Submitted:

31 October 2025

Posted:

31 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

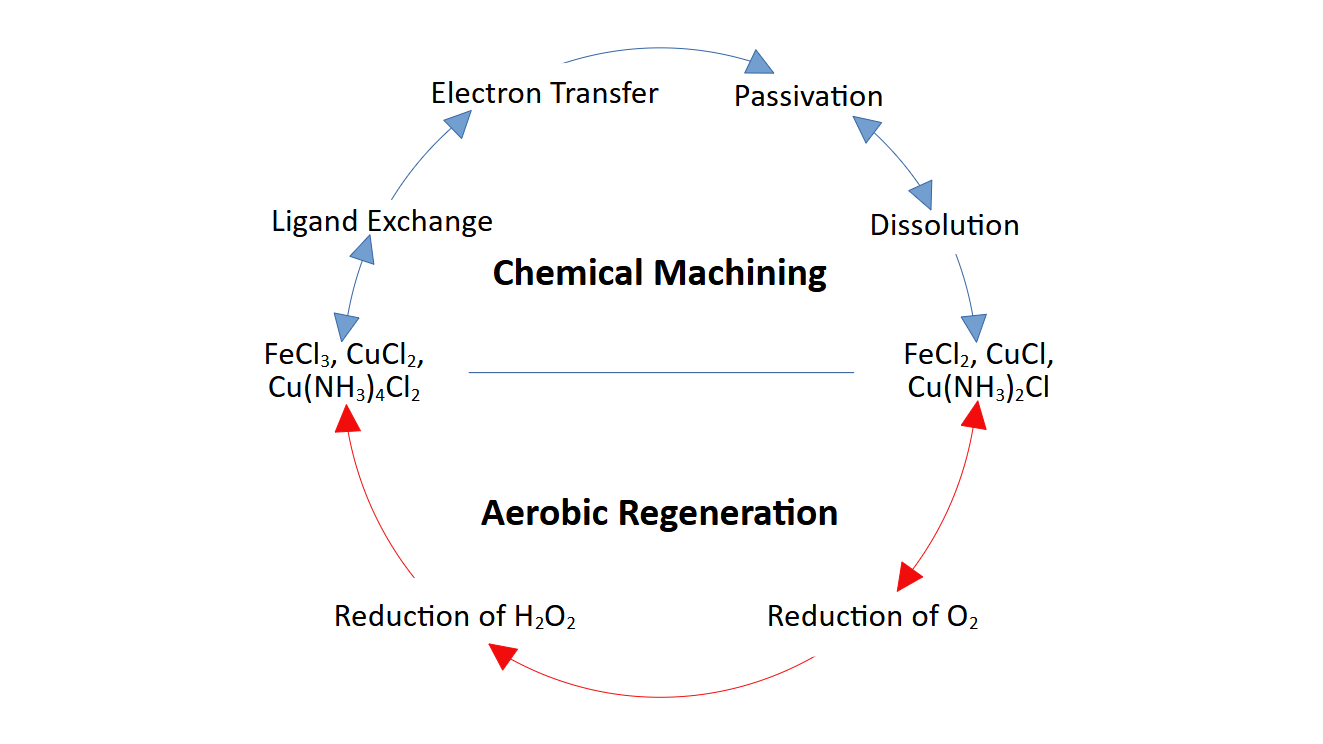

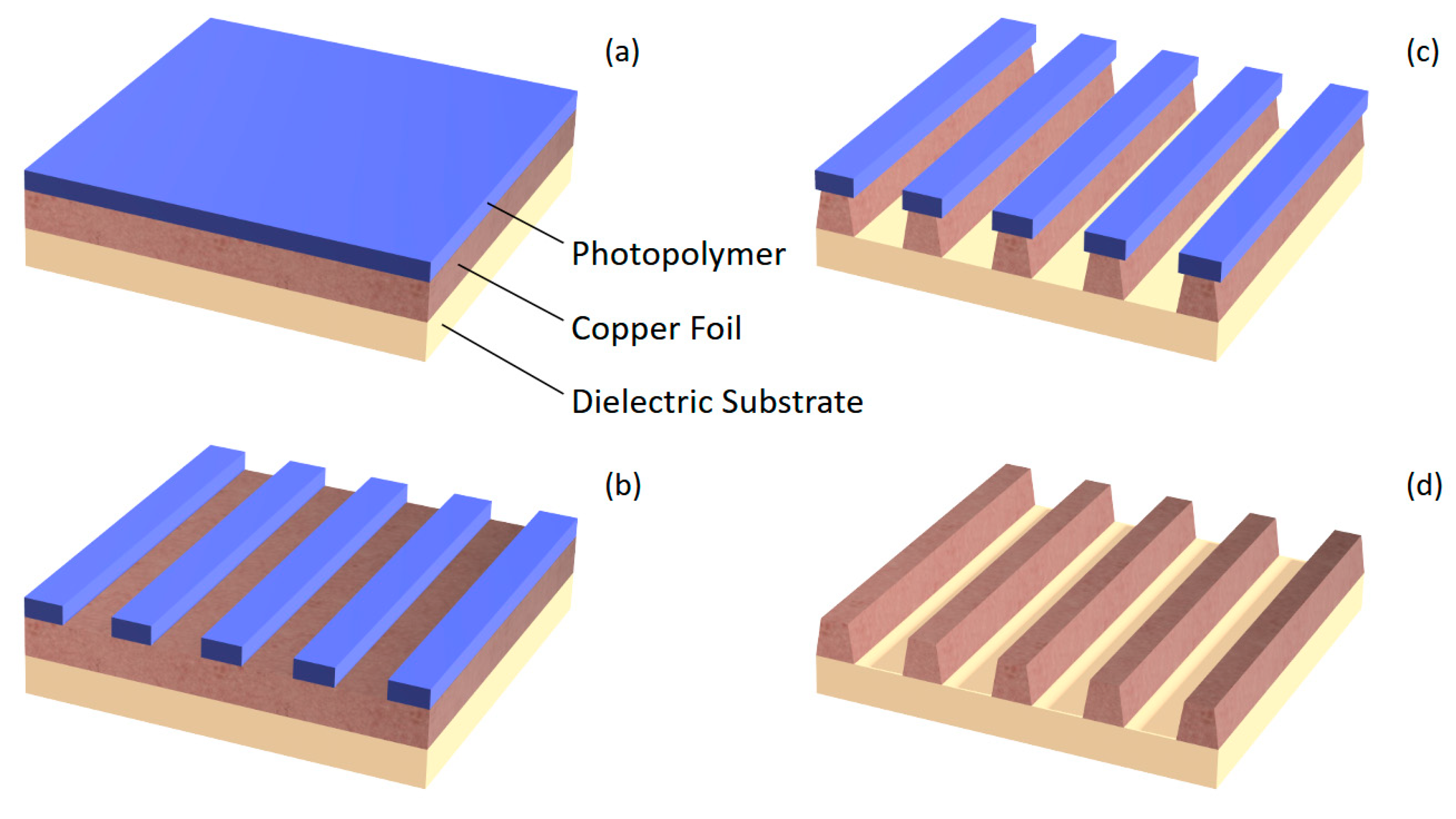

2. Chemical Machining

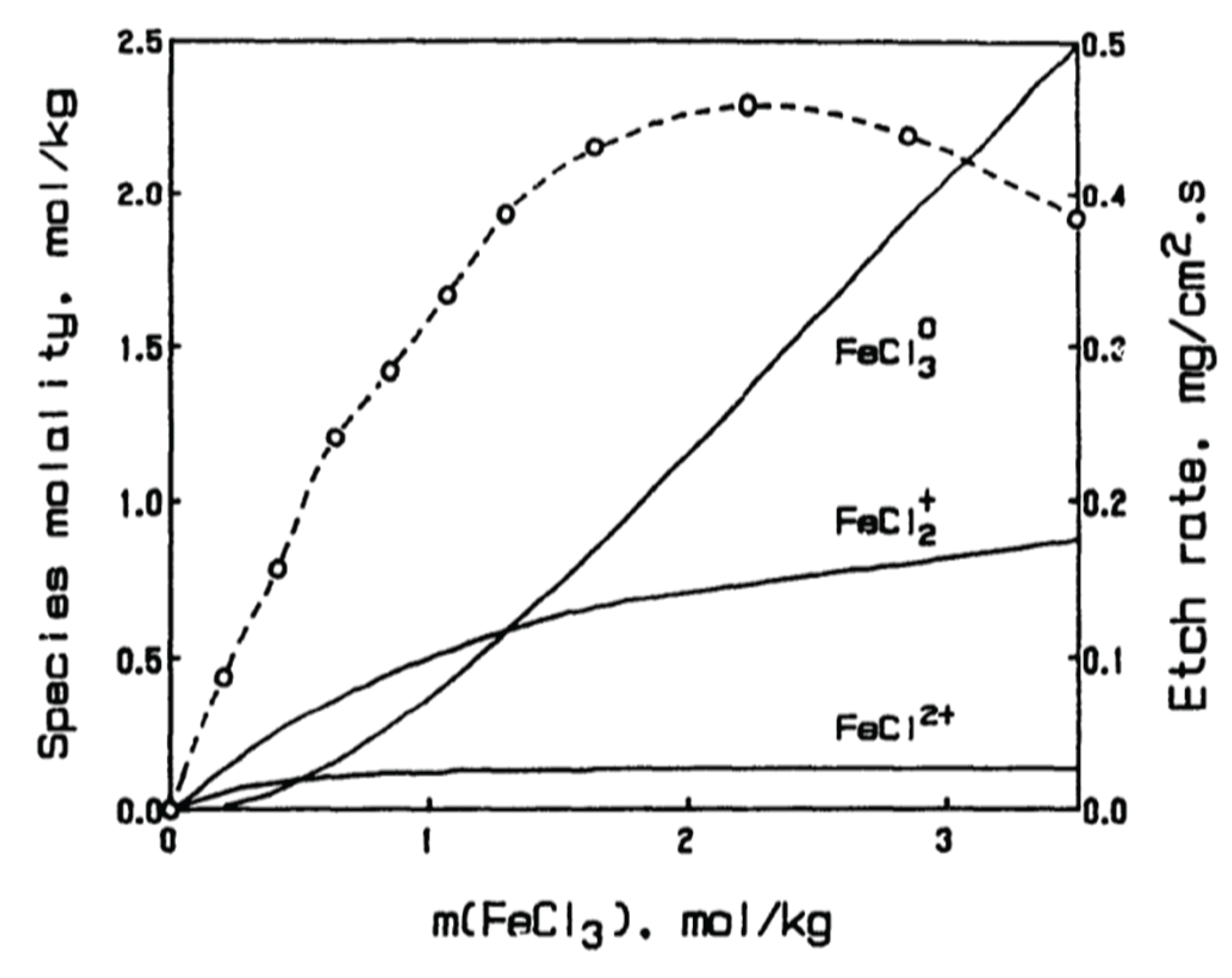

2.1. Ferric Chloride

2.2. Acidic Cupric Chloride

2.3. Alkaline Cupric Ammine Chloride

3. Aerobic Regeneration

3.1. Ferric Chloride

3.2. Acidic Cupric Chloride

3.3. Alkaline Cupric Ammine Chloride

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ET | Electron Transfer |

| DFT | Density Functional Theory |

| EXAFS | X-ray absorption fine structure |

References

- Datta, M.; Romankiw, L.T. Application of Chemical and Electrochemical Micromachining in the Electronics Industry. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1989, 136, 285C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakir, O. Photochemical Machining of Engineering Materials. In Proceedings of the Trends in the Development of Machinery and Associated Technology; TMT: Istanbul, Turkey, 2008; pp. 109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Burrows, W.H.; Lewis, C.T.Jr.; Saëre, D.E.; Brooks, R.E. Kinetics of the Copper-Ferric Chloride Reaction and the Effects of Certain Inhibitors. Ind. Eng. Chem. Proc. Des. Dev. 1964, 3, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakır, O. Review of Etchants for Copper and Its Alloys in Wet Etching Processes. KEM 2007, 364–366, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.-S.; Hess, D.W. Chemical Etching and Patterning of Copper, Silver, and Gold Films at Low Temperatures. