: when astrocytic ATP falls, glutamate clearance and metabolic support fail at precisely the time neurons need them most, thereby turning a metabolic shortage into excitotoxic and inflammatory damage (Kovács et al., J. Cell Sci. 2012; DOI: 10.1242/jcs.099176; Lin & Beal, Nature 2006; DOI: 10.1038/nature05292).

Chapter 4. Species Differences & Translational Considerations (Neutral, Non-Clinical)

Introduction — the translational challenge (placement & intent)

Mechanistic evidence linking drug-associated changes in excitability to neuronal ATP stress is persuasive at the level of cells and small circuits. Extrapolation from rodent preparations to the human brain, however, requires species-aware calibration. Differences in mesoscale network topology, single-cell biophysics, and glial metabolic programs can alter (a) how focal perturbations propagate, (b) the per-neuron energetic cost of a given discharge pattern, and (c) which measurement modalities are most likely to detect focal ATP deficits in humans. These factors shape the interpretation of preclinical data and the design of future translational studies.

4.1. Network Topology: Reciprocity, Cycles, and Spread of Excitation

Comparative connectomics indicate that mouse cortical networks are denser and contain more bidirectional (reciprocal) motifs than human cortical connectomes. Higher reciprocity increases the number of closed loops and the propensity of local excitation to reverberate and recruit large populations, favoring broad, synchronous activation during pathological events. In contrast, human cortex—especially association areas—exhibits relatively more directed/acyclic mesoscale wiring, which can constrain runaway synchrony and favor more spatially localized “hotspots” when pathology occurs. Consequently, an identical focal perturbation can yield a larger spatial footprint of activity (and thus broader ATP demand) in mouse cortex than in human cortex.

Translational note: Rodent models are valuable for probing mechanisms and causal perturbations, yet they may overestimate the spatial extent and duration of ATP dips relative to human cortex for the same local drive.

4.2. Cellular Electrophysiology: Integrated Ionic Work per Spike

Direct patch-clamp and morphological studies show consistent species differences in pyramidal neuron biophysics: human cortical/hippocampal principal cells often display larger somatodendritic capacitance, lower input resistance, and higher current thresholds for action potential initiation than rodent neurons. This implies (i) more charge is required to reach threshold (“energetic entrance fee”), and (ii) once firing occurs, the ionic load per spike—and the ATP required to restore gradients via Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase and Ca²⁺ pumps—can be larger on a per-cell basis. Put differently, rodent circuits may be easier to recruit across space, whereas human neurons—once recruited—may impose a higher ATP cost per active neuron.

4.3. Glial and Cell-Type Metabolic Differences

Single-cell and single-nucleus transcriptomic comparisons reveal divergence between human and mouse astrocytes/microglia in pathways linked to glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, antioxidant defenses, and inflammatory signaling. Because glia buffer extracellular K⁺, recycle glutamate, and support neuronal energetics (including lactate shuttling), species differences in glial programs can influence tissue resilience to transient ATP deficits and recovery kinetics after bursts. Inferences about human vulnerability based on rodent data benefit from taking these glial differences into account.

4.4. How Topology + Cell Biophysics Shape ATP Signatures (Measurement Consequences)

Taken together, higher reciprocity in rodents can promote broader recruitment and larger spatially distributed ATP dips (detectable by regional measures), whereas human circuits may exhibit more focal recruitment but higher per-cell ATP cost (harder to detect using coarse ^31P-MRS or scalp EEG). Thus a “broad-but-shallow” energy-failure signature in mouse may correspond to a “focal-but-deep” signature in humans. This measurement mismatch helps explain instances where rodent-derived predictions of whole-region ATP collapse are not evident in clinical-scale imaging despite genuine focal metabolic crises.

4.5. Measurement Bias & Implications for Interpretation

Two complementary biases can arise:

Overestimate bias (rodent → human): Rodent reciprocity can amplify spread and make ATP depletion appear larger in volume/duration than a human-equivalent event.

Undersampling bias (human → rodent inference): Human focal hotspots may be missed by ^31P-MRS (voxel SNR) or by scalp EEG (limited spatial sensitivity), producing false negatives if only coarse readouts are considered.

To mitigate both biases in interpretation, analyses can benefit from species-appropriate calibration and, where available, human-centric anchors (e.g., high-field ^31P-MRS datasets, or intracranial recordings acquired for clinical reasons). These anchors are mentioned here as observational comparators rather than as procedural recommendations.

