Introduction

The concept of a reversible process in the study of classical thermodynamics (below simply thermodynamics) is associated with certain difficulties, which are well expressed in the paper by John Norton [

1] in the form of two requirements. On the one hand, a real spontaneous process requires a difference of forces, the driving factor of the process, and, on the other hand, in a reversible process, this difference is zero. In [

1], however, a hasty conclusion is drawn about the impossibility of reversible processes in thermodynamics and therefore it is proposed to consider them as approximations.

In this paper this problem is considered from the point of view of the formalism of thermodynamics, which contains equations with the equality sign (=). The term approximation has a well-defined mathematical meaning of the approximately equal sign (≈). In [

1] (Section 4, '

What thermodynamically reversible processes must do') the formalism of thermodynamics remains unchanged, that is, the equal sign does not change to the approximately equal sign. This, however, in turn calls into question the use of the term approximation, since the equality sign is significantly different from that of approximately equal.

Let us start with two main results from the Carnot cycle:

ηid is the efficiency of the ideal Carnot cycle,

T2 is the heater temperature,

T1 is the refrigerator temperature,

ηreal is the efficiency of a real engine with the same temperatures of the heater and refrigerator. From section 4 of the paper [

1], it follows that the expressions above remain unchanged.

I have written out the two expressions separately to emphasize the equal sign in the first expression. If the first equation remains, then this equation is exact, and the term approximation could not be applied. The equality sign also implies the existence of the ideal Carnot cycle for which this equality holds. Of course, for real processes, this equality is unattainable, which is shown by the next inequality.

Consider the term real process. The mathematical formalism of a physical theory deals with conceptual models that correspond to mathematical equations from this theory. In turn, conceptual models are compared with what is happening in the world. In this sense, the term real process has a double reading: it can mean what is happening in the conceptual model, or it can refer to the world.

The terms approximation and limit are primarily mathematical, and hence one can use them unambiguously to compare mathematical equations with a conceptual model. To compare a conceptual model with the world, these terms could be used at the level of analogy and intuition, when it is hard to ascribe them the exact meaning.

Let me give an example of temperature as a physical quantity from the paper [

2]. The mathematical equations of the physical theory correspond to the conceptual model that leads to the 'ideal measuring instrument' for measuring temperature. Making a real measurement connects the theory of physics with the world, when a real device is compared with the 'ideal device'. The difference with the conceptual models to consider reversible processes is that in this case the transition to measurements is not made. The conceptual model remains as the physical meaning of the equations written, but it is not expected to be used as an 'ideal experiment'.

It is useful to compare the idealizations of the Carnot cycle with the idealizations to consider a mechanical pendulum. The concept of a weightless, inextensible thread, as well as replacement of the body with a point mass, leads the conceptual model with a simple equation of motion, while the elimination of all friction forces leads to endless oscillations. The approximation of small oscillations leads to the equation of the harmonic oscillator. As a result, there is a hierarchy of conceptual models that can be used to create an 'ideal experiment'. This links the conceptual model to measurements of the behavior of a real pendulum. I will return to this example later on.

First, I examine mathematical expressions for two reversible processes in the Carnot cycle with the equality sign (=). I propose conceptual models that correspond to these mathematical expressions and clarify the meaning of the term real process in this case. After that, I return to the discussion of the terminology proposed in [

1] in terms of the separation between thermodynamic formalism, conceptual models, and the world. In [

1] there are no changes in the formalism of thermodynamics, so in the end the mathematical equations discussed are the same, the only difference being related to a didactical question of how to present these equations to study thermodynamics. In conclusion, I give an example proposed by mathematician Zorich for carrying out the reversible process of heat transfer between two bodies with different temperatures. Such an example fits well the discussion of reversible processes, and its consideration would be useful for future discussions.

Sadi Carnot’s Conceptual Model

The concept of a reversible process arose during the creation of classical thermodynamics to find the maximum efficiency of heat engines. Let us start with a visual image of the conceptual model from Sadi Carnot's book [

3] below.