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2015, 4, N3084–N3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartzell, J.C. Etching Parameters: Their Individual and Collective Impact on High Density Circuit Production. Circuit World 1981, 8, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou, M.; Alkire, R. Anisotropic Chemical Etching of Copper Foil: I. Electrochemical Studies in Acidic Solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1993, 140, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou, M.; Alkire, R. Anisotropic Chemical Etching of Copper Foil: II. Experimental Studies on Shape Evolution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1993, 140, 1348–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, R.M. Effect of Applying Air Pressure during Wet Etching of Micro Copper PCB Tracks with Ferric Chloride. International Journal of Materials Research 2022, 113, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzone, A.A.G.; Reverberi, A.P. An Experimental Evaluation of an Etching Simulation Model for Photochemical Machining. CIRP Annals 2010, 59, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou, M.; Alkire, R. Anisotropic Chemical Pattern Etching of Copper Foil: III. Mathematical Model. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1994, 141, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, A.S.; Stenger, H.G.; Georgakis, C.; Covert, K.L.; Kurowski, J.A. Etch Profile Development in Spray Etching Processes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1992, 139, 2202–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakir, O. Copper Etching with Cupric Chloride and Regeneration of Waste Etchant. Journal of Materials Processing Technology 2006, 175, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-C.; Lee, Y.