4.6. Measurement Considerations: Species-Aware Strategies (Descriptive, Non-Prescriptive)

A commonly used dual-track approach in the literature involves:

(A) Mechanistic animal studies that combine EEG/LFP/local-field recordings with genetically encoded ATP or ATP:ADP biosensors (e.g., PercevalHR, ATeam, iATPSnFR family) to examine within-subject temporal coupling between hyperexcitability and metabolic stress; and

(B) Human-relevant anchoring using ^31P-MRS (PCr/ATP, Pi/ATP, pH) and, in some contexts, FDG-PET or intracranial EEG acquired for medical reasons. Calibration of sensors (preferably ratiometric), documentation of probe expression/distribution, and measurement of drug PK (plasma/CSF) can facilitate PK/PD alignment across species and strengthen claims of translational equivalence. (See, for example, Meyer & Brown, 2016, Magnetic Resonance in Medicine.)

Note: These descriptions summarize measurement practices reported in prior work and are provided for context rather than as recommendations for clinical use.

4.7. Species-Aware Variables That Influence Interpretability

Several variables can influence cross-species interpretability without implying procedural guidance:

Parameter scaling: Stimulus amplitude, optogenetic/chemogenetic drive, and current injections can be related to measured AP threshold, input resistance, and capacitance in the species/tissue studied (reporting numeric values aids comparability).

Temporal resolution: Rodent ATP dynamics are often resolvable at sub-second to second timescales (e.g., optical sensors, fiber photometry), whereas human studies may rely on the shortest feasible ^31P-MRS protocols or local invasive sampling when such data already exist for medical reasons.

Spatial sampling: Combining local (LFP + optical ATP) with mesoscale (MRS/PET) readouts can help map focal vs regional deficits.

Cell-type interrogation: Inclusion of astrocytic probes or markers (e.g., astrocyte-targeted ATP sensors or glycolytic enzyme readouts) can assist interpretation of PET/MRS signals.

These points are intended to clarify sources of variance and reporting practices that improve cross-study comparison.

4.8. Short Conclusion & Transition

Human and rodent brains differ systematically in network topology, single-cell excitability, and glial metabolic programs; these differences can shift the energy-demand profile from a “broad-but-shallow” pattern in rodents to a “focal-but-deep” pattern in humans, with consequences for measurement and translation. The following chapter examines how electrophysiological signatures considered across this manuscript relate to quantifiable ATP dynamics in vivo and ex vivo, using species-aware considerations as interpretive context rather than as procedural guidance.

Chapter 5. Translational Research Agenda and Measurement Priorities (non-clinical)

Scope note: This chapter specifies testable hypotheses, measurement priorities, and study designs for future research; it provides no clinical guidance or prescribing advice, and all operational details are deferred to the Supplement as IRB/DSMB-controlled templates.

To map experimental / imaging / clinical markers to an intuitive safety/risk scale, we introduce the steady-state / safety index

, defined over a time window

as the ratio of reserve + cumulative supply to cumulative consumption (formula per the manuscript notation):

where

denotes baseline reserve (e.g., resting

or tissue energy buffer),

is time-varying additional supply (e.g., compensatory glycolysis, exogenous metabolic support), and

is time-varying additional consumption (activity/drug/withdrawal-related load).

link to risk tiers for monitoring/triage:

indicates abundant reserve (low risk);

indicates marginal reserve (intermediate risk);

indicates insufficient reserve (high risk).

Thresholds must be calibrated on cohort data and/or imaging measures: the manuscript’s Supplement should document the calibration procedure and example cut-points.

5.1. Trial Candidates & Evidence Gaps (Research-Only)

Scope. This section summarizes mechanistic rationales, representative evidence, and open questions for candidate metabolic or neuroprotective strategies as hypotheses for future studies. The content is descriptive and does not constitute clinical guidance or recommendations.

5.1.1. Ketogenic Diets and Ketone Bodies

Evidence (mechanistic / preclinical / limited clinical):

Ketogenic interventions and exogenous ketones reduce network hyperexcitability in multiple preclinical paradigms and show anticonvulsant effects in refractory epilepsy contexts.

Ketone utilization can support mitochondrial ATP production and redox balance under high-demand states in model systems.

Evidence gaps / uncertainties:

Translational relevance to drug-associated ATP stress in human brain tissue is not established.

Optimal parameters (duration, intensity, biomarker anchors) for detecting energetic effects remain to be defined in controlled studies.

5.1.2. Creatine Supplementation

Efficacy for mitigating drug-related ATP depletion has not been demonstrated.