It depicts a cylinder containing a substance under a piston. The substance mass remains constant; such a thermodynamic system is called a closed system. It is assumed that the cylinder and piston have ideal thermal properties (zero heat capacity and infinite heat conductivity) and do not undergo deformation. Therefore, their properties are assumed to have no effect on the interaction of the substance with the external environment. The piston sets the external pressure, and two other bodies, A and B, at the bottom of the drawing are used as thermostats to control temperature of the system. When the cylinder does not touch any of these bodies, there is no heat transfer. When the cylinder is connected to one of the thermostats, there is heat transfer. Heat sources are another idealization - it is assumed that the heat transfer does not change their temperature.

As can be seen, even before considering processes with the substance, many idealizations are made in the spirit of the example with a mechanical pendulum. Carnot's goal was to eliminate losses, and the simplifications above remove many real processes that take place in real heat engines to exclude losses:

Ideal heat sources exclude the need to consider the fuel combustion and associated heat transfer processes.

The ideal thermal and mechanical properties of the cylinder and piston exclude the need to include mechanics of the deformable body, as well as their thermal properties.

It is assumed that chemical and phase reactions do not occur in the substance under the piston, that is, the thermal equation of state p(V, T) is assumed; pressure (p) is related to the volume (V) and temperature of the substance (T) only.

Thus, the real processes to discuss the Carnot cycle are in fact quite far from what happens in a real heat engine; they belong to the already idealized conceptual model presented in Carnot's drawing.

The Carnot cycle consists of two isothermal and two adiabatic processes in which the substance state changes. To exclude losses during these changes, additional assumptions are made; this step leads to certain difficulties in the study of thermodynamics. First, an equilibrium (quasi-static) process is introduced, and then one more condition is added, which is required for the equilibrium process to become reversible. The difference is that the equilibrium process pays attention to the state of the substance only, while the reversible process requires more - the preservation of the entropy of the entire system, including substance and heat sources together.

The formalism of thermodynamics does not contain time. This is another difficulty in the study of thermodynamics to understand processes in the Carnot cycle. The term real process thus refers to a process that takes place over time, and hence its description falls outside of thermodynamics. As correctly noted in [

1], the formalism of continuum mechanics is required, but then it is necessary to distinguish conceptual models of continuum mechanics from conceptual models of timeless thermodynamics.

In [

1] there is also a discussion of statistical mechanics, but statistical mechanics is not considered in this paper. The reason is that the formalism of classical thermodynamics refers to a substance at the level of continuum mechanics. Conceptual models of statistical mechanics require special consideration, since the transition beyond the continuous media is carried out. In statistical mechanics, fluctuations appear but they are absent in thermodynamics; also in statistical mechanics, equations are symmetric in time, leading to a common problem with the arrow of time. In thermodynamics, the Clausius inequality (it is also considered in [

1]) is implicitly related to the time-asymmetric equations of continuum mechanics, where there is no problem with the arrow of time [

4].

Equilibrium Process to Achieve Maximum Work

Carnot's goal was to eliminate losses during the change of the substance state to find the maximum work (

Amax) produced by the substance during the transition from one state to another. To achieve this goal, first, the substance state under the piston must remain uniform, that is, there must be no gradients of temperature and pressure. Second, the pressure above the piston must be equal to the substance pressure in the cylinder. Let us consider the mathematical equation of the maximum work, which corresponds to such idealizations. This is the integral of the thermal equation of state

p(

V,

T) when the volume changes from

V1 to

V2:

As an example, let us take the equation of state of one mole of the ideal gas:

pV = R

T. This gives the maximum work in the isothermal process, which can be found in many textbooks of thermodynamics:

Such integrals belong to the essential part of thermodynamics. The use of the term approximation in this case is unacceptable, since approximation with respect to the equation means approximately equal (≈). However, the integrals in the formalism of thermodynamics are exact.

Now the task is to find a conceptual model that exactly corresponds to the integral above. The process of piston motion at the level of continuum mechanics (a real process) necessarily leads to temperature and pressure gradients. Thus, the first step is to use Carnot’s drawing, in which temperature and pressure gradients do not occur. Didactically, this can be represented as a very slow movement of the piston, when the temperature and pressure of the substance remain almost uniform.

The second step is related to the external pressure above the piston, since this pressure must be used to estimate the work. The maximum work integral requires that the uniform pressure of the substance during the process remains equal to the external pressure. In such a conceptual model, the integral is called an equilibrium process, since the substance is in a state of mechanical equilibrium in each point of the integral.