-S.; Lee, J.; Kwon, H.-W.; Lee, J.-H. Etching Behaviors of Galvanic Coupled Metals in PCB Applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 Pan Pacific Microelectronics Symposium (Pan Pacific); February 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Çakır, O.; Temel, H.; Kiyak, M. Chemical Etching of Cu-ETP Copper. Journal of Materials Processing Technology 2005, 162–163, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, F.; Li, C.; Yang, L.; Xu, C.; Song, Z. Influence of Etchants on Etched Surfaces of High-Strength and High-Conductivity Cu Alloy of Different Processing States. Materials 2024, 17, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Li, K.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Chen, X. Electrochemical and Theoretical Studies for Forward Understanding the Mechanism and the Synergistic Effects of Accelerating Ions in Copper Foil Etching. Materials Today Communications 2025, 42, 111483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, C.T.J.; Ponce De Leon, C.; Walsh, F.C. Copper Deposition and Dissolution in Mixed Chloride–Sulphate Acidic Electrolytes: Cyclic Voltammetry at Static Disc Electrode. Transactions of the IMF 2015, 93, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DARCHEN, A.; DRISSI-DAOUDI, R.; IRZHO, A. Electrochemical Investigations of Copper Etching by Cu(NH3)4Cl2 in Ammoniacal Solutions. Journal of Applied Electrochemistry 1997, 27, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.S.; Bartlett, J.H. Convection and Film Instability Copper Anodes in Hydrochloric Acid. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1958, 105, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kear, G.; Barker, B.D.; Walsh, F.C. Electrochemical Corrosion of Unalloyed Copper in Chloride Media––a Critical Review. Corrosion Science 2004, 46, 109–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.M.; Almond, H.J.A. Characterisation of Aqueous Ferric Chloride Etchants Used in Industrial Photochemical Machining. Journal of Materials Processing Technology 2004, 149, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.; Nobe, K. Electrodissolution Kinetics of Copper in Acidic Chloride Solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1979, 126, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, C. The Kinetics of Copper Etching in Ferric Chloride-Hydrochloric Acid Solutions, McGill University, Department of Chemical Engineering, 1992.

- Brown, O.R.; Wilmott, M.J. A Kinetic Study of the Cu(NH3)4II/Cu(NH3)21 Redox Couple at Carbon Electrodes. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry and Interfacial Electrochemistry 1985, 191, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, R.T.; Haunschild, P.A.; Liddell, K.C. A Mathematical Model for Calculation of Equilibrium Solution Speciations for the FeCl3-FeCl2-CuCl2-CuCl-HCl-NaCl-H2O System at 25 ‡C. Metall Trans B 1984, 15, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramette, R.W. Copper(II) Complexes with Chloride Ion. Inorg. Chem. 1986, 25, 2481–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, F.A.; Wilkinson, G.; Murillo, C.A.; Bochmann, M. 11. In Advanced Inorganic Chemistry; A Wiley-Interscience publication; Wiley: New York, 1999; ISBN 978-0-471-19957-1. [Google Scholar]