Dose, exposure window, and phenotype selection criteria for robust effects are undetermined.

5.1.3. Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) and Mitochondrial Cofactors

5.1.4. Antioxidants / N-Acetylcysteine (NAC)

NAC provides cysteine for glutathione synthesis and has been studied as an adjunct in several psychiatric indications with heterogeneous symptom outcomes.

Antioxidant mechanisms offer a rationale for probing interactions with oxidative/energetic stress.

Direct demonstration that NAC prevents drug-associated ATP decline in humans is lacking.

Biomarker frameworks to quantify redox–energetic coupling alongside electrophysiology remain to be standardized.

5.2. Hypothetical Templates for Future Trials (Illustrative; Non-Clinical)

Scope & disclaimer. The following study templates are illustrative hypotheses intended to guide future research planning. They are not medical advice, do not prescribe management, and would be subject to institutional review board (IRB) and data & safety monitoring board (DSMB) oversight prior to any implementation.

Design (one possible approach). A randomized, placebo-controlled adjunct study in an enriched research cohort characterized by phenotypes in which hyperexcitability–energetics coupling is expected to be measurable (e.g., prior seizure history, markers of mitochondrial vulnerability, or documented exposure to specific psychotropic agents).

Primary readout. Change in regional energetic markers (e.g., PCr/ATP via ^31P-MRS) or event-locked ATP surrogates quantified with pre-specified analysis pipelines.

Secondary readouts. Concurrent EEG features (e.g., spectral or event-related metrics), cognitive task performance, and standardized safety observations.

Notes. Biomarker-based enrichment and adaptive features (e.g., sample-size re-estimation, response-adaptive randomization) are optional tools to improve statistical efficiency and target engagement inference.

Design (one possible approach). A within-subject, pre/post mechanistic study in a small cohort, using a monitored pharmacological challenge or withdrawal window permitted under IRB-approved conditions. Record high-resolution EEG synchronously with ^31P-MRS (or serial sampling paradigms) and pair with peripheral metabolic biomarkers to evaluate temporally linked changes between excitability signatures and energetic readouts.

Readouts. Pre-registered electrophysiological metrics aligned to MRS-derived indices (e.g., PCr/ATP, Pi/ATP, intracellular pH) and complementary peripheral markers, analyzed with time-locked models to probe coupling.

Oversight. Any eventual protocol based on these templates would require full ethical review, risk–benefit assessment, monitoring plans (IRB/DSMB), and clear non-therapeutic framing prior to research use.

5.3. Ethical & Safety Considerations (Research Framing)

Scope & stance. The points below outline general research ethics considerations for studies exploring interventions that may influence systemic or CNS metabolism (e.g., ketogenic strategies, high-dose supplements, investigational mPTP modulators). Content is non-clinical and does not constitute medical advice.

Oversight. Any future protocol evaluating such interventions would require oversight in IRB-approved studies, including prospective review of scientific rationale, feasibility, and risk–benefit justification. When appropriate, independent data and safety monitoring mechanisms may be considered according to institutional policies.

Informed consent. Prospective participants should receive clear information that the interventions are being evaluated for research purposes, with uncertainty regarding effect sizes, durability, and generalizability, as well as a description of foreseeable risks and alternatives consistent with ethical guidelines.

Risk management (research context). Protocols should pre-specify study-level safety governance appropriate to the intervention class (e.g., eligibility criteria, pause/stop rules, and reporting pathways) without implying clinical management. These measures are intended to uphold participant welfare within a research setting and are subject to institutional requirements and applicable regulations.

5.4. Research Priorities & Open Questions (Concise List)

Tier-1 human proof: Proof-of-concept studies in participants/volunteers combining EEG with ^31P-MRS (or other high-resolution metabolic readouts) in drug challenge/withdrawal windows.

Intervention RCTs for candidate metabolic adjuncts: Well-powered, biomarker-anchored trials in phenotypically enriched research cohorts of participants/volunteers.

Refined biomarkers: Validate peripheral metabolic signatures that correlate with brain ATP dynamics in participants/volunteers to enable scalable screening.

Drug development: Pursue CNS-targeted mPTP modulators and mitochondria-targeted antioxidants with favorable safety profiles, advancing from preclinical work toward early-phase evaluation in volunteers.

The above evidence-informed, suggestive framework prioritizes risk stratification, pragmatic monitoring, and biomarker-anchored trials; the next chapter empirically examines how the electrophysiological signatures summarized here map onto quantifiable ATP dynamics in vivo and ex vivo.