At this point, a contradiction discussed in [

1] appears. On the one hand, the conceptual model requires a mechanical equilibrium of the substance state (internal pressure is equal to external pressure), on the other hand, the real process in continuum mechanics requires a difference between two pressures; only in this case there is a spontaneous movement of the piston. For didactic purposes in the study of thermodynamics, the concept of a quasi-static process is introduced, when the external pressure changes in infinitesimal portions. The usual visual image to present this idea is associated with a mountain of sand above the piston. We remove or add a grain of sand during the process of expansion or contraction. The integral above is obtained by reducing the grain of sand to the infinitesimal.

The usual objection [

1] comes from the fact that such a limit transition makes the process in continuum mechanics impossible. However, in [

1] there is no difference between the conceptual model of thermodynamics and the conceptual model of continuum mechanics. No one disputes that for a real process in continuum mechanics to take place, it is necessary to disturb the state of equilibrium. At the same time, nothing prevents to compute the integral above and the conceptual model in thermodynamics must corresponds to this integral. Naturally, the equilibrium process is not spontaneous, but this is always emphasized in the study of thermodynamics — the equilibrium process cannot be carried out in the real world.

In the paper by Giovanni Valente '

On the paradox of reversible processes in thermodynamics' [

5] the importance of equations in thermodynamics is recognized and it is proposed to use the term quasi-process by Afanassjewa-Ehrenfest. In this case, the prefix

quasi implies that we are not talking about a real process in continuum mechanics. It could be possible that this helps to distinguish a thermodynamic process from a process in continuum mechanics.

More important is the discussion of absence of time in thermodynamics conceptual models. This makes the difference for Carnot's idealization as compared with the idealization of the mechanical pendulum. The absence of time leads to additional difficulties in understanding thermodynamics, and this requires special effort in the study of thermodynamics. A good way of exposition is to consider the integral above, because it clearly shows the necessary changes in the substance state that lead to the maximum possible mechanical work.

It is important to emphasize that in the integral without time there remains the direction of the process, which is set by the limits of the integral. They show whether we are talking about contraction or expansion of the substance. One can also say that the integral is the definition of an equilibrium (quasi-static) process, and the discussion of the conceptual model in thermodynamics as compared with the conceptual model of continuum mechanics serves the didactic goals to employ such integrals successfully for solving practical problems.

Isothermal Reversible Process

An isothermal process requires additional consideration of heat transfer with a heat source. According to the first law, the movement of the piston in this case is related to heat transfer as follows:

where

Q is the amount of heat,

ΔU is the change in internal energy. In the case of an adiabatic processes

Q=0 (the substance is disconnected from the heat source), but in the case of isothermal processes

Q≠0. In the case of the ideal gas, the internal energy at constant temperature is independent of volume and therefore for the isothermal process of the ideal gas we have:

As already mentioned, a heat source is a product of idealization — it requires an object with given temperatures so large that the heat transfer does not change its temperature. Thus, it possible to represent an isothermal process when, despite heat transfer, the temperature of the heat source and the substance does not change.

For the reversible process, there is an additional condition in thermodynamics. The concept of thermodynamic reversibility includes not only the substance state, but also the state of all other objects in the system (in Carnot's drawing, these are the heat sources). Thermodynamic reversibility implies that performing a process in one direction and then in the opposite direction must bring all objects in the system, including heat sources, back to their original state.

This is related to the entropy change of the heat source (

ΔSh):

where

Q is the amount of heat transferred,

Th is the temperature of the heat source. To return the heat source to the same state, it is required that the temperature of the substance during the isothermal process must be strictly equal to the heat source temperature. If the heat source temperature is different from the substance temperature, then the change in the entropy of the heat source is not equal to the change in the substance entropy, and therefore there is an irreversible increase in the entropy of the entire system.

On the other hand, in continuum mechanics, a temperature difference is required for heat transfer, since heat in a spontaneous process is transferred only from a hotter to a cooler body. If two bodies have the same temperatures, then they are in a state of thermal equilibrium and the heat flux between them is zero. A contradiction appears discussed in [

1], similar to the case of mechanical equilibrium.