- Saubestre, E.B. Copper Etching in Ferric Chloride. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1959, 51, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apted, M.J.; Waychunas, G.A.; Brown, G.E. Structure and Specification of Iron Complexes in Aqueous Solutions Determined by X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1985, 49, 2081–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahm, Ulrich. ; Patel, R.C.; Matijevic, Egon. Thermodynamics and Kinetics of Aqueous Iron(III) Chloride Complexes Formation. J. Phys. Chem. 1979, 83, 1689–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, A.L.; Bush, S.F. Raman Spectral Investigation of the Complex Species of Ferric Chloride in Concentrated Aqueous Solution. Appl Spectrosc 1972, 26, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, C.A.; Seward, T.M. A Spectrophotometric Study of Aqueous Iron (II) Chloride Complexing from 25 to 200 °C. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1990, 54, 2207–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-S. Chemical Equilibria in Ferrous Chloride Acid Solution. Met. Mater. Int. 2004, 10, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luin, U.; Arčon, I.; Valant, M. Structure and Population of Complex Ionic Species in FeCl2 Aqueous Solution by X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy. Molecules 2022, 27, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, I. Ferric Chloride Complexes in Aqueous Solution: An EXAFS Study. J Solution Chem 2018, 47, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, R.J.; Liddell, K.C. Rate Law and Mechanism for the Oxidation of Copper(I) by Iron(III) in Hydrochloric Acid Solutions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1990, 29, 1178–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereshchenko, A.S.; Olshin, P.K.; Karabaeva, K.E.; Panov, M.S.; Wilson, R.M.; Kochemirovsky, V.A.; Skripkin, M.Y.; Tveryanovich, Y.S.; Tarnovsky, A.N. Mechanism of Formation of Copper(II) Chloro Complexes Revealed by Transient Absorption Spectroscopy and DFT/TDDFT Calculations. J Phys Chem B 2015, 119, 8754–8763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramette, R.W.; Fan, G. Copper(II) Chloride Complex Equilibrium Constants. Inorg. Chem. 1983, 22, 3323–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou, M.; Alkire, R. Modelling of Copper Etching in Aerated Chloride Solutions. Journal of Applied Electrochemistry 1998, 28, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathaway, B.J. A New Look at the Stereochemistry and Electronic Properties of Complexes of the Copper(II) Ion. In Proceedings of the Complex Chemistry; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1984; pp. 55–118. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, J.J. Chloride Complexes of Copper(I) Chloride in Aqueous Solution. J. Phys. Chem. 1980, 84, 2241–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelka, M.; Burda, J.V. Theoretical Description of Copper Cu(I)/Cu(II) Complexes in Mixed Ammine-Aqua Environment. DFT and Ab Initio Quantum Chemical Study. Chemical Physics 2005, 312, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, D. The CCDC Database of Crystal Structures of Tetraamminecopper (II) [Cu(NH3)4]2+: Complicated Geometry of a Well-Known Complex Ion. Journal of the Korean Chemical Society 2022, 66, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larin, V.I.; Khobotova, E.B.; Datsenko, V.V.; Dobriyan, M.A. The Chemical Passivation of Copper in Ammonia Solutions Containing Chlorine Ions. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 82, 1490–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braish, T.F.; Duncan, R.E.; Harber, J.J.; Steffen, R.L.; Stevenson, K.L. Equilibria, Spectra, and Photochemistry of Copper(I)-Ammonia Complexes in Aqueous Solution. Inorg. Chem. 1984, 23, 4072–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, K.B.; Persson, I. The Coordination Chemistry of Copper(I) in Liquid Ammonia, Trialkyl and Triphenyl Phosphite, and Tri-n-Butylphosphine Solution. Dalton Trans. 2004, 1312–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.M.; Jefferies, P. An Economic, Environment-Friendly Oxygen-Hydrochloric Acid Regeneration System for Ferric Chloride Etchants Used in Photochemical Machining. CIRP Annals 2006, 55, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemcut Corporation Process Guidelines for Cupric Chloride Etching 2015.

- Chemcut Corporation Process Guidlines for Alkaline Etching 2002.

- Fadhil, B.H. COPPER ETCHING IN AIR REGENERATED CUPRIC CHLORIDE SOLUTION. jcoeng 2010, 16, 5771–5777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, O.D.; Cutler, L.H. New Method for Etching Copper. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1958, 50, 1539–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, W.L.; Smith, J.C.; Harriott, P. Gas Absorption. In UNIT OPERATIONS OF CHEMICAL ENGINEERING; McGraw-Hill, 2005; pp. 607–610 ISBN 0-07-124710-6.