Chapter 6. Limitations and Research Gaps

While the evidence presented supports our mechanistic model, the translation from preclinical models to human clinical application is fraught with challenges.

This chapter systematically summarizes the principal limitations that constrain confidence in the causal chain proposed in this manuscript — psychotropic drug exposure → network hyperexcitability → focal ATP depletion → mitochondrial injury — and it translates those limitations into concrete mitigation strategies and prioritized research actions.

6.1. Executive Summary

Preclinical and human-derived data together provide a plausible mechanistic scaffold but also expose important gaps. The two dominant uncertainties are (A) species differences (rodent models versus the human brain) that affect network topology, single-cell biophysics and metabolic responses; and (B) limitations of human samples and measurement modalities, because most human tissue is disease-derived (e.g., resected epilepsy tissue) and in vivo human metabolic imaging has spatial/temporal constraints. Addressing these gaps requires both methodological rigor in reporting and targeted translational experiments.

6.2. Limitation I — Species Differences (Rodent → Human)

Rodent models are indispensable for cellular-level manipulation (genetics, optogenetics, viral sensors) and for high-resolution, causal experiments. However, rodents and humans differ systematically in multiple respects that are directly relevant to the chain of interest:

Network topology: degree of reciprocity, prevalence of short cycles, laminar organization and long-range connectivity differ and thereby alter how focal activity propagates.

Single-cell biophysics: membrane capacitance, input resistance, action potential threshold and other parameters can shift per-cell energy demands for a given synaptic input.

Glial biology & metabolism: astrocyte and microglial metabolic programs and transporter expression vary by species and affect ion/glutamate clearance and lactate shuttling.

The net effect is that the spatial and temporal profile of ATP demand and depletion observed in rodents may not mirror that in humans. Rodents might show broader spread of activity but lower per-cell metabolic cost; humans might show more focal but higher per-cell energy deficits — or other complex combinations. Thus, direct extrapolation from mouse ATP traces to expected human brain ATP kinetics is uncertain.

6.3. Mitigation Strategies

Explicit species labelling and tiered evidence — always state species/preparation and classify evidence level (e.g., Tier-1: same-prep EEG + ATP; Tier-2: drug→firing in vivo + separate firing→ATP slice studies).

Cross-species matched protocols — where possible, run equivalent stimulation/recording protocols in mouse and human surgical tissue (same opsin/chemogenetic stimulation parameters scaled to electrophysiological thresholds) to quantify differences.

Modeling informed scaling — use biophysically grounded network models to translate how topological and single-cell differences change expected ATP demand.

6.4. Limitation II — Human Tissue and Ethical Constraints

Direct in vivo measurements of ATP dynamics in healthy human brain are rarely possible for ethical reasons. Human cellular/physiological data commonly come from: (a) surgically resected tissue (e.g., epilepsy surgery); (b) post-mortem tissue; or (c) imaging modalities (^31P-MRS, FDG-PET) with limited spatiotemporal fidelity. Resected tissue is, by definition, disease-adjacent; post-mortem tissue undergoes agonal/postmortem changes.

Pathology, medication history, gliosis and local reorganization in surgical samples can bias measures of excitability and metabolism; post-mortem artifacts may obscure true in vivo energetics. Consequently, human tissue results are valuable but must be treated as “disease-adjacent evidence” rather than direct surrogates of healthy brain function.

Mitigation strategies

Recommended practices:

Thorough metadata reporting — always report diagnosis, lesion site, medication exposure, time from seizure/insult to resection, and post-mortem intervals.

Use of perioperative human data — when ethical and feasible, pair perioperative intracranial EEG or microdialysis with tissue sampling to provide temporal context.

Leverage minimally invasive human readouts — exploit ^31P-MRS, FDG-PET, high-density EEG and blood/CSF metabolic biomarkers to anchor preclinical findings in vivo.

6.5. Limitation III — Measurement Modality Limits (Spatial/Temporal/Proxy)

Clinical metabolic imaging averages over relatively large voxels and has limited temporal resolution; brief, spatially focal ATP transients may be diluted or temporally unresolved. Genetically encoded ATP sensors in animals provide second-scale resolution but are invasive and not applicable in healthy humans.

FDG-PET and peripheral metabolites are proxies (glucose uptake, systemic metabolic state) and can be confounded by astrocytic uptake, inflammation, and systemic factors. Interpreting them as direct evidence of neuronal ATP depletion requires caution.