Again, a limit transition should be imagined. We start with a small temperature difference that ensures the transfer of heat in the desired direction and then reduce this difference to an infinitesimal value. At zero difference, the temperature of the substance is equal to the temperature of the heat source, but the amount of heat required to carry out the isothermal process remains. It is important that we must assume that in the isothermal process there is a heat exchange between the heat source and the substance even if their temperatures are equal. At first glance, this seems to be impossible, and in the study of thermodynamics, special attention should be paid to this issue; it must be emphasized that it does not lead to internal contradictions in the formalism of thermodynamics.

Discussion

Thermodynamics and continuum mechanics are closely related, but they are two different theories. They have different mathematical formalisms, and the main difference is related to the absence of time in thermodynamics. This, in turn, leads to different conceptual models and different requirements for a process in continuum mechanics and thermodynamics. Unfortunately, in [

1] this difference has not been noticed. Below, first the formalism of thermodynamics is considered, and then the relationship between thermodynamics and continuum mechanics is discussed.

I start with a sarcastic statement by Clifford Truesdell [

7], which shows the 'culture shock' of an expert in continuum mechanics when he comes to thermodynamics:

‘He is told that dS is a differential, but not of what variables S is a function; that dQ is a small quantity not generally a differential; he is expected to believe not only that one differential can be bigger than another, but even that a differential can be bigger than something which is not a differential. He is loaded with an arsenal of words like piston, boiler, condenser, heat bath, reservoir, ideal engine, perfect gas, quasi-static, cyclic, nearly in equilibrium, isolated, universe—words indeed familiar in everyday life, doubtless much more familiar than "tangent plane" and "gradient" and "tensor" which he learned to use accurately and fluently in the earlier chapters, but words that never find a place in the mathematical structure at all, words the poor student of science is expected to learn to hurl for the rest of his life in a rhetoric little sharper than that wielded by a housewife in the grocery store.’

Truesdell's ideal was to combine thermodynamics with continuum mechanics within the framework of rational thermodynamics (a variant of nonequilibrium thermodynamics). This is another way of looking at the original problem, and I come back to it shortly at the end of the discussion. For now, the goal of Truesdell's quote is to admit that conceptual models of thermodynamics are old-fashioned. Yet we must not forget that they have been extremely successful in solving a huge number of problems.

The first step is to separate conceptual models of thermodynamics from everyday life. Here Truesdell is completely wrong; the terms above are indeed related to experience with heat engines, but their meaning can be understood only together with the mathematical formalism of thermodynamics. These are conceptual models that help to study thermodynamics and to use it to solve practical problems.

In two previous sections, mathematical equations corresponding to equilibrium and reversible processes in the Carnot cycle were given. From the point of view of didactics, the proposal from the paper [

1] to call these equations approximations should be strongly rejected. The term approximation is reserved for the approximately equal sign (≈), but the equations of thermodynamic processes in the previous sections are exact.

Let us consider the integral that is used to determine absolute entropy at constant pressure:

Formally, this integral does not differ from the integrals above, since it assumes a substance in the equilibrium state at each point. The use of the term approximation in relation to this equation is unacceptable, this is the exact equation. If we follow the logic of [

1], then the value of the absolute entropy should be called an approximation, but it is absurd.

The way out of this situation should be connected to the difference between conceptual models of thermodynamics and continuum mechanics. The contradiction discussed in [

1] arises when the requirements for the process in continuum mechanics are transferred to the process in thermodynamics. However, these are different mathematical formalisms, and therefore the term process in thermodynamics and continuum mechanics means different things. In thermodynamics, there is no time; this is one of the difficulties to study thermodynamics, and it is necessary to convey the difference between thermodynamics and continuum mechanics. In this regard, the correct approach could be found in the paper '

Isothermal heating: purist and utilitarian views' [

8], also see the paper '

Reversible and irreversible heat engine and refrigerator cycles' [

9] with a correct description of thermodynamic cycles.

Let me remind once again of the successful development of thermodynamics over the past century and a half. Provided that the mathematical formalism of thermodynamics is left unchanged, the question arises what is then should be changed. There are didactic problems to study thermodynamics, but the term approximation in relation to reversible processes does not help to solve them. The main goal in studying thermodynamics is to understand that integrals in thermodynamics are exact, so the term approximation only increases existing problems.