- Narita, E.; Lawson, F.; Han, K.N. Solubility of Oxygen in Aqueous Electrolyte Solutions. Hydrometallurgy 1983, 10, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, H.; Yampolski, Y.; Young, C.L. IUPAC-NIST Solubility Data Series. 103. Oxygen and Ozone in Water, Aqueous Solutions, and Organic Liquids (Supplement to Solubility Data Series Volume 7). Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data 2014, 43, 033102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groisman, A.S.; Khomutov, Ν.Ε. Solubility of Oxygen in Electrolyte Solutions. Russian Chemical Reviews 1990, 59, 707–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromans, D. Oxygen Solubility Modeling in Inorganic Solutions: Concentration, Temperature and Pressure Effects. Hydrometallurgy 1998, 50, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akilan, C.; Nicol, M.J. Kinetics of the Oxidation of Iron(II) by Oxygen and Hydrogen Peroxide in Concentrated Chloride Solutions – A Re-Evaluation and Comparison with the Oxidation of Copper(I). Hydrometallurgy 2016, 166, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, M.; Majima, H.; Izaki, T. A Kinetic Study on the Oxidation of Ferrous Ion with Dissolved Molecular Oxygen. Denki Kagaku1961 1979, 47, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, M.J. Kinetics of the Oxidation of Copper(I) by Hydrogen Peroxide in Acidic Chloride Solutions. South African Journal of Chemistry 1982, 35, 77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hock, S.J. Precipitation of Hematite and Recovery of Hydrochloric Acid from Aqueous Iron(II, III) Chloride Solutions by Hydrothermal Processing, McGill University, Department of Mining and Materials Engineering, 2009.

- Kim, Dae-Weon; Park, Il-Jeong; Kim, Geon-Hong; Chae, Byung-man; Lee, Sang-Woo; Choi, Hee-Lack; Jung, Hang-Chul Oxidation Process for the Etching Solution Regeneration of Ferric Chloride Using Liquid and Solid Oxidizing Agent. Clean Technology 2017, 23, 158–162. [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Z.; Chang, J.-H.; Huang, C.-P. Electrochemical Regeneration of Fe2+ in Fenton Oxidation Processes. Water Research 2003, 37, 1308–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, R.G. Hard and Soft Acids and Bases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 3533–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colborn, R.; Nicol, M. An Investigation into the Kinetics and Mechanism of the Oxidation of Iron(II) by Oxygen in Aqueous Chloride Solutions. Journal of the South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy 1973, 73, 281–289. [Google Scholar]

- Posner, A.M. The Kinetics of Autoxidation of Ferrous Ions in Concentrated HCl Solutions. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1953, 49, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, M.J. Kinetics of the Oxidation of Copper(I) by Oxygen in Acidic Chloride Solutions. South African Journal of Chemistry 1984, 37, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hine, F.; Yamakawa, K. Mechanism of Oxidation of Cuprous Ion in Hydrochloric Acid Solution by Oxygen. Electrochimica Acta 1970, 15, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deront, M.; Samb, F.M.; Adler, N.; Péringer, P. Volumetric Oxygen Mass Transfer Coefficient in an Upflow Cocurrent Packed-Bed Bioreactor. Chemical Engineering Science 1998, 53, 1321–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.; Swinkels, D.A.J. THE KINETICS OF OXIDATION OF Cu(I) CHLORIDE BY OXYGEN IN NaCl-HCl SOLUTIONS. Hydrometallurgy 1986, 15, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, C.; Selleri, T.; Borfecchia, E.; Martini, A.; Lomachenko, K.A.; Janssens, T.V.W.; Cutini, M.; Bordiga, S.; Berlier, G. Structure and Reactivity of Oxygen-Bridged Diamino Dicopper(II) Complexes in Cu-Ion-Exchanged Chabazite Catalyst for NH3-Mediated Selective Catalytic Reduction. J Am Chem Soc 2020, 142, 15884–15896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velásquez-Yévenes, L.; Ram, R. The Aqueous Chemistry of the Copper-Ammonia System and Its Implications for the Sustainable Recovery of Copper. Cleaner Engineering and Technology 2022, 9, 100515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, D.D. Review of Mechanistic Analysis by Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. Electrochimica Acta 1990, 35, 1509–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).