Use multimodal, time-aligned recordings where feasible: in animals combine EEG/LFP + optical ATP sensors + NAD(P)H autofluorescence; in humans combine EEG + the best achievable MRS/PET protocol and blood/CSF biomarkers, and report detection limits (spatial voxel size, temporal resolution, SNR).

6.6. Limitation IV — Experimental-State Confounds (Anesthesia, Temperature, Slice Conditions)

Many rodent studies are performed under anesthesia or ex vivo conditions that alter excitability and metabolism. In slices, oxygenation, glucose concentration and ionic composition deviate from physiological milieu. These differences can either exaggerate or mask ATP vulnerability.

[Prefer awake recordings for translational claims; if anesthesia is necessary, include anesthesia controls and report anesthetic type/dose. For slices, maintain physiological temperature, oxygenation and ionic conditions, and report them fully. Consider aged and female animals to improve representativeness.

6.7. Limitation V — Pharmacology, Dose and Regimen Translation

Simple mg/kg comparisons are inadequate for translation. Brain exposure (C_brain), receptor occupancy and chronicity/withdrawal patterns determine physiological impact differently across species. Many preclinical “overdose” paradigms are not clinically representative.

Mitigation Measure and report PK (plasma and where possible brain), and design preclinical dosing regimens to reflect clinically relevant exposures (including chronic dosing and clinically realistic withdrawal paradigms). Distinguish between clinically relevant effects and effects observed only at toxicological doses.

6.8. Limitation VI — Reporting, Statistical and Publication Biases

Small-N studies, selective reporting, lack of pre-registration, and under-reporting of null results can inflate perceived consistency. Without standardized reporting of species/prep/PK and raw data, integrating the evidence base is error-prone.

Mitigation / Good practices

Pre-register experimental protocols and primary endpoints.

Provide sample size justifications and power calculations.

Share raw data (EEG traces, optical recordings, MRS raw files) in repositories.

Use accepted evidence-tier labelling in reviews (Tier-1/Tier-2/Tier-3).

6.9. Practical Recommendations for Authors and Reviewers

When you cite an experimental paper, include at minimum (a) species and preparation, (b) awake vs anesthetized state, (c) drug dose/regimen and PK if available, (d) whether electrophysiology and metabolic measures were simultaneous, and (e) subject/ tissue metadata (age, sex, diagnosis, medications). Use conditional phrasing when generalizing across species.

Preferred: “Data from rodent hippocampal slices show that high-frequency bursting can be followed by rapid ATP declines under the stated experimental conditions; whether identical dynamics occur in human cortex remains to be tested.”

Avoid: “Drug X causes brain ATP depletion in humans,” unless supported by within-subject human evidence.

- 1.

Human Tier-1 studies: within-subject human EEG (or intracranial EEG when clinically warranted) paired with ^31P-MRS/other metabolic readouts during clinically relevant drug exposure or withdrawal windows.

- 2.

Matched cross-species experiments: run equivalent stimulation/recording protocols in mouse and human surgical tissue to quantify topological and cellular contributions to ATP dynamics.

- 3.

Validated peripheral biomarkers: identify blood/CSF markers that reliably correlate with brain ATP dynamics to permit scalable clinical screening.

- 4.

Standardization: implement a reporting checklist (species, prep, state, PK, probe calibration) and encourage data sharing.

We present an integrative “energy-vulnerability” framework that organizes mechanistic nodes and cross-scale evidence connecting network hyperexcitability to persistent bioenergetic failure and structural dysfunction. Key takeaways:

Mismatch between activity-driven ATP demand and mitochondrial supply is central to converting transient electrophysiological events into sustained pathology; critical nodes include MCU-dependent Ca²⁺ uptake, mPTP/ΔΨm collapse, and ROS/mtDNA damage (Kovács et al., 2012; Bernardi et al., 2015; Meyer et al., 2022).

Astrocytic failure (EAAT dysfunction, impaired lactate support) and microglial inflammatory shifts amplify excitotoxic and demyelinating processes.

Pharmacological exposure increases risk through both demand-side (hyperexcitability/withdrawal) and supply-side (mitochondrial toxicity) mechanisms; polypharmacy and repeated withdrawal potentiate these effects.

We recommend a prioritized experimental strategy: synchronize ATP/metabolic measures with electrical recordings in animal models (Tier-2), and develop translational readouts (high-field ^31P-MRS, EEG) in human cohorts (Tier-3) to validate biomarkers and intervention targets.