Now let us discuss the connection between thermodynamics and continuum mechanics. In [

1] a proposal is made to call a thermodynamic process as an approximation of the continuum mechanics processes. Let us consider this statement from the point of view of mathematical formalisms. The Fourier heat equation and the Navier-Stokes equations are examples of transport equations in continuum mechanics. In this case, the statement from [

1] is equivalent that the integrals for thermodynamic processes from the previous sections are approximations of the heat equation and the Navier-Stokes equations. I am not sure if such a statement has a meaning.

A more correct expression of the connection is associated with the limit transition. In [

1] the consideration of Pierre Duhem (see Figure 1 in this article) is described as well as a similar approach has been used to study the influence of the difference in the temperature of heat sources and substance on the maximum efficiency of the heat engine. It should be noted that Henri Poincaré [

6] has made a similar study. The results coincide with the use of the same temperature of the heat source and the substance. Thus, the efficiency of the ideal heat engine, and as a result the entire formalism of thermodynamics can be represented as the limiting transition from continuum mechanics.

However, in [

1] in section 3 '

Idealizations created by limits' the idea is rejected that such a limiting transition can be regarded as idealization, and therefore the term approximation is introduced. I have already discussed the inadequacy of the term approximation, but at the same time I believe that the term idealization fits well to the connection between thermodynamics and continuum mechanics. The objection in [

1] is based on incorrect expectations that the properties of a process in continuum mechanics should be preserved for a process in thermodynamics. Once again, there is no time in thermodynamics, so it is impossible to expect that a timeless process in thermodynamics retains all the properties of a process in continuum mechanics.

It is more reasonable to understand idealization as the elimination of all losses and thus the appearance of processes in the Carnot cycle, for which the entropy of the entire system does not change. Carnot's task was to find the maximum possible efficiency of a heat engine, and from this point of view, the idealization he introduced provided an exact solution to this problem. The price for this solution was that the final equations did not have time, and this is the only difference between idealization in thermodynamics and idealization in the case a mechanical pendulum.

Now a few words about non-equilibrium thermodynamics. This is another possible way to discuss the problem when non-equilibrium thermodynamics is positioned as a unification of thermodynamics and continuum mechanics. There are textbooks in which thermodynamics is presented this way - thermodynamics as a special case of non-equilibrium thermodynamics, for example [

10]. The disadvantage of this approach is that for most practical problems the normal formalism of thermodynamics is sufficient, and then this leads to unnecessary complication. Another problem, non-equilibrium thermodynamics continues to evolve and there are several variants, while the formalism of thermodynamics is independent of nonequilibrium thermodynamics. This issue is discussed in more detail in [

11].

In the next section, I present one example that is well suited to discuss conceptual models of thermodynamics. Heat transfer between two bodies with different temperatures is an irreversible process, and this is always emphasized in thermodynamics textbooks. In this case, the transition to a very slow process does not help, the process remains irreversible. The entropy of a system consisting of two bodies with different temperatures increases as heat is transferred.

V. A. Zorich in his book ‘

Mathematical Aspects of Classical Thermodynamics‘ [

12] proposed problem 1, which shows a way to the reversible heat exchange while maintaining Clausius's formulation 'Heat cannot pass by itself (without compensation) from a colder body to a warmer one'. This consideration is very useful to discuss reversible processes. Of course, the proposed process cannot be carried in reality out, but the proposed conceptual model provides a new fresh look at heat transfer.

Reversible Heat Exchange Process Between Two Bars with Different Temperatures

Consider two bars of the same length and cross-section, made of a material with heat capacity not depending on temperature. The first bar is at temperature of 100ºC, and the second at 0ºC. When the bars come into contact, the heat passes from hotter to colder, and in the end, the temperature of both bars will be 50ºC. Below is the entropy change in this process — for simplicity, the heat capacity of each bar was taken equal to unity:

As expected, the entropy increases; the process is irreversible. It is impossible to return the bars from the final to original state without energy from the outside. This case is referred below as the standard heat transfer.

Clever mathematician Zorich proposed the following. Let us assume that each bar is divided in half by an adiabatic wall. Now we carry heat transfer out by moving one of the bars along the other. This idea is shown schematically below, together with the resulting temperatures during the bar movement. As usual, it is assumed that the bar movement does not require additional energy - it is a frictionless process and it occurs at the same height.

Starting position – the bars do not touch each other:

Now the bar is moved half the length:

Due to adiabatic walls, heat transfer occurs among the adjoining parts of the bars only. Let us make the next step:

Now is the last step, because the bar can be moved father:

The achievement of thermal equilibrium in parts led to the fact that the average temperature of the lower bar became higher than the average temperature of the upper bar. The second law of thermodynamics is not violated, heat has been all the time moving from a hotter to a colder body, but at the same time it was possible to transfer more energy from the hot body to the cold one than in the standard heat transfer without partitions. The entropy increased in this process by a smaller amount compared to the standard heat transfer: 0.021.

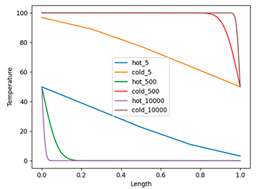

The next step is to increase the number of partitions and examine the limit when the number of partitions goes to infinity. I limit myself to presenting results of a small Python program (reversible_heat_exchange.py, see file in the Supplementary materials), which calculates the final temperature in both rods for a given number of partitions. Below there is a plot made by this program:

The plot shows the temperature distribution in the two bars after the completion of the movement process for three different bar partitions: 5, 500, and 10000 pieces. The temperature of the pieces is connected by straight lines, which creates a bit incorrect representation, especially in the case of 5 pieces, since there must be five horizontal lines. But for larger numbers of partitions, this plays almost no role.

The final temperature distributions of the bar with a reference temperature of 100ºC (hot) are at the bottom of the graph – during this process, the bar is cooled. At the same time, the bar with the initial temperature of 0°C (cold) heats up eventually to 100°C. The temperature of the leftmost point of the bar with the initial temperature of 100°C and the rightmost point of the bar with the initial temperature of 0°C remains equal to 50°C. However, the areas adjacent to these points is getting smaller as the number of partitions increases and eventually, they turn into delta functions.

The program also computes the change in entropy as a function of the number of partitions. It decreases and thus shows that when the number of partitions goes to infinity, it should be going to zero. At the limit of infinite number of partitions, the process proposed by Zorich is the reversible process of transferring heat from one bar (100ºC) to another (0ºC)! The difference between this process and the isothermal reversible process is due to the fact that it is not the temperature difference that is considered as infinitesimal, but the amount of the substance being heated.

An infinite number of partitions corresponds to the use of a material with anisotropic thermal conductivity, where the thermal conductivity in the direction between the bars is infinitely greater than the thermal conductivity in the other two directions. I see no reason why such material cannot be called as the idealization. Imagine two bars with such anisotropic thermal conductivity. The initial temperature of one bar is 100ºC, and the other is 0ºC. Now infinitely slowly pass one bar past the other - the bars have changed temperatures. One can now move the bars in the opposite direction and there will be an exchange of temperatures again. At the same time, the second law in the form of Clausius's statement is not violated, heat all the time passes from a hotter to a colder body.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

References

- Norton, J.D. The impossible process: Thermodynamic reversibility. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in Hist. and Philosophy of Modern Physics 55 (2016): 43-61.

- Rudnyi, E. The Problem of Coordination: Temperature as a Physical Quantity, 2025, preprint. [CrossRef]

- Carnot, S. Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire and on Machines Fitted to Develop that Power, 1897 (in French in 1824).

- Rudnyi, E. Clausius Inequality in Philosophy and History of Physics, 2025, preprint. [CrossRef]

- Valente, G. On the paradox of reversible processes in thermodynamics. Synthese 196, no. 5 (2019): 1761-1781.

- Poincaré, H. Termodynamique, 1908, first published in 1892. I have read Russian translation, 2005.

- Truesdell, C.; Thermodynamics, R. 1969.

- H. S. Leff and C. E. Mungan. Isothermal heating: purist and utilitarian views, European Journal of Physics 39, no. 4 (2018), 2018; 39.

- Leff, H.S. Reversible and irreversible heat engine and refrigerator cycles. American Journal of Physics 86, no. 5 (2018): 344-353.

- Kondepudi, D.; Prigogine, I. Modern Thermodynamics. From Heat Engines to Dissipative Structures, 2015.

- Rudny, E.B. Clausius Inequality in Classical Thermodynamics, Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry, 2026, in press.

- Zorich, V.A. Mathematical Aspects of Classical Thermodynamics (in Russian), 2019